Articles

A Near Golden Age:

The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in New Brunswick, 1940-1949

Abstract

This history of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in the 1940s in New Brunswick adds to a growing body of literature that challenges the misperception that the CCF scarcely existed east of Ontario. However, in spite of a host of historical (and later) social conditions that called out for the CCF, the 1940s was the only decade when the movement showed considerable promise in New Brunswick. This article will suggest that the failure of the movement to gain permanent traction was attributable to several factors: the political strength of the Liberal political machinery and Premier John B. McNair; anti-labour sentiments and the anti-CCF campaign in the media; organizational challenges within the party; social and economic conditions within the province; and the divergent agenda of Francophone and Anglophone New Brunswickers.

Résumé

Cette histoire de la Fédération du Commonwealth coopératif (FCC) dans les années 1940 au Nouveau-Brunswick s’ajoute aux nombreux écrits qui dénoncent la fausse perception que la FCC a rarement existé à l’est de l’Ontario. Toutefois, malgré une foule de conditions historiques, et plus tard sociales, qui ont favorisé la FCC, les années 1940 ont été la seule décennie pendant laquelle le mouvement a suscité un espoir considérable au Nouveau-Brunswick. Cet article démontrera que la faillite du mouvement à atteindre une croissance permanente était attribuable à plusieurs facteurs : la force de la machine politique du Parti libéral et du premier ministre John B. McNair, le sentiment antitravailliste et la campagne anti-FCC dans les médias, les défis organisationnels au sein du parti, les conditions socioéconomiques dans la province et les priorités divergentes des francophones et des anglophones du Nouveau-Brunswick.

Introduction

1 In 1932, in the midst of the Depression and after having experienced war and labour unrest, many Canadians were receptive to the vision of a new political, economic, and social order. The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) offered such a vision. The growth of this movement can be attributed to social democratic expectations after the war coupled with the successful militancy of labour. The inaugural convention of the League of Social Reconstruction (LSR) was held in January 1932 in Toronto. The LSR was not a political party but rather acted as a research group and “brain trust” for the CCF,1 providing an educative role through forums and study groups for its members. J.S. Woodsworth was selected as the group’s first honorary president.2 Its democratic socialism mirrored the form adopted in the British and Swedish systems. The word “democratic” was deliberately chosen to “distinguish the LSR beliefs from Marxian socialism on the one hand and ‘national socialism’ or Nazism on the other.” Its prime purpose was to “provide a thorough analysis of the capitalist system and to define the social goal.”3 The LSR took over publication of the faltering Canadian Forum in 1934 and the magazine served as a mouthpiece for its views.4 In May 1932, J.S. Woodsworth and the Ginger Group, a handful of parliamentarians mostly from western Canada who wished to revitalize the progressive movement, conceived the creation of a new Commonwealth Party that embodied democratic socialist ideals. The movement appealed to people from many different backgrounds and included farmers, youth, women, intellectuals, peace activists, and labour moderates.

2 Most of the existing literature about the CCF focuses on its history in central and western Canada.5 However, various facets of the socialist and labour movements in New Brunswick and the Maritime provinces have been brought to light.6 It is worth noting that at its peak in 1910 Maritime socialists represented 10 percent of the overall membership of the Socialist Party of Canada (SPC) at a time when the region comprised only 13 percent of the Canadian population.7 In New Brunswick, CCF ideas were most readily understood and adopted by farmers, unionists, members of the cooperative movement, and by a small cadre of intellectuals. Attracting 98 delegates, the New Brunswick branch of the CCF came into being on 23 June 1933 at a meeting convened by the Federation of Labour for the purpose of organizing a section of the party. The first CCF candidate ran in the provincial election in 1939 and the last in 1952. After 1952 a gap in CCF political representation existed until 1967, when three candidates ran for its successor, the NDP, in Northumberland County.

3 It is significant that the CCF achieved support in New Brunswick in the 1940s when the hegemonic forces were decidedly anti-labour and anti-CCF. In particular, the party faced a formidable opponent in John Babbitt McNair who served as Liberal premier from 1940 to 1952. Moreover, it was daunting to challenge entrenched power structures at a time when a worker risked being fired for publicly showing interest in a union or the CCF. The party’s lack of access to power structures limited its efficacy because it lacked information regarding the political and economic affairs of the province. As was the case on the national scene, CCF ideas were misrepresented in the mainstream media, which fomented the fear among potential voters that the CCF supported aspects of the Soviet system. However, the party lacked the funds to rebut such misperceptions.

4 The CCF party faced other challenges. Since it was a party funded exclusively by citizens, it lacked funds. It also lacked trained and capable organizers even when funds were available to hire them. As well, although the party declared that it would not entertain financial contributions from big business (leaving it free to advance the will of the people), this stance hampered its ability to spread the message of democratic socialism. Further, the CCF message likely did not reach most New Brunswickers, who lacked the funds to subscribe to CCF publications such as True Democracy, Maritime Commonwealth, or the LSR magazine Canadian Forum. The high rate of illiteracy in the province also presented a barrier to getting the CCF message out through the print media. At campaign time all parties were allowed some degree of free airtime through CBC’s “Provincial Affairs,” but radio time beyond that cost money.

5 Nevertheless, many New Brunswickers were buoyed by CCF success in other parts of Canada. The first Gallop poll conducted in 1943 in Canada “placed support for the CCF with its promise of social security, 1 percentage point ahead of both parties” (Miller 321), forcing the ruling federal Liberals to veer to the left as a result. Gerald Caplan (1973 110) speculated that had a federal election been called in September 1943, the CCF would have claimed 29 percent of the vote while the Liberals and Progressive Conservatives would each have received 28 percent of the vote respectively.

6 By 1943 the CCF served as the official opposition in Ontario, British Columbia, and Manitoba, and Tommy Douglas was elected as the first CCF premier of Saskatchewan in 1943. Caplan (1973) commented on the regional variations, concluding that “east of Ontario the CCF remained a joke.”8 Challenging the accuracy of Caplan’s remark was the fact that the CCF was gaining popularity in New Brunswick, capturing 68,248 votes in the 1944 provincial election, which was more than 13 percent of the total votes cast. Twenty-five percent of the votes cast were in Moncton and Saint John. The party did show considerable promise in this province and region, then, despite the scepticism of many CCF organizers at the national level. The party’s appeal in Moncton, Saint John, and Madawaska County was largely linked to specific local conditions and people in those communities. As well, in Fredericton there was a particularly strong core of CCFers in the 1940s who met at the University of New Brunswick.

7 This paper contributes to a history of the CCF in New Brunswick by focusing on the 1940s, the decade when the party enjoyed its greatest electoral success. While Ian McKay (1984 75) and, to a lesser extent, Ken Wilbur (1991 150) acknowledged the CCF’s often limited but overlooked success, this work provides a more detailed exploration of its heyday and some of its challenges.

The CCF Moment in New Brunswick

8 The New Brunswick branch of the CCF came into being at a meeting convened by the Federation of Labour on 23 June 1933 in Moncton. The intent was to organize a New Brunswick section of the CCF, so moved by A.W. Jamieson, seconded by W.J. Richard, and passing by a vote of 21 to 9. J.S. Woodsworth was the keynote speaker to a crowd of more than 1,000 people at the Moncton Stadium. Officers were appointed, most notably H.H. Stuart (1873-1952), one of the founders of the Fredericton Socialist League in 1902. He was made the first honorary president of the New Brunswick CCF. Stuart retained this title until his death in 1952, thus providing a unifying link to earlier socialist traditions. Following the June meeting, members of Moncton Local 594 of the International Association of Machinists brought their enthusiasm for the CCF to the 49 th annual meeting of the Trades and Labour Congress of Canada (TLC) held on 23 September 1933. The hope was to secure labour’s endorsement for the CCF on a large scale (Marsh 89n52). After much debate, however, TLC members chose not to contravene their policy established in 1923 of not affiliating with a political party. This had negative consequences for the fledging party.

9 In Make This Your Canada: A Review of CCF History and Policy, David Lewis and Frank Scott (1943) described how democracy in the CCF reflected a movement growing from people’s response to the breakdown of capitalism witnessed in the Depression. Membership was open to anyone who agreed with the philosophy and programme of the CCF, and the movement relied heavily upon volunteers to educate others and spread the CCF message of democratic socialism. Each province represented a section of the movement and possessed the autonomy to adopt the organizational structure and form alliances best suited to specific conditions. The movement stipulated that a provincial convention, comprised of delegates from local organizations and affiliates, be held each year where local issues were discussed and elections of provincial officers conducted. The provincial leader was also chosen at the annual convention. Each province chose three members to sit on the National Council, which met twice a year to ensure representation from rank and file members.

10 The CCF provincial council consisted of twelve members who met every two months. Although mostly members and their spouses attended, anyone who wanted to join in could do so. Four additional layers of organization carried on educational work, even in non-election years. They were the constituency committee, which met once every three months and selected candidates; the poll committees; the CCF clubs; and various study groups. The clubs required a minimum of six members and represented the grassroots of the party. Members were also able to join the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation Youth Movement (CCFYM) to ensure that youth were represented.

11 When the CCF was founded, conditions in New Brunswick were ripe for the platform proposed by the party. Indeed, the northern counties of the province were among the most economically impoverished in all of Canada; at the end of the decade, the Rowell-Sirois Commission Report (1939) identified the Maritime region as the most chronically depressed in Canada, partly because there were too few workers to provide a robust tax base (Miller 332). Additionally, the labour movement in New Brunswick was less advanced than most other provinces in Canada. Although politicians made efforts to be seen as “friends of labour,” labour regulations in the province favoured employers and did little to support the rights of workers. In these respects there would seem to have been a natural constituency for the CCF platform, which included such measures as the immediate establishment of mothers’ and widows’ allowances, eligibility for benefits through Workmen’s Compensation, and demands for provincial marketing boards (i.e., potato).

12 In spite of these conditions, however, the CCF grew slowly in the 1930s. When the decade came to a close, only Joseph C. Arrowsmith had run for the CCF. Since 1 November 1937 he had served as Maritime organizer and literature agent for the party.9 Arrowsmith had served as the provincial secretary in 1937 and was succeeded by James Fritch in 1938.10 In Saint John in the provincial election on 20 November 1939,11 Arrowsmith received 712 votes, a small percentage compared to his rivals. Only one other candidate, Wilfred Verret, ran for a non-traditional party in 1939 and that was as an Independent-Labor candidate in Madawaska County. In the 1940 federal election, James E. Fritch representing the CCF for Saint John-Albert, won 761 votes, which constituted just over 2 percent of the total votes cast (http://www.parl.gc.ca).

13 In the run-up to the 1944 provincial election, the national office of the CCF was aware that the CCF was struggling in New Brunswick and sent George Castleden (MP for Yorkton, Saskatchewan) to assist with party organization. In his final report to the national executive, he concluded that New Brunswick people were “almost completely ignorant of the policies, principles, program or organization of the CCF.”12 He did acknowledge that the labour organizations in the pulp and paper industries and the railways were well informed, and that the Moncton branch accurately reflected the views of the CCF. He also added that the CCF platform was best understood on the east coast and north shore, areas where cooperatives and credit unions had mushroomed. He reported that in the northwest part of the province, which was mostly French speaking and Roman Catholic, there existed a “noticeable readiness of the Church to place no obstacles in the way of the people who wish to take part in CCF activities.” Castleden observed that New Brunswick generally lacked educated, experienced workers as well as direction. He recommended that Harry E. Marmen from Edmundston be sent to Madawaska, Restigouche, Victoria, Gloucester, Northumberland, Kent, and Westmorland counties to assist with organizing the French-speaking population. Castleden also suggested a formal liaison be established between the CCF and the labour movement, which represented approximately 4,000 workers.13 He thought that this liaison could be expedited by a visit from Clarie Gillis, CCF MP from Cape Breton South. Castleden concluded his report on an encouraging note by stating “if the educational program is maintained and the leadership in New Brunswick is developed, I am confident that this Province will become a banner CCF Province. Its importance to the movement has been underestimated.”14

14 Similar to the situation at the national level, the CCF enjoyed its most promising decade in New Brunswick in the 1940s. According to McKay (1984), “In July 1944, there were seventy-five clubs; one month later there were eighty-seven. In November 1944, there were fourteen clubs in York county and two in Sunbury. The extent to which the CCF had penetrated the rural areas in 1944 and 1945 is striking” (75). The Humphrey’s CCF club in Moncton was typical, building its own hall to encourage the “mental, spiritual and physical development of all who wished to use it” (76).

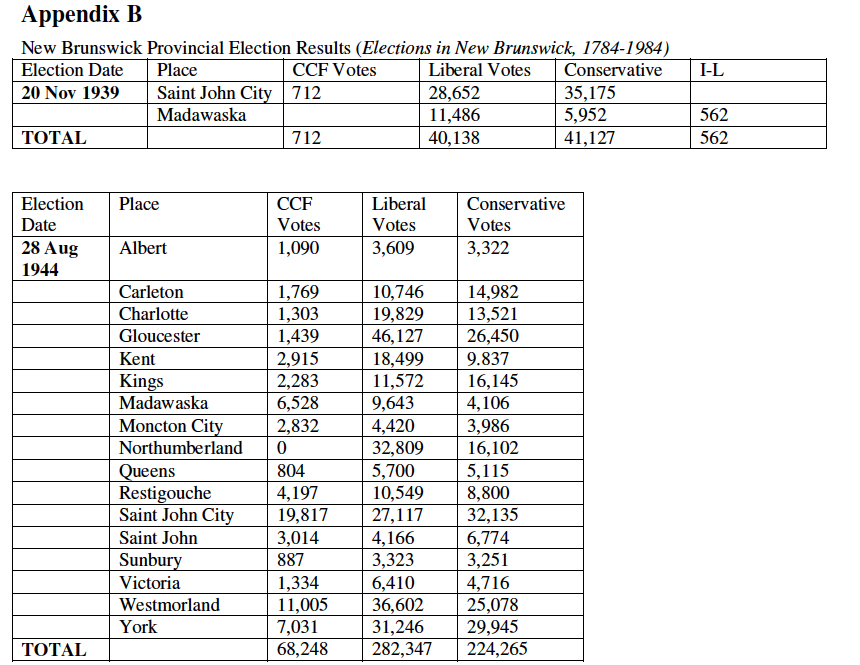

15 Forty-one candidates ran for the CCF in the 1944 provincial election with approximately nine coming from the labour movement. In the 6 September 1944 issue of Maritime Commonwealth Grace MacInnis, daughter of J.S. Woodsworth, announced that the CCF captured 50,000 votes in the general election in New Brunswick;15 however, the actual number of votes was 68,248, representing more than 13 percent of the total votes in the province. Saint John and Moncton ridings accounted for 25 percent of the vote (see Appendix B). The optimism was high due to the rapid progression of the movement and growing support from labour within such a short period of time. Early in November of that year it was proudly announced in the Maritime Commonwealth that the Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL) had declared the CCF a labour party.16

16 However, in spite of the substantial advances in 1944, no CCF candidates were elected. In his election postmortem, Albert E. King, provincial secretary of the New Brunswick CCF,17 wrote to national secretary David Lewis outlining what he perceived as some of the successes and challenges. King was surprised that the CCF had received so many votes in Madawaska county, where Harry Marmen and Daniel Laboissonnière challenged the Liberals (and where the Conservative candidates lost their deposits).18 In Kent county the CCF did worse than expected,19 yet that county had the largest number of CCF clubs and members than in any other constituency in the province. The Saint John group had been the most active and made a strong showing, although King thought there would have been better results if their organization had been as well developed as those of the traditional parties. King referred to internal friction among otherwise very enthusiastic working members in Albert, King, and Queens counties.

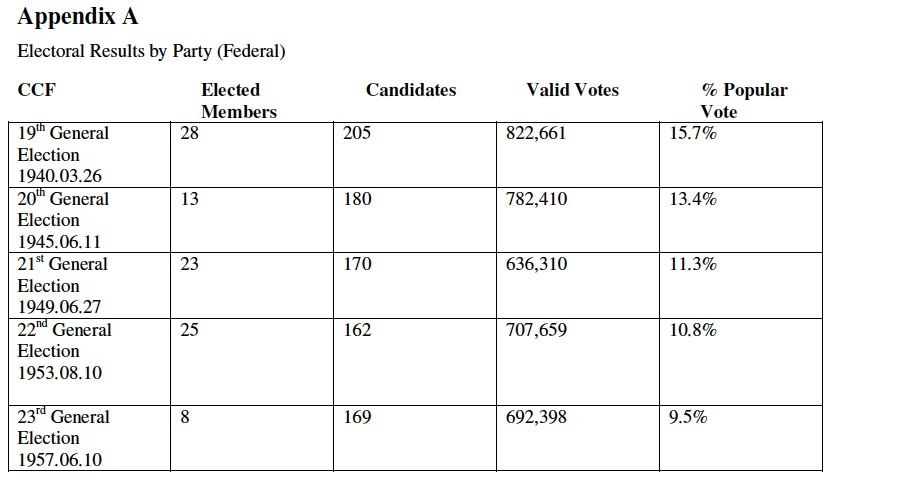

17 In Sunbury county the CCF candidate, Frank G. Vandenbore, a Belgian miner and president of United Mine Workers Local #7409 (Minto), garnered 439 votes. One major challenge that King identified was the difficulty in securing skilled organizers even though money was available to hire them in Victoria-Carleton and Westmorland counties.20 Nevertheless, the election was successful in that it evoked substantial optimism, one aspect of which was that CCF clubs were subsequently formed in New Maryland, Fredericton, McAdam, Richibucto Village, and the suburbs of Saint John. The CCF council for women was also reorganized. Mrs. J.F. Robertson was elected president, and Mrs. Williamson and Mrs. Marion Buchanon were elected to executive positions.21

18 A biting analysis of post-election results in 1944, presumably written by Frank Park, concluded that CCF candidates garnered significant votes in only three cities: Saint John, Moncton, and Edmundston. It also added that, while most of the support lay in rural areas, it was only in one poll in Bathurst where the CCF challenged the Tories who were far behind the Liberals. He noted that the Minto miners in Queens and Sunbury did not give their votes to the CCF. In his estimation this made “the running of 41 candidates looks like an irresponsible political adventure.” Park highlighted the imperative of the CCF to evaluate the programs of the Liberals in order to be able to “put forward precise, concrete, constructive proposals of their own.” For example, he noted that since 1937 the McNair government had moved toward full co-operation with the Dominion government “in low-cost housing projects, in National Health Insurance and in rehabilitation generally,” positioning the Liberals in opposition with Tories in Quebec and Ontario, who were against such cooperation. Further, McNair promised to retain the Dominion Labour code after the war and the Liberals’ ambitious tidal power project promised to advance local industries. Park critiqued the CCF 12- point platform for being vague and for failing to acknowledge that the Dominion Labour code had already been implemented in all industries in New Brunswick. He further criticized the platform for being essentially reformist in nature, citing Point 5 – “the full development of provincial resources under public ownership for the benefit of the people of N.B.; to include complete publicly owned electric services, oil and gas fields and other public utilities, together with vigorous development of our tourist industry” – as the only socialist measure articulated. While Park saw merit in the CCF he urged the party to prevent a Tory coalition at all costs even if they had to join with Liberals or members of the Labour Progressive Party (LPP), the renamed Communist Party. He even suggested that the CCF helped to elect the Liberals by “splitting the anti-government vote” (4). He concluded by saying that the optimism shown by CCF party members in 1944 was naïve.22

19 There were other mitigating factors that Frank Park perhaps failed to consider. For one, the threat of losing one’s job because of a real or imagined association with the CCF was a common one experienced across Canada (Boyko 40). M.J. Coldwell, the national leader of the CCF from 1942 to 1958, had himself been dismissed from his position as a school principal by the Regina School Board because he ran as a provincial candidate for the CCF in 1934. Although he was officially reinstated due to popular support by the teachers, he never returned to teaching. Even late in 1949 it was reported that junior professors at the University of New Brunswick were “in danger of persecution if they became too active” in providing education in socialism.23 A CCF party leader revealed that the message to stay away from the CCF had clearly reached civil servants through his observation that, “The night is not dark enough for people to come -especially in Fredericton where many people have government jobs” (Thorburn 103). Fear of the CCF growing in popularity prompted nervous businessmen and boards of trade in New Brunswick to reassert their hegemony by coordinating their attack on socialism, which included strongly warning workers about the “evils of socialism and of the dangers to their jobs should a CCF government take power.” The CCF was broadly accused of being “too close to the Catholic Church” or, conversely, “depicted as a party dominated by Protestants” (Miller 341-42).

20 The media employed various tactics to discredit the CCF at a time when the party lacked the financial resources to get its basic message to the population, much less counter the anti-CCF propaganda. The party leader, Jim Mugridge, a member of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) from Saint John, was appointed chairman of the election committee in April 1944. He complained to David Lewis about T.F. Drummie, the editor of both Saint John newspapers, who refused to print anything related to the CCF, including paid advertising. Drummie’s recalcitrance and subsequent response to his complaint was, “That’s not politics; we are doing a public service. You fellows are a public menace” (Boyko 43). After some arguing Drummie did agree to print paid advertisements, but he reserved the right to determine which ones to print. Clearly it was crucial for the CCF to publish its own newspapers across the country in order to get its message out. Troubling too was the initial difficultly of finding someone to print the CCF provincial newspaper, NB Commonwealth, in 1944.24

21 Major newspapers in New Brunswick created the impression that aspects of the CCF platform were more radical than they were. A 23 August 1944 editorial in the Saint John Telegraph Journal referred to M.J. Coldwell as “the leader of the Socialist Party in Canada known as the CCF.” Railing against Coldwell’s alleged platform of conscripting wealth, the editorial opined that the party’s intent was

22 This was followed the next day by an editorial about CCF confiscations of bank accounts, which would have frightened thousands of citizens. Reporting on the last weeks of the 1944 provincial election campaign in Maritime Commonwealth, Ralph Olive told of the “foul blows” made to the CCF. He may have been referring to an editorial in the Telegraph Journal, which referred to Coldwell as a transplanted Englishman, seemingly in attempts to alienate French-speaking New Brunswickers. The following day an editorial alleged the CCF’s intention to confiscate bank accounts. On the last day before the election Olive reported that a “scurrilous” anonymous pamphlet with no union print shop label appeared on Saint John streets titled “What Do You Know of the CCF?.”26 There was no signature on this pamphlet; however, Olive reported that the pamphlet had been traced and so it would be possible to prosecute the authors.

23 Dana Mullen (provincial secretary from 1948 to 1949) referred to the oppressive atmosphere concerning the CCF in New Brunswick when she arrived in 1946 at the age of twenty-one. She described how in those years “there were still communities in New Brunswick owned by a single company, where it was recognized that you could lose your job, even as a school teacher at a local school, if you dared to promote a union or support the CCF.”27 Harry Marmen, for example, was discharged from his position as electrical superintendent for Edmundston in June 1946.28 Marmen had been a CCF candidate in the 1944 provincial election representing Restigouche-Madawaska. He reported that in exchange for his resignation from the Civic Employees Union, the mayor told him that the town would sign a collective bargaining contract with the union. Marmen refused to resign. The town council offered to reinstate him on 5 June, without back pay, but he refused that, too, and so was formally discharged on 8 June 1946. More than 300 citizens demanded his reinstatement or the resignation of the town council, and unionized civic employees threatened to strike.29 His supporters were ultimately vindicated when Marmen was elected mayor of Edmundston on 20 January 1948 by “one of the largest votes ever deposited[,] which means that the labouring man got out in numbers.”30 The experience of Harry Marmen demonstrated that under the right conditions there was indeed the potential for grassroots CCF support in the province. That Edmundston was a highly unionized town because of the Fraser Company mill, and Marmen a respected member of the community, were no doubt significant factors in his electoral success.

24 John Babbitt McNair, the elected Liberal premier of the province from 1940 to 1952, represented a significant barrier to the electoral success of the CCF. In political circles he was a known commodity, having served as president of the New Brunswick Liberal Association from 1932 to 1940. In 1935 he was elected to the Legislative Assembly as a representative for York County. The Liberals were the stronger of the two traditional parties during this time, appealing to both Anglophone and Francophone New Brunswickers. Allen Seager (1980) described McNair as an anti-labour “hardliner” (18), likening him to “violent opposers of communism and industrial unionism” (118) such as premiers Mitchell Hepburn (1934-42) in Ontario and Maurice Duplessis (1936-39; 1944-59) in Quebec. Both traditional parties vied to be seen as “friends of labour” even if, as Mackenzie King did on the national level, McNair resisted unions until it became politically unwise. An example of this tentativeness was McNair’s introduction of the Labour Relations Act at the end of the war in 1945, which more or less promised to continue the long-delayed 1944 wartime federal reforms in labour relations. It was one of a number of achievements touted by the Liberals in their 1944 platform that were co-opted from the political left and popular with voters.31

25 Despite McNair’s popularity and strength, CCF members were optimistic. In his welcoming address to the CCF provincial convention held in Fredericton in July 1945, H.H. Stuart spoke of the steady progress he had witnessed in the socialist movement, currently reflected in the CCF party (see Appendix A). Clarie Gillis, CCF representative in the House of Commons from Cape Breton South, gave a similar motivational speech urging CCF members to “go on an all-out drive” to organize for the CCF.32 Gillis did not mince words in speaking to some of the perennial challenges. Indeed, the CCF lacked crucial information about the political and economic affairs of the province. Its members also lacked training in public speaking and leadership, and they had yet to work out a cooperative program with labour organizations.

26 At its 1945 convention, the Moncton group was particularly concerned with the lack of adequate and affordable housing, especially for low-income persons and returning veterans. Other concerns were that the CCF pledge itself to encouraging and supporting the cooperative movement in New Brunswick; that it found cooperative health services so that every citizen could receive adequate medical attention; and that the production of electric power become a public enterprise. Early in 1946 the Moncton CCF club passed a resolution protesting the condition that many returned servicemen were denied a municipal vote because they could not afford to buy property or even pay rental tax on an apartment.33

27 It is worth noting the public role of two women who attended the provincial convention. Hilde Falkjar (1902-1969) would serve as the vice-president of the CCF provincial council from August 1946 until May 1947 – and at a time when provincial councils were heavily dominated by men (qtd. in Melnyk 93). Gladys West (1906-1962) served as secretary-treasurer of the King Mine club in Chipman in 1945 while her husband, George West, served as president.34 At the age of forty-two, Gladys West would go on to run in the 1948 provincial election as a CCF candidate for Queens County, the first woman to run for the CCF in New Brunswick.35 West was an outspoken advocate for the families who had worked for the King Mining Company in Minto, a company she believed dominated its workers.

28 Grace MacInnis explained how it was issues such as this that motivated West to move beyond her shyness to seek public office.36 Shyness, in fact, was often attributed to women running for the CCF party. For example, in 1934 The Commonwealth referred to Mildred Fahrni as “inclined to be shy” (Melnyk 142) and in a 17 January1945 issue of Maritime Commonwealth, Beatrice Coates Trew (1897-1976), an elected member of the Saskatchewan Legislative Assembly originally from Coates Mills, New Brunswick, “admits to being shy herself.” It is quite likely that West was not shy at all but that she and other publicly political women had to tolerate being attributed this trait in order to appear less threatening to voters.

29 There were varied opinions on the role of women in the CFF in New Brunswick and on their potential for electoral success. Dana Mullen was born in 1925 and grew up in a suburb of Buffalo, New York, arriving in New Brunswick at the age of twenty-one. Active in the CCF movement from 1946 until 1949, she did not believe that gender was a barrier in the CCF (Personal interview with Mullen 2003). Gladys West agreed with her, stating that it was “not at all unusual for a woman to be a candidate for the CCF.”37 However, some women in leadership positions, such as Elsa Harrison, secretary of the Kennebecasis branch of the CCF, were not optimistic about the prospects for women candidates. When asked by Mullen if she had thought of running as a candidate in the 1948 provincial election, Harrison replied: “Do you think a woman has a chance in New Brunswick? I fear that great and startling changes in their outlook must occur before we achieve such letters as MP or MLA after the name of a female of the species in New Brunswick.”38 The fact that relatively few women took out CCF memberships, and that a separate women’s committee was not even suggested until 1949, may be taken as indications of a low level of involvement in the party. However, both women and men tended to join CCF clubs rather than take out formal memberships, which suggests that there was more gender integration within the movement in New Brunswick than elsewhere. The presence of women as club members reflected the community-based nature of the party, which was financed and run by citizens and was consistent with a “service-based conception of what is involved in community life.”39

30 The CCF had a limited presence on the campus of the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton. According to Mullen (2003), there were two defining events for left-wing UNB students. The first was the 1944 election of the CCF premier in Saskatchewan, Tommy Douglas, and the second was the post-war election of the Labour Party in Britain in 1945. By the spring of 1946 there were twelve very active students who were interested in the CCF. The group tried to gain Cooperative Commonwealth University Federation (CCUF) status for the CCF; however, they were opposed by a majority of the student body at UNB who seemed unsupportive of an alternative party.40 Vernon Mullen and the other UNB students interested in the CCF met on a regular basis off-campus in a room above an old printing shop where True Democracy, the “Watchdog of the People” (the official CCF newspaper) waspublished twice monthly at the Wolfe Press on Brunswick Street. They also declared themselves “the unofficial CCFU group at UNB.”41

31 Vernon Mullen, Dana’s husband, had come to UNB as a student in the fall of 1945 after being discharged from the Royal Canadian Air Force (he had been a prisoner of war). Most of the 350 students in his cohort were war veterans, and they were joined in January 1946 by an additional 175 men and women who had been discharged from the forces. This group of veterans outnumbered the younger students in the three upper classes.42 Dana Mullen’s gradual politicization was forged by writing articles for True Democracy and working with Vernon on the lay-out. At the same time Vernon Mullen was Editor-in-Chief for The Brunswickan, a student weekly of about eight pages in length.

32 In September 1947, Vernon Mullen was campaign manager for future UNB history professor Murray Young in a federal by-election against Milton Gregg, the Liberal candidate and president of UNB. A former fish market served as the campaign office (V. Mullen 32). Young was a war veteran, son of a local farmer, and a UNB student. Although there was little chance that the CCF candidate would win, Young garnered 3,514 votes or 14.72 percent of the total, a very respectable vote for the CCF.43 Dana Mullen recalled that the campaign was “well-fought” and provided the opportunity for the local CCF members to meet more experienced leaders such as David Lewis, Sandy Nicholson, Clarie Gillis, and Grace MacInnis.44 Although the national leaders were impressed with their youthful enthusiasm, they were initially uncertain of the local group’s politics. Mullen recalled in the same interview that “Grace MacInnis questioned me quite closely about how I had been drawn to socialism. I think she wanted to make sure that I wasn’t bringing in some kind of Trotskyite influence.” Apparently reassured, MacInnis described Murray Young’s second place finish as “the CCF victory in York-Sunbury” and praised Vernon and Dana Mullen and their associates Fred and Sarah Hartwick and Harold Hatheway.

33 The experience gained and the connections made in the 1947 by-election proved valuable in organizing for the 1948 provincial election. In May 1948 well-known labour man Lawrence “Laurie” Bright succeeded Dan MacDonald as president of the provincial CCF. 45 When Dana Mullen agreed to take on the position of provincial secretary, succeeding Lloyd Wilson from Moncton, she did so on a part-time basis for the first month and then continued full-time with a salary of $1000 per year.46 The funds ran out and she continued to work in the position without pay. The provincial office was moved to Fredericton at that time because it seemed logical to have it located in the capital city.

34 Between May and June 1948 frequent written communication occurred between Dana Mullen and David Lewis, particularly with respect to how to make the best use of limited resources. She also relied on Fred Young’s wisdom and kindly nature. On 3 November 1946 Young was voted Maritime director of organizing for the CCF, operating out of Halifax. He developed friendships with the Fredericton group, particularly Dana and Vernon Mullen, Harold Hatheway, Murray Young, and Linden Peebles. One thing Young and Mullen worked on was recruiting organizational help. In 1948 three UNB students were hired to help organize regions for the 1948 general election. Harold Hatheway was assigned to Kent county, Murray Young to York-Sunbury, and Arthur Parks to Royal.

35 The 1948 provincial election, which resulted in a resounding victory for the Liberal McNair government, produced mixed results for the CCF. Dana Mullen wrote to Lewis on 29 June 1948 to offer a post-election analysis of the results. She reported that it was “perfectly clear to us that the people of New Brunswick were ready for the CCF but we were not ready for them. We were able to place only twenty candidates in the field where there should have been fifty-two.”47 She also allowed that the CCF had lost some ground with labour groups in Saint John since the 1944 election. She acknowledged that because they focused their efforts in only a few counties the overall results were discouraging. Ironically, there were no candidates in counties where the CCF had gained the most votes in the 1944 election, such as in Madawaska, where Marmen and Laboissonnière had previously run. No CCF candidate ran in Madawaska in 1948, but three ran as independents (one of them Marmen) and three ran for the Social Credit Party.48 Restigouche County ran one Social Credit candidate, but none from the CCF. In all, twenty candidates ran for the CCF and five for Social Credit. The CCF would have received considerable support if Marmen had run and had the party been sufficiently organized to draw out the CCF votes that they believed existed.

36 On a more positive note, Mullen could report that those voting CCF represented solid support, not protest or “swing” votes. Lloyd Wilson referred to the York-Sunbury by-elections, however, as “one of the most outstanding political events of the year” because the result “proved, beyond a doubt, the rapid growth of the CCF and confirms our belief that the foundation of a great socialist political party has been laid.”49

37 No CCF candidates appeared in the northern counties for the 1949 federal election and Mullen worked to no avail to get a candidate north of Woodstock for Victoria-Carleton.50 Although John McNair ran in Sunbury county, he was born in Andover, which might help explain the inability to find a CCF candidate to run there. In July 1949 Mullen confided the following to Fred Young:

38 An interesting footnote about the CCF in New Brunswick during this period comes from Carlisle Hanson. By December 1948, Hanson had earned a BA from UNB, taken graduate courses at McGill, attended the University of London as a Beaverbrook Overseas Scholar, and was studying law at the UNB Law School in Saint John. He had been active in the provincial council in York county since 1945, was appointed research director of the party in May 1946, and, while in this position, represented the CCF at a national level on various occasions. He had also served as president of the CCF club in Fredericton. He resigned from his position as research director in the party in September 1949, citing his passionate opposition to the party’s support of the Atlantic Pact that he witnessed at the provincial CCF convention in Moncton in September 1949. For Hanson, support for the Atlantic Pact, taken to stem possible Russian aggression, meant having to rely on American protection while undermining Canada’s connection with the commonwealth.52 He did not get the support that he wanted for the resolution and so quite the party altogether, sensing conflicts with other active CCF organizers.

39 After his exit he noted that, since January 1949, “the CCF in New Brunswick had fallen under the control of three people: Dana Mullen, Secretary, Harold Hatheway, Treasurer and Murray Young, Chairman of the Finance Committee.”53 Perhaps his comments reflected his discomfort with the close alliance between the three, who were youthful, intelligent, energetic, and strongly motivated by idealism. If it weren’t for Dana Mullen’s untiring work – visiting clubs, keeping members informed and motivated, securing candidates, and ensuring they had CCF materials from the Maritime office to inform their radio broadcasts and press releases – the party would scarcely have existed. She showed exceptional skill and maturity for a young woman in her early-twenties, as did her university student colleagues. Hiring Dana Mullen in April 1948, then, was possibly the best $1,000 the party had spent. However, despite this fruitful decade of organization and advancement, the 1940s was the only decade when the CCF in New Brunswick showed promise.

Conclusion

40 The CCF ran its first provincial candidate in the 1939 election and its last candidates in 1952. Momentum for the party was gained and lost in the 1940s. The failure of the CCF to flourish in New Brunswick is attributable to a number of factors, the most important being the strength of the McNair Liberals. Compared to the CCF, the Liberal Party was a familiar and known commodity. McNair held political sway at a time when the CCF was mobilized to make its greatest inroads in the province, thwarting advancements by organized labour. As premier, he implemented various reforms that represented concessions to the unemployed, civil servants, mothers, older adults, and labour, as well as building roads and electrifying the province. In other words, McNair possessed the power and the party machinery to implement the programs that the CCF was largely responsible for introducing. McNair’s achievements were underwritten by the rise of the positivist state in Canada as both the economic planning of the war years and the beginnings of federal regional development funding substantially increased the ability of the provincial government to build much needed infrastructure and promote social and economic advancement. It was a powerful formula for electoral success that rendered difficult the building of a viable third party in New Brunswick.

41 A less than receptive mainstream media also worked against the CCF in New Brunswick. Representatives of business were able to exert considerable control over the media, and it was in their interest to do everything they could to stop any socialist movement in its tracks. The major newspapers in the province blocked CCF access to their forums by refusing to print editorials and by exercising their prerogative to determine which paid political advertisements would be printed. The print media made the CCF appear more radical than it was by intimating that the CCF had something in common with the economic platform of the Soviet Union. Moreover, individuals associated with unions or the CCF risked the very real prospect of losing their jobs.

42 In addition to an uncooperative media, financial hardship also limited the dissemination of the CCF message. The CCF refused to accept contributions from big business, preferring instead, as a party of the people, to operate on donations by individuals. The consequences of this were that the party had little money to pay for radio time, for advertisements in the print media, and for dissemination of pamphlets and other educational materials. Residents in some rural areas therefore had little or no knowledge of the CCF, which was exacerbated by a high rate of illiteracy in the province. If CCF members did not travel to speak to rural residents, their message did not reach them. Likewise, the party had little money to pay its provincial secretaries, and so their duties were performed on a voluntary basis, often in addition to working at their full time employment. In Dana Mullen’s case, because she and Vernon did not own a vehicle, her travel to the various constituencies was limited and often dependent on fellow CCFers driving her in their vehicles. At their destination they were often billeted in the homes of other CCF members.

43 The party also lacked sufficient numbers of experienced organizers to adequately build a constituency organization around the candidates, as Clarie Gillis had pointed out in 1945. Nevertheless the party did possess many capable leaders. Lloyd Wilson was a labour man who possessed a solid grasp of the CCF program, and his union organizing informed his political organizing abilities. Edward Goguen was an organizer hired when Wilson served as provincial secretary but the territory each was responsible for was too large. Dana Mullen had no experience as an organizer, but did the best she could under the circumstances with helpful advice from David Lewis and Fred Young. A constant problem was the need for more organizers: even when the party had the funds, few could be found.

44 As Gillis had also noted, the party could have benefitted from stronger links with the labour movement, particularly since Local 594 in Moncton had been instrumental in bringing the party into being in 1933. The links were strong when Lloyd Wilson served as provincial secretary, and he helped to ensure a solid relationship between the party and labour in Moncton throughout the 1940s. The CCL put its strength behind the CCF, and the organizers for the Saint John region of the CCL were in regular communication with Dana Mullen when she was provincial secretary. Overall, it appears that during the decade when the CCF was strongest, approximately 20 percent of the CCF candidates had ties with labour. It is not known what efforts were made to gain the support of workers who were not organized, though the CCF and farmers did both support the growth and development of cooperatives. Although Dana Mullen alluded to meetings in Fredericton being attended mostly by farmers and university students, it is not known how many candidates for the CCF were actually farmers.

45 New Brunswickers were also among the poorest people in the country. Although both francophones and anglophones experienced poverty similarly, this shared reality did not result in political solidarity. The majority of francophones were Acadian and Roman Catholic, and, while many anglophones were also Catholic, they did not hold power in the province. Those who held political power tended to be English-speaking Protestants. Acadians were left to survive in their enclaves. Perhaps the dominant English culture and even the CCF were blind to the degree of self-determination Acadians possessed to retain their culture and language, to promote education, to practice their religion, and to establish cooperatives. The CCF was dominated by English-speaking members and was not able to extend its presence in the French-speaking parts of the province where the Liberals seemed to hold the attention of voters. Although there existed some receptivity to the CCF among francophones, the party did not champion their cause with the savvy of the Liberals, especially under Louis Robichaud.

46 More inquiry into the activities of the CCF in New Brunswick remains to be done. What is clear is that the CCF endeavoured in the 1940s to become a viable political alternative to the traditional parties in New Brunswick. Their optimism and energy fuelled the rapid growth of the movement in the 1940s. As naive as this optimism may seem in hindsight, the very existence of the CCF may have pressed the traditional parties, and notably the Liberals, to defensively implement measures that might not otherwise have come into existence in the absence of the CCF. In the end, this history reveals that even in a sparsely populated province with significant social and economic challenges a mildly socialist party proffering the possibility of “living otherwise” (McKay 4) motivated many earnest individuals to contribute both directly and indirectly to the province’s political identity.

47 Laurel Lewey is an Assistant Professor in the School of Social Work at St. Thomas University. Her current research examines the history of social work in New Brunswick and three waves of radical social workers in Canada from 1914 to 1970.