Invited Essays

“I want to know my bloodline”:

New Brunswickers and Their Pasts

Abstract

New Brunswick is a product of wars fought from 1689 to 1815. During these wars, all of which included battles on North American soil, the social relations among the First Nations, French, and British inhabitants were forged, often in blood. These conflicts became the foundation for mutable but seemingly mutually exclusive identities that are documented in a recent survey of New Brunswickers on how they engage the past in their everyday lives. In this paper, we describe the eighteenth-century context in which many New Brunswick cultural identities were constructed and address the findings of the Canadians and Their Pasts survey in a province where popular engagement with history is complicated by diverse perceptions of the past.

Résumé

Le Nouveau-Brunswick est le produit de guerres ayant eu lieu entre 1689 et 1815. Pendant ces guerres, qui ont toutes eu des batailles en sol nord-américain, des relations sociales se sont tissées entre les Premières nations, les Français et les Britanniques; souvent, ils étaient unis par les liens du sang. Ces conflits sont à la source d’identités mutables, mais qui étaient, en apparence, mutuellement exclusives et qui ont fait l’objet d’une récente enquête qui portait sur les gens du Nouveau-Brunswick et sur la façon qu’ils évoquent le passé au quotidien. Dans cet exposé, nous décrivons le contexte du 18e siècle dans lequel de nombreuses identités culturelles du Nouveau-Brunswick se sont formées et nous nous penchons sur les résultats du sondage portant sur les Canadiens et leur passé et ce, dans une province où l’engagement populaire envers l’histoire se complique par les diverses perceptions du passé.

Introduction

1 New Brunswick is a product of war, not of the First and Second World Wars with which our media are so preoccupied these days, but of the six wars of the long eighteenth century that stretched from 1689 to 1815. During these wars, all of which included battles on North American soil, the social relations among the First Nations, French, and British inhabitants were forged, often in blood. These conflicts became the foundation for mutable but seemingly mutually exclusive identities that continue to play out in New Brunswick politics and are documented in a recent telephone survey with New Brunswickers on how they engage the past in their everyday lives. In this paper, we will briefly outline scholarly developments that have informed our research, describe the eighteenth-century context in which many New Brunswick cultural identities were constructed, and then address the findings of the Canadians and Their Pasts survey in a province where popular engagement with history is complicated by diverse perceptions of the past.

The Canadians and Their Pasts Project

2 The Canadians and Their Past project used surveys, focus group discussions, and other research methods to probe the historical consciousness of Canadians. Inspired by previous studies conducted in Europe, the United States, and Australia, it also draws extensively on the theoretical work by European scholars, most notably Jörn Rüsen, Pierre Nora, Peter Lee, and James Wertsch. In Canada, Jocelyn Létourneau and Peter Seixas have played key roles in advancing this theoretical dialogue.

3 Coming late to the international conversation on historical consciousness, the Canadians and their Pasts team benefited from the lessons learned in the earlier projects. We took note, in particular, of the need to work closely with public historians and the general public in exploring the slippery concepts that our survey tried to measure. A grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Community-University Research Alliance (CURA) program nabled seven academic investigators to work with fifteen community partners spread across Canada. 1 The Institute for Social Research (ISR), an Organized Research Unit of York University in Toronto, and its Montreal-based partner, Jolicœur & Associés, were hired to conduct the bilingual survey. Given our interest in regional and cultural identities, the national sample of 2,000 interviews was equally divided among five “regions” of the country (Atlantic Canada, Quebec, Ontario, the Prairies, and British Columbia) and special samples of 100 interviews each were conducted with Acadians in New Brunswick; recent immigrants in Peel, near Toronto; and of mostly Plains Cree in and near Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. With the support of Parks Canada, a supplementary survey was conducted with 1,000 people in five of the largest urban areas in the country: Montreal, Toronto, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver. In all, we surveyed 3,419 Canadians. 2

4 For those who wonder why so much energy would be invested in exploring perceptions of the past, it is important to underscore the significance of history in determining current preoccupations. In Quebec, for example, “Je me souviens” has graced licence plates since 1978, and the British conquest of Quebec in 1759 is still a hot-button issue in the province. 3 More problematic are tensions reaching back centuries and even millennia that occasionally erupt in wars throughout the world. In every country on the planet, people harbour “hidden transcripts” about past events that come to the fore when it seems safe to acknowledge them. 4 Seekers of justice, Holocaust deniers, and claimants for dramatic change in the status quo invariably draw on the past to make their cases. Truth and reconciliation commissions in South Africa, Argentina, the Balkans, and Canada work at setting the record straight so that societies can move on. At the heart of these inquiries are the stories of individuals and families who have experienced injustice. While we often fail to acknowledge it, narratives about the past, with all their political and cultural baggage, underlie how we as human beings situate ourselves in the world. Moreover, a growing interest in the past, encouraged by the state and by an expanding tourist industry, is a significant trend in Canada and elsewhere. It is instructive, therefore, to reflect on the understandings that inform the historical consciousness of Canadians and to consider whether they are relevant to our present realities.

5 Our national survey consisted of seventy-five to eighty questions (depending on the number of follow up questions), eleven of which were open-ended so that respondents could answer in their own words rather than choosing from a pre-determined list. Answers to the open-ended questions were audio taped and transcribed. The questions were organized in seven sections: 1) general interest in the past; 2) activities related to the past; 3) understanding the past; 4) trustworthiness of sources of information about the past; 5) importance of various pasts; 6) sense of the past; and 7) biographical data. 5 Interviews for the national survey and special samples were conducted between March 2007 and October 2008. 6 This paper focuses on the New Brunswick and Acadian surveys, administered by telephone to 204 adults over eighteen years of age, 7 and on student-related projects undertaken by two of CURA’s partners, Institut d’études acadiennes and Centre d’études acadiennes Anselme-Chiasson et Musée acadien.

Contexts of New Brunswick History

6 Carved out of the old colony of Nova Scotia in 1784, New Brunswick was founded as a Loyalist colony following the American Revolutionary War. 8 By that time, wars had already left their mark on the territory and its indigenous and immigrant peoples. Under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, the mainland area of Acadia, now the provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, was ceded by France to Great Britain. Île Royale (Cape Breton) and Île St-Jean (St. John’s Island) remained under French control. During the two wars that preceded this transfer of territory—War of the League of Augsburg (1689-97) and War of the Spanish Succession (1702-1713)—French settlements around the Bay of Fundy were repeatedly attacked by New Englanders in retaliation for border raids conducted by the French and their Aboriginal allies from Canada, the colony in the St Lawrence region of New France.

7 The Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy, who lived in what became New Brunswick, were not consulted as their land passed between competing British and French empires. As allies of the French, the Aboriginal peoples in the region continued to look to France and its North American colonies for trade, religious affiliation, and military support against British encroachments on their territory. They also periodically waged guerilla warfare against the British occupiers, whose language, religion, and insistence on signing treaties were foreign to them. In this, they were aided and abetted by French authorities who refused to accept as final the 1713 division of territory in the region. To advance its power, France, in 1719, began building an imposing fortress at Louisbourg on Île Royal, which soon became a commercial and military base to be reckoned with throughout the North Atlantic world.

8 The Acadians, French-speaking settlers whose roots in the region dated back to the seventeenth century, became hostages to competing imperial claims to mastery. 9 By refusing to take an unconditional oath of allegiance to the British, which might force them to fight against the French in an anticipated future war, the Acadians in Nova Scotia became suspect as a potential fifth column in the eyes of British authorities. The refusal to take an unconditional oath was allowed to stand during the three decades of peace between Great Britain and France after 1713 but, with the declaration of the War of the Austrian Succession in 1744, the rules of the game changed.

9 Everyone suffered. In 1744, French and Mi’kmaq forces captured English soldiers and fishing families based at Canso and laid siege to the British administrative centre at Annapolis Royal. British and colonial forces captured Louisbourg in 1745. Two years later, a militia from New England en route overland to Annapolis Royal was decimated at Grand Pré by a force dispatched from Canada, which included Acadians in its ranks. Although the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748 ended the war and restored Louisbourg to France, a “cold war” continued in the colony, where the British upped the ante in 1749 by establishing an imposing military base at Halifax.

10 The flashpoint for the next round of warfare between Great Britain and France in North America was Fort Beauséjour. Built by the French in 1750, it was designed to challenge British claims to the territory north of the Isthmus of Chignecto, connecting what are now the provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Determined not to let France get away with this audacious land grab, the British attacked and captured Fort Beauséjour in 1755, ostensibly in a time of peace between Great Britain and France. British concerns about the loyalty of the Acadians, now a population approaching 15,000, were confirmed when Acadians were found among the militia defending the fort. Within weeks of the siege, British and colonial forces began the massive operation of deporting the entire Acadian population from the region. Nearly 2,000 Acadians managed to escape to Canada; others joined with their Aboriginal allies to attack the British and colonial forces charged with securing the territory. Most were scattered throughout the North Atlantic world and beyond.

11 The official declaration of war in 1756 and the British capture of Louisbourg in 1758, under the leadership of Major General Jeffrey Amherst and Admiral Edward Boscawen, were followed by one of ugliest chapters in New Brunswick’s history. In preparation for their assault on Quebec in 1759, Amherst sent troops to Île Saint-Jean, Gaspé, Miramichi, and the St. John River valley to round up fugitive Acadians for deportation and to destroy their settlements and those of their Aboriginal allies. To assist in these mopping-up operations, the British deployed detachments of Rangers, colonial militia known for their ruthlessness. Even Amherst, not a man known for leniency, disapproved of the bloody campaign conducted along the St. John River by Rangers under Moses Hazen. 10 British soldiers were only marginally less brutal, having developed their aggressive tactics during campaigns against the Irish and Scots. General James Wolfe, who had participated in the Battle of Culloden in 1746 and the capture of Louisbourg, led the expedition that destroyed the communities along the Baie des Chaleurs and Gaspésie in preparation for the campaign against Quebec the following year. 11 The painful memories of le grand dérangement would shape the cultural perceptions and political actions of surviving Acadians, as well as their Aboriginal allies, and serve as a stark warning to others of what the British were prepared to do to assure their ascendancy.

12 As French power in North America collapsed following the British capture of Quebec in 1759 and Montreal in 1760, the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy, desperate for European supplies on which they depended, made their accommodation with the British. Over the course of several months during 1760 and 1761, Aboriginal delegates travelled to Halifax to sign formal treaties of “peace and friendship” with the governor and council, acknowledging “the jurisdiction and Dominion of His Majesty George the Second over the Territories of Nova Scotia or Accadia” and agreeing to submit “to His Majesty in the most perfect, ample, and solemn manner.” 12 These treaties promised government-operated trading posts but made no mention of the land and its resources. Governor Jonathan Belcher was instructed by the British government to draw up a proclamation forbidding encroachment on Aboriginal territory, which he obediently did, but he refused to publicize it because, as he told his superiors, “If the proclamation had been issued at large, the Indians might have been incited . . . to have extravagant and unwarranted demands, to the disquiet and perplexity of the New Settlements in the province.” 13

13 For two decades after the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, British control over the old colony of Nova Scotia and its new settlements remained uncertain. 14 In the area north of the Bay of Fundy, Aboriginal peoples and Acadians— those who had managed to hide out during the deportations and those who, after 1764, returned to their homeland after taking an unqualified oath of allegiance—were more numerous than the immigrants from New England, Great Britain, and elsewhere. The small garrisons at Fort Howe at the mouth of the St. John River and Fort Cumberland (the former Fort Beauséjour) could not be expected to survive unaided even a well-organized guerilla assault.

14 During the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), some of the inhabitants in the northern section of Nova Scotia, most notably New England settlers on the St. John River and around Fort Cumberland, supported the rebelling Thirteen Colonies. So, too, did many of the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet, who, in July 1776, sent delegates to Watertown, Massachusetts, where they signed a “Treaty of Friendship and Alliance” with the Patriot government of Massachusetts. Aboriginal involvement in an attack on Fort Cumberland in the fall of 1776 and in the harassment of settlements on the St. John and Miramichi prompted British authorities to take both military and diplomatic action to secure the region. In 1780, they even brought in delegates from allied First Nations—among them the Ottawa, Huron, Algonkian, and Abenaki—to intimidate the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet. 15 British military and naval might, centred in Halifax and New York, ultimately prevailed in the North Atlantic but not in the overall contest. There is considerable irony in the fact that supporters of the United States in the Maritime region had backed the winners in the war but found themselves in the territory of the losing side following the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which left the colonies of Quebec, Nova Scotia, St. John’s Island (renamed Prince Edward Island in 1799), and Newfoundland under British control.

15 With the influx of more than 35,000 Loyalist refugees between 1783 and 1785, the fate of the old Nova Scotia was sealed. New Brunswick was declared a separate colony in June 1784, and all lands not formally granted and settled were forfeited to make room for the newcomers. 16 The Aboriginal and Acadian populations in the lower St. John River Valley were pushed aside, their provisional land grants no longer recognized by the British. Although the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet were eventually granted licenses of occupation for territory throughout the province, portions of these holdings were whittled away by immigrants who often squatted without penalty on reserve lands. 17 The Passamaquoddy, who straddled the border between New Brunswick and United States territory, were ignored. Meanwhile, the Acadians, who had wandered from place to place for more than a generation, established permanent communities centred in the northwest (Madawaska), northeast (Caraquet), and southeast (Memramcook) of New Brunswick.

16 The final chapter in the mass movement of peoples came with the Napoleonic Wars, which transformed New Brunswick into a “timber colony” and opened the way for the easy passage of British immigrants, the majority of them Irish, to New Brunswick. 18 As ballast in the ships travelling from Great Britain to fetch colonial timber, the Irish emerged as a significant element of the Anglophone population by 1850, especially in and around Saint John, Fredericton, and Miramichi.

17 New Brunswick achieved responsible government in 1851 and became a province of Canada in 1867. By this time, New Brunswick’s shipbuilding and manufacturing industries were thriving and continued to do so until the late 1880s. Thereafter, Canadian economic development shifted dramatically and irrevocably westward as industry concentrated in the St. Lawrence-Great Lakes heartland and the west was opened to settlement following the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885. Out-migration, especially among Anglophones, documented the attraction of more prosperous areas of the North American continent. People claiming Francophone ethnic identities, meanwhile, doubled from 16 percent of New Brunswick’s population in 1871 to more than a third by 1971. 19 Under the British North America Act (1867), Aboriginal policy became the responsibility of the federal government, which introduced a comprehensive Indian Act in 1876 that, in effect, made Aboriginal peoples second-class citizens.

18 As descendants of a people with a dramatic story of survival, the Acadians absorbed a trickle of Francophone immigrants from France, Jersey, Quebec, the West Indies, Africa, and elsewhere, as well as many Anglophones into an “Acadian” identity. An “Acadian Renaissance” beginning in the 1860s brought greater cohesion and purpose to Francophones throughout the Maritime region. 20 At a series of conventions in the 1880s, Acadian delegates adopted the Feast of the Assumption (15 August) as the national holiday, an Acadian flag—the French tricolour with a yellow star signifying devotion both to the Virgin Mary and to the papacy—and “Ave Maris Stella” as their national hymn. Acadian newspapers, colleges, and associations, including the Société Nationale de l’Assomption, founded in 1881, provided leadership. 21 After a century of Acadians laying the groundwork, Louis J. Robichaud, an Acadian determined to improve conditions for his people, was elected Liberal premier of the province in 1960. Robichaud’s program of Equal Opportunity, launched in 1965, and a commitment to bilingualism both federally and provincially in 1969 set Acadians on a course of empowerment that continues to yield remarkable results economically, politically, and socially. 22

19 In recent years, Acadians have engaged in what scholars call the “memory industry” more productively than most Canadians. 23 Beginning in 1994, congresses held every five years encourage the estimated two million Acadian descendants living around the world to return to the “homeland” to participate in activities commemorating their history and culture, and annual Acadian Day celebrations are enthusiastically celebrated in Acadian communities. The success of identity politics was symbolically recognized in 2003 when Queen Elizabeth II acknowledged the role of the British Crown in the Acadian deportation and designated 28 July of every year as “A day of Commemoration of the Great Upheaval.”

20 The numbers of Aboriginal people in New Brunswick increased less dramatically than for the Acadians, but the same sense of empowerment swept through the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy communities beginning in the 1960s. In this, they shared with First Nations across Canada a long-held sense of grievance about their ill treatment in a territory that they had once dominated. Even more than the Acadians, Aboriginal peoples in New Brunswick suffered from extreme poverty and lacked the resources to make an easy transition to the industrial age. Refusing to be passive victims of discrimination, Mi’kmaq and Maliseet have petitioned authorities and launched court cases relating to Aboriginal and treaty rights, while the Passamaquoddy have waged a long-term battle, so far without success, to be officially recognized as Status Indians in Canada.

The Canadians and Their Pasts Survey

21 The Canadians and Their Pasts surveys capture the English-French duality that defines New Brunswick at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Since only one Aboriginal respondent was caught by our random phone calls, another survey will be required to document their engagement with the past, but our special sample of the Plains Cree in Saskatchewan suggests that First Nations are among the most historically conscious of all people living in Canada. The number of people from racialized minorities is also too small to make statistical generalizations. Indeed, because of the generally small numbers of interviews overall in New Brunswick, it is important to emphasize that the findings of the surveys discussed here are meant to be suggestive of trends and to raise questions rather than to draw definitive conclusions.

22 In New Brunswick, the Canadians and Their Pasts survey was answered by 204 people, 104 in the national survey and 100 in a special sample of Acadians in three communities: the city of Dieppe, near Moncton (population 18,565 in 2006), and two smaller Acadian communities in the northeastern part of the province, Petit-Rocher (population 1,949 in 2006) and Caraquet (population 4,156 in 2006). 24 The latter two communities are located in the heart of old “Acadie” in the northeastern section of the province, where people historically made a living primarily from fisheries, forestry, and mining. In contrast, Dieppe is home to the so-called “Anglo-Acadians,” who mingle energetically in the dynamic economy of a relatively thriving urban area that includes the city of Moncton. 25 The respondents in the Acadian survey answered the questions in the national survey and three additional questions designed to capture the extent to which they participated in annual Acadian Day celebrations, the Acadian Congresses, and two historical anniversaries recently commemorated in the Maritimes—the founding of the French colony at St. Croix in 1604 and the expulsion of 1755-62. 26

23 A comparison of the responses in the two samples from New Brunswick is complicated by the fact that nearly one-third of the respondents in the provincial sample self-identified as Francophone and respondents answered in French or English in both surveys. In addition to breaking down the interviews into French (N=110) and English (N=94), responses were sorted according to Francophone and Anglophone self-identification to determine if any major differences occurred across the language/ethnic divide. The following comments are based on the provincial (N=104) and Acadian (N=100) samples, unless the more calibrated breakdowns revealed significant findings.

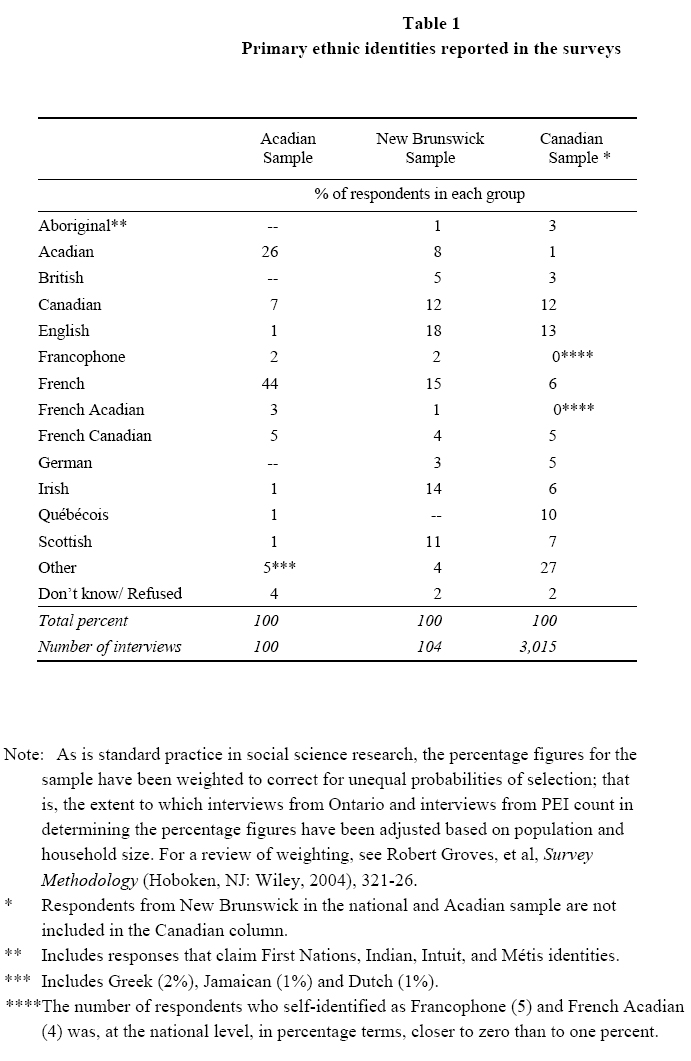

24 Simple notions of cultural identity as it relates to Acadians were called sharply into question by our findings. In the New Brunswick sample, respondents self-identified as French (15 percent), Acadian (8 percent), French Acadian (1 percent), French Canadian (4 percent), or Francophone (2 percent), while the range of self-reported identities in the Acadian survey was even broader: French (44 percent), Acadian (26 percent), French Canadian (5 percent), French Acadian (3 percent), Francophone (2 percent) and Québecois (1 percent). Seven percent of the respondents in the Acadian sample considered themselves Canadians first compared to 12 percent provincially (see Table 1). Thus, the term “Acadian,” as employed in this paper, masks a complicated set of primary identities. 27

25 Our survey reflected quite accurately the census-derived characteristics of New Brunswick’s population. 28 As is the case with most telephone surveys, our respondents were more highly educated and received higher annual incomes than the census average. The Acadian sample, which targeted three communities rather than a random sample of the Acadian population, was especially tipped toward the higher end of the education/income scale, which to an extent difficult to quantify explains the high level of historical consciousness reported. 29 More respondents in the Acadian sample had a university degree (32 percent) than in the provincial sample (18 percent), and more respondents in the Acadian sample (31 percent) were under the age of 40 compared to the provincial sample (18 percent) and the national sample (29 percent). Everyone in the Acadian sample was born in Canada and most respondents were born in New Brunswick (provincial sample 84 percent; Acadian sample 93 percent). In religious affiliation, 90 percent in the Acadian survey reported that they were Roman Catholic, compared to 49 percent in the provincial sample. In the Protestant category (31 percent), Baptist (15 percent), United Church (9 percent), and Anglican (6 percent) topped the list. Provincially, 7 percent claimed no religion, compared to 6 percent in the Acadian sample and 18 percent nationally.

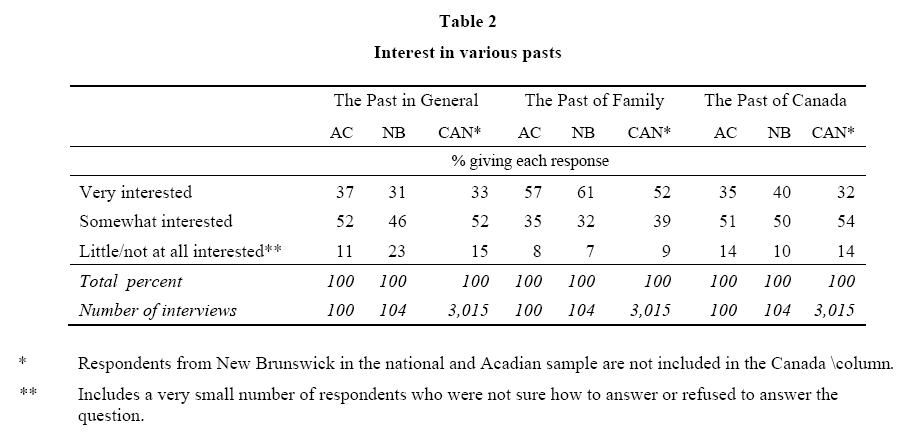

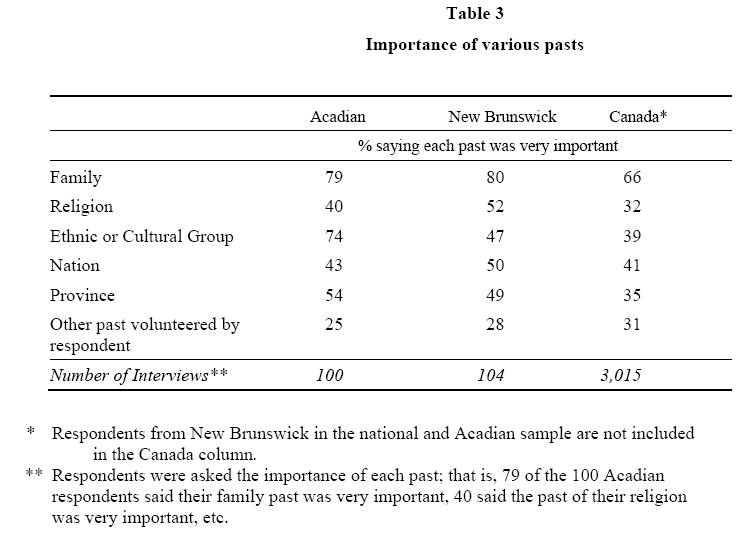

General Interest in the Past and the Importance of Various Pasts

26 Overall, New Brunswick was often an outlier in the questions we asked about interest in and importance of various pasts (see Tables 2 and 3). Not only did New Brunswick respondents rank the highest in terms of being “very interested” in family (61 percent) and Canadian history (40 percent), they were also more likely than Canadians from other provinces to declare religious (52 percent), ethnic (47 percent), and Canadian history (50 percent) as “very important.” While the differences are, for the most part, not statistically significant, the trend is clear and consistent. 30

27 The first question that comes to mind in analyzing the responses to our survey is the degree to which Acadian heritage plays a role in determining the New Brunswick provincial outcomes. In some cases the answer is clear. For instance, 74 percent of the respondents in the Acadian sample felt that their ethnic history was “very important,” compared to 47 percent in the provincial sample and 39 percent in the national sample. A slightly larger percentage (56 percent) of those with Acadian identities in the provincial sample cited ethnic history as “very important,” but only 44 percent of the Acadians sampled across the country claimed that their ethnic history was “very important,” suggesting that, as they move further away from the Acadian heartland, ethnic history becomes less relevant.

28 More New Brunswickers ranked the history of their religion as “very important” than respondents in any other province (52 percent to a national average of 32 percent). In this case the higher positive response rate to this question is found on both sides of the linguistic divide but is especially strong among Anglophones where a deeply-rooted evangelical tradition prevails, especially among Baptists. This, coupled with the strong affiliation to Roman Catholicism by respondents of both Acadian and Irish heritage, helps to account for the importance accorded to religious history in the province.

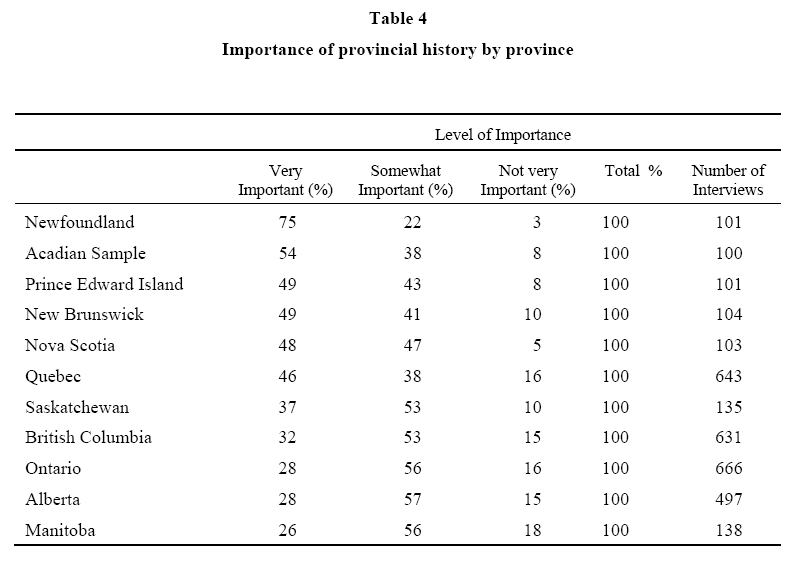

29 In answer to the importance of provincial history, New Brunswick was outranked by Newfoundland and Labrador (75 percent), tied with Prince Edward Island (both 49 percent), and followed closely by Nova Scotia (48 percent) and Quebec (46 percent). The divide at the Ottawa River in signaling the importance of provincial history (the Canadian average is 35 percent) seems to indicate a direct relationship between the length of European settlement and identification with province/region (see Table 4). Both the provincial and Acadian respondents ranked provincial history as “very important” almost equally (49 percent to 54 percent).

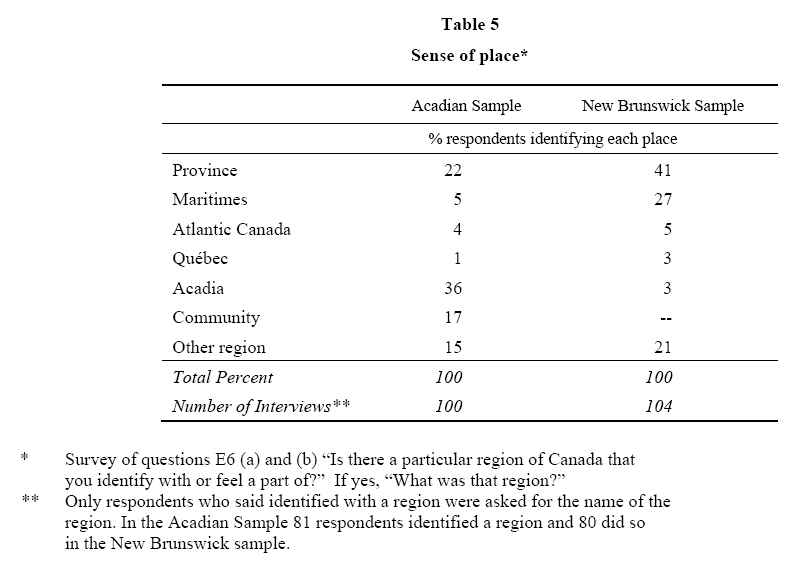

30 New Brunswick respondents were more likely than Canadians elsewhere to identify with a region other than their province (see Table 5). In the provincial sample, 32 percent of respondents who said they identified with a region mentioned “the Maritimes” or “Atlantic Canada,” but only 9 percent of Acadians did so. In the Acadian sample, 36 percent of those who claimed a regional affiliation identified with “Acadie,” a place that has no formal geopolitical base in the twenty-first century. Slightly more than 17 percent of the Acadian sample mentioned a specific community as their primary site of identity, but none did so in the provincial sample. In the Acadian sample, respondents were also more likely to consider the region they identified with as “very important” (81 percent compared to the 67 percent in the New Brunswick sample and 48 percent overall for the national sample). Meanwhile, 41 percent of the provincial sample identified with their province compared to 22 percent of the Acadian sample. These “limited” identifications in no way impeded the tendency of respondents in New Brunswick to consider the history of Canada as “very important.” Men in the two New Brunswick samples were more likely than women to identify with the Maritimes or Acadia, suggesting that men tend to identify with broader regional horizons.

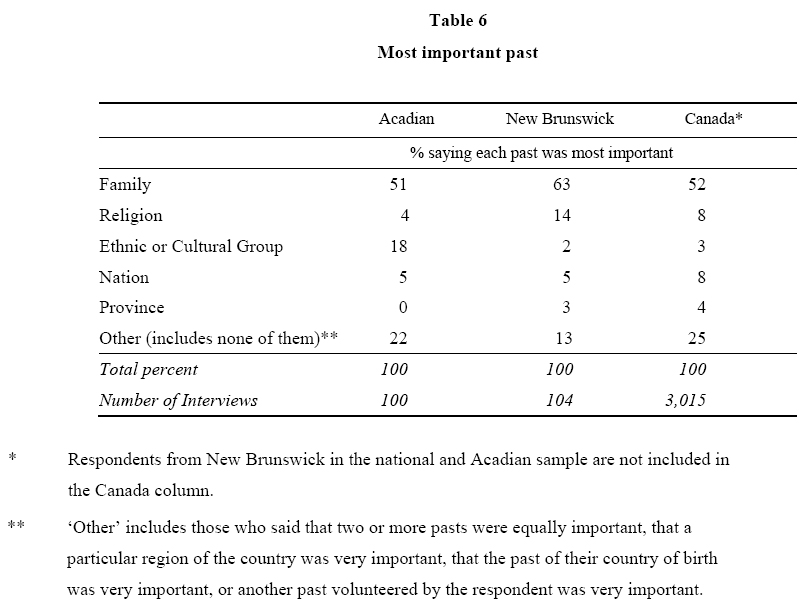

31 Like most respondents to the survey, New Brunswickers opted for family history when asked to decide the most important past to remember (see Table 6), with respondents in the provincial sample more likely than those in the Acadian sample to consider family the most important past (63 percent to 51 percent). Religion ran a distant second at 14 percent in the provincial sample and was trumped in the Acadian sample by ethnic/cultural past at 18 percent. In the New Brunswick sample, national and provincial history ranked third and fourth (5 percent and 3 percent), rankings reserved in the Acadian sample for Canada (5 percent) and religion (4 percent). No one in the Acadian sample chose the past of their province as the most important past.

Activities Related to the Past

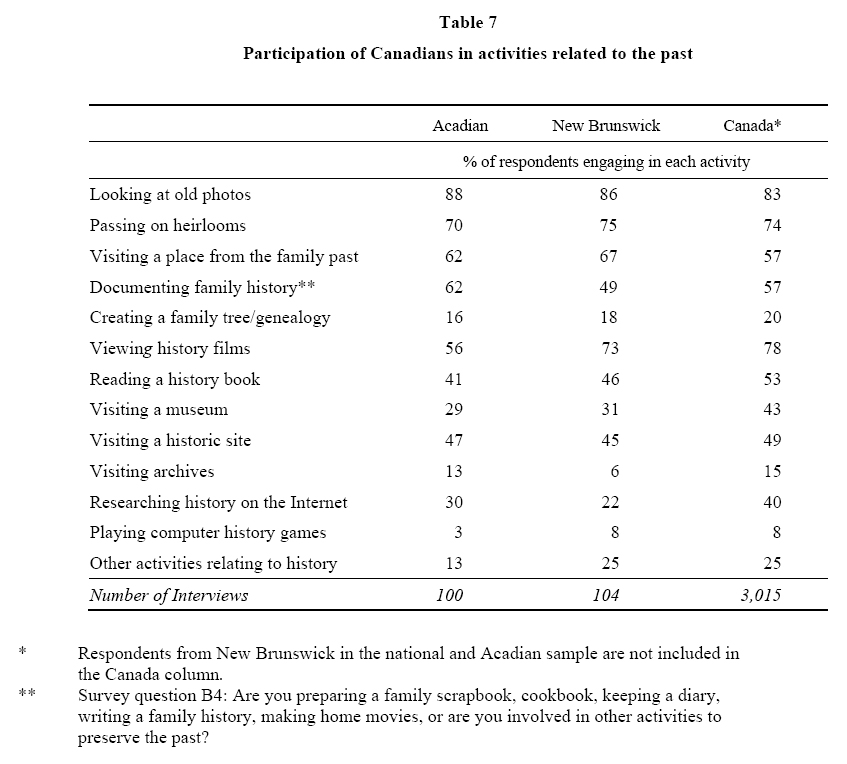

32 One of the major findings of the national survey was the extent to which most Canadians engage the past. Overall, 99 percent of respondents claimed that during the previous twelve months they had been involved in one of the twelve activities listed in the questionnaire, and 56 percent claimed to have participated in five or more. The most common activities touched on family history, such as looking at old photographs, preparing a family document such as a scrapbook, diary, or cookbook, passing on heirlooms, researching their genealogy, and visiting places important to the family’s past, but reading history books, watching history movies, and visiting museums and historic sites also ranked surprisingly high.

33 While New Brunswick responses to questions relating to family history were similar to the national average (see Table 7), the province lagged behind in the use of the Internet to research history (22 percent compared to a national average of 40 percent), in visiting museums (31 percent to 43 percent), and in consulting archives (6 percent and 15 percent). The findings point to an intriguing paradox. Although New Brunswickers often led the nation in the level of interest they report in the past, they are less likely than Canadians in other provinces to be engaged in some of the activities that relate to history. More will be said on this matter further along in this paper.

34 The provincial and Acadian responses to the questions focusing on activities relating to the past are similar with two exceptions. Respondents in the Acadian sample were more likely to be engaged in documenting their family past than those in the provincial sample (62 percent to 49 percent) and were less likely to watch movies, videos, DVDs, or TV programs about history (56 percent to 73 percent). The respondents in the Acadian sample were also less likely than their provincial and national counterparts to report “other activities” relating to the past (13 percent, 25 percent, and 25 percent respectively). The latter response must be balanced by the exceedingly high positive response rate in the Acadian sample (79 percent) to the supplementary question posed: “In the last five years did you participate in any activities that celebrated or commemorated Acadian heritage and history?” Since the national survey did not include a question that specifically probed “community” activities relating to the past and it may not have occurred to respondents confronted by a cold call to mention it in the “other” category, this aspect of historical engagement in New Brunswick may have been overlooked.

35 The visual past as represented in photographs is the way that most New Brunswickers and Canadians generally engage the past. For the majority of respondents, the most recent engagement with old photos related to family milestones such as birthdays, graduations, weddings, anniversaries, and deaths. One New Brunswick man who had retired from the Canadian Armed Forces reported that he most recently looked at old photos when “my mother moved into a special care home. We cleaned out her apartment and we retrieved her old photographs and some old documents” (NB ID 1150). A few respondents mentioned looking at community photographs. One respondent in the Acadian sample reported : « Les photos que j’ai regardées, c’était sur la ville d’où je viens, ici à Caraquet; donc les photos qui montraient la ville au 19e siècle début du 20e siècle, par exemple. Donc j’ai beaucoup plaisir à garder ces photos là. Je regarde pas systématiquement, mais disons que c’est les dernières photos. Je sais pas si les photos que j’ai regardées sont des photos accessibles ici dans la ville » (AC ID 497). Another respondent who volunteers at a nursing home remarked that “a man comes and does the presentation on the history of the town that. . .we live in. And. . .he had a bunch of old photos of the town and. . .of the buildings here and everything, so that was. . .pretty interesting to look at” (NB ID 957). A woman from Moncton revealed that she had been looking at old photographs while she was “with a very good friend of mine who recently purchased a heritage home” (NB ID 1001).

36 Many people we interviewed were “memory keepers” for their families and communities. When asked about looking at old photographs, a respondent from Grand Manan explained that she was “just trying to take care of the collection that I have received from my father and grandfathers.” For this woman, the local history society had inspired more research: “The curator wanted to do [this research]. . .my grandmother came from Boston, moved here. . .in 1922 or so. . ., quite a contrast from Boston. How she adapted to life here on a farm, no electricity, no conveniences at all, raised hens, chickens, even built her own hen house. . . . She was trying to recall that and put it on a display at the museum with pictures. . .” (NB ID 988). School projects spurred some people to research photographs: “I did a little bit of looking because. . .a relative. . .was doing something at school and she had to find out a little bit about the family's past,” a woman from Fredericton reported (NB ID 984). A respondent from Quispamsis noted that her mother was “making a. . .special calendar. . .for the family which includes. . .everybody's birthday. . .with a picture [associated with] their birth and anniversaries. . .” (NB ID 1161).

37 “Scrapbooking,” a word that has been incorporated from English into the Acadian vocabulary, was mentioned by several female respondents in both surveys. One woman from Petit-Rocher told the interviewer:

38 Among female respondents, engagement with the past often took the form of arts, crafts, and cooking. “I do a lot of cooking that my grandmother taught me how to do,” a retired woman from St. George told our interviewer (NB ID 913). Other heritage activities mentioned included hooking rugs, which was perceived as a traditional Acadian craft. A woman from Dieppe reported: « On fait les tapis. C’est que. . .les grand grand tantes, les tapis, ils accrochent ça. Ils faisaient ça pendant l’hiver. Et au printemps, ils accrochent ça après la maison. Puis le monde les achètent. C’est une tradition » (AC ID 7).

Understanding the Past and Trusting Sources

39 The survey included several questions designed to probe the way that respondents understood the past and which sources of historical information inspired their trust. When we asked respondents to rate how much selected activities in which they participated helped them to understand the past, both the New Brunswick and the Acadian samples were similar to the national survey in which about 60 percent responded “a great deal” or “a lot.” Not surprisingly, respondents in the Acadian sample (61 percent) were more likely than New Brunswickers in the national sample (45 percent) and respondents overall (40 percent) to respond “a great deal” or “a lot” to the question which asked how much a particular activity helped them understand “who you are.”

40 When respondents were asked “to think about a time in your life when a person, event, or something else might have been very important to you,” they usually circled back to their family. An elderly female respondent from Woodstock recalled New Brunswick’s forestry industry: “My father as a young man worked at logging and some of the names that he said then about places in New Brunswick. . .still make me remember him” (NB ID 1027). The death of a close relative was often offered as an event that prompted reflections on the past, but, for one young man from Petit-Rocher, it was his role as a « joueur de hockey pour l’Université de Moncton. Alors, ça représente assez les Acadiens du Nouveau-Brunswick. Il y a une grande importance, une grande. On a gagné le championnat de l’Atlantique. Là, c’est un bon souvenir » (AC ID 301).

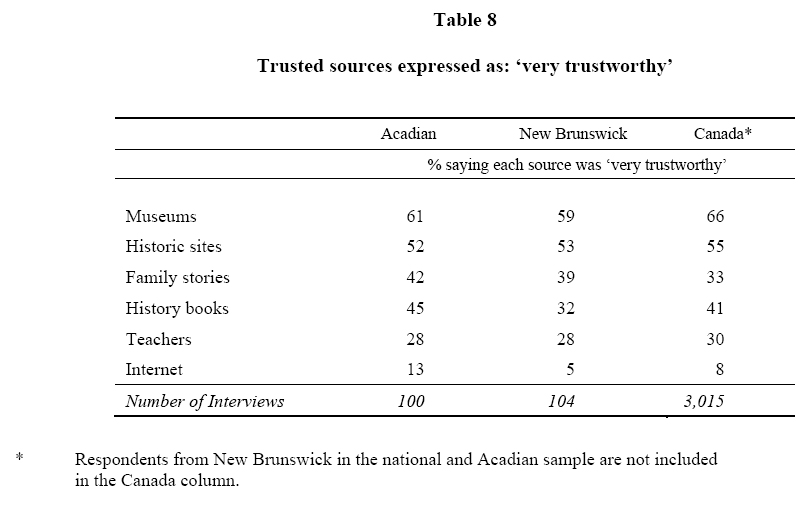

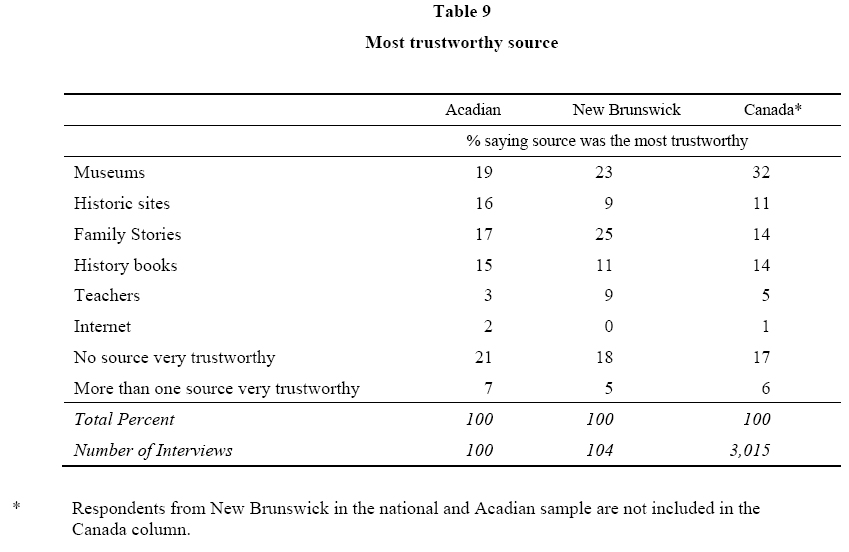

41 When it came to sources of historical information that inspired trust, respondents in the Acadian sample were more likely than those in the provincial and national samples to say that books were “very trustworthy” (see Table 8). Like most Canadians, New Brunswickers ranked museums and historic sites as the most trustworthy sources of historical information, some respondents mentioning the research and collaborative expertise that informed museum displays, others impressed by the tangible artifacts presented. When it came to choosing the most trustworthy source, family stories rose to the top of the list in the New Brunswick survey and came a close second to museums in the Acadian survey (see Table 9). Respondents nationally and in the New Brunswick samples were marginally more likely than those in the Acadian sample to trust teachers and also more likely to mention a teacher as significant in sparking their interest in the past. 31

42 Most survey respondents had difficulty explaining what they would do when confronted with conflicting information about the past. For many respondents, an eyewitness was the best source: “I would probably try to talk to as many people who had been through it, just elderly people. . .because I believe word of mouth is the best,” a woman in the Acadian sample told the interviewer (Acadian ID 35). Others commented on the complicated process of seeking historical truths: « Si je suis vraiment intéressé, » one respondent reported, «c’est sûr que j’irai consulter les archives. Tous les moyens que tu m’avais dit tentour, les musées, j’essayerais de faire un gros portrait de la chose de toutes le plus de ressources possibles » (AC ID 1). Another respondent, who worked as a lab technician, understood that different approaches would be required to research various pasts: “Is this on. . .like a national level or your personal level? Well, again, I guess it would have to be research in archives and museums and all that type of thing. It'd be hard to do” (NB ID 1088). An Acadian respondent underscored the biases that prevailed in historical accounts:

Sense of the Past

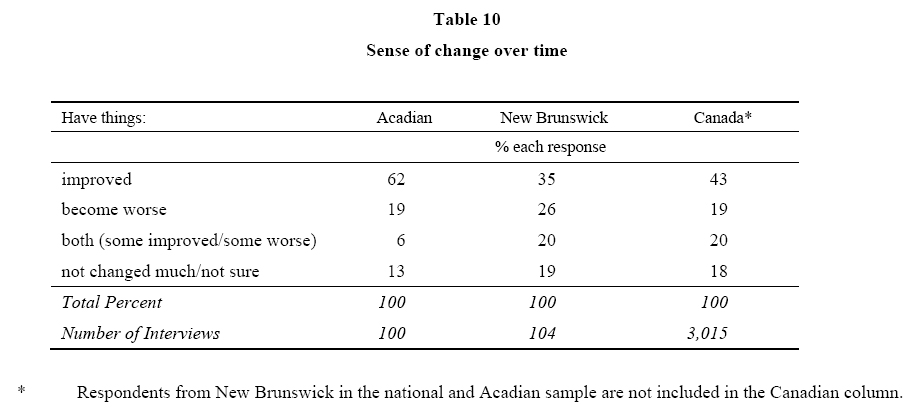

43 The two New Brunswick surveys yielded similar responses to questions that probed a respondent’s sense of the past, with one important exception. In the Acadian sample, 62 percent of the respondents felt that conditions had improved over time, while only 35 percent in the provincial sample thought so (see Table 10). This remarkable difference almost certainly reflects the empowerment that Acadians have experienced over the past half century. A female respondent from Dieppe made the point clearly: « Les Acadiens, on a plus de respect intelligent. On est voulu. On est moins soumis » (AC ID 86). For many Acadians the improvement in educational opportunities was a key factor in prompting a positive response: « La culture acadienne. On était assimilé. On avait pas l’enseignement français. Puis, depuis 1965 plus ou moins, on a finalement l’éducation francophone. Donc c’est l’amélioration » (AC ID 474). Yet another remembered: « Moi, je dirai, dans nos cultures, c’est une question de l’éducation. Ici on a l’Université de Moncton. C’est un gros, gros, gros point. Donc les gens sont tout capables d’aller à l’université pour s’éduquer, d’avoir des professions dans la société. Si on recule les derniers cinquante ans, c’est incroyable » (AC ID 50).

44 For most New Brunswickers, medical and technological advances topped the list of improvements over time. One woman, who described her occupation as housewife, declared that “Dishwashers, or all that stuff, all the material things have improved for sure” (NB ID 1095). Those who felt that conditions had become worse cited the decline in morality, the dissolution of the family, economic conditions, pollution, drugs, violence, and the fast pace of life that undermined what were perceived as Christian and small community values. In this, New Brunswickers were much like other Canadians who sensed that the world was in a mess and much in need of returning to values that they believed had sustained a better, if materially less advanced, society in the past.

45 In both the provincial and Acadian surveys, war was mentioned in a number of contexts. Most of the references to military conflict related to the view that all wars should be remembered so that people would, as one respondent pointedly phrased it, “stay away from all that foolishness” (NB ID 1036). A woman from St. Stephen included the record of wartime sacrifices in what should be handed down to the next generation because, she argued, “They paid a price and we get to. . .go free” (NB ID 1159). The same point was made by an Acadian respondent:

46 Les connaissances qu'on a eues, les erreurs qu'on a faites. Le monde…les gens présentement, ils oublient beaucoup les sacrifices que les personnes ont faites des années passées pour nous donner que-ce qu'on a aujourd'hui. Si c'est pas pour les personnes là on serait, je dis, pas à la même place. Puis je pense que surtout les jeunes commencent à oublier. Ça fait trop longtemps qu'on n’a pas eu comme un guerre ou quelque chose que le monde ont devraient se battre pour vivre. Le monde, ils sont un petit peu gâtés. Puis ils apprécient pas des choses du passé. (AC ID 37)

47 Several respondents made reference to a relative being involved in the Second World War. Interestingly, historical memory seemed too fragile to reach back to the First World War. Other than Acadians, no one mentioned the colonial wars that had such an enormous influence on the province’s history.

48 In answer to the question about what should be passed down to the next generation, many respondents in both survey samples mentioned the importance of remembering the hardships that their pioneer ancestors faced: “If you see some of the places they went with only an axe and a canoe,” one woman noted, “you have to have a tremendous amount of respect for them who, [with] no more than just basic tools, built homes, fished or hunted—got a living somehow” (NB ID 1027). A man from Fredericton felt that it should be “the way we lived, the way we worked, how we raised our families and generated history, and. . .what's going on in the Maritimes” (NB ID 1081). Yet, another respondent noted that what he most wanted to pass down to the next generation was « l'aspect de tous comprendre comment fort nos anciens on travailler pour nous donner la chance. . . .» (AC ID 50).

49 Not surprisingly, several Acadian respondents indicated that “l‘héritage acadien” was the aspect of the past that they most wanted to transmit to the next generation, and several of them mentioned the French language as the most important aspect of their Acadian heritage. Unlike the Anglophone respondents whose heirlooms tended to be confined to material items passed down within families, some Acadians were inspired to preserve less tangible aspects of their culture, music in particular. One woman noted: « Le monsieur qui a écrit ‘De temps la mère robette.’ Une chanson acadienne. C’était André Theborthe de notre famille » (AC ID 7). Another respondent, who identified himself as a “French Canadian” but was interviewed in English, reported: “I'm a big person for pictures! Taking pictures, and putting together scrapbooks, and even recording. . . . I’m also a singer, so we've recorded some songs with the old group that I was in. . .as a reminder of who we were” (AC ID 92).

50 Half of the respondents in both New Brunswick samples considered history to be a part of their everyday lives rather than something they mostly thought about when they visited museums (the national average was 43 percent). This finding may, in part, explain the New Brunswick paradox whereby respondents express a stronger interest in various kinds of history than other Canadians but are less likely to participate in formal activities relating to the past. For those who grow up surrounded by kin and embedded in a deeply-rooted community, there may be a greater sense of who they are historically and less need to be engaged in research activities designed to understand themselves. 32

Sociodemographic Variables

51 The surveys revealed differences in engagement with the past based on the sociodemographic variables such as age, education, gender, and income. As noted above, these variables even determined to some extent who agreed to answer the survey questions. More women than men and people in higher income brackets in both samples answered the survey, and more people over forty years of age agreed to answer the survey. In the analysis of survey data, education and gender emerged as the two most important predictors of engagement with the past.

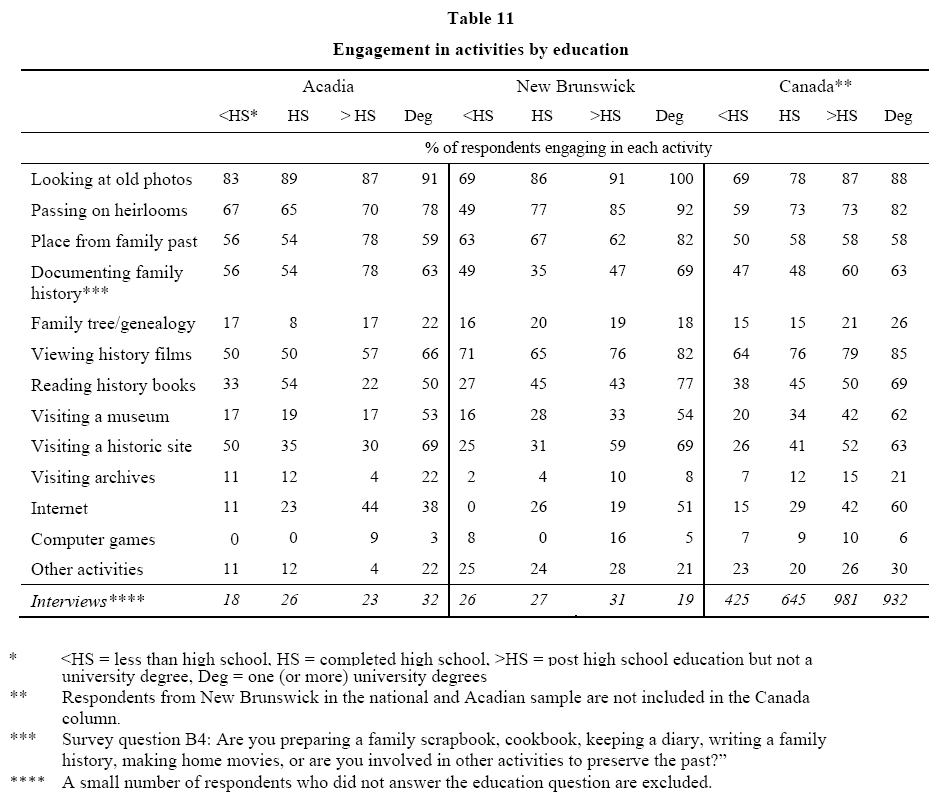

52 For most of the activities about which we inquired, higher levels of education correlated with higher rates of participation. Nationally, respondents with university degrees were more likely to report that they had looked at old photographs, were passing on heirlooms, were documenting family history, and had visited museums or historic sites in the last twelve months. This pattern of increasing participation by education, while less pronounced, is also generally true for the New Brunswickers in both the national and Acadian sample (see Table 11).

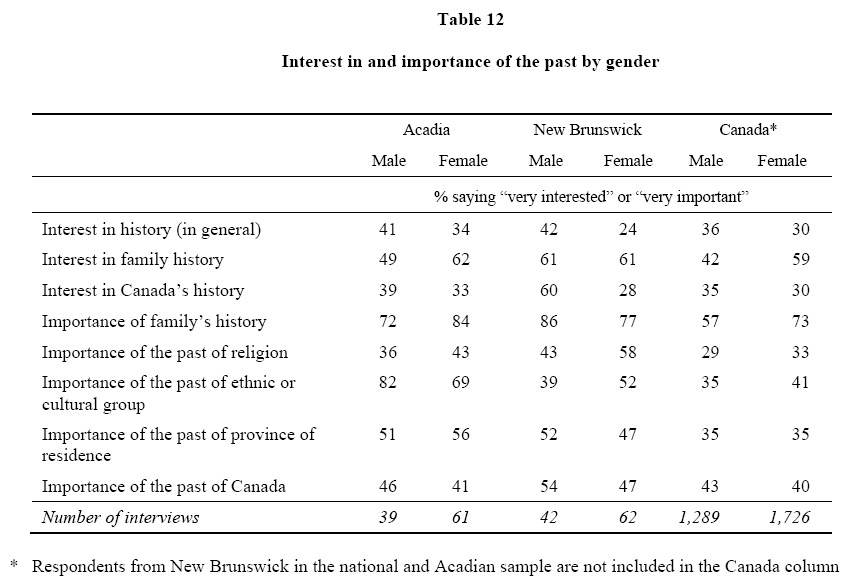

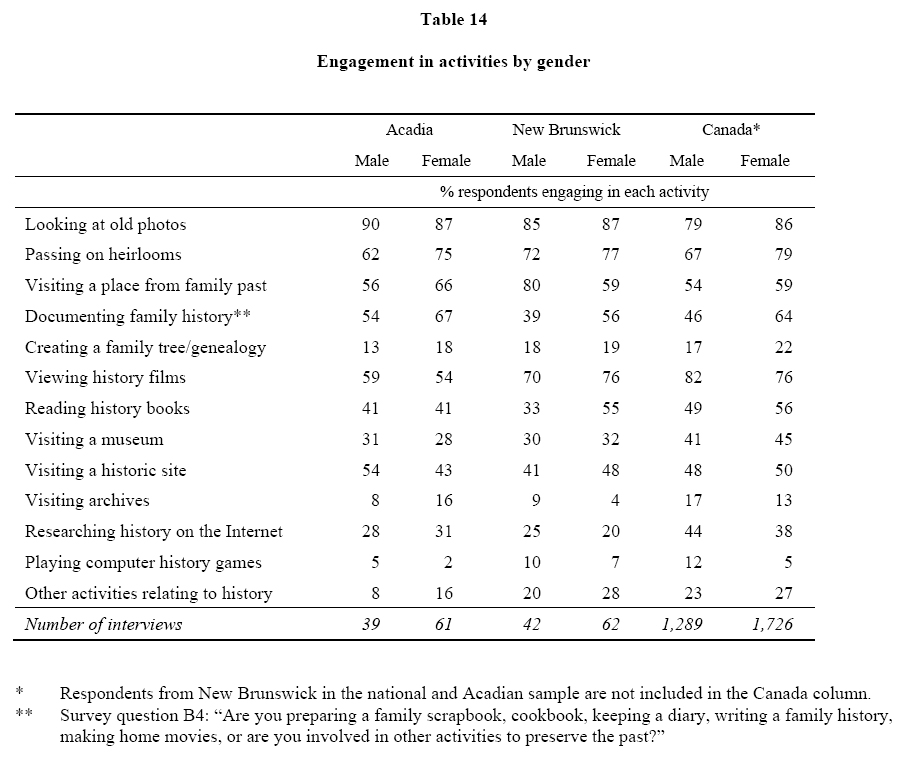

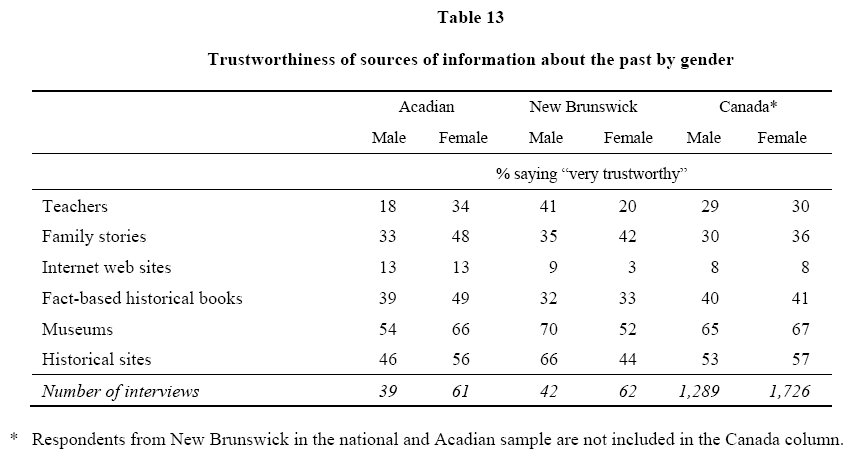

53 The results broken down by gender are particularly revealing (see Tables 12 and 13). At the national level, more women than men oriented themselves around family history, both in terms of interest (59 percent to 42 percent) and in the importance (73 percent to 57 percent) they assigned to it. The same generalization held true for the Acadian sample but not for the New Brunswick sample, where men claimed as much interest in family history as women (61 percent) and assigned it more importance (86 percent to 77 percent). The spread between men and women on interest in history generally (42 percent to 24 percent) and in Canadian history (60 percent to 28 percent) was more dramatic in New Brunswick than nationally, which might be explained, in part, by the small size of the New Brunswick sample. As in the national sample, women were more likely than men in both the New Brunswick and Acadian samples to regard religious history as important. Women in the Canadian and New Brunswick samples assigned higher value to ethnic history than men, but the ratio was dramatically reversed in the Acadian sample (82 percent to 69 percent).

54 In the questions relating to activities, women both nationally and provincially were more likely than men to report that they were passing down heirlooms and documenting family history by preparing a scrapbook, keeping a diary, or engaging in other similar activities (see Table 14), but men in New Brunswick, unlike men in the national and Acadian samples, predominated in visits to ancestral places (80 percent to 59 percent). Men in the Acadian sample were more likely than their male counterparts in the provincial and national surveys to answer affirmatively to the question about documenting family history, a finding that points to the significance of cultural differences in how men (and women) engage the past in Canada. For many Acadians, ethnic identity is inextricably linked to family history, and being able to claim a family heritage that extends back to the deportation is a source of great pride.

55 At the national level, men were marginally more likely than women to play history computer games, do historical research on the Internet, engage history on a screen, and visit archives. These trends held true for New Brunswick with the exception of viewing history films in the provincial sample and consulting archives in the Acadian sample, where women reported engaging the past in these ways more than men did. Women in the provincial sample were also much more likely than men (55 percent to 33 percent) to report reading books on history.

56 For the most part, men and women in New Brunswick were similar in their responses to the questions probing sources of trust and sense of the past. Male respondents in the provincial sample were more likely than female respondents to mention that a school teacher had inspired their interest in the past and judged teachers as more trustworthy (41 percent to 20 percent). In the provincial sample, women were more likely than men to trust family sources of information (42 percent to 35 percent), while men placed a much higher trust in museums and historic sites than female respondents (museums: 70 percent to 52 percent; historic sites: 66 percent to 44 percent). Women in the Acadian sample reported more trust than men did in all sources of historical information except for the Internet, which inspired a low sense of trust equally across gender lines (13 percent).

History and Identity

57 Our surveys suggest that many Acadian respondents have a strong sense of who they are and often engage the historical narrative that informs their identity. Because they were specifically asked about community events and historical celebrations at the end of the survey, Acadians described such activities in detail, but the deep sense of the past in specific places among Acadian respondents was signalled in the answers to the earlier questions posed by the interviewer. A female respondent from Dieppe, who chose to be interviewed in English reported that she had recently looked at photographs on Facebook, where a group had posted “old photographs of Richibucto, and those areas that concern me because I lived there for eighteen years. . .” (AC ID 92). In the national survey, a respondent from northeastern New Brunswick who answered in French mentioned being engaged in a wide range of activities relating to the past, and she told the interviewer about a folkloric tradition unique to her area involving the appearance of a phantom cart, La Charrette Mystérieuse, which is believed to foreshadow death (NB 959). 33 A respondent from Caraquet recalled looking at old photographs of the Château Albert hotel, which had recently been reconstructed in the Village Acadien historic site (AC ID 471).

58 When asked specifically about involvement in heritage activities in the previous five years, the Acadian respondents had much to report. One man described for the interviewer how August 15 th, the Acadian national holiday, was celebrated in his community:

59 Family reunions, mentioned by several respondents, are often planned to coincide with the Congrès mondial acadien. One respondent carefully explained that Acadian Congresses

60 Another respondent reported that he was looking forward to a Godin family reunion associated with the 2009 Congress in Caraquet: « La plus belle exemple, justement, pour l’an prochain, pour le festival des Acadiens, là on a la fête des Godin, puis on s’intéresse là tsu, on garde nos racines » (AC ID 453). Yet another Acadian respondent was an organizer of an earlier Congress and had recently revisited photographs from that event: « C’était à l’occasion du Congrès mondial acadien de 1994. Et puis j’ai regardé des photos. J’étais impliqué dans l’organisation cette année-là. Et j’ai regardé justement un peu d’histoire de cette belle rencontre qu’on a eue en 1994 » (AC ID 61). This man knew exactly what he would bequeath to the next generation: « Albums familiaux, les grands événements qui peuvent se passer dans notre communauté, surtout sur le bord de la francophonie, c’est-à-dire, les événements comme le congrès mondial acadien, et toute rencontre de famille, et toute rencontre culturelle qui touche un peu notre héritage acadien. » This was important, he argued, because « Je pense qu'on a un lien avec le passé qui dans le fond ça connecte et ça branche avec notre futur. Alors il faut. . . . C'est important de garder notre culture, de savoir qui on est et ou on vient pour s'assurer d'un futur solide; et puis aussi je pense dans notre culture étant un francophone acadien on veut partager cette culture la. »

61 Anglophone respondents in New Brunswick had no historical narrative comparable to the one frequently invoked by the Acadians we interviewed. Indeed, only one respondent in New Brunswick mentioned Loyalist roots (NB ID 1138), and very few Anglophone respondents made reference to participating in community commemorations relating to the past. One woman mentioned that the ceremony for her son’s marriage took place at Kings Landing (NB ID 1056), a Loyalist heritage site. Another respondent, who almost certainly had Loyalist origins—the mention of both the Mayflower and land grants suggests such an ancestry—reported that family history was most important, but only for personal reasons: “I want to know who they were, what they did, where they fit in society. I want to know my bloodline. Are we from kings or paupers? . . . I'm told the family members came over on the Mayflower and. . .had land grants in the province of New Brunswick” (NB ID 1150).

62 Several respondents mentioned their Irish, Scottish, or English roots, but there was no mention of Culloden, troubles in Ireland, the American Revolution, or other dramatic events that contextualized the arrival of their ancestors in the province. A middle-aged man living in Burton noted that family history was important but only because “It'd be nice to know where everybody. . .came from. . .my mother's [family] are from a different country altogether. The guys with the. . .helmets with horns sticking out of them” (NB ID 1118). The lack of awareness of a larger context for their family history among Anglophone respondents in New Brunswick is striking and perhaps helps to explain the low rate of participation in activities related to the past in a province where the most dramatic history seems to be reserved for those of Acadian heritage.

63 One of the questions that the Pasts team is trying to address is whether interest in family history encourages navel gazing or translates into an interest in the larger historical context. In a few cases, it would appear that intense interest in a family past opens a window on the broader past. An Acadian respondent remarked on the importance of national unity:

64 Another Acadian respondent referred to Aboriginal history in commenting about what should be passed on to the next generation:

65 Significantly, there was no reference in the Acadian sample to the past of Anglophones in New Brunswick, nor did Anglophones mention the Acadians. And none of our respondents raised in specific terms the historical context of Atlantic regional underdevelopment and dependency, which is a major preoccupation of academic historians and the context in which many of the province’s political decisions are made.

Conclusion

66 As historians we understand that our survey captures only a moment in time and that, had it been done fifty or one hundred years ago, the results almost certainly would have been different. Anglophones in the province, including those of Irish Protestant heritage, once boasted of their Loyalist origins. 34 This is no longer the case. In the last decade, the imposing “Loyalist man” guarding the entrance to Saint John has disappeared and little effort is made to commemorate the founding of New Brunswick or any other historical event common to the province. Unlike the francophone school system in the province, anglophone schools until recently devoted little class time to New Brunswick history. Meanwhile, Acadian youth, as probed in projects undertaken by the Canadian and Their Pasts partners, the Musée acadien, and the Institut d’études acadiennes display a strong sense of who they are as defined by language, historical events (the expulsion in particular), and symbols, including the Acadian flag, of which they are reminded on a regular basis in their front yards, on bumper stickers, and anywhere “Acadie” is being celebrated. 35 Significantly, an Acadian flag appeared on the scene well before a provincial flag, which was formally adopted only in 1965.

67 History is never static, of course, and the special relationship that New Brunswick Acadians have with the past may well change in the future. In his recently-published memoirs, Donald Savoie notes that Acadians are unlikely ever to be stronger politically and culturally than they are today. 36 As young people drift to cities outside of the province to find work and adventure, intermarriage with non-Acadians increases, and state support for Francophone culture diminishes. “Acadie,” now an intensely imaginative place for so many Acadians in New Brunswick, may well lose ground to competing pasts for allegiance. This outcome is foreshadowed by the above-mentioned survey of Acadian students in which more respondents claimed to be “citizens of the world” rather than of New Brunswick or of the Maritimes. 37 In this, these young people may be harbingers of where everyone on the planet is headed.

68 In sum, then, there is a noticeable asymmetry in the New Brunswick responses to the Canadians and their Pasts survey. Although it is important to emphasize that our small samples suggest trends rather than definitive conclusions, there is little doubt that many of New Brunswick’s Acadians at the beginning of the twenty-first century have a more intimate engagement with a past than their Anglophone counterparts. Moreover, this engagement seems to lead to a sense of optimism that is less evident among Anglophone respondents, who made few references to historical achievements (or failures) of any kind. Most tellingly, perhaps, there was little recognition among those interviewed of the “other” in their historical space. If we are to move beyond our three solitudes constructed in the eighteenth century, we have to “make history” together. This we have failed to do in the past or, more correctly, we have failed to embrace the past as a shared experience and to tell our story of achievement and failure as a collective one. While it is important to remember our family and community histories, the time is long overdue to think about ourselves more broadly. We have challenges that transcend our narrow historical identities which warrant our attention and demand new narratives about the past. As historians are quick to point out, the best way to predict the future and to shape it to our ideals is to create it.

Display large image of Table 7

Display large image of Table 7

Display large image of Table 13

Display large image of Table 13

Margaret Conrad is an Honourary Research Professor in History at the University of New Brunswick. She has published widely in the fields of Atlantic Canada history and women’s studies. A francophone who grew up in Grand Falls, New Brunswick, Natalie Dubé has an Honours degree in history from the University of New Brunswick and a Master's from the University of Guelph. She transcribed the Acadian interviews for the Canadians and Their Pasts project. David Northrup is Associate Director at the Institute for Social Research (ISR) at York University. He is responsible for the design, management, and implementation of major surveys at the Institute and teaches and advises on survey research methods. With degrees from the University of Saskatchewan, Keith Owre is currently a doctoral student in the Faculty of Education, University of New Brunswick. While having experience in both qualitative and quantitative research methods, his interest in qualitative research interests attracted him to the Canadians and Their Pasts project.