Abstract

This research presents findings from a case study that involved an entire class of Anglophone 7th grade students in New Brunswick. It expands upon the scholarly work of Canadians and Their Pasts as well as current research surrounding historical consciousness in Canada. The data provides a rare micro glimpse into the ways in which Anglophone youth in New Brunswick are currently engaging with the past. It also reveals some of the collective memory narratives students employ when remembering New Brunswick’s (as well as Canada’s) past. The findings present several points for consideration by both educators and public historians in this province.

Résumé

Cette recherche présente les résultats d’une étude de cas à laquelle a participé une classe entière d’élèves anglophones de la 7e année du Nouveau-Brunswick. Elle se fonde sur les travaux universitaires de Canadians and Their Pasts ainsi que sur la recherche actuelle portant sur la conscience historique au Canada. Les données donnent un petit aperçu rare sur les façons dont les jeunes anglophones du Nouveau-Brunswick s’intéressent actuellement à l’histoire. De plus, la recherche révèle certains récits de la mémoire collective qu’évoquent les élèves lorsqu’ils se souviennent de l’histoire du Nouveau- Brunswick (ainsi que celle du Canada). Les résultats montrent plusieurs points à considérer par les enseignants et les historiens publics de la province.

Reflecting upon the past is a learned skill, and many Canadians are adept at it. Others have only an unconscious sense of the role that history plays in defining their identity and agency. Canadians weave fabrics of meaning from a warp of personal, deeply felt, highly connected memories and a woof of critical, distant, disconnected histories.

– Conrad et al., Canadians 10

Introduction

1 The landscape of history education is rapidly changing across North America. Since 2010, the United States has adopted Common Core State Standards for English/Language Arts in History/Social Studies, which have shifted the focus away from teaching the what of history toward learning the how of critical inquiry (Wineburg, Martin, and Monte-Sano x). Likewise, in Canada, the Historical Thinking Project has established equally sophisticated goals for history education in this country that are based upon the epistemology of historical inquiry. Through historical thinking, it is argued, students can be transitioned from “depending on easily available, commonsense notions of the past to using the culture’s most powerful intellectual tools for understanding history” (Seixas and Morton 3).

2 Fuelling such reform in history education is a forerunner that questions whether history is actually relevant to contemporary society. Certainly, in Canada, the recently released findings of Canadians and Their Pasts affirm a direct link between past and present among adult respondents. These revelations have led the authors to set aside any doubts of relevancy, and to confidently confirm that for most adult Canadians “the past is not past. History—as people’s knowledge, as medium of public conversation, as academic pursuit—lives” (Conrad et al., Canadians 160). Such confirmations, however, raise another set of questions: What about young Canadians? Do they possess a strong sense of the past? Where do they place their trust in history resources? What narratives have they adopted for remembering? These are the discussions that frame this particular inquiry.

3 Thus, in the interest of building and expanding upon the existing body of research, this research note presents findings from a case study that involved an entire class of 7th grade New Brunswick students. It provides a rare micro glimpse into the ways in which Anglophone youth in this province are currently engaging with various pasts (be that family, province, nation, or region). It also reveals some of the collective memory narratives 7th grade students employ when remembering their provincial, as well as national, pasts.

What Is Historical Consciousness?

4 Historical consciousness constitutes a relatively recent topic of interest within history education. As both Jean-Pierre Charland and Christian Laville have noted, the term was introduced by Hans-Georg Gadamer with the publication of his 1963 theoretical treatise, Le problem de la conscience historique. Later, in the 1970s, the concept was adapted by German didacticians Karl-Ernst Jeismann and Jörn Rüsen to epitomize a “new historicist” turn away from the simple transmission of historical “truths” in education (Körber 148). With this turn, rote learning was replaced by a renewed interest in teaching “the specific and peculiar nature of historical thinking and explanation” (Rüsen 281), with the objective of enabling students to construct more relevant meaning about the past (Körber 148). As part of this reform movement, Bodo von Borries and Mange Angvik initiated a series of elaborate investigations into the historical consciousness of 9th grade students (as well as their teachers), across twenty-seven countries in Europe.2 This inquiry was limited to students aged 15–16 years; however, von Borries also undertook a smaller investigation in 1992, involving 6,500 German students across the 6th, 9th, and 12th grades (von Borries 246).

5 Mapping the Historical Consciousness of Canadians

6 In Canada, the genealogical tree of historical consciousness can also be traced back to Jeismann, Rüsen, Angvik, and von Borries. In particular, the theoretical framework that Jörn Rüsen popularized has greatly influenced empirical research in this country. For example, Jean-Pierre Charland, Christian Laville, Jocelyn Létourneau,3 Peter Seixas, Catherine Duguette, and the Canadians and Their Pasts collective (to list only a few) have all drawn upon Rüsen’s theoretical perspectives, in one way or another, when studying the historical consciousness of Canadians. In so doing, however, all of these researchers have selected distinct paths of inquiry that can be grouped into three broad categories: (1) historical consciousness as shared narratives, (2) historical consciousness as a way of thinking about the past, (3) and historical consciousness as an expression of everyday life. In addition, while all of these inquiries (as well as others not listed) have made a significant contribution to the understanding of historical consciousness in this country, their research attention has been focused upon individuals 15 years of age or older.4 To date, no empirical research has been undertaken with 7th grade students (aged 11–13 years) in Canada regarding their historical consciousness.

7 Canadians and Their Pasts represents an elaborate national alliance of academic researchers, universities, and community partners who worked together, over a period of ten years, to explore “the role that history plays in the lives of Canadian citizens” (Canadians and Their Pasts). Between 2007 and 2008, over three thousand Canadians were asked questions designed to (1) measure levels of general interest in the past, (2) identify activities participants engage in that relate to the past, (3) probe how these activities aid in their understanding of the past, (4) measure the perceived trustworthiness of specific sources of information, (5) probe the relative importance of various pasts, and (6) identify participants’ individual sense(s) of the past (Conrad et al., “I Want to Know” 2). The results have been recently published in book format, and present the first national glimpse into the historical consciousness of adult Canadians.

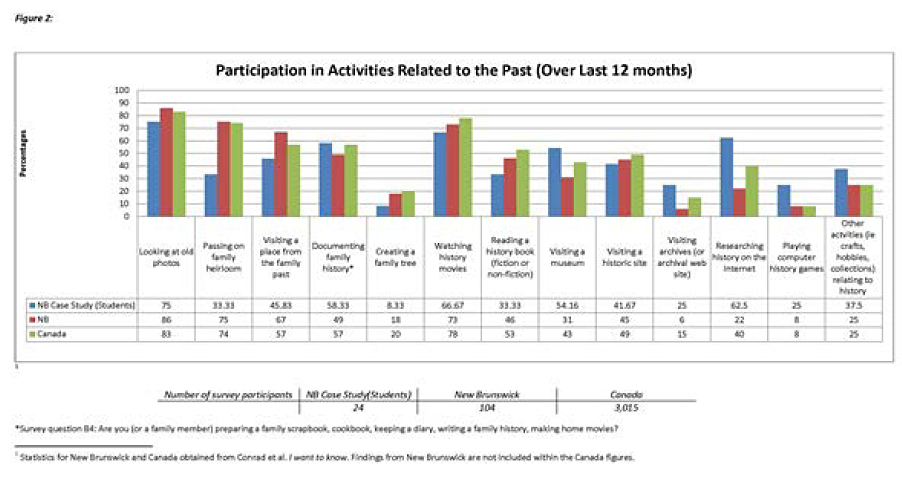

8 With respect to overall activities and attitudes, the findings from Canadians and Their Pasts indicate that a vast majority of adult Canadians engage with the past in very ordinary ways (29). Within the national sampling of individuals over the age of 18,5 four out of five respondents (83 percent) reported that over the past twelve months they had looked at old photographs of buildings, places, family members, or friends (30). In addition, 78 percent indicated that they had watched history films, while 74 percent said that they were preparing to pass on family heirlooms (30), and slightly more than half (57 percent) said that they had visited places from their family’s past or were documenting their family’s history through scrapbooks, cookbooks, diaries, or home movies (30).

9 In New Brunswick, the Canadians and Their Pasts study involved 104 adults over the age of 18 (Conrad et al., “I Want to Know” 5). These individuals were interviewed as part of the national survey, while an additional hundred Acadian adults were interviewed as part of a special (micro) sampling within the communities of Dieppe, Petit-Rocher, and Caraquet (5). Detailed findings relating specifically to New Brunswick have been published in the Journal of New Brunswick Studies (2010), and provide interesting perspectives on the historical consciousness of both Anglophone and Francophone adult New Brunswickers (Conrad et al., “I Want to Know”). In addition, the results of a satellite inquiry, undertaken by the Institute d’études acadiennes de l’Université de Moncton (IEA), involving 96 students in grade 12 (aged 17–18 years) within six Francophone schools in the Acadian region of the province, have been published in Acadiensis6 (Robichaud) as well as online (Robichaud and Giroux).

10 Overall, New Brunswick responses to the national survey reveal somewhat similar patterns of engagement with the past as in other parts of Canada. Four out of five New Brunswickers (86 percent) reported that over the past twelve months they had looked at old photographs of buildings, places, family members, or friends (19). In addition, 73 percent indicated that they had watched history films, while 75 percent said that they were preparing to pass on family heirlooms (19). Similarly, two-thirds (67 percent) of New Brunswick respondents said that they had visited places from their family’s past— although fewer (49 percent) were documenting their family’s history through scrapbooks, cookbooks, diaries, or home movies (19).

Mapping the Historical Consciousness of 7th Grade Students

11 Although it is important to emphasize that the research from Canadians and Their Pasts does not reflect youth, the resulting data does provide a rich glimpse into the historical consciousness of adults who populate their lives. As such, the findings cannot be dismissed from discussions regarding history education because they reveal some of the sociocultural influences youth encounter on a daily basis. More importantly, the adult data also provides a broad indication of the much larger epistemological question regarding ways of thinking about the past. Such ways of thinking are of pressing interest to history educators in Canada because they point directly to the challenge of teaching and understanding history: How do we “know” what we (think we) know about the past? (Seixas et al. 2). As a result, this research reports on preliminary data obtained from replicating and expanding upon the Canadians and Their Pasts survey with a group of 7th grade Anglophone students in New Brunswick.

Describing the Case Study

12 The student sample for this inquiry constituted an entire class of 7th grade social studies students (N = 24) that had been assigned to the project by their principal and cooperating teacher. The class contained ten female and fourteen male students. All of the students were Anglophone, ranging from 11 to 13 years, and all but four had been born in Canada. In addition, all of the students were enrolled in the course because they were required to do so, since social studies is a mandatory subject in 7th grade.

13 By nature of its historical setting, the students’ school seemed particularly conducive to the inquiry. With a total population of just over six hundred students, occupying twenty-eight classrooms and four specialty rooms, the classical-revival-style building seemed to surround students with a sense of the past. The structure stands as a historic landmark in the city, having functioned as a learning establishment for over eighty years. Immediately next door (where one would expect to find recreational facilities) rests a large and ornately enclosed burial ground, where many of the city’s founding citizens are memorialized. Containing graves dating as early as 1787, this burial ground has been recognized by the province of New Brunswick as a Local Historic Place (Province of New Brunswick).

14 At the time of conducting the inquiry, students had not yet been exposed to much classroom instruction in either Canadian or New Brunswick history. Nevertheless, many had participated in the provincial heritage fair program in 6th grade, and it was evident that this experience was etched in their memory. In social studies, the class had already completed an introductory unit on Canadian economics (both past and present), which introduced the concepts of empowerment, authority, and disempowerment. As a result, the cooperating teacher was preparing to teach the next unit on political empowerment, which focused on British North America and social movements leading up to Confederation (Sterling).

15 It was at this point in their studies that the students were asked to complete a written version of the Canadians and Their Pasts short-form questionnaire. They were also asked to respond to two open- ended essay questions about what they wished to remember about Canada’s and New Brunswick’s past. Those activities were undertaken as a mandatory in-class assignment that extended over four consecutive days in January 2013. The results are presented in the sections that follow.

Interest in History

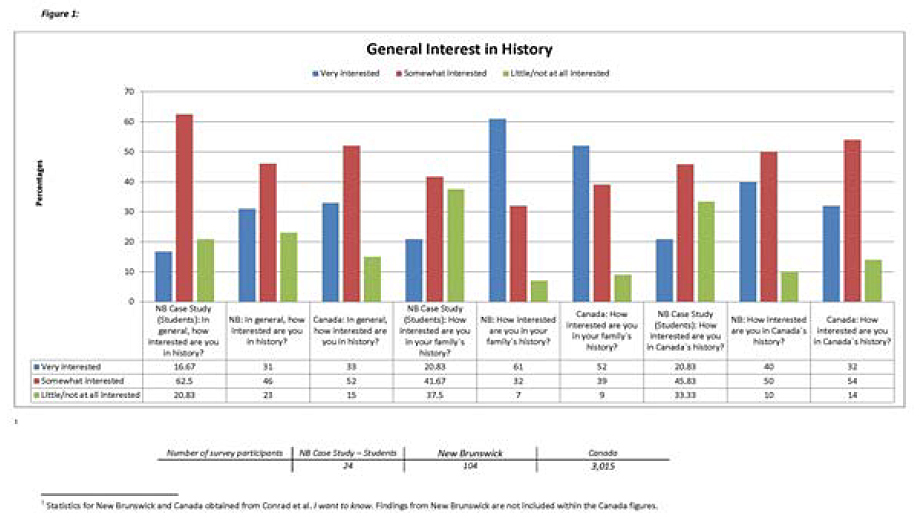

16 Overall, few of the 7th grade case study students reported that they were “very” interested in history—be that history in general, family history, or Canadian history (see figure 1). More precisely, only 17 percent stated that they were “very” interested in history in general, a response rate that was almost half that of adult samples in either New Brunswick or Canada. In addition, less than a quarter reported that they were “very” interested in family history, a rate that was also dramatically lower than provincial (61 percent) or national (52 percent) adult samples. Likewise, less than a quarter stated that they were “very” interested in Canadian history—also demonstrating a rate of interest that was considerably lower than provincial (40 percent) or national (32 percent) adult samples.7 Instead, over half of the students classified themselves as “somewhat” interested in history in general, and slightly less than half expressed a similar level of interest in either family or Canadian history.

17 Engaging with the Past

18 Nevertheless, while most students did not express the same level of interest in history as their adult counterparts, most did report very similar patterns of participation in heritage activities (see figure 2). Like their provincial and national adult counterparts, many 7th graders had spent time over the past 12 months looking at old photographs (75 percent), watching history movies (67 percent), and participating in family-oriented activities related to documenting their family’s history8 (58 percent). Conversely however, and very unlike their provincial and national adult counterparts, more students had spent time researching history on the Internet (63 percent), as well as visiting museums (54 percent), participating in crafts and hobbies (38 percent), playing computer history games (25 percent), and visiting archives or archival websites (25 percent). However, fewer students had spent time visiting a place from their family’s past (46 percent), passing on family heirlooms (33 percent), reading history books (33 percent), or creating a family tree (only 8 percent).

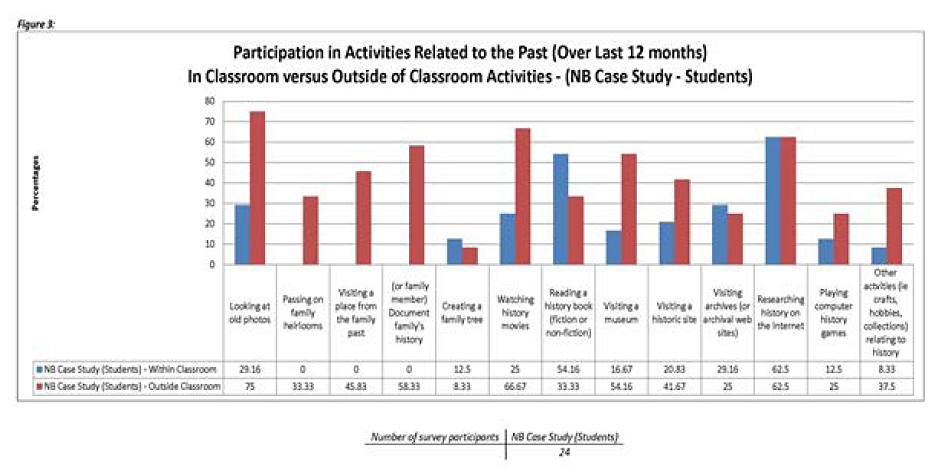

19 Of the many heritage activities in which students reported participating, reading history books had been primarily a classroom instructional activity, while researching history on the Internet was evenly distributed as an activity that over half of the students had engaged in—both inside and outside of the classroom (see figure 3). In addition, less popular activities, such as visiting archives or archival websites, playing computer history games, and creating a family tree were also closely distributed as both inside and outside of classroom activities.

20 Outside of classroom instruction, students primarily reported looking at old photographs (75 percent), as well as watching history movies (67 percent), documenting their family’s history (58 percent), or visiting museums (54 percent). To a lesser extent, they also reported visiting places from their family’s past (46 percent) or historic sites (42 percent), engaging in other heritage activities (38 percent) such as drawing and collecting stamps, reading history books (33 percent), passing on family heirlooms (33 percent), visiting archives or archival websites (25 percent), and playing computer history games (25 percent).

Understanding the Past

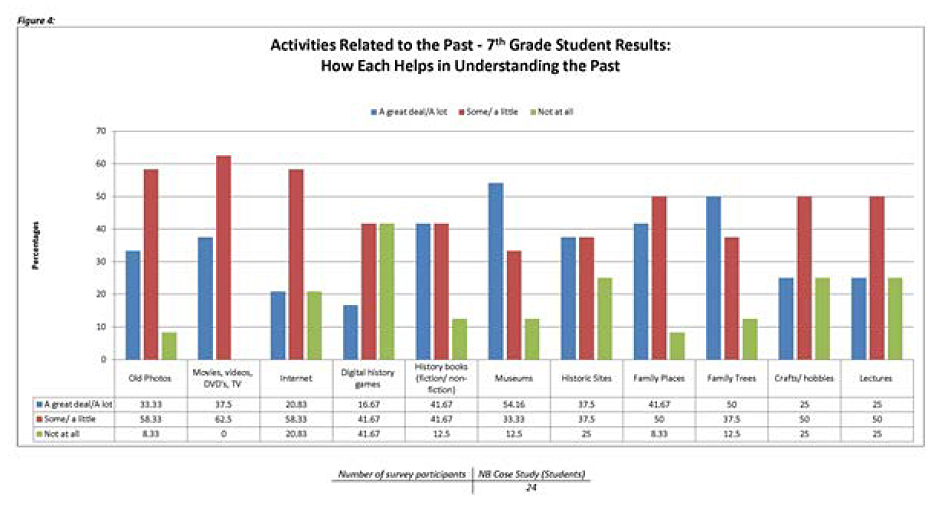

21 With regard to specific resources for learning and understanding the past, the largest proportion of students (54 percent) rated museums as being helpful a “great deal” (see figure 4). At the same time, more students also considered watching movies (63 percent), as well as looking at old photographs (58 percent) and playing computer history games (58 percent) as being “somewhat” helpful in understanding the past; however, less than a quarter found playing computer history games to be “very” helpful, and an equal percentage thought they were “not at all” helpful in understanding the past.

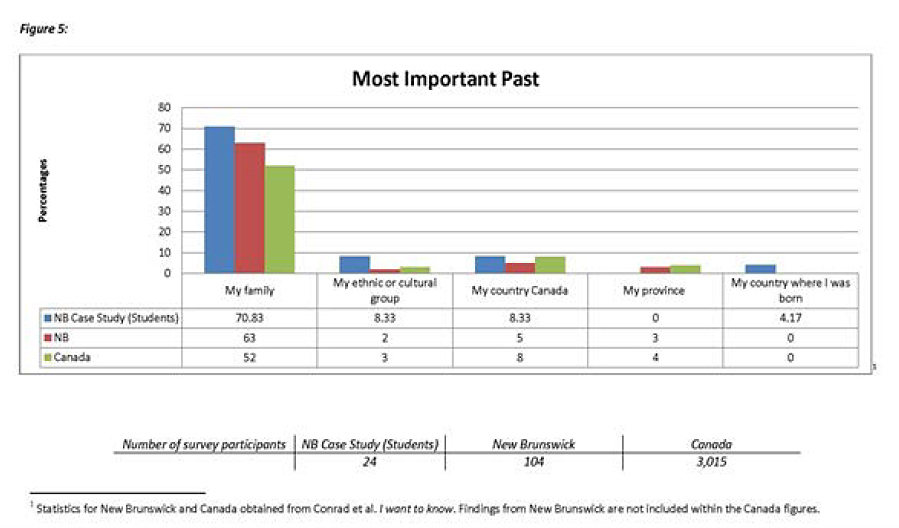

Importance of Various Pasts

22 When asked to consider the importance of various pasts (including the past of Canada, as well as New Brunswick and Atlantic Canada9 ), the largest proportion of students ranked their family’s past as “most important” to them (see figure 5). These findings are significant because, while the largest proportion of adult respondents in both New Brunswick (63 percent) and Canada (52 percent) ranked their family’s past as “most important,” even more students (71 percent) placed their highest level of importance upon this past. Students’ reasoning for their choice ranged from simple emotional connections—“Because I love my family”(GSMS ID 5)—to knowing how family members were connected to broader aspects of history. As Amanda10 explained, her family’s past was important to her “Because my family does maple syrup and sells it to people, and my grampy was in the war” (GSMS ID 19).

23 Interestingly, although none of the 7th graders valued New Brunswick’s past as “most important” to them, slightly more than half identified this past as “somewhat important” (58 percent)— followed to a lesser degree by Canada’s past (42 percent). In addition, almost two-thirds of the students (63 percent) indicated that they did not identify with Atlantic Canada’s past at all.

Thinking about History and the Past

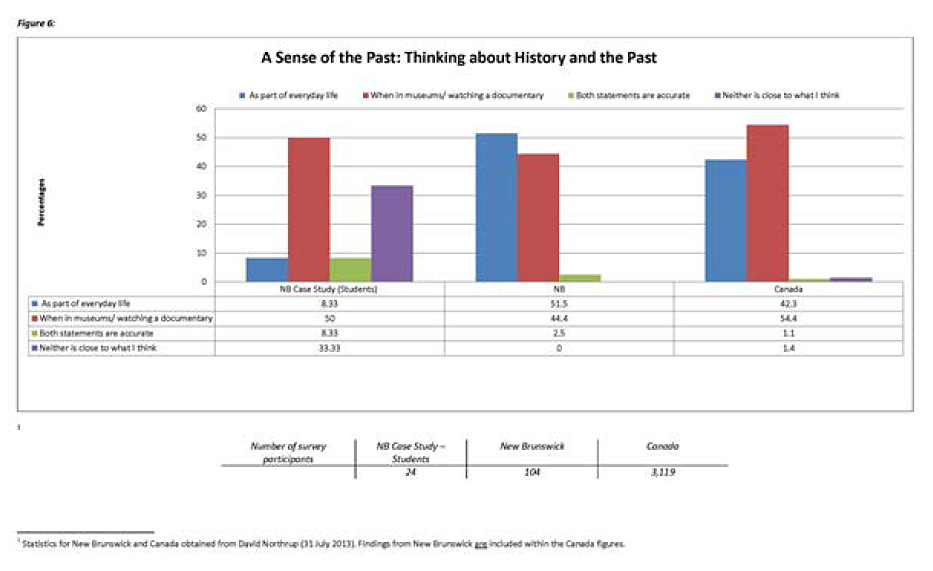

24 With respect to thinking about history and the past, the largest proportion of students (50 percent) agreed with the statement that they think about these subjects mostly when in museums or when watching history documentaries (see figure 6). These findings were somewhat similar to provincial and national adult samplings (Northrup). Where students differed from their adult counterparts, however, was that very few agreed with the statement that they think about history and the past “as part of living their everyday life.” As well, one-third of students indicated that neither statement was even close to what they thought.

Thinking about Change over Time

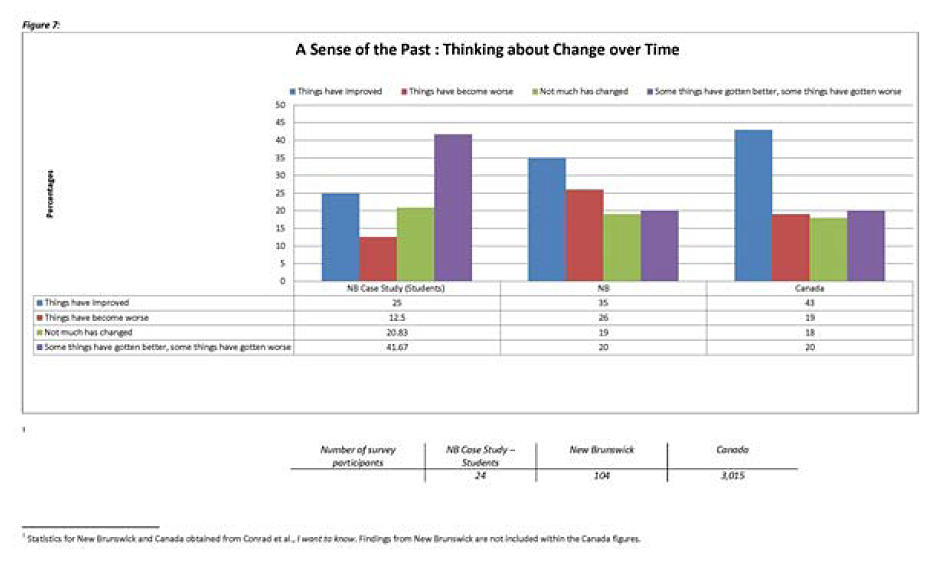

25 With respect to thinking about change over time, the largest proportion of 7th graders (42 percent) agreed with the statement that “some things have gotten better, some things have gotten worse” (see figure 7). Their reasoning for this choice was primarily based upon a belief that technology and quality of life had improved, while pollution and conflict had become worse:

- “Technology has helped us a lot. Factories have been polluting our planet” (GSMG ID 12);

- “I think that we have advanced in technology, but the world has become mean” (GSMS ID 15);

- “Our technology has become better. But our earths polution [sic] [has be]come worse, like the mills and polution [sic] in the air” (GSMS ID 19);

- “Worse: Polution [sic] Violence Crimes Better: Transportation Laws Schools” (GSMS ID 13).

26 These results were dissimilar to adult samplings, in which fewer New Brunswickers (35 percent) and slightly more Canadians (43 percent) opted for the more popular statement that things had improved over time. Only 20 percent of both adult sample groups made the same choice as their student counterparts.

Ways of Trusting in Authority

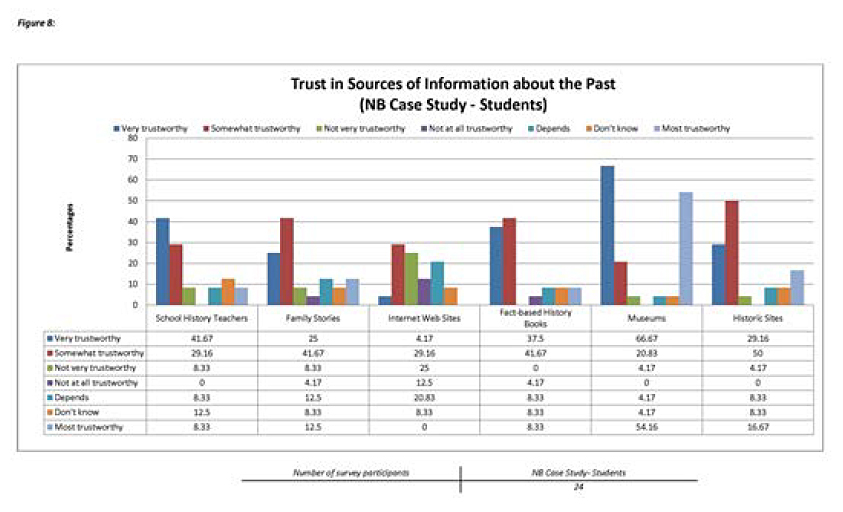

27 With regard to trusting in sources of information about the past, the largest proportion of students (54 percent) ranked museums as “most trustworthy” (see figure 8). This ranking was relatively high, since less than a quarter of New Brunswickers, and only one-third of Canadians, ranked museums as their most trustworthy source of information about the past (Northrup).11 Students’ primary explanation for their choice was that museums present “real things” or “artifacts,” and safeguard “knowledge” or “proof” about the past. Their reasoning also varied in sophistication—from a simple “just because” response (as in example 1) to recognizing aspects of investigation (example 4):

- Because museums are supposed to be trustworthy (GSMS ID 11);

- Something that makes sense like if I said King Henry had a rolex watch and a convertible no ones [sic] going to believe me but at museums when they have all this nolege [knowledge] there [sic] pretty trust worthy (GSMS ID 7);

- Because they get a lot of information from actual artifacts, instead of just stories that could be wrong (GSMS ID 3);

- Because the [stuff] at a museum is stuf[sic] that scientests [sic] have looked at and they no [sic] there [sic] stuf [sic] (GSMS 5).

These statements also demonstrated a wide range of trust in the authority of museums, ranging from what Seixas et al. have described as a low-level belief in “faith and its friends” (example 1), to beginning to recognize the role of epistemological expertise (example 2), or the notion of primary sources as evidence (example 3), and acknowledging the existence of a community of inquiry (example 4) (7–10).

28 Furthermore, while the largest majority of 7th graders ranked museums as “most trustworthy,” an even greater majority (67 percent) believed museums to be “very trustworthy” (see figure 8). This was followed by school history teachers (42 percent), and fact-based history books (38 percent). By extension, half of the students (50 percent) also believed historic sites to be “somewhat trustworthy,” followed evenly by family stories (42 percent) and fact-based history books (42 percent). In drawing comparisons with Canadians and Their Pasts, like 7th graders, the largest majority of provincial (59 percent) and national (66 percent) adults also believed museums to be “very trustworthy” (Conrad et al., “I Want to Know” 20). Likewise, 32 percent of New Brunswick and 41 percent of national respondents believed fact-based history books to be “very trustworthy” (Conrad et al., “I Want to Know” 20). Where the sample groups differed, however, was in their trust toward school history teachers. Unlike 7th graders, nearly half of whom (42 percent) ranked teachers as “very trustworthy,” less than a third of adults (28 percent provincially, 30 percent nationally) held the same level of trust in their teachers (Conrad et al., “I Want to Know” 20).

Ways of Resolving Disagreements

29 When asked how one might resolve conflicting interpretations about the past, 7th grade respondents proposed a variety of strategies. These ranged from simply asking someone, to reading books, or undertaking more research:

- They can ask someone you trust or find a reliable website (GSMS 9);

- I would ask them to see museums and to read books. Then they can know that it happened (GSMS ID 1);

- They can try and do more research, use different sources and try and come up with logical explanations (GSMS 3);

- They can go to the historic sites, do research, visit museums (GSMS 23).

30 As these statements illustrate, few students (17 percent) suggested a strategy (as in example 1) of simply turning to social groups—what Seixas et al. describe as “weak moves” (11); yet, less than a quarter (21 percent) recognized the notion of investigating primary sources (example 3), or acknowledged (as in example 4) the role of a community of inquiry—what Seixas et al. describe as a “strong response” (11). Instead, the majority of students (63 percent) demonstrated a basic notion (as in example 2) of consulting with experts or secondary sources to find a resolution to conflicting interpretations—what Seixas et al. describe as a “good start” (11).

31 These findings are revealing because they suggest ways in which this group of 7th grade students understood the problem of knowing the past. For the largest proportion, when people disagreed about history, it was simply a matter of turning to museums, teachers, or books—as a way of consulting with experts—to find out what happened. Unfortunately, such a strategy leaves very little space for coping with conflicting historical narratives. It also suggests that most of the students did not see themselves as part of the expert community of inquiry. Instead, history was something that someone more knowledgeable did for them.

Remembering Canada’s Past

32 As well as completing the Canadians and Their Pasts short-form questionnaire, students participating in this case study were asked to write two brief essays on what history they wished to remember about their country’s past and New Brunswick’s past. These questions had been adapted from Clarke’s ethnographic study of Gaspésian youth, and were intended to isolate students’ interests in history. The resulting written statements were coded deductively, and then grouped around emerging narrative themes, to reveal a variety of beliefs about what students wished to remember. As such, these templates reveal some of the collective memory narratives that this group of 7th graders carried into the inquiry.

33 With respect to remembering their country’s past, it is important to note that for most of the students, “my country” meant Canada—but this was not the case for all. Two in the class had recently immigrated to New Brunswick with their families, and one student actually returned to his home country before the inquiry was completed. Ultimately, however, out of a total of 41 coded statements, the greatest proportion of student responses (fourteen in total; 34 percent) reflected traditional (inherited) obligations for remembering their nation’s past. These statements represented two distinct templates: “Our privileged nation” and “Those who made sacrifices in war.”

34 Our Privileged Nation. Students who employed this narrative wished to remember that Canada is a great nation: it is a “free country”; it is “the safest country in the world”; “we have good money” and live “not in poverty.” In addition, some students elaborated upon these qualities by reasoning that “we fight for what we think is right” and are privileged “with all our rights and freedoms.” As Janet explained: “I wish to remember that Canada is a great country. They don’t care if your [sic] black. Also that Canada is a free country. That we fight for what we think is right. That people made sacerfices [sic] for our country so that we today can be free” (GSMS ID 22).

35 Those Who Made Sacrifices in War. Drawing heavily upon the act of remembrance, students who employed this narrative wished to remember the soldiers who sacrificed their lives for freedom. As Carl so passionately stated:

36 Wars My Country Took Part In. As an extension of the last example, seven of the students also presented a narrative template that focused specifically upon war as a historical event. These statements differed from previous examples, however, since students who employed this schema approached history as exemplary—disconnected from the present—and frozen in time. As Karma wrote of isolated war exemplars: “I would like to remember all the history of my country and it’s very important, so I would like to search and to remember the wars and the people that lived in my country” (GSMS ID 1).

37 Similarly, another student offered an even more specific response, citing a particular conflict in recent history as an example of “what Canadians can do”:

38 Yet, in addition to such predominant narratives of privilege and war, nine of the students chose to employ two other very closely related (yet slightly different) templates for remembering Canada’s past: “What was before what we have today” and “When life was better than today.”

39 What Was Before What We Have Today. Those who adopted this template made reference to change—specifically, change in the Canadian flag, natural resources, or transportation. These students wished to remember aspects of the past that were connected to the present. In so doing, they demonstrated a more temporal relationship with Canada’s past. As Sandy explained: “I wish to remember what the flag was before our current flag because I think it is important for younger generations to know we havn’t [sic] always had the same flag” (GSMS ID 4).

40 When Life Was Better Than Today. Although only two students chose to employ this template, both clearly adopted a then-versus-now strategy that was somewhat similar to a “What was before what we have today.” How their narratives differed, however, is that both students made an assumption that life in the past had been better than in the present. As Brendan stated: “I would like to remember when kids weren’t abused or when Donald Marshall Jr. got the fishing rights for the Mik’maq people in Nova Scotia” (GSMS ID 8).

41 In reading through these examples of remembering Canada’s past, what becomes evident is that most of the students did not adopt a single narrative when formulating their responses to the essay question. Clearly, for example, Brendan did not exclusively adopt a “When life was better than today” schema. Instead, he made reference to a specific historic event that can be interpreted as a “What was before what we have today” statement. Like Brendan, all but seven of the twenty-four students constructed hybrid responses to the essay question, drawing upon two (or sometimes three) of the identified narrative templates.

Remembering New Brunswick’s Past

42 When asked to write about what history they wished to remember about New Brunswick’s past, the narrative templates that students employed for their province were far less elaborate than for their country. Several individuals seemed to be at a loss for words, since five of the students indicated that they did not know what they wished to remember, and four others stated that they simply wanted to learn more, or that they wanted to remember everything. Nevertheless, out of a total of thirty-six coded statements, the largest proportion of responses (eight in total) reflected a “Founding of a province” narrative.

43 Founding of a Province. Students who employed this template explained that they wished to remember the provincial flag, as well as how New Brunswick came to be named, when it was first “discovered,” and the people who “worked hard to create this province.” These narratives proposed specific symbols, events, or groups of people, as isolated exemplars that seemed disconnected from the present. As Samuel so passionately explained: “I wish to remember the people who created and formed New Brunswick. They worked hard to create this province. I think they should be remembered” (GSMS ID 16).

44 How People Lived Back Then. Alternatively, five of the students adopted a lifestyle template, wishing to remember what New Brunswick was like—and what people did—in the “olden days.” These narratives differed from previous examples, since students who employed this schema recognized a temporal distinction between “before” and “after.” As Alice so frankly explained: “I don’t know very much history about N.B. in the first place, and wish to remember everything I ever learn about it. I am interested to learn what N.B. was like before the europeans [sic] came over” (GSMS ID 3).

45 In reading these samples of remembering New Brunswick’s past, what becomes evident is that this group of 7th graders seemed eager to know more about their province. They also expressed enthusiasm for learning in a way that was people-oriented. Unfortunately, however, while their interest in New Brunswick’s past seemed very high, their level of prior knowledge seemed very low.

Discussion

46 Although these findings are by no means representative of all youth in New Brunswick, they do raise some interesting points for consideration by public historians. First, while very few students expressed a high level of interest in history, approximately half considered themselves to be “somewhat” interested, and more than half considered New Brunswick’s past to be “somewhat important.” This would suggest that the potential for greater interest in history remains a tangible possibility for these students. Like their adult counterparts across Canada, however, students placed more importance upon their family’s past. Hence, enabling 7th grade students to establish family connections to broader aspects of provincial and national history would contribute greatly to their knowledge and interest in New Brunswick’s past.

47 Second, this group of 7th graders reported very similar patterns of engagement in heritage activities as adult New Brunswickers. Where they differed, however, was that more students had spent time researching history on the Internet, visiting museums, or participating in crafts and hobbies, while fewer students had participated in passing on family heirlooms or reading history books. Furthermore, reading history books was reported as primarily a classroom instructional activity, while watching history movies or visiting museums and historic sites were primarily extracurricular activities. Researching history on the Internet, on the other hand, was both an inside- and outside-of-classroom pursuit. This would suggest a demographic shift in patterns of engagement with the past, of which public historians must be ever cognizant.

48 Third, with regard to sites for learning, the largest proportion of students in this case study considered museums to be helpful—a “great deal”—in understanding the past. In addition, the largest proportion of students (more than half) ranked museums as the “most trustworthy” source of information, and an even larger majority believed museums to be “very trustworthy.” Moreover, half of the students indicated that they thought about the past mostly when in museums or when watching history movies. These findings point to the great potential that museums hold in facilitating history education for youth in this province. As Cormier and Savoie have demonstrated, museums have the potential to strengthen our public school system (52–53). By overlooking the trust students place in such tangible aspects of our past, classroom instruction is indeed missing the mark.

49 Fourth, it is particularly significant to note how these students positioned themselves within the landscape of public history education. While a majority demonstrated some basic notion of consulting with history experts or secondary sources to find resolution to conflicting interpretations about the past, most students did not perceive themselves as part of this community of inquiry. Instead, history was something that someone more knowledgeable did for them. This phenomenon points to the necessity of enabling students to be more actively involved—not just bystanders—in New Brunswick’s community of historical inquiry. This will require that the community open its doors to young scholars by facilitating sophisticated and critical investigation of the narratives they perpetuate.

Conclusion

50 This research report presents an intriguing description of the what and the way behind 7th grade student engagement with the past in New Brunswick. At a time when history education is undergoing extensive reform across Canada, the findings present an urgent call to action for New Brunswick educators to consider more closely the epistemological beliefs that students bring to and take away from classroom instruction. At the same time, these findings draw attention to the central role that museums might play in enabling more critical approaches to history and how it is constructed. Certainly a more sophisticated pedagogy for history education, as the Historical Thinking Project has proposed, presents an important first step in this regard; however, isolated classroom instruction alone is not sufficient. Public history sites of learning must also embrace this reform. In extending our vision for sophisticated learning beyond the classrooms of New Brunswick, these findings lead us to reconsider how history education might be more tightly woven into students’ experiences of living their lives in this province.

Cynthia Wallace-Casey is a PhD candidate in history education at UNB. Her research investigates communities, museums, and historical thinking.