Articles

“The First Frame House in Sackville Parish”

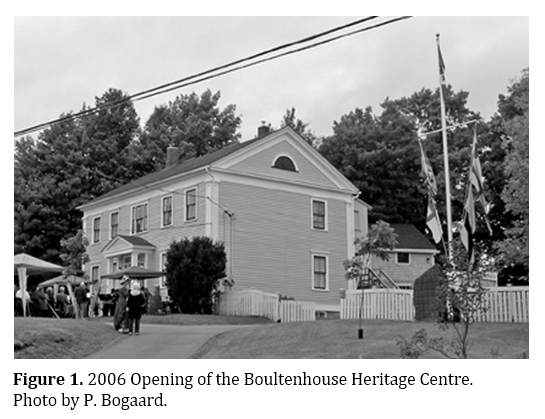

1 This is the saga of over twelve years’ research to confirm whether the Tantramar Heritage Trust really does own the “first frame house in Sackville Parish.” The Trust had nothing like this in mind when it purchased the Christopher Boultenhouse property in 2001.1 Our attention was focused on the handsome house of a Sackville shipwright, not on the back “ell” he used as a kitchen. All we found in the back was a storage area and a garage with a gravel floor.

Discovery

2 At the time we were intrigued by Boultenhouse’s decision to move from Woodpoint to “lower Sackville” in the 1840s; he even relocated his shipyard to the Tantramar River, at a time when many enterprises were shifting into what was rapidly becoming the new centre of town. We were eager to renovate the home of Westmorland County’s most prolific shipbuilder2 and make it into our second museum—the only shipwright’s house in New Brunswick now open to the public (Figure 1).

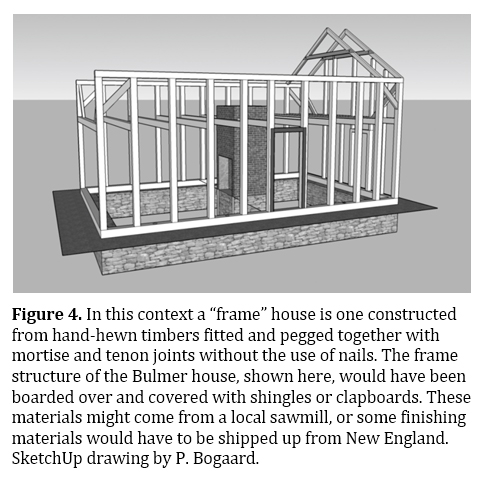

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

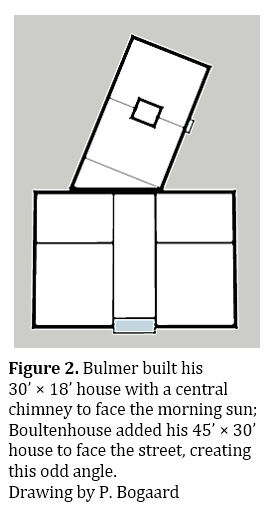

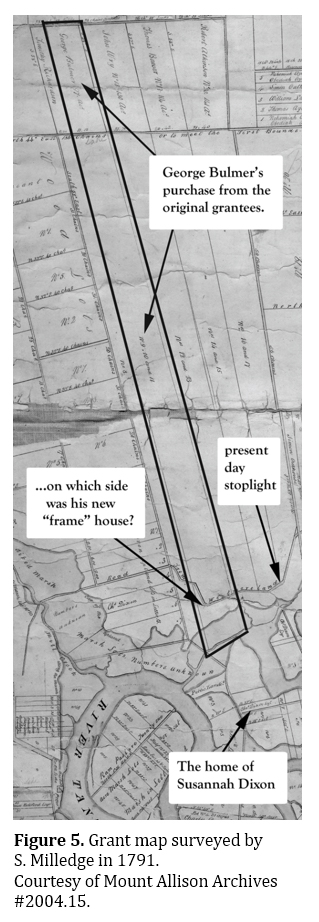

3 Before we began its restoration, however, we found ourselves in serious need of office space, and decided to make use of that back ell. Only when the modern ceiling, walls, and floor were stripped away did we begin to realize that what had been covered over seemed much older than the front house built by Boultenhouse (Figure 2). We seemed to have discovered an earlier house, but how much earlier? And, had it come with the property Boultenhouse purchased? We had already determined that he likely purchased this property from the Bulmers, but tracking this down through the convoluted land transactions preserved in the land registry office proved challenging. Untangling all the twists and turns has taken repeated efforts over many years.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

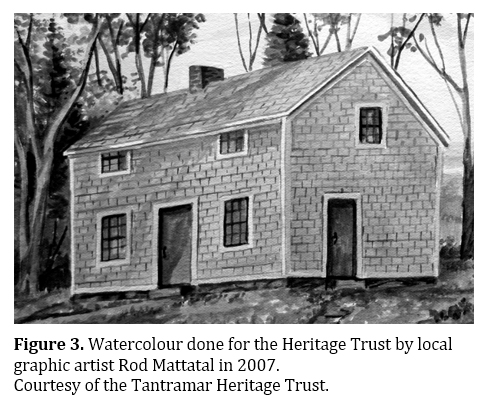

4 We might have dropped the matter at that point but, as luck would have it, Mount Allison University had recently hired a specialist in dendrochronology (dating wooden structures by analyzing growth rings) and we had done him a favour by allowing extensive sampling at the Campbell Carriage Factory,3 Sackville’s first museum. In return, he agreed to analyze the age of the timbers in the house we had just acquired, and also the back ell that looked even older. The results revealed that the trees used for framing the main house—tamarack, like the timber used in his shipyard—were cut down around 1840, while the red spruce used to frame the back ell had been felled fifty years earlier! A house from the 1790s could not have been built by Boultenhouse. It seemed most likely to have been built by George Bulmer (Figure 3).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

5 That prompted me to reach for my copy of W.C. Milner’s History of Sackville (1934), recalling the story he tells of George Bulmer building the “first frame house in Sackville Parish” (Figure 4). Could this be it? Could the Heritage Trust have reached out for a handsome shipwright’s house, and unwittingly snagged the oldest frame house in the parish? If so, this would not be just a happy accident—it would provide a vital landmark in the early development of New Brunswick’s very first township.

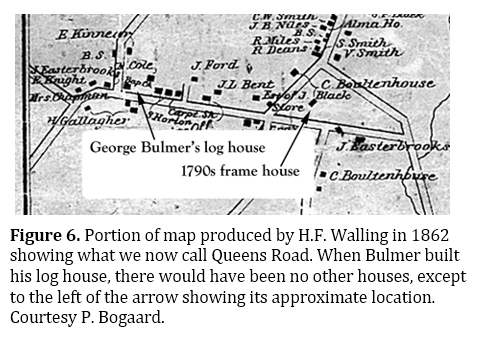

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

Complications

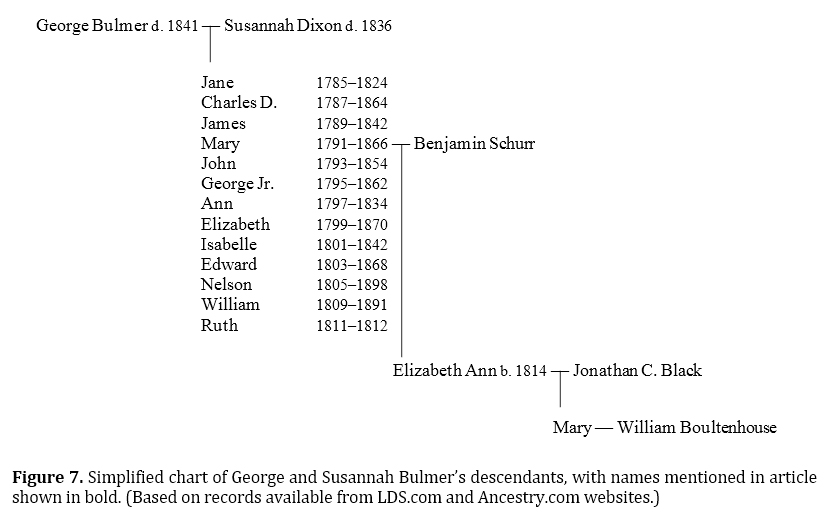

6 There were complications. It was clearly established that the Trust owned a house dating from before 1800, and those are very rare in Sackville. Indeed, there are hardly any houses of that vintage remaining in the whole region.4 But showing that this house was the one in Milner’s story proved difficult. Registry office information about deed transfers from various Bulmers to Boultenhouse was a confusing morass. The challenge was not that we couldn’t find such transfers, but rather there were so many! The Bulmers were swapping and selling many parcels during that period, and Boultenhouse purchased dozens of parcels. (He ended his days with over forty deeds!)

7 We found the deed whereby George Bulmer in 1784 purchased three adjoining “rights” or “shares” granted twenty-five years earlier to a Planter family (Figure 5), but could not find any record of his selling it or any portions of it. Moreover, the story in Milner says that the house built by George Bulmer was eventually sold to and lived in by Jonathan C. Black. And, as Phyllis Stopps (a local historian who has completed extensive research on early houses in Sackville) warned me, there were a number of Jonathan Black houses, and therefore other candidates for the “first frame house” in Sackville.

8 Milner’s story is very valuable for anyone interested in the earliest stories about Sackville’s development. He got the story, he tells us, from “an old lady long since gone to her rest, viz.: Mrs. Cynthia (Barnes) Atkinson.” She identifies all the houses that were scattered along the Main Post Road by 1820. Milner so appreciated this story, he told it twice! In one telling, he relates that “the first frame house” was at Boultenhouse Corner (where today Bulmer Lane converges with Main Street and Queens Road). But was it on the northwest side of that corner, where the medical clinic now stands, or was it to the southeast, toward our Boultenhouse Heritage Centre?

Display large image of Figure 5

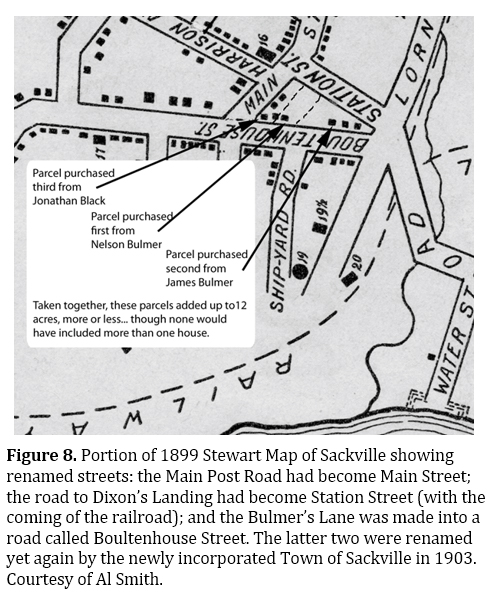

Display large image of Figure 5

9 When I returned to the registry office, located in Moncton for Westmorland County, some outlines began to appear through the fog. One very unusual item, recorded as an Indenture in 1837, was between one of George Bulmer’s sons, Nelson, and his siblings. It did not shed any light on the house in question, but did explain that by the 1830s their father, George, had fallen ill and was no longer competent to handle his own affairs. It even mentioned that, at his death (George did not pass away until 1841), then and only then would his own extensive land holdings pass along to his sons and daughters (or their husbands). A most unusual declaration, I thought, but it certainly helped explain why there were no recorded sales of land in the name of George Bulmer.

10 With that in mind, one sale from Nelson Bulmer was soon located, and another from James, that transferred parcels of the Bulmer estate to Christopher Boultenhouse. And there were descriptions that confirmed they were somewhere within the twelve-acre holding Christopher was known to have owned. They were identified as Lots #7 and #8 on a subdivision plan drawn up by their “attorney,” Jonathan C. Black.5 So, we now knew that the Jonathan Black mentioned by Milner played a key role in the dispersal of George Bulmer’s holdings, although as no one has been able to locate his plan for this subdivision, those lot numbers are of little use. And neither of these descriptions included any mention of their father’s house.

11 Later records show Boultenhouse purchasing a number of parcels directly from Jonathan Black, including one that began by saying it was for a parcel in Middle Sackville, and on that basis I set that one aside. In retrospect, this was a serious blunder on my part. But at the time, that seemed as far as one could go.

Context

12 A bit more historical context should help to frame this story. George Bulmer, the person reputed to have built “the first frame house in Sackville Parish,” had sailed over from Yorkshire when he was still quite young, twelve or thirteen. He came on the Duke of York in 1772 along with his brother, William (a carpenter), the Freezes, Andersons, and notably Charles Dixon’s family, who took a fancy to young Bulmer. According to George’s son Nelson, his father had come over apprenticed to Mr. Freeze, a stone mason. Apparently, they spent the next several years in Cumberland where there was likely plenty of work for masons rebuilding Fort Cumberland and the occasional stone house and chapel erected by Yorkshire immigrants.6

13 The fort was fully garrisoned by the British after it had been won from the French, and for several years through prolonged guerilla warfare. But after British forces took Fortress Louisburg on Cape Breton in 1758, and with the Planter settlement of Sackville, Cumberland, and Amherst townships well underway, the garrison was substantially reduced7 and little attention was paid to upkeep of the fort—at least not until rebellious Americans began threatening British sovereignty in the 1770s; then there was need for repairing the stone fabric of the fort and its buildings. Since a traditional apprenticeship lasted seven years, George Bulmer was likely kept busy there through the 1770s—his teen years.

14 Thereafter George’s prospects seemed to have improved, and by 1784 he had successfully courted Charles Dixon’s second daughter, Susannah, and purchased a large tract of land between what today we call Queens Road and Union Street in Sackville, extending from below Lorne Street northwest to “the wilderness.” As recalled by his son Nelson, George purchased the “rights” or “shares” to the fifteen hundred acres granted to Nicholas Cook and sons, and then immediately set about building a log house (Figure 6). What Susannah thought about living in a log home, we do not know, except to say that since the early 1760s this was the sort of house in which most couples started their families.8 She might have had more to say about living over in the Salem district (where later the Salem Baptist Church would be built, where George built his log home), where there were already several neighbours, but it was a long way from her parents’ home on what is now named Charles Street.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

15 There is no way of knowing for sure, but it just seems very likely to my romantic spirit, that when George set about building his bride a proper “frame” house, he would situate it just beyond where the Main Post Road turned across his land, out on the brow of that height of land, so that from the front of his new south-facing house Susannah could easily look across to the next hill and see her mother hanging out the wash. For her, he would build “the first frame house in Sackville Parish”! And it seemed that the timber for that new house could have been cut down around 1790. But if we wanted to confirm that Susannah’s frame house was the same one dendrochronology confirmed was built in the early 1790s, we still had some nagging discrepancies to sort out.

The Fog Lifts

16 Milner’s story claims that George and Susannah’s frame house went to Jonathan C. Black, but the descriptions of the parcel purchased from Nelson Bulmer make no mention of the house nor of J.C. Black. It does, however, suggest that the land in the direction of the frame house was under the ownership of one Benjamin C. Scurr. Until recently, we could not find any further information about Benjamin C. Scurr, and we could see no way through these complications.

17 Until last summer. I must confess that the solutions were in the photocopies I had taken at the registry office years earlier, sitting there sniggering at me from the folder labelled Bulmer House Puzzle. It was only last summer, working closely with two of our summer students to refine the family trees of both the Boultenhouses and Bulmers, that a glimmer of light broke through. We had been encouraged by the public reception of the Anderson family tree, now exhibited in the Octagonal House renovated on the occasion of Sackville’s 250th anniversary in 2012, and so decided it was past time to do the same for the two houses built by Christopher Boultenhouse and (we hoped) George Bulmer. What these students uncovered was that Benjamin Scurr had married George and Susannah’s second daughter, Mary, and that Benjamin and Mary’s daughter, Elizabeth Ann, had married Jonathan C. Black—the attorney who had done so much to sort out the George Bulmer estate (see Figure 7).

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

18 When I reopened my file of registry documents and re-read the descriptions, this is the sequence that became clear, now that we had these genealogical connections in mind.

19 (1) First, from the Land Registry for 15 January 1842:

- Nelson Bulmer…in consideration of 150 pounds…paid by Christopher Boultenhouse…has sold a parcel of upland situated in Sackville…and described on a plan made by Jonathan C. Black of the Real Estate of George Bulmer, deceased…

-

- North & West by lands of Benjamin C. Scurr,

- North & East by a Road leading to Dixon’s Landing,

- South & West by a Road laid out on the aforesaid Plan for the use of the owners of the land belonging to the aforesaid Estate…

- And containing 3½ acres…w/ appurtenances.

20 While it had known for years that Christopher had bought a parcel from Nelson, we had not realized then that Jonathan Black, as the attorney who drew up the plan of George Bulmer’s estate, was an in-law of the family. Similarly, we had not realized that Benjamin Scurr was married to George and Susannah’s daughter, Mary, and that it was they who held the portion of their father’s estate to the northwest.

21 Furthermore, the reference to a road leading to Dixon’s Landing clearly located Nelson’s parcel to the southwest of what we now call Dufferin Street—roughly the land on which Marshview Middle School now stands. And finally, we now know that George passed away sometime in 1841 and his wife, Susannah, about 1836. It seems likely that it was just after Susannah passed away that her children registered their agreement concerning their father’s estate, declaring him legally incompetent. Similarly, as soon as their father passed away in 1841, title to his lands passed to his heirs, and that’s when they began selling off portions of it (Figure 8).

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

22 (2) The very next item in the Land Registry, on the same date, is as follows:

- James Bulmer…in consideration of 100 pounds…paid by Christopher Boultenhouse…has sold a parcel of upland situated in Sackville…and described on a plan made by Jonathan C. Black of the Real Estate of George Bulmer, deceased, as the lot number #8:

-

- North & West by lands of said Christopher Boultenhouse, lately purchased from Nelson Bulmer,

- North & East by a Road leading to Dixon’s Landing,

- South & West by a Road laid out on the aforesaid Plan for the convenience of the proprietors of the land belonging to the aforesaid Estate…

- And containing 5½ acres…w/ appurtenances.

23 So, in this case, a parcel also to the southwest of Dufferin, now has Christopher as the owner immediately to the northwest (toward Main Street)—at least he had now been its owner for an hour or so!—which clarifies that this parcel is downhill from Marshview Middle School, and likely extended all the way to where Dufferin crosses Lorne and meets the other road, just prior to the railway line. And for the second time, we read that this was a road, or lane, used by George Bulmer and his family. At the upper end, at what came to be called Boultenhouse Corner, we now think a private lane followed the same path as the street does today, and then curved in to provide access to the house built there in the early 1790s. It makes sense that there would also be a lane from this farmstead down the hill to their marsh holdings. And, as it happens, Nelson Bulmer recalled a time when “Grampa” Charles Dixon had been visiting. Nelson was only eight or so, but his father and brothers were elsewhere, so his mother asked him to hitch the oxen up to the cart and drive Grampa down the hill to the aboideau9 (again, right about at the present-day railway crossing). He was surely making use of the same lane described in the deeds of both Nelson and James.

24 (3) The crucial evidence comes from this next item, which I had set aside years earlier. From the Land Registry for 15 October 1845:

- Jonathan C. Black & Elizabeth, his wife…in consideration of 110 pounds…paid by Christopher Boultenhouse…has sold a parcel of upland situate in Middle Village…and containing 3 acres, bounded as follows:

-

- West by the Main Post Road passing through Sackville,

- North by a road leading from the Main Post Road to Dixon’s Landing (so called), East by lands of Christopher Boultenhouse,

- South by a road leading also from the Main Post Road to Dixon’s Landing,

- Together with all the Estate…with appurtenances…with all the improvements and privileges belonging to the same.

25 There are several points about this that are relevant: one is that at three acres, this lot added to the two previously listed ones adds up to twelve acres, and it is known from the probate of Christopher Boultenhouse’s own estate that his house (and its back ell) sat on a holding of twelve acres.

26 Of course, it was the reference to “Middle Village” that had thrown me off, years before, as I read it as Middle Sackville. This time I realized it is a reference to Middle Village in the original layout of the Township or Parish of Sackville—extending from the upper mill stream issuing from Silver Lake to the lower mill stream flowing down Frosty Hollow.10 I should also have noticed that the description not only places it just along Main Street, but also along Dufferin Street, which means it must have been adjacent to the two parcels purchased from Nelson and James. There is even a reference to the old lane running down the other side, now listed as another road to the Landing, since Boultenhouse had by this time registered an agreement with his neighbours for a roadway to be constructed—the one that came to be called Boultenhouse Street (and is now referred to as an extension of Queens Road). This deed would neatly encompass twelve acres within these three streets. (All clearly named in Figure 8.)

27 This is of particular importance, as these descriptions do not locate the boundaries precisely. But they do give us the streets, and we know exactly where those are. And there is no way to measure out three acres from Main Street toward Marshview Middle School that does not include the early Bulmer house. Starting from the other end, when you measure out five and a half acres for James, and three and a half acres for Nelson Bulmer, you have encompassed the school and probably the house that used to sit where the Heritage Trust parking lot is now located, but not the Bulmer frame house.11

Family

And yet, it seemed there was a human element missing from the geometric solution just given. It begins with the question of how Jonathan C. Black gained possession of this parcel and house. Frustrated by this remaining gap, I recently returned once more to the registry office and almost immediately came up with a deed from Benjamin and Mary Scurr, selling a parcel, with exactly the same description as the parcel listed in (3) above:

28 We can establish two key points from this: that Jonathan C. Black purchased the property he subsequently sold to Christopher Boultenhouse from his wife’s parents, and that his mother-in-law, Mary, received this same parcel by inheritance from George Bulmer when he died. The description of the parcel is exactly the same, and I can only wish it had been more explicit about “the lands and premises.”

29 It does not say, but one might well suspect, that this tangle originates in George Bulmer’s incompetence. Extraordinary measures had been taken to ensure the family’s inheritance (the registry declaration of 1837 mentioned earlier) when their father could not do so for himself. But more than that, someone surely had to care for him, especially once his own wife passed away in the mid-1830s. And where more likely than in his own home? This might have fallen to one of their daughters, but Jane had long since married a preacher from Maccan and had moved there, Elizabeth had married and moved to Lunenberg, and Mary, although still nearby, had married Benjamin Scurr and lived on the farm he inherited from his in-laws, the Cornforths.

30 Of the daughters, we know it was Mary who inherited the portion of George’s estate that included the frame house, and her own daughter, Elizabeth Ann, married Jonathan C. Black in 1833. So, one is led to suspect that it was Jonathan and Elizabeth Ann who moved in with Grampa and Gramma Bulmer. (Milner says that Jonathan lived there.) Clearly, it was Jonathan who played the pivotal role in laying out and subdividing Grampa Bulmer’s considerable holdings. They would have lived there when (or soon after) Susannah Dixon Bulmer passed away, and stayed on until George Bulmer died in 1841.

31 Before 1841 was over, Jonathan had seen to it that George’s heirs inherited their portions, and he actually stepped in and purchased inherited portions from John, William, and George’s daughter Elizabeth, through her husband, Henry McCellan. Most likely, these siblings had established themselves elsewhere by this time. The work of Phyllis Stopps on the house across Main Street—the one many of us can recall as the nurses’ residence (where the medical clinic now stands) suggests that this is the lot Jonathan purchased from John Bulmer, and on which he proceeded to build a house for himself and his family. Phyllis noted a newspaper account that suggests it was built in 1842.

32 Christopher Boultenhouse acquired the parcels from Nelson and James Bulmer in 1842, and it seems likely this is the year in which he added his handsome house onto the older Bulmer house. That’s what dendrochronology tells us, and it happens to be the only year for a decade in which he does not have his carpenters busy building a ship. This timing further ties in with Jonathan Black moving his family across the road to their own newer house, in 1842. A decade thereafter, a daughter of the Blacks is married to Christopher’s son, William. So, there were certainly close connections between these families.12

33 Perhaps that explains why the final settlement for this land and old frame house was not registered until 1845. It was not uncommon for titles to be registered at a later date, when there was compelling reason to do so. Or perhaps there were financial or other arrangements still unfolding. (Christopher and Jonathan engaged in a whole series of land transactions.) What is clear is that when the registration finally took place, the transfer from Mary and her husband Benjamin Scurr to Jonathan Black was registered on the very same day as the transfer of this same parcel to Christopher Boultenhouse. They are literally #12.145 and #12.146 in the Land Registry. Clearly, this had all been planned ahead. In the meantime, no one in the family had any reason to doubt whose property and whose house was involved.

Conclusions

34 Some of this is surmise, but the facts, summarized below, do make a compelling case. George Bulmer purchased a large tract from the original grantees, which we can locate on the grant map of 1791. After building a log house, within a few years he moved his growing family into the first frame house in Sackville. We know this house was built in the 1790s, so it has to have been George’s, as it was on his land, and his own sons were still too young. This frame house and the parcel on which it stands was inherited by his daughter, Mary, and subsequently sold to her son-in-law, who sold it to Christopher Boultenhouse. Then, Christopher built a handsome new house attached to the Bulmer house, now fifty years old, which he used as his kitchen.

35 As a consequence, when the Tantramar Heritage Trust purchased this shipwright’s house in 2001, we inadvertently bought the first frame house in Sackville Parish. The donor who made this possible handed us a key landmark in the historical development of New Brunswick’s first and oldest township. It just took us a while to realize what we had.