Articles

New Brunswick’s Perfect Demographic Storm

Abstract

The demographic storm clouds have been gathering for some time. No one should say we did not have sufficient advance warning of the gathering storm. Everyone should conclude that we did not act in a proactive and purposeful manner in order to avert the disastrous consequences of this perfect demographic storm. Despite the silver lining in the 2011 census data, the sun has not broken through the clouds on the New Brunswick demographic landscape. This paper analyzes New Brunswick’s demographic antecedents and proposes a proactive strategic plan for New Brunswick’s sustainable demographic future

Résumé

Les nuages de la tempête démographique se sont accumulés depuis quelque temps. Personne ne peut prétendre ne pas avoir été prévenu que la tempête arrivait. Nous devons tous conclure que nous n’avons pas agi de manière proactive et ciblée afin d’éviter les conséquences désastreuses de cette tempête démographique parfaite. Malgré une certaine lueur d'espoir qui pointe des données du recensement de 2011, le soleil n’a pas percé les nuages au-dessus du paysage démographique du Nouveau Brunswick. Cet article analyse les antécédents démographiques du Nouveau Brunswick et propose un plan stratégique proactif pour un avenir démographique durable dans cette province.

Introduction

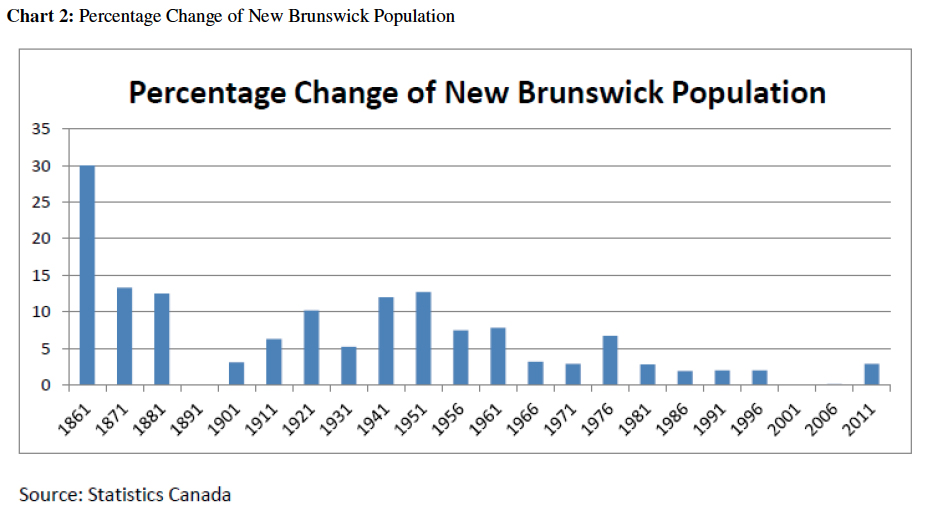

1 In the conventional sense, demography is the study of population profiles, population pyramids, and population projections. In my opinion, it is also a tool that can explain and analyze much more than statistical inferences and population age cohorts. Demography can be a dynamic tapestry of a society’s history as well as its future. Indeed, it can provide an analytical exposé that no other economic or social data can accomplish. In fact, demography can tell the story about where New Brunswick has come from and where it is going.

2 In short, demography is capable of analyzing the past, describing the present, and predicting the future. Indeed, demography can tell the New Brunswick story better than any other discipline and better than any other statistical data or indicators. There is no denying that demography can make a profound and significant statement about the economic vitality, cultural diversity, political profile, and social cohesion of New Brunswick.

Demographic History

3 New Brunswick’s demographic evolution is a revealing account of its economic history, cultural tensions, and social development. It captures the direct relationship between economic development, employment opportunities, and population growth. Indeed, New Brunswick’s demographic history speaks to the transformative pressures on its civil society.

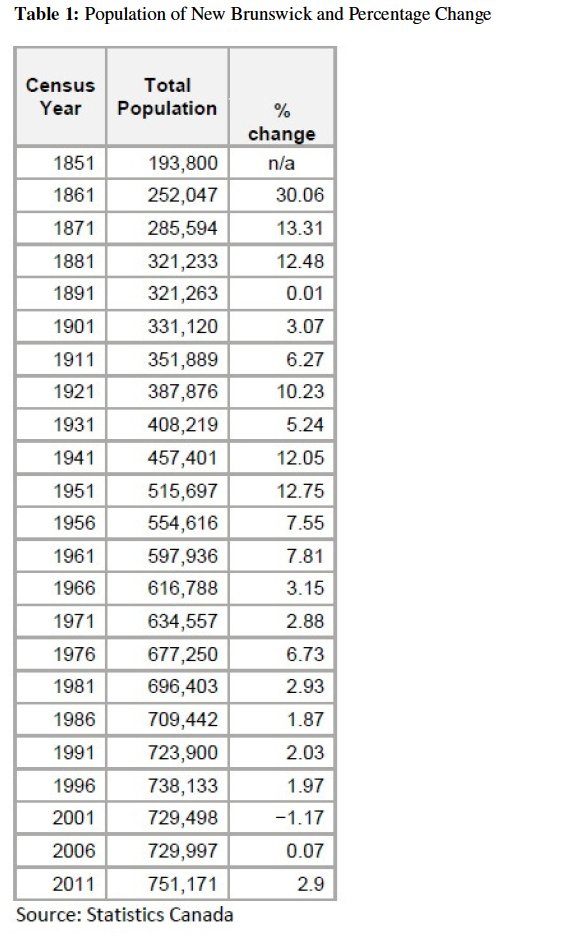

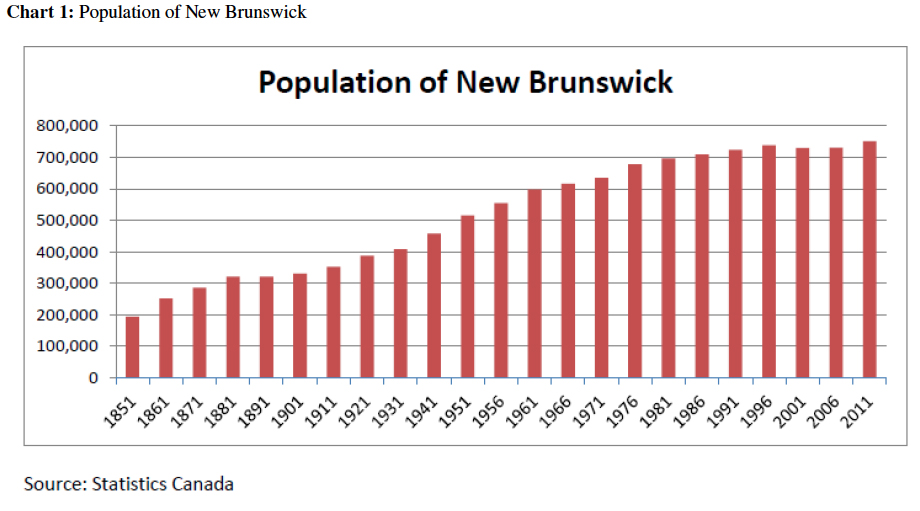

4 Table 1 below and the accompanying two charts provide a vivid illustration of the transformative dynamics of New Brunswick’s population profile. For more than two and a half centuries New Brunswick’s demographic landscape has witnessed peaks of celebratory accomplishments and troughs of spectacular disappointment.

5 New Brunswick’s demographic history reveals a compelling landscape of robust population growth during the decades immediately preceding and following Confederation. Population increases recorded at that time have not been surpassed in any subsequent census period. Indeed, New Brunswick recorded population increases of a stellar magnitude in 1861 (30.06 percent), 1871 (13.31 percent), and 1881 (12.45 percent). This period was followed by a demographic cycle of peaks and troughs that lasted until the end of World War II. More specifically, the peaks of 1921 (10.23 percent) and 1941 (12.05) are in sharp contrast to the troughs in 1891 (0.01 percent), 1901 (3.07 percent), and 1931 (5.24 percent).

6 World War II period. The census data recorded for the post–World War II decades reveal a downward spiral in New Brunswick’s population that is largely attributable to the provincial economy’s lackluster performance in comparison to that of central and western Canada. It also confirms the fact that the hub of economic activity had moved first to central Canada and more recently to western Canada. Indeed, New Brunswick’s status as a “have not” province within Confederation is clearly reflected in its stagnant population profile during the post–World War II period.

Census 2011

7 The 2011 census delivered a combination of good and bad news. New Brunswick’s population grew by 2.9 percent between 2006 and 2011 to reach 751,171. The good news was that this was the highest rate of population growth since 1981. The bad news was that while New Brunswick’s population increase over the last five years was a reversal of demographic fortunes, it was half the percentage increase of Canada’s national average at 5.9 percent.

8 The stars on the New Brunswick demographic landscape were Dieppe, Quispamsis, and Fredericton. In Dieppe the population increased by 25.6 percent, Quispamsis grew by 17.4 percent, and Fredericton added 11.3 percent more residents. The suburban community of Oromocto grew by 6.3 percent. Moncton’s population increased by 7.7 percent and Saint John reversed a decades-long trend of population decline by recording a 2.96 percent increase.

9 It is worth noting that Saint John returned to population growth after a declining spiral that started with the 1981 census. Saint John continues to be New Brunswick’s largest city with 70,063 inhabitants, followed closely by Moncton at 69,074.

10 New Brunswick’s population increase during the last census is attributable to two factors: an increase in international immigration and a decline in the exodus of working-age residents to other parts of Canada and overseas.

11 The 2011 census also revealed a significant shift in provincial demographics in the form of intraprovincial migration from rural areas to urban centres. New Brunswick’s demographic landscape is becoming significantly more urban and suburban. Furthermore, rural communities recorded a pronounced population decline. The pattern of intraprovincial flows resulted in a large number of New Brunswickers leaving rural communities in northern New Brunswick for destinations in the urban centres of southern New Brunswick.

12 The 2011 census confirmed that all three of the largest northern cities experienced persistent declines in their respective populations. Bathurst recorded a 3.5 percent decline, Edmunston decreased by 3.7 percent, and Miramichi recorded 1.8 percent fewer people.

National Comparisons

13 An analysis of New Brunswick’s demographic landscape cannot be conducted in isolation. It must, de rigeur, be compared to and contrasted with national demographic milestones and trends. In this comparative exercise, New Brunswick’s demographic failures are magnified and its successes appear modest.

14 The most recent head count for Canada recorded 33.5 million people, a rate of increase of 5.9 percent since the last census in 2006. Canada’s 5.9 percent growth rate in the past five years exceeds the previous increase of 5.4 percent between 2001 and 2006.

15 Sustaining the growth spurt in Canada’s demographic profile is international immigration, a phenomenon that has become twice as important as natural increase (the difference between births and deaths) in driving the country’s population upward. Only one-third of Canada’s growth is due to fertility. Canada’s fertility rate of 1.67 is well below the replacement level of 2.1, which is a statistical target for maintaining the current level of population.

16 Canada’s reliance on international immigration to fuel its population growth is a trend that has been going on for about a decade due to the rapid decrease in fertility that began in the late 1960s and the increase in the number of deaths due to an aging population.

17 Population projections suggest this trend will continue as the baby boomer generation lapses into demographic history, the result being that by 2031 immigration will account for more than 80 percent of Canada’s overall population growth.

18 It has often been stated that Canada is a country of immigrants and the descendants of immigrants. This observation was emphatically reaffirmed in the 2011 census data. Indeed, two-thirds of Canada’s overall population growth was attributed to the recent arrival of international migrants.

19 New Brunswick’s population increase of 2.9 percent over the last five years was the highest rate of population growth in the last three decades. However, as stated previously, it was only half the national average of 5.9 percent. In this context, New Brunswick is losing demographic ground to the shifting population landscape that favours the central and western parts of the country.

20 New Brunswick’s population increase conformed to the national trend since it was fuelled primarily by immigration. However, recent immigrant arrivals to New Brunswick have disclosed that they face serious barriers to social acceptance and economic integration. In addition, a large number of recent immigrants, after spending a few years in New Brunswick, relocate to Ontario and the western provinces in search of more promising employment opportunities and careers.

21 The exodus of our young people gravitating towards central and western Canada in order to fulfill their job and career ambitions ceased during the period of the last census. In fact, there was a reversal of the historical outflow and a repatriation of young New Brunswickers back to their home province. The most severe and protracted economic recession that Canada has faced in recent times coincided with the time span covered by the 2011 census. Consequently, the return of young New Brunswickers was a feature of the decline in employment opportunities elsewhere. I anticipate that with the economic recovery underway and a return to a booming economy in the west we will witness a significant outflow of our young people during the next decade.

22 At the end of the day, the demographic transfusion that New Brunswick received through international immigration in the five years prior to the 2011 census was simply not enough to make a significant difference to its population size, to maintain its political clout within Confederation, and to empower its economy towards economic development and prosperity.

Political Demography

23 The old adage “politics is everywhere” is even true of demography. There is no denying the important link between population size and political clout. In politics, size matters. This is particularly true for provinces within the Canadian federation. It is reflected in the asymmetric political voice in the federal Parliament designated to different provinces based on their respective population size.

24 The 2011 census confirmed what we have all known for some time. The west is emerging as Canada’s political, economic, and demographic powerhouse. For the first time in Canadian history, the proportion of the population living to the west of Ontario (30.7 percent) exceeds the number of residents living to the east (30.6 percent).

25 The emergence of the western provinces as a population powerhouse will translate into a weaker political voice for New Brunswick. With the future redistribution of seats in the House of Commons, New Brunswick’s political clout will be weaker as a result of the shifting demographics.

26 Under the new federal legislation, recently approved by the Parliament of Canada, thirty new seats will be added to the House of Commons. Alberta, which in the 2011 census led all provinces in terms of population growth with an increase of 10.8 percent, has been awarded six additional MPs in the House. British Columbia will also receive an additional six MPs. The remaining seats in the electoral reform package will go to Ontario, with fifteen additional parliamentarians, and Quebec, with three.

27 All of this places New Brunswick in a political dilemma. The enlarged Parliament will add more central and western Canadian voices. This will undoubtedly result in New Brunswick’s political voice weakening. In effect, the electoral redistribution of seats in the House of Commons will significantly downsize New Brunswick’s political importance on the national landscape.

28 On the provincial landscape, the political power shifts will be in the rural/urban arena. The proposed redistribution of seats in a more compact provincial legislature will reflect the new urban realities of the twenty-first century. As a consequence, the New Brunswick legislature will reflect more political clout for the metropolitan urban centres at the expense of the population-challenged rural areas. This is a recipe for heated political debate regarding the maintenance of public services in rural areas as opposed to investing and consolidating government services to meet the population expansion of the urban centres. At the end of the day, rural legislators will have a diminished opportunity to shape the future course of public policy in New Brunswick.

Urban Magnets

29 New Brunswick is falling in step with the rest of Canada with regard to the allure of urban centres. The population growth of New Brunswick’s urban and suburban centres at the expense of the declining population of rural areas was clearly evident in the 2011 census.

30 Across Canada and in New Brunswick urban centres offer the younger generations employment opportunities, access to educational and health care facilities, cultural amenities, social activities, and, in general, a quality of life that is compatible with their contemporary aspirations. In short, younger workers from rural New Brunswick and immigrants from around the world are attracted to Fredericton, Moncton, and Saint John because of their economic, social, and cultural infrastructure. Simply put, enhanced urbanization in New Brunswick is a result of increased international immigration and a lifestyle choice for the young generation.

31 On the other hand, enhanced urbanization raises a serious fiscal dilemma. At a time when New Brunswick is coming to grips with larger annual fiscal deficits and an upward spiraling public debt, funding public services for ever-shrinking rural communities is starting to lose its political luster.

32 In the final analysis, the allure of New Brunswick’s metropolitan centres may serve as a demographic panacea to retain young New Brunswickers in the province and to curtail interprovincial migration to urban centres such as Toronto, Montreal, Calgary, and Vancouver. The acid test of this observation will be in terms of the interprovincial flows during the economic recovery that is currently underway. The economic downturn meant that New Brunswickers were more likely to stay in their home province. However, the economic recovery in the west may result in an exodus of young New Brunswickers to that part of Canada.

Brain Drain

33 The term brain drain was first introduced to the modern public policy lexicon by Lord Hailsham, Minister of Science in the United Kingdom. In a speech to the House of Lords he said:

34 A similar brain drain is alive and well in New Brunswick. The preceding quote aptly describes the economic development challenge faced by New Brunswick as a result of the exodus of its best and brightest young men and women (along with their accumulated human capital) to other parts of Canada and overseas in search of job opportunities and more rewarding careers. The steady and persistent outflow of young New Brunswickers is our own modern version of the brain drain.

Federal Dependency

35 New Brunswick is singularly dependent on the federal government for equalization payments. The magnitude of those federal transfers in the form of public and private transfers is close to 50 percent of aggregate expenditures in New Brunswick. (During the fiscal year 2010–2011, the New Brunswick government received from the federal government 41 percent of its $8 billion budget. This included federal transfers in the form of equalization payments, the Canada Health Transfer, and the Canada Social Transfer. Since these transfers are tied to the size of the provincial population, a decline in population triggers a commensurate decline in transfer payments.)

36 These federal transfers provide an adjusted revenue stream to support provincial expenditures in the areas of health care, postsecondary education, and social programs. The recently announced revisions in federal health care funding for the provinces delivered a double whammy to New Brunswick. The new formula will provide New Brunswick with less federal transfers for health care due to the province’s declining population, and this despite the fact that the province also has an aging population that is more dependent on health care services.

37 Statistics Canada’s projections for a declining provincial population as a proportion of the Canadian population will adversely affect the amount of federal transfers in the near future. This at a time when projections of the over-sixty-five cohort of the population will increase sharply along with a marked decline in the youth (ages up to nineteen) portion of the provincial population. Statistical projections reveal that New Brunswick’s population is aging faster than the Canadian average. This has immediate consequences in terms of the provincial government’s appropriations for seniors’ social programs, health and hospital care, and long-term care, in effect an increase in hospital costs due to an increased population of persons age sixty-five and older.

Demographic Deficit

38 In its most rudimentary form the demographic deficit is about people. Too few are being born. Too many will be retiring. Most are living longer. Young New Brunswickers are compelled to pursue careers outside of our province. Not enough new immigrants are arriving.

39 New Brunswick’s demographic deficit is about the downsizing of its most valuable economic resource: its human capital. In fact, there is no other single issue that has such direct ramifications on so many of New Brunswick’s hot-button issues than the provincial fault lines in terms of our population size and the consequences of the distortions in the age composition of our provincial demographics. In my opinion, the demographic deficit is cause for greater alarm, and has the potential to trigger even more direct and collateral economic damage, than the fiscal deficit.

40 Provincial population projections clearly confirm that our present demographic outlook will precipitate numerous economic and social consequences. Indeed, our demographic predicament is an economic issue that has a major impact as well as collateral repercussions on a multitude of challenges facing New Brunswick during the next century. If we continue on our present population trajectory we are headed towards the eye of the perfect demographic storm.

41 At the present time our demographic profile illustrates several characteristics that spell economic disaster. Some of those characteristics are the decline in birth rates and the shrinking of the population base; the substantial increase in the number of seniors in our population; the looming retirement of the largest portion of New Brunswick’s population— the baby boomers (those born from 1946–1966); the out-migration of our young people to more lucrative employment opportunities and careers in western Canada; the debilitating labour shortages in numerous trades, skills, and professional occupations; and, finally, our inability to attract a significant number of new immigrants and, even worse, our poor record of retaining them after they come to New Brunswick. All of this presages a population crisis of Herculean proportions.

42 The negative repercussions of our demographic predicament forecast an economy that at best simply sputters along: a decline in tax revenue, reductions in equalization payments from Ottawa, a level of heath care that is considerably worse than what it is today, lack of investment incentives, a shrinking pool of savings, inadequate funding for social programs, and the under-utilization of our economic and social infrastructure. A decline in the size of the labour force will raise wages and salaries and make New Brunswick less competitive and less attractive to new investment.

Sustainable Demography

43 Population growth is much more than the statistical record of an increase in the number of residents living within a defined geographical boundary. It is the ultimate confirmation of economic success, cultural vitality, and social harmony. Indeed, population growth is an indication that we have succeeded in growing our economy, creating new jobs, nurturing entrepreneurship, promoting innovation, attracting investment, and empowering a harmonious and dynamic civil society.

44 I have coined the term sustainable demography to emphasize the need for a proactive public policy approach towards sustaining an appropriate provincial population size that will provide the optimum economic and social contributions. This sustainability requires a new and more contemporary model for population management. Population growth in New Brunswick depends on two components: first, natural increase, the addition to our provincial population through the natural process of the difference between births and deaths; and second, a purposeful and proactive strategy to recruit and retain international migrants in New Brunswick. A corollary to our natural increase process is the retention of our young men and women in the province during their prime working years.

45 To my way of thinking, sustainable demography is much more than maintaining the current size of the population. Rather, sustainable demography embraces three axioms: a steady increase in the size of the provincial population over time; a proactive public policy for achieving demographic objectives accompanied by a renewed institutional governance architecture; and formulating and implementing a strategic demographic plan that includes social and economic objectives for the purpose of ensuring economic growth and social cohesiveness.

Action Plan

46 As I have illustrated, New Brunswick’s demographic future is at a crossroads. The tools and levers at our disposal for arresting our demographic challenges and correcting the demographic deficit are elementary. They include enhancing our domestic population and supplementing it through international immigration. More specifically, they include quantitative demographic tools such as increasing the birth rate, reversing the flow of out-migration, and luring ex-patriots back to their home province.

47 There are also several qualitative demographic tools that can be called upon to play a supporting role in this endeavour. The qualitative list includes enhancing the workforce participation rates of women and other under-represented minorities such as aboriginal peoples; extending or abolishing the mandatory age of retirement; increasing productivity levels so that fewer workers are required to produce the same amount of output; and integrating state-of-theart technology in the form of machines, equipment, and computers that are labour saving and will compensate for the shrinking of our domestic labour force.

48 Let us now turn to each of the two demographic pillars in more detail. First, increasing the population base. This can be achieved by reversing our birthrate, which is significantly below the replacement level at 1.5 births per woman. In short, we need to embrace a direct and indirect pro-natalist public policy. It is a generally accepted principle that direct financial incentives to have more children are ineffective. On the other hand, institutional and public policy initiatives in the form of daycare centres, parental leave, and flexible working hours have had considerable success in allowing young parents to have more children. In essence, what is called for is a family-supportive public policy with the private sector as a full and engaged partner. In New Brunswick, we need to enhance our support for families by strengthening our health care system, supporting childcare workplace support, and investing in education.

49 The second component of population increase is net migration. This includes not only international migration but also interprovincial migration. At the provincial level the demographic balance sheet with respect to migration includes immigration to New Brunswick from international source countries and interprovincial migration.

Natural Increase

50 Of all the countries that have introduced innovative public policy initiatives and financial incentives to increase the number of children per family, no single record matches the success achieved by the government of France. Their success is based on a public policy of engagement, institutional support, and public-private partnership.

51 France’s fertility rate of about two children per woman makes it the only European country with the probability of maintaining its current population through births. France has Europe’s second-highest fertility rate in part because of incentives and family-friendly initiatives offered by its government. These incentives include three-year paid parental leave with guaranteed job protection upon returning to the workforce; universal, full-time preschool starting at age three; subsidized daycare before age three; stipends for in-home nannies; monthly childcare allowances that increase with the number of children per family; and other programs such as the Carte de Famille Nombreuse, or large family card, which provides a mother of three with a 30 percent reduction on trains, and discounts on other vital public services.

52 An econometric analysis conducted by Laroque and Salanie on fertility rates in France concluded that “[o]ur estimation results indeed suggest that family benefits, by reducing the cost of raising children, can have sizable effects on fertility. We estimate the cost elasticity of the demand for children to be about 0.2. To give a rough order of magnitude, politically feasible benefit reforms can change the cost of children by about 25%; thus, according to our estimates, such reforms can move fertility up or down by about 5%” (1).

Immigration Strategy

53 Let me now turn to net migration, the second pillar of population growth. Immigration has been and will continue to be the demographic quick fix. It provides an instant addition to the population. Furthermore, by the very nature of the age composition of immigrants, who are primarily working age, it also contributes a significant infusion to our provincial labour force. In addition, immigrants augment our provincial supply of valuable human capital, skills, and expertise. New Brunswick’s record for attracting international migrants is far below the national average. More revealing is that while one in five Canadians is an immigrant, only one in thirty-three New Brunswickers is an immigrant.

54 Attracting more immigrants to New Brunswick is just the beginning of the demographic journey; making sure that they stay here through welcoming communities and employment opportunities is an equally important aspect of a successful immigration strategy. In this regard, I suggest we need to do the following:

- improve, streamline, and fast-track our provincial nominee program;

- enhance economic opportunities;

- foster welcoming communities;

- build on our linguistic duality;

- provide for settlement and integration support;

- promote public education with regard to the benefits of immigration;

- facilitate the process for the recognition of foreign credentials and overseas work experience.

Over the next two decades international immigration will emerge as a singularly important component and the engine that will drive population growth in New Brunswick. In this context, the provincial government should develop a proactive immigration strategy. This strategy should include three components: first, the cost-effective targeting of country-specific sources of immigration; second, a higher retention rate for immigrants settling in New Brunswick; and third, the successful economic and social integration of new immigrants in New Brunswick. A provincial immigration strategy should have as its overarching ambition to enhance the economic benefits of immigration to New Brunswick and to improve the social and economic integration of new immigrant arrivals to our province.

Multicultural Policy

55 New Brunswick’s demographic correction over the next few decades will rely increasingly on international immigration. The advent of the twenty-first century has confirmed the multicultural composition of contemporary immigration streams. This will require renewing and revising our provincial multicultural policy. One of the significant additions to our multicultural policy should be the recognition of the economics of multiculturalism as a catalyst for achieving provincial economic growth in the context of the new global economy of the twenty-first century.

56 New Brunswick’s multicultural policy was adopted in 1986. The purpose of that policy was to promote the “equal treatment for all citizens of all cultures. It represents a commitment to equality in matters of human rights, in matters of cultural expression and in access to and participation in New Brunswick society” (Province of New Brunswick, “New Brunswick’s” 1).

57 New Brunswick’s multicultural policy is guided by four principles: equality, appreciation, preservation of cultural heritages, and participation. In effect, New Brunswick’s multicultural policy has a decidedly social orientation, the result being that the economic potential of our multicultural human resources have been a sadly neglected feature of our multicultural policy and economic agenda. The pronounced multicultural composition of recent immigrants requires a reexamination of our provincial multicultural policy in order to evaluate its social relevance and economic efficacy.

Multicultural Economics

58 New Brunswick’s contemporary multicultural profile bestows significant economic advantages and benefits. Indeed, as I argued in “The Business of Globalization,” it has a unique economic advantage in strategically deploying its multicultural assets in order to successfully navigate the new global economy of the twenty-first century. There is no denying that the strategic deployment of New Brunswick’s multicultural human resources empowers our province with an economic gateway to the world and with a global competitive advantage. New Brunswick’s cultural diversity can contribute to a unique economic development model and a human resource template that serves as a valuable paradigm for the new global economy. It empowers us with a global awareness for a successful business outreach and profitable economic linkages.

59 Heritage languages and an intimate knowledge of customs, traditions, and religions can contribute to a more prosperous socioeconomic and geopolitical landscape for New Brunswick’s purposeful engagement with the rest of the world. In this context, New Brunswick’s multicultural profile provides us with a global mindset and empowers our province with the skills and competencies for economic success and competitive advantage on the contemporary international landscape.

60 New Brunswick’s multicultural, multiracial, multireligious, and multilinguistic character reflects an economic advantage in such areas as international trade and export potential, overseas business contacts, and income and employment creation. In this context, our multicultural human resources can build international economic beachheads and unlock new opportunities with foreign export markets. Our multicultural demographic character also enhances our attractiveness for foreign investment, tourist appeal, and other avenues of direct and indirect economic benefit.

Trade Advantage

61 New Brunswick’s multicultural human resources can play a vital role in enhancing and improving our province’s international trade potential in the twenty-first century. Multiculturalism can become the key that will enable New Brunswick to increase the number of its trading partners and to diversify its exports. Indeed, multiculturalism can effectively open up new export markets and enhance our competitive edge towards a more universal export potential. About 88 percent of our provincial exports are destined for the USA. This over-concentration on one single export market makes New Brunswick increasingly vulnerable in terms of our economy and domestic employment opportunities. Invariably, an economic downturn in the USA precipitates a decline in New Brunswick’s exports to that destination along with the consequent contraction in employment opportunities and standard of living.

62 An important collateral benefit of trade liberalization has been the availability of new opportunities for foreign direct investment. Foreign investment must play a more important role in New Brunswick’s economic future. New Brunswick’s multicultural communities can act as a catalyst in the process of identifying, encouraging, and facilitating the flow of foreign investment funds into our province. The recent creation of InvestNB must harness this potential in order to attract new foreign investment.

Foreign Credentials

63 One of the most debilitating economic consequences for recent immigrants is the difficulty they encounter with the transfer of their overseas academic credentials, professional accreditation, and work experience. In an age when human capital is the single most important ingredient for success in the global economy, there is a disconnect between our federal immigration policy and New Brunswick’s record in the economic integration of recent immigrants.

64 The disconnect takes the form of a lack of speedy recognition of foreign academic credentials, professional licences, and professional diplomas granted overseas. More precisely, prospective immigrants are selected overseas on the basis of their postsecondary credentials and professional affiliation. However, upon arriving in New Brunswick they are confronted with obstacles to having their academic credentials accredited, some facing overt and covert barriers in seeking entry to the regulated professions in New Brunswick.

65 At the present time there is an economic disconnect between overseas immigrant selection and labour market integration. Consequently, we need a new institutional architecture that will resolve the impediments and barriers to the efficient and effective integration of immigrant labour into the New Brunswick economy.

Demographic Architecture

66 I have come to the conclusion that our current institutions of social and economic governance were designed to deal with the challenges and opportunities of the twentieth century, thus have proven to be inadequate for governance and public policy in the twenty-first century. We therefore need to adapt, retool, or create new governance institutions that are more appropriate and effective for the challenges and opportunities of the twenty-first century.

67 One such experiment took place in New Brunswick with the creation of the Population Growth Secretariat on 1 April 2007 (Province of New Brunswick, “Towards”). It was the provincial government’s response to decades of population decline and the impotence of the existing institutional machinery to address this problem in a purposeful and effective manner. The Population Growth Secretariat was created to reverse the decline in population and grow New Brunswick’s population. The mandate of the secretariat was to be proactive in terms of accomplishing sustained population growth. Indeed, it was one of those rare glimpses of government institutions taking on a proactive role instead of the more conventional reactive role of fighting daily public policy fires.

Population Aging

68 The pending retirement of the biggest age cohort in recent memory, the baby boomers, provides significant challenges for New Brunswick’s economic and social landscape. Those challenges include workforce shortages, the increased demand for health care, sustaining our social services, maintaining our old-age pensions, and ensuring an adequate level of income security for our retirees (Busby et al.).

69 Our demographic challenges require a major change in public policies as well as social attitudes. What is required is nothing short of a transformative attitudinal change from the perception that aging is a period of dependency and inactivity to that of a new phase of contribution and social and economic participation. In short, New Brunswick should redefine the role of the aging population in our society and set up the institutional architecture to harness the significant contributions of our seniors. New Brunswick is tied with Nova Scotia as the second-oldest jurisdiction in North America among the sixty U.S. states and Canadian provinces as measured by median age.

Social Sector

70 Economists are trained to confine the absorptive capacity of human resources between only two sectors of the economy: the private sector and the public sector. The emergence of the social or voluntary sector has in fact transformed the labour landscape into a three-dimensional forum. Indeed, the social economy has emerged as an important component of the transformational change precipitated by the twenty-first century.

71 There is ample evidence to suggest that the fiscal constraints of the public sector have elevated the importance of the social economy on the economic agenda. New Brunswick should therefore develop a comprehensive and coherent strategy for harnessing the full potential of our social sector. Indeed, the social economy can fill a void in services for the public good. There is no denying the important contribution and mission of those social providers to the process of economic, cultural, social, and environmental value-added creation.

Mandatory Retirement

72 At the present time, New Brunswick’s mandatory retirement is an obstruction that magnifies our demographic challenges. Abolishing or extending mandatory retirement is not a demographic solution. Abolishing or extending mandatory retirement, as many other Canadian provinces have done, will give us more time and breathing space for corrective demographic action to kick in. It will also increase economic capacity at a time when we need it the most.

73 Abolishing or extending mandatory retirement is simply a Band-Aid solution that will offer an immediate reprise from the serious consequences of a shrinking population. New Brunswick would not be breaking new ground in abolishing mandatory retirement at age sixty-five. There is a long list of provinces and territories—including Manitoba, Alberta, Quebec, Prince Edward Island, Nunavut, the Yukon, and the Northwest Territories—that have already abolished it.

74 Of course, abolishing or extending mandatory retirement beyond the current retirement age of sixty-five will require new provincial legislation, the concurrence of the private sector, and due diligence to existing pension plans.

75 Employers need not be overly concerned, for statistics confirm that the vast majority of older workers opt for retirement even where mandatory retirement has been eliminated. As Peter Hicks has shown, maintaining a portion of the complement of senior workers as active and producing agents in light of the current demographic environment and the demands for human capital, skills, and expertise of the knowledge economy makes good sense.

Conclusion

76 New Brunswick is headed for the eye of the perfect demographic storm. Our multifaceted demographic challenges must be confronted in a purposeful and proactive manner. We need a strategic demographic plan that will reverse the downward trend in natural increase and enhance New Brunswick’s share of international immigration. Population growth is the foundation stone upon which New Brunswick’s economic development will be achieved. Our action plan must embrace a strategy for sustainable demographic growth in order to eliminate the current demographic deficit.

Constantine E. Passaris is Professor of Economics at the University of New Brunswick and a Research Affiliate of the Prentice Institute for Global Population & Economy at the University of Lethbridge.