Articles

Gender Equality in Sports -

A Human Rights Lawyer's Perspective

Abstract

This paper analyzes gender equality in university sport programs through the lens of human rights legislation. It queries if and how the cause of gender equality in university sports might be advanced through the use of legal mechanisms and institutions charged with the administration and enforcement of human rights guarantees. The decision of the University of New Brunswick to cancel its Women's Hockey Varsity Team and a faculty policy on gender equity form the factual matrix of a case study that demonstrates how sports administrators may achieve or defeat gender equality in university sports. This study concludes that gender equality in sport trails the advance of that goal in other social spheres, rendering institutions and individuals vulnerable to legal liability. The paper provides an analytical framework that would manage this vulnerability.

Résumé

L’exposé analyse l’égalité des sexes dans les programmes de sports universitaires selon la législation sur les droits de la personne. Il propose de comprendre dans quelle mesure et de quelles façons la cause de l’égalité des sexes dans les sports universitaires pourrait être avancée grâce au recours de procédures juridiques et d’institutions chargées de l’administration et du renforcement des droits de la personne. La décision qu’a prise l’Université du Nouveau-Brunswick – soit celle de mettre fin à sa ligue universitaire de hockey pour femmes - et la politique universitaire sur l’égalité des sexes fournissent le contexte factuel d’une étude de cas qui montre à quel point les administrateurs du domaine sportif pourraient atteindre ou non l’égalité des sexes dans les sports universitaires. La conclusion affirme que l’égalité des sexes dans les sports accuse un retard par rapport aux autres sphères sociales, rendant ainsi les établissements et les personnes vulnérables à la responsabilité légale. Cette étude fournit un cadre de travail analytique qui permettrait de gérer ce risque.

1 On 12 March 2008, the University of New Brunswick announced the down-grading of its women's varsity hockey team to club status. The change was part of a larger restructuring of the competitive sports program at the university, but it attracted singular attention because it was the only element of the restructuring that caused a team to lose its ability to compete at the previously established level. In an era when women's hockey seemed to be on an unstoppable rise, the decision caught many in the university and broader community by surprise. 1 Soon there was discussion on campus and in the local media about what response, if any, should be mounted to the decision. Letters to the editor raised the question whether a new legal regime was required to protect female athletes from discriminatory decision-making. Commentators suggested the adoption of U.S. Title IX-style legislation or invoked the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to advance a moral claim in search of a legal basis. 2 University representatives provided editorial opinions to the local press explaining the position of the institution. According to one op-ed, the decision had not been made on discriminatory grounds but for fiscal reasons, that the gender equity policy applicable to CIS sports had been respected and that women and men were on an equal, non-discriminatory, footing in the UNB athletics program. 3

2 Ultimately, some of the individuals directly involved in the women's hockey team filed a complaint with the New Brunswick Human Rights Commission, and the university is defending the complaint. That complaint is pending before the Commission and will be dealt with in the provincial human rights process in due course. 4 This is will ultimately resolve the legal issues involved. However, there are broader questions this course of events raised in the province about the nature of discrimination and its relationship to financial decision-making, the applicability of existing legal regimes, and their (in-)adequacy. Using the standards of Canadian and New Brunswick human rights law, this paper will show how these standards can be used to advance gender equality in sport and how institutional interests in financial planning and autonomous decision-making receive recognition in some contexts, while they give way to equality demands in others. Before delving into these issues, let me consider some context and historical background.

3 Sport is one of the remaining vestiges of gender segregation 5 in Canadian society. While institutions like universities, professions, and even the police, the military and, to a lesser degree, the skilled trades, have become desegregated, sport institutions, funding models and event organizers have clung to strict gender segregation in almost all contexts. Sport has therefore become not only a social location in which gender norms are being reinforced and promoted, 6 but a location where discriminatory gender segregation is being defended against an increasing, possibly overwhelming, social consensus of gender equality in most other social arenas. Like many other social constructs facing opposition and requiring justification, gender segregation in sport has become entrenched, and claims are being made in an increasingly politicized environment. 7

4 It is therefore not surprising that gender segregation and gender inequality in sport have faced some litigation since the late 1970s. 8 It appears that women who are used to being heard in their demands for equality, and who have experienced considerable advances in other areas, are no longer as easily put off when they are faced with discriminatory practices, attitudes, and policies in the sport context. As well, progressive sport governance participants such as coaches, event organizers, and league officials have on occasion attempted to advance the equality interests of athletes under their tutelage or control. Despite this, there has been but modest movement towards gender desegregation and away from gender discrimination against female athletes, be they children or adults.

5 This paper does not seek to explain why gender discrimination persists in athletics. Instead, it singles out a particular policy related to gender equity in sport and asks how the policy interacts with legal norms applicable to it. From this analysis, the paper seeks to glean an understanding of how administrators in sports perceive their equality obligations and how this perception compares to the demands made of them by human rights law.

6 The paper analyses UNB's “Gender Equity in Sports” policy, the policy cited by the university in defence of its cancellation of the women's varsity hockey team. The purpose of the analysis is not to single out UNB or the policy of the Faculty of Kinesiology. 9 The purpose of the policy was not originally seen as defensive. Instead, it was understood as a welcomed statement of principle designed to advance gender equity in UNB university sports and sports administration. It therefore provides a ready measure of an institutional response to gender inequality outside of a litigation context. Further, it allows us to identify a single legal standard that is applicable to the policy, i.e., New Brunswick anti-discrimination legislation. 10 Flowing from the analysis, the paper draws attention to the obligations facing kinesiology graduates in their potential future careers both within and outside the provincial public education and health systems. It also queries to what extent universities need to lead by example in issues of gender equality in sport as a risk management strategy to protect their graduates from future involvement in human rights litigation and to protect the institution from similar exposure. The paper concludes that there is an institutional obligation not only to promote gender equality in sport but to educate kinesiology students in the process of appropriately recognizing, addressing, and responding to continued gender discrimination. I am hoping that this paper will contribute to meeting this obligation. 11

7 Let me begin by setting out the legal context in which university policies operate and the standard against which the policy must measure up in order to conform to human rights law in the Province of New Brunswick.

8 It is well established that universities are sufficiently far removed from government to be outside the ambit of obligations arising from the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. 12 Therefore, the policies of universities are not subject to the equality guarantee of s. 15 of the Charter. Instead, universities are actors whose conduct is reviewable on human rights grounds by human rights tribunals (and, less commonly, by the courts) in their capacity as employers, providers of housing, contracting parties as well as, most relevantly in the present context, service providers. By virtue of s. 5 of the Human Rights Act, 13 human rights legislation in New Brunswick, consistent with other Canadian jurisdictions, applies only to those services that are available to the public. The reason for this requirement is that human rights legislation should not restrain the purely private acts of individuals, such as a personal choice to invite people to a party while applying racial criteria for the invitation list.

9 Universities have attempted from time to time to bring themselves under this private act exception by arguing that a particular service is not generally available to the public because they are subject to eligibility criteria or mitigated by freedom of contract. These attempts were initially successful for both academic and athletic contexts, but since the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Berg, universities have been unable to avail themselves of this line of argument. 14 The Berg decision is the highest authority on what it means for a service to be available to the public. Berg dealt with the right of a graduate student to equal treatment and accommodation of her mental disability. While the facts in Berg are removed from the issue of gender equality in sport, the development of the law to this point is very much apropos. Prior to Berg, the Supreme Court in Gay Alliance 15 had interpreted the "public" requirement stringently so as to deny advertising space to a gay rights organization in a newspaper, arguing that the assignation of advertising space was not a service generally available to the public. Following the Gay Alliance case, the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal refused to extend human rights protections to students wanting to participate in a university varsity team in Beattie. These cases were applied by the Ontario Court of Appeal in a case involving Debbie Bazso, a nine-year-old girl who wanted to participate in the baseball play-offs as a member of a boys' team. A majority of the Court concluded that the softball association did not offer a service generally available to the public, so a denial of playing on the boys' team was not subject to human rights scrutiny. 16 Importantly, Wilson J.A. (who would go on to be the first woman on the Canadian Supreme Court, but who was sitting as a judge of the Ontario Court of Appeal in this case) wrote in dissent and would have supported Debbie's right to play on the boys' team. She noted that the softball association was not a private club and that it was open to the legislature to make an exception for sports, but that it had not exercised that option. In Berg, the Supreme Court adopted the reasons of Justice Wilson and overruled Beattie and Gay Alliance. The Court notes:

10 Despite this considerable advancement in the law at that time, the Supreme Court of Canada in the Berg case specifically left open the possibility that some services undertaken by university employees would in fact fall under the exception.

11 The door is therefore not completely closed on the argument that not all campus activities are reviewable on human rights grounds. Despite this, it is important to note that the exception does not relate to the university and its agents, but instead to individuals who also happen to be representatives of the university. For example, if a janitor challenges a group of male students to a game of pick-up hockey, the relationship between the janitor and the students is properly characterized as private, even though the janitor is an employee and the students are being provided with services by the employer of the janitor. University policies, by contrast, are indisputably public and their application is therefore reviewable. In sum, following Berg, all services offered in a university institutionally are services available to the public sufficient to attract human rights scrutiny, while recognizing that individuals who are part of the academic communities also form other, non-institutional, and therefore essentially private, relationships.

12 The result in Berg is also the law in New Brunswick. University services are broadly considered public. Even prior to Berg, the New Brunswick Court of Queen's Bench had recognized that a university cannot discriminate when it rents out premises to organizations. 17 Sport programs are not excepted, as is evident from the fact that UNB made arguments in line with Beattie and Gay Alliance in the Sahyoun case, supra, dealing with varsity soccer and was unsuccessful before the Labour and Employment Board.

13 The policies and practices surrounding university sport are therefore subject to human rights legislation. This means that in athletic programming, universities in New Brunswick, as elsewhere, may not discriminate on grounds prohibited by human rights legislation. While there are some differences in the list of prohibited grounds, the list in all provinces includes sex and/or gender.

14 The policy under review recognizes and affirms this obligation. It provides that the "Faculty of Kinesiology is committed to gender equity in the administration, policies, programs and activities of the Intercollegiate Athletics Program at UNB." It goes on to define gender equity as requiring "that male and female athletes, staff members, and administrators, shall not be treated differently because of their gender."

15 Human rights legislation sets the floor in terms of human rights standards; institutions may elect to promote human rights including gender equality above the legislated standard, but not below it. If the institutional standard meets or exceeds legislative human rights standards, human rights adjudicators will find the policy to be non-discriminatory, whereas a policy that falls short of the legislative standard will be discriminatory. Considered from this perspective, the definition has both positive and problematic aspects. On the positive side, it includes staff and administrators as relevant groups to consider in the process of achieving gender equity. A comprehensive target group that includes leadership positions is helpful because it has long been recognized that discrimination affecting positions of leadership has profound effects on everyone else in a program. 18 On the other hand, it is problematic that equity seems to be defined as amounting to no more than avoiding differential treatment.

16 Since the early days of Canadian Charter anti-discrimination law, courts have recognized that formal equality, i.e. treating like people alike, was insufficient to achieve equality. 19 Instead, the Supreme Court of Canada has struggled to define the hallmarks of substantive equality, that is, to create the conditions in which people are afforded individual consideration in light of their personal characteristics, abilities, and challenges and are enabled to participate in society on a level playing field while permitting society to create programs and policies to advance communal interests. It is probably fair to say that this struggle has not come to a satisfactory conclusion, but despite this, it is clear that formal equality is not the measure. 20 At the very least, equality must include a mechanism for overcoming historical or innate disadvantage. The locus classicus of the failures of formal equality is Aesop's fable of the “Fox and the Crane,” where a fox invited a crane to supper and offered soup on a plate. The Crane could not get at the soup because his bill was not suited to eating from a plate. The Fox laughed at him. Later, the Crane returns the hospitality by offering the Fox meat in a long-necked vase. The tables are turned. 21

17 Treating everyone the same does not necessarily mean that everyone will be satisfied, nor does it mean that the treatment cannot amount to discrimination. A competing, and preferable, view of gender equity in sport is therefore advanced by the NCAA Gender-Equity Task Force's definition: "an athletics program can be considered gender equitable when the participants in both the men's and women's sport programs would accept as fair and equitable the overall program of the other gender." 22 Even this definition falls short of equality demands in Canadian, and New Brunswick, human rights law. A subjective test applied by individuals who have been exposed to the status quo for a considerable period of time may well serve to uphold even a discriminatory status quo. Instead, the legal equality demand has two branches: does the program or policy treat men and women alike? and does the program or policy accommodate disadvantaged groups to the point of undue hardship? The relationship between these two demands is not one of alternatives. A program or policy that fails to accommodate in the formulation of its criteria (and not merely in their application) is discriminatory. To express this idea, courts have distinguished between direct and adverse effect discrimination, 23 and have subsequently insisted that both be subjected to the same equality demand. 24 Direct discrimination involves a rule that makes express distinctions on the basis of a prohibited ground. For example, the rule that required hockey-playing twins Amy and Jesse Pasternak to join the girls' team because their high school had a girls' team was direct discrimination in that it treated them differently than their male classmates because they were girls. 25 Adverse effect discrimination involves the application of a rule that is neutral on its face but which has a negative effect on individuals protected by a prohibited ground of discrimination. When Tammy McLeod wanted to compete in bowling but was not allowed to use an assistive device, a ramp, in the process, the facially neutral rule requiring manual control and propulsion of the ball had a discriminatory effect on her as a person with cerebral palsy. The rule was therefore found to be discriminatory and illegal. 26 Amy, Jesse, and Tammy therefore established that the comprehensive scheme of substantive rules of anti-discrimination law in Canada apply in sport, at least at the level of individual treatment.

18 These conclusions are neither obvious nor universally welcome. The very public dispute over the Pasternak case illustrates two common concerns. First, by permitting girls to play on (or, at the very least, try out for) teams previously reserved for boys, girls’ teams might become vulnerable to takeover bids by boys who did not make the boys’ team. Second, it would deprive emerging girls’ teams of their best potential players. The first argument is a good example of the conversion of a substantive equality argument into a formal one. Under a formal equality approach, what is good for the goose must be good for the gander, i.e., if it is a violation of human rights law and principle that girls are excluded from boys’ teams, it must equally be a violation when boys are excluded from girls’ teams. Despite its surface appeal, this argument is ultimately unsupported by human rights law because it ignores the historical and present social context in which these decisions of exclusions are made. As set out earlier, gender segregation can be used for the ameliorative purposes of achieving rather than defeating human rights guarantees and if so used, is defensible from a human rights perspective. The second argument is more complex and less easily disposed of on principle. If supporting girls’ teams is consistent with human rights principles—and I have just argued that it is—does it not follow that girls’ teams should be supported by giving them preferred or even exclusive access to the best player pool? This argument was rejected in the Pasternak case, but not because such concerns could never support an adverse ruling on individual rights. Rather, there was no evidence before the tribunal to support the claim that promoting individual rights had operated to defeat the collective interest in comparable situations. Ultimately, the question whether women in sport are less likely to experience discrimination in a segregated or desegregated system is a question of fact. In the absence of proof to the contrary, however, human rights adjudicators are wary of separate-but-equal schemes and will presume that desegregation is less discriminatory. Even if segregation is accepted (either because it is deemed to be ameliorative or because desegregation would impose undue hardship), proof that the scheme is substantively and not merely superficially equal will be required. 27

19 In sum, as a result of these cases, human rights law imposes two obligations on service providers: the obligation to avoid differential treatment and the obligation to avoid adverse effects. Both obligations apply in the context of organized sports in universities.

20 Let me return to UNB's Gender Equity Policy (Policy) to determine how the Policy measures up against these dual demands. The Policy sets out three goals. Each goal is described in a statement followed by steps to be taken to achieve the goal. The goals relate to administration, 28 treatment of athletes, 29 and student experience. 30 Each goal statement is immediately followed by a statement "recognizing" barriers to the achievement of the goal. For example, for goal #1, the objective is explained as achieving "gender equity in all aspects of the Intercollegiate Athletics Program." It is immediately followed by a statement that "it is recognized, however, that certain pragmatic conditions may impede progress towards this goal; such as the availability of qualified female coaches willing to take on part-time work, the limited number of female full-time coaches presently in the program available for committee-work [sic], the hosting of specific AUAA tournaments, and so on." It is unclear from the statement itself whether the intent is to justify slow/imperfect progress or to identify obstacles so that they can be removed. From a human rights law perspective, it is welcome that a policy maker would identify issues that might stand in the way of human rights compliance. In that case, one would expect that the implementation part of the policy would address ways of overcoming the previously identified obstacles. The other way of understanding the statement is to flag that the goal will likely not be achieved, but that there are reasons that would mitigate the human rights obligation.

21 For example, an employer might have a policy that provides for the hiring of individuals with disabilities at the rate of societal prevalence. Let us assume that all positions within the purview of the policy require Grade 4 literacy for safety reasons. The policy states that individuals with intellectual disabilities will be hired only if they can demonstrate Grade 4 literacy and that this might result in a hiring below societal prevalence. In human rights law, these mitigating factors are referred to as BFOQ, which stands for bona fide occupational qualification. If an ability is a true requirement of certain employment and the applicant/employee cannot be accommodated without causing the employer undue hardship, then the person may be refused the position or may be terminated without amounting to discrimination. So if it can be demonstrated that adequate safety warnings cannot be conveyed in pictograms or that the cost of new signage would be prohibitive, there is no discrimination.

22 In this sense, the shortage of female coaches or the hosting of AAUA tournaments might be argued to be limits that should justify what would otherwise be discriminatory conduct in the provision of a service. There are two legal difficulties with this argument: first, the justification that a policy or criterion is not discriminatory despite its differential effect because it is a bona fide occupational requirement (BFOQ) is limited to the sphere of employment under the Act; and second, even if BFOQ applies, the burden of proof is on the employer to demonstrate that the limit it imposes is truly necessary and that it would cause it undue hardship to accommodate the equality-seeking individual.

23 The equality obligations of an employer at the hiring stage are limited to the available applicant pool. For this reason, an employer who has not created barriers in the hiring process and who receives applications only from males does not act discriminatorily by hiring a male. However, an employer who chooses to hire five males and no females out of an applicant pool of ten men and ten women will have to justify why they hired exclusively (or predominantly) men. The justification may not be in itself discriminatory. For example, the justification that the employer perceived the males to be physically stronger would not provide a defence unless the employer has individually tested the applicants for physical strength and can demonstrate that the level of physical strength shown by the female applicants was inadequate for the true requirements of the job after accommodative measures (such as the use of a tool, machine, or assistive device).

24 For the purposes of the Policy, it cannot therefore be said that a shortage of female full-time coaches available for committee work represents a barrier to gender equity in the administration of the Intercollegiate Athletics Program unless it can either be shown that the applicant shortage is itself the result of discriminatory practices (e.g. a sexist job ad) or that the program cannot be administered in a gender-equal manner unless there is gender-equal recruitment. It appears that the latter scenario might have concerned the policy maker. The Policy provides in 1 (c) that "all committees concerned with the hiring of program personnel must have equal numbers of male and female members." However, unless there are sufficient female members available for committee work, either all females who are available for committee work will have to serve on hiring committees or gender balance will not be achieved there. The Policy therefore admonishes hiring committees to be pro-active in striving to achieve gender equality in hiring.

25 This approach is problematic from a human rights perspective for the same reason that the introductory definition of the Policy was problematic: it remains committed to a formal equality doctrine and acts to restrict rather than create opportunities for equality. One of the advantages of accommodation analysis is that it engages the creativity of stakeholders to find methods for advancing equality in situations of inequality.

26 By contrast, formal equality tends to reify existing inequalities as the result of some pre-existing, frequently biologically deterministic restraint. Viewed from the perspective of accommodation, one might ask what steps the Faculty of Kinesiology might take to make itself the employer of choice for female full- and part-time coaches. The Faculty as the educational institution of a future applicant pool is in a much more favourable position than most employers to achieve this. One might further ask what modifications in the job description and allocation of workload might enable women coaches to participate more actively in committee work.

27 This very creativity can be defeated by a formal equality approach. For example, in 1 (f) of the Policy, the Faculty commits to "every effort to ensure that there is gender equity in all positions, terms of responsibility, salary levels, benefits and opportunities for advancement, for the staff members of the program." By treating all members the same, the Faculty has effectively precluded any resort to the advancement and empowerment of female staff to correct historical disadvantage. A male staff member would be well within his rights under the Policy to complain if his claim for advancement was overtaken by a female colleague, even if the advancement of the female served the Policy objective of making more full-time coaches available for committee work.

28 Let me pursue the difference between formal equality as envisioned by the Policy and substantive equality as demanded by human rights law with one more example, this time in the area of treatment of athletes. The Policy introduces the goal of gender equity in the treatment of athletes followed by a reference to the tiered nature of financial support and provides that the comparator analysis should proceed within each tier. It also creates a funding exception where differential funding is required by the cost of safety equipment/regulatory compliance. Again, the reference deserves careful analysis.

29 Under the Policy, the decision to create and perpetuate tiered funding precedes the gender equity obligation. In other words, if the decision to introduce tiers is itself discriminatory, the Policy will not address this because it proceeds on the assumption that tiers are an immutable component of the program. It will have become apparent that the reification of difference as inherent or immutable is one of the chief mechanisms by which formal equality can operate to undermine, despite the best intentions of participants, substantive equality claims. For this reason, elements of decision-making that are excluded from the analysis should attract particular attention.

30 Recall that a decision, policy, or structure must not have an adverse effect on equality-seeking groups in order to pass human rights muster. It is not necessary that the decision, policy, or structure was designed for the purpose of discrimination. The existence of such a purpose would, of course, immediately offend human rights law, but its absence is not determinative of discrimination.

31 The test case is whether a tiered system can meet the requirements of the Policy and be discriminatory in its appearance or in its effect.

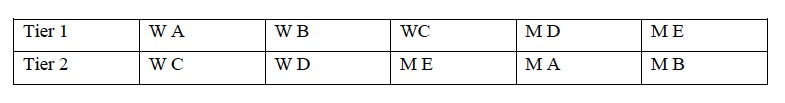

32 The funding rules under the tiered system of the Policy are set out in a somewhat complex manner, but they can be summarized as follows:

- Within each tier, number of women's teams = number of men's teams +/- 1

- Within each tier, Women's Sport A = Men's Sport A

- Total number of participatory opportunities for women = total number of participatory opportunities for men (number of women as a percentage of UNB undergraduate students = as a percentage of UNB undergraduate students +/- 15%)

33 Let us consider a simple tier structure with ten teams of fifteen members each and two tiers. Let us assume that there are equal numbers of men and women undergraduates. Finally, let us assume that Tier 1 sports attract 100 units of funding and Tier 2 sports twenty units of funding. Each sport is designated A-E and men's teams are designated M, while women's teams are designated W.

34 It is easy to see that the above table complies with the funding rules. In Tier 1, we have one more women's than men's team, while in Tier 2, we have one more men's than women's team. Both are within the one-team tolerance of Rule 1. Since the sports are segregated in the tiers, by definition they meet Rule 2. As team size and the number of teams are identical, Rule 3 is met. Under this scenario, women receive 340 units of funding while men receive 260 units of funding. The disparity arises because of the one-team tolerance in Rule 1 and is larger if the funding difference between tiers is greater. It becomes smaller if there are more teams. This demonstrates that a funding model that not only does not intend to discriminate on the basis of gender but seeks to eliminate discrimination can still result in significant discrimination if elements of the decision-making process are sequestered from the discrimination analysis.

35 This form of adverse effect discrimination is sometimes described as systemic because it operates through mechanisms that do not depend on discriminatory attitudes of system participants. What are the demands that human rights law makes on program designers and funding allocation when it comes to sport, within and outside of universities? The first observation is that separate-but-equal schemes do not meet the standard. Even beyond the tiering decision, there is an important precursor decision, held with near universality in organized and competitive sports, that gender segregation is inherent in sports.

36 Teams are frequently open to one gender only and are therefore facially discriminatory. In writing this, I am well aware of the degree of reification of gender difference in sport. The law demands that teams be open to men and women alike unless women's teams are designed as ameliorative programs to address group disadvantage. This means that while all men's teams (so-called) must be open to women, the reverse does not hold true. Further, gender-segregated rules for sport disciplines are discriminatory, and institutions supporting gender-segregated rules engage in discrimination.

37 Why would kinesiology students care about these issues? Beyond a likely desire to be doing the right thing, there are significant risks deriving from a failure to comply with the legal rules of non-discrimination. Students are at risk of being sued in future careers. Damages awards in service cases before human rights tribunals tend towards the lower end of the scale, but the process itself is expensive for respondents. It usually requires legal representation, and an average human rights hearing takes several days. Human rights cases involving systemic issues tend to be measured in weeks and months, not days.

38 Compliance with the institutional policies of employers does not immunize respondents from liability, and while employers are vicariously liable in civil courts for the tortious acts of their employees, the same is not necessarily true for human rights cases. 31 It is trite that the first stage of risk management is risk identification, and an awareness of the legal demands of equality—be they related to gender, ethnicity, or disability—is crucial for this initial stage. The exact scope of the risk varies between jurisdictions, in large measure because most jurisdictions in Canada, including New Brunswick, have adopted a purely reactive, complaint-based human rights regime. This means that the risk does not materialize until someone affected by human rights violations takes active measures to initiate a complaint. However, some jurisdictions, notably Ontario, have equipped their human rights commissions with the power to initiate human rights investigations of their own motion.

39 Equality law is still very much evolving. The past five decades have seen a development away from a perpetrator-focused system of prosecutions that was interested in the intentions of those engaging in discriminatory acts or practices, moving first towards a victim-focused complaints system that recognized the irrelevance of intentions and redirected attention to effects and outcomes. Even more recently, we have come to recognize systemic effects through analyses that are centred neither on perpetrators nor victims, but instead contribute to identifying and removing barriers in institutional and societal settings where they become an engine for social change.

40 In my legal practice as a human rights lawyer prior to taking on an academic appointment, I was often struck by the time lag in public perception of human rights in spite of the rapid development of the law in this area. This was also true for the UNB women's hockey dispute as reported in the media. 32 Much of the discussion of the women's hockey decision on the part of the university revolved around two assertions: the decision was not motivated by discriminatory attitudes against women athletes and these kinds of decisions are the tough decisions good managers have to make from time to time, in compliance with intra-institutional policy. Public advocates for the women's team, by contrast, alleged discriminatory attitudes reaching back into the early days of the team and went in search of an applicable basis for review. Both sides appeared to me to be relying on the prosecutorial, intentionalist approach abandoned by human rights law decades ago, and they did not engage with the commands of substantive equality. Interestingly, both sides had resort to arguments related to systemic discrimination, but they tied them firmly into the intentional model.

41 From the university’s perspective, the fact that the Policy adopted a systemic view of the funding model, as described above, immunized it from review, not because it precluded the existence of systemic discrimination but because it demonstrated the good faith of the institution. From the team's perspective, the historical disadvantages imposed on the team in terms of recruitment, scholarships, team support, etc. demonstrated the university's discriminatory attitude.

42 Ultimately, good faith alone will not be sufficient for the university to defend the claim. And while a demonstration of bad faith would be sufficient for the team to succeed in their complaint, it is extremely difficult to prove in most cases, and nothing in the public discussion suggested bad faith. Therefore, it is likely that the focus of the human rights investigation will not be the supposed good or bad intentions of the parties. Instead, the human rights process will require a demonstration that the university's decision was non-discriminatory because it was consistent with its substantive equality obligations. In this, the Policy will not provide the kind of assistance advanced by the university's public statements. Its focus on formal equality and its propensity for built-in justifications for ongoing gender inequality, as well as its room for systemic biases, render it vulnerable in the context of the hockey litigation.

43 Sport organizations and administrators are easy targets for human rights litigation because there are few other social locations where gender segregation and gender discrimination are so overtly practiced. On the other side of the coin, there are few arenas where positive change can be effected as easily. And the move towards equality is frequently experienced as transformative, not only to those faced with gender discrimination but to all system participants.

Jula Hughes is Associate Professor, University of New Brunswick Faculty of Law.