Figure 1

The Cat's Paw and the "Chestnuts"

Edwin Marcus, New York Times

by Catherine Forslund

Arguments about the overall value of editorial cartoons for historical study must wait for another venue, another historian. For now, the assumption is that these images provide historians with useful glimpses into the mind of society and culture sophisticated enough to accept criticism in the form of artistic satire. Such editorial artwork portrays personalities, issues, and ideologies, commenting on the events of the day in a most accessible way. An indication of this universality is the story of New York's "Boss" William Tweed and his response to a Thomas Nast cartoon depicting him and his minions in a circle each pointing to the other, over the caption, "WHO STOLE THE PEOPLE'S MONEY? - DO TELL, 'TWAS HIM." "Stop them damned pictures," Tweed supposedly demanded of his underlings. "I don't care so much what the papers say about me. My constituents can't read. But, damn it, they can see pictures!"1 While Tweed's assessment of editorial cartoons attributes great power of persuasion to them, in the case of the Korean War, the cartoons reflected national moods and attitudes, rather than shaped opinion among a twentieth-century public more literate than the late-nineteenth-century audience for which Nast drew. Yet, Tweed's vivid articulation of editorial cartooning's strength solidifies their historical value for gauging the internal sentiments and the shifting moods of a nation.

Editorial cartoons from US newspapers during the Korean War provide blunt illustration of the complex nature of the times playing daily to the American public. Even in that early age of television, most people still received most of their news from the printed media. The cartoons also tell, in powerful graphic form, the story of the war's changing dynamics as they affected the United States. Thus, these editorial illustrations from across the nation explore issues within the context of the war era in addition to the attitude of the United States toward that war. Each week the New York Times collected cartoons from all over the country and peppered its own editorial pages with the work of many artists (in addition to theirs), making the paper a useful source for gauging the emotion, politics, and sensibility of the United States during wartime.2 Thus, using a common language of imagery, editorial artists spelled out in the simplest term the issues of the war era.

When North Korean forces moved across the 38th parallel on 25 June 1950, the New York Times ran a small story on page one with a lead that began as follows: "The Russian-sponsored North Korean Communists invaded the American-supported Republic of South Korea today ...." This opening illustrated how, from the very first action of the war, perceptions of each side were already in place: "Russian-sponsored" versus "American-supported." Acceptance of the view that the Soviet Union directed the North Koreans (who remained almost invisible to the public as decision makers, particularly in editorial images) held sway throughout the war as shown by editorial cartoonists.

In addition, the 25 June article challenged the United States and its allies to stand up to the North Korean attack or be faced with the same problem Europe encountered when it did not respond to the 1936 German attack on the Rhineland. This was another common editorial theme - that of the necessity of containing any move by Communism to expand into other countries. According to policy makers of the time, aggression had to be met head-on, or the "Free World" would face the same fate Europe had at the hands of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. This need and the democratic nations' united stand against Communism infused much of the editorial art of the war period - reflecting the depth to which the containment doctrine had already permeated US society in the short time since the end of World War II.

The effects of an emerging and lingering Korean War effort on American civilian life was another theme of cartoonists. The economic impact of another war worried Americans who remembered the national strains caused by the Great Depression and previous wars. Editorial imagery also eventually reflected the public's war weariness. These secondary themes moved to the fore as the war dragged on, shifting the focus of editorial pages and art to issues other than Korea.

The lengthy peace negotiations provided cartoonists with months of material. They depicted the frustrations and problems of simultaneously managing peace talks and an active war effort. As negotiations came to a climax, problems with South Korean President Syngman Rhee provided colorful grist for the mills of editorial artists, and his power to control the outcome of the armistice negotiations received much ink. As peace talks languished over two years, the nation and its cartoonists turned their attention to other matters and the war moved further from the headlines.

The very nature of editorial art requires a common iconographic vocabulary easily identifiable to the audience. Without common symbols, the language of the cartoonist is undecipherable and thus powerless to convey their desired message. The Korean War and Cold War eras provided ample imagery for such a vocabulary. People - whether national leaders, the lowly GI, or the common citizen; nations - allies and opponents; and ideologies - especially Communism - were all represented by highly recognizable symbols and mixed with images of everyday life to illustrate national emotions.

Leaders were represented in cartoons due to their strong identification with national goals and characters, but they were certainly not alone as subjects. Not surprisingly, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin was the most frequent character represented in war era cartoons. That the allies considered him to be the sole controlling force behind the war is proven by his repeated appearances. Equally expected, the quintessential icon of the United States, Uncle Sam, is depicted in various modes from champion of democratic rights to beleaguered victim depending on the ebb and flow of the war. The infantry soldier and John Q. Public were also symbols of the era's complex nature. All editorial characters brought an important human element to a war which often seemed to be out of control.

The major player nations of the war - the United States, Soviet Union, and China - showed up in various guises. Whether as animals, flags, or other symbols, they were clearly identifiable to the reading public accompanied by their usual political and ideological baggage. The national anthropomorphism Korean War cartoonists used included many familiar images: the Russian Bear and hammer and sickle; Uncle Sam; stylized Chinese dress; and the hardware of war. Artists portrayed the Soviets in control of the invasion and China showed up in some later representations of the enemy, but there were virtually no depictions of the North Koreans beyond a few of them as literal puppets. Likewise, South Koreans were virtually absent from the cartoonists' lexicon. This illustrates the process of simplification that is often the effect of reducing complicated issues to visual statements.

During this period, the New York Times sometimes reproduced several images together in a single section with a heading along the lines of "How Cartoonists View the War" from a variety of papers, national and/or international. These collections were, in themselves, an editorial of sorts expressing ranging views of the day. Such groupings readily show the common imagery that was universal to the era and representative of the most powerful ideas and beliefs. Similar images were used throughout the nation, in cities large and small, were universally understood, and conveyed the mood of Americans about events half a world away.

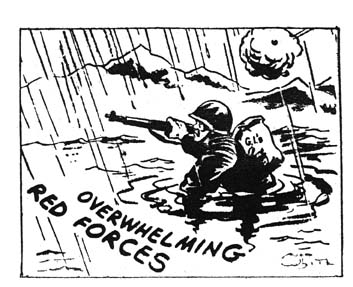

Since editorial cartoons only appeared in the New York Times on Sundays, the first images about the Korean situation appeared a full week after the conflict began. In the 2 July 1950 edition of the Times, their own cartoonist Edwin Marcus led the field with his cartoon illustrating the general view of the public as to what was happening in South Korea. In his image in Figure 1, "The Cat's Paw and the 'Chestnuts,'" the Soviet Union, identified by its familiar symbol the hammer and sickle, was depicted as an animal whose paw is Korea reaching toward Japan, Formosa (Taiwan), and the Philippines, which Western allies deemed particularly valuable at that time as democratic bulwarks against potential Communist aggression.3 These "free" Asian nations frequently were depicted by cartoonists as targets of the Communists. Another cartoon from that first weekend after war broke out showed Stalin striding in front of a fireplace. On the wall above the mantle hung empty trophy plaques labeled Philippines, Indochina, Iran, West Germany, and Korea. Stalin paced worriedly across the carpet, a paper reading "U.S. Takes Strong Stance in Asia" in hands clenched behind his back - all above the caption "Trouble in the trophy room."4 This image reflected the prevailing attitude that this was the first step in a larger Soviet scheme of conquest that included Europe and the Middle East, as well as Asia. The Soviets generally were considered to be the power behind North Korean actions, and thus illustrated as such.

Figure 1

The Cat's Paw and the "Chestnuts"

Edwin Marcus, New York Times

The notion that international Communist leaders were not behind the invasion of South Korea was lampooned in a cartoon from the London Daily Herald also reproduced on 2 July 1950. Tanks crashing through a barbed wire fence and headed toward a village formed the backdrop for a group of back-slapping uniformed men. Chinese leader Mao Zedong held a paper behind his back that said "Next step to shove America out of Pacific." The group stared out at the viewer, and Stalin gestured with open arms over the caption "Honest Mister, there's nobody here but us Koreans."5 Clearly, cartoonist David Low did not believe any Communist claims of non-involvement in the actions of the North Koreans.

Figure 2 illustrated the nation's post-World War II policy of response to threatening international crises. The first time the United States reacted to a perceived threat of Communist expansion, it supported a beleaguered Greek government fighting Communist guerillas beginning in 1947. Then, about a year before the Korean War broke out, the United States successfully completed an 11 month airlift in response to the Communist attempt to seal off West Berlin in 1948. Thus, Americans considered the Berlin and Greek crises to be solved as the burnt out fuses on those bombs indicate. But Uncle Sam's fast pace in Figure 2 represents a desire to respond quickly to the newest emergency. Sam's buckets labeled "arms" and "aid" indicate either a belief or a hope that, like in Berlin and Greece, the US could respond with supplies and money, not men. The caption "Dangerous but necessary," however, indicated even that level of response was considered cautiously.66 Despite fears of becoming embroiled in an Asian land war, Americans at the outbreak of the Korean conflict seemed willing to send their aid. Even in that first week after the outbreak of war, the desire for quick response to avoid history repeating itself is illustrated by the headline of a story adjacent to this cartoon entitled "Washington's Firm Stand: 'No More Munichs.' "7

| A frenetic Uncle Sam, sleeves rolled up, dashes toward a bomb in the foreground labeled "Korea Crisis" with a short fuse burning. Sam carries two water buckets "arms" and "aid." In the background are two other bombs, identified as "Berlin Crisis" and "Greek Crisis," sitting in puddles of water where US arms and aid already worked to extinguish their fuses. |

Early public support for more extensive action was shown in another image that week titled "Pinch hitter" under a headline "Opinion in All Sections Is Unanimous In Support of Truman's Course." President Harry S. Truman dressed in baseball attire warmed up by swinging two bats labeled "U.S. Air Force" and "U.S. Navy." The pitcher sported a Stalinesque mustache and wore a uniform with the name "Reds." The call "Truman now Batting for Korea!!" was made by a man tagged "Pacific League Umpire," while the "Wall Street Bleachers" in the background are filled with cheering figures labeled "Stock Market."8 Here the United States, represented by Truman, is viewed as the leader for a response to the crisis.

Figure 3 characterized the non-Communist nations as angry bees driven from their hive by the Korean invasion under the caption "Starting something?"9 This view of the allies as a swarm is indicative of support for multilateral action. By the time this image appeared on 9 July 1950, the United Nations had requested that the United States lead a UN force of member nations to repel invading North Korean forces. After six months of conflict, another image contained four cannon muzzles raised together in a pyramid shape pointed skyward. Three of them were labeled "USA," "Britain," and "other Atlantic Pact Nations" with the caption "Together We Stand."10 The artist left no doubt that the international community was united against Communist aggression.

| Figure 3 Starting something? Edwin Marcus, New York Times |

|

But allied efforts were not always smooth. As the war stalemated after a year, some of the UN partners chafed at various aspects of American command and feared they would be pulled into a larger US-Soviet war that might expand into their European backyard. One image from late June 1951 depicted Uncle Sam and Mao facing each other across a poker table, using soldier figures as chips. Behind Mao stood Stalin, but behind a worried-looking Sam were a dozen world leaders labeled "United Nations." The caption, "Kibitzer's Delight," clarified one of the main problems the US faced, that of leading a group with some common, but other divergent goals.11

Once the United Nations approved joint action to repel the North Korean invasion, the United States combined forces with its allies to aid South Korea. Almost 30 nations eventually contributed to the UN effort. Sixteen provided troops, the largest numbers coming from South Korea, the United States, the United Kingdom, Turkey, Canada, and Australia. South Korea put almost 600,000 men in arms under UN command and American forces numbered over 302,000 compared to almost 14,200 from the next closest contributor nation.12 In addition, the United States had overall military command control and spent $54 billion for the war.13 Thus, the war effort was seen by the American public as largely a US operation. Figure 4 captured this sentiment. Uncle Sam as an American GI seemed more bothered than happy to see his UN partner, in the cartoon titled "Not Much Help, But It's Nice to Have Company."14 The UN symbolized as a child called into question its maturity and usefulness to US forces. With the United States providing 86 percent of the naval power and 93 percent of the air effort, the American public felt that the contributions of the UN allies seemed equivalent to the impact of the child's water pistol.15

| Uncle Sam, in fatigues and helmet, aims his rifle out from a trench toward distant hill. He looks with bemusement to his left at a small child wearing a paper hat labeled "U.N." The stern youngster, one hand in his pocket, fires a small squirt gun toward the enemy. |

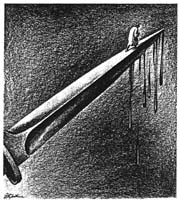

The sentiment of US soldiers about fighting again also was illustrated in this era. The feeling they were fighting someone else's war was shown in one cartoon that featured a long line of soldiers winding through the hills marching with tanks and other equipment as one soldier asked his neighbor "Where do we volunteer next?"16 The unpopularity of the military draft was the message of a cartoon that featured a big, burly, gruff sergeant identified as the "draft" hovering over a soldier labeled "volunteers" who is sleeping under his covers. The caption "So you hate to get up" reinforces the anti-draft sentiment.17 President Truman reinstated the World War II draft and extended the terms of enlistments in the first month of the war in order to rebuild the numbers of active forces of the US military. The reserves were essential to the US military's success in Korea and 77.5 percent of the enlisted men comprising those forces were World War II veterans.18 It is easy to understand that returning to a military regimen after several years of civilian life would be an unpopular prospect for most men who had moved on to new lives after their previous war service. A field soldier's perspective was shown in Figure 5 "Situation Fluid." Here a GI slogged away against the flooding Communist enemy represented by heavy rain and chest-high water.19

|

Figure 5 |

The themes of editorial art included domestic concerns within two weeks of the war's outbreak. Adjacent to a story titled "War Strains Expose Economy's 'Soft Spots,' The Pressing Problem is How to Avoid Inflation Without Harsh Controls" that reflected a fear of returning economic woes, was the "Breathing Down His Neck" image of Figure 6.20 This shows the problems government leaders faced in trying to reduce taxes with the expenses of a new overseas war looming in the background, as well as the public's anxiety over the war's possible effects on them as citizens.

|

Breathing Down His Neck Ned R. White The Akron Beacon Journal |

In another image reflecting domestic factors titled, "Two Lines to Hold," President Truman sat at a desk, focused on two wall graphs above him labeled, "Aggression" and "Inflation."21 Each graph featured steadily rising indicators representing the link between the war effort and the domestic economy, thereby hinting at potential problems for the nation. Escalating inflation rates in the post-World War II era resulted from more money in circulation due to expanded consumer credit, high employment levels, rising wages, and booming consumer spending. Truman's concern was how to level off such increases and still respond to Communist proliferation. Several events in recent years led to the sentiment reflected in the rising "aggression" graph, including the Berlin Blockade and the triumph of Mao Zedong's Communist revolution in China less than a year before the Korean War began. Truman and others, including the cartoonist Herblock, considered these two problems crises that the nation must attack. One bright spot in the domestic economy and in the nation's war plans was illustrated in a cartoon "The Sky Writer," which depicted a plane labeled "US Industries," writing "Preparedness" across the sky as Stalin looked on from around the globe.22 The nation's past record of quick action in war was considered a great strength, not to mention its ability to keep the economy growing. The clarity of issues in the nation's editorial cartoons kept Americans attuned to the domestic problems facing the president and the nation due to the new military situation in Korea.

The country's weariness from two world wars was evident in an image titled "Back in the Saddle Again," which depicted the American people as a tired, nervous workhorse as an approaching hand carried a bridle labeled "All out war effort."23 Twentieth-century wars had brought deprivation and sorrow on various scales to the American people. With another war under way, concerns about a national return to normalcy also occupied citizen's minds and was captured by editorial artists.

Worry over domestic Communists prompted other images. One showed a larger-than-life-sized Uncle Sam and a second man carrying the UN flag running to aid a figure labeled "Korea" being held on the ground and beaten up by a man tagged "Stalin." Another figure, representing "local communists," clung to Sam's knee blocking his way, and shook his fist at Sam crying "Hands Off Korea! Hands Off Korea!"24 Americans' fears about Communist infiltration were stirred by the accusations of Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy and others. These feelings were captured in this image depicting treacherous domestic Communists willing to allow the Soviets to attack South Korea, but unwilling to let the United States and UN come to the Koreans' aid.

When Truman fired General Douglas MacArthur, commander of UN forces, less than a year into the war, mixed public opinion showed up in editorial cartoons. MacArthur enjoyed a wide following for his heroics in World War II, but some Americans also understood the problems that his style of military leadership created for the war effort. MacArthur's commander-in-chief warned the general to watch for signs of Chinese Communist military participations with the North Koreans as UN troops advanced through the north toward the Chinese border. Everyone ignored warnings from the Chinese government that it would not accept UN forces near its border, which were issued through representatives of the neutral Indian government. American intelligence sources did not believe Chinese forces would intervene in the war; even American editorial views, including those of the New York Times, doubted Chinese concerns and supported the northward push of allied forces.25 And MacArthur ignored field reports of Chinese troop sightings and prisoners, while at the same time being very vocal about his belief that UN forces could and should attack and defeat China. Of course, once Chinese troops flooded across the border in late November 1950 and rapidly pushed UN forces back, MacArthur's position was untenable. Eventually, his calls to attack China in contravention of the US policy of containing the war to Korea led even the Joint Chiefs of Staff to agree with Truman that it was time to relieve MacArthur of command.

To illustrate the depth of sentiment on both sides and as an editorial statement, the New York Times assembled a section of "Cartoonists' Reaction to President Truman's Dismissal of General MacArthur," which included four images on each side of the matter. Much of the American public was uncomprehending of the larger diplomatic and political reasons for limiting the war in Asia, and saw only the dismissal of a national hero. Yet the existence of cartoons representing both positions indicates that not all Americans opposed the firing. In support of Truman's actions was Figure 7, "A choice of explosions," with its large bomb and fuse that spelled out "War in China," while the Washington Capitol dome vibrated from the "MacArthur Ouster" uproar.26 Ned White's image represented those who believed that the possibility of a larger war with not only China, but possibly the Soviet Union, was worse than any domestic fallout from Truman's action.

|

Figure 7

A Choice of explosions

|

|

On MacArthur's side, the image of a frantic Truman, Secretary of State Dean Acheson, and the Pentagon were pictured in a frying pan held by the arm of John Q. Public over a Bunsen burner fueled by public opinion in a cartoon entitled "The heat is on."27 Here is captured the weight of majority national sentiment that kept MacArthur in favor with Republicans and others eagerly seeking those "soft on communism" within the government. But a bottom line attitude was shown in a cartoon called "The Only Issue." A serious Uncle Sam held the "MacArthur controversy" in his hands and gazed longingly toward a sun on the horizon labeled "Unity."28 New York Times cartoonist Edwin Marcus suggested that nothing mattered more than a unified front against the enemy and keeping a nation at war working together toward victory.

During the drawn-out peace talks that finally ended the Korean War, cartoonists filled newspaper pages with images capturing the range of negotiators' problems. The possibility of finding a peaceful solution was very difficult according to Figure 8 titled "Just around the corner."29 No one knew which path would lead to peace and finding it was a constant struggle. Another image, tagged "Undisputed World Champ," pictured a straining, bespectacled strongman figure dubbed John Q. Public, struggling under the weight of a teetering barbell above his head labeled "Patience in Truce Talks."30 Roy Justus believed the American people were extremely tolerant of the incredibly long peace process.

|

Figure 8 Just around the corner Eldon Pletcher, The Sioux City [Iowa] Journal |

By mid-1953, when peace talks were finally coming to fruition, South Korean President Syngman Rhee was often depicted as the major obstacle to achieving results. He adamantly was opposed to accepting any plan that did not reunify Korea and actually worked to undo the armistice on the eve of final agreements.31 In Figure 9, "Resistance on the Last Ridge," Rhee's interference was characterized as significant enough to destroy the entire truce.32

|

Figure 9 Resistance on the Last Ridge Don Hesse, St. Louis Globe-Democrat |

|

For many cartoonists, the image of Rhee as a jailer was a favorite due to the view that he was holding an armistice hostage. In one image, Rhee sat on a chair outside a heavily constructed metal and block jail door with a rifle pointed at the occupant, a lady labeled "peace," who peered out pleadingly. The caption "Can't have you breaking out" painted Rhee as obstructionist.33 Another artist showed Rhee twirling a key on his finger, while behind him US President Dwight D. Eisenhower, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and a worried lady of peace implored him to unlock their padlocked cell.34 One artist extended Rhee's intransigence in the peace process to a larger target in an image from India called "Who likes Ike?" A shocked Ike tried to pull away and run from Rhee, who held Ike's arm, preparing to hit him with a stick as Jiang Jieshi looked on, his own stick in hand.35 Clearly, the message here was that the United States - in the form of Eisenhower - was acting against the wishes of its Asian allies, by perhaps not being tough enough with the Communists. The ultimate image was captured in Figure 10, "One Man's Decision in Korea," which put the power to end the bloodshed in the hands of one man.36 While one author identified the figure as Truman, it seems more likely, with a publication date in mid-1953 (after Truman's administration), and the figure wearing stylized traditional Korean attire, that Syngman Rhee is the lonely figure with the weight of decision upon his shoulders.37

|

Figure 10

One Man's Decision

Daniel R. Fitzpatrick, |

Once a truce was struck and major hostilities ended, confidence in the solution was tentative. Figure 11, the "Big One that Didn't Get Away," is a clear representation of public concern over what would happen next.38 A truce that was never signed by the South Korean government and that left many issues to be solved at a future conference, invited concerns from the public. But clearly, cartoonist Roy Justus considered "the problems to follow" the truce as a greater menace than the truce itself and captured the sense of future uncertainty that worried Americans.

Figure 11

Big One that Didn't Get Away

Roy Braxton Justus, The Minneapolis Star

That very future for the Korean peninsula and Asian relations, the problems facing both sides, and the hope that diplomacy would achieve peace were all part of the American public's emotions at the end of the war. Next to an article titled "Truce Opens a New Phase in World Struggle" was the image of a sky-high pile of boxes and papers identified as "Allied and Red Differences on Peace Terms" with lone negotiators peering at each other over the obstruction. The cartoon's caption "Buffer Zone" indicated artist Newton Pratt's view that the ideological gap between the two sides was akin to the demilitarized zone along the 38th parallel that physically divided the Koreas.39 However, hope sprang eternal in 1950s America. Figure 12, "New Assignment in Korea," depicted the hope that diplomacy could find peace in Korea where war had failed.40 From a perch 50 years later, it is clear that such a road still is being trodden by new generations of statesmen seeking the elusive goals pictured by Korean War editorial artists.

|

Figure 12

New Assignment in Korea

Daniel R. Fitzpatrick, |

|

Evaluating editorial imagery of this era evokes the lengthy history of this form of political commentary. Americans always have taken great interest in the political state of their nation, and the strength of the United States is grounded in its acceptance of self-criticism. The national legacy of editorial cartooning reveals "the good sense, skeptical outlook, and jovial attitude of the artists' audience."41 The nature of the art form tends toward the critical, but this does not devalue "the truth or history" contained therein.42

It is possible to find editorial cartoons that represent every possible viewpoint of every group in the nation. This article presented a small cross section to illustrate the variety of facets and perspectives that greeted Americans as they read their daily papers to learn of a war on the other side of the world and in which over 30,000 of their fellow citizens lost their lives. Any given newspaper will provide a wide ranging spectrum of attitudes over time and here a mere slice is visible from sources in all parts of the nation. No single regional perspective was planned; the New York Times itself selected images to accompany its editorial topics - sometimes in agreement, sometimes in opposition, sometimes both.

These cartoons are valuable to historians for what they convey about the moods, beliefs, apprehensions, and yearnings of the nation. Editorial artists are, after all, witnesses of events too, and therefore subject to the same impulses as their neighbors. Not unlike letters, diaries, or photographs, cartoons capture a moment's emotion to be preserved and mined later by historians trying to understand the past.

Seeing the Korean War through the popular art form of editorial art "is to see [the conflict] as the people saw it - in popular images, widely distributed and within the reach of most pocketbooks." It allows a historical observer to see "the controversy, criticism, and downright acrimony" which flowed through the nation during the time span of the conflict; to feel the emotional highs and lows of the people and their government and to embrace the traits that epitomize the oldest democracy and its diplomatic ideology.43

Catherine Forslund is an Assistant Professor of History at Rockford College in Illinois.

Endnotes

1. Roger A. Fischer, Them Damned Pictures: Explorations in American Political Cartoon Art (North Haven, CT: Archon Books, 1996), p. 2.

Return to body of article

2. Almost all the images used and described in this article came from the pages of the New York Times. The Times lists the "home" paper in which the cartoon first appeared. Where possible, citations here include the artist, the original paper of publication, and the date and page for the cartoon's publication in the Times. Cartoons not found in the Times are cited from those sources.

Return to body of article

3. Edwin Marcus, New York Times, 2 July 1950, p. 7E, reprinted by permission of the Marcus family.

Return to body of article

4. Morris, The Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, 2 July 1950, p. 8E.

Return to body of article

5. David Low, The London Daily Herald, 2 July 1950, p. 3E.

Return to body of article

6. Vaughn Shoemaker, The Chicago Daily News, 2 July 1950, p. 8E. Reprinted with special permission from The Chicago Sun-Times Inc. @2002.

Return to body of article

7. James Reston, 2 July 1950, p. 3E.

Return to body of article

8. Cyrus Cotton "Cy" Hungerford, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 2 July 1950, p. 8E.

Return to body of article

9. Edwin Marcus, New York Times, 9 July 1950, p. 9E, reprinted with permission of the Marcus family.

Return to body of article

10. Tom Little, Nashville Tennessean, 24 December, 1950, p. 5E.

Return to body of article

11. John Fischetti, N.E.A. Service, Inc., 24 June 1951, p. 3E.

Return to body of article

12. Harry G. Summers, Jr., Korean War Almanac (New York: Facts On File, 1990), pp. 289-90.

Return to body of article

13. Santa Cruz Public Libraries, Statistics on 20th Century Wars Involving the United States, http://www.santacruzpl.org/readyref/files/t-z/wars.shtml, 12 January 2002; and Al Nofi, Statistical Summary of America's Major Wars, The United States Civil War Center, http://www.cwc.lsu.edu/cwc/other/stats/warcost.htm, 12 January 2002.

Return to body of article

14. Cecil Jensen, Chicago Daily News, in Nancy King, A Cartoon History of United States Foreign Policy (New York: Pharos Books, 1991), p. 21. Reprinted with special permission from the Chicago Sun-Times, Inc. @ 2002, originally published in 1950.

Return to body of article

15. Walter LaFeber, America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945-1992, 7th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1993), p. 105.

Return to body of article

16. Herbert "Herblock" Block, Washington Post, 24 December 1950, p. 5E.

Return to body of article

17. Clifford H. "Baldy" Baldowski, Atlanta Constitution, 15 July 1951, p. 10E.

Return to body of article

18. Summers, Korean War Almanac, pp. 188-89.

Return to body of article

19. Ned R. White, staff cartoonist, The Akron Beacon Journal, 23 July 1950, p. 5E, reprinted with permission.

Return to body of article

20. Ned R. White, staff cartoonist, The Akron Beacon Journal, 9 July 1950, p. 10E, reprinted with permission.

Return to body of article

21. Herbert "Herblock" Block, The Washington Post, 23 July 1950, p. 6E.

Return to body of article

22. Edwin Marcus, New York Times, 23 July 1950, p. 9E.

Return to body of article

23. Vaughn Shoemaker, Chicago Daily News, 9 July 1950, p. 3E.

Return to body of article

24. The Hat Worker, 23 July 1950, p. 10E.

Return to body of article

25. Jon Halliday and Bruce Cumings, Korea: The Unknown War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1988), p. 112.

Return to body of article

26. Ned R. White, staff cartoonist, The Akron Beacon Journal, 15 April 1951, p. 5E, reprinted with permission.

Return to body of article

27. Leo Roche, The Buffalo Courier Express, 15 April 1951, p. 5E.

Return to body of article

28. Edwin Marcus, New York Times, 15 April 1951, p. 9E.

Return to body of article

29. Eldon Pletcher, The Sioux City [Iowa] Journal, 6 January 1952, p. 4E, reprinted with permission.

Return to body of article

30. Roy Braxton Justus, The Minneapolis Star, 26 July 1953, p. 5E.

Return to body of article

31. South Korean President Syngman Rhee's subordinates engineered the escape of over 25,000 North Korean POWs, in addition to his threats to continue the war alone and not abide by the armistice agreement. Halliday and Cumings, Korea: The Unknown War, pp. 197-98; Summers, Korean War Almanac, p. 49.

Return to body of article

32. Don Hesse, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 21 June 1953, p. 3E.

Return to body of article

33. Herbert "Herblock" Block, The Washington Post, 28 June 1953, p. 3E.

Return to body of article

34. David Low, The Manchester Guardian, 28 June 1953, p. E5.

Return to body of article

35. Shankar's Weekly, New Delhi, 28 June 1953, p. 5E.

Return to body of article

36. Daniel R. Fitzpatrick, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 28 June 1953, p. 5E, reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 2001.

Return to body of article

37. Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, The Image of America in Caricature and Cartoon (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, 1976), p. 149.

Return to body of article

38. Roy Braxton Justus, The Minneapolis Star, 26 July 1953, p. 2E, reprinted with permission, Star Tribune.

Return to body of article

39. Newton Pratt, The Sacramento Bee, 2 August 1953, p. 5E.

Return to body of article

40. Daniel R. Fitzpatrick, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 9 August 1953, p. 5E, reprinted with special permission of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 2001.

Return to body of article

41. Amon Carter Museum, p. vi.

Return to body of article

42. Ibid., pp. 3-4.

Return to body of article

43. Ibid., p. vi

Return to body of article