Articles

“Gladly given for the cause”:

New Brunswick Teacher and Student Support for the War Effort, 1914–1918

Abstract

This article examines the efforts of New Brunswick’s public school teachers and students to support the First World War. Along with participation in the Teachers’ Machine Gun Fund, they were involved in gendered activities such as Home Efficiency Clubs, Cadet Corps, Military Drill, and the “Soldiers of the Soil” movement. Students—male and female, young and old, Anglophone and Francophone—as well as their teachers, also took part in a variety of fundraising efforts that served to reinforce discipline and inculcate patriotism, meeting the state-sponsored definition of a good citizen. By drawing on archival documents, this article highlights the ways that New Brunswick’s teachers and students were inculcated in voluntarism, patriotism, and militarism as they responded to the demands of the war and contributed “for the cause.”

Résumé

Cet article fait le bilan des efforts des enseignants et des élèves des écoles publiques du Nouveau-Brunswick pour appuyer l’effort de la Première Guerre mondiale. Grâce à la participation du Fonds de la Mitrailleuse des Enseignants, ils ont participé à des activités intégrées, telles que les Clubs d’efficacité au foyer, les Corps de cadets, les Corvées de militaires et le mouvement des « Soldats de la terre ». Des élèves, garçons et filles, jeunes et moins jeunes, francophones et anglophones, ainsi que leurs enseignants, ont également participé à diverses campagnes de financement qui ont servi à renforcer la discipline, à inculquer le patriotisme et à promouvoir la définition d’état de bon citoyen. En se fondant sur des documents d’archives, cet article souligne les moyens par lesquels les enseignants et les étudiants du Nouveau-Brunswick ont embrassé le bénévolat, le patriotisme et le militantisme quand ils ont répondu aux besoins de l’effort de guerre et ont contribué « à la cause ».

1 “‘Permit me to acknowledge and thank you for your letter...enclosing draft for $1,000.00, being a donation from the Public School Teachers of New Brunswick, for the purchase of a machine gun for use by the Canadian soldiers.’” In quoting these words of thanks from the Government of Canada, the treasurer of the New Brunswick Teachers’ Machine Gun Fund reported that his own work on the fund had been “gladly given for the cause” (Annual Report of the Schools of New Brunswick 1914–1915, General Report 39). The purchase of a machine gun was just one of various war-related efforts organized in and out of schools by New Brunswick’s public school teachers and students during the First World War. Ranging from serving in the Canadian Expeditionary Force to more prosaic fundraising for the Red Cross, teachers and students were actively involved for the duration of the war. The provincial Board of Education sanctioned activities and events, school personnel facilitated some, and members of voluntary sector organizations such as the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire took on the task of overseeing others. Schools were the locus of various fundraising efforts and served to reinforce discipline and to promote patriotism and militarism. Whether Anglophone or Francophone, teachers and students also participated in gendered activities. Home Efficiency Clubs taught girls preservation methods to counter the food shortage and also expanded into production centres for wartime aids and comforts. The clubs prepared girls for future roles as homemakers and helped to develop a cadre of female domestic science teachers in New Brunswick, thus transforming the curriculum. The Soldiers of the Soil movement enabled boys to learn about agricultural production and help ease the farm labour shortage, while military drill trained male students and teachers to be soldiers.

2 By drawing on documents such as school inspector reports, annual reports, and New Brunswick Board of Education correspondence, this article identifies the range of New Brunswickers’ participation in war-related activities. It also enriches our understanding of the way Canadian schools became part of the effort to win the war by highlighting the manner in which New Brunswick teachers and students replicated and in some instances expanded upon efforts in other provinces. They raised money for the war effort, formed clubs to work on various civic-minded projects, studied war-related textbooks, and welcomed voluntary service organizations into the schools. They responded to the demands of the Great War, and, for the most part, contributed “gladly for the cause.” In the process, they achieved the pedagogical aim of the hidden wartime curriculum: the creation of good Canadians.

3 Other examinations of Canada during the First World War provide a context for this article. Ian McKay (1993) offers a social history of the conflict, elucidating its social impact on the Maritimes and the growing centrality of the state. This study complements McKay’s work. It presents evidence of teacher and student willingness to contribute to war-related projects, revealing an incursion of the state in the form of publicly funded schooling to shape the behaviour and attitudes of a population. In New Brunswick, the accepted response to calls for assistance in food production or preservation, for example, was frequently the formation of school-based clubs, and fundraising was accomplished not through individual canvassing but through group efforts originating within the school. Not every project was acceptable, however; as the evidence will show, those missing a humanitarian element were not sanctioned. Other sources provide a pan-Canadian focus on the First World War. Jeffrey Keshen’s work (1996) is valuable in articulating the way school books influenced young Canadians, both before and during the war, a phenomenon much in evidence in New Brunswick. Robert Rutherdale (2004) and Desmond Morton (2004) provide the larger context of daily life in Canada during the conflict, including schooling. Susan Fisher’s study of Canadian children during the First World War (2011) is particularly useful in identifying the ways that children’s activities both in school and out helped to develop their understanding of service, loyalty, and patriotism. Sarah Glassford and Amy Shaw (2012) highlight the First World War experience of Canadian and Newfoundland women and girls overseas and at home. Each of these professedly “national” studies focuses largely on central and western Canada, giving the Maritime provinces little mention. Rather than assume that war efforts were the same in New Brunswick, this article attempts to fill the gap, demonstrating some of the subtle differences peculiar to the region.

4 For example, missing from the pan-Canadian studies is a focus on the relationships between the French and English outside of Quebec, although some of the narratives in Daphne Read’s edited volume (1978) allude to youthful perceptions of the way Canadian Anglophones and Francophones worked toward the same ends throughout the war. Evidence of school records affirms the thesis of Andrew Theobald’s study of conscription in New Brunswick (2008): that the bitterness of the debate did not have its origins in the province, and that Francophones participated in the war effort almost as willingly as Anglophones. As with most examinations of life in schools, the official record offers few direct accounts of the day-to-day experience of schooling. However, the traces that do exist among reports, correspondence, and other New Brunswick documents make possible a reconstruction of the ways, large and small, in which the province’s teachers and students contributed to the war effort. These reveal what Tim Cook describes as “the history beyond the official history” (2006 8), developing one of the First World War’s major themes: public support for the war project. This nonmilitary history adds to our understanding of the Canadian home front during the conflict and the role of publicly funded schools in promoting the goals of the state.

5 The conditions under which support could grow were already well established when the war was declared. In particular, the ideologies of voluntarism, patriotism, and militarism were deeply embedded in New Brunswick’s publicly funded schools. Arbor Day had been included in the province’s Manual of the School Law as early as 1887 as a holiday with the aim of cultivating students’ “habits of neatness and order” (Manual of the School Law 1887 68). Empire Day, first appearing in the 1901 Manual (143), provided clear instructions for its observance with the comment: “A programme, prepared beforehand by the teacher, consisting of lessons on the extent and resources of the British Empire, the singing of patriotic songs, the delivery of recitations and such other exercises as will tend to cultivate a love of country and loyalty to the Empire” (Manual 1906 129). Empire Day emphasized the importance of school flags, and the 1913 Manual included specific instructions regarding the flag, with the requirement that teachers and students offer a “military salute” and utter the phrase, “Emblem of Liberty, Truth and Justice—Flag of my Country to thee I bow,” followed by the singing of the national anthem (Manual 1913 200).

6 Patriotism was also promoted with prescribed textbooks. George Hay’s 1902 History of Canada was authorized in New Brunswick and published in a single volume with William Robertson’s Public School History of England. Hay’s description of the Boer War was likely read by many New Brunswick boys who went on to serve in the First World War. This history recorded that “volunteers from Canada and other parts of the Empire won the highest praise for the coolness and courage which they showed on many a hard-fought battlefield” (Robertson and Hay 289). In his separate history of New Brunswick, also prescribed in the province’s schools, Hay sustained the theme proclaiming that “common danger and a common death have drawn more tightly the bonds which now hold together the different parts of the Empire” (Hay 174). Meanwhile the high school world history text was first prescribed in 1910, and in it the American author reported that in English history, the leading events of the preceding century fell under three headings: “(1) progress towards democracy; (2) extension of the principle of religious equality; and (3) the growth of the British colonial empire” (Myers 689). Textbooks used in New Brunswick’s French language classrooms also served to inculcate love of country. An early-twentieth-century reader included a poem titled “La Patrie,” the concluding stanza of which read, “Comment les nommestu?—Sur l’immense prairie, / Sur les monts, les forêts l’enfant jeta les yeux; / Puis, sa main désignant la terre des aïeux” «Le Canada! Dit-il : c’est ma chère Patrie» (Syllabaire Et Premier Livre De Lecture 48). The image of a flag vaguely resembling the Red Ensign accompanied the poem.

7 Public schools promoted Cadet Corps and military drill in schools before the outbreak of war in 1914. The federal Minister of Militia and Defence was explicit in presenting to the New Brunswick premier his rationale, in 1909, for introducing military drill to schools. The goal was

8 Whether or not the rationale was a deciding factor, Cadet Corps and military drill were introduced at the New Brunswick Normal School during the 1909–1910 school year, and hailed by the principal for their results, including “a better carriage on the part of students, and more confidence in tone of voice and bearing in teaching” (NB Board of Education, ARSNB 1909–1910, Appendix A 7). In spite of the principal’s enthusiasm, the senior school administrator in New Brunswick, Chief Superintendent W.S. Carter, admitted soon after its introduction that his office had little interest in military drill. As a bureaucrat, he considered the program to be an imposition. He was not happy with the volume of complaint produced by a reduction in the pay rate for teachers who took the training, saying “it may be that their patriotism would overcome any mercenary motives they might have, but in these days most young men have the commercial instinct, and are able to do quite well along these lines during the summer vacation” (Carter to Roscoe). Still, in the long run, military drill and Cadet Corps were less controversial programs in New Brunswick than physical training, although all three were introduced at the same time and taught by the same instructors. Physical training was required of all New Brunswick teachers in order to keep their licences. Military drill and Cadet Corps were voluntary, and with Canada’s entry into war the province’s programs were well established and subject to positive comments in annual reports.

9 Voluntary, patriotic, and military activities already established in schools before 1914 were expanded with the declaration of war (Rutherdale 92). The most pervasive of these were the fundraising drives with a continual procession of special projects undertaken by schools (Morton 2004 118). Carter highlighted the pedagogical benefits of the fundraising, observing in one report that “possibly the self-denial engendered, the sympathy aroused by the suffering of others, and the planning of ways and means to provide for their relief, have an educational value beyond the amount of money raised” (ARSNB 1915–1916, General Report 57).

10 The patriotic fervour that sustained Canadians was manifested in these drives, and became a regular feature in New Brunswick schools. Sometimes the money went directly to support humanitarian organizations such as the Red Cross in “the binding up of wounds and to work for the healing both of body and spirit” (Clements 3). The province’s Normal School students, for example, raised seven hundred dollars for the Red Cross in Fredericton (ARSNB 1914–1915, Appendix A 6). Some drives were designed to promote the identification of New Brunswick children with soldiers’ families through donations to the Canadian Patriotic Fund (ARSNB 1913–1914, Trustee’s Reports 122). Humanitarianism also propelled a major drive to benefit Belgian children. In 1916 the New Brunswick Board of Education responded to an appeal from the province’s lieutenant-governor and Canada’s governor general. The board declared 15 November 1916 “Children’s Day” in the province, recognizing it as a school holiday and encouraging children to donate “the proceeds of concert, sports, or other entertainments, quite in consonance with the ordinary routine of school life and organized by the children themselves, (assisted by teachers and parents)” [sic] to the Belgian Children’s Relief Fund (Carter, “Children’s Day”). In the end, New Brunswick’s “Children’s Day” raised over $33,000 for the Belgian Children’s Relief Fund (Carter to Blacklock). Humanitarianism, voluntarism, and patriotism converged in a focused, system-wide communal project with the publicly funded school at its centre.

11 Efforts that fell outside of the normative structure of fundraising were discouraged. For instance, the Children’s Day announcement led to some concern about the difficulties of mounting such a project. A teacher in one small community wrote that “it would be almost useless to try to raise any funds by means of a sale, concert etc. Most of the people here are in very straightened circumstances and very few would would [sic] attend an entertainment except the children themselves” (Baird to Carter). The letter writer proposed that the school canvas local businesses for contributions. Carter’s response is unknown, but the proposal contradicted the explicitly stated requirement that the fundraising take place on school property and be part of the school day. Two brothers from rural Hawkshaw, aged thirteen and fifteen, clearly engaged with propaganda promoting patriotic response to the war. They took slight offence, however, to the suggestion that their fundraising efforts needed their teachers’ imprimatur, saying they had raised the money without the help of any teacher and intended it for the general, not the Children’s Fund, but “as it is all going for the same purpose it will make no difference” (Cronkhite to Carter). They preferred to act independently, but recalled the larger humanitarian aim of the project.

12 The fundraising campaign that was definitely not humanitarian in nature was the New Brunswick Teachers’ Machine Gun Fund. The idea for the fund was first suggested at a rural science school in Sussex during the summer of 1915, and Carter promoted it at various teachers’ institutes. The fund was the local iteration of a short-lived national effort described by Matthew Bray as a “popular manifestation of English-Canadian patriotic fervor” (Bray 1980 150). It was initiated that summer when the prime minister and the minister of the militia visited London, England. In their absence the Acting Minister of the Militia, James Lougheed, oversaw the project, which had as its goal the improvement of the artillery used by the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Bray 1976 93). After a British newspaper had noted the superiority of German weaponry (Hopkins 1916), the project to raise funds for machine guns grew quickly with groups and organizations competing to purchase the greatest number of guns, each of which cost one thousand dollars. In a letter to Superintendent Carter, the treasurer of the New Brunswick Teachers’ Machine Gun Fund detailed the level of participation in the effort, noting that “about eight hundred teachers and former teachers representing nearly all parts of the province responded, with donations of from 50 cents to $25.00. A number of ladies, former teachers, gave one dollar for each year in the profession” (ARSNB 1914–1915, General Report 38).

13 Attempts to promote voluntarism and patriotism were not always successful, and fundraising efforts were not without controversy. One teacher requested, “for the benefit of those who are victims of the rumours of misrepresentation afloat in so very many localities concerning the moneys sent to Belgium and handling of same,” that Carter send to the newspapers “a truthful station [sic] concerning the money as handled by your Commission from Canada to Belgium orphans” (Fisher to Education Office). Carter responded to this latter concern somewhat testily, saying of anyone making a donation to the Belgian Children’s Relief Fund, “I would far rather they would not do so if they have any doubt as to the handling and destination of the money” (Carter to Fisher).

14 The New Brunswick Teachers’ Machine Gun Fund was also problematic. Some teachers requested that the monies be offered instead to the Red Cross. In the end, only the surplus of $64.90 collected over the thousand-dollar goal was forwarded to that organization (ARSNB 1914–1915, General Report 38–39). Indeed, the minister of militia and the prime minister shared these concerns, suggesting that it would be better if Canadians donated money to the Red Cross and the Patriotic Fund. By November, when the New Brunswick teachers’ thousand dollars was forwarded to Ottawa, the Machine Gun Fund had been shut down by the prime minister, who declared that it was more properly the task of the government than the general public to equip the military (Bray 197695). In other words, the humanitarian element was essential in state-sponsored patriotic voluntary fundraising projects.

15 In his administrative capacity, Carter’s responsibility to bestow official blessing upon fundraising efforts helped to sustain participation throughout the province. In the case of the Children’s Day Fund, he initially encouraged teachers and students with letters of thanks—he responded to one school’s early November donation of $114.13 by saying it was the largest amount yet received from a school and by sending a book in the return post “as a small token of appreciation for your efforts” (Carter to Anderson). The success of the project, however, soon made such gestures too onerous. In December a school inspector singled out a teacher’s “remarkable” efforts, saying that hers was “a small isolated district widely separated from any other district, and several miles from the river front or railway. The teacher of that school deserves credit” (Meagher to Carter). Carter responded saying he was pleased with fundraising efforts: “There has been, however, such a multitude of these that I hesitate to write any particular ones, lest it might cause feeling, and I could not hope to overtake commendatory notices to all who deserve them” (Carter to Meagher). Projects were initiated in urban centres: Chatham students presented entertainments that raised four hundred dollars, and Saint John teachers raised thousands of dollars over several years for the Patriotic, Belgian Relief, and Red Cross Funds (ARSNB 1915–1916, Trustee Reports 106; ARSNB 1914–1915, Trustee Reports 86). Smaller schools in rural communities also did their part (Clements 22–25). For example, the Central Johnville School in Carleton County raised forty dollars from a concert and pie sale for the Belgian Children (Ryan to Carter). Patriotism and voluntarism were so effectively inculcated in New Brunswick that as the war progressed Carter no longer felt the need to encourage participation among teachers and students.

16 The war-related experience of New Brunswick teachers and students went beyond fundraising to active enlistment. Carter’s first wartime report mentioned the enlistment of two out of eight school inspectors, and “a very large number of our male teachers” (ARSNB 1914–1915, General Report 37), and periodically during the war the Board of Education compiled rosters of enlisted teachers (List of N.B. Teachers Who Have Enlisted; Carter to Hutchins; Members of Teaching Profession). Although these rosters contain discrepancies, they do indicate that many teachers and students who fought achieved distinguished service. The names of teacher Rolphe K. Nevers (misspelled) and Normal School student Albert D. Creamer were included in the Red Cross list of prisoners of war (Clements 17). A number were killed. One of the first New Brunswick teachers to die at the front was Charles Lawson of Saint John High School. After his November 1915 wounding in no man’s land, a nurse at the casual clearing station reported his response to his injuries: “He smiled and said it was what they were out for” (Jolley to Julia Lawson). He died a few hours later. Lawson had been the valedictorian of the Saint John High School class of 1899 and was described by Carter as a “young and most promising” secondary school teacher (Lawson, “Valedictory Address”; ARSNB 1914–1915, General Report 38). His loss was keenly felt among his colleagues and students whose expressions of condolence also interpreted his death as an example of patriotism to be recognized and shared (Miller to Jessie Lawson 2 August 1926; Payson to Julia Lawson).

17 The motivation of those teachers and students who enlisted was complex, and did not necessarily include patriotism. Desmond Morton enumerates common factors among Canadian soldiers, including “social pressure, unemployment, escape from a tiresome family or a dead-end job, self-respect, and proving one’s manhood” (Morton 1993 52). To the extent that they can be determined, New Brunswick teachers and students enlisted for all of these reasons. For example, and notwithstanding his final patriotic words as he lay dying, Charles Lawson otherwise highlighted the benefit of the change in his vocation from teacher to soldier at the front. In an earlier letter to his mother he wrote, “Just to think, ordinarily I would be grinding away at the old school work now, and this work, though similar to it in some ways, still is somewhat different. Certainly it is great for the health anyway” (Lawson to Julia Lawson). Teacher Boyd Anderson’s letters home to a friend included descriptions of the fighting, always imbued with esprit de corps, as when he wrote “I want to say this now—that a better lot of men you cannot find than the New Brunswick Battery. They will stand up to anything. Not a murmur” (Anderson to Frank 6). Whatever their private expressions of motivation, the public representation of those who enlisted was sacrifice, and that interpretation prompted such men as the principal of St. Stephen High School to express a desire to “serve [in the school] when I cannot be with the noble fellows in the trenches” (Tingley to Carter). The result was the broad support of the war effort, manifested in school-centred activities.

18 For some teachers who enlisted or were conscripted, the interruption of their teaching career was a concern, and in many cases the concern was economic. This placed the Board of Education in an awkward position. One school principal expressed the worry that as an only son supporting parents who needed his help on the farm, he should be spared from conscription (Quail to Carter). Carter’s response, while sympathetic, indicated that offering an exemption to teachers would be a violation of the law (Carter to Quail). Another principal enlisting hoped his teacher’s salary would continue to be paid during his time overseas (Jones to Carter and Clark). Eventually, the board agreed that the duration of his military service would be “recognized as teaching time for awards of pensions and for length of service in the apportionment of Government Grants” (Board of Education Minutes 1909–1935).

19 Absent teachers and students inspired those who remained at home to find ways to acknowledge their colleagues overseas, and to undertake service efforts of their own. In 1915 the trustees of the town of Chatham noted that many graduates and teachers were “doing their part in upholding the honor [sic] of the Empire and the glory of the Union Jack upon the field of battle” (ARSNB 1914–1915, Trustees Report 14). The November 1915 issue of the Educational Review reported a resolution taken by the teachers’ institutes of York and Sunbury Counties to express their “due appreciation of the heroism and self-sacrifice of the teachers of this province who have left home and all that is dear to them and have gone to the front in defence [sic] of King, country and home” (“News” 120). Some teachers voluntarily authorized a percentage of their salary to be “devoted to patriotic purposes” (Carter to Ord Marshall). The language of sacrifice and patriotism provides further evidence of the extent to which schools promoted the propaganda project of the nation-state to define good citizens.

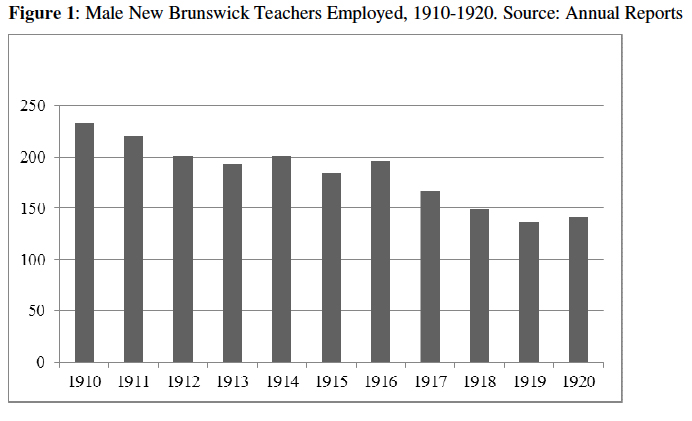

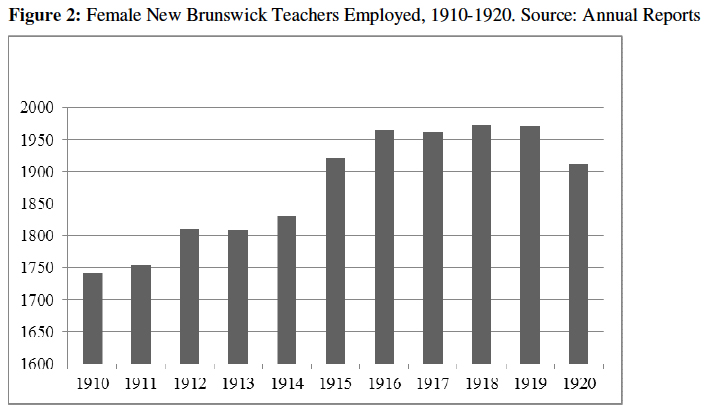

20 From the Board of Education’s perspective, the effect of the war upon schools was noticeable, first, because it accelerated the change in the face of teaching in New Brunswick. Carter reported that “as a very large number of our male teachers have enlisted and their places have been taken by female teachers, there has been a tendency toward lower salaries for the positions thus filled” (ARSNB 1914–1915, General Report 37). But the rise in the number of female teachers was not only due to male enlistment. Carter noted “with some degree of disquiet” the tendency particularly in towns and cities for trustees to hire female rather than male teachers, with the result that some male graduates of the Normal School were unable to attain employment. According to Carter, this was problematic for its effect on the children, because “female teachers do excellent work but I am firmly of the opinion that all boys and girls should for a part of their school life come under the influence of male teachers” (ARSNB 1913–1914, General Report 40). For local school boards, the absence of male teachers represented a cost saving. Whether it was because male teachers enlisted, or because trustees hired female rather than male teachers specifically in order to save money, or for any number of other reasons, data from the chief superintendent’s annual reports show that between 1912 and 1920 the numbers of male and female teachers employed in New Brunswick had opposite trajectories, with females rising and males falling (Figures 1 and 2).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

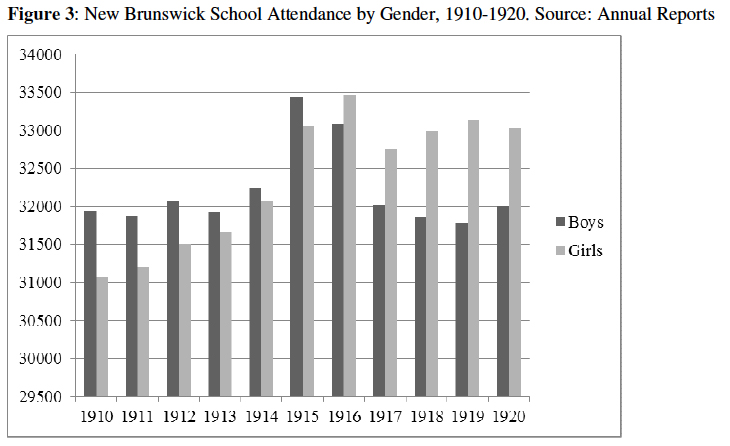

Display large image of Figure 221 The same pattern was true of school attendance figures for boys and girls during this period, although the same caveat applies to both: we cannot assume a causal relationship between the war and school employment or attendance, but a correlation is apparent (Figure 3).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 322 While the enlistment of male teachers and students provides clear evidence of the impact of the war on schools, sometimes women’s wartime ambitions also served to remove them from the school. The actions of these teachers went against the prevailing thought that women should stay in their classrooms during wartime (Quiney 2003 79). Carter described “a great demand for women to take the places of men who have enlisted, in business and all other occupations. A great number of our young women have undertaken the work of nursing and other war work” (ARSNB 1916–1917, General Report 37). Forty Canadian teachers took on unpaid work in Europe with the Voluntary Aid Detachment of the St. John Ambulance, providing the opportunity to experience direct contact with wounded soldiers. Among them was a lone New Brunswick teacher who nursed for thirteen months (Quiney 2002 415).

23 Their gender excluded females from the combatant role and few women made it to Europe as nurses, but New Brunswick women found ways to serve in their home communities. In her study of the Canadian Red Cross Society, Sarah Glassford notes the observation of one official that in the war’s early days, women who felt the need to channel their patriotism turned to Red Cross work as “‘almost the only outlet for [women’s] desire to serve and save’” (Glassford 259). As middle-class women, teachers were naturally drawn to middle-class voluntary organizations such as the Red Cross and the IODE, and this served to influence their students. The Junior Red Cross did not become firmly established in New Brunswick until after the war, an effort organized by Jessie Lawson, teacher and sister of Charles Lawson (Miller to Lawson, 31 March 1927). Still, the group had its wartime origins in the examples of out-of-school fundraising by girls’ groups on behalf of the Red Cross in rural communities, as well as from within schools across the province, which elicited special mention in Red Cross reports (Glassford 134; Sheehan 1987 248; Clements 21, 24). Beyond raising money for the war effort, New Brunswick girls and women by the thousands gave of their time and talents. The Director of Manual Training, Fletcher Peacock, reported in 1918 that school sewing periods were devoted to Red Cross work which spilled into their spare time, with the example that Saint John girls made over two thousand Red Cross articles (ARSNB 1917–18, Report of Director of Manual Training 155).

24 The largest concerted effort of New Brunswick’s female teachers and students, however, involved the Home Efficiency Clubs. The clubs were initiated as a war measure in 1917 to save food by promoting canning and preserving among the province’s female students aged ten and older. Almost all domestic science teachers volunteered to attend four days of training at the Ladies’ College in Sackville, and then gave up as much as four weeks of their vacation by returning to their school communities to teach the girls these new skills. The model for the clubs was American, and the original plan proposed that completed products would be offered for sale, with the proceeds put toward victory bonds. In their initial year of operation, about eighty clubs were organized (ARSNB 1916–17, Report of Director of Manual Training 146–55). The only indication that boys might be involved in this activity is in a letter from Peacock to the supervisor of the Boys’ Home in Saint John about sending a teacher to teach the boys about canning the vegetables from their garden (Peacock to Parker). In January 1918, Peacock appointed a supervisor of the Home Efficiency movement, who, with two assistants and in spite of the interruption of the Spanish flu epidemic, organized over 250 clubs across the province. Canned and preserved goods were displayed in “fairs” held at the end of the season, although in fewer numbers than hoped because of the epidemic (ARSNB 1917–1918, Report of Director of Manual Training 154–55). The legitimacy of the clubs was strengthened when, for the second year of their existence, teachers at the Summer Institute were paid (Peacock to Mallory, 13 March 1918).

25 Members’ efforts were not restricted to canning and sewing. Clubs were expected to have a plan for each season of the year, “sewing for the winter,—gardening for the spring,—canning for the summer, bread-making, etc. for the fall” (Peacock to Kierstead). In 1918 when the Canadian Expeditionary Force experienced a shortage of absorbent cotton for dressing wounds, New Brunswick was one of only three provinces with sufficient supply of sphagnum moss to serve as a substitute (Glassford 144). After a meeting with a representative of the Natural History Society in charge of moss collection in New Brunswick, Peacock recruited Home Efficiency Club teachers to assist in the effort, suggesting that it would be “very admirable work for our girls throughout the Province” (Peacock to Baxter). By war’s end, primary teachers in Saint John were credited with grading and sorting thirty-three and a half pounds of contributions from the public (Clements 42–43).

26 For Fletcher Peacock, the Home Efficiency Clubs were more than just a war measure; they laid the groundwork for promoting the further development of domestic science as part of the New Brunswick school curriculum, with a plan to offer instruction in sewing and the preparation of hot lunches to rural schools (ARSNB 1917–18, Report of Director of Manual Training 151, 157). The system adopted by New Brunswick differed from the Manitoba one, where canning was added to the activities of existing community clubs for both boys and girls (Newton to Peacock). New Brunswick’s Home Efficiency Clubs aided the identification of talented, highly motivated female teachers who could serve as pioneer instructors in domestic science (Peacock to Mallory, 26 March 1918). Peacock was also firm in his belief that the work of the clubs should be an integral part of the school day in order to connect the school with the home and to “get many times as much work from the girls that you other wise would” [sic] (Peacock to Burgess). He saw this as an example of the “project method” pedagogy, then in its infancy in North America (ARSNB 1916–17, Report of Director of Manual Training 155). This attitude was directly opposed to the view of Chief Superintendent Carter, who in his correspondence judged that the school day was already too full to be supplemented with the work of the clubs, adding that school regulations would not permit it (Carter to Dickson). Correspondence records offer no evidence that the two school administrators worked out this difference of opinion in writing, but the subsequent development of the clubs suggests that Peacock’s stance prevailed. As for the motivation of the girls involved, instructors submitted reports about the clubs to Peacock’s office, and under “remarks” they noted more frequently enthusiasm for learning domestic skills than patriotism (lack of enthusiasm was blamed in one instance on the girls’ heavy scholastic workload, and in another on haying season [Peacock, Home Efficiency Clubs correspondence 1917–1918]). But Peacock was convinced of the benefits to the girls of their participation, saying that, if properly mobilized, the girls were willing workers, and “in these times of stress it would seem that the schools should give them the opportunity to serve in this and allied ways” (ARSNB 1916–1917, Report of Director of Manual Training 154).

27 One of the ways in which the Home Efficiency Clubs were a made-in-New Brunswick project was the concerted effort by Fletcher Peacock to ensure that clubs were established in Francophone as well as Anglophone areas. Peacock canvassed his French school inspectors for bilingual teachers with First Class licences who would be comfortable speaking in public. Inspector Hébert reported that French teachers in his district were “timid” and nearly all of his First Class teachers had moved to Moncton. The shortage of well-trained Acadian teachers was a chronic challenge not just for Peacock but also for the entire school system (MacNaughton 182–83). Peacock’s consideration of the province’s Acadian population was unusual for a school administrator, a fact acknowledged by Hébert when he thanked Peacock for his “courtesy” in recruiting French teachers (Hébert to Peacock, 11 April 1918). The inspector had long advocated for improved opportunities for French teachers and students in a school system in which no one at the central board office in Fredericton could speak French fluently (Landry 1–4; Chief Clerk to Babineau). Peacock soon determined that teachers trained appropriately in domestic science were likely convent educated (Peacock to Doucet, 11 March 1918; Peacock to O’Blenes 17 May 1918). One candidate from Inspector Hébert’s district seemed perfect in every way except for her lack of fluency in English; Peacock enthused about her talents while encouraging her to improve her English (Peacock to Hébert, 4 September 1918). The situation prompted Hébert to suggest that training should be offered entirely in French in French districts (Hébert to Peacock, 10 September 1918). Peacock was not prepared to go so far, however, and did not respond directly to the proposal, replying instead that he wished more French students would train for domestic science in the United States and return to New Brunswick. “Such a girl would get a splendid salary,” he wrote, “and I can think of no way in which she would serve her Province more effectively” (Peacock to Hébert, 13 September 1918). Despite the challenges, once appropriate instructors were secured, clubs in French districts were “thoroughly organized” (Peacock to Doucet, 8 July 1918).

28 Language was a significant factor affecting the participation of Acadians in the war effort, teachers and students included. The Canadian Red Cross Society, for example, made few attempts to accommodate French speakers, and did not translate the organization’s literature (Glassford 138–39). In keeping with its motto “One Flag, one Throne, one Empire,” IODE-donated school books and essay contests were English only (Imperial Order 2). Civilian recruiting for the Canadian Expeditionary Force was conducted largely in English (Bray 1980 152). Meanwhile, French-Canadian communities outside New Brunswick began to question their place in the pan-Canadian imperialist project as a result of the Ontario schools controversy concerning the plan of the Ontario government to prohibit teaching in French after grade 2. The issue influenced French participation in the war (Dutil 98, 96). New Brunswick’s Acadians had fought and lost a similar battle over separate schools forty years earlier. Their constitutional challenge, which resulted in a decision against them in the Privy Council in London, centred on religion rather than language, but the result was that in New Brunswick’s publicly funded schools, unilingual French language instruction ended after the first four grades. After that, schools were bilingual, even in areas where students spoke only French (MacNaughton 212; Hody 3). Thus Acadians had no illusions about the province’s assimilationist school system and society (Toner 95–96). Acadian reluctance to become involved in the war effort also went beyond language. New Brunswick’s Francophone males, like their Quebec and even many of their provincial Anglophone counterparts, tended to engage in land- or sea-based occupations, and concerns about losing their families’ livelihoods precluded them from enlisting (Dutil 98; Theobald 2000 153; MacKenzie 355). But when called upon, Acadian teachers and students engaged in the war effort, including joining Home Efficiency Clubs. The Red Cross report on New Brunswick’s Great War activities highlighted the efforts of active clubs in such Acadian areas as Edmundston, Richibucto, and Shediac (Clement 47–48). Of thirty-eight names on the 1916 Board of Education roster of teachers who had enlisted, five were identifiably Acadian names of teachers from French districts (Collections Canada; Leroux).

29 Some elements of schooling were relatively stable throughout the course of the war. For example, textbooks were essentially unchanged during the conflict, partly due to wartime austerity, with the result that their militaristic content was retained (Carter to J.M. Dent and Sons). Added to these were new volumes such as Sir Edward Parrott’s Children’s History of the War, which Carter continued to recommend to teachers long after the war’s end (Carter to Arnold). One major addition to schoolrooms was the Canada War Book, produced nationally as part of a thrift campaign of the Canadian Patriotic Fund. The New Brunswick edition, with an introduction written by Carter, was sent to all public schools in early 1918. He instructed that a copy should be given to all teachers and all students over age ten, and five minutes of the day’s lessons should be devoted to its contents, preferably immediately after opening exercises. Questions from the texts could be included in examinations. These materials reinforced the messages of the fundraising drives and Empire Day, the strength and endurance of the Canadian nation, and the importance of service to country. Perhaps Peacock’s efforts earlier in the year to include the Acadian population in Home Efficiency Clubs influenced Carter; in spite of resistance from federal officials and the outright refusal of western-Canadian school administrators to do so, Carter proposed to the premier’s secretary that a number of copies of the New Brunswick edition of the War Book should be printed in French (W.S. Carter to E.S. Carter).

30 Multiple opportunities for contributing to the war effort arose within schools, many of which created periodic disruptions of the school day and the school year. Often these disruptions were accepted because they served civic and national purposes, and as such could be used to further pedagogical ends. Some events were the creation of individual teachers or schools. In the Glassville area, for example, schools undertook a 1916 “patriotic-field-day,” proposed as “a splendid thing for the parents to get together with the scholars and teachers.” They would all be addressed “on the thing which should be forever in the minds of all today, ‘Patriotism’” (Bacon to Carter).

31 Other events were local renditions of national efforts. Wartime Empire Day observances in New Brunswick, for example, were distinct in Canada for their equal focus on the empire and the war (Sheehan 198920). Students and teachers in Anglophone and Francophone schools alike celebrated the day in great numbers, especially in 1915. That year ceremonies ranged from Campbellton, where “the pupils paraded, headed by the Boy Scouts and Cadets,” to Fredericton, where “about one thousand pupils were in parade, each carrying the Union Jack.” In addition, eight hundred Chatham school children were “marshalled under their teachers and took part in farewell services by singing and other exercises upon the occasion of a company of our gallant boys leaving to take a share in the war which is now going on” (ARSNB 1914–1915, Trustee Reports 75, 113, 120). The Empire Day program in loyalist Saint John was presented under the auspices of the Women’s Canadian Club, with the blessing of the Chief Superintendent and Board of Education. The teachers’ guide included instructions to make the day “bright, interesting and inspiring” by using history and geography to impress upon students the empire’s “reality, growth, magnitude, essential unity, and common purpose; and the privileges, responsibilities and duties of citizenship” (Women’s Canadian Club 3). The day also included a reading titled “The War,” which read in part: “When the opportunity came the German rulers threw away their cloak of civilization and Christian brotherhood, and stood out boldly before the world saying ‘Peace means inability and cowardice, I am brave, I am able, I am prepared—why should I desire Peace!’ And the German people readily went to war” (Women’s Canadian Club 10).

32 This vilification of the enemy echoed the sentiments found in the teaching materials of other Allied nations (Kennedy 56; Stapleton 157). As a whole, these community activities aided and promoted the war effort, but they also accomplished the specific pedagogical goals of inculcating patriotism and militarism in students.

33 Patriotism and voluntarism had long been cultivated by organizations that worked beyond school walls. One of the most influential of these was the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE). Established in Fredericton in January 1900, it was designed “to stimulate patriotism, foster unity within the British Commonwealth and Empire, cherish the memory of heroic deeds, forward every good work for the betterment of their country and people and develop high standards of citizenship.” By the start of the First World War, New Brunswick was home to a provincial and six primary chapters. In a list of the organization’s major departments, “education” came first (IODE). Scholars observe that in most combatant nations, the incursion into schools of voluntary sector organizations featured efforts to promote patriotism, which reinforced the messages of the official curriculum (Chickering 503; Kennedy 55; Graham 435; Mangan 116; Riedi 586–7; Rutherdale 61). Similar to the evidence of the Women’s Canadian Club Saint John program of 1915, IODE organizers also directed their attention to the conflict itself. Historians have noted the extraordinary depth of IODE involvement in Canadian schools, nowhere more so than in New Brunswick, where members replaced teachers in organizing and planning Empire Day events (Sheehan 1995 264). For example, a war-focused event at Fredericton High School included an address by the Anglican bishop describing Canadian soldiers in battle at the front (Sheehan 1989 20). During the war, the IODE also changed the nature of the essay writing competitions it sponsored and administered so that they would reinforce the official messages and mythologies related to the war. If they could not fight, children could support the war through their written expressions of patriotism (Rutherdale 212; Perry 231; Riedi 588).

34 Likewise, the presence of Cadet Corps and military drill programs represents the deliberate and strategic insertion into New Brunswick schools of projects designed to create a compliant and patriotic group of students supportive of the militaristic goals of the nation-state. The two were woven into the school curriculum and served as additions to the physical training program. These programs were part of a national movement under the patronage of Lord Strathcona, who judged the courses to be “of the highest value in developing the moral, physical and intellectual qualities of children, as well as that valuable quality known as patriotism” (Morton 197862). Cadet Corps and military drill were taught outside of school hours, and at their wartime height they were centrepieces of male student and teacher war efforts (ARSNB 1909–1910, Normal School Report 7; ARSNB 1915–1916, Normal School Report 5). The two were courses at the secondary school and normal school level, offered as long as student numbers warranted them. Both were instructed by the same men (and in New Brunswick they were all men) who conducted physical training classes. Instructor salaries were paid and Corps prizes were awarded out of Strathcona trust funds, which also paid for physical training prizes (ARSNB 1917–1918, Trustee Reports 101–2). In 1914–15, New Brunswick had twenty-four Cadet Corps, with another five added the following year. The aims of the Cadet Corps, as described at a 1916 Teachers’ Institute by a New Brunswick educator, were “to develop a manly spirit,” “to develop the mental powers,” “to prepare men for military service,” to foster “a social affiliation” and a “sense of honour,” and to develop cleanliness and discipline. Of all of these, according to the speaker, “discipline was the greatest and most helpful aid toward self-control and support of the laws of a democratic government. This training in obedience was helpful in curbing that spirit of carelessness that might arise from the personal freedom that grew out of the democratic government under which Canadians lived” (ARSNB 1915–1916, Teachers’ Institute Reports 153–54).

35 During the war, New Brunswick’s Normal School principal also emphasized the benefits of cadet training in terms of directly serving the war effort. He calculated that since the start of the war 140 students and graduates of the school went “bravely to do battle for the cause of liberty and justice.…Twenty-six of these are or were officers, showing how well their former training has helped them. Thirty-two have been wounded, and six are prisoners of war. Fourteen have made the supreme sacrifice” (ARSNB 1916–1917, Normal School Report 8). The sight of young men in military formation on school grounds served as a symbol to the school community of service to nation. Though some provinces made Canadian Cadet Corps participation mandatory (Comacchio 113–14; Sheehan 1995264), the evidence in New Brunswick suggests that the program was voluntary, and although the funding for instructors and prizes was limited, interest in it continued throughout the war (ARSNB 1917–1918, General Report 49). At the height of the war in New Brunswick, the Cadet Corps and military drill were important elements of wartime pedagogy. Eventually interest waned at the war’s conclusion, partly because of a shortage of qualified instructors (ARSNB 1917–1918, Inspector Reports 49). The courses did not completely disappear, however. Indeed, minutes for local board of school trustees’ meetings indicate that as late as 1920 some Saint John schools still had military drill and rifle range facilities (Board of School Trustees of Saint John 8 March 1920).

36 The foregoing examples of wartime effort were focused on the schools, but one activity took students away from school property. In the spring of 1917, as an outgrowth of the same initiative to increase food production and preservation that gave rise to the Home Efficiency Clubs, New Brunswick teachers were urged to encourage children to cultivate home gardens (Power to Teachers and Trustees). As months passed, the province’s need to maintain agricultural production became acute, and “pressing invitations were given in all instances to children of suitable age and capable of doing so to devote their energy and best efforts to work on the farm” (ARSNB 1916–1917, Inspector Reports 26). But the call to serve was not accepted by all without reservation. Allowing students to work on farms meant that school attendance fell well below average in some areas, a cause for concern among school administrators. The chief superintendent observed to a group of potential farm volunteers from Fredericton High School that any patriotic work would have to be undertaken by the entire school body, since the fact that “a few are working is no good and sufficient reason for the rest being idle” (Carter to the Boys of the High School). The students in turn expressed concern that they would lose their year, and proposed instead that anyone preparing for high school or matriculation exams should be exempt from patriotic service, but that students in grades 9 and 10 might be engaged as a group (Students of the Fredericton High School to Carter).

37 It is worth noting that early on these conversations about farm work did not refer to a gendered activity; Carter and the students referred to the farm work of both boys and girls. By 1918 the need for help in agricultural production was urgent, and this time a call went out from the provincial Department of Lands and Mines for young men only to participate in the newly created “Soldiers of the Soil” movement (McMullen to Carter). This federal program for boys aged 15 to 19 was intended to ease the farm labour shortage caused by enlistment (Champ 7). The 1917–18 report of one rural school inspector noted that boys absent from school could “assist in seeding and harvesting. The idea of having such identified with an organization with patriotic aims should be an effective means of inculcating patriotism” (ARSNB 1917– 1918, Inspector Reports 49). In other words, and as other scholars have emphasized, the site of citizenship education or national indoctrination moved beyond the classroom walls and off school property (Thobani 9; Tomkins 93–94). The program was still problematic, however, as Carter explained, saying “pupils are not expected to enlist [in the Soldiers of the Soil program] that are not in good standing in the April examinations, in order that lazy boys may not be encouraged to evade their work” (Carter to Fox). Like the Home Efficiency Clubs, the Soldiers of the Soil movement was an outgrowth of the wartime economy, a program with school-based recruitment to further the interests of the state and to develop in students a sense of social and civic responsibility. Textbook learning gave way to education about life skills and participation for the benefit of the broader community.

38 The preceding analysis highlights the range of opportunities for New Brunswick teachers and students to support the war effort from 1914 to 1918 and to demonstrate the quality of their citizenship. In terms of the day-to-day operation during the conflict, schools continued to function, with only minor disruption. The significant loss of teaching personnel through enlistment or war work, the pervasiveness of fundraising campaigns involving teachers and schoolchildren, the incursion into schools of voluntary sector organizations, and changes to curriculum to include domestic science, military training, and patriotic lessons were the most significant manifestations of the many ways in which New Brunswickers were asked to help win the war. The framing of participation as a patriotic necessity raised the stakes further. The level of sacrifice ranged from death on the battlefield to the inconvenience of impediments to the efficient operation of the school system or the interruption of the normal school calendar. New Brunswick schools served as a focal point of contribution during the First World War. Boys and girls, men and women, teachers and students, Anglophones and Francophones participated throughout. They aided “the cause” in ways as symbolic as students parading through the streets carrying Union Jacks, and as practical as teachers purchasing a machine gun for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Their example adds depth to our understanding of the involvement of Canadian students and teachers in the effort to win the First World War, and of historical definitions of Canadian citizenship.

Frances Helyar is an Assistant Professor of Education at the Orillia campus of Lakehead University, where she specializes in teaching Educational Law and Foundations.