by Timothy J. Lomperis

Prologue

At this writing, the storm clouds of military intervention build in North America over the "grave and gathering danger" in Iraq, a half-world away. In his speech to the UN on 12 September warning of this danger, President George Bush demanded that Iraq end its threat to world order by eliminating all its weapons of mass destruction. He also insisted that the government in Baghdad stop oppressing its minority populations and open itself up to democratic reforms.1

The clouds of this "gathering intervention" are a lethal admixture of two levels or arenas of politics: the imperatives of international order under girded by the foreign policies of "supervising" great powers and the disorders roiling up from societies of unstable, weak, and volatile states. Dangers lurk in this admixture. The United States, as one of these supervisory great powers, has had frequent opportunity to discover this: at the Bay of Pigs in Cuba, in the long nightmare of the Vietnam War, in a blown-up Marine barracks in Beirut in 1983, during the sharp war in the Persian Gulf in 1991, and in a "Black Hawk down" in the streets of Mogadishu, Somalia in 1993. More recently, in the break-away Serbian province of Kosovo in 1999, Washington, in its desire to staunch the internationally disordering flow of Kosovar refugees, was pulled into serving as the air force for the local Kosovo Liberation Army, whose local separatist political ambitions were at odds with the integrationist international objectives of the United States.2

As a guide to the wary, this article seeks to elucidate the political dangers emanating from the often murky levels of the domestic politics of target states to the international political intentions of those supervisory powers who contemplate pulling interventionist triggers.

INTRODUCTION

Interventions come as much from seduction as they do from rape. Anyway you look at them, military interventions to alter or forcibly preserve the domestic political arrangements or foreign policies of client or target states are violations of sovereignty. Sovereignty is the foundational presupposition of the paradigm of an international system centrally composed of mutually sovereign nation-states. Foreign military interventions, for whatever reasons, are clear violations of this principle and confront this paradigm of individually sovereign, but collectively anarchic, nation-states with anomalies serious enough to overthrow it.3 Interventions, nevertheless, have been frequent, if not quite commonplace. In order to preserve the fundamental respect for this principle's survival, interventions by great powers in the affairs of smaller ones have always been justified by exceptionalist rhetoric.

The rape-versus-seduction metaphor that I have chosen follows in this exceptionalist language. Interventions are not routine. A system based on a mutual respect for sovereignty puts any intervention in at least some posture of disrespect. Neither rapes nor seductions are accepted ways of conducting interpersonal relations. The metaphor also illustrates a tension. Interventions are variously perceived: as a rape, perhaps, by at least some elements in the target society, or as a possible ambush of seduction from the vantage point of the intervener. These two perspectives are what Richard Little calls "push" and "pull" explanations of intervention.4

The "push" explanation refers to international factors propelling interventions. That is, interventions arise from foreign policy goals of great powers that seek to either bolster or alter the internal political arrangements of target states to bring these arrangements and their foreign policies in line with the international position of the intervening powers. Here the interventions, whatever else they are doing, are forcing their will on the target states, and, at least to those elements in these societies who resist, the interventions are rapes. Though sliding from "push" to "rape" may constitute something of a rhetorical stretch, the rape metaphor has the analytical utility of underscoring the fact that any forcible intervention will carry a built-in problem of legitimacy.

The "pull" explanation points to factors within weaker states that attract outside interventions. Though these factors may seem to provide compelling reasons for outside "assistance," the core of a pull explanation rests in domestic political interests within target states that see foreign interventions as advancing their own goals at least as much as, if not more than, those of the obliging, and perhaps unsuspecting, intervening powers. These powers, then, are seduced into fulfilling the objectives of the ostensibly feeble target states.

Though not a favorite metaphor among statesmen and scholars of intervening states, most of the literature on intervention views it from the perspective of the pushy explanation of rape. That is, the concerns of interventions are examined fairly exclusively from the calculations of the interveners: the costs and benefits to them, and their own capabilities and limitations in undertaking such enterprises. What is again apt about the rape metaphor is that rapists, by definition, do not see their actions too empathetically from the perspective of their victims. The self-absorbed considerations of the rapists are so paramount that they are not willing to grant their victims even the right to a point of view, let alone recognize that the victims are capable of manipulating the interventions themselves to their own advantage. If sex is interactive and rape is not, rapists fail to appreciate that their military interventions are also interactive political deeds.

Despite Little's insistence that interventions are best understood in the tension between push and pull explanations,5 I will show that the weight of the literature on intervention lies heavily with the push perspective, and briefly demonstrate that this literature has largely and shortsightedly ignored the view of interventions from the other end: the pull explanation whereby interventions can also be seductions. My thesis is that the richer insights lie in the more subtle explanations of seduction. For policymakers, these bottom-up explanations allow interveners to elude many of the ambushes hidden by top-down deductive treatises. To be sure, interventions are not solely due to "push" or "pull" factors, but occur in an environmental mix of both. No case, then, will neatly fall into separate categories of "push" (rape) or "pull" (seduction) because interventions involve at least two parties who have two political perspectives and sets of calculations. My basic point, however, is that the politics "from the other end," the lower or domestic end of the target state, are too often under-appreciated.

Rape

In the Western world, Prince Metternich of Austria offered one of the first top-down or "push" justifications of interventions. He argued that, in fashioning a balance-of-power international system, great power "supervision" of lesser powers might be occasionally necessary to ensure that the "repose" of the system itself would not be disturbed.6 The United States later relied on a justification similar to that when it frequently intervened in weak Central American states to preclude European interventions that might disturb the repose of the Monroe Doctrine. The Cold War continued this top-down perspective under the rubric of the Containment Doctrine that sought to create a global repose of anti-communism. As Robert Packenham pointed out, the American objectives in the Third World were obsessed by these security concerns, despite rhetoric that seemed to promote economic development and political democracy.7 This, to D. Michael Shafer, set up a "deadly paradigm" of "contentless universalism."8

When the Korean War (1950-53) ended without resorting to nuclear weapons, but also far short of victory, a literature developed on "limited war." Once this literature decided that limited war did not mean tactical nuclear war short of a full strategic nuclear exchange,9 but rather military interventions employing strictly conventional means for politically circumscribed objectives, it became a literature of fairly prescient warnings. In acknowledging what Secretary of State George Shultz later called "ambiguous warfare," Robert Osgood pointed out that the very difficulty of these interventions could make them become protracted, and he worried whether the American political system had the patience for such engagements. Osgood, in brief, was not sure that "limited war" was a good idea.10

Alexander George thought that not all of it was bad, only some of it. In his Limits to Coercive Diplomacy, for example, he argued that interventions were of two types: those that prevented a deed only contemplated by an adversary (Type A), and those that had to undo something that had already been done (Type B). Naturally, Type B was much harder to do, and should be avoided, whereas Type A, since it was pre-emptive, was given a green light by George. The fact that perhaps these interventions were more complicated than this neat dichotomy suggested was ironically illustrated by George's own examples. For Type A, he approvingly cited Kennedy's dispatch of 5,000 US marines to Northeast Thailand in 1961 to successfully dissuade the Pathet Lao from overrunning Laos. He used the Cuban Missiles Crisis for Type B to stress both the dangers and difficulties of forcing a strategic reversal on an adversary.11 What is confusing about these examples is that, whatever the theoretical point, George's Type A example was an ultimate historical failure and his Type B illustration was America's most ringing Cold War triumph.

Nevertheless, the major point of this literature was still well taken. It was Alexander Mack who said it best. "Big nations lose small wars," he observed, because they can never give them their "all," since other global responsibilities keep great powers perennially distracted. Since, from the perspective of the smaller target state, this "limited war" (to the outsider) is the total arena of their national life, they will be much more focused in this engagement and more likely to marshal all their available resources. There is, then, an asymmetry of will that frequently permit the smaller and weaker power to win.12 The asymmetry of will stems from the fact that "big nations," with far-flung global interests and commitments, are playing many games at once and cannot permit one game to draw away too many of their pieces in this multi-gamed global chess board. If this happens, peer competitors to the big power are likely to take advantage of this with provocative actions in areas left uncovered by this distraction. As examples, in both the Bay of Pigs in 1961 and the Cuban missiles crisis a year later, President Kennedy felt constrained in Cuba by his fears that the Soviet Union would retaliate with horizontal escalation in Berlin.13 In sum, this literature on limited war was certainly not lacking in insights, but they were insights that lacked particularistic detail. There were some good general principles, to be sure, but the truths that came from details on the ground were lacking.

The subsequent literature on counterinsurgency should have been better. Roger Hilsman, the ex-Merrill's-Marauder-turned-New Frontiersman, introduced America to insurgency in his lengthy Foreword to an English translation of General Vo Nguyen Giap's People's War, People's Army.14 Giap's tract provided an account of his stunning triumph at Dienbienphu in 1954 in a straight Maoist people's war framework. The Kennedy administration girded itself for this new Cold War challenge of "brush fire wars" with its own new strategy of "flexible response."15 A suitable literature quickly developed that analytically broke apart insurgencies into laundry lists of stages and typologies with a set of countermeasures to match each stage and block each type.16 But all this carefully scripted balancing and counterbalancing became too straight jacketed in its formularies to bring the nuanced politics on the ground into focus. In the end, the analysis remained on a too general, deductive level.17

Seduction

While "push" factors of balance-of-power policies, limited war goals assessments, and counterinsurgency strategies and techniques do have insights to offer, none of these approaches proved fine-grained enough to bring the perils and pitfalls of local political contexts into view. A strategy of flexible response was still not supple enough to avoid a "quagmire" in Vietnam.18 Appreciating Maoist insurgency strategy was not enough to keep up with the perilously mercurial Prince Norodom Sihanouk in Cambodia. Despite his exasperating ways, he still held the keys to Cambodian political legitimacy, even as all the second-choice fallback clients, seized upon by the Americans, did not.19 Relying on the disastrous deductive assumption that since, by definition, communism was unpopular, President Kennedy was persuaded to believe that all that was necessary to ignite a massive popular uprising against Castro's Cuba in 1961 was to insert a mercenary brigade of Cuban exiles along the coast. In so doing, the "volunteers" were stopped cold in a regurgitation known as the Bay of Pigs fiasco.20 In all these cases, and many others, a greater penetration into local politics would have triggered flashes of warning.

Not only are these politics difficult to penetrate, they can also shift dramatically, and alter the terms and target of the local sirens of seduction. A particularly vivid case of these local politics as a stimulus or pull of intervention was Ethiopia in the summer of 1991. The Ethiopian regime of General Mengistu was supported by the Soviet Union. The collapse of the Soviet Union tempted the Tigray Peoples Liberation Front and the Eritrean separatist movement to move in for the kill on the capital city of Addis Ababa. As they advanced on the capital, all three groups pronounced their undying loyalty to their respective foreign benefactors: the regime to Moscow, the Eritreans to their Cuban advisers, and the Tigrayans to the inspiration of Albanian Maoism. Just at this inopportune moment, however, these three benefactors collapsed.21 Not skipping a beat, the Tigrayans, as they marched through the streets of Addis Ababa the moment that Albania's Maoism succumbed to capitalism, switched their rhetoric, mid-sentence, from the triumph of Maoist people's war to effusive admiration of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address.22 Here was the politics of seduction nakedly revealed, as Washington suddenly found itself supporting the new regime's claim for support in the interests of regional stability, a mantra always pleasing to American ears.

These two cases of the Bay of Pigs in 1961 and Ethiopia in 1991 illustrate the fact that interventions by seduction are at least of two types. Ethiopia is an example of outright seduction in which local political groups lure an outside power into an intervention for their own local purposes, purposes usually unbeknown to the hapless "victim." Similar instances are America's "humanitarian" intervention in Somalia in 1992 succumbing to other purposes in Mogadishu, and perhaps, in a global Samsonesque temple of a crash of civilizations, Osama bin Laden struck his blows on 11 September as a grand, provocative "sucker play."

The Bay of Pigs, on the other hand, is an example of seduction by pitfalls of quicksand. In this case, the intervener is tempted by the apparent weakness of the target society and the inviting opportunity it presents to this intervener of securing an easy advantage for its global purposes. The usual scenario is to witness a lightning attempt at a coup de main turn into a debacle, as in the Bay of Pigs, or deteriorate into a quagmire of protracted conflict with a tar baby, as in Vietnam.23 These blows are stimulated by the top-down perception of weakness and vulnerability. This, of course, sets up the seductive target for interveners who, once on the ground, fall into a thigh-lock grip of political complexities. Indeed, as the Joint Chiefs of Staff warned the enthusiastic civilian planners of the Bay of Pigs invasion: "Ultimate success will depend upon political factors."24

Ethiopia as Outright Seduction

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Horn of Africa lay prostrate in the deathly embrace of famine, poverty, and violence. Civil wars raged in Sudan and Somalia. Five insurgencies plagued Ethiopia and Eritrea. The region was the poorest in the world. Per capita incomes in 1987 were $130 per year in Ethiopia, $290 in Somalia, and $330 in Sudan. This latter figure represented the overall average for the slightly more developed sub-Saharan Africa.25 But it was not the poverty that concerned Washington so much as it was the huge Soviet, Cuban, and even East German presence and influence. With Soviet military support of one billion dollars per year, the Marxist government of Ethiopia had built up an army of 350,000, the largest in Africa.26 Supporting this build-up were 16,000 regular troops from Cuba and 2,000 Soviet military advisers.27 On top of all this, to the further frustration of Washington, the dominant insurgent groups also spouted Marxist-Leninist ideologies. Somewhat quixotically, the ultimately triumphant Tigrayans, who liberated Addis Ababa in 1991, professed a Maoism loyal to Albania, even though they admitted to finding little from this loyalty to apply to Ethiopia.28 In this Cold War diplomatic chessboard, then, Washington found itself practically frozen out of the strategic Horn of Africa.

Dramatic events in Europe, however, brought changes. The collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 shifted alignments worldwide. Moscow stopped its military assistance to Ethiopia at the end of 1990, and President Mengistu, in a major speech in March 1990, admitted that socialism had failed in Ethiopia. At the end of this year, Mengistu confided to an American official that he had turned to Moscow only because the United States had "betrayed it in its greatest need" (when Washington supported Somalia in the war with Ethiopia over the Ogaden region in the 1980s).29 After pouring $21 billion into Ethiopia over a 17 year period, with such gratitude from Mengistu, perhaps Moscow was played for a sucker as well.30

These changes also affected the insurgent groups. In December 1990, Albania abandoned communism and adopted a multi-party democratic political system. The regime in Addis Ababa, having lost is patron in Moscow and feeling that insurgent groups were closing in, cast a vote in the UN Security Council in support of Washington in its "Desert Storm" campaign against Saddam Hussein in 1991. The United States then convened a peace conference on Ethiopia in London in March 1991.31 At this conference, a US official laid down what was expected for American support:

Democracy: Everything we do in the Horn should encourage the adoption of democratic methods and the practice of democracy . . .. We need also to recognize that authoritarian regimes do a great deal of damage not only to their economies, but to their societies.32

President Mengistu, however, proved less adaptable than his rivals. While acknowledging the failures of his regime, he still protested that "multiparty democracy has many disadvantages."33 Washington also remained suspicious at this conference about the Albanianism of the Tigray Peoples Liberation Front. But its leader, Meles Zenawi, quickly professed his loyalty to democracy and, as mentioned, alluringly quoted liberally from Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. Mengistu fled the country on 21 May and, with America's blessing, the TPLF entered Addis Ababa on 27 May.34

Under the promises of a democracy regained, the aid spigot from Washington turned back on. During the years of the Mengistu regime (1977-91), Ethiopia was one of the lowest recipients of foreign economic aid. On a per capita basis in Africa, only fellow-Marxist Mozambique ranked lower. Immediately after the fall of the Mengistu regime, the US put together an international aid package of $672 million. This was followed by a World Bank package (with the heavy support of the United States) of $1.2 billion in November 1992. Before the Mengistu overthrow, individual US aid for Ethiopia averaged only $50 million a year, mainly for disaster relief. Two-thirds of the funds in these packages were either from the United States or from organizations largely controlled by Washington - a huge increase in American assistance.35 With this support and some reforms of privatization to the economy, some security and economic growth returned to Ethiopia. From an initial 1.7 percent growth after the 1991 revolution, the economy rose to annual growth averages of four percent in the mid-1990s to six percent by 1999.36

Unfortunately, what was not regained was democracy. Despite the promulgation of a democratic constitution that went into effect in 1995 and the holding of elections in 1992 and 1995, Ethiopia remains a "closed political system." The 1992 elections turned into an opportunity for the new regime to hunt down the rival Oromo Liberation Front. Elections in 1995 set up a national parliament with 90 percent of the representatives coming from the ruling party. Prime Minister Zenawi and his ruling circle of ethnic Tigrayans closely hold executive power. What skews even the trappings of democracy in Ethiopia is that Tigrayans comprise only 10 percent of the population, while the disenfranchised Oromos represent 40 to 50 percent.37 Nevertheless, under President Clinton, Ethiopia rose to the status of the second largest recipient of US aid in sub-Saharan Africa.38 On his final Africa tour as president in 2000, at a speech in Addis Ababa, he proclaimed Ethiopia to be a part of "the new Africa." In brief, again, President Clinton proved to be an easy mark for seduction.

The Pitfall of the Bay of Pigs

In the global struggle of the Cold War, one area that the United States was determined to keep for its own was its "backyard" in the Caribbean. Fidel Castro's overthrow of Fulgencio Batista in Cuba in a revolutionary campaign in 1958 made Washington nervous. Though he professed not to be a communist, Castro's leftist intellectual leanings were troublesome. His nationalization of the sugar plantations and of select American companies was reminiscent of the leftist Arbenz regime in Guatemala that the CIA felt compelled to overthrow in 1954. When Castro accepted Soviet military help in building up his armed forces, President Eisenhower determined Castro had to go as well, and handed over a CIA project for Castro's ouster to his "Cold Warrior" successor, John F. Kennedy.39 Any lingering doubts on Castro's loyalties were erased by a reported statement he made on 8 November 1960, just after the American presidential election, in which he declared, "I have been a Marxist from my student days...[and that] Moscow is our brain and our great leader."40

The responsibility for this operation to oust Castro, "Zapata," fell to Richard M. Bissell. Bissell was a self-confident operative in the CIA who was the architect of the U-2 surveillance program and the mastermind behind the successful CIA-led coup d'etat that overthrew the offending Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala.41 Bissell was sure he could pull off another Guatemala and keep communism out of the Western Hemisphere. The plan was to train a secret brigade of Cuban exiles operating, nominally, under a Revolutionary Democratic Front proclaimed in Miami in 1960 (under State Department sponsorship) that would land in the southern Cuban coastal town of Trinidad, stir up the population, and join guerrilla bands operating in the nearby Escambray Mountains. Political leaders of the Front would then land in Trinidad and proclaim a provisional government. The US would quickly demand a ceasefire and usher in OAS-brokered elections that would send Castro and the communists packing.42

In putting this plan together, some advisers to the president, like William Bundy, became aware "of Bissell's reluctance to look at all sides of a question," especially of the quaint notion that communist dictatorships might not be axiomatically unpopular. This gave the military pause, and in its own assessment the JCS only gave the plan "a fair chance of ultimate success." Civilians took this as a typically military conservative green light, even though by "fair," the JCS meant 30 percent (a percentage expectation the chiefs failed to share with their civilian counterparts or with the president).43 The top-down perception of Castro's weaknesses by the planners gave the plan a seductive allure. In its own subsequent internal report of the fiasco, the CIA concluded that the enterprise was a product of "wishful thinking."44

These military reservations, however, did make President Kennedy wary. Among the many failures of the Bay of Pigs, two principal ones stand out - one a "push" factor and the other a "pull" one. From a "push" perspective, Kennedy worried that the Soviet Union might take retaliatory action against the United States in Berlin, if the US connection to the operation were overt.45 Consequently, he became uniquely adamant that the operation remain covert, even if it meant abandoning the Cuban brigade on the beaches rather than providing it with overt American military support. Tragically, neither the CIA nor the JCS believed that, in the event, President Kennedy would actually withhold this support. He did. The two parties simply misread each other: "The military assumed the President would order American intervention. The President assumed they knew he would refuse to escalate the miniature war."46

The "pull" factor was the blithe assumption that the landings would trigger a popular uprising. The CIA's main evidence for this was the fact that there were some 7,000 insurgents in Cuba who were sabotaging the Castro regime with an impressive list of disruptive acts. Within Cuba, these insurgents could call on 20,000 sympathizers. Indeed, the CIA reported that 25 percent of the population would support a well-armed invading force, and that only a hard-core 5,000-8,000 members of Castro's armed forces of over 300,000 would actually fight this force. These latter two rosily optimistic figures came from recruits of the Cuban brigade.47

As late as 4 April, Bissell reassured Kennedy that there would be a popular revolt. His proof was the State Department-created Revolutionary Democratic Front itself. Bissell portrayed it as representative of the huge middle spectrum of Cuban society, but its treatment by the CIA only bankrupted this claim. The Front was cut off from all contact with the exile brigade because the members of the Front spent so much time in factional bickering that the Agency feared any contact would destroy the unity and combat effectiveness of the brigade. The exile leaders, in effect, were reduced to the status of puppets of their covert American leaders.48 In important political terms, then, this attempt at bridge leadership was delegitimated from the start.

A poignant illustration of this short shrift given to local political factors lay in the final selection of the invasion site. Trinidad was originally selected because its 18,000 inhabitants cradled a hotbed of anti-Castro sentiment and hundreds of guerrillas operated in the Escambray Mountains just outside of the town. Kennedy nevertheless overruled this site because he feared it was too public and risked revealing the American connections of the invaders to the Soviets. Instead, he picked the more deserted Bay of Pigs, 100 miles away from this enclave of support in Trinidad. From the Bay of Pigs, the path to these mountains lay over 80 miles of swamps that also crossed through a hostile rural population. Castro had made a special point of reaching out to these rural cabaneros (traditional charcoal makers). In two years, he had built a hospital, an airport, three paved highways, and dispatched 200 adult literacy teachers to these swamplands. Here invaders were not welcome.49

Not surprisingly, the three-day invasion from 17-20 April 1961 was an epic disaster. A "brigade" of 1,500 CIA-trained Cuban exiles landed in two spots in this bay to confront a local Cuban militia force of 25,000. Despite these odds, the exile forces acquitted themselves bravely on the ground.50 By the second day, however, Castro's fledgling air force had wrecked havoc with both the men on the beaches and with their supply ships. At this critical juncture, Kennedy refused an urgent CIA and JCS request to allow American air strikes to ease the pressure and permit the brigade to attempt a breakout to the mountains. General Lyman Lemnitzer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called this decision "absolutely reprehensible, almost criminal."51 With this, the invasion was over. On 20 April, the brigade surrendered. Of the 1,518 men in the brigade, 114 were killed and 1,189 made prisoners. Only two dozen escaped to US Navy ships.52

For Fidel Castro, the invasion was a gift. Even as he publicly admitted to his communism on 16 April, the three-day invasion that followed cemented a domestic legitimacy to his regime that lasted for the rest of the Cold War. Indeed, Che Guevara told a Kennedy aide in August 1961 that it was "a great political victory" that enabled them to "consolidate their rule" and transform themselves "from an aggrieved little country into an equal."53 In brief, Washington was tempted into an act of folly. To his speechwriter afterwards, Kennedy provided his own postmortem: "All my life I've known better than to depend on the experts. How could I have been so stupid to let them go ahead."54

Intervention "From the Other End": The Primacy of Legitimacy

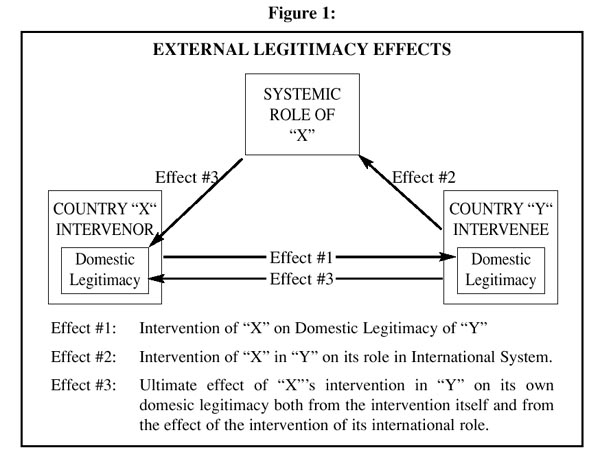

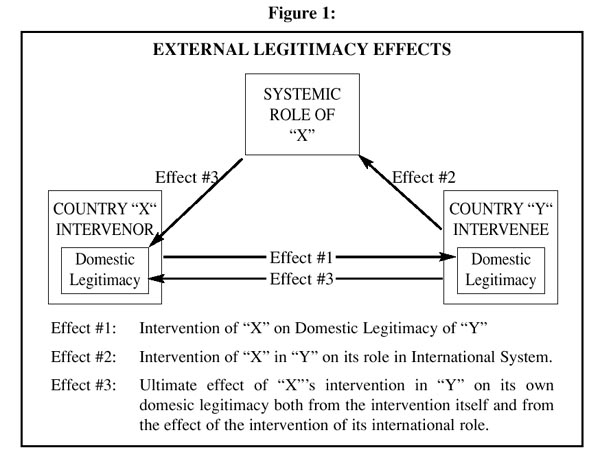

In developing a set of refined insights from this view of intervention as pulled by seduction, a good starting place is James Rosenau's Linkage Politics. Professor Rosenau has long been a careful student of intervention.55 His basic point about linkage politics is that international politics and domestic politics are inextricably interconnected. A military intervention provokes what he terms a "step linkage," which has the effect of changing the nature of the rules of politics in both the intervening and the "host" state.56

These interactive linkages can be spelled out in Figure 1 above, External Legitimacy Effects.57 In it, an intervention initially will affect the political legitimacy of the client regime. This effect, in turn, will reverse back on the intervening state through both its effect on the intervener's systemic role in the international system and, ultimately, on the intervener's own domestic political legitimacy. Particularly in an insurgency, where an intervention can become protracted, the politics of the two societies become intertwined.58 A vivid illustration of this "union" was the heavy American involvement in the assassination of South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem on 1 November 1963, and the tremendous impact of the unraveling chaos in Saigon upon the difficult transition of power to Vice President Lyndon Johnson, when President Kennedy was gunned down in Dallas just three weeks later.

This figure reflects a presupposition that legitimacy is the central issue of the struggle between the two sides. Insurgencies, in brief, are not just struggles for power; they are struggles for both the purpose of power and the right to power. "Purpose" and "right" are conceptions of politics built on the set of principles employed in a particular society to justify or legitimate power. While legitimacy is a general surplus margin of respect desired by all ruling regimes, its actual principles are unique or particular to each country. The point of this focus on legitimacy for an intervener is that an intervener will have to assess these principles carefully because they will have a strong effect on the political prospects of the intervention itself. From the perspective of a target state's politics, a foreign intervention can carry a positive, popular charge - or a negative, highly resistant charge.

Simply put, this very general deductive concept of legitimacy can have highly varied political meanings as it is inductively discovered on the ground country-by-country. Hence, in countries like Vietnam and China, whose principles of legitimacy collect around a Mandate of Heaven and a requirement to keep the land free of foreign devils, ground interventions by foreign troops were likely to harm the legitimacy of the incumbent regime and only hand the insurgents a patriotic rallying cry. Yet, in countries like Greece and Malaya, principles of legitimacy worked strongly in favor of Western interventions: in Greece because this global attention was flattering to the Greek sense of national importance in its megali idea (a harkening back to the grandeur of Byzantium and the classical Greece that was the cradle of Western civilization), and in Malaya because the tense inter-communal relations among Malays, Chinese, and Indians depended on the honest broker role of the British.59 Such a single-minded focus on legitimacy as the ground for explaining insurgencies, and interventions in them, has not been without its critics,60 but it does have the advantage of calling attention to "pull" explanations rooted in bottom-up political contexts that can expose the perils of seduction.

The "Perfect Storm" of Seduction in Vietnam

In this discussion of rape, seduction, and legitimacy, Vietnam cannot pass unnoticed. It presents, literally, a "perfect storm" of military intervention. Bundled into this tragedy are all the "push" and "pull" factors of intervention. With everything in it, it is always summoned for lessons. More than this, since it was a searing American failure, it is the ghost that still haunts the American psyche whenever it steps up to the plate to face Hamlet's question for every great power: to intervene or not to intervene?

Global strategies of containment and flexible response stumbled the Americans into Vietnam. China needed to be contained to preserve Southeast Asian markets and resources for Japan, and Washington needed a laboratory to brush up on its unconventional war capabilities to demonstrate a full range of "flexible response" options. As far away as it was in stretching American military resources, at first it looked like a tempting cake walk: a seduction of weakness. After his first trip to South Vietnam in November 1961, Kennedy's special military adviser, General Maxwell Taylor, offered this reassurance:

As far as an area for the operation of U.S. troops, South Vietnam is not an excessively difficult or unpleasant place to operate . . .. The risks of backing into a major war by way of South Vietnam . . . are not impressive.61

Even when US ground combat troops were fully deployed, the US commander proclaimed a three-phased strategy to bring "victory in three years."62 Instead, the end of the three years brought the country-wide ambush of the communist Tet Offensive of 1968, and all hopes of bringing the boys "home by Christmas," at least on American terms, receded. As the war bogged down, the corrosion of the corrupt and authoritarian politics of the Saigon regime ate its way back to the very politicized streets of America. The triangle of Figure 1 came full "circle" in Vietnam with the question of legitimacy pulling everyone down.

As the next section illustrates, once tempted into Vietnam as a felicitous laboratory for counterinsurgency, the Americans fell into several traps of outright seduction. The unwary this time, however, were Washington's own "best and brightest," not foreign exiles who could be abandoned at the beachheads. The requirements of overt commitment and global prestige demanded that these "soldiers of democracy" keep pummeling the tar baby.

Insights "from the Other End"

As the United States continues to contemplate foreign military interventions in a post-Cold War international system, four insights from the pull perspective of seduction can serve as warnings: the illegitimacy lock, the trap of "après mois, la deluge," the sucker play, and the requisite of bridge leadership.

The illegitimacy lock is a negative and mutually reinforcing linkage between an intervening power and its client regime. Once an intervening power has made a policy commitment of intervention in a client state, this client state will then have made its own domestic politics part of those of the intervening power. Thus, to maintain its policy position, the intervening power has to bolster the domestic position of this client regime. If the domestic legitimacy of this regime is dubious or contested, there is a strong temptation for the client regime to rely on the intervener for resources it should properly develop locally. This is because the very development of these resources internally will require the regime to reach out and broaden its political base in ways that dilute its own domestic power position. In order to preserve its narrower position, the regime naturally prefers to let the helpful, but hapless, intervener provide these resources instead. If the intervener balks, the client regime will try to convince the intervener that it must support the regime because the alternative is chaos, which will then destroy the policy of the intervener the intervention is serving. If the intervener accepts this destiny, or helplessness, the latch on the lock has shut - and the tail now wags the dog. It also means that the domestic illegitimacy of the regime has become contagious, infecting the legitimacy of the intervention itself.63

The example of South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu (1965-75) provides a good illustration. Thieu came to power through a military coup d'état, giving him a narrow, but still exclusive, claim to rule. The Viet Cong insurgency was building its political movement on appeals to land reform and a broader participatory base to national politics. In order to undercut this movement politically, Thieu needed to promote his own land reform and a more democratic political system. However, since his own putschist path to power lacked the legitimacy of these more "constitutional" methods, any meaningful set of reforms, at the very least, would force him to share his power with this broadened political base to national politics. Thieu's own narrow political interests were better served by avoiding all this and letting the Americans step in and prosecute the counterinsurgency more vigorously. Unfortunately, this only compounded Thieu's legitimacy problem, just as it made the Americans an integral part of his illegitimacy. At this point, the lock was complete. With the lock in place, Thieu could count on the Americans to bail him out. When the Tet Offensive broke out in January 1968, for example, Thieu at first panicked because he thought it was a coup attempt by one of his military rivals. When he realized that it was just a massive, all-out communist bid for power, he was immensely relieved. Not to worry, the Americans would take care of the communists. A coup he would have had to deal with on his own.64

A pernicious variant or supplement to the illegitimacy lock is the phenomenon of "après mois, la deluge." After an illegitimacy lock has become protracted, it becomes addictive. That is, the client regime may come to fully realize that ultimately the only way out of this impasse of illegitimacy is to seriously undertake the reforms that would staunch the flow of leaking legitimacy. The problem, of course, lies in the fact that these reforms may well rip out the props of the regime's power. Hence, the client will constantly step back from taking the plunge of reform and revert to the opium of the intervener's money, infrastructure support, and army. Thus:

Put from the perspective of the ruling clique: to win an insurgency is to lose because it will result in a call for broad-based civilian rule. More pragmatic victory lies in losing imperceptibly and staving off the ultimate reckoning with a circumspect, respectful intervention. Obviously, it is a program for survival built on a fraud because when the foreign help is withdrawn, the deck of cards collapses.65

Such a saga of "après mois, la deluge" was the long dependence of China's Chiang Kaishek on the Americans. In fact, Chiang lacked the decency to die when he lost to Mao Zedong's guerrillas in 1949, but managed to entice the Americans into continuing his habit of dependence when he set up his second client regime on Taiwan.

The most vicious of all seductions, however, is the sucker play. This occurs when one of the political forces on the ground in the client state entices a great power into an intervention in order to exploit this intervention for its own partisan advantage, an advantage that can turn treacherously against the interests of the intervening great power. Although risky for the local force, such a ploy can offer dramatic pay-offs. When a schoolboy begins to bear a losing image on the playground, what better way to regain his position than to challenge the bully to a fight? Though the inevitable bloody nose will smart, the reestablished respect will provide an exhilarating salve.

Such a salve came to Mohammed Farrah Aideed in Somalia, who was a leader of one of 12 feuding warlord clans fighting among themselves to succeed Mohammed Siad Barre following his ouster from power in 1989-90. Despite his military strength, politically, by 1992, Aideed began to find himself in a losing position in national politics, even though he had carved out a zone of control in the southern part of the capital city of Mogadishu. In the anarchy and ensuing mass starvation of that year, Aideed reluctantly consented to a US-led intervention. Nevertheless, the immediate effect of the intervention was to keep everyone in place, fortuitously preserving Aideed's position in Mogadishu.66

When the US succumbed to "mission creep," and moved against the "warlords," Aideed turned on US forces. In a bold "sucker play," he made himself something of a national hero against the "world's remaining superpower" when his forces ambushed elite US army rangers in a battle on 3 October 1993 that left 18 American soldiers dead in the streets of Mogadishu. The Clinton administration's announcement of a US withdrawal by March of the next year only confirmed the success of Aideed's gamble.67

The way that Osama bin Laden's blows on 11 September can be seen as a sucker play is to understand that the United States is not his primary target, but a means to an end. Like all radical Muslims, in all his pronouncements the objective of bin Laden and of his organization is to take up "the neglected duty" of the restoration of the Muslim Empire. The barrier to his dream is not so much the United States as it is the moderate regimes of the major power centers of Islam: Egypt, his native Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Algeria, Morocco, Pakistan, and Indonesia. The problem to him is that the destinies of these regimes are too closely linked with the West. The purpose of this dramatic attack on the United States, then, is to provoke such massive retaliation by the Americans that the faithful in the "Arab streets" will be so enraged that they will not only fight against the United States but overthrow their moderate rulers as well. In this light, an American invasion of Iraq might prove to be just the incendiary trigger for the fulfillment of the fondest dreams of Osama bin Laden.68

Finally, one of the most important insights emanating from a bottom-up context is the necessity for an intervention to either find, or desperately build, bridge leadership. If a client regime is to have any prayer of standing on its own and building an independent claim to national legitimacy, it must have a leadership capable of building bridges to the middle center of national politics. Typically, insurgencies arise out of a dumbbell model or image of a right-wing incumbent regime facing off against a left-wing insurgent group. With both parties starting from a political periphery, victory, at least in political terms, lies with whoever captures the middle bar of the dumbbell.69

The hazards of ignoring the prerequisite of bridge leadership, or at least possibilities of it, are demonstrated by the dilemma posed by South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem in 1963 and Saddam Hussein today. However autocratic Diem's regime had become by the fall of that year, Diem did retain foundations in the middle ground of civilian politics. By supporting his ouster, the United States very nearly destroyed its own intervention as the subsequent military regimes lost all claim to this middle ground. The war against the communists continued thereafter almost exclusively on American shoulders. This put the fate of the Vietnamese too much in the hands of domestic American politics, and this support failed to go the distance. In President Clinton explicitly calling for the ouster of Saddam Hussein as part of his "Christmas bombing" of Iraq in 1998 (which he called OPERATION DESERT FOX), it is doubtful that much attention was paid to identifying any alternative bridge leadership in Iraq. Similarly, in all of President George W. Bush's further and recent calls for "regime change" in Iraq, there has been no mention of the political forces in Iraq who would shoulder this burden.

"Insightful" Questions to Ponder

All interventions will certainly have to undergo initial discussions over the policy merits of their anticipated benefits to the foreign policy goals of intervening powers. Hence, "push" calculations of interventions do have à priori validity. As this article has tried to show, however, such calculations are not enough to avoid the pitfalls of seduction that may await intervening powers. Hopefully, I have made it clear that insights from the "pull" level of local contexts are portentous enough to create disasters of Syracuse for the unwary.

From the insights of seduction in this article, policy makers would do well to factor into their deliberations the following set of questions:

First, regarding the illegitimacy lock, and how to avoid it, what are the strengths of the legitimacy claims of the competing factions in the target state, and especially of the faction contemplated as the client?

Second, as for the trap of "après mois, la deluge," what are the narrow self-interests of the prospective client, and how can the larger national interests be kept paramount in the intervention?

Third, on the dangers of a sucker play, once on the ground with forces of intervention, which parties, even friendly ones, would stand to make political profit from dealing these forces an unsuspecting blow?

Finally, concerning the critical legitimating factor of bridge leadership, where in the target state's political spectrum does a proposed client's support lie? If it is a distance from the center, what are the opportunities for, and obstacles to, moving the client to this center?

While most interventions are driven by "push" factors, I submit that their success cannot be assured unless positive answers can be developed to these four questions drawn from the "pull" factors of seduction. I have seen no evidence of such positive answers for any campaign to overthrow Saddam Hussein in Iraq. As the 78-day NATO air campaign over Kosovo demonstrated: while new technologies may make interventions easy in the getting in, with the razzle-dazzle of "virtual war" from the air, once on the ground, the local politics can mire these intervening forces in wars of politics without end. What won't end are the political questions of the illegitimacy locks, the parochial self-interests of local leaders, the dangers of their sucker plays, and the often futile quest for the elusive chimera of bridge leadership. It is these questions emanating "from the other end" of intervention - the "pull" end - that need to be considered before the "push" side of high-minded global policy gains too much momentum to see these perils of seduction.70

EPILOGUE

In this momentum in the United States to oust Saddam Hussein, the Bush administration is laboring hard to prepare the groundwork for an intervention - at the United Nations, among both NATO allies and friendly states in the Middle East, in the corridors of the US Congress, and on the TV talk shows to raise the paeans of war to the chattering class. While the American opinion poll numbers rise in support of this war, there remains one detail, as the Wall Street Journal has acknowledged, "But how Iraq's population would react to a U.S. invasion remains a wild card."71 It was this same wild card at the Bay of Pigs that forced a profession of stupidity from President Kennedy. We need no further such professions over Baghdad.

There are, of course, instances in which "push" factors of international threats and looming de-stabilizations of balances of power compel interventions by great powers. Such was the case in Cuba, a year after the Bay of Pigs, when the Soviet Union was caught installing nuclear missiles on this island nation capable of reaching the eastern United States in five minutes. Analogously, the question that this article commends to all Americans, and to their allies, as a final check for an intervention is: with respect to Iraq in 2002, which Cuba is the right analogy - the "pull" of pigs in 1961 or the "push" of missiles in 1962?

Endnotes

1. "Excerpts from President Bush's speech at the United Nations," Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, 13 September 2002, p. A9.

Return to Article

2. Among those who referred to NATO's aerial armada as an air force for the KLA was American Lieutenant General Robert Gard. See

Elizabeth Farnsworth, "The Art of War," Online News Hour, 16 June 1999 (McNeil/Lehrer Productions, 2002:

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/Europe/jan-june99/lessons_6-16.html) .

Return to Article

3. For the seminal works on international anarchy and the construction of the paradigm, see Hedley Bull, The Anarchical society: A Study

of Order in World Politics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1977); and Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd

ed. (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1970).

Return to Article

4. Cited in Ariel E. Levite, Bruce W. Jentleson, and Larry Berman, eds., Foreign Military Intervention: The Dynamics of Protracted

Conflict (New York: Columbia Press, 1992), p. 321.

Return to Article

5. Ibid.

Return to Article

6. Paul Schroeder, Metternich's Diplomacy at Its Zenith, 1820-1823 (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1969), p. 126.

Return to Article

7. Robert A. Packenham, Liberal America and the Third World; Political Development Ideas in Foreign Aid and Social Science (Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973).

Return to Article

8. D. Michael Shafer, Deadly Paradigms: The Failure of U.S. Counterinsurgency Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988),

pp. 280-81.

Return to Article

9. Morton H. Halperin, "Limited War: An Essay on the Development on the Theory and an Annotated Bibliography," Occasional Papers

in International Affairs no. 3 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Center for International Affairs, 1962).

Return to Article

10. Robert E. Osgood, Limited War: The Challenge to American Strategy (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1957). He repeated

his warning in 1979, after the Vietnam debacle. See his Limited War Revisited (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1979).

Return to Article

11. Alexander L. George, David K. Hall, and William E. Simons, The Limits of Coercive Diplomacy (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1971),

p. 24.

Return to Article

12. Alexander J. Mack, "Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars: The Politics of Asymmetric Conflict," World Politics 27, no. 2 (January 1975),

pp. 175-200. Eliot Cohen, for one, lamented this Western faint-heartedness because he argued that these peripheral wars were nevertheless

important to America's overall power position. See Eliot A. Cohen, "Constraints on America's conduct of Small Wars," International Security

9, no. 2 (Fall 1984), pp. 151-81.

Return to Article

13. Lawrence Freedman, Kennedy's Wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 143.

Return to Article

14. Roger Hilsman, Forward to Vo Nguyen Giap, People's War, People's Army (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1962) pp. iv-xxiv.

Return to Article

15. Roger Hilsman, "Two American Counter-strategies to Guerrilla Warfare: The Case of Vietnam," in Tang Tsou, ed., Crisis in China, vol.

2, China's Policies in Asia and America's Alternatives (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1968), pp. 269-70.

Return to Article

16. This literature became voluminous in the 1960s and 1970s. Representative works are those by David Galula, Counterinsurgency

Warfare: Theory and Practice (New York: Praeger, 1964), pp. 96-135; and Bard E. O'Neill, et al., eds., Insurgency in the Modern World

(Boulder, CO: Westview, 1980), Ch. 1.

Return to Article

17. One noteworthy exception that stressed the importance of the final political measures to a counterinsurgency strategy was a book by a

World War II German general writing of his experiences in Yugoslavia. See Otto Heilbrun, Partisan Warfare (London: George Allen and

Unwin, 1962).

Return to Article

18. A simple image, it suggested a cook who had laid out his ingredients, but had no idea how to mix them together. See David Halberstam,

The Making of a Quagmire: America and Vietnam During the Kennedy Era, rev. ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988).

Return to Article

19. For an analysis of all these aspirants, in terms of their local legitimacy claims, see Timothy J. Lomperis, From People's War to People's

Rule: Insurgency, Intervention, and the Lessons of Vietnam (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), Chap. 10.

Return to Article

20. An excellent account is that of Lucien S. Vandenbroucke, "Anatomy of a Failure: The Decision to Land at the Bay of Pigs," Political

Science Quarterly 99, no. 3 (Fall 1984): 474- 90.

Return to Article

21. While Cuba itself did not collapse politically, in a ripple effect, Havana had to terminate its commitments to the Eritreans when Moscow

ended its foreign assistance to both Ethiopia and Cuba as part of its global retrenchments at the end of 1990.

Return to Article

22. Lomperis, From People's War to People's Rule, p. 15.

Return to Article

23. On the point of the coup de main, see Lucian S. Vandenbroucke, Perilous Options: Special Operations as an Instrument of U.S. Foreign

Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 3. His book examines this alluring danger in what he regards as the failures of the Bay

of Pigs, the successful raid on the empty prison in Son Tay, North Vietnam in 1971, the 1975 commando strikes on Koh Tang Island,

Cambodia to free American prisoners who had already been released, and the debacle at Desert One in Iran in 1980.

Return to Article

24. Ibid., p. 24.

Return to Article

25. Christopher Clapham, "The political economy of conflict in the Horn of Africa," Survival 32, no. 5 (September/October 1990), pp.

403-05.

Return to Article

26. James Cheek, "Ethiopia: A Successful Insurgency," in Edwin C. Corr and Stephen Sloan, eds., Low-Intensity Conflict: Old Threats in

a New World (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1992), p. 130. This Soviet support naturally resulted in a cut-off from further American assistance,

which was mainly economic. What perpetuated poverty in Ethiopia was the fact that in this subsequent Russian support, the Soviets "were

miserly in their economic assistance." See ibid., pp. 140, 142.

Return to Article

27. Stephen Chan, "Two African states (Angola and Ethiopia) and the motifs of revolution," in Stephen Chan and Andrew J. Williams, eds.,

Renegade States: The evolution of revolutionary foreign policy (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1994), p. 174.

Return to Article

28. Cheek, "Ethiopia," p. 135.

Return to Article

29. Paul B. Henze, "Ethiopia in 1990 - The Revolution Unravelling" (Santa Monica, CA.: Rand document P-7707, March, 1991), pp. 44,

51, and 54 (quote on p. 44).

Return to Article

30. Kinfe Abraham, Ethiopia: From Bullets to the Ballot Box (Lawrenceville, NJ: The Red Sea Press, 1994), p. 18.

Return to Article

31. Henze, "Ethiopia in 1990," pp. 50-51, 55.

Return to Article

32. Abraham, Ethiopia, pp. 16-17.

Return to Article

33. Henze, "Ethiopia in 1990," p. 44.

Return to Article

34. U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Looking Back and Reaching Forward: Prospects for Democracy in Ethiopia, hearing before

the Subcommittee on Africa, Committee on Foreign Affairs, 17 September 1992, p. 35.

Return to Article

35. Abraham, Ethiopia, pp. 44, 47, 251, and 257-58.

Return to Article

36. Thomas S. Szayna, Identifying Potential Ethnic Conflict: Application of a Process Model (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp., 2000), p.

218.

Return to Article

37. Ibid., pp. 195-201, 236; and personal interview with Professor Emmanuel Uwalaka, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis, MO, 18

September 2002.

Return to Article

38. Jeffrey A. LeFebre, "Ethiopia," Encyclopedia of U.S. Foreign Relations, vol. 2 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 110.

Return to Article

39. Vandenbroucke, Perilous Options, pp. 11-12; and Aleksander Fursenko and Timothy Naftali, "One Hell of a Gamble": Khruschev,

Castro, and Kennedy, 1958-1964 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1997), pp. 55, 58, 61, and 78.

Return to Article

40. Fursenko and Naftali, "One Hell of a Gamble," p. 71. Castro made these remarks to an early morning reception of the Cuban communist

party. These remarks were reported to American intelligence sources. He made this profession public to all Cubans on 16 April 1961, the

day before the Bay of Pigs landings. See Ibid., p. 99.

Return to Article

41. Vandenbroucke, Perilous Options, pp. 12-14.

Return to Article

42. Peter Kornbluh, ed., Bay of Pigs Declassified: The Secret CIA Report and the Invasion of Cuba (New York: The New Press, 1998), pp.

113-17. Ironically, this plan was more of a copy cat of Fidel Castro's own rise to power than it was of the Arbenz coup in Guatemala. Castro

and his followers made a secret landing in Cuba from Mexico in 1956, escaped into the mountains, and mounted a two-year guerrilla campaign

culminating in a march on Havana. The chief ideologue in Castro's entourage, Che Guevara, proclaimed this to be a new "focalist strategy"

of insurgency, a strategy he followed to his death in Bolivia. See Regis Debray, Revolution in the Revolution? Armed Struggle and Political

Struggle in Latin America, trans. Bobbye Ortiz (New York: Grove, 1967), pp. 19-21.

Return to Article

43. Freedman, Kennedy's Wars, pp. 127, 132.

Return to Article

44. Peter Wyden, Bay of Pigs: The Untold Story (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979), p. 327; and Vandenbroucke, Perilous Options, pp.

164-66.

Return to Article

45. Freedman, Kennedy's Wars, p. 143.

Return to Article

46. Ibid., p. 145.

Return to Article

47. Ibid., p. 137; and Kornbluh, Bay of Pigs Declassified, pp. 131, 172-73.

Return to Article

48. Kornbluh, Bay of Pigs Declassified, pp. 66-67, 99, and 296.

Return to Article

49. Wyden, Bay of Pigs, pp. 102-07, 309.

Return to Article

50. Planes from the CIA's six-plane clandestine air force killed 1,800 Cuban militia on the ground; and, at the "battle of the rotunda," an

exile force of 370 men stopped a Cuban attack of 2,000 men, killing 500 of the attackers. See Kornbluh, Bay of Pigs Declassified, p. 2; and

Wyden, Bay of Pigs, pp. 272-73.

Return to Article

51. Vandenbroucke, Perilous Options, p. 167.

Return to Article

52. Four American pilots were also killed. See Kornbluh, Bay of Pigs Declassified, pp. 2, 38- 40.

Return to Article

53. Ibid., p. 3.

Return to Article

54. Wyden, Bay of Pigs, p. 310.

Return to Article

55. One of the seminal Cold War works on intervention is his International Aspects of Civil Strife (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press,

1964).

Return to Article

56. James N. Rosenau, ed., Linkage Politics: Essays on the Convergence of National and International Systems (New York: Free Press,

1969), pp. 1-17, 44-63. In his subsequent works, Rosenau notes how this inter-relatedness of domestic and international politics has flooded

the international arena with "cascading interdependencies" producing a new world politics of "fragmegration." See his "Fragmegrative

Challenges to National Strategy," in Terry L. Heyns, ed., Understanding U.S. Strategy: A Reader (Washington, DC: National Defense

University Press, 1983), pp. 65-83.

Return to Article

57. This chart was first published in Timothy J. Lomperis, "Vietnam's Offspring: The Lesson of Legitimacy," Conflict Quarterly 6, no. 1

(Winter 1986), pp. 18-34.

Return to Article

58. Lomperis, From People's War to People's Rule, p. 72.

Return to Article

59. This discussion of legitimacy is more thoroughly presented in ibid., pp. 30-82.

Return to Article

60. In an otherwise favorable review, Herbert Tillema writes that not everyone will be persuaded by legitimacy as the right focus to a theory

on revolution, a focus he describes as psychological. See Herbert Tillema review of Timothy J. Lomperis, From People's War to People's

Rule, in American Political Science Review 91, no. 3 (September 1997), pp. 783-84.

Return to Article

61. Neil Sheehan, comp., The Pentagon Papers as published by The New York Times (New York: Bantam Books, 1971), pp. 142-43.

Return to Article

62. Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History, rev. ed. (New York: Penguin Books, 1991), p. 284.

Return to Article

63. Lomperis, From People's War to People's Rule, p. 73.

Return to Article

64. Allan E. Goodman, Politics in War: The Bases of Political Community in South Vietnam (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,

1973), pp. 92-98; and Don Oberdorfer, Tet! (New York: Doubleday, 1971), p. 330.

Return to Article

65. Lomperis, From People's War to People's Rule, pp. 124-25.

Return to Article

66. Norah Bensahel, "Humanitarian Relief and Nation Building in Somalia," paper presented at The American Political Science Association

meetings, Washington, DC, 31 August-3 September 2000, p. 18; and Chester A. Crocker, "The Lessons of Somalia," Foreign Affairs 74, no.

3 (May/June 1995), pp. 708.

Return to Article

67. Kenneth Allard, Somalia Operations: Lessons Learned (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1995), p. 31. Another

cogent account of the Somalia intervention can be found in Christopher M. Gacek, The Logic of Force: The Dilemma of Limited War in

American Foreign Policy (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), pp. 314-29.

Return to Article

68. On the primacy of this "neglected duty" for bin Laden and other radical Muslims, see Michael G. Knapp, "Distortion of Islam by Muslim

Extremists," Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin 28, no. 3 (July-September 2002), pp. 37-43.

Return to Article

69. Ralph K. White, "Attitudes of the South Vietnamese," Papers of the Peace Research Society 10 (June 1968), pp. 46-57.

Return to Article

70. For the military ease of the technologically sweet intervention in Kosovo, see Michael Ignatieff, Virtual War: Kosovo and Beyond (New

York: Henry Holt, 2000). For the political complexities, see Barry R. Posen, "The War for Kosovo," International Security 24, no. 4 (Spring

2000), pp. 39-84.

Return to Article

71. "What's News--," The Wall Street Journal, 19 September 2002, p. A1.

Return to Article