by Jonathan Fox

INTRODUCTION

For some time, the role of religion in conflict, including ethnic conflict, has been given considerable attention by the media, academics and policy makers.1 Ethno-religious conflicts, including the civil wars in Afghanistan, the former Yugoslavia and the Sudan as well as the peace processes in Israel and Northern Ireland, have often dominated the attention of these circles. Despite this there has been little large-number, cross-sectional research on religion and conflict in general, much less on the religious aspects of ethnic conflict, other than the larger study of which this work is part. For the purposes of this work ethno-religious conflict is distinguished from other types of ethnic conflict in that it involves ethnic groups which are of different religions.2

One explanation for this lack of empirical work on ethno-religious conflict is that there are two schools of thought which argue that the study of religion and conflict is "epiphenomenal," or irrelevant. The modernization/secularization school argues that the processes of economic and political modernization are causing the demise of primordial factors like ethnicity and religion.3 Those who argue against this body of theory argue that religion and ethnicity have never ceased to be important factors, citing numerous examples of current ethnic and religious conflicts as proof.4 They further argue that the process of modernization has actually increased the levels of ethnic and religious conflict5 and that the Cold War has removed systemic restraints on it.6 The functionalism school of thought posits that any perceived relationship between religion and conflict is illusory; religion itself is not a basic social force that affects society. Rather, religion acts as a front for other, more basic social forces.7 While those who argue against functionalism do not deny this, they argue that even after controlling for these other social forces, religion still has an independent influence.8

In one of the few examples of cross-sectional research on the subject, I established that while religious motivations do not play a major role in the majority of ethno-religious conflicts, they are important for a significant minority of such cases. However, my findings are limited to difference of means tests which establish that religious factors are salient in a large minority of ethno-religious conflicts and that such conflicts differ from other ethnic conflicts. These findings are significant but limited because any effect religion has on conflict is determined only by inference. No causality is established.9 Similarly, Rudolph Rummel links religious diversity in a state to ethnic conflict, but his religious diversity variable is too general to link, other than by inference, any religious motivations to this correlation.10

Accordingly, the purpose of this study is to assess empirically the causal effects of certain types of religious motivations for ethnic conflicts. The focus is on whether religious discrimination, and religious grievances based on such discrimination, affect the level of protest and/or rebellion in which ethno-religious minorities engage. Is religious discrimination one of the causes of ethno-religious protest and rebellion? This work shows that religious discrimination and grievances over that discrimination do contribute to rebellion and some types of protest but not in all cases and not always in the manner which one would intuitively expect.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The Model

The theoretical framework, as well as much of the data, is based in part on the literature on religion and conflict, and in part on the theoretical framework developed by Ted Robert Gurr to explain ethnic conflict.11 Gurr's approach combines the relative deprivation approach pioneered in his classic book Why Men Rebel12 with the group mobilization approach.13 While Gurr controls for many elements,14 his basic model is very simple and can be described in three steps. First, discrimination against an ethnic minority causes that minority to form grievances. Second, these grievances contribute to the mobilization of the minority for political action. Third, the more mobilized a minority the more likely it is to engage in political action including protest and rebellion. Gurr and Will H. Moore test variations of this model with regard to political, economic and cultural discrimination and grievances.15 However, they do not test his model using variables measuring religious discrimination and grievances. Gurr's culture variables are generally composite variables that do contain religion as one of many elements but he never tests for the affects of religion independently of other factors. Since it has been established that religious issues are salient in many ethnic conflicts, and considerable scholarly and anecdotal evidence demonstrates that religion can be a powerful motivating force,16 the absence of religion from this study is a shortcoming that warrants being addressed. Accordingly, an approach similar to Gurr's is used here, specifically testing the relationship between religious discrimination and grievances formed due to that discrimination as well as the relationship between those grievances and both protest and rebellion.

Two aspects of the literature on religion and conflict justify the extension of Gurr's theoretical framework to religion. The first is that religious frameworks or belief systems are an essential element in the psyche of their adherents. Such belief systems provide a religion's adherents with a framework with which to understand the world around them and allow them to function in it. Accordingly, if a religious framework is challenged in any way, for example by religious discrimination, this challenge constitutes a challenge to the inner souls of that religion's adherents. It is not hard to argue that such a challenge is very likely to cause grievance formation and provoke a defensive reaction among these adherents and that this defensive reaction is likely to be conflictive in nature.

Richard Wentz presents this argument eloquently. He argues that beliefs and values concerning the meaning of life and ultimate order are by definition political. Wentz describes such beliefs as the walls of religion which are psychological walls that people build around themselves and their religious communities in order to deal with reality.17 As feudal lords were prepared to defend the walls of their castles and fortresses, some people will do anything to defend the walls of their frameworks. For this reason, violence is frequently justified when religious frameworks are threatened.18 Anything is better than the loss of the identities and social solidarity that religious frameworks can provide. Clifford Geertz makes a similar argument in his description of "symbol systems,"19 which constitute a concept comparable to that of religious frameworks.

David Little describes three categories of challenges by other groups which constitute challenges to religious frameworks and can provoke a reaction: an "unorthodox" belief that is considered intolerable by an "orthodox" belief system; a religiously inspired political belief that recommends some sort of modification to the governmental structure and is, accordingly, considered a threat by that government; and a religiously inspired belief that is considered by the government to constitute an incitement against it.20 These three categories are useful in that they describe probable motivations for both religious discrimination by governments and religiously inspired challenges against governments.

Analogous arguments are also made with regard to religiously inspired terrorism by Mark Juergensmeyer,21 to millenarianism by David Rapoport,22 and to religious fundamentalism by R. Scott Appleby and Martin E. Marty,23 Rapoport, Ehud Sprinzak, and Timur Kuran.24 As a whole, these arguments are sufficient to make the point that challenges to religious frameworks are likely to provoke a conflictive response from the adherents of those frameworks. This is true regardless of the position of these adherents in the sociopolitical hierarchy. This argument can be summed up in the following proposition:

Proposition 1: Any challenge to a religious framework is likely to provoke a defensive and often conflictive response from the adherents of that religious framework. This is true irrespective of whether the group challenged occupies a dominant or subordinate role in society.

The second aspect of the literature on religion and conflict which justifies the extension of Gurr's theoretical framework to religion is that religious frameworks usually contain some sort of rules or standards of behavior describing how their adherents must behave. There are two ways in which these rules and standards of behavior are likely to provoke conflict. First, they require actions which are in and of themselves conflictive. A classic example of this is the concept of holy war, which can be found in all three of the Abrahamic religions. Second, they require actions which are likely to infringe upon another group's religious framework, forcing the second group to defend their beliefs.

Jeff Haynes' description of what he calls religio-political movements as those movements "whose leaders utilize religious ideologies . . . to attack the socio-political legitimacy and economic performance of incumbent governments"25 is consistent with this argument. Similarly, Little discusses what he calls a "warrant" which he defines as "a belief held by the dominant group that is taken to entitle that group to act intolerantly toward others."26 It is not hard to argue that the actualization of such a "warrant" can be in and of itself violent and, in any case, can provoke a violent response. Kent Greenawalt extends this argument to the individual level by arguing that "religious convictions . . . bear pervasively on people's ethical choices, including choices about laws and government policies."27 Thus, according to Greenawalt, even in the absence of any organized or unorganized group, religious frameworks can still inspire individuals to make political choices which are likely to provoke those who disagree with them.

Similar arguments are made with regard to religiously inspired terrorism by Bruce Hoffman28 and Rapoport29 and to religious fundamentalism by Appleby and Marty,30 Helen Hardacre,31 Faye Ginsburg,32 Sprinzak,33 and Kuran.34 As a whole, these arguments are sufficient to make the point that religious frameworks can inspire actions that are in and of themselves conflictive as well as actions that can cause a conflictive reaction from others. It should be noted that this argument is closely related to the argument regarding the first aspect of the literature on religion discussed above: the religiously inspired actions of one group can, often unintentionally, infringe upon the religious frameworks of other groups, thereby provoking conflict. Thus, while these two aspects of the literature on religion and conflict are theoretically distinct, in practice this distinction is often blurred. In any case, the argument made here can be summed up in the following propositions:

Proposition 2: Religious frameworks can cause a group to take actions which affect groups which do not subscribe to the same religious framework. Such actions are likely to infringe upon those other groups and provoke a conflictive response. This is true irrespective of whether the group that is infringed upon occupies a dominant or subordinate role in society.

Proposition 3: Religious frameworks often inspire actions, such as a holy war, which are in and of themselves conflictive in nature.

The three propositions discussed above can be reformulated into testable hypotheses that are consistent with Gurr's theoretical framework of discrimination and grievances leading to protest and rebellion as follows:

These hypotheses are consistent not only with Gurr's formula, but also with the argument that challenge to a religious framework can provoke a violent response. It is not hard to argue that religious discrimination could constitute such a challenge. Any group which is provoked by such a challenge should form grievances about it and then mobilize for political action including protest and rebellion. Thus, the model is the same as Gurr's. The additional factor added is religion. It should be noted that while the cause of the religious discrimination that begins this process is not directly addressed by these hypotheses, it can be explained as an action required by the religious beliefs of the dominant group which is the source of the discrimination.

While the above model describes the basic relationships which I am testing in this work, there is one other aspect of religious and ethnic conflict that is included in this study: religious legitimacy. For operational purposes, religious legitimacy is defined here as the legitimacy of the use of religion in political discourse. That religious organizations and individuals can use religion to justify conflict, opposition to a regime or oppression by a regime is an old argument made by many scholars including, for example, Juergensmeyer, David Kowalewski and Arthur Greil, Bruce Lincoln and W. Cole Durham.35 As a general note, it is clear that religious discrimination, grievances and legitimacy are not the only aspects of religion that affect conflict. For example, other aspects of the literature focus on religious institutions,36 specific types of religious movements,37 and that some religions are more violent than others.38 The discussion here has been mainly limited to those aspects of the literature that are relevant to the empirical testing presented in this work.

Research Design

The research design used here is modelled after Gurr's original analysis of the Minorities at Risk data. The dependent variables are protest and rebellion. (These and the other variables discussed in this section are described in detail below.) It is posited here, that as Gurr demonstrated for other types of discrimination and grievances,39 religious discrimination leads to religious grievances which, in turn, causes protest and rebellion, sometimes directly and sometimes through the mediating factor of mobilization. It is important to remember that any examination of the causes of rebellion and protest is also implicitly examining when and why they do not occur. Cases where there is no rebellion and or protest are as important to the analysis as the cases where these variables reach their highest levels.

We need to take two types of control variables into account. First, are ethnic and other factors which Gurr and Moore found to be relevant to the process of ethnic conflict. These include: nonreligious grievances which, as noted above, are an important cause of mobilization, protest and rebellion; political discrimination which is used to account for the extent of government repression; grievances over autonomy, which Gurr found to be the most significant cause of rebellion and mobilization for rebellion; and democracy which, as discussed below, has an important influence on whether groups will engage in protest or rebellion.40 The second type of control variable controls for religious factors. The only such variable used here is religious legitimacy. I have described the reasons for using this variable in the previous section.

Because this study is modelled after Gurr's work, as well as reasons of data availability,41 this study uses cross-sectional methodology. This methodology is also appropriate because the goal is to assess the influence of religious factors on ethnic protest and rebellion across a large number of cases. A cross-sectional analysis is well suited to make such an assessment.

The Data

The variables used here come from two sources. The ethnic conflict variables are taken from Gurr's Minorities at Risk Phase 3 dataset (MAR3). The unit of analysis is the ethnic minority. There are 268 minorities coded in the MAR3 dataset of which 105 are ethno-religious minorities.42 It is important to note that the 268 ethnic minorities contained in the MAR3 dataset constitute only a fraction of the number of ethnic minorities in the world. Gurr notes that there may be as many as 5,000 ethnic minorities worldwide but the dataset is intended to focus on how ethnicity influences the political process.43 Accordingly the dataset focuses on those ethnic minorities which are politically active based on two criteria, one of which is sufficient for the group to be included in the dataset. The first criteria is whether "the group collectively suffers, or benefits from, systematic discriminatory treatment vis-a-vis other groups in the state."44 The second criteria is whether "the group was the focus of political mobilization and action in defense or promotion of its self-defined interests."45

For operational purposes a minority is a ethno-religious minority when at least 80 percent of that group's members are of different religious denominations than that of the dominant ethnic group.46 Also, these groups are only included if there is a viable government that is in control of the state in question. This is because the data is designed to analyze the relationship between ethnic minorities and the state. For this reason, cases like the civil wars in Bosnia and Afghanistan are not included. Additional religion data on these 105 groups was coded for the larger study of which this work is part.

Most of the variables are judgmental ordinal variables or composite variables created from several judgmental ordinal variables. That is, the variables were assigned values by a coder using an ordinal scale based on specified criteria.

Religion Variables

All of the religion variables, unless otherwise noted, are coded separately for 1990-91, 1992-93 and 1994-95. Labels for variables coded for 1990-91 end in 91, those coded for 1992-93 end in 93, and those coded for 1994-95 end in 95. These variables are not part of the MAR3 dataset and were coded specifically for the larger study of which this work is part.

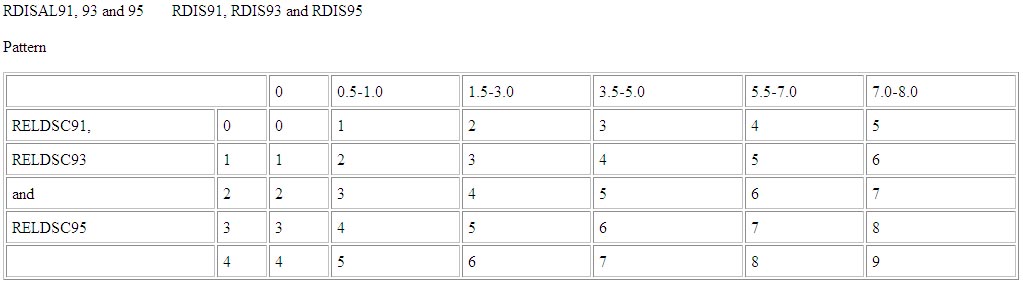

Religious Discrimination: Religious discrimination is defined as the extent to which religious practices are restricted either due to public policy or widespread social practice. I use three religious discrimination variables. The first (RELDSC91, 93 and 95) codes the level of official involvement in religious discrimination on a judgmental scale of 0 to 4.47 The second religious discrimination variable (RDIS91, 93 and 95) is a composite indicator, ranging from 0 to 8, of the scope of the discrimination which combines several coded variables.48 The third religious discrimination variable (RDISAL91, 93 and 95) is a composite of the previous two variables and coded on a scale of 0 to 9.49

Religious Grievances: Religious grievances are defined as grievances publicly expressed by group leaders over what they perceive as religious discrimination against them. This variable (RELGRVX91, 93 and 95), ranging from 0 to 24, is a composite variable measuring the grievances expressed by minority groups over religious issues.50

Religious Demands: Religious demands are defined as the demand for religious rights and/or privileges. This variable (RPROV91, 93 and 95), ranging from 0 to 5, differs from religious grievances, which are complaints against religious discrimination. Thus, religious grievances are reactive, whereas religious demands are active demands for more rights and privileges that have no direct connection to any form of discrimination.51

Religious Legitimacy: Religious legitimacy is defined as the extent to which it is legitimate to invoke religion in political discourse. The variable (RLEG91, 93 and 95), ranging from 0 to 4, is a composite indicator based upon codings for four factors. The presence of each of these factors is posited to indicate indirectly that it is legitimate to invoke religion in political discourse.52

Ethnic Conflict Variables

Unless otherwise noted, these variables are taken directly from the MAR3 dataset.

Political discrimination: This variable (ALLPD92), ranging from 0 to 9, is a composite variable measuring the level of political discrimination against a minority during 1992 and 1993. It is based on two factors: first, the presence and strength of political restrictions on freedom of expression, free movement, place of residence, rights in judicial proceedings, political organization, restrictions on voting, recruitment to the police and/or military, access to the civil service and attainment of high office; and second, whether the government's policies are intended to improve the minority's political status or are discriminatory.

Grievances over autonomy: This variable (AUTGR93), ranging from 0 to 12, is a composite variable measuring the grievances expressed by the minority group over autonomy and self-determination issues in 1992 and 1993. It is based on the strength of grievances expressed over the following issues: general autonomy grievances (coded only if other more specific categories could not be coded); union with kindred groups elsewhere; political independence; regional autonomy with widespread powers; and regional autonomy with limited powers.53

Nonreligious Grievances: This variable (ALLGR93a), ranging from 0 to 42, is a composite variable measuring the sum of political, economic and autonomy grievances expressed by the minority group in 1992-93. The factors included in the autonomy variable are listed above and the factors included in the political and economic variables are described in Gurr.

Protest and rebellion: Protest (PROT93, 94 and 95), is coded on a Guttman scale of 0 to 6 for each year from 1993 to 1995.54 Rebellion (REB93, 94 and 95), is coded on a Guttman scale of 0 to 7 for each year from 1993 to 1995.55

Number of Peaceful Political Organizations: This variable (OPORG9), measures the number of group-supported peaceful political organizations that are actively pursuing group interests during the 1990s (until 1996) on the following scale: 0 = none reported; 1 = one; 2 = two; 3 = three or more.

Number of Militant Political Organizations: This variable (MILORG9), measures the number of group supported militant political organizations that are actively pursuing group interests in the 1990s (until 1996) on the same scale as the above variable.

Scope of Peaceful Political Organizations: This variable (OPSCOP9), estimates the scope of support for the same organizations as the above variable organizations during the 1990s (until 1996) on the following scale: 0 = no political movements recorded; 1 = limited - no political movement is supported by more than a tenth of the minority (also if movements were identified by name but information is not sufficient to code scope of support for any of them); 2 = medium - the largest political movement is supported by a quarter to half of the minority; 3 = large - the largest political movement is supported by more than half of the minority.

Scope of Militant Political Organizations: This variable (MILSCOP9), estimates the scope of support for the same organizations as the above variable organizations during the 1990s (until 1996) on the same scale as the above variable.

Democracy: This variable is included in the MAR3 dataset and is taken from the 1994 version of the Polity III dataset. It measures the level of a state's institutional democracy in 1994 on a scale of 0 to 10 based on the following factors: competitiveness of political participation; competitiveness of executive recruitment; openness of executive recruitment; and constraints on the chief executive.56

Data Reliability

In order to verify the reliability of the religion data tested here, 21 out of the 105 cases were recoded by backup coders. The coders were all coders who collected and coded the data for the MAR3 dataset (as opposed to the religion variables which were coded separately). The cases to be coded were selected randomly from the cases that these specific coders coded for the MAR3 dataset. The results from these cases were then correlated with the original coding as presented in Table 1. All of the correlations have a significance of greater than .001 and all of the correlations, except for those for religious legitimacy, are above .75. Considering the judgmental nature of these variables, these results are sufficiently high to verify the reliability of these variables.

Data Analysis

Religious Discrimination and Religious Grievances

Hypothesis 1 states that religious discrimination, whatever its cause, is likely to result in the formation of religious grievances within the ethnic group suffering from this religious discrimination. That is, there should be a strong correlation between the religious discrimination variables and the religious grievances variables in this dataset. Table 2 provides considerable confirmation for this hypothesis. The correlations between the religious discrimination and religious grievances variables range from slightly less than .72 to nearly .78, with high levels of significance.

Some of the religious minorities in Azerbaijan provide more concrete examples of this relationship. The Russian minority suffers from no religious discrimination and expresses no religious grievances. The Armenian minority, however, suffers from religious discrimination and expresses religious grievances.57

Religious Grievances and Protest

Hypothesis 2 predicts that religious grievances are likely to cause protest among the ethnic group which has formed these grievances. In other words, the religious grievance variables should have a strong positive correlation with the protest variables. An examination of the data shows that the actual relationship is considerably more complicated than Hypothesis 2 suggests. The correlations between the religious grievances and protest variables, shown in Table 3, run counter to the relationship predicted in Hypothesis 2. Simple correlations between religious grievances in 1992-93 and both the protest and mobilization for protest variables are all negative. All of these correlations are weak and only the correlation between religious grievances and the variable for the number of peaceful organizations the group supports is significant. The fact that all of these correlations are weakly negative is a strong indication that at the very least the religious grievances variable does not have the expected positive effect on the protest variable and may, in fact, have a negative effect on protest. Consequently, as religious grievances increase, rather than increasing, the level of protest tends to decrease it.

There are several possible explanations for this counter-intuitive result. The first can be found in the analysis of Phase 1 of the Minorities at Risk dataset. This analysis showed that minorities in democratic societies are far more likely to engage in protest rather than rebellion. This is because democratic societies usually allow for protest as a legitimate means for a group to address its grievances. In less democratic societies, protest tends to be repressed, leaving rebellion as the only remaining option for addressing grievances.58 Thus, it is precisely in those countries in which peaceful protests are most likely to occur that religious discrimination, and thus, the formation of religious grievances, is least likely. This could account for the negative relationship between the protest and religious grievances variables.

Another way to approach this argument is to focus not on a government's level of democracy, but rather to focus on the level of repression in which a government engages. It is reasonable to argue that governments engaging in high levels of religious discrimination are precisely the governments that are most likely to engage in other forms of repression. The more repressive a government, the more difficult it is to engage in protest activities. Charles Tilly and Mark Lichbach both make this arguments.59 Thus, high levels of religious grievances, which are highly correlated with religious discrimination, should be correlated with lower levels of protest. The variable used here to measure repression is political discrimination in 1992-93 (ALLPD92). This variable is an appropriate measure of repression because it measures active political restrictions on the minority group. It should be noted that Gurr and Moore argue that using repression as a control is more appropriate than using democracy or autocracy. This is because it is repression that directly affects group behavior and measuring the level of democracy or autocracy is merely an indirect measure of that repression.60

A third possible explanation for the low levels of protest at high levels of religious grievances, is provided by the level of the legitimacy of religious involvement in politics. In some societies religion has a history of involvement in politics and conflict and in such societies a certain level of religious discrimination is considered a normal part of life. Accordingly, while there may be some grievances over religious discrimination in such societies, these grievances would be less likely to surface in the form of protest. Why protest against what is considered to be a normal part of one's daily existence? However, in societies where there is no such history of legitimacy of religious involvement in politics and conflict, religious grievances should contribute to protest activity.

For example, the Copts in Egypt suffer from a considerable amount of religious discrimination. In addition to considerable political and economic discrimination they are also subject to considerable religious discrimination, both official and unofficial. The government restricts Christian broadcasting, public speech, holiday celebrations and the number of Coptic institutions. In fact, many Coptic hospitals, schools and church lands have been confiscated. To make matters worse, the government strictly enforces an 1856 law making it illegal to build or repair a church without presidential approval, which is not given very often. All of this is in addition to harassment by Islamic militants, which includes the spreading of false rumors, extortion and violence up to and including murder. This violence often occurs with the tacit approval of local officials. The group Gama'a al-Islamiya is believed to be responsible for much of this violence, but it is only one of the numerous militant Islamic organizations. There is also the violence perpetrated by individuals.

Despite all of this, the Copts have engaged in relatively low levels of protest and no rebellion.61 One explanation for this is the historical legitimacy of religious discrimination against them. Historically, under Muslim rule the Christian Copts have been alternately treated with tolerance or repressed. As Dhimmi or "peoples of the Book," Copts are a tolerated religion under Islamic law. However, Islamic law can be interpreted in different ways to produce different levels of tolerance varying from considerable to none. In any case, Dhimmi, under Islamic law, are always second class citizens. Also, the involvement of religion in politics has a high level of legitimacy in Egypt.62

On the other hand, in France the involvement of religion in politics has a low level of legitimacy.63 Accordingly, it is not surprising that relatively minor levels of religious discrimination provoke more protest there than the considerable levels of religious discrimination endured by the Copts in Egypt. Muslim girls in France have been on several occasions denied the right to wear traditional Muslim head scarves while attending public schools. This has sparked a considerable amount of protest and the occasional public demonstration. However, it should be noted that the primary grievances of most North African Muslims in France are economic and political. In any case, these two examples provide support for the argument that where religious discrimination is historically a normal part of society, it is more likely to be tolerated by the victims of that discrimination.64

Accordingly, variables for these three factors, democracy, political discrimination and religious legitimacy, are included in multiple regressions, shown in Table 4, to control for their affects on protest and mobilization for protest. A non-religious grievances variable is included as a control factor because Gurr has demonstrated that they are significant causes of protest.65 Similarly, a mobilization for protest variable is included in the regression for protest because these studies have demonstrated it also is a significant antecedent to protest.

The adjusted R2 for these regressions ranges from .067 to .203 leaving room for substantial improvement with regard to explained variance. However, the primary goal here is not to maximize R 2, but to assess the effects of religious grievances on protest and mobilization for protest. That the religious grievances variable is consistently negative is sufficient to show that even when controlling for a variety of factors, religious grievances are clearly associated with lower levels of protest.

It is interesting to note that the only regression in which the religious grievances variable is a significant factor is the regression for protest. Religious grievances do not appear to have a significant influence on mobilization for protest. The implications of this result are discussed below.

Protest and Religious Demands

A fourth possible explanation is that the positive correlation between religious grievances and protest predicted in Hypothesis 2 exists only with respect to the more active grievances. The religious grievances variable used thus far (RGRV) measures passive grievances. That is, it measures complaints about religious discrimination. A variable that can be used to measure a more active form of religious grievance is one that measures religious demands (RPROV). This variable measures active demands for additional religious rights, as opposed to measuring the demand for an end to religious restrictions. Since RPROV measures a stronger and more active form of grievance it is more likely to be a cause of protest. Also, any group expressing demands for more religious rights is by definition willing to openly petition a government for more rights and is, accordingly, probably more disposed to protest than other groups. Such a group probably also lives in an environment where it is possible to express such complaints. All of this implies that if a group is able to express religious demands, it is very likely that they live in an environment where the levels of autocracy and repression are not sufficiently high to prevent them from engaging in protest and that they are willing to do so.

The data analysis provides some support for this explanation. The simple correlations between RPROV93 and the protest variables, shown in Table 5, are positive for all years tested and significant for 1993 and 1994 but not 1995. The simple correlations between RPROV93 and protest in 1995 as well as with the mobilization variables are positive but not significant.

Multiple regressions using the same control factors as used in the previous regressions concerning religious grievances, shown in Table 6, show that the religious demands variable is positively associated with the protest variable with a level of significance .055. As is the case with the religious grievances variable, the religious demands variable is not strongly associated with the mobilization for protest variable. While these results are not decisive, they do seem to indicate that the religious demands variable has a positive relationship with protest but not with mobilization for protest.

Rebellion and Religious Grievances

Hypothesis 3 states that religious grievances are likely to cause rebellion among the ethnic group which has formed these grievances. In other words, there should be a positive correlation between the religious grievances and rebellion variables. However, simple correlations between these two variables, as shown in Table 7, show that there is little relationship between them.

A possible explanation for this can be found in the analysis of Phase 1 of the Minorities at Risk data. This analysis found that grievances over autonomy were the single most important predictor of rebellion during the 1980s.66 The results in Table 7 confirm this. The grievances over autonomy variable is significantly correlated with the rebellion variable but not the mobilization for rebellion variable. Interestingly, an interaction variable created by multiplying the variables for grievances over autonomy and religious grievances is more strongly correlated with the rebellion variable and is significantly correlated with the mobilization for rebellion variable.

There are several possible factors that must be taken into account when examining the relationship between religious grievances and rebellion in more detail in light of the above discussion on protest. First, religious discrimination and grievances are likely to be greater under more repressive regimes. While rebellion would be more likely than protest in such regimes, because rebellion is more difficult to repress than is protest, a sufficiently high degree of repression would make rebellion more difficult. Thus, it is precisely those states in which religious discrimination is most likely that rebellion is less likely. Second, rebellion is more likely to occur under autocratic regimes which are less democratic. Third, religious grievances are more likely to lead to rebellion in states where religion has political legitimacy. Finally, when predicting rebellion, mobilization for rebellion must be taken into account.

Multiple regressions, including the religious and autonomy grievances interaction variable and the above control variables, shown in Table 8, provides further evidence for the positive relationship between the interaction variable and the rebellion variable. The interaction variable and one of the mobilization variables, the scope of militant organizations, are the only significant variables in predicting rebellion. This regression has a respectable adjusted R 2 of .474. The other control variables prove to be not significant. The interaction variable is not a significant factor in predicting the first mobilization variable (the number of group-supported militant organizations), but is the only significant factor in the regression for the other mobilization variable: the scope of militant organizations. However, the adjusted R 2 for this regression is low at .123.

Discussion

It is clear that, as predicted in Hypothesis 1, there is a strong relationship between religious discrimination and grievances formed over that discrimination. However, the relationship between religious grievances and protest predicted in Hypothesis 2, as well as the relationship between religious grievances and rebellion predicted in Hypothesis 3, are considerably more complicated.

The evidence for Hypothesis 2 uncovers some interesting, unexpected and counter-intuitive results, specifically religious grievances appear to contribute to lower levels of protest. This is the opposite of the predicted relationship in Hypothesis 2. This relationship remains negative even when controlling for other factors, including democracy, the level of repression and religious legitimacy. However, the religious demands variable (RPROV93), which measures active demands for more religious rights (as opposed to the religious grievances variable RGRV93 which measures complaints about religious discrimination), does have the predicted relationship with protest. It should be noted that most of these correlations are weak and therefore cannot be considered conclusive.

This leaves open the question of why two variables which measure religious grievances can produce such drastically different results. Religious demands (RPROV93), unlike religious grievances (RGRV93), is probably positively correlated with protest because when a group feels comfortable enough to express active demands for more religious rights, it is likely that they live in a society in which they feel safe enough to engage in protest. Thus, it is probable that in such societies the levels of autocracy and repression are not high enough to prevent protest. Some of the negative correlations between RGRV93 and protest can be explained by arguing that the control variables used to account for autocracy and repression are imperfect measures of those phenomena. The autocracy and repression variables used here probably do not measure many of the more subtle forms of repression that prevent protest. In fact, the autocracy and democracy measures focus on institutional democracy and do not take into account factors such as a government's human rights record.67 This is less of a problem in the correlations between RPROV93 and protest because the occurrence of the demands which RPROV93 measures are most likely to occur in societies where those non-measured forms of repression and autocracy are at low levels. However, this explanation is problematic because, by definition, the data cannot deny or confirm such an argument.

In any case, the positive relationship between RPROV93 and protest provides an illustration of the second part of the literature on religion and conflict discussed above that religious groups are often inspired by their religious frameworks to engage in activities that are in and of themselves conflictive or are likely to provoke others. Active demands by an ethnic minority for more religious rights are very likely inspired by that minority's religious framework. The protest caused by these demands can be described as conflictive. Furthermore, it is even possible that the demands themselves could be enough to challenge the framework of the dominant group of that society provoking a reaction.

A second possible explanation is that the measures for democracy and autocracy are accurate, but they miss an important factor: that democracies do not always accommodate legal opposition. Other than perhaps demands for autonomy, religious demands are probably among the most threatening to a state in that they can be perceived as a challenge to basic issues of identity.68 For this reason, even in democracies, peaceful avenues toward change, such as protest, may prove ineffective and autocracies would be even less likely to allow for peaceful opposition under such circumstances. In fact, the level of religious discrimination, which is strongly correlated with religious grievances, may be an indirect measure of the unwillingness of a state to address religious grievances. This could explain the lower levels of protest as religious discrimination increases because many, like Gurr, Harff and Fox argue that when peaceful avenues to address grievances are shut off by democratic governments, minorities often abandon them and resort to more violent tactics.69 It is important to remember that while this explanation may be consistent with the data, is difficult to test directly using the data.

A third possible explanation for the counterintuitive relationship between religious grievances and protest is that religion is so fundamental an issue that when grievances reach a sufficient level, protest is simply disregarded in favor of more drastic measures including rebellion. There is some support for this in the data, including the positive correlation between religious grievances and rebellion. Again, this is a proposition that is difficult, if possible at all, to test directly using empirical data.

Hypothesis 3 predicts that religious grievances can contribute to the level of ethnic rebellion. The data analysis shows that this is the case but only when controlling for other factors, especially grievances over autonomy. In other words, the key to understanding the relationship between religious grievances and rebellion is that religious grievances are usually not in and of themselves enough to provoke rebellion. The predisposition toward rebellion must already be in place. In fact, in 1993 only two out of 38 ethno-religious minorities that express no grievances over autonomy engage in any rebellion. The first of these groups is the Shi'i in Iraq where it is fair to say that they desire autonomy but have been unable to express these grievances due to the high level of repression in Iraq. They do begin expressing grievances over autonomy in the 1994 to 1995 period. The second of these groups is the Maronites in Lebanon. In 1993, they engaged in the lowest level of rebellion measurable by the MAR3 dataset. Thus, unless a group is predisposed toward rebellion, as measured by the grievances over autonomy variable (AUTGR), they will rarely engage in rebellion and, accordingly, no factor including religious grievances is likely to cause them to do so.

Once this predisposition exists, however, the religious grievances variable (RGRV93) is strongly correlated with rebellion. Thus, when a group expresses grievances over both religious discrimination and autonomy, rebellion becomes likely. In fact, all seven ethno-religious minorities which in 1993 engaged in the highest levels of rebellion expressed grievances over both religious discrimination and autonomy in the 1992-93 period. All seven groups in this study, which in 1993 engaged in protracted civil wars as well as in intermediate or large-scale guerilla activity (a level of rebellion in 1993 coded as 5 or higher), expressed both grievances over autonomy (AUTGR93) and religious grievances (RGRV93) in the 1992-93 period. These groups are: the Armenians in Azerbaijan, the Abkhazians in Georgia, the Kashmiris in India, the Zomi/Chin in Myanmar, the Moros in the Phillippines, the Tamils in Sri Lanka and the Southerners in Sudan. As is the case with the relationship between religious grievances and protest, at high levels of repression, rebellion becomes less likely.

Another result that requires discussion is that religious grievances are consistently more strongly correlated with protest and rebellion than with mobilization for protest and rebellion. This has two possible implications. First, unlike other types of grievances, religious grievances affect protest and rebellion directly and not through a process of mobilization. This contradicts the predictions of the Minorities at Risk model which posits that grievances cause mobilization, which in turn causes protest and rebellion. However, these results do not eliminate mobilization as a factor in ethno-religious conflict. One of the mobilization variables, the scope of militant organizations, is strongly significant in the regression for rebellion. However, mobilization does not seem to be an important factor in the regression for protest.

Second, it is possible that the mobilization variables used here are inadequate to the task of measuring the process of mobilization. These variables are based on the number of organizations supported by the group and the scope of support for that group. While, on the surface, these would seem to be adequate measures, the variable measuring the scope of support measures only what percentage of group members nominally support the group. That is, this measure does not include factors like intensity of support or the actual financial and human resources available to it. Perhaps a measure that also included these factors would be more strongly associated with religious grievances.

CONCLUSIONS

As will be recalled, the framework for the research presented here is derived from three general propositions regarding the impact of religion on conflict. As discussed earlier, all three of these propositions are related. The above analysis sheds some light on these propositions with regard to ethno-religious conflict. Proposition 1 states that any challenge to a religious framework is likely to provoke a defensive and often conflictive response from the adherents of that religious framework. This is true irrespective of whether the group challenged occupies a dominant or subordinate role in society. In the case of ethnic conflict this appears to be true but the way in which this manifests itself is complicated. Religious discrimination, which is one form of a challenge to a religious framework, is strongly associated with grievances, which is a form of collective response. However, the actions taken based on those grievances are influenced by other factors. For instance, rebellion is rarely considered unless nationalist issues are also elements of the conflict. Also, the relationship between religious grievances and protest is most probably influenced by other factors, even if the nature of those factors is unclear.

Proposition 2 states that religious frameworks can cause a group to take actions which affect groups which do not subscribe to the same religious framework. Such actions are likely to infringe upon those other groups and provoke a conflictive response. This is true irrespective of whether the group that is infringed upon occupies a dominant or subordinate role in society. Also, the related Proposition 3 states that religious frameworks often inspire actions, such as a holy war, which are in and of themselves conflictive in nature. There is considerable evidence that minority groups behave as predicted by these propositions because demands for more religious rights, which are arguably inspired by their religious frameworks, are positively associated with the protest variable.

That majority groups engage in religious discrimination against ethno-religious minorities is most probably due, at least in part, to the influence of religious frameworks. It is also likely that religious motivations influence the extent of other types of discrimination. This discrimination, in turn and as noted above, interacts with the religious framework of the minority group causing a reaction, as predicted by Proposition 1. However, while these conclusions regarding the majority group are logical, they are neither supported or contradicted by the data.

Given all of this, even though this study focuses only on some aspects of the connection between religion and conflict in that the findings are limited to ethno-religious conflict, it is fair to say that it provides considerable empirical support for the argument that religion can play a significant role in conflict. This is important because it contradicts the predictions of religion's demise in modern times that still cause considerable debate in some academic circles.70

The findings of this analysis are significant for several additional reasons. First, they provide further evidence that religion can be and often is an important factor in ethnic conflict. Second, these findings go beyond earlier findings by Fox71 and Rummel72 by providing some insight into the relationship between religion and conflict rather than just demonstrating that such a relationship exists. They show that religious factors influence the dynamics of ethnic conflicts in a manner similar to but distinct from other types of grievances and discrimination. Religious discrimination is strongly linked to the formation of grievances over that discrimination. Religious grievances are shown to be a catalyst for rebellion when the prevailing conditions make rebellion likely. Unlike earlier studies however, which show a strong positive link between political, economic and cultural grievances and protest,73 religious grievances are negatively correlated with protest. Yet another type of grievance, active religious demands for more religious rights, is positively correlated with protest.

Finally, these findings show that not only can large-number, cross-sectional methodology provide insight into the relationship between religion and conflict, it can provide insights that are unlikely to have been uncovered by a comparative, case study approach. The striking example of this is that, even when controlling for other factors, the presence of some forms of religious grievances seems to decrease the likelihood of protest. However, this example also illustrates the limits of the large-number, cross-sectional approach in that the most likely explanations for this phenomenon are difficult, if at all possible, to test using this methodology. Thus, while the large-number approach can be useful in discovering unexpected relationships, the case study approach is still necessary both to build on the findings of the large-number approach, and to explain what the large-number approach cannot. I argue that the accumulation of knowledge of the influence of religion on ethno-religious conflict, as well as our knowledge of most topics of research in the social sciences, would be best served by combining the large-number and case study approaches because the strengths of each compensate for the weaknesses of the other.

In all, these findings provide the beginnings of empirical insight into the relationship between religion and conflict, but there is much that is still unclear. For instance, while religious discrimination and grievances are linked to protest and rebellion, these results do not prove or disprove whether religious frameworks, as posited here, are in fact the cause of this discrimination. However, these findings do show that the large-number, cross-sectional method of analysis, despite its shortcomings, can and does add to our knowledge of the relationship between religion and ethnic conflict. The results presented here barely begin to fill the hole in our knowledge of the subject created by the scarcity of similar studies.

Jonathon Fox is an Instructor in the Department of Political Studies at Bar Ilan University in Ramat Gan, Isreal.

Endnotes

The author would especially like to thank Ted R. Gurr for his insights, advice and criticism, without which this work would not have been possible. I would also like to thank Jonathan Wilkenfeld, Charles Butterworth, Ollie Johsnon, William Stuart and The Journal of Conflict Studies' anonymous referees for their helpful insights as well as the staff of the Minorities at Risk project, especially Pamela Burke, Mike Dravis, Mike Haxton, Mizan, Khan, Steve Kurth, Deepa Khosla, Shinwa Lee and Anne Pitsch, all of whom helped out when I was collecting the religion data, and most of whom helped with the backup codings. I alone am responsible for any errors of fact or interpretation that remain.

1. For a discussion of the increasing importance of ethnic conflict, see David

Carment and Patrick James, "The International Politics of Ethnic Conflict:

New Perspectives on Theory and Policy," Global Society 11, no. 2

(1997); Wars in the Midst of Peace (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh

Press, 1997); "Escalation of Ethnic Conflict," International Politics

35 (1998). For a discussion of the increasing importance of religion on ethnic

conflict, see Jonathan Fox, "The Effects of Religion on Domestic Conflict,"

Terrorism and Political Violence 10, no. 4 (Winter 1998); and Jeff Haynes,

Religion in Third World Politics (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1994).

Return to article

2. This operational definition is described in more detail in the data section

of this work.

Return to article

3. See, among others, Gabriel Almond, "Introduction: A Functional Approach

to Comparative Politics," in Gabriel Almond and James C. Coleman, eds.,

The Politics of the Developing Areas (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press, 1960); David, Apter, The Politics of Modernization (Chicago, IL:

University of Chicago Press, 1965); Karl Deutsch, Nationalism and Social Communication

(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1953); Donald E. Smith, ed., Religion and Political

Modernization (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press 1974); James A. Beckford,

"The Insulation and Isolation of the Sociology of Religion," Sociological

Analysis 46, no. 4 (1985); and Bryan R. Wilson, Religion in Secular Society

(Baltimore, MD: Penguin, 1966).

Return to article

4. See, for example, Kent Greenawalt, Religious Convictions and Political

Choice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988); and William H. McNeil, "Epilogue:

Fundamentalism and the World of the 1990s," in Martin E. Marty and R. Scott

Appleby, eds., Fundamentalisms and Society: Reclaiming the Sciences, the

Family, and Education (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1993).

Return to article

5. See, among others, Haynes, Religion in Third World Politics; Mark

Juergensmeyer, The New Cold War? (Berkeley, CA: University of California,

1993); and Emile Sahliyeh, ed., Religious Resurgence and Politics in the

Contemporary World (New York: State University of New York Press, 1990).

Return to article

6. See, for example, Samuel P. Huntington, "The Clash of Civilizations?"

Foreign Affairs 72, no. 3 (1993); "The West: Unique, Not Universal,"

Foreign Affairs 75, no. 6 (1996); and Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations

and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996).

Return to article

7. For more detailed arguments, see Wilson, Religion in Secular Society;

and Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Culture (New York: Basic Books,

1973).

Return to article

8. See, for example, Roland Robertson, "Beyond the Sociology of Religion?"

Sociological Analysis 46, no. 4 (1985). For a more detailed review of both the

modernization/secularization and the functionalist arguments, as well as the

counter-arguments to them, see Jonathan Fox, "The Salience of Religious

Issues in Ethnic Conflicts: A Large-N Study," Nationalism and Ethnic Politics

3, no. 3 (Autumn, 1997).

Return to article

9. In Fox, "The Salience," it is documented that out of 268 ethnic

minorities in the Minorities at Risk Phase 3 dataset, only 105 are religiously

distinct from the dominant group in that state. Of these 105 cases religion

is not salient in 28 cases, marginally salient in 38 cases, salient but less

important than other issues in 27 cases and as or more salient than other issues

in only 12 cases. However, those cases where religion is salient show marked

differences from other ethnic conflicts. Jonathan Fox, "Do Religious Institutions

Support Violence or the Status Quo?" Studies in Conflict and Terrorism

22, no. 2 (1999) and "The Influence of Religious Legitimacy on Grievance

Formation by Ethnoreligious Minorities," Journal of Peace Research 36 no.

3 (1999) add to this research exploring the influence of religious legitimacy

and institutions on ethno-religious conflict. However, these studies focus on

how some aspects of religion can influence a conflict already in progress, not

how religion can be the cause of a conflict. For a discussion of the difference

between religious causes of conflict and religious factors that can contribute

to a conflict already in progress, see Jonathan Fox, "Towards a Dynamic

Theory of Ethno-religious Conflict," Nations and Nationalism 5 no. 4 (October

1999).

Return to article

10. Rudolph J. Rummel, "Is Collective Violence Correlated with Social

Pluralism?" Journal of Peace Research 34, no. 2 (1997).

Return to article

11. Ted R. Gurr, Minorities At Risk (Washington, DC: United States Institute

of Peace, 1993); Ted R. Gurr, "Why Minorities Rebel," International

Political Science Review 14, no. 2 (1993); and Ted R. Gurr, and Barbara Harff,

Ethnic Conflict in World Politics (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1994).

Return to article

12. Ted R. Gurr, Why Men Rebel (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 1970).

Return to article

13. For a more comprehensive examination of the mobilization approach, see

Dennis Chong, Collective Action and Civil Rights (Chicago, IL: University of

Chicago Press, 1991); John A. Hannigan, "Social Movement Theory and the

Sociology of Religion: Toward a New Synthesis" Sociological Analysis 52,

no. 4 (1991); Doug McAdam, Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency

1930-1970 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1982); Doug McAdam, John

D. McCarthy and Mayer N. Zald, Comparative Perspectives in Social Movements

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996); Anthony Oberschall, Social Movements:

Ideologies, Interests and Identities (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 1993);

David A. Snow, E. Burke Rochford Jr., Steven K. Worden and Robert D. Benford,

"Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization and Movement Participation,"

American Sociological Review 51, no. 4 (1986); Sidney Tarrow, "Social Movements

in Contentious Politics: A Review Article," American Political Science

Review 90 (1996); Charles Tilly, From Mobilization to Revolution (Reading, MA:

Addison-Wesley, 1978); Charles Tilly, "Contentious Politics and Social

Change," African Studies 56, no. 1 (1997); and Keith Webb, et al. "Etiology

and Outcomes of Protests," American Behavioral Scientist 26, no. 3 (January/February

1983). For a critique of both the mobilization and the relative deprivation

approaches, see James B. Rule, Theories of Civil Violence (Berkeley, CA: University

of California Press, 1988).

Return to article

14. Including but not limited to group identity, repression, group cohesion,

international support for both the state and the ethnic group, state expansion,

economic development, state power, democratic institutions, the process of democratization

and the effect of one ethnic conflict on another.

Return to article

15. Gurr, "Why Minorities,"; Ted R. Gurr and Will H. Moore, "Ethnopolitical

Rebellion: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the 1980s with Risk Assessments for

the 1990s," American Journal of Political Science 41, no. 4 (1997).

Return to article

16. See, for example, Juergensmeyer, New Cold War; Mark Juergensmeyer, "Terror

Mandated by God," Terrorism and Political Violence 9, no. 2, (Summer 1997);

David Little, "Religious Militancy," in Chester A. Crocker and Fen

O. Hampson, eds., Managing Global Chaos: Sources of and Responses to International

Conflict (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1996); David

Little, Sri Lanka: The Inversion of Enmity (Washington, DC: United States Institute

of Peace Press, 1994); and David Little, Ukraine: The Legacy of Intolerance

(Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1991).

Return to article

17. Richard Wentz, Why People Do Bad Things in the Name of Religion (Macon,

GA: Mercer, 1987), pp. 13-21, 25-36, 53-70.

Return to article

18. See Jonathan Fox, "Is Islam More Conflict Prone than Other Religions?

A Cross-Sectional Study of Ethnoreligious Conflict," Nationalism and Ethnic

Politics 6, no. 1 (Spring 2000) for a discussion of arguments concerning the

relationship between specific religions and violence.

Return to article

19. Clifford Geertz, "Religion as a Cultural System," in Michael

Banton, ed., Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Religion (London: Tavistock

Publications, 1966).

Return to article

20. Little, Ukraine, p. xxi.

Return to article

21. Juergensmeyer, "Terror," p. 17.

Return to article

22. David Rapoport, "Some General Observations on Religion and Violence,"

Journal of Terrorism and Political Violence 3, no. 3 (1991), pp. 127-34.

Return to article

23. R. Scott Appleby, Religious Fundamentalisms and Global Conflict, Headline

Series #301 (New York: Foreign Policy Association, 1994), p. 15; Martin E. Marty

and R. Scott Appleby, eds., Fundamentalisms and the State: Remaking Politics,

Economies and Militance (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991), p.

3.

Return to article

24. David C. Rapoport, "Comparing Fundamentalist Movements and Groups,"

in Marty and Appleby, eds., Fundamentalisms and the State, pp. 429-30; Ehud

Sprinzak, "Models of Religious Violence: The Case of Jewish Fundamentalism

in Israel," in Marty and Appleby, eds., Fundamentalisms and the State,

pp. 463-68; Timur Kuran, "Fundamentalism and the Economy," in Marty

and Appleby, eds., Fundamentalisms and the State, pp. 290-91.

Return to article

25. Haynes, Religion in Third World Politics, p. 14.

Return to article

26. Little, Ukraine, p. xxi.

Return to article

27. Greenawalt, Religious Convictions, p. 30.

Return to article

28. Bruce Hoffman, "'Holy Terror': The Implications of Terrorism Motivated

by a Religious Imperative," Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 18, no. 4

(1995), p. 272.

Return to article

29. David C. Rapoport, "Fear and Trembling: Terrorism in Three Religious

Traditions," American Political Science Review 78 (1984), p. 654; and David

C. Rapoport, "Sacred Terror: A Contemporary Example from Islam," in

Walter Reich, ed., Origins of Terrorism: Psychologies, Ideologies, Theologies,

States of Mind (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 118.

Return to article

30. Appleby, Religious Fundamentalisms, p. 15; Marty and Appleby, Fundamentalisms

and the State, pp. 3-4.

Return to article

31. Helen Hardacre,"The Impact of Fundamentalisms on Women, the Family,

and Interpersonal Relations" in Marty and Appleby, eds., Fundamentalisms

and Society, p. 129.

Return to article

32. Faye Ginsburg, "Saving America's Souls: Operation Rescue's Crusade

against Abortion," in Marty and Appleby, eds., Fundamentalisms and the

State, p. 579.

Return to article

33. Sprinzak, "Models," p. 472.

Return to article

34. Kuran, "Fundamentalism," pp. 295-97.

Return to article

35. Juergensmeyer, New Cold War; David Kowalewski and Arthur L. Greil, "Religion

as Opiate: Religion as Opiate in Comparative Perspective," Journal of Church

and State 31, no. 1 (1990); Bruce Lincoln, ed., Religion, Rebellion and Revolution

(London: Macmillan, 1985), pp. 268-81; W. Cole Durham Jr., "Perspectives

on Religious Liberty: A Comparative Framework," in John D. van der Vyver

and John Witte Jr., eds., Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal

Perspectives (Boston, MA: Martinus Nijhoff, 1996). While religious legitimacy

can have a significant influence on ethnic conflict, as well as other forms

of conflict, it is not the focus of this study. It is rather a control variable.

For this reason the discussion on the topic here is limited. For a full theoretical

discussion as well as quantitative analysis of the influence of religious legitimacy

on ethno-religious conflict, see Fox, "The Influence."

Return to article

36. See, for example, Fox, "The Effects,"; Kowalewski and Greil,

"Religion as Opiate,"; Lincoln, Religion, pp. 268-81; and Durham,

"Perspectives."

Return to article

37. For example, Marty and Appleby, eds., Fundamentalism and the State; and

Marty and Appleby, eds., Fundamentalism and Society on fundamentalism; and Rapaport,

"Fear and Trembling,"; Rapoport, "Sacred Terror,"; and David

C. Rapoport, "Messianic Sanctions for Terror," Comparative Politics

20, no. 2 (January 1988) on messianic and terrorist movements.

Return to article

38. See, for example, Fox "Is Islam,"; Andrew M. Greely, Religion:

A Secular Theory (New York: Free Press, 1982); Manus I. Midlarsky, "Democracy

and Islam: Implications for Civilizational Conflict and the Democratic Peace,"

International Studies Quarterly 42, no. 3 (1998); and Rapoport, "Comparing

Fundamentalist," p. 446.

Return to article

39. Gurr, Minorities at Risk; Gurr, "When Minorities Rebel."

Return to article

40. Gurr, Minorities at Risk; Gurr, "When Minorities Rebel"; Gurr

and Moore, "Ethnopolitical Rebellion."

Return to article

41. For example, the religion data is only available for the 1990-95 period,

most of it collected for three time periods: 1990-91, 1992-93 and 1994-95. A

time series analysis would require data over a greater period of time.

Return to article

42. A recent update of the MAR dataset has added seven cases to the dataset

bringing the number of cases to 275. This study excludes these seven cases because

they were added after the data on religion was collected.

Return to article

43. Gurr, Minorities at Risk, pp. 5-7.

Return to article

44. Ibid., p. 6.

Return to article

45. Ibid., p. 7.

Return to article

46. Protestant and Catholic Christianity are considered separate religions

for the purposes of this study. However, Orthodox Christianity is not considered

sufficiently different from either Protestantism or Catholicism for such conflicts

to be included. The Sunni and Shi'i branches of Islam are considered separate

religions for the purpose of this study.

Return to article

47. The scale is constructed as follows: 0. None. 1. Substantial religious

discrimination in society due to general prejudice in society. Explicit public

policies protect and/or improve the position of the group's ability to practice

its religion. 2. Substantial religious discrimination in society due to general

prejudice in society. Public policies are neutral, or if positive, inadequate

to offset discriminatory practices. 3. Public policies of formal restrictions

on religious observance. Religious activities are somewhat restricted by public

policy. This includes religions that are tolerated but given a formal second

class status, (for example, Christian sects in many Muslim states). 4. Public

policies of formal restrictions on religious observance. Religious activity

is sharply restricted or banned.

Return to article

48. Each of the following specific types of religious discrimination were coded on a scale of 0 to 2 (2 = the activity is prohibited or sharply restricted for most or all group members; 1 = the activity is slightly restricted for most or all group members or sharply restricted for some of them; 0 = not significantly restricted for any). The coded values for the eight variables were added and the sum was divided by two to create a set of indicators (one for each biennium) with values that range from 0 to 8. The activities so coded are:

49. The two variables were combined based on the following table:

Table 1

50. This variable measures grievances publicly expressed by group leaders over discrimination in the same categories as those from which RDIS is constructed, in addition to a category for diffuse grievances that is only coded when no other specific category is coded. The level each type of grievance is coded on the following scale, the totals of which are added to form a scale of 0 to 24:

3 = issue important for most of the group.

2 = issue is significant but its relative importance cannot be judged.

1 = issue is of lesser importance, or of major concern to only one faction of the group.

0 = issue is not judged to be of any significant importance.

51. This variable is coded on the following scale:

0. None.

1. The group is demanding more religious rights.

2. The group is seeking a privileged status for their religion which offends the religious convictions of the dominant group.

3. The group is seeking to impose some aspects of its religious ideology on the dominant group.

4. The group is seeking a form of ideological hegemony for its framework which will affect some of the dominant group.

5. The group is seeking a form of ideological hegemony for its framework which will affect most or all of the dominant group.

52. Each of the following factors are coded as 1 if found to be present and RLEG is the total of these four factors:

53. Each of these categories was scored on the same scale as political grievances

and summed. (See previous endnote.)

Return to article

54. Protest is coded on the following scale:

0. None reported

1. Verbal opposition (public letters, petitions, posters, publications, agitation, etc.). Code requests by a minority-controlled regional group for independence here.

2. Scattered acts of symbolic resistance (eg. sit-ins, blockage of traffic), sabotage, symbolic destruction of property.

3. Political organizing activity on a substantial scale. (Code mobilization for autonomy and/or secession by minority-controlled regional government here.)

4. A few demonstrations, rallies, strikes and/or riots, total participation less than 10,000.

5. Demonstrations, rallies, strikes and/or riots, total participation estimated between 10,000 and 100,000.

6. Demonstrations, rallies, strikes and/or riots, total participation over 100,000. One drawback of this variable is that it uses absolute numbers to measure the highest levels of protest. This is important because a minority of a few hundred thousand would have a harder time mobilizing a large number of protesters than a minority of several million. The variable was designed this way due to limitations on the ability to collect specific information in most cases. While this is clearly a drawback, the variable still provides a reasonable estimation of the phenomenon which it measures.

55. Rebellion is coded on the following scale:

0. None.

1. Political banditry, sporadic terrorism.

2. Campaigns of terrorism.

3. Local rebellions: armed attempts to seize power in a locale. If they prove to be the opening round in what becomes a protracted guerrilla or civil war during the year being coded, code the latter rather than local rebellion. Code declarations of independence by a minority-controlled regional government here.

4. Small-scale guerrilla activity. [small-scale guerrilla activity has all these three traits: fewer than 1000 armed fighters; sporadic armed attacks (less than six reported per year); and attacks in a small part of the area occupied by the group, or in one or two other locales).]

5. Intermediate-scale guerrilla activity. [intermediate-scale guerrilla activity has one or two of the defining traits of large-scale activity and one or two of the defining traits of small-scale activity.]

6. Large-scale guerrilla activity. [large-scale guerrilla activity has all these traits: more than 1,000 armed fighters; frequent armed attacks (more than six reported per year); and attacks affecting a large part of the area occupied by group.]

7. Protracted civil war, fought by rebel military with base areas.

56. For more details, see Keith Jagger and Ted R. Gurr, "Tracking Democracy's

Third Wave with the Polity III Data," Journal of Peace Research 32, no.

4 (1995), p. 472.

Return to article

57. The level of religious discrimination in 1992-93 (RDISAL93) suffered by

the Armenians in Azerbaijan is coded as 4 and the level of religious grievances

expressed in the same period (RGRV93) is 2.

Return to article

58. See Gurr, Minorities at Risk, pp. 144-46.

Return to article

59. Tilly, From Mobilization to Revolution; and Mark I. Lichbach, "Deterrence

or Escalation? The Puzzle of Aggregate Studies of Repression and Dissent,"

Journal of Conflict Resolution 31 (1987).

Return to article

60. Gurr and Moore, "Ethnopolitical Rebellion," pp. 1082-85.

Return to article

61. The level of protest by Copts for each year between 1990 and 1995 is 1

- verbal opposition.

Return to article

62. Religious legitimacy (RLEG) is coded as 3 (out of a possible 4) in Egypt

for all years between 1990 and 1995. This description is based on the Minorities

at Risk report on the Copts in Egypt written by the author. The report is available

at http://www.bsos.umd.edu/cidcm/mar.

Return to article

63. Religious legitimacy (RLEG) is coded as 0 in France for all years between

1990 and 1995.

Return to article

64. This description is based on the author's Minorities at Risk report on

the Muslims in France. The report is available at http://www.bsos.umd.edu/ cidcm/mar.

Return to article

65. Gurr, Minorities at Risk; Gurr, "When Minorities Rebel."

Return to article

66. Ibid.

Return to article

67. See Jagger and Gurr, "Tracking," for details.

Return to article

68. Fox, "The Effects,"; and "Towards a Dynamic."

Return to article

69. Ted R. Gurr, "War, Revolution, and the Growth of the Coercive State,"

Comparative Political Studies 21, no. 1 (April 1988); Gurr, Minorities at Risk,

p. 137; and Ted R. Gurr, "Minorities, Nationalists, and Ethnopolitical

Conflict," in Crocker and Hampson, eds., Managing Global Chaos, p. 69;

Gurr and Harff, Ethnic Conflict, p. 85; Fox, "The Effects," pp. 58-59.

Return to article

70. One example of the fact that predictions of religion's demise are still

given credence is that an entire issue of Sociology of Religion 60, no. 3 (1999)

was devoted to the debate over this topic.

Return to article

71. Fox, "The Salience."

Return to article

72. Rummel, "Collective Violence."

Return to article

73. Gurr, Minorities at Risk; and "Why Minorities Rebel."

Return to article