Articles

Early-Modern European and Indigenous Linguistic Influences on New Brunswick Place Names

Abstract

This article documents the emergence of the New Brunswick place names Miramichi, Musquash, and Shemogue in the early-modern period (1534–1800). Using early maps and travel narratives in which these places are noted by Europeans for the first time, it examines the orthographical variety for each place name and traces their development over the centuries, mapping the evolution and diffusion of these names in light of the linguistic influences exerted by Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, French, and English speakers, as well as the transition of a name from one language to another. The historical and linguistic findings from this research are then linked to their sociopolitical relevance in a contemporary context and a language-based system of toponymic classification is proposed.

Résumé

Le présent article fait état de l’émergence des toponymes néo brunswickois de Miramichi, de Musquash et de Shemogue au cours de l’époque moderne (1534-1800). À l’aide de cartes anciennes et de récits de voyage dans lesquels ces lieux sont notés pour la première fois par les Européens, on y examine les variantes orthographiques de chaque toponyme et retrace leur évolution au fil des siècles, suivant ainsi la variation et la diffusion de ces toponymes à la lumière des influences linguistiques exercées par les locuteurs malécites, micmacs, francophones et anglophones ainsi que leur traduction d’une langue à l’autre. Les conclusions historiques et linguistiques de l’étude sont alors liées à leur pertinence sociopolitique dans un contexte contemporain, et un système de classification de la toponymie fondé sur la langue est proposé.

—The Naval Chronicle, 1760 (Fuller v. 3, 186).

1 The above statement by John Fuller reflects the eighteenth-century British view of the French practice of naming places and reveals an understanding of the seeming indelibility of name assignment and the power of publicly documenting toponymy. European nations used the naming of places as a form of textual occupation for which the language of the toponym became a powerful means of asserting claims upon territory, and this negotiation continued on the mass-produced page. Once named on a map or in a travel account, and subsequently printed and consumed by a wider reading public, place names confirmed occupation, in absentia or through concrete settlement: they reinforced colonial boundaries in the eyes of European readers. Translations, re-editions, and entirely new accounts detailing European activities in the Americas subsequently allowed for revisions to these names and borders. Thus an encroachment of a French name upon an English denomination for a place could either indicate or foreshadow the waning of British dominance in Atlantic Canada. Justification of Fuller’s concern is evident in the success of Britain’s own naming practices, which often effaced Indigenous descriptive names for a place, geographic feature, and region, or bestowed new ones upon places previously christened by French explorers and colonizers.

2 This linguistic erasure, however, was only partially successful. Many New Brunswick names acknowledge the Indigenous inhabitants of this land and recall the initial period of French conquest and colonization in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This period concluded after the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) and the grand dérangement that expelled French-speaking Acadians from the region in 1755–64. Anglophone communities flourished in their wake, but Acadians later returned and formed robust community identities the following century. Today, small English- and French-language communities dot Canada’s only officially bilingual province, in some ways reflecting the continued sociopolitical struggles of these communities. Many place names possess French roots; their orthography and pronunciation, or both, were anglicized when the English dominated the area. The opposite has also occurred: words of English denomination have become part of the French-language lexicon of the province and their pronunciation by the local population—in the case of Bathurst, pronounced “Bat-URST”—in some cases no longer corresponds to their phonetic antecedents. Furthermore, although often anglicized or frenchified, detected throughout the names awarded to this province’s places and geographical features are linguistic influences from the Algonquin family of languages (Maliseet, Mi’kmaw, and Montagnais or Innu-aimun), as well as traces of Indigenous languages spoken in other parts of North America. For example, Petitcodiac (adapted from Mi’kmaw1petgutgoiag, meaning tortuous, winding stream or petkoatkwee´ak, “the river bends round a bow”) later was popularly understood as French for petit coude, or little elbow (Assiniwi 123; Ganong 1896–97: 261), which exemplifies the grafting of one meaning upon another through phonetic semblance, further complicating the linguistic history of the province’s place names. Phonetic variety also exists within the same language spoken throughout a region, as demonstrated by Maritime Anglophones’ pronunciation of Greenwich, a settlement located in each of the three provinces: “GREEN-wich” in New Brunswick, “GREE-nich” in Nova Scotia, and “GREN-ich” in Prince Edward Island (Rayburn 53).

3 Many toponyms in the province of New Brunswick vibrate with colonial resonance: Fredericton, named in homage to a royal military figure, Prince Frederick Augustus, Duke of York (1763–1827); Moncton, given in recognition of the area’s British conqueror, Robert Monckton (1726–82); and Saint John (Fr. Saint-Jean), the anglicized name bestowed in celebration of the day that settlement was founded by Champlain and his party of French explorers, which coincided with the Catholic calendar of celebrations (Figure 1). Other place names describe geographical and topographical features of a place’s environment: Aulac (Fr. au lac, by the lake) at the foot of the Bay of Fundy; Cape Tormentine (Fr. Cap Tormentin) for the storms that rage against the coast; and Grand Falls in acknowledgement of the cataracts found there.

4 This article explores the meaning of a selected number of relatively unstudied New Brunswick place names that emerged during the early-modern period. Making use of maps and travel narratives in which these places are noted by Europeans for the first time, it examines the orthographical variety for each place name and traces its development in order to understand the evolution and diffusion of these names in light of the linguistic influences exerted by Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, Montagnais, French, and English speakers as well as the transition of a name from one language to another and then sometimes back again.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

5 Past attempts to categorize Canadian toponymy have been bulky and conceptually or demographically organized rather than linguistically oriented, and, as a result, certain types of toponymy have been omitted. The approach to bestowing names also varies from culture to culture, which means that any attempt to categorize toponymy must be flexible and respond to the linguistic nature of the place names themselves rather than force those names into a static system of classification. Hélène Hudon, for instance, identifies several areas and subcategories, including geographic features (administrative, artificial, and natural) and supplementary names (abbreviations and nicknames, both popular and local) (Hudon 28–29). The Geographical Names Board of Canada uses a fourteen-principle set of criteria that does not apply to historical naming but rather to contemporary naming practices (Geographical Names Board of Canada 2011), whereas Cornelius Osgood developed a classification system for his research into Gwitch’in toponymy near Great Bear Lake that included the following categories: names inspired by flora and faunal activities, material culture, flora by itself, historical events, mythological events, and specific individuals. They were classified as descriptive or metaphorical in nature, as reflecting aesthetic qualities, borrowed from other languages, or otherwise found to be of unknown origin (Sable and Francis 51). An additional issue with some of these toponymic categories is that they value western taxonomies for biological, cultural, and social information. In this article, following a discussion of New Brunswick toponymy, a comparatively inclusive system of place name classification based on historical linguistic exchanges is proposed.

6 This endeavour faces several challenges. The search for toponyms in historical documentation is an admittedly Eurocentric enterprise that relies upon and privileges the written word as an authority and source of information. Many of these sources were mass-produced in the early-modern period and contained place names derived from limited sources. Samuel de Champlain (1574–1635), for example, contributed more place names to Canada on the maps and in the texts he published between 1604 and 1632—themselves adaptations of Indigenous names, or borrowed, created, and bestowed from European sources—than any other individual. He bestowed over 330 documented names, of which only 9 percent refer to an Indigenous group. He tended to christen places descriptively, unlike his predecessor Jacques Cartier (1491–1557), who bestowed religious names inspired by Catholicism on more than 50 percent of the places he encountered. It is through mass-produced material such as the accounts of Cartier and Champlain that New Brunswick and its region, like other areas of the Americas, would become “appropriated by the acts of seeing, reporting, and naming” (Morissonneau 218). These texts, penned by English, French, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish cartographers, explorers, historians, and missionaries, found their sources in one another’s documented or first-hand experiences while travelling in the eastern part of present-day Canada.

7 Some of these published texts contain accounts of discovery, descriptions of Indigenous peoples and their ways of life, and lists of vocabulary relating a European word list to an Indigenous one. None contain the voices of the original inhabitants of this land except through European interpretation.

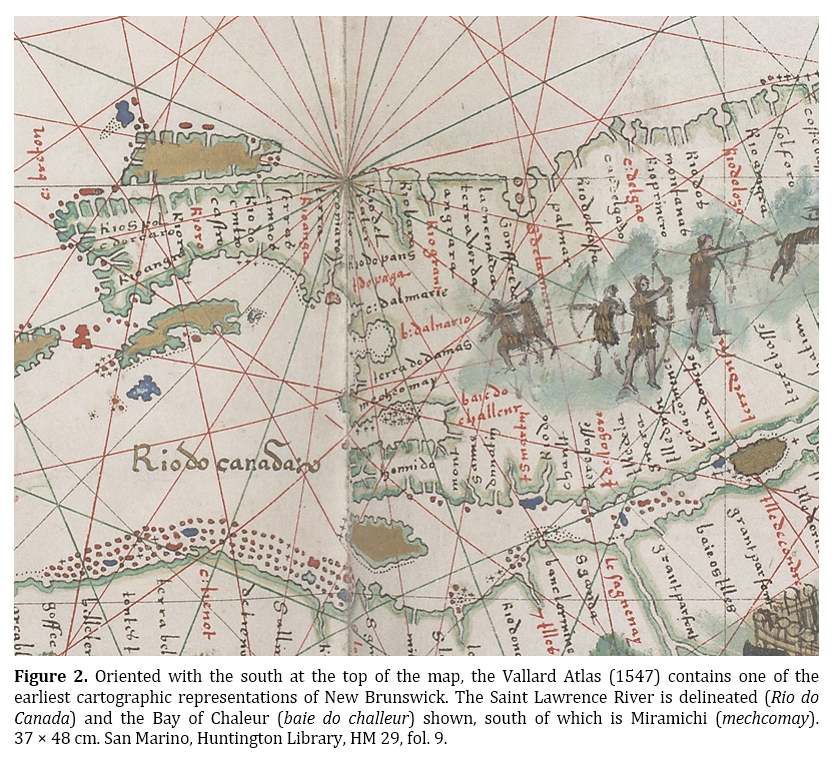

8 It also must be acknowledged that spoken form of communication as well as an oral as opposed to written history captures the legacy of time in many Indigenous cultures. Alan Rayburn insists that today’s toponyms as well as their antecedents are “imperfect renderings of what Aboriginal people may have said to explorers, who then provided their interpretations to publishers and map makers” (183). To these linguistic filters is added the historical transmigration of Indigenous peoples in the sixteenth century, which resulted in a linguistic transformation through which the Iroquois names recorded by Cartier using a French orthographical interpretation of the names he heard (e.g. Stadaconé) became replaced by Algonquin ones in the time of Champlain using the same process of linguistic appropriation (e.g. Quebec) after the latter people replaced the former in the domination of the area. Some of these names were rendered in French (Ir. Hochelaga, beaver path or rapids, became Fr. Montréal, royal mountain) as commemorative and descriptive names or appropriations of the Algonquin and Iroquois originals. As a result of the habitual migration patterns of Indigenous peoples, Europeans experienced difficulty learning a group’s description or name for a place in the distinct dialects and sometimes different languages of people in dynamic relationships with each other, because over time these geolinguistic factors changed. However, the use of Indigenous names such as these ones may also have been a deliberately utilized tool in the conqueror’s toolbox: “The choice of the place-name Quebec put a symbolic end to the Iroquois occupation; neither their space nor history was ever the same again” (Morissonneau 219, 223; Vallières 4–5). Champlain was credited with this act of naming, effacing Cartier’s bestowing of Stadaconé, and signalling a shift in the alliance between these Europeans and Indigenous populations of the area. Names wielded power at the same time that they betrayed the sociopolitical dynamics of the day.

9 Conceptual differences concerning the definition of place present another challenge to a less Eurocentric approach to understanding the province’s toponomy. European naming systems required that places bore fixed names that did not vary from one speaker to another. The official existence of these names was textually recorded and Europeans, by virtue of recurring to systems of documentation and printing for the diffusion of information, dominated the processes of bestowing and legitimizing a place name. In 1691 the French missionary Chrestien Le Clercq (1641–after 1700) described the people of Gaspé and

The French inability to classify places outside of their own chorographic and toponymic taxonomy to varying degrees denied the existence of the Indigenous spaces they encountered as well as their complexity.

10 This perspective remains entrenched in contemporary times, such that although some scholars might believe that Indigenous languages lend, as Rayburn describes in the late twentieth century, a “rustic beauty” (183) to the country’s toponymy, the search for Indigenous analogues is predicated on the assumption that the Maliseet and Mi’kmaq bestowed names on places in the same way that Europeans did. As another scholar noted in the late nineteenth century concerning the attempt to record Maliseet words using a system of language and expression employed in the pre-Columbian western world, “These people having no alphabet, it was necessary when writing their language to invent an alphabet or, to be more exact, to arrange the Roman-English characters in a suitable system” (Chamberlain 5). These conceptual and medial differences continue to manifest themselves at the level of the letter, a European unit of expression, which remains an anticipated ingredient in the scholarship about these place names and embodies the imposition of one culture upon another.

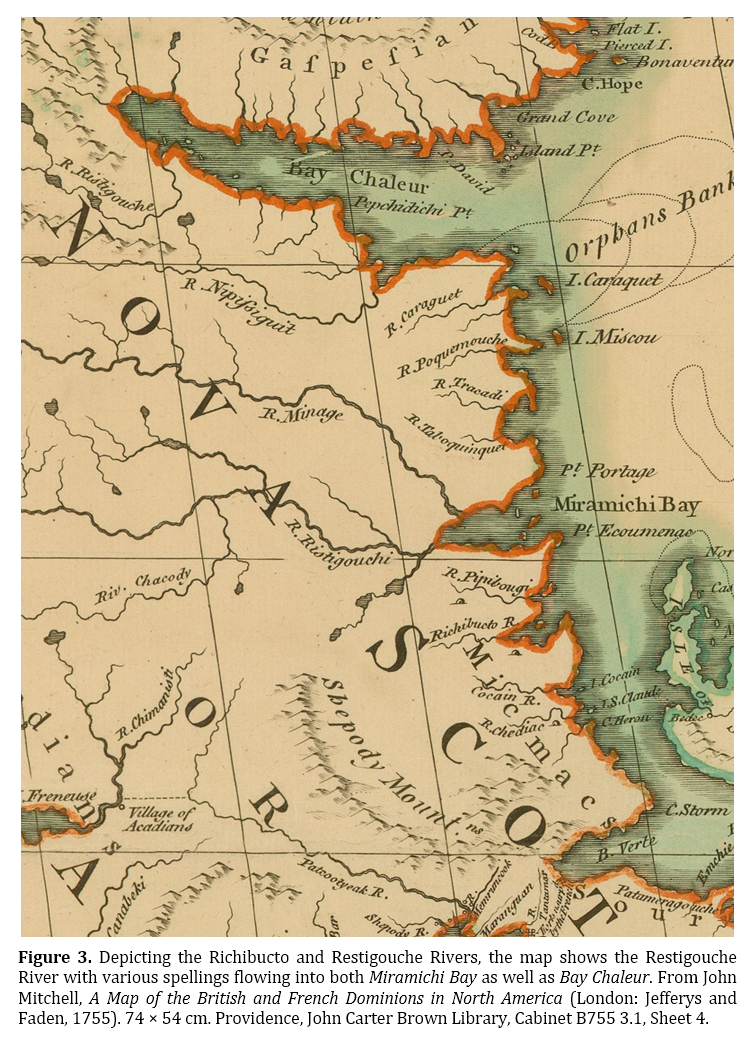

11 Europeans also drew inspiration for new-world place names from mythological and spiritual sources; they allowed names to serve as propaganda in favour of the enterprise of exploration and colonization; they denominated places according to the beauty or bounty of the natural resources found there; they adapted or attempted to render Indigenous names for places; and they invented and awarded names conceived by Europeans who used as their model an Adamic tabula rasa from the Garden of Eden, as if charged by some authority to baptize and provide names for everything in their path (Delgado-Gómez 10–12, 25–29).

12 A final challenge to tracing historical toponymy is that these languages today do not necessarily correlate in terms of orthography and pronunciation to the ones spoken or written hundreds of years ago, which makes an etymological study of oral history difficult because the medium evolves even if the content remains stable. The linguistic expertise required to perform this research into historical forms of various languages can pose another obstacle. The hybridity or composite nature of place names in New Brunswick forces us to return to the sources containing descriptions of Europeans’ first encounters with this territory, to seek historical forms of European and Indigenous languages in order to understand how similar words and terms were utilized and comprehended over the centuries, to consult contemporary orthographies and phonetics for these languages, and to always be aware and probe the use of language as a means of cultural domination.

13 Scholarship in this area as well as studies devoted to the historical development of Indigenous languages often have been carried out by non-Indigenous peoples, who to this day have remained custodians of the authoritative source governing the meaning of historical toponomy. The earliest attempts to formally study Indigenous languages developed into important works of scholarship in the nineteenth century, but little scholarship has been completed in recent decades on the subject. These early contributions provide a point of entry into the linguistic study of the Maliseet and Mi’kmaw languages spoken in previous centuries. One of these scholars, William F. Ganong, specifically called for further study into the origin of Indigenous place names, which he urged should be completed as soon as possible before linguistic dilution and cultural influences further affected knowledge of Indigenous languages (Ganong 1896–97: 213). While Ganong did not acknowledge that English and French languages acquired Indigenous vocabulary in the early-modern period much the same way that Maliseet and Mi’kmaw appropriated European terminology, he did believe that phonetic evolutions provoked by the transaction of toponyms between languages required particular attention.

14 Taking up Ganong’s challenge, we will examine the toponyms Miramichi, Musquash, and Shemogue, as well as some related place names, while exploring the practice of place naming as a western sociolinguistic phenomenon with historical significance.

Miramichi (Eastern New Brunswick)

15 Attempts to understand the origin of the toponym Miramichi used for the bay, lake, river, and settlement known by this name have frustrated scholars for more than a century (Assiniwi 90; Ganong 1889: 34; Hamilton 102). During his travels in 1534, the description of which was published in 1544, Cartier described two triangle-shaped bays, one of which we now recognize as Miramichi Bay, off which he noted a large river. Unlike the Bay of Chaleur to its north, named by him for its warm waters, he neither named nor explored the river or the bay into which it emptied on that voyage (Cartier 1867: 34). The textual source for the earliest cartographical labels containing Miramichi remains unknown, although it is likely that Europeans appropriated two or more Indigenous names, one of which defined a group’s territory, from the Mi’kmaw term megâmagé, “home of the micmacs, or the true men” (Rand 1902: 179), and the other a descriptive name, from the Maliseet word awarded to one of the river’s branches, minělminakŭn (Fr. Mirmenaganne).

16 The Desceliers world map (1546) is the first to christen this river R. des barques (River of Ships) after Cartier’s description of it from his first voyage, and calls the north-eastern part of the peninsula terre de mirig[al?]man.2 The creator of the Vallard Atlas (1547) called the region containing the river mechcomay, adjacent to the baie do challeur (Figure 2),3 which was later reproduced on the Desceliers 1550 and 1553 maps. André Thévet (1516–90), better known for another work in which he describes New France at length (1558, fol. 149r–64v), also authored a manuscript titled La Grand Insulaire, in which he noted “la baye de Chaleur que les barbares appelent Mechsameht [the bay of Heat that the barbarians call Mechsameht]” (t. 1, fol. 154v), whereas a Portuguese cartographer labelled it michcamai (Velho c. 1560). Some cartographers evidently failed to note that Cartier had visited two distinct bays, the Bay of Chaleur and to its south, Miramichi Bay, and they deployed a similar toponym in this region; none provided, however, an explanation of its meaning. The placement of this same river northward and flowing into the Bay of Chaleur, as opposed to Miramichi Bay, exemplifies geo-linguistic confusion occasioned by the existence of multiple, navigable rivers located off numerous bays. The European attraction and thus cartographic attention to navigable rivers reflected the desire to find watercourses that extended into and across the continent, much in the way Magellan had in the early sixteenth century.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

17 Lexicographical studies have struggled to provide a consistent definition for Miramichi that correlates to the relatively unstable range of geographic features that it described in seventeenth-century European sources: “Fleuve des Barques, que je prens pour Mesamichis” [river] (Lescarbot 240); “La baye du petit misamichy” [bay] (Champlain 1632); Misamichisus pagus [settlement] (De Creux 1660); Miramichy [region] (Denys 1672; Ganong 1896–97: 196); Mizamichiche [River], Mirmenaganne [settlement], and “les Sauvages de mizamichis de toutes les autres Nations de la Nouvelle France” [the people] (Le Clercq 200, 240, 245–46; Rayburn 188–89); and Miramichy [River] and Grandmira Micha [settlement] (Vischer 1698). The use by Jesuit missionary Le Clercq of Indigenous names comes in the wake of the French rejection of these names in favour of French translations of Indigenous denominations. For example, decades before Le Clercq, Jérôme Lalemant (1593–1673) referred to Mi’kmaw territory as “le pays de la nation du Porc-espic [the land of the Porcupine nation],” rendering into French the name used by other Indigenous groups, including the Maliseet and Montagnais, to signify the Mi’kmaq (225; Petitot 281). This last example demonstrates that some European names and definitions did accurately reflect the Indigenous names for places in content, if not in form.

18 A study of Indigenous names for the Miramichi River provides additional context. The river is known as lŭstŭkotchits (Maliseet) and lŭstegoocheech (Mi’kmaw), meaning “good river,” and the northwestern branch of the river as minělminakŭn (Maliseet) (Chamberlain 59; Rand 1888: 170). Keeping in mind the European pronunciation of the Maliseet and Mi’kmaw phoneme /l/ using the Roman grapheme r, Rand defines lustoogootc as Restigouche and lustoogootcētc as Little Restigouche, “the place of dead decaying trees” in Maliseet (1902: 87, 184). Clearly, Rand does not provide a suitable definition for Miramichi that is otherwise distinct from the Restigouche River, but Chamberlain does identify the Maliseet toponym for Mirmenaganne, the settlement cited by Le Clerq in 1691, as minělminakŭn, in reference to the north-western branch of the Miramichi River located near Nelson (59). The Maliseet and the Mi’kmaq used a similar name for the main branch (lŭstŭkotchits and lŭstegoocheech, respectively), which reflects the reality that two Indigenous nations’ territories bordered on this region. Both nations furthermore used a different term for the north-western branch of the river (minělminakŭn and megâmagé). Gaspé, after all, descends from the Mi’kmaw gespeg or kechpi (kespe’k) meaning “the end of our territory,” and, as noted above, megâmagé signified that nation’s territory (Assiniwi 51). Both of these names provide a geo-linguistic context for the territory dominated by the Mi’kmaq when Europeans went about recording these place names.

19 With this linguistic context in place, and given the similarity shared by toponyms for this region awarded by Europeans in the mid-sixteenth century, it is not unreasonable to suggest that either of the terms, megâmagé or minělminakŭn, became appropriated by a French speaker in the sixteenth century and emerged on French maps prepared in the 1540s. Exceptionally, and in light of references to the Porcupine Nation, mechomay and the subsequent place names it inspired resemble the phonetic transcription mi:kmay advised by the Oxford English Dictionary Third Edition (2001) for the term Mi’kmaw so that English speakers would pronounce the word with greater authenticity.

20 Despite the documentation of the Miramichi and Restigouche Rivers in seventeenth-century Jesuit relations and on some maps, by the eighteenth-century mapmakers cartographically effaced the Miramichi River and replaced it with the Restigouche River (Figure 3). This erasure suggests that the Indigenous name for the main river had become predominant in this period (Hamilton 122; Turner 1750). At the same time, a third watercourse, the Richibucto River, slowly materialized along this coastline. Being the southern-most of the three rivers, its name in Mi’kmaw, lichibouktouck, means “river which enters the woods.” Visscher introduced the river accurately, with the Miramichi River in its place more or less (1698; reprinted 1715), but he replaced the Restigouche River with Grandmira Micha. Even more confusing is Seutter’s c. 1740 map upon which a probable orthographic error Pichibouctou replaces the Richibucto River. To its north is the R. Ristigouchi and in the same bay, a second river, Ristigoucht (Little Restigouche), and emptying into the Bay of Chaleur is R. Ristigouche (Large Restigouche) (also see Bellin 1755). As on Turner’s 1750 map, this representation omits Miramichi as well.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

21 Why does Miramichi disappear for a period of time in the eighteenth century from maps, especially when it was a cartographically and textually established watercourse in the previous century? When Grandmira Micha appears in European documentation, the French writer in this case has been influenced by the Indigenous suffix for greatness (Fr. grand, or large, influenced by Mi. lustoogootc, rendered by Europeans Restigouche, and then rendered as the linguistically hybridized term Grandmira Micha), whereas the suffix -chi in toponyms such as Veskakchis (Westcock) and lustoogootcētc, Little Restigouche, is a diminutive. It is possible that the transference of toponyms from one language to another gave rise to the elimination of Miramichi for a period of time, and subsequently Restigouche and Miramichi became synonymous with each other.

22 For our purposes, we have identified the descriptive Indigenous origins of the toponyms Miramichi, Restigouche, and Richibucto, and demonstrated how their linguistic evolution as well as a lack of differentiation between these watercourses was manifested in the early-modern period by Europeans.

Musquash (Southwest New Brunswick)

23 Musquash Cove is located west of Fredericton on the present-day border with the state of Maine, whereas the town of 1,200 inhabitants (2011 Census) and the river with this name are found slightly west of Saint John where the Maliseet predominated, near to which Musquash Harbour opens into the Bay of Fundy. These place names derive from the muskrat, a toponym with a surprisingly ample history before it became applied to several features located in present-day New Brunswick.

24 The name for Musquash Island in Maliseet today is nesakěnits, whereas the Musquash River is known as mesakaskwěl (Chamberlain 59–60): mesak forms the Maliseet root for this name. Some scholars have associated this toponym with the Cree term maskwâš and Abenaki term moskwas, meaning muskrat. Cree was spoken in central Canada and near Hudson Bay, as evidenced by the phrase for doing business in the fur trade, “talking musquash” (Ralph 491; Houston et al. 241), whereas Abenaki was spoken in the western region adjacent to Maliseet territory. The present-day name is an anglicized appropriation of an Indigenous word used elsewhere in North America but made famous for its association with the fur trade industry. It later became displaced to New Brunswick where Europeans noted an abundance of muskrat. Muskrats now flourish throughout the world but they originate in North America.

25 The French adopted this term, rat musqué (musky rat), first. In 1545 Cartier called them raz sauvaiges, because “vivent en l’aue, & son gros comme connyns, & bons à merveilles [they live in the water and are big as rabbits and marvellously tasty]” (21v). Champlain’s contemporary, Marc Lescarbot (c. 1570–1641), included the rat porte-musc among the animals found in New France in 1609 (26) and an illustration of the rodent appeared on Champlain’s 1613 map titled Carte geographique de la Novvelle Franse in the region of present-day Maine and New York (Figure 4). The term signified a beaver-like animal in a description penned by Jesuit and superior of Kebec, Paul Le Jeune (1591–1664), published in 1634 (78).4 Later that century, however, the spelling had been adapted: also known in the seventeenth century as a furet deau (water ferret), ouatchas was the Montagnais term for rat musché in Louis Nicolas’s illustrated book of natural history (172; Silvy 102). The word emerged in the English lexicon shortly after it circulated in French: Ralph Hamor, in his description of Virginia published in 1614, translated the French term to muske rats (Hamor 20), and John Smith, in his treatise on New England, referred in 1616 to them as musquassus (Smith 19). Its first use as a New Brunswick place name appears to be by de Meulles (1686).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

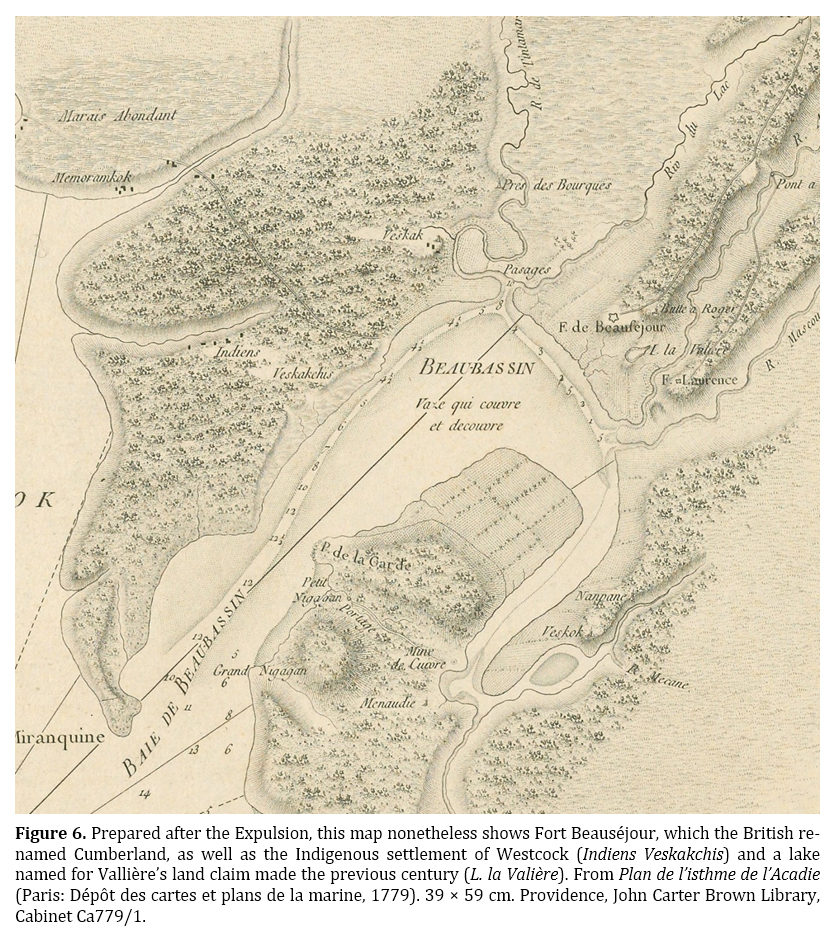

26 Europeans sometimes acquired Indigenous names like Musquash and then developed them into more European-sounding forms. Westcock (Westmorland County), a settlement housing several families today, provides a complex example of this phenomenon. It appeared on maps as an Acadian settlement in the eighteenth century and became a British settlement after the Expulsion; indeed, the community of British settlement is situated less than three kilometres west of Westcock. Believed to descend from the Mi’kmaw term oesgag, oesgagsis now signifies Allen Creek. It appears in English documentation as early as 1731 in Robert Hale’s travel account as Worshcock (Falcon-Lang 8) and on maps as Wesqua (Jefferys 1755), West Coup (Montrésor 1768)—and on this map an East Coup uniquely exists just south of Fort Lawrence—whereas a French-language map labels the area Indiens Veskakchis (Indians of Little Westcock; the suffix -chis provides this diminutive) as well as the area near present-day Nappan, Nova Scotia, named Veskok (Dépôt Général 1779; Pacifique 223) (Figure 6). Some of its present-day form, oesgagsis, derives from this English-language adaptation; the suffix -sis signifies a small watercourse such as a creek whereas oesgāg phonetically resembles Westcock. How this settlement gained the name Westcock is unknown, nor can we be certain if the name was inspired by Indigenous terminology or if Europeans denominated the settlement themselves. Certainly, the French version, Veskakchis, exemplifies a unique interlinguistic hybridity composed of the French interpretation of the English pronunciation of Westcock modified by the Mi’kmaw diminutive suffix. The Mi’kmaw appropriation of the English place name is a phenomenon that will be studied below.

27 A final piece of etymological evidence concerning the origin of Musquash can be found in the Mi’kmaw term with which they referred to the Maliseet as “the Muskrat people” (Chamberlain 8), although muskrat in Maliseet is kaiuhŭs (Chamberlain 33) and in Mi’kmaw keooāsoo (kiwa’su) (Rand 1888: 175). Evidently, Musquash does not come from either of those Indigenous words, but moskwas, which phonetically resembles this place name, in Abenaki also refers to a Maliseet person. Like the Porcupine Nation whose referent is the Mi’kmaq as a people, all of these languages assign the meaning of muskrat in the same way, even if the word varies from one to another. Meaning “the one whose head bobs above the water” in Abenaki, the irony of this linguistic association is that Europeans appropriated a foreign Indigenous term and used it as part of their colonial occupation of New Brunswick while dominating both the rodent and the people that inspired this name, all the while maintaining the Indigenous assignment of meaning to the muskrat in order to signify the Maliseet people.

Shemogue (Southeastern New Brunswick)

28 The communities of Shemogue and Little Shemogue (Westmorland County) are located east of Moncton on the coast of the Northumberland Strait and facing Prince Edward Island. Europeans began to settle in this region in the late seventeenth century, as the attention paid by de Meulles on his 1686 map of the area attests. He provides two toponyms, Chimougouïche (Big Chimougoui) and Chimougouichiche (Little Chimougoui). These names reflect the Mi’kmaw spelling of Restigouche (lustoogootc, Big Restigouche, and lustoogootcētc, Little Restigouche) studied above (de Meulles 1686; Léger 10) and the use of a diminutive in the English-French-Mi’kmaw toponym, Indiens Veskakchis. Hamilton proposes that Shemogue signifies “a good place for geese” because both communities lie in the pathway of migrating ducks (137), but it seems more likely that the term relates to oosomogwek (place where the river forks), and Shemogue River is spelled today semogoig or osemogoeg (Léger 10; Pacifique 222).

29 Michel Leneuf de la Vallière received a seigneurial land grant for this region that included much of the isthmus connecting Nova Scotia with New Brunswick in 1676. Some Mi’kmaq toponyms were specified within the land grant, including Kimongouitche, a river located near Baie Verte that Ganong believes to be a transcription error for Simongouitche, pronounced by the Acadians Choumougouit (today written Chimougoui in French and Shemogue in English). Simongouitche means Little Simougouit in its Mi’kmaw-inspired French form (Griffiths 116–17; Ganong 1896–97: 272; Ganong 1911–18: 188). The land grant in question describes the “rivière appelée Kimongouitche, aussi y comprise avec dix lieues de profondeur dans ledites terres, dont la baie de Chignitou & le cap Tourmantin son partie [river named Kimongouitche, which extends ten leagues into those territories toward Chignecto Bay and Cape Tormentine]” (Mémoires, t. 2, 576). Parochial registers confirm that “Chimougoui” had become an Acadian settlement in 1754 (Léger 6).

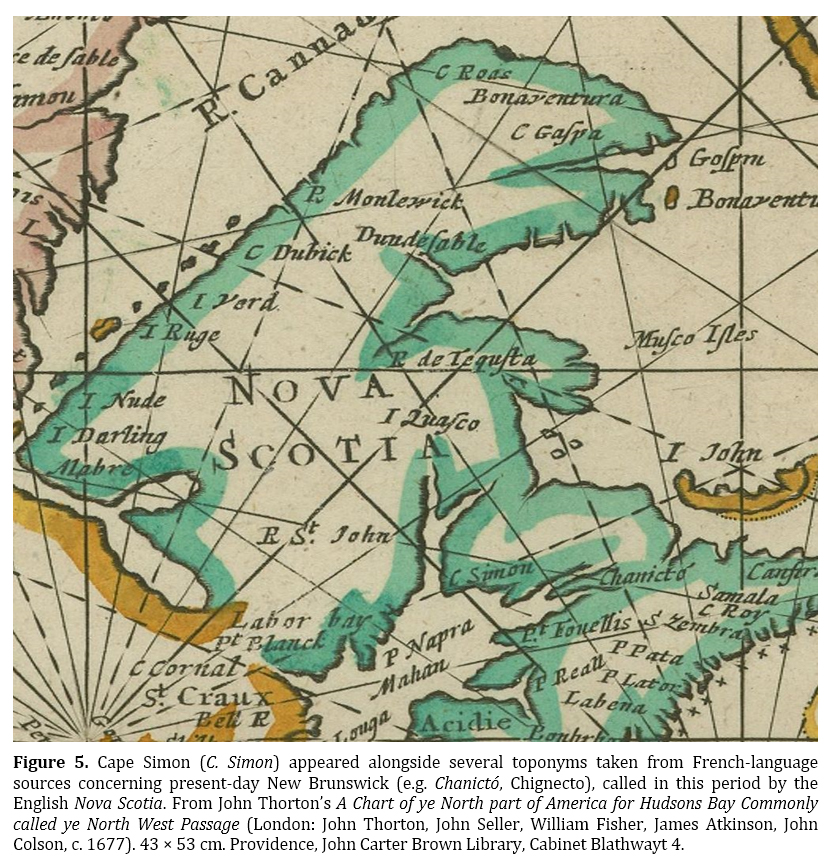

30 Rand believes that the toponym derives from Simon’s Place, named after an unidentified French man, and was subsequently put into Mi’kmaw as simooaquik or simogwik, which makes the Shemogue River equate to Simon’s River, simogwesk (Rand 1902: 189). Although the European name Simon does not undergo an orthographic change in Mi’kmaw (see, for instance, Matthew 26:6 in the Mi’kmaw translation of the Bible, titled Gelulg Glusuaqan: Gisiteget Agnutmugsi’gw), we cannot be certain to whom the name Simon may have referred, nor why Rand believed that a connection existed. Champlain was accompanied by a missionary with this surname during his 1604 voyage that would bring him into the Bay of Fundy. Cape Simon appeared on maps situated at the end of the Bay of Fundy near present-day Cumberland County, Nova Scotia, on the west side of the isthmus later that same century (Figure 5). The name was spelled C. Simon on Thorton’s A Chart of ye North part of America for Hudsons Bay Commonly called ye North West Passage (c. 1677), as well as on Visscher’s Carte nouvelle contenant la partie d’Amerique la plus septentrionale (1698), and today a settlement named for the captain, Antoine-Charles Denys de Saint-Simon (1734–85), exists in the Restigouche area. It seems unlikely, however, that any of these names inspired Shemogue.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

31 Many eighteenth-century maps, including Denis’s Carte du theatre de la guerre presente en Amerique and a French military map, label the area granted to Vallière as territory occupied by the Mi’kmaq (Figure 6). If we study similar toponymy in the region we will conclude that this name is likely of Mi’kmaw origin and not a European one rendered into Mi’kmaw. Census information from the mid-seventeenth century allows us to locate proximate settlements that share the same suffix signifying place or harbour: malegāwatc (now Malagash, Cumberland County, Nova Scotia) means the mocking-place (Rand 1889: 184); minitiguich or mirliguèche (now Malagawatch, Inverness County, Nova Scotia); and merligouèche (now Lunenburg, Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia; Mirligueche according to Chabert in 1753) (Chabert 139; Hamilton 357; Shears 11). Similar-sounding toponyms existed contemporaneously alongside Kimongouitche, a Mi’kmaw descriptive name for the forked river found in this place; all of these locations are situated along the open water.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

32 A related toponym in the immediate vicinity of Shemogue etymologically relates to Fr. hareng (herring) and appeared on French maps as C. Haran (de Meulles 1686) and C. Hanars (Bellin 1755). It was later anglicized C. Haran (Turner 1750), C. Heron in Mitchell’s and Montrésor’s maps of 1755 and 1768, respectively, and Cape Herring on A New and Accurate Map of the Province of Nova Scotia (1781). Residing not far from Shemogue was Fort Gaspereaux, which had as its namesake a species of herring called sigonemao in present-day Mi’kmaw, although Ganong provides the toponym of this denomination as gaspalawik´took, which is clearly a Mi’kmaw acquisition of the Acadian term used by Denys in 1672, gasparo (Ganong 1896–97: 235; Hamilton 78–79; Pacifique 202, 223). Gasparo subsequently inspired the English-language toponym based on its synonym, herring.

33 Indigenous linguistic acquisitions of this nature are easily found upon reading a bilingual dictionary: the word for goodbye in Maliseet, atiu, comes from the French word adieu, whereas the English language inspires the word for clock, kŭlak (Chamberlain 61). The Mi’kmaw word for English descends from the French term, anglais, and is aglāsēā, which also signifies a foreigner from over the sea. Similarly, a German settlement was termed an ālmawākade, from the French word allemand (alma-, German, and -akade, place) in Mi’kmaw, whereas an English settlement is an aglaseāwākăde (Rand 1902: 8; Ganong 1911–18: 382–448). These particular examples exhibit a linguistic hybridity through which English and French words come to modify Mi’kmaq ones. Speakers of Mi’kmaw also adapted entirely European-derived names for places, as seen with the name for Westcock, oesgag. The name eloibolg (L’uipulk) reflected the French pronunciation of Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, as did emtāgoon or montāgūn for Montague, Prince Edward Island (Rand 1902: 181). Larry’s Gulch in Mi’kmaw is laliôeoei epsagog, whereas the root of Isabel’s Gulch is isapeleg (Pacifique 195, 207).

34 In more recent times, naming authorities have attempted to render into Indigenous languages certain place names in order to avoid the co-existence of two or more places with the same name. This process often involved a problematic, literal translation of the English- or French-language name into Maliseet and Mi’kmaw rather than an investigation into the possibility of utilizing a name awarded by Indigenous peoples to a place. Of the sixty places in Canada called Salmon River, twelve of them are in New Brunswick. Railroad authorities in the nineteenth century decided to replace the name of the settlement located in Kings County with its supposedly Maliseet equivalent, Plumweseep. The new denomination more accurately resembles the Mi’kmaw name for that river, pulamooaseboo (pla’muey sipu; pla’mu and seboo signify salmon and river, respectively, in Mi’kmaw) rather than the Maliseet name, cheeminpie, a version of which appeared on de Meulles’s map of 1686. The area also falls within the traditional lands of the Maliseet Nation (Hamilton 117–18; de Meulles 1686; Rand 1888: 224). It appears that provincial and railroad authorities confused the two Indigenous languages at the time of undertaking this toponym reassignment and the name, moreover, remains in existence today.

A Framework for Research into Canadian Toponymy

35 Many of New Brunswick’s toponyms describe the geographical location of a place: Aulac (Westmorland County), for its position at the end of the Bay of Fundy; Eel River (Restigouche County), from Fr. anguille after the abundance of eel found there; Grande-Digue (Kent County), named for a long dyke, and Six Roads (Gloucester County), named for where three roads cross (Ganong 1896–97: 232; Hamilton 83). Europeans and Indigenous peoples named places descriptively but they also borrowed interlinguistically from one another’s descriptions, as we have seen: Miramichi from the Mi’kmaw name of the people who occupied the region; Petitcodiac from the Mi’kmaw for the bend in the river; Restigouche from the Maliseet and Mi’kmaw for the quality and size of that river; and Richibucto from the Mi’kmaw for the river that enters the woods. All of these names have been altered in order to facilitate their pronunciation and spelling in English or French. Some names were acquired by Europeans from Indigenous antecedents, in the case of Malagash, Miramichi, Musquash, Shemogue, and possibly Westcock. Europeans also acquired names created by each other, as evidenced by Cape Herring. Other names were acquired by Indigenous peoples, as exemplified by gaspalawiktook (Gaspereaux), isapeleg (Isabel’s Gulch), eloibolg (Louisbourg), laliôeoei epsagog (Larry’s Gulch), and emtāgoon or montāgūn (Montague). Finally, some of these names became hybrid compositions involving more than one language.

36 The bestowing of toponymy that celebrates or remembers the colonial past of an area and its people clearly has inspired naming practices across New Brunswick. Examples of transfer and commemorative place names include settlements such as Dieppe, named after its French predecessor following the events of the Second World War; Desherbiers (Kent County), christened after one of Fort Louisbourg’s commanders, Charles des Herbiers de la Ralière (c. 1700–52); and Bathurst and Moncton, described above, in commemoration of British colonial figures by those names. The province of Quebec, in its celebration of the Acadian heritage of Canada, contains several places named after New Brunswick ones, their denominators, explorers, and settlers. Many Quebecois towns possess a street named Acadie, a park Beauséjour, or a lake commemorating the colonizer Nicholas Denys (c. 1598–1688) (Commission de toponymie 2004). Six of the country’s provinces and territories boast at least one settlement named for Acadia; three for Beauséjour; and five for Denys: the local history that influences naming practices in New Brunswick also asserts itself throughout Canada.

37 These European-derived names celebrate a European presence on this land, whereas Indigenous place names tend to acknowledge presence rather than refer to some achievement or past success. Many Indigenous cultures consider place names mnemonic devices that aid in remembering the land or in finding one’s way (Sable and Francis 50). Historically, such names do not begin with initial capitals, unlike in the European languages where this is a spelling convention, although exceptions have been appearing in recent years. It is for this reason that Indigenous toponomy has not been capitalized throughout this article whereas European adaptations of those names have been capitalized. As a result, Indigenous names seem ad hoc in both a colonial and post-colonial context precisely because Western languages capitalize toponymy.

38 In order to comply with the English- and French-language expectations of Canadian authorities, moreover, Indigenous names must be modified. The Elsipogtog First Nation is a settlement and reserve, as well as a Mi’kmaw people, located on lands traditionally occupied by that nation in eastern New Brunswick. The name acknowledges this Mi’kmaw presence: meaning “river of fire” or “big cove” in Mi’kmaw, it is a European phonetic adaptation of lsipuktuk (l’sipuktu; puktu signifies harbour in Mi’kmaw) (Ganong 1896–97: 222), a term that bears a convincing similarity to Richibucto once the oral /l/ converts in written form to r (i.e. risipuktuk), today rendered lichibouktouck in reference to the “river which enters the woods.” The spelling of Elsipogtog evolved to more easily enable pronunciation among Europeans, which is why distinct orthographies have been developed for this language in both French (e.g., the Pacifique orthography of 1927) and English (the Francis-Smith orthography of 1974) in an attempt to stabilize the relationship between text and spoken word, on the one hand, as well as the language itself, on the other, for speakers or would-be-speakers of Mi’kmaw conversant in either English or French (Metallic et al. viii). Interestingly, the Geographical Names Board of Canada, the national authority that approves the bestowing of toponyms, excludes Elsipogtog in all of its orthographical varieties from its database of toponyms. Despite its mandate to record the names of populated places and administrative areas, it instead refers to the area as Richibucto 15. Elsipogtog First Nation has been classified as the fifteenth of twenty-eight reservations in New Brunswick. Further exposing the sociopolitical iniquities betrayed by this province’s toponymy, the Geographical Names Board of Canada’s website also provides background on the origins of New Brunswick’s place names and uses as its examples the cities of Bathurst, Edmundston, Moncton, and Saint John.

39 This article has taken up Ganong’s challenge to investigate the heretofore unknown origins of certain New Brunswick toponyms through historical linguistic exchanges. In so doing, we have developed a distinct approach to the study of Canada’s toponymy, one that takes into account the historical and linguistic complexity behind the bestowing of names, while classifying the phenomenon of naming into broad categories from a pluricultural perspective that utilizes resources drawn from a multitude of languages and media. These place names are either commemorative or descriptive in nature, European adoptions of Indigenous toponyms or European adaptations of names generated in another European language; Indigenous adoptions of European place names or Indigenous names in their own right; and composite, hybrid names composed from more than one language. This classification accounts for the linguistic and conceptual instability of toponymy in a (post-)colonial context and exposes the complex ways in which Indigenous place names have developed and are used today.