by

Horace Bartilow

INTRODUCTION

You, by giving in, would save yourself from disaster . . . your actual resources are too scanty to give you a chance of survival against the forces that are opposed to you at this moment. You will therefore be showing an extraordinary lack of common sense if . . . you still fail to reach a conclusion wiser than anything you have mentioned so far.[1]A differentiation arises between ourselves, the we group or in-group, and everybody else, or the others-groups, out-group. The relation of comradeship and peace in the we-group and the hostility and war towards others-groups are correlative to each other. The exigencies of war with outsiders are what make peace inside.[2]

The above statements represent two disparate and theoretically significant bodies of literature in the study of conflict. The first concerns itself with the study of external coercion through diplomacy or coercive diplomacy, and the second, often referred to as the in-group/out-group hypothesis or the theory of conflict and cohesion, is guided by the central proposition that involvement in external conflict increases internal cohesion. The former statement is a demonstration of an external power's use of coercive diplomacy to force the target to comply with its objectives without resorting to military force. The latter statement attempts to explain why the target is likely to become internally cohesive in reaction to external pressure.

Coercive diplomacy employs threats or limited force to persuade a target state to stop short of a goal (Type A) or reverse action already implemented (Type B) without escalating into a fully blown war. Little is known, however, about the Type C variant of coercive diplomacy; namely, the ability of an external power to persuade a target to not simply reverse an action or stop short of an objective, but more importantly to relinquish power or make fundamental changes within its government.[3] Given the offensive nature of this variant of coercive diplomacy the state that employs the strategy risks fragmenting its own domestic coalition and is unlikely to secure sufficient domestic support that is necessary in order to pursue its coercive diplomatic objectives. It is noted that while diplomatic success under Type C conditions are not impossible they are highly improbable.[4]

The coercive diplomacy literature, therefore, argues that under Type C conditions an external power's own internal fragmentation weakens that state's ability to persist in what it demands from the target. According to the literature on conflict and cohesion, since the Type C variant of coercive diplomacy represents the most severe form of external pressure, the intensity of this external threat should increase the target's internal cohesion and his resolve to resist. Essentially, the Type C demands of an external power are expected to deepen the target's internal cohesion and resistance, which increases the possibility that the crisis can only be resolved by military force. While the theory of coercive diplomacy emphasizes the external power's internal fragmentation that weakens his resolve to persist, conflict and cohesion theory emphasizes the target's internal cohesion that strengthens his resolve to resist. Both theories agree, albeit for different reasons, that achieving compliance under Type C conditions is improbable.

This article attempts to answer a central question: Under what conditions is Type C coercive diplomacy likely to succeed? It is argued that the success of Type C coercive diplomacy is possible even when the coercive power has little domestic support for the measure. The success of the strategy is a function of several factors: the time duration over which conflict takes place with an external power; the subsequent stress among the target's coalition members; the ensuing changes in the internal distribution of power within the coalition; and coalition member's adoption of multiple and competing bargaining solutions to resolve the conflict with the external power are important domestic variables that interacted with each other as well as with external coercion to erode and fragment the cohesion within the coalition which facilitates defection and ultimately produce compliance under C Type diplomatic conditions.

The case of the Clinton administration's policy towards Haiti's de facto military junta is the most recent demonstration of the Type C variant of coercive diplomacy. In the case of Haiti, it is argued that sanctions indirectly fragmented the de facto coalition and politically weakened the military leadership's position within the Haitian military and its will to resist an invasion. American diplomatic pressure and President Clinton's threat to use military force to eject the junta, while necessary to the final resolution of the conflict, would not have been sufficient to convince the de facto junta to cede power peacefully without offering some resistance to the American troops that entered Haiti.

American Type C Coercion of the Haitian Junta

Some students of Haitian politics have argued that it is simply wrong to characterize US policy toward the Haitian junta in terms of pursuing Type C coercive objectives. These scholars argue that the policy objectives of both the Bush and Clinton administrations were intended to force the de facto regime to accept the creation of a government of national consensus Ð where political power would have been shared between Aristide's popular democratic sector and the military and business elite who had toppled President Jean-Bertrand Aristide's government. In fact it is argued that US officials were quite sympathetic to the interests of the Haitian military and by attempting to force an accommodation between the Haitian Right and Left, the Bush and Clinton administrations sought to use the Right to weaken the power of the democratic sector and contain the socialist excesses of Aristide.[5] This depiction of US objectives toward the Haitian junta is correct, but it does not violate the essential theoretical requirements for understanding US policy toward Haiti in terms of Type C coercion. By definition, a state pursues the Type C variant of coercive diplomacy when it forces the target to make fundamental changes within its government or to completely relinquish its hold of political power.[6] Since the Clinton administration's primary objective was to initially force the de facto junta to make fundamental changes within the regime, such as an acceptance of a political accommodation with deposed Aristide, and then later demanded the termination of the regime itself, both objectives concerning the Haitian junta are fully consistent with the theoretical conceptualization of Type C coercive diplomacy.

The argument presented here begins in the next section with a discussion of the theories of coercive diplomacy and conflict and cohesion. In the development of this argument aspects from both theories are integrated to develop theoretical propositions that specify the necessary pre-conditions that make compliance under Type C conditions possible. An analysis of US diplomatic efforts in restoring Haiti's experiment with democracy serves to empirically test the theoretical propositions and the argument that is advanced in this article. The concluding section discusses the foreign policy implications of the argument in light of its relevance to recent policy discussions regarding the removal of the Iraqi leadership from power via Type C coercive diplomacy.

The Theory of Coercive Diplomacy

The requirements for successful coercive diplomacy are that the external power must create in the target's mind the fear of unacceptable cost, which will weaken that state's motivation to resist. Essentially, coercive diplomacy uses threats not to physically impair the target, but to primarily destroy that state's will to resist.[7] There are three central variables that help explain the success of coercive diplomatic efforts. First, there must be an asymmetry of motivation that favors the external power employing coercive diplomacy. Second, the target must be sufficiently convinced that the punishment for non-compliance is credible and unacceptable. And third, the external power must be able to employ the appropriate mix of positive incentives and negative threats.[8]

Asymmetry of Motivation

The external power's choice of diplomatic demands will affect the strength of the target's motivation to resist and the strength of the external's power's own motivation to persist in the deployment of coercive diplomacy. Motivation is a function of each party's conception of what it has at stake in a given crisis, how important are the issues that are at stake to both parties, and what cost is each party willing to pay in order to protect or advance their respective interests. If the external power demands something from the target that is more important to it than the target, then the asymmetry of motivation strongly favors the external power and under these conditions coercive diplomacy is likely to succeed. On the other hand, if the external power demands something from the target that extends beyond its own vital interests, then the asymmetry of motivation favors the target and the external power's coercive diplomatic efforts are likely to fail.[9] In addition, the more extensive the external power's demands become, as is the case with Type C diplomacy, and the more disconnected they appear to its primary security interests, the more unlikely will the external power be able to secure domestic support for his coercive diplomatic efforts. Under these conditions the asymmetry of motivation to resist favors the target over the external power and coercive diplomacy is likely fail.[10]

Does this variable provide an adequate explanation of the successful diplomatic outcome in Haiti? Given the Bush and Clinton administration's Type C demands on the Haitian junta the asymmetry of motivation was disadvantageous to the US government and favorable to Haiti's de facto military junta. Little domestic consensus existed regarding the policy to remove the Haitian junta from power; neither was there consensus over the means through which coercion should be exercised. The CIA, the Pentagon and congressional Republicans opposed the restoration of President Aristide,[11] while the American public and congressional Democrats stood opposed to any talk of the use of force.[12] Given the successful diplomatic outcome in the Haitian crisis, the asymmetry of motivation that should have weakened the Clinton administration's resolve to persist and strengthened the Haitian junta's resolve to resist is not a reliable predictor of the diplomatic outcome in the Haitian crisis under Type C conditions.

The Fear of Unacceptable Punishment

For coercive diplomacy to succeed the external power's coercive punishment for non-compliance must be perceived by the target to be so overwhelmingly credible and potent that it becomes convinced that compliance with the external power's demands is the best course of action rather than accept the cost of non-compliance.[13] The major problem with this variable is that it is difficult to draw inferences between the target's perception of the external power's credibility and its motivation to comply or resist the external power's demands. This problem is prevalent in the conventional explanation of why the Haitian junta eventually complied with US demands after successfully resisting US pressure from 1991 to September 1994. National Security Advisor Anthony Lake asserted that democracy was restored to Haiti because "diplomacy was backed by power."[14] This assertion assumes that the Haitian junta's perception of US credibility for the use of force changed by 1994, as a result of President Clinton's ultimatum and the last minute mission of Jimmy Carter, Colin Powell and Sam Nunn who supposedly convinced the junta that a military invasion would follow if they refused to cede power.

The problem with this explanation is that it assumes that the US threat to use force was more believable in 1994 than at any other time during the crisis. This assumption is simply not supported by the events in the Haitian case. Ultimatums and the threat to use force by the US and the Organization of American States (OAS) were nothing new during the diplomatic crisis with the Haitian junta. In fact, as the Harlan County incident[15] showed, in October 1993 the Haitian junta forcefully blocked the entry of US troops who were sent to oversee the implementation of the ill-fated Governors Island Accord which established the terms for the process of democratic restoration in Haiti. If the Haitian junta stood firm and forcefully repelled the entry of US troops into Haiti and in the process sank the Governors Island Accord, why would they simply comply as a result of another ultimatum and threat to use military force? It is, therefore, difficult to draw direct inferences between the Haitian junta's motivation to comply with US external pressure and their perceptions of the credibility of the US to use military force against them.

Positive Incentives and Negative Threats

The theory of coercive diplomacy claims that the success of the strategy is also contingent on the external power's credible implementation of an appropriate mix of both positive inducements and negative punishments that encourages the target to comply. The assumption here is that the mixture of incentives and coercive measures changes the preferences among the target's central decision makers and weakens their motivation to resist. But the variable does not specify the conditions under which that mix can change the target's preferences. What is the "appropriate" mixture of incentives and coercive measures and how does it actually weaken the target's resolve to resist external coercion? Without specification it is difficult to infer that changes in the target's preference to comply is attributable to the mixture of diplomatic carrots and sticks.

The variables that are central to the theory of coercive diplomacy, by themselves, do not explain the diplomatic outcome in Haiti. The exclusive focus on the external power's motivation and the target's perceived credibility of the instruments of external coercion limits the explanatory power of the theory's central variables. By integrating aspects of coercive diplomacy with the variables that are posited by the theory of conflict and cohesion important insights emerge that specify the links between external coercion and its effect on the target's motivation toward greater resistance or compliance.

The Theory of Conflict and Cohesion

The proposition that external conflict increases internal cohesion has been a major area of social science research for the past six decades. Since a full review of this expansive literature is beyond the scope of this article, discussion in this section is limited to a review of the necessary pre-conditions or intervening variables that are identified by the literature.

The original formulation of the proposition is credited to the work of sociologists. These theorists recognized that external conflict does not necessarily increase internal cohesion. The proposition holds only in the presence of certain intervening variables. First, the target's coalition must exist before the onset of conflict with the external power and must see itself as a coalition. Second, the external power must be seen and recognized as a threat to each individual member of the coalition[16] and all members must share equally in the suffering and danger that results from the external conflict.[17] A third intervening variable concerns itself with the internal structure of the target's coalition. Anthropologists have noted that conflict with an external enemy increases internal cohesion only when the target has a centralized structure of power that allows it to forcefully intervene domestically to maintain cohesion among members of its coalition.[18] A centralized political system allows the target to effectively utilize force to coerce coalition members in order to maintain internal cohesion during the conflict with the external enemy. The greater the degree of centralized power the greater the degree of internal cohesion.[19]

An additional set of intervening variables can be drawn from the social psychology literature on group dynamics. First, the target's internal cohesion decreases if there is no solution to the crisis with the external enemy. Second, the target's internal cohesion increases if there is a cooperative solution to the crisis. Third, internal cohesion will disintegrate if the target's coalition members adopt competitive solutions to the crisis with the external enemy.[20] This outcome can be attributed to the fact that individual coalition members may find the coalition powerless to deal with the external enemy, and may believe that the individual efforts of each member is the best way to resolve the crisis.[21] Therefore, each coalition member must see the conflict with the external enemy as solvable by the efforts of the coalition and see the coalition as a source of support.[22] Fourth, internal cohesion increases when the rewards to individual coalition members for staying with the coalition are greater than the rewards for defection.[23] Fifth, internal cohesion is said to decrease as the time duration of the external conflict increases. Some researchers have noted that when "disaster threatens over a long period of time, the cohesive forces that hold a group together are subject to strain [that result in] various forms of bizarre and schismatic behavior."[24]

The major limitation of the social science literature is that there is no conceptual agreement as to how the independent variable (external conflict) and the dependent variable (internal cohesion) should be defined and operationalized. In sociology some researchers distinguish between conflict and competition while others do not. Other researchers argue for a general definition of external conflict while others insist on creating separate categories of conflict so that they can be studied differently.[25] While sociologists recognize the conceptual confusion of the independent variable there is limited discussion and recognition of the conceptual ambiguity of the dependent variable.

The same is true of the social psychology literature.[26] Some social psychologists tend to dichotomize the independent variable in terms of the existence or non-existence of external threat. Still others argue that the independent variable should be measured in terms of the different levels of external threat so that all possible thresholds of conflict can be included in the analysis.[27] Social psychologists are equally divided regarding the definition and operationalization of cohesion. Some researchers suggest using various dimensions and definitions of cohesion while others do not.[28]

The Exogenous and Endogenous Variables

In this analysis the independent variable (external coercion) is defined in terms of the various levels of negative threats and positive incentives that can be utilized by an external power against the target. These instruments of external coercion not only vary in the degree of their intensity, but also can escalate through varying thresholds ranging from economic sanctions, naval blockade, limited military strikes to direct military intervention. Each level and intensity of negative threat is coupled with the proportionate level of concessions to provide incentive to the target to help induce his compliance.

Throughout this analysis the term coalition refers to the informal agreement and implicit understanding among political actors to coordinate their strategies to increase their collective power vis-ˆ-vis other political actors with conflicting interests. The dependent variable (coalition cohesion) is defined in terms of "the resultant of all forces acting on members to remain in the [coalition]."[29] These forces are determined jointly by how power is internally organized within the coalition, the attractiveness of the coalition to its members, the attractiveness of competing coalitions or alternative options, and the benefits and costs associated with leaving the coalition. The attractiveness of a coalition consists of two components: intrinsic attraction and instrumental attraction.[30] Intrinsic attraction refers to coalition members having strong preferences for each other based on a shared ideology, values or a set of beliefs. Instrumental attraction refers to coalition members having an attraction toward the attainment of a specific goal that the coalition mediates for its individual members. Therefore, coalition membership becomes important because it represents the means by which individual members can attain their goals.

Coalition cohesion is, therefore, conceived as a function of the internal organization of power within the coalition, which is measured in terms of the centralization of power and the use of coercion to increase the cost of defection. The greater the degree of centralized power or attempts to alter the distribution of power, the lower the coalition's attractiveness, the higher the attraction of alternative options, the higher the benefits of defection, and hence the lower the level of the coalition's internal cohesion.

By integrating aspects of coercive diplomacy with the theory of conflict and cohesion the following propositions emerge that specify the conditions in which compliance under C Type conditions is possible. First, as the time duration of external coercion (negative threats and positive incentives) increases, stress among domestic coalition members increases and internal cohesion decreases. Second, increasing levels of external coercion (negative threats and positive incentives) increases internal cohesion only when, in response to external coercion, domestic coalition members adopt the same bargaining strategy to resolve the crisis with the external power. Third, increasing levels of external coercion (negative threats and positive incentives) lowers internal cohesion only when, in response to external coercion, domestic coalition members adopt multiple and competing bargaining strategies to resolve the crisis with the external power. Fourth, increasing levels of external coercion (negative threats and positive incentives) increases internal cohesion only when, in response to external coercion, attempts to centralize power internally increase the distribution of benefits for all members of the coalition. Finally, increasing levels of external coercion (negative threats and positive incentives) lowers internal cohesion only when, in response to external coercion, attempts to alter the internal distribution of power increase the distribution of benefits accrued to some members of the coalition while reducing the benefits enjoyed by others.

The Haitian De Facto Coalition

The Haitian junta was composed of a coalition that included the military high command, the business elite and the paramilitary group, named the Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti (FRAPH). This coalition was the resurrection of the old Duvalier regime that ruled Haiti for much of the country's political history. FRAPH merely became the new name for the old tonton macoute Ð the paramilitary organization that was the repressive arm of the Duvalier dictatorship. The de facto regime not only saw itself as a coalition before the conflict with the United States, it also saw itself as the legitimate heir to govern Haiti in the post-Duvalier era. The coalition's structure of political power was centralized within the military high command, which included three principal players: General Raoul Cedras, General Philippe Biamby, and police chief and FRAPH leader, Lt. Col. Michael Francois. The essential intrinsic attraction among members of the de facto coalition is that they all were ideologically opposed to Haiti's democratic process and to the prospect of its restoration. But beyond their ideological affinities, it was the instrumental attraction that defined the goals and preferences of the coalition members. The policies of the Aristide government posed the greatest threat to the instrumental goals of each member of the coalition.

Most members of the military high command cared about maintaining their political control over the army, protecting its budgets and securing wealth through narcotics trafficking.[31] Cedras maintained policy preferences in regard to specific issues that were independent from Francois, FRAPH and the army's rank and file. The bureaucratic experience of Cedras gained while serving at the military academy and at military headquarters developed in him policy preferences about the army that were largely "technocratic" in nature. He was largely considered to be a "military leader who genuinely wished to minimize his role in politics, professionalize the armed services, and develop a separate and competent civilian police force."[32] The reform of the Haitian army would strengthen the military's command and control structure, which would provide the army's high command with greater control over the enlisted men and thus avert the Haitian army's tradition of coups d'Žtat against their commanding officers.

The policies of the Aristide government threatened the power of the military high command. During his first year in office, Aristide attempted to exert control over the army in order to diminish its power and the potential threat that it posed for his democratic government. Attempts were made to reform the military personnel by dismissing Duvalierists members of the high command and replacing them with officers who were politically loyal to Aristide and supportive of democratization.[33] In his first year in office, the Aristide government also slashed the army's budget by US$4 million and proposed limiting the budget to just US$25 million for fiscal year 1992.[34] The government also established the anti-narcotic council, which developed a national policy against drug trafficking in Haiti and strengthened US-Haitian bilateral cooperative efforts in narcotic interdiction, seizures and the sharing of narcotic intelligence.[35]

In restructuring of the military personnel, the Aristide government attempted to dismantle the paramilitary. Since the existence of a paramilitary organization was incompatible with the process of democratization in Haiti, FRAPH, more than any member of the de facto coalition, stood to lose the most in the event of Aristide's return. During the crisis with the US government, FRAPH sought to bolster its power within the de facto coalition to enhance its capabilities to effectively repress the population and eliminate the pro-democracy opposition. Moreover, by consolidating its power within the coalition, FRAPH could challenge and displace the military's high command and usurp control of the army to coerce and discourage potential defections in order to maintain cohesion.

It was important to the Haitian business elite in the manufacturing, contracting and assembling sectors of the economy to keep wages low and thereby increase the process of capital accumulation while providing the necessary incentive to attract mobile foreign capital investment on which the Haitian private sector is heavily dependent. By proposing to raise the minimum wage, the Aristide government threatened a core interest of the Haitian business elite. The fear of the business elite was that Aristide's proposed minimum wage increases would encourage semi-skilled and skilled workers to demand higher wages for themselves. And given Haiti's high cost for non-labor factors of production such as port fees, electricity and telecommunications, Haitian companies balked at being forced to pay the additional costs in wages.[36]

External Coercion, Internal Cohesion and Resistance, 1991-93

Two days after the 30 September coup toppled President Aristide the Organization of American States (OAS) held an emergency meeting at its headquarters in Washington, DC. The US government strongly denounced the de facto military junta and pledged its support for Aristide's restoration. In addressing the member states of the OAS, US Secretary of State James Baker noted "this junta is illegal . . . [and] until Aristide's government is restored, this junta will be treated as a pariah, without friends, without support and without a future. This coup must not and will not succeed . . .. It is imperative that we agree for the sake of Haitian democracy and the cause of democracy throughout the hemisphere, to act collectively to defend the legitimate government of President Aristide."[37]

In June 1991, the OAS spoke of supporting "any measures deemed appropriate"[38] to deal with a coup in a member state. In October 1991, OAS foreign ministers mentioned reserving the right "to adopt all additional measures which may be necessary and appropriate"[39] to resolve the crisis in Haiti and reinstate Aristide. By 8 October 1991, the OAS and UN resolutions recommended the imposition of a voluntary trade and oil embargo against Haiti, which exempted humanitarian aid such as medicine, food and air travel. The Bush administration would later impose a separate embargo, that became effective by 15 November 1991.[40]

In reaction to the international pressure for Aristide's return the de facto coalition centralized and consolidated its power within Haiti's parliament and remained united in its defiance of the US and the international community's demands for the restoration of the democratic process. To forge a united opposition to block implementation of any agreement with the international community that could result in Aristide's return, it was necessary to purge and coerce those members within the Haitian parliament who were supportive or sympathetic to Aristide and the democratic process. This was the fate of pro-Aristide supporter Robert Malval, the Haitian prime minister appointed by the deposed president. The de facto regime's opposition to the Malval leadership in parliament was well-known among Haitian parliamentarians. With mounting international pressure for Aristide's return General Cedras publicly warned that, "he would no longer support the Prime Minister position . . .. [And] that he would no longer be responsible for protecting the [Malval government]."[41] Privately, however, plans were underway for the removal of Prime Minster Malval and other pro-Aristide ministers from the interim government and for the appointment of members of the de facto coalition to leadership positions in the Haitian parliament. US Defense intelligence noted:

General Raoul Cedras and Police Chief Lieutenant Colonel Michel Francois are planning a coup d'Žtat to remove Prime Minister Malval from his position during the week of October 18, 1993. Cedras and Francois plan to form a coalition government composed of military and civilian officials. These officials are to be hand picked from those Dominican Republic . . .. If Malval is removed the [parliament] will be composed of individuals who oppose President's Aristide's return to Haiti.[42]

The Junta's threats and intimidation ultimately forced the resignation of Malval in October 1993. The de facto coalition's coercion of parliament, moreover, was most evident during the first round of negotiations with the US and the OAS. By 5 October 1991, an OAS delegation was dispatched to Port-au-Prince to force the junta to relinquish power. The delegation met briefly with US Ambassador Alvin Adams, General Cedras, and members of the general staff, but was forced to return to Washington on 7 October after agitated enlisted soldiers arrived at the airport where the meeting was being held, seriously threatened the security of the OAS delegation and broke up the negotiations. Meanwhile, a group of 200 soldiers seized the legislative palace and demanded that the National Assembly members (who were waiting for the return of their leadership from the OAS negotiations) sign a petition that invoked Article 149 of the constitution, removing Aristide from office. The petition was ratified the day before the OAS returned to Washington, DC.[43]

The first major diplomatic agreement between the international community and the de facto junta for restoring democracy in Haiti came with the signing of the Washington Protocol on 23 February 1992. The agreement included, first, amnesty for the Haitian junta and other supporters of the 1991 coup; second, Aristide's respect for parliamentary legislation ratified after the coup (including Cedras' appointment as head of the military through 1994); third, the lifting of the embargo immediately after the ratification of Rene Theodore (an Aristide nominee) as the new prime minister; fourth, the inauguration of a government of national consensus between the Aristide's Lavalas party and the Haitian business elite who financed the coup; and fifth, an agreement to hold new presidential elections in 1995 without reclaiming the years lost from the five-year term as a result of coup.[44]

The de facto regime, however, utilized both political bribery and intimidation to block domestic ratification of the Washington Protocol. The de facto provisional government paid $50,000 to Haiti's de facto parliamentary deputies to vote against the Washington Protocol.[45] In addition, the provisional government also bought off segments of Haiti's armed forces to pressure Cedras into rejecting further negotiations with the US for Aristide's return. Members of Haiti's general staff routinely received an unofficial supplement to their paychecks each month. This money did not come from the standard pay account and was provided in cash and given only to members of the Haitian general staff. [46] US Defense intelligence reported:

The [de facto] government has been dispatching monthly stipends to soldiers of the Headquarters Defense Units (HDU) in a bid to buy their support for opposition to negotiations and for moving to elections. The bonuses are being paid monthly out of non-Defense ministry funds and are paid to both officers and enlisted personnel. Members of the [de facto] government have met a number of times with HDU officers and enlisted personnel in an effort to sway them to their cause.[47]

Police Chief and FRAPH leader Lt. Col. Michael Francois used FRAPH to intimidate parliamentarians to secure their opposition to the Washington Protocol. In recognizing the obstacle that Francois presented in blocking ratification of the Protocol a State Department memorandum noted:

We continue to encourage legislators and other folks here (well meaning and otherwise) to work for passage of the Protocol and Theodore. However, we see little reason to believe that our encouragement soon will bear fruit. Despite the squeeze on revenues, soaring dollar/gourde rates, unemployment, scandals and increasing hardships for all classes, after sorting through all the swirl of empty political maneuverings in Port-au-Prince Ð the bottom line here remains unchanged Ð the politicians are afraid to take any decision to resolve the crisis that might at the same time provoke Michael Francoise and his tugs [FRAPH] to retaliate against them. The politicians are too divided, too venal and too gutless to stare down Francois and his tugs. Neither do the legislators have any confidence that the international community (read the USG) is likely to resolve the Francoise problem for them (though they continue attempts to explain to us that Ôsomebody' must Ôdo something' about the [Francois] problem for there to be any prospect that the Protocol or Theodore will be ratified).[48]

The Washington Protocol was, therefore, rejected by the parliament and Haiti's Supreme Court of Justice voted the international agreement unconstitutional. Emboldened after successfully rejecting the Washington Protocol, the de facto government proposed an alternative agreement Ð the Villa d'Accueil accord Ð that called for a government of national consensus that did not mention Aristide's return or the restoration of the democratic process. The accord represented the increasing intransigence of the de facto regime vis-ˆ-vis the US and the international community.

The new Clinton administration intensified the economic embargo that was imposed against Haiti. The embargo, however, had little economic effect on the Haitian military leaders themselves. The tightening of sanctions by the Clinton administration devastated Haiti's urban poor but enriched Haiti's military generals.[49] In the northeastern section of Haiti, the generals mitigated the effects of the UN's oil and trade embargo by opening new roads in the districts of Liberete, Terrire Rouge and Ouanaminthe, which are close to the porous border of the Dominican Republic. Through this border Haiti's military leaders enriched themselves by creating a lucrative black market for hard to obtain fuel and contraband goods. At the principal border crossing at Ouanaminthe, the Haitian junta levied exorbitant taxes on all merchandise that came into Haiti.[50]

The international embargo, moreover, facilitated the conditions that encouraged Haiti's military leaders to secure economic rents through drug trafficking. The military junta was riddled with problems such as drug dealing and contraband activities. Under Cedras, the use of crack cocaine in the navy and other branches of the military had reached serious proportions.[51] US Defense intelligence reported that the Haitian coup leaders who deposed Aristide were routinely involved with drug trafficking in the southern districts of Les Cayes and the southeastern districts of Meyer/Geocoord and Jacmel. These Haitian officers were paid by Colombian narcotics traffickers to protect their cocaine shipments on route to the US and Europe. A US Defense intelligence report entitled, "FDH General Staff Officer Reportedly involved in Narcotic Trafficking" noted:

A Colombian narcotrafficker named . . . gave [General] five kilos of cocaine on or about the 15 Mar 1991 in exchange for . . . protecting a drug load scheduled to arrive by air in Les Cayes the week of 25-29 Mar 91. [General] has dealt with narcotraffikers before. [General] controls a runway outside of Les Cayes. The load expected is approximately 600 Kilos and will be arriving from Columbia . . .. The 600 Kilos would be transferred to a "Stash House" until transport to the US or Europe can be arranged.[52]

The Haitian junta's drug related activities were also extensive in the southeastern districts of Haiti. US Defense intelligence again reported: "That once a week, around Wednesday or Thursday about 2100, a low flying plane is heard near the shore line in the vicinity of Meyer/Geocoord, to the east of Jacmel. Locals, who have been observing this for some time now, report that military personnel go out at night to receive the drug bundles."[53]

The black market and drug smuggling activities of the Haitian generals provided these members of the de facto coalition with financial immunity against the tightened sanctions of the Clinton administration. To bolster the sanctions that were already in place the Clinton administration ordered a naval blockade of Haiti. The additional external pressure on Haiti brought Cedras back to negotiations that led to the Governors Island Accord. Under the US/UN brokered Governors Island Accord signed in July 1993, Aristide made concessions to the Haitian junta similar to the concessions granted under the Washington Protocol. The agreement included Aristide's appointment of a new prime minister; the lifting of the UN sanctions; the sharing of power between Aristide's Lavalas party and the Haitian business elite who financed the coup; parliamentary reforms of the Haitian army and police under the supervision of the UN; the proclamation of amnesty by Aristide for those involved in the coup; and the voluntary retirement of Cedras and other members of the Haitian high command on the return of Aristide which was scheduled for 30 October 1993.[54]

The Clinton administration in its eagerness to claim diplomatic victory for the apparent resolution of the crisis credited the international embargo with forcing the de facto military regime to come to the bargaining table and accept the restoration of the democratic process in Haiti.[55] The de facto coalition would again prove resilient in its ability to resist this latest attempt to return Aristide to power in Haiti. To implement the Governors Island Accord, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) passed resolution 867 authorizing the establishment and immediate dispatch of the United Nations Mission in Haiti (UNMIH). The UNMIH comprised approximately 700 military and police personnel with the US and Canada largely providing the military component of the mission.[56] As specified by the agreement, the UNHIM, over a period of six months, would help in the modernization of the Haitian military, establish a new police force and oversee Aristide's return. When the ship, the USS Harlan County, carrying the UNHIM military contingent arrived in Port-au-Prince on 11 October 1993, FRAPH prevented the ship from casting anchor. FRAPH violently attacked foreign diplomats and local and international press personnel assembled to meet the troops at the harbor. The Harlan County was ordered to return to Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, and future attempts to deploy UNHIM troops to Haiti were blocked by the Pentagon and Republicans in the Congress who opposed efforts to restore Aristide to power.[57] In commenting on the de facto regime's resistance to Aristide's return and willingness to use force against potential defectors from the coalition, the US Defense intelligence noted:

All signs point to Lt. Francois' determination to force a showdown with Aristide. Francois has reportedly stockpiled ammunition during the last few months, and his increasing reliance on the attaches [FRAPH] reveals a willingness to use force to achieve his aims. It is highly likely that the return of Aristide will be greeted by outbreaks of violence orchestrated by [FRAPH]. The violence will be directed against leading figures in the interim government and any group supportive of the ousted President's return.[58]

The Fragmentation of the De Facto Coalition, October 1993-94

Between September 1991 to October 1993, the de facto coalition remained cohesive in its defiance of the international community's demand for the return of Aristide and the restoration of democracy. US external coercion did not induce any changes in the internal distribution of power within the de facto coalition and the coalition remained cohesive in its efforts in rejecting both the Washington Protocol and the Governors Island Accord. However, as the crisis with the US government continued, coupled with the implementation of stiffer external sanctions, various members of the de facto coalition were affected differently. The intensification of external coercion increased the power and capabilities of FRAPH relative to the other members of the de facto coalition. These changes in the internal distribution of power within the coalition reduced the distribution of benefits for the business elite and threatened to displace the military high command as a dominant player within the army and the coalition. Between November 1993 and September 1994, as the power and benefits of these members began to diminish, they increasingly preferred a strategy of defection as opposed to continued resistance of US pressure.

The Haitian Business Elite

While the business elite was not affected by the voluntary sanctions of the Bush administration, stiffer sanctions enforced by the Clinton administration eroded their financial security and ultimately reduced the benefits of pursuing a strategy of remaining within the coalition. Like most developing countries, the economic viability of the Haitian business elite in the financial, industrial and export sectors of the Haitian economy are largely dependent on the capital flows generated by foreign subsidiaries that operate in Haiti. Such dependence is established through joint venture arrangements with foreign capital, and through a range of financial services that the local business elite provides for their foreign partners and clients.[59] These include contracting, outsourcing and banking services. For example, Industries Nationales Reunies S.A. (INR), owned by Haitian businessman, Andre Apaid, provided contracting services to American corporations. The most successful division of INR, Alpha Electronics, "assembles electronic products for Sperry/Unisys, IBM, Remington and Honeywell."[60]

The tighter sanctions enforced by the Clinton administration prevented American companies from exporting component parts to Haitian subsidiaries and contracting companies in the manufacture and export sectors. The administration also denied import licenses to US subsidiaries in Haiti. As a result of these tightened sanctions, employment in Haiti's manufacturing sector, which was estimated at 150,000 in the mid-1980s, dropped to approximately 10,000 by late 1993. In addition, American subsidiaries in the banking, transportation, communications, electronics and manufacturing sectors began divesting from Haiti.[61] Given their dependence on foreign capital, Haiti's private sector began to suffer as foreign capital took flight.

By late 1993, stiffer sanctions disrupted the economic payoff structure of the business elite and provided them with the necessary incentives to defect and accept the diplomatic carrots and concessions that they had rejected earlier under the Washington Protocol and Governors Island Accord. The business elite began to reconsider its alliance with the de facto regime. The US Department of Defense noted that "although the financial and political elite are still sheltered, their protection is starting to wear thin and they are the loudest in their complaints"[62] against the de facto military junta. One Haitian businessman who supplied food to the military noted:

I frankly was quite happy with the coup . . . I do not like Aristide, and thought maybe Cedras would be another Pinochet. But he is not. He is a failure, and now we have to accept the fact that Aristide is president. All we can do is hope the international community keeps him from his own worst instincts.[63]

Another businessman stated:

It is not the traditional bourgeoisie that are actively opposing Aristide now, it is the young guys [FRAPH] who made a lot of money after the coup, who have a certain lifestyle and are not about to give it up. They have no money outside the country, nothing to fall back on, so it is all or nothing.[64]One businessman noted that he was now "absolutely sure that Francois controls everything. He is the center of the Mafia. We did not understand this at first. And Cedras is a willing partner."[65]

The Military High Command

Although the military high command enjoyed economic rents even under a tightened international embargo, the sanctions indirectly altered the internal structure of the junta's political power. The enforcement of stiffer sanctions created a black market for oil and contraband goods that was controlled by the military high command. Economic sanctions generated windfall profits for the high command which they used to finance the expansion of FRAPH in order to repress the Haitian democratic sector and terrorize the general population.[66] US Defense intelligence reported that by the end of 1993, FRAPH expanded to over 10,000 members and established local chapters in every major city in Haiti. By December 1993, the power of the paramilitary was firmly entrenched in Port Au Prince, Cap Haitien, Gonaives, Port De Paix, Jacmel, Jeremie, St. Marc, Miragoane, Petit Goave and Mont Rouis.[67] US Defense intelligence reported:

FRAPH will continue to expand as long as this confrontation . . . between the international community and Haiti exists. The longer the confrontation lasts and the greater the sanctions, the more Haitian society will become polarized and nationalistic. This will provide an incredible fertile terrain for FRAPH recruiters. Should the crisis be resolved with the lifting of the embargo and a return to constitutional order, FRAPH will lose a lot of its adherents. Eventually, FRAPH would become insignificant because its 'raison d'être' would no longer exist.[68]

Sanctions allowed the military high command to bankroll the development and mobilization of a "beast" that they could not control. Given FRAPH's expansion and its autonomy from the military command structure the paramilitary organization operated beyond the control of the military high command. FRAPH became a major threat to the high command's source of power. The high command's dominant position of power within the de facto regime was ensured by its ability to control and maintain the integrity of the military's command structure. FRAPH, however, threatened the high command's control over the army by undermining the integrity of the military's command structure and by its attempts to displace the local power and authority of the military throughout much of Haiti's rural provinces.

The extensive growth and activities of FRAPH challenged the authority of the military's departmental commanders. Haitian army commanders feared that the paramilitary organization would displace the military as the focus of local power. Clashes between members of FRAPH and members of the military hierarchy escalated. Some of these clashes involved army commanders themselves. In most cases these clashes were attributed to FRAPH's attempt to usurp the power and prerogative of the local military in their desire to intimidate the local population.[69] There were also armed confrontations between FRAPH and military personnel belonging to the Headquarters Defense Unit (HDU), formerly the Presidential Guard.[70]

The command structure within the Haitian military continued to be undermined as a result of the increased confrontations between FRAPH and the provincial military leadership. Resenting the fact that the paramilitary group now threatened their authority, local military commanders began to assert themselves and take actions independent of the directives of the high command. This tension between local commanders and the high command resulted in some institutional power shift from the capital to the Haitian provinces.[71] With the erosion of the command structure, the high command increasingly became isolated politically from the military's enlisted men and they grew suspicious of the motives of Cedras during the course of his negotiations with Mr. Caputo, the UN/OAS special envoy to Haiti. The suspicion that Cedras had negotiated a secret deal for himself and the other members of the high command that may have permitted the return of Aristide, preempted a mutiny by enlisted men against their commanding officers at Camp D'Application.[72]Concerned about the growing fragmentation of the military's command structure, the US State Department noted that "a rift in the army . . . is precisely what Aristide is angling for Ð bringing down Cedras by his own troops and in the process opening the route for a people's revolution."[73] By the beginning of 1994, it became apparent that the Haitian high command had lost the base of its support among its own forces. According to US Defense intelligence:

Cedras, Biamby and their inner circle of civilian advisers are becoming increasingly isolated politically because they may have lost their power base. Without Lt-Col Francois' unconditional support, with questionable support from the Headquarters Defense Unit (Presidential Guard) or the Heavy Weapons Company, and FRAPH more strategically aligned with Lt-Col Francois, Cedras and Biamby can no longer project the image of strength they once did.[74]

The political vulnerability of Cedras, the erosion of the high command's power within the military and the attempt by FRAPH to displace the local power of military commanders, were factors that radically eroded the power that Cedras and other members of the high command enjoyed within the de facto coalition. In light of the high command's diminished power within the military vis-ˆ-vis FRAPH, the diplomatic concessions that the US had previously offered the generals now appeared attractive and the military high command began to forge a diplomatic strategy that would gradually accommodate the US demands for Aristide's return.

In the face of the intractable reality that the international community intended to restore Aristide combined with the domestic reality of their diminished power, key members of the de facto coalition with the exception of FRAPH began to restructure their bargaining strategy vis-ˆ-vis the US. The de facto prime minister began hosting negotiations with private sector representatives in the National Palace. Private meetings were held at the home of General Cedras with a group of 50 Citibank clients, 50-60 business sector representatives of the Haitian Chamber of Commerce and Board members of Haiti's Sogebank, a powerful private sector bank. Most of these discussions focused on the private sector's fears that Aristide would retaliate and unleash mobs against his political enemies. Those who financed the coup against Aristide now met in secret to tally the cost of his return.[75]

One outcome of these meetings was the signing of the United Nations Accord that suspended the worldwide fuel embargo against Haiti in exchange for further negotiations for Aristide's return. In addition, there were talks with the United Nations to secure approval to use Haiti's Bowen air field to land an estimated 560-man United Nations force to help implement the democratic transition. While the Haitian bourgeoisie applauded these actions, Michael Francois and FRAPH opposed them. According to State Department reports:

Francois' behavior has changed to the point that he is reluctant to follow the orders and instructions from the senior military officers in Haiti . . . [And in terms of the UN request to land UN forces at Bowen airfield] Francoise feel betrayed and may possibly attempt to foment internal resistance . . .. Amassing up to 10,000 members of the civilian police attachŽ [FRAPH] and auxiliary forces [to block the initiative].[76]

Michael Francois and FRAPH

The conflict between the Haitian high command and Francois also centered on the diplomatic concessions that were offered by the US government. These included the separation of the police and the army, the professionalization and reform of the military, the reorganization of the police, and the offer of amnesty and early retirement for members of the general staff. Since FRAPH was Francois' principal source of power within the de facto coalition, any effort on the part of the generals to reform the police and army would eliminate the justification for maintaining the paramilitary group and hence terminate the high command's major source of internal threat. While these diplomatic concessions were becoming increasingly appealing to Cedras they were unacceptable to Francois. Moreover, Francois opposed the idea of being forced into early retirement Ð a central pre-condition for Aristide's return. Francois became convinced that both Cedras and Biamby were attempting to cut a deal with the US that would exclude him, FRAPH and the military's enlisted men who remained opposed to Aristide's return. In light of the Haitian high command's weakened political position within the de facto coalition and consequently its changed bargaining strategy toward the US government for the return of Aristide, the US Defense intelligence noted:

Lt.-Colonel Michael Francois admitted that the he believes that the Ôdivorce' between him and the Fad'H High Command is final . . . Francois opined that both he and his 1981 peers, [military academy Graduating Class of 1981] unlike the class of 1973 officers like Cedras and Biamby, have many years left in the service and should at least hedge their chances for continued active duty service. Francois stated that he followed Cedras and Biamby blindly these last two years, but now feels not only abandoned but betrayed by Biamby especially, who is increasingly trying to undermine Francois for the sake of his own political ambitions [vis-ˆ-vis the US]. Francois views himself as the guarantor of his comrade's professional welfare . . . [And] under no condition would he accept to resign from the military . . . Michael Francois has started charting his own course in the past few weeks separate from the machinations of Generals Cedras and Biamby.[77]

The diplomatic concessions that the US government offered Haiti's high command largely isolated FRAPH; and given the growth in its size and power the best strategy for the paramilitary group vis-ˆ-vis the US was continued resistance via a possible coup d'Žtat against the high command who was poised to defect. By December 1993, anti-Aristide hard-liners within the de facto coalition that were allied with FRAPH, known as "Cedras Kitchen Cabinet" sought to remove Cedras from power when the situation presented itself. US Defense intelligence reported that:

The extreme right within the military may set aside Cedras and help form a new government. This extreme right element within the military is identified as Cedras ÔKitchen Cabinet', made up of Col. Dorelien, Ltc Michel Francois, TI Parris, Romeo Aloun and probably Col. Prud Homme. They believe that General Cedras has become an obstacle to their interests. Now with the support of FRAPH, they don't need him any longer to maintain control over the army and the population.[78]

The increasingly vulnerable position of the high command within the army prompted the possibility that Francois would oust Cedras. In monitoring the changing dynamics within the de facto military coalition the US State Department noted:

It seems increasingly likely to us, that barring effective action against him by Cedras, that eventually Francois, or a surrogate, will make his play for power. Whether he will limit initial actions to dissolving the Parliament and/or replacing Cedras also remains to be seen. He may judge it beneficial to leave Nerette/Honorat (who also seem favorable to the idea of getting rid of Parliament) in place Ð at least until he can assess the international community reaction.[79]

Given the continued erosion of his own position within the military and the internal threat that FRAPH now represented, by September 1994, after six months of diplomatic deadlock with the international community, Cedras re-opened negotiations with the US government via Jimmy Carter. President Clinton dispatched the Carter mission to Haiti that ultimately produced the Port Au Prince Agreement.

The Decision to Comply

On 18 September 1994, with a US-led invasion of Haiti imminent, former US president Jimmy Carter signed the Port Au Prince Agreement with Haiti's de facto President Emile Jonassaint that provided for General Cedras and the military regime he headed to resign from power by 15 October. The Port Au Prince Agreement also provided for the implementation of UN Security Council Resolutions which authorized the US-led coalition to use all "necessary means" to remove the military junta from power. On 19 September, the US-led multinational force entered Haiti peacefully with the goal of ensuring a safe and secure environment for the transition back to constitutional government. With Aristide's approval, a special session of parliament was convened on 28 September to vote on legislation that immediately granted amnesty to the military high command and the creation of a national police force Ð one that was separate from the army and under the supervision of the Ministry of Justice. After three years in exile President Aristide returned to Haiti on 15 October 1994.

In explaining the successful diplomatic outcome of the Haitian crisis many in the US foreign policy establishment emphasize exclusively the external coercive elements of US diplomacy. They assert that the de facto junta's decision to comply on 18 September 1994 was the direct result of Clinton's 13 September ultimatum and the last minute mission of Carter, Powell and Nunn who convinced the junta that a military invasion would follow if talks for Aristide's return failed. Robert Pastor, personal advisor to the Carter mission to the junta, maintains that it was the credibility of the military threat that proved essential in reaching an agreement with the Haitian junta. However, Pastor also noted that once Cedras had learned that the invasion was already in progress he refused to sign the agreement or have further negotiations.[80] Given this reading, it is not at all clear that the threat of invasion was the sole crucial factor in the junta's decision to comply with US demands. If Cedras was willing to sign the agreement when he did not know that the American invasion was underway why then was he willing to end negotiations when he did know that American troops were headed for Haiti? It appears that the threat of US military invasion was not the only factor that produced compliance and may have even encouraged resistance on the part of the Haitian junta had it not been for the domestic fragmentation of the de facto coalition.

The conventional explanation for the success of American diplomacy in restoring democracy in Haiti then is only partially correct. Missing from the account is an analysis of the importance of domestic intervening variables within Haiti that processed the external coercive pressures and ultimately produced the successful diplomatic outcome. This analysis of the junta's decision to comply is multiplicative. Essentially, in the absence of the internal fragmentation of the de facto coalition, the increasing political vulnerability and weakness of Cedras within the Haitian military, the Carter mission would not have been successful. US coercive diplomatic pressure and the threat to intervene were necessary but not sufficient to produce the Port Au Prince Agreement. Clinton's ultimatum and the threat of military intervention was more effective in September 1994 when the de facto coalition collapsed as opposed to 1993 when the coalition was cohesive and able to resist the US military force that was sent to implement the Governors Island Accord. The Haitian junta's decision to comply must be placed within the context of the disintegration of the de facto coalition that preceded both the military threat and the Carter mission. In emphasizing the importance of the domestic vulnerability of Cedras in the junta's decision to comply, the UN reported that:

Cedras' position within the Haitian military had deteriorated to such a degree that he had no choice but to resign and go into exile. His lack of field experience and contact with his troops reduced the support he received from the Forces Armees d'Haiti (FAD'H) . . . General Cedras' authority had also been eroded by the military's lack of professionalism and cohesion.[81]

To argue that the junta's decision to comply with US demands for Aristide's return was in part a function of the disintegration of the de facto coalition may seem to suggest that the de facto junta was never fully unified from the outset of the conflict with the US government. Moreover, FRAPH's desire to topple Cedras could be interpreted as a consistent historical pattern of Haitian politics where coups have been the means of circulating elites in and out of power. In fact, the coup d'Žtat on 30 September 1991 that ousted Aristide was merely a continuation of a pattern in which coups were the normal mechanism for the transfer of political power in Haiti. For example, on 17 January 1988, Leslie Manigat was elected president and by 19 June 1988 he was ousted in a coup led by General Namphy. By 17 September 1988, General Namphy was ousted in a coup led by Lt. Gen. Prosper Avril. By 2 April 1989, General Avril survived a coup attempt by high-ranking generals but stepped down on 10 March 1990.

Given this history, how unified was the de facto coalition that deposed Aristide? And was the behavior of FRAPH consistent with the historical logic of Haitian politics? It has been argued that the unity among members of the de facto coalition centered on their intrinsic and instrumental preferences. Intrinsic in the sense that they were all ideologically opposed to Haiti's democratic experiment and to the prospect of its resumption. The unity of the de facto coalition was also based on instrumental preferences in the sense that the policies of the Aristide government threatened the political and economic power of the military and business elite. Evidence of this unity was shown in the de facto coalition's resolute rejection of the US government's efforts to return Aristide via the Washington Protocol and the Governors Island Accord. Moreover, it is argued that the behavior of FRAPH is not consistent with the historical pattern of Haitian politics. The demise of regimes throughout much of Haiti's political history was linked directly to the dynamics of Haiti's internal politics.[82]82 The expansion and mobilization of FRAPH and the conflict between Cedras and Francois were induced by external political and economic coercion. The eventual fragmentation of the de facto coalition was the direct consequence of the ways in which external coercion altered the distribution of political power within the coalition by reducing the power of the military high command while increasing the power and influence of FRAPH.

CONCLUSION

This analysis has attempted to answer the question: under what conditions is Type C coercive diplomacy likely to succeed? By integrating the literatures of coercive diplomacy and conflict and cohesion, this analysis has sought to advance five theoretical propositions that were tested by the case study analysis of US coercive diplomatic efforts in restoring democracy in Haiti.

These theoretical propositions were confirmed by the finding from the case study which showed that the success of Type C coercive diplomacy is a function of the time duration over which external coercion is exercised. As the time duration of external coercion increases stress among the target's coalition members is likely to increase. As a consequence of externally induced stress, coalition members are more likely to renegotiate the internal distribution of power within the coalition whereby some members will attempt to increase their political power at the expense of diminishing the power of others. Under these conditions, coalition members are more likely to adopt competitive bargaining strategies to resolve the conflict with the external power. Coalition members whose internal political power has diminished are more likely to defect and bargain for an optimal accommodation with the external power. On the other hand, coalition members whose political power has increased have a greater incentive to adopt bargaining solutions that will resist the demands of the external power. Therefore, given time and stress that results from conflict, an external power can encourage the target's coalition members to pursue multiple and competitive bargaining solutions to the crisis and effectively facilitate a process in which domestic coalitions fragment, members defect and compliance becomes possible.

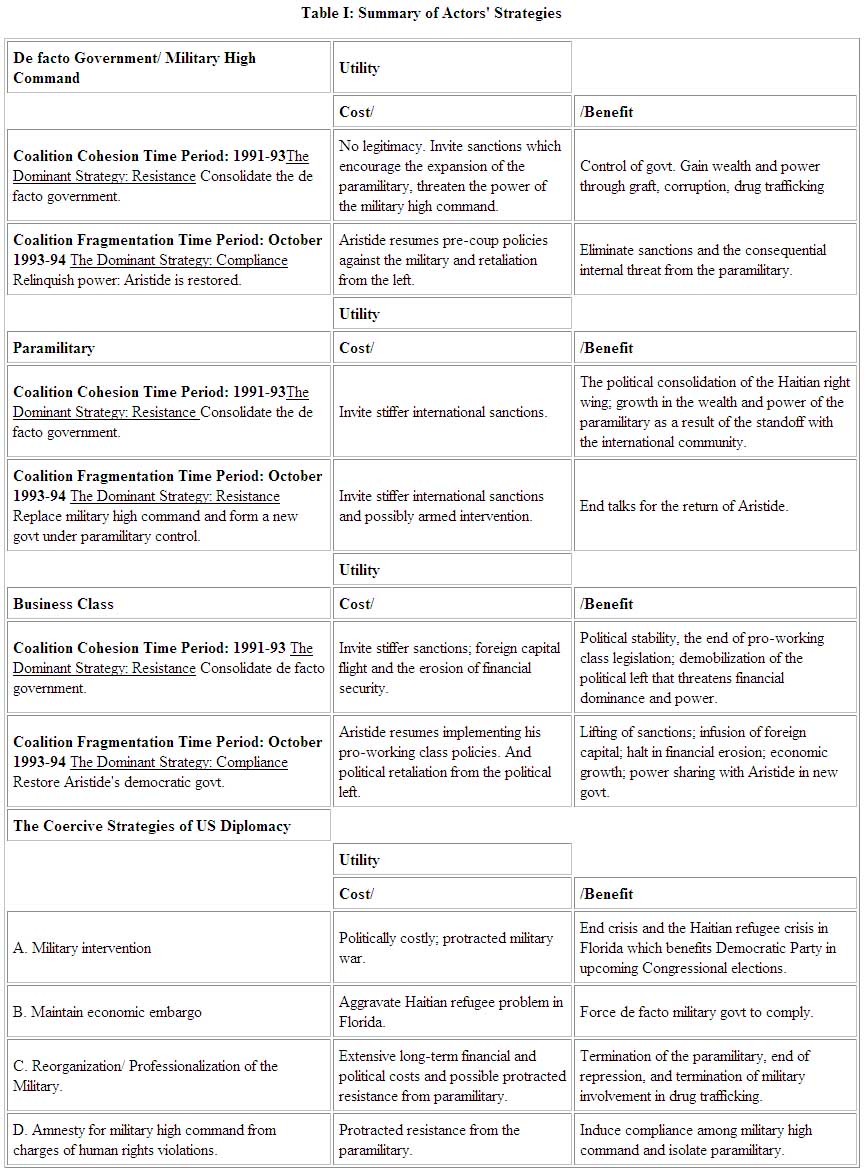

The success of US coercive diplomacy toward Haiti underscores the importance of time in assessing the impact of external coercion. Stress among members of the de facto coalition increased as the time duration of the conflict with the US increased. In the first two years of the conflict, the de facto coalition remained cohesive and successfully resisted US coercive pressures. During this time period, de facto coalition members sought to consolidate their power within the de facto regime and adopted a similar strategy in response to US external pressures (see summary of actors' strategies in the Appendix). With increases in US external coercion, however, stress among coalition members increased as the crisis prolonged. Indicative of this stress was the attempt by FRAPH to alter the distribution of power within the coalition. FRAPH's power within the regime increased while it diminished the power and benefits for the military high command and the business elite. As a result, by late 1993, the de facto coalition began to unravel as coalition members adopted competitive bargaining solutions in response to US external pressure. The military high command and business elite pursued a strategy of defection and sought an accommodation with the US for Aristide's return. Since FRAPH would be terminated with the return of democratic and constitutional rule, the paramilitary organization continued to pursue a strategy of resistance against US pressure by attempting to eliminate the military high command and usurp control of the army. The Haitian case shows that the duration of time, stress among coalition members, the changes in the distribution of power within the coalition and the adoption of multiple and competing bargaining solutions to resolve the external conflict were the necessary intervening domestic variables that interacted with each other as well as with US external coercion to produce compliance.

The findings from this analysis have important policy implications for the resolution of current and future international conflict via coercive diplomacy. In light of the recent bombing of Iraq and US policy discussions that are now centered on removing the Iraqi leadership from power, this analysis is of particular importance in attempting to realize this Type C goal. American policy options that stress air strikes and the armed mobilization of Iraqi opposition groups against the regime could solidify the regime and end in failure. The policy implications from the Haitian case suggests that policy makers must deploy coercive measures to affect specific coalition members within the Iraqi regime, with the objective of fragmenting the coalition. To achieve Iraqi compliance under Type C diplomatic conditions, American policy makers must refine current coercive measures so that they can alter the target's internal distribution of power, erode cohesion and thereby encourage defection. To accomplish this objective, American policy makers must acquire what Alexander George calls "generic knowledge" of the individual interests of coalition members within the Iraqi government and be willing to employ greater diplomatic skill in structuring the mix of coercive measures aimed at disrupting the benefits that each coalition member enjoys.

Appendix

Table 1: Summary of Actors' Strategies

Endnotes

The author wishes to thank Professor Ernest J. Yanarella for his valuable comments and suggestions to earlier versions of this article.

1. Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War (New York: Penguin, 1972), pp. 402, 406-07.

Return to article

2. William Graham Summer, Folkways: A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores, And Morals (Boston, MA: Gin and Company, 1906), p. 12.

Return to article

3. Alexander L. George and William E. Simmons, eds., The Limits of Coercive Diplomacy (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1994), pp.8-9.

Return to article

4. Bruce W. Jentleson, "The Reagan Administration Versus Nicaragua: The Limits of " Type C" Coercive Diplomacy," in George and Simmons, eds., The Limits of Coercive Diplomacy, pp.175-76.

Return to article

5. Alex Dupuy, Haiti in the New World Order: The Limits of the Democratic Revolution (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1997), pp. 139-46.

Return to article

6. George and Simmons, eds., The Limits of Coercive Diplomacy, pp.8-9.

Return to article

7. Paul Lauren Gordon, "Theories of Bargaining with Threats of Force: Deterrence and Coercive Diplomacy," in Paul Gordon Lauren, ed., Diplomacy: New Approaches in History, Theory, and Policy (New York: The Free Press, 1979), 192-93.

Return to article

8. Alexander L. George, Bridging the Gap, p. 87. For an analysis and discussion of how misperception and miscalculation contributed in the failure to coerce Saddam Hussein, see Jerrold M. Post, "Saddam Hussein of Iraq: A Political Psychology Profile," Political Psychology 12, no. 2 (1991), pp. 279-89; Jerrold M. Post, "Middle East Forum - Revisited," Political Psychology 12, no. 4 (1991), pp. 723-25; for an analysis of the sources of misperception, see Richard Ned Lebow, Between Peace and War: The Nature of International Crisis (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981), pp. 148-228.

Return to article

9. Alexander George, "Theory and Practice," p. 15.

Return to article

10. Jentleson, "The Reagan Administration Versus Nicaragua," p. 189.

Return to article

11. Mark Danner, "The Fall of the Prophet," New York Review of Books, 40, no. 20 (December 1993), pp.44-53; Christopher Marquis, "CIA Analyst Discounted Haiti Terror," Miami Herald, 18 December 1993, pp. 7-8. See also Kim Ives, "The Unmasking of A President," in Deidre McFadyen and Piere LaRemee, eds., Haiti: Dangerous Crossroads (NACLA, South End Press, 1995), p. 85.

Return to article

12. Jackie Calmes and Clara Ann Robinson, "Clinton is Pressured to Do Something in Haiti, But Poll Says the Public Isn't Overly Concerned," Wall Street Journal, 6 May 1994, p. A16; New York Times/CBS News Poll, "Views of the Haiti Operation," New York Times, 21 September 1994, p. A8 (N); Steven Kull and Clay Ramsey, "Public Support for US Action in Haiti Appears Malleable," The Christian Science Monitor, 1 August 1994, p. 19.

Return to article

13. George, Bridging the Gap, p. 80.

Return to article

14. Anthony Lewis, "Reward for a Job Well Done," New York Times, 7 October 1994, p. A5.

Return to article

15. Department of Defense, "USAITAC Counterintelligence Periodic Summary," Declassified Memorandum (United States Department of Defense, 15 October 1993), p. 4991.

Return to article

16. L. Coser, The Functions of Social Conflict (New York: Free Press, 1956); Robin M. Williams, The Reduction of Intergroup Tensions (New York: Social Science Research Council, 1947), p. 50; K. F. Otterbein, "Internal War: A cross-cultural study," American Anthropologist 70, no.2 (April 1968), pp. 277-89.

Return to article

17. E.C. Fritz, "Disaster," in Robert K. Merton and Robert A. Nisbet, eds., Contemporary Social Problems: An Introduction to the Sociology of Deviant Behavior and Social Disorganization (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961).

Return to article

18. K.F. Otterbein, "Cross-cultural studies of armed combat," Buffalo Studies 4, no. 1 (April 1968), pp. 91-109.

Return to article

19. K.F. Otterbein, "An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth: A cross-culture study of feuding," American Anthropologist 67, no. 6, part 1 (December 1965), pp.1470-82.

Return to article

20. Robert L. Hamblin, "Group integration during a crisis," Human Relations 11, no. 1 (February 1958), pp.67-76.

Return to article

21. L.E. Quarantelli, "The nature and conditions of panic," American Journal of Sociology 60, no. 3 (November 1954), pp. 267-75; E.R. Foreman, "Resignation as a collective behavior response," American Journal of Sociology 69, no. 3 (November 1963), pp. 285-90; A.C. Hammerschlag and B.M. Astrachan, "The Kennedy Airport snow-in: an inquiry into intergroup phenomena," Psychiatry 34, no. 3 (August 1971), pp. 301-08.

Return to article

22. M. Mulder and A. Stemerding, "Threat, attraction to group, and need for strong leadership: a laboratory experiment in a natural setting," Human Relations 16, no. 4 (November 1963), pp. 317-34.

Return to article

23. Muzafer Sherif, In Common Predicament: Social Psychology of Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1966), p. 81.

Return to article

24. K. Lang and G.E. Kurt, "Collective responses to the threat of disaster" in George H. Grossner, Henry Wechsler and Milton Greeblatt, eds., The Threat of Impending Disaster: Contributions to the Psychology of Stress (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1964), p. 58.

Return to article

25. F.C. Fink, "Some Conceptual Difficulties in the Theory of Social Conflict," Journal of Conflict Resolution 12, no. 4 (December 1968), pp. 285-90; S.M. Schmidt and T.A. Kochan, "Conflict: Toward Conceptual Clarity," Administrative Science Quarterly 17, no. 3 (September 1972), pp. 359-70.

Return to article

26. An additional problem with the social psychology literature is that the central unit of analysis is the individual. This presents a problem in the attempt to apply the intervening variables that are drawn from this literature to analyze coalitions, which is the central focus of this article. This problem, however, is manageable. One can argue that by the logic of triangulation, when combined with studies in Sociology and Anthropology, a "stream of evidence" emerges that support the central proposition of the theory of conflict and cohesion and centrality of the intervening variables that are adopted from the social psychology literature. Therefore, it is possible to apply the variables from the social psychology literature to analyze the behavior of groups and coalitions. For further discussion of these issues, see D.T. Campbell, "Definitional versus multiple operationalism," Et A1 2, no. 1 (Summer 1969), pp. 14-17.

Return to article

27. A. Pepitone, "The role of danger in affiliation and attraction," Acta Psychologica 18, no. 1 (1961), pp. 1-10; V.N. Dadrian, "On the dual role of social conflict . an appraisal of Coser's theory," International Journal of Group Tensions 1, no. 4 (October-December 1971), pp. 371-77.

Return to article

28. Dorwin Cartwright, "The Nature of Group Cohesiveness," in Dorwin Cartwright and Alvin Zander, eds., Group Dynamics: Research and Theory (New York: Harper & Row, 1968), pp. 91-124; Warren O. Hagstrom and Hanan C. Selvin, "Two Dimensions of Cohesiveness in Small Groups," Sociometry 28, no. 1 (March 1965), pp. 30-43; J. Rex Enoch and S. Dale McLemore, "On the Meaning of Group Cohesion," Southwestern Social Science Quarterly 48, no. 2 (September 1967), pp. 174-82; Bernice Eisman, "Some Operational Measures of Cohesiveness and their Interrelations," Human Relations 12, no. 2, pp.183-89.

Return to article

29. Leon Festinger, "Informal Social Communication," in Cartwright and Zander, eds., Group Dynamics, p. 185.

Return to article

30. J. Rex Enoch and S. Dale McLemore, "On the Meaning of Group Cohesion," pp. 179-80.

Return to article