by Colin Knox

INTRODUCTION

Over the past two years, a peace process has been initiated in Northern Ireland. In December 1993, the British and Irish Governments issued a joint (Downing Street) declaration offering Sinn Fein a place in negotiations on the future of Northern Ireland if the Irish Republican Army (IRA) called a permanent end to its campaign of violence. This "framework of peace," as it was described, included the assertion that the ultimate decision on governing Northern Ireland would be made by the majority of its citizens; the Republic of Ireland would, as part of an overall settlement, seek to revise its constitutional claim to sovereignty over Northern Ireland; and Britain would not block the possible reunification of Ireland if it was backed by a majority in the North. The Downing Street Declaration, set alongside a flurry of secret discussions which included an unpublished peace plan devised by the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and Sinn Fein, acted as the catalyst for the IRA and, in turn, loyalist ceasefires (August and October 1994 respectively) and prompted the Frameworks Document published in February 1995. The latter outlined the preferences of the British and Irish Governments for a future settlement. First, agreement must be secured between parties within Northern Ireland (strand 1); second, a North-South relationship agreed to (strand 2); and finally, an Anglo-Irish (Britain and the Republic of Ireland) agreement reached (strand 3).

Procedural disputes between the British Government and Sinn Fein have stalled the process, and the recent resumption of IRA bombings in London have called its future into doubt. Nevertheless, when it resumes as most observers believe it will the political challenge will be to find a model in which all parties play a legitimate role in the future government of Northern Ireland. Since Direct Rule began in 1972, a series of failed initiatives provide evidence of the immense difficulty facing the government in trying to juggle the demands of restoring devolution to Northern Ireland, giving constitutional guarantees to unionists of their position within the United Kingdom and delivering some sort of power sharing arrangements between Catholics and Protestants within an all-Ireland framework. 1 The lessons of the 1973-74 power sharing executive, the 1975 constitutional convention, 1980 talks-about-talks, 1982 rolling devolution and the Northern Ireland Assembly, 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement, Brooke/Mayhew inter-party talks, the Hume/Adams peace plan, the 1993 Joint Declaration and finally the rejection of the 1995 Frameworks Documents by unionists does not bode well for an easy transition to an acceptable form of governance. Yet this is where the real challenge lies. Without some long-term progress toward a stable political system the men of violence will, as they have in the past, reoccupy the constitutional vacuum. The IRA has not disbanded nor scaled down its operations and has not ceased planning terrorist attacks to be carried out if the ceasefire ends. It is still involved in racketeering, intelligence gathering and punishment attacks.

Since the demise of the ill-fated Northern Ireland Assembly, 2 which was boycotted by the SDLP and Sinn Fein, the only platform shared by all the political parties (including Sinn Fein) has been local government. From 1988 onwards, open reference was being made to "responsibility sharing" on councils, a term attributed to Ken Maginnis (MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone), in deference to unionist sensitivities over "power sharing." These sensitivities stemmed from the collapse of the short-lived power sharing executive in 1974, brought down by the Protestant Ulster Workers' Council general strike. At present almost half of the 26 local councils share responsibility, including some with an infamous reputation for sectarian practices. The aims of this article are threefold. First, drawing on research from "hung" councils in Great Britain, we assess the extent to which responsibility sharing in Northern Ireland can be seen as a stable form of government. Second, we chart the experiences and reactions of the main political parties to responsibility sharing in councils. Finally, we explore whether there are any lessons to be learned from the local government experience which would prove helpful in the formation of some power sharing mechanism at the national level.

BACKGROUND

It is perhaps ironic that local government in Northern Ireland has now become the focus of research in power sharing, since its creation in the present format owed much to its abuse of power through gerrymandering, the allocation of public housing and employment discrimination. It is even more ironic that the forum against which the civil rights movement in 1968 directed most of their criticisms and eventually led to the start of "the troubles," is now offered as a model from which lessons can be learned. 3

The existing local government system in Northern Ireland was established following the Local Government (NI) Act (1972). Under this Act 26 local government districts have three basic roles an executive role, a representative role and a consultative role. Their executive role involves the provision of a limited range of services, such as environmental health, cleansing, recreation and latterly economic development. Services, such as housing, education, roads and personal social services, are the responsibility of either government departments, public agencies or area boards. The councils' representative role involves nominating local councillors to sit as members of the various statutory boards. They are consulted by government department officials on the operation of regional services in their area. Their relatively minor role is illustrated by a current estimated net expenditure budget of £192m from a total public expenditure purse of £8 billion. 4 Yet local authorities are important, apart from the executive functions they undertake.

Firstly, as the only democratically elected forum in Northern Ireland since the demise of the Northern Ireland Assembly in 1986, they are of symbolic significance. Secondly, in the absence of any devolved government, councillors are the most accessible source for constituents with concerns about education, health, housing and other mainstream services, over which local government has no direct control. Thirdly, councils employ about 9,000 people in an economy which is noted for its high level of unemployment (14.2 percent). 5

Given the lack of any other constitutional platform, local councillors indulge in political debate and occasional skirmishes which have little to do with their executive functions. Acrimony heightened in 1985 when Sinn Fein councillors were elected to local authorities and the situation deteriorated further following the Anglo-Irish Agreement in November of the same year. Unionist-controlled councils became the vehicle for protests against the Agreement which included suspending council business and, in some cases, refusing to strike a district rate. After a sustained campaign of opposition, unionist councils drifted back to normal business due, inter alia, to concerns that their refusal to meet with government ministers had the potential to delay social and economic progress in their areas.

The local government elections of 1989 marked a turning point in council chambers with a degree of moderation not unrelated to the decline in representation from the political extremes. Dungannon District Council is credited with leading the way through an experiment in responsibility sharing. In May 1988, the council established a special committee which passed a resolution recognizing "responsibility sharing as an important step which might help us to develop trust in the community." The motion was initiated by the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), SDLP, and Independent Nationalists. It was agreed that the position of the chair would be rotated, on a six monthly basis, between council members "who deplore violence and seek to pursue political progress by political means." This effectively excluded Sinn Fein from responsibility sharing and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) refused to partake. While unionists and nationalists were equal in terms of council seats (11-11), in practice, unionists controlled the local authority through the casting vote of the chair. The rotation of chairmanship, in effect, transferred power between the two respective blocs. Considering the fury of unionists at wider political developments in the province, Dungannon's decision to rotate the chair has to be viewed as a major step forward in relations at the local level between unionists and nationalists. The Enniskillen bombing of November 1987 appears to have had a profound impact upon local politicians in Dungannon. Beirne, for example, noted:

Many councillors . . . felt the need to bring an end to sterile adversarial politics in a common commitment to economic and general well-being of the area, and they found in their opposition to political violence more in common than they had previously recognised. 6

Other councils followed suit in the wake of the 1989 local government elections. Eleven local authorities appointed mayors/chairmen and deputies from both political traditions. In 1989, the central government also launched a new community relations initiative within local councils whereby 75 percent grant-aid was made available to councils which agreed on a cross -party basis to participate in schemes (sports, arts and cultural, educational) aimed at bringing the two communities together. A spirit of co-operation emerged in some councils galvanized by their unanimous opposition to the imposition of compulsory competitive tendering. The power sharing trend continued following the 1993 local government elections with 12 councils now participating and an upbeat mood on prospects for its longevity. As one observer commented after the elections:

There may be some cause for hope in Ulster's new councils. The UUP, Alliance and the SDLP have expressed varying degrees of enthusiasm for 'partnership,' code word for sharing the main positions of authority, and the British Government has hinted that such arrangements may be rewarded with increased powers to local government. There are several local councils where a combination of these three parties can form the critical mass necessary to take control and to blur the orange/green divide. A growth in power sharing would do a great deal to change the mood music of Ulster politics and to build the trust between parties which is the necessary precursor to a larger political accommodation. 7

There have been calls recently both for greater devolution of power to local government and a new form of regional government. In the former case, the argument is that a gradual return of local government functions could be conditional on councils adopting power sharing. 8 In the latter, Sir Kenneth Bloomfield, former head of the Northern Ireland civil service, suggested a review in the form of Macrory II (Patrick Macrory provided the blueprint for the first reorganization). 9 Both alternatives envisage a greater role for local government but acknowledge that effective safeguards must exist to guard against abuses of power and allay the fears of nationalists, eloquently expressed by Alban Maginness (SDLP councillor, Belfast City Council): "Giving some councils restored powers would be like inviting Erich Honeker back to implement the reform programme in East Germany. " 10

Archbishop Eames, Church of Ireland Primate, on the other hand, in his submission to the Opsahl Commission (a forum established in February 1993 to elicit community views on the way ahead) argued for more power to be given to local councils where there was evidence of a sharing of responsibility. This, in his view, would be part of a more systematic progression which entailed "slow, steady progress in building up inter -community confidence and trust." 11

THE "HUNG" COUNCIL FRAMEWORK

The STV proportional representation system of voting operates at the local council level in Northern Ireland and was introduced in 1973 as a reaction to unionist hegemony from 1920, and a recognition of a multi-party system which could be more adequately represented, nationalist minorities in particular. The system clearly had an impact on the composition of local authorities and few majority councils exist where one political party holds the overall majority of seats. Following the 1993 elections (see Appendix 1), for example, only 5 of the 26 councils were majority councils. 12 Technically, therefore, the remaining 21 councils could be described as "hung" councils, where "no single party holds a majority of council seats but in which the majority of councillors belong to political parties." 13 A body of research has now emerged on the experiences of hung councils in Great Britain, most notably on their politics and management, organizational behavior 14 and the dynamics of coalitions. 15 This is hardly surprising since about 30 percent of councils in Great Britain are now hung. 16

Some debate exists about the usefulness of theoretical frameworks in examining hung councils, in particular about the contribution of coalition theory to an understanding of these authorities. Leach and Stewart see the coalition framework as inappropriate for local government because the approach is selective and pays too little attention to "the study of the whole organizational and political behaviour" in hung councils. 17 Temple also argues that a multi-dimensional coalition approach, pioneered by Pridham, "may be optimistic given the sheer range of relevant contextual variables cited" as being important in coalition formation. 18 He makes a similar, but qualified, criticism of a framework devised by Leach and Stewart to explain the behavioral outcomes in hung councils. The qualification is that it "provides future case studies . . . with a useful paradigm" in the study of hung councils. We propose firstly to describe and then utilize the Leach and Stewart framework as a means of examining the stability of hung councils in Northern Ireland and from that, draw some lessons on the future of power sharing at the macro level. Aside from the theoretical discussions about the appropriateness of conceptual frameworks there is a general consensus about the merits of hung councils, best described by Temple:

Hung councils work, and provide some measure of proof that British politicians with contrasting philosophies can work together to resolve difficult political issues. 19

The implications of "working together" in Northern Ireland are even more significant.

Leach and Stewart 20 classify hung councils into four broad categories. 21 First is the formal coalition where two or more parties agree to form a joint administration and to share out chairs and vice chairs on the basis of some form of explicit working arrangement. They may also agree on shared policies but this is not seen as a necessity. This type of hung council is the least popular category, totalling some 7.5 percent in the latest survey. 22

Second is power sharing, where two or more parties agree to share chairs, without any commitment to shared policy objectives or a program. The difference between power sharing councils and coalitions is that the politicians involved in the former wish to be seen as politically distinct. This is the most popular form of hung council with some 37.5 percent falling into this category. A total of 45 percent of hung councils have, therefore, some form of coalition government. 23

Third is the minority administration, another popular choice in which one party is allowed to form an administration with the explicit or implicit support of the other party or parties. Support can vary from a coalition in policy terms but without sharing chairs and vice-chairs, to an initial agreement enabling one party to form an administration, but with no commitment to any regular endorsement. This ranked as the second most popular form of hung council at 33.8 percent. 24

The final category is no administration, a system where temporary chairs rotate among different parties with no expectation of office duration. Chairs may be rotated, ad hoc, meeting-by-meeting or on some rota basis. This type of hung council ranked third most popular with 21.2 percent. 25

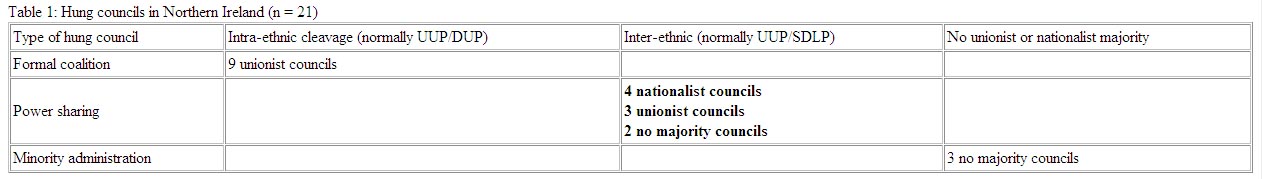

Such a formulation, however, requires adaptation for hung councils in Northern Ireland. Although 21 councils can be described as hung, there are obvious political coalitions that form, based on either the unionist or nationalist cleavages. Those hung councils where there is a combined UUP -DUP majority, for example, are described as unionist controlled councils and those with a combined SDLP-Sinn Fein majority as nationalist controlled councils. Where unionists or nationalists do not form the largest single grouping these are described as no-majority councils, perhaps a strange use of the term since, by definition, all hung councils have no majority. Hence the option for a political party such as the UUP, with the largest number of seats (but not a majority), is to form an explicit or implicit agreement with the DUP (intra-unionist cleavage) or to power share with nationalists, usually the SDLP (mixed cleavage). Conversely, the SDLP as the largest party may adopt Sinn Fein as partners or power share with unionists, normally the UUP. The 21 hung councils in Northern Ireland can thus be classified as follows:

TABLE 1: Hung councils in Northern Ireland (n = 21)

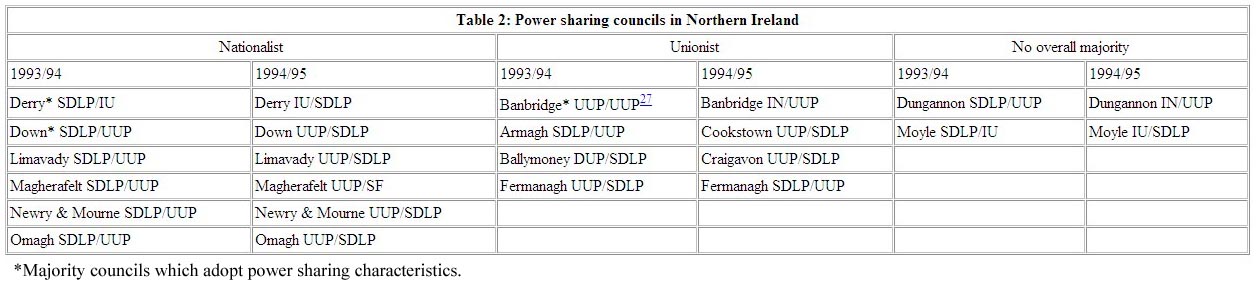

What is of particular interest here, of course, is the power sharing cohort where the largest party numerically eschews the natural political cleavage and shares power with a party representing a different religious tradition. This group contains not only 4 nationalist, 3 unionist and 2 mixed councils (highlighted in Table 1) but a further 2 SDLP and 1 UUP majority councils who have opted to share power or adopt hung council characteristics a total of 12 out of 26 councils. Power sharing would normally entail the rotation of the chair/vice chair positions and committee chairs, proportionate distribution of committee members and sharing of representation on external public bodies. 26 Power sharing councils, including the partners involved, are listed in Table 2 for the period 1993-95.

TABLE 2: Power sharing councils in Northern Ireland

The experiences of how stable mixed cleavage power sharing councils are, clearly has broader implications for a government desperately trying to establish a model of political co-operation in Northern Ireland. Research in Great Britain suggests there are five key conditions necessary for stability in hung councils. 28

Firstly, political history and culture are seen as important in that if the ideological gap between the sharing parties is narrow, chances of a successful partnership are high. Relationships within political parties must also be stable and cohesive to sustain the partnership. Internal divisions will ultimately impact upon inter-party working relationships. Secondly, temporal factors are important. If hung councils are seen as long-lasting the duration of the council term, for example then stability is more likely. Thirdly, if each of the major parties has a significant proportion of seats then stable inter-party relations will result, hence numbers of seats matter. Fourthly, the chief executive is seen as playing a crucial role, acting as honest broker in stable situations, whereas he/she may not be trusted by one or more of the parties in unstable alliances. Finally, the geography of councils is deemed important. Rural or semi-rural councils do not occasion the political controversies of urban councils, making the former grouping more likely to be stable.

POWER SHARING IN NORTHERN IRELAND

Do power sharing councils in Northern Ireland therefore represent a stable form of government and provide an exemplar for co-operation province-wide? In other words, can local government be seen as a microcosm of some future political arrangement at the national level? To address this question we draw on the Leach and Stewart paradigm outlined. Research was undertaken in 15 councils in Northern Ireland, the 12 power sharing councils (listed in Table 2: 1993/94) and 3 non-sharing councils (Lisburn, Cookstown and Craigavon). The research involved three stages: documentary research of council minutes and local newspaper reports on council meetings since the commencement of power sharing; in-depth semi -structured interviews, totalling 50, with leaders of each political group in the 15 councils; and non-participant observation of monthly council meetings in each of the councils over a 6 month period (November 1993-June 1994).

To explore the history and culture of hung councils, we examine the experiences of power sharing partners and the reaction of those parties excluded, based upon data from the three stage research process outlined. 29

THE NATIONALIST RESPONSE

The SDLP

The SDLP have engaged in what they prefer to call "partnership" government since the reorganization of local government in 1973, although the practice was not firmly established. The SDLP in Down Council, for example, have rotated offices with unionists since that time. Policy directives emerged from the SDLP as early as 1980 that sought to promote "partnership" government as a means of lessening community tensions:

Partnership arrangements in these councils (they identify Derry, Down and Newry & Mourne) have led to a dramatic effect on the community in which they are situated. These communities are now well known for their sense of tolerance and understanding of the other person's viewpoint. 30

The SDLP's 1993 local government elections' manifesto ("Progress through Partnership") highlighted the rewards of "partnership" government by specifically comparing the two major urban centres in Northern Ireland, Belfast and Derry. For the SDLP, Derry represents an ideal model of partnership government:

Derry City Council is able to project a positive constructive image to the outside world, so that working with its MP/MEP, Derry is able to attract investment, create jobs, develop tourism and market itself as one of Ireland's premier cities. Belfast City Council on the other hand, has become the by-word for sectarian, obstructionist politics of a kind that most of us, of whatever political persuasion, hoped we had seen the last of twenty years ago. To put it mildly, Belfast's ruling fathers do not succeed or attempt to promote the city as a modern, dynamic and responsible centre for industrial or social development. 31

The SDLP believe that power sharing automatically improves both the day-to-day working and broader political relationships within councils. The sharing of the top office is, in itself, a political gesture which indicates a level of respect for both communities. They do not believe that rotating the chairmanship in councils where they have a majority is any less significant than office sharing in a hung council:

We can't help people voting for us and simply because unionists are in the minority that does not mean that we have to deny ourselves majority rights. We do, however, eschew majority rights that unionists claim elsewhere, often at a cost to ourselves. 32

Responsibility sharing, according to the SDLP, enhances democracy because the majority of people within the wider community support it. In particular, power sharing in a majority council indicates that the largest party are not set on outright domination. The SDLP argue that non-sharing unionist councils are covetous by virtue of their failure to share the top titles. As one party member put it:

Power sharing allows for the embodiment of two traditions. It does not mean that political parties have to relinquish their traditions as it allows for the cherishing of those positions and nobody should feel threatened by it because one of the central tenets of our party's policy is that we don't want ascendancy. 33

Since the SDLP's likely power sharing partner is the UUP, one possible consequence is the effective marginalization of Sinn Fein. The SDLP, however, are only too aware that unionists will not engage in responsibility sharing if it involves active liaison with Sinn Fein. In this sense, it is the unionists who present the SDLP with the choice of co-operation or confrontation rather than the SDLP actively marginalizing Sinn Fein. Although, at the higher political level, the joint contribution of John Hume and Gerry Adams to the peace process is now well-known, this partnership does not appear to have been easily replicated at the local level. Similarly, there is fierce local intra-unionist rivalry, most notably over the DUP reaction to the Joint Declaration and the ceasefire announcements.

Sinn Fein

Across the province Sinn Fein and Independent Nationalists councillors have registered their disapproval at the SDLP's stance on power sharing. Their disapproval does not appear to stem from opposition to responsibility sharing per se but rather to the way in which it excludes them from council business. At a practical level, Sinn Fein councillors have challenged the sincerity of responsibility sharing by nominating candidates for the top positions, or by endorsing Independents. Sinn Fein's 1993 election successes have placed enormous pressure on the SDLP's ability to act freely in at least 4 councils (Magherafelt, Newry & Mourne, Omagh and Dungannon).

Sinn Fein are equivocal about power sharing. Some Sinn Fein members see it as useful, others as a farce. The former are Sinn Fein members who have benefitted from proportionality on council committees (Newry & Mourne and Magherafelt), the latter are those who have been excluded or under-represented on committees (Dungannon and Fermanagh). One consequence of the SDLP/UUP "pact" is that both these parties, to prove their sincerity and commitment to the partnership, indulge in a more obdurate approach to Sinn Fein and the DUP respectively. Sinn Fein members, at the receiving end of attempts to marginalize them, see this as a clever SDLP ploy to outflank them electorally under the guise of mainstream consensus politics with unionists, an idea with mass appeal to voters frustrated and disillusioned by the vitriol synonymous with some council chambers.

THE UNIONIST RESPONSE

UUP

The Ulster Unionists' stance on responsibility sharing is best described by the party leader, James Molyneaux, who endorsed what he called "the sensible policy of cooperation" though he added "it is not power sharing or anything like it." The party are keen to promote the practice of proportionality on committees among constitutional parties. The UUP are wary of playing into the hands of the DUP, given the failure of the power sharing executive in 1974. Responsibility sharing is perceived by unionists as a practice initiated by the SDLP for their own political purposes and as such they are cautious about "making the SDLP look good." On the one hand, unionists see responsibility sharing as no more than the enactment of democracy; yet it becomes undemocratic when it is being foisted upon non -complying parties or when the government attempt to force partnership by promising economic rewards to councils who are willing to share power.

We hold true to democracy and if in the council chamber you are democratic that's no problem. If you operate proportionality on committees that's fine. We have no problem with that either, but let's not start calling it something else like power sharing or responsibility sharing for it is just pure democracy. 34

I wouldn't want to put a particular tag on it . . . there is a limited amount of power in being a councillor and one could talk about all sorts of fancy titles, power sharing, responsibility sharing, but I would say it is just a common sense approach to the every day workings of a sensible council.35

A lively debate is taking place within the UUP on the issue of power sharing. Those on the right of the party opposed it on the basis that it was undemocratic and that the government was surreptitiously setting this agenda. The basis of the undemocratic charge rests upon viewing democracy as the rule of the majority. The party with the largest number of seats should be allowed to form a majority unimpeded by unofficial promises of government economic grant-aid if the councils share power. Yet unionists on the left of the party believed that there was more to be gained from "playing the game" or putting on "the cloak of respectability" if only to obtain these rewards. As one unionist councillor remarked:

I wish other unionists would have the sense to play the game because we are essentially playing the game in Newry and Mourne and to the best of our belief we haven't been caught at it, certainly we haven't been caught by the electorate. We are in a position where we are in the minority on the council, and having taken a conscious decision to represent our people to the best of our ability, then we have to be part of that. In other words, we have to get mud on our boots and mud on our hands and say people are wonderful, but it is simply to achieve the goal that our people are not being left behind and we have been lucky because we haven't been caught . . . some people misunderstand that. 36

Given the differences that exist within the UUP on power sharing at the local level, it is not surprising that Ulster Unionist Headquarters has not adopted a definitive policy. The UUP gave each council a licence to adopt whatever form of administration it deemed appropriate. The result is a pattern of inconsistency throughout the province as UUP councillors tussle over whether or not nationalists should be given chairmanships:

We had talks with the leadership before we endorsed this policy (responsibility sharing) and we were told that because each council is so different in make-up there is no simple policy that can cover all districts. 37

The national party have tried to impose a definitive policy on power sharing but have found that because of certain strong political personalities it has caused splits in the party. The policy now is to do whatever council members feel fit to do. 38

Party leader Jim Molyneaux believes that mandated power sharing is unworkable because it would "render elections null and void, unnecessary and redundant," giving credibility to exponents of undemocratic methods. Voluntary power sharing, however, was another matter:

It would take account of election results and (we could) then see what collection of parties could be brought together in a coalition. It would be something voluntarily done by all parties in consultation.

It wouldn't be power sharing laid down by statute, saying in advance of elections no matter what the results of those elections, that you weren't going to alter a predetermined proportionality. 39

DUP

The DUP are unequivocal in their response to power sharing. Their 1993 election manifesto condemned the "blackmail" attempts by the Northern Ireland Office to force unionists into power sharing agreements with "republicans" on councils. 40 Evidence of the surreptitious hand of government subtly coercing unionists to comply with a power sharing agenda is provided by a DUP councillor in Omagh:

The SDLP/UUP pact in Omagh has been a cosy disaster. Three examples spring to mind. Firstly, the UUP in Omagh actively colluded with the Northern Ireland Office to move the hospital maternity unit away from the area. Ken Maginnis (UUP, MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone) had said that if the maternity service didn't go to Enniskillen then he would lose his seat to Nationalists. The Northern Ireland Office deliberately influenced the decision of where to maintain a maternity service to placate their men, and that is well recorded. Secondly, we had the Housing Executive offices taken away from Omagh and located in Derry as a result of John Hume. Instead of campaigning to keep jobs in Omagh, the SDLP decided not to go against their party leader and, of course, the UUP were dragged into supporting that. Thirdly, an economic strategy to promote jobs in the area has been drawn up with my assistance, but it has not been looked at because it doesn't suit the coalition. My plans involve the active participation of all councillors and our MP (DUP, William McCrea). They cannot abide that, and certainly will not invite McCrea in here. Responsibility sharing between the SDLP and the UUP is a contrived form of bigotry against other parties. 41

DUP Alderman Sammy Wilson said that it was a great pity the UUP were "aiding and abetting the dirty tricks of the Northern Ireland Office by participating in responsibility sharing." 42 The party are implacably opposed to responsibility sharing in any form. They see it as undemocratic and an SDLP-driven public relations initiative that is no more than window dressing. Party members are highly critical of UUP members who "collaborate" in a "cosy relationship" with the SDLP. DUP councillors frequently attempt to expose the fragility of UUP members' commitment to power sharing within councils (Magherafelt and Dungannon are examples) and their reluctance to publicize the idea to the traditional Ulster Unionist electorate. As one DUP councillor put it:

People see it as a joke, it has been dressed up to such a degree that people see it for what it is, a public relations exercise between the SDLP and UUP in which they orchestrate to keep us off committees, which is farcical when you consider that it's supposed to be about sharing. The UUP have never explained why they engage in responsibility sharing nor have they ever fought an election on it. If you look at their propaganda there is no mention of it. It's an embarrassment to them as they go around the doors. I am not sure they want people to know. The SDLP do try to promote it but the UUP certainly do not. If you spoke to them privately they would say they have little confidence in it. Maginnis (MP, Fermanagh and South Tyrone and one time councillor in Dungannon) steam-rolled them into it and now they can't get out. 43

Power sharing councils are not a bastion of political tranquillity and co-operation. Controversy has flared up over issues which create fundamental divisions between the parties. During 1992-93, for example, the SDLP elected DUP Councillor William Hay as mayor of Derry City Council. During his tenure, Hay refused to meet with both the Irish President, Mary Robinson, and the then Taoiseach, Albert Reynolds. The SDLP claimed Hay as mayor had failed in his duties to represent the wishes of the majority in Derry. Divisions also emerged in Newry and Mourne when the council proposed a motion condemning road traffic delays caused by army checkpoints in South Armagh (locally referred to as "bandit country"). Despite a policy of co-operation, unionists could not support such a motion. In the same council area, however, all political parties, except Sinn Fein, condemned the bombing of a local hotel (the Mourne County) by the IRA and the killing of a British soldier. Power sharing has also been used by councils to promote a positive image of their areas. Dungannon Council, for example, claimed that a decision by Carmen Electronics, a Korean company, to set up a factory in their area was influenced by the partnership arrangements of the council. This was endorsed by the then Economy Minister, Robert Atkins, who in announcing the decision of Carmen to locate in Dungannon said:

This is an excellent example of how cohesive local involvement can assist economic development, as councillors and other community representatives from the area, working in partnership with the Industrial Development Board, were an important factor in Carmen's decision to come to Dungannon. 44

In summary, the SDLP view power sharing as both conciliatory and a common sense approach to the smooth implementation of council business. The party do not see the "success" of power sharing as a precursor to transferring more functions to local government, which should only come as part of an overall agreed political settlement at the macro level. The UUP are split between moderates and hardliners. There is a clear perception held by UUP members, particularly in non-sharing councils, that power sharers seem to do better when it comes to securing government funds. Moderates contend that since the UUP are the largest party in all the non-sharing councils, forgoing the possibility of funds for their areas is too risky. This view is informed by the legacy of isolation felt by a number of Ulster Unionist councillors during the Anglo-Irish Agreement protest when they refused to meet government ministers and, as a consequence, debarred themselves from potential funding sources. Hardliners, on the other hand, argue that power sharing is contrary to the principle of majoritarianism in a democracy and the SDLP, because of their United Ireland agenda, should not hold high office in any form of government whose demise they are dedicated to securing. Such a position is particularly prevalent among UUP councillors who are faced with a strong DUP presence (Belfast and Ballymena are examples here). Power sharing with nationalists of whatever hue is anathema to the DUP. Sinn Fein's position is dictated by how well served as a party they are, under specific power sharing arrangements.

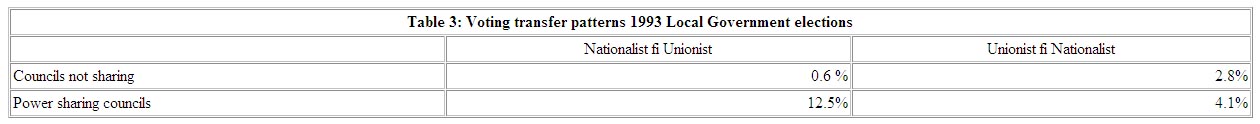

TABLE 3: Voting transfer patterns ‐ 1993 Local Government elections

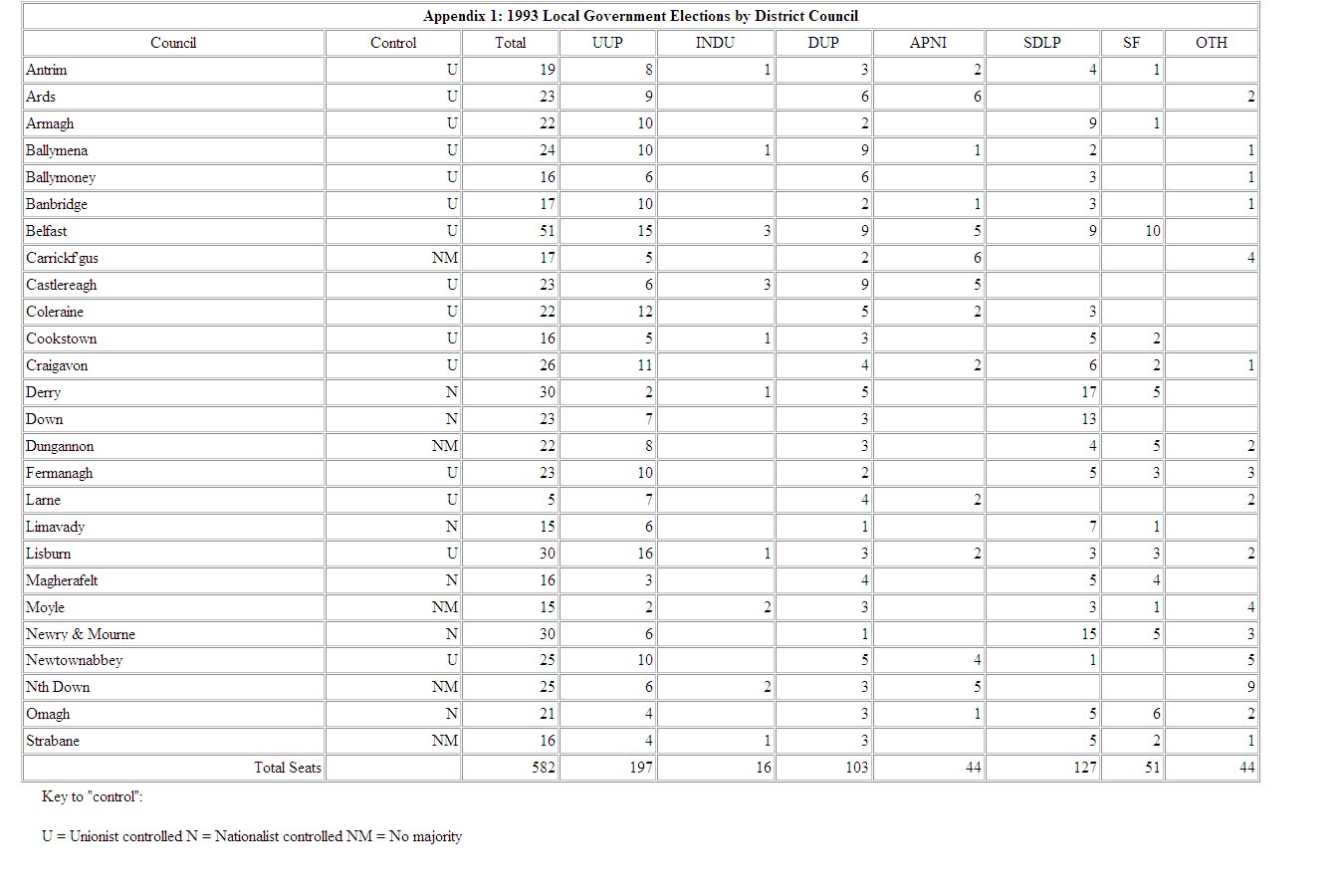

Aside from history and culture Leach and Stewart highlight the political arithmetic, time, the role of the chief executive and the urban/rural dichotomy as influencing stability. In terms of political arithmetric, has responsibility sharing encouraged a degree of political moderation and stability in local government, reflected in electoral trends? In such conditions one might expect to see a decline in support for Sinn Fein and the DUP, and cross-party electoral voting (under the PR voting system used at local elections) between the SDLP and the UUP in short, the politics of moderation. In the former case there has not been a significant decline in support for Sinn Fein or the DUP in local elections since 1989, the responsibility sharing era. In 1993, Sinn Fein's first preference vote increased by 1.3 percent and they gained 8 extra seats (total of 51 councillors). The DUP vote decreased only marginally by 0.5 percent with the loss of 7 seats (total of 103 councillors). These results, however, must be interpreted against an increase in 16 seats available (566 to 582) as a result of boundary changes (see Appendix 1).

An analysis of cross-party voting trends (destination of transfers) in the 1993 local government elections within the 12 power sharing councils and the remaining 14 authorities revealed some interesting results. 45 There was a greater propensity to transfer votes across the political divide (between SDLP and UUP) in power sharing councils, although it was more significant among SDLP voters than UUP voters. There was also a greater propensity to transfer votes within the unionist parties (between DUP and UUP) in power sharing councils, although it was more significant among DUP than UUP voters. Within nationalist parties (Sinn Fein and SDLP), Sinn Fein were more likely to transfer votes to the SDLP in power sharing councils. The reverse, however, was true of SDLP voters in power sharing councils who were less likely to support Sinn Fein candidates. In short, there was a greater proclivity to transfer votes within and between the main political blocs in power sharing councils with one exception, SDLP vote transfers to Sinn Fein. This general assessment is substantiated by Table 3 where higher transfer patterns can be seen in power sharing councils, with the tendency more significant from nationalists to unionists.

As with hung councils in Britain, the number of seats is seen as important in shaping the power sharing model. In those councils where unionists have a slim hold on the largest party title, power sharing has featured prominently on their agenda (e.g. Fermanagh, Armagh and Cookstown). Two councillors from different authorities drew attention to the political arithmetic and its influence of the UUP's propensity to share power:

Unionists chose to share power in Armagh (1993-94) but I'm sure they found it quite difficult. At the same time they realised that the 'writing was on the wall' in relation to the division of seats. In every election for the last 4 terms the SDLP have increased their seats by one. But for the fact of intimidation of candidates in this year's elections (1993), it would have ended up 11-11. From a population point of view Armagh District Council is 50/50 but in relation to seats, we are a seat short of being 50 percent of the council. 46

The unionists should have regard for the fact that in 1993 the majority of votes cast (in Cookstown) were non-unionist votes and it is only by accident that they have a majority on the council. I fancy that among some of the UUP there is a real wish to have better relations and to do things fairly. Now the fact that they didn't share all down the years raises a question mark over whether or not their conversion is complete but I do honestly believe that many of them are sincere about achieving better relations, although there could be an element of keeping an eye to the future when they know the boot is going to be on the other foot. 47

Time is therefore relevant in this context to the extent that within unionist councils, if a change in the largest party is foreseeable, they are more likely to share power in the short-term. The exception to this, however, is the one majority UUP council which shares power (Banbridge). Here the role of the chief executive is seen as pivotal. It is significant that in 3 of the unionist councils (Armagh, Banbridge and Cookstown) most proactive in promoting an image of co-operation the chief executives are relatively new appointees. They are strong advocates of cross party collaboration in the broader interests of the council. Councillors within these authorities provided evidence of chief executives "knocking heads together" and "behind the scenes moves" in the interests of less fractious council chambers.

The rural/urban dichotomy used in the Leach and Stewart framework is slightly inappropriate in the Northern Ireland context given the scale of authorities therein. The two most obvious urban examples, however, are Derry and Belfast, regarded as models of cooperation and conflict respectively. Derry, a SDLP majority council, on the one hand has made serious attempts to rotate the chair with unionists, at one point somewhat disastrously for the party by having a DUP mayor. Belfast, on the other hand, has retained power exclusively among unionists and gained an infamous reputation for vitriolic sectarian debates, fuelled by the combined fervor of DUP and Sinn Fein political personalities. In this sense the two main urban centres reflect the extremes of political co-operation, although Derry City Council is not without its critics as both the DUP and UUP have now refused to accept the chair and power sharing is retained only by the tenuous grip of an independent unionist who has twice been elected mayor. Unionists claim power sharing in Derry is a myth:

Derry City Council has always been portrayed nationally and internationally as a shining example of how Nationalists will treat Unionists and, in reality, it is quite different. It is not a power sharing council. In all committees and in all meetings there is an SDLP majority, so no matter who is chairing the meeting or who is the mayor, the SDLP still control that meeting on every vote, and on every issue they operate a strong party whip. If Unionists were in power we would probably be doing the exact same thing. 48

This is completely at odds with SDLP claims of Derry as the exemplar of power sharing and a blunt admission that unionists would indulge in the same pretensions. What is clear, however, is that the activities of the two largest councils overshadow the efforts of rural councils. In short, the machinations of Belfast City Council are synonymous with everything that is perceived to be local government in Northern Ireland as a whole, and that is normally bad press for rural councils.

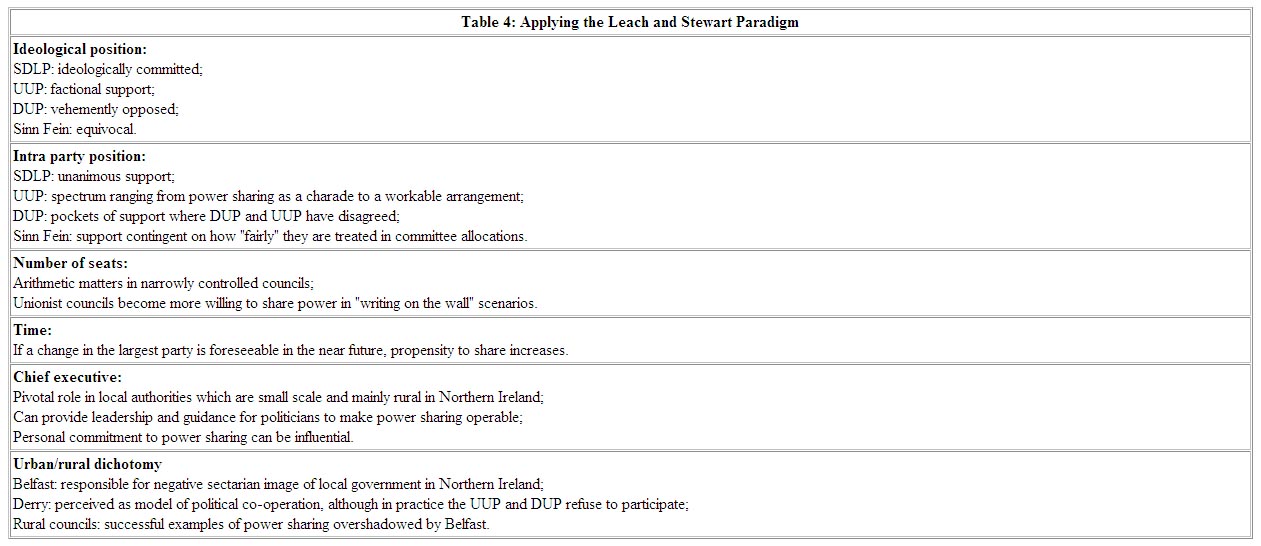

TABLE 4: Applying the Leach and Stewart Paradigm

The application of the Leach and Stewart framework is summarized in Table 4. Three points are noteworthy from the application of the framework in Northern Ireland. First, Leach and Stewart offer no ranking or weighting in the conditions necessary for stability, merely noting that "where all or most of the foregoing conditions are present a settled or stable form of hung authority is likely." 49 What is apparent in applying the paradigm to Northern Ireland is the overwhelming importance of the ideological position to the stability or otherwise of power sharing councils. Those councils with a low DUP presence are much more likely to result in stable relationships between the SDLP and UUP. Second, and in rank order, narrowly held unionist councils are more likely to share power but conditions are unstable and working relationships fraught. Third, the role of the chief executive is particularly important in the small local government units of Northern Ireland where his (there are no female chief executives in Northern Ireland) strength of personal conviction can be instrumental in influencing power sharing arrangements. Clearly, not all the factors promoting stability are evident in Northern Ireland's councils but, on balance, there are encouraging signs of political co-operation which hitherto would have been unheard of.

CONCLUSION: A MODEL FOR THE FUTURE ?

What can be said firstly, about extending power sharing within local government and secondly, its prospects for transfer as a stable form of government at the macro political level? Three observations can be made on the prospects for extending power sharing in councils. First, in the six nationalist controlled councils (Derry, Down, Limavady, Magherafelt, Newry & Mourne and Omagh) power sharing will continue by virtue of the SDLP's commitment to it as a party policy. Second, in the two councils with no overall majority (Dungannon and Moyle), which rotate the chair, responsibility sharing may be no more than a matter of political expediency where parties seek alliances, making a virtue out of necessity. Finally, four unionist controlled councils shared power in 1993-94 (Armagh, Ballymoney, Banbridge and Fermanagh). Following the June 1994 annual general meetings this changed to Banbridge, Cookstown, Craigavon and Fermanagh for the year 1994-95. In the 1993-94 grouping Ballymoney can be explained as an aberration (disagreement between the DUP and UUP), Armagh and Fermanagh as two councils narrowly held by unionists and Banbridge as the only example where there is a clear unionist majority and power sharing.

In the 1994-95 grouping, the disappearance of Ballymoney is no real surprise. The absence of Armagh and the emergence of Cookstown (another marginal unionist council) in the group does, however, validate SDLP claims that where the balance of power is finely tipped in favor of unionists, they are more willing to share power. Banbridge and Craigavon cannot, however, be explained in this way. Both have strong unionist majorities, and in Craigavon's case has been associated with the most blatant examples of sectarianism. 50 Does this, therefore, represent a bold initiative by the UUP in these councils and signal a change in attitudes among UUP members province-wide?

As one UUP councillor (Banbridge) put it:

Things are now blowing towards partnership but it will be a long haul . . . leadership is needed and, to date, no council has given the lead in this yet. We are going to give a substantial lead when we appoint an SDLP chairman and, when we do, I think you will see a lot more councils follow suit. 51

This is an accurate assessment of the prospects with one caveat. Craigavon's power sharing, given its infamous reputation, is a symbolically important council to "follow suit" and is indicative of the much better relationships developing between the UUP and SDLP in local government. The prospect of seeing a "lot more councils" follow suit, however, must be seen as an optimistic assessment. More encouraging indicators of a comprehensive commitment to power sharing in unionist councils would entail (in no particular order):

an SDLP mayor in Craigavon, to maintain the bold momentum toward power sharing in such a bastion of unionism and provide leadership to reluctant sharers;

a consistent UUP/SDLP rotation policy in the finely balanced unionist councils (Armagh, Fermanagh, Cookstown and perhaps Antrim);

some consensus in Belfast City Council, not only because of its political balance but also its dominance of what constitutes local government in Northern Ireland, would herald a major shift in unionists' attitudes to power sharing and act as an example for the waverers elsewhere.

Second, can the model be extended to a Northern Ireland-wide power sharing forum? Based on the experiences of local government the "read -over" is not a simple one. A councillor made the point that it is much easier to share power when those powers are insignificant; the same would not be true in any new form of power sharing assembly:

The council can work well on day-to-day issues where each party's constituents are faced with similar problems. We have no difficulty working with the SDLP or the UUP on roads and housing and a variety of different issues, but these powers do not reside with councils. If councils had real powers it would be harder to work with those parties. At the moment everybody can unite against the Housing Executive, Department of the Environment roads, planners etc the common enemy, but if the council had control over these services the debates would become sectarian. 52

Against that, however, is much evidence of good-will emerging between politicians at the local level, some of whom would see themselves as candidates in any province-wide forum. Moreover, the momentum is strong for political developments on the back of the long-awaited ceasefires. Future relationships will be fraught between the DUP and Sinn Fein, as is currently the case in local government. Indeed it is not certain whether the DUP would agree to participate in such a forum with Sinn Fein members. Yet there is a precedent for this at local government level where both parties recognize unbridgeable political positions but proceed with the council business. The lessons from local government are that whilst unionist controlled power sharing councils show signs of instability, evidence of co -operation is much more apparent than hitherto. This must provide qualified hope for those charged with devising a similar structure at the provincial level. The turn-around in councils from 1985 has been stark. At that time commissioners were called in to run some unionist controlled councils which refused to enact business as a protest against the Anglo-Irish Agreement. Now there is evidence of much good-will and co-operation between the SDLP and UUP. This must provide some encouragement and direction for a power sharing forum at the macro level.

The changing political milieu is creating conditions that are more conducive to accommodation in any new Northern Ireland-wide assembly. Evidence from this research has indicated a propensity for cross-party voting among the electorate even before the ceasefires. A more conciliatory approach is now evident and a huge amount of good-will exists among the population motivated by its desire never to return to violence. This bottom -up ground swell of public opinion is forcing political leaders to acknowledge and come to terms with positions which, previously, would have been untenable in the eyes of the electorate. UUP politicians engaging in debate with Sinn Fein, government ministers consulting political representatives of loyalist and republican paramilitaries, the active inclusion of Dublin's political leaders in talks about the future, are examples of a major shift in the political process which have met with public approval or acquiescence at the least. Alongside these constitutional developments the process has been copper-fastened by European money designed to simultaneously improve social and economic conditions in Northern Ireland. Between 1995-97, 416 million ECU will be provided "to promote the social inclusion of those who are at the margins of social and economic life and to exploit the opportunities and address the needs arising from the peace process." 53

The local government model of power sharing may, therefore, successfully transplant to the provincial level where previous initiatives have failed. Three reasons give grounds for optimism. First, the context for transfer is one of peace, albeit fragile and still fraught with problems on constitutional progress, specifically the decommissioning of arms. Second, there is a bottom-up momentum for accommodation where previously, fixed positions were taken, the electorate were disillusioned and politicians responded with familiar rallying cries. Finally, there is a genuine acceptance by government (British, European and American) that constitutional developments in themselves are insufficient for a long-term settlement in Northern Ireland. A twin track approach whereby constitutional developments are juxtaposed with social and economic investment is now integral to the way forward. The local government experiment in power sharing has been a catalyst in the search for accommodation at the macro level and may well provide the model for a province-wide constitutional forum shared by unionists and nationalists.

Appendix 1: 1993 Local Government Elections by District Council

Colin Knox is Professor of Public Policy in the School of Public Policy, Economics and Law at the University of Ulster.

Endnotes

The author wishes to acknowledge the research assistance of Padraic Quirk in the project upon which this article is based and helpful comments from referees and the journal editor.

1. W. Harvey Cox, "The Northern Ireland Talks," Politics Review,

3, no. 2 (1993), pp. 28-32.

Return to body of article

2. C. O'Leary, S. Elliott and R. Wilford, The Northern Ireland Assembly

1982-86: a constitutional experiment (London: C.Hurst, 1988).

Return to body of article

3. Cameron Commission Report on the Disturbances in Northern Ireland

, Cmd 532 (Belfast: HMSO, 1969).

Return to body of article

4. Department of Finance and Personnel and H.M. Treasury, Northern Ireland

Expenditure Plans and Priorities 1993-94 to 1995-96 (Stormont: DFP,

1993).

Return to body of article

5. Ibid.

Return to body of article

6. M. Beirne, "Out of the Bearpit," Fortnight, May 1993.

Return to body of article

7. L. Clarke, "Extremists hold the line in a Tribal Poll," Sunday

Times, 23 May 1993.

Return to body of article

8. P. John, Local Government in Northern Ireland (York: Joseph Rowntree

Foundation, 1993).

Return to body of article

9. K. Bloomfield, "Closing the Gap," Fortnight, May 1993.

Return to body of article

10. A. Maginness, "SDLP warning on Extra Powers," Belfast Telegraph,

12 January 1990.

Return to body of article

11. R. Eames, "Ruthless Loyalists," Newsletter, 18 January

1993.

Return to body of article

12. The Ulster Unionist Party controlled Banbridge, Coleraine and Lisburn

and the SDLP controlled Derry and Down.

Return to body of article

13. S. Leach and J. Stewart, The Politics of Hung Councils (London:

Macmillan, 1992), p. 8.

Return to body of article

14. Ibid.; S. Leach and J. Stewart, "The Politics and Management of

Hung Authorities," Public Administration, 66, no. 1 (1988),

pp. 35-55; S. Leach and John Stewart, "Change and Continuity in Hung

Councils," Local Government Studies , 19, no. 4 (1993), pp.

499-504; C. Rallings and M. Thrasher, "Parties Divided on Hung Councils,"

Local Government Chronicle, 3 January 1986, pp. 12-13; C. Rallings

and M. Thrasher, "Hung up on Power," Local Government Chronicle,

28 January 1994, pp. 16-17; M. Temple, "Seeking and Sharing Office

in Hung English Local Councils," Public Money and Management,

12, no. 2 ( 1992), pp. 35-39; M. Temple, "Policy Influence in Hung

and Non-Hung Councils," Local Government Policy Making, 20,

no. 1 (1993), pp. 18-25.

Return to body of article

15. M. Temple, "Devon County Council: a case study of a hung council,"

Public Administration, 71, no. 4 (1993), pp. 507-33; M. Laver, C.

Rallings and M. Thrasher, "Coalition Theory and Local Government: coalition

pay-offs in Britain," British Journal of Political Science,

17, no. 4 (1987), pp. 501-09; C. Mellors and B. Pijnenburg, eds., Political

Parties and Coalitions in European Local Government (London: Routledge,

1989).

Return to body of article

16. Rallings and Thrasher, "Hung up on Power," p. 16.

Return to body of article

17. Leach and Stewart, Politics of Hung Councils, p. 210.

Return to body of article

18. Temple, "Devon County Council," p. 526; G. Pridham, Coalitions

in Theory and Practice (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

Return to body of article

19. Temple, "Policy Influence," p. 25.

Return to body of article

20. The popularity rankings in the categories of hung councils have changed

since Leach and Stewart's Politics of Hung Councils was published.

They identified minority administration as most popular (by far) followed

by power sharing and no administration (equally) and finally formal coalitions.

Return to body of article

21. Ibid., pp. 25-29, 107-13.

Return to body of article

22. Rallings and Thrasher, "Hung up on Power," p. 17.

Return to body of article

23. Ibid.

Return to body of article

24. Ibid.

Return to body of article

25. Ibid.

Return to body of article

26. S. Elliott, "Sharing," Fortnight, July/August 1993.

Return to body of article

27. Prior to May 1993, Banbridge Council rotated the vice chair position

with the SDLP. Banbridge Unionists are keen to point out that despite

electing two UUP members to top offices in 1993-94 (as indicated in Table

2), the council is committed to sharing responsibility through

proportionate party strengths on committees and a commitment to share

office during the 4 year council term. This of course happened in 1994-95

Return to body of article

28. Leach and Stewart, Politics of Hung Councils, p. 185.

Return to body of article

29. The Alliance Party's views were not widely canvassed in this research

because of their low representation in power sharing councils.

Return to body of article

30. SDLP submission to the Secretary of State's Conference on Local

Government, 1980.

Return to body of article

31. SDLP 1993 Local Government Elections' Manifesto " Progress through

Partnership."

Return to body of article

32. Interview with Councillor M. Durkan (SDLP), Derry Council.

Return to body of article

33. Interview with Councillor M. Ritchie (SDLP), Down Council.

Return to body of article

34. Interview with Councillor R. Dallas (UUP), Derry Council.

Return to body of article

35. Interview with Councillor J. Speers (UUP), Armagh Council.

Return to body of article

36. Interview with Councillor D. Kennedy (UUP), Newry and Mourne Council.

Return to body of article

37. Interview with Councillor D. Nelson (UUP), Banbridge Council.

Return to body of article

38. Interview with Councillor R. Dallas (UUP), Derry Council.

Return to body of article

39. P. O'Malley, Northern Ireland: A Question of Nuance (Belfast:

Blackstaff Press, 1990).

Return to body of article

40. The DUP do not differentiate between the various strands of

nationalism. The SDLP, by implication, are "republicans."

Return to body of article

41. Interview with Councillor O. Gibson (DUP), Omagh Council.

Return to body of article

42. M. Kelly, "Partnership or Political Hype," Belfast Telegraph, 10 May 1993.

Return to body of article

43. Interview with Councillor M. Morrow (DUP), Dungannon Council.

Return to body of article

44. R. Atkins, "Carmen comes to Dungannon," Mid Ulster Mail, 10 June 1993.

Return to body of article

45. C. Knox and P. Quirk, Responsibility Sharing in Northern Ireland Local

Government (Jordanstown: Centre for Research in Public Policy and

Management, 1994).

Return to body of article

46. Interview with Councillor P. Brannigan (SDLP), Armagh Council.

Return to body of article

47. Interview with Councillor D. Haughey (SDLP), Cookstown Council.

Return to body of article

48. Interview with Councillor R. Dallas (UUP), Derry Council.

Return to body of article

49. Leach and Stewart, Politics of Hung Councils, p. 182.

Return to body of article

50. Craigavon Council was involved in a bitter sectarian wrangle with the

Catholic Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) over the allocation of a

football ground, the outcome of which was a large compensation pay-out by

the council. Several councillors were surcharged and debarred over the

incident.

Return to body of article

51. Interview with Councillor D. Nelson (UUP), Banbridge Council.

Return to body of article

52. Interview with Councillor F. Molloy (Sinn Fein), Dungannon Council.

Return to body of article

53. European Commission Fact Sheet 31.7.1995. Special support programme

for peace and reconciliation in Northern Ireland and the border counties of

Ireland.

Return to body of article