by

A. Walter Dorn and Jonathan Matloff

We owe it to the [UN] Organization, to those who lived through the horrors of the genocide, and especially to those who perished in it, to make sure that the tragic sequence of events and the inadequate United Nations response to it are scrutinized, analysed and reassessed, and every effort made to prevent a possible recurrence.

Kofi Annan, UN Secretary-General, 12 June 1996[1]

INTRODUCTION

On 6 April 1994, the most intense genocide since World War II was unleashed upon an unprepared world. Starting in Kigali, the Rwanda capital, the systematic slaughter of an ethnic group, the Tutsis, spread with a ferocity that even its sinister organizers could not have hoped for. In 100 days it consigned about 800,000 Rwandans to their deaths. The perpetrators, high within government circles, had made meticulous plans. A radio station under their control, Radio Mille Collines,[2] had been whipping up anti-Tutsi hysteria for months. Secret arms caches were kept ready for use by government soldiers and the party militia, the core cadre of which had been trained in the tactics of slaughter. Lists of Tutsis and their Hutu sympathizers had been compiled for targeting. Only a trigger was needed. It was provided in a fashion as unexpected as the genocide itself: the killing of the Rwandan government leader under whom the genocidaires (genocidists) had worked. As the wave of death spread across the country, the international community stood by in a stupor, and even sought to avoid its moral and legal responsibilities to mitigate this immense human and humanitarian tragedy.

The key international leaders have admitted that they should have acted. In a news conference on 4 May 1998, Secretary-General Kofi Annan, who was under secretary-general for peacekeeping at the time of the genocide, said: "I agree with [UNAMIR Force Commander] General Dallaire when he says, 'If I had had one reinforced brigade - 5,000 men - well trained and well equipped, I could have saved thousands of lives'."[3] On a visit to Africa in March 1998, President Clinton admitted that the world "did not act quickly enough" and that "we did not immediately call these crimes by their rightful name - genocide."[4] Secretary of State Albright stated that "we - the international community - should have been more active in the early stages of the atrocities in Rwanda."[5] Many believe that the international community could have acted even earlier, to prevent the genocide before it started, or to nip it in the bud in the first few days. There are, however, no detailed studies on the precise measures that could have been undertaken by the international community and the international organization that bears the most responsibility for maintaining international peace and security, the United Nations.[6]

What was necessary for prevention? Three things were needed: an intelligence capability (for early warning and planning), preventive measures (i.e., a capability for intervention) and the political will to make use of these two. Tragically, it was only the latter that was fundamentally lacking, since the first two were present in a nascent state. Though inadequate, they could have been further developed given more political will. There was a UN peacekeeping force already deployed in the country, with a mandate to contribute to Rwandan security. Its commander had received secret intelligence about a genocide plot which he deemed convincing enough to begin planning for an active intervention. He was, however, restrained by his superiors at UN Headquarters in New York, who felt strongly the lack of commitment from the major powers in the Security Council, especially the United States. The atmosphere in New York, reflecting that in Washington, greatly dimmed the prospects for a greater, more pro-active UN presence in Rwanda that could have saved hundreds of thousands of human lives.

This article will examine each of these three requirements: detailed intelligence, preventive measures and political will. It will suggest alternative policies and actions that, in hindsight, should have been followed to further develop these capabilities. It is essential that the international community not only learn, but also implement, the lessons from Rwanda. In the words of US President Clinton: "Let us challenge ourselves to build a world in which no branch of humanity . . . is again threatened with destruction . . . to strengthen our ability to prevent, and, if necessary, to stop genocide."[7] We hope that this article, which proposes, in hindsight, detailed scenarios for possible genocide prediction and prevention in Rwanda, will contribute to such an effort.

BACKGROUND

Few outsiders could have anticipated that Rwanda, a tiny, mountainous nation located in the Rift Valley of south-central Africa, would provide the backdrop for an unprecedented African horror. To the casual foreign observer, Rwanda's rustic setting along Lake Kivu, its lush hills, its agrarian economy, and its pastoral culture created a semblance of simplicity and placidity. Rwanda seemed too remote, too unsophisticated and too docile of a nation, to produce nation-wide bloodshed and record numbers of refugees. When the UN peace-keeping mission was planned in 1993 the assumption was that this would be an easy, relatively trouble-free mission. Romeo Dallaire, the designated Force Commander, spoke of the lead up to the mission: "There was absolutely no perception that anything except the very positive vibrations that were coming out of Rwanda from both sides . . . the peripheral countries, the observers at the Arusha talks, that this was going to be classic peace-keeping operation. [The mood was one of] enormous optimism; buoyant."[8] This perception of Rwanda and the UN mission, however, was misguided. A careful examination of Rwanda's past reveals deep social tensions, a stalled agrarian economy, a history of political upheavals, and a frightening pattern of organized, mass killings in one of the most densely populated countries of the world.[9]

Historical Review

For the first half of the twentieth century, Rwanda was ruled by European powers, first by Germany from 1897 to 1916, and then by Belgium until 1962. Given their lack of manpower and resources, the Germans allowed the Rwandans virtually to govern themselves. Seeking political stability, they accepted the existing institution, a monarchy headed by a divine king, or mwami.

The king's subjects were divided into three principal social groups: the Hutu, Tutsi and Twa. The Hutu, mostly poor peasants, comprised the vast majority. The more prosperous Tutsi, including the mwami, owned land and cattle, the traditional indicators of wealth in Rwandan society. In 1990, they made up about 14 percent of the country's population, compared to the Hutu's 85 percent. The remaining one percent were composed of the peripheral Twa, groups of nomads and hunters who lived in forested areas. Hutus and Tutsis traditionally lived and worked together, their huts juxtaposed in villages throughout the Rwandan countryside.

The differences between these two social groups were not tribal, as they both spoke the same language, practiced the same customs, and lived under the same rulers. The primary distinctions were economic. Historically, only the minority Tutsi possessed cattle; this gave them a higher societal status and, thus, a preferred access to elite government posts. Intermarrying between the two groups was common.

After World War I, Germany lost its colonial foothold in Africa, and Rwanda fell under the control of Belgium. The Belgians exploited the disparities between the two principal social classes by giving the Tutsi educational and other preferences. They instituted an identity card system (which was later to become an important tool in the hands of the genocidists) whereby the "ethnic" identity of a person and his or her family became fixed and the former movement between the Hutu and Tutsi social classes was prohibited. The Belgians believed that the more "superior," more malleable Tutsi aristocrats, now easily identified, would be better able to institute European-style reforms. This belief led to widespread resentment by Hutus of both the Belgian colonists for creating the favoritism, and of their Tutsi neighbors for benefitting from it.

By the end of the 1950s, popular sentiment toward Belgian colonial rule, among Hutus and Tutsis alike, had changed from tacit compliance to fervid opposition. Each group sought both the establishment of an independent Rwandan nation and total control of that nation's government. Hutu and Tutsi political parties were formed. The cause for Rwandan independence was aided by the United Nations, increasing distaste of the Belgian rule, which had proven disastrous in the neighboring Congo, where the UN had to engage in a large peacekeeping operation beginning in 1960. In 1962, the Republic of Rwanda was formed, and elections brought the Hutus under President Gregoire Kayibanda to power for the first time in Rwandan history.

As in the neighboring Congo, Belgium had prepared its colony very poorly for independence. The underlying resentment between Hutus and Tutsis heightened. The transition to republican government was anything but peaceful and cooperative. During a two-month period in fall 1961, vengeful violence by Hutus led to the killings of over 100 Tutsis, the burning of over 3,000 homes, and the displacement of close to 22,000 persons. A report by the UN Trusteeship Commission concluded that "an oppressive system has been replaced by another one," and ominously predicted that "it is quite possible that some day we will witness violent reactions on the part of the Tutsi."[10] Indeed, the Tutsi refugees who had settled in neighboring countries such as Tanzania, Burundi and Uganda, began to form small, roving, armed bands - pejoratively labeled inyenzi or "cockroaches" by the Hutus - to engage in terrorist acts against the new Hutu regime.

The first decade of the independent Rwandan state involved repeated attempts by Tutsi rebels to overthrow the Hutu government by both subversive activities and overt military operations. In response, the Hutus in power inflicted widespread violence upon Tutsi citizens. As a result, by the mid-1960s over 20,000 Tutsis had been slaughtered, and more than 150,000 had been forced to flee to the nation's periphery.

In 1973, during a period of economic stagnation and anti-Tutsi sentiment, General Juvenal Habyarimana, the Rwandan Minister of Defense, overthrew the shaky regime of President Kayibanda. He established an authoritarian, nepotistic government dominated by his Hutu political party, the Mouvement Revolutionaire National pour le Developpement (MRND). The Habyarimana regime systematically worked to weaken and isolate Tutsi citizens. It required all citizens to carry cards that labeled them either Hutu or Tutsi. Through discriminatory policies, and sometimes open harassment, it weeded out Tutsis from positions in the military, civil service and local governments.

By 1990, Tutsi rebels in Uganda had organized a united, military organization dedicated to re-establishing Tutsi rule in Rwanda: the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). Its first major attack on the Rwandan government occurred on 1 October 1990, from Uganda. The RPF was formed by past refugees and the children of past refugees who had fled Rwanda after 1959 when the majority Hutus staged a "social revolution." From 1961 to the 1970s the Tutsi refugees had staged a number of armed returns to Rwanda. On multiple occasions between 1990 and 1993 the RPF launched military incursions from Uganda into Rwanda, plunging the country into civil war. With the encouragement of international organizations, such as the Organization for African Unity (OAU) and the United Nations, the RPF and the Habyarimana regime officially concluded a ceasefire in 1991, though this was broken on many occasions. In August 1993, at Arusha, Tanzania, they finally reached an agreement on a power-sharing arrangement that would return multi-party rule to Rwanda. To assist in the implementation of this agreement, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR) arrived in the capital of Kigali in October of 1993, under the command of Major General Romeo Dallaire from Canada. The UN peacekeeping operation was under the political control of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG), Jacques-Rogers Booh-Booh from Cameroon, who also had a good offices mandate to mediate between parties and facilitate the peace process.

During the first few months of UNAMIR's mission, however, the peace agreement between the Hutu and Tutsi representative institutions was far from being implemented. Then on 6 April, two surface-to-air missiles brought down the plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi as it approached the runway at Kigali airport. Almost immediately, the systematic, well-planned and merciless killings of Tutsis and Hutu moderates in Kigali began. In addition, ten Belgian paratroopers, part of the Belgian contingent of the UN force, were disarmed and murdered by Rwandan government troops as they sought to protect the Rwandan prime minister, who was assassinated. In the subsequent three months, the genocide swept across the country, as hundreds of thousands of Tutsis and political dissidents were slaughtered by the Hutu-dominated militias, the Interahamwe, as well as the gendarmerie and, not least, the Presidential Guard. The Presidential Guard was the best organized, most lethal force in the country. It was used for assassinations of senior political figures, for systematic herding of populations, and to clear out pockets of resistance for the weaker but much larger Interahamwe. News of the atrocities in Rwanda sent shock waves throughout the international community and the peacekeeping office at the United Nations.

Evidence suggests that a strengthened intelligence capability among the United Nations could have unveiled the detailed plans for this genocide. Furthermore, had the UN engaged in preventive diplomacy or, later, preventive deployment of troops, it may very well have been able to prevent many senseless killings that followed. Intelligence-gathering in several areas in particular could have provided clear and sufficient clues about the genocide months in advance: illicit arms flows, insider information on the genocide plots, the training and activities of the Interahamwe, the activities and reputations of the plotters themselves, and a long-standing pattern of ethnically-based human rights violations. Unfortunately, the UN did not analyze or synthesize these important pieces of evidence, nor did it pro-actively seek further information that could have corroborated and deepened the information at hand.

The UN also ignored a range of possible preventive measures. Before examining in detail these early warning signals and preventive actions, it is important to see if the UN actually had the mandate, if not the means or the initiative, to gather intelligence and to act upon it for prevention.

UN Mandate for Monitoring and Prevention

The UN peacekeeping force was first envisioned in the Arusha Accords, which were signed in Arusha on 4 August 1993 after almost three years of civil war between the government of the Rwandese Republic and the rebel forces of the RPF. The Accords were designed to bring an end to hostilities and to pave the way for a transition to democracy, with the UN force to play a major stabilizing role.[11] The Arusha Accords envisioned a series of democratic reforms, including steps toward a broad-based transitional government (BBTG), national elections, the integration of the armed forces of the two main combatants, and the repatriation of refugees who had fled to neighboring countries during the civil war.

In the Arusha Accords both parties pledged to promote the security of Rwanda. They promised to uphold the Ceasefire Agreement of 16 September 1991, which included the "suspension of supplies of ammunition and weaponry to the field," as well as a "ban on infiltration of troops and on the conveyance of troops and war material to the area occupied by each party."[12] These prohibitions imply that any type of movement of arms, including shipments from abroad, would violate the Ceasefire Agreement, and thus the Accords. Thus, by August 1993, the two official parties to the Rwandan civil war had agreed in writing to prevent the influx of arms to Rwanda.

The UN force, according to the Accords, was to "assist in the tracking of arms caches and neutralization of armed gangs throughout the country." Moreover, the mission was to have an even larger mandate to "assist in the recovery of all weapons distributed to, or illegally acquired by the civilians."[13] While the actual mandate of the force would be determined later by the UN Security Council, these proposed security missions show, among other things, that the negotiators of the Arusha Accords sought a proactive, investigative force designed to prevent the flow of arms to any sources of instability.

The mandate provided by the Security Council for the peacekeeping force was less ambitious, but it still committed the UN to lessening the militant conditions in Rwanda. Resolution 872 of 5 October 1993, which formally established the peacekeeping force, gave UNAMIR a primary function to "contribute to the security of Kigali," including by monitoring a "weapons-secure area established by the parties in and around the city." UNAMIR troops were also instructed to "monitor observance of the cease-fire agreement" embodied in the Arusha Accords, as well as "other demilitarization procedures." This force was to investigate "instances of alleged non-compliance" with the provisions of the Arusha Accords related to the integration of the armed forces. These "instances" could be either observable transgressions or hints of them. UNAMIR was also mandated to "investigate and report on incidents regarding the activities of the gendarmerie and police," ostensibly to ensure that these groups provided security and to contribute to an abating of tensions between the Rwandan government and the rebel forces of the RPF.[14] The United Nations had also planned to use UNAMIR as a complement to the already existing peacekeeping operation, UNOMUR,[15] which had been mandated to gather information about potential transgressions, chiefly the illicit flow of firearms through the border with Uganda, that might disrupt the peace process. This resolution demonstrates that in the months prior to the genocide, during which the secret preparations were taking place, the United Nations had possessed the mandate to investigate non-compliance with the Accords and to promote the security of Rwanda.

Even more broadly, under Article 1 of its Charter, the UN has a responsibility "to maintain international peace and security, and to that end: to take effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace and for the suppression of acts of aggression or other breaches of the peace."[16] According to Article 99 of the Charter, the Secretary-General possesses the power to bring potential threats to the peace directly before the Security Council.[17] In this way the Secretary-General can use his discretion to shine a spotlight on any matter that he feels may endanger the mission of the UN.

Furthermore, in the matter of the serious international crime of genocide, the international community has a legal as well as moral obligation to intervene. Article I of the 1948 "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide" requires that the 128 states parties (including all five Permanent Members of the UN Security Council) consider genocide a crime "which they undertake to prevent and punish."[18] This includes "conspiracy to commit genocide," "attempt to commit genocide," and "direct and public incitement to commit genocide" (Article III). Thus, planning for, or spreading propaganda for genocide are criminal acts, as the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda later was to uphold.[19] Article VIII of the Genocide Convention allows parties to summon the UN to take action for the "prevention and suppression of acts of genocide." In other words, any state party could present a charge of genocide before the UN, and call upon the organization to take action. In addition, parties to the Genocide Convention are obliged to "enact, in accordance with their respective Constitutions, the necessary legislation to give effect to the provisions of the present Convention."[20] Thus, parties to the Convention must make their obligation "to prevent and to punish" genocide part of their national law. In summary, a firmly established treaty gave both the UN and individual countries a responsibility to prevent the destruction of one ethnic or religious group, in whole or in part, by another.

Thus the UN had a mandate for proactive investigations and some authority and means for intervention. We can now examine the indicators and evidence that could, at least in hindsight, have been used to predict the genocide and the means that might have been used to prevent it.

EARLY WARNING SIGNALS

Illicit Arms

The country is flooded with weapons. Two beers will get you one grenade.- A Western Diplomat in Kigali[21]

The UN peacekeeping force had a strong mandate to monitor illegal arms, but there was a major deficiency in its investigative capability. We begin by focusing on the key weapons that triggered the genocide: the Soviet-made missiles that brought down the Rwandan president's plane.

The French newspaper, Le Figaro, has alleged that the serial numbers of the two surface-to-air missiles which struck the plane match those of missiles seized from Iraq by French troops during the Gulf War of 1991. The reporter, Patrick de Saint-Exupery, cited testimony from two anonymous officers of the French military, who claimed that the SAM-16 missiles, after being confiscated from Iraqi stockpiles, were sold to Rwandan government forces between November 1993 and February 1994 as part of a covert French policy labeled "le secret defense."[22] These missiles, smuggled into Rwanda from abroad, were just a small part of a massive weapons influx that violated the Ceasefire Agreement and created tremendous insecurity. Bernard Debre, the French Minister of Development at the time of the crash, repudiated the substance of the Le Figaro story and, in turn, accused the American State Department of supplying the missiles. Debre claimed that the two missiles were seized by American, not French, forces in the Gulf, and soon after sold to the neighboring country of Uganda.[23] Yet he produced no concrete proof that would shift responsibility for the missiles away from the French government. And further evidence shows that the missile affair fits a broader pattern of acts of French favoritism to the Rwandan government.

France was a principal source of arms for the Rwanda government under a policy of staunch support for the Hutu regime of Juvenal Habyarimana, the Rwandan president. According to the Human Rights Watch Arms Project, while regularly proclaiming to the international community its neutrality in the Rwandan conflict, France supplied machine guns, artillery, armored vehicles, and six Gazelle helicopters to the Forces Armees Rwandaises (FAR), the Rwandan army, after the outbreak of fighting in 1990.[24] In fact, French military officials often encountered difficulty obtaining approval of the Interministerial Committee for War Material Exports for arms transfers to Rwanda because the volume of equipment was so great.[25] Even high-ranking Rwandan government officials admitted to having received abundant French support. For example, the Rwandan Minister of Defense in June 1993, James Gasana, confirmed that a French bank, Credit Lyonnais, had guaranteed a $6 million arms deal between the Rwandan government and the government of Egypt involving the transfer of heavy artillery, mortars and Kalashnikov (AK-47) automatic rifles. In order to help finance the deal, the Rwandan government was forced to put up much of its tea harvest for collateral.[26] The magnitude of the deal suggests both that elements of the Habyarimana's regime had no interest in abiding by the Ceasefire Agreement, and that the French government had made a clear policy preference of unconditional military support to one party during a time when disarmament and impartiality were crucial to ensuring peace.

In the period leading up to Arusha, the Habyarimana regime played a direct role in the arming of civilians, justified as defence against an invasion from outsiders (Ugandan-based Tutsis). Its goal, according to a secret government document obtained by the Human Rights Watch Arms Project, was to distribute nearly 2,000 assault rifles to civilians loyal to the MRND, the president's political party, under the guise of a "self-defense" force. While this civilian force had not yet engaged in human rights abuses to the extent of the Interahamwe, the report cautioned that "it is frightening to ponder the potential for abuses by large numbers of ill-trained civilians equipped with assault rifles."[27] There was no slowdown in the import of military hardware to Rwanda; rather, high-ranking Rwandan officials were arming their citizens and militia, and trading tea for weapons. After Arusha, no weapons were supposed to come into the country, but that also was systematically flouted.

Arms had become plentiful in Rwanda; grenades were sold alongside mangos and avocados on fruit stands at markets around Kigali.[28] UNAMIR officials were aware of, but could not cope with or monitor, the extent of illicit arms transfers. They were unsuccessful, moreover, in obtaining the necessary UN approval to conduct searches, raids or to confiscate weapons from civilians and militia members. UNAMIR communications in the months before 6 April show that UNAMIR officers were aware that prodigious amounts of arms and ammunition were flowing into Rwanda and were concerned about the danger it presented, but they were denied permission by UN headquarters in New York to take offensive action to confiscate weapons.

Ominous signs appeared of a motive for the stockpiling and distribution of these instruments of death. A Belgian UNAMIR lieutenant sensed they were to be used for an impending catastrophe, as he was later to recall:

We also realized something big was being prepared, but we didn't know exactly what. But we learned quickly through informants that arms were hidden in the area and distributed in anticipation of the massacres.[29]

The UNAMIR mandate to help establish and monitor a "weapons secure area" around Kigali was being challenged. Under the mandate, it was agreed that weapons, except personal arms, could be transported only under escort by UN military observers. But machine guns and some heavy weaponry were readily seen. At the end of January 1994, SRSG Booh-Booh griped to the press that "weapons are distributed from arms caches around Kigali and even inside town."[30]

An informer named "Jean Pierre" declared to the UNAMIR Commander that there were four major arms caches. He even took an African UN peacekeeper to one of them at the headquarters of the MRND. There, in the building, he showed the astonished Senegalese soldier a large stockpile of weapons, mostly AK-47s, ammunition and grenades. (The Senegalese peacekeeper, who posed as a friendly African officer, obviously was not wearing a UN uniform, to permit passage through the sentry post at the entrance of the building.)

UNAMIR officials directly observed French involvement in weapons transfers. Under the direction of Belgian Colonel Luc Marchal, sector commander for Kigali, UNAMIR troops even confiscated a shipment of arms from France at the Kigali airport on 22 January. A UN military observer stationed at the Kigali airport noticed that an unscheduled flight was arriving. The pilot could present no manifest so Belgian peacekeepers surrounded the plane, and found a cargo of illegal arms and munitions, which was confiscated. Documents found in the plane gave evidence of many evasive maneuvers taken by the French and Belgian suppliers, including false end-users and circuitous routes. They also observed another shipment on 9 April, three days after the commencement of the genocide. In short, violations of the Arusha Ceasefire Agreement were plentiful, highly visible and fostered by non-Rwandan players.

To high-ranking UNAMIR officers, direct observation of the proliferation of these arms demanded rapid, preemptive action. Force Commander Romeo Dallaire had, in the first few days of January 1994, "implemented the first offensive ops [operations] planning against armed political militias and suspicious area." The peacekeeping force was to be "focused on ensuring the Kigali weapons secure area and gathering of information regarding armed political militias and suspicious area in order to prevent escalation of tensions."[31]

UNAMIR officials believed that information-gathering on weapons distribution was vital to their mission and planned to take offensive action. All that was needed was the physical/logistical capability and the approval from New York to carry out such operations. Since UNAMIR was considered a defensive mission, it lacked sufficient equipment, particularly armored personnel carriers, to undertake "search and seize" type operations. Even so Dallaire asked for permission to begin raids on the known arms caches. As well, UNAMIR commanders called on their superiors at UN headquarters to grant and arrange for future shipments of the necessary equipment. But neither additional equipment nor the authorization to conduct searches and seizures with the capability at hand were granted.

Conscientious Informers

Late in the day of January 10 I had a visit from someone who asked to be called "Jean-Pierre.' He was a leader of the MRND militia, the famous Interahamwe . . . He explained he was struggling with his conscience. He was in the process of systematically arming all cells of the capital. He'd received orders several days earlier to identify every Tutsi in each cell, and when word came, to assassinate all of them point blank. From what he told me, they were capable of killing about 1,000 Tutsi every twenty minutes, so this was an extensive organization, and that was our undoing.- Colonel Luc Marchal,

Commander of Kigali sector for UNAMIR[32]

The most startling and explicit early warning came from human sources. High-ranking UN officials in Kigali and New York were informed in clear language and with convincing evidence of a sinister plot to sabotage the peace process and carry out genocide.

The key personality was a former security aide to President Habyarimana who was responsible for training the Interahamwe. Referring to himself as "Jean-Pierre," the informer had several meetings with Dallaire and Marchal in which he disclosed a macabre plot to which, he claimed, he could not, in clear conscience, be a party. Jean-Pierre asserted that, since the arrival of the UNAMIR force, the goals of the Interahamwe had changed. While originally the militia served as a national force aimed at helping protect the country from RPF attacks, it was evolving into a partisan strong-arm designed to wreak violence against the country's Tutsis. As a leader within the Interahamwe, Jean-Pierre had been ordered to compile lists of Tutsis in Kigali which he thought were to be used "for their extermination." The informant said that while he supported the actions against the RPF, he could not "support the killing of innocent persons."

The organizers of the plan, whom Jean-Pierre said included leaders of the extreme factions of Habyarimana's political party, the MRND, sought to block the establishment of the new government, and to force UNAMIR to withdraw from Rwanda by engineering more violence. For example, Jean-Pierre had himself played a role in efforts to prevent the installation of the new members of the BBTG. In one operation planned for early January, the Rwandan opposition "deputies were to be assassinated upon entry or exit from Parliament," and RPF forces were to be confronted in order to "provoke a civil war." As it turns out, demonstrations by an organized mob in front of parliament were sufficient to stop the swearing in ceremonies. The plot was not hatched on schedule, but the preparations continued.

The informant asserted that if, during the swearing-in ceremony, the "Belgian soldiers resorted to force [to prevent the assassinations] a number of them were to be killed and thus guarantee Belgian withdrawal from Rwanda."[33] In addition, Jean-Pierre pointed out exact locations of Interahamwe weapons caches in and around Kigali that were to be used in the subsequent slaughter of Tutsis. According to Marchal, "a UN officer accompanied him to MRND headquarters. In the building there was indeed a stockpile of arms and ammunition," providing further irrefutable evidence to UN officials that arms were being improperly stored for distribution by the government.

It quickly became clear to Dallaire and Marchal that immediate action needed to be taken, as Jean-Pierre's assertions backed up their own observations. Faxes were sent to New York around the time of their meetings with Jean-Pierre giving clear evidence of the informant's credibility. As mentioned, Jean-Pierre had explained that deputies of the BBTG had been targeted on their way to and from the parliament. Confirming this, the outgoing code cable from SRSG Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh of 11 January 1994 mentions the establishment of road blocks by the Presidential Guard and the Interahamwe around Kigali, and that "their aim was to prevent the deputies from getting to the parliament and to prevent essential meetings at Prime Minister level and senior political levels in order to solve the impasse between the parties." In the process, "civilian drivers were beaten." The cable also mentions that hundreds of armed protestors loyal to the MRND "blocked the entrance to the parliament and harassed deputies," a description of events which corroborates the informant's story. In addition, UN officials had verified the existence of the weapons caches first-hand.

Also on 11 January, Dallaire sent an urgent fax to New York, addressed to Major General Maurice Baril, the UN Secretary-General's military advisor, describing the informant's revelations that there was a plan to "exterminate" the Tutsis, brutally sabotage the peace process, remove the Belgian peacekeeping contingent and provoke a civil war through forceful confrontation (see Appendix). Within the "genocide" fax, as it has come to be called, Dallaire outlined his plan to raid arms caches promptly to prevent the contents from being used in the plots. "It is our intention to take action within the next 36 hours," Dallaire wrote. "Recce [reconnaissance] of armed cache and detailed planning of raid to go on late tomorrow."

Dallaire noted that Jean-Pierre would be willing to offer further information, specifically the locations of more weapons and ammunition, in exchange for a UN pledge to provide protection and asylum. "He was ready to go to the arms cache tonight," Dallaire stated in the fax, "if we gave him the following guarantee. He requests that he and his family be placed under our protection." Dallaire went on to urge his superiors in New York to grant Jean-Pierre's request, but indicated that he had little background on UN policy in this area. "It is recommended the informant be granted protection and evacuated out of Rwanda," wrote the Force Commander. "This HQ does not have previous UN experience in such matters and urgently requests guidance."

No doubt the plots represented a major threat to the goals of the UN mission as well as to the lives of the peacekeepers themselves. The presence of secret weapons caches undermined the security of Kigali and were a violation of the Ceasefire Agreement upheld in the Arusha Accords. Moreover, plots to provoke civil war would mean the failure of all efforts to bring peace to the war-torn country. They should have sounded alarm bells in the mind of peacekeeping officials in New York. But action was not forthcoming; guarantees for the informer were not given. Over the next few months, the ominous revelations were forgotten in the hustle and bustle of regular diplomatic and peacekeeping activity. Besides, other issues were pressing on the UN and troubling its leadership.[34]

The informant's revelations called for a bold UNAMIR response beginning in January. As was mentioned earlier, Dallaire was ready to take preemptive measures, which he described in detail in his fax, but he was denied permission from his superiors in New York to raid the weapons caches. He was told instead to divulge the plan to the government head, President Habyarimana, whose inner circle included members of the Akazu (or "little house") who were developing the genocide plot. "New York advised Dallaire, "You should assume that he' - Habyarimana (President of Rwanda) - "is not aware of these activities, but insist that he must immediately look into the situation'."[35] By denying permission to provide guarantees for Jean-Pierre, by failing to act to gain more information on a continuing basis and by vetoing proactive preventive actions, New York blundered. Perhaps in the hope that others could take initiatives where the UN did not, Dallaire was also told to inform the ambassadors of the United States, Belgium and France, which he dutifully did. Jean-Pierre broke off contact, not being willing to risk his life and the lives of his family members.

Nefarious Plotters

I am planning for the apocalypse.- Theoneste Bagosora, January 1993

Plans for the genocide had been "in the works" for some time. In early 1993, when a friend asked Col. Theoneste Bagosora, a key plotter, what kind of work he was doing, he replied with the above cryptic quote. But this sinister and detailed planning needed to be done carefully, incrementally and, above all, secretly.

Still, rumors about it were in circulation. For instance, in October 1992, Belgian Professor Filip Reyntjens had described the notorious group as composed of Coalition pour la Defense de la Republique (CDR) and Akazu leaders, and extremist military and Interahamwe units dedicated to promoting their ideal of "Hutu power." The possible existence of "Network Zero," a group of extremists who planned Tutsi massacres, was noted in the report of a UN Special Rapporteur in 1993. The "Zero Network" was likened to a Latin American death squad, able to roam the country slaughtering Tutsis with no censure from the government. Indeed, it must have had the tacit approval of President Habyarimana, who was negotiating, under considerable international pressure, to obtain the most favorable terms against the Tutsi rebels.[36]

The names of the organizations and many persons responsible for the genocide are now well established. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) has indicted many of the leaders. NGO groups, such as Africa Watch, have provided detailed accounts based on interviews conducted after the genocide with a wide range of Rwandans. It is more important, however, to discover if the sinister organizations and individuals were identified prior to the genocide. The Human Rights Watch Arms Project did produce a report in January 1994 that described an inner circle of nefarious figures around the president, but it couldn't confirm the existence of the group.

[A] persuasive number of non-French Western diplomats, Rwandan military officers, and civilians with a long standing personal relationship with Rwandan President Habyarimana told the Arms Project that they suspect members of the regime, and in particular the first circle or so-called "little house' around the President . . . to be responsible for these terrorist attacks. These people told the Arms Project that powerful elements in the Akazu, who have largely ruled Rwanda since 1973, opposed both the negotiations to end the war and the opening to opposition political parties. Nonetheless, there is no proof at this time.[37]

An inner circle of political figures close to President Habyarimana, the Akazu, served as the backbone for planning the massacres. The leaders of this group consisted of the president's wife and extremist military officials, including Habyarimana's brother-in-law, Col. Eli Sagatwa, and Col. Leon Mugesera. This clique opposed any compromise with the RPF and the opposition parties, both of which were to be included in the envisioned BBTG under the Arusha Accords. The Akazu also served as a propaganda engine for extremist elements of the MRND and the CDR, a radical party seeking a "final solution" to the ethnic conflict between Tutsis and Hutus, and later one of the main organizers of the genocide.

Dallaire later called Col. Theoneste Bagosora the "king-pin" in the genocide plot. But Dallaire did not know this when the crisis erupted, to the great detriment of his mission. Within hours after the plane crash and the death of the president, he sought and received Bagosora's assurance that the Rwandan army troops would stay calm. Little did Dallaire know that Bagosora's troops had been sent to assassinate the Prime Minister, Agathe Uwilingiyimana, kill the Belgian troops protecting her, and murder the leaders of opposition parties, the president of the Supreme Court, and many human rights activists.

Vile Propaganda

The only remedy is total extermination, to kill them all, totally wipe them out.- Hutu extremist radio Radio-Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) broadcast before the genocide[38]

Throughout the Arusha period, extremist elements within the Rwandan government, including the plotters of the genocide, attempted to whip up public anger, hate and vengeance against the Tutsis. Inflammatory speeches and chants were broadcast throughout the country by RTLM created precisely for that purpose. The peacekeeping force monitored several of these radio broadcasts.[39] But it was hard to take them as serious, authoritative or credible, because they were so extreme. They fully demonized the Tutsis in an incredible and unrealistic fashion, for instance by likening them to cockroaches (inyenzi) that needed to be exterminated.[40] Belgians were also targets of propaganda. Unfortunately, UNAMIR and the UN did not analyze these broadcasts to determine what the specific threats and consequences could be, e.g., who might be the next targets for assassination or massacre.

The seriousness of this hate propaganda became all too evident to UNAMIR in the early stages of the genocide, when the radio station advocated the death of Belgian peacekeepers, who were accused as perpetrators of the assassination of the president:

These Belgian bandits have committed many atrocities that merit punishment. We Rwandans will never forget that these bandits killed the President we loved. The red-skinned Belgians have behaved like beasts. They should pay for their acts.[41]

It is relevant to recall that the sinister plan to kill Belgian peacekeepers had been revealed some three months earlier by the informer Jean-Pierre. He had accurately foretold that Belgian paratroops would be targeted and killed to "ensure their withdrawal." The Belgian government unilaterally withdrew its contingent from UNAMIR in less than ten days after the killings.

As the genocide developed, the extremists used the airwaves to justify their actions and to assign blame on the Tutsis for the nation's shortcomings. Outrageously cruel and inhuman broadcasts filled the airwaves. Macabre lines were set to popular tunes. These chilling words, set to a charming melody, were sung on the air:

Where are those Tutsi who used to phone me? Ah, they must have all been exterminated. Let us sing: The Tutsi have been killed. God is always just! The criminals will be exterminated![42]

Public rallies were another means of spreading propaganda, inciting violence and preparing the Hutu majority to condone, if not commit, the atrocities that were to occur. Venomous speeches by members of Network Zero immediately preceded several massacres of Tutsi civilians. For example, in November 1992, the MRND-leader Dr. Leon Mugesera viciously urged a crowd to take up arms against their Tutsi neighbors. "Their home is Ethiopia," Mugesera declared. "Let's find them a shortcut to get back there. That's the Nyabarongo River." The very next day, small-scale massacres of Tutsis were reported in the Kibya region of Rwanda, and bodies were dumped in the river.[43]

On 7 April 1994, the Prime Minister of the Interim Government, Jean Kambanda, rallied Hutus while holding a gun aloft: "The enemy uses his gun, you must fire back! Go behind the front line, find their accomplices. Shoot to kill! Everyone must have his own gun, don't be afraid to use it."[44] Fortunately, this speech was videotaped and later used against Kambanda in his trial before the International Tribunal. He was sentenced to life in prison on 4 September 1998 after having pleaded guilty to genocide charges.[45]

Macabre Militia

All parties in Rwanda and all over the world have young people as members. That is what we have. But we do not have militias.- Matthieu Ngirumpatse, chairman of the MRND, 27 April 1994[46]

We know that they [MRND] gave them weapons and trained them militarily up to one thousand and seven hundred . . . We have the army, we have the police force to protect the country, what are the others for?- Parti Social Democrate (PSD) spokesman Felicien Gatabazi[47]

The Interahamwe are well trained military killers.- article in the Rwandan press, 17 March 1992[48]

The origins of the militia in Rwanda date back to the period following the signing of the initial ceasefire agreement between the FAR and the RPF at N'Sele on 29 March 1991. Given the invasions by RPF forces, the Habyarimana regime wanted to use civilians to boost the defense of Rwanda.[49] It sought to strengthen defense forces without violating the spirit of demobilization and disarmament embodied in the ceasefire agreement. By arming civilians, the regime believed it could accomplish these goals. This defensive concept of the militia in Rwanda was confirmed by the informant, Jean-Pierre, who told Dallaire (as reported in the fax of 11 January 1994) that the main objective of the militia "in the past was to protect Kigali from the RPF." One meaning of the word Interahamwe is "those who have the same goal" (or "those who fight together"), and the Interahamwe, on the surface, appeared to be a patriotic organization dedicated to helping repel RPF advances. Yet the motives of its suppliers and its leaders, and the way in which the Interahamwe was trained, demonstrate that, at its roots, the organization was more of an engine for killing civilians that would eventually carry out most of the genocide.

Several frightening characteristics of the Interahamwe should have sounded alarm bells in the minds of UNAMIR officials in Kigali and New York. For example, extremist individuals played a role not only in supplying the Interahamwe with arms, but also training its members in combat tactics. Extremist government officials within the CDR and the ruling party, the MRND, were also instrumental in providing support to the Interahamwe. During the Arusha period, these groups exploited foreign resources to indoctrinate militia members. For example, the Rwandan College was a sectarian institution for Rwandan youths established and assisted by the government of Canada since the 1960s. Soon after the emergence of the Interahamwe the head of the college, Father François Cardinal, complained that Canadian funds were being diverted from the school and used by high-ranking government officials, probably to equip the militia. Father Cardinal accused Colonel Leon Mugesera, a member of the Akazu, of being responsible for this act of corruption. Henceforth Canada withdrew aid for the College.[5] Father Cardinal was expelled, soon after registering his complaint, from the Rwandan College by Rwandan leader Eli Sagatwa, a member of the Akazu. He was later assassinated.

As arms poured into Rwanda and tensions escalated during the post civil-war period, it became clear to members of the local media that the Interahamwe was not merely a "youth movement," as Habyarimana had once labeled it. In March 1992, an article in the Rwanda press portrayed the Interahamwe as "military killers." Leaders of the Interahamwe trained their subordinates not to defend territory, but rather "in commando tactics such as the use of knives, machetes, rope trapping and binding of victims and silent guns so as to kill people." The article pointed out that the militia had become more ideological and apocalyptic in its doctrine. Members were trained to believe not only that the RPF was the enemy, but that rival political parties "will jointly kill members of the MRND."[51] Moderate government officials were aware that the training of the Interahamwe could lead to more killing. The Minister of Finance at the time, Marc Rugenera, stated after the genocide that "the military training given to the militias of MRND and CDR is part of the evidence that the killings were planned and prepared long in advance."[52]

Some elements of the Rwandan media held that the newly trained and equipped militia were responsible for civilian massacres, and even predicted, months before the commencement of the genocide, that massive killings would take place. On 17 December 1993, the journal Le Flam beau mentioned that plotters within the MRND and CDR were seeking a "final solution" comparable to that of Hitler. It stated that "political adversaries and defenseless populations" would be targeted and slaughtered. The journal also announced that "about 8,000 Interahamwe sufficiently trained and equipped by the French army await the signal to begin the assassinations among the residents of the city of Kigali and its surroundings."[53] Such an ominous prediction, however, passed without a response from UNAMIR.

UNAMIR possessed neither sufficient mandate nor personnel to monitor the training of the Rwandan militia. UNAMIR officials came to understand from informants and arms monitoring - not through direct observation or oversight of the training of its members - that the militia posed a danger to the peace process. For example, Dallaire's fax of 11 January 1994 states that the informant did mention the existence of 1,700 Interahamwe members trained in "discipline, weapons, explosives, close combat and tactics." Yet even the fax failed to take into account the extremist, apocalyptic rhetoric and tactics of slaughter included in their training program. Similarly, while patrolling UNAMIR units did observe movements of arms in the country by the Interahamwe, they did not directly observe the training or uncover the doctrine taught at the militia camps.

UNAMIR possessed a mandate to "investigate and report on incidents regarding the activities of the gendarmerie and police."[54] The gendarmerie included "communal policemen" of the countryside who, according to African Rights, "were among the very worst killers." While the gendarmerie is a separate organization from the Interahamwe, African Rights reported that "the Interahamwe would not have had the force they did if it were not for the weapons and physical support they obtained from the communal policemen."[55] To carry out its mandate to monitor the gendarmerie and police, UNAMIR established a civilian police contingent (CIVPOL) of 60 personnel in December 1993. This unit sought to monitor, among other areas, the training school for the gendarmerie. While CIVPOL reported 54 instances of "serious crimes, complaints and allegations of human rights violations" as of the end of March 1994, it made no claim that the gendarmerie and police were in any way complicit in planning the massacres of Tutsis or moderate Hutus. Later, the two organizations were to become an integral part of the killing machine. Nevertheless, the progress report of CIVPOL of 30 March 1994, did determine that the "security situation in Rwanda and, especially in Kigali, has seriously deteriorated" and pointed to "the availability of weapons" and "ethnic and politically motivated crimes" as principal causes.[56]

While the training methods of the Interahamwe alone could have served as a warning signal to peacekeepers, the history of atrocities committed by the militant organization provided even more concrete evidence of wrong-doing and a portent of things to come. Parts of this militia collaborated with extremist elements of the Presidential Guard in Network Zero, which sponsored death squads and compiled lists of Tutsis and moderate Hutus to be killed. In mid-March 1992, between 60 and 300 Tutsis were killed and over 10,000 were displaced in Bugesera. Similarly, 300 Tutsis were butchered in Gisenyi during one week in January 1993, almost immediately after the early agreement on power-sharing had been announced.[57]

Immediately prior to and during the Arusha period, the number of massacres appears to have decreased, perhaps due to international pressure and the UN presence. The killings became more selective. The targets for assassination were mostly moderate government officials and human rights leaders, many of whom were Hutu. The Network Zero, using Interahamwe forces, orchestrated grenade attacks against leaders of parties in opposition to the MRND, parties who would have obtained greater power under the envisioned BBTG.[58] Network Zero was responsible for the killing of Samuel Gapyisi, leader of the Mouvement Democratique Republicain (MDR), the most prominent rival of the MRND, in May 1993. Felicien Gatabazi, head of the Parti Social Democrate, the second-largest opposition party, was murdered in February 1994, apparently because he was a moderate who appealed to Hutus.

Horrendous Human Rights Violations

History paints a large, dark backdrop to the sinister genocide. Rwanda had suffered widespread killings and long-standing human rights abuses for several years. It was not, however, always easy to tell who did the killings, whether FAR, the RPF, the Interahamwe, local gangs or even individuals. What was needed was an analysis of the killings to reveal patterns and causal links. The UN force did not do this kind of analysis, nor did UN headquarters. Most of our information on human rights violations, both then and now, comes from human rights organizations.

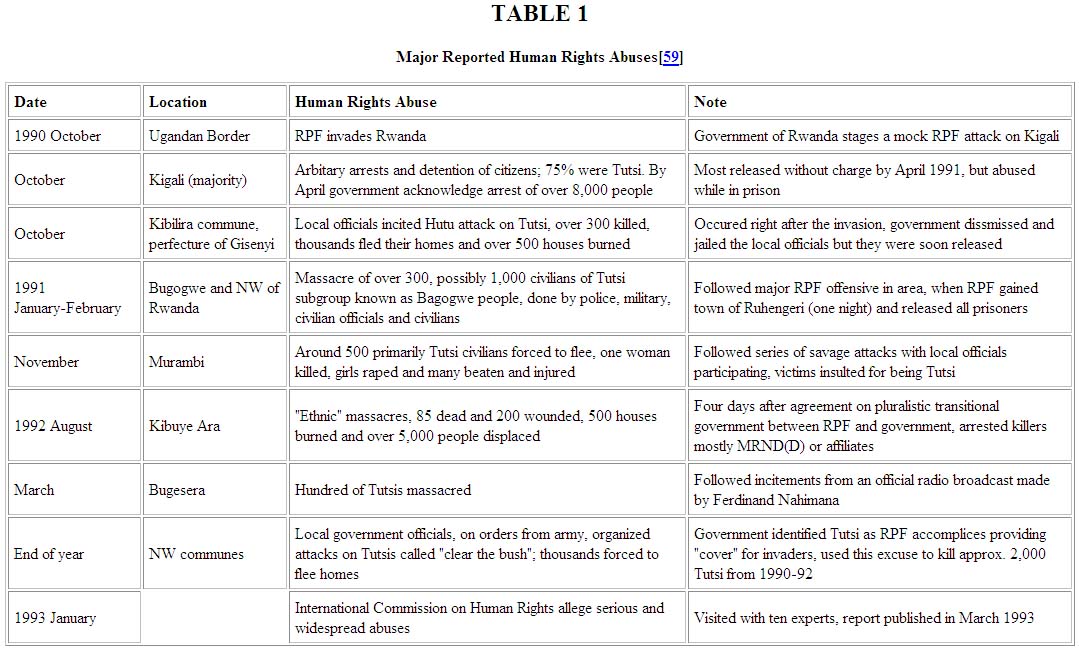

NGOs in Rwanda had documented a history of human rights abuses that indicated clearly the propensity for violence, if not genocide. These violations, which are summarized in Table 1, had been occurring since independence, but escalated immediately after the RFP attack on Rwanda in 1990. From October 1990 to April 1991, the government arrested over 10,000 people, of whom three-quarters were Tutsi. Most were released without charge by April 1991. In the northwest prefecture of Gisenyi local officials incited Hutu attacks on Tutsi civilians. The mobs killed over 300 Tutsis, burned over 500 houses and caused thousands to flee their homes. This pattern of sporadic massacres of the Tutsi population, seemingly in response to RPF attacks, ceasefire agreements and international interference, included the massacre of the Babogwe people in January and February 1991, Tutsi massacres in the Kibuye area in August 1992 and the Bugesera massacres of Tutsi in March 1992. During the visit of the International Commission of Inquiry in January 1993, burgomasters (mayors) in the northwest warned that violence would flare up when the commission left. RGF Captain Pascal Simbikangwa, in full view of the Commission, threatened the executive director of the Rwandan Association for the Defence of Human Rights and Public Liberties with death. After the Commission's departure MRND and CDR militias led attacks on Tutsi across the country, leading to the death of over 300 civilians. International human rights reports continuously stressed the involvement of government officials and, by 1992, the role taken by the MRND and CDR militias in leading the attacks. Following the massacres, road blocks were put in place to prevent victims from fleeing the area, and the UN Special Rapporteur noted during the 1993 massacres the "phone system had suddenly "broken down' (in the areas involved) . . . and had curiously become operational again without any needs for repairs."

Table 1

Major Reported Human Rights Abuses[59]

As mentioned, in January 1994, three months before the genocide, the Human Rights Watch Arms Project report pointed out many human rights violations. It surmised that, since the commencement of hostilities between the FAR and RPF in October 1990, approximately 2,000 civilians had been killed at the hands of the militias. The report stated that "most of the victims were Tutsi, and they were killed for the sole reason that they were Tutsi." Moreover, it warned that the armed bands were well dispersed throughout the countryside, and that "they remain in place and ready to move when ordered."[60]

Human Rights Organizations: Did They Do Better?

Human rights violations in Rwanda were monitored extensively by international human rights organizations from the onset of the conflict in 1990. Native Rwandan human rights groups considerably aided their international counterparts in investigating and uncovering human rights violations. Gerard Prunier states that these organizations were strong "and well organised . . . and their militants were taking personal risks in gathering what were soon to become very precise and damning reports on the situation in the country."[61] For example, it was at the request of Rwandan NGOs that an International Commission of Inquiry, consisting of ten human rights experts, visited Rwanda in January 1993, releasing a 100 page report in March. Given the extensive coverage by international human rights organizations, it is reasonable to ask if these NGO groups provided the international community with explicit early warnings of the genocide. If not, could the information they gathered have played a role in early warning?

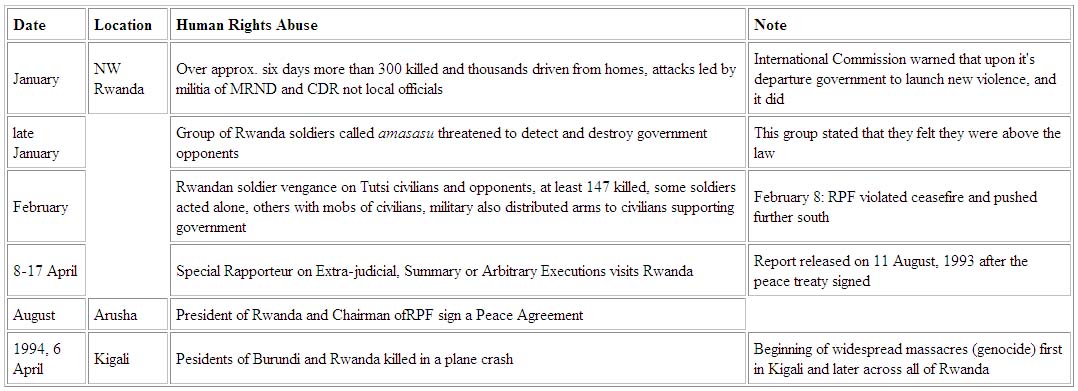

A summary of the main allegations included in the major reports published by international human rights organizations on Rwanda is presented in Table 2. The reports provided unequivocal evidence of major and on-going human rights violations, as confirmed by successive reports by different groups. The reports pointed to violations by all levels of people, from civilians to government officials and by both the RPF and FAR. These organizations had long standing involvement in Rwanda even prior to October 1990. In 1993, the RPF offensive caused "the largest, fastest displacement [of people] the humanitarian agencies had ever seen." Janice Stein and Bruce Jones state that these NGOs put on hold all of their regular programs to rush to the aid of these displaced people and, hence, were no longer in a position to report on signals of the impending genocide, which originated in Kigali.[62]

Table 2

Summary list of the types of abuses, violations

and other indicators reported by human rights groups.

Yet the reports of the international groups fall far short of predicting future atrocities. The published reports, upon careful review, do not provide explicit early warning of the 1994 genocide. None state or surmise that a genocide, or even large massacres, were being planned for the future. The closest the reports came to making predictions is the alleged existence of sinister groups with nefarious but unconfirmed aims. The UN special rapporteur, in August 1993 (before the Arusha Accords were signed), comes the closest by calling attention to a "second power that exists alongside that of official authorities." He expresses alarm at the widespread proliferation of weapons and notes that "one spark is all that is needed to cause the situation to degenerate," but does not point to actual plans or machinery to propagate genocide. The Human Rights Watch Arms Project notes in January 1994 that "the possibility of renewed fighting is very real," but this refers to the FAR/RPF conflict and not to any massive genocide campaign by the Rwandan government.

This analysis confirms that, in general, international human rights organizations, including the UN Commission on Human Rights, do not act directly as early warning systems. As was the case in Rwanda, they publish reports documenting violations up to the time of publication, but rarely try to directly predict future ones. The reports often describe the events that have taken place, the locations, the people involved and the possible perpetrators of all forms of human rights violations (while seeking to maintain the confidentiality of those at risk). Typically, the organizations then make recommendations both to bring past violators to trial and to end the continuation of abuses. They also actively lobby governments, both foreign and national, to stop the violations. Finally, they actively promote, through the media, public awareness of human rights violations. But human rights organizations generally do not possess the systematic methods for scenario building or threat assessment needed to make predictions of future events.

This does not mean that human rights monitoring is not a valuable source of information for early warning or that human rights organizations cannot, in the future, create early warning systems themselves. The information and evidence uncovered by human rights organizations in Rwanda could easily have helped confirm the existence, activities and plans of "Network Zero." NGOs did demonstrate the continuous involvement of government elements in past massacres of the Tutsi minority and Hutu moderates. By reporting on-going violations throughout the Arusha Peace process, their information helped foreign officials gain a better understanding of the instability of the situation and the possibility of future obstacles to the peace by both the parties and extremist groups operating outside of the peace talks.

In late 1992, at the insistence of indigenous Rwandan human rights organizations, the International Commission of Inquiry was created to investigate human rights abuses in Rwanda. Experts from four different International NGOs[63] stated that authorities at the highest levels condoned and even consented to the abuses, while the Tutsi victims were attacked for the sole reason that they were Tutsis. By the end of 1992, the Commission also discovered that the militias of the MRND and CDR had taken a leading role in the violence, "privatizing" human rights violations (by moving responsibility away from the government) and expanding the scope of the victims to members of the political opposition.[64] Furthermore, the Commission uncovered mass grave sites and heard testimony to the effect that the president of the republic chaired a "death squad" meeting prior to the Bagogwe massacres.[65] The Rwandan government responded to the allegations, but human rights groups discovered that following these pledges no action was taken by the government to end the abuses.

By the middle of 1993, human rights reports became more insistent that abuses must be stopped. Africa Watch reported the existence of "official lists" of accomplices and the distribution of arms to civilians supporting the president.[66] The UN special rapporteur for extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions, who visited Rwanda from 7 to 18 April 1993, provided the most damning report on the Rwandan situation. He supported the substance of the report from the International Inquiry, and went on to report on massacres, death threats and political assassinations, impunity for the killers, propaganda on Radio Rwanda, and the distributions of arms to civilians. Furthermore, he stated that FAR were "accused of incitement to murder and of giving logistic support to the killers."[67] Most important, he discussed the existence of "death squads" with high level government involvement in a clandestine organization known as "Network Zero," a "second power" actively attempting to discredit the peace process through the creation of "a climate of terror and instability." Finally, he called for the immediate dismantling of all violent organizations and the prosecution of all members "whatever their rank," and he offered a statement to the effect that the past massacres could be considered genocide due to their ethnic motivation. His report came out after the signing of the Arusha Peace Accords, and in face of the hopes engendered by the Accords, the report caused little stir, as many hopes were pinned on the new peace process. Yet the Human Rights Arms Project reported in January 1994 that the "possibility of renewed fighting is very real."[68] This report discussed secret documents implicating the government in the formation of paramilitary "self defense" groups and even discussed the Interahamwe and Inpuzamugambi militias who had taken a lead role in the violence. By March 1994, several indigenous human rights activists in Kigali had sent their children out of Kigali due to increasing tension. Human Rights Watch later claimed that by this point the preparations for the slaughter were well-known to NGOs and diplomats, and that "[r]epeated warnings by human rights activists . . . sent a clear signal that a crisis was imminent."[69] The organization does not state when or to whom these warnings were communicated or their substance.

PREVENTIVE ACTION

Peux ce que veux. Allons-y.[70] [Where there's a will there's a way. Let's go.]- Major General Romeo Dallaire, Force Commander of UNAMIR, 11 January 1994

Early warning of the Rwandan genocide was clearly possible for the UN, given the large number and types of signals described above. What, then, about prevention of the genocide? Senior political leaders in both the UN and governments have already stated that the genocide could have been prevented or at least mitigated. But neither the politicians nor the practitioners (nor the academics for that matter) have described precise measures and detailed scenarios to demonstrate possible means of genocide prevention or mitigation.

Most commentators on the UN's failure in Rwanda merely state that UN troops could and should have been deployed to stop the spread of the genocidal fire once it had been started on 7 April. This possibility is examined in much detail later in this section. But in conflict, as in medicine, prevention is better than cure. Particularly in this brutal and senseless slaughter, it would have been much easier to stop the machinery of genocide before it had been set into motion. Therefore, it is especially important to look at the early preventive measures that could have been taken before the plane crash in which the president of Rwanda died, i.e., during the period between January and 6 April 1994. These measures may not have guaranteed success, but they may very well have helped prevent or mitigate the tragedy. At the very least, they are worth exploring in hindsight.

Preventive Measures Before 6 April

While any preventive measures after April 6 would have required the strong application of armed force on the part of the UN to stop the spread of genocide, preventive efforts prior to 6 April would have involved a creative array of more subtle actions: preventive diplomacy, demonstrations of resolve, political lobbying and moderate shows of force. The main tool would have been information as opposed to weapons, and the main forum would have been the office room and not the battleground. The 2,000 or more UN troops present, plus others that could have been added, would provide credibility to the UN presence, but the main role for prevention would rest with the SRSG and his political affairs officers, UN CIVPOL, (of which there were about 60), human rights observers (which were only introduced by UNAMIR later), and a proposed information/intelligence unit in the field under the SRSG. The goal would be to cause the genocidists to reconsider, delay or even abandon their plans, and to have them removed from power or isolated, or in the very least, frustrated in their planning.

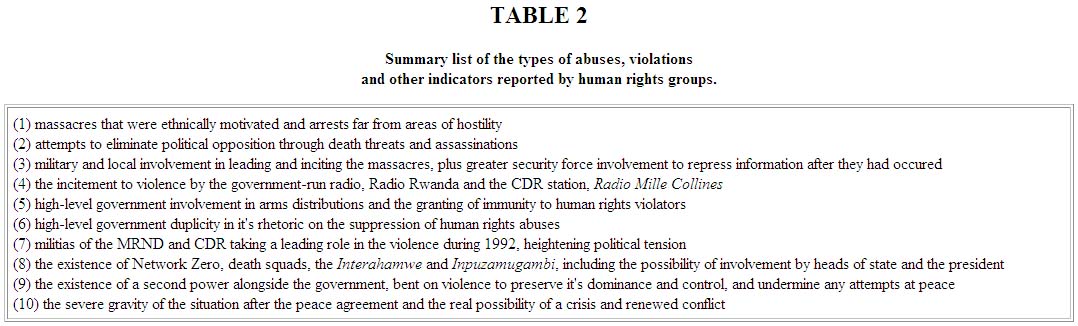

For each effort of the genocidists to prepare for the holocaust, producing early warning signals (summarized in Table 3), the UN could possibly have provided a response aimed at de-escalation. In response to illicit weapons flowing into Kigali, a more forceful policy of insistence on the embargo, monitoring and confiscation might have been applied by the peacekeeping forces and governments in accordance with the agreements. Where a network of senior Rwandan officials was being trained to carry out genocide, a few selected individuals in the chain of command could have been influenced by their foreign trainers (e.g., French officers), UN contacts (officials working with the SRSG and the UN force), and conscientious colleagues (e.g., like the informer Jean-Pierre) to provide inside information and refuse, avoid or minimize their participation in the planning and execution of genocide. The loyalties in the Rwandan government were not strong, the number of people willing to talk (even confess) was high, and, as discovered by UN and aid personnel, the degree of general respect for international personnel was unusually high. Diversions of international aid funds, which was suspected in Interahamwe training, could have been exposed by international officials, based on the investigations of rumors and reports. The genocide leaders could have been identified and isolated or perhaps dismissed through the application of political influence on the political system, or more specifically on the Rwandan president, who was eager not to displease the international community. Additional pressure could have been applied to reduce the level of threatening propaganda and, if necessary, to have the extremists' radio station closed down. These and other measures, which would have engendered hostile responses, will be examined in some more detail.

Table 3

The Early Warning Signals Known to the UN

In broad overview, the UN preventive actions could involve dealing with people (both plotters and resisters), the genocide structures (networks) and the tools (i.e., weapons) of the genocide. In all three categories, the key would have been a good information-gathering and analysis system. It was vital to identify who the genocidists were, uncover their plans and locate the weapons that were to be used. In the plans for UNAMIR I, unfortunately, the UN did not provide for an intelligence capability, though UNAMIR II, created after the genocide, possessed considerable intelligence expertise. Even without a dedicated intelligence unit in UNAMIR I, more information could have been gathered and analyzed by political affairs officers with the SRSG and at headquarters, working closely with the Belgian contingent and the UN civilian police.

To identify the plotters, it would have been necessary to gather more information from the informer Jean-Pierre and others. It was a serious mistake for the UN representatives to go to the Rwandan president in early January and reveal their information before the connection between the president and the plotters was determined. It would have been wise to gather more information about the nature of the "extermination" plots and to evaluate the degree of support for the plotters. Later, if the UN had come across information that the president himself was to be targeted, that information could have been extremely useful in convincing the Rwandan head of state to take forceful action against the plotters. It is likely that the president would have dismissed key plotters had he learned that his own life was at stake.

As it turns out, General Dallaire appeared to be completely in the dark about the plot and plotters on the day of the plane crash. He went to Col. Bagosora, who had effectively taken control of the military, to plead for restraint and the immediate installation of the moderate prime minister as acting president. Dallaire received a polite, reassuring and totally disingenuous reply on the deployment of troops, and a negative response on the question of installing the prime minister, who was dismissed as "incompetent." Bagosora had already sent soldiers to assassinate the prime minister and Belgian peacekeepers. Thus ignorance was very costly to Dallaire and the UN.

To engage effectively in the subtle art of preventive diplomacy, the UN peacekeepers and peacemakers (such as the Special Representative of the Secretary-General, or SRSG) would have had to identify and understand many characteristics of the plotters: what the power base was; who might oppose them; their relationships to the president, the cabinet, the army, police, Interahamwe, and the political parties; and their ties to other nations. Armed with such information, the SRSG could carefully develop a political strategy, beginning with moderate political leaders, to oppose and expose the genocidists. In a discreet, intelligent fashion, the SSRG could inform others of the genocidists' actions and intentions. At some point, he could even let them know in a subtle fashion that they were under suspicion and their activities being questioned. If momentum built, he could insist on their dismissal. While such influence may be hard to build, past UN mediators have been able to exert considerable authority on conflicting parties, whether it be in the Middle East, Asia or Central America.[71]

It would have been desirable and easy to identify potential resisters of genocidal plots. The obvious contacts for any UN intelligence-gathering effort would be human rights groups and moderate political leaders, including the prime minister, as well as prominent Tutsis. Such links could be forged, not only as a means to get more information, but also to apply pressure on and isolate the plotters. Rwandan military officers could have been subtly encouraged to share information. Instead, the courageous informer Jean Pierre was given the cold shoulder by the UN at an early stage (though fortunately he managed to survive).

The institutions preparing for the genocide, such as the Interahamwe, the Presidential Guard, Network Zero, and Radio Mille Collines, could have been brought under pressure, especially as evidence of their complicity in genocide plots mounted. These organizations, like many in Rwanda, relied on some measure of foreign support. More exact accounting for funds and materials could be insisted upon, any diversion of funds could be exposed by investigators (using tips, of which there were many), and the perpetrators identified and, if possible, punished. The radio station, which was broadcasting extremist and incredible messages of hatred, could be brought under stronger pressure and closer supervision in the interests of peace and moderation. Had repeated UN warnings gone unheeded, the UN peacekeepers could have temporarily halted radio broadcasts, jammed them, or even closed down the radio station, as was done in Bosnia to the radical Serb radio station.

Finally, there were the weapons themselves. General Dallaire had prepared plans to raid illegal arms caches in and around Kigali, but this was vetoed by UN headquarters. Such raids could have been valuable from both the practical and the psychological point of view. Col. Marchand provides this useful insight:

Jean-Pierre located various arms caches throughout Kigali. A UN officer accompanied him to MRND headquarters. In the basement there was indeed a stockpile of arms and ammunition, so we immediately sent a request to the NY office to carry out search operations. The response was negative. We weren't able to proceed with this type of operation because NY said this wasn't UNAMIR's mandate. Consequently, we weren't allowed to touch the arms caches, and UNAMIR lost a great deal of credibility in the field. Around the time people began to make fun of UNAMIR. They distorted its French acronym "MINUAR" to "MINUA," which as far as I know means "moving the mouth" in the Kinyarwanda language, which meant that UNAMIR talked big, but didn't act.[72]

Because UNAMIR did not take action on the known weapons caches, which were blatant violations of the Arusha Accords and its terms of reference, UNAMIR lost a large measure of support and the confidence of the population. At the very least, had the issue of weapons locations been pursued, UNAMIR would have been in a better position to make access to them more difficult once the genocide began.

In general, had the UN applied a number of the above measures to bring fear into the minds of the genocide plotters, the fate of the Rwandan people might have been very different. If these measures were not effective, then the UN would, at least, have been more experienced and knowledgeable about the plotters and their means, so that when the genocide did begin in earnest on 7 April, the UN would have been better prepared to recognize it and counteract it with force.

Preventive Measures After 6 April

The quick involvement of 400 excellent paratroopers may have saved the situation.- Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali, November 1994[73]

It is widely accepted that the United Nations could have taken steps soon after the genocide began to prevent much of the senseless mass killing that followed. But, again, high-ranking officials of both the UN and member-states, particularly the United States, failed to recognize and publicly declare the genocide even as tens of thousands were being slaughtered. Early recognition would have focused more international attention on the horrors in Rwanda, increased pressure by NGOs and an outraged public to stop the killings immediately, and caused the Security Council to strengthen UNAMIR at an early stage. Instead, the systematic killing of Tutsis was inaccurately described as "ethnic violence," the inevitable consequence of the civil war between the RPF and the FAR. On 21 April, two weeks into the genocide, the Security Council, in UN Resolution 912, altered the mandate of UNAMIR not to stop the genocide, but to "act as an intermediary between the parties in an attempt to secure their agreement to a cease-fire." The genocide in Rwanda was portrayed by the UN as random outbreaks of violence between Hutus and Tutsis, when in fact the violence was centrally orchestrated, and directed by the extremists primarily against Tutsis.