Articles

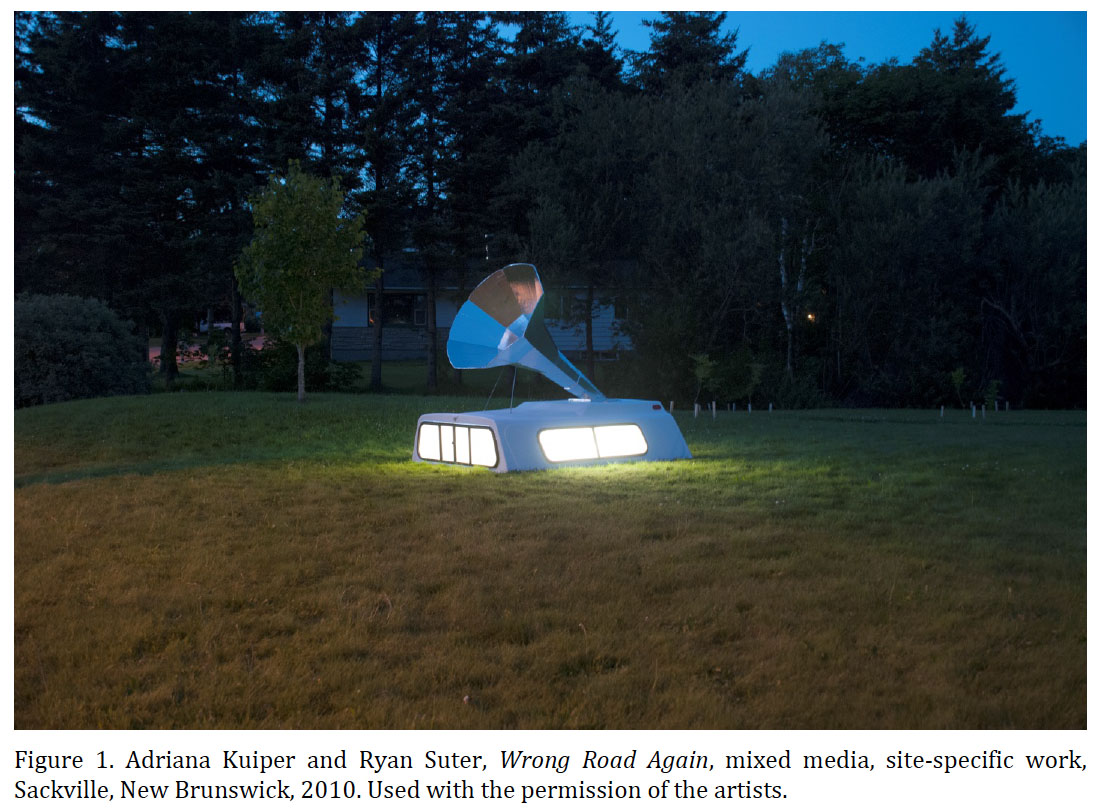

The Rural Readymade:

A New Brunswick Vernacular in the Work of Adriana Kuiper and Ryan Suter

Abstract

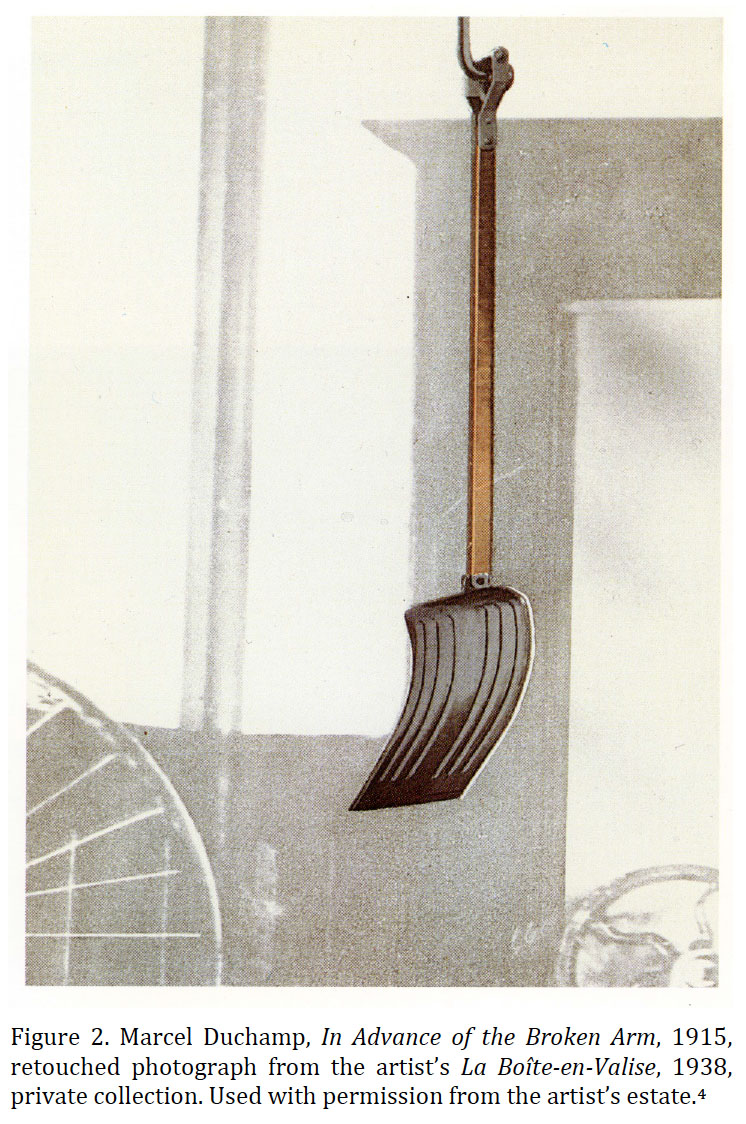

This essay examines the return to the readymade as a conceptual and sculptural practice in the work of contemporary artists Adriana Kuiper and Ryan Suter, who are based in New Brunswick. Marcel Duchamp’s famous work entitled In Advance of the Broken Arm serves as a departure point for discussing the significance of the readymade in contemporary art practice by specifically situating its reappearance within the creative practices of artists working in rural locations and responding to the local vernacular of found materials, DIY projects, roadside art, folk art, and the handmade. Issues concerning regionalism, the lure of the local, as well as notions of heterotopia and failure are explored as conceptual strategies in contemporary art practices. Included in this discussion are other Canadian artists (Clint Neufeld, Becka Viau, and Cal Lane), exhibitions (Rural Readymade; Oh, Canada in its Maritime venue; and Somewheres), and art festivals such as Nuit Blanche (Toronto), Nocturne (Halifax), and Art in the Open (Charlottetown).

Résumé

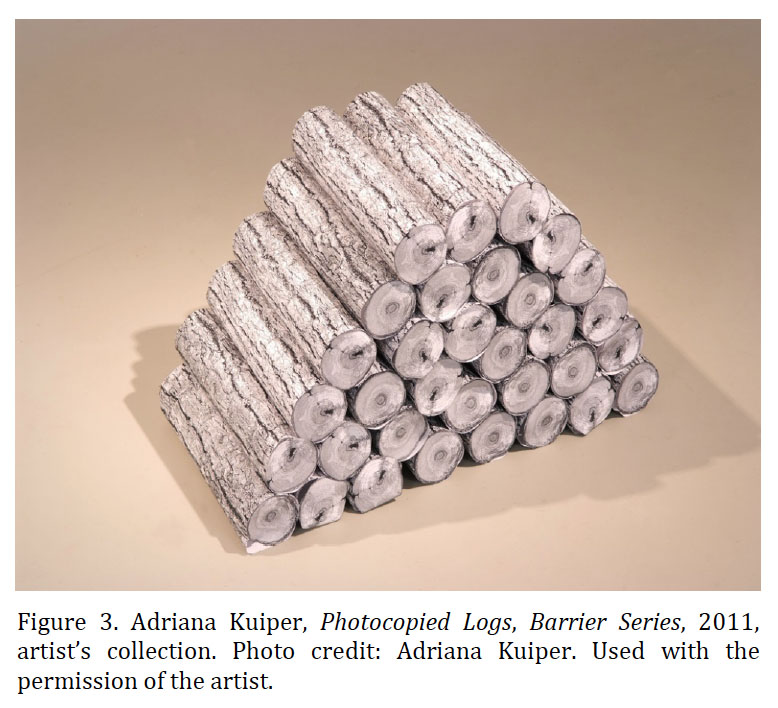

Cet essai porte sur le retour du ready-made comme pratique conceptuelle et sculpturale du travail des artistes contemporains Adriana Kuiper et Ryan Suter, qui vivent au Nouveau-Brunswick. L’oeuvre célèbre de Marcel Duchamp, intitulée In Advance of the Broken Arm, sert comme point de départ aux discussions sur la signification du ready-made comme pratique d’art contemporain en évoquant précisément sa réapparition au sein des pratiques créatives d’artistes qui travaillent dans des régions rurales et qui porte sur les matériaux vernaculaires locaux trouvés, les projets de bricolage, l’art routier, l’art populaire et les objets faits à la main. Des questions touchant le régionalisme, l’attrait pour ce qui est « local » ainsi que les notions d’hétérotopie et d’échec sont exploitées en tant que stratégies conceptuelles dans les pratiques d’art contemporain. D’autres artistes canadiens participent à la discussion (Clint Neufeld, Becka Viau et Cal Lane), aux exhibitions (Rural Readymade; Oh, Canada dans son emplacement des Maritimes et Somewheres) et aux festivals artistiques comme Nuit Blanche (Toronto), Nocturne (Halifax) et Art in the Open (Charlottetown).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1Goin’ back where I’ve already been

Even knowin’ where it will end

Here I go down that wrong road again

1 Picture a small town park at night. Sitting on the lawn (mowed religiously every week) is a truck cab, lit from within, with a loud speaker playing Crystal Gayle’s rendition of Wrong Road Again. The truck cab also emits bursts of sound from a local police scanner, which weave in and out of the heartfelt song. In its strange isolation, this work by New Brunswick–based artists Adriana Kuiper and Ryan Suter represents an emerging aesthetic in contemporary art known as the “rural readymade” (Figure 1). Their body of work is part of a recent trend by contemporary artists working in rural locations who are responding to the local vernacular of found materials, DIY projects, roadside art, folk art, and the handmade. By looking at the local, these artists honour what is often overlooked in our society, particularly as art is largely cultivated in urban centres. By referencing the rural, these artists are consciously re-rendering the readymade as an homage to a localized vernacular.

2 In this essay, I examine Marcel Duchamp’s concept of the readymade, its more recent use by regional artists, issues concerning regionalism and the lure of the local, along with notions of heterotopia and failure as conceptual strategies in contemporary art practice.

The Readymade

3 When the avant-garde artist Marcel Duchamp defined the readymade as “an ordinary object elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist” (Breton and Éluard, n. pag.), he was challenging the art establishment in a novel way.1 Emerging as early as 1913, readymades—many of which were manufactured objects such as snow shovels, bottle racks, bicycle wheels, and urinals— provoked and outraged the public. Duchamp was one of the first artists who insisted that he was “interested in ideas—not merely in visual products” (Duchamp 20).

4 When Duchamp came to North America in 1915 he encountered his first snow shovel at a New York hardware store and proceeded to make In Advance of the Broken Arm (Figure 2), signing the title directly onto the object prominently featured in the image (not seen in the copy provided). It was the first time Duchamp consciously applied the term “readymade” to his work, although technically he had been producing this art form since 1913.2 At a later date, Duchamp claimed in an interview: “I’m not sure that the concept of the readymade isn’t the most important single idea to come out of my work” (Kuh 92). This conceptual approach has greatly influenced twentieth-century art and continues to have a surprising residual effect today.3

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 25 One of the more perceptive writers on Duchamp’s influence on contemporary art is the American artist Mike Kelley who made the following claim about the readymade: “These objects are, without doubt, the most important sculptural production of the twentieth century” (“The Readymade” 80). Writing on their complexity as art objects, he pertinently observed:

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 36 This idea of taking “real objects” and representing them in a new context is essential when considering how contemporary artists are revisiting the notion of the readymade. In Kuiper’s Photocopied Logs (Figure 3), she plays on the doppelgänger or double, reconstructing the object from photocopied images of logs, thus replicating its real status within its own absurd, material self. In this way, the ubiquitous rural New Brunswick log pile becomes the subject replicated through its own materiality—paper made from wood pulp—generating a photocopied image of itself. This is an excellent example of how the rural readymade operates within contemporary culture.

The Rural Readymade

7 The expression “rural readymade” was first used in 1996 by artist and curator Cliff Eyland in the exhibition catalogue Rethinking the Rural in Contemporary Newfoundland Art, where he made the following statement: “The rural readymade plays with Duchampian precedent, but toward gentler, less ironic country ends” (9). Eyland had already used J. Russell Harper’s concept of the vernacular for an exhibition that he co-curated at the Dalhousie Art Gallery in Halifax, Nova Scotia. After having noted that “in speech, regional expressions are termed a vernacular,” Harper had concluded that “it seems equally appropriate to speak of the vernacular in connection with an art that expresses local ways of life” (qtd. in Eyland 9).6 In this sense, the vernacular can be read as the local, maritime tradition of “making do” with whatever is at hand, of improvising rather than purchasing something already made to suit the purpose. Despite this allure, this perspective is not far from what Ian McKay in The Quest of the Folk has described as “the trope of the romantic quest” (29), which outsiders (particularly as tourists), historically, and arguably to this day, impose as a cultural construction of the Maritimes. What McKay describes as a “folk formula” or “folk essentialism” (29)7 is seductive thinking where the local traditions are seen via an outsider’s perspective. Both Kuiper and Suter are well aware of the debate and continue to be sensitive to the problematic of “otherness” when discussing their sources of inspiration. Kuiper is particularly interested in how creative improvisation is part of everyday rural life. Geographical and cultural transplants “from away,” these artists moved to the Maritimes for employment. Kuiper teaches sculpture and drawing as an associate professor at Mount Allison University, and Suter is currently managing the Faucet Media Centre at the Struts Gallery in Sackville and teaches media studies part-time, at Mount Allison and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.

8 Kuiper, along with Halifax-based artist Eryn Foster, consciously applied Eyland’s concept of the “rural readymade” to her work. Subsequently, Shauna McCabe used the designation as the title of an exhibition she curated in 2011, which was held at the Confederation Centre of the Arts Gallery in Charlottetown. On the exhibition website and in related materials, McCabe described the concept of the show as follows:

Although McCabe qualifies “what is, and what is not, art,” she also employs a key strategy inherent to Duchamp’s readymades: even though these objects function as a form of anti-art, their removal from their original context in conjunction with their placement within the art world significantly shifts their meaning and displaces the gallery setting. For the Charlottetown exhibition, Kuiper and Suter remade Wrong Road Again, but the work, now situated in a gallery setting, retained something of its site-specific intentionality through its live-feed police scanner, literally picking up the local vernacular.9 Although I am discussing this work within the construct of the readymade, it should be noted that Duchamp repeatedly altered his manufactured objects and developed a hybrid form of the readymade, classifying it as “rectified readymade.”10 I argue that this hybridity is exactly what makes the artwork produced by Kuiper and Suter so interesting and so connected to the creations of other artists such as Kim Adams, which play on the use of sourced materials from the everyday.

9 Through the re-installation of Wrong Road Again in The Rural Readymade exhibition, Kuiper’s interest in hidden architectural structures, already evident in her previous work, is extended. As collaborators, Kuiper and Suter combine their shared interests—Kuiper in the more sculptural aspects of production and Suter in the more technical ones. Working collaboratively in site-specific locales, they are interested in the shift between inside and outside, as they clearly stated when I recently interviewed them: “Both of us are interested in how sculpture works in outdoor public locations.” In Wrong Road Again, they mix a found truck cap (often used for other constructions such as improvised chicken coops) with country music to create a piece that suggests a narrative reading. Whether the work is sitting on the floor of a gallery or in a Sackville park, it lights up and plays music as the viewer approaches it, suggesting a life within. As Miwon Kwon has pointed out, site-specific work often “demand[s] the physical presence of the viewer for the work’s completion” (86); and, in a similar way, Duchamp argued that the viewer is a key component of any work of art. As viewers approaching Wrong Road Again when the interior lights up and the song is triggered, we suddenly feel intrusive, somehow complicit as voyeurs of this improvised home. We hear the live feed of police surveillance with its rudimentary neighbourhood watchfulness imposed upon us, layered over Crystal Gayle’s lilting lyrics.

10 Although the Rural Readymade exhibition lacked a catalogue essay, its press release and didactic panel by McCabe provided a multifaceted context for the works exhibited:

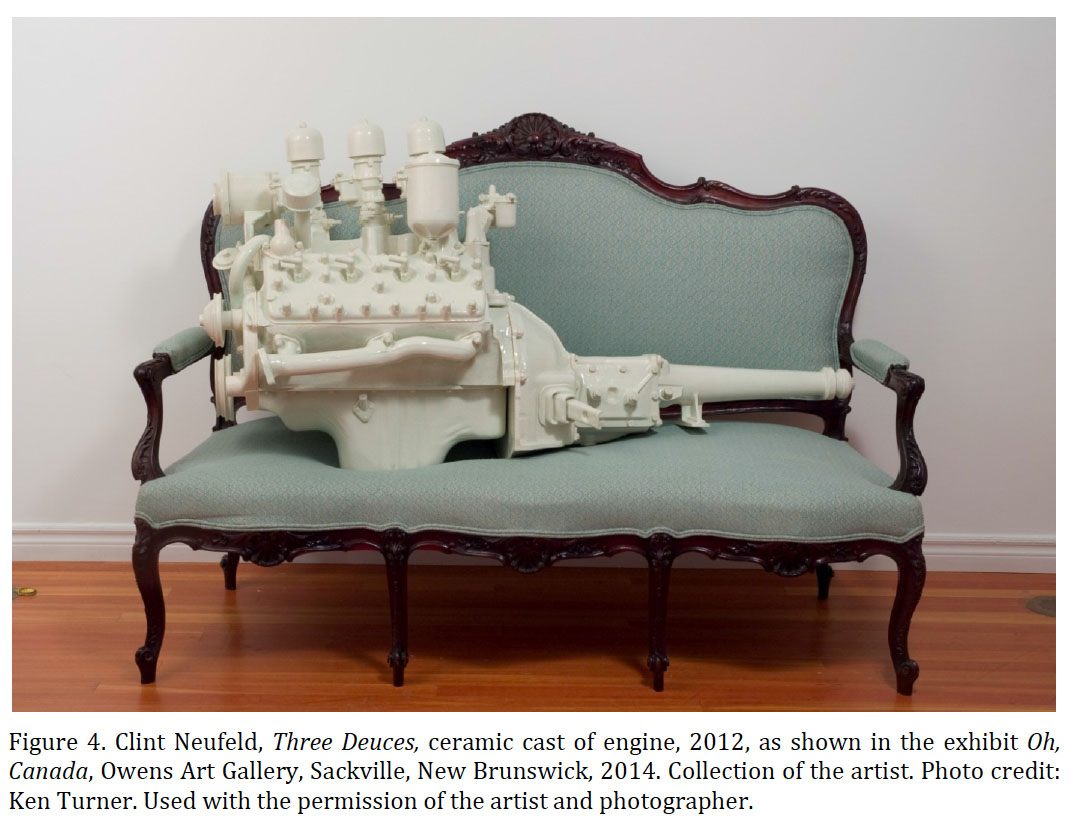

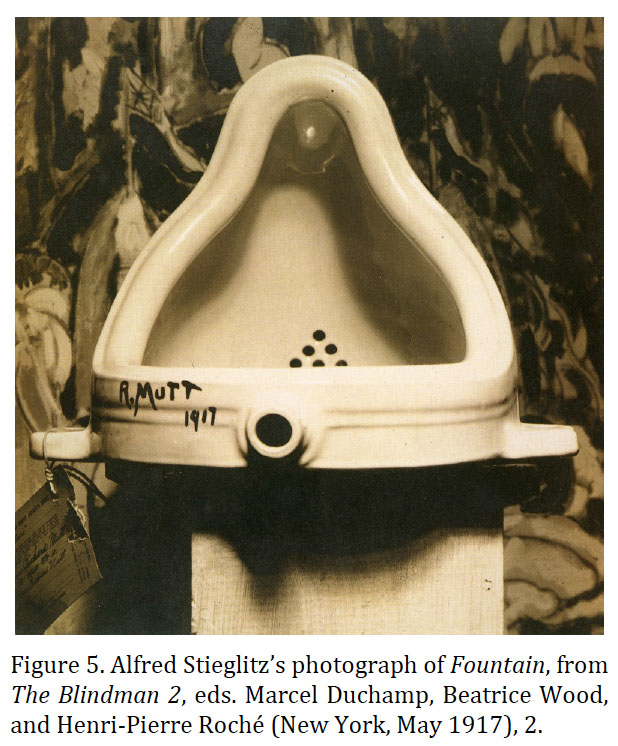

One of the artists included in the Rural Readymade exhibition was Saskatchewan-based Clint Neufeld, whose ceramic engines help to define this emerging aesthetic. Neufeld’s work was also featured in the Oh, Canada exhibition that recently toured the Maritimes and travelled to Calgary in 2015 (Figure 4).11 Neufeld experiments with concepts of masculine identity, often in the form of ceramic transformations of engines and transmissions. The hyper-masculine prototype of the engine is something that also fascinated Duchamp’s fellow Dada artist Francis Picabia who included it in his mechanistic drawings and paintings.12 What is unique about Neufeld’s work is how he has combined the interests of both artists yet maintained something unique to his own experience of growing up in rural Saskatchewan. I see Neufeld’s engines as exquisitely cast replicas that use the same conceptual language as Duchamp’s Fountain, a readymade consisting of a mass-produced porcelain urinal signed and placed in a gallery in 1917 (Figure 5).13

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

Interestingly, Neufeld began his casting of everyday objects while completing his MFA at Concordia University in Montreal. In a Duchamp-like gesture, he took his favourite Estwing framing hammer and cast it in porcelain. According to Neufeld, “These hammers were a real turning point for [him]” (155) and changed how he conceptualized his art practice.

11 From a conceptual perspective, Neufeld’s work is about the rural readymade fitting into larger concerns about regionalism, an aspect also explored by curator Denise Markonish in the Oh, Canada exhibition. This show opened at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (North Adams, Massachusetts) in 2012 and featured one hundred works from more than sixty artists, many emerging and positioned regionally within the catalogue. In the address delivered at the exhibit opening in the Maritimes, the New Brunswick writer and critic Mike Landry commented on the importance of regionalism:

Continuing this theme, Landry added: “And maybe this is why Sackville shines as it does within contemporary art in Canada. It is a place whose regionalism is felt at first glance of the Tantramar, and yet is engaged in thought and concerns beyond its borders.” Landry’s implicit argument that Markonish has put regionalism into practice is something that connects back to the theme of the rural readymade. Markonish organized the catalogue by region, dividing its content into sections that break down into provinces and territories.14

Regionalism and the Lure of the Local

in the modern race for progress, evoke both nostalgia and fascination.

12 Rob Shields in his pivotal study Places on the Margin addresses some of the same concerns about regionalism as Landry. These out-of-the-way places are geographically on the social periphery in the typology of cultural systems of space, in which places are ranked in relation to their cultural importance.16 For example, in Canada, Toronto is often seen as the cultural capital of the arts, while in the United States, New York plays that role. By positioning Sackville as a marginal place, the star of which is rising within the cultural field, Landry alluringly posed a pertinent question: “But what is it about this place and its swamp magic?” he asked while referring to the arts community within Sackville. In answer, Landry cited Mount Allison University as a locus for education and culture, the Owens Art Gallery as evolving into one of the key university galleries in Canada, as well as the artist-run gallery Struts and the Faucet Media Art Centre as facilitating a dialogue on the arts within the community.17

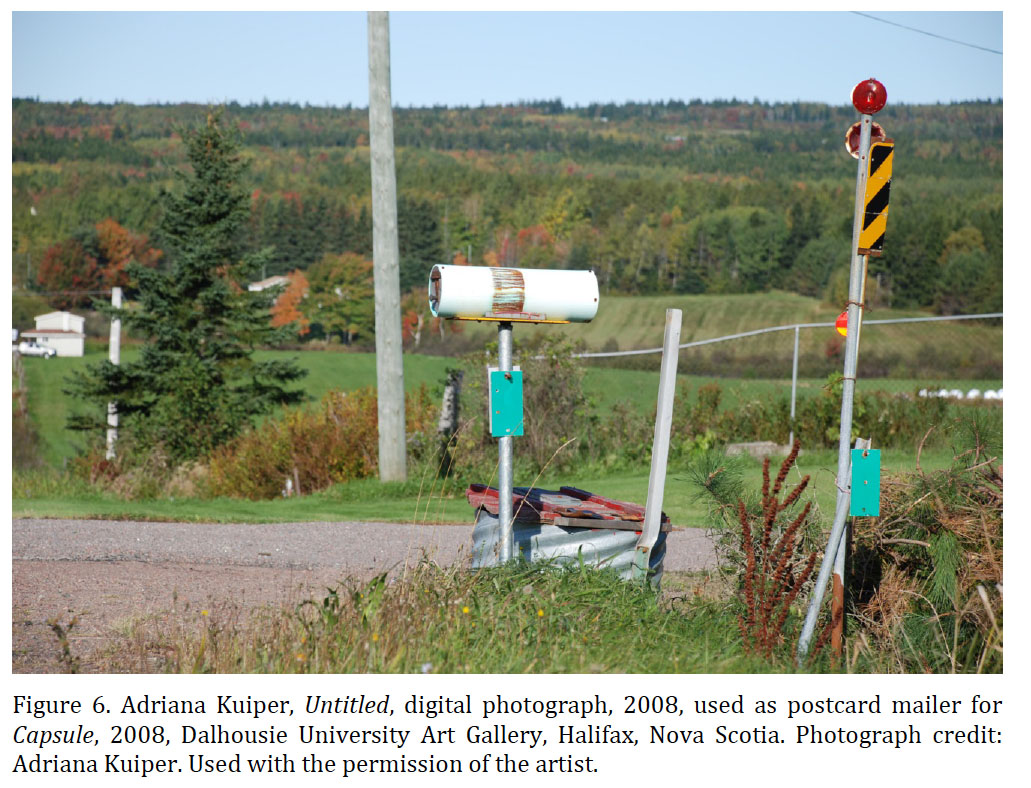

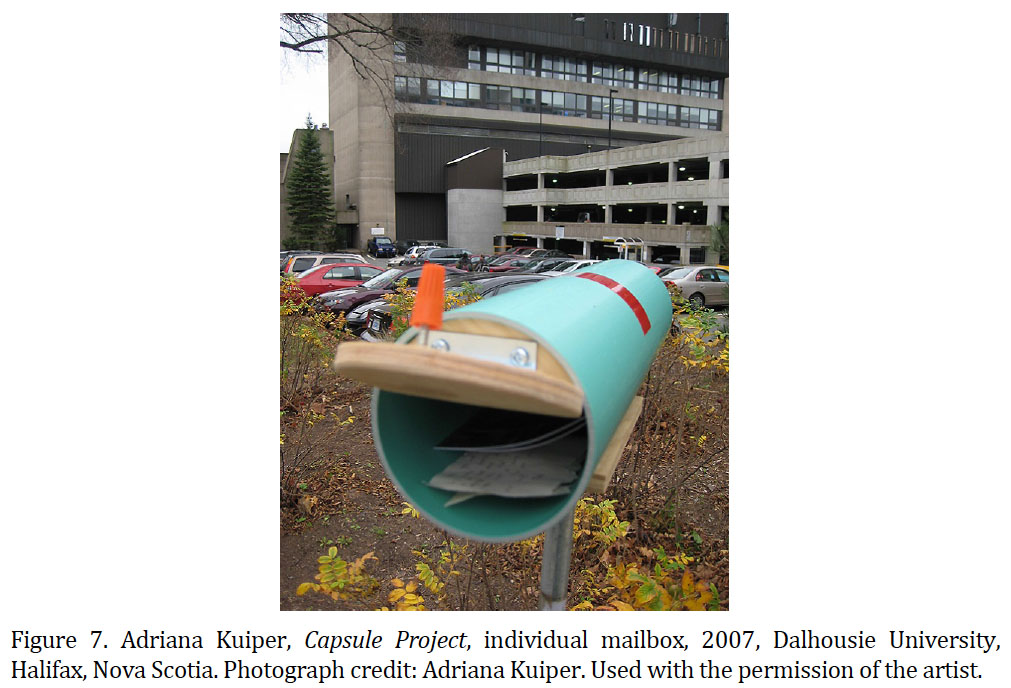

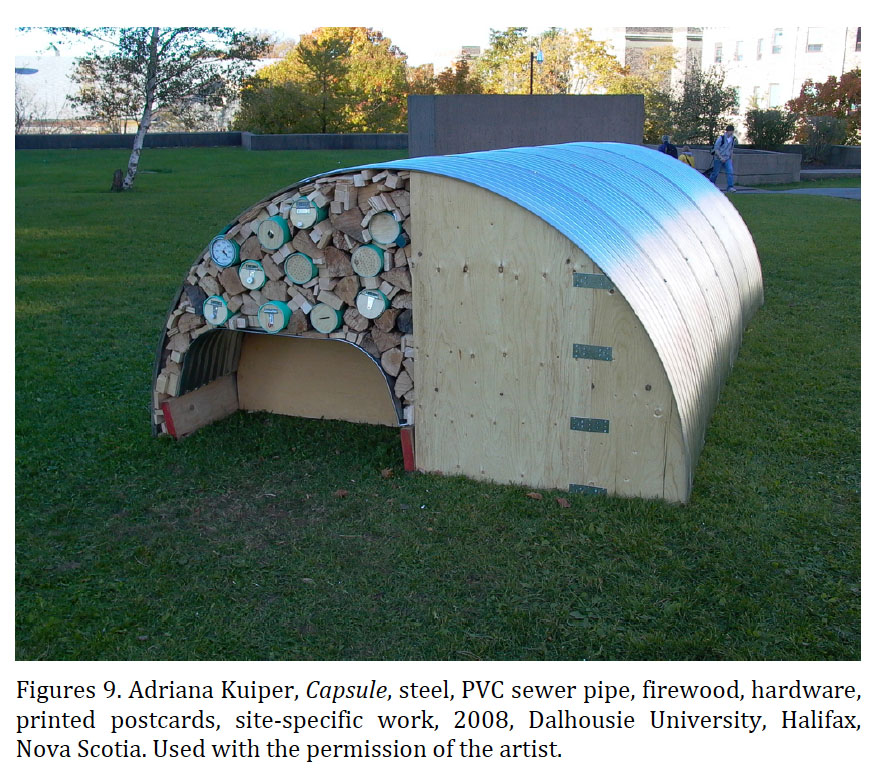

13 The art critic Lucy Lippard has also addressed the subject of regionalism in The Lure of the Local, where she reflected on this fascinating notion as follows: “The lure of the local is the pull of place that operates on each of us, exposing our politics and our spiritual legacies.” (7) She adds that “inherent in the local is the concept of place—a portion of land/town/cityscape seen from the inside, the resonance of a specific location that is known and familiar.” (7) Both Kuiper and Suter explore the Tantramar region from an insider’s perspective, yet as transplants to Sackville they maintain an outsider’s objectivity and bring their knowledge of the contemporary art scene to bear on their work. Their living situation and creative outlook is not unusual, as Lippard reflects: “Most artists today come from a lot of places. Some are confused by this situation and turn to the international. Some of the best regional art is made by transients who bring fresh eyes to the place where they have landed” (7). Nowhere is this more evident than in Kuiper and Suter’s practice of carefully observing innovative objects in rural neighbourhoods. Kuiper’s colour photograph of an improvised mailbox (Figure 6) serves as research material for her own practice. Using cheap PVC tubing, its creator has rigged up a weatherproof mailbox that serves his or her purpose much better than a store-bought model. Kuiper adapts this design as a prototype for her public installation Capsules, displayed at Dalhousie University in Halifax (Figure 7). Interestingly, the source photograph served as a postcard that was used as a mailer for the show.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

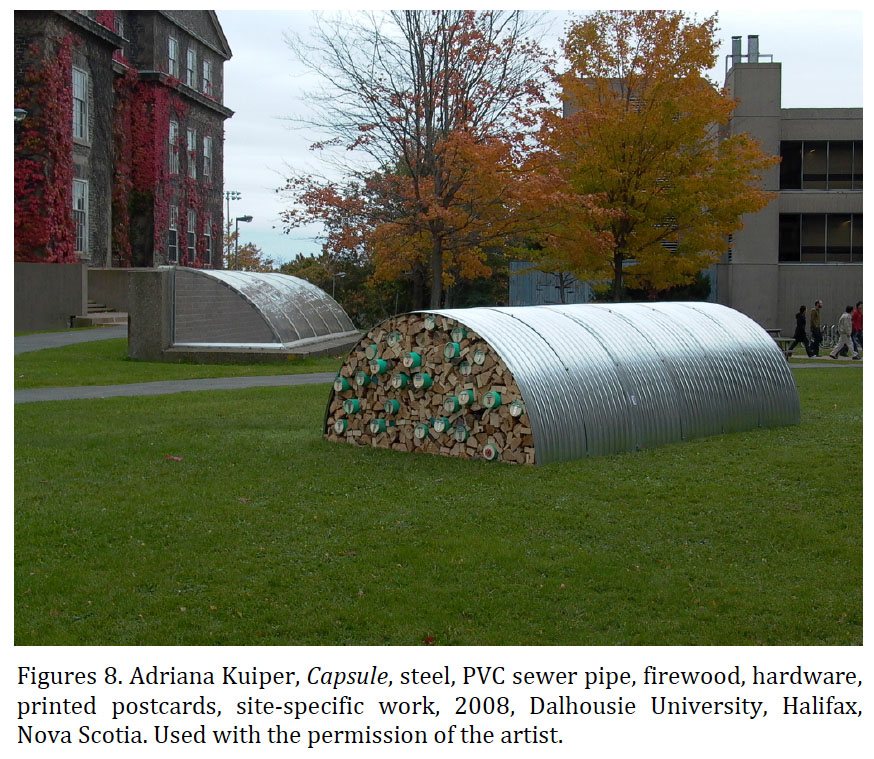

Display large image of Figure 714 Capsule consists of a steel culvert shelter reminiscent of rural Quonset huts. Forming an impenetrable wall at each end, wood stacks were interspersed with improvised “mailboxes” designed after the rural prototype. These tube-like mailboxes were interactive and could be opened to leave or receive messages. Mailboxes were also located around the campus as satellite components of this piece. Viewers were encouraged to correspond using printed postcards left in the mailboxes. Conceptually, Kuiper’s piece complies with the notion of the rural readymade, appropriating the rural object—the improvised mailbox—and repositioning it in a new context. Notably, her mailbox is rendered more aesthetically pleasing (despite Duchamp’s anti-aesthetic mandate, many of his works have been appreciated likewise), by using the hint of turquoise in the road markers (see Figure 6) and implementing the colour structurally into the PVC tubing. Arguably embodying a DIY aesthetic, Kuiper’s work shares this visual component with the creative output of Kim Adams, a contemporary Canadian artist whom she much admires. Both Kuiper and Adams look to hardware stores, especially Canadian Tire, as a site for sourcing DIY materials that inspire their work. Like Adams, Kuiper produces work that carries a sense of displacement. In particular, the relational component of the mailboxes strategically suggests an oddness within the urban setting, as they are seemingly more at home within their rural context. Yet, the fact that they function as relational art objects that allow the public to interact through postcards is a play on that purposeful lack of exchange often found in urban centres.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 915 Kuiper has long been interested in the architectural and sculptural possibilities of shelters as alternative spaces, particularly in times of potential threat. Raised on the Prairies, she was long familiar with the reality of the tornado shelter and, as a child, her preferred play space was under the staircase of her home. She has extensively researched and made prototypes of this type of subterranean shelter in her previous work—Flowerbed (Tornado Shelter) of 2005 and in her installation Metropolis (Five Tornado Shelters) for Nuit Blanche in 2007. Even Wrong Road Again suggests a potential life underground. A substantial part of her body of work is influenced by growing up in the 1980s consciousness of nuclear catastrophe. As a post-9/11 practising artist, she has a heightened awareness of this culture of fear. Kuiper has since developed a body of work during this period that is marked by Orange Alert codings and duct-taped solutions to the war on terror. As part of her Barrier Series, she subverts the futility of these improvised solutions and their fear-mongering tendencies.18 These subterranean shelters suggest “the irrationality of depths” of Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space (18). In Bachelard’s view, “The cellar then becomes buried madness, walled-in tragedy” (20).

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1016 These weird constructed spaces, the purpose of which is to represent neither home nor actual shelter, bring to mind Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopias, as explored by the French philosopher in his 1984 essay entitled “Of Other Spaces.” A heterotopia is a place that neither quite lives up to being a utopia, nor is it a dystopia: it is positioned instead as an in-between space where things seem different or strange. Foucault’s notion of heterotopia refers to “something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted” (n. pag.). Sites such as retirement homes, psychiatric hospitals, and prisons are modern heterotopias of deviation. To Foucault, even gardens, cemeteries, museums, and libraries qualify as heterotopias of urban centres. He singles out their particularity as follows:

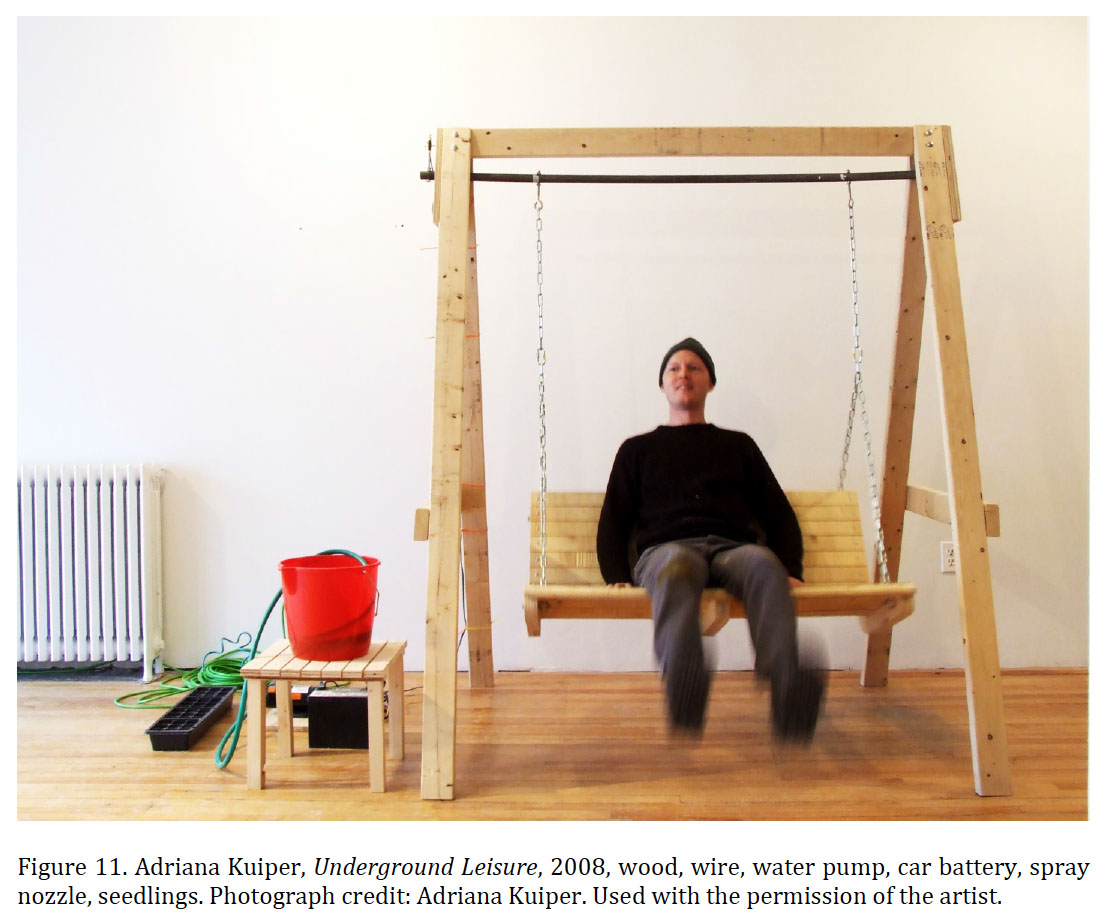

17 One such local space that could be categorized as a heterotopia is the now-defunct military bunker at Debert in Nova Scotia. Commonly known as the “Debert Diefenbunker,” this underground structure decommissioned during the Cold War served as a counter-site for a group of artists organized by Mitchell Wiebe to exhibit their work in May of 2011. Art critic Lizzy Hill describes the art as “playful critique of militarism and exploring the theme of survivalism” (n. pag.).19 Produced for this group exhibition, Kuiper’s Underground Leisure (Figure 11) is essentially a porch swing made with found materials where the interactive swinging motion activates a riding lawn mower battery that pumps misting water onto plants. The porch swing, suggestive of an earlier small town era, is adapted to this site and provides a slightly absurd function within the “buried madness,” to quote Bachelard again, of this labyrinth-like space.

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 1118 During a 2012 residency at the Klondike Institute of Art and Culture, Kuiper and Suter collaborated to develop a site-specific work entitled Burned (Figures 12 and 13), which was shown the following year in The Natural and the Manufactured exhibition in Dawson City, Yukon. The title and its subject are a word play on the tragic fire that destroyed the Sackville Enterprise Fawcett Foundry in January of that same year. Not only was this historical building burned to the ground, but a number of artists’ studios were also in ruin, including Kuiper and Suter’s shared space. Burned employs the burn barrel, a vernacular readymade, often used to burn trash or for provisional heat. Its materiality was particularly relevant to the original site of the foundry, as an enduring strike/lockout had once affected this local business and the burn barrel came to be a characteristic feature of this disputed site.

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 1319 The artists also discovered in their research at Dawson City that during the Gold Rush prospectors often used bonfires to thaw the permafrost in order to mine the gold dust frozen in the soil. Kuiper and Suter incorporated these ideas and history into their piece by using a bright red burn barrel (a reference to the bucket brigades that used to put out fires in the early years of Dawson City), which showcased replica logs formed of ice from recycled water. As these icy logs melted, the drips were amplified through a speaker that alerted others to its inherent failure as a functional object, which was one of Duchamp’s main objectives for the readymade.20

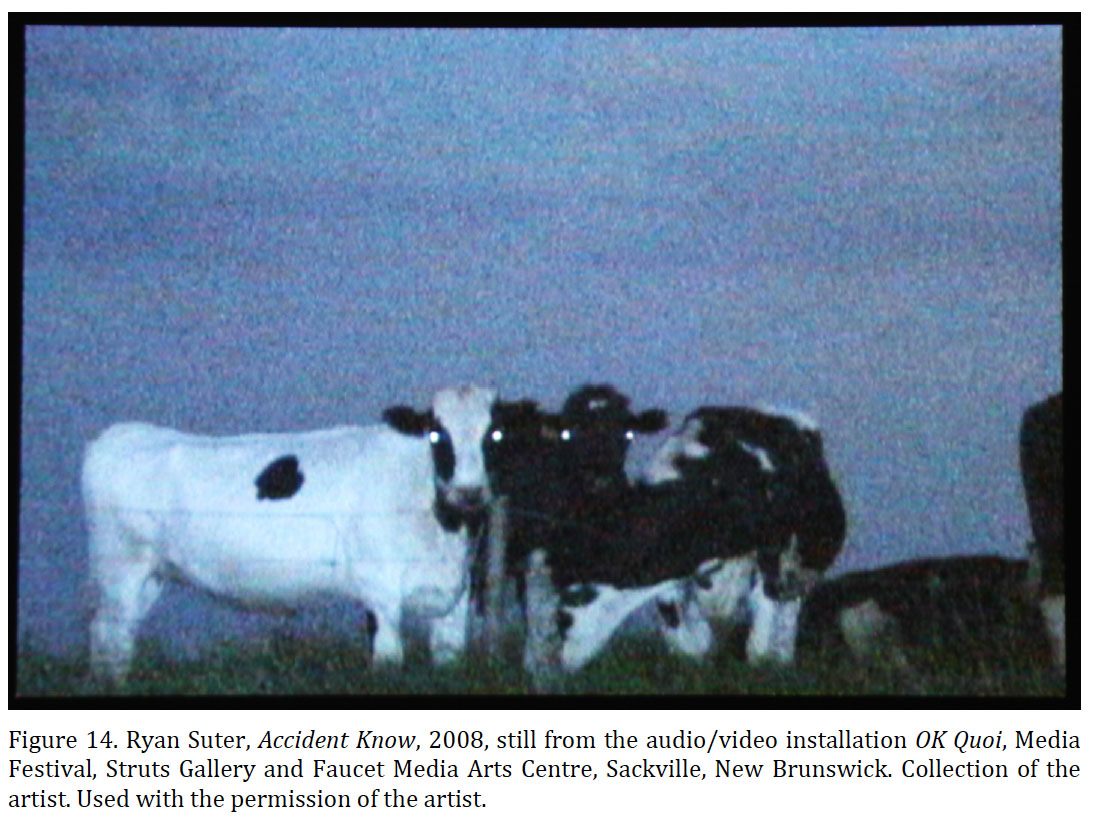

20 In Sackville, Kuiper and Suter continue to find endless source material for their practices. Suter often walks through the lanes and fields at night to record what he refers to as the oddity of the place. His earlier audio/video installation Accident Know (Figure 14) is one such work that records a rural setting at night. In Suter’s media work, there is a recurrent concern with what he describes as “the space between things seen and things heard” (n. pag.). In this video-still, we are struck by the irrationality of night caught in the eerie spectral gaze of the cows. There is something of the postmodern animal represented here through the visual lens of contemporary art.21

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 1421 These eerie effects of night are further explored by Kuiper and Suter in their recent collaboration Night Tweeter (Figure 15), a mobile sculpture that can be transported to various locations by bike. The sculpture/bike trailer includes a lid that opens and converts to a large speaker, as well as a white tent that folds out of the trailer. Recalling Wrong Road Again, the interior of the tent is illuminated, thus attracting insects to its interior. Not only does it become a provisional home for bugs, but it also allows for an interactive component where the insects’ erratic movement is tracked by a computer that translates it into sound. The resulting “insect music” sounds like a discordant theremin, thus generating further sci-fi associations. Exhibited as part of the Charlottetown festival Art in the Open, Kuiper and Suter’s Night Tweeter doubled as an improvised campground. Similar to Wrong Road Again, it is lit from within, but viewers cannot enter and are therefore unsure of what they are actually seeing. It appears as a hybrid camper and a nocturnal spectre. Suter explains that the work shares an affinity with Steven Spielberg’s film Close Encounters of a Third Kind (1977), in which communication with extra- terrestrials was the combined effect of musical notes with flashing coloured lights. In an interview, Suter observed that “this form of communication seems pre-lingual” and exploring further this idea was intriguing in his view (Young).

Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 1522 The artists have since adapted this mobile artwork to another site in Halifax—the historic Citadel—for the 2014 Nocturne festival. Rather than rely on interspecies communication, they use the site to flash Morse code into the night. This long-defunct fortress, now a museum, falls into the category of a heterotopia, as it is centrally located in the city but still functions as a kind of no-place. Suter explained the connection between the installation and the piece as follows: “We’re playing with the Citadel as a signalling station. We’ve always been fascinated by the Citadel as a space in the city. It’s in the centre of town but definitely peripheral in how it functions” (Young). By relocating Night Tweeter from one site to another, the artists have transformed the work into a nomadic art object, “unhinged” and taking on new meanings according to its different locations.22 Like a mobile phone, tweeting as a form of exchange of information links the new means of communication with more outdated modes of technology, such as the Morse code. Kwon comments on how these relational shifts in contemporary art have redirected our thinking about site specificity:

The Rural Readymade and Beyond

23 I would like to reflect upon the wider implications and applications of the rural readymade within Canada. The rich modality of contemporary art creates a complex relationship with its viewers, whether they are located in urban centres like Montreal and Toronto or in rural places such as Sackville. In a recent exhibition of emerging artists from the Maritimes, curator Pan Wendt wrote of how regional dialects affect our understanding of place. His chosen title for the exhibit, Somewheres, explicitly engages with this issue: “It marks a place even as it denotes and even multiplies uncertainty about location. Even if that place cannot immediately be identified, one knows that it is not the place, or the centre, that sets the standard” (2). Therefore, being on the periphery or margin can often serve as an advantage. Wendt’s curation of Somewheres includes an installation by Becka Viau called Monument (Figure 16). As a site-specific work it literally becomes “unhinged” in its relocation from the farm to the gallery. Monument relates to Viau’s ongoing interest as both an artist and a resident of Prince Edward Island in rural farming practices. Here, she positions eight round bales of hay at the entrance to the Confederation Centre Art Gallery. Removed from the normality of the field, these hay bales become sculpturally fascinating within the urban setting of Charlottetown. As a rural readymade, they shift our thinking about what art, in fact, can be. Of Monument, Wendt writes:

According to Viau, “As an object Monument stands in stark contrast with the surrounding architecture and the steadfast mandate of the Confederation Centre—it exhibits a sense of place whose meaning shifts with the passing of time” (n. pag.). This complexity of meaning is echoed by Lippard who makes the following interesting claim: “Place is latitudinal and longitudinal within the map of a person’s life. It is temporal and spatial, personal and political. A layered location replete with human histories and memories, place ha[s] width as well as depth” (7).

Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 1624 In Wendt’s curatorial essay for Somewheres, he poses an incisive question: “Could being regional or remote also be a strength?” (3). What if this position, of being removed from the established cultural centres, actually cultivates a subversive mode of producing and thinking about contemporary art practice? Wendt expands his argument as follows:

I think that Wendt has touched on something significant and profound. When looking at the work of Kuiper and Suter in conjunction with the notion of heterotopia as something of a failed utopia, it can be seen as yet another rupture in the ideology of modernism as a progressive lineage. If failure becomes a marker for change in contemporary art, then the inherent play of the readymade, from Duchamp onwards, surely extends this phenomenon into a wider and more layered discussion.23

25 In exploring this concept of the rural readymade, I would like to come full circle to Duchamp’s In Advance of the Broken Arm of 1915 and conclude with the work of Cal Lane, another Canadian artist included in the group show at the Debert Bunker discussed previously. If failure has become a new marker for the avant-garde, then Lane’s 5 Shovels piece, which consists of five plasma-cut, found shovels, epitomizes this trend (Figure 17). In this case, functionality is made obsolete and the shovels, as rural readymades, support all but Duchamp’s anti-aesthetic stance. In their ornamental beauty, these shovels are examples of an aesthetic that begins to generate new ways of thinking about art. Reflecting on the concept of failure as a criterion for determining the avant-garde, does the rural readymade, in its relocation from the centre to the periphery, make us think anew about our relation with the everyday? With an increasing environmental consciousness that advances the local rather than the international, is there not something to be said for a regional art that proves more resilient than the promise of globalism? These questions only begin to address this ongoing debate by opening up the notion of the rural readymade as one critical response to these shifting, uncertain times.

Display large image of Figure 17

Display large image of Figure 17