Research Notes and Reviews

Temporary Foreign Workers in New Brunswick’s Rural Communities

Abstract

Faced with local labour shortages, businesses in New Brunswick’s rural communities have been turning to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) to hire workers to fill “low-waged” jobs even though the federal government has been wary of the fact that migrant workers are being hired in areas where unemployment has been high. This research note argues that while the TFWP can be seen as a way to respond to the recruitment and retention problems of New Brunswick businesses, it does at the same time leave migrant workers in a precarious legal state. Taking as a future case study the village of Cap-Pelé, where migrant workers have been filling jobs in the fish and seafood processing plants, it suggests that there is a need to ethnographically investigate the impact that the TFWP has on migrant workers, the businesses that hire them, and the rural communities that welcome them.

Résumé

Dans les communautés rurales du Nouveau-Brunswick, la pénurie de main-d’œuvre locale incite les entreprises à recourir au Programme des travailleurs étrangers temporaires (PTÉT) pour remplir des emplois à rémunération moins élevée, et ce, malgré le fait que le gouvernement le fédéral demeure perplexe devant l’embauche de travailleurs migrants dans des régions où le taux de chômage est élevé. Cette note de recherche souhaite démontrer que le PTÉT peut être considéré comme une façon de répondre aux problèmes de recrutement et de rétention auxquels font face les entreprises du Nouveau-Brunswick, mais qu’il laisse en même temps les travailleurs migrants dans une situation légale précaire. Prenant comme étude de cas le village de Cap-Pelé, où des travailleurs migrants occupent des emplois dans les usines de transformation de poissons et de fruits de mer, il est suggéré qu’il est nécessaire d’étudier ethnographiquement l’impact qu’a le PTÉT sur les travailleurs migrants, les entreprises qui les embauchent et les communautés rurales qui les accueillent.

Introduction

1 Businesses in New Brunswick’s rural communities have recently turned to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) to address labour needs, a trend that has transformed the ethnic and cultural composition of these mostly homogenous communities. This is a significant change for communities historically less marked by the diversity of migration flows. Confronted with a skills mismatch, rural businesses have been recruiting temporary foreign workers to fill “low-waged”1 jobs (Atlantic Provinces Economic Council [APEC], Meeting 36), a practice related to the controversy surrounding the federal government’s 2013 Employment Insurance (EI) program reforms. While rural communities in the province have been uneasy about the social impact of this reform, the federal government has remained perplexed by the fact that temporary foreign workers are being hired in communities marked by both scarce employment opportunities and high unemployment rates (O’Neil).

2 Prior to these reforms, Jason Kenney, minister of Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) at the time, pledged to stop “this bizarre situation where we’re bringing in foreigners to do the work in areas with double-digit unemployment” (O’Neil). Businesses located in areas with high unemployment rates, his story goes, should not have to look over there (abroad) to find workers when there are workers available here. Against this backdrop, why then do New Brunswick businesses turn to the TFWP to fill their labour needs? What do they find so attractive about it? What is the nature of the so-called labour shortages? And what impact does this form of temporary labour migration have on migrant workers and the communities that welcome them? These are some of the questions that this paper explores. This issue as it pertains to New Brunswick has not received much scholarly attention,2 and while more exploratory in scope (Streb), this research note is a first step in this regard.

3 This paper makes two arguments. First, it argues that there is an inherent structural tension at the core of the TFWP. Because of the mobility restriction that it imposes on migrant workers once they are in the country, the program can be considered as successful in helping businesses in rural New Brunswick retain workers when there is no local workforce readily available (or interested) to fill existing labour shortages. But, at the same time, this retention power leaves migrant workers in a precarious legal status since their temporary stay is conditional to the continuous sponsorship of their employer. Secondly, it argues that to better understand the implications the TFWP has for New Brunswick, there is a need to pursue a place-based critical ethnography to grasp the program’s impact on the ground by considering the point of view of migrant workers, rural businesses, local workers, and local community stakeholders.

4 Thus the first section of this paper examines the often-conflicting narratives constructed with respect to the hiring of temporary foreign workers in a province marked with high unemployment. The second section examines the TFWP by focusing on the retention/precariousness tension and what it means for New Brunswick businesses and the migrant workers involved. The last section proposes the need for ethnographically informed research, suggesting as a future case study the small, francophone, rural, fish and seafood processing community of Cap-Pelé.

New Brunswick’s Labour Market: Shortages and Retention Issues

5 This section sketches the conflicting narratives that have been constructed with respect to New Brunswick’s labour force issues. This will serve as context for understanding the practice of hiring temporary foreign workers by New Brunswick businesses. However, this practice has been frowned upon by the federal government, because the government—citing New Brunswick’s high unemployment rate—denies the existence of labour shortages in the province. What will become clear is that the situation is complicated and evolving.

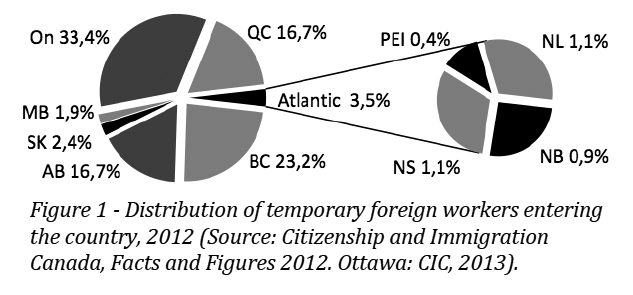

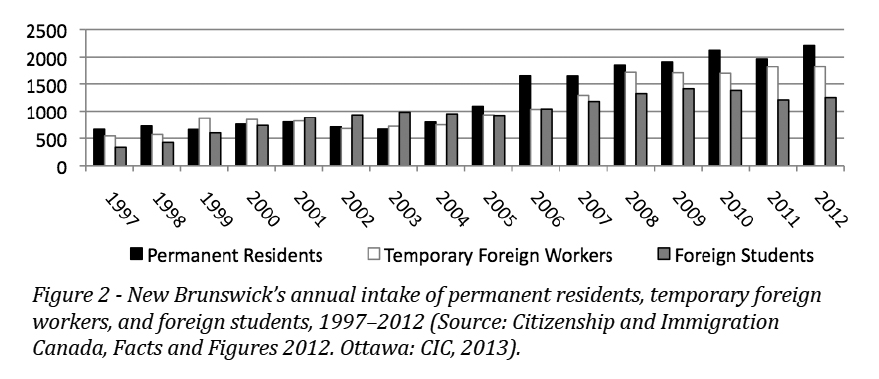

6 With the number of migrant workers entering New Brunswick annually being significantly less than other provinces (see Figure 1), why pay attention to it? The reason is that although it has low annual immigration levels, New Brunswick does welcome a surprisingly high proportion of migrant workers each year. As seen in Figure 2, the number of temporary foreign workers entering the province has sharply increased in the last decade, growing at an average annual rate of 15.5 percent. Also, it is relevant to note that when foreign students are taken into account, an interesting permanent-temporary divide is taking place in New Brunswick; the total number of temporary residents entering the province annually has in recent history been higher than the number of admitted permanent residents. Another interesting trend is that, unlike permanent residents who mostly choose to settle in urban areas (see Figure 3), migrant workers are mostly employed outside these areas (Figure 4), bringing a new ethnic and cultural dimension to communities less familiar with diversity and multiculturalism.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 47 These trends are not arbitrary; New Brunswick is experiencing significant demographic challenges, which are not without economic consequences. The lack of population growth is leading to labour shortages as the pool of available local workers is shrinking (Akbari 11–12). Furthermore, this population decline is more intensely felt in rural areas, and it should be cause for grave concern as natural resource–based industries are mostly found in these non-urban, usually distant communities (Akbari 12).

8 Similarly, the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council (APEC) stresses that the lack of labour force growth in Atlantic Canada is related to both its economic situation and its longer-term demographic challenges. With limited employment prospects, there has been an increase in the outmigration of people to take jobs in western Canada’s booming economy, especially among young adults. Although some Atlantic Canadians have few incentives to move, many younger workers are attracted to enhanced wages, benefits, and training, not just immediately but over their lifetime (APEC, Where 1–2; Ferguson). This outmigration of young talented workers has been linked to New Brunswick’s “sluggish economic” recovery (“Slow Economy”). The demographic situation is further complicated by the large portion of baby boomers who are nearing retirement, amplifying the labour needs of certain industries (APEC, Where 3). With the development of the knowledge and service economy, people in rural areas have been moving closer to cities or leaving the province altogether (APEC, As Labour Markets 2).

9 However, most jobs filled by temporary foreign workers in New Brunswick are classified as “low-waged.” As the president of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour stated, “If you look all those [businesses] who have some [temporary foreign workers] in New Brunswick, it pays minimum wage or close to minimum wage, and yourself if you have some children, you don’t want them to work minimum wage, you want better than that” (qtd. in Hobson A1). He suggests that in order to retain young adults there is a need to start offering better wages. Even with better wages, it is debatable whether people coming out of university or college would agree to stay and work at a job that does not put their acquired skills to good use. This is what is meant in New Brunswick when talking of skills mismatch: young educated people are overqualified for these types of jobs (APEC, Meeting 36; “Budget Watchdog”).

10 As such, temporary foreign workers have become to some extent the new faces of the service industry (e.g., fast-food restaurants) and a vital addition to the seasonal workforce (e.g., fruit and vegetable harvesters and seafood processing plant workers). This trend does not sit well with the current Conservative federal government. Rob Moore, minister of the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (ACOA), believes that there is a need to fix the current disconnect between Canadian workers and available jobs: “We have in New Brunswick and throughout Canada businesses that are bringing in temporary foreign workers to do jobs that New Brunswickers, that Canadians, could be doing, including in areas where there is high unemployment. That is obviously not acceptable” (qtd. in Huras A1).

11 Thus, the federal government has made it its mission to harmonize the practice of hiring temporary foreign workers with the labour realities of the country. Their efforts until recently had mostly been directed toward reforming the EI program, which some have interpreted as an attack on the seasonal work characteristic of New Brunswick’s rural communities (see Caron).

12 Changes to the EI program include tougher regulations, such as accepting available employment opportunities within a distance of an hour-long commute, taking lower-paying jobs, and rigorously documenting job searches. This implies that work for Canadian citizens, unlike temporary foreign workers, is not a right but a duty. Citizens need to be mobile and flexible to find the employment reserved for them by either committing to a longer daily commute or accepting lower-paying jobs (Anderson, Us and Them? 27). Hence, the federal government’s rationale is to put people to work, whatever the job may be. As former minister Kenney said: “We’re going to go to the local work population and say, ‘Look, the fish processing plant is hiring. Have you applied for that job?’ And if they say no, we’re going to say, ‘Well, look, you’re not actually trying to get other employment.’” (qtd. in O’Neil).

13 Diane Finley, minister of Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) at the time, plainly explained that the idea is to make sure that businesses do not need to hire temporary foreign workers when people on EI with the required skills are available. She uses the example of seasonal workers employed in fish plants, and suggests that once their work season is over the normal or required conduct should be for them to be working at places like fast-food restaurants, establishments that have been recruiting migrant workers to fill shortages (“Seasonal”). The problem with this solution is that seasonal industries such as fishing and agriculture have also been having a hard time finding and retaining workers at the peak of their respective production periods, and have turned to the TFWP to fill their labour needs (Nabuurs; APEC, Meeting).

14 This section has shown that there are different stories about New Brunswick’s labour force issues. Because of pressing demographic problems, rural businesses have had a hard time finding local workers to run their operations. Some stakeholders point to the lack of jobs with competitive wages, which push young adults to leave the province. Other stakeholders, such as the federal government, point to unemployed seasonal workers as the solution to solve the province’s labour woes in the off- season. But, as stressed, seasonal industries in the province are also facing important recruitment challenges. Thus, to run their businesses more smoothly these industries have increasingly turned to the TFWP because of the workforce retention it gives them. The landscape, then, is complex, which mitigates the kind of “forced” solutions that the federal government envisions.

New Brunswick and the TFWP: Between Retention and Precariousness

15 As reported by the federal government, the TFWP “allows Canadian employers to hire foreign nationals to fill temporary labour and skills shortages when qualified Canadian citizens or permanent residents are not available” (Canada, Factsheet). Thus, the stated objective of the program is to help businesses address pressing shortages that are defined as temporary; the temporariness of foreign workers is based on this assertion. As Foster reminds us, even though “the TFWP was trumpeted as a flexible solution to a short-term labour shortage problem and that it was sensitive to employer demand for workers,” it remains that the program’s rationale is based on the idea that once there is a deflation of the labour demand by businesses, the essential elasticity of the program should “allow for a subsequent reduction in foreign workers” (23). With the program continually expanding since its inception in 1973, Foster concludes that it has been silently entrenched as a permanent component of the Canadian labour market. As such, the TFWP has drifted from its original stated purpose as a program to deal with shortages to one with “the broader function of regulating labour supply in a fashion optimal for employer bargaining power” (42).

16 The impressive increase in the number of migrant workers in New Brunswick is the result of the federal government’s expansion of the TFWP in 2002. In response to escalating pressures from the business community—notably in the oil, gas, and construction industries in Alberta—the federal government launched the pilot project for hiring foreign workers in occupations that require lower levels of formal training. Now incorporated as a full-fledged component of the TFWP, this stream enables businesses with labour needs to hire temporary foreign workers for “low-waged” jobs. This development has opened the door for certain industries in New Brunswick, such as the fish and seafood processing industry, to hire foreign workers to fill labour shortages, a source of labour that this industry did not have access to previously. The creation of this stream “somehow marks the institutionalization and expansion of what had hitherto been specific and punctual measures” (Noiseux 403).

17 Furthermore, this stream has not only given New Brunswick businesses a new pool of labour, but some would argue that it discourages them from finding other ways to respond to shortages such as “increas[ing] wages and/or improv[ing] working conditions to attract more citizens who are either inactive, unemployed or employed in others sectors” (Anderson and Ruhs 34). Without encouraging businesses to devise ways to make their vacant jobs more attractive, the government is turning migrant workers into simple “stop-gap” instruments. Therefore, it is important to consider the nature or meaning of the shortages to which businesses in New Brunswick are referring. Labour shortages in New Brunswick “rather than reflecting purely quantitative gaps within the…labour market are defined qualitatively as well” (Sharma 108). This means that some businesses are short of workers of a specific “kind,” for example, those willing to accept jobs with work conditions that are deemed undesirable, unattractive, or unacceptable (108). Thus temporary foreign workers are becoming the preferred solution to fill these unwanted jobs (Gomez 6).

18 The instrumental use of the workers is made all the more clear by the mobility restriction imposed upon them once they are on Canadian soil. Temporary foreign workers hired to fill “low- waged” shortages are only authorized to work for the employer who hired them, and are therefore not allowed to circulate in the Canadian labour market freely (Helly, Dépatie-Pelletier, and Gibson 6–7; Fudge and McPhail 8). As Preisbisch and Hennebry stress, “migrants’ mobility in the labour market is highly restricted by work permits that are valid with a single, designated employer; migrants cannot legally work for someone else without negotiating a transfer and receiving Canadian government approval to do so, a procedure that in practice is very difficult to accomplish” (54). In effect, a migrant worker hired by a New Brunswick company is not allowed to freely accept other work opportunities inside or outside the province. This mobility restriction, however, is for the most part targeted at migrant workers filling “low-waged” jobs, and thus differs from a “high-waged” scenario. Businesses in New Brunswick seeking to fill “low-waged” jobs need to apply to ESDC for a labour market impact assessment before being able to recruit abroad, which is not necessarily the case when seeking workers for “high-waged” positions.

19 Compared to EI claimants who are asked to be more mobile to answer to the province’s labour needs, migrant workers are made immobile once they are on location and reduced to “unfree, contract labour” (Sharma 108; Noiseux 404; Basok). Furthermore, these migrant workers are not necessarily hired to fill actual quantitative shortages, as the TFWP is intended to do, but used to fill qualitative labour needs: “Migrant workers were (and are) recruited for those jobs that were (and are) not qualitatively ‘attractive’ to those not legally indentured to perform them” (Sharma 99). Even though the EI claimants are encouraged to fill “unattractive” jobs, as citizens or permanent residents, they are free to reject these jobs (while also accepting that by doing so they might no longer be eligible for EI). As for migrant workers, their employment, and temporary residency status, is conditional on the fact that they respect the mobility restriction imposed by their work visas.

20 That these temporary foreign workers are tied by their work visas to one specific employer makes them even more attractive to New Brunswick businesses, as the TFWP gives employers significant control over the retention of the hired help, which can also be used (or abused) as a form of disciplinary power. As Anderson states, “Employers are handed additional means of control: should they have any reason to be displeased with the worker’s performance, or indeed even have a personal grudge against them, not only the worker’s job, but their residency, can be put in jeopardy” (Us and Them? 89). This unequal employment relationship, where employers are given retention power, means that migrant workers who wish to take advantage of this economic opportunity are left in an uncertain and precarious situation: because the power to retain also means the power to dismiss, cases of dismissal are tantamount to acts of deportation (Us and Them? 89; see also Anderson, “Migration” 312). With this uncertainty in mind, migrant workers tend to make every effort to be disciplined as they feel “a pressure to maximize the ‘now’” (Us and Them? 89).

21 This is not to suggest that New Brunswick employers abuse their temporary foreign employees. Rather, it is meant to point out that retention power is structured into the TFWP, which puts migrant workers in a precarious legal state. Temporary foreign workers do technically have a legal status in Canada in that they are authorized by the state to temporarily live and work in the country; however, their status is precarious because not only do they lack the rights and entitlements given to permanent residents, but their right to reside and work in Canada is dependent on the will (and whim) of the third party who sponsors their stay (Goldring, Berinstein, and Bernhard 250).

22 Lastly, it is worth noting that migrant workers hired for “low-waged” jobs are mostly excluded from accessing permanent residency. While “high-waged” temporary foreign workers, deemed as a “desirable” source of economic immigration, can apply for permanent residency from within the country (Hennebry 62; Sweetman and Warman 59), “low-waged” workers are reduced to a “necessary stop-gap” instrument to fill labour shortages (Rajkumar et al. 486). Hence, they are not invited to stay because they are considered as a possible drain on the welfare system (Lenard 173–74). The best bet for “low-waged” migrant workers employed in New Brunswick is to apply through the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP). While the province allows them to apply for nomination, the human capital point-based system of the program still makes it very hard for them to get nominated. Thus most “low-waged” temporary foreign workers are stuck in a process of circular migration, becoming “perpetual migrants” (Le Blanc 77) as their residence and status in the country remains permanently temporary (Rajkumar et al. 486).

Toward a Critical Ethnographic Field Study of Temporary Foreign Workers Living and Working in the Village of Cap-Pelé

23 There is a need to further examine the impact that the TFWP (and its inherent tensions) have on the everyday lives of temporary foreign workers, the business people who hire them, and the communities that welcome them. This section suggests, by using as a possible future case study the fish and seafood processing industry in the village of Cap-Pelé, a place-based critical ethnography as a way to assess the human impact of the program. As Leach explains: “A key contribution of ethnography to migration studies is to examine policy from the perspective of the migrant, taking seriously migrants’ collective and individual agency” (34). Since the impact of the TFWP is multifaceted, it is important to include the perspectives and experiences of the other stakeholders involved. Before turning to the case study, it is necessary to sketch briefly what is meant by place-based critical ethnography.

24 First, the rationale behind a place-based approach is that the impact of the TFWP might not be the same from one location to another. Since the program is national in scope and applies to all regions similarly, such an approach can help better understand the experiences lived in lesser-known and remote places. The goal here is not to produce generalizations but more meaningful place-based singular accounts. Second, ethnography is taken here to mean the exercise of the ethnographer engaging and immersing in a particular place or community by building rapport with individuals and by looking at everyday habits and activities. Finally, the adjective “critical” signifies that this is not a “neutral, objective, value-free” research method, as ethnographers “serve as lenses, selecting and interpreting ‘scenes’ and ‘scripts’” (McHugh 75) that are part of a larger sociocultural environment, producing what Geertz calls “thick descriptions.” A place-based critical ethnography thereby allows the researcher to communicate a sense of place and community, while remaining reflexive.

25 While projective in scope, the goal of the rest of this section is to bring forward a pertinent (non- exhaustive) set of questions on how this issue, as it relates to a small fish and seafood processing New Brunswick village, can be further ethnographically examined.

The Fish and Seafood Processing Industry: Employers’ and Local Workers’ Perspectives

26 The fish and seafood processing industries, a sector that has not yet been studied from the point of view of ethnographic migration studies,3 has been struggling with recruitment and retention of new employees. This was reiterated following the recent changes to the TFWP announced in June 2014 (Leblanc) that now impose a cap on the proportion of temporary foreign workers that businesses are allowed to recruit per location.4 In some of the fish and seafood processing plants in the province, half of the workforce is composed of temporary foreign workers coming from countries such as the Philippines, Vietnam, Mexico, and Jamaica.5 Part of the reason for this unusually high reliance on temporary foreign workers is that the fish and seafood processing industry in New Brunswick has experienced a wave of change in recent years. Importing lobster from Maine means that plants are operating for longer periods and that more workers are needed to produce at full capacity.6 Unable to retain new young recruits as the “older generation” of fish plant workers leave the labour market, the fish and seafood processing industry finds itself in a difficult situation that the TFWP has been able to alleviate. Because this industry is vital to many rural economies (Beaudin and Savoie; Beaudin), it is essential to further investigate the extent to which temporary foreign workers are fundamental contributors to the survival of rural New Brunswick.

27 Ever since the controversy surrounding the food sector’s use of the TFWP, businesses have for the most part been viewed as the “bad guys.” There is, therefore, a need to better understand the specific views of businesses in the processing industry. First, an investigation of how these businesses interpret the economic and labour woes of the province is called for in order to grasp their understanding of the nature of labour shortages as it applies to their industry. Related is the need to see what strategies and practices are being put in place to attract and retain local workers. These research endeavours would also help shed light on whether the use of the TFWP has resulted in job losses for the local labour force. These inquiries could be further nuanced by considering the motivations of members of the local labour force, who choose not to take available jobs. As well, the study should examine how the program has worked for businesses, how employers make sense of the precarious legal status of temporary foreign employees, and what human resources’ processes and bureaucracy are involved in recruiting workers from abroad. Such emphases can explain why this has been the favoured solution. Knowing that New Brunswick’s reputation with immigrant retention is poor, is it fair to assume that businesses would not endorse the idea of letting “low-waged” migrant workers acquire permanent residency since they would then be free to navigate the labour market, potentially leaving the province? Or, in the scenario where the shortages of local workers are effectively qualitative and permanent, would businesses defend the position that foreign workers could become a permanent addition to their workforce if granted permanent residence? Because the TFWP reduces these workers to stop-gap instruments, this line of questioning would help clarify how businesses value their contribution.

The Impact on the Everyday Lives of Migrant Workers

28 “Low-waged” temporary foreign workers are mostly restricted from gaining permanent status and are confined, as French philosopher Guillaume le Blanc would say, to a paradoxical liminal space at the threshold of the community: “nor inside, nor outside, but at the same time inside and outside” (le Blanc 19). Using a critical ethnography, the goal of further study should be to “produce historically, politically, and personally situated accounts, descriptions, interpretations, and representations” (Tedlock 165) of how these people go about their everyday lives as temporary foreign workers living in this liminal condition. Such a methodology would acquire primary data by engaging in casual conversations with workers to find out how they understand and rationalize their situation as temporary workers, but also how they feel about their experience as a whole. More information is needed about their everyday rituals, habits, and interactions, at work and in the community at large, as these migrants move slowly into the community and engage with the local population in spaces such as Tim Hortons, the church, the grocery store, and the soccer field.7 We must learn more, too, about their personal views of how the practice of “circular migration” has affected their lives here and their lives back at home where families are waiting. The goal of this methodology is to establish authentic intersubjective links with these workers, which requires from the part of the ethnographer “habits of being in the world, of being able to talk and listen to people, and being able to write—habits that are beyond method” (Goodall 10).

29 Other considerations must be clarified: the reasons for coming to work in the fish and seafood processing plants of Cap-Pelé (whether gaining higher wages to help themselves and their families back home, or settling permanently in New Brunswick or somewhere else in Canada). Was this specific industry and location, we need to know, a choice, or was it determined by some other means? With respect to the mobility restriction imposed upon them, and the related disciplinary retention power given to their employer, it would also be interesting to learn whether temporary workers feel any “pressure to maximize the now,” as Anderson suggests, and how they understand their larger place in the local economic context. Lastly, as temporary residents working in a small rural community where access to settlement and integration services is limited, we need to be able to assess the adaptation and integration challenges that temporary workers face.

The Village of Cap-Pelé: The Community’s Perspective

30 It is also very important to assess the impact that the arrival of temporary foreign workers has on the rural communities that welcome them. Cap-Pelé makes an interesting case study. The village counted a mere 2,256 inhabitants in 2011 (Canada, “Cap-Pelé”), yet welcomed at least 450 migrant workers to labour in some of its fish and seafood processing plants in the summer of 2013.8 This addition to the population has tangible implications for its cultural fabric. For example, most migrants working in this francophone village do not speak French, and so the program has been criticized for not considering francophone minority issues (Richard “Contre-courant”). What has the impact of this criticism been on the workers and the village? Such questions point to the importance of engaging in conversations with local stakeholders (municipal services, businesses, non-profit organizations, and residents) to assess their experiences, challenges, and ideas in adapting to this new diversity—with the goal of increasing efforts to make temporary residents feel at home in Cap-Pelé. There is also, of course, the need to inquire into the locally held views of the impact that the TFWP has had on the community as a whole by looking at Cap-Pelé’s everyday rituals and habits. Such efforts will discern changes in social environments, and reveal things that planners, policy-makers, employers, and communities need to know going forward.

Conclusion

31 This paper started by noting that rural businesses in New Brunswick have increasingly turned to the TFWP to address their labour needs, leaving the federal government perplexed as it believes that areas with high unemployment rates should not have to recruit abroad. With youth outmigration and an aging population, New Brunswick’s situation proves to be more complex, and some of the province’s rural businesses have had no choice but to turn to the TFWP to be sustainable. The important point is that the program, by giving retention power to businesses, is useful in helping them alleviate shortages, but at the same time leaves temporary foreign workers in a precarious legal status.

32 The projective research that this note calls for seeks to understand these vulnerabilities from individual and community perspectives. In particular, we believe that ethnographic research would give way to a “reversal of perspectives” (Beaud and Weber 11) by considering the effects and realities produced by the TFWP. In a provincial context fraught with labour and economic issues, an ethnographic case study of the village of Cap-Pelé would not only collect data and stories to better inform stakeholders about these inherent vulnerabilities, but offer a more accurate and visceral account of the everyday anxieties, frustrations, hopes, and dreams of migrant workers who have been coming to New Brunswick, of the employers who hire them, and of the communities that welcome them.

Eric Thomas is an analyst for the Canadian Institute for Research on Public Policy and Public Administration located at the Université de Moncton.

Chedly Belkhodja is professor and principal of the School of Community and Public Affairs at Concordia University.