by Joshua S. Krasna

INTRODUCTION: THE CHANGING DEFINITION OF INTERNATIONAL SECURITY

In recent years, the term "international security" has become elastic. In the past, it referred primarily to those aspects of international relations dealing with the actual or implied use of military components of state power in the pursuit of policy. This traditional view served to demarcate "security" from "non-security" issues, with implied precedence being accorded to the former. Its definition of the component elements of national security was couched primarily in military-strategic terms.1

As early as the 1970s, pressures for a broader definition of national security arose in the academic world.2 This new perspective addressed the rise of non-traditional security issues termed "global" or "transnational," which posed threats to many countries or to the international system as a whole, rather than to individual states or groups of states, and which were mostly located on the "fault line" between domestic and international politics, such as energy and other nonrenewable resources, population growth, migration, food, narcotics and the environment. These were not merely incrementally new challenges, stemming from technological or doctrinal developments, to be addressed by new thinking and constructs within the existing military/strategic, state-centered international security paradigm. They necessitated, rather, a broader definition of security, and could only be addressed through multilateral, non-traditional means. This new paradigm was only partially accepted in the academic community, and mostly ignored in the policy establishment (apart from the recognition of economic and some resource issues as components of national security). 3

Changes in the international system in the past half-decade have reduced the salience of many elements in the traditional paradigm of national security, especially the central role allotted to the Soviet-bloc threat to the West. Considerably less concern (and interest) is today aroused by such issues as nuclear deterrence; the strategic arms balance; strategic arms control; the importance of NATO and of the conventional military balance in Europe; and the superpower competition in the Third World, which together encompassed the vast bulk of strategic analysis in government in the past four decades (and to a very large extent defined the scope of academic security studies ). By contrast, the rise in relative importance of a multiplicity of new issues, virtually unaddressed and unaddressable within the terms of the old paradigm, led to new paradigms being bruited. 4

National security establishments, especially in the US, and the security studies community have attempted to formulate new strategic doctrines which reflect new strategic realities. Attention has focussed recently on a series of national security threats which have existed for many years, but were relegated to "second-tier" status due to the pressing need to address what were perceived to be the "central" threats to international security. These secondary security interests were either subjugated to Cold War considerations, or ignored due to their diffuse and long-term (as opposed to acute) character, or the practical impossibility of addressing issues which were multilateral and transnational in a largely bipolar world. However, they are now becoming the main foci of Western national security doctrine.

Many of these "new" international security issues are transnational, rather than interstate, in nature. Moreover, the definitions of national security in the industrialized countries have been expanded from the narrow military-strategic realm to include the protection of vital economic and political interests, the loss of which could threaten fundamental values and the vitality of the state. With a lag of some years, governmental establishments have now begun adopting a strategic world-view based on key aspects of "interdependence" theory, which is more cognizant of the importance of transnational issues, such as economic, social and environmental phenomena, migration, terrorism or ethnic conflict, than "realism." Governments (at least in the West) have already adopted, to a large degree, a broader definition of national security for operational purposes.5

What is a Transnational Issue? The Perspective of Interdependence Theory

Interdependence theorists note the decline in relevance of the concept of "sovereignty" and the difficulty in employing it meaningfully. They note that the nation-state has never been the sole actor in world politics: throughout history a variety of other actors, including multinational empires, multilateral organizations, banks, clans, economic cartels, trading companies, tribes, religious groups, ideological movements and mercenaries, were generally recognized as constituent parts of the global system and its numerous subsystems. While such actors lack sovereignty, many are autonomous and influential. The notion of "sovereignty" and the subordinate concept of "territoriality" served to seal off politics within states from politics between them, and to demarcate the state from its international environment. This led to a neglect of the processes of interpenetration, overlap and societal interaction across frontiers, and of the role of non-state actors in world affairs.6 It seems therefore desirable, in the view of interdependence theory, to think of world systems which are heterogeneous with respect to types of actors, or "mixed-actor" systems. 7

Transnational relations are defined as contacts, coalitions and interactions across state boundaries that are not controlled by the central foreign policy organs of governments. They create a "control gap" between governments' aspirations for control over an expanded range of matters and the capability to achieve it: the problem is not a loss of legal sovereignty but of political and economic autonomy. As governments seek to expand their control over their own societies, they become increasingly dependent on transnational forces impinging on them from outside their boundaries. 8 Global problems are emerging that transcend national boundaries and overwhelm the capacities of individual nation-states; nation-states are becoming increasingly permeable and subject to external penetration. 9 States are well equipped to deal with security threats emanating from other countries, but are much less capable of developing policies and instruments effective in addressing non-traditional issues, which are not state-dependent. Severe problems can arise from the conflict between states and non-state, "sovereignty-free" actors, such as international terrorist or criminal organizations.10 There exist important continuities, as well as marked differences, between the traditional politics of military security and the politics of economic and social interdependence. International conflict does not disappear when interdependence prevails: on the contrary, conflict takes new forms and actually increases.

The increased interdependence between nations, especially the ease of international travel and communications, deregulation and privatization of national economies, the creation through global mass media of a "global" materialist culture leading to growing consumer demand worldwide for leisure products together with the globalization of international finance, has facilitated the emergence of what is, in effect, a single global market (or at least a series of interlinking regional markets) for both licit and illicit commodities. The exponential increase in global trade (tenfold in the past twenty years), has made close controls over imports and exports impossible and thus makes national borders more porous and makes illicit transactions and movements easier to hide.

Illicit drugs have become one of the few truly global products, a product of immense significance (the trade's value is estimated at 300-500 billion dollars annually).11 The criminal organizations which traffic in them are transnational organizations par excellence, in that they operate outside the existing, conventional structures of authority and power in world politics. 12 Much research has been done in the past decade on drugs as a phenomenon of international relations. Most of this work has been by area studies specialists and addresses the linkages of drugs and politics in Latin America, especially in the main producer countries: Colombia, Bolivia, Peru and to a lesser degree, Mexico. A very large portion of the research has been on US international narcotics policy, again especially in Latin America. Other studies (much fewer in number) have examined the political significance of narcotics in specific other countries or regions.

However, little work has been done on the macro level; that is, analysis of the narcotics issue, with all its individual and regional manifestations, as a global phenomenon. This article attempts to derive broader trends and generalizations from the mass of more specific studies, in an attempt to build a macro-model of the significance of narcotics for security studies.

Narcotics Production and Trafficking and International Security

Narcotics may not seem, at first glance, to constitute a meaningful, substantial subject of inquiry for the student of security studies. Drugs are widely viewed as an issue for the criminologist, the sociologist, the social worker, the cultural anthropologist or, in the field of political science, the public policy analyst. The use of narcotics and their trafficking are viewed primarily as issues of law enforcement, of social deviance, and of public health, not of national and international security.

However, narcotics, or more precisely, the control of narcotics supply, have been a subject of diplomacy and international law at least since the Opium Wars between Great Britain and China in 1839 and 1858. In the past decade, as strategic doctrines have been reformulated, at least in the West, especially with the end of the Cold War, the issue of international narcotics has gained prominence. There has been increasing concern in the developed countries, especially the US, and some developing countries about the implications of narcotics cultivation, production, trafficking and use for their national security interests.

It is the contention of this work that narcotics do in fact pose a threat to national, regional and international security, by traditional definitions of "security" as well as by the broader ones outlined above. If security is defined not only as dealing with external military threats but as addressing challenges to the effective functioning of society, then drug trafficking is much more menacing than many issues that have traditionally been seen as hazardous to security. It poses risks to security at three levels: the individual, the state and the international system of states. This threat is more substantial for "source" (or producer) states, 13 and for countries through which narcotics pass on their way from producers to consumers ("transit" countries),14 than for consumer countries, but it exists to some degree for all three.15 The threat is insidious rather than direct: it is not usually a threat to the military strength of the state, but to the prerogatives that are an integral part of statehood.16

NARCOTICS AND SECURITY IN SOURCE COUNTRIES

While source countries have tended to view narcotics as primarily a problem of the consumer countries, the drug trade has serious national security implications for them as well (some of them such as Colombia, Mexico, Malaysia and the West Indian countries have explicitly recognized this fact and included it in their national security doctrines).

The following analysis will analyze the significance of narcotics production and trafficking for source country security using, as a rough organizational framework, Barry Buzan's five dimensions of security. He differentiates between various kinds of security, each of which defines a different focal point within the security problematic, but which are all woven together in a strong web of linkages:

· Political security the organizational stability of states, systems of government and the ideologies which give them legitimacy;

· Military security;

· Economic security access to the resources, finance and markets necessary to sustain acceptable levels of welfare and state power;

· Societal security the ability of societies to reproduce their traditional patterns of language, culture, association and religious and national identity and custom within acceptable conditions for evolution;

· Environmental security the maintenance of the local and the planetary biosphere as the essential support system on which all other human enterprises depend.

17

NARCOTICS AND THE POLITICAL SECURITY OF SOURCE COUNTRIES

Narcotics production and trafficking pose substantial political problems for source country governments and, to a lesser degree, to the governments of transit countries. These states, all of which are LDC's, possess political, economic and social systems which are for the most part fragile, of recent vintage and of contested legitimacy. The primary threat to these states is internal, not external, and the majority of the conflicts which involve them are intrastate, rather than interstate, and result from the fact that while they have been granted international legitimacy, they lack internal legitimacy (they exist by legal right rather than by social fact).18 The political challenges posed by narcotics can therefore join with other political pressures to pose a serious internal security threat to the health, integrity and even continued existence of these states. Where political institutions are relatively strong, traffickers appear to be a troubling but not strongly disrupting influence on national life. Criminal enterprises thrive in states with weak institutions and dubious legitimacy: political chaos provides a congenial environment for criminal activity. For this reason, traffickers have a vested interest in the continuation of weak government in producer and transit states.

One of the major threats posed by narcotics for the source states is the development of autonomous producer/trafficker power and authority, which stems from non-political financial and paramilitary power, parallel to and independent of that of the state. This occurs due to two types of "drug baron" interests: the desire to protect their industry, their livelihoods and their personal liberty; and the inclination to utilize their clout for self -aggrandizement or to promote personal political agendas. In certain states, such as Peru, Colombia, Bolivia and Mexico, we can even speak of two rival parallel states: a formal one run by the central government, and an informal, shadow but no less real one run by the traffickers. On occasion, trafficker power overshadows that of the central government, and the trafficking organizations, rather than the government, represent the ultimate power in the state or at least in large portions of it.

One way such power is accrued is through high-visibility acts of philanthropy and civic responsibility, which promote the trafficker's image as an upright citizen and create a reservoir of goodwill toward him in the populace. In Jamaica, Honduras, Bolivia and Colombia, traffickers have sponsored an array of public works projects, such as clinics, schools, sewage projects, housing developments, church restorations and sports stadiums. 19

Producers and traffickers also form or coopt political pressure groups. In Bolivia, the peasant coca producers have organized eight regional federations, comprising several hundred peasant syndicates, whose primary raison d'etre is opposition to government controls on coca production. These groups have strong support links with politically powerful national mass -membership peasants' and workers' syndicates, as well as with trafficker groups.20 They have repeatedly stymied government anti-drug crop control and law enforcement efforts through aggressive tactics such as mass demonstrations, roadblocks, marches, occupations of buildings and violent clashes with government personnel.21 In Colombia, as the drug lords became rural landowners, they gained a foothold in legitimate associations of farmers and cattlemen, which wield significant influence in the Colombian political system.22 Violent demonstrations by coca growers, which caused the Colombian government to scuttle plans for sharply increased aerial eradication erupted in December 1994 in the southern Colombian departments of Guaviare and Putuyamo.23 In Peru, the coca growers have organized into provincial and district self-defense fronts which lobby for the legalization of coca cultivation and challenge government eradication teams with mass mobilization tactics.24

"Narcocracy"

On occasion, increasing trafficker power in producer or transit states has led to the actual assumption of formal governmental power by elements aligned with the traffickers. In these cases a "narcocracy" has developed. The incumbent regime of a state by definition possesses de jure legitimacy and the monopoly right to use force: in narcocracies, these are harnessed to serve criminal purposes.25 Such a situation can be differentiated from state sponsorship and use of narcotics as a policy instrument, which will be addressed later. In narcocracies, government involvement is not necessarily in the form of using drugs as a tool, but rather as an expression of systemic governmental corruption.

The government of General Luis Garcia Meza in Bolivia between 1980 and 1981 provides an excellent example of the phenomenon. The country's major drug traffickers, concerned by the impending democratic election of a president who had vowed to take a strong stand on drugs, paid the general to lead a coup. The new government bloodily repressed the political left and cracked down on small, unaffiliated drug operations. 26 The new president converted the apparatus of government into a vast official protection and extortion racket, aimed at extracting profits from the cocaine trade. Garcia Meza and his supporters were eased out of office in August 1981, after the US applied pressure, including a suspension of aid, and friction with the drug barons developed over military attempts to take over the cocaine trade.27 This was apparently not the only narcocratic regime in Bolivian history: an official task force on drug trafficking recently accused former Bolivian president (1989-93) Jaime Paz Zamora, as well as his party chief, interior minister and police chief, of providing official protection to a cocaine trafficking ring.28

Panama under Noriega is another clear case of a narcocracy. Noriega, who served as the commander of the Panama Defense Force (PDF) and the de facto ruler of the country from 1983 to 1990, placed his country at the service of transnational drug organizations. His PDF was deeply involved in the trade of drugs and weapons for the Colombia Medellin cartel (in this, Noriega expanded on the precedent set by his predecessor and mentor, General Omar Torrijos, between 1968 and 1981). In return, Noriega and the PDF received millions of dollars in "commissions." 29 The former military leaders of Haiti have been implicated, including in US courts, in drug trafficking.

The base of the support for the renegade regime of Dzhokhar Dudayev in Chechnya was the criminal syndicates in Chechnya and Chechen criminals throughout Russia and Europe, who as of 1994 controlled the smuggling of most contraband and preeminently of Central Asian opium and hashish in the CIS.30

Infiltration and Corruption of Public Institutions

The most serious political problem narcotics engender for producer and transit countries is widespread infiltration and corruption of public institutions at all levels. The drug traffickers possess resources available to few national governments. They can therefore often use money instead of violence, purchasing acquiescence to their wishes, while threatening mayhem if bribes are not accepted. Corruption neutralizes and degrades many social and political institutions, thus limiting the effectiveness of government anti -narcotics activity and the very intensity and scope of state activity.

Drug-related corruption has penetrated bureaucratic and political leaderships in both source and transit countries. Two of the best-known cases are those of Colombia and Mexico. In Colombia, where political campaigns do not receive state funding, drug money is an important basis for the democratic process. Traffickers contribute indiscriminately to campaigns at all levels, with much more success at the local than at the national level, in order to hedge their bets.31 On the national level, the Colombian Congress contains known representatives of trafficking groups; lawyers working for the Cali cartel helped the legislature draft a 1993 reform of the legal system, whose provisions greatly ease plea-bargaining and reduce sentences.32 As of late 1993, the Prosecutor General in Bogota was carrying out 15,0 corruption investigations against government officials. 33 Controversy has swirled around allegations, seemingly substantiated by evidence, that the campaign of President Ernesto Samper, elected in 1994, was partially financed by drug money (as was that of his defeated opponent); his former campaign treasurer alleged that Samper knew about a six million dollar contribution by the Cali cartel to his presidential campaign, and his defense minister and former campaign manager resigned. 34 Washington has bluntly informed Samper that he is "tainted" by the allegations. 35

Mexico has been termed a "narco-democracy" by some US and Mexican law enforcement officials: they claim that the traffickers have accumulated so much power, and the links between them and officials are so widespread, that the government is incapable of combatting them. Major problems broached the surface when President Ernesto Zedillo came into office in 1992, replacing Carlos Salinas de Gortari. Zedillo proclaimed the drug trade his country's number one security problem, citing its potential for penetrating and subverting the institutional structures. 36 His Attorney General uncovered the seamy underside of Mexican politics, exposing the close ties of Salinas' entourage and family, as well as of government officials, especially the Attorney's General's Office and the police, and of prominent individuals in the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), with prominent Mexican drug gangsters. Salinas' brother, Raul, arrested for murder, was implicated in such ties it is alleged that a major figure in Mexico's cocaine cartels provided funding for "dirty tricks" in Salinas' campaigns as was the former president's former chief of staff. 37 A series of political assassinations in 1993 and 1994 have been laid at the cartels' doors.

While these two cases are the most fully documented, high-level corruption has affected many other source and transit countries as well. For instance, several top officials were indicted, and five ministers resigned or were dismissed, in the Bahamas in 1985. The prime minister was also suspected of taking bribes, but the charges were dropped for lack of evidence.38 It is reported that the new governments in the poppy and cannabis cultivating successor states in Central Asia are rife with drug-related corruption: in Kazakhstan cultivation of opium poppy is legal; and in Uzbekistan leading drug dealers are said to hold official positions. 39 Druze leader Walid Jumblatt has alleged that three-quarters of the current Lebanese cabinet has been involved in drug trafficking.40 A member of the Lebanese parliament was arrested in November 1994 for drug smuggling and claimed that parliamentary deputies, a minister and the son of president Elias Harawi were also linked to the drug trade.41 Alleged traffickers sat and sit in Pakistan's cabinet and National Assembly, and though a 1990 law bars known traffickers from running in elections drug barons continue to exercise a pervasive political influence.42 Several individuals who have been denied US visas due to suspected trafficking activity, including the deputy leader of the new ruling party (reportedly suspected of earning 400 million dollars from marijuana trafficking), were considered in July 1995 for cabinet posts in the new civilian government in Thailand.43 The Chief Minister of the Turks and Caicos Islands and his Minister of Commerce and Development, were arrested in Miami on drug-related charges (conspiring to protect drug transhipment) in 1985.44 Finally, the Zambian foreign minister, social affairs minister, national police commissioner and deputy speaker of parliament resigned in January 1994, amid charges of trafficking in synthetic drugs (they were later acquitted in court), and the scandal may have included other cabinet ministers as well.45

The very military and security forces that are responsible in many source countries for counternarcotics operations have often been intimately involved in drug-related corruption, a fact which has seriously impeded government anti-drug efforts. Militaries, and especially police forces, in the source countries are usually extremely low-paid, creating opportunities for corruption. In most developing countries, the military is a potent political force; if it is subverted, the entire political process may be at risk.

Many examples of security force involvement with the drug trade can be cited. The Minister of Public Works and Communications (son of the Prime Minister) and the commander of the Defense Force of Antigua -Barbuda were involved in a complex plot to purchase Israeli-made weapons for the Medellin cartel using forged Antiguan end-user certificates. 46 In Bolivia, the military has been closely tied to the trafficker community through an array of financial ties and through a shared hostility to democracy.47 Severe drug-related corruption was reported in the Colombian police and army throughout the 1970s and 1980s.48 US officials have recently hinted that the chief of Colombia's national police had received money from the drug cartels (the charges were hotly denied); and over 14,000 police officers have been dismissed since 1991 for corruption. 49 In August 1994, 51 officers of the Cali police force were dismissed for passing on information about the operations of the country's special anti-drug unit to the cartel.50 The Haitian National Intelligence Service, a covert counternarcotics intelligence unit set up with CIA assistance, was heavily involved in trafficking. The situation has been most fully documented in Mexico where high-level police officials at the state and federal levels, including the former director of Interpol-Mexico, actually engaged in drug smuggling.51 As a result of US pressure, the Federal Security Directorate (DFS), which operated in league with major drug traffickers involved in the torture-murder of a US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agent, was disbanded in 1985. According to some US officials, the corruption within the law enforcement and military systems in Mexico is so pervasive that it effectively precludes effective and meaningful bilateral counternarcotics cooperation. Several high-ranking government officials, including a national police superintendent, were arrested in Nepal in 1987. 52 Drug-related corruption is rampant within every law enforcement body in Nigeria. 53 In Thailand, senior military personnel, some of whom are opposed to the new civilian government and desire restoration of military predominance, were in the past closely allied with the Burmese government and the Chinese warlord organizations (whose headquarters were often located in Northern Thailand), and facilitated policy.54 The Thai government in 1994 reorganized some units and transferred responsibility for border closure from the organizations traditionally charged with the task to military units with fewer traditional ties to the insurgents, with measurably positive results. The Commissioner of Police of Trinidad and Tobago resigned in 1987 and several senior officers were reprimanded or suspended in 1992, due to drug-related corruption. Finally, senior officials of Venezuelan military intelligence have been tied to trafficking.55

Territorial Autonomy

Apart from the concentration of autonomous political power in the hands of traffickers, and their penetrations of the political system, narcotics producers and traffickers in many source countries have achieved effective control over territory. A "state-within-a-state," affording sanctuary to the illegal drug trade, is thus created, where local strongmen can act as absolute rulers and block the central government from enforcing its writ. Such a situation exists in many regions of the Andes and Amazonia, and in the remote border regions of the Southeast Asian "Golden Triangle" and the Southwest Asian "Golden Crescent." These production regions are usually remote, inaccessible, and underdeveloped relative to national urban centers and coastal zones; political, economic and administrative integration in them is much more tenuous.56 In addition, they are in many cases populated by indigenous peoples or ethnic minorities who reject political and cultural control from the center, and who may have a tradition of drug use for cultural, religious or medicinal purposes. The central governments are often chronically unable to project their authority to these areas, which is one of the reasons the drug trade flourished in them in the first place. The connection between narcotics and insurgencies/revolutionary movements will be addressed in more detail below. The high value-to-weight ratio of narcotics means that the marketing of economically significant amounts does not require sophisticated transportation infrastructures and makes them a cost-effective cash crop for remote, undeveloped areas. 57

In Pakistan, for example, opium and heroin production are concentrated in the tribal areas of the remote, mountainous Northwest Frontier Province, where, until recently (1995), local leaders were virtually a law unto themselves, since the government was unwilling to press them for fear of pushing them into open resistance to Islamabad. 58 Morocco's cannabis cultivation is concentrated in the Rif region, a virtually autonomous and underdeveloped area ruled by the Spanish until 1957 and isolated from the rest of the kingdom by poor roads.59

The final result of all these encroachments in the realm of the state, and especially of the apparent inability of the governments involved to effectively counter them and to enforce the rule of law, is to undermine state institutions and the legitimacy of the political system in the eyes of the public. The resultant strains on the already weak legitimacy of democratic political systems in many producer countries may lead to a detachment of the public from the political realm, such as is seen in authoritarian and totalitarian societies, leaving it to the traffickers. They may also lead to increasing popular willingness or even pressure, to accept limitations on democracy and authoritarian rule in order to control endemic violence, corruption and social decay. Some analysts see substantial potential for such a scenario in the former communist countries.

Narcotics and the External Political Relations of Producer States

Quite aside from the effects of narcotics on internal security and stability in source countries, they also pose serious problems for their external relations. Association with narcotics can seriously tarnish the image of a source country in the international arena.60 This can hinder efforts by the source country to obtain foreign aid, as well as expose it to retaliation by consumer states, who may see in trade and aid sanctions the needed leverage to compel source countries to pursue more effective drug control policies.

The US government, for example, has been compelled since 1986 by Congressional legislation to certify major drug-producing and transit countries as having cooperated "to the maximum extent possible" with US narcotics reduction goals, or as having taken adequate steps on their own in keeping with US goals. If certification is withheld from a state (that is, if it is "decertified"), the law requires automatic suspension of one half of the economic and military assistance designated for that country and opposition to any loans to it by multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund or the Interamerican Development Bank. The legislation also empowers the president, at his discretion, to further deny preferential tariff treatment, impose punitive duties on imports, or deny airport landing rights in the US. Imposition of sanctions can be avoided if the president certifies the existence of overriding "vital national interests" regarding the offending state.61 On the multilateral level, the 1988 UN Convention mandates the application of sanctions for any activity carried out with the intention of participating in drug trafficking. 62

Another serious foreign policy effect of narcotics is the increased potential, in the absence of effective source-country policies, for external intervention, especially by the US, in the producer countries. The US has exerted significant pressure on source countries to do more to control narcotics. It has also on occasion pursued unilateral anti-drug policies effecting source countries without prior consultation or even warning, often out of exasperation with perceived inaction. These policies have involved substantial infringements of sovereignty. For example, US prosecutors have in recent years made increasing use of criminal indictments against foreign leaders and their advisors based on crimes committed entirely outside US borders, utilizing a broad interpretation of extraterritorial criminal jurisdiction. In addition, US DEA agents have made increasing use of kidnapping in foreign countries as a way of bringing offenders before US courts.

NARCOTICS AND THE MILITARY SECURITY OF SOURCE COUNTRIES

A major security problem for the governments of source countries is the proliferation of sophisticated arms, communication equipment and ancillary equipment in the hands of narcotics organizations. Many cartel personnel undergo advanced training, usually under Western mercenaries, as well. The absolute financial superiority of the traffickers over governments thus translates into actual military and material superiority.

Narcotics and Insurgent/Revolutionary Movements in Source Countries

A growing number of indigenous source-country revolutionary organizations, terrorist groups and insurgents have obtained funds and other assets, principally arms and military technology, through illegal drug-related activities. Both trafficker and insurgent/terrorist organizations function primarily in remote areas where government control is weak. The extensive collocation of areas of insurgency and those of narcotics production usually provides an incentive to both sides to pursue policies of cooperation, or at least coexistence, rather than confrontation.63

The interests of the two sides served by cooperation differ. Trafficking in drugs provides insurgent and terrorist groups with an opportunity to develop substantial independent sources of income. This is of the utmost importance, as external support from traditional sources the Eastern bloc, Libya and the People's Republic of China (PRC) has dwindled. The traffickers also provide access to secure transport routes and communications; intelligence; corrupt officials; and more sophisticated arms and technology. 64 These advantages may even bring rival groups to cooperate with each other in trafficking, while they are in conflict in other spheres; such was the case in Lebanon during the civil war.

The drug traffickers, for their part, act to a large degree out of the necessity to achieve a modus vivendi with forces that control the areas in which they function. They also achieve access to organized, disciplined and trained cadres for operational security or for use against governmental targets. In addition, as Grant Wardlaw notes, by supplying the terrorists with arms and thereby increasing the security threat to the governments, they encourage the latter to pursue a strategy of counterinsurgency, which is usually associated with a de-emphasis on counternarcotics activity. 65

There are, however, also substantial disincentives to cooperation or even nonbelligerence. The long-range aims and ideologies of the two parties, as well as their economic interests, are fundamentally incompatible. Insurgents and terrorists often wish to remake society and may have strong ideological misgivings about cooperating with criminals who, to them, represent the very worst of parasitical bourgeois values. 66 Traffickers, on the other hand, are generally capitalist "robber barons," who champion the political and economic status quo and wish to advance within it. They presumably realize that there would be little place for them in the kind of society visualized by most revolutionaries.67 In addition, the traffickers' desire for maximizing profits and minimizing costs does not coincide with the insurgents' desire to ensure the growers' loyalty by assuring high prices for their product and to maximize revenues from taxes. Thus, while limited "marriages of convenience" between insurgents or terrorists and traffickers are quite feasible and benefit both sides, in the long run coexistence is problematical, except in those cases where the two are identical.

Southeast Asia

In the "Golden Triangle" area of Burma, northern Thailand, eastern Laos and the southern Yunnan province of China, the insurgents and the traffickers are one and the same. The region is home to a multitude of ethnic groups, all of which seek to maintain distinct identities, making insurgency the dominant form of regional politics. 68 Up until the early 1950s, ethnic minorities cultivated opium for their own use or, at most, for the regional market. The introduction into northern Burma of renegade Nationalist Chinese elements, which traded in opium to finance their efforts to overthrow the communist regime in Beijing, and the accession in Rangoon in 1962 of a socialist government committed to curtailing minority rights, led to an explosion and internationalization of trafficking in the region. 69 The control of trafficking by the insurgents and the Chinese in the Golden Triangle is much more direct than in almost all other regions; the dominant form of interaction is not accommodation, but functional integration. 70 Each group of insurgents exerts effective control over a geographical area, in which it also controls trafficking.

Southwest Asia

Effective control of trafficking by insurgents seems also to have existed during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. As in the Golden Triangle, the exigencies of Cold War insurgency politics transformed a regional operation into a global phenomenon. Between 1980 and 1983, production tripled in areas held by the mujahedin.71 The deliberate Soviet policy of starving the insurgents by destroying food crops, the destruction that the war wreaked on the agricultural sector and the indifference of the pro-Soviet government in Kabul to this sector compelled increasing reliance on opium cultivation in those areas beyond government/Soviet control. Local administrations established by the mujahedin supervised the farming, in which guerrilla troops participated. The profits were used for subsistence and for purchases of weapons and supplies in Pakistan, using the large refugee community. 72

Elsewhere in Southwest Asia, the Kurdish region of Turkey is the center of heroin refining, and the separatist Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) have financed their rebellion largely through heroin trafficking. 73 Urban terrorists in Turkey the leftist Dev-Sol and the rightist "Grey Wolves" have also sold heroin to finance arms purchases from Bulgaria, 74 as allegedly have the anti-Turkish Armenian terrorist group ASALA. Illicit opium cultivation in India is concentrated in the states of Jammu, Kashmir and Uttar Pradesh, where active separatist organizations and political disturbances hamper effective law enforcement.75 Tamil separatists in Sri Lanka are apparently funding their separatist struggle by trafficking heroin through compatriot networks in Europe and Canada.76

Latin America

In Latin America, the operative model for relations between insurgents /terrorists and traffickers is less one of control than of situational accommodation and sometimes cooperation. The ideological component is much more important in the Colombian and Peruvian insurgencies and revolutionary organizations than in those of Asia. This serves, as noted above, as a brake on the development of too intimate a drug/insurgency nexus.

Sendero Luminoso (the Shining Path) began as a fanatical Maoist, extremely violent urban revolutionary organization in the Ayacucho region of southern Peru. Under pressure of government counterinsurgency campaigns, it shifted operations in late 1983 to the Upper Huallaga Valley in the north, a remote, inaccessible area which is one of the world's major centers of coca growing, supplying some 40 percent of the world's crude cocaine. 77 In the Upper Huallaga, Sendero was able, in accordance with Maoist revolutionary doctrine, to take advantage, until the government reestablished control in the region in 1992, of popular dissatisfaction among the Indian coca growers with government anti-drug policy pursued in cooperation with the US and with trafficker excesses. This enabled them to gain peasant support and, posing as the protector of the peasantry, to achieve substantive political control over the area. It is reported that it even joined forces with the traffickers to form and train anti-government militia forces. 78 Sendero also inserted itself as a middleman between growers and mostly Colombian traffickers, ensuring a fair price for the former and representing their interests and thus cementing their loyalty, while imposing taxes on the latter to finance revolutionary activity and bringing an end to their dominance of the valley.79 Sendero also protected drug shipments, warned of impending raids, and guaranteed grower discipline and the timely meeting of demands for raw materials.80

In return, apart from political benefits, Sendero is alleged to have received approximately thirty million dollars a year from involvement in various aspects of the drug trade. It is also alleged that Sendero took one fifth of the growers' harvest as a revolutionary tithe, which they then processed into paste and sold or bartered to the traffickers. 81 As noted above, the two parties' interests were not identical, and there were bloody clashes; however, they usually managed to set aside their differences and cooperate in the face of government pressure. The trafficker-insurgent relationship is even more tentative in Colombia than in Peru, where the traffickers must take into account Sendero, which is effectively sovereign in the production area. In Colombia, the nature of the tie is closer to a pure "marriage of convenience" rather than a "shotgun wedding."82 The most active of the four Colombian insurgent groups involved in the drug trade is FARC, the armed wing of the Colombian Communist Party and the oldest revolutionary organization in Colombia. It is predominantly a rural-based insurgent organization which largely controls the coca-growing areas of the country.83 Approximately half of FARC's 33 "fronts" collect tribute from coca growers, provide drugs to the traffickers in exchange for arms, levy taxes (10 percent) on drug operations and shipments in territory under their control, and may even cultivate and refine cocaine directly.84 It appears that they have also taken a share of the growing opium trade. FARC has also guaranteed trafficker access to covert airstrips in areas under its control, provided traffickers with protection and warning of police and military movements, and on occasion, interfered with these forces in the course of counternarcotics operations.85 Like Sendero, FARC functions as an armed trade union representing the growers, by fixing prices for labor, agitating to maintain high paste prices and preventing abuses by cartel personnel.86

The links of M-19, a much smaller, more urban-oriented organization than FARC, to the traffickers are less those of an insurgency sharing territory than of mutual utilization for strictly defined purposes. The most prominent example is the terrorist occupation of the Palace of Justice in Bogota, in which nine Supreme Court justices were killed and legal documents related to pending narcotics and extradition cases were destroyed. It is widely believed though compelling evidence has not been presented that M-19 was "contracted" for one million dollars to carry out this attack, as part of the Medellin cartel's attacks on the judiciary over government extradition policy.87

As in Peru, the contrary goals and interests of the traffickers and the guerrillas/terrorists in Colombia cause the ties between the two sides to fluctuate between coexistence/cooperation and conflict. Serious clashes have occurred between FARC and the traffickers over taxes on the drug traffic, leading to escalating reprisals and counter-reprisals. 88 In addition, as the drug lords bought tracts of land in the rural guerrilla zones and thus replaced the old landowners, they have refused to pay protection money to the rebels and have instead fielded large private armies and massacred peasants suspected of supporting the guerrillas.

Eastern Europe

Another, more recent, relationship between traffickers and insurgents seems to be developing in the former Yugoslavia, one of the world's leading producers of opium before and between the world wars. Albanian separatists may be trafficking in heroin in Switzerland they are alleged to control up to 70 percent of the market there in order to buy arms and support terrorist activity against Serbian authorities in Kosovo and Metohija and to prepare for possible unrest in Macedonia.89 Finally, Croat nationalists were involved in drug trafficking before achieving independence. 90

Narcotics trafficking has also been used by international, as distinct from domestic, terrorist groups to purchase arms and finance their activity, especially as support from the Soviet Union and its allies dried up and the organizations were forced to find other, steadier sources of income.

Trafficker "Mega-violence"

A major drug-related threat to governments in the developing world is the use by traffickers of what Martin and Romano term "megaviolence" politically motivated, systemic, large-scale, sustained violence, using terroristic tactics such as assassination, kidnapping and threats against establishment targets. Such activity is usually aimed at paralyzing the government, at forcing a change in counternarcotics policy, or at intimidation or even elimination of those responsible for this policy. Used in conjunction with financial blandishments, known as plata o plomo or "silver or lead," this strategy has on occasion attained a high measure of success. 91 This type of terrorism is essentially different from that practiced by political terrorists and insurgents, since it seeks not to overthrow or replace the government, but to intimidate or neutralize it. The preeminent example of drug cartels using this form of terrorism has been found in Colombia. 92

The Eastern Caribbean island state of St. Kitts and Nevis, an important cocaine transit point between Colombia and the US Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, was embroiled in drug-related violence in 1994. A senior police superintendent investigating the involvement of the deputy prime minister's sons in trafficking and murder was assassinated. The unrest culminated in riots, which stabilized only after military forces from neighboring countries were called in.93 Jamaica has also suffered a sharp upsurge in narcotics -related violent crime and gang warfare.94

NARCOTICS AND THE ECONOMIC SECURITY OF SOURCE COUNTRIES

Drug production and trafficking pose two types of economic threats to source countries. First are those posed by overdependence for export earnings and foreign currency on commodities whose production and marketing are illegal in most source countries; are forbidden by international agreements; are dependent on developments (consumption patterns and effectiveness of law enforcement and anti-drug measures) outside their borders and control; and are, therefore, highly volatile. Second are those posed by dislocation and distortion of the economy.

The importance of drug production for source countries grew substantially in the 1970s and 1980s when their economies became "addicted to drugs."95 This was due to sharp declines in the prices of the legitimate primary commodities upon which most of these countries depended for export earnings. Many were "one-product economies" and therefore quite vulnerable to shifts in global supply and demand for their products. Between 1980 and 1988, sugar prices declined by 64 percent; coffee by 30 percent; cotton by 32 percent; tin by 57 percent and crude oil by 53 percent.96 Sharp declines in commodity export earnings led to a worsening of many producer countries' debt burdens and a crisis in their foreign currency holdings. The need to alleviate these burdens forced many of these countries to embark on long-range stabilization programs, leading to divestment of subsidized state-owned companies and termination of unproductive private industries.97 This led, in the short-term, to substantial unemployment in the source countries.

The illegal drug industry has served as a cushion and safety-valve for these severe macroeconomic effects, providing export income, employment and foreign exchange when the formal economy falters. The drug industry often the only sector still expanding provides employment for large numbers of displaced rural and urban workers, thus alleviating social and political pressures associated with high unemployment rates in other sectors, which financially strapped source-country governments can do little to address.98 It also affords many previously marginalized individuals the chance to earn more money, experience more social mobility and exercise more power over their destinies than ever before.

Apart from its ability to absorb surpluses in the labor market, the drug industry also aids source-country economies by generating export earnings and foreign currency, often in excess of those obtainable from legal sources.99 In addition, drug production and trafficking have substantial multiplier effects on domestic demand in producer states: providers of services and producers of status goods have thrived, and well-off traffickers have invested heavily in local business. The governments of source countries have, despite their declaratory anti-drug policies, developed methods of generating revenues from illegal export earnings, and facilitating their flow into the legitimate economy. For example, many of them do not have laws outlawing money laundering.

The massive dependence of source-country economies on drug production and trafficking for stabilization of the currency, for relieving unemployment and for boosting demand leave these states open to dislocations and distortions stemming from the nature of the drug trade. The erratic nature of drug trafficking (and of traffickers), which may necessitate immediate transfers of enormous volumes of money without notice, and the creation of a volatile, artificially-based cash economy, can destabilize local exchange rates and money supply, since the financial systems in these countries are permeated by drug money.

The influx of large amounts of narcotics profits, only part of which are funnelled through officially sanctioned channels, also contributes to the creation of a parallel, underground economy. Expansion of the underground economy leads to dwindling activity by legitimate firms and thus to a shrinking of the government's tax base; the government is also unable to develop effective fiscal and monetary policies because of inadequate and distorted information about the real state of the economy. 100 The "laundering" of money through investments in luxury real estate has priced lower and middle income families out of the housing market, while government construction projects stall for lack of adequate funding at the inflated levels.101 These trends have also shrunk the pool of money available for lending to legitimate businesses and thus raised interest rates on credit. Much of the drug money is spent on conspicuous consumption of luxury consumer goods, a trend which aggravates inflation while not serving any socially or economically productive purpose, and does not improve the overall quality of life.

All this has severely exacerbated the already inequitable distribution of income and wealth in the producer countries. The "boom" economies serve an extremely small sector of society with little or no downward linkages. They have actually worsened the economic situation of the mass of the population, whose income has not been augmented in a major fashion even the growers' income is only slightly above subsistence level but who face rising prices, especially for basics like food and transportation, and shrinking official development programs.

One of the most profound economic effects of the narcotics trade has been in the agricultural sector. Cultivation of coca, cannabis and opium usually provides a much higher return for growers than other crops, especially when world markets for the other products are depressed. For example, in 1993, a kilo of hashish fetched 50 times more for a Lebanese grower than one of potatoes, 15 times more than wheat and one hundred times more than apples; and opium was worth twice as much as hashish; 102 Mexican farmers in the 1970s could make five to ten times more by growing opium poppy than traditional crops;103 in 1994, in Peru a hectare of cacao earned about $400, and one of coffee about $1300, while a hectare of coca brought in $10,000;104 in 1992, a hectare of Uzbek opium could earn 20 times more than cotton and 35 times more than vegetables.105 Cultivation of these crops has other advantages. Opium is an autumn-grown crop harvested in the spring, which means that fields can be replanted with other crops for the summer.106 Coca matures in three years and then can be harvested three times a year, affording it great advantages over slower-growing alternatives. Moreover, it also requires very little labor apart from harvesting after maturation.107 Cannabis grows in soil, water and climate conditions not conducive to other alternative crops.108 In addition, the cartels often offer farmers agricultural credit and take care of the transportation of the harvest.

The relatively high wages in the drug production areas have led to mass migrations of peasants to these areas, leaving labor shortages in traditional agriculture and in other sectors of the licit economy. In addition, the greater profitability of drugs has led to conversion of crop lands to opium, cannabis and coca production. In Latin America, this has led to shortages in such staples as corn, rice and potatoes, and food prices have been forced up by rising labor costs and decreasing supply. This has dictated increased imports of food, which causes a drain on foreign currency reserves.109

NARCOTICS AND THE SOCIETAL SECURITY OF SOURCE COUNTRIES

Domestic Drug Abuse

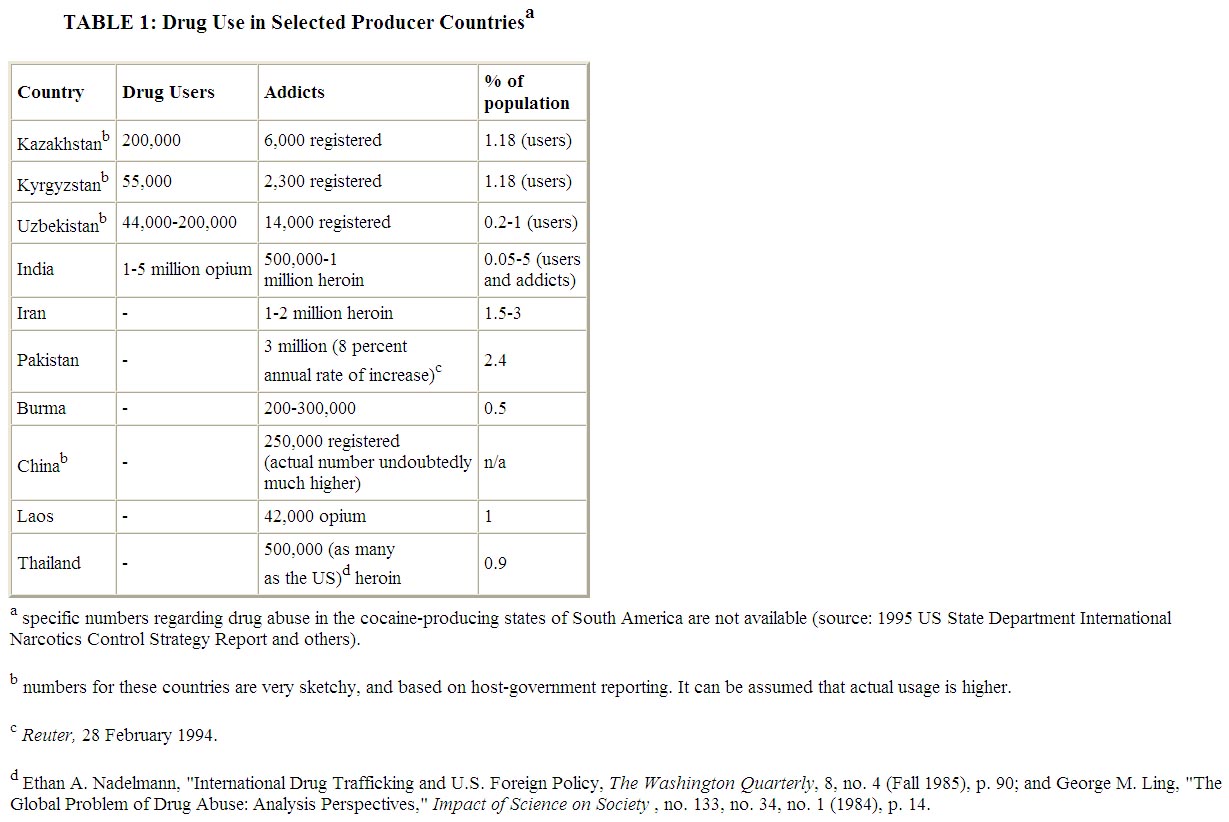

While drug abuse is widely viewed in producer countries as primarily a problem of the "consuming" developed North, it has become clear that drug abuse has also seriously affected countries in which narcotics are produced or through which they pass. (See Table I) This is due partially to the ready availability and thus, low price of drugs in these countries and to the benign attitude with which drug use is generally viewed in them, as well as to conscious efforts by traffickers to develop local markets in order to absorb surplus production. Success in international narcotics control efforts and especially in interdiction of drug flows to industrialized countries may exacerbate this problem, since it decreases the amount of drugs able to be exported and thus increases incentives for producers to "dump" overproduction on unprotected markets. In addition, narcotics offer a seductive reprieve from the desperate social and economic situation in many of the producing countries.110

The rise in domestic drug use in producer countries has primarily affected groups on the margins of society the urban poor and indigenous populations but has also made inroads into the middle and upper classes.111 In Colombia, Peru, Bolivia and Venezuela, the abundance of cheap cocaine has led to a tremendous rise in use of "basuco" or "pitillo": tobacco or marijuana cigarettes laced with coca paste, which are much more addictive than "snorted" powder and have many more impurities, some of them lethal.112

As noted above, "transit" countries, where narcotics are not grown or produced, but are transshipped from producer to consumer, have also suffered an increase in addiction, due to "leakage." 113 Crack houses sprang up in Belize, a major new cocaine transshipment point, in the late 1980s and early 1990s.114 African transit countries, especially Nigeria, Ghana, Madagascar, the Ivory Coast, and Mauritius, are suffering increasing drug abuse problems as well.115

Other Social Effects

In many societies the traffickers have formed a nouveau riche which seeks to bully and buy its way into social respectability, threatening the traditional social structures; the prime example of this phenomenon is Colombia. The glamor of the drug gangs attracts new generations to the drug trade and leads to the glorification of traffickers as role models, contributing to social and value anarchy. The traditional lifestyles of the indigenous communities in the producing areas have been disrupted and transformed. More generally, in Latin America the endemic violence and massive levels of corruption have led to a general breakdown of respect for law, of "social contracts" and thus, of civil society. Endemic "mega -violence" in many producer countries, and especially the inability of the governments of producer countries to effectively counter it, can lead to a breakdown in social order and an explosion of "ordinary" crime.

Thus, some producer and transit countries suffer severe social ills, similar to those in the consumer countries, stemming from the international drug trade. These include crime, the spread of infectious diseases, especially AIDS and hepatitis, and rising medical and social welfare costs. The social impact in developing countries of problems associated with drug addiction may actually be worse than in the developed world. These countries, as a rule, have virtually no treatment and rehabilitation facilities, and less developed law enforcement institutions to deal with the increased street crime associated with widespread drug abuse. It appears that realization of the magnitude of these problems has led to an increased willingness on the part of some producer countries to act effectively against drug production and trafficking.

NARCOTICS AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL SECURITY OF SOURCE COUNTRIES

Drug production, and attempts to control it through crop eradication, have caused substantial damage to the environment in producer countries. This is doubly serious, since most drug cultivation occurs in largely underdeveloped, ecologically unique and fragile regions, especially rain forests in South America and Southeast Asia.

Drug growers in Latin America, for example, use "slash and burn" techniques to clear land, causing deforestation, erosion and eventually depleting soil resources. The producer tactic of shifting the locations of operations regularly in response to official counternarcotics efforts multiplies this destructive effect.116 The need of cultivators in Peru to distance themselves from government surveillance has forced them to move deeper and deeper into areas which were previously virgin rain forest. Peruvian sources estimate that new coca cultivation destroys 500,000 acres of Peru's Amazon rain forest each year.117 In addition, the forty or so different precursor chemicals used to process cocaine in the primitive laboratories operated in remote areas by the trafficking organizations are routinely dumped into streams and ditches and thence pollute both groundwater and surface watercourses.

In the words of one analyst, "drug traffickers have created a toxic waste dump of [Peru's] Upper Huallaga Valley." 118 It is estimated that 38,000 tons of chemicals are dumped into the rivers of Bolivia's Chapare region from whence they eventually reach the Amazon each year. There are now areas of the Chapare where new crop cultivation cannot be commenced for at least a decade.119 Similar conditions may exist in Southeast and Southwest Asia as well, where the environmental effects of drug production have not been as closely investigated.

RISKS TO SOURCE COUNTRIES FROM COUNTERNARCOTICS POLICY

The security threats posed for producer countries by the continuation of the drug trade as outlined above do not necessarily lead to the enactment of counternarcotics policies by their governments. There are substantial national security risks involved in a vigorous pursuit of a counternarcotics policy as well.

While narcotics pose a threat to the state's political system and, in the longer run, to their economic and social systems as well, in the short run, they contribute to economic recovery and to peace in the countryside. Counternarcotics operations, especially eradication, have a severe negative impact on growers, who depend on narcotics cultivation for subsistence and generally lack either profitable crop alternatives or other means of livelihood. Government drug policy can therefore exacerbate rural poverty and substantially increase unemployment. It also harms prospects of advancement and employment for urban shantytown dwellers, especially youths, who often serve as low-level dealers, couriers, enforcers and assassins. This in turn can fuel anti-government or separatist sentiments among the affected populations and drive them into the camps of insurgents or revolutionaries, thus exacerbating, rather than alleviating, security problems.

For this reason (among others, including institutional corruption), military officials often oppose counternarcotics efforts, as contrary to the goal of counterinsurgency strategy, which is driving a wedge between the populace and the insurgents. They have even on occasion prevented anti -narcotics police from operating, including through use of force. In Asia and Latin America, drug trafficking organizations actually collaborate with government forces in combatting ethnic and communist insurgents. Opposition by the military to an emphasis on counternarcotics activity may generate crises in civil-military relations and even precipitate military coups.120

Despite these concerns, much of the anti-narcotics activity undertaken by some countries in the past decade has been characterized by greater reliance on military means to counter trafficker violence and to eradicate drugs in the countryside, in part as a result of US pressure. Much of American counternarcotics aid has gone to military and internal security forces in source countries. This militarization of the drug war poses grave risks for the regimes in producer countries, especially those that are democracies, many of which only recently emerged after a long history of military or civilian dictatorship, and are still fragile. The military often demand restrictions on democracy and civil rights, as the price of effective counternarcotics strategy. They may also demand increasing control of scarce financial resources. Militarization of the effort is also often associated with widespread human rights abuse, which serves to further alienate the government from the people. These will all tend to strengthen the military at the expense of the civilian governments and lead to an increasingly authoritarian trend in the political system, imperilling and marginalizing democratic institutions. In addition, cooperation with consumer countries in these efforts may serve as a catalyst for nationalist, anti-interventionist usually anti-American sentiment among the population. This can further alienate them from their own governments and even radicalize them and promote their identification with opposition groups.

Vigorously attacking the drug trade can also have severe macroeconomic effects in the producer country, quite apart from its impact on rural and urban unemployment. As we noted above, these countries are often dependent on trafficker income for foreign exchange which stabilizes the currency, and for bolstering weak domestic demand, especially in the wake of the collapse of prices for licit commodity exports.

Of course, pursuing an effective counternarcotics policy will also bring the governments of the source countries into direct conflict with the drug traffickers. A serious threat to their livelihood and way of life might well lead the traffickers to wage all-out war against the offending government, in order to topple it and replace it with a more amenable one.

NARCOTICS TRAFFICKING AS AN INSTRUMENT OF STATE POLICY

Narcotics production and trafficking is not undertaken only by transnational criminal organizations or by revolutionary/insurgent movements. Narcotics have been utilized by the governments of certain states in certain periods to further their foreign policy and national security agendas. Such state sponsorship of the international narcotics trade is not a modern phenomenon. The colonial government of India under Great Britain in the nineteenth century, the French colonial government in Indochina in the same period and the Japanese in Manchuria in the 1930s all supported the drug trade, as a means of defraying the costs of their colonial enterprises. 121

Modern state sponsorship of drug trafficking may have several goals. They include corrupting, subverting or destabilizing targeted societies through calculated "political warfare;" obtaining hard currency, including for finance of intelligence activities and covert action; funding and supporting terrorist and insurgent organizations associated with the sponsor, including exchanging drugs produced by these organizations for arms and afterward marketing the drugs; and, utilizing ties developed with trafficking organizations as intelligence collection or covert action assets.

In more recent times, the role of communist states in international drug trafficking has been stressed. This began with the efforts by US policy makers, especially Henry Anslinger, director of US anti-narcotic policy from 1930 to 1962, to fix the blame for the rise in American drug abuse on a calculated policy by the PRC.122 In the 1980s, conservative scholars claimed to have documented the widespread involvement of the USSR, the East European satellites, Cuba, Nicaragua, Syria, North Korea and Vietnam in state sponsorship of drug trafficking. One of them, Yonah Alexander, claimed that "drug trafficking is an important element of low-intensity conflict; it is calculated political-military struggle short of conventional warfare undertaken by states and their sub-state proxies in order to achieve ideological and political objectives."123

Despite these claims, there is no convincing evidence of a globally cohesive plan to utilize drug trafficking as an element of revolutionary war.124 This said, it seems that there has been some, or even substantial, involvement by government officials and entities, especially intelligence services, of communist countries in international narcotics trafficking. However, this activity utilized existing organizations and markets to pursue specific governmental purposes. It stretches credibility to believe that the international drug trade was a creation, rather than an instrument, of communist policy. One indication of the truth of this observation has been the fact that communism's demise has not led to a significant decline in drug production and trafficking.125

Some communist states were, or still are, more intricately involved than others. The Bulgarian government under communist rule served as a major conduit mainly through an official trading company, KINTEX for heroin and hashish moving from Southwest Asia into Europe and the United States, in some cases actually refining heroin and morphine base in its own facilities.126 At one point, 25 percent of the heroin in the US was estimated by the DEA to have transited Bulgaria.127 The goals of Bulgarian drug trafficking were not, apparently, to wage "political warfare" against the West, but rather to use the proceeds to provide assistance to international terrorist organizations; to utilize ties with criminals for intelligence collection purposes; and to finance intelligence activities.128

The former Sandanista government of Nicaragua was also implicated in narcotics trafficking. There is substantial evidence that Thomas Borge, former Minister of the Interior and head of Nicaraguan intelligence, and his aides cooperated with the Colombian Medellin cartel in transhipment of cocaine to the US.129 It is unclear to what extent these activities reflected state policy, as opposed to personal corruption on the part of the officials involved. However, the activity was certainly known to the Sandanista government and therefore at least tacitly condoned by it. It appears that this attitude stemmed from practical interests, similar to those of Bulgaria, in obtaining hard currency, and in facilitating smuggling of arms (using cartel channels) to terrorist and insurgent groups supported at the time by Managua.130

The implicated regimes in Sofia and Managua no longer exist. However, the surviving communist regimes have also been involved to some extent in drug trafficking. The US State Department accused Vietnam in the past of involvement in the drug trade.131 Hanoi has made moves in the past year to crack down on trafficking, including executions of dealers, and to encourage the isolated tribes in the areas bordering on Laos and China to grow substitute crops. This is largely due to the growing domestic drug abuse problem in Vietnam.132 Laos was alleged in 1987 to have promoted cultivation and export of marijuana and heroin in order to obtain foreign exchange and military officials in Laos were closely involved with the drug trade;133 this seems to have ceased in recent years.

The North Korean regime has been trafficking in narcotics, mainly opium and heroin, since at least 1976 when it defaulted on billions of dollars in international loans in order to obtain scarce foreign currency. Pyongyang purportedly expanded its involvement in trafficking substantially, and undertook domestic poppy cultivation and processing as well, after the late leader, Kim Il Sung, issued an internal directive in 1992. 134 The trafficking abroad, mainly to Russia across the porous mutual border but also to China, Africa and South America, has been carried out for the most part by diplomats and other official personnel and by official trading companies. In the most recent case, two North Koreans working for the Social Security Agency apparently a unit of the security services were arrested in 1994, for attempting to sell heroin to undercover Russian agents. 135

Most compelling of all is the evidence of substantial Cuban involvement in the drug trade. Links between Cuba and Colombian drug barons apparently date back to the 1970s. In November 1981, the Colombian Navy sank a cartel ship while offloading Cuban arms destined for the radical Colombian terrorist movement M-19.136 Four senior Cuban officials, including diplomats in Colombia and the Vice-Admiral of the Cuban Navy, were indicted in the US in November 1982, for conspiring to import Colombian methaqualone and marijuana to the US via Cuba. 137 The Cubans provided safe air and sea passage and protection, by government troops, in return for large cash payments and access to cartel smuggling networks for use in shipping arms back to M-19. 138 More senior Cuban officials, including Fidel Castro's brother Raoul, were implicated in the case. Raoul Castro, along with 14 other officials, was named in a US indictment in 1993, which charged the Cuban government with conspiring with the Medellin cartel to facilitate the transportation and distribution of large quantities of cocaine destined for the US market, especially South Florida. 139 A senior Cuban general, Arnaldo Ochoa Sanchez and three others were tried and executed by the Castro regime in 1989 on drug trafficking charges.

TABLE 1: Drug Use in Selected Producer Countries

There is, however, widespread disbelief among experts on Cuba that such a high-level operation could be directed out of Havana without the knowledge and at least tacit sanction of Castro; US officials have speculated that the executions stemmed from internal political machinations. 140 It appears probable that Cuban involvement in the drug trade did not stem from any grand design, but from recognition and exploitation of an opportunity to obtain hard currency for Havana and for its M-19 comrades, with the traffickers serving as facilitators.

Syria is an interesting case, blending narcocratic elements with instrumentalist policy. Syrian military and government officials, including President Assad's brother Riffat, the Minister of Defence and senior officers of military intelligence,141 facilitate and participate in drug activity in the Beqaa Valley of Lebanon. Cannabis cultivation and hashish production (and later, with the assistance of experts brought in by the Syrians from Turkey, poppy cultivation and heroin manufacture) have boomed in this area since its occupation by Syria in 1976; drug cultivation has increased from 10 percent in 1975 to 90 percent in 1991.142 Lebanon is one of the world centers for the processing of opium into heroin and one of the important links in the global network for narcotics smuggling. Syrian forces effectively control all entry-exit points and drug routes in the country; it is therefore difficult to conceive that they do not actively collude in all aspects of the Lebanese drug trade. Income to the Syrian military from the heroin trade is estimated at 300 million to one billion dollars; funds are also provided for use by terrorist groups headquartered in Syria.143

Syrian officials are also reported to have lucrative ties with the Columbian drug cartels, through which they process and distribute South American cocaine in the Middle East; it is also reported that Syrian-linked experts assisted Colombians in establishing opium cultivation in their country. In return, they are alleged to have supplied the cartels with terrorist training and equipment.144

While all this activity does not appear to represent deliberate state policy, it would be disingenuous to believe that President Assad is not aware of the involvement of his brother and senior officials in his security forces in trafficking. As in the previous cases examined, the benign official attitude is probably due to the substantial financial and intelligence benefits accruing to the regime from the drug trade. However, since late 1991, Syria and the newly rejuvenated Lebanese government have embarked on an eradication program in the Beqaa, primarily as a result of the detente between Syria and the US and Syrian desires to obtain US aid and international loans, 145 as well as it being a reflection of infighting. 146 While the seriousness of the effort has been derided by many observers, including Lebanese Druse leader Walid Jumblatt, it appears that Lebanon has achieved success in dramatically curtailing cultivation of opium and cannabis, but that the processing of imported narcotics (cocaine and heroin) in labs in Lebanon, and inside Syria itself, has continued or even increased, so that the volume of narcotics exported from Lebanon has remained substantially the same. 147

CONCLUSION

As the preceding analysis has demonstrated, drugs have manifold and serious effects on the internal political strength and resilience of source countries in almost all of the areas noted above. In this way, they thus weaken the national security of these states. In addition, narcotics affect some of the more traditional, military-strategic components of national security in these countries. Most especially, they strengthen and sustain internal and external threats; degrade the quality and effectiveness of military forces; create economic dependence, vulnerability and weakness; and harm the external relations of producer states with powerful potential allies.

This article marks an initial step in a broader attempt to analyze the international security significance of non-traditional security issues. 148 Such a broader study will also address the significance of narcotics for consumer states, and attempt to utilize international narcotics as a case study for other non-traditional security issues, placing it in a more theoretical framework. Part of such a framework can be found in recent attempts to relate international criminal activity to interdependence theory. 149

Joshua S. Krasna is a doctoral candidate in the Political Studies Department of Bar-Ilan University in Israel.

Endnotes

1. However, as many strategic thinkers within the "traditional" paradigm (since Clausewitz) rec

ognized, in order adequately to estimate a state's power and strategic position, "moral" aspects

must be considered alongside these "material" components. These are those elements that

contribute to a state's political strength and resilience both internally and externally, without

which material advantages are irrelevant or dysfunctional. Within the "moral" elements are:

structure and cohesiveness of society; regime legitimacy, both internal and external; shared

values and symbols; strength of governmental, societal and cultural institutions; centerperiphery

relations within the state; decision-making structures and processes; domestic law and order;

effectiveness of internal controls on dissent; identification of citizens and elites with the state;

political will; diplomatic skill; moral stature and rectitude; and international image and status.

Return to article

2. See, for example, Maxwell D. Taylor, "The Legitimate Claims of National Security,"

Foreign Affairs, (April 1974), pp. 577-94; and Lester Brown,

Redefining National Security, Worldwatch Paper 14 (Washington, October 1977).

Return to article

3. Two notable exceptions are the US State Department, which established a Bureau of Interna