Articles

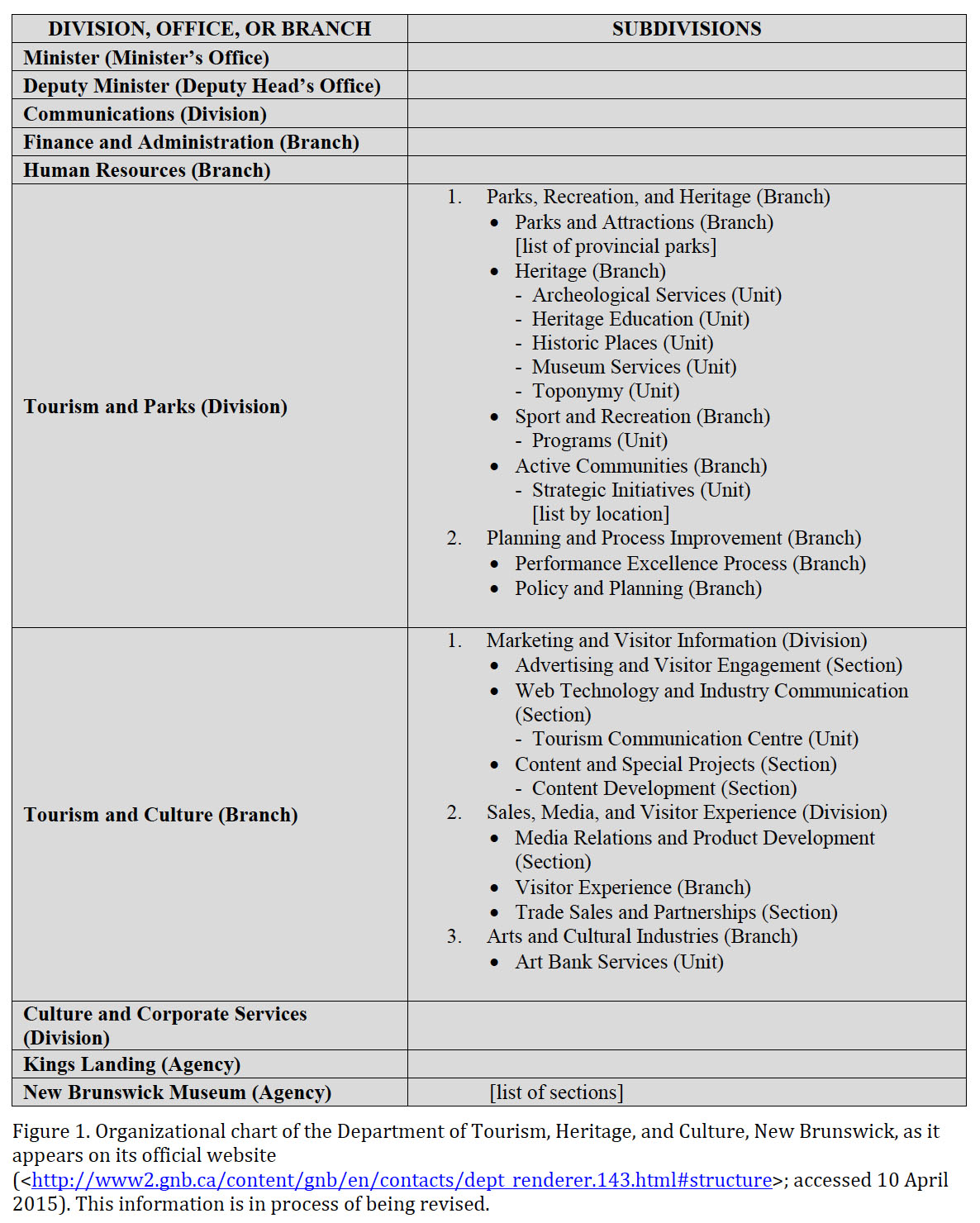

New Brunswick Artists in the Context of Small Communities:

Interviews with Suzanne Dallaire and Thaddeus Holownia

1 In a province currently plagued by a budget deficit and considerable debt, investment in the arts may seem wasteful or overindulgent. Is this investment a legitimate outflow from the government budget and an expense justifiable to the taxpayers? Does the order of the three branches listed in the ministry under the responsibility of which the visual arts fall—tourism, heritage, and culture—reflect its actual priorities and determine which initiatives are primarily funded by its budget allocations? When one examines the organizational chart of the current ministry (Figure 1), which lists the division of Tourism and Parks first and the branch of Tourism and Culture second, and classifies the heritage sub-branch under the branch Parks, Recreation, and Heritage attached to the former, it becomes quickly apparent that its largest and chief division is listed at the top and that a corporate terminology is employed to designate its components and activities. Where do contemporary artists and the visual arts fit into this administrative framework? Under the Arts and Cultural Industries branch, which is attached to the Tourism and Culture branch? Interestingly, it is easier to find an appropriate place for the artists who have passed away, as their artworks could be claimed by the Heritage Education unit or belong to the New Brunswick Museum, which is an agency under the responsibility of the same ministry and figures prominently on the chart. By comparison, the Ministry of Tourism, Culture, and Sport of the province of Ontario transparently assigns a prominent place to Arts and Artists under its Culture branch, while the Department of Tourism, Culture, and Recreation in Newfoundland and Labrador includes an Arts Division and an Arts and Culture Centres Division under its Culture and Recreation branch.

2 Does the corporate chart and the explicit mandates governing the operation of each unit in the Ministry of Tourism, Heritage, and Culture in the government of New Brunswick suggest that arts and artists in this province are judged according to, and consequently must find ways of fitting into, a business model that takes into account factors such as financing and profitability, capacity building and asset management, and measurable impact on the provincial economy, in particular the tourism industry overseen by the same ministry? And, more importantly, given the focus of this special issue of the Journal of New Brunswick Studies, what is the impact of this tacit prioritization and way of thinking as well as the fluctuating provincial and federal funding designated to the arts and culture on artists and small communities in this province?

Display large image of Figure 1

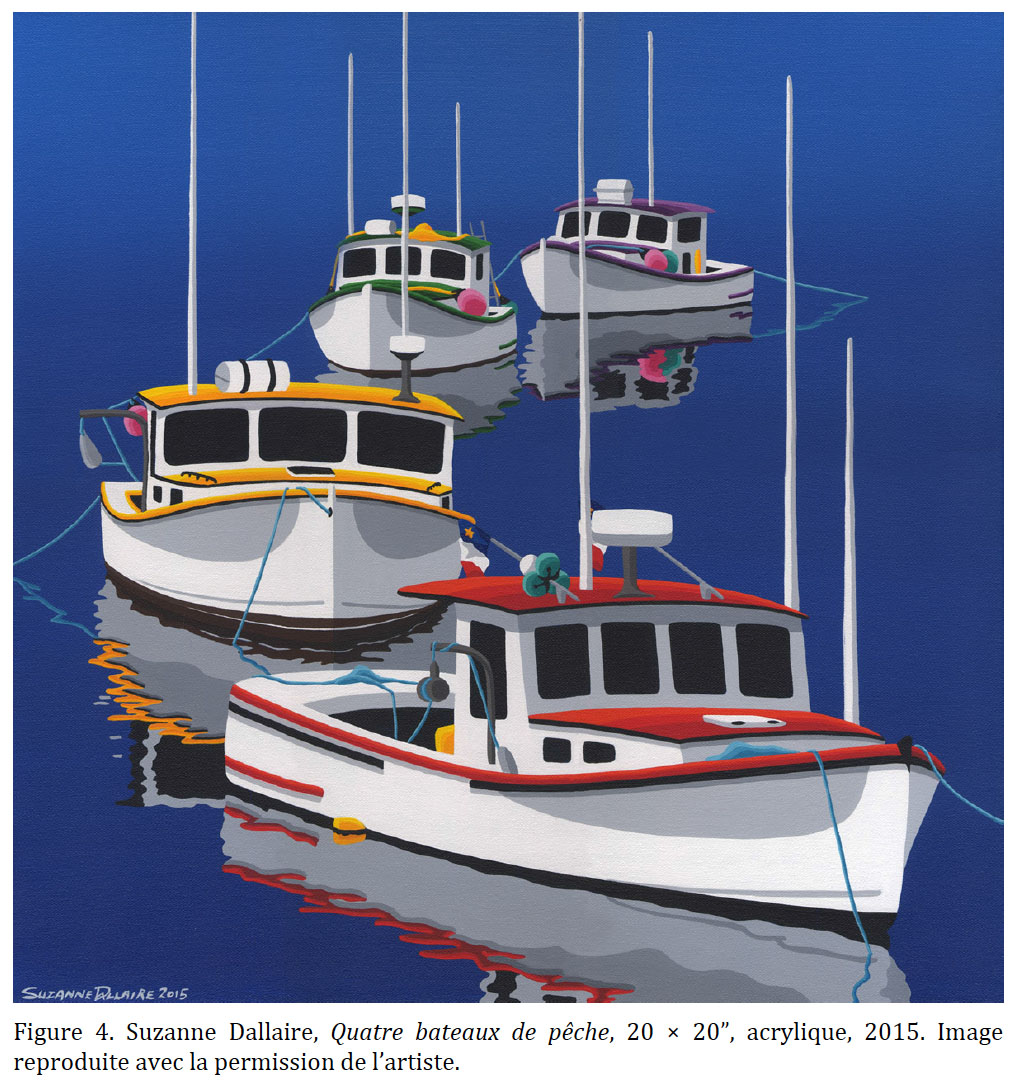

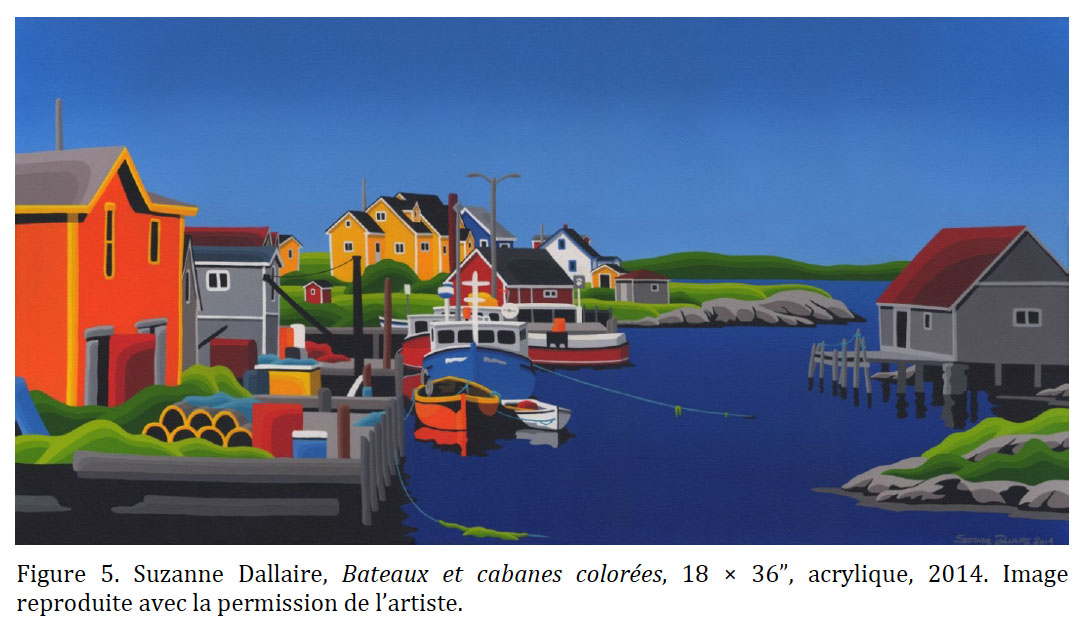

Display large image of Figure 13 The impact of the arts on an individual resident is assessed by researchers in terms of health, cognitive/psychological, and interpersonal effects, while at the community level, it is based on economic, cultural, and social implications. The importance attributed by New Brunswickers to the arts was the subject of an important study conducted in 2008. The Canada Council for the Arts partnered with the New Brunswick Arts Board, the New Brunswick Department of Wellness, Sport, and Culture, the Department of Canadian Heritage, and the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency in an innovative pilot project entitled “Building Public Engagement in the Arts.” The results from this study that focused solely on the province provide us with invaluable information about and sharp insight into a subject fraught with subtleties and complexities because of its direct dependency on public opinion. A survey conducted as part of this study delivered, for instance, the following revealing statistics: 80 percent of New Brunswickers specified that the arts were somewhat or very important for their quality of life (compared to 20 percent who noted they were not very or not at all important); 89 percent remarked that the arts were somewhat or very important for their community; and 85 percent stated that government funding for the arts in their community was somewhat or very important (Canada Council for the Arts n. pag.). This survey reveals not only that New Brunswickers recognize the arts as being important to them as individuals and, at a collective level, to their communities, but also that an overwhelming majority of them support governmental investment in the arts at the community level, likely because residents of the province experience first-hand its effects at the local level. In the face of what thus appears to be unquestionable and quantifiable support for the arts from the citizens of New Brunswick, why are we still lagging behind other provinces in the assistance offered to our artists, in providing art education in our schools, as well as in developing and investing in programs that support the arts in our communities? A bright ray of hope is on the horizon. Although it reads like a remarkably well-researched review of literature on the subject of the impact of arts and culture on the citizens of New Brunswick, a review peppered with inspirational quotes that are the trademark of a moving political speech, the document entitled “Creative Futures: A Renewed Cultural Policy for New Brunswick (2014–2019)” summarizes an initiative of the previous Progressive Conservative government and aims for concrete and realistic objectives that could translate into an increase in funding devoted to this area. One of its key actions, for example, is to “establish a one-percent public art policy for provincial and provincially-invested construction and development projects” (13). The plan strives furthermore to “encourage municipalities to establish a one-percent public art policy for municipal construction and development projects” (ibid.). It is only to be hoped that the strategy to establish an implementation plan and accountability framework for this cultural policy is not discarded by the current Liberal government in favour of more pressing concerns, as is often the case when a new party takes power in New Brunswick.

4 In an attempt to better understand the challenges faced by and specific issues preoccupying New Brunswick artists whose personal and professional lives are closely tied to small communities, we conducted interviews with Suzanne Dallaire and Thaddeus Holownia. Their backgrounds, careers, and current work and living situations exemplify notable oppositions (e.g., insider born here vs. outsider to the community; Francophone vs. Anglophone; female vs. male; painter vs. photographer; mid-career vs. established artist; graphic designer and professional artist vs. academic, printer, publisher, and professional artist). Their creative focus, however, is principally on New Brunswick, and their daily existence occurs in small communities of various types (rural neighbourhoods, the Moncton community of artists, the small undergraduate university, an intimate circle of aficionados of books as beautiful objects, etc.). As artists, they share a fascination with the distinctive landscape surrounding them and derive their creativity from a deep connection to a place and its objects. As New Brunswickers, they have developed an appreciation for a resilient way of life that has a unique rhythm and is rooted in a rich heritage. They hold as well strong opinions about the situation of the professional artist and the level of support provided for the arts in New Brunswick.

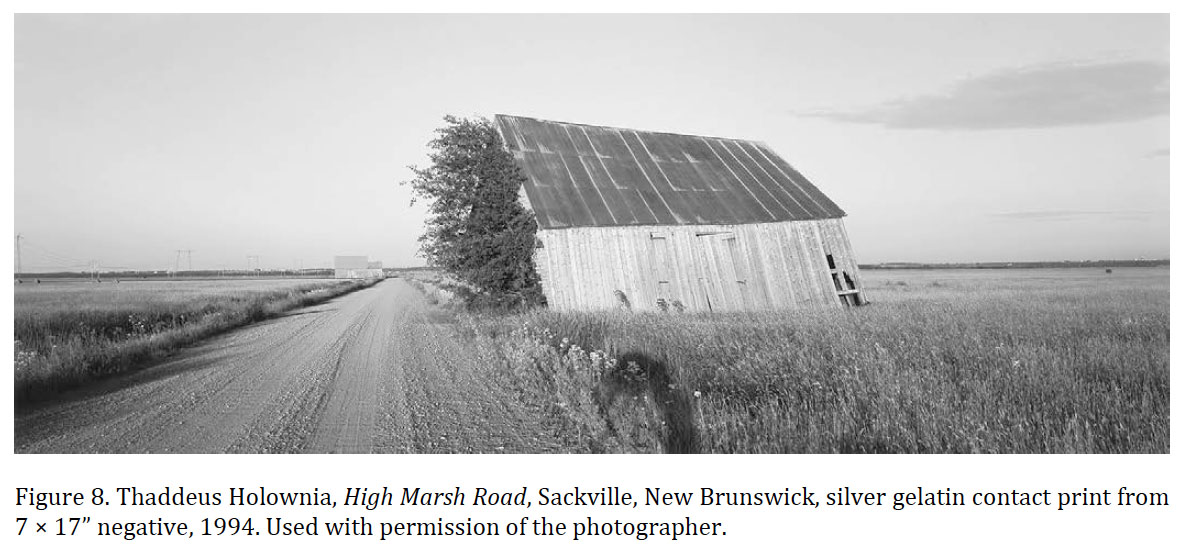

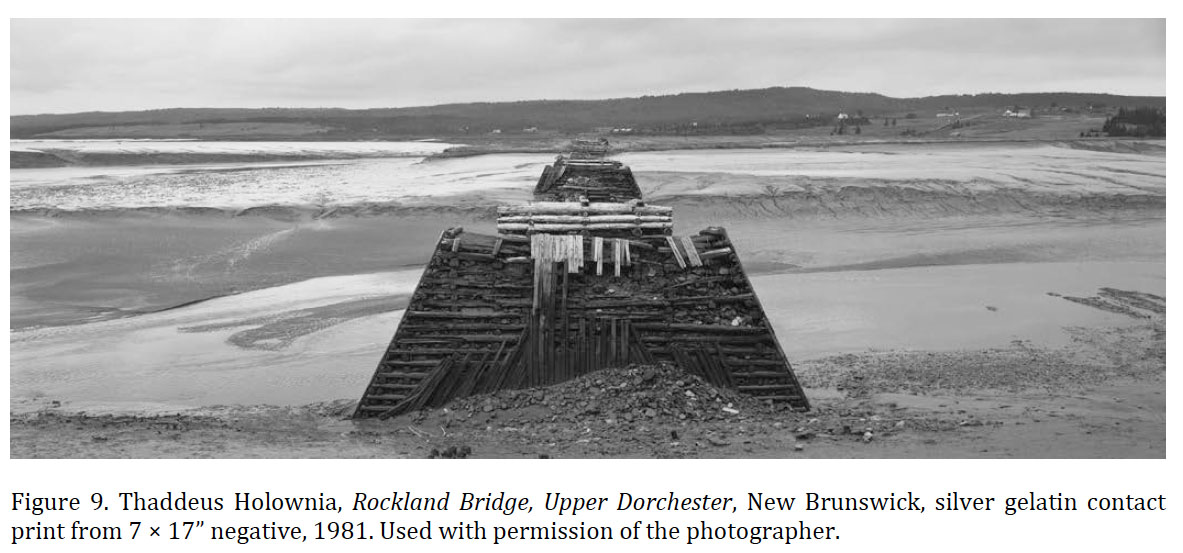

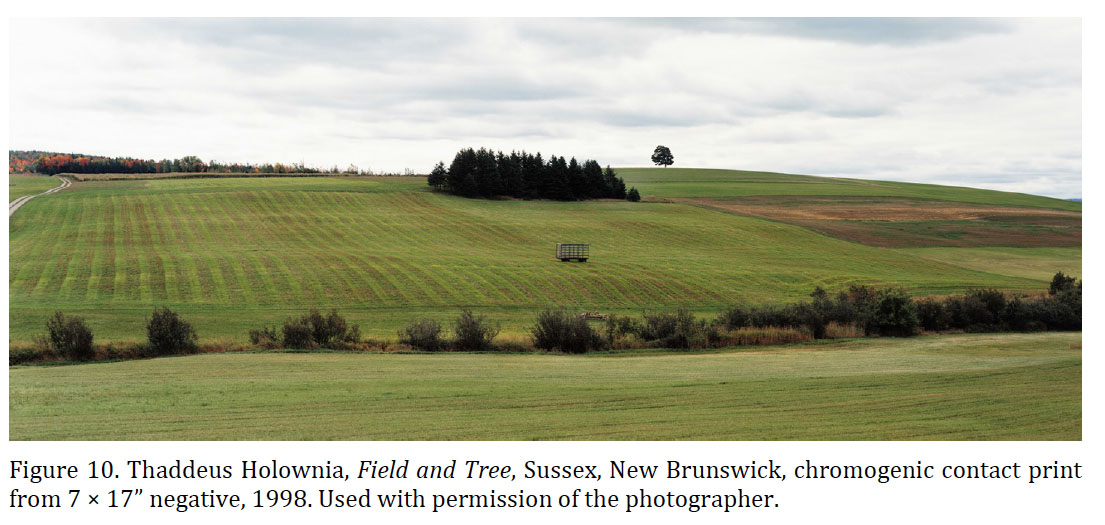

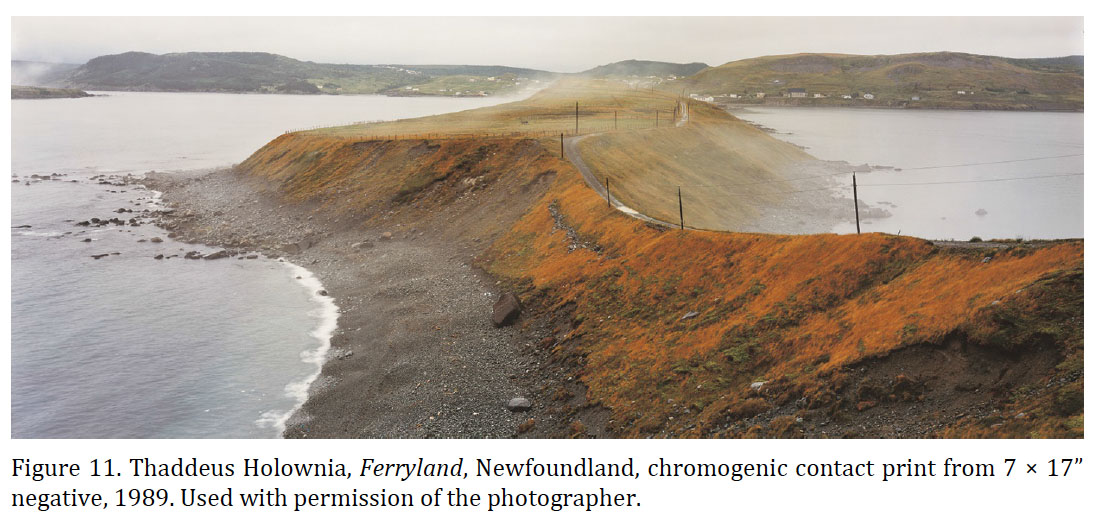

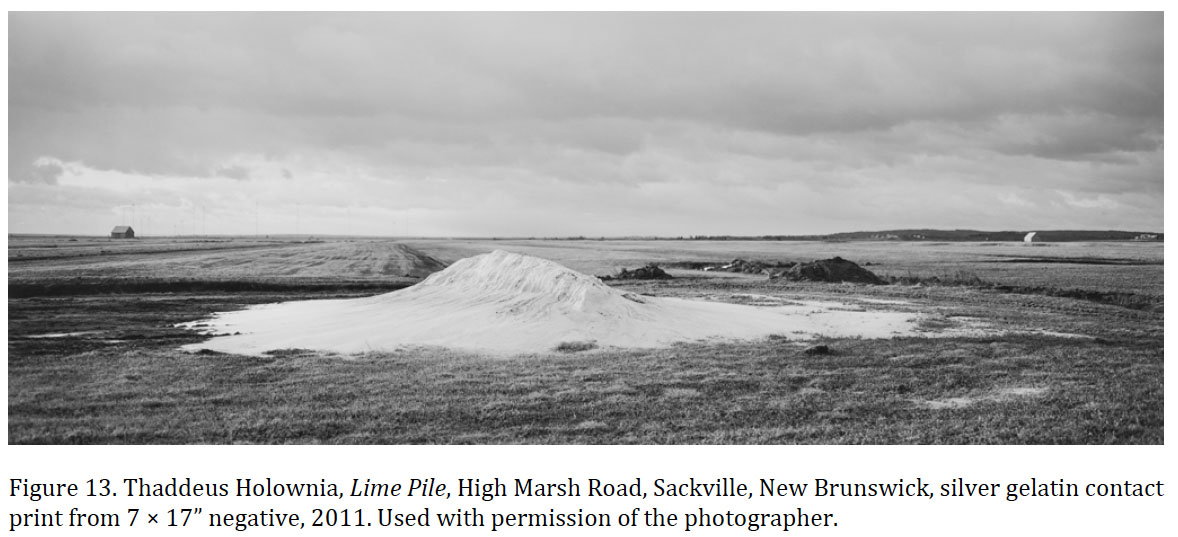

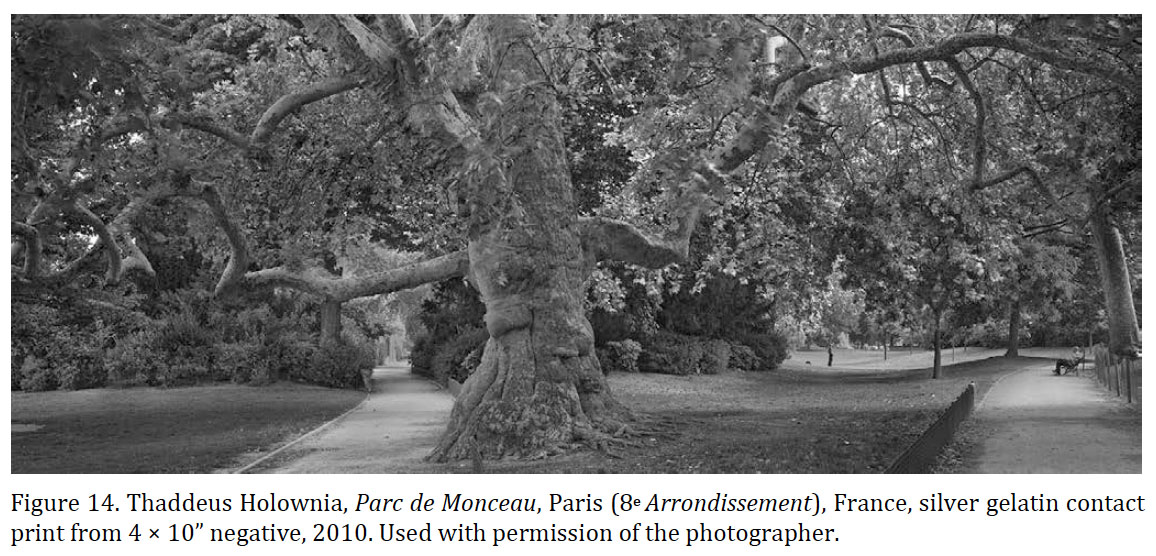

5 Although Thaddeus Holownia’s workshop is located along a dirt road in southeastern New Brunswick not far from the Nova Scotia border, the artist divides his time between this ideal, rural location and the small community of Sackville, where he teaches in the Department of Fine Arts at Mount Allison University. The landscape surrounding his workshop and academic environment becomes a natural subject for his photography, which showcases the seemingly familiar reality in an unfamiliar way. The photographer is interested in how landscape is transformed by or encounters human presence. His artwork thus engages with local communities in direct ways: not only does he shed new light on places and objects that are part of the quotidian existence of their inhabitants, but he also makes them accessible to a spectatorship beyond the confines of Sackville and its immediate vicinity. Through his images of the local landscape, the photographer opens a window into a corner of the world that wilfully remains somewhat remote, documenting a place that economic expansion and environmental change are bound to transform to the core in the twenty-first century. As an artist-scholar with an international portfolio that includes exhibitions and projects spanning continents, he embodies a harmonious symbiosis of the local and the global: he embraces one but does not reject the other, shrewdly claiming what he desires from each context. As an established photographer and tenured university professor, he can access various sources of funding for his projects and is able to travel beyond the Maritimes to places such as Toronto and Paris, to name only two of the urban landscapes on which he has intensively focused at various times in his long career. In spite of this privilege, he is astutely aware of the challenges facing the arts in New Brunswick and offers insightful reflections on a complex subject that he is able to view from different perspectives.

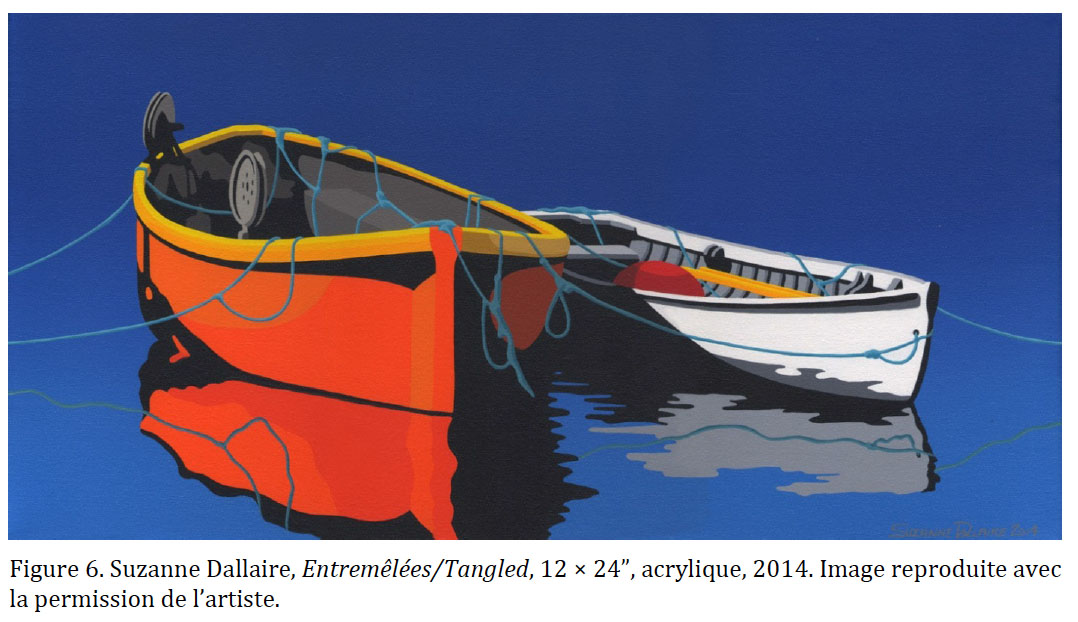

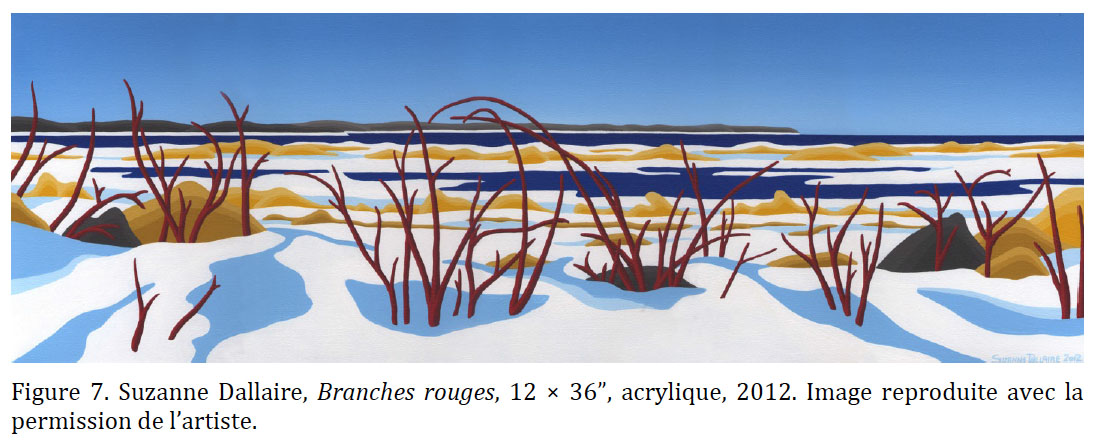

6 Based in Grande-Digue, a small community located in the predominantly Acadian region of Kent County on the northeast shoreline of Shediac Bay, Suzanne Dallaire is a professional artist whose paintings capture the Atlantic landscape and predominantly blue skies in vibrant colours and on rich surfaces. Her subjects are diverse: views of open fields and textured forests devoid of human presence; snapshots of coastlines with colourful lighthouses, beaches, fishing boats, and villages; and maritime vignettes that showcase places and objects. Her paintings convey a profound connection to landscape, particularly its water element—the omnipresent component of the Atlantic coastline and the interior of New Brunswick. For her, the arts constitute the heart and soul of a place; they are important because they bring beauty into the world and engender an aesthetic experience in the viewers that is transformative, restorative, and empowering. As most artists, she lacks words and ideas to further articulate the precise importance of the arts because il va de soi—it goes without saying—that they are important. In contrast to Thaddeus Holownia, she is labelled, according to her own account, a “commercial” artist. She does not directly benefit from any art grant or incentive programs administered by either the provincial or federal governments, or from institutional support such as the one normally offered by universities. She is a painter who relies solely on her art to make a living. And she is part of a select few to do so in New Brunswick.

7 According to an analysis conducted by Hill Strategies Research, based on a 2011 data request from the National Household Survey, the concentration of artists in New Brunswick represented only 0.43 percent of the total population of the province three years ago: this percentage translates to 1,700 artists who spent more time on their art than in any other occupation. Remarkably, this is the lowest percentage of the workforce per province appearing on the chart that accompanies the study (which, it should be noted, excludes Prince Edward Island and the individual territories because there are fewer than five hundred artists in those areas). British Columbia tops the chart with artists constituting 1.08 percent of its labour force; the median for Canada is 0.78 percent. At the time of the survey, the average income for an artist was $25,700 in New Brunswick—once again, the lowest among the provinces and territories surveyed. The study does not paint a rosy picture of the economic situation of Canadian artists, who earn on average 32 percent less than other workers composing the labour force in Canada. In New Brunswick, the situation is even more dire: artists earn 36 percent less than the average individual income at the national level. It would be useful to know how the average income of a New Brunswick family that includes an artist or is made up of two artists compares to the provincial and national poverty lines, but these levels are assessed based on the total income of a household and statistics are not available according to occupation. More detailed information on this topic is bound to be available in the near future, given that a task force on the status of the professional artist in New Brunswick was established under the previous government and met for the first time on 29 July 2014. Its clear mandate is to provide specific recommendations on measures or legislation that will improve the socioeconomic status of professional artists in the province.

8 The benefits that we derive individually and societally from the arts have been the subject of numerous studies that concentrate or touch upon a wide range of interests, including economic impact, cultural policies, standards for physical and psychological well-being, as well as educational objectives and goals (e.g., Bamford; Belfiore and Bennett; Etim-Ubah; Grodach; Towse). The arts play a unique role in the development, sustainment, and mobilization of both large and small communities. For example, it has been shown that the arts stimulate the economy, reinforce social cohesion, improve an individual’s health, inspire social engagement, and promote the image of a community. Nonetheless, when looking at a painting or photograph hanging on a wall in an art gallery that catches their attention, viewers likely do not think of these diverse benefits. To them, artworks may appear seductive, intriguing, illuminating, challenging, upsetting, or dehumanizing. Artworks are beautiful objects, metaphors for ideas or emotions, pieces of the puzzle in journeys of self-discovery, valuable remnants from a rich past and cultural tradition, or catalysts for creativity and innovation. Viewers connect with works of art on emotional, intellectual, and, at times, spiritual levels. Nonetheless, how does one quantify and analyze pleasure or other forms of aesthetic experience? How does one establish a clear causal link between investment in the arts and the values that it purportedly inspires in individuals (such as tolerance, intercultural awareness, and support for freedom of expression)? It is encouraging to learn from the data analyzed as part of the aforementioned project, “Building Public Engagement in the Arts,” that the majority of New Brunswickers state that the arts matter to them and to their communities. It is therefore time to shift the focus from investigating the significance and impact of arts and culture on individuals, communities, and economic sectors through costly surveys and extensive studies primarily conceived with socioeconomic impact in mind, to seeking ways of increasing support for individual artists and investment in creative projects that revitalize towns, cities, and rural localities. Even though there are some encouraging signs that we are moving in the direction of taking action, most notably through the re-examination of the status of the New Brunswick professional artist, we still subscribe to the practice of commissioning extensive studies that do not seem to lead to much concrete action.

9 Insufficient attention has been paid to date to the impact of the arts on small communities and even less consideration is given to the artists who live therein. From an airplane flying above New Brunswick at night, the province appears as a cluster of rural communities from which emerge its three largest urban centres—Fredericton, Moncton, and Saint John. The often-significant distance between these centres and the satellite communities that have formed around them, or between these artistic hubs and the more isolated northern part of the province, as well as the harsh and extended winter climate that marks the region, can have negative effects on individuals, which range from seasonal feelings of isolation or entrapment to disengagement from the community and mental illness. It is interesting to observe that Suzanne Dallaire does not consider herself at all isolated, although she spends long periods of time during the winter painting in her workshop: instead, she sees herself as part of a community that surpasses local and provincial borders. Beyond the potential effects of geographic remoteness and long winters, one of the most significant challenges faced by New Brunswick artists today is how to find new markets for their artworks. New technologies and social media undoubtedly play a significant part in connecting artists to the public, effacing barriers, and situating the individual within a global community. To establish links with the public and a potential clientele when she was launching her career as a painter, Dallaire adopted two parallel strategies: first, she created affordable products (small- scale reproductions of her paintings) that she sold at local farmers’ markets in spite of a stigma that surrounds such a milieu, which is perceived to be in binary opposition to the dignified settings of high art; and, second, she had the foresight to jump early on the information bandwagon by creating her own website, which immediately placed her creations at the fingertips of a global market. Holownia also seized upon the potential of placing his work on national and international stages by securing domains for his photography and printing press. Two of the galleries that represent Dallaire’s work are not located in New Brunswick: one is situated in Alberta and the other in Prince Edward Island; Holownia’s photography is exhibited by several galleries not located in New Brunswick. Interestingly, Dallaire does not lament being able to sell her paintings but the length of the creative process that produces each one of them. She is, however, unusual in so far as she is able to survive off her earnings as an artist. Without financial support from family members or grant programs, artists living in rural communities, where opportunities to supplement their income through part-time employment are likely more limited than in urban centres, face severe and at times insurmountable challenges. As Dallaire remarks in her interview reflecting on an observation made by Herménégilde Chiasson, embracing creative multidisciplinarity is in fact a solution to a harsh economic reality faced by artists attempting to make a living through their art practice.

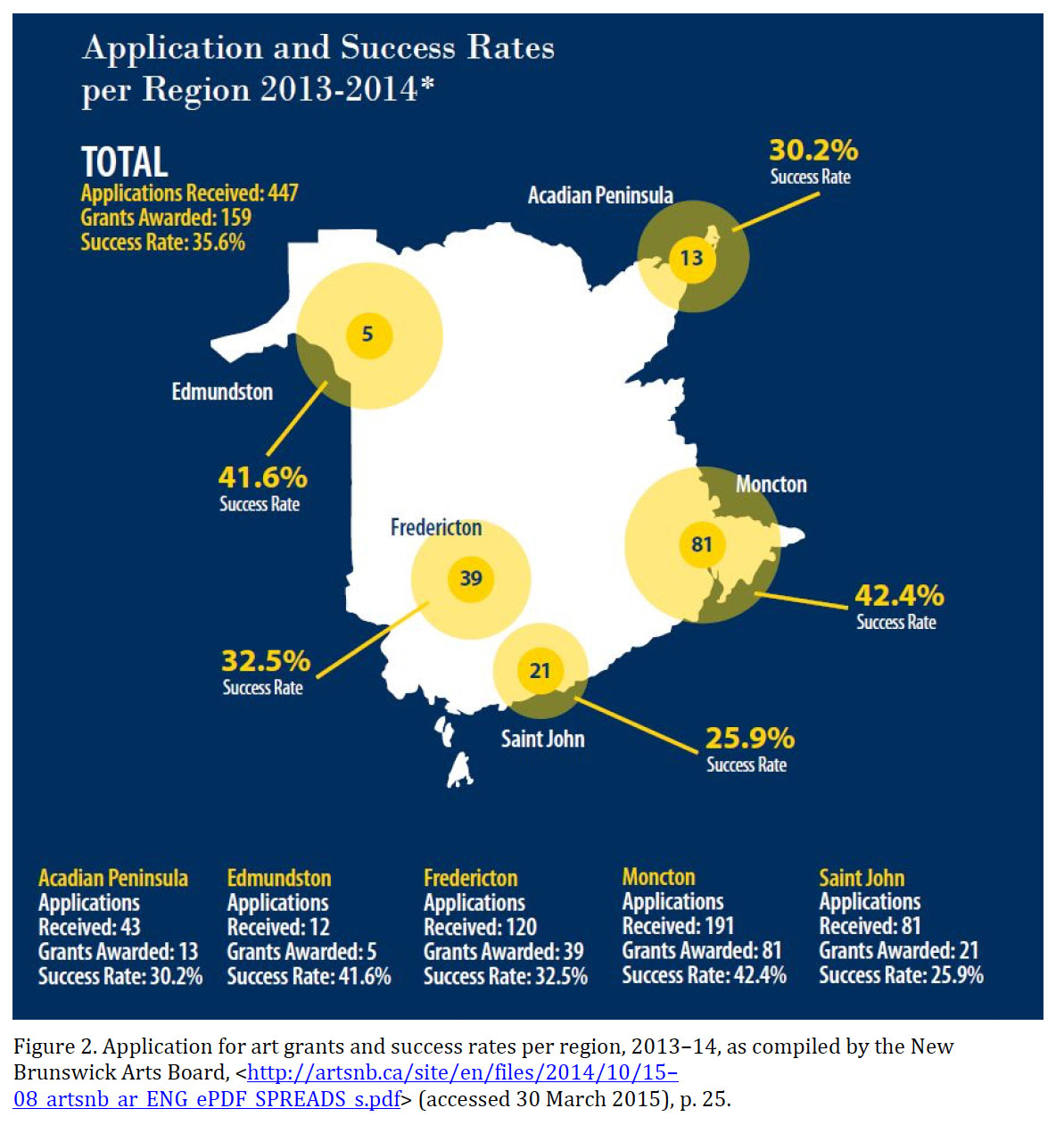

10 The 2013–14 Annual Report of the New Brunswick Arts Board indicates that 447 applications for funding were received during the period in question, of which the highest number—191—came from the Moncton region (Figure 2). From these 191 applications, 81 were deemed successful by a jury of professional artists, which constitutes a success rate of 42.4 percent. The second most important region, Fredericton and its environs, submitted 120 applications, of which 39 were chosen, which amounts to a success rate of 32.5 percent. Included in this classification are three other regions: Edmundston, Saint John, and the Acadian Peninsula. Of the 447 applications received, 159 received funding in the total amount of $650,000. The applications received in 2013–14 constitute the second highest number in the previous ten years, ranked below the 472 submitted in 2009–10, whereas the budget allocated to these grants is the second lowest after $648,080 in 2008–09; the highest yearly amount was $923,675 in 2009–10. This reduction in funding is worrisome and signs of improvement are not on the horizon.

11 The extraordinary achievement of the artistic community of Moncton and its surrounding area in the 2013–14 provincial competition is testament to its innovative vision and creative fervour. What distinguishes this region is its substantial Francophone component. Forming an important contingent of the larger New Brunswick community of performers and creators of art, Francophone artists grapple with the significance of a rich and complex heritage, but they have to look in the direction of the future. For some practitioners, the arts have become a means by which Acadian culture and traditions are publically showcased and transmitted to a new generation. In the Moncton region in particular, the arts contribute to the preservation of the collective memory, often inspire a dialogue about a checkered past, and foster a sense of pride within the Acadian community.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 212 The provincial government should be commended for continuing to support initiatives such as the New Brunswick Art Bank Acquisitions Program in spite of the monetary shortfall and economic challenges the province is facing. A provincial counterpart to the Canada Council Art Bank, the New Brunswick Art Bank is a permanent collection of the visual arts that was founded in 1968 to celebrate the contribution made by contemporary artists to the province. Through the acquisitions program of the art bank, contemporary visual art produced by artists from the province is acquired for display in provincial government offices and for loan to interested organizations. In the forty-seven years since its inception, the art bank has acquired more than eight hundred works of art from more than two hundred fifty artists from the province. The 2011 survey data compiled by Hill Strategies Research revealed that New Brunswick then had about 1,700 artists, and if we consider that number to be currently the same, only about 15 percent are represented in the collection—though it is a fact that between 1968 and 2015 the overall population of artists was significantly higher. Therefore, this small percentage undoubtedly needs to be increased in future years if we attach importance to the preservation of our artistic heritage.

13 The New Brunswick Art Bank actually predates its federal counterpart and is likely the first collection of its nature to be established in a Canadian province. By comparison, since its establishment forty-three years ago, the Canada Council Art Bank has acquired more than seventeen thousand paintings, prints, photographs, and sculptures that represent more than three thousand Canadian artists. Comparing the two collections is no simple matter, however, as the exercise needs to take into consideration a number of factors on which data are not easily gathered or accessible (e.g., the number of registered artists in each province, the yearly production per artist, the number of applications received by each program, etc.).

14 One can comparatively examine, nonetheless, the representation of Thaddeus Holownia’s work in these two collections. The searchable online database of the Canada Council Art Bank lists twenty- four photographs taken by the photographer, which were produced by him between 1975 and 1994; most of them are linked by their title to the exact places in the Atlantic provinces that they capture. The searchable online database of the New Brunswick Art Bank lists only four photographs by the same photographer, listed by title and purchase date: Mount Whatley, N.B. (1984), Dorchester, N.B. (1984), Tonge’s Island, N.B. (1984), and Rocklyn Bridge, Upper Dorchester, N.B. (1993). At a glance, this photographer’s work thus appears underrepresented in the provincial collection of visual art, when compared with the representation of his pictures in a national context. Suzanne Dallaire is part of the large number of artists whose work is not included at all in these two considerable art banks, despite her local popularity.

15 It is notable that the program does not favour established artists: those in the initial or intermediary stages of their professional careers are also encouraged to apply. The process of selection is juried and based on merit: every two years, a jury selects artwork to be purchased based on the acquisitions budget made available for the period in question. The program objectives are clearly outlined on the website of the Department of Tourism, Heritage, and Culture: to promote excellence through the acquisition of works of art; to develop a collection of contemporary works of art by living New Brunswick artists; to provide support and encouragement for New Brunswick visual artists living and working in this province; to make the collection accessible to the public and to public employees through its display in government buildings; and to make the collection accessible for educational purposes (Acquisitions Program n. pag.).

16 It is encouraging to learn that items from the collection can be loaned to interested and qualified institutions; recently, a travelling acquisitions exhibition rendered the collection accessible to a number of small communities across the Maritimes. For twelve months beginning in September 2014, the exhibit was mounted throughout New Brunswick (Florenceville-Bristol, Dieppe, Edmundston, Miramichi, Caraquet, Saint John, and Campellton), as well as in Nova Scotia (Pointe-de-l’Église). Coupled with complementary educational materials designed to assist educators, this travelling exhibit can have a great impact on targeted demographics, such as youth, seniors, families, aboriginal communities, persons living with disabilities, and mental health support groups.

17 When the provincial and federal art banks are compared at the level of the works contained in each collection and the number of artists represented, it becomes apparent that the holdings of the New Brunswick Art Bank should be increased. This is particularly important in light of the artistic wealth of New Brunswick and the voiced support by its citizens for the arts. It is hoped, therefore, that the provincial government will recognize the importance of this initiative and increase its funding. Another idea worth investigating is transforming it into a yearly competition.

18 Aside from individual practitioners and researchers, who advocates for the importance of arts and culture in New Brunswick? Established in 1990, the Association acadienne des artistes professionnel.le.s du Nouveau-Brunswick is an Acadian arts service organization for professional artists that aims at protecting and representing their rights as well as at promoting their contributions to society. One of its most recent contributions, A Global Strategy for the Integration of Arts and Culture into Acadian Society in New Brunswick, is an ambitious portrait of a vibrant artistic community and a vision for how the public can become involved in its sustainment and development. Founded in 2009, ArtsLink NB is an organization that seeks to advance and promote the value of the arts primarily in Anglophone New Brunswick. It recently undertook an important research project to examine the current arts and culture sector of the province, which was based on an extensive survey of artists and cultural organizations as well as statistical analyses of data not easily accessible but entirely reliable. Its key findings are disconcerting, as evidenced by the following:

19 Both organizations strongly advocate for investment in the cultural engine of the province, sensing perhaps that it is an attractive argument to the federal, provincial, and municipal sources of funding. They also emphasize that the arts are instrumental in the development of children and youth. For example, they improve a student’s self-confidence, build communication skills, increase intercultural awareness, as well as reinforce resourcefulness and problem-solving skills. Furthermore, these organizations argue that the arts have a great influence on the creative and innovative minds upon which the public and private sectors of New Brunswick will need to rely in order to compete successfully in the twenty-first century world and workplace. Educators and schools depend on pedagogical visits to public museums and on well-stocked libraries. A lack of systematic investment through the last decades in arts and culture infrastructure within the province is starting to take a toll on the public institutions charged with collecting and preserving artifacts and other objects of cultural and historical significance. The role of the museum as an institution of public value should be taken into consideration in the debate opposing fiscal responsibility and investment in the arts and culture, as the preservation of a layered and multifaceted heritage is at stake in New Brunswick.

20 In the case of the New Brunswick Museum currently occupying a site of historical significance on Douglas Avenue in Saint John, the pressing need to repair a structural failure in the roof, install fire suppression mechanisms, address artifact preservation standards such as climate control, provide adequate lab and conservation space, and increase public accessibility has left the fate of the institution up in the air. Built in the 1930s, the structure that houses the nucleus of Canada’s oldest continuing museum is owned and maintained by the province. In fact the New Brunswick Museum is an agency of the Department of Tourism, Heritage, and Culture (Figure 1). No doubt in an effort to address the issue constructively, however, the public statements released by the museum as well as interviews with members of its staff do not attribute any blame for the impending closure of the building, deemed unsafe by 2017, to the failure of the province to maintain and upgrade the structure occupied by this important institution. As documented by CBC news, recent public discussion concerning the future of the Collections and Research Centre of the New Brunswick Museum is focusing on a proposal to build a $40-million addition to the current building (“New Brunswick Museum”). A fund-raising firm has already been hired and a public consultation process has begun to examine the options available. One wonders if, when the design and planning of the addition are considered, cost effectiveness and functionality will trump architectural vision and green building principles. At the same time, the museum is facing another challenge: the lease of its Exhibition Centre, located within Market Square since 1996, is expiring. On the third floor at this location is located the world’s only permanent gallery of historical and contemporary New Brunswick fine art, which is complemented by exhibitions of historic Canadian and international artworks. The owner of the attached building, Fortis, has placed the shopping complex that forms part of the uptown pedway network up for sale. If such an important art institution is in this perilous and precarious state, taxpayers should be seriously concerned about the health and stability of the other museums, libraries, and heritage sites located throughout New Brunswick.

21 The interviews with Suzanne Dallaire and Thaddeus Holownia that accompany this special issue should be considered important points of access to the contemporary artistic communities of New Brunswick to which the artists belong. Both interviewees discuss candidly the benefits of working within the intimate settings provisioned by small communities and rural environments, but they do not shy away from expressing their preoccupations and struggles. Their straightforward answers to our questions remind us that support from public and private institutions is instrumental in sustaining the artistic communities of this region. Of primary concern to artists from this province is finding ways of transcending regional and national boundaries, of bridging the gap between the local and the global. Anchored in the landscape that surrounds them, their artwork is as much about the present as it is about the past and the future.

Interview avec Suzanne Dallaire

* Christina Ionescu a mené cette interview avec l’artiste à l’automne 2014 et, par la suite, y a apporté de légères modifications de forme sans conséquence sémantique.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7Interview with Thaddeus Holownia

* This interview was conducted in the winter of 2015 and edited for length by Lauren Beck.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13 Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14