by John M. Cotter

INTRODUCTION

Conflict between ethnic groups has become one of the major security concerns in the post-Cold War era. A recent survey found a total of 35 major internal conflicts occurring as of 1995, many of which involve warring ethnic groups.1 Much of the raw material for such conflicts is the widespread incongruence of national and state boundaries, creating an international system composed mostly of multi-ethnic states. The breakup of the Soviet Union has led to the creation of an additional 15 multi-ethnic states, where newly dominant groups are seeking to consolidate their power and institutionalize governments in a region with 30 communal groups with no ethnically defined administrative unit, accounting for 143 million people, or 35 percent of the region's population.2 Tensions between ethnic groups have erupted into violence in several of these newly independent states, including Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova and Tajikistan.

Although the existence of many "nations without states" raises the potential for violence between ethnic groups, numerous other factors have been used to account for the somewhat wide variation in the incidence and intensity of ethnic conflicts. These explanations range from the "ancient hatreds" hypothesis, which asserts that repressed age-old rivalries between ethnic groups are now coming to the surface as authoritarian regimes collapse, to "ethnic outbidding," where the systematic manipulation by belligerent elites to maintain their grip on power pushes rhetoric to the extreme and can eventually lead to violence.3

Several researchers have employed the international relations concept of the "security dilemma" to explain the emergence and escalation of inter-ethnic conflict, including in the post-Soviet region.4 Simply put, a security dilemma arises when one group's efforts to make itself more secure have the effect of making other groups less secure. Tensions can escalate as these "other" groups, seeking to maintain their own safety, respond with measures that undermine the security of the first group. A dangerous action-reaction spiral built upon fear and mistrust can develop, pushing both sides closer and closer to violent conflict. The threat of this spiral is prevalent in the post-Soviet region where ethnic groups, located in recently independent states with underdeveloped institutional structures for minority participation and protection, can be forced to provide for their own security and simultaneously threaten others.

However, previous use of the security dilemma in explaining the escalation of ethnic violence tends to focus too heavily on the structural aspects of the security dilemma, which emphasize weak states, armaments, demographics and geography, while neglecting the "cultural" aspects of security to ethnic groups, such as the preservation of native languages, histories and group identities. Efforts by one group to strengthen its cultural security are almost always offensive or threatening to other groups who respond with their own demands for cultural preservation and eventually for autonomy. Thus, cultural concerns often reinforce the structural aspects of the security dilemma in the escalation to ethnic violence.

This article seeks to specify further and illustrate how the security dilemma can be used to explain the causes of tensions between ethnic groups and the process by which tensions can escalate into violence. The argument develops as follows. The first section briefly outlines the definition of the security dilemma, and then shows how it has been applied to competition and conflict between ethnic groups. The next section further specifies the conditions under which the inter-ethnic security dilemma can be especially intense, raising the likelihood of the outbreak of violence. The final section illustrates the workings of the inter-ethnic security dilemma using the case of the former Soviet republic of Georgia, which has been the site of two relatively separate large-scale secessionist conflicts in the early 1990s, both involving Georgians, one against the Ossetians, and the other against the Abkhazians. Violence began in the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast in north central Georgia in late 1990 after the Georgian Supreme Soviet revoked the region's traditional autonomy within Georgia. The unrest continued until the middle of 1992 when Russian troops broke a Georgian blockade of the South Ossetian capital of Tskhinvali and inserted peacekeeping forces. Abkhazia, in northwestern Georgia, declared its independence from the Republic of Georgia in July of 1992 after years of tension with ethnic Georgians living in the area, and several unsuccessful attempts to join the Russian federation. This declaration sparked a conflict that lasted until September 1993 when Abkhazian forces, with Russian assistance, pushed Georgian forces out of the region and Russian peacekeepers were inserted.

THE SECURITY DILEMMA AND ITS APPLICATION TO ETHNIC CONFLICT

The Concept

The concept of the security dilemma is employed in the neo-realist theory of international relations, which emphasizes the anarchic environment in which states exist.5 In this setting, each state is ultimately responsible for its own protection from other potentially aggressive states, so that it must acquire the means to defend itself by building up its military capability. But in accumulating the means to defend itself, a state can also simultaneously threaten others, who in turn build up their arms and reduce the first state's security.6 The situation is a dilemma because states must provide for their security, but attempts at doing so can actually have the consequence of making them less secure.

The security dilemma can be particularly intense under two conditions. First, when offensive and defensive capabilities are indistinguishable, states accumulating defensive capabilities are unable to communicate their non-aggressive aims. Because most weapons can be used for either offense or defense, other states must respond with a buildup of their own. Second, when weapons technology, military strategy and geography favor the state that strikes first, or when the offense has the advantage, states may be compelled to strike first because if they do not take the initiative then another state may do so in the future.7

An emphasis on the structural features of the security dilemma often can only provide a partial explanation for the escalation of tensions into violence. Leaders, attempting to assess the changing relative power between groups or the offensive dominance of weapons systems, will often find it difficult to come to any firm conclusions, due to uncertainties about the situation created by imperfect information. More importantly, explanations relying mainly on structural variables are incomplete explanations because defensive operations are almost always easier than offensive ones.8 So, faced with uncertain conditions, leaders may adopt a "wait and see" attitude instead of choosing potentially costly offensive operations.

With defense usually more effective than offense, the concept of the security dilemma has been supplemented with perceptual biases that fuel the spiral to conflict. By constantly assuming malign intentions, leaders can discount or ignore neutral behavior, or even dismiss conciliatory measures by states as tricks to mask aggressive intentions. Leaders are unable to appreciate that their defensive measures can threaten others, so when other groups react with their own buildup, it only confirms the original perceptions of threat.9

Applying the Security Dilemma to Ethnic Conflict

The security dilemma can be an effective explanatory concept when applied to ethnic conflict, especially in the post-Soviet region. When an old authoritarian system breaks down, ethnic groups, who had previously looked to central authorities for their protection, suddenly find themselves in an environment that resembles the anarchic nature of international politics. Newly independent states almost always lack effective institutions for minority participation and supporting laws that guarantee their freedom and physical security.10 Consequently, ethnic groups become responsible for their own security, and efforts to protect themselves can often be construed as threatening to other groups in under-institutionalized multi-ethnic states. The literature that uses the security dilemma may generally be divided into two approaches - those that emphasize structural conditions, especially the insecurities created by weak states, and those that consider both structural and cultural variables, such as language, history and identity, that drive the security dilemma between ethnic groups and the spiral to ethnic war.

Barry Posen put forth the original perspective that emphasizes the structural context, which argues that under conditions of imperial collapse the conditions that make the security dilemma so dangerous between states can be present in relations between ethnic groups, specifically, the indistinguishability of offensive and defensive measures, and the superiority of offensive operations.11 In post-Soviet states military capabilities are largely based on infantry ground forces. In this environment, opposing groups must assess the offensive implications of each other's forces, where troop cohesion, created by strong group identity, can be an important signal of force strength. Because strong group cohesion is necessary for group defense and is also a sign of military capability to others, efforts by either side to reinforce group identity can be threatening and lead to escalation of tensions. The collapse of empires can also leave behind fearful diasporas, who can find themselves geographically surrounded by potentially menacing ethnic groups. Under these conditions, quick and decisive offensive operations may be seen as the only way to rescue stranded ethnic kin.

David Lake and Donald Rothchild argue similarly that ethnic conflicts arise when weak states lose the ability to arbitrate relations between groups and provide for their physical security. In this environment, where opponent's intentions are unclear or unknown, a security dilemma can push ethnic groups toward war, as significant incentives for preemptive action exist, based on strategic interactions between groups characterized by information failures and problems of credible commitment.12 Information failures occur when ethnic groups possess private information, but have incentive to withhold or misrepresent this information to others. Without sufficient information, groups are unable to reliably negotiate their differences in the political arena, as discussions are characterized by bluffing and misrepresentation of intentions and preferences. Problems of credible commitment arise when ethnic groups cannot adequately reassure others that they will uphold mutually beneficial political arrangements, which is especially difficult during periods of changing relative power between groups, or when historical experience demonstrates that others are capable of violence. Since the costs of exploitation can be extreme, such as genocidal attacks, groups may choose conflict over compromise.

Thus, information failures and problems of credible commitment can also give ethnic groups incentive for preemptive action in conjunction with other factors that may favor the offense, such as geographic setting, ethnic settlement patterns or the military benefit of surprise. Despite giving a rationalist account of ethnic conflict, Lake and Rothchild address some "non-rational" factors, which can affect ethnic relations, such as political memories, myths and emotions. These non-rational fears may be used by ethnic political entrepreneurs and activists to further polarize relations between groups. Although these in-group dynamics contribute to the escalation in tensions, their existence and influence depend on the presence of the strategic interactions between groups, ultimately created by a weak state.13

The exception to the general neglect of cultural variables in the use of the security dilemma to explain ethnic conflict is by Stuart Kaufman. Kaufman argues that three factors are necessary for ethnic warfare to occur: hostile masses, belligerent elites and inter-ethnic security dilemmas.14 Outbidding elites competing in the political arena stoke the fears of their followers, as extremism develops on both sides. Extreme demands by opposing groups verify fears of group extinction and the necessity of more extreme measures, including the development of "defensive" armed forces. The result is an inter-ethnic security dilemma where efforts by one group to make itself more secure have the effect of making other groups less secure. All three factors are mutually reinforcing in a spiral of escalating tensions and hostility that leads to ethnic war.

The ethnic hostility, cultivated by belligerent elites, that ultimately drives this interactive process results from both ethnically defined rational dissatisfactions and "emotional heat" generated by hatred and fear of extinction. The conditions that create this emotional reaction are negative group stereotypes, threatened ethnic symbols, a threatening demographic situation and a history of ethnic domination. Stereotypes perpetuate hostility toward the stereotyped group. Conflict over the use of ethnic symbols, on flags for instance, connect immediate issues of disagreement with the more fundamental questions of survival. Demographic decline and memories of ethnic domination provide compelling evidence of group insecurity and add plausibility to the threat of extinction.15

The next section builds on this combination approach to the inter-ethnic security dilemma in explaining ethnic conflict. Specifically, the following section first addresses the concept of cultural security, and then shows how culturally-based threats and fears act in conjunction with structurally induced insecurities to heighten tensions between ethnic groups and drive the inter-ethnic security dilemma that eventually results in the onset of violence.

CULTURAL COMPETITION AND CONDITIONS FOR THE INTER-ETHNIC SECURITY DILEMMA

As with states in competition, ethnic groups will often find it difficult to assess the relative balance of power, military strength or the defensibility of borders between groups, even if it is important to them at all. To emphasize the structural aspects of the security dilemma in applying it to ethnic groups discounts the power of nationalism and misses what is often the source of their competition -- cultural security.

Anthony Smith defines nationalism as an "ideological movement for the attainment and maintenance of autonomy, cohesion and individuality for a social group, some of whose members conceive it to be an actual or potential nation." A nation in turn is "any social group with a common and distinctive history and culture, a definite territory, common sentiments of solidarity, a single economy and equal citizenship rights for all members."16 At the core of the definition of nationalism is the notion of the maintenance of distinctiveness. Mere physical survival is not the only concern of ethnonational groups. Nationalists and their followers desire space for the practice of their own cultural heritage. This necessarily leads them to demand the maintenance of what differentiates their group from another, such as guarantees for the use of a native language, access to education on national history, the preservation of historical monuments or the freedom to practice a specific national religion. In short, nationalists want physical and cultural security.17

Demands for cultural preservation by ethnic groups are not by themselves powerful enough to start an inter-ethnic security dilemma, especially if institutional guarantees for freedom are observed and enforced to protect minorities and/or dominant groups living in areas where they are a numerical minority. However, successive demands for cultural preservation in multi-ethnic regions can induce inter-ethnic competition under two reinforcing, and rather frequently occurring, conditions.

First, demands for cultural freedom and practice can lead to competition when these demands are made in conjunction with more extreme and exclusive nationalist rhetoric. Nationalism as an ideology contains both a positive and negative component. It can be the positive assertion of a shared history and culture for an ethnonational group. But at the same time, nationalism makes a negative assertion as to who does not belong, and thus who should be excluded, feared or even hated.18 In the process of one ethnic group seeking to maintain its distinctiveness, it will emphasize what makes its group good, and at the same time, often identify what makes other groups bad, who respond with their own nationalist rhetoric to defend their culture that they perceive as under attack.19 Thus, more extreme versions of nationalism lead ethnic groups to vilify one another, breeding heightened fear and mistrust.

Second, demands for cultural preservation can lead to competition between ethnic groups when these demands are not realized, especially when they are blocked by other groups who are concerned with their own cultural security. Unrealized attempts at securing a group's cultural heritage and practice can tap that which ultimately gives nationalism its power, that is, its affective and emotional component. Although nationalism is usually defined using objective criteria such as a shared language, religion or history, the power of nationalism comes from a subconscious emotional bond that joins people of the same ethnonational group, in short, "the sense of shared blood."20 Because one is typically born into an ethnic group, people tend to regard ethnicity as a form of extended kinship.21 Consequently, blocked attempts at what a group perceives to be necessary for its cultural preservation lead to an overly emotional response, as if one's family is being threatened.

So, as competing ethnic groups trade demands for cultural preservation over time, overrating the virtue of their own group to the degradation of others, and tapping increasing amounts of emotional fear and mistrust, the competition becomes zero-sum in nature. In other words, tensions escalate as cultural competition continues until it reaches the point where ethnic groups have mutually exclusive perceptions of the situation, where measures by one group to ensure its cultural security are perceived by other groups as a threat. When zero-sum cultural competition between ethnic groups in a multi-ethnic region interacts with other structural conditions, the result is a dangerous inter-ethnic security dilemma, where even the slightest dispute confirms emotional fears and acts as a justification for retaliation. The structural conditions for the development of the inter-ethnic security dilemma include: de facto anarchy, demographic fears of extinction, illegitimate borders and the availability of the means to fight.22

It follows that the more closely the environment in which relations between ethnic groups mirrors that of the anarchic environment of international relations, the more likely a security dilemma is to develop. De facto anarchy refers to a situation in which a state lacks the will or institutional capacity to protect ethnic groups within its borders, which is often the case in newly independent states born from multi-ethnic empires. If this is the case, ethnic groups find themselves in a "self-help" environment and will take steps to enhance their security while undermining the security of other groups. An anarchic environment can also provide minority ethnic groups with a window of opportunity to seek full statehood while the organization of the central government is still under-institutionalized or in disarray.

The second structural condition for an inter-ethnic security dilemma is demographic fears, which can be created in several ways. First, ethnic groups can develop fears of extinction when their size declines in absolute terms. Second, the absolute numbers of an ethnic group may be stable or even growing, but fears can develop if their size relative to other groups in the same region is declining, leading to fears of cultural extinction rather than physical extinction. Third, because ethnic groups are concerned with preserving their cultural heritage, declining birthrates are particularly troubling to nationalists because they cast doubt upon the existence of the group in the future. Fourth, fears can develop if an ethnic group is located in an area in which it is surrounded by one or more other groups, leaving it potentially at the mercy of others.23 In any of these situations, but usually in combination with each other, ethnic groups will make more extreme demands to ensure their survival. The potential for violence increases in the case of mutual demographic fears between groups, which leads to successive extreme measures that reduce the security of others, yet are perceived as necessary under the circumstances.

The third structural condition for the security dilemma is illegitimate borders. Borders that do not match with an ethnic group's historical conception of its geographic homeland or leave ethnic kin divided can lead to conflict. Unfortunately, the borders arising from the demise of multiethnic empires, such as the Soviet Union, lack legitimacy because they tend to be residual administrative boundaries previously drawn by central authorities which divide ethnic kin and/or do not match historical boundaries.24

The final condition for the security dilemma is that both sides must have the means to fight, including weapons, a minimal degree of military organization and a territorial base. Unless each side can threaten the other with physical harm, the security dilemma cannot escalate.25

ETHNIC CONFLICTS IN GEORGIA

All of the above conditions for a dangerous inter-ethnic security dilemma were present in Georgia by the early 1990s, where mistrust and cultural competition in an increasingly unstable political environment eventually escalated into conflict between the Georgians and two ethnic minorities - the Ossetians and the Abkhazians - shortly before Georgia's declaration of independence in 1991.

Essentially, Georgian efforts to reassert their national identity and independence from the Soviet Union were perceived as threatening to the ethnic minorities who demanded the preservation of their traditional autonomy. Sensing a threat to their newly found sovereignty, Georgian leaders adopted increasingly belligerent policies toward minorities. The conflicts escalated as each group adopted what it saw as defensive measures aimed at survival, but confirmed the fears of the opposing side. The security dilemma in Georgia was especially intense as these policies aimed at cultural preservation reinforced the structural aspects of mutual demographic fears, the availability of arms and the breakdown of law and order in Georgia shortly following its independence.

Ethnic Groups in Georgia

According to one observer, "the ethnic complexity of the Caucasus makes areas such as the Balkans or Afghanistan look simple in comparison."26 Frequent invasions, migrations and mountainous geography have led to the creation and maintenance of no less than fifty ethnic groups in this region, each closely associated with a distinct language.

Situated in the Caucasus Mountains, Georgia occupies one of the oldest and most strategic locations in the world. Located between the present-day southern tip of Russia to the north, and Turkey and Iran to the south, it has served as a link between the Christian and Muslim worlds. This strategic position has led Georgia to be coveted and overrun by its more powerful neighbors through the centuries, starting with the Persians, then the Romans, the Turks and most recently Russia and the Soviet Union.

The Georgians are native to the Caucasus region with a civilization that extends back in time three thousand years.27 The Georgian language, Kartuli, has its own alphabet and is also unique to the Caucasus region, making it part of the Kartvelian (Southwest Caucasian) language family.28 The Georgians converted to Christianity in the fourth century AD, which has contributed to their feeling of uniqueness as a Christian bastion in a largely Islamic environment, as Georgia shares three borders with Muslim groups -- to the north with the North Caucasus republics of the Russian Federation, to the east with Azerbaijan, and to the south with Turkey.29 The Russian empire began to expand into Georgia in the late eighteenth century and finally annexed the region in 1801.

The Ossetians are descended from the Alans, an ancient Indo-European people, who migrated to the Caucasus region starting in the sixth century AD, and arriving in what is now South Ossetia around the eighteenth century. The Ossetians speak Iron avzag, an Iranian language that is unrelated to Georgian.30 Ethnic Ossetians are divided religiously and geographically across the Caucasus Mountains, with North Ossetia in the Russian Federation populated mostly by Muslim Ossetians, while South Ossetia is predominantly Christian. The Ossetians have occupied an important supply line through the Caucasus known as the Daryal pass.31

The ethnic origin of the Abkhazians has been the subject of debate between groups. Some contend that they are descendants of the ancient western Georgian group called the Colchians. The Abkhazians, however, assert that they are descended from the Circassian peoples of the North Caucasus region, and are thus separate from ethnic Georgians.32 Abkhazians speak Abkhaz, which belongs to the Abazgo-Circassian (Northwest Caucasian) language family. Abkhazia, which was an independent kingdom throughout much of the Middle Ages and predominantly Christian, was absorbed by the Turks starting in the sixteenth century and many converted to Islam. It remained under Turkish control until 1809 when it was received under Russian protection. The Abkhazians revolted in 1821 and were not finally annexed by the Tsar until 1864. Following Russian annexation and several unsuccessful peasant revolts, many Muslim Abkhazians fled to Turkey and elsewhere in the Middle East.33

Preconditions for the Security Dilemma: the Soviet Legacy

Mistrust, tension and hostility between Georgians and other ethnic minorities stretches back to the early part of this century when Georgia was briefly independent from 1918 until the Soviet takeover in 1921. After the Tsar fell from power in 1917, Georgia seized the opportunity and declared its independence on 26 May 1918. The newly independent government was dominated by social democratic Mensheviks who set up a quasi-democratic government even though Georgia was at war with the Turks and Armenians, and also faced internal uprisings in non-Georgian areas, which the Georgians claimed were inspired by Russian Bolshevik insurgents.

The Ossetians were the main source of internal dissent. In 1918, a peasant uprising occurred in South Ossetia that was suppressed by the increasingly brutal Menshevik People's Guard. The following year Georgian authorities in Tbilisi outlawed the Bolshevik-dominated South Ossetian parliamentary body and refused self-determination to the Ossetians. Then, in the summer of 1920, the People's Guard defeated a Soviet-sponsored South Ossetian Revolutionary Committee that revolted against the Tbilisi government, resulting in 5,000 dead. During the final days of the battle, the People's Guard is said to have displayed a "frenzy of chauvinistic zeal" in reprisals against South Ossetian civilians.34 Press reports of these events would resurface around the time of the conflict between the Georgians and Ossetians as evidence of Ossetian affinity for Russia.

Illegitimate Borders. The Soviet Army finally defeated the Menshevik forces in 1921 and quickly moved to divide the former republic into several different districts where ethnic minorities were concentrated, according to the traditional imperial strategy of "divide and rule." Within two years the Soviets had created three autonomous regions in Georgia: Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Adzharia.35 Abkhazia was a full Union republic in 1921, but was demoted ten years later to an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) at the direction of Stalin.36 Adzharia was also an ASSR, while South Ossetia was a lower status Autonomous Oblast (AO).

This strategy of "divide and rule" used by the Soviets had the benefit of making ethnic groups responsive to central authorities in Moscow, but created artificial borders seen as unjust in many local areas, including Georgia.37 At the time these borders were being created the Ossetians comprised 4.2 percent of Georgia's total population and the Abkhazians only 2.1 percent, but between the two autonomous regions they occupied 18 percent of Georgia's territory. Georgians would later complain that no other Union republic would be forced to give up so much territory for minority autonomous regions.38

The relatively recent arrival of the Ossetians and the existence of the North Ossetian autonomous region gives Georgian nationalists reason to argue that the true place for Ossetians is across the border in Russia. As tensions escalated Ossetians were angered at constant references by the Georgian media to the "so-called South Ossetian Autonomous Province," which they refer to as Shida Kartli, or Inner Georgia.39 During the ensuing conflict in 1991, the president and former leader of the Georgian independence movement, Zviad Gamsakhurdia 40, summarized the uncompromising perspective on South Ossetia, in an address discussing current relations with Russia:

Why is the Russian leadership interested in the stabilization of the situation in Shida Kartli? Because it so-called North Ossetia is of direct concern to Russia. I made it clear that there is no such place as North Ossetia: there is only one real Ossetia. In addition, I explained that neither has there ever been a South Ossetia, nor is there such a place today.41Georgian nationalists further asserted that the Abkhazian region and identity was completely manufactured by the Soviets as a method of destabilizing Georgia.

The Soviet takeover would be the beginning of minority concerns for cultural survival, while Moscow was never able to completely stamp out Georgian nationalism. Fears of cultural extinction would fuel minority demands for greater autonomy, demands that would alienate Georgians concerned that they not be dictated to by minorities in their historical homeland.

The 1930s were desperate times for minorities in Georgia, as they were forced to assimilate into Georgian society. So, while "other non-Russians had their alphabets 'Cyrillicized,' the Abkhazians had theirs 'Georgianized' and the native language schools in Abkhazia and South Ossetia were closed."42 Stalin's second Five-Year Plan called for increased tobacco production from Abkhazia, resulting in the inflow of many Russians, Georgians, Armenians and Greeks to the region to work in agricultural production.43

Some minority rights were restored following the death of Stalin, but ethnic Georgians continued to hold a privileged position in the Soviet republic. According to Ronald Suny:

In each union republic the titular nationality used its position to develop its own version of great-power chauvinism, limiting where it was able the expression of its minorities. Georgia became a protected area for Georgians. They received the bulk of the rewards of the society, the leading positions in the state, and the largest subsidies for cultural projects, while Armenians, Abkhazians, Ossetians, Ajarians [Adzharians], Kurds, Jews, and others were at a considerable disadvantage in the competition for the budgetary pie.44Georgian nationalism would first display itself in 1956 following Khrushchev's speech denouncing Stalin's "cult of personality," when Georgians gathered around a monument to Stalin in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi. After several days, the demonstrators were fired upon as they moved through the city, resulting in dozens killed and hundreds wounded. Georgians again took to the streets in 1976 when the government attempted to remove a clause from the constitution that affirmed Georgian as the sole official language of the republic. This time the Georgian government, led by Eduard Shevardnadze, capitulated to the demonstrators and the original clause was retained.45 The maintenance of Georgian national identity against Russification would be the rallying cry of nationalist movements among the Georgian intelligentsia and students for the next two decades.

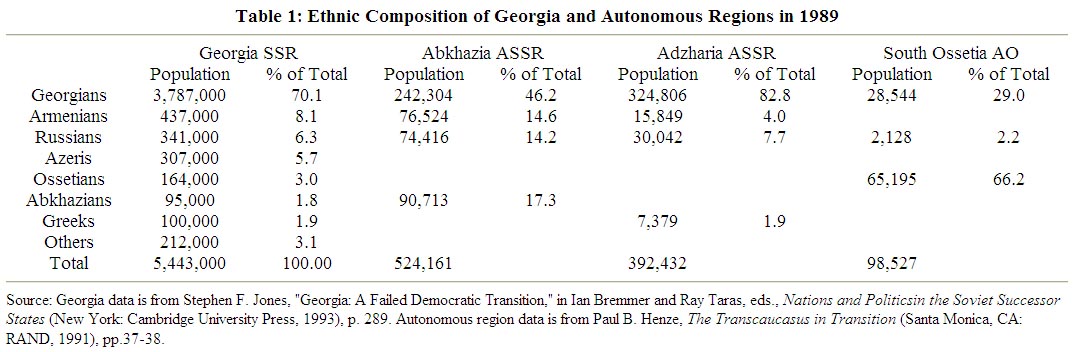

Demographic Fears. The 1989 Soviet census, taken a short time before Georgia's independence, revealed a potentially explosive demographic situation in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR), as seen in Table 1. The Abkhazians were heavily concentrated in their ASSR, but after years of migration to the region, their share of the population in Abkhazia had declined to just 17 percent, while ethnic Georgians represented 46 percent. From the Abkhazian perspective, their demands for cultural revitalization were necessary, even vital to their survival, after years of what was called by Vladislav Ardzinba, Abkhaz historian and secessionist leader, a period "in which the Abkhaz people were undergoing annihilation." He further added that the Georgian nationalist movement had "worked out a special program for combating the Abkhaz people and their cultural institutions."46 The Ossetians were in a somewhat better position in their ASSR where they were 66 percent of the population, but still had to contend with a sizeable Georgian population making up 29 percent of the region's population.

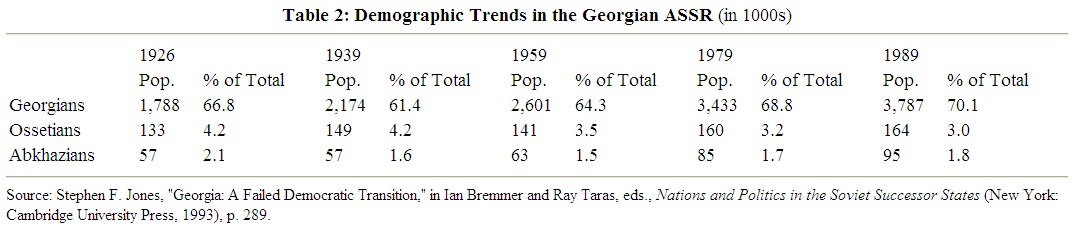

The Georgians saw their own "demographic problem." They complained of declining birthrates among Georgians and increasing numbers of minorities, fearing that they would one day become a minority in their own national homeland.47 Georgian fears seem unfounded as evidenced by Table 2, which shows that the Georgian population had actually increased substantially from 1926 to 1989, while minority percentages had remained relatively stable. Although Georgians made up 70 percent of the total population of the Georgian SSR, there were sizeable populations of minorities at or near 100,000; including Armenians, Russians, Azeris and Greeks, along with the Ossetians and Abkhazians. Gamsakhurdia, in a November 1990 speech complaining of Communist and non-Georgian influence, outlined his plans for these two groups:

They should be chopped up, they should be burned out with a red-hot iron from the Georgian nation, these traitors and venal people. Strength is on our side, the Georgian nation is with us; we will deal with all the traitors, hold all of them to proper account, and drive all the evil enemies and non-Georgians who have taken refuge here out of Georgia!48Means to Fight. When the first small-scale clashes occurred between the opposing groups, evidence indicates that many on both sides had access to arms. A report issued in October 1990 on efforts to confiscate weapons summarized the situation: "Things are difficult in Georgia: Three armed formations are operating openly there, and many people have guns."49 Along with the militias, "unofficial" Georgian forces, and Ossetian and Abkhazian "self-defense" units were operating since the initial hostilities began between the groups in 1989.50 These formations had amassed a considerable amount of firepower, most of it stolen from Soviet military bases, which were often the targets of attacks at the onset of hostilities.51 Following a July disturbance in Abkhazia the Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) disclosed that it had confiscated 1,113 kilograms of explosives and 1,578 firearms.52 According to another report, this one by the Georgian MVD in November 1990, within the prior six months they had "disarmed more than 450 armed groups, and a total of 7,528 firearms have been confiscated."53 Unconstrained armed formations would be of decisive influence on events in Georgia.

TABLE 1: Ethnic Compostion of Georgia and Autonmous Regions in 1989

Table 2: Demographic Trends in the Georgian ASSR (in 1000s)

Escalation of Cultural Competition

Almost half a century after their demotion by Stalin, the Abkhazians campaigned once again to become part of the Russian Federation in 1978. Authorities in Moscow rejected their request to leave Georgia, but did transfer an estimated 750 million dollars for Abkhazian socioeconomic and cultural development, including the creation of the Abkhaz State University in their capital of Sukhumi and more media sources in Abkhazian. The plan also set aside many government posts to be staffed by ethnic Abkhazians. Ethnic Georgians would begin to resent what they saw as preferential treatment given to the Abkhazians by Moscow.

Again in 1988, the Abkhazians sought entrance into the Russian federation when 58 members of the Abkhaz Communist Party wrote a letter to officials in Tbilisi and Moscow claiming that the economic and cultural programs initiated ten years earlier had failed to meet their goals of Abkhaz cultural revitalization. They blamed Georgian hostility for these failures. The Georgians charged back that they were the victims of discrimination in housing, residence permits and government posts. Georgians further charged the Abkhazians with placing restrictions on the use of the Georgian language, the destruction of historical monuments and the distortion of local history.54 In the same year, large demonstrations began to occur in Tbilisi, advocating Georgian independence and protesting discrimination against Georgians by various ethnic minorities.

Nationalist rallies, led by Gamsakhurdia and other dissidents, continued in various Georgian cities into 1989. The demonstrations in Tbilisi grew in size to over 200,000 people when word reached the city in late March that the Abkhazians had again petitioned to secede from Georgia and be granted full Union republic status. This latest attempt was the result of a rally by thousands of Abkhazians who gathered in the village of Lykhny, where a letter was read addressed to officials in Moscow called "On Restoring to Abkhazia the Status of Soviet Socialist Republic Conferred on it in 1921, when V.I. Lenin was Alive." The letter was signed by some of the highest-ranking officials in the Abkhaz Communist Party.55 Georgians feared that Moscow would side with the Abkhazians as a way of weakening the pro-independence movement in Georgia, which by this time had become stronger and more confrontational.56

Tension also grew between Ossetians and Georgians when the leader of the South Ossetian popular front, Ademon Nykhas (Popular Shrine), wrote a letter that appeared in an Abkhaz newspaper saying that Ossetians sympathized with Abkhazian efforts at autonomy and hoped that their success would set a precedent for other regions who also wished to join the Russian republic.57

The turning point in the movement for Georgian independence occurred on 9 April 1989. After a month of large-scale demonstrations, work stoppages and hunger strikes in Tbilisi, a peaceful protest was broken up by Soviet MVD troops using sharpened shovels and tear gas. At least 19 were killed, 16 of whom were women.58 The Soviet action had the opposite of its intended effect, confirming Georgian suspicions about the Soviets and strengthening support for the independence movement among the masses.

The first armed clashes between Georgians and the two minorities occurred in 1989 following the April massacre. On 26 May in Tskhinvali, a group of Georgians celebrating Georgia's 1918 independence from Tsarist Russia were attacked by Ossetians who destroyed their Georgian flags.59 A larger confrontation between Georgians and Abkhazians occurred in July following a Georgian Council of Ministers action to turn the Abkhaz State University in Sukhumi into a branch of the Tbilisi State University, including requiring a new entrance exam for admission to be administered on 15 July. Despite Soviet condemnation and Abkhaz intentions not to let the test take place, the Georgian Council decided to go ahead as planned. On the day of the test, fighting broke out between the two groups in Sukhumi, leading to two weeks of intermittent violence leaving at least 15 dead and 500 wounded.60 Rumors again circulated of Ossetian sympathy for the Abkhazians, as the media reported that Ossetians were headed to the area to aid in the fighting against Georgians.

Just as authorities had regained control of the streets in Sukhumi, violence erupted in Tskhinvali following the August 1989 endorsement by the Georgian Council of Ministers of a draft "state program for the development of the Georgian language." The plan called for the increased use of Georgian in all aspects of public life, especially research and education, a move Ademon Nykhas would call "anti-democratic and discriminatory" because only 14 percent of Ossetians had working knowledge of Georgian.61 The South Ossetian Oblast countered with their own Program for the Development of the Ossetian Language in late September. Many Ossetians felt the initiative - which declared three state languages for the province, Ossetian, Russian and Georgian - did not go far enough. Nationalist strikes and rallies led by Ademon Nykhas increased, calling for autonomy and the replacement of the South Ossetian Party leadership.62 Later in November, a coalition of South Ossetian officials petitioned the Georgian Supreme Soviet to upgrade the Oblast to an autonomous republic, an action they saw as the first step toward reunification with North Ossetia in the Russian Federation. Following the South Ossetian action and rumors of impending attacks on Georgians, armed clashes occurred between the two sides in and around Tskhinvali for two weeks, leaving ten dead.63

Georgian Independence and War with the Ossetians

Georgian pro-independence rallies continued into 1990, but by March a split had revealed itself in the Georgian nationalist movement. Zviad Gamsakhurdia, the leader of the Round Table/Free Georgia coalition, had agreed to compete in the upcoming Georgian Supreme Soviet elections. Gamsakhurdia's nationalist and personal rival was Giorgi Chanturia, who led the more radical coalition comprised of the Georgian National Independence Party and the National Forum. Chanturia advocated that Georgians boycott the upcoming elections in favor of elections for an alternative "National Congress" that would lead Georgia to independence.64 The elections for the Supreme Soviet were postponed by the Communists who sought to capitalize on the nationalist split by developing a cautious pro-independence stand of their own.65

Following an extensive railroad blockade and strike orchestrated by Gamsakhurdia in July, the Georgian Supreme Soviet passed a controversial electoral law for the elections that had been postponed from March to 28 October. The most important measure in the law was a provision stating that political parties "that advocate violence, ethnic hatred, or violation of Georgia's territorial integrity" were barred from participating.66 Thus, the law effectively removed the Abkhazian Popular Front and Ademon Nykhas from the ballots to be used in the election, because they were advocating secession from Georgia. In the following few weeks both Abkhazia and South Ossetia would declare their secession from Georgia, only to have their declarations voided by the Georgian Supreme Soviet as unconstitutional.67 The October election, boycotted by Abkhazians and South Ossetians, was won by Gamsakhurdia's Round Table/Free Georgia coalition with 54 percent of the vote, and the Communist Party coming in second with 30 percent.68

The sound defeat of the Communists meant that the last remnants of institutional representation and protection for minority interests were gone, thus solidifying the de facto anarchy in minority regions emerging since 1989. Georgia was to eventually secede from the Soviet Union regardless of which party was elected, because all parties ran on a pro-independence platform. However, Gamsakhurdia had made it clear in this nationalist rhetoric that he was not interested in the protection of minority rights. Instead, his plans called for increased "Georgianization" of minority regions to maintain the vulnerable republic's territorial integrity.

Gamsakhurdia almost immediately began to consolidate his power by taking over television and radio stations and former Communist newspapers, and creating a Georgian National Guard, commanded by Tengiz Kitovani. The next month, the opposition National Congress, backed by their own paramilitary organization known as Mkhedrioni (or "Horsemen"), began demonstrations against restrictions placed upon them by the new government. The Mkhedrioni militia, led by Jaba Ioseliani, was essentially a warlord known for attacking police stations and Soviet military installations in order to procure weapons.69

The spark that would begin the large-scale conflict between Georgians and Ossetians occurred on 11 December 1990. Just weeks after his electoral victory, Gamsakhurdia and the Georgian Supreme Soviet voted to abolish South Ossetia's autonomous status within Georgia, something that Gamsakhurdia had pledged not to do two months earlier in his first address to the newly elected Supreme Soviet. The action was justified on the grounds that South Ossetia's drive for unification with North Ossetia threatened Georgia's push toward independent statehood.70 South Ossetia responded by declaring itself directly subordinate to the USSR and asked for help from Moscow. The next day, Georgia declared a state of emergency in South Ossetia as armed clashes between the two groups ensued.

Violence in South Ossetia would continue intermittently for the next year and a half as Soviet troops attempted to contain the fighting. Despite North Ossetian condemnation, a Gorbachev presidential decree calling the Georgian action unconstitutional, a short lived ceasefire in January of 1991 and special mediation of the conflict by Boris Yeltsin in March, nothing worked to bring an end to the Georgian blockade and bombardment of Tskhinvali, and fighting elsewhere in the region. Gamsakhurdia repeatedly asserted that the Soviets were inciting the South Ossetian separatist movement as a way of reestablishing control of Georgia.71 Gamsakhurdia vowed in March 1991 that "not a single ambitious would-be politician or careerist will succeed in rallying the population of any part of Georgia against national unity."72

Shevardnadze Returns and War Begins with the Abkhazians

Despite the unrest in South Ossetia, Gamsakhurdia pushed Georgia closer to independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.73 He barred Georgians from taking part in the all-Union referendum, and instead held a Georgian autonomy referendum (on whether to restore its independence declaration of 26 May 1918) on 31 March. In the first of a series of truly impressive electoral returns, 98.93 percent of Georgians supported independence.74 Ten days later and on the second anniversary of the Tbilisi massacre, the Georgian parliament unanimously passed a declaration of independence. On 26 May, Gamsakhurdia was elected president of the new republic with 86.5 percent of the vote.75

Although Gamsakhurdia at least seemed to enjoy a high level of popular support, his constraints on the opposition began to alienate several powerful individuals in Georgia by August of 1991. Tengiz Sigua, whom Gamsakhurdia had made prime minister as a gesture to the opposition, resigned on 18 August on account of the poor government response to the worsening economic situation. Within the next week, Kitovani, and a large portion the National Guard he commanded, renounced Gamsakhurdia and left Tbilisi because Gamsakhurdia did not promptly condemn the Soviet coup and attempted to subordinate the National Guard to the Georgian MVD.76

The situation quickly deteriorated in September as pro- and anti-Gamsakhurdia demonstrations crippled Tbilisi and became increasingly violent, while the opposition backed by the National Guard seized the television station. By December, Gamsakhurdia was under siege in the parliament building, and would eventually be forced to flee the country two days into 1992.77 The Georgian Military Council, controlled by Kitovani, Ioseliani and Sigua, declared a state of emergency and said they would assume control until elections could be held.

Shevardnadze returned to Georgia in March 1992 at the request of Council leaders to assume control of a newly created Georgian State Council.78 Despite heavier fighting between Georgians and Ossetians and some tough talk from the Russians, Shevardnadze displayed a rather conciliatory attitude toward the Ossetian crisis, reaching a ceasefire agreement with the Ossetians on 14 May.79 By mid-July a tri-state peacekeeping force consisting of 500 Russians, 350 Georgians, and a contingent of Ossetian troops was in place.80 Shevardnadze had ended the South Ossetian conflict but still faced an economic breakdown, internal sabotage by Gamsakhurdia supporters and a growing problem of Abkhazian separatism and renegade militia leaders.81*

Abkhazia remained relatively calm compared to South Ossetia during Gamsakhurdia's rise and fall from power, but relations between the two groups turned more hostile as Georgia edged closer to civil war in Tbilisi. For instance, Gamsakhurdia was angered when Abkhazians participated in the all-Union referendum in March 1991, as they voted overwhelmingly (98.4 percent) to sustain the Union and the Abkhazian separatist leader Vladislav Ardzinba interfered with Gamsakhurdia's administrative appointments to the region.82 In spite of the antagonism between the two groups, they reached a compromise regarding representation to the Abkhazian Supreme Soviet. The deputies were to be divided according to ethnic group with the Abkhazians receiving 28, Georgians 26, and "others" 11. The agreement also required a two-thirds majority to pass "important legislation."83

The Abkhaz Supreme Soviet began work in January 1992, and shortly thereafter Georgian members to the body complained of Abkhazian violations of the agreement made the previous spring. By the end of the month, the Abkhaz Supreme Soviet was debating secession from Georgia. In May the Abkhazian MVD chief and ethnic Georgian, Givi Lominadze, triggered demonstrations when he refused to obey an order from the Supreme Soviet to resign his post, complaining of discrimination against Georgians.84

The tension between the two groups quickly escalated to war following another Abkhazian declaration of independence from Georgia made by the Abkhazian Supreme Soviet on 23 July, a move the Georgian State Council would declare illegal.85 Three weeks later Georgian National Guard troops drew fire from Abkhazian MVD troops in Sukhumi as they searched for Georgian officials who had been kidnapped by Gamsakhurdia supporters in western Georgia. Sigua, the acting prime minister, and Ioseliani, now a deputy defense minister, quickly negotiated a ceasefire between the two groups that would break down after only three days. On 18 August, Georgian National Guard troops led by Kitovani, who apparently was acting on his own, stormed the Abkhazian parliament building in an attempt to arrest the Abkhazian separatist leader Ardzinba.86 The Georgian forces burned the building to the ground, but Ardzinba escaped to the city of Gudauta where he led the Abkhazian forces to war with the Georgian State Council.

The intrastate conflict quickly became internationalized. Two days before Kitovani's attack, a Russian airborne division arrived in Abkhazia and drew fire from Georgian armed formations.87 The Abkhazians were supported by troops from the informal North Caucasus organization called the "Confederation of Mountains Peoples." As ceasefire after ceasefire was violated and fighting continued, evidence began to accumulate that reactionary forces in the Russian military were actively supporting the Abkhazian separatists, as the Abkhazian minority making up only 17 percent of the population in 1989 was slowly but surely pushing the Georgian forces from the region, controlling half of Abkhazia by October.88 Shevardnadze was overwhelmingly (95.9 percent) elected parliamentary chairman in October, but still had difficulty keeping control over Kitovani, who was rumored to be plotting a coup.89

Russian forces stepped up their support of the Abkhazian separatists in December when Georgian forces shot down a Russian helicopter evacuating Russian refugees from the area, killing all aboard, most of whom were women and children.90 The fighting continued into 1993 as Abkhazians started an assault on their Georgian-held capital of Sukhumi. Following an initially cautious approach to the conflict and numerous attacks from the Russian right-wing in the press, Yeltsin also became more assertive saying in February that it was time "to grant Russia special powers as the guarantor of peace and stability in the region."91 In May, Shevardnadze was finally able to remove Kitovani and Ioseliani from the Defense Council and start negotiations for a ceasefire agreement, with mediation by the Russians. A ceasefire was finally signed in late July 1993, which was followed shortly by a new offensive by Gamsakhurdia, who had returned to Georgia the previous year vowing to reclaim his rightful position as president of Georgia.

In mid-September the Abkhazians broke the ceasefire and launched their final offensive to retake Sukhumi, aided by the Confederation of Mountains Peoples and Russian troops.92 Eleven days after the assault began the Georgian forces were forced to retreat, only to be intercepted by Gamsakhurdia supporters who seized their weapons. Facing an economic crisis and internal dissension from Gamsakhurdia and other militias, Shevardnadze unilaterally accepted CIS membership and the stationing of Russian troops in Georgia, in exchange for Russian support to defeat the now well-armed Gamsakhurdia forces in western Georgia. With Russian support, the pro-Gamsakhurdia forces were defeated by November, while Gamsakhurdia was reported to have committed suicide.93 A UN-sponsored Memorandum of Understanding was signed by both sides in Geneva on 1 December 1993.

CONCLUSION: ADDING CULTURAL SECURITY TO THE INTER-ETHNIC SECURITY DILEMMA

Overall, the inter-ethnic security dilemma is a good explanation for the escalation of conflicts among ethnic groups in Georgia. As with using the security dilemma to explain competition and conflict among states in the international system, the inter-ethnic security dilemma must include structural conditions, such as illegitimate borders and de facto anarchy, and perceptual biases, which exacerbate the insecurity created by the political context.

Many of the structural conditions for the security dilemma are traceable to the political and cultural legacy left by Georgia's 70 year history as part of the Soviet Union. The arrangements of the Soviet empire did not satisfy any of the groups, and ultimately enhanced fears of cultural decline. Regions set aside for ethnic minorities gave them token autonomy and justification for their future plans of self-determination, but were unable to halt their cultural decline, especially Abkhazian demographic fears of extinction, in a republic of Georgian institutional and cultural hegemony. Georgians viewed the same regions as illegitimate manifestations of Soviet policies aimed at dividing and "Russifying" Georgia with sympathetic minorities. Insecure Georgian hegemony allowed Georgian nationalism to persist and eventually come to the surface in increasingly extreme forms.

All sides in the conflict in Georgia were unable to appreciate that their actions would be perceived as threatening to others, while they consistently assumed malign intentions on the part of the outgroup. Under these circumstances, any defensive action, as one group perceives it, confirms fears among the other groups that their security is threatened. For instance, the Georgians blamed the Ossetians for the revocation of their autonomy because the Ossetians were contemplating unification with North Ossetia in the Russian Federation, forgetting that the Georgian language program was threatening to the Ossetians who had not mastered Georgian.

The third condition for the security dilemma is "zero-sum" cultural competition, where actions by one group to secure their cultural practices and heritage reduces the cultural security of other groups. In the case of the Abkhazians, demands for Abkhaz cultural revitalization were absolutely necessary from their perspective, but threatened the sizable Georgian population living in the area. Further, the Georgians outside of Abkhazia adamantly believed the revitalization of non-Georgian cultures within Georgian borders was totally inappropriate, and eventually threatening, to Georgians who were also seeking the rediscovery of their historical legacy and national identity as the independence movement gained momentum.

The inter-ethnic security dilemma as conceptualized here fits the Abkhazian-Georgian conflict slightly better than the Ossetian-Georgian situation, because cultural competition between the two ethnic groups in Abkhazia has a longer history, starting back near the turn of the century and accelerating in the late 1970s with the first Abkhazian demands for the restoration of their original full Union republic status. In both cases, as Georgia moved closer and closer to independence in the late 1980s and early 1990s, cultural competition took on added significance in terms of security. The extremist rhetoric by Georgian nationalist leaders, especially by Gamsakhurdia who would become Georgia's first post-Soviet era president, showed to the Ossetians and Abkhazians that their cultural security was threatened by Georgian independence from the Soviet Union, hence the Ossetian and Abkhazian votes to maintain the USSR and numerous attempts to join the Russian Federation. Demands by the minorities to maintain their autonomy were perceived as a threat to Georgian territorial integrity. The escalation to open conflict in Georgia occurred because each side developed mutually exclusive perceptions of the situation, within a situation of deteriorating governmental institutions, mutual demographic fears of extinction which created additional extremism, in an extremely well-armed society.

Generally, the inter-ethnic security dilemma specified in this analysis that addresses both structural and culturally based threats and insecurities provides a better explanation of ethnic conflicts than the structural approach alone. Weak states and the security implications that follow from this condition are too prevalent to account for the variation in amount and intensity of ethnic conflicts in general, including in the post-Soviet region. Further, the inter-ethnic security dilemma conceptualized here rightfully equates threats to ethnonational distinctiveness with physical insecurities, as separate peoples fear destruction from military weapons as much as they fear a somewhat slower demise from cultural decline and extinction.

Endnotes

I am grateful to Karen A. Mingst, and, in particular, Stuart J. Kaufman for their comments on previous drafts of this article. This research was supported by funds from the University of Kentucky.

1. Michael E. Brown, The International Dimensions of

Internal Conflict (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996), pp. 4-7. A "major"

internal conflict is defined as a conflict that has resulted in at least

1,000 deaths. For additional statistics on the number of ethnic conflicts,

see Ted Robert Gurr, "Peoples Against States: Ethnopolitical Conflict and

the Changing World System," International Studies Quarterly, 38, no. 3

(September 1994), pp. 347-77.

Return to Article

2. Monty G. Marshall, "States at Risk: Ethnopolitics

in the Multinational States of Eastern Europe," in Ted Robert Gurr, Minorities

at Risk: a Global View of Ethnopolitical Conflicts (Washington, DC: United

States Institute of Peace Press, 1993), p. 75. These communal groups are

designated as "minorities at risk" in Gurr's Minorities At Risk data bank

and archives. Minorities are defined as communal groups whose members share

a distinctive and persistent identity, differentiated by a common culture,

shared historical experience, and a combination of ethnicity, religion

and language. "At Risk" indicates they are subject to differential treatment

by other groups. See Gurr, Minorities at Risk, p. 3. For additional evidence

of the multi-ethnic make-up of states, see Walker Connor, Ethnonationalism

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), p. 96; and Gunnar P.

Nielsson, "States and 'Nation-Groups': a Global Taxonomy," in Edward A.

Tiryakian and Ronald Rogowski, eds., New Nationalisms and the Developed

West (Boston, MA: George Allen & Unwin, 1985), pp. 57-86.

Return to Article

3. For a brief outline of the hypothesized causes of

ethnic conflict, see Brown, The International Dimensions of Internal Conflict,

pp. 12-23. On outbidding specifically, see Alvin Rabushka and Kenneth Shepsle,

Politics in Plural Societies (Columbus, OH: Charles E. Merrill, 1972);

and V. P. Gagnon, "Ethnic Nationalism and International Conflict: The Case

of Serbia," International Security, 19, no. 3 (Winter 1994/95), pp. 130-66.

Return to Article

4. One of the first to apply the security dilemma to

the outbreak of ethnic violence was Barry R. Posen, "The Security Dilemma

and Ethnic Conflict," Survival, 35, no. 1 (Spring 1993), pp. 27-47. Others

which use the security dilemma as part of their explanatory frameworks

include Stuart J. Kaufmann, "The Irresistible Force and the Imperceptible

Object: The Yugoslav Breakup and Western Policy," Security Studies, 4,

no. 2 (Winter 1994/95), pp. 281- 329; and David A. Lake and Donald Rothchild,

"Containing Fear: The Origins and Management of Ethnic Conflict," International

Security, 21, no. 2 (Fall 1996), pp. 41-75. For an application of the security

dilemma to conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, see Susan L. Woodward, Balkan

Tragedy: Chaos and Dissolution After the Cold War (Washington, DC: Brookings

Institution, 1995).

Return to Article

5. The concept of the "security dilemma" is derived

from John Herz, "Idealist Internationalism and the Security Dilemma," World

Politics, 20, no. 2 (January 1950), pp. 157-80. For the security dilemma

spiral model, see Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International

Relations (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), chap. 3. On

neo-realist theory, see Kenneth Waltz, Theory of International Politics,

(Reading, PA: Addison-Wesley, 1979).

Return to Article

6. Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International

Politics, pp. 63-64.

Return to Article

7. Ibid., p. 67

Return to Article

8. Jack L. Snyder, "Perceptions of the Security Dilemma

in 1914," in Robert Jervis, Richard Ned Lebow, and Janice Gross Stein,

eds., Psychology and Deterrence (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University

Press, 1985), p. 157.

Return to Article

9. Ibid., p. 164; Jervis, Perception and Misperception

in International Politics, p. 68.

Return to Article

10. Jack Snyder, "Nationalism and the Crisis of the

Post-Soviet State," Survival, 35, no. 1 (Spring 1993), pp. 5-26.

Return to Article

11. Posen, "The Security Dilemma and Ethnic Conflict,"

pp. 27-47.

Return to Article

12. Lake and Rothchild, "Containing Fear," pp. 41-56.

Return to Article

13. Ibid., p. 55.

Return to Article

14. Stuart J. Kaufmann, "Spiraling to Ethnic War: Elites,

Masses, and Moscow in Moldova's Civil War," International Security, 21,

no. 2 (Fall 1996), pp. 108-38.

Return to Article

15. Ibid., pp.112-13.

Return to Article

16. Anthony D. S. Smith, Nationalism in the Twentieth

Century (New York: New York University Press, 1979), p. 87. For additional

conceptualizations of nationalism, see Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities:

Reflections of the Origins and Spread of Nationalism, rev. ed., (London:

Verso, 1991); E. J. Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism Since 1780 (New York:

Cambridge University Press, 1990); Ernst Haas, "What Is Nationalism and

Why Should We Study It?" International Organization, 40, no. 3 (Summer

1986), pp. 707-44; and Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism (Ithaca,

NY: Cornell University Press, 1983).

Return to Article

17. This conceptualization of cultural security is

similar to that of Barry Buzan, People, States and Fear: An Agenda for

International Security Studies in the Post-Cold War Era, 2nd ed. (Boulder,

CO: Lynne Reinner, 1991). Buzan refers to this sector of security as "societal

security," while I have chosen to call it "cultural security" to emphasize

its distinctiveness from state- or military-centered conceptualizations

of security. For additional discussion of societal security, see Ole Wœver,

Barry Buzan, Morten Kelstrup, and Pierre Lemaitre, Identity, Migration

and the New Security Agenda in Europe (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993);

and Morten Kelstrup, "Societal Aspects of European Security," in Birthe

Hansen, ed., European Security 2000 (Copenhagen: Copenhagen Political Studies

Press, 1995), pp.172- 99.

Return to Article

18. Woodward, Balkan Tragedy, p. 223.

Return to Article

19. Lake and Rothchild, "Containing Fear," pp. 55-56.

Return to Article

20. Walker Connor, "Beyond Reason: the Nature of the

Ethnonational Bond," Ethnic and Racial Studies, 16, no. 3 (July 1993),

pp. 373-89.

Return to Article

21. On the relationship between ethnicity, kinship

and family, see Donald Horowitz, Ethnic Groups in Conflict (Berkeley, CA:

University of California Press, 1985), chap. 2.

Return to Article

22. This list of variables is borrowed from Kaufmann,

"Spiralling to Ethnic War," p. 113.

Return to Article

23. Stephen Van Evera, "Hypotheses on Nationalism and

War," International Security, 18, no. 4 (Spring 1994), p. 19. According

to Van Evera, when one group is left at the mercy of another group and

the possibility of rescue by force exists (either by secession or by intervention

from willing and capable members of the same ethnic group), the likelihood

of violence increases. Surrounded ethnic kin also make quick and decisive

offensive military operations more attractive to potential rescuers, thus

intensifying the security dilemma. See Posen, "The Security Dilemma and

Ethnic Conflict," p. 32.

Return to Article

24. Van Evera, "Hypotheses on Nationalism and War,"

pp. 21-22.

Return to Article

25. Kaufmann, "Spiralling to Ethnic War," p. 114.

Return to Article

26. Paul B. Henze, Conflict in the Caucasus (Santa

Monica, CA: RAND, 1993), p. 5.

Return to Article

27. On ancient and medieval Georgia, see David Marshall

Lang, The Georgians (New York: Praeger, 1966); and Ronald Grigor Suny,

The Making of the Georgian Nation (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University

Press, 1994) especially Part One "The Rise and Fall of the Georgian Monarchies,"

pp. 3-62.

Return to Article

28. Language origins are from Bernard Geiger, Tibor

Halasi-Kun, Aert H. Kuipers, and Karl H. Menges, Peoples and Languages

of the Caucasus: a Synopsis (The Hague: Mouton and Co., 1959).

Return to Article

29. Shireen T. Hunter, The Transcaucasus in Transition:

Nation Building and Conflict (Washington, DC: The Center for Strategic

and International Studies, 1994), p. 11. See also Stephen Jones and J.

W. Robert Parsons, "Georgia and the Georgians," in Graham Smith, ed., The

Nationalities Question in the Post-Soviet States, 2nd ed. (New York: Longman,

1996), pp. 291-92.

Return to Article

30. David Marshall Lang, A Modern History of Soviet

Georgia (New York: Grove, 1962), p. 4.

Return to Article

31. Ibid., p. 44.

Return to Article

32. Hunter, The Transcaucasus in Transition, pp. 124-25.

Return to Article

33. Lang, A Modern History of Soviet Georgia, pp. 91,

103; see also Paul B. Henze, The Transcaucasus in Transition (Santa Monica,

CA: RAND, 1991) p. 13.

Return to Article

34. Details of Ossetian dissent during Georgia's brief

period of independence are from Lang, A Modern History of Soviet Georgia,

pp. 228-29. For additional coverage of Georgia's brief period of independence,

see Firuz Kazemzadeh, The Struggle for Transcaucasia 1917-1921 (New York:

Philosophical Library, 1951).

Return to Article

35. It was at this point in time that Christian South

Ossetia was separated from Muslim North Ossetia, which remained in the

Russian Federation. Adzharia is a region in southwest Georgia that is populated

by ethnic Georgians, but who practice Islam dating back to the sixteenth

century when the area was under Turkish control.

Return to Article

36. Catherine Dale, "Turmoil in Abkhazia: Russian Responses,"

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (hereafter cited as RFE/RL) Research Report,

2, no. 34 (27 August 1993), p. 49.

Return to Article

37. On the Soviet creation of artificial borders, see

Matthew Evangelista, "Historical Legacies and the Politics of Intervention

in the Former Soviet Union," in Michael E. Brown, ed., The International

Dimensions of Internal Conflict (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996), pp.

110-14.

Return to Article

38. Suzanne Goldenberg, Pride of Small Nations: The

Caucasus and Post-Soviet Disorder (London: Zed Books, 1994), p. 101.

Return to Article

39. Izvestia, 29 October 1989, translated in US Foreign

Broadcast Information Service: Soviet Union (hereafter cited as FBIS),

30 October 1989, p. 78

Return to Article

40. Zviad Gamsakhurdia, the son of famous Georgian

writer Konstantine Gamsakhurdia, was a long time dissident and human right

activist in Georgia whose activities aimed at stirring up Georgian national

pride against the Soviets stretched back to the early 1970s.

Return to Article

41. From a Gamsakhurdia televised speech, 25 March

1991, translated in FBIS, 19 April 1991, pp. 58-59.

Return to Article

42. Stephen F. Jones, "Georgia: A Failed Democratic

Transition," in Ian Bremmer and Ray Taras, eds., Nations and Politics in

the Soviet Successor States (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993),

p. 291.

Return to Article

43. Lang, A History of Modern Soviet Georgia, p. 265.

Return to Article

44. Suny, the Making of the Georgian Nation, p. 290.

Return to Article

45. Ibid., pp. 302-10.

Return to Article

46. Remarks by Ardzinba are from a speech given at

the 1989 Congress of People's Deputies reported verbatim in Izvestia, 4

June 1989, translated in Current Digest of the Soviet Press (hereafter

cited as CDSP), 41, no. 28 (9 August 1989), pp. 14-15.

Return to Article

47. For example, a session of the Georgian council

of Ministers government demographic commission concluded "the initial principle

of the demographic policy should be the all-around encouragement of the

[Georgian] birth rate, the increasing of the need to have children, and

concern for their education and health." Quoted from Zarya Vostoka (Tbilisi),

3 December 1988, translated in FBIS, 16 December 1988, p. 67. Shortly following

independence, the new government would pass legislation that lowered the

marriage age for girls to 15, as its first strategy to increase the Georgian

birthrate. See Goldenberg, The Pride of Small Nations, p. 88.

Return to Article

48. Izvestia, 10 November 1990, translated in CDSP,

42, no. 45 (12 December 1990), p. 9.

Return to Article

49. Ibid., 18 October 1990, translated in CDSP, 42,

no. 42 (21 November 1990), pp. 25-26.

Return to Article

50. Moskovskiye novosti, 3 December 1989, translated

in CDSP, 41, no. 48 (27 December 1989), p. 21.

Return to Article

51. Elizabeth Fuller, "Paramilitary Forces Dominate

Fighting in Transcaucasus," RFE/RL Research Report, 2, no. 25 (18 June

1993), p. 81. Georgia was also an industrial manufacturer of light arms

and aircraft.

Return to Article

52. Pravda, 3 August 1989, translated in CDSP, 40,

no. 34 (20 September 1989), p. 35.

Return to Article

53. Izvestia, 10 November 1990, translated in CDSP,

42, no. 45 (12 December 1990), p. 9. One Georgian official remarked simply,

"The population has stockpiled an enormous quantity of weapons."

Return to Article

54. Elizabeth Fuller, "Abkhaz-Georgian Relations Strained,"

Report on the USSR, 1, no. 10 (10 March 1989), p. 26.

Return to Article

55. Details of the Lyknhy meeting are from Izvestia,

1 April 1989, translated in FBIS, 3 April 1989, pp. 71-72.

Return to Article

56. Elizabeth Fuller, "New Abkhaz Campaign for Secession

from Georgia," Report on the USSR, 1, no. 14 (7 April 1989), p. 28.

Return to Article

57. Elizabeth Fuller, "The South Ossetian Campaign

for Unification," Report on the USSR, 1, no. 49 (8 December 1989), pp.

17-18.

Return to Article

58. For differing versions of the events of the Tbilisi

massacre, see Elizabeth Fuller and Goulnara Ouratadze, "Georgian Leadership

Changes in the Aftermath of Demonstrators' Deaths," Report on the USSR,

1, no. 16 (21 April 1989), p. 30. Dissidents claimed that peaceful and

unarmed demonstrators were attacked without warning or provocation resulting

in 33 dead. Official Soviet and Georgian reports said that troops were

attacked with sticks and knives when they tried to move the crowd. Sixteen

were reportedly trampled in the ensuing confusion, with 191 injured.

Return to Article

59. Fuller, "The South Ossetian Campaign for Unification,"

p. 18.

Return to Article

60. For differing versions of the events of 15 July

1989, see Elizabeth Fuller, "Georgian Prosecutor Accused in Inciting Inter-Ethnic

Hatred," Report on the USSR, 2, no. 17 (27 April 1990), p. 13. Georgians

asserted that Abkhazians surrounded and stormed the building where the

exam was to take place, beating members of the examination commission in

the process. After that, Abkhazians moved to nearby streets and continued

to attack innocent Georgians. The Abkhazians contended the Georgians initiated

the violence while they were forced to defend themselves.

Return to Article

61. Pravda, 3 January 1989, translated in CDSP, 41,

no. 1 (1 February 1989), p. 17. Additional measures included mandatory

teaching of Georgian in non-Georgian language schools and increased teaching

of history, archaeology and ethnography of the Georgian Republic.

Return to Article

62. Izvestia, 28 October 1989, translated in CDSP,

40, no 43, (22 November 1989), p. 37.

Return to Article

63. For more detailed analysis of the events of 1989

in south Ossetia, see Fuller, "The South Ossetian Campaign for Unification,

pp. 17-20.

Return to Article

64. Chanturia's National Forum would schedule and hold

an alternative election to the Georgian Supreme Soviet elections for his

"National Congress." His Georgian National Independence Party would win

this election on 30 September 1990, that was boycotted by Gamsakhurdia

and his followers; see Report on the USSR, 2, no. 41 (12 October 1990),

pp. 29-30. However, Chanturia was never able to displace Gamsakhurdia and

assume the leadership of the nationalist movement.

Return to Article

65. Elizabeth Fuller, "Democratization Threatened by

Interethnic Violence," Report on the USSR, 3, no. 1 (18 January 1991),

p. 43.

Return to Article

66. Report on the USSR, 2, no. 35 (31 August 1990),

p. 24.

Return to Article

67. Izvestia, 28 August 19990, translated in CDSP,

42, no. 35 (3 October 1990), p. 29.

Return to Article

68. Despite his coalition's victory Gamsakhurdia would

allege electoral law violations. Chanturia, Gamsakhurdia's rival, was wounded

two days before the election and called the outcome the result of a "fascist-Communist

Pact," as seen in Elizabeth Fuller, "Round Table Coalition Wins Resounding

victory in Georgian Supreme Soviet Elections," Report on the USSR, 2, no.

46 (16 November 1990), p. 16.

Return to Article

69. Hunter, The Transcaucasus in Transition, p. 120.

Gamsakhurdia would never bring Mkhedrioni under control even though Ioseliani

was arrested in February 1991 on what he called fabricated weapons charges

as part of Gamsakhurdia's "fascist" policies; see Report on the USSR, 3,

no. 9 (1 March 1991), p. 38. Ioseliani would later escape and become part

of the coalition of forces that eventually sent Gamsakhurdia into exile.

Return to Article

70. Elizabeth Fuller, "Georgian Parliament Votes to

Abolish Ossetian Autonomy," Report on the USSR, 2, no. 51 (21 December

1990), p. 8.

Return to Article

71. Report on the USSR, 3, no. 7 (15 February 1991,

p. 44.

Return to Article

72. Elizabeth Fuller, "Georgia's Adzhar Crisis," Report

on the USSR, 3, no. 32 (9 August 1991), p. 10.

Return to Article

73. War torn Georgia, and especially South Ossetia,

were devastated by a string of powerful earthquakes on 29 April, 15 May

and 15 June 1991. The quakes killed scores and left thousands homeless.

Return to Article

74. Elizabeth Fuller, "How Wholehearted is Support

in Georgia for Independence?" Report on the USSR, 3, no. 15 (12 April 1991),

pp. 19-20. Districts with high minority populations, in southern Georgia

and Abkhazia, also voted in favor of independence with very high percentages.

Fuller quotes some electoral observers as calling the results "hard to

believe," but were unable to find any "significant irregularities."