by Hemda Ben-Yehuda

INTRODUCTION

How important is territoriality in explaining international conflict? In order to devise a theory of territoriality, the nature of territory�s impact on war must be explained. In other words political scientists should investigate what it is in territoriality that triggers interstate conflict, crisis and war. This article should be regarded as an effort toward the strengthening of such a theory, though its goals are very specific: to focus on several aspects of territoriality and establish their empirical links to violence in the protracted Arab-Israel conflict. 1 The study will examine three core questions. First, does the nature of a rivalry affect its attributes, namely, do the profiles of territorial and non-territorial crises differ? Second, does the location of states in a conflict situation affect their behavior, that is, do the profiles of crises with contiguous adversaries differ from those with non-contiguous actors? Third, does empirical data on international crises in a protracted conflict support central hypotheses from the territory-war literature?

This study focuses on interstate rivalry. A rivalry �characterizes a competitive relationship between two actors over an issue that is of highest salience to them.�2 We will distinguish between rivalry over territorial issues and rivalries over other issues. The former include conflicts in which territory is the main issue of contention among adversaries, whereas the latter may contain a territorial element but it is not regarded as the core domain over which the adversaries confront one another. By introducing an issue-oriented typology of international crises, we highlight two major and at times overlapping issues: territoriality and ethnicity.3 But even within the salient issue in any given rivalry, states often fight over other stakes, since �the number of disputed questions, or stakes, that are seen as part of the same issue can vary.�4 Consequently, territoriality (or ethnicity) may therefore be an issue or a stake or both, manifesting itself in rivalry, crisis and war.

In operational terms we will describe territoriality as one of the issues on which interstate rivalry manifests itself and also as a contiguity aspect that characterizes the location of the contending states. The former seeks to assess the impact of territoriality as an issue over which adversaries contend, whereas the latter views territorial location as a contextual element which affects conflict among nations. To examine both factors, the article will compare two pairs of crisis profiles: the first is type of rivalry: the centrality of territory as a core issue versus other non-territorial interstate conflicts; and the second is location of adversaries: identifying contiguous neighbors versus distant states in conflict.

The dependent variable in this study will be violence, not war alone. The 25 crises of the Arab-Israel conflict identified by the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) project data set over the 1947-94 period, will be tested in order to examine the effects of territoriality on the level of interstate violence.5 Diversity in issues and location is expected to result in distinct levels of violence and to affect the termination of any particular crisis and the dynamics of the protracted conflict as a whole.

TOWARD A TERRITORIAL EXPLANATION OF WAR

In The War Puzzle, John Vasquez raises some of the most salient questions in the field of International Relations (IR). �Why does war occur? Why do some wars expand to encompass the entire system? Can more peaceful structures be built?�6 One of the core explanatory variables for the war puzzle is territoriality. Three theoretical approaches attempt to explain the relationship between territory and violence: proximity, interactions and territorial issues.7� Though all these approaches focus on aspects of territory, the reasoning they offer and the validity of their explanations differ.

The proximity approach suggests that the relationship between contiguity and war is due to the proximity among adversaries.8 Distance usually places a restriction on the ability of most states to wage wars against states located far away.� Moreover, it is also likely that distant states will have little interaction and therefore no stakes to fight over. Two major restrictions exist with respect to this explanation.� First, proximity is a constant among states whereas war is not. Hence a logical flow arises: a constant cannot explain a variable - the changes that occur in world politics from peace to war and back to peace again must be affected by other factors, not contiguity alone.Second, the proximity explanation is closely related to the realist approach and seems almost a replica of the �power predicts behavior� theory. In effect, proximity may produce an opportunity for neighboring states to fight but it does not explain changes in motivation to do so.9 Empirical evidence also sheds some doubt on this approach, since with the advance of technology, we should find that more distant states have the ability to wage wars, and therefore that the frequency of wars between non-contingent states should increase. Yet, in reality this is not the case.10

The interaction approach tries to strengthen the proximity explanation by introducing a substantive element that is subsumed in contiguity: friction between neighbors. Contiguous states fight not only because they are close and therefore able to do so, but because their location creates an increase in interactions among them, thereby raising the probability that state interests will conflict, leading to crisis and war. This input serves us well since it explains some instances where the location of states creates a struggle concerning topics regarded by all sides as worth getting involved in a confrontation over. However, a higher volume of interactions may lead to war or to peace. When departing from the realist assumptions of constant conflict and adopting the assertions of the liberal school, explanations that derive from the interaction approach result in a paradox: an increase in interactions could also mean more interdependence and thereby a more peaceful environment.11 When do realist or liberal assumptions hold? What explains a shift from intense conflict to regional cooperation? The interaction approach does not provide answers to these questions and therefore its value in explaining the dynamics of war and peace is somewhat limited.

The territoriality approach focuses on territory as the most important � issue dividing rival states. Territorial issues create motivation for waging war. However, unlike research on proximity or interaction, advocates of territoriality emphasize the substance of contention: �what makes for war is that territory once seen as legitimately owned will � be defended by the use of violence where other issues are less likely to be.�12� Moreover, when defining a territorial issue, territoriality should not be viewed in a narrow sense:�it is not territoriality per se, but food and resources on the territory or the lack of them that may be the ultimate factor that makes territory so prone to violence.�13

In a comprehensive study of territorial rivalries, Paul Huth defines a territorial dispute as, �either a disagreement between states over where their common homeland or colonial borders should be fixed, or, more fundamentally, the dispute entails one country contesting the right of another country even to exercise sovereignty over some or all of its homeland or colonial territory.�14 � This definition sets forth a demarcation line between territorial rivalries and other� types of rivalry that include:

commerce/navigation, protecting national/commercial interests, protecting religious confreres, protecting ethnic confreres, defending an ally, ideological liberation, government composition, enforcing treaty terms, and balance of power, among others . . ..The presence of these non-territorial issues are important because they show that territoriality is not being so broadly defined so as to include every possible issue that might lead to war.15

While focusing on territorial issues, Vasquez also makes a clear distinction between issues and stakes and is aware of the diversity in stakes within a single issue. Moreover, he recognizes that territoriality may be a stake in a non-territorial issue:�a number of other issues appearing frequently as a source of war have a territorial dimension to them. These include such issues as: the creation (or unification) of a national state, maintaining the integrity of a state or empire, empire creation, state/regime survival, and dynastic rights/succession.�16 � Similarly, in his study of 129 cases of territorial disputes over the 1950-90 period, Huth also identifies several stakes that are part of the larger territorial issue. These include strategic location, support for minorities, political unification and economics.17 � These stakes are the more specific and short range bones of contention over which states engulfed in territorial disputes confront one another.

Though territoriality is a core issue explaining state resort to violence, it is not regarded as a deterministic factor, nor does it appear to be an automatic element that motivates nations to start a war. States are learning entities, they learn to fight wars but also to gain advantages from peace. Moreover, war often ends with a decisive allocation of resources among rivals thereby paving the road to coexistence and lower conflict. The merit of the territoriality explanation is in its ability to answer our queries over war but also over the puzzle oftransition to peace. Hence, it does not assume a constant situation of rivalry among neighbors. Nor does it necessarily adopt the realist assertions about the dominance of conflict interactions in interstate relations.Territorial issues, more than others over which states confront one another, are likely to lead to wars. But nations learn from wars and some wars lead to the resolution of territorial disputes. Unlike the two other explanations, the territorial approach accepts the fact that territorial differences can be solved, and therefore that states may reach peaceful periods in their relationships.

Yet some gaps do appear in the territoriality approach. When rival approaches attempt to explain identical findings, more empirical testing is necessary, utilization of diverse sources is recommended and cross-validation of theory is required.However, additional empirical research cannot be a substitute for essential theoretical refinements. � These must provide us with suggestive clues on several topics.First, what is the impact of territorial issues and stakes on state behavior in crises? � Second, why do some wars lead to longer peaceful periods than others?And finally, if war is not a constant even among neighboring rivals, when and what type of territorial stakes can be solved without war?

The present study suggests two new inputs to the theoretical debate. � First, rather than focus on rivalry and war, we will concentrate on international crisis. The outbreak of an international crisis will serve as an indicator of emerging and/or ongoing conflict over territorial and other issues, as well as of an incipient war. � If one attempts to understand how nations handle their territorial disputes, crisis is an essential tool since it highlights the escalation period that leads to war. Moreover, some crises do not lead to war, so research can probe the dynamics of war as well as its prevention.The analysis of territoriality as an issue in crises is based on an issue-oriented typology of international crises, on the identification of more specific stakes among rivals, as well as on the contiguity element between the contending adversaries.

Second, all crises end, and the way they are resolved affects the extent of future interstate confrontation. We propose that the outcomes of crises can serve as a useful indicator to determine whether territorial and other issues � will be satisfactorily resolved or lead to further conflict.18

On the whole, there are two ways to treat the three territorial approaches to war: to focus on their diversity and to test their relative impact on the onset of crisis and violence, or to group them as one factor, territoriality. In this article I chose the former, so as to identify the specific contribution of the territorial element with its two operational variables: rivalry issues and location of adversaries.

TERRITORIALITY

AND INTERNATIONAL CRISES:

CONCEPTS,

TYPOLOGY AND VARIABLES

At the core of this analysis is a distinction between territorial and non-territorial rivalries that express themselves in the form of international crises. � Such rivalries differ in the primary � issue over which the adversaries disagree. Recognizing this diversity, ICB distinguishes between two types of international crisis: those that focus primarily on a territorial issue and other crises in which the territorial issue is not the core issue. For the purpose of this study, we call the former territorial rivalries and the latter non-territorial. This classification is based on the identification of issues of contention between rivals. � Only when the most salient issue is territorial will the crisis be classified as a territorial one.

The analysis of territorial and non-territorial issues, which are stipulated herein to affect state behavior in crises, is based on an issue oriented typology of international crises. This typology integrates two leading International Relations research fields: territoriality and ethnicity. Though these two fields produced a wealth of findings they were not yet linked to one another.19 Combining these two prominent sources of conflict between states and other actors in world politics, yields a fivefold typology of international crises, consisting of three territorial type crises (categories 1-3 below), three ethnic type cases (categories 2-4) and one type (category 5) which does not belong to either group. Table 1 below summarizes the five categories in this typology together with illustrations of crises that belong to each type of crisis.

TABLE 1: An issue-oriented typology of international crises

Type 1.�� Territorial-interstate

A crisis in which two or more states confront one another over territorial issues that are the most pronounced and long-term elements in conflict among them. For example, in the 1973 October -Yom Kippur War, Egypt, Syria and Israel became engulfed in a full-scale war crisis over their territorial conflict which dated back to the Israeli conquest of Arab territories in the 1967 Six Day War.

Type � 2. Territorial-irredentist ��

A crisis in which two or more states confront one another over a territorial issue that contains a significant ethnic dimension and that leads to a fundamental and long-term clash of interests among them. � It involves a claim by one state to a territory under the control of the other which is based on the existence of ethnic minorities residing in that territory. This category of cases does not apply to the Arab-Israel conflict at present, since a Palestinian state does not exist. However, its creation in the future may induce such a case when the newly established Palestinian state demands Israeli/Jordanian territory on the basis of the Palestinian population residing in those areas. Irredentist crises in other conflicts include the 1991 Gulf War, which commenced as a consequence of Saddam Hussein�s claim that Kuwait was an integral part of Iraq. Indeed, the swift Iraqi invasion of Kuwait was designed to satisfy this claim. Upon the entry of the US into the crisis realm, events rapidly escalated to more than just another regional irredentist confrontation between Iraq and Kuwait, as had been the case in 1961, illustrating the dangers of irredenta in world politics.

Type � 3. Territorial-secessionist

A crisis similar to Type 2, except that it arises primarily on the basis that an ethnic minority in one state will demand to secede and join an ethnic majority in another state. As in Type 2, this category of cases could emerge in the future as a threat to both Israel and Jordan, where Palestinians reside and might demand to join a newly established Palestinian state. The 1938 Munich case, which followed the annexation of Austria by Germany, is an additional well-known secessionist case. The German-speaking areas of Czechoslovakia demanded to be part of Hitler�s Germany, thereby threatening the territorial integrity of Czechoslovakia. � During the September events, this threat materialized when Germany supported the Sudeten Germans� demands for self-determination. Unfortunately, Western appeasement policy in this secessionist crisis forced Czechoslovakia to comply with these territorial-ethnic demands and thereby pay the price Hitler requested.

Type � 4.� Ethnic non-territorial

A crisis in which two or more states, as well as an ethnic actor, � confront one another over non-territorial issues. The ethnic-group � plays a central role in the confrontation in order to promote its non-territorial goals. 20� The 1976 Entebbe crisis falls in this category, as no territorial element was at the core of the confrontation between Israel, Uganda and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) Baader Meinhof hijackers, after the civilian Air France jetliner, en route from � Tel-Aviv to Paris,was forced to land in Uganda, and its Israeli-Jewish passengers were held hostage, subject to demands raised by the terrorists.

Type � 5.� Other - non-territorial and non-ethnic

A crisis in which two or more states confront one another over non- territorial issues where no ethnic topic or actor is involved in their long-term clash of interests. The acute 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis clearly represents this category as it did not contain territorial or ethnic elements.

The importance of this issue-oriented typology of international crises is in the range of territorial and ethnic issues it introduces, differentiating between five types of crises. In crises which belong to types 2-4 an overlap occurs between territorial and ethnic elements, necessitating an in-depth analysis that would ascertain the respective effects and impact of each of these two elements. Cases in the territorial-interstate (type 1), ethnic-non-territorial (type 4), and other:non-territorial and non-ethnic (type 5) groups contain one of these elements alone and hence enable a more straight-forward analysis, in an attempt to analyze territoriality in crisis.��

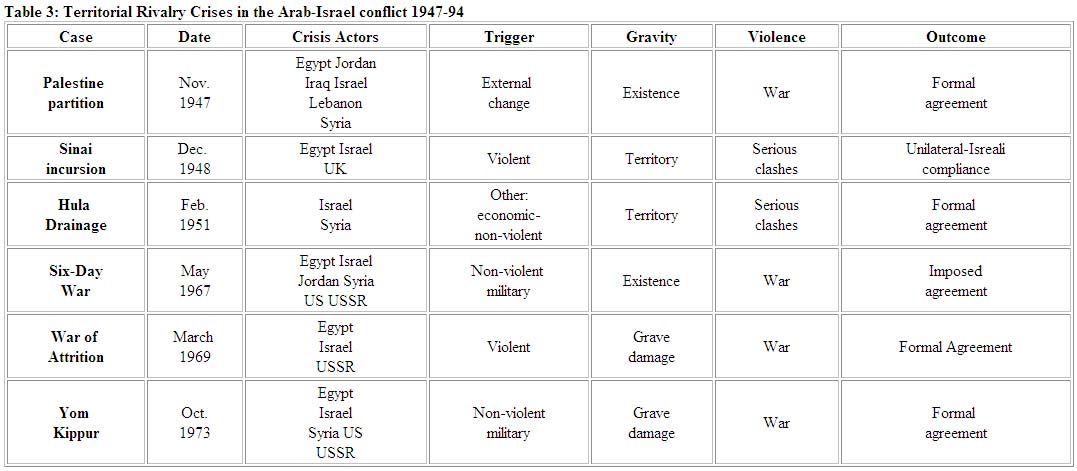

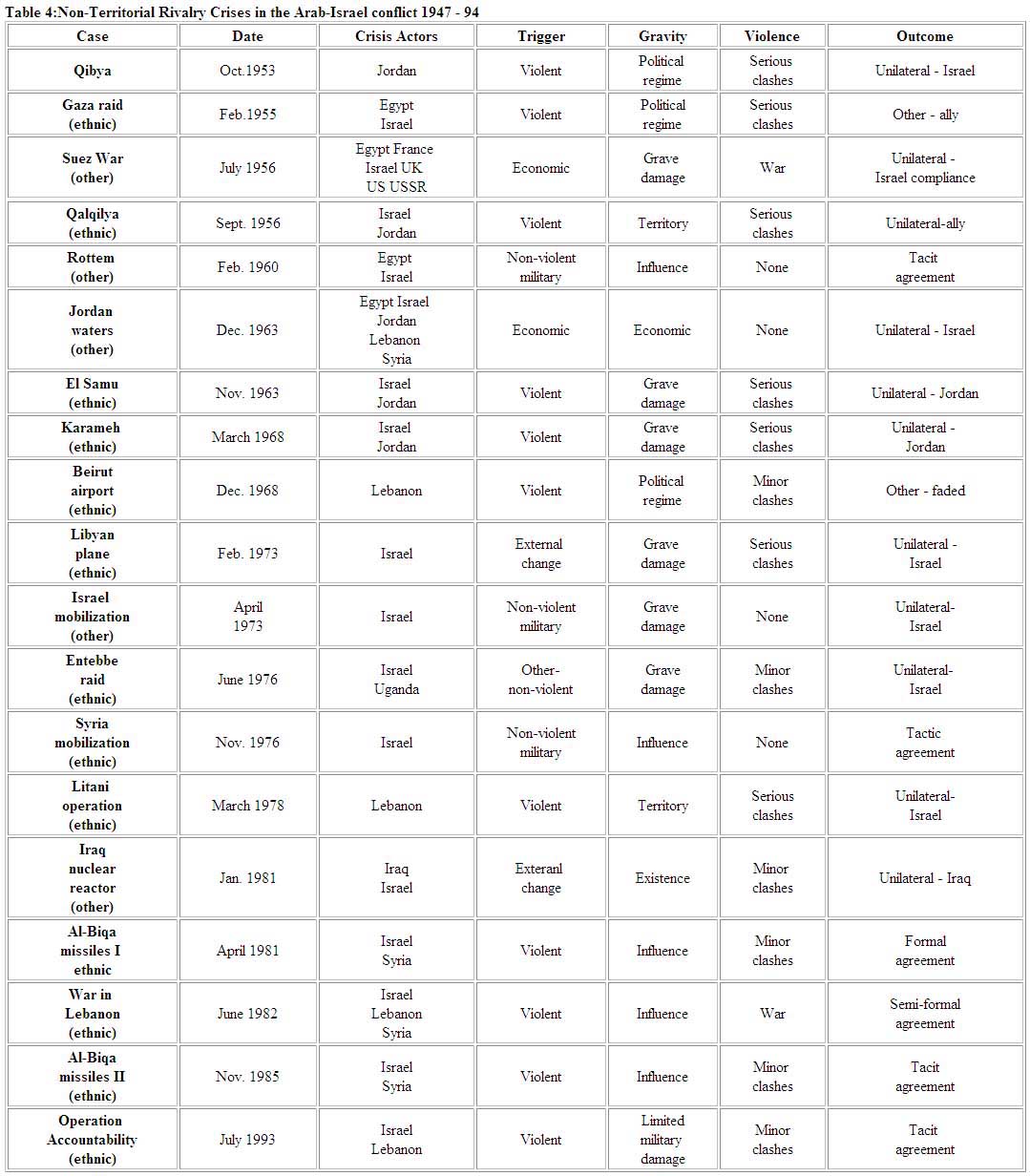

In the empirical section of this study, this typology will be applied to the 25 crises ICB identifies in the Arab-Israel conflict. Among these, six cases belong to the first category of territorial-interstate (see table 3 below) and 19 cases are ethnic-non-territorial or other:� non-territorial andnon-ethnic in issue, termed in short, non-territorial cases (see table 4). � Hence, this article probes only cases with no overlap between territoriality and ethnicity.

In sum, the study presents a theoretical framework and some preliminary findings which suggest that more cumulative studies should be directed to the links and spillover effects between territoriality and ethnicity in conflict, crisis and war.

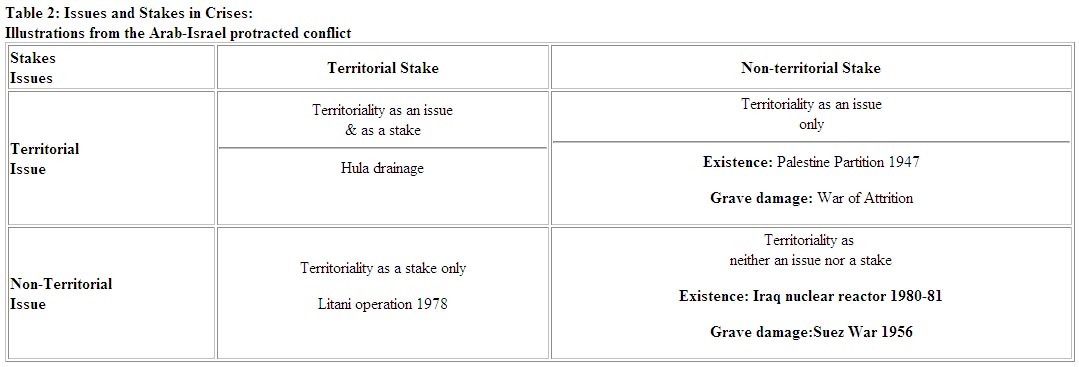

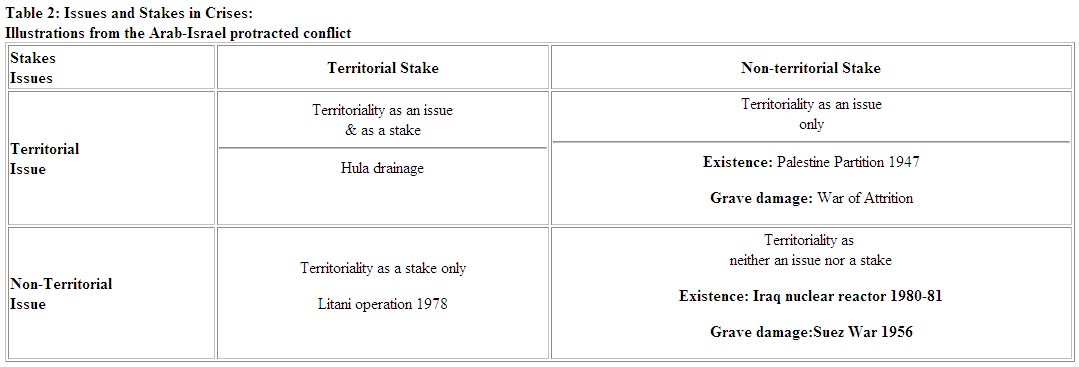

So far this article has focused on issues in crises. But states contend over stakes as well as over issues. Theoretically speaking, issues are not identical with stakes. Issues are broader in scope and endure longer,whereas stakes are more specific. Any issue may therefore encompass several stakes, some of which may gain prominence at certain times and others may fade, while the core issue endures. Following this theoretical distinction, territoriality may be an issue, or a stake, or both. � Often, as noted above, it appears as the most central issue in conflict, but it may also be a stake in a crisis, raised by one of the parties. A summary of issues and stakes in territorial and non-territorial rivalries is presented in Table 2 below.

As noted in table 2, examining the manifestations of territoriality in crises reveals four possible combinations. Territorial type rivalries often involve territorial stakes, but need not be confined to these stakes. By contrast, non-territorial rivalries in which the dominant issue is not territory may include, at times, a territorial stake. 21� To illustrate the different types of territorial issues and stakes in crises we turn to the Arab-Israel conflict. First among them are cases with territoriality as an issue but not a stake.� Both the 1947 Palestine partition-Israeli war of independence case, and the 1969 War of Attrition between Egypt and Israel, were territorial rivalry cases. In the former and first crisis in the Arab-Israel conflict, the UN proposal for theestablishment of two independent states - Jewish and Arab - triggered a prolonged crisis � in which five Arab states - Egypt, � Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria - resorted to violence in order to prevent the establishment of a Jewish state in what they considered to be Arab territory. In the 1969 case, Egypt initiated a war of attrition against the ongoing� Israeli occupation of the Sinai Peninsula, Egyptian territory that had been under Israeli control since the 1967 Six Day War. � Although both crises involved territorial issues, they varied in their more immediate stakes, namely in the specific threats they embodied.In the 1947 case, a peak level threat to Israel�s existence was the core stake in dispute, while in 1969 the threat was more limited, focusing on war-related grave damage.

TABLE 2: Issues and Stakes in Crises:

Illustrations from the Arab-Israel protracted conflict

Turning to crises with territoriality as both an issue and a stake the relevant case is the 1951 Hula Drainage crisis.The Israeli Land Development Company started drying 15,000 acres of marshes, so that they could be used for agriculture.� This was the immediate stake that led to the confrontation. But the broader issue of contention touched upon the Demilitarized Zone, defined earlier in their 1949 Armistice Agreement, as well as the location of the future border between Israel and Syria.

Not all the 25 Arab-Israel crises were straightforward territorial rivalries, because the core interstate issue in more than half of the cases was ethnic-non-territorial, involving a hostile spiral of Palestinian guerrilla and terror activity from the Arab states against Israel and Israeli reprisal acts designed to bring about an end to sub-state violence. style="mso-spacerun: yes">� In these crises, the stakes among state adversaries were the stability of domestic Arab regimes who were faced with Israeli military retaliation raids, an interstate competition over spheres of influence defined by regional powers in the midst of the lengthy Lebanese civil war and at times even territory - as a stake in a dispute over a non-territorial issue. �

More specifically, the 1978 Litani operation as well as the 1982 War in Lebanon are good examples for crises with territoriality as a stake but not as an issue. In the 1978 crisis, as a consequence of escalating PLO terror activity, the Israel Defense Force (IDF) invasion of Lebanon was geared to reduce the scope of Palestinian terror. � Though the prolonged presence of IDF troops in the area imposed a territorial threat to Lebanon, the major issue in this confrontation was that of PLO activity and its freedom of action within the sovereign Lebanese state.

Similarly, in 1982, intensified PLO military activity drew Israel, Lebanon and Syria into a prolonged war-crisis.Immediately at stake during this crisis was the large-scale Israeli invasion of � Lebanese territory, though once again, the dominant issue was not territorial but rather a question of � Palestinian presence in the country.

Turning to the last type, territoriality as neither a stake nor an issue, we find only a few crises, such as the 1956 Suez Canal nationalization war case and the 1981 Iraqi nuclear plant crisis, in which high-gravity threats of military-related grave damage and existence occurred even when the core issue among the adversaries was non-territorial.

During the 1956 Suez case, Israel was concerned with the growing tide of Egyptian radicalism, and alarmed over the dangerous consequences of a shift in the regional balance of power in favor of Egypt. Israel was also preoccupied with Nasser�s continued support to Palestinian infiltrators who were a persistent menace at that time. However, no substantive territorial issue or stake was raised by any of the participating states from the region or from outside the Middle East.

Similarly, during the 1981 Iraqi nuclear crisis, Israel initiated a surgical military attack against Osiraq, the Iraqi nuclear plant, in order to prevent Iraq from becoming a nuclear power in the region. Issues of Israeli existence and regional balance of power were pursued, but territorial elements were not present.

In short, territoriality often manifests itself in crises as a core issue or as a major stake over which states contend.� This study asserts that territoriality has a profound impact on patterns of state behavior in conflict, crisis and war.� In order to identify profiles of territorial and non-territorial rivalry and to explore the links between territoriality and crises, this analysis focuses on four main crisis attributes using the ICB variables of trigger, gravity, violence and outcomes.

The trigger of an international crisis is an event which sets forth a higher than normal escalation process between states. It denotes a change in behavior initiated by a state in one of the following domains: a violent act or a political, economic, non-violent or indirect violent act. Triggers may also involve an external change or an internal challenge to the regime of the adversary. In this study a distinction is made between two types of triggers: � violent ones and all other triggers that involve an increase in hostility without crossing the threshold of interstate violence.

Gravity of threat represents the short-range stakes between adversaries in territorial and non-territorial rivalries. Grouping ICB values for threats in an international crisis into two categories of low and high stakes, this study identifies high stakes to involve territorial threats as well as those to military-related grave damage and existence. Low stakes involve economic threats, as well as threats of limited military damage, threats to influence and to the stability of the political system.

Next, in this analysis the extent of violence used in an international crisis is examined. ICB identifies four levels of violence ranging from no violence at all, through minor and serious clashes to full-scale war. For the purpose of this study, the first two categories are considered as a low level of � violence while the latter two denote the high violence category.

Turning to the mode in which crises end, the different forms of crisis termination identified by ICB are grouped here into accommodative and non-accommodative outcomes. The former include formal, semi-formal and tacit agreements while non-accommodative termination takes the form of unilateral acts, imposed agreements and crises that fade with no agreed outcome.

The basic assumption raised in the territoriality literature is that territorial disputes are significantly different from non-territorial ones and therefore the behavioral patterns of states in these two distinct types of rivalry will vary. In the following analysis a detailed description of behavior patterns will be presented with special attention paid to the role of violence, in an effort to answer one core question: to what extent do territorial and non-territorial crises differ and in what aspects?

TERRITORIALITY AND VIOLENCE IN THE ARAB-ISRAEL CONFLICT

From its inception in 1947, the Arab-Israel conflict has been an existence conflict between neighboring states. An existence conflict is one �where the adversaries demand to be recognized as a distinct national entity and claim the same stretch of land as their sole territorial base.� 22 � Hence, territoriality and ethnicity in this case were core elements in the conflict.Yet, different crises focused on specific issues and stakes. The analysis presented below presents trends over time and describes frequency distributions. � I am aware that the sample of cases is small but the findings should be taken, primarily, as illustrations of the usefulness of the theoretical framework in the exploration of complex conflicts over time.

When a distinction is made between territorial and non-territorial rivalries which express themselves in the form of international crises, the distribution ofcases in both categories during the protracted Arab-Israel conflict is unequal: six territorial cases and 19 non-territorial ones. ICB data on the attributes of crises in the Arab-Israel conflict are presented in Table 3 for territorial rivalry cases, and in Table 4 for� non-territorial rivalry.23 This protracted conflict, with its 25 international crises from 1947 to 1994 identified by ICB,24 and the centrality of its violence which was present in all but four of the 25 crises, is regarded as a territorial confrontation among its principal adversaries. As such, it serves as a suitable microcosm for a close examination of a theory of territoriality, and as an interesting testing ground for exploring the links between territoriality, crisis and war.� The conflict dates back to the November 1947 UN General Assembly Resolution 181 that called for the partition of Palestine and the creation of two independent states, Jewish and Arab, one alongside the other.25 � Although the core issue in the conflict was and remained territorial, specific crises, as noted earlier, have focused on various stakes: territorial, influence, military-related damage, economic topics as well as aspects of internal� stability and maintenance of the regime in power. � In its early years, peak gravity was evident because the Arab adversaries were not willing to accept the existence of a Jewish state in the region, let alone agree to its territorial boundaries. � Hence, crises within the protracted conflict differ not only in their issues, thereby forming two types of � rivalry - territorial and non-territorial, but also in their stakes, that is in the specific threats that indicate the gravity of the various crises. While all territorial rivalry cases involve either existence, grave damage or territory with two crises (33.33 percent) for each of these stakes, in the non-territorial rivalry group the range of stakes is broader and the distribution within each stake varies: in six of these 19 cases, military-related grave damage is at stake (31.6 percent), in five of them influence (26.3 percent), in three political regime (15.8 percent), in two territorial aspects (10.5 percent) and existence, economic and limited military damage were evident in one case each (5.2 percent).26

TABLE 3: Territorial Rivalry Crises in the Arab-Israel conflict 1947-94

Since the 1978 Camp David peace process and the Egypt-Israel peace treaty, efforts toward a peaceful resolution of this conflict have shown some results. The dynamics in the Arab-Israel conflict combine both war and peace extremes of interstate interactions. This is notable both inthe frequency of crises over time, and the intensity of conflict which shifted from more to less intense hostility. Changes in conflict patterns and trends toward accommodation are especially important, because a theory of war should be tested not only in a violent context but also in a peaceful environment. � The relative decline in outbreak of interstate crises since 1985, and the more striking reduction in levels of violence employed by the adversaries since 1973,provide us with insights on territoriality�s impact on world politics during more peaceful periods in the region.27

TABLE 4: Non-Territorial Rivalry Crises in the Arab-Israel conflict 1947 - 94

Turning to the research questions presented in the first section of this study, we will now address two aspects of territoriality in crises, issues and location, in order to examine the effects of territoriality on basic crisis attributes: gravity of threat, onset of crisis, violence and outcomes. Diversity in crisis attributes will also enable us to explore some theoretical propositions on territory and war.

TERRITORIALITY AND GRAVITY OF THREAT

When stakes in crises are grouped into the two categories of low gravity (influence, political regime, economic and limited military damage) and high (existence, grave damage, territory), the profiles of territorial and non-territorial cases � differ. Table 5a presents data on stakes for these two groups of disputes. � Territorial disputes involve only high gravity stakes while the distribution of high and low stakes in non-territorial rivalries is almost equal, with 47.4 percent (n=9) and 52.6 percent (n=10) respectively. � These findings, as will be illustrated below, are expected to result in distinct levels � of violence as a mode of resolving disputes in territorial and non-territorial conflicts.

Table 5a: rivalry type and Gravity in the Arab-Israel conflict

| Rivalry type Gravity |

Territorial dispute |

Non-territorial dispute |

| High Gravity | n=6 100.0% |

n=9 47.4% |

| Low Gravity | n=0 0.0% |

n=10 52.6% |

Findings on low and high stakes for contiguous and non-contiguous states are presented in Table 5b. At first glance these figures may seem surprising: common sense expectations lead one to stipulate high gravity in contiguous cases and lower gravity in non-contiguous ones, yet all eight non-contiguous cases involve high gravity, and while more crises between contiguous adversaries appear in the category of high stake cases - some 57 percent � (n=13) of the total number - 43 percent (n=10) involve low gravity issues. A possible explanation for this contradiction is an overlap between contiguous and non-contiguous cases in the Arab-Israel conflict. To illustrate:� the 1947 Palestine partition involved Israel and Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon, all of which are contiguous states. However, Iraqi participation makes the crisis a non-contiguous case too. Similarly, in addition to the regional non-contiguous adversaries detailed in Tables 3 and 4, major powers were also involved in theseconfrontations. This was the case with UK participation in the 1948 Sinai incursion; in the 1956 Suez war with France, UK, US and USSR as distant states; in the 1967 and 1973 wars with both superpowers participating in the crises; and in � the 1969 war of attrition where direct, though limited, Soviet military involvement was observed. High gravity, therefore, was not only the result of contiguity but also of a power gap that was introduced by the participation of� major powers interacting in � regional events. The only purely regional non-contiguous cases were the 1976 Entebbe raid involving Israel and Uganda, and the 1981 Iraq nuclear reactor crisis, in which Israel and Iraq were the only participants.

Table 5b: Location and Gravity in the Arab-Israel conflict

| Location Gravity |

Contiguous states |

Non-contiguous states |

| High Gravity | n=13 57.0% |

n=8 100.0% |

| Low Gravity | n=10 43.0% |

n=0 0.0% |

Data, noted below,also indicate that crises in the Arab-Israel conflict differ in their triggers, levels of violence and outcomes. This diversity is present when territorial and non-territorial cases are compared, but also when neighbors and distant adversaries are considered, though the diversity � in the former is greater than in the latter. It demonstrates, therefore, that issues are more meaningful than contiguity as far as thelinks between territoriality and state behavior in crisis are concerned.

TERRITORIALITY AND CRISIS INITITATION

Data in Table 6a, on rivalry and crisis onset, illustrate that non-territorial crises are more likely to erupt with a violent trigger than territorial cases: � while 57.9 percent (n=11) of the former begin with a violent act and 42.1 percent (n=8) have non-violent triggers, the distribution for the territorial rivalry cases reverses the trend - only 33.3 percent (n=2) start violently and 66.66 percent (n=4) are initiated by non-violent modes. These results indicate that states are more willing to resort to violence when handling non-territorial disputes and are more reluctant to do so in territorial conflicts, perhaps due, as will be seen below, to the greater risk in the latter cases of escalation to full-scale war.

Table 6a: Rivalry type and Triggers in the Arab-Israel conflict

| Rivalry type Trigger |

Territorial dispute |

Non-territorial dispute |

| Violent Trigger | n=2 33.3% |

n=11 57.89% |

| Non-violent trigger |

n=4 66.66% |

n=8 42.11% |

Turning to location and triggers, Table 6b shows that contiguous states account for 57 percent (n=13) of the violent trigger cases and 43 percent (n=10) of non-violent ones, whereas in non-contiguous cases the gap between violent and non-violent triggers is much greater - 25 percent (n=2) and 75 percent (n=6) respectively. This means that, while states may be cautious with resort to violence in territorial disputes, contiguity still increases the prospect of the onset of violence.

Table 6b: Location and Triggers in the Arab-Israel conflict

| Location triggers |

Contiguous states |

Non-Contiguous states |

| Violent Trigger | n=13 57.0% |

n=2 25.0% |

| Non-violent trigger |

n=10 43.0% |

n=6 75.0% |

TERRITORIALITY AND VIOLENCE

As noted in Table 7a, all six territorial rivalry cases escalated to serious clashes/war, though only two of these cases erupted with a violent trigger.By contrast, the 19 non-territorial cases vary almost equally in their severity of violence: 52.63 percent (n=10) of these cases involved no violence or escalated only � to minor clashes, while 47.37 percent (n=9) of them manifested serious clashes and war.�

Table 7a: Rivalry type and Violence in the Arab-Israel conflict

| Rivalry type Violence |

Territorial dispute |

Non-territorial dispute |

| No-low violence | n=0 0.0% |

n=10 52.63% |

| Serious clashes - war |

n=6 100% |

n=9 47.37% |

Contiguity, as noted in Table 7b, leads to higher levels of violence, with 35 percent (n=8) of these cases involving no/low violence and 65 percent (n=15) with serious clashes/war. However, when non-contiguous states are involved in crises, the reverse is true, 75 percent (n=6) of the cases� involved no/low violence, and only 25 percent (n=2) developed to severe violence including war.

Table 7b: Location and Violence in the Arab-Israel conflict

| Location Violence |

Contiguous states |

Non-contiguous states |

| No-low violence | n=8 35.0% |

n=6 75.0% |

| Serious clashes - war |

n=15 65.0% |

n=2 25.0% |

When we evaluate violence, both as triggers and as a process of crisis escalation, it is clear that contiguity adds to the level of hostility, while territorial issues have a moderating effect on the onset of crises, but not on violent crisis escalation. Together, contiguity and territoriality add to thefrequency and severity of international crises in the Arab-Israel conflict. How can the recent processes of conflict resolution be reconciled with these findings? Both theory and findings provide an answer; territoriality explains not only war but also peace. War is a process by which a decisive mode of resource allocation is reached, and depending upon its termination, peaceful periods may exist between neighbors. An examination of crisis outcomes is essential in order to understand the shift from conflict to cooperation in the Middle East. �

TERRITORIALITY AND OUTCOMES

Tables 3 and 4 present data on the termination of crises. For the purpose of comparative analysis I have grouped these specific outcomes into two categories. The first, termed accommodative, involves formal and semi-formal agreements and tacit understandings. These are modes where the results of crisis confrontation and war are translated into political understandings between the contending parties, thereby adding to regional stability and increasing the prospects of conflict resolution. The second, called non-accommodative, includes unilateral acts that terminate crises, and imposed agreements. In such cases, no rules or regulations appear at the end of the confrontation. Hence, conflict is likely to escalate once again between adversaries at a later time. Moreover, in the case of an imposed agreement, grievances may even lead to greater regional turmoil.28 This was the case with the 1967 Six Day War, which ended with a UN ceasefire imposed � on the Arab states and Israel by the superpowers. Arab dissatisfaction with the 1967 debacle triggered their surprise attack against Israel which started the 1973 war. The October war was designed to enhance Arab dignity and to reactivate diplomatic processes that would bring an end to Israeli occupation of formerly Arab territories.

Data in Table 8a point to a clear conclusion: territorial cases are terminated by accommodative modes while the reverse is true for non-territorial crises. More specifically, 66.66 percent (n=4) of the territorial crises led to formal agreements, and only 33.33 percent (n=2) resulted in non-accommodative outcomes. The former include the 1948 Israeli War of Independence, the 1951 Hula Drainage crisis, as well as the 1969-70 War of Attrition and the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The exceptions to this rule are the 1948 Sinai incursion and the 1967 Six Day War.

By contrast, more often than not non-territorial disputes end in a non-accommodative manner; 68.42 percent (n=13) of the cases ended this way, while only 31.58 percent (n=6) concluded with an understanding between adversaries.All but one of these non-territorial crises where accommodative outcomes were reached involved � a competition of influence (1960 Rottem, 1976 Syria Mobilization, 1981 Al-Biqa I, 1982 War in Lebanon and 1985 Al Biqa II). Although the 1993 Operation Accountability case was geared to prevent military hostilities in northern Israel and was not directly a struggle of influence between Israel and Syria, it too followed the same pattern and ened with a tacit agreement.

Table 8a: Rivalry type and Outcomes in the Arab-Israel conflict

| Rivalry type outcome |

Territorial dispute |

Non-territorial dispute |

| Accommodative outcome |

n=4 66.66% |

n=6 31.58% |

| Non-accommodative outcome |

n=2 33.33% |

n=13 68.42% |

Table 8b indicates that contiguity does not have much impact on the modes of crisis termination in the Arab-Israel conflict.� Contiguous and distant states end more of their confrontations with non-accommodative than accommodative outcomes, and rather similar percentages are found in the distribution of cases: 60 percent in the former and 40 percent in the latter.

Table 8b: Location and Outcomes in the Arab-Israel conflict

| Location Outcome |

Contiguous states |

Non-Contiguous states |

| Accomodative outcome |

n=10 43.0% |

n=3 37.5% |

| Non-accommodative outcome |

n=13 57.0% |

n=5 62.5% |

In sum, this protracted conflict emerged from an existential-territorial rivalry between the Arab-Palestinian side and Israel. The high frequency of crises and war in the past half century supports the assertions of all three approaches on the link between territoriality and war. The proximity explanation sheds light on the primary rivals involved in crises: it highlights the fact that the actors located closest to Israel, the core of this territorial rivalry, are the most likely to participate in hostile confrontations. For these states, territory serves as an issue of contention because the boundary between them was never demarcated, let alone agreed upon.

The interaction approach provides us with insights on the links between interstate and sub-state confrontations. Since the major rivals are contiguous neighbors, and the territorial dispute was left unresolved, friction developed easily on territorial as well as on other stakes. Territorial rivalry led most frequently to war as in the 1947 Partition case and the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Other spheres of turmoil developed over economic issues, as was evident in the 1963-64 Jordan Waters case which was triggered by Israel�s insistence that the implementation of its national water carrier project would commence in spite of Arab opposition. Influence was at stake too, mainly because Israel and Syria were involved in the prolonged Lebanese civil war and hostilities were often the result of respective claims that influence zones were not adhered to by the adversary. The 1976 Syria mobilization case, as well as the later cases of Al Biqa I in 1981 and Al Biqa II in 1985, illustrate such events. Contiguity led often to escalation when a dyadic confrontation on a specific topic, such as the PLO�s presence in Lebanon and the 1982 Lebanon War case, developed into a multiple actor crisis involving clashes between the Israeli army and Syrian forces in the Biqavalley. Furthermore, in 11 of the 25 cases, interstate hostilities were a consequence of non-state actors - Arab Fedayeen groups in the fifties, PLO organizations � from the late sixties to the late eighties and fundamentalist Islamic organizations since then. These actors operated with various degrees of freedom in Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon, building their infrastructure in these Arab states, infiltrating their personnel into Israel and carrying out acts of sabotage. Jerusalem�s response was consistent: Arab regimes that permitted such organizations to maintain a presence on their soilwere responsible for the outcomes and were therefore subjected to harsh Israeli reprisals. In short, proximity led to sub-state penetration and to violent interstate behavior.

The territoriality approach is supported by findings on the frequency of war and on the links between crisis outcome and conflict resolution. It was these interstate confrontations on territorial issues that escalated to peak-level violence, and that since the 1979 Camp David process have led to a slowly evolving peace process in the Middle East.

TOWARD A THEORY OF TERRITORIALITY AND WAR

When elaborating on his assertionthat territoriality isthe most important driving force to war among rivals, Vasquez set forth two basic propositions and spelled out five hypotheses on war being affected by the issues in conflict among adversaries and by the extent of contiguity among them. 29 Huth spelled out other propositions focusing on territorial issues, the diverse stakes within these confrontations, as well as on their domestic and international contexts.30 I am proposing a �Modified Realist Model� on the basis of these hypotheses and am testing for territorial rivalries in the years 1950-90.� Empirical support presented by Vasquez31 and Huth32 point to the salience of the territorial element in explaining interstate confrontation and violence. The present article attempts to further the goals of knowledge accumulation and theory construction by examining these propositions and hypotheses with ICB data.33 Data on dyadic and multi-state crises in the Arab-Israel conflict are presented in Table 9a and 9b.

Table 9a: Territoriality and High Violence in the Arab-Israel conflict

| Rivalry type Location |

Territorial dispute |

Non-territorial dispute |

| Contiguous States |

(multi-state) 1948 - Sinai incursion (multi - state) 1951 - Hula Drainage (dyadic) 1967 - Six - Day War (multi-state) 1969-War of Attrition (multi-state) 1973 - Yom Kippur War (multi-state) |

1955 - Gaza raid (dyadic) 1956 - Suez War (multi - state) 1956 - Qalqilya (dyadic) 1963 - El Samu (dyadic) 1968 - Karameh (dyadic) 1973 - Libyan plane (dyadic) 1978 - Litani operation (dyadic) 1982 - War in Lebanon (multi-state) |

| Non-contiguous states |

(multi-state) 1948 - Sinai incursion (multi-state) 1967 - Six Day War (multi-state) 1969 - War of Attrition (multi-state) 1973 - Yom Kippur War (multi-state) |

Table 9b: Territoriality and No / Low Violence in the arab-Israel conflict

| Rivalry type Location |

Territorial dispute |

Non-territorial dispute |

| Contiguous States |

1963 - Jordan waters (multi-state) 1968 - Beirut airport (dyadic) 1973 - Israel mobilization (dyadic) 1976 - Syrian mobilization (dyadic) 1981 - Al-Biqa I (dyadic) 1985 - Al Biqa II (dyadic) 1993 - Operation Accountability dyadic |

|

| Non-contiguous states |

1981 - Iraq nuclear reactor (dyadic) |

Proposition 1: �Rivals that have territorial disputes are more apt to go to war directly with each other at some point in their history than those without territorial disputes. Hence, rivals that do not go to war should be those without territorial disputes.�34

This proposition was derived from the territoriality approach which deals with the substantive aspects of territory and� focused on the effects of territorial issues on violence in state behavior. I applied it in the present study to violence in crisis onset and to war as a mode of conflict resolution. Findings on territorial and non-territorial rivalries supported this proposition, on escalation to war but not on the use of violence in the onset of crisis. When crisis triggers were observed,territorial rivalries in this protracted conflict tended to be less prone than non-territorial ones to violent onset, thereby pointing tothe conclusion that territorial issues do not affect high levels of violence at the start of an international crisis.

Yet during the course of the crisis, the use of violence in territorial rivalries gained prominence and thus territorial rivalries were twice as likely as non-territorial ones to involve war, thereby supporting proposition 1 for violence that occurs during the crisis.

Proposition 2: �Rivals that go to war in the absence of territorial disputes should be involved in more multilateral wars than dyadic wars. Likewise, rivals that go to war in the absence of territorial disputes should be more likely to get involved in ongoing wars than at the beginning of wars.�35

This proposition was also derived from the territorial issues approach as it spelled out the relationship between non-territorial issues and war. It was applied to crises in the Arab-Israel conflict, for which the distinctions of dyadic interactions and wars had been specified. Data on territorial/non-territorial disputes and the types of violence they involve were presented in Tables 8a and 8b. Of the nine non-territorial rivalries seven cases were dyadic: 1953 Qibya, 1955 Gaza raid, 1956 Qalqilya, 1963 El Samu, 1968 Karameh, 1973 Libyan plane and 1978 Litani operation.In all these cases the level of violence was serious clashes short of full-scale war. Two cases were multi-state wars, and in both, violence reached its peak level involving six actors in the 1956 Suez War,� and three in the 1982 war in Lebanon.� The absence of dyadic war and the presence of two multi-state wars support both claims in proposition 2.� Non-territorial rivals tended to get involved in multi-state war rather than in dyadic war, and they tended to join the war in different stages. � Such was the case with France and the UK, who entered the 1956 war two days before the Israeli invasion of Sinai, and with Syria whose forces became involved with the advancing Israeli army in the Biqa valley, two days after the Israeli thrust into Lebanon began in 5 June 1982.

All five hypotheses specified below were derived from the contiguity approach and spell out expectations on the� relationships between contiguity and war.

Hypothesis 1: �Rival dyads that are contiguous are more apt to go to war at some point in their history than rival dyads that are not contiguous.�36

This hypothesis indicates the effects of location on war proneness between dyad rivals.Data in Table 6b reveal that 65 percent (n=15) of the contiguous cases involved serious clashes and war while only 25 percent (n=2) of the non-contiguous cases did so. When the distinction between dyadic and multi-state dyads was introduced, we found only two cases of non-contiguous dyads: the 1976 Entebbe raid, and the 1981 Iraq nuclear reactor attack. The first involved serious violence short of war, and the latter involved minor clashes. Hence, in the Arab-Israel conflict, non-contiguous dyad rivals did not go to war, and high levels of multi-state violence also tended to exclude non-contiguous states.

Hypothesis 2: �Rivalries involving contiguous states are more apt to end in dyadic war than rivalries involving noncontiguous states.�37

This hypothesis involves all rivalries between contiguous and non-contiguous states but relates specifically to dyadic war while the earlier one deals with dyadic pairs and war in general.As presented in Tables 11a and 11b and noted in hypothesis 1 above, of the 23 contiguous cases, 35 percent (n=8) involved no-low violence and 65 percent (n=15) involved serious clashes-war. Within the latter category, six cases involved (multi-state) full-scale war: 1947 Palestine partition, 1956 Sinai, 1967 Six Day War, 1969 War of Attrition, October 1973-Yom Kippur war and 1982 War in Lebanon. � Since all wars in the Arab-Israel conflict are multi-state wars, we were unable to apply this hypothesis but its counterpart on contiguity and multi-state war was examined in Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 3: �Noncontiguous rivals that go to war are more apt to be involved in multilateral wars than contiguous rivals that go to war.�38

This hypothesis probes the relationship between contiguous and non-contiguous rivals and multi-state war. Among the six multi-state wars in the Arab-Israel conflict, all were between contiguous rivals and only � two included non-contiguous states: 1947 Palestine partition-Israel war of Independence and 1956 Suez-Sinai war. Hence, findings did not support hypothesis 3. � All multi-state wars in the Arab-Israel conflict took place between neighbors whereas only rarely did distant states participate in these wars. These findings may be a specific attribute of regional wars and should be compared, in future research, with empirical evidence on other regions and on global wars.

Hypothesis 4:�Noncontiguous rivals that go to war are much more apt to join an ongoing war than contiguous dyads that go to war.�39

This hypothesis deals with the timing in which rivals go to war. The two cases in which non-contiguous states participated in a regional war did not support this hypothesissince in both cases the distant state did not join an ongoing war but initiated it: in the 1947 Palestine partition crisis,Iraq together with other Arab states invaded Israel after its declaration of independence, thereby starting the Israeli War of Independence. � In 1956, military operations began with a joint Anglo-French invasion ofthe canal zone in response to Egypt�s nationalization of the Suez canal, and Israel joined the war two days later. However, due to the small number of war cases with non-contiguous rivals, more comparative research on regional and global wars must take place before any conclusions can be reached.

Hypothesis 5:�In comparison to contiguous rivals, noncontiguous rivals will either have no war or be involved only in multilateral wars with rivals.�40

This hypothesis is a closederivative of hypothesis 3 which investigated the links between contiguity and multi-state war. This hypothesis is not supported by findings since only � 75 percent (n=6) of the non-contiguous cases did not involve serious clashes or war, but in 25 percent (n=2) full-scale war cases was evident, and in four additional cases (50 percent) some violence occurred. Correspondingly, � such was the case with respect to the distribution of contiguous cases: 35 percent (n=8) of them � escalated to full-scale war and in 17 percent (n=4) of them no violence occurred.

On the whole, this analysis of rivalry and location profiles, as well as the use of data on state behavior in crises to explore some leading hypotheses on the war-proneness of neighbors fighting over territorial issues point to a similar conclusion: the territoriality approach which focuses on issues provides better explanations than the contiguity approach which highlights the location aspect.

CONCLUSIONS:

UNDERSTANDING WAR AND PEACE IN INTERSTATE CRISES

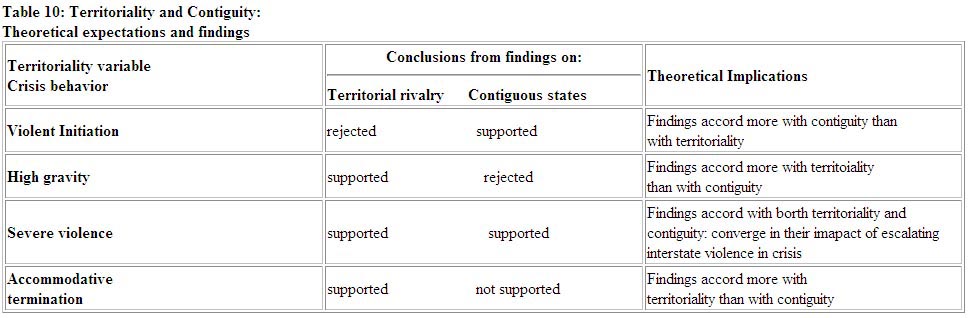

The goals of this article were to analyze territorial issues, stakes and the location of adversaries in crises and to establish their empirical links with state behavior: initiating crisis, resort to violence in coping with crisis, and modes of crisis termination. Findings on 25 crises that were part of the Arab-Israel protracted conflict served as our empirical field for exploring three core questions: first, does the type of rivalry affect its attributes? Second, does the location of states affect their behavior? Third, does empirical data on international crises and regional protracted conflicts support central hypotheses from the territory-war literature?� A summary of findings on territoriality and attributes of crises in the Arab-Israel conflict is presented in Table 10.

TABLE 10: Territoriality and Contiguity:

Theoretical expectations and findings

Most of the findings on state behavior in crises supported the assertions on territoriality and violence. Yet territoriality as an issue over which adversaries fight rather than merely territorial contiguity provided us with stronger links to their patterns of initiating and coping with crises. More specifically, the profiles of rivalry show distinct attributes for territorial and non-territorial rivalries, though not for all variables analyzed in this study. The same is true for profiles of location, with respect to neighbors and distant adversaries.

Initiation of international crisis, the first step in the escalation ladder between states was better explained by the contiguity factor than by issues. Data on crises that took place in the Arab-Israel conflict did not support the stipulated link between territorial rivalry and violent initiation. By contrast, territorial rivalry cases were initiated with less violence than their non-territorial counterparts. This pattern runs counter to the expectation that states will easily resort to violence when they seek to promote their territorial issues.� However, the location of adversaries did sustain theoretical expectations. Overall, neighbors were prone to much more violence in initiating crises than distant states.

Viewed together, it appears that the puzzle of violence in crisis initiation was only partly explained by territory. Since most crises do not erupt with full-scale war, and crisis management can at times prevent escalation to violence, more theoretical as well as empirical effort should be devoted to this domain in order to establish clearer conclusions.�

Gravity of threat denoting the stakes in crises was associated, as expected, with territoriality. Both territorial issues and location provide support for such links, though issues rendered a better explanation. High gravity stakes were more frequent in territorial rivalry cases than in non-territorial rivalries. This may be the result of the protracted territorial conflict that acted as a catalyst and therefore increased the gravity of any particular confrontation, which was not regarded by its participants as a separate crisis but rather as part of the ongoing rivalry.

Gravity was also associated with location. Yet in the Arab-Israel protracted conflict, it was the cases with non-contiguous states that entailed higher gravity. � The reason for this pattern in the Middle East was that most non-contiguous cases involved superpowers and therefore the stakes were higher in these crises than in others where only regional adversaries were present.Distance also implied a power gap in favor of a superpower and dangers of escalation to global confrontation. Closer observation of the contiguity factor in regional and global crises is necessary in order to ascertain that � the contiguity element alone and not the power dimension affects the gravity of stakes.

Violence in crises, the core aspect associated thus far with state hostility and violence,was supported by both the issue and location elements, thereby strengthening the assertions of both the territoriality and the contiguity approaches. Hence, territoriality as a substantive issue together with the location aspect characterizing the adversaries led to a converging force of higher interstate violence.

If territorial issues increased the motivation of states to use violence, location acted as a further element prompting such use. Proximity gave rise to the issue over which the adversaries confronted one another, but it also made the option of war possible for most rivals. While only very powerful states could afford to fight a distant enemy, most neighbors could confront one another with some chance of victory.

These results lead to a clear conclusion: the combination of a protracted territorial conflict, territorial issues in crises, and proximity among contending parties, is a formula for violent confrontations designed to reach a decisive allocation of the disputed territorial issues. But this inclination to violence and war has some positive element built into it,� through its effects on crisis termination and future conflict between rivals, as illustrated by findings on the termination of crises.

Outcomes, too, like violence, were linked to territory,� though territorial issues provided a better explanation than contiguity did. Territorial rivalries, more than others, were likely to end with formal, semi-formal or tacit understandings. By contrast, location did not yield support for the expected links between proximity and accommodative termination. In the Arab-Israel conflict minor differences were found in modes of crises termination when contiguous and non-contiguous states were compared. � The reason for this pattern of outcomes may derive from the fact that in the Middle East, superpowers as distant states acted not only as crisis escalators but also as managers, thereby leading to near equal prospects of resolution in contiguous cases with regional actors alone and in non-contiguous ones, i.e. those where powers from outside the region were involved.

The findings - that neighbors as well as distant states involved in a protracted conflict, end their crises in an accommodative way - raise the prospect that some of the issues they confront could be resolved and lead to a more stable relationship between them in the future. These results are especially important given our earlier findings on the resolution of territorial issues versus non-territorial ones. � The former were solved by an accommodative agreement in two thirds of the cases, the latter in only one third of them. Territoriality, in both of its aspects - issues and location - escalates interstate confrontations but also has a moderating effect on outcomes. Therefore, it is a central factor in explaining both war and peace between states.

A full theory of territoriality should explain war as well as peace and elaborate on how and when change occurs from war to peace.� Probing the link between territory and outcomes is one step in that direction. Obviously, a full theory of war and peace cannot be reached by a single explanatory variable, even one as powerful as territoriality. Future research will have to integrate the territoriality factor into a more encompassing model that will provide answers to these and other topics still left unexplained. The five fold issue-oriented typology introduced in this study suggests that multiple� overlapping effects exist between two core fields in international relations research: territoriality and ethnicity. Hence, not all cases of territorial confrontations are free of ethnic elements, and not all ethnic struggles are devoid of territorial elements.� Recognizing that such an overlap exists, more attention and research efforts should be devoted to a systematic comparison between these five types in order to discern the particular attributes of each group and the specific contributions of territoriality and other issues to state behavior in crisis. More area and issue specific comparative analysis of protracted conflicts and enduring rivalries is also needed in order to enhance our understandings of territoriality, war and peace in world politics.

Endnotes

1. This research continues the tradition and advantages of previous regionally oriented studies such as Kelly Philip, �Escalation of Regional Conflict: Testing The Shutterbelt Concept,� Political Geography Quarterly 5, no. 2 (1986), pp.161-80; John O�Loughlin and Luc Anselin, �Bringing Geography Back to the Study of International Relations: Spatial Dependence and Regional Context in Africa 1966-1978,� International Interactions 17, no. 1 (1991), pp. 29-61; Starr Harvey and Benjamin Most, �The Forms and Processes of War Diffusion, Research Update on Contagion in African Conflict,� Comparative Political Studies 18, no. 2 (1985), pp. 206-27.

Return to article2. John Vasquez, The War Puzzle (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 75; see also John Vasquez, �Distinguishing Rivals That Go to War From Those That Do Not: A Quantitative Comparative Case Study of Two Paths to War,� International Studies Quarterly 40, no. 4 (1996), pp. 532-33.

Return to article3. This typology also draws attention to the �other� category of crises which includes cases where issues were non-territorial and non-ethnic in nature, such as the 1962 acute Cuban Missile crisis. More theoretical effort should be made in the future in order to reach a more precise mapping of issues in world politics.

Return to article4. Vasquez, The War Puzzle, p. 77.

Return to article5. On the definition of an international crisis, see Michael Brecher and Hemda Ben-Yehuda �System and Crisis in International Politics,� Review of International Studies 11, no. 1 (1985), p. 23. For an analysis of state behavior in crisis, see some of the main ICB publications: Michael Brecher and Jonathan Wilkenfeld, Crises in the Twentieth Century: Vol. I. Handbook of International Crises (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1988); Michael Brecher and Jonathan Wilkenfeld, A Study of Crisis (Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan University Press, 1997); Jonathan Wilkenfeld and Michael Brecher, Crises in the Twentieth Century: Vol. II. Handbook of Foreign Policy Crises (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1988).

Return to article6. Vasquez, The War Puzzle, p. 123. � See also Hensel Paul, �Charting a Course to Conflict: Territorial Issues and Interstate Conflict, 1816-1992,� Conflict Management and Peace Science 15, no. 1 (1996), pp. 43-73; John Vasquez, ed., What Do We Know About War (Latham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2000); John Vasquez and Marie Henehan, �Territorial Disputes and the Probability of War, 1816-1992� Journal of Peace Research 38, no. 2 (2001), pp. 123-38.

Return to article7. See also Gary Goertz and Paul Diehl, Territorial Changes and International Conflict (London: Routledge, 1992).

Return to article8. On the contiguity approach and its critics, see, for example, Paul Diehl, �What Are They Fighting For? The Importance of Issues in International Conflict Research,� Journal of Peace Research 29, no. 3 (1992), pp. 333-44; David Garnham, �Dyadic International War, 1918-1965: The Role of Power Parity and Geographic Proximity,� Western Political Quarterly 39, no. 2 (1976), pp. 231-42; Charles Gochman, �Interstate Metrics: Conceptualizing, Operationalizing, and Measuring the Geographic Proximity of States Since the Congress of Vienna,� International Interactions 17, no. 1 (1991), pp. 93-112; Douglas Lemke, �The Tyranny of Distance: Redefining Relevant Dyads,� International Interactions 21, no. 1 (1995), pp. 23-38; Maoz Zeev and Bruce Russett, �Alliances, Contiguity, Wealth, and Political Stability: Is the Lack of Conflict Among Democracies A Statistical Artifact?� International Interactions 17, no. 3 (1992), pp. 245-67; Vasquez, The War Puzzle; and Vasquez, �Distinguishing Rivals.�

Return to article9. On the distinction between opportunity and motivation in shaping state behavior, see Benjamin Most and Harvey Starr, Inquiry, Logic and International Politics (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1989); Harvey Starr, �'Opportunity� and 'Willingness� as Ordering Concepts in the Study of War,� International Interactions 4, no. 4 (1978), pp. 363-87.

Return to article10. �� On this contradiction between theory and evidence, see John Vasquez, �Why Do Neighbors Fight? Proximity, Interaction, or Territoriality,� Journal of Peace Research 32, no. 3 (1995), p. 281.

Return to article11. �� On the liberal approach, see for example Rummel Rudolph, �Liberalism and International Violence,� Journal of Conflict Resolution 27, no. 1 (1993), pp. 27-71. ��

Return to article12. �� Vasquez, The War Puzzle, p.138; see also Paul Huth, Standing Your Ground: Territorial Disputes and International Conflicts (Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan University Press, 1996), p. 9.

Return to article13. �� Vasquez, The War Puzzle, p. 142.

Return to article14. �� Huth, Standing Your Ground, p. 19.

Return to article15. �� Vasquez, The War Puzzle, pp. 130-31; see also Kalevi Holsti, Peace and War: Armed Conflicts and International Order 1648-1989 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

Return to article16. �� Vasquez, The War Puzzle, p. 129.

Return to article17. �� Huth, Standing Your Ground, pp. 49-53.

Return to article18. �� Other studies that emphasize the importance of outcomes, not war alone are Eric Herring, Danger and Opportunity: Explaining International Crisis Outcomes (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1995); Henk Houweling and Jan Siccama, �The Epidemiology of War, 1816-1980,� Journal of Conflict Resolution 29, no. 4 (1985), pp. 641-63; John Nevin, �War Initiation and Selection by Consequences,� Journal of Peace Research 33, no. 1 (1996), pp. 99-108; and William Thompson, �The Consequences of War,� International Interactions 19, no. 1-2 (1993), pp. 125-47. Outcomes are crucial since studies point to the fact that wars are contagious and war triggers war. To understand why some wars lead to more peaceful periods and others don�t, research should probe the mode in which wars end, namely the modes of crisis termination.

Return to article19. �� For some recent studies on Ethnicity and violence in world politics, see Brecher and Wilkenfeld, � A Study of Crisis; David Carment, �The International Dimensions of Ethnic Conflict : Concepts, Indicators, and Theory,� Journal of Peace Research 30, no. 2 (1993), pp. 137-50; David Carment and Patrick James, eds., Peace in the Midst of Wars: Preventing and Managing Ethnic Conflicts (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, 1998); David Carment and Patrick James, �The United Nations at 50: Managing Ethnic Crises - Past and Present,� Journal of Peace Research 35, no. 1 (1998), pp. 61-82; David Carment and Patrick James, eds., Wars in the Midst of Peace (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1997); Ted Robert Gurr, �Why Minorities Rebel: A Global Analysis of Communal Mobilization and Conflict since 1945,� International Political Science Review 14, no. 2 (1993), pp. 161-201; Ted Robert Gurr, Minorities At Risk: A Global View of Ethnopolitical Conflicts (Washington, DC: Institution of Peace Press, 1993); Ted Robert Gurr and Barbara Harf, Ethnic Conflict in World Politics (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994); Ted Robert Gurr and Will Moore, �Ethnopolitical Rebellion: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the 1980s with Risk Assessments for the 1990s,� American Journal of Political Science 41, no. 4 (1997), pp.1079-103.

Return to article20. �� The different types of non-territorial-ethnic issues have been elaborated in Hemda Ben-Yehuda and Meirav Mishali, �Non-State Actors and Interstate Crisis: The Palestinian Dimensions in the Arab-Israel Conflict, 1947-1997,�Paper presented to the 39th Annual International Studies Association, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1998.��

Return to article21. �� At the system level, ICB identifies several types of value threat in an international crisis: existence, grave damage, territory, influence, political regime, economic and limited military damage. To determine the gravity of an international crisis, the coders were instructed to assign the value threat that was the core stake among its participants. We use the ICB gravity variable to operationalize various stakes in dispute.

Return to article22. �� Yehudit Auerbach and Hemda Ben-Yehuda �Attitudes towards an Existence Conflict: Begin and Dayan on the Palestinian Issue,� International Interactions 13, no. 4 (1987), p. 324.

Return to article23. �� For earlier ICB studies on the Middle East and the Arab-Israel conflict, see Hemda Ben-Yehuda and Shmuel Sandler, �Crisis Magnitude and International Conflict: Changes in the Arab-Israel Dispute,� Journal of Peace Research 35, no. 1 (1998), pp. 83-109; Michael Brecher and Patrick James, �International Crises in the Middle East, 1929-1979: Immediate Severity and Long-Term Importance,� The Jerusalem Journal of International Relations 9, no. 2 (1987), pp. 1-42; Michael Brecher and Patrick James, �Crisis Management in the Arab-Israeli Conflict,� in Gabriel Ben-Dor and David Dewitt, eds., Conflict Management in the Middle East (Lexington, MA.: Lexington Books, 1987), pp. 3-28; Naveh Hanan and Michael Brecher, �Patterns of International Crises in the Middle East, 1938-1975: Preliminary Findings,� in �Studies in Crisis Behavior,� The Jerusalem Journal of International Relations (Special Issue) 3, nos. 2-3 (1978), pp. 277-315. Other studies on the same topic are David Kinsella and Herbert Tillema, �Arms and Aggression in the Middle East: Overt Military Interventions, 1948-1991,� Journal of Conflict Resolution 39, no. 2 (1995), pp. 306-29; and Shmuel Sandler, �The Protracted Arab Israeli Conflict: A Temporal Spatial Analysis,� The Jerusalem Journal of International Relations 10, no. 4 (1988), pp. 54-78, who focus on the international level, as well as Zeev Maoz and Allison Astorino, �Waging War, Waging Peace: Decision Making and Bargaining in the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1970-1973,� International Studies Quarterly 36, no. 4 (1992), pp. 373-99, who examine the decision maker�s aspect of crisis.

Return to article24. �� An additional case, known as Grapes of Wrath, occurred in 1996 and accords with ICB definitions, but it is not included in this analysis since ICB data, so far, is coded only up to 1994.

Return to article25. �� On the term Protracted Conflict, see Edward Azar, �Protracted International Conflicts: Ten Propositions,� International Interactions 12, no. 1 (1985), pp. 59-70; Edward Azar, �Peace Amidst Development: A Conceptual Agenda for Conflict and Peace Research,� International Interactions 6, no. 2 (1979), pp. 123-43; Edward Azar, Paul Jureidini and Ronald McLaurin, �Protracted Social Conflict: Theory and Practice in the Middle East,� Journal of Palestine Studies 8, no. 1 (1978), pp. 41-60; as well as Michael Brecher, Crises in World Politics: Theory and Reality (Oxford: Pergamon, 1993); and Michael Brecher, �International Crises and Protracted Conflicts,� International Interactions 11, nos. 3-4 (1984), pp. 237-97.The concept of a protracted conflict is the counterpart in crisis research to the term enduring rivalries in war research. On the latter, see Gary Goertz, �The Initiation and Termination of Enduring Rivalries: The Impact of Political Shocks,� American Journal of Political Science 39, no. 1 (1995), pp. 30-52; Gary Goertz and Paul Diehl, �Taking 'Enduring� Out of Enduring Rivalry: The Rivalry approach to War and Peace,� International Interactions 1, no. 3 (1996), pp. 291-308; Gary Goertz and Paul Diehl, �Enduring Rivalries: Theoretical constructs and Empirical Patterns,� International Studies Quarterly 37, no. 2 (1993), pp. 147-71; Charles Gochman, �The Evolution of Disputes,� International Interactions 19, no. 1-2 (1993), pp. 49-76; Charles Gochman and Zeev Maoz, �Militarized Interstate Disputes 1816-1976: Procedures, Patterns, Insights,� Journal of Conflict Resolution 28, no. 4 (1984), pp. 585-615; Stephen Kocs, �Territorial Disputes and Interstate War, 1945-1987,� The Journal of Politics 57, no. 1 (1995), pp. 159-75; Rodolph Siverson and Ross Miller, �The Escalation of Disputes to War,� International Interactions 19, nos. 1-2 (1993), pp. 77-97; William Thompson �Principal Rivalries,� Journal of Conflict Resolution 39, no. 2 (1995), pp. 195-223.

Return to article26. �� The percentages presented herein and throughout the study serve as a means for comparison between values of any variable described in a particular section. Due to the relatively small number of cases we refrain from using more advanced statistical analysis at this point. Descriptive rather than causal analysis is therefore the core focus in this study.

Return to article27. �� On the dynamics of crises in the Arab-Israel conflict, see Ben-Yehuda and Sandler, �Crisis Magnitude and International Conflict.�

Return to article28. �� Cases ending with �other� are also included in the non-accommodative category since these crises involve bilateral acts with allies that have no impact on resolution of issues between adversaries (1955 Gaza raid), or crises that fade, without solving the protracted conflict (1968 Beirut airport).

Return to article29. �� Vasquez, �Distinguishing Rivals,� p. 537.

Return to article30. �� Huth, Standing Your Ground, chap 3.

Return to article31. �� Vasquez, �Distinguishing Rivals,� pp. 555-56.

Return to article32. �� Huth, Standing Your Ground, chap 4, 5, 6.

Return to article33. �� The hypotheses set forth by Paul Huth are not tested herein since his 1996 study focuses on territorial rivalries only while I compare the attributes of territorial and other type rivalries.

Return to article34. �� Vasquez, �Distinguishing Rivals,� p. 537.

Return to article35. �� Ibid.

Return to article36. �� Ibid., p. 539.

Return to article37. �� Ibid.

Return to article38. �� Ibid.

Return to article39. �� Ibid.

Return to article40. �� Ibid.

Return to article