Articles

“Our Isolation Is Almost Unbearable”:

A Case Study in New Brunswick Out-Migration, 1901–1914

Abstract

In the decade leading up to the First World War, New Brunswick was in the grip of a massive out-migration of its population. Queens County, a predominantly rural community of 11,120 people located midway between Fredericton and Saint John, was neither immune from nor ignorant of its effects. A cross-sectional analysis reveals that between 1901 and 1911, the county lost upwards of a quarter of its inhabitants. Economic motives, particularly the decline of the region’s shipbuilding industry and increasing specialization in agriculture, may have played a role in the migration of previous generations of residents; but, by the turn of the twentieth century, economic conditions were steadily improving. So why was out-migration so persistent? Anecdotal evidence suggests that rural communities such as Queens County felt isolated from the rest of the province—that modernity was seemingly passing them by.

Résumé

Durant la décennie qui a précédé la Première Guerre mondiale, le Nouveau Brunswick était aux prises avec une forte émigration de sa population. Le comté de Queens, une collectivité à prédominance rurale de 11 120 habitants située à mi-chemin entre Fredericton et Saint John, n’était pas à l’abri de ses effets et ne les ignorait pas non plus. Selon une analyse transversale, entre 1901 et 1911, le pays a perdu plus du quart de sa population. Des motifs économiques, notamment le déclin de l’industrie navale de la région et une spécialisation accrue en agriculture, auraient pu jouer un rôle quant à la migration des générations précédentes. Toujours est-il que, au tournant du XXe siècle, la situation économique s'améliorait progressivement. Pourquoi donc l’émigration était-elle si constante? Des faits anecdotiques laissent croire que les régions rurales, comme celle du comté de Queens, se sentaient isolées du reste de la province et qu’elles passaient à côté de la modernité.

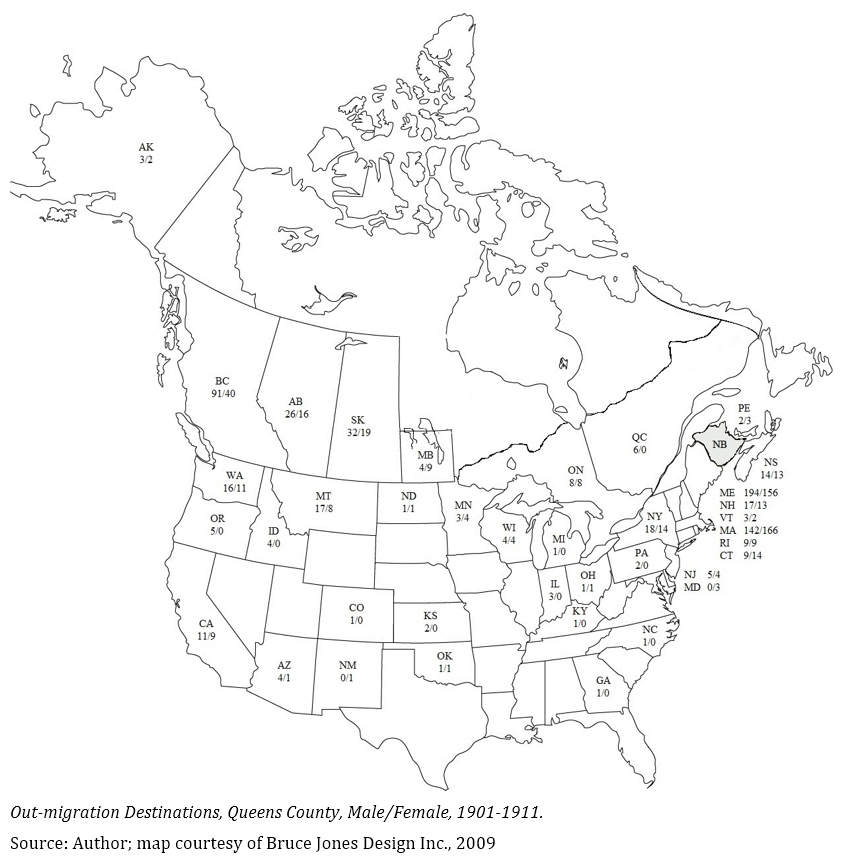

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 11 It was a bittersweet Christmas reunion for the Connors family of The Range, a community in Queens County, New Brunswick. Until their gathering in late 1903, the family, then numbering six children and several grandchildren, had not been together for over fourteen years. Some had moved to Saint John, others to Boston, leaving only son George, a surveyor, to tend their modest farm opposite Grand Lake.1 Upon retirement, parents Martha and William divided their time between the two cities until their deaths in 1913 and 1914, respectively. William Connors was not a wealthy man. His parents had escaped the Irish famine with little more than a few pounds sterling and good intentions; yet his eldest son would become a master mariner, another son a doctor, and a third a stone-cutter. Only his youngest son, Harry, would take up farming—an occupation that held uncertain prospects in the years leading up to the Great War.

2 That so many members from one family would leave home for destinations near and far was not uncommon in early-twentieth-century New Brunswick. Inhabitants of Queens County, located midway between Saint John and Fredericton along the St. John River, were all too aware of the exodus from their community. Between 1901 and 1911, out-migration claimed upwards of one quarter of the county’s 11,120 residents, part of an estimated 500,000 people who left the Maritimes between 1861 and 1921.2

3 In New Brunswick, newspapers regularly commented on the comings and goings of residents; yet, until 1911, when census data could no longer hide the fact that more people were leaving the province than were being added by natural increase and immigration, editorials rarely commented upon the outpouring of young men and women to New England, the Canadian west, and the Pacific northwest. As Betsy Beattie explains, at least for the women she studied between 1870 and 1930, “Leaving home to work in Boston and its surrounding communities was no longer novel. On the contrary, it had become so common that going to the ‘Boston States’ took on the aura of a youthful adventure, something not to be missed.”3

4 Maritime and New Brunswick out-migration has been the subject of intense scrutiny for well over half a century. The publication of Hansen and Brebner’s groundbreaking work, The Mingling of the Canadian and American People, 1604–1938, in 1940, followed closely by Leon Truesdell’s The Canadian-born in the United States, 1850–1930 in 1943, were the first to link the depopulation of the Maritime provinces to the decline of the region’s long-established “wood, wind, and sail” industries.4

5 This explanation, simple in design yet overly convenient, was expanded by Alan Brookes and his mentor T.W. Acheson in their examinations of Canning, Nova Scotia, and St. Andrews, New Brunswick.5 Both placed the blame for out-migration on the 1879 National Policy and the uneven economic development between central and western Canada and the Maritimes that resulted from the imposition of high tariffs. Although new industries were developed in an attempt to boost economic prosperity in the Maritimes and New Brunswick, they could not nearly absorb all of the labour that was displaced by the collapse of traditional staples industries. Consequently, as both historians point out, out-migration compelled a disproportionate number of young, unmarried men and women to move from rural to urban communities, and then out of the Maritime region entirely.6

6 Changing perspectives about the root causes of Maritime economic decline at the turn of the twentieth century may have been the catalyst underlying Patricia Thornton’s “new look” at the impact of out-migration on the Atlantic region.7 She questioned the accepted notion that out-migration was a by- product of economic underdevelopment, and instead offered an equally plausible suggestion—that depopulation was the root cause of the Maritime region’s economic decline at the end of the nineteen century.8 Her examination of out-migration from the perspective of Everett S. Lee’s lexicon of push and pull factors concluded that strong pull factors from destinations such as Boston resulted in greater selectivity at the point of migration.9 Consequently, migrants tended to be young, highly skilled, and included a much larger proportion of women than previously reported. It was the loss of this cohort through the rural-to-urban shift, she argues, that eventually robbed the Maritimes of the very stimulus it needed to grow.

7 Such thinking has propelled recent historiography in a number of exciting new directions. Rex Grady, in his examination of the lumber industry in Oromocto, New Brunswick, reminds readers that migration did not always favour a rural-to-urban shift; on the contrary, many residents engaged in primary industries moved to other regions of the province where resources and agricultural land was still plentiful.10 Betsy Beattie has embraced Thornton’s finding that women were an integral part of the migration experience, accounting for more than half of all emigrants. Economic opportunism, she argues, was a strong motivating factor for both sexes; however, “different gender expectations meant different choices, destinations and experiences for women versus men.”11 Consequently, men may have ventured farther in the accumulation of wealth, but women led the rural-to-urban shift, maintained strong social and economic ties to their families back home, and played a critical role in encouraging chain migration.

8 In his case study of Burton Parish, New Brunswick, Timothy Lewis offers an interesting counterpoint to Thornton’s economic premise. While regional underdevelopment was at the root of Maritime out-migration, Lewis argues that rather than creating social instability, out-migration “left the region with an increasingly stable population” of farm owners and their families.12 In this view, those who owned the land were less likely to leave it. Unfortunately, his concept of “persistence”—defined as the presence of at least one household member ten years after an initial census year—tends to underestimate the scale of Maritime out-migration and fails to address the societal implications of large- scale population movement. Rural communities may indeed have fared better by shedding excess farm labour and specializing production, but that was poor comfort for those residents without land holdings or other economic advantages during a period of increasing urbanization and industrialization.

9 Insofar as these studies offer tremendous insight into the social, historical, and geographic makeup of population movement in New Brunswick and the Maritime provinces, their preoccupation with an underlying economic motivation to explain population movement has overshadowed other mitigating factors. Scope is often their greatest deficiency. The scale of Thornton’s and Beattie’s work, although compelling, is much too large and rather abstract in its use of aggregate census data to truly define the out-migration experience; others, such as Acheson’s and Brookes’s, suffer from the opposite effect—their case studies are simply too small to answer much larger questions relating to motivation. What is needed—and what this article ultimately provides—is a case study of sufficient proportion to offer a more nuanced explanation for out-migration from New Brunswick in the early twentieth century. This paper challenges the placement of an economic argument as the centrepiece of current migration theory and argues that at the turn of the twentieth century, the driving force behind emigration had as much to do with feelings of isolation from the outside world as the potential for better wages elsewhere. Residents of Queens County, New Brunswick were tired of waiting for modernity to come to their doorstep: those with the means or the necessity could find all of the modern conveniences they were looking for only half a day’s travel away.13

10 Queens County has traditionally ranked as one of the least populated regions in New Brunswick. Its close proximity to Saint John and Fredericton, however, made it a popular destination for early French, Planter, and Loyalist settlement. Lowland farms, particularly along the St. John River and around Washedemoak Lake and Grand Lake, provided ideal soil conditions for the growth of hay and certain staples, most of which were consumed locally. The arrival of Irish immigrants in the mid- nineteenth century steadily increased the county’s population, although the limitations of farming along interior tracts tested even the heartiest of settlers. Many residents, eager to diversify and expand their meagre earnings, turned to resource-based industries, such as lumbering and fishing. In addition, new industries developed to profit from the transportation of raw materials to market. By the 1850s, as improved cultivation practices produced consistently greater surpluses of agricultural products for sale in Saint John, Queens County developed a small but vibrant shipbuilding and carrying industry. The latter created entire families of inter-generational sailors and shipmasters who plied their craft along the coastal routes of the Maritime Provinces and abroad.14

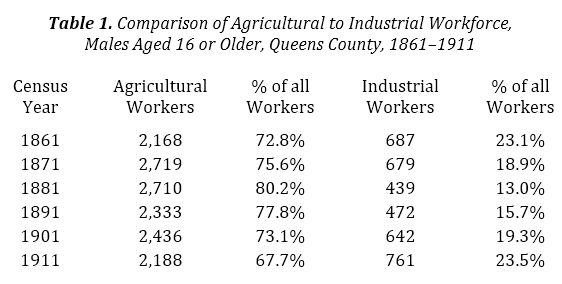

11 The late-nineteenth-century decline of the shipbuilding trade dealt a serious economic blow to small, partially industrialized communities such as Gagetown and Chipman. As carpenters and craftsmen moved their skills to larger centres, Queens County became even more dependent upon agriculture to propel its economy (Table 1). Yet, a number of factors limited the continued growth of farming in the county: the lack of capital to invest in larger holdings or improved technology; a limited availability of arable land; the necessity, particularly for interior farms with limited hay production, to import costly feed from Ontario and the west; the lack of year-round rail transportation; and the ongoing disdain for middlemen who exacted exorbitant profits at the expense of producers and consumers alike. “No wonder,” complained one Queens County farmer to the editor of the Saint John Daily Telegraph, “after an honest effort to make an honest living on the farm the farmer throws up the sponge in disgust and starts out in other pursuits.”15 County farms were being abandoned in alarming numbers.16 As New Brunswick’s Agricultural Commission wound its way through the county during the fall of 1908, one more complaint struck a common nerve—a distinct lack of farm labour to plant and harvest each season’s crops.17 Farmers’ sons had traditionally filled that role but, perhaps recognizing the limitations of modern farming, many had already left the county in search of other opportunities.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 112 “Our farms have been backward, not through lack of fertility, but through the appeal of the cities and of the West to young men,” explained the editor of the Daily Telegraph to readers anxious to understand persistent out-migration; “[the] exodus of laborers to harvest the grain crops of the West, thousands of whom never return, has been a heavy drain upon our province.”18 Many New Brunswickers regarded the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and their annual harvest excursion as one of the main culprits of out-migration. Each year, between two and four thousand labourers left the Atlantic provinces in pursuit of seasonal work in the west. Ever-expanding settlement and a corresponding increase in grain production demanded a large pool of temporary workers. Consequently, wages paid to farm labour were as much as twice what they were at home: $1.50 a day in 1903; $2.00 a day in 1906; and upwards of $2.50 plus board a day in 1908. Harvest excursions were a highly tempting proposition, made even more lucrative because the CPR charged only twelve dollars for the outbound leg of the journey west and a full eighteen dollars to return home again. It is estimated that upwards of 15 percent of harvesters remained in the west each year.19

13 It could be relatively straightforward, then, to privilege an economic root for the ongoing drain of the county’s population in the early twentieth century. Many New Brunswickers of the period expressed a similar conclusion: “There seems to be a feeling on the part of the young man that he can do better elsewhere than he can at home in New Brunswick,” commented one anonymous expatriate living in Illinois.20 Provincial teachers, who included a high proportion of women, frequently complained of being underpaid at home. George Harper, the son of a Chipman farmer, left his home for Wisconsin in the 1880s and spoke glowingly of life in the American west, stating that “there is a good living there for those who are not afraid to hustle.”21 Samuel Leonard Peters, a lifelong farmer and one of Queens County’s leading citizens, was quite certain of the connection between employment and out-migration:22

14 A closer examination of Queens County’s shifting economic foundation, however, reveals that not all was so dire at the turn of the century, thereby challenging the economic explanation as out- migration’s sole cause. Even as skilled labour was displaced by the collapse of the local shipbuilding industry, new industries began to emerge, promising jobs and prosperity to those who stayed in the county. A cheese factory, established at Gagetown in 1901, provided a profitable opportunity for local dairy farmers to dispose of surplus milk, particularly during the winter months when income was at its lowest. Only three years later, the Sayre and Holly Lumber Company established what was then billed as the largest sawmill in the province at its new location in Chipman. Efforts to attract an aluminum plant in 1903 and to exploit fireclay deposits in 1912 may have ended in failure; however, these large- scale attempts to kick-start the region’s economy only reinforced the impression with institutional investors that Queens County was rich in natural resources and ready to be exploited.

15 Coal, for instance, had been mined continuously for half a century in the vicinity of Grand Lake, but never in sufficient quantity to make its export economically viable.23 The earliest collieries were family-run operations, small and inefficient. Mine owners were confounded by the necessity of having to transport coal by horse and sleigh to Chipman, thence downriver by barge to Saint John. Even though most of the coal in the Grand Lake region lay a mere thirty inches below ground, the whole enterprise remained a costly and labour-intensive operation. Only with the construction of the Central Railway, which linked Norton to Chipman in 1888, and the completion of the Chipman-Gibson line in 1904 could large-scale mining above Grand Lake be contemplated.24 By 1910, the majority of local entrepreneurs had been superseded by American and Montreal concerns employing substantially greater capital, increased mechanization, and a substantially larger pool of skilled and unskilled labour. By 1913, almost two hundred men were employed by the newly incorporated Minto Coal Company, producing in excess of four hundred tons per day.25 With the accompanying formation of the Fredericton and Grand Lake Coal and Railway Company to transport coal westward rather than to Saint John, the CPR-backed Minto Coal Company rapidly eclipsed all other operations in the region, including the Rothwell Coal Company and the mining arm of the King Lumber Company.

16 Economic prospects in Queens County were further buoyed by the promise, but ultimately slow realization, of a new rail link between Fredericton and Saint John through the centre of the county. From the very start, the construction of the Valley Railway faced delays, numerous cost overruns, and opposition by provincial voters who saw the whole project as nothing more than political patronage toward rural constituencies. Indeed, plans for the actual route of the rail line were more often guided by political consideration than by engineering or economic necessity. For Queens County residents, the Valley Railway tapped “a country entirely cut off from modern transportation facilities during the winter season.”26 The feelings of the county were expressed by T. Sherman Peters, Justice of the Peace and secretary of the Gagetown Board of Trade, in a letter to the editor of the Daily Telegraph, 19 January 1915:27

17 Industrial expansion was seen as a cure for many of the province’s ills. New Brunswick lagged behind all other provinces but neighbouring Prince Edward Island in terms of capital investment, and shared unevenly in the economic boom that swept across the rest of Canada during the Laurier years.28

18 Successive provincial governments were convinced that only a massive infusion of public money would modernize the region and attract private investment. Rail construction was only the beginning: new roads were constructed; hydroelectricity was harnessed far upriver at Grand Falls; and at Saint John, substantial efforts were taken to construct a new steel bridge across the St. John River, to expand port facilities at Courtenay Bay, and to construct affordable new homes on the east side of the city. By the onset of the First World War, government had become fully invested in creating and maintaining employment for native, mainly urban, New Brunswickers. Strong urban growth may have masked more serious regional economic weakness, but the effects of such large-scale governmental stimulus were immediate and undeniable: while labour in much of Ontario and western Canada strained under the pressure of a continental recession between 1912 and 1914, New Brunswick continued to create jobs and attract investment.29

19 Certain jobs, however, were proving exceedingly difficult to fill by native New Brunswickers. Rail construction and coal mining demanded tremendous numbers of both skilled and unskilled labour, yet contractors, such as James Barnes Construction, found it increasingly necessary to import foreign labour to meet their needs and governmental deadlines: “A Clause in the contract stipulates that the constructing company shall employ only native labor,” observed Barnes, “but as the Coal and Railway Company are desirous of having the new line in operation as early as possible, a desire in which the government and the people share, it is not unlikely that the government will consent to a modification of the terms of the contract so that the contractors may import foreign laborers next spring, if they cannot procure sufficient native help.”30 It came as no surprise, then, that most of the labourers employed in the construction of the Chipman-Gibson line in 1902 were Italian immigrants brought in from New York.31

20 George McAvity, president of the New Brunswick Coal & Railway Company, similarly decried the lack of homegrown labour. By 1904, his company operated fourteen mines and employed several hundred men but, according to McAvity and his manager, they could easily employ double that number to increase production and meet growing demand.32

21 Miners for the New Brunswick Coal & Railway Company earned upwards of eighty dollars per month, almost twice the sum paid to harvest labourers. Still, Queens County men—those who were seemingly in the best position to take advantage of such local employment opportunities—loathed to work underground or in work camps.33 In 1901, when operations were small and family-owned, only fifteen residents called themselves miners; all but two were born locally. Ten years later, the number of resident miners had increased more than sixfold to ninety-seven; yet, only half were born in Queens County. Some intracounty migration did take place, but the bulk of population growth in Chipman and Canning Parishes between 1901 and 1911 was a result of foreign immigration. As residents continued to vacate the county for Saint John, New England, and the west, they were displaced in increasing numbers by British, Italian, and Belgian immigrants. Higher wages may certainly have drawn men and women elsewhere, but, at least for those who left Queens County after 1901, economic necessity appears to have been of decreasing concern.

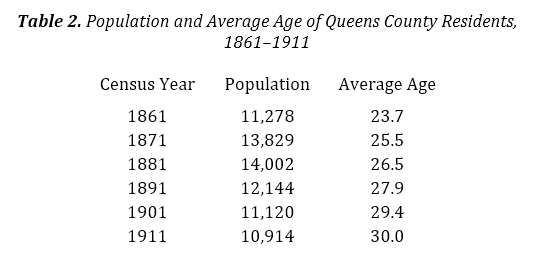

22 Recent historiography maintains that out-migrants were typically young, single, and equally divided between men and women. A close analysis of Queens County residents who emigrated between 1901 and 1911 confirms all of these trends. Migrants were undeniably young. They averaged 21.2 years of age or approximately 6.5 years less than the population at large in 1901, with the largest cohort of emigrants born between 1880 and 1885. This number is not to be confused with the age at which residents actually left the county. Where a specific year of departure is known—and taking into account children who were born in Queens County after 1901—the median age of both male and female migrants was twenty-four years.34 The net effect of such a focused migration was the gradual aging of the county’s population from 23.7 years in 1861 to 30.0 by 1911 (Table 2).

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 223 Migrants were also disproportionately single. Single males and females made up only 41.1 percent of the county’s population aged sixteen or older in 1901, but accounted for 65.0 percent of all migrants. Furthermore, when birth order and size of household are measured, out-migrants tended to be younger family members or members of larger families.35 They, more than their older siblings, were less likely to inherit property, to be less invested in the financial well-being of the home, and to be ultimately displaced by the increasing specialization of the family farm. For younger family members, future prospects typically lay outside the county rather than on the family farm. In contrast, married couples appear to have formed a bulwark against out-migration: between 1901 and 1911, only one in nine married residents left Queens County. Couples were generally older and more circumspect in their outlook. They were also bound by complex ties to the community: they owned the land; they paid a mortgage; and, more often than not, they had children to care for. The same could not be said of widows, who faced an uncertain future and difficulty maintaining the family home. These factors made them twice as likely as married couples to leave the county, taking their children with them.

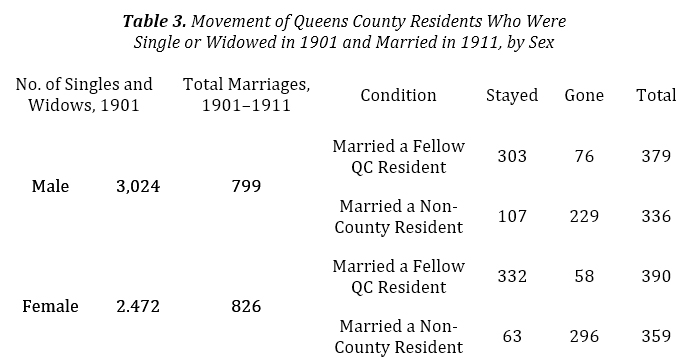

24 Marital status may have been an impediment to migration, but the act of marriage itself was not. Between 1901 and 1911, single and widowed residents were only marginally more likely to marry someone from Queens County than someone who did not reside there. Given the ratio of 122 eligible males to every 100 females, it is not surprising that female residents married a higher proportion of local men.36 That being said, as Table 3 illustrates, those men and women who married a local resident were far more likely to stay in the county; those who did not were considerably more inclined to leave. In all cases, whether it was by virtue of their economic prospects, the land they owned, social mores, or simple necessity, men were two-and-a-half times more likely to draw women to their location than vice versa. This includes almost eighty-seven women brought into Queens County from nearby communities to fill the void left by the shortage of women inside the county and another nineteen county women who joined former Queens County men after they had already left the county.

Display large image of Table 3

Display large image of Table 325 Evidence also supports the proposition that Maritime out-migration was an equal opportunity experience.37 At 21.6 percent and 22.1 percent, respectively, men and women left Queens County in almost equal proportion between 1901 and 1911. While migration among the sexes was fairly homogeneous across the county, certain anomalies stand out: in Cambridge and Johnston Parishes, male migrants exceeded female migrants by over 30 percent; in Petersville, the reverse appears to hold true. More substantial differences between men and women are revealed when one examines just where these migrants settled. Women tended to migrate shorter distances.38 They also outnumbered men in intraprovincial migration and migration to Massachusetts. Betsy Beattie offers a reasonable explanation for why the second generation of women tended to relocate to Boston and its environs: “These women were more often choosing jobs based on preference, not just family need; they were living more independently, spending more money on consumer goods and leisure activities, and, in some cases, preparing for long-life careers.”39 Such motives could easily explain female migration to other urban destinations, such as Fredericton and Saint John.

26 Queens County men were more independent and adventurous than their female counterparts and were far more likely to leave New Brunswick than women. They also tended to travel further in the process. Men may have dominated emigration to neighbouring Maine—many found the lumbering industry there to be more lucrative than in New Brunswick—but they also outpaced women in their migration to the Canadian and American wests. Professionals, such as doctors, teachers, and clergymen, were most likely to leave Queens County. While this appears to support Thornton’s contention that migrants were generally highly skilled, at only 3.3 percent of the adult male population, this coterie was the smallest occupation group in the county and ordinarily prone to movement as a simple function of their occupation.40 Farmers and farm labourers undoubtedly made up the largest block of migrants from the county; but, in terms of proportion, they formed a rather stable core and were the least likely to leave the county or to change occupations.

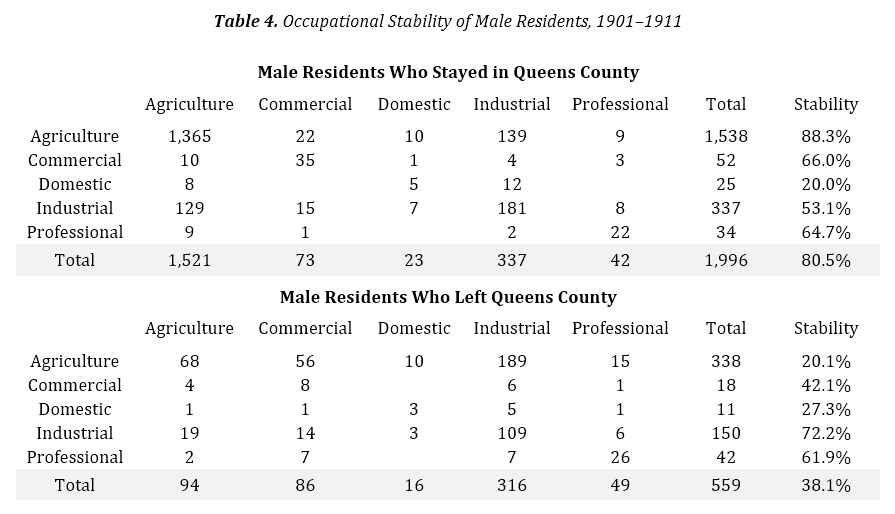

27 Occupational stability is an important measure underlying the out-migration process, more so than Lewis’s application of household persistence. An examination of occupational stability considers all residents, not just the heads of families, and compares the occupations of those same residents from one census to another. As Table 4 illustrates, men who remained in Queens County between 1901 and 1911 were 80.5 percent likely to stay in their occupation group. This percentage might very well have been higher but for the fact that 9.0 percent of farmers took up carpentry, mining, or general labour, while 38.3 percent of industrial workers, including a rather significant number of seaman employed in the carrying trade, switched to agriculture during the same period. Overall, farmers were the most stable occupational group; domestics the least.

28 The stability factor for those who left Queens County is significantly lower. Not surprisingly, 61.9 percent of all male out-migrants were likely to change occupations in this ten-year period. Industrial workers—carpenters, blacksmiths, and general labourers—and professionals stand out as the most stable occupation groups, easily transferring their skills from one location to the next. Only 20.1 percent of farmers, however, continued to practice their occupation outside of Queens County; even then, most remained in New Brunswick, taking up new properties in neighbouring Kings County or just across the border in Maine. The bulk of farmers who left the county preferred industrial work or took up commercial employment as merchants and clerks. The top destination for both groups of migrants was Saint John, although a fair portion of the former were drawn to lumbering interests in Maine or British Columbia, or any number of Boston-area mills.

29 Employment stability is a much more difficult concept to measure for women. Although invariably tied to the farm and the necessity for household production, only a small proportion of county women were classified into a traditional occupation group in 1901, making comparisons with 1911 nearly impossible. To what effect, then, can economic opportunism be measured for women? A simple examination of employment-aged women who remained in Queens County reveals that only 5.6 percent who were unclassified in 1901 assumed traditional employment ten years later. Domestics make up a sizeable portion of these women, as do teachers, but the largest proportion belongs to female agriculturalists—women who, by virtue of the loss of their husbands, assumed full responsibility for the family farm. In contrast, women who left the county were 19.4 percent likely to be employed in 1911. Whether they actively sought employment elsewhere or simply took advantage of new opportunities is impossible to determine. What is clear is that, as Beattie points out, there was a much wider variety to the types of employment available to women who moved away from the farm.41

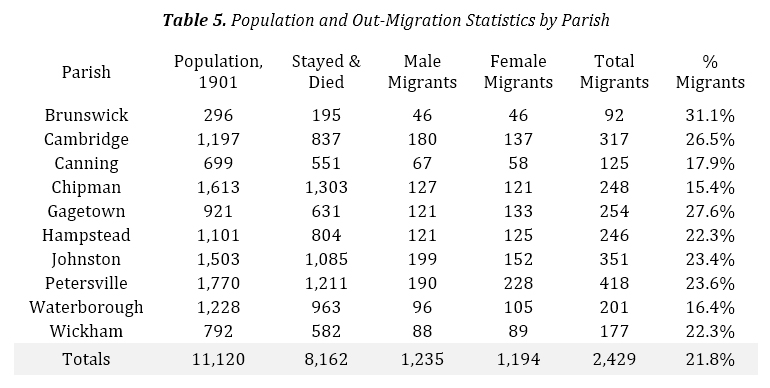

30 Out-migration varied widely among parishes. Chipman, Waterborough, and Canning each exhibited rates of out-migration below 18 percent (Table 5). None boasted a high percentage of population or land devoted to agriculture; however, those men otherwise employed in commercial, industrial, and professional work were much less inclined to migrate than men in farming communities. Clearly, the development of Grand Lake coal had a stabilizing influence on this entire region, allowing all but Waterborough Parish to boast the highest rates of intracounty migration (Table 6) and overall population growth between 1901 and 1911. The one contributing factor in Waterborough’s low rate of out-migration was that it sustained the highest ratio of married couples to singles.

31 Unfortunately, no common trend or influence helps to explain why Brunswick, Gagetown, and Cambridge Parishes had the highest out-migration rates in the county. Each lost at least 26 percent of their population; the former almost a third of all males and females. Brunswick Parish boasted the highest proportion of its workforce devoted to agriculture; yet, even farmers—traditionally the most stable occupation group—could not withstand the migratory influence on its small, predominantly single, and unusually young population who migrated at almost three times the county rate. Gagetown Parish had the second-highest proportion of singles and one of the highest concentrations of non- agricultural employees in the county. Unlike the expanding Grand Lake region, it did not have any long- term, sustainable industry to employ skilled labour. Consequently, while Gagetown gained internal population, its net population actually dropped between 1901 and 1911. Cambridge, just across the St. John River from Gagetown, remains the most enigmatic parish to explain. It did not have a disproportionate number of singles or young inhabitants; nonetheless, it suffered a net loss of 214 men and women in a single ten-year period. Although it was one of the most cultivated areas of the county, it, like Brunswick Parish, appears to have concealed a very unstable core of farmers. Curiously, the most unusual trend in Cambridge Parish was that over one third of all migrants chose to settle in Saint John, the highest proportion in the county.

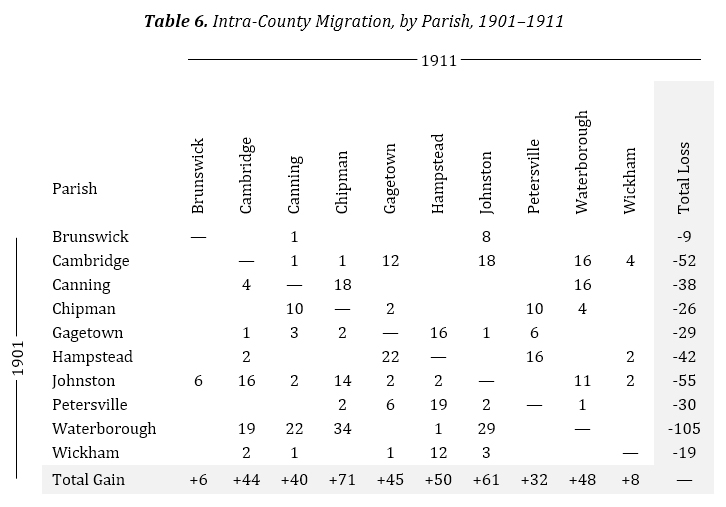

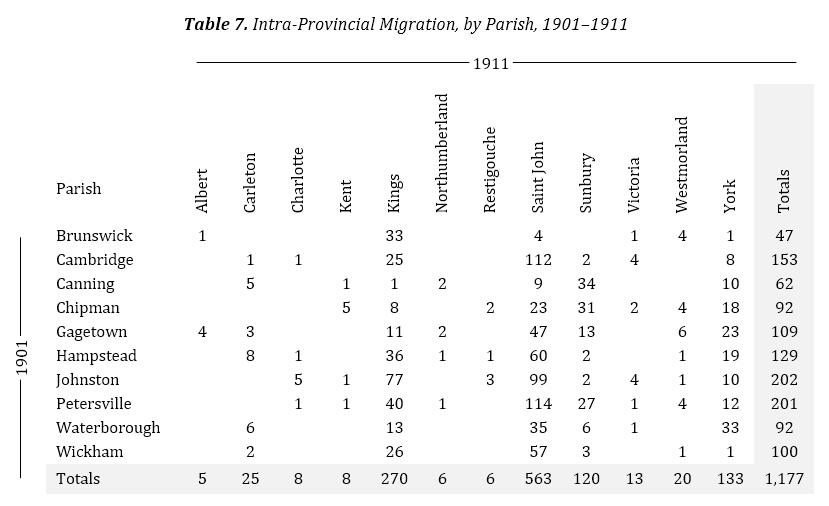

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 232 Saint John, particularly Lorne Ward, was a popular destination for both men and women. It was easily accessible—only a half-day voyage by steamboat—and flush with employment. It boasted theatres, department stores, and other modern conveniences not easily found upriver. Most importantly, Saint John served as a major transportation hub with ready access to almost any destination up and down the Atlantic seaboard. Opportunities could be found all along the lower St. John River. From Fredericton in the north to the Bay of Fundy in the south, almost 45 percent of all outmigrants remained within one hundred kilometres (sixty miles) of their original homes (Table 7). This is a rather sober statistic for a phenomenon that is thought to have emptied New Brunswick of its youth. It may be evidence of what Acheson describes as a two-generation pattern of emigration—the first generation moved to a nearby town; the second outside of the region entirely—or, equally compelling, the continuing effects of a rural-to-nearby-urban shift and long-term chain migration.42 In either case, one of the most compelling trends to consider is one that has been continually overlooked: the closer a migrant remained to Queens County, the more likely he or she moved with other members of their former household. Conversely, the further one travelled, the greater the likelihood that an individual would be isolated from others within their community. Familial ties were obviously an important consideration.

33 For those who left New Brunswick, western expansion and the promise of high wages drew many to farming in the Prairie provinces and to industrial work in British Columbia. In some cases, this was but a temporary stop on the road to Montana, Washington, and California. Surprisingly, Ontario was not a popular destination, even though factory workers earned an average of 32 percent more in cities such as Toronto than Saint John or Moncton.43 Proximity to New Brunswick was the major consideration for those who ventured to the United States. Maine and Massachusetts alone account for 72.9 percent of all American migration—26.4 percent overall—and were sources of good-paying commercial and industrial work for both sexes. It is folly to believe that economic motives did not have an impact on out-migration: they determined, in part, what communities were most affected; they influenced where many people would eventually settle; and they allowed a sizable number of women to embrace new opportunities and men to change occupations. Yet, many of the same economic incentives that existed outside of the region could increasingly be found within Queens County itself, without the corresponding higher cost of living. What other forces might have had an impact on who stayed and who left the county?

34 “Our isolation is almost unbearable and quite undeserved,” remarked S.L. Peters to a delegation of citizens at Gagetown in January of 1910.44 Many in attendance that evening were frustrated at the slow pace of rail development through the centre of Queens County, and believed that prosperity had bypassed their region. This was not necessarily true of the whole county, but few could argue that Chipman and Minto were quickly supplanting the county seat as the economic centre of the county, leaving communities on the western side of the St. John River abandoned by the provincial government, including their own member of the legislative assembly, H.W. Woods. This sense of social isolation was deeply rooted in the consciousness of Queens County residents. As urban centres grew larger, more and more resources were devoted to their comfort and care rather than to rural constituencies: “This isolated condition has become not only irksome and most discouraging to us, but is very seriously interfering with the progress and settlement of the St. John Valley and the thrift and prosperity of its citizens,” remarked H.H. McLean, the Liberal member of parliament for Sunbury-Queens; “[it] is also the immediate cause of a heavy drain on our population, through the emigration of our young people to western parts of the Dominion.”45 At the end of the meeting, resolutions were passed identifying the need to transport goods to market, to lessen the burden of isolation upon “our young people,” to demand fair treatment from government, and to draw affected communities together.46

35 This was no small task. In the first decade of the twentieth century, while much progress was made modernizing infrastructures, from electrification to sewerage, mail delivery to road maintenance, rural communities were often the last to see such improvements. Newly trained school teachers were reluctant “to go where conditions were unattractive and privations unavoidable.”47 Of the thousands of telephone lines installed in New Brunswick by 1911, only thirty-five private lines and trunk line exchanges could be found in Queens County.48 Almost half were located in Chipman. In effect, rural communities offered little inducement for either men or women to remain on the family homestead. “There seems to be a feeling on the part of the young man that he can do better elsewhere than he can at home in New Brunswick,” argued the Daily Gleaner in 1908. “This is particularly true of the many young men who have been reared on the farm. They believe they have worked too hard for the returns received and are willing to seek their fortunes in a new land or in a new section of the home land.”49

36 How can you expect the boy to stay on the farm, asked the editor of the Kings County Record, if you don’t treat him right? “For all their days they have submitted to drudgery, and have been taught by precept and example that a farmer must do the work before him nor ask the reason why.”50

37 Farming was undeniably difficult work. It was also highly repetitive in nature and offered few rewards but the satisfaction of being so closely connected to the soil.51 But even this attachment was under threat: “The son does not like to feel under the obligation of going to his father every time he wants a few cents for some expenditure,” quipped one observer.52 “To keep the children interested, we must be interested ourselves,” appealed Mrs. Chester Keith to the annual convention of the Women’s Institute in 1914; “a mother or father who is discontented and unhappy cannot expect to have a contented and happy family around them.”53 Children were not blind to the opportunities, the freedom, the amusements, and even the companionship offered by cities. It was the role of the parent, she and many others argued, to instill a deeper appreciation of the value of rural living within younger residents. Suggestions were often more plentiful than solutions. Critics decried the lack of formal agricultural training in the province, pointing out that farmers were often forced to travel to Nova Scotia and Ontario to receive advanced training.54 Others suggested the need to redefine the relationship between father and son; that the services of the son could be procured with other considerations besides room and board, such as a share of the proceeds from the sale of livestock.55 One source, the Kings County Record, went so far as to suggest that young men, even boys, should be made partners in the operation of the farm: “How many boys adopt professions and callings because of a hatred of the uninteresting life on the farm rather than from any special adaption he may have for the profession chosen?” it asked of its predominantly rural readership. “It should be the purpose of the parent and the teacher to present to the boy the business of farming in such a way that its advantages, as compared with other pursuits may be fully realized.”56

38 Governmental reaction to such pressures was equally disjointed. Both Liberal and Conservative administrations were slow to recognize the peril underlying successive census reports. The rural-to- urban shift was seen, at first, as an unavoidable process, to be encouraged so long as young men and women stayed in the province. Consequently, it was the role of government to find work for rural youth who moved to the city by encouraging the development and expansion of the manufacturing industry. When this failed to curtail provincial out-migration, efforts were made to direct New Brunswickers westward rather than to the United States. Potential migrants, however, did not need any further encouragement to move west. The siren call of the Prairies and British Columbia was strong, perhaps too strong for certain critics back home: “The population that is swinging into the West and the development that is taking place there cannot fail to appeal to him unless reasonable scope for his ambition is given to him here,” argued the editor of the Daily Telegraph.57 “Everything western is extolled,” wrote E. Russell of St. Andrews, “from the scenic beauty of its lofty snow-clad mountains to the immense wealth supposed to exist in its undeveloped mines. Reading people everywhere are influenced by what they read—if they read it often enough. It becomes the topic of conversation. Enthusiasm is infectious.”58 Dr. James W. Robertson, of Ontario’s Macdonald College, offered a simple solution to the problem of western migration when he addressed the agricultural committee of New Brunswick’s Legislative Assembly in 1908: “A prosperous, contented and intelligent people living on the land was the best asset that any country could have....If the west beguiles the young people, give them information and demonstrate the possibilities of New Brunswick.”59 George H. Clark, seed commissioner for the Dominion government, could not agree more. He conceded that young Maritime men were infected with the spirit of optimism that pervaded the West: “What was most needed among the farmers in the Maritime provinces was that they should come to know better the advantages of both the east and the west and better appreciate the natural resources that they had at home.”60

39 1908 was a critical year for out-migration in the province of New Brunswick. A nine-month recession reminded Canadians that economic prosperity depended, in large part, upon external as well as internal market conditions. This message was painfully reinforced when, owing to an overestimation of labour needs and a reduced harvest, thousands of Maritimers were stranded in the west with little work and no means of returning home again.61 Harvest excursions had always been tolerated as a necessary evil. They provided a release valve for some of the more adventurous sons and daughters of the province; they supported the Canadian economy; but most importantly, they held out the promise that most would return home again at the end of each harvest with money in their pockets. The excursion of 1908, however, proved more than the public would tolerate. The Daily Telegraph, finding agreement among the province’s newspapers, called upon government, boards of trade, and both city and municipal councils to refrain from assisting the CPR “in the annual recruiting which has done so much in the past to deprive this province of a part of its population very greatly needed to do the work here at home.”62

40 Furthermore, newspapers now began to portray out-migration as a risky venture, fraught with physical, social, and financial danger. Migrants might realize higher wages in the United States or the West, many testimonials argued, but they also faced a much higher standard of living outside of the province that would erode their ability to save money. Granted, a few of the more industrious men and women would succeed, even prosper, but many more would toil with nothing to show for their efforts but frustration and disappointment: “Men seemed to become dissatisfied here, because in a rather easy way of going along, without putting forth much special effort or adopting the best methods, they could not make money rapidly,” argued Charles Henry Peters, a Saint John merchant with strong familial ties to Queens County; “but when they went west they were compelled to work very much harder, endure greater hardships, and no doubt in many cases...they were disappointed in the end.”63

41 “Year after year our young men, and our young women too, are leaving us—sometimes to their advantage; often the reverse,” cautioned the Daily Gleaner.64 Toward the end of the decade, New Brunswick’s press began to focus their attention on the plight of migrants who failed to succeed and who ultimately returned home. Every success story was tempered with the warning that these migrants were the exception rather than the rule. When this message failed, New Brunswick outmigrants were shamed into staying at home. Provincial farms were better than those in the west, many argued; and if as much effort was put into farming at home as it was in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, or Alberta, wrote the Daily Telegraph, there is little doubt that agriculture in the province would be better off as a result. As New Brunswick’s economy continued to gain traction,

42 “Stay home, young man” was the rallying cry of the day. The message was clear, but ultimately found only indifference in the upriver counties. Between 1901 and 1914, New Brunswick had lost as many residents to out-migration as they had gained through immigration and natural increase, particularly in its rural counties. Rural conditions were such that they would not be easily displaced by the prospect of something better over the horizon.

43 This cross-sectional analysis of Queens County’s eleven thousand inhabitants between 1901 and 1911 confirms previous trends: young, single men and women did lead the out-migration experience. Of course, this comes as no surprise to those historians who have yielded similar results; but, in spite of the power inherent in their longitudinal studies, the overly narrow or too-broad scope of their examinations has sometimes masked the subtleties that lie just below the surface of migration theory. This study corrects that deficiency and, in the process, adds new dimensions to be considered: out-migration tended to claim younger siblings from larger households; men travelled farther, even as a sizable portion changed occupations; female migrants were far more likely to seize employment opportunities than had they stayed at home; and family members who migrated together generally travelled the shortest distances.

44 A better understanding of who migrated may ultimately reveal why they left rural New Brunswick in such large numbers. For previous generations of residents who were displaced by the loss of local industry and increasing agricultural specialization, emigration may very well have been motivated by simple economics, but in the decade leading up to the First World War, economic conditions in and around Queens County looked very promising. Was it too late to stem the tide, or had the uneven development of modernity eroded the will of a people who now came to view Saint John, Boston, and Vancouver as attractive alternatives to rural toil? Anecdotal evidence suggests that at the turn of the century, the driving force behind emigration had as much to do with feelings of being isolated from the outside world as the potential wages one could earn there. Residents were tired of waiting for modernity to come to their doorstep: those with the means or the necessity could find all of the modern conveniences they were looking for only half-a-day’s travel away. For many residents who tired of rural living, out-migration was a very simple solution to a very old problem.

45 Captain (Retired) Curtis Mainville is the author of Till the Boys Come Home (2015) and founder of the New Brunswick Great War Project, which is dedicated to the study of the province’s wartime contribution.