by Dennis J.D. Sandole

INTRODUCTION

This is the most recent published report on an ongoing research project to monitor developments in post-Cold War Europe. It involves efforts to solicit and analyze the views of (primarily) heads of delegation to the most inclusive trans-Atlantic/pan-European peace and security system, comprising all the former enemies of the Cold War and neutral and nonaligned: the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), formerly the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), based in Vienna, Austria.1

The specific research problem addressed here is twofold: first, to explore to what extent findings generated by my initial study of CSCE negotiators' perceptions of various peace and security issues in 19932 would be replicated by my second round of interviews with OSCE negotiators in 1997. Second, it will examine how those perceptions may have shifted between 1993 and 1997, that is, from two years before to two years after the Dayton Peace Accords stopped the wars in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1995.

The overall project, including this article, is deemed significant because other than the work of Terrence Hopmann,3 little seems to have been done to solicit from CSCE/OSCE negotiators themselves their views on peace and security. This represents a significant gap in the international peace and security literature, considering the nature of the CSCE/OSCE and the fact that its members are among those tasked with creating peace and security systems for post-Cold War Europe, such that, among other things, "future Yugoslavias" might be prevented.

BACKGROUND TO THE PROJECT: THE CSCE/OSCE

("HELSINKI PROCESS")

The CSCE came into existence at the height of the Cold War. Its initial negotiations started in 1972 and ended in 1975, with the Helsinki Final Act establishing a basis for cooperative relations between the two rival treaty organizations of the Cold War period - the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and Warsaw Treaty Organization (WTO) - plus the neutral and nonaligned states.4

Over the years, there have been numerous review and summit meetings of the CSCE further refining and implementing provisions based on the three "baskets" of the Helsinki Final Act. Originally, the three baskets were Basket 1: Security Concerns; Basket Two: Environmental and Economic Concerns; and Basket 3: Humanitarian Concerns. By the end of the Cold War, these had evolved into, first, the political and military, second, the economic and environmental, and third, the humanitarian and human rights aspects of overall, comprehensive security. In other words, as I have indicated elsewhere, the CSCE/OSCE had started the process of "paradigm-shifting," away from a narrow, "zero-sum" focus on national security to a broad, "nonzero-sum" emphasis on common security.5

Leading up to this development, two of the baskets, Basket 1 with its emphasis on confidence- and security-building measures (CSBMs) and Basket 3 with its emphasis on human rights, helped bring about the end of the Cold War.6 Paradoxically, the otherwise "revolutionary" developments that helped bring about the end of the Cold War, including the further "institutionalization" of the CSCE into the OSCE on 1 January 1995,7 took place within the same time frame that one particular consequence of the ending of the Cold War also occurred: the implosion of Yugoslavia into brutal, genocidal warfare.

CONFLICT RESOLUTION THEORY: SOME HELPFUL CONCEPTS

To help "make sense" of anything, one requires appropriate frameworks or perspectives to confer meaning upon what we are examining, lest it remain "any" thing. In short, we need theory. Accordingly, this article uses concepts relevant to how the international community as well as the parties themselves might have dealt - and could still deal - with the violent ethnic conflicts of post-Cold War Europe.8

There are, for instance, competitive and cooperative approaches to conflict handling.9 Competitive approaches are power-based, adversarial, confrontational, and zero-sum ("win-lose"), associated with a Realpolitik approach to human relations and often with destructive outcomes. Cooperative approaches, on the other hand, are nonpower-based, nonadversarial and positive-sum ("win-win"), associated with an Idealpolitik approach and often with constructive outcomes.10

Related to the various approaches to conflict handling are different images of peace; e.g., negative and positive peace.11 Negative peace is what most people, including diplomats, mean when they talk about "peace": the absence - either through prevention or cessation - of hostilities. There is nothing wrong with "peace" in this sense, but it is not the whole picture. Positive peace, which helps to complete the picture, is the absence of structural violence, i.e., systems in which members of certain ethnic, religious, racial and/or other groups - solely because of their involuntary membership in those "minority groups" - have unequal access to economic, political, social and other resources typically presided over and enjoyed by members of mainstream groups.12 Positive peace is also the absence of cultural violence, which legitimizes and makes acceptable structural violence in the "popular culture" of mainstream groups.13

Different approaches to conflict handling associated with different images of peace are also linked to the nature of any involved third party, that is, whether they are track-1 or track-2 actors. Track 1 deals with governmental, and track 2 with nongovernmental actors, mechanisms and processes at either the intra- or international level.14

Putting these three sets of concepts together, track-1 warriors and diplomats typically operate within a Realpolitik framework where they use various kinds and degrees of competitive means to achieve and maintain negative peace. A major objective of the project discussed here has been to explore, with CSCE/OSCE negotiators, to what extent, if any, there has been a shift away from a unidimensional Realpolitik paradigm comprised of track-1 competitive approaches to negative peace, and toward a multidimensional system comprised of these plus Idealpolitik-based, track-2 cooperative approaches to positive peace. In other words, has there been a shift away from a "cognitively simplistic" approach to one more likely to "capture the complexity" of the identity-based conflicts of the post-Cold War era?15

OVERARCHING RESEARCH DESIGN

What is significant about the 1993 (CSCE) and 1997 (OSCE) interviews is that the 1993 survey occurred two years after the onset of war in former Yugoslavia and two years before the Dayton Peace Accords stopped the wars in Bosnia; while the 1997 survey took place two years after Dayton stopped the wars, and two years before the crisis in Kosovo reached the "boiling point," ushering in massive NATO intervention to stop the Serb-led genocidal campaign against the Kosovar ethnic Albanians.16

This is structurally similar to a "true" experimental design, characterized by "before" and "after" observations on a given variable, but without a "control group." Since basically the same "closed-ended" questions were asked in 1997 as in 1993, another objective of the CSCE/OSCE project has been to explore to what extent, if any, the Dayton peace process "seemed" to influence respondents' views on peace and security in post-Cold War Europe. In this regard, the Dayton peace process and the return of "negative peace" to Bosnia, could be viewed as a "natural" or "social experiment," "where the changes [in a situation were] produced, not by the scientist's intervention [in a laboratory], but by that of the policy maker or practitioner [in the real world]."17

THE 1993 CSCE SURVEY

During June-July 1993, some 15 months after the Yugoslavian wars spilled over from Croatia into Bosnia-Herzegovina, the author travelled to Vienna (as a NATO Research Fellow) to elicit from (primarily) heads of delegation of the (then) 53 participating states of the CSCE, their views on peace and security in Cold War Europe, including "what went wrong in former Yugoslavia?"

1993 CSCE Research Design

Based upon information provided by the US Information Service (USIS) in Vienna prior to arriving there in June 1993, I had written letters to the heads of all the delegations, informing them that I was a former member of the US delegation to the CSBMs Negotiations and that I would be coming to Vienna to pursue this project. Upon arrival in Vienna, I contacted all of the 53 delegations, and by the middle of July, had succeeded in interviewing 32 of them from 29 participating states, including:18

(a) 13 NATO states: Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Turkey, United States and United Kingdom;

(b) 6 neutral and nonaligned states (NNA): Austria, Finland, Ireland, Liechtenstein, San Marino and Switzerland;

(c) 3 former Yugoslav republics (FYug): Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia;19

(d) 5 non-Soviet members of the Warsaw Pact (NSWP): Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia; and,

(e) 2 former Soviet republics (FSU): Russian Federation and Ukraine.

For a variety of reasons, I was unable to interview individuals from all 53 participating states. Instead, I interviewed persons from convenience samples20 of the five main groupings, with some samples being more representative than others:

(a) NSWP: 5/6 (83 percent);

(b) NATO: 13/16 (81 percent);

(c) FYug: 3/4 (75 percent);21

(d) NNA: 6/11 (55 percent); and

(e) FSU: 2/15 (13 percent).22

Interviews comprised 15 closed-ended and 12 open-ended questions.23 The closed-ended questions reflected Likert scale-type responses; e.g., strongly agree (SA), Agree (A), Mixed Feelings (MF), Disagree (D), and Strongly Disagree (SD), where SA=5, A=4, MF=3, D=2, and SD=1.24 Hence, the higher an interviewee's score on a particular item, the more in agreement she or he was with that item. To facilitate comparisons between the five contrasting samples, "group mean scores" were computed for each of the 15 closed-ended questions.

The interviews followed a schedule-structured format, where all interviewees were asked the same questions, with the same wording, and in the same order,25 with the one exception that, on occasion, additional information was provided to some subjects to make a question clearer.26 The interviews usually were conducted in delegation offices, and lasted between one and three hours. (Given the busy schedules of the interviewees, the great majority of whom were delegation heads, this was rather remarkable.)

1993 CSCE Research Results -

The gist of each of the 15 closed-ended questions and responses to them are indicated below:

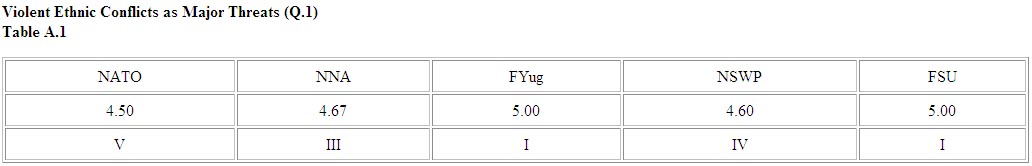

Question 1 presented the proposition that violent ethnic conflicts, such as those in former Yugoslavia (Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina) and the former Soviet Union (Nagorno-Karabakh, Moldova, Georgia) would be among the major threats to international peace and security in the post-Cold War era. Mean responses were:27

Violent Ethnic Conflicts as Major Threats (Q.1)

Table A.1

Clearly, all five groupings were fairly high in agreeing that violent ethnic conflicts would be among the major threats to international peace and security in the post-Cold War era. What is especially interesting is that the FYug and FSU - two areas with a preponderance of ongoing and potential violent ethnic conflict - were tied for first place. NATO, on the other hand, many of whose members seemed disinclined to deal effectively with such conflicts, occupied fifth and final place.

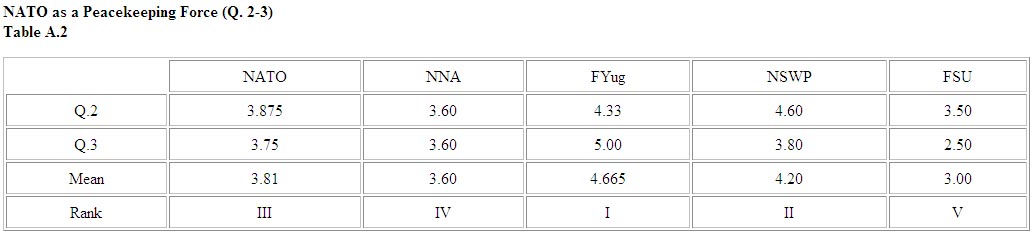

On the issue of whether NATO could play an effective role in responding to such conflicts (question 2) and whether NATO should have been used earlier in a peacekeeping role in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina (question 3), mean responses were:

NATO as a Peacekeeping Force (Q. 2-3)

Table A.2

The most enthusiastically in favor of NATO peacekeeping intervention, in general and specifically in the case of the Yugoslav ethnic wars, were, perhaps not surprisingly, the FYug. The least in favor, again, perhaps not surprisingly, were the delegates of the FSU, where the Russian Federation-based CIS would prefer to do its own peacekeeping in "near abroad" areas.

Interestingly, it was the newly independent states and/or democracies of the FYug and the NSWP, which might want Western (e.g., NATO) assurances against the threats implicit in a revival of Russian hegemony, that occupied first and second place.

Separating the two questions, the NSWP, which had been (and remains) enthusiastic about fairly early admission into NATO, were the most enthusiastic about NATO peacekeeping intervention in violent ethnic conflicts in general (question 2), while the FYug were the most enthusiastic about NATO peacekeeping in the former Yugoslavia (question 3).

NATO was clearly not too keen on conducting peacekeeping operations in violent ethnic conflicts, in the former Yugoslavia or anywhere else. The NNA, which occupied fourth place between NATO (third place) and the FSU (fifth place), were even less supportive of NATO's use in this way.

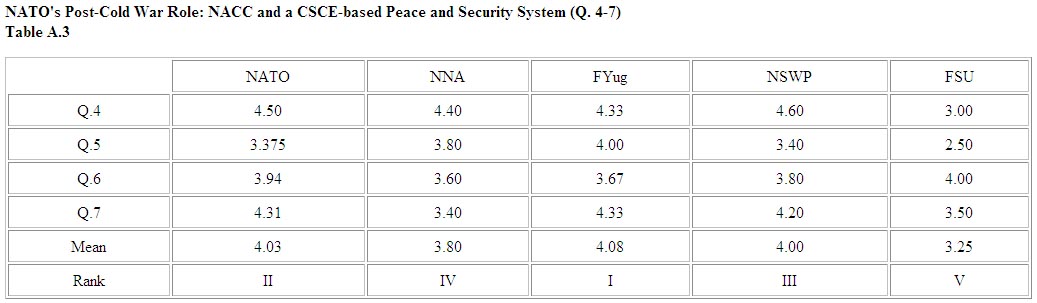

Question 4 dealt with the issue of whether NATO should take into account its former WTO adversaries in dealing with issues of common security. Question 5 was concerned with whether the North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC), created by NATO, could become the basis of a post-Cold War security system inclusive of all former Cold War adversaries. Question 6 dealt with whether, if NACC did develop in that way, it should do so in the context of the CSCE. And, assuming that a peace settlement was reached among the warring Serbs, Croats and Slavic Muslims in the former Yugoslavia, question 7 was concerned with whether the US and Russian Federation should play a role in the anticipated NATO-managed peacekeeping force that would be sent into the area. Mean responses were:

NATO's Post-Cold War Role: NACC and a CSCE-based Peace and Security System

(Q. 4-7)

Table A.3

The most enthusiastically in favor of NATO pursuing a post-Cold War role at variance with Cold War Realpolitik were the FYug (first place), NATO itself (second place) and the NSWP (third place), with hardly a difference between their "grand mean" scores. The least in favor were the NNA (fourth place) and the FSU (fifth place).

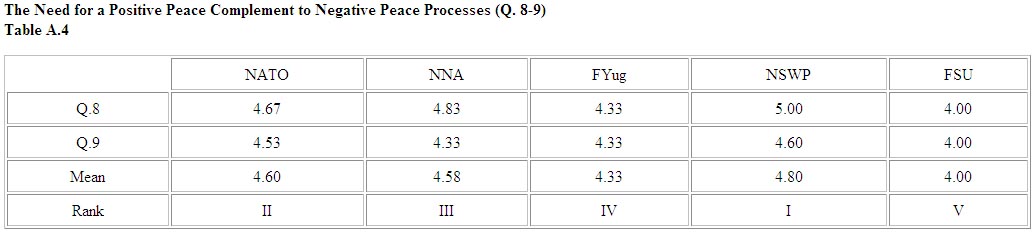

Question 8 dealt with the issue of whether, beyond the threatened or actual use of force to "keep the peace," there was a need to deal with the issues that underlay the violent expression of conflict in former Yugoslavia. Question 9 dealt with the proposition that, without successfully dealing with the issues underlying the use of violence, external intervention to forcibly keep the warring factions apart would not, by itself, lead to a resolution of the conflict. Mean responses were:

The Need for a Positive Peace Complement to Negative Peace Processes (Q.

8-9)

Table A.4

All groupings agreed that there was a need for a positive peace complement to negative peace processes. The NSWP occupied first place, with NATO in second place and the NNA very closely behind in third place, followed by the FYug and FSU in fourth and fifth place, respectively.

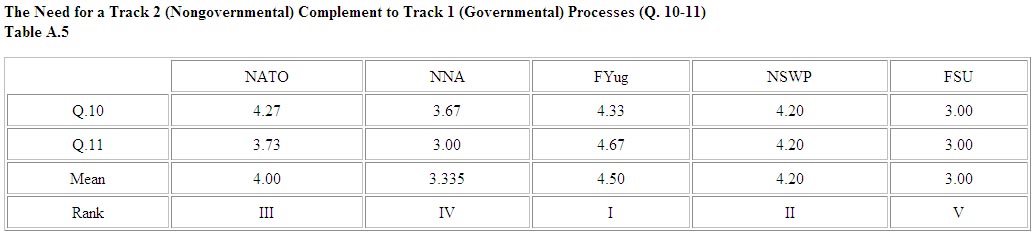

Question 10 dealt with the issue of whether, in cases of violent ethnic conflict, there was a need for liaison and integration between military peacekeeping agencies (e.g., UN, NATO/NACC) and conflict resolution organizations, which could include NGOs, such as former President Carter's center at Emory University. The former would work to separate the warring factions to allow a "cooling-off period," and the latter would facilitate resolution of the underlying problems. Question 11 dealt with the claim that, although many mechanisms existed for military peacekeeping, there was a need for more conflict resolution mechanisms. Mean responses were:

The Need for a Track 2 (Nongovernmental) Complement to Track 1 (Governmental)

Processes (Q. 10-11)

Table A.5

The FYug were most enthusiastically in favor of track 2 complements to track 1, perhaps because, prior to the Dayton Peace Accords, track 1 had not been successful in the former Yugoslavia, especially in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The NSWP, not far from the "front," were in second place. NATO followed not far behind in third place; while the NNA and FSU, at fourth and fifth place, respectively, seemed least enthusiastic.

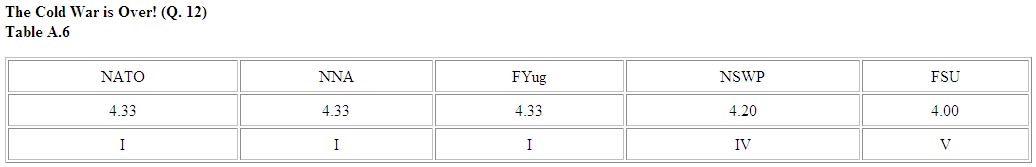

Question 12 dealt with whether, despite the problems faced by Russian President Yeltsin and others in the former Soviet Union, the Cold War was basically over. Mean responses were:

The Cold War is Over! (Q. 12)

Table A.6

All groupings agreed that the Cold War - "as we knew it" - was over, with NATO, the NNA and FYug tied for first place, and the NSWP and FSU in fourth and fifth place, respectively.

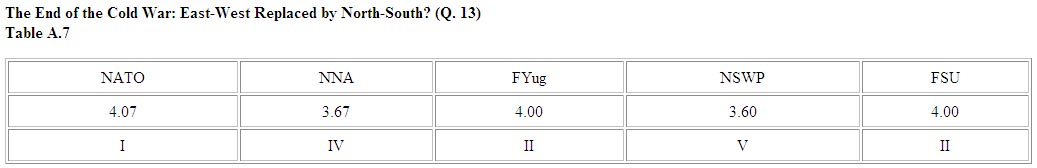

Question 13 dealt with whether there was a perception developing in the "Third World" that the "New World Order" meant nothing more than that East-West had been replaced by North-South as the dominant axis of international conflict. Mean responses were:

The End of the Cold War: East-West Replaced by North-South? (Q. 13)

Table A.7

NATO occupied first place here, with the FYug and FSU tied for second place. The NNA and NSWP occupied fourth and fifth place, respectively.

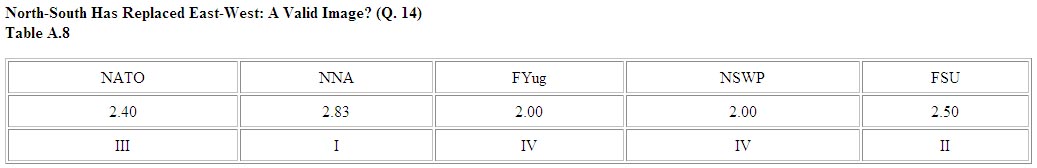

To the extent that such a belief had developed in the Third World, question 14 was concerned with its validity. Mean responses were:

North-South Has Replaced East-West: A Valid Image? (Q. 14)

Table A.8

All groupings disagreed that the above perception was valid, with the FYug and NSWP disagreeing the strongest (i.e., in terms of the rankings, being the furthest away from agreement), followed by NATO, the FSU and the NNA.

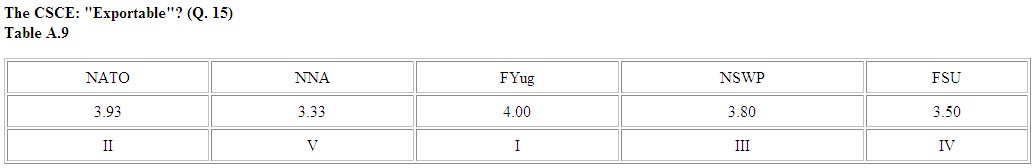

Finally, on the issue of the "exportability" of the CSCE to other regions (question 15), mean responses were:

The CSCE: "Exportable"? (Q. 15)

Table A.9

There was not too much agreement here: the FYug occupied first place, with NATO and the NSWP not too far behind in second and third place, respectively. The FSU and NNA, in fourth and fifth place, respectively, were the furthest away from agreement.

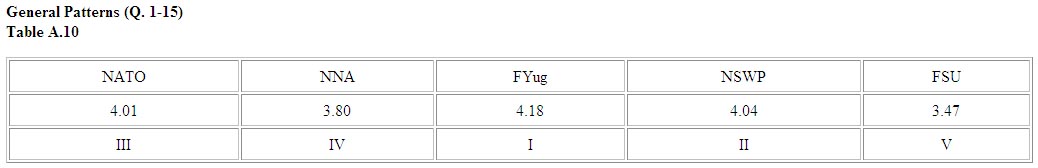

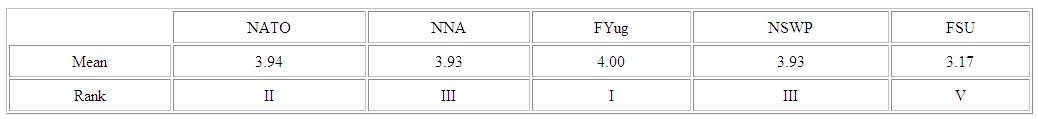

Looking at Tables A.1-A.9 together, a clear pattern emerged from the 1993 data: quite often first, second and third rankings went to the FYug, NSWP and NATO, while fourth and fifth rankings went to the NNA and FSU. This corresponds with the grand means for all 15 closed-ended questions combined, as indicated in Table A.10.

General Patterns (Q. 1-15)

Table A.10

What is also interesting here is that, often, the FYug, NSWP and NATO were fairly close together in scores, followed by the NNA and then by the FSU. According to the respondents in the 1993 CSCE study, therefore, three distinct metacultures may have been developing in the new Europe: one comprising the former Yugoslav republics together with the former non-Soviet members of the Warsaw Pact and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization; another comprising the neutral and nonaligned and the third comprising the former Soviet Union.

Also, the FYug-NSWP-NATO aggregate appears to have been more "flexible" than the other groupings: it was further away from Cold War Realpolitik and closer to an Idealpolitik framework than were the NNA and FSU. Specifically, compared to the NNA and FSU, the FYug-NSWP-NATO cluster was more in favor of NATO and the NACC developing into a transAtlantic, pan-European security component within the context of the CSCE (questions 4-7); more in favor of complementing negative-peace with positive-peace processes (questions 8-9); and more in favor of complementing track 1 with track 2 processes (questions 10-11).

Further, the results suggested, perhaps surprisingly, the continuation of a Cold War-era loose bipolar system, at least in terms of beliefs and values, with the West (NATO and those who want to be in, or are otherwise supportive of, NATO [the NSWP and FYug]) constituting one pole and the East (the Soviet successor states) the other, with the neutral and nonaligned in between.

In any case, these results were clearly tentative, in part, because I interviewed nonrepresentative samples amounting to 55 percent of the CSCE delegations, with the FSU grossly underrepresented. There was a need, therefore, to go back out into the field to get closer to a "population sample," and, among other things, test the 1993 findings as hypotheses within an improved data setting.

THE 1997 OSCE SURVEY

A Fulbright OSCE Regional Research Scholarship allowed the author to return to Vienna during May-August 1997, to conduct a second round of interviews. Because of the similarity between the "closed-ended" questions for both the 1993 and 1997 surveys, this allowed me to explore the external validity of the findings of the 1993 CSCE study:28 the extent to which the findings for the CSCE in 1993 were applicable to the OSCE in 1997.

Also, between the two surveys, the wars in Bosnia-Herzegovina had been brought to an end by the Dayton peace process and the efforts largely of US negotiator Richard C. Holbrooke in summer-autumn 1995.29 Hence, this phase of the project allowed me to view the Dayton peace process and the return of negative peace to Bosnia, as a "natural" or "social experiment," where, again, real life itself, and not the experimenter, "intervenes" into the lives of participants in such a way that their responses to certain issues could be affected.

1997 OSCE Research Design

Once again, prior to departing for Vienna I wrote letters to the heads of the OSCE delegations, informing them of my objectives: to conduct interviews similar to those that I had conducted in 1993. By the end of August, I had interviewed 47 individuals from 46 of the 55 participating states:

(a) 15 NATO states: Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, United Kingdom and United States;

(b) 9 neutral and nonaligned states (NNA): Austria, Cyprus, Finland, Holy See, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Malta, Sweden and Switzerland;

(c) 4 former Yugoslav republics (FYug): Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia and Slovenia;30

(d) 6 non-Soviet members of the Warsaw Pact (NSWP): Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia; and,

(e) 12 former Soviet republics (FSU): Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Russian Federation, Turkmenistan and Ukraine.31

Clearly, this was a more representative sample than achieved in 1993:

(a) NSWP: 6/6 (100 percent);

(b) NATO: 15/16 (94 percent);

(c) NNA: 9/11 (82 percent);

(d) FYug: 4/5 (80 percent); and,

(e) FSU: 12/15 (80 percent).

Although still a "convenience sample," 46 interviewed delegations out of a population of 55 OSCE participating states nevertheless represented 84 percent of that population, which was frustratingly close to being a "population sample."32 I also interviewed five officials of the OSCE Secretariat (whose responses are included in this report) and the representatives of four OSCE Partners for Cooperation: Japan, Korea, Morocco, and Egypt (whose views will be included in subsequent reports on the project).

Again, I conducted basically schedule-structured interviews, comprising closed- and open-ended questions, usually in delegation offices, with interviews lasting between one and three hours. The closed-ended questions, with some exceptions, were almost the same as those for 1993, including the Likert-type response structure. The exceptions dealt with updated revisions of text and recent and future developments, such as NATO enlargement and the withdrawal of the NATO-led Stabilization Force (SFOR) from Bosnia, then planned for June 1998.33

1997 OSCE Research Results and Comparisons with the 1993 CSCE Findings

Once again, mean responses to the questions were computed to facilitate comparisons between the groups, and with the 1993 findings. Question 1 dealt again with the issue of whether violent ethnic conflicts, such as those in former Yugoslavia and the former Soviet Union, would be among the major threats to international peace and security in the post-Cold War era. Mean responses were:

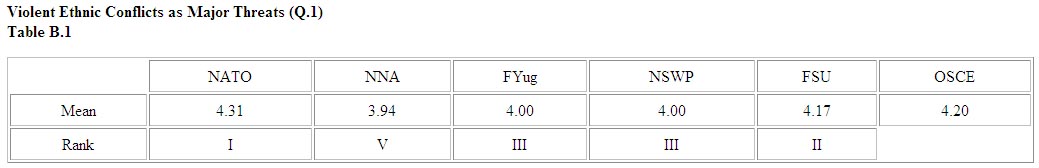

Violent Ethnic Conflicts as Major Threats (Q.1)

Table B.1

Basically, there was agreement "across the board" here, with NATO in first place, followed by the FSU, NSWP and FYug and NNA, with the OSCE subsample close to the FSU position.34 Given NATO's continuing peacekeeping experience in Bosnia, and the Russian-Chechen war and other ethnic conflicts in the FSU, NATO's and the FSU's relatively high rankings are perhaps understandable. In any case, the differences between the five groupings are not substantial.

Comparing these to the corresponding figures for 1993, there was less agreement in 1997 than in 1993 that ethnic conflicts would be among the major threats to international peace and security, the greatest difference across the two time periods being recorded for, perhaps surprisingly, FYug, which dropped from 5.00 to 4.00.

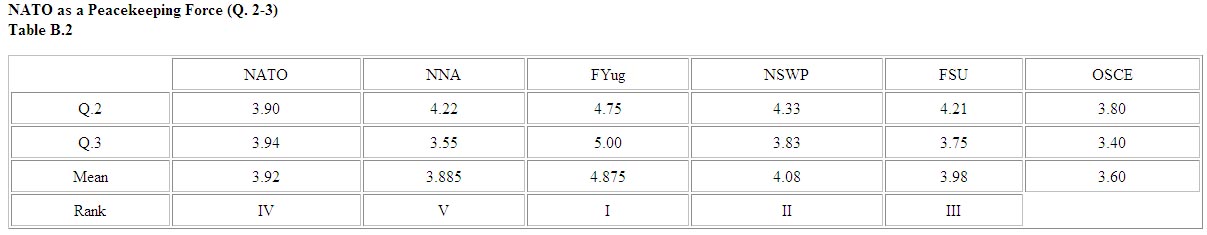

On the issue of whether NATO could play an effective role in responding to some of these conflicts (question 2) and whether NATO should have been used earlier in a peacekeeping role in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina (question 3), mean responses were:

NATO as a Peacekeeping Force (Q. 2-3)

Table B.2

FYug scored the highest here, followed by the NSWP, FSU, NATO and NNA, with the differences among the latter four not being very substantial. The OSCE Secretariat scored lower than the last-placed NNA. Given that warfare in Bosnia was brought to a halt by NATO intervention, the clear dominance of the FYug here may be understandable. With the exception of the NSWP, the "grand mean" responses to questions 2 and 3 for 1997 are all higher than those for 1993, but with FYug clearly in first place for 1993 as well. This overall increase in scores across the two time periods may be a reflection of NATO's "track record" in achieving and maintaining the "negative peace" in Bosnia.

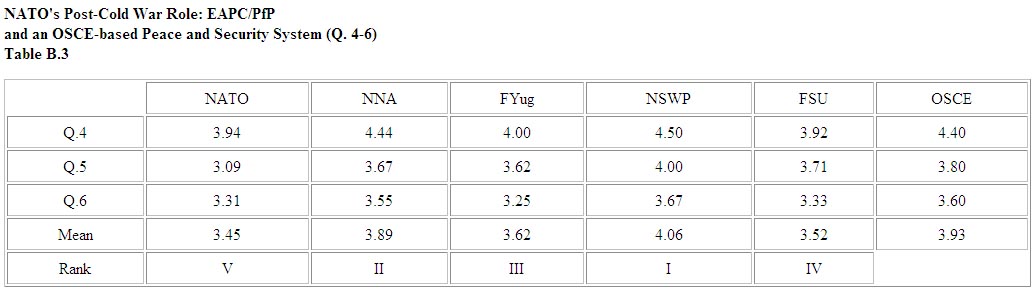

Question 4 dealt with the issue of whether NATO, when enacting a peace-making role, should continue to include its former WTO adversaries in dealing with issues of common security. Question 5 asked whether the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC), which had just replaced the North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC), and the Partnership for Peace (PfP) . a series of bilateral relationships between NATO and former WTO countries within the framework of NACC/EAPC . could develop into a post-Cold War security system for Europe, inclusive of all former Cold War adversaries and the neutral and nonaligned. Question 6 asked whether, if the EAPC and PfP did develop into a post-Cold War security system, they should do so in the context of the OSCE. Mean responses were:

NATO's Post-Cold War Role: EAPC/PfP

and an OSCE-based Peace and Security System (Q. 4-6)

Table B.3

Only the NSWP went beyond the 4.00 "grand mean" level. Major problems here for many respondents were the future status of the OSCE and/or NATO's autonomy and freedom of maneuver. For example, first, if the EAPC and PfP did develop into a post-Cold War security system, what was the point of having the OSCE? Second, if the EAPC and PfP developed into a security system "in the context of the OSCE," would they be subordinate to the OSCE? Interestingly, NATO and the FSU are ranked at fifth and fourth place, respectively, in their mean responses.

This distribution of "grand-mean" responses is not too dissimilar from what occurred for questions 4, 5 and 6 for the 1993 study.35 Then only the FYug barely broke ground at the 4.00 level, with the others being below it, but with the "grand means" for the NNA and NSWP being nearly identical to their 1997 levels.

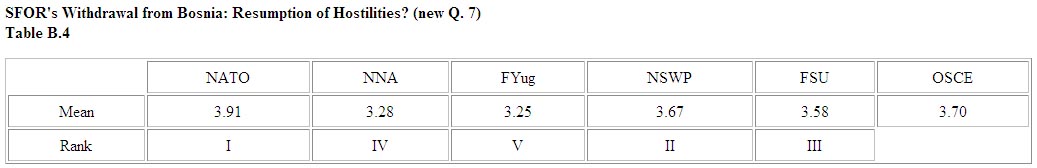

A new question 7 for the 1997 study dealt with the proposition that if NATO, PfP and others participating in SFOR in Bosnia started to withdraw their forces in 1998 as then planned, then warfare would be likely to resume between the Bosnian Serbs, Croats and Muslims. Mean responses were:

SFOR's Withdrawal from Bosnia: Resumption of Hostilities? (new Q. 7)

Table B.4

These are interesting findings, especially given the debate, and decisions within NATO and non-NATO countries participating in SFOR, to extend SFOR beyond the June 1998 deadline. The common assumption was that to withdraw it in June would be to put at risk the fragile "negative peace" in Bosnia. By contrast, all groupings were below 4.00, but with NATO nearly at that level, recording strongest agreement and, perhaps surprisingly, the FYug recording weakest agreement. The OSCE comes closest to the NSWP, which is in second place behind NATO.

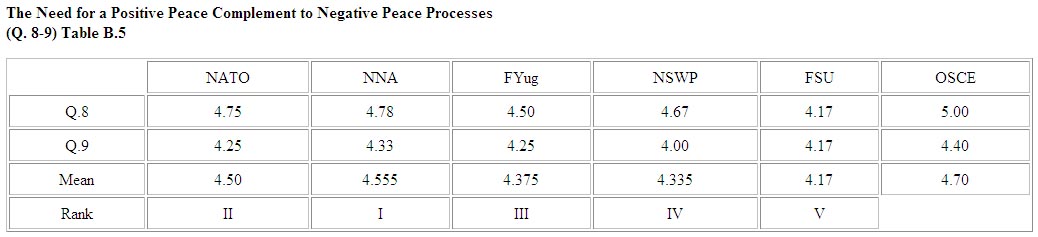

Question 8 dealt with the proposition that, beyond the threatened or actual use of force to "keep the peace," there is a need to deal with the issues underlying the violent expression of conflict in former Yugoslavia. Question 9 tested the proposition that, without successfully dealing with the issues underlying the use of violence, external intervention to forcibly keep the warring factions apart would not, by itself, lead to a resolution of the conflict. Mean responses were:

The Need for a Positive Peace Complement to Negative Peace Processes

(Q. 8-9) Table B.5

The responses here were rather high across the board, with the NNA being in first place, followed immediately by NATO and the FYug and NSWP, with the FSU in fifth place. The OSCE were even higher than the first-placed NNA. These findings are remarkably similar to those obtained for the 1993 study, where all groupings were fairly high in agreement, with NATO again in second place and the FSU in fifth place. The 1993 "grand means" for NATO, the NNA and the FYug are barely distinguishable from their corresponding means for 1997. The major difference was that the NSWP ranked first for 1993, in contrast to the NNA for 1997.

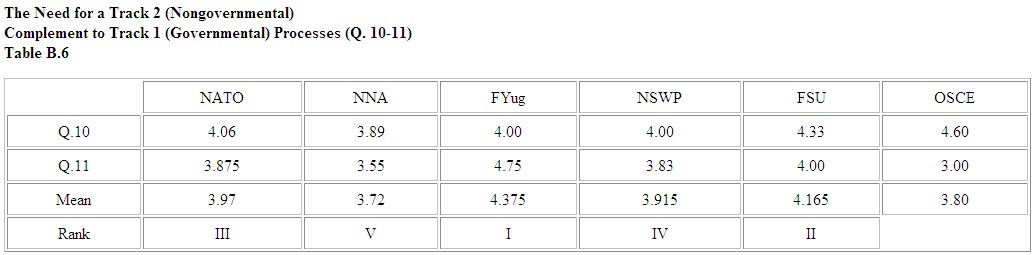

Question 10 dealt with the issue of whether, in the violent, often ethnic-based, conflicts of the post-Cold War world, states and IGOs should, to the extent possible, work together with humanitarian and conflict resolution NGOs as part of an integrated whole. Question 11 examined the proposition that, while there were many peacekeeping mechanisms, there was a need for more peacemaking and peacebuilding mechanisms. Mean responses were:

The Need for a Track 2 (Nongovernmental)

Complement to Track 1 (Governmental) Processes (Q. 10-11)

Table B.6

There was a mix of results here, with the FYug clearly in first place and the FSU in second place, with both above 4.00. NATO was not too far behind in third place, with the NSWP close behind in fourth place and the NNA clearly in fifth place. Interestingly, the OSCE was closest to the NNA position. A major problem here for many respondents was question 11. Many thought there were already sufficient mechanisms; they were just not being used at all or if they were, not too efficiently.

The corresponding findings for 1993 were not too dissimilar. The FYug was again in first place, and NATO was again in third place, its "grand means" for the two time periods being nearly identical.

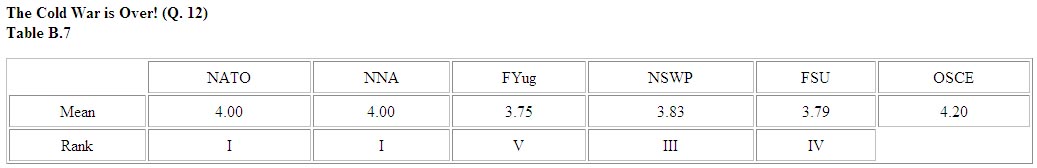

Question 12 dealt with whether, despite the problems faced by Russian President Yeltsin and others in the former Soviet Union, the Cold War was basically over. Mean responses were:

The Cold War is Over! (Q. 12)

Table B.7

NATO and the NNA co-occupied first place here, followed by the NSWP, FSU and FYug, with scores for the latter three all under 4.00 and nearly identical, and the OSCE grouping achieving the highest score of all. The corresponding findings for 1993 were all at 4.00 or above, but with nearly identical rankings: NATO and the NNA shared primacy with the FYug, followed by the NSWP and FSU. The "distance" recorded across the two time periods was greatest for the FYug, followed by the NSWP, NATO and the NNA - the latter two, interestingly enough, recorded exactly the same mean responses for 1993 [4.33] as well as for 1997 [4.00] - and the FSU. The obvious conclusion to draw here is that the OSCE representatives, especially those from the FYug, FSU and NSWP, appeared less sanguine in 1997 than they did in 1993 that the Cold War was over. This may have been a possible consequence of the brutal Russian-Chechen war fought during 1994-96.

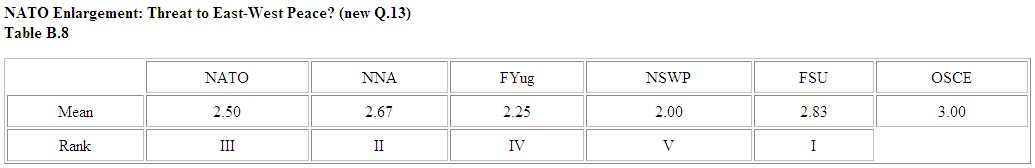

A new question 13 dealt with the proposition that NATO enlargement could put at risk the post-Cold War peace that had developed between East and West. Mean responses were:

NATO Enlargement: Threat to East-West Peace? (new Q.13)

Table B.8

All five groupings disagreed with this, but, perhaps not surprisingly, the FSU disagreed the least (i.e., in terms of the rankings, were the closest to "agreement"), followed by the NNA, NATO, the FYug and NSWP. In terms of the rankings, the latter was the furthest away from "agreement" - not surprising, perhaps, given that the NSWP states were (and remain) among the first tier of potential new NATO members. The OSCE were closer to, and even higher than, the FSU position and therefore, even closer to agreement than the otherwise first-ranked FSU. Perhaps the "Founding Act" between NATO and the Russian Federation - giving Russia a "voice but not a veto" in NATO deliberations - and the creation of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council, strengthening the Partnership for Peace, in spring 1997, helped mute resistance to NATO enlargement.

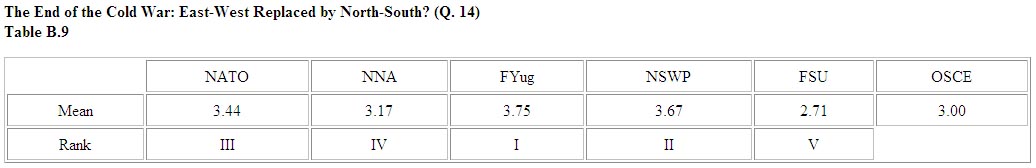

Question 14 dealt with whether there was a perception in the developing world that the "New World Order" meant nothing more than that East-West had been replaced by North-South as the dominant axis of international conflict. Mean responses were:

The End of the Cold War: East-West Replaced by North-South? (Q. 14)

Table B.9

All responses were below 4.00 here, but with the FYug recording highest relative agreement, followed by the NSWP, NATO, NNA and finally by the FSU which, in absolute terms, was in disagreement with the proposition. The OSCE fell between the fourth-placed NNA and the fifth-placed FSU. A major problem with this question was that, often, respondents interpreted it to be asking them if they themselves agreed or disagreed that East-West had been replaced by North-South, instead of asking them if they agreed or disagreed that there was a perception in the developing world that East-West had been replaced by North-South.

These figures were somewhat different from those recorded for 1993, which were generally higher, and where NATO was in first place, followed by the FYug and FSU, the NNA and NSWP. There were, however, some similarities across the two time periods. Although its rankings were nearly reversed, the figures for the NSWP were nearly identical, while the rankings for the FYug, but not its figures, were nearly the same.

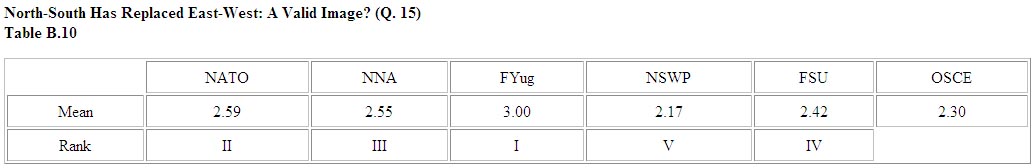

Question 15 dealt with whether, if such an image had developed, it was valid. Mean responses were:

North-South Has Replaced East-West: A Valid Image? (Q. 15)

Table B.10

Other than the FYug, which barely registered at the 3.00 level ("mixed feelings"), all the other groupings, including the OSCE, were below 3.00, effectively disagreeing with the proposition that the view that East-West had been replaced by North-South was valid. The corresponding figures for 1993 were not too dissimilar: all were below 3.00, and for both time periods, NATO and the FSU were fairly close together.

TESTING THE 1993 HYPOTHESES IN THE CONTEXT OF THE 1997 STUDY

So, how did the 1993 findings hold up in the 1997 study? Was there again evidence suggesting the development of three peace and security "metacultures" in post-Cold War Europe, with the neutral and nonaligned (NNA) in between the "West" (the FYug-NSWP-NATO cluster) and the "East" (the Soviet successor states/FSU), and with the FYug-NSWP-NATO cluster further away from a Realpolitik and closer to an Idealpolitik framework than were the NNA and FSU? Were the shifts observed between 1993 and 1997 significant, perhaps influenced by the Dayton peace process? Or - more complexly - was there evidence for both: confirmation of the 1993 findings and of significant deviation from them?

Persistence of the Three "Metacultures"?

An examination of the individual mean responses to questions 1-15 for both 1993 and 1997 indicates that evidence for the 1993 finding of the possible existence of three "metacultures" appears in seven questions for 1993 (Questions 2, 3, 7, 9, 10, 11, 15). However, it is unequivocal in only three of them (Questions 2, 3, 10). The others involved either tied scores for the NNA and FYug (Question 9), or for the NNA and FSU (Question 11), or reversed rankings for the NNA and FSU from fourth and fifth place, to fifth and fourth place, respectively (Questions 7, 15). By contrast, evidence for the possible existence of three metacultures appears in only two questions for 1997 (Questions 3, 14), and in one of those (Question 3) with the order for the NNA and FSU reversed. So, at the disaggregated level, we can conclude that the tentative 1993 finding that three "metacultures" may have been developing in post-Cold War Europe, has not been replicated by the 1997 data. In relative contrast to the 1993 findings, for 1997 different groupings came down on different themes in different ways.

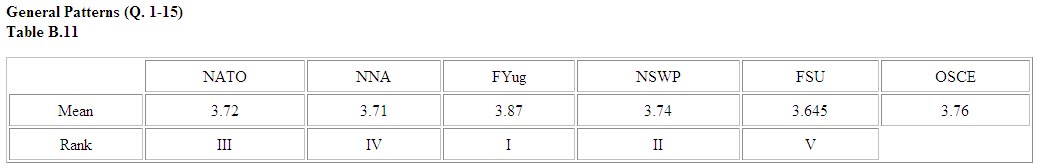

General Patterns (Q. 1-15)

Table B.11

On the other hand, when the mean responses for 1997 are combined, as in Table B.11, and compared with those for 1993 in Table A.10, the 1997 figures for the groupings rank in exactly the same order as do the 1993 figures. At the aggregate level, therefore, the 1997 findings are suggestive of the three "metacultures." But the figures also tend to be fairly close together, suggesting that in 1997 the 46 sampled delegations of the OSCE were closer to sharing in a "community of values" than were the 29 sampled delegations of the CSCE in 1993. This seems to have a lot to do with the relative success of NATO in achieving and maintaining "negative peace" in Bosnia since 1995.36

The findings over time, therefore, tend toward complexity. While there is some evidence to support the hypothesis of the three "metacultures," significant change also appears to have occurred in the mindsets of CSCE/OSCE negotiators between 1993 and 1997.

Change Over Time: 1993-97

OSCE representatives agreed less strongly in 1997 than did their CSCE counterparts in 1993 that violent ethnic conflict would be a major threat to international peace and security (question 1). With the exception of the NSWP, whose mean response went down, respondents agreed more strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that NATO could play an effective role in responding to some of these conflicts by providing peacekeeping forces (question 2). Respondents agreed more strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that NATO should have been used earlier in a peacekeeping role in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina (question 3). The exception in this case was the NNA, whose mean response went down, and the FYug, whose mean response remained at the same maximum level of 5.00.

However, respondents agreed less strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that, whatever peacekeeping role NATO plays in the future, it will have to continue to include its former Warsaw Pact adversaries in dealing with issues of common security (question 4). The exceptions here were the NNA and FSU, whose mean responses increased.

With the exception of the NSWP and FSU (whose responses increased), respondents agreed less strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that NATO's various mechanisms for reaching out to its former WTO adversaries, the NACC/EAPC and PfP, could develop into a post-Cold War security system, inclusive of all former adversaries and the neutral and nonaligned (question 5). All respondents agreed less strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that, if the NACC/EAPC and PfP did develop into a post-Cold War security system, it should do so in the context of the CSCE/OSCE (question 6).

Except for the NNA and NSWP, whose responses decreased, respondents agreed more strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that, beyond the threatened or actual use of force to "keep the peace," there was a need to deal with the issues underlying the violent expression of conflict in former Yugoslavia (question 8).

Respondents agreed less strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that, without successfully dealing with the issues underlying the use of violence, external intervention to forcibly keep the warring factions apart would not, by itself, lead to a resolution of the conflict (question 9). This was at variance with the NNA, whose responses remained the same, and the FSU, whose responses increased.

But for the NNA and FSU, whose responses increased, respondents agreed less strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that, in the violent, often ethnic-based, conflicts of the post-Cold War world, states and IGOs should, to the extent possible, work together with humanitarian and conflict-resolution NGOs as part of an integrated whole (question 10).

Respondents agreed more strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that, while there were many peacekeeping mechanisms, there was a need for more peace-making and peace-building mechanisms (question 11), the only exception being the NSWP, whose responses decreased. All respondents agreed less strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that the Cold War was over (question 12).

With the exception of the NSWP, whose responses increased, respondents agreed less strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that there was a perception in the developing world that the "New World Order" meant nothing more than that East-West had been replaced by North-South as the dominant axis of international conflict (question 13 [1993]/question 14 [1997]).

Finally, with the exception of the NNA and FSU, whose responses decreased, respondents disagreed less strongly in 1997 than in 1993 that this view that East-West had been replaced by North-South as the dominant axis of international conflict was an accurate perception (question 14 [1993]/question 15 [1997]).37

NATO Intervention: A Successful "Natural Experiment"?

The NATO intervention to end the wars in Bosnia in 1995, as a "natural experiment," may have resulted in the trends noted for Questions 1-4 and 9-11. That is, first, across the two time periods, CSCE/OSCE negotiators anticipated less ethnic conflict in the future as threats to international peace and security, perhaps because NATO had dealt successfully with a major instance of such conflict in Bosnia. Second, to the extent that such conflict existed, NATO should be involved in dealing with it, and sooner rather than later. However, NATO does not necessarily have to consult with those who might be friendly with the instigators of such conflict. Third, although it would be best for the international community to deal with the deep-rooted, underlying causes and conditions of such conflict, putting fires out forcefully without necessarily dealing with those causes and conditions may nevertheless lead to "resolution."

In the final analysis, however, while NATO can forcefully extinguish fires, it cannot do the "post-conflict recovery" on its own. Hence, there is a need for new mechanisms that go beyond peace-making, which for many interviewees had a coercive connotation ("that is what NATO does!"), and beyond peacekeeping, toward peace-building.

"SO WHAT?": IMPLICATIONS OF FINDINGS

What are the implications of these changes over time for the developing peace and security landscape of post-Cold War Europe? At least, according to the views of the CSCE/OSCE negotiators recorded here, Europe in the post-Cold War period could be characterized as follows. First, they perceive a decline in violent ethnic conflict as a major threat to international peace and security. This is compatible with responses to question 7 for 1997, which are in the "mixed feelings" range (see Table B.4), on whether the withdrawal of SFOR would lead to a resumption of hostilities in Bosnia. Second, NATO is more likely to attempt to play an effective peacekeeping role in some of these conflicts. Third, whatever peacekeeping role it does play in these conflicts, NATO is less likely to liaise with its former WTO adversaries. Fourth, NATO's mechanisms for reaching out to its former adversaries (NACC/EAPC and PfP) are less likely to develop into a post-Cold War security system. Fifth, to the extent that these new mechanisms do develop into such a system, it is less likely that they would do so within the context of the CSCE/OSCE. Sixth, they anticipate more effort to address the factors underlying the use of force in conflicts that are threats to peace and security, but feel it is less likely that the failure to do so would cancel out the resolution value of forceful intervention. Seventh, it will be less likely that states and IGOs will work together in an integrated manner with humanitarian and conflict resolution NGOs, but more likely that there will be an increase in the number of (noncoercive) peacemaking and peacebuilding mechanisms. Eighth, they believe it is less likely that the Cold War is over. Hence, there is greater likelihood of an increase in East-West tensions. However, according to the responses to question 13 for 1997, which, with the exception of the OSCE Secretariat, are all in the "disagreement" range" (see Table B.8), NATO enlargement would not play a significant role in this regard.38 Finally, it is less likely that, with the ending of the Cold War, a perception exists in the developing world that East-West has been replaced by North-South as the dominant axis of international conflict. But to the extent that such a view has developed, it is less likely to be invalid.

CONCLUSION

According to the views of CSCE/OSCE negotiators reported here, therefore, the future of Europe could include the following trends: an increase in East-West tensions and a concomitant decrease in the threat of violent ethnic conflict to international peace and security, the current warfare in Chechnya notwithstanding; an expanding, assertive NATO attempting to deal more often, and sooner, with violent ethnic conflicts to the extent that they constitute such a threat, but consulting less often with former adversaries when dealing with these. Moreover, NATO and OSCE are likely to remain distinct structurally. Furthermore, NATO and the OSCE, on the one hand, and on the other, track-2 conflict resolution NGOs, will remain distinct operationally, with the "negative-peace" emphasis of NATO and "basket-1" aspects of the OSCE (hard security) having primacy over the "positive-peace" emphasis of "basket-2/3" parts of the OSCE and track-2 conflict resolution NGOs (soft security).

While all this does not necessarily mean a halt in the aforementioned "paradigm shifting," or a return to an East-West game governed primarily by track-1, negative-peace concerns, it does suggest that the euphoria initially associated with the ending of the Cold War may have come to an end. Whatever movement toward Idealpolitik has taken place, has occurred within a basically Realpolitik framework. This "complex" relationship between two otherwise competing paradigms could, however, over time, shift to Realpolitik processes being utilized within a basically Idealpolitik framework.39 The tilt toward overarching cooperative in lieu of competitive processes suggested by such a shift, would, in my view, be more compatible with the OSCE notion of a common and comprehensive security model for Europe for the twenty-first century.40

Endnotes

1. This project effectively began with my tenure as a William C. Foster Fellow

as a Visiting Scholar with the US Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA)

in 1989-90. During that time, I served on the US delegation to the negotiations

on Confidence- and Security-Building Measures (CSBMs) which occurred within

the context of the (then) CSCE. This initial experience revealed to me the CSCE's

potential for shaping the peace and security environment of post-Cold War Europe,

facilitating its transformation from a bipolar confrontational system into a

system of common security. Subsequently, I was awarded a NATO Research Fellowship,

which enabled me to return to Vienna in 1993 to conduct the first set of interviews

with heads of delegation to the CSCE. A Fulbright OSCE Regional Research Scholarship

allowed me to return to Vienna in 1997 to conduct followup interviews with heads

of delegation to the ("reframed") OSCE. The initial published report

on the project is "Changing Ideologies in the Conference on Security and

Cooperation in Europe," in Daniel Druckman and Christopher R. Mitchell,

eds., "Flexibility in the International Negotiation and Mediation,"

Special Issue of The Annals of the American Academy of Political and

Social Science 542 (November 1995), pp. 131-47.

Return to article

2. See Sandole, "Changing Ideologies."

Return to article

3. P. Terrence Hopmann, "Building Security in Post-Cold War Eurasia:

The OSCE and U.S. Foreign Policy," Peaceworks no. 31 (Washington,

DC: U.S. Institute of Peace, September 1999); and Hopmann, "The Organization

for Security and Cooperation in Europe: Its Contributions to Conflict Prevention

and Resolution," in Paul C. Stern and Daniel Druckman, eds., International

Conflict Resolution: After the Cold War (Washington, DC: National Academy

Press, 2000).

Return to article

4. See the Helsinki Final Act in Conference on Security and Cooperation

in Europe (Helsinki, 1 August 1975).

Return to article

5. Dennis J.D. Sandole, Capturing the Complexity of Conflict: Dealing with

the Violent Ethnic Conflicts of the Post-Cold War Era (London and New York:

Pinter/Continuum International, 1999), pp. 150-57.

Return to article

6. For an insider's account of the development of the CSCE during the Cold War, see John J. Maresca, To Helsinki: The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, 1973-1975 (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 1985). For an "extensive analysis of the origin, development and basic features of the Helsinki process," from 1972 until 1993, with accompanying official documents, see Arie Bloed, ed., The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe: Analysis and Basic Documents, 1972-1993 (Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Boston, MA and London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1993). And for an update, to 1995, with accompanying official documents, see Arie Bloed, ed., The Conference on Security and Co-Operation in Europe: Basic Documents, 1993-1995 (The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff, 1997).

For specific discussions of the role of the CSCE/OSCE in the post-Cold War world, see Michael R. Lucas, "The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe and the Post-Cold War Era," Hamburger Beiträge zur Friedensforschung und Sicherheitspolitik (Hamburg: Institut für Friedensforschung und Sicherheitspolitik an der Universität Hamburg, IFSH, 1990); Michael R. Lucas, ed., The CSCE in the 1990s: Constructing European Security and Cooperation (Baden-Baden, Germany: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 1993); Walter A. Kemp, "The OSCE in a New Context: European Security Towards the Twenty-first Century," Discussion Paper 64 (London: The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1996); and P. Terrence Hopmann, "Building Security," and "Organization."

For monthly, quarterly, annual and other periodic reports on the OSCE, see

the OSCE Review (published by the Finnish Committee for European Security [STETE];

e-mail: stete@kaapeli.fi); and the Helsinki

Monitor: Quarterly on Security and Cooperation in Europe (published by the

Netherlands Helsinki Committee [NHC]; fax: +31-30-30-25-24); and documentation

from the OSCE Secretariat, including the monthly OSCE Newsletter and Secretary

General's Annual Report (e-mail: info@osce.org;

and the OSCE Website at: http://www.osce.org).

Also see the OSCE Yearbook (published since 1995 by the Institute for

Peace Research and Security Policy [IFSH], and in future by the newly created

Centre for OSCE Research [CORE], at the University of Hamburg; e-mail: Schlichting@public.uni-hamburg.de).

Return to article

7. See CSCE Budapest Document 1994: Towards a Genuine Partnership in

a New Era (Budapest, 6 December 1994).

Return to article

8. For a discussion of some of the causes and conditions of such conflict,

see Dennis J.D. Sandole, "Paradigms, Theories, and Metaphors in Conflict

and Conflict Resolution: Coherence or Confusion?" in Dennis J.D. Sandole

and Hugo van der Merwe, eds., Conflict Resolution Theory and Practice: Integration

and Application (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press and New York:

St. Martin's Press, 1993); and Sandole, Capturing the Complexity, ch. 6, and

pp. 134-50.

Return to article

9. See Morton Deutsch, The Resolution of Conflict: Constructive and Destructive

Processes (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 1973).

Return to article

10. See Sandole, "Paradigms," and Capturing the Complexity,

pp. 110-12.

Return to article

11. See Johan Galtung, "Violence, Peace and Peace Research," Journal

of Peace Research 6, no. 3, (1969), pp. 167-91.

Return to article

12. Ibid.

Return to article

13. See Johan Galtung, Peace By Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development

and Civilization (London and Thousand Oaks, CA: International Peace Research

Institute, Oslo, Norway [PRIO], SAGE Publications, 1996).

Return to article

14. See William D. Davidson and Joseph V. Montville, "Foreign Policy According

to Freud," Foreign Policy no. 45 (Winter 1981-82), pp. 145-57; John W.

McDonald, Jr. and Diane B. Bendahmane, eds., Conflict Resolution: Track Two

Diplomacy (Washington, DC: US Department of State, Foreign Service Institute,

Center for the Study of Foreign Affairs, 1987); and Louise Diamond and John

W. McDonald, Jr., Multi-Track Diplomacy: A Systems Approach to Peace

3rd ed. (West Hartford, CT: Kumarian Press, 1996).

Return to article

15. See Sandole, Capturing the Complexity.

Return to article

16. For the most recent unpublished report of the CSCE/OSCE project, which,

in addition to the 1993 and 1997 surveys, deals with a third set of interviews

conducted in summer 1999 immediately following the termination of the NATO air

war against Serbia, see Dennis J.D. Sandole, "Peace and Security in Post-Cold

War Europe: A 'Community of Values' in the CSCE/OSCE?" Paper presented

at the 41st Annual Convention of the International Studies Association (ISA),

Los Angeles, California, 14-17 March 2000.

Return to article

17. See Abraham Kaplan, The Conduct of Inquiry: Methodology for Behavioral

Science (Scranton, PA: Chandler, 1964), pp. 164-65; and Daniel Katz, "Field

Studies," in Leon Festinger and Daniel Katz, eds., Research Methods

in the Behavioral Sciences (New York and London: Holt, Rinehart and Winston,

1953), pp. 78-79. I would also be doing a successive cross sectional study,

based on data collected from CSCE negotiators before and from OSCE negotiators

after Dayton brought negative peace to Bosnia in 1995. See A. Angus Campbell

and George Katona, "The Sample Survey: A Technique for Social Science Research,"

in Festinger and Katz, eds., Research Methods in the Behavioral Sciences,

pp. 24-25.

Return to article

18. Germany, Italy and the United States each made two representatives available

for interview. Among the remaining states in the sample, one representative

from each was interviewed. Hence, 29 CSCE states in the sample plus 3 additional

interviewees equalled a total of 32. Twenty-three of these (72 percent) were

heads of delegation. Sandole, "Changing Ideology," p. 136, fn. 12.

Return to article

19. Although a member of the CSCE, the "rump" Yugoslavia was banned

from attending all meetings of the CSCE at the end of the fourth CSCE review

conference in Helsinki, on 8 July 1992, because of its, particularly Serbia's,

responsibility for fomenting and sustaining the genocidal warfare in former

Yugoslavia.

Return to article

20. See Chava Frankfort-Nachmias and David Nachmias, Research Methods in

the Social Sciences, 5th ed. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996), pp. 183-84.

Return to article

21. The remaining successor republic of the former Yugoslavia, the Former

Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, although not yet a member of the CSCE, had "observer"

status by summer 1993.

Return to article

22. Many of the successor states of the former Soviet Union did not have CSCE

delegations in Vienna by summer 1993. If they did, they were usually "one-man

shows," representing their governments at various levels (e.g., to the

State of Austria and to the United Nations in Vienna, as well as to the CSCE).

Therefore, their representatives were generally unavailable for interview. This

was also the case with other CSCE participating states that were either not

represented in Vienna (e.g., Malta), or if they were, their busy representatives

were not available for interview (e.g., Albania). (Albania, incidentally, does

not belong to any of the five main groupings.)

Return to article

23. See Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, Research Methods, pp. 253-55.

Return to article

24. Ibid., pp. 465-67.

Return to article

25. Ibid., pp. 232-37.

Return to article

26. All interviews were conducted in English. With the exception of the American,

British and Canadian representatives, for whom English was their mother tongue,

the other representatives spoke English as one of their foreign languages. Some

of these individuals requested additional information "in English,"

in order to make a particular question clearer to them. On the assumption that

this provision of additional information on an ad hoc basis could have affected

the comparability of responses between individuals to the same item, as partial

checks interviewees were invited to explain their SA-SD answers in an open-ended

fashion . "in the margin," so to speak . as well as to respond to

the 12 open-ended questions, many of which overlapped with the closed-ended

ones.

Return to article

27. The number under each group's heading in each of the following tables represents

the mean (average) score for the group in terms of the 1-5 Likert scale. When

more than one question appears in a table, "grand means," computed

from the individual-question mean responses, were included to gain a sense of

where the groups stood on thematically similar questions. Again, the higher

the number, the more in agreement the group was with the item or cluster of

thematically similar items. The Roman numerals at the bottom of each table represent

rankings based on degree of agreement as indicated by the mean scores.

Return to article

28. See Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, Research Methods, pp. 113-15.

Return to article

29. See Richard Holbrooke, To End a War: From Sarajevo to Dayton . And

Beyond (New York: Random House, 1998).

Return to article

30. The FRY remained banned from attending all meetings of the OSCE because

of its, particularly Serbia's, role in fomenting and sustaining the genocidal

warfare in former Yugoslavia, a situation which continued with the brutal Serbian

repression of ethnic Albanians in Kosovo.

Return to article

31. I interviewed one person from each participating state in the overall sample,

with the exception of the US delegation which had two persons available for

interview; hence, 47 persons from 46 participating states. Thirty-seven (79

percent) of the interviewees were heads of delegation. (Two persons in the 1997

survey were also present in the 1993 survey.)

Return to article

32. As in 1993, I was unable to reach certain participating states, either

because they were not represented in Vienna (e.g., Andorra, the newest OSCE

member) or if they were, were represented by busy delegations (e.g., Kazakhstan).

I succeeded in contacting some delegations, even talking with their ambassadors,

but for a variety of reasons, was unable to conduct the standard interview (e.g.,

Albania, Tajikistan). (Andorra, like Albania, is not a member of any of the

five main groupings.)

Return to article

33. The number of closed-ended questions for the 1997 OSCE study was also the

same as that for the 1993 CSCE study (15). The number of open-ended questions

for 1997 (21), however, was nearly double that for 1993 (12). For both 1993

and 1997, the majority of the open-ended questions dealt with the wars in former

Yugoslavia. The initial report of analyses of responses to the open-ended questions

appears in Dennis J.D. Sandole, "Preventing Future Yugoslavias: The Views

of CSCE/OSCE Negotiators, 1993 and 1997," paper presented at the 40th Annual

Convention of the International Studies Association (ISA), Washington, DC, 16-20

February 1999.

Return to article

34. Since the CSCE Secretariat was not included in the 1993 study, the OSCE

Secretariat, which was included in the 1997 study, was omitted from the rankings

to facilitate comparisons between the 1993 and 1997 groupings of participating

states.

Return to article

35. Eliminating question 7 from Table A.3 for the 1993 study, to facilitate comparisons between 1993 and 1997 on NATO's post-Cold War role, we have the following:

36. See Sandole, "Peace and Security in Post-Cold War Europe: A 'Community of Values' in the CSCE/OSCE?" p. 42, which reads, "[According to the study reported in this paper] the least amount of consensus . . . was recorded for 1993, immediately following the end of the Cold War [while] the greatest amount of consensus occurred in 1997, two years after NATO brought 'negative peace' to Bosnia-Hercegovina" (emphasis added).

A note of methodological caution here. Focusing solely on the combined figures

for 1997 in Table B.11 as well as for 1993 in Table A.10, and making conclusions

about trends in responses across the 15 questions taken separately, could result

in the ecological fallacy . making inferences about the individual (disaggregated)

level of responses to questions directly from data on the group (combined) level.

In other words, evidence for the existence of three peace and security "metacultures"

exists more at the level of combined means . even for 1993, but especially for

1997 . than it does at the level of individual mean responses to the questions.

See Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, Research Methods, pp. 54-55.

Return to article

37. Among the exceptions to the various trends noted, the NNA deviated from

the general patterns on six occasions, NSWP on five occasions and the FSU on

five occasions. Interestingly enough, and as a reflection of the "metaculture"

finding generated by the 1993 CSCE study, the NNA and FSU deviated together

on three occasions (Questions 4, 10 and 14 [for 1993]/15 [for

1997]).

Return to article

38. Nevertheless, although in the "disagreement" range, the FSU is

closer to agreement than are the other regional groupings.

Return to article

39. See Sandole, Capturing the Complexity, chap. 8.

Return to article

40. Among the more recent manifestations of the OSCE deliberations concerning

the "common and comprehensive security model" is the Charter for

European Security and its Platform for Co-operative Security, resulting

from the Istanbul Summit of the OSCE in November 1999. See OSCE Istanbul Summit.

18-19 November'99: Charter for European Security (Istanbul: Organization

for Security and Cooperation in Europe, 19 November 1999).

Return to article