Sub-Regional Solutions for African Conflict: The ECOMOG Experiment

byINTRODUCTION

The management of conflict in Africa has been a subject of significant concern to the world community in the post-Cold War era. Images of starvation in Somalia and of genocidal violence in Rwanda have pricked the conscience of the developed world, leading to controversial humanitarian interventions that called into question the ability of the international community to resolve complex intra-state conflicts. Subsequent reactions have ranged from substantial reform of the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) to the United States commitment to train African armies in an African Crisis Response initiative (ACRI). But neither Africa nor the world has yet found a satisfactory solution to the problem of extreme intra-state violence.

One of the earliest of the post-Cold War crises in Africa was a particularly vicious civil war in the small, coastal west African country of Liberia, a conflict lasting from late 1989 to 1997. Despite the scale of the killing, the developed world refused to intervene. Instead, Liberia's west African neighbors, under the loose auspices of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), organized a military intervention in an eight-year long effort to resolve the conflict. Only belatedly did the international community provide some support and assistance.

This military intervention has been - widely and justly - criticized for its many deficiencies, but it also is a highly significant development. It represents the first effort by an African sub-regional organization to conduct military peace operations. It reflects an African attempt to address an African conflict situation without waiting for the assistance of external patrons. And while pessimists may point to its limited effectiveness, it takes but little vision to see this intervention as a harbinger of potential African solutions to some of Africa's pressing security problems.

This article will examine the history of the intervention in Liberia calling appropriate attention to the problems and difficulties. However, the article ultimately will argue that the intervention was considerably less than a failure. A bottom-line suggestion will be that one solution to resolution of African crisis may be found in sub-regional organizations like ECOWAS.

Country Background

Liberia traces its origin to the settlement along its coast in the mid nineteenth century by a small number of freed American slaves. In its early years, this unique society barely survived the vicissitudes of disease and internal conflict. But in the late nineteenth century, the Americo-Liberian community began to colonize the African interior, ultimately incorporating the territory that now comprises the country of Liberia.

However, the Americo-Liberians acted very much like other colonial settlers. They formed an urban coastal society modeled loosely on that of the American south. Political power and economic opportunity remained firmly in the hands of a small family-based elite. The backcountry indigenes were denied all but the most sparing access to the benefits of the country. Americo-Liberians viewed their indigenous fellow-citizens largely as cheap labor to be ruthlessly exploited. Although it was not strongly evident to outside observers, this situation provoked increasing resentment through the twentieth century.

In 1980, Liberia's internal social tensions resulted in an improbable coup d'etat in which a semi-literate army enlisted man from rural, backcountry Liberia, Samuel K. Doe, seized power. With support at the outset from a majority of Liberia's indigenous population, Doe established a military administration purportedly to rule Liberia only until general elections could be held in 1985. By 1985, however, Doe had demonstrated a leadership style similar to the leaders of the regime that he had overthrown five years earlier. He never followed through with his promise to nurture democracy by creating a democratic constitution or by distributing political power and opportunity more equitably. Nor did he tolerate a political opposition. Instead, the leader perpetuated a system of patron-client relationships benefitting both his own ethnic group, the Krahn, and the Mandigo, an ethnic group that cooperated with the Krahn. His government proved particularly inept at managing the country's economy, and graft became increasingly blatant. Doe rigged the 1985 elections to maintain his rule, and continued to promote a system that denied access to the other ethnic groups.

Background to the Conflict

By the late 1980s, Liberia's economy had all but collapsed. While Doe had survived several coup attempts, social tensions in Liberia again had reached crisis proportions. In 1989, an Americo-Liberian, Charles Taylor, created a new political party, the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), and led an armed incursion into northern Liberia from neighboring Cote d'Ivoire. Taylor allied with the Gio and Mano ethnic groups (who had suffered many injustices under Liberia's dictatorship) and began a revolution aimed at taking control of the country. Together, these forces embarked on a campaign of "ethnic carnage that threatened to engulf the whole country."1 Doe pled with the people of Liberia to take up arms alongside the national army, the Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL) against the rebel force. Despite this request, Taylor's NPFL insurgents quickly gained control of most of the Liberian countryside.

By mid 1990, a splinter faction had developed within the rebel force, led by one of Taylor's commanders, Prince Yormie Johnson. Johnson's new group, the Independent National Patriotic Front (INPFL), embarked on an effort to seize political power by fighting both the AFL and the NPFL. Liberia deteriorated into a bloody civil war.

Initially, the international community chose not to involve itself in the conflict. Because of Liberia's historical close relationship with the United States, many Africans assumed that the United States would intervene, but the Bush administration was not interested. The United Nations, taking its lead from the United States, heeding the requests of Africans in the Security Council, preferred to let the west Africans deal with their own problem.2

The responsibility for ending the bloodshed was assumed by Liberia's neighbors in ECOWAS. This group had felt the effects of the civil war to a much greater extend than did countries outside of the region. In response to both regional instability and a heavy refugee flow, ECOWAS created the ECOWAS Monitoring Group (ECOMOG), a force aimed at resolving the conflict, restoring order and establishing a democratically-elected government.3 The ECOMOG force was the first African sub-regional peacekeeping body to intervene in another state.4

The formation of ECOMOG in the absence of a United Nations response was an important development not fully appreciated at the time: the assumption of conflict resolution responsibilities by African sub-regional organizations pointed to a new type of interventionism on the African continent. This apparent shift, in addition to ECOMOG's status as the first African sub-regional peacekeeping operation, qualifies it as a significant case study.

As with most trial endeavors, the operation encountered its share of problems. But a careful analysis of ECOMOG's successes and failures may point to a model for a more efficient sub-regional venture within the framework of an ECOWAS-style operation. The results from this study should inform the debate on future sub-regional models for interventions in Africa.

The Creation of the ECOMOG Operation

In the hopes of creating a plan of action for resolving the issues of Liberia's civil war, Nigeria's leader, General Ibrahim Babangida, then chairman, called a meeting of ECOWAS heads of state and governments in Banjul (The Gambia) in May 1990. Here, he proposed and oversaw the adoption of an ECOWAS Standing Mediation Committee (SMC) "to settle disputes and conflict situations within the Community."5 The resulting SMC was comprised of members from five member nations: The Gambia, Ghana, Mali, Nigeria and Togo.

Shortly after its founding, the SMC met with Liberia's warring parties (the AFL, the NPFL and the INPFL) hoping to negotiate an acceptable ceasefire agreement among the factions.

At its inaugural meeting in July, the committee discussed the Liberian conflict and agreed on a peace plan with the following features: establishment of an immediate ceasefire by the warring parties; establishment and deployment of ECOWAS Ceasefire Monitoring group (ECOMOG) to monitor the observance of the ceasefire by all sides to the conflict; agreement by the parties to the establishment of an Interim Adminstration in Monrovia, pending the election of a substantive government; and agreement by the parties to constitute a substantive government through nation-wide elections to be monitored by ECOMOG.6These terms were unacceptable to the factions, particularly to Charles Taylor, leader of the NPFL, resulting in failure to reach an agreement.

Taylor distrusted the SMC and its peace plan as a Nigerian effort to frustrate his bid for power. He had some justification for these suspicions. Although the official position of ECOWAS, and the Organization of African Unity (OAU), was that Liberia lacked any official government, which meant that Doe was not a legitimate leader, Babangida clearly preferred a Liberia led by Doe, whom Taylor had sought to overthrow since 1989.7 Taylor was aware of Babangida's preferences, and believed the SMC's plans proposed by Babangida posed a direct threat to his own interests. He assumed that because ECOWAS adopted Babangida's plan, the Community had given Nigeria substantial control over the planning of the operation. Although ECOWAS members voted and approved the creation of the SMC, they left the details of the peace plan to the members of the Nigerian-dominated SMC.8 Under this arrangement, the SMC could plan independently of ECOWAS. The SMC members thus could control the aims of the operation. The aims were decided by the five members of the SMC alone, and did not reflect the preferences of all members of the Community.

Because of Nigeria's prejudice toward him, Taylor came to view the entire ECOWAS intervention as a threatening force rather than as a neutral peacekeeping body.9 This significantly undermined the negotiation process. Rather than cooperate with the SMC, the insurgent never wavered in his claim to rule Liberia. He would not even begin to consider any of the terms for peace until the SMC conceded to the removal of Liberian President Doe,10 a demand that was unacceptable to the SMC. Consequently, they deployed the ECOMOG force in the military intervention.

The SMC adopted its immediate goals for the ECOMOG operation in meetings during July and August 1990. These were articulated in the 1990 ECOWAS peace plan for Liberia. The forces were to focus their efforts upon disarming the factions in the expectation that this would stabilize Liberia. In concurrence with this effort, the SMC intended to establish a Liberian interim government to rule the country until free and fair elections could be held, and a democratically elected government could take its place.11 The SMC members chose an Americo-Liberian politician, Amos Sawyer, to run Liberia's interim government, and to work with the faction leaders to create an acceptable administration. The success of these plans required that ECOMOG and the Liberian interim government complement each other: the interim government would create political stability while the west African force maintained the ceasefire.

The Implementation of the ECOMOG Operation

In August 1990, 2,700 ECOMOG troops deployed into Sierra Leone, most of which were Nigerian.12 The ECOMOG force commander, Ghanaian General Arnold Quainoo, believed that the presence of the west African force so near to Liberia's border would cause factions to halt fighting in Liberia's capital of Monrovia. This proved not to be the case. The fighting continued and Quainoo found it necessary to deploy into Liberia. On 25 August 1990, ECOMOG troops landed in Monrovia. Once in Monrovia, the commander's strategy was to intimidate the factions into abiding by a ceasefire, and attempt to impose stability on the capital so that ECOMOG forces could establish a Liberian interim government.13 Their ultimate goal was to create a functioning government and to prepare the country for elections. The two weaker groups, Doe's AFL and Johnson's INPFL, cooperated with this effort. By adhering to the ceasefire, the INPFL convinced the ECOMOG commanders that their group did not threaten Liberian security, and consequently, in late 1990, INPFL leader Prince Johnson was able to assassinate Doe, one of his two rivals.14 Quainoo expected that because the weaker factions had complied with the force, the mission would embody traditional peacekeeping. However, this intimidation strategy did not work on Taylor's NPFL, which fought the intervention and maintained control over most of the country outside of the capital. Taylor refused to cooperate with the other groups, resulting in the adaptation of the mission from peacekeeping to peace enforcement.15

The deployment of ECOMOG troops into Liberia, despite the opposition of some of the Liberian factions, reinforced Taylor's notion that the operation was a threatening force of "armed bandits," attempting to deprive him of his conquests.16 He concluded that ECOWAS was presenting him with "a set of instructions to roll back his forces from Monrovia."17 Having gained control of most of the Liberian countryside, he believed that he had a legitimate claim to rule the country. Taylor refused to cooperate with the ECOMOG force and continued his efforts to subdue the remainder of Liberia, a process that included substantial violence against civilian communities.

The relationship that developed between the architects of the SMC peace plan, primarily Nigeria, and Charles Taylor contributed to his continuing hostility toward the ECOMOG force. Because the SMC goals were so heavily influenced by the Nigerians, he was convinced that Nigerian prejudices toward him were certain to play out in the peacekeeping operation. Still, the rebel leader did participate in various conferences and consultations.

An initial agreement between ECOMOG and the Liberian factions reached at Bamako, Mali in 1990, set out a design for the interim government. It unambiguously reflected Nigeria's efforts to remove power from Taylor's hands: he was to be excluded from participation in the temporary government. Taylor correctly interpreted this move as an attempt to sidestep his authority, depriving him of the control for which he had fought.18 And, in fact, when forces were finally deployed later in 1990, their objectives were to control Taylor and to protect the interim government, plans clearly designed to reduce his power. By allowing Nigeria's prejudice to influence policy, the SMC created an obstacle to the overall success of the operation.

As the ECOMOG intervention progressed after 1990, it also generated substantial controversy in the sub-region. The operation lacked a definitive, authoritative west African mandate. The power of the SMC members, independent of ECOWAS, to dictate the course of the peace operation became a point of contention within the Community. Taylor's insurgent invasion had been supported by Burkina Faso and, at least tacitly, facilitated by Cote d'Ivoire. Both of these countries were sympathetic to Taylor's claims. However, the narrow national goals of individual SMC members, primarily Nigeria, resulted in actions that undermined support for the operation among the other ECOWAS members. As the 1990 peace plan became known in the Community, leaders in both Burkina Faso and Cote d'Ivoire saw that the forces would have an anti-Taylor agenda and expressed their opposition to placing troops in Liberia.19 When the SMC deployed forces despite this objection, the action undermined the broad sub-regional support needed for a successful operation. Burkina Faso and Cote d'Ivoire were motivated to continue supplying arms and training to Taylor's insurgents.20

After troops arrived in August 1990, a number of problems arose in the operation resulting from the lack of expertise with peacekeeping by participating members. For instance, the SMC seriously underestimated the troop strength and logistics necessary for a successful operation. The creators of the ECOMOG force envisioned a short operation.21 They expected to enter Liberia, and quickly take control of the country, establishing an environment suitable for holding democratic elections. When the mission began to drag on over an extended period of time, the unrealistic expectations and inadequacies of the planning became apparent.

The SMC also did not appreciate the complexities in establishing an effective interim government once troops reached Liberia. From the beginning, the ECOMOG-imposed government had very limited capabilities. Taylor, the leader of the strongest faction, refused to acknowledge the interim government's legitimacy or to cooperate under the direction of Amos Sawyer with his rivals in the AFL and the INPFL.22 The success of the operation depended on the cooperation of the factions, which simply did not occur. The inability of both ECOMOG and the interim government to control the environment from the onset significantly compromised the potential for success of the SMC's plan.

In addition to the poor planning and unrealistic expectations for settlement, the SMC was unable to obtain support for the mission from all of the members of ECOWAS. As we have seen, such members as Burkina Faso and Cote d'Ivoire objected to the anti-Taylor aims of the mission. Not all of the member states were capable of shouldering an equal share of ECOMOG expenses, even assuming their agreement with the objectives. The burden of financing the operation initially fell to the countries that had the resources. Nigeria had more resources than the other members of ECOWAS, and consequently provided the most financial support from within the Community.23 Although questionably, the Nigerians have claimed that their ECOMOG costs in Liberia exceeded $4 billion.24 Also, the Nigerians supplied the bulk of the troops and equipment. Many of the members of ECOWAS did not have substantial military resources to commit, and Nigeria, with the largest military in the region, was able to contribute the needed military resources.25 From the onset of the mission in 1990, the Nigerian troops accounted for at least 70 percent of the ECOMOG force.26 This contribution allowed the operation to turn into an extension of Nigerian policy rather than remain a collective ECOWAS effort.

Nigeria's disproportionate role continued throughout the operation, and Nigerian soldiers were responsible for carrying out the majority of the ECOWAS program. Taylor saw this as a threat, and refused to cooperate with ECOMOG, deducing the effort to be an exercise in "Nigerian hegemony."27 Although in 1991 the United States attempted to assist the diversification of ECOMOG by financing the deployment of a 1,500 man Senegalese component, the Nigerians continued to dominate the force.28 Nigeria's role and presence ultimately reduced the acceptance of the ECOMOG force among the factions in Liberia.

Nigerian financial, tactical and logistical domination could have been reduced if the international community had supported the operation from the onset. Initially, the funding that came from the international community was little more than token assistance.29 By 1991, the United States had contributed $2.8 million to ECOMOG and committed additional bi-lateral support to Senegal.30 However, the contributions were still far too small to solve the problem. Although the external bi-lateral aid was intended to diversify the participation in the operation, it was not enough to allow the other contingents to match the efforts of the Nigerian forces.31 However, as the operation developed and its success was increasingly threatened by an unrepresentative composition, the international community displayed more concern and increased its financial support.

By 1993, the United States became more heavily involved, sending a team of military officers to various states in eastern and southern Africa to solicit additional anglophone contingents. A direct result of these efforts were agreements by Uganda and Tanzania, each to deploy a battalion of peacekeepers to Liberia. This contribution lasted from 1994-95. The United States provided some compensation to the east Africans for their participation.32

By February 1994, the United Nations had finally established a presence in the war-torn country, creating the 300-man United Nations Observer Mission in Liberia (UNOMIL). Observer teams were deployed alongside the ECOMOG forces with the aim of monitoring the implementation of the Cotonou Agreement of 1993.33 The observers attempted to restore neutrality and legitimacy to the west African effort. However, this mission ultimately failed because of the relationship between UN observers and ECOMOG troops. UNOMIL relied upon ECOMOG for initiative and logistical support.34 However, this relationship was not reciprocated. None the less, the factions distrusted the UN team and soon concluded that UNOMIL was simply a continuation of the 10,000-man ECOMOG mission.

Finding a Lasting Peace Settlement

To address the underlying issues of the civil war, ECOWAS sponsored a series of peace agreements (starting in November 1990 with the Bamako Agreement) complementing the ECOMOG operation. These summits brought the factions together in an effort to negotiate acceptable terms for peace. From Bamako on, the process of hammering out a peace agreement proved to be more difficult than participants expected, and the ECOWAS-sponsored summits resulted in failure after failure. Initially, the west Africans were unable to mediate effectively between the original warring factions (NPFL, INPFL and AFL). When the Liberians became increasingly frustrated by the peace process and splinter groups developed, the peace process became further complicated.

The ECOWAS Sponsored Peace Agreements35

| 28 November 1990 | Bamako Agreement: All of the warring factions agree to a ceasefire. |

| 30 October 1991 | Yamoussoukro Agreement: All of the warring factions agree to encampment and disarmament of factions under ECOMOG supervision. |

| 17 July 1993 | Geneva Agreement: The NPFL, ULIMO and the Liberian Interim Government agree to a ceasefire. |

| 25 July 1993 | Cotonou Agreement: The NPFL, ULIMO and the Liberian Interim Government agree to encampment and disarmament of the factions under ECOMOG supervision. They also agree to a tri-partite transitional government responsible for organizing general elections in February 1994. |

| 12 September 1994 | Akosombo Agreement: The NPFL, ULIMO and AFL agree to a ceasefire, the installation of a transitional presidency composed of members decided upon by the three factions, and plan for general elections in October 1995. |

| 21 December 1994 | Accra Agreement: The NPFL, AFL, ULIMO-K, ULIMO-J, Lofa Defense Force, LPC, CRC-NPFL and the LNC agree to establish safe havens and buffer zones, to have elections in November of 1995, to demobilize, and to re-adopt the transitional presidency of the Akosombo Agreement. |

| 19 August 1995 | Abuju Agreement: All of the warring factions agree to a ceasefire, a period of disarmament, the creation of a collective presidency, and plan for general elections in August 1996. |

| 17 August 1996 | (Revised) Abuja Agreement: All of the warring factions agree to disarmament, dissolution of all factional militia and plan for general elections in May 1997. |

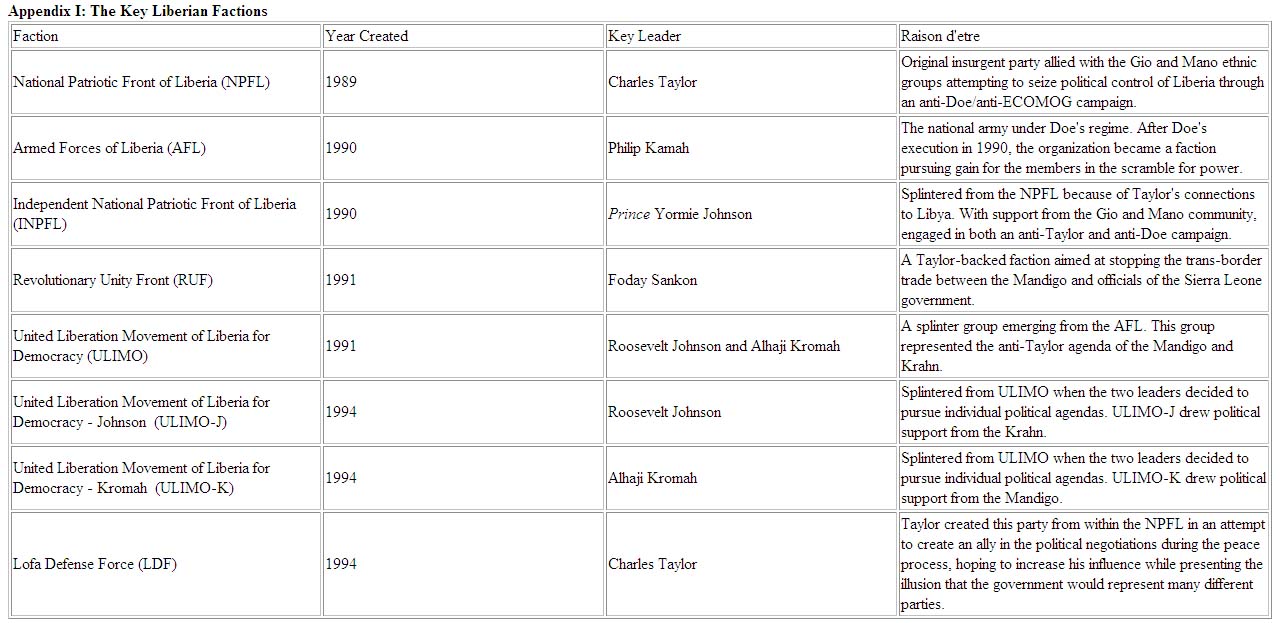

By March 1991, the United Liberation Movement of Liberia for Democracy (ULIMO) emerged as another faction in the Liberian conflict. Its constituency included former members of Doe's government and the AFL, and it aimed to prevent Taylor's bid for power.36 In late 1994, ULIMO split into two rival factions: ULIMO-K and ULIMO-J. This division resulted from the differing agenda of two ULIMO leaders, Alhaji Kromah and Roosevelt Johnson.37 In addition to these groups, several less prominent factions developed. (See Appendix 1, Liberian Factions.) Some aided Taylor in his bid for power, while others fought against the NPFL leader. Not only did the development of more factions add to the confusion, it created more constituencies to placate. The development of new factions within Liberia resulted in a complicated peace process characterized by continual violation of the peace agreements.

The objectives of nearly all of the peace agreements embodied essentially the same goals for Liberia. The warring factions were to cooperate with the Liberian interim government until general elections could be held, establishing a democratically elected government. The factions were to cooperate with ECOMOG forces, whose presence was meant to preserve the ceasefire and control any potential threats to the peace. In order to do so, ECOMOG forces would take charge of disarming the factions, and ensure that the weapons would not be redistributed. In addition to creating a peaceful environment, the force would aid in the resettlement of refugees and participate in voter registration.38 These objectives, though necessary for a resolution of the conflict, remained a source of contention among the factions.

Throughout the many peace summits, the issue of disarmament remained a key obstacle to the negotiation process. The different factions had little confidence in the fairness of enforceability of this provision. A number of the factions were little more than groups of predatory, armed bandits. Loss of weapons meant loss of power to protect their economic and ethnic survival, and possibly future legal retribution. Within the factions, some leaders expressed their disapproval for soldiers who gave up their weapons, threatening execution of those who complied with the ECOMOG disarmament.39 The possibility of the ceasefire breaking down presented the leaders of factions without arms with the threat of losing out in the scramble for power. Consequently, the faction leaders were reluctant to allow their soldiers to disarm until the other factions also began to comply with the disarmament process.40

Another source of controversy relating to the disarmament issue originated from Taylor's distrust of ECOMOG. While hashing out the Yamoussoukro Accord in 1991, he pushed for the condition that each faction should disarm itself and store its own weapons.41 ECOMOG leaders understandably were opposed to this suggestion, as it would permit the factions to resume armed conflict whenever they chose. ECOWAS and Taylor clashed over this issue, and were unable to find a compromise, contributing to the rejection of this particular peace plan.

The inability of the factions to come to an agreement over disarmament details related to other problematic aspects of the peace process. From the onset of the intervention, there was constant disagreement between Taylor and his Liberian opponents over the composition of the interim government. Under ECOWAS plans (included in essentially all of the attempted peace agreements) the leaders of any warring factions were excluded from participating in the interim government, and the leader of the interim government could not become a candidate in the subsequent national election.42 This conflicted directly with Taylor's interests by blocking his personal pursuit of power. Expecting to translate battlefield success into political power, he consistently demanded control over the composition of the interim government. This was a logical extension of his quest to maintain control within Liberia. From the initial Bamako peace agreement in 1990 throughout the ECOWAS operation, Taylor's ultimate goal had been to acquire the power that he had sought since initiating Liberia's civil war in 1989. Excluding him from the interim government directly challenged his basic goal. It is little wonder that Taylor rejected ECOWAS' peace designs.

Taylor's initial response to the creation of the interim government was to install an alternate interim government based in Gbarnga, immediately following 1990 Bamako agreement. The Gbarnga regime was comprised only of members of Taylor's party, the NPFL.43 This act demonstrated his contempt for the authority of the peacemakers, and showed his unwillingness to cooperate with their mission. In creating an alternate government, Taylor signaled his refusal to be excluded from real power in Liberia.

Taylor's participation in the Abidjan negotiations in 1991 again exemplified his attitude toward the ECOWAS efforts. During the negotiations, the NPFL leader expressed his desire to have a broader based interim government (implying his own party be included in the government) yet requested that fourteen of the organizations participating in the conference be disqualified.44 Taylor clearly sought a government dominated by his own party, granting him the political power that he desired. Taylor proposed a plan in which three presidents would run the country. One of the three would be Taylor, another would be the representative from the ECOWAS-sponsored interim government, and the third would be a neutral participant agreed upon by both sides.45 When the proposal gained acceptance by the other parties, Taylor turned it down. In doing so, he seemed to be testing the degree to which the peacemakers estimated his importance in the peace process. He noted how highly ECOWAS valued his cooperation by that point, and concluded that he was the determining factor in the success of the peace program.

Another problem in the peace negotiations related to the conflicting interests of the ECOWAS participants. As the operation dragged on, nations that contributed to the effort began to feel the draining effects of ECOMOG. Some members increasingly were willing to compromise the best possible solution for the quickest, increasing the division within ECOWAS over the plan for the ECOMOG force. This conflict was evident between Ghana and Nigeria after the collapse of the Bamako and Yamoussoukro Agreements. Rather than contribute forces to what might become a "perpetual exercise," Ghanaian officials began to seek areas of compromise, which meant some accommodation with Taylor.46 Nigeria, on the other hand, continued to push for the annihilation of Taylor, refusing to cooperate with the NPFL leader. These divisions among members undermined the negotiation process by creating an environment in which the partiality of certain members (Nigeria) became evident. This severely compromised any perception among the factions that ECOMOG could serve as an honest broker.

When it became clear by 1993 that political differences in ECOWAS were undermining the negotiation process, the international community became more involved in finding a peace agreement. As we have see, the United States endeavored to obtain troops from other African countries, succeeding in obtaining the brief commitment of forces by Senegal, Uganda and Tanzania. The United Nations became involved in the process of finding a peace settlement, entering into negotiations as a neutral actor, adopting the same aims as ECOWAS. Initially, this move appeared to be a positive contribution to the peace process. Under United Nations direction, all parties agreed to the conditions of what came to be known as the Cotonou Peace Agreement of 1993.47 This agreement called for the factions to comply with a ceasefire and cooperate with disarmament and demobilization of the military forces within Liberia. The processes were to be monitored by the Joint Ceasefire Monitoring Committee, an organization comprising members from the United Nations, ECOMOG, NPFL, AFL and ULIMO. The participants agreed to a Liberian National Transitional Government, which would be replaced by a government chosen in general elections. The acceptance of this agreement by all factions seemed likely because of the involvement of a neutral mediator.48 Although unoriginal in its aims, the Cotonou Agreement seemed to be a turning point in the Liberian negotiations.

The agreement following the United Nations involvement also represented another positive aspect to resolving the Liberian conflict. For the first time, the mediators allowed the Liberian factions to "thrash out their differences" among themselves, rather than trying to impose by force a direction for the negotiations.49 In this environment, the factions could address their own concerns for their involvement in Liberia's government with one another, and come to an agreement that was acceptable to all parties.

The involvement of the broader international community appeared to be the missing ingredient in creating a successful peace agreement. This agreement was followed by a six-month period of relative calm. However, the Cotonou Agreement eventually collapsed, calling into question the extent to which the peace process had actually benefited from the United Nation's effort. Failure to create a lasting peace under the Cotonou Agreement was the result of a key factor: the United Nations was unable to elicit trust among the factions. Trust was the crucial component for a successful process of disarmament and demilitarization. Ideally, the United Nations should have been involved in initiating a peace agreement and in the implementation of the monitoring force from the beginning stages of the mission. Early cooperation with ECOWAS would have diversified the troops as well as provided the force with unquestionable legitimacy, providing an internal means of policing the force's activities.

ECOMOG's Degeneration

When the ECOMOG force entered Liberia in 1990, its legitimacy was already questionable. Taylor's mistrust of Nigerian intentions led to his opposition to the west African force. With its prospects already uncertain, the success of the operation required that it go smoothly from that point on, proving its legitimacy and neutrality to the Liberian factions in order to gain acceptance as a peacekeeping force. Unfortunately, the mission soon encountered several additional obstacles, rendering the effort a near failure. Once the ECOMOG force had established itself in Liberia, its legitimacy immediately began to deteriorate.

The ECOMOG mission was never clearly defined; its objectives were imprecise and constantly changing. These deficiencies were compounded by inept planning. Several of the principle African components of ECOMOG's diversified force ultimately developed increasing reservations about the mission, and began to reevaluate their involvement in the endeavor. Some contributing members pulled their troops out after coming to the realization that their military intervention was ineffective.50 Despite the withdrawal of other contingents, Nigeria maintained its commitment to the operation. Taylor's opposition to the Nigerian component increased as the Nigerian troops, increasingly entrenched in Liberia, began to pursue explicit Nigerian interests and personal profit.

Nigerian troops began to engage in questionable activities for a peacekeeping contingent. Rather than act as a neutral force, they took sides between the factions. Nigerians viewed Taylor as the source of the conflict because his refusal to adhere to the conditions of the peace settlements slowed the peace process and prolonged the involvement of the ECOMOG force. Nigeria's contempt for Taylor was evident when its troops began to conduct combat operations against the NPFL.51 In targeting Taylor, the Nigerians hoped to resolve what they considered the key obstacle to a timely peace in Liberia.

When the Nigerians aimed their efforts at fighting Taylor, they found support from the other Liberian factions. Operating on the premise that "the enemy of my enemy is my friend," the Nigerians aided these groups in their attempts to reduce Taylor's power.52 ECOMOG supported several of the competing anti-Taylor factions by providing weapons, ammunition, transportation and intelligence.53 Nigerian peacekeeping forces assisted the INPFL and the AFL immediately following their arrival in Liberia.54 Not only did this shatter any aura of neutrality for the peacekeeping force, it also prolonged the conflict. Nigerian actions conflicted with the initial aim of the mission: to create a lasting peace within Liberia. ECOMOG's support of Taylor's opponents placed further strain on its relationship with the factions leader, perpetuating his distrust of the troops, and making them his principle adversary.55

Contributing support to the factions also raised another issue that cast doubt on the legitimacy of ECOMOG. In supporting various Liberian groups, the Nigerians were condoning flagrant violations of human rights. The Liberian factions were guilty of egregious human rights abuses, including brutal torture and execution of civilians who were suspected of sympathizing with NPFL. ECOMOG's cooperation with these groups signaled that it was more committed to finding a quick solution than to protecting human rights.56

By 1993, the Nigerian troops had begun engaging in commercial ventures with the anti-Taylor factions. The Liberian Peace Council (LPC), one of the various Liberian groups that emerged as a competing actor struggling to control Liberia, developed a particularly close relationship with the ECOMOG soldiers. Together, the Nigerians and the LPC exploited the resources along the Ivoirian border, forcing the population to work in rubber factories and engage in the timber trade.57 This type of relationship prevented the force from gaining the trust of Liberians who were not involved in business ventures with ECOMOG troops. The faction leaders acting with the Nigerians were in a better situation than their opponents, who in adhering to the various peace agreements and giving up their weapons, stood to lose access to the resources, which translated into the loss of political power. The business ventures seriously undermined ECOMOG's claim to neutrality, compromising its legitimacy as a peacekeeper among the warring factions.

Nigerian officers also dominated the ECOMOG staff, particularly in the logistics function. This led to inevitable accusations that Nigerians favored their own forces in distribution of ECOMOG resources, or that they diverted ECOMOG resources for personal profit. Since resources were in very short supply anyway, such accusations undermined the morale of other contingents, and were an obstacle to efforts encouraging other African countries to join the coalition.

The shortcomings of ECOMOG ultimately resulted in an inefficient peacekeeping force. The inability of the force to maintain neutrality in its endeavors created a situation in which the factions lost faith in the peacekeepers. Rather than serving as an organization maintaining peace for the good of Liberia, ECOMOG appeared to be a mere cover for foreign exploitation. ECOMOG deteriorated to "an inadequate peacekeeping force . . ." which prolonged the ". . . war and weakened regional stability."58 The west African peacekeeping operation became part of the problem, rather than part of the solution.

After the 1996 Abuja Agreement, Liberia's prospects for peace began to improve. By now, virtually all participants recognized that Taylor could not be denied a leading role in post-war Liberia. A profound war-weariness extended even to the ranks of faction zealots. Liberia's warring parties finally began to cooperate with one another and follow through on the disarmament and demilitarization processes. Within Liberia, the factions prepared for general elections. Consequently, the 10,000 ECOMOG troops that remained in Liberia were able to assume a traditional peacekeeping role, monitoring the implementation of a peace agreement without resorting to force.59 Although the elections were subsequently postponed from May 1997 until July 1997, the implementation of the Abuja Agreement went smoothly.

On 19 July 1997, Liberia finally held its general elections. ECOMOG troops stationed at the polls oversaw the process. International observers described the voting as reasonably free and fair. Not surprisingly, Liberia's voters favored Charles Taylor, who won with nearly 75 percent of the vote.60 Although Liberians may have based their vote on fear of NPFL ferocity and continued violence if Taylor lost, his election was followed by a long peace that has lasted up until the present.61

Evaluating ECOMOG's Model for Sub-Regional Peacekeeping

In retrospect, it is easy to look back on the ECOMOG operation and criticize the effort. Although Liberia's civil war finally ended and the factions came to cooperate with one another, ECOMOG's role throughout the process was controversial. Its intervention only delayed the inevitable: Taylor's ascension to the presidency.

The ECOMOG operation itself was also plagued with problems that have seemingly continued beyond the Liberia intervention. In 1998, ECOMOG intervened in Sierra Leone's civil war (itself something of a spin-off of Liberia's travail). This time, however, over 90 percent of the ECOMOG force were Nigerian. ECOMOG seemingly had become a wholly-owned subsidiary of Nigeria, a situation that has troubling implications for the sub-region.

However, it would be very short-sighted to view the ECOMOG intervention in Liberia as a complete failure. ECOWAS undertook an activity for which there was no sub-regional precedent: it organized and conducted a military operation requiring a capacity for both peacekeeping and peace enforcement. It drew entirely upon its own resources during the initial stages of this effort. As a result of the eight-year ECOMOG intervention, a number of west African military officers developed an impressive expertise in the organization and conduct of peace operations. Part of this expertise was developed through agonizing evaluation of ECOMOG's deficiencies.

It is unclear whether or not an intervention by the United Nations (or any other external actor) could have been more successful in working with the factions. It is instructive to recall, for instance, some similar United Nations interventions. This would include the difficulty experienced by UNOSOM II's effort to reconcile Somalia's warring clans in 1993 and 1994, UNAMIR's failure to halt the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, or the inability of UNAVEM I and UNAVEM II to facilitate peace between the government and rebels in Angola in the 1990s.

Whether or not it used the capacity effectively, ECOMOG could communicate with the factions. It was able to bring them to the conference table repeatedly. When a seemingly durable peace finally came to Liberia, it was as a result of a free and fair national election, not as a result of Taylor's military conquest. To achieve the tranquility required for such elections, Liberia's competing factions first had to come to some consensus through an intensive process of consultation, a process ultimately facilitated by ECOMOG.

The International Contribution

ECOMOG's key problems while working with the factions were related to issues of neutrality and trust. The primary cause of these issues was the disproportionate Nigerian presence. Because of their limited means, the other members of ECOWAS were unable to contribute more to the operation. This compromised the apparent legitimacy of the mission. The international community could have attenuated this problem by being more involved with ECOMOG from the outset, providing the resources that it needed to diversify the mission. This could have resulted in an operation with broader participation and one that was truly a sub-regional (or even a regional) effort.

In addition to added resources, the international community could have provided a robust United Nations presence from the onset of the operation. If a United Nations mission had been more involved in the peace process, and had commenced earlier, it may have been more successful than ECOMOG in gaining the trust of the factions. When UNOMIL became involved in 1994, it initially brought the neutrality to the operation that the ECOMOG forces lacked. The problem was that in cooperating with ECOMOG after it had lost faction leaders' trust in its neutrality, UNOMIL also became suspect. If it had been involved earlier on, the United Nations might have provided the neutrality and legitimacy to the operation that was needed from the beginning.

When future conflicts develop in Africa, the international community, represented mainly by the United Nations, should not underestimate the value of an international mandate that lends an important authority to any intervention. The early interest of the international community could help organizations to avoid the capture of an operation by a hegemon such as Nigeria. Nor should an international coalition avoid early cooperation with sub-regional organizations. Such cooperation probably would be less expensive than a typical United Nations peacekeeping operation and probably would require less effort by the international community than traditional interventions. In utilizing ECOMOG's model of a sub-regional force, the international community could continue to benefit from local familiarity with political issues and geography, and local actor's obvious interest in resolving a conflict so close to their own borders.62 In order for such interventions to achieve their potential, the United Nations and sub-regional organizations should act early on. This requires planning for the future and commitment to common training that would facilitate quick building of peacekeeping coalitions comprised heavily of sub-regional forces.

Both the Africans and the international community seem to have arrived at this conclusion. Since 1994, the United Nations organization has significantly reformed its Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Among other improvements, DPKO now maintains a 24-hour watch center that can provide early warning of impending crises and better communications with deployed personnel. It also has developed a listing of military units that various countries have offered to provide on relatively short notice in a United Nations response to crisis (the standby force list.) These United Nations reforms could result in more timely, coherent United Nations interventions.

African actors have become more interested in regional responses to African crises. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) has since 1994 devoted considerable attention to development of a conflict resolution capability. In April 1997, Zimbabwe hosted an exercise, designated Blue Hungwe, which tested the capacity of southern African countries to respond militarily to complex humanitarian emergencies. Another southern African exercise, Blue Crane, was conducted in South Africa in late 1998. The Senegalese hosted a peace operations exercise in February 1998 designated Guidimakha, sponsored largely by the French. It involved contingents from several west African countries, France, the United Kingdom and the United States. In November 1997, retired Nigerian general and statesman Joseph Garba hosted a conference in Abuja attended by both west African officials with experience in ECOMOG and southern African officials connected to the emerging SADC conflict management infrastructure. The explicit purpose of the conference was to share lessons learned in organizing for sub-regional conflict resolution. These developments display a growing conviction in Africa that sub-regional organizations like ECOWAS or SADC can play key roles in conflict management.63

Developed countries in the West have shown interest in building African sub-regional capacity. Since the early 1990s, French and British training programs in Africa have increasingly stressed sub-regional peacekeeping operations. Notable in these efforts are the British Centers of Excellence programs with the Ghanaian and Zimbabwean Staff Colleges. French efforts have included a program designated RECAMP (Le Renforcement des Capacites Africaines de Maintien de la Paix.) The government of Denmark has sponsored the creation of a Peacekeeping Institute associated with the Zimbabwe Staff College.

The United States has undertaken a significant foreign policy initiative to assist African countries in building a capacity for peace operations. In 1997, the United States implemented a training program, the African Crisis Response Initiative (ACRI), which provides some of the basic training and limited non-lethal equipment needed for peacekeeping operations.64 Although the ACRI currently is a bi-lateral agreement between the United States and each of the seven participating countries, it could eventually grow into a robust regional peace operations capacity under the purview of African sub-regional organizations, yet linked at the same time to the United Nations. The United States has made strenuous and promising efforts to tie the ACRI into ongoing French and British military training programs in Africa. Peace operations training sponsored by the United States and European countries stresses technique and practice endorsed by the international community. The resulting consistency could make partnerships between African forces and international forces much more effective. It is possible, though by no means inevitable, that sub-regional organizations will assume responsibility for continuing these efforts.

As a concluding observation, it should be stressed that improving the capacity for sub-regional peace operations - while important - is by no means the sole answer to African conflicts. The civil war in Liberia was the result of larger social problems, including rule by an unrepresentative and exploitative elite not accountable to the society being served. This created economic disaster and an unhealthy political environment, where the only way to gain power was to take it.65 The eventual outcome was civil war. When ECOWAS attempted to deal with this situation and resolve the conflict among the warring factions, it could not resolve the fundamental social issues. It could only attempt to suppress the symptoms in the hope that his would provide Liberians with an otherwise unattainable opportunity to deal with the core ills.

Appendix 1: The Key Liberian Factions

Endnotes

1. Comfort Ero, ECOWAS and the Sub-Regional Peacekeeping

in Liberia. http://www-jha.sps.cam.ac.uk/a/a010.htm

Return to Article

2. Clement E. Adibe, "The Liberian Conflict and the

ECOWAS-UN Partnership," Third World Quarterly, 18, no. 3 (1997), p. 471.

Return to Article

3. Mark Huband, "The Power Vacuum," Africa Report,

(January-February 1991), p. 30.

Return to Article

4. William O'Neill, "Liberia: An Avoidable Tragedy,"

Current History, 92 (1993), p. 216.

Return to Article

5. Adibe, "Liberian Conflict," p. 473.

Return to Article

6. Ibid.

Return to Article

7. Interview with LTC Anthony D. Marley, (US Army,

retired) US Defense Attache to Liberia throughout the ECOMOG intervention.

Return to Article

8. Herbert Howe, "Lessons of Liberia: ECOMOG and Regional

Peacekeeping," International Security, 21, no. 3 (1997), p. 152.

Return to Article

9. Carolyn M. Shaw and Julius O. Ihonvbere, "Hegemonic

Participation in Peace-Keeping Operations: The Case of Nigeria and ECOMOG,"

International Journal on World Peace, 13, no. 2 (1996), p. 36.

Return to Article

10. Adibe, "Liberian Conflict," p. 473.

Return to Article

11. Ibid.

Return to Article

12. Howe, "Lessons of Liberia," p. 154.

Return to Article

13. Ibid.

Return to Article

14. Tunji Lardner, Jr., "An African Tragedy," Africa

Report, (November-December 1990), p. 14.

Return to Article

15. Interview with LTC Anthony Marley.

Return to Article

16. Peter Da Costa, "Good Neighbors," Africa Report,

(July-August 1991), p. 22.

Return to Article

17. Adibe, "Liberian Conflict," p. 474.

Return to Article

18. Huband, "Power Vacuum," p. 28.

Return to Article

19. Shaw and Ihonvbere, "Hegemonic Participation,"

p. 36.

Return to Article

20. Ero, ECOWAS.

Return to Article

21. Howe, "Lessons of Liberia," p. 165.

Return to Article

22. Huband, "Power Vacuum," p. 29.

Return to Article

23. Da Costa, "Good Neighbours," p. 22.

Return to Article

24. Interview with Col Dan Henk, US Army Attache accredited

to Zimbabwe, Botswana, Zambia, and Tanzania, 1992-94.

Return to Article

25. Shaw and Ihonvbere, "Hegemonic Participation,"

p. 37.

Return to Article

26. Ero, ECOWAS.

Return to Article

27. Da Costa, "Good Neighbours," p. 22.

Return to Article

28. Ibid. See also, Robert Mortimer, "Senegal's Role

in ECOMOG: The Francophone Dimension in the Liberian Crisis," Journal of

Modern African Studies, 34, no. 2 (1996), p. 297.

Return to Article

29. Shaw and Ihonvbere, "Hegemonic Participation,"

p. 53.

Return to Article

30. Costa, "Good Neighbours," p. 23.

Return to Article

31. Ibid.

Return to Article

32. Interview with Col Dan Henk.

Return to Article

33. Adibe, "Liberian Conflict," p. 477.

Return to Article

34. Ibid., p. 478.

Return to Article

35. Table adapted from Appendix 1 in Ero, ECOWAS.

Return to Article

36. Ibid.

Return to Article

37. William Reno, "The Business of War in Liberia,"

Current History, 95 (1996), p. 214.

Return to Article

38. Peter Da Costa, "Talking Tough to Taylor," Africa

Report, (January-February 1993), p. 19.

Return to Article

39. Max Amadu Sesay, "Politics and Society in Post-War

Liberia," Journal of Modern African Studies, 34, no. 3 (1996), p. 406.

Return to Article

40. Cindy Shiner, "A Disarming Start," Africa Report,

(May-June 1994), p. 62.

Return to Article

41. Da Costa, "Good Neighbours," p. 22.

Return to Article

42. Kenneth Best, "The Continuing Quagmire," Africa

Report, (July-August 1991), p. 40.

Return to Article

43. Ero, ECOWAS.

Return to Article

44. Best, "Continuing Quagmire," p. 40.

Return to Article

45. Ibid.

Return to Article

46. Mark Huband, "Targeting Taylor," Africa Report,

(July-August 1993), p. 30.

Return to Article

47. "United Nations Observer Mission in Liberia,"

http://ralph.gmu.edu/cfpa/peace/unomil.html.

Return to Article

48. Da Costa, "A[nother] Plan for Peace," Africa Report,

(September-October 1993), p. 21.

Return to Article

49. Ibid., p. 22.

Return to Article

50. Best, "Continuing Quagmire," p. 41.

Return to Article

51. Huband, "Targeting Taylor," p. 31.

Return to Article

52. Janet Fleischman, "An Uncivil War," Africa Report,

(May-June 1993), p. 58.

Return to Article

53. Howe, "Lessons of Liberia," p. 156.

Return to Article

54. Anthony Marley, "Too Many Cooks in the Kitchen:

International Intervention in Liberia," Small Wars and Insurgencies, 8

(1997), p. 115.

Return to Article

55. Fleischman, "An Uncivil War," p. 58.

Return to Article

56. Ibid.

Return to Article

57. Reno, "Business of War," p. 214.

Return to Article

58. Howe, "Lessons of Liberia," p. 146.

Return to Article

59. "Trip Report: Visit to Liberia July 16-21, 1997"

http://www.emory.edu/CARTER_CENTER/TRIPS/libertrp.htm.

Return to Article

60. "Trip Report: Visit to Liberia July 16-21, 1997."

Return to Article

61. Mary Fitzpatrick, "Liberia's Tenuous Election,"

Christian Science Monitor, 1 August 1997, p. 20.

Return to Article

62. Howe, "Lessons of Liberia," p. 160.

Return to Article

63. Interview with Col Dan Henk.

Return to Article

64. Dan Henk and Steven Metz, The United States and

the Transformation of African Security: The African Crisis Response Initiative

and Beyond. (Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 1997),

p. 25.

Return to Article

65. Howe, "Lessons of Liberia," p. 148.

Return to Article