Protracted Conflicts, Crises, and Ethnicity:

The Arab-Israeli and India-Pakistan Conflicts, 1947-20051

Hemda Ben-YehudaBar-Ilan University, Israel

Meirav Mishali-Ram

Bar-Ilan University, Israel

Abstract

This study used international crisis as a tool to analyze Protracted Conflicts (PCs). Two core attributes, the compound nature and over all magnitude, were formulated and applied to the Arab-Israeli and India-Pakistan PCs in order to address three theoretical questions. First, how do we measure the compound nature of a PC and do PCs change over time? Second, how do we measure overall PC magnitude and does it change over time? Third, do the compound nature and magnitude of a PC correspond?

We found that the concepts of compound nature and overall magnitude are useful and necessary tools for a systematic analysis of the two PCs in the Middle East and South Asia, over the years 1947- 2005. The two PCs are similar in some leading attributes (e.g. colonial tradition, religious and territorial stakes, nuclear complexity, outbreaks of violence and duration) but differ in others (salience of the ethnic and interstate dimensions, characteristics of ethnic actors, and overall magnitude). Regarding the correspondence between the compound nature and overall magnitude in PCs, we found some correspondence in both regional conflicts but not to the same degree.

Given the importance of delineating PC dynamics, the study found that stability and order in the interstate domain cannot be detached from events that unfold in the ethnic-state domain. While outcomes of crises vary over time, compromise in ethnic-state confrontations was less evident than in interstate ones. The study concluded that a compound nature, or a primarily ethnic characterization of a conflict, not only prolongs the confrontation but also diminishes the prospects of conflict resolution. Notwithstanding the importance of territory, nuclear spread, and religion as core aspects in PCs, the study draws attention to ethnic actors and issues as salient aspects in international crises and conflicts, the heart and core of world politics.

INTRODUCTION

1 In this study we use international crisis in order to analyze the dynamics of protracted conflicts (PCs). We compare and contrast the Arab-Israeli conflict in the Middle East and the India-Pakistan confrontation in South Asia over the years 1947-2005. Both violent conflicts, vital in today's world politics, were born of inter-communal strife long before the creation of independent states. After British rule ended the interstate dimension of these conflicts became salient, raising the scope of violence to several outbreaks of full-scale war. While the core issues at stake in both involve territory, religion, and security, the two conflicts differ in the salience of the ethnic and interstate dimensions in their crises, in the attributes of ethnic actors that participate in them, in crisis magnitude, and consequently in their overall conflict dynamics and change over time.

2 By exploring crisis within PCs we attempt to operationalize the abstract concept of international conflict and gain knowledge about two prolonged and violent confrontations in the Middle East and South Asia. In the framework section we outline two core conflict attributes — the compound nature and the overall magnitude — and propose comparative analysis as a new mode of inquiry for these two rivalries. More specifically, we address three questions. First, how do we measure the compound nature of a PC and do PCs change over time, becoming more or less compound in nature? Second, how do we measure overall PC magnitude and do the gravity of threat, level of violence, and extent of accommodation in PCs change over time? Third, do the compound nature and the magnitude of a PC correspond?

3 Area specialists do not commonly use theoretical indicators or a multiple comparative outlook, though popular and policy circles do mention similarities and differences regarding these two conflicts. We propose that by comparing both cases and detecting the common and unique traits across conflicts we can highlight some theoretical generalizations while learning important lessons about each particular confrontation. To improve our understanding of international conflicts in the future, the benefits of using operational crises attributes for analyzing PCs and choosing a comparative mode of analysis should justify a similar investigation strategy for other conflicts in world politics.

4 The study consists of four parts. First, we review the literature on crisis and conflict, focussing primarily on the ethnic dimension. Then, we present a framework for the analysis of PCs and introduce the concepts of compound conflict and magnitude in order to address the research questions. In the third part, we apply the framework and analyze findings from the Arab-Israeli and India-Pakistan conflicts. We conclude with some implications for future research on crisis and conflict in world politics.

FROM CRISIS RESEARCH TO CONFLICT ANALYSIS

5 From a theoretical standpoint, we integrate three research topics: crisis, conflict, and ethnicity. We begin with the operational oriented study of international crisis based on the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) project and suggest a way of using crisis indicators to describe conflict dynamics. Further, by adding ethnicity to the analysis we propose an outlook that highlights the role of actors and issues during international confrontations.2

International Crises and Protracted Conflicts

6 According to Michael Brecher and Hemda Ben-Yehuda, an international crisis occurs when there is a change in type and/or an increase in the intensity of disruptive interactions between two or more states, with a heightened probability of military hostilities that destabilize their relationship and challenges the structure of an international system.3 The analysis of crises in the current study follows this definition, focussing on international crises from a systemic point of view, not on decision-makers' subjective perceptions.

7 International crises differ from each other with regard to the extent of change they create, the intensity of disruptive interactions, and the degree of destabilization caused to the structure of an international system. Scholars have introduced several indexes to classify crises by their importance. Brecher and Patrick James formulated an "Index of Severity," which includes six components: number of actors, superpower involvement, geo-strategic salience, heterogeneity among the actors, the issues at stake, and level of violence.4 Ben-Yehuda and Shmuel Sandler developed a Crisis Magnitude Index (CMI) made up of another composition of six elements: gravity of threat, number of actors, superpower involvement, level of violence, crisis management techniques, and crisis outcome.5 However, though examining severity/magnitude of crises, the two indexes differ in their goals. While Brecher and James used their index to assess the intensity of international crisis, Ben-Yehuda and Sandler used theirs to evaluate transformation in PCs. In this study we address crisis magnitude in order to characterize conflict dynamics and use a magnitude index that is a variation on the Ben-Yehuda and Sandler index. In doing so, we use the operational definition of crisis and magnitude to describe PCs.

8 Crises within PCs are confrontations in which the issues at stake and the conflicting goals between the rival states escalate, and the likelihood of hostilities increases significantly. By contrast, the reduction of crisis occurrence or modifications in the mode of crisis behavior, reflect a change in the pattern of relations among the involved actors in a conflict and indicate a more relaxed phase in a conflict.6

9 Defined as hostile interactions that occur over prolonged periods of time, PCs are processes, not events. And, "while they may exhibit some breakpoints during which there is a cessation of overt violence, they linger on in time and have no distinguishable point of termination . . .."7 Brecher and Jonathan Wilkenfeld's operational definition of protracted conflicts includes at least three international crises between a pair of states within the period of five years.8 Their concept of a PC is similar to that of "enduring international rivalry" as defined in the "Militarized Interstate Disputes" (MID) project.9 As we shall see in the empirical section below, the Arab-Israeli and India-Pakistan conflicts meet all these conditions.10

Ethnicity and Conflict

10 The centrality of ethnic strife has become more salient since the end of the Cold War, both in reality and in IR research. Violent ethnic conflicts occurred constantly during the twentieth century and increased in their amount and intensity in its latter years.11 Studies on ethnicity have given a great deal of attention to the unique nature of ethnic conflict.

11 Most of the studies define ethnicity according to objective and subjective criteria, recognizing it as a common group identity based upon perceptions among members and non-members of the group. Ethnic identity consists of homogeneity in one or more characteristics: nationality, religion, language, race and ancestry, culture, and history.12 As such, ethnicity serves as a unifying element that often leads to national consolidation and statehood.13 It may also lead to conflict within a state or among states when the boundaries of ethnic identity and state sovereignty do not coincide. The focal point is on cultural sources of the conflict, so that all conflicts based on group identities — race, language, religion, tribe, or caste — can be called ethnic.14

12 Following the same mode of analysis and neglecting the role of ethnic actors as core participants in the confrontation, Samuel Huntington identified the multiple ethnic distinctions among various ethnic groups as a comprehensive phenomenon of "ethnic diversity," which he, like others, anticipated would generate many violent disputes in world politics. With the collapse of Cold War enmities, new forms of identity will inevitably be constructed upon new patterns of hostility. Differences of religion and culture, says Huntington, will provide the needed template for the clashes to come.15

13 Ethnic mobilization among minority populations in multiethnic states often led to demands for self-rule (autonomy) or for complete secession. In other instances ethnic demands are related to greater participation in the government of the central state.16 Ethnic groups of different kinds frequently conducted struggles against states to achieve their rights, which in many cases led to interstate crises focussed on ethnic issues.

14 Why is ethnicity so important in the analysis of crises and conflicts? Ethnic heterogeneity and struggles aimed at national independence often get political and military assistance from neighboring states. They lead to the creation of similar organizations in bordering states that consist of similar minorities and become a major source of international conflict.17 The international media also contributes to the international dimension of ethnic conflicts by bringing the occurrences to the consciousness of the global community, and provoking public opinion, thereby creating pressure on decision makers to act more intensively to solve ethnic disputes.18

15 But when most scholars explored ethnic confrontations, they did not pay full attention to the ethnic actors in their research. Typically, in the ICB project, when Brecher and Wilkenfeld investigated the relationships between ethnicity and international crises, they differentiated between secessionist and irredentist cases based upon the parties involved but characterized the confrontation without investigating the ethnic actors in depth.19 However, Brecher and Wilkenfeld acknowledged the role of non-state actors in destabilizing regional/global relations. In their detailed case-study summaries they described the activity of non-state actors mainly during the pre-crisis period.20 Moreover, in the qualitative and quantitative analysis of international crises ICB introduced the concept of crisis initiators and analyzed diversity in the identity of the entities that trigger international crises. It is here that non-state actors/ethnic groups find their expression in the ICB dataset.

16 An exception to this state-centric trend is the classification of ethnonationalist movements in the Middle East proposed by Alexis Heraclides, which also classifies ethnic conflicts. He distinguished among 14 types of revolutionary ethnonationalist movements, two of which — anti-occupation and classical irredentist — he applied to the Palestinians.21

17 In sum, this study highlights the participation of ethnic actors in crises and explores the issues they introduce into the crisis agenda and their role in crisis outcomes. We focus on ethnic groups that transcend the boundaries of a single state, interact with other states, and become a major driving force toward international confrontations.

18 Moreover, since ethnicity is not a tangible concept, the hard-to-measure "common identity" as a core classification element is replaced with the more concrete element of "actor." This change does not indicate a rejection of the notion of common ethnic identity. Rather, it suggests that probing the puzzle of ethnicity requires first identifying the major adversaries involved — states and non-states. To be precise, the focus changes from minorities, peoples, groups, or mythical leaders to ethnic actors, defined by Ben-Yehuda and Mishali-Ram as Ethnic-NSAs (ethnic non-state actors).22 These actors operate within and beyond the boundaries of sovereign states. Their behavior, especially their transnational activity, escalates international confrontations.

19 This actor-based orientation to ethnicity follows Ben-Yehuda and Mishali-Ram who used actors and issues as core concepts for a typology of international crises, which classifies international crises into three distinct categories: interstate, interstate-ethnic, and interstate-NSA.23 In the interstate type crisis all actors are sovereign states, confronting each other over state-centric issues of existence, power, territory, and influence. In an interstate-ethnic crisis state adversaries along with ethnic-actor(s) participate in the confrontation. Such crises involve one or more of five ethnic issues (cross-border tension, ethnic kinship/minority ties, terror, de-colonization struggles, and civil war). The most salient among these issues is regarded as the primary issue in the confrontation. In an interstate-NSA crisis, non-ethnic-NSA(s) are involved alongside state actors in the crisis over issues that are related to states' domestic-political-regime concerns.

20 Based on this typology ethnic actors were found to affect the gravity of threat, level of interstate violence, extent of accommodation in crisis outcomes, and the overall magnitude of an international crisis.24 Theoretical logic as well as empirical data support the basic stipulation that the "rules of the game" as ethnic actors play it, which are different from those followed by states, disrupt customary relations between states and obstruct the accommodative termination of crises. The cross-border and terror activities or civil war incidents, triggered by ethnic actors, drag states into international crises and sometimes even to wars.25

21 Finally, in the actor-based typology mentioned above, there are two general assumptions regarding ethnic actors: first, ethnic actors change over time in defined stages of development; and second, with the growth of ethnic actors they gain power and change their patterns of activity.26 It is these changes, which take place over prolonged timeframes, that affect the nature of protracted ethnic confrontations. Such changes necessitate a shift in outlook from a single crisis to an ongoing conflict.

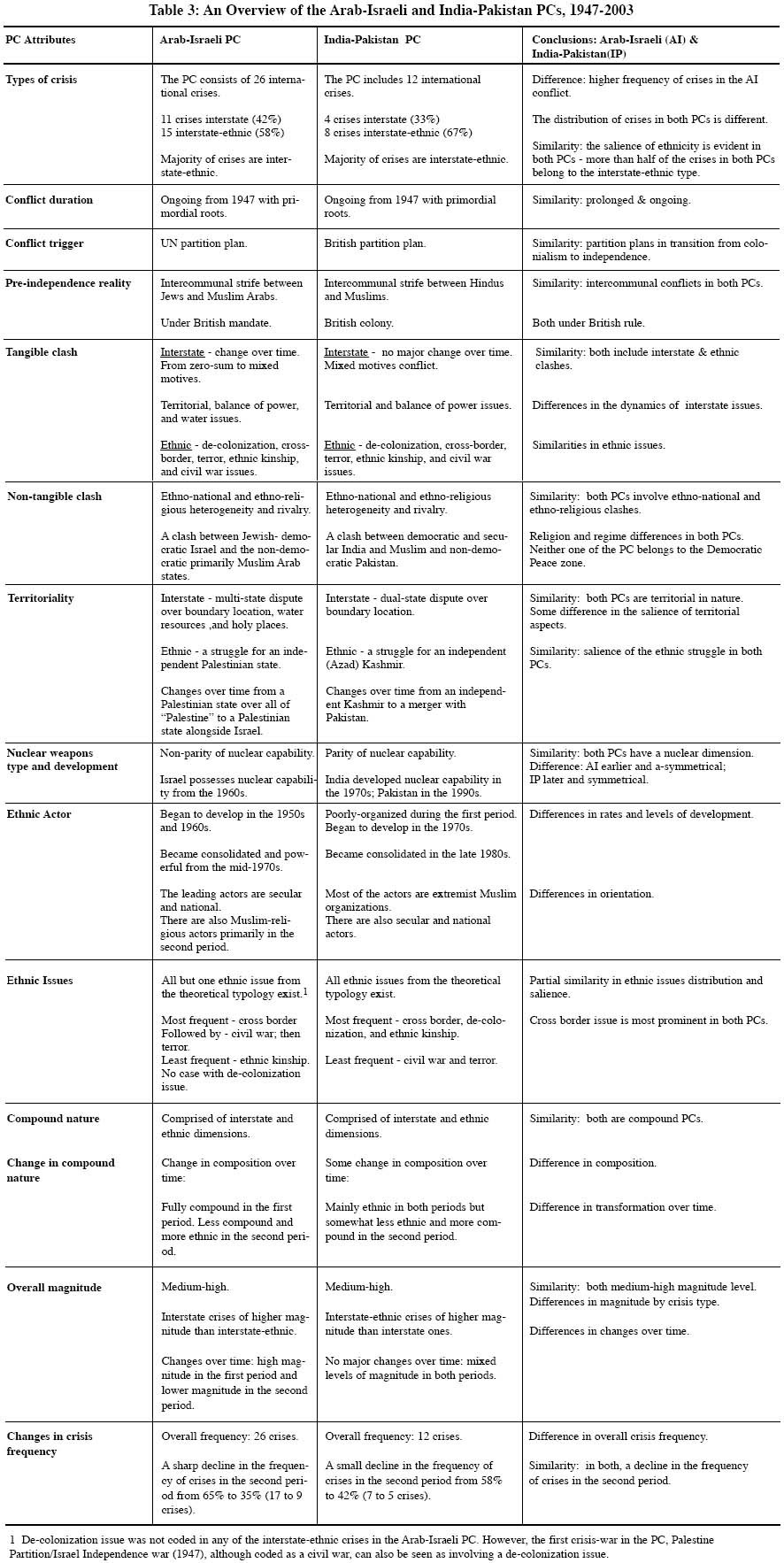

FRAMEWORK

22 In this study we move beyond crisis and focus on PCs as our main concern. We compare the Arab-Israeli and India-Pakistan conflicts and address three questions. First, how do we measure the compound nature of a PC and do PCs change over time, becoming more or less compound in nature? Second, how do we measure overall PC magnitude and do the gravity of threat, level of violence, and extent of accommodation in PCs change over time? Third, do the compound nature and the magnitude of a PC correspond?

23 A PC, as noted earlier, is a process of hostile interactions involving at least three international crises between a pair of states within the period of five years.27 In order to probe PCs we offer two core concepts derived from crisis research: compound nature and overall magnitude.

24 To address our research questions we first establish a terminology to characterize PCs based upon the type(s) of international crises that unfold within the PC. Our starting point is that different types of crisis manifest themselves in unique processes. If we want to describe and understand PC dynamics it is both necessary and useful to begin by characterizing the crisis composition within the PC.

25 How do we use the threefold typology of international crises (interstate, interstate-ethnic, and interstate-NSA) to characterize PCs? We build upon the assumption that just like crises differ in type and core attributes, so too is the case with PCs. Not all PCs are alike. We then use the composition of crises within a PC to distinguish between compound and non-compound types of conflict. Some PCs involve only one type of crisis (interstate crises, interstate-ethnic, or interstate-NSA). All PCs that involve only one type of international crisis are non-compound in nature. For example, the crises that broke out during the prolonged confrontation between the superpowers within the Cold War (coined by ICB the East-West PC) involved only interstate crises, thereby resulting in a non-compound type PC. Other PCs involve more than one type of international crisis, consisting of two or all three crisis types.28 A PC is compound when it encompasses more than one crisis type. We call these PCs compound to reflect the diversity in crisis types within the conflict. Both the Arab-Israeli and India-Pakistan disputes meet the criteria for compound conflicts, including interstate and interstate-ethnic crises.

26 A conflict ceases to be compound when one or more of its crisis types cease(s) to exist. Similarly, if a change in the rate of composing crisis types occurs over time the compound nature also changes and the conflict becomes more (or less) compound in nature. To illustrate, the Arab-Israeli PC, as will be described below, consists of interstate and interstate-ethnic crises. In the pre-1974 period there was a rather similar distribution of interstate and interstate-ethnic cases in the PC (see Table 1 below) and it was characterized as a compound conflict. In the post 1973 years the conflict changed its composition and became less compound since most of its crises in this period were interstate-ethnic in type.

27 Furthermore, to explore the overall magnitude of PCs, we again use crisis as an indicator to characterize PC dynamics. For this purpose we employ three of the components in Ben-Yehuda and Sandler's Crisis Magnitude Index (CMI): gravity of threat, level of violence, and extent of accommodation in crisis out-come.29 Highest magnitude is present when the gravity of threat in a crisis involves existence, grave damage, or territory threats; when the crisis is conducted through intense violence; and when the crisis ends unilaterally, fades over time, or is concluded by an imposed agreement. Other types of threat, low or no violence, and accommodative outcomes, indicate low magnitude. By adding the values for each of the three indicators we obtain the overall magnitude. A high value on each of the indicators equals 1 and a low value equals 0. Hence, the possible range for overall magnitude is between 0 (a low level on all three indicators) and 3 (a high level on all three).

28 While the first two research questions relate to the compound nature and the overall magnitude of PCs, the third question focuses on the spillover effects between both attributes. In exploring conflict dynamics we expect that along with a decline in the compound nature of a PC we will find a corresponding decrease in the overall magnitude of the conflict. The logic behind this expectation lays in the dual nature of compound conflicts that involves interstate and interstate-ethnic type crises.30 In such conflicts states and ethnic actors take part, contending over realist and ethnic issues. The two types of crisis mutually affect each other by imitation and learning processes, creating spillover effects. Escalation and high magnitude in one type (i.e., interstate) is likely to beget similar traits in the other (i.e., interstate-ethnic) or vice versa. Moreover, high tension in one crisis type is likely to impede moderation in the other, so that the overall magnitude of the PC increases. Contagious effects occur also when one of the two crisis types is resolved or decreased, and the PC becomes less compound. In such cases some of the issues in dispute are agreed and it is logical to expect spillover effects from the type of crisis where tension is reduced (i.e., interstate) to the other (i.e., interstate-ethnic), so that the overall magnitude of the PC drops.

29 Among the three indicators of conflict magnitude "outcome" is the one that establishes the link between one crisis and the next, because the mode in which a crisis ends sets forth the agenda for future interactions and confrontations. Thus, to examine the corresponding trends of the compound nature and overall magnitude of a PC we look at changes in the composition of crises throughout the PCs and specifically at their outcomes over time. Our findings, presented as similarities and differences in conflict dynamics between the two PCs, are followed by conclusions regarding the research questions.

FINDINGS: THE ARAB-ISRAELI AND INDIA-PAKISTAN CONFLICTS

30 In 2006, more than fifty years after the states involved in both PCs had gained independence, the Arab-Israeli and India Pakistan PCs are at a cross-roads.31 Although unique in some aspects, both are experiencing a relative reduction in interstate tension but not in ethnic violence, and both have been strongly affected by major world events. The 11 September attacks and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have altered the atmosphere of international relations and the rules of the game appear to have changed. Under the new rules of conduct there is much less latitude for "our freedom-fighters" vs. "their terrorists." Consequently the "gray areas" in which states could dabble with terrorists and/or support violent separatist groups are shrinking.32

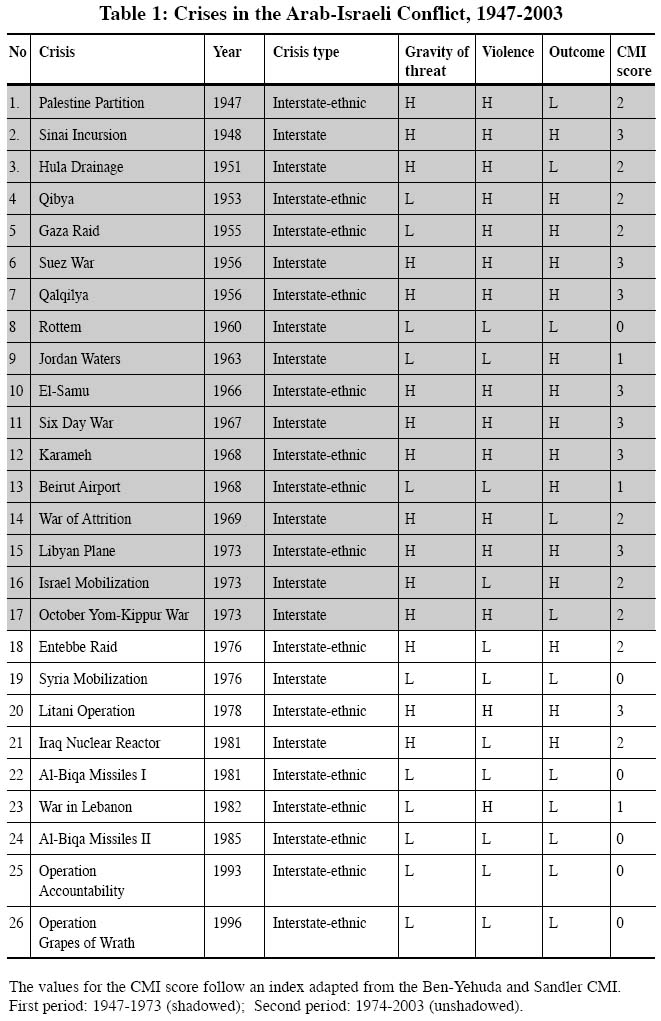

31 The salience of ethnicity in international crises and PCs is highlighted in Tables 1 and 2 below. Within the 26 international crises that have occurred in the Arab-Israeli PC between 1947-2003, 42 percent (11 cases) were interstate, and 58 percent (15 cases) were interstate-ethnic. Among the most prominent interstate crises were the June-Six Day War (1967) and the October-Yom Kippur War (1973), the former involving Israel, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt and the latter three of these states, excluding Jordan. Among the well-known interstate-ethnic crises are the Entebbe hijacking (1976) and the Lebanon War crisis (1982). Israel, Uganda, the PFLP, and Bader-Meinhof were involved in the first and Israel, Lebanon, Syria, and the PLO in the second.

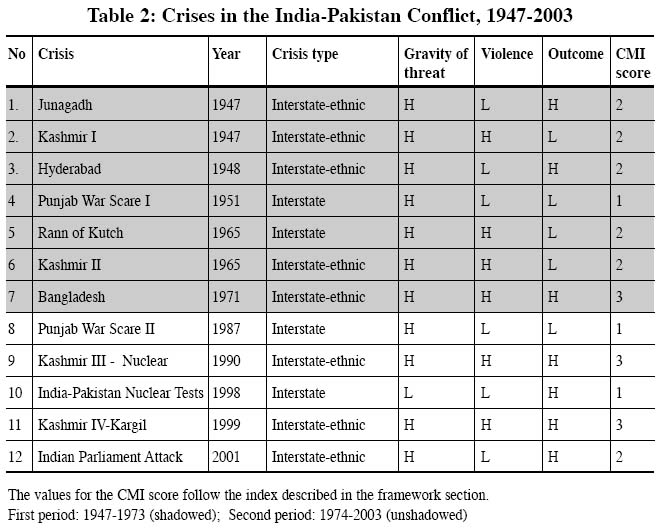

32 The salience of the ethnic dimension is even more pronounced in the India-Pakistan PC. Among the 12 international crises that occurred between 1947 and 2003, 33 percent (4 cases) were interstate and 66 percent (8 cases) were interstate-ethnic. The interstate crises in the PC included the Punjab War Scare crises I and II (1951, 1987), a crisis over the disputed territory of Rann of Kutch (1965), and the India-Pakistan Nuclear Tests crisis (1998). Prominent among the interstate-ethnic crises were four Kashmir crises (1947, 1965, 1990, and 1991) and the Bangladesh crisis-war (1971). All the Kashmir crises occurred over the disputed territory of Kashmir and Jammu, in which the minority population is Hindu.33

33 In order to examine change we follow the two periods, 1947-73 and 1974-2003, identified by the Ben-Yehuda and Sandler's study on the Arab-Israeli conflict. Their point of departure is that 1973 makes a useful demarcation line, since it constitutes the last interstate war over territorial-interstate issues, marking a shift in state behavior from violence to more peaceful modes of crisis management and conflict resolution. Moreover, from 1974 on, the ethnic elements in the conflict's crises gained prominence, reflecting a gradual transformation in the Arab-Israeli conflict.34 These two phases divide the India-Pakistan conflict into almost two equal periods of time, and enable the comparison of the two conflicts in parallel timeframes.35

34 In Table 3 a summary of core attributes is presented for both PCs focussing on types of crises, duration, triggers, pre-independence situation, tangible and non-tangible stakes in conflict, territorial and nuclear aspects, compound nature, ethnic actors and issues, and overall magnitude. In comparing the two conflicts we present similarities and differences between them, focussing on their compound nature and magnitude over time.36

Similarities in PC Attributes

35 After prolonged intercommunal struggles, partitions, and termination of British rule in 1947, both the Arab-Israeli and India-Pakistan rivalries unfolded as protracted conflicts. In both cases the roots of the conflict date back to the pre-state era. Both encompass, to some extent, a clash of civilizations between major religions and ideologies, as well as confrontations over tangible and valuable interests.

Table 1: Crises in the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947-2003

Display large image of Table 1

Table 2: Crises in the India-Pakistan Conflict, 1947-2003

Display large image of Table 2

36 Culturally, ethno-national and ethno-religious differences are central in the two conflicts. Distinctions between Muslim-Arabs and Jewish-Israelis, as well as between Muslim-Pakistanis and Hindu-Indians create ideological tensions among the parties to the disputes. In both cases there are also distinct political disparities, between the democratic regimes of Israel and India on the one hand, and the non-democratic regimes in the Middle Eastern Arab states and Pakistan, respectively, on the other.

37 Two of the leading ethnic actors, the Palestinian PLO and the Kashmiri JKLF, are national actors that fight for the establishment of independent states for their peoples. Although adopting religious symbols and values to promote their causes, these organizations operate primarily for self-determination. Other groups with religious orientations represent the ethno-religious aspects of the conflicts. Hizballah (the Party of God) in Lebanon, and internal Palestinian actors, like Islamic Jihad (holy war) and Hamas, which oppose many of the policies of the Palestinian Authority, are examples. These groups have posed a major political threat to the PLO by becoming popular and powerful organizations supported by the masses. Similarly, a network of extremist Islamic groups sponsored and controlled by Pakistan, have emerged as powerful actors in the India-Pakistan conflict. The pro-Pakistan radical Islamic Hizb-ul-Mujahidin (party of holy warriors) has gained greater power as compared to the independence-seeking JKLF, mainly in terms of terror potential. In recent years other Muslim-oriented organizations, such as Harkat-ul-Mujahidin and Lashkar-e-Toiba have also been active in the struggle over Kashmir.

38 The PCs in the Middle East and South Asia also resemble one another with regard to tangible issues of contention. As both PCs are compound in nature, they involve interwoven interstate and ethnic issues that create confrontations over multiple interests. In addition to the obvious ethnic issues, interstate concerns of territory, security, and influence, characterize both PCs. Ethnically-driven Palestinian fedayeen and Pakistani "freedom fighters" have crossed borders into Israel and Indian Kashmir and initiated crises between the rival states. Ethnic actors have employed terror as a major weapon in both PCs. In the Middle East Israel blamed the Arab countries, and in Asia India accused Pakistan of supporting and encouraging these actions on the basis of ethnic kinship and political interests.

39 Territory has been, and continues to be, a major issue in both conflicts. These bitter disputes, in which two groups claim the right to sovereignty over the same pieces of land, are related to both the interstate and ethnic domains. The interstate aspect of the territorial dispute is predominantly about the placement of borders. In the Arab-Israeli conflict it also involves a substantial dispute over control of the sources of the Jordan River and a struggle over the use of water resources to cultivate arid land.

40 The ethno-national aspect of territory in the Arab-Israeli conflict relates mainly to the Arab states-backed request for an independent Palestinian new state. In the India-Pakistan PC it concerns the Pakistani-supported struggle of Muslim separatists for the "liberation" of Indian Kashmir (Azad Kashmir). India and Pakistan both refuse to create an independent Kashmiri state, as both of them claim it as their territory. Although coupled with other issues along the years, the two conflicts remain mainly territorial to date.

41 The two conflicts, compound and prolonged, involve manifold and grave stakes, mixed levels of violence, and diverse forms of outcomes ranging from non-accommodative imposed agreements and unilateral acts, via tacit understandings to the accommodative endings of semi-formal and formal agreements. Both, the data tell us, are of medium-high magnitude. Grave threats to territory, military damage, and influence have raised the conflicts' magnitude. Violence, which at times has escalated into serious clashes and war, has also contributed to their magnitude. Likewise, non-accommodative outcomes, expressed mainly in unilateral actions to end crises, also typify many of the cases in these PCs. Finally, the overall magnitude of the conflicts is also reflected in the persistence of crises outbreak throughout the conflict. However, as noted, in recent years there has been a decline in the frequency of crisis in both PCs.37

42 The similarities between the two PCs also include the conventional and nuclear arms races that have contributed to their high magnitude. Israel introduced the nuclear dimension into the Arab-Israeli conflict in the second half of the 1960s. India followed about a decade later and Pakistan in the 1980s. Persistent efforts to attain and/or improve nuclear capability are part of the balance of power struggle in both conflicts.

Differences in PC Attributes

43 The differences between the conflicts are both blatant and subtle. Most obvious is the overall size of the contenders. While Israel and the Arab states are small and medium-weight wrestlers, the two countries at the foot of the Himalayas are huge in size in terms of both territory and population. International attention, however, is far more focussed on the conflict in the Middle East.

44 In addition, while both conflicts involve intense activity carried out by ethnic actors the nature and development of these actors are unique. Although the India-Pakistan conflict is more ethnic in its composition as compared to the Arab-Israeli one, it is the latter that has involved more prominent ethnic actors. The Palestinian groups developed from unorganized groupings to well-known and powerful actors, both in the regional and global arenas. The Muslim actors in Kashmir developed at a slower pace and have not achieved a level of influence comparable to the Palestinians. A constant and rapid development was seen from the mid-1960s onward in the number and level of institutionalization of Palestinian actors, who changed from fedayeen and infiltrators into an "umbrella" organization (PLO) and other well-known and organized actors. The increase in number of actors and level of institutionalization, from "freedom fighters" to an "umbrella" organization in the India-Pakistan conflict occurred only in the late 1980s and it was not until the 1990s that these groups emerged as better-organized actors. This transformation happened when the organization, All Parties Hurriyat Conference (APHC), was formed in 1994 as a political front for 26 groups to further the cause of Kashmiri separatism. And, while the Palestinian actors obtained the support of powerful Arab states and gained international recognition from great powers and superpowers, the main recognition and support of the Muslim Kashmiri groups comes from Pakistan. These groups do, it should be noted, maintain relations with some outside Muslim organizations, including Afghani groups that came to their aid at the end of the Afghanistan war in 1989.

45 Although both conflicts are compound in nature, their dynamics and changes over time, in terms of crisis type, are different. While the Arab-Israeli conflict has become more ethnic and less compound, the opposite has been true in the India-Pakistan PC. The former is more balanced in its weighting of interstate and interstate-ethnic crises, while becoming more ethnic in recent years. The latter involves more interstate-ethnic crises throughout, while becoming somewhat less ethnic over time. These changes denote some relaxation in the interstate domain of the Arab-Israeli PC which coincides with a rise in ethnic strife. The confrontation between Israel and the Palestinians has managed to drag Arab states into crises with Israel from time to time as noted in cases 18-26 in Table 1, and has also manifested itself in the two outbreaks of Intifada. Overall, however, while these ethnic-state crises involve lower levels of violence than those in the 1947-73 years, and thereby a lower crisis magnitude, they still prolong the conflict and keep the grave danger of interstate escalation alive. By contrast, as noted in cases 8-12 in Table 2 the interstate domain in the India- Pakistan PC has not declined over the years, pointing to the gravity of stakes involved, including a severe territorial clash over Kashmir and the prospects of escalation to a nuclear confrontation. In this respect the ethnic element adds to the compound nature of the confrontation and is matched with a high magnitude and fragile balance of nuclear power.

46 These trends are also expressed in the frequencies of crisis outbreak. When we compare the trends of crisis outbreak over the two periods of time, the data in Table 1 illustrates that while 65 percent of crises in the Arab-Israeli conflict occurred between 1947 and 1973 (17 cases of the 26 in total), a much smaller share of 35 percent (9 of 26 cases) have occurred in the post-1973 years. Similarly, as noted in Table 2, though with a less striking decline, in the India-Pakistan conflict the drop in frequency was from 58 percent in the first period (7 of the 12 cases in total) to 42 percent in the second (5 of 12 cases).

47 Moreover, the extent of change in both PCs differs. In the Arab-Israeli conflict there is a sharp decline in the occurrence of interstate crises and a consistent rate of ethnic cases. In the India-Pakistan conflict the interstate dimension remains stable, while the ethnic has somewhat declined. This actually means that though the ethnic element in the Arab-Israeli PC is central and persistent throughout the years, it manifests itself in lower levels of overall magnitude. In the India-Pakistan PC the ethnic and interstate dimensions co-exist preserving and even strengthening the compound nature of the confrontation. Magnitude is not relaxed and the conflict lingers on.

48 The territorial domain in both PCs became most salient in different stages of each conflict. After the partition in Palestine the Arab states refused to accept Israel's right to exist, thereby making the struggle in the first 20 years of the PC a zero-sum confrontation. It was only after the 1967 war that mutual acceptance, though limited and undeclared, reduced the extreme nature of the conflict and made its territorial aspect a matter of mixed motive brinkmanship coupled with negotiations toward compromise between states. From that time, when the West Bank and Gaza came under Israeli rule, both the state and ethnic domains related to territorial issues. Despite major ideological and cultural differences, the India-Pakistan conflict was mainly one over territory. It never included such extreme de-legitimating campaigns as were evident in the Arab-Israeli case.

49 In terms of overall magnitude the Arab-Israeli conflict is slightly higher than the India-Pakistan struggle. While grave threats characterize a larger number of the crises in the South Asian PC, intense violence characterizes crises in the Middle Eastern conflict more often. Non-accommodative outcomes appear in both PCs with similar frequency of 58 percent, and accommodative endings are found in only 42 percent of the crises (see Tables 1 and 2 on outcomes).38 Still, in terms of crisis frequency, the Arab-Israeli PC included more than twice the number of crises than the India-Pakistan PC during the same 56-year period. Hence, the destabilizing element of crises in the Arab-Israeli confrontation is one of many outbreaks of hostility, with a marked decline in the post-1973 period. In the India-Pakistan PC fewer yet more severe outbreaks of hostility persisted in both periods.

50 In more detail, as indicated in Table 1, when magnitude is looked at over time a major difference appears. The overall medium-high magnitude of the Arab-Israeli conflict derives from a high magnitude of the crises that occurred in the 1947-73 years, and from a lower magnitude evident in the 1974-2003 years. Eighty-two percent of the crises in the first period (14 of 17 cases) have a magnitude score of 2 or 3, while only 33 percent of the crises in the second period (3 of 9 cases) belong to the high magnitude score (only 1 of these cases scores 3, the highest overall score in the index). The decline in magnitude appears vividly in the frequency of cases with a 0 magnitude score — the lowest possible score in the index. While in the first period only 1 crisis (of 17 that occurred) had a score of 0, in the second period 5 crises (of 9 cases) had such a minimal score, indicating a salient drop in overall PC magnitude.

51 In the India-Pakistan PC the medium-high magnitude is consistent throughout, with high and low magnitude crises occurring in both periods. As noted in Table 2, in this PC most cases score 2 or 3 (75 percent — 9 crises of the total 12) and there are no crises with a minimal overall magnitude score of 0. Thus, while the conflict in the Middle East saw a major decline in the gravity of threat and violence and a shift to more accommodative outcomes in its second phase, no major changes occurred in the magnitude of the South Asian PC over the years. The interstate-ethnic crises in this PC remained of medium-high magnitude in the second period, while the interstate domain became relatively lower in magnitude.

52 Interestingly, while interstate crises were much more severe than interstate-ethnic crises in the Arab-Israeli PC, such crises were less severe than interstate-ethnic cases in the India-Pakistan PC. That includes the outbreak of wars. In the former most of the wars were interstate. In the latter all three wars were interstate-ethnic.

53 There is also a difference in the nuclear dimension. A nuclear capability was first introduced into the Arab-Israeli PC during the first period of the conflict. Such a capability appeared in the India-Pakistan PC at the beginning of the second period. In the Middle Eastern dispute Israel is still the only nuclear power. Ongoing Arab efforts to overcome Israel's nuclear supremacy have not resulted in an actual counter-capability. In the India-Pakistan conflict the nuclear arms situation is more acute with both sides possessing nuclear weapons. This parity of nuclear capability has increased the danger of a miscalculated nuclear confrontation. It is this reality that makes even the ethnic type crises very dangerous because these confrontations might escalate beyond the nuclear threshold.

54 Another difference is the relative moderation of the two conflicts over time. While most of the Arab-Israeli crises during the second period ended in accommodative outcomes, the opposite has been true of the India-Pakistan PC. Here the extent of accommodation in crisis outcome is in decline, as almost all the crises between 1974 and 2003 ended with neither compromise nor understanding.

55 However, one should remember that the Arab-Israeli PC is far from over. Major issues are still contested, people continue to bleed, and the conflict awaits resolution. But it is perhaps possible that the moderation in the interstate-type confrontation of the Arab-Israeli conflict, despite setbacks and detours, could leave its traces on the ethnic domain so that the entire protracted struggle would gradually begin to wind-down.

CRISES AND PCS: WHAT NEXT?

56 Crises and compound PCs have played a salient role in the twentieth century and are likely to do so in the future. This study has used international crisis, a well-defined and operationalized concept, as a tool to analyze PCs. Two core aspects — their compound nature and overall magnitude — were defined and applied to the Arab-Israeli and India-Pakistan PCs in order to detect similarities and differences.

57 In this study we found that the two measures of compound nature and overall magnitude are necessary and useful in order to describe and analyze PCs over time and regions. Both concepts correspond, though not fully, and therefore more in-depth research involving other PCs should be conducted in order to generalize across regions regarding complexity and the severity of conflicts. These findings improve our knowledge on the character of protracted conflicts and provide us with descriptive measures for the analysis of such occurrences in world politics.

58 Given the importance of the compound nature in delineating PC dynamics, the study pointed to the role of ethnic actors and issues in the confrontation. Ethnic actors are used/manipulated by states to promote their interests, but we also found that they drag states into escalation processes and violence. Stability and order in the interstate domain cannot be detached from events that unfold in the ethnic-state domain. While the outcomes of all crises may vary over time, from agreement to unilateral acts, it is much harder to reach compromise in ethnic-state confrontations than in interstate ones. Therefore, we must be aware that a compound nature, or a primarily ethnic characterization of a conflict, not only prolongs the confrontation but also diminishes the prospects of conflict resolution.

59 Compound conflicts, in which interstate disputes are intertwined with ethnic-state crises, tend to have a higher magnitude, namely they involve higher stakes, higher levels of violence, and lower likelihood of agreement in crisis outcomes. As solving both domains of conflict simultaneously seems to be quite unlikely, conflict resolution in compound conflicts often requires the abatement of one of these domains first. It appears that the interstate domain is more likely to be resolved first and may positively affect the ethnic one later in the PC.

60 The comparison between the two PCs included tangible and intangible factors. Most pronounced among the former is the territorial dimension, which is common to both conflicts. Most noteworthy among the latter is the diversity in beliefs and worldviews among the rivals. Yet, while ethno-national differences are a major factor in the Arab-Israeli PC, ethno-religious differences are more vital in the India-Pakistan protracted hostility.

61 Notwithstanding the importance of territory, nuclear proliferation, and religion as core aspects in PCs, this article seeks to draw attention to ethnic actors and issues as salient aspects in international crises and conflicts, the heart and core of world politics. The fury and outburst of violent attacks against European states by Muslims throughout the world in early February 2006, following the publications of cartoons mocking Islam and the Prophet Mohammad in Western newspapers illustrate the non-tangible stakes of culture and religion embedded in both PCs. This pattern of escalation draws attention to the non-tangible yet meaningful aspects of rivalry that are often overlooked or lay hidden in the deep-rooted belief systems of the contending parties.

62 Regarding the first two research questions, we found that both PCs changed over time, though the Arab-Israeli conflict involved earlier and more changes than did the India-Pakistan one. The substance of change also differed with the Arab-Israeli case becoming less compound, more accommodative, and less severe in overall magnitude. Quite opposite trends are found in the India-Pakistan PC.

63 The last research question focussed on the correspondence between the compound nature and overall magnitude in PCs, and investigated the spillover effects between both attributes. The expectation that a compound nature and high magnitude would coincide was supported by findings from the two regional conflicts, but not to the same degree. The Arab-Israeli conflict was a fully compound PC in the first period and less compound (mainly ethnic) in the second period. These changes were accompanied by corresponding changes in the overall PC magnitude: from medium-high magnitude in the first period to low magnitude in the second. Different dynamics were traced in the India-Pakistan PC, yet they accorded with the logic of correspondence between compound nature and magnitude. This PC changed slightly in both attributes, becoming somewhat less compound over time and barely decreasing in overall magnitude.

64 Evidently not all PCs are alike and if we want to reach a better understanding of conflict escalation and abatement future research should concentrate on the particulars of distinct PCs. Compound nature and magnitude are two of many possible PC attributes. These and other aspects characterizing PCs should be taken into account and integrated into frameworks of analysis, later to be applied to empirical evidence from diverse PCs in world politics.

65 In addition to conclusions related directly to our research questions, some interesting observations emerged regarding the nature of ethnic actors, a core element in our operationalization of ethnicity in crisis and conflict. We found that distinct modes of ethnic actor development were accompanied by unique regulation processes in compound PCs. Active ethnic actors, that are not strong enough to manifest state-like responsibility, seem to be a destabilizing element in both PCs. However, well-organized and supported actors seem to be present when conflict resolution occurs. Ethnic actors in the Arab-Israeli PC began their rise in the 1950s and 1960s and, by the time the conflict entered its second phase, they were consolidated actors. At this stage the interstate dimension began to decline.39 With the emergence of powerful ethnic actors and spillover effects from the interstate to the ethnic domain, the conflict began to slowly wind down. In the India-Pakistan PC, on the other hand, well-known and organized ethnic actors emerged only in the late 1980s, and have not yet achieved the international recognition and support of their counterparts in the Palestinian camp. Moderation, expressed in terms of crisis attributes and lower magnitude, is still not apparent in this PC. It can be expected, then, that once ethnic actors gain power and become meaningful and legitimate actors the India-Pakistan conflict will resemble the Arab-Israeli one. Accommodation and reduced magnitude are then likely to ensue. Alternatively, the demise or fading of ethnic actors in both PCs, along with resolution in the interstate sphere, may also bring these conflicts to an end.

Table 3: An Overview of the Arab-Israeli and India-Pakistan PCs, 1947-2003

Display large image of Table 3

Hemda Ben-Yehuda is a senior lecturer in Political Studies at Bar-Ilan University, Israel, and a research associate of the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) project.

Meriav Mishali-Ram is a lecturer in the Department of Political Studies at Bar-Ilan University, Israel.

ENDNOTES