Articles

Progressive Era Financial Reform in New Brunswick:

Abolishing the Auditor General

Abstract

In 1918, following a series of financial scandals, the government of New Brunswick passed a new Audit Act, section 44 of which stated “the office of the Auditor General is hereby abolished.” The government contracted the audit function to a representative firm from the expanding public accounting industry, and the auditor general model did not re- emerge until fifty years later. This article examines how the abolition resulted from a confluence of forces, in which a new Liberal government was responding to a series of financial scandals associated with the previous administration. In supporting these changes, the government used the professionalizing technical language of the Progressive Era to modernize key financial functions. The government was heavily influenced by consulting advice provided by Price Waterhouse, chartered accountants, a prominent international accounting firm. The resulting changes, while improving the financial systems of the government, weakened the accountability of the executive branch to the legislative assembly, marking an early step in the decline of legislative control over the public purse in Canada.

Résumé

En 1918, à la suite d’une série de scandales financiers, le gouvernement du Nouveau Brunswick a fait adopter une nouvelle loi sur la vérification des comptes publics, dont l’article 44 précisait que « le Bureau du vérificateur général est aboli » [traduction]. Le gouvernement a confié la question de la vérification à une entreprise représentative de l’industrie de la comptabilité publique en constante expansion, et le modèle du vérificateur général n’a refait surface que cinquante ans plus tard. Le présent article examine comment l’abolition s’est traduite par un ensemble de facteurs et qu’un nouveau gouvernement libéral réagissait à une série de scandales financiers attribuables à l’ancienne administration. En appuyant de tels changements, le gouvernement a utilisé la professionnalisation du langage technique de l’ère progressiste afin de moderniser des fonctions financières clés. Le gouvernement était fortement influencé par des conseils d’experts-comptables agréés de Price Waterhouse, un éminent cabinet comptable international. Bien que les changements apportés aient amélioré les systèmes financiers du gouvernement, ils ont affaibli la responsabilisation du pouvoir exécutif de l’Assemblée législative, ce qui a marqué le début du déclin du contrôle législatif des deniers publics au Canada.

Introduction

1 On 20 February 1906, the Hon. L.J. Tweedie delivered his government’s budget speech to the Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick. In it, he offered a rare note of recognition to the aging auditor general, James Scott Beek, who had been serving the province since 1867. After outlining the various departmental estimates, and promising a small surplus for the coming fiscal year, Tweedie noted, “We have given the Auditor General an additional allowance of $225 which he claims is due him. As this gentleman is 92 years of age and has never had a very large salary, I think there will be no criticism on this account” (Synoptic Report of the Proceedings of the Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick 1906 37). Tweedie went on to say that Beek’s assistant, “who is doing his work well, as those who are familiar with the public accounts are well aware,” was in line for a $200 pay increase (37). A few months later Beek retired (Beek to Tweedie), at which time Wilson A. Loudoun, Beek’s unnamed assistant in Tweedie’s speech, assumed the auditor general’s post (Executive Council Meeting 3 October 1906 219).

2 It is safe to say that the history of auditors general in Canada is largely incomplete. With the exception of some research dealing with the rise of value-for-money audit in various legislative audit offices in the 1970s, very little has been written. There is virtually nothing in the research about the historical development of auditors general in the three Maritime provinces. The absence of research on the history of the Canadian legislative audit function reminds us of the ethicist William Schweiker’s criticism in a leading accounting journal that “this concentration on the present has led to the ahistorical character of accounting research” (242).

3 This paper addresses that deficit by examining important Progressive Era evolutions in the role and in the empowering legislation of the auditor general of New Brunswick from the retirement of James Beek in 1906 to the disappearance of the office in 1918. In doing so, it will show how Progressive ideas affected government financial systems and how those changes impacted the relationship between the executive and the legislative branches of government. Further, this case study establishes how a series of financial scandals in the early years of the twentieth century set the stage for those changes, and how Price Waterhouse, chartered accountants, a leading firm of the growing accounting profession, used the situation to expand its own practice. In the process, the abolition of the auditor general imposed limitations on the legislative assembly’s control of the public purse. Following the changes to legislation in 1918, the auditor of the province’s books would no longer be a legislative officer reporting directly to the legislative assembly, but rather a private sector firm reporting to the executive. This removed an important legislative control over executive spending power, weakening a key component of the fiscal oversight structure implicit in the Westminster model of parliamentary government. This change would be a step on a long road in Canada, a road marked by the weakening of legislative power paralleled by an enhancement of executive power.

Background and Early History of the Audit Function in NB

4 The first New Brunswick auditor general seems to have been Captain George Shore, appointed in 1823, along with his co-appointments as receiver general and surveyor general (Black). Two years later, Shore received formal legislative support via a Bill for Better Examining and Auditing the Public Accounts of the Province. A second, very short, one-page Act Relating to Public Accounts appeared in 1855, mentioning the officer known as the auditor general.

5 When New Brunswick entered Confederation in 1867, its financial administration continued largely unchanged. Norman Ward has written that while in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, financial control may not have been at the same level as that in the House of Commons, “none the less, by 1867 the assemblies in both provinces had established a procedure for granting money, and subsequently examining accounts, which was based, though most imperfectly, on the British model” (23). New Brunswick’s auditor general was a key part of the procedure of examining these accounts. In the fall of 1867, James Scott Beek, the former mayor of Fredericton, became the auditor general. Beek’s main task was preparing the public accounts, a thorough listing of the various revenue and expenditure transactions for each fiscal year. As auditor general, much like the auditors general of today, Beek’s report went directly to the legislative assembly, indicating an independence of his office from the executive branch of government. (The executive branch, essentially what we would call the cabinet formed by the majority party in the legislature, is responsible for implementing and carrying out the programs and activities of government. The legislative branch, on the other hand, consists of all the elected members of the parties represented in the legislature. This branch is responsible for voting on legislation, approving the budget the executive plans to spend, and for holding the executive to account for how it has performed in its duties [Leclerc et al 14–5].)

6 The 1877 Provincial Revenues and Accounts Act shows that the auditor general had considerable powers in post-Confederation New Brunswick. Section 11, for example, granted him “the power of a Justice to cause any witness to be brought before him, and examine such witness on oath touching such public accounts.” Further, Section 19 provided that the auditor general had to countersign every cheque issued for payment. In carrying out this responsibility, the auditor general had to prepare a memorandum showing “in brief form of the authority or Act of Assembly under and by virtue of which such warrant or cheque is authorized.” In other words, if the assembly had not authorized the expenditure, Beek could not sign the cheque. The auditor general of the day did indeed ensure that the legislature had control of the public purse. These powerful sections of the Act remained intact for the whole of Beek’s term.

7 Despite this comprehensiveness, the Office of the auditor general was a rather small operation. Aside from Beek and Loudoun, there appears to have been only one other part-time employee. Of course, the government of the time was much smaller. Today, the New Brunswick Office of the Auditor General has twenty-five employees, most of them accountants, auditing a provincial operation many times the size of what it was in 1900 (Report of the Auditor General of New Brunswick 2013, Volume I 164). Likewise, the accounting profession in the province has grown considerably. In the early twentieth century, though, the accounting profession in New Brunswick was small and unorganized. Although Creighton tells us that a group of accountants from Saint John had formed a chapter affiliated with the Ontario Institute of Chartered Accountants sometime in the 1880s, the chapter died out a few years later when a leading member moved to Toronto (20–1). Hudson further characterizes the local accounting scene of the time as being in a “chaotic state” (9), with a school in nearby Nova Scotia producing chartered accountants “a dime a dozen” (9). Professionalization in New Brunswick had obviously not advanced as far as it had in Ontario where the Institute of Chartered Accountants had been formed in 1879. The New Brunswick Institute of Chartered Accountants would not be incorporated until 1916, with Loudoun taking on a leading role as one of only three founding members (Hudson 10). Just a short time after, the accounting firm of Price Waterhouse would work with a new provincial administration to make a major impact on the office of the auditor general and Loudoun’s own role in public finance.

The “Insurmountable” Majority

8 On 3 March 1908, Douglas Hazen led the Conservative party to an election victory in New Brunswick. Babcock tells us that this victory was “abetted in part by a sentiment bearing many of the earmarks of American-style progressive reform” (8). In one sense, we might say this was the first Conservative victory in the province as party labels and party discipline had only emerged in New Brunswick at the turn of the century (Thorburn 13). One of the new government’s early legislative changes impacted directly on Loudoun’s work. Whereas Beek had enjoyed independence from the executive, as indicated by his reporting directly to the legislative assembly, Loudoun found himself reporting to a government minister, the receiver general. Section 22(2) of the May 1908 Act to Provide for Auditing the Public Accounts imposed this new reporting relationship on the auditor general. In reality, this 1908 Act simply codified something that had begun in 1906 when Loudoun began addressing the public accounts to the provincial secretary, a government minister. For at least a couple of years, Loudoun was in non-compliance with requirements to report directly to the legislative assembly. Perhaps these changes in 1906 and 1908 indicate that the political class of that day did not understand the accounting profession’s emerging concept of auditor independence.

9 In 1911, Hazen resigned to enable his return to the federal political scene. James Kidd Flemming, the provincial secretary, became leader of the Conservative party and premier of New Brunswick. In 1912, Flemming achieved his own mandate by claiming forty-six of the province’s forty- eight seats. With only two Liberal members in opposition, it seemed as if the Conservatives would have an insurmountable majority for some time to come. Politics, though, is full of surprises. By the time the Conservative government’s mandate had expired, a series of financial scandals dramatically impacted both the future of the New Brunswick government and that of the office of the auditor general.

10 The first of these scandals involved payments for leases on the Crown Lands. In the spring of 1914, L.A. Dugal, a Liberal member from Madawaska, rose in the legislature, charging that Premier Flemming and W.H. Berry, an employee of the Department of the Surveyor General, had extorted approximately one hundred thousand dollars from companies leasing Crown timber lands. Dugal alleged that Berry, acting under the direct knowledge of the premier, was charging lumber companies who were seeking new leases to replace those expiring in 1918: a fee of $15 for each square mile of Crown Land leased (“Dugal Charges Premier Flemming with Extorting $100,000 from Lumbermen” 1). This $15 premium had supposedly been directed to the Conservative party to fund re-election efforts. According to one paper of the day, Mr. Dugal made his charges “amid intense silence” where “most of those present were visibly surprised and astounded” (“Dugal Charges Premier” 1). Dugal obviously had the government’s attention. Indeed, the premier himself “sat silently for fifteen minutes, then left the Chamber…and walked the snow-covered streets of Fredericton to the Barker House Hotel” (Doyle 38).

11 Needless to say, this issue got the public’s attention. The heavily partisan press of the day saw Liberal newspapers lined up on one side to decry the government while the Conservative papers lauded the character of the premier and condemned his detractors. The Saint John Daily Telegraph, a known Liberal paper, opened its morning edition with bold block letters: “Dugal Charges Premier Flemming With Extorting $100,000 From Lumbermen.” Meanwhile, the Conservative party’s main organ, the Fredericton Daily Gleaner, countered with its own glaring headline of “Dugal Charges Wholly Untrue,” and focused criticism back on the Liberals through questions about Dugal’s possible conflict of interest while he had been mayor of Edmundston (1+). Closer to the premier’s home in Carleton County, The Carleton Sentinel, closely affiliated with Liberal member of Parliament F.B. Carvell, featured a lead article, “Sensational Charges Made” (1+). The Woodstock Press, solidly in support of the premier, noted these attacks came with the assistance of “two of the most nefarious political gunmen who could be found” (Doyle 39). The Daily Times from Moncton tipped its hand toward the Conservative side by declaring on its front page, “PremierFlemming Authorizes Most Emphatic Denial of Dugal Charges” (1).Only the Sackville Tribune summarized the question of the day for many New Brunswickers: “Guilty or Not Guilty?” (4).

12 Unfortunately for Flemming and his colleagues, before guilt or innocence could be debated, let alone decided, Dugal continued his work in the legislature by delivering another blow on the following day. On 7 April, Dugal introduced a notice of motion calling for a committee to investigate charges that contractors on the Valley Railway had been compelled by government members to pay them in return for obtaining contracts. Allegations were that these payments were upwards of $100,000. The government had guaranteed financing of $10,000 per mile of track laid, and, in fact, on the exact day Dugal tabled his motion regarding the payments to members, the government carried out first and second reading on a bill to proceed with $2 million in bond guarantees for the railway’s construction (“Charges that Contractors were Forced to Pay Money to Members of Government” 1). Again, the press comments were predictable. While the Daily Telegraph spoke of these railroad-related payments as “more grave charges” (1), the Valley Railway project was praised by the Daily Gleaner on its front page (“Government Commended for Careful & Prudent Provisions in Legislation” 1). The twice-weekly Sackville Tribune tipped its hand when it called this $2 million in railroad financing “amazing and outrageous” (1).

13 In response to the controversy, on 18 April 1914 the government passed legislation calling for a Royal Commission Concerning St. John and Quebec Railway Company Charges (McKeown et al 116). A month later, the government ordered a Royal Commission Concerning Timber Limit Charges (McKeown et al 95) to address serious charges against the premier and his government. The hearings began in June 1914 with the same three commissioners—Harrison A. McKeown, W. Wilberforce Wells, and W. Shives Fisher—dealing with both charges. The commissions concluded in the early fall, with both reports dated 30 September 1914. Although the Report of the Royal Commission Concerning Timber Limit Charges found Flemming “not guilty as charged” (114), other comments in the report seemed to do everything but declare him culpable. For instance, the report noted that Flemming “knew that efforts were being made to get moneys from certain holders of Crown Timber licenses” (112). Further, the report stated Flemming “could not possibly have been in ignorance of Berry’s activities and of the methods he employed” (112). In short, while the commission found J.K. Flemming not guilty, it certainly did not find him innocent. The other McKeown commission dealing with the Valley Railway matter showed that Flemming had received $2,000 from the railway contractors Kennedy and McDonald. While Kennedy maintained there was no compulsion, the commissioners stated, “We have no hesitation in concluding that the compulsion undoubtedly existed” (143). On the advice of the lieutenant governor, Flemming resigned, turning over the premier’s post to George Clarke (Doyle 67).

14 Clarke seemed to have neither the energy nor the ability to turn this rather dire political situation around (Doyle 100). Shortly after taking over as premier, Clarke was informed of another financial crisis in the Department of Public Works. Conservative party organizer Richard Hanson stated that “the province has been milked of large sums of money for wages and supplies that were never rendered, some of them being by way of payrolls and some…for false vouchers” (Doyle 91). Clarke responded on 3 March 1915 by creating another commission, this one headed by Judge William Chandler1 to examine these serious allegations regarding work on roads and bridges in Gloucester County. The Chandler Commission started on 18 March 1915. When the commission reported several months later, readers would find “several examples of petty embezzlement, payroll-padding and misuse of public money” (Doyle 97). Perhaps particularly galling to a public with sons at war was the evidence that A.J.H. Stewart, a Conservative member of the assembly, had not paid stumpage on timber he had harvested from Crown Lands. Further, Commissioner Chandler declared that the way Stewart acted “compels me to be suspicious as to everything he has done and of every transaction with which he is in any way connected” (83). While not in itself a death blow, the Chandler Report was one more example of a government in need of stronger financial control.

15 At around the same time as the Chandler Report, Premier Clarke’s government fired Harry Blair, the deputy minister of public works, for at least two apparent misdeeds. First, Blair was accused of having received payoffs from a contractor engaged to paint the province’s steel bridges. Second, Blair seemed to be a bit too free with sharing departmental information with prominent Liberal politicians. Despite these matters, however, Blair was not prepared to go quietly. He embarrassed the government on 20 May 1916 by claiming that the government had been reporting surpluses from 1911 through 1915 when it actually should have been reporting deficits (Doyle 109). This notion of switching deficits into surpluses would re-emerge when the accountants from Price Waterhouse took a look at the provincial finances in 1917.

16 Meanwhile, the troubled government found that the Valley Railway situation was worsening. The St. John and Quebec Construction Company, the railway’s builders, were unable to secure a second bond issue in New York City. Funds were lacking and, as a result, contractors and subcontractors began to complain to the government that they were not being paid. In May 1915 the government passed legislation which would permit it, after giving due notice, to vest all the shares of the company “in His Majesty, on behalf of the province” (McKeown 52). Given the government guarantees involved, the public purse was clearly at risk. After notifying the construction company in June to make suitable arrangements to complete construction, and judging that it did not provide a satisfactory answer, the government intervened in August 1915 and appointed its own team of directors (McKeown 55). This did not sit well with the deposed company president, Arthur Gould, who promptly threatened legal action (Doyle 91). Once again, Commissioner McKeown was called into action, this time as arbitrator of the dispute between Gould and the government.

17 The credibility of the government was clearly being undermined in serial fashion. Moreover, all of this talk of graft and corruption seemed to energize the Liberal party. Reduced in 1912 to a rump of two members from Madawaska, the Liberals saw the financial mismanagement of the Conservatives as a campaign issue that could bring down the government. When the election was finally called for 1917, the Liberal party concentrated its attacks on the trail of Conservative scandals. In addition, “They hammered away at the government for the enormous increase in the public debt, an increase from $6,000,000 to $16,000,000 since 1908” (Doyle 125), when the Liberals last held power. Liberal leader Walter Foster raised Progressive Era notions as part of the campaign, “declaring that he would, ‘if successful, carry on the business of New Brunswick with care and devotion to business principles and would associate himself with men of known probity and ability’” (Hopkins, The Canadian Review of Public Affairs 1917 699). Using notions of Progressive efficiency against a background of government scandal, Foster was able to persuade the electorate to return the Liberals to power. The next section turns attention toward this Progressive Era and its influence on this important story of public finance in New Brunswick.

The Progressive Era and New Brunswick

18 The Progressive Era is generally regarded to have emerged in the early part of the twentieth century as a response to increasing industrialization, growing concentration of commercial interests, and a marked shift toward urbanization (Diner). As Diner shows, Progressivism encompassed a wide variety of themes that meant different things to various groups in society. For certain occupations, such as medicine, law, social work, and engineering, the Progressive Era is associated with expanding professional boundaries in order to achieve economic rewards, professional autonomy, and social status (Diner). These professions used their technical expertise to further these aims. And this rise of prestige and power for professionals created an entry point for technical and managerial expertise in both business and government (Haber xi). Inside government, this technical efficiency drive started at the municipal level, during the crisis surrounding the devastating hurricane that wiped out much of Galveston, Texas, in 1900 (Weinstein 96). The new administrators came to look on Galveston “not as a city, but [as] a great ruined business” (96). One of the strongest promoters of business and professional management ideas at higher levels of government was the Progressive Era reformer, Robert M. La Follette. As governor of the state of Wisconsin, La Follette’s reforms early in the twentieth century had the marks of business language and methodology. In Wisconsin, “accounting, along with such other calculative techniques as statistics formed a ‘hard inside’ of bureaucratic structure which seemingly displaced the subjectivity of vested interests” (Covaleski and Dirsmith 169).

19 After Robert Borden’s election as prime minister of Canada in 1911, this language of efficiency entered the Canadian federal scene. The new government determined quite quickly that at “the very heart of everyday government and administration, was a massive tangle of inefficiency and incompetence” (Brown and Cook 193). Borden tried to undo the tangle through three separate interventions: centralization of government purchasing activity; setting up a Public Service Commission to increase efficiency and co-ordination; and commissioning a broad study by Sir George Murray, a former permanent secretary to the British Treasury, who “recommended a complete overhaul of Ottawa’s governmental machinery” (Brown and Cook 194).

20 Progressive Era reform also occurred in New Brunswick. In 1910, the Hazen government launched one such reform when it created a Board of Public Utilities Commissioners to establish rates for utilities (Babcock 8). One of the key areas of New Brunswick’s public administration to feel the Progressive influence was forestry, the province’s largest industry and its largest generator of public funds. Foresters began to make strides toward professional status in the 1890s (Parenteau 122), and “in the wake of the Crown lands scandal, New Brunswick made steady progress toward progressive forest management reform” (133). For example, in 1916, the Conservative government started an inventory of Crown timber resources under the direction of a professional forester, a graduate of the forestry program at the University of New Brunswick. And in 1918, the new Liberal government continued this trend to more technical management of forests by bringing forward two new acts: the Forest Act and the Forest Fires Act (Parenteau 121).

21 Similar to the foresters, accountants were also rapidly professionalizing. Just as La Follette used accounting as a tool for administrative reform in Wisconsin, the expanding accountancy profession was ready to help with administrative overhauls in various Canadian jurisdictions. One of the major firms of chartered accountants, Price Waterhouse, had begun to offer its assistance to provincial administrations experiencing financial system crises. In 1916, Manitoba was the first province to receive Price Waterhouse’s help. Following a change to a Liberal government (and hot on the heels of a scandal surrounding construction of the Legislature Building), Price Waterhouse carried out a special examination of the Manitoba finances (Hopkins, The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs 1916 645–6; Donnelly 94). Following this examination, Manitoba began using an outside auditing firm to provide assurance on the province’s quarterly financial statements. Manitoba also eliminated the provincial auditor position and replaced it with a comptroller general model.

22 Price Waterhouse carried out a second Canadian engagement following a change in government in British Columbia. Premier Brewster (representing a Liberal party which had defeated a Conservative government) employed Progressive Era rhetoric, noting that when his government took office on 29 November 1916, it instituted a policy that “finance was to emulate the system of a well-conducted business or corporation” (Hopkins, Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs 1917 830). Further, he informed the legislature “that he had immediately engaged Price Waterhouse & Co. to inquire into and report upon the financial condition of the Province” (830). The Liberal party in New Brunswick would follow a similar strategy by employing Price Waterhouse shortly after the Conservative government was defeated.

The Foster Administration, Price Waterhouse, and Progressivism

23 As soon as the House opened on 10 May 1917, the new Foster Liberal government turned its attention to improving the province’s systems of financial management. Initiating a practice that has continued to the present in New Brunswick, the new administration brought in an outside auditor to give a true picture of the province’s financial position. The speech from the throne clearly indicated as much, stating that “In order to ascertain in an authoritative form the actual financial position of the Province,...a firm of Chartered Accountants of the highest reputation has been engaged to make a thorough audit of the finances and to report thereon” (Journals of the House of Assembly 1917 5–6). The speech also indicated these same chartered accountants would replace the province’s old bookkeeping methodology with “the most modern system of keeping the public accounts” (Journals of the House of Assembly 1917 5). Further, in that same speech from the throne, Lieutenant Governor Josiah Wood announced that among the list of legislative changes planned for that session, the Audit Act, last revised at the start of the Conservative’s 1908 mandate, would be amended (Synoptic Report of the Proceedings of the Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick 1917; hereafter Synoptic Report 1917). Changes were coming.

24 On 7 June 1917, the Foster government began to disclose more clearly just what sort of financial changes were required. C.W. Robinson, standing in for the ailing provincial secretary-treasurer, began the debates in the Committee of Supply by carefully detailing the extent of financial mismanagement the new government encountered upon entering office. Interestingly enough, he started his speech by referring to the early, more prudent days of the Conservative administration, telling the assembly that when the Conservatives delivered their first budget in 1908, they had promised that expenditures should not outstrip revenues. Yet, despite this promise, and the fact that the Hazen administration had taken power at a time of increased revenue, the Conservatives had not managed the public debt very well. In fact, Robinson added that the debt picture was occluded; the Foster administration needed to call in a professional firm of chartered accountants to ascertain “exactly how matters stood” (Synoptic Report 1917 85).

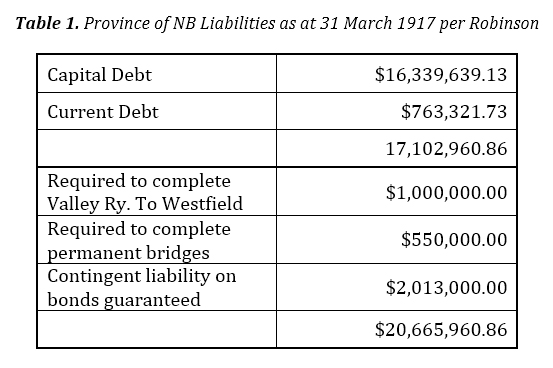

25 Not only, it seems, were the Conservatives full of graft and corruption, but it appears that they were not very good bookkeepers. Robinson noted that although Price Waterhouse was still preparing its report, it had provided the government some figures to use. After a brief interlude in which Robinson complimented the fine Canadian youth fighting overseas, he returned to “the question [that] was often asked ‘What is the public debt?’” (Synoptic Report 1917 85). Robinson began to answer that question, noting that, while it was difficult to pin down the exact amount of the debt, thanks to Price Waterhouse a new method “adopted here for the first time by the chartered accountants employed by the present administration” could provide some answers (Synoptic Report 1917 85). The Foster government appeared to be eagerly embracing the technical approach provided by the professionals from the accounting community. During the 1917 New Brunswick election campaign, the Liberal party had spoken of the province’s large $16 million debt. But using these modern techniques from Price Waterhouse, Robinson painted an even bleaker picture. Table 1 has been adapted from Robinson’s speech:

Rather than a reported debt of $16 million—a figure sensational enough to be a campaign theme for the Liberals—Robinson reported a debt almost 30 percent higher. He then proceeded to read from a detailed schedule of changes in the debt during the Conservative administration, the schedule itself covering about a page and a half in the Synoptic Report.

26 Robinson continued his speech by noting, “The Auditor General’s report was prepared by the Government which lately went out of power, and the present administration was not responsible for it” (Synoptic Report 1917 87). Lost on Robinson, apparently, was the irony that it had been a previous Liberal administration, of which he was a prominent member that in 1906 had started the auditor general reporting directly to the executive rather than the legislature, thereby impairing the auditor general’s independence.

27 Robinson returned to the importance of the administration relying on Price Waterhouse, stating that the Foster Liberals “had felt it their duty to have a statement made by independent auditors so that they would know exactly where they stood” (Synoptic Report 1917 87). Then, presaging the permanent changes to come in the audit regime, he added that “the only practical way was to have the accounts of the province audited each year by somebody not connected with the government” (88). “An independent auditor,” not the old, antiquated system of using an auditor general, “would not be subject to any political influence and his report could be depended upon as accurate” (88). Not only would this new auditing method be more accurate and independent, it would be progressive in both the political and the business sense. Robinson demonstrated as much by noting that “banks and large mercantile institutions had adopted this plan and had found it very satisfactory” (88). The implication was that if it works in business, it must work in government, an idea consistent with the political discourse of the era. This language reappears when Robinson later criticizes the former administration for not investing in Crown Lands sinking funds, thereby losing out on $25,000 a year. “That was not good business” (88) is his simple but telling statement to summarize the finding.

28 The list of inadequacies continued. Perhaps being a bit too modest, or not crediting appropriately the interim findings from Price Waterhouse that he was privy to, Robinson noted that “it seemed to him, speaking not as an expert, but as an ordinary individual that the methods of bookkeeping employed by the late government were capable of considerable improvement” (88). Robinson saw duplication in bookkeeping and felt that instead of several departments receiving government money, there should be one central receiver of all government cash. Further, “There was no proper control or system for managing sinking funds” and “neither did there appear to be sufficient control in the purchase of supplies” (88). Echoing findings from Robert Borden’s reviews in Ottawa, the supply system was called “haphazard” (88).

29 Harkening back, in a sense, to the claims of the disgraced Deputy Minister Blair, Robinson noted a tendency to omit certain expenditures from the public accounts. His great example of this tendency was a $1.7 million loan to the Valley Railway which Price Waterhouse, the independent auditor, had now classified correctly. But he also noted that the previous administration had failed to record operating expenditures associated with the Valley Railway in the proper manner. Fortunately, here too Price Waterhouse could help by advising the government on correct business methods. This failure to properly handle the railway transactions was just one more reason to overhaul the bookkeeping system. Robinson also offered that “the Audit Act did not appear to be the protection of public funds that it was supposed to be” (Synoptic Report 1917 87). The changes to the Audit Act briefly alluded to in the throne speech were going to be needed to strengthen the province’s financial management framework.

30 No doubt those present in the legislative assembly that day were well aware that just down the street at the County Courthouse, J.M. Stevens was leading the Foster government’s commission to investigate the St. John Valley Railway (Doyle 155). It was probably an uncomfortable moment for both the members of the opposition and Loudoun. Perhaps this discomfort explains why the Conservative opposition did not offer much of a response to Robinson’s speech at the time, though Hopkins tells us that at some point in the session two Conservative members offered a “great mass of figures” in their attempt to validate a lower amount for the public debt (The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs 1917 705).

31 On 21 June, two weeks after Robinson’s speech, the government tabled the full Price Waterhouse report. While it was couched in the careful, conservative language often characteristic of accountants, the report reinforced the notions raised by Robinson, making various recommendations for improving the province’s accounting system. Price Waterhouse noted how New Brunswick, like many governments, had omitted certain liabilities from its public accounts, failing to follow “the principle of stating accounts on a ‘revenue’ basis…universally followed by financial and industrial companies and railroads” (Price Waterhouse 2). The New Brunswick government was obviously not very businesslike in not following this “revenue” basis of accounting. The accounting firm also found fault with the province’s system of recording expenditures, showing that by failing to include certain expenditures, the previous government had turned what should have been a deficit into a surplus of $12,077. Here is another element of discourse that has continued to our day, where new administrations seem to frequently disparage previous incumbents for misreporting the state of public finances.

32 A third key matter raised by this outside accounting firm involved the government’s failure to record a direct liability for the Valley Railway. It was but “another illustration of our point that the Published Accounts do not reflect the financial position of the Province in a sufficiently clear and intelligible manner” (Price Waterhouse 3). Price Waterhouse then turned their attention to such areas as the uncollectable nature of certain amounts owed to the province and the rather loose fashion in which certain securities were stored in a safe that could be accessed by a number of staff, versus the more prudent practice of depositing them with a bank or trust company.

33 The report also made a number of broad criticisms of the provincial accounting systems and methods, an indication that modernization was required. Duplication of effort was certainly one problem. The auditor general and the treasury both appeared to have identical records of cheques written. Work was spread out in various departments. Price Waterhouse’s answer to all this, “from a business standpoint,” (6) was to centre responsibility in the Treasury Department. Further negative reflection came from Price Waterhouse’s statement that “the check which the Auditor General is able to expenditure appears to a large extent perfunctory, since he has no previous knowledge of prices and other conditions affecting the payment” (8). In addition, there was some duplication of work between the auditor general and the internal audit function. Building toward a grand recommendation, the consultants offered their opinion that one official be placed in charge of all the accounting work for the province, one official with responsibility to ensure the accounts of all departments were kept correctly. Perhaps, they argued, this could be accomplished by increasing the current auditor general’s powers. Or, Price Waterhouse noted, the answer might be to create a new office “under some such title as Comptroller General” (6). Regardless of what this new office might be called, it required real power “to exercise an effective check over all transactions connected with the receipts and disbursements of the Province, and not merely be in a position to pass upon their clerical accuracy” (Price Waterhouse 8), another apparent swipe at the existing system.

34 The accounting firm set the groundwork for new audit legislation by bringing forward this notion of a new officer called the comptroller general. Perhaps the Foster administration’s consultants from Price Waterhouse made reference to this comptroller general model because it had already been implemented following the accounting firm’s engagements in Manitoba and in British Columbia. In both of those provinces, as noted above, a new administration engaged Price Waterhouse to review the financial affairs of their predecessors when a Liberal government was elected after a financial scandal. Price Waterhouse, then, appears to have developed a standard recommendation to be duplicated in any Canadian jurisdiction to which they were invited. As their report concludes, “We should like to discuss this point at greater length at any time that is convenient to you, and in the meantime shall be glad to furnish you with any further information on the Accounts that you may desire” (8). Price Waterhouse would be only too pleased to provide more business advice on how the government of New Brunswick could transform its financial systems to modern businesslike methods. Of course, the fees from providing that advice certainly did not hurt Price Waterhouse in expanding its professional reach.

Conclusion

35 Following a series of financial scandals under the Conservative administration of James Kidd Flemming from 1912 through 1917, the Liberals under Walter Foster returned to power in New Brunswick. Against this backdrop of corruption, the new government advanced a program of financial reform in New Brunswick, turning its attention to improving financial systems and practices. This program of reform began with an external audit of the province’s accounts by Price Waterhouse, chartered accountants, and reached its legislative conclusion in April of 1918 when the legislative assembly passed a new Audit Act. Consistent with the model established in the provinces of British Columbia and Manitoba, New Brunswick’s new legislation implemented a new officer called the comptroller general. The comptroller general, rather than being an independent auditor, was to be the chief financial officer of a more centralized government administration.

36 In addition to looking at how an accountability crisis led to these changes in financial systems, this paper shows how the change from an auditor general to the comptroller general was a reflection of the general Progressive Era trend in North America at the time, a trend to de-politicize or professionalize the civil service—to make bookkeeping more businesslike. And, in looking at the part played by the accounting firm Price Waterhouse, we can see the emerging influence of the accounting profession in early-twentieth-century society. Indeed, the Price Waterhouse promotion of a comptroller general model in three provincial jurisdictions offers an opportunity for future research in the study of professionalization in Canada.

37 Certainly, this financial reorganization program offered by both the incoming government and their consultants from Price Waterhouse was a means to modernize and improve financial management. Changes to the province’s accounting systems probably were beneficial and inevitable. But one important piece was lost in the new, more professional approach. With the disappearance of the auditor general, and the appointment of a private sector auditor reporting to the executive, the legislative assembly lost an element of control over financial transactions. We can see how this loss of control might impact the relationship between the executive and the legislative assembly when we look at a more modern situation in New Brunswick, the so-called Atcon affair. In this Atcon matter, the government of the day provided over $50 million in loan guarantees to a private company in a situation of great financial risk, despite having been advised by the civil service not to proceed. In very short order, the government guarantees were called by the financiers, leaving the taxpayers with a loss of millions. Let us say, for a moment, that the public sector auditor of today in New Brunswick was still a firm of chartered accountants, as it had been for fifty years in the twentieth century, and not an independent auditor general. Then, extending things further, consider what might have happened with the auditor’s report on the Atcon situation if it was addressed to the executive branch of government and not the legislative assembly. This report could have easily been locked away in some storage vault for years, never to see the light of day. It would simply be labelled as a private report marked as advice to the cabinet and therefore outside the scrutiny of the members of the legislative assembly, the press, and the public. There would have been quite a different level of accountability for those implicated in the Atcon affair—we might say no accountability—had the auditor’s report not been tabled in the assembly. The lesson is clear: direct reporting to the assembly matters when considering the accountability of the executive.

38 This elimination of the auditor general was an early step along a long road of deterioration in legislative scrutiny of government expenditures in Canadian jurisdictions, one that would result in the declaration of federal Auditor General J.J. Macdonell that “I am deeply concerned that Parliament...has lost, or is close to losing, effective control of the public purse” (Report of the Auditor General of Canada for the Fiscal Year Ended March 31 1976 9). In Canada, where models, programs, and practices are replicated throughout various Canadian jurisdictions, this loss of control did not happen overnight. In testimony before the Public Accounts Committee of Canada in 1970, Norman Ward noted how “it is a fact that every time anything has been done with the Auditor General’s powers, they have been substantially reduced” (339). While the opposition parties tend to love the auditor general and his or her reports, governments have a strong incentive to reduce the auditor general’s reach and powers. Indeed, in New Brunswick we have seen a practice of the executive slicing the budgets of the Office of the Auditor General for many years. Volume I of the 2013 Report of the Auditor General notes the funding challenges the office currently faces. As it attempts to build a professional staff complement that would allow appropriate audit coverage of government programs, the Office of the Auditor General of New Brunswick finds itself running behind the budget levels of other auditors general in this region (163–4). Accountability of the executive branch to the legislative assembly is impaired. The current administration in New Brunswick has responded to these accountability concerns by calling on the Office of the Auditor General of New Brunswick to accept a budget freeze (Huras A8). Somewhat surprisingly, the Conservative opposition voices were absent. The auditor general publicly responded by stating her case for more funding in the face of the government’s call for austerity.

39 But in the New Brunswick of 1918, an early loss of legislative control over public finance did not seem to generate much debate at all. The Foster administration’s new legislation concluded rather starkly in Section 44: “The Audit Act, being Chapter 25 of the Statutes of 1908, is hereby repealed and the office of Auditor General is hereby abolished” (Act to Provide for Auditing Public Accounts 186). This new legislation effectively ended the long history of the office of the auditor general in post- Confederation New Brunswick. It would not return for another fifty years.

40 Brent White is an assistant professor on the faculty of the Ron Joyce Centre for Business Studies at Mount Allison University.