One Step Forward, One Step Back?:

The Development of Peace-building as Concept and Strategy

Andrea Kathryn TalentinoTulane University

INTRODUCTION

1 Peace-building is now a commonly used term in international relations and an integral part of conflict resolution initiatives from Europe to Africa to Central Asia. It describes the effort to rebuild and reform societies that have been torn by internal conflict, and is aimed at not only providing resolution for existing problems but also creating the conditions that will prevent violence in the future. The term implies promulgation of norms considered central to political and economic development and is therefore touted in both academic and practical discourse as a key component in enhancing international security, reducing the frequency of violence, and advancing agendas for human security. As such, peace-building requires some involvement in local affairs in order to promote changes aimed at creating more effective, stable, and representative governance. That idea does not mesh easily with the notion of sovereignty, however, which gives states the right to be free from external interference. The internal affairs of states are traditionally considered to be exactly that, internal affairs. Yet peace-building is now often heralded as a cornerstone of international efforts to promote stability in both pre- and post-conflict contexts.

2 How and why did peace-building become such a central concept for international relations, particularly when it intrudes on the long-cherished norm of sovereignty? That is an important question to ask because the value of peace-building is now promoted in a variety of contexts, from collapsed states to anti-terrorist programs. Although the literature on peace-building is substantial, most academic attention is devoted to analyzing what it means and how it is best accomplished. By identifying different categories of need (economic, political, and social) as well as different categories of priority (short, medium, and long-term) the existing literature has been helpful in exploring approaches and assessing what strategies are most effective.1 However, it overlooks an equally important issue, how and why peace-building developed into its current form. Humanitarian intervention appeared to have a relatively limited future when peace-building efforts ended with violence and failure in Somalia in 1993. The US demonstrated that it was unwilling to risk casualties to do good, and few other countries had the capability or will to lead interventions. Events in Rwanda just a year later seemed to confirm the demise of the humanitarian idea. Strangely, however, the reverse has happened. Peace-building has become more frequent and its scope much broader. It is now almost a required response to state crisis, with mandates growing more complex even in the absence of obvious rewards or successes for the participants.

3 That is something of a surprise because nations have not historically been persistent in courses of action with high potential costs and low direct or tangible reward. As Patrick Regan points out in the case of intervention in general, states are not likely to act in places with a low expectation of success.2 The fact that peace-building persists nonetheless raises an important question — will the concept survive repeated failure? This article argues that it will, because the development of peace-building is a symptom of a deeper normative change in the international system. For a variety of reasons humanitarian norms, of which intervention and peace-building are a part, have become so entrenched that they have altered the international agenda and placed new responsibilities on states. States are increasingly obligated to engage in peace-building operations, and in a strange twist, failures seem to only increase the demands (to do better) and the expectations (to do more). Now 12 years after Somalia, peace-building is a much more comprehensive notion that includes wide-ranging reforms, close involvement with political development, and often protracted timeframes for implementation. While in some cases the extent of interference in domestic affairs is quite limited, in others it includes taking over the reins of a state and forcing the acceptance of reform. That level of involvement and the consensus behind it represent a breathtaking change in conceptions of domestic sovereignty and international responsibility, and one that occurred over a single decade.

4 This article traces the evolution of peace-building in both the theoretical and practical contexts. The theoretical developments that provided a climate in which peace-building goals could be articulated are discussed in the first section of the article. They include the expansion of security agendas to include "non-traditional" threats and the increased relevance of institutions and norms in the post-Cold War world. The second section analyzes the development of humanitarian intervention as both an idea and a strategy, and the expansion of objectives from restricted and "low-impact" goals to more complex goals requiring involvement in local development. The third section looks at the actual practice of peace-building, tracing the expansion of the term from early efforts in cases like Somalia and Bosnia to the broader and more recent efforts in Kosovo and Afghanistan.

THE THEORETICAL CONTEXT OF PEACE-BUILDING

5 The practical roots of peace-building lie in the UN tradition of peacekeeping, which began in 1956 with the creation of the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF 1) in Egypt. UNEF established the model for UN peacekeeping by operating on the principles of host country consent, impartiality, and resort to arms only in self-defense. The UN hoped simply to create conditions in which negotiation toward peace would be possible. Early peacekeeping operations did not affect the structure of the state in which they occurred and consisted primarily of interpositional forces designed to separate warring parties.3 Only one, the United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC) violated those principles.4 That began to change in 1988 when the UN assisted in developing a settlement on Namibia and preparing it for statehood by establishing electoral procedures and an institutional structure. Boutros-Ghali favored extending that approach to other cases, a point which formed the centerpiece of his 1992 report, An Agenda for Peace. He argued on behalf of rehabilitation through "peace-building," which he specified "must include the promotion of national reconciliation and the re-establishment of effective government."5 He also included peace-making, the attempt to establish peace agreements through coercive or noncoercive means, and peace enforcement, the use of force to ensure adherence to agreements, as important corollaries of peacekeeping.6

6 The philosophical grounding for peace-building came from the expansion of security agendas that developed after the Cold War. Not only did a series of liberal norms find articulation in that climate, but international institutions and law enjoyed a resurgence, providing legitimacy for peace-building initiatives. The development of consensus on the value of human rights, responsible governance, and democratic ideals formed the basis for peace-building's reforms and allowed the implementation of increasingly ambitious agendas in the context of peacekeeping operations. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) played an important role in highlighting humanitarian agendas and the connection between rights-based rule and stability. NGOs operate by forming coalitions of interest around specific issues or goals, which then help "develop new norms by directly pressing governments and business leaders to change policies, and indirectly by altering public perceptions of what governments and firms should be doing."7 The second point may be the most important, because it means that NGOs help establish international agendas by defining what issues are important. Mary Anderson defines four distinct tasks for NGOs in addressing conflict: providing relief; promoting long-term social and economic development; promulgating and monitoring human rights; and promoting negotiation, mediation, and other non-violent approaches to dealing with conflict.8 By focusing on those objectives NGOs helped draw attention to the distinction between ending violence and developing the conditions for sustainable peace. That in turn led to demands that capable states address the consequences of internal conflict, particularly in terms of its humanitarian impact.

7 Accordingly, in the early 1990s UN operations began to evolve into "second generation" missions, including reform and rehabilitation, as explicit goals.9 That led to an increase in the number of peacekeeping operations and an expansion of their mandates to target political and social development as well as security issues. More peacekeeping missions have been authorized since 1992 than in the previous 44 years of the UN's history, and they all incorporate rehabilitative goals.10 Second generation operations did not simply try to stop conflict, but instead began to address its causes by identifying and seeking to change the sources of violence. They therefore fit closely with conflict resolution approaches based on transforming interactions at all levels of society, elite to grassroots, and rationalizing processes of competition among groups.11

8 Mats Berdal calls the introduction of conflict resolution approaches, including monitoring tasks and human rights reforms, "significant innovations in peacekeeping practice."12 UN efforts in Angola, Mozambique, El Salvador, and Cambodia throughout the mid-1990s all exemplified the peace-building extension to peacekeeping, with varying degrees of success. In most of these cases political issues received the most focus, with efforts centered on establishing elections, retraining security services, and creating a basis for accountable governance. But the frequency of internal conflict and state crisis led to a further expansion into multidimensional operations focusing on enforcement and implementation of peace agreements as well as complex programs of civilian rehabilitation.13 This third generation style of peacekeeping operations is distinguished by an emphasis on military force and the potential absence of two prerequisites for all other types of peacekeeping, an accepted peace agreement and/or host country consent to the operation. Coercive peace-making and peace enforcement fit into this category. While early missions of this type focused on the military role in establishing security, later operations have made rehabilitation an equally important goal. Limited reform programs proved insufficient, leading to the development of nation-building mandates with extensive reform programs intended to establish entirely new political and economic structures.

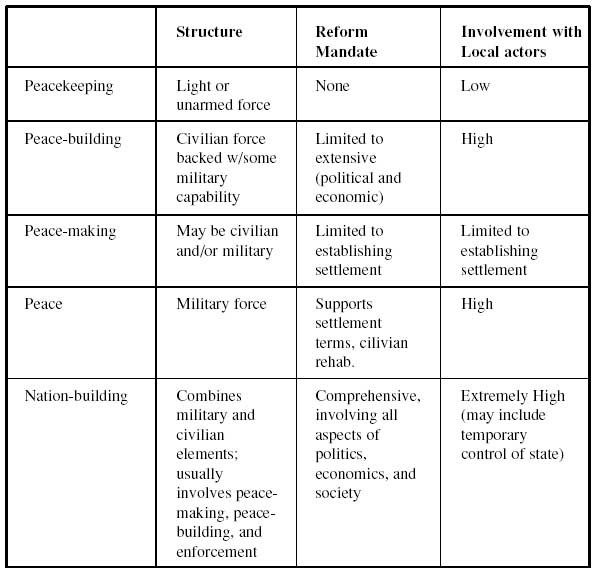

9 Nation-building is a subset of peace-building and describes a contemporary process of state-building carried out by external actors intended to transfer new processes and institutions of government rather than reform existing structures. It is a very specific and aggressive form of peace-building, and is used most frequently in the context of state collapse. It is important to distinguish, however, that while not all peace-building operations involve nation-building, all nation-building operations do involve elements of peace-building. This "full service" approach reflects a normative shift noted by Michael Doyle, Nicholas Wheeler, and others, which opens sovereign matters once exempt from intervention to become legitimate targets of international action.14 The table below outlines the basic distinctions between different terms.

Display large image of Table 1

10 The normative shift that helped provide a philosophical justification for peace-building was itself part of a larger trend affecting the world-globalization. Globalization had a direct impact on the course of intervention and peace-building by shaping important ideas like conflict resolution and human rights, and giving them greater relevance in the post-Cold War world. As Jean-Marie Guehenno argues, "globalization is a process that changes not only the external context within which states operate, but also the very nature of states and political communities. The idea of autonomous human communities, democratically or nondemocratically pursuing their own interests, is put into question."15 The effects of globalization eroded the sanctity of sovereignty and helped alter some important aspects of international relations, including the expectations placed on states. New standards of behavior have developed, or perhaps more accurately, what were once suggestions for state behavior are becoming standards against which the privileges of states are judged. The new standards reinforce the argument that "legitimacy does not stem from material and coercive power alone."16

11 That concept had an important effect on the definition of security. Since the end of World War II understandings of security have been defined by realism, the dominant school of thought in international relations. Realism holds that "security rises and falls with the ability of a nation to deter an attack, or to defeat it."17 Challenges to this view began during the Cold War, as scholars and practitioners questioned the effectiveness of articulating individual interests through the state. Together they argued for a broader concept of security to include non-military issues and greater focus on individuals.18 This trend accelerated after the Cold War as a result of the changes promoted by globalization and the ability of technology to enhance the reach and effect of public and private organizations.19 International events also contributed to the debate. The experiences of states formerly in the Eastern bloc highlighted the inadequacy of security as then understood because the threats they faced, first as socialist nations and then as transitioning ones, were internal rather than external.20

12 As a result, international organizations began to pay increasing attention to the treatment of individuals within states. Boutros-Ghali made emphasis on human security as served by the practice of conflict resolution and rehabilitation a central pillar of his international agenda, a trend reinforced by his successor. That endorsement helped make governmental conduct and legitimacy important matters for international concern because of their links to internal conflict, state collapse, and humanitarian emergencies.21 This attention to internal issues was a "radical departure" from past UN practice, according to Michael Barnett, because it established a "vision of how member states should organize their domestic relations."22 At the same time, humanitarian concerns and standards of governance began to be included in conceptions of security because they were conceived as central to the stability of states. The January 1992 Security Council summit cited problems in the economic, social, humanitarian, and ecological fields as threats to international peace and issues of relevant concern, thereby significantly broadening the definition of security. The organization's Millennium Declaration in 2000 also specifically advocated democracy because of its emphasis on the rule of law and protection for individuals.23

13 These changes plus the circumstances of many contemporary conflicts made a strong case for the importance of peace-building in the early 1990s. As Mohammed Ayoob points out, most of today's conflicts are located in the Third World, where the process of state-making is incomplete.24 Oddly, security now prevails among the most powerful states with the greatest capacity to wreak catastrophic harm. Norms and multilateral cooperation alleviate the security dilemma among these states and render their militaries non-threatening to each other. But security is far less certain among smaller and weaker states, particularly those engaged in efforts to develop and consolidate state power. Many states struggle with establishing legitimacy in the face of societal divisions and, by choice or by accident, have few means of dealing with competition except through force. Ayoob notes that for many states the domestic context is more important than the external one, a fact long recognized in the developing world, where studies on security emphasize sub-state threats by focusing on corruption, civil conflict between national, ethnic, or religious groups and weak structures of government as the primary challenges to states.25 All of these issues became more prominent on an international level as well in the wake of the Cold War. Cases, such as the former Yugoslavia and former Soviet republics, demonstrated that internal consolidation and legitimacy were closely tied to security. Peace-building reflected this new understanding by putting emphasis on increasing the capacity of governments to govern, which was gradually recognized as a crucial task in addressing the challenge of collapsed states.

14 As the meaning of security broadened, traditional interpretations of sovereignty and non-intervention faded. A number of scholars, including Lori Fisler Damrosch and Robert Pastor, justify third party intervention by stressing its connection to human rights and conflict resolution.26 That position implies the importance of peace-building. Damrosch argues that individuals possess rights outside the state to which they belong, and deserve some protection if those rights are abrogated. Other writers have expanded on this theme, suggesting that a state which transgresses certain ethical values in the treatment of its citizens might be devoid of legitimacy and therefore subject to intervention.27 Such arguments coincide with notions that sovereignty needs to be reconsidered in light of internal and transnational crises.28 The International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) concluded that in some circumstances sovereignty may need to yield to humanitarian protection. In defining sovereignty as "the responsibility to protect," it noted that some states do not meet this criteria and could be considered legitimate targets for intervention. Although it drew a careful threshold specifying only extreme cases of ongoing or imminent human rights violations as potential targets, the ICISS also charged capable states with the duty of preventing and responding to failures of sovereignty that put citizens at risk.29 Increasingly, human rights are seen to have a "sovereignty-transcending quality" that justifies efforts to protect them.30

15 Times have changed from the UN's early days, when the secretary-general forwarded complaints about human rights abuses "to the accused government with an accompanying note explaining that such matters were none of his business."31 The contemporary notion of sovereignty has now moved closer to the historical tradition of capability, implying that the sovereign right to be free from interference inheres not only in juridical recognition of statehood, but also, and just as importantly, in the practice of responsible government.32 Terry Karl and Philippe Schmitter view this as part of an emerging liberal consensus, which makes debate on legitimacy and the responsibility of governments to their citizens a central part of the international agenda.33

16 The idea of transforming institutions in target states developed from these arguments. Although early explanations dismissed the grievances that gave rise to internal conflict as deep-seated and atavistic hatreds, more recent scholarship targets weak or exclusionary state structures as the real cause.34 The secret to decreasing conflict, therefore, is to make more legitimate governments. At the same time, experience demonstrated that making peace settlements last was not simply "a matter of technical arrangements."35 Quite to the contrary, peace required complex efforts aimed at building confidence and decreasing sources of distrust, points also reinforced in academic discourse.36 Peace-building therefore replaced peacekeeping as the main thrust of international objectives. Increasingly, theoretical and practical experience argued for extending conflict resolution principles to the post-conflict period and developing strategies for reforming or even rebuilding states. This expanded the notion of resolution from simply trying to stop violence to also attempting to prevent its re-emergence.

17 Although the most visible part of this process is the effort made by external actors, peace-building also has a local dimension. Reforms cannot be successful unless they have a foundation of societal reconciliation and a developing civil society to make them sustainable. Developing local capacities is thus an important though often overlooked part of peace-building. For example, John Paul Lederach cautions that answers for the post-conflict context should not come exclusively from outside the state. Rather, he argues that locals will have their own vision for peace and should be viewed "as resources, not recipients."37 A growing group of academics and practitioners has begun to emphasize the role of civil society and local government, arguing that establishing local capacities through the development of grass-roots level associations is crucial for long-term reconciliation and sustainability.38 These arguments highlight the identity element of nation-building, suggesting that the process of state-making could be undermined without a corresponding effort to overcome some of the divisions afflicting society. While recognizing the need for outside assistance to catalyze state formation, they argue that reconciliation is essential for the state's long-term survival.

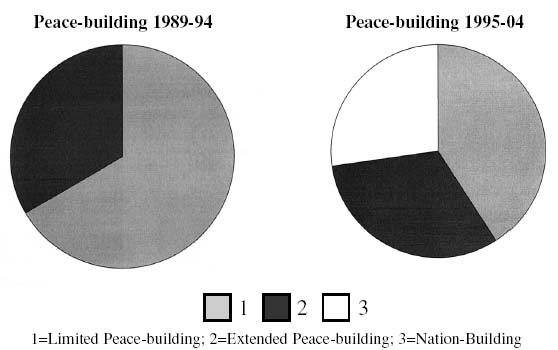

THE PRACTICAL CONTEXT

18 Two separate but entwined processes led to the development of peace-building missions as they are now applied. The first was the expansion of peacekeeping into peace-building operations and the focus on reform strategies as a necessity to address state weakness. The consensus that developed around the importance of reform and rehabilitation catalyzed that expansion and led to the shift toward second and third generation style missions. The second process was the expansion of the peace-building idea itself from the notion of an operation with limited impact on the political structure of the target state to the implementation of high impact missions that become directly involved with state development and in some cases even take over state responsibility. The most extensive and comprehensive cases are usually associated with military operations engaged in peace enforcement, and move peace-building one step further into the nation-building category.

19 While the first process changed as a result of developing ideas, the second process changed largely as a result of practical experience. On a theoretical level, academic discourse began to emphasize the complex temporal nature of resolution efforts and the importance of reform. On a practical level, experience increasingly demonstrated that limited approaches that sought to avoid or restrict involvement with state structures could not achieve those goals. The results of early peace-building missions, which focused on aiding victims, showed that long-term success was not likely unless a more concerted effort was made to entrench those protections in more rationalized and stable structures of governance.

20 Fen Hampson divides external intervention into three categories: realist, governance-based, and social-psychological.39 The realist category ranges from "hard" approaches, which advocate limited security involvement and no peace-building tasks, to "soft" approaches, which employ a variety of policy options in order to build support for a peace settlement. The governance and social-psychological approaches, by contrast, advocate much more comprehensive strategies aimed at creating new norms to shape both institutional procedures and individual attitudes in order to attain longer-term reconciliation. Peace-building started in the soft realism camp, but has now traveled much closer to the governance and social-psychological end of the continuum. While early approaches were quite tentative and characterized by an emphasis on bringing parties to the negotiating table, peace-building operations now more often emphasize the implementation and maintenance of peace, with comprehensive reform programs designed to alter both public and private interactions.

21 This trend is reflected in the development of UN peacekeeping operations since 1989. Thirty-six operations were authorized in that time.40 They can be separated into three rough categories distinguished by the scope of the reform effort: Limited Peace-building, Extended Peace-building, and Nation-Building. Each represents a specific point along the peace-building continuum, from a restricted and relatively hands-off style to an area-specific approach reform program with limited objectives to a broad approach with quite ambitious objectives. The first corresponds most closely to Hampson's soft realist category, while the latter two focus more on governance, with attention to social relations. The categories are roughly defined as follows:

- Limited Peace-building

- no enforcement powers,

- main emphasis on humanitarian protection/assistance,

- follows accepted peace agreement,

- monitors and verifies cease-fire,

- provides technical assistance, and

- oversees demobilization and disarmament where appropriate.

- Extensive Peace-building

- may have limited enforcement,

- usually follows accepted peace agreement,

- chooses selected reform targets,

- has some involvement in establishing political process (usually electoral), and

- focuses on improving/retraining security services.

- Nation-Building

- has full enforcement powers (though often carried out by another organization),

- may precede peace agreement,

- pursues comprehensive reform program,

- creates new political-economic institutions and processes,

- targets reintegration of combatants as part of reform,

- may have oversight and some control over local policy-making, and

- may assume temporary control of the state.

22 It must be acknowledged that these are crude categories. Overlaps often exists, with operations sometimes changing their objectives to respond to circumstances on the ground or experiencing temporary expansions and retractions as conflicts ebb and flow. Furthermore, as noted above, the three groups are not entirely separate entities but exist on a single continuum of broad operations, so that cases in one category may bleed into another. Participants could interpret their role broadly, by facilitating reform in a Limited Peace-building case, or restrictively, by choosing not to pursue intended objectives in Extended or Nation-Building cases, thereby somewhat changing the terms of the mandate. Few operations are perfect representatives of their type. The purpose of the categories is to capture the relationship between the different kinds of operations and illustrate the expanding objectives that came to be associated with peace-building. They do not, however, indicate greater effectiveness or success.

23 As the graphs below show, the first half of the 1990s was dominated by Limited Peace-building, the strategy used in well over half of the countries targeted for assistance. Since 1995, the focus has changed, with the continued development of Extended Peace-building and the introduction of comprehensive Nation-Building programs giving international actors a choice among three strategies. Although Limited Peace-building remains the most frequently used single approach, the focus of effort has switched so that the other two categories now account for over half of the operations initiated since 1995. Efforts to change structures of government are, therefore, now a central part of peace-building.

24 It is important to remember that these categories represent the expanding scope of peace-building over time, but do not necessarily suggest more effective implementation. A lack of agreement on what should be done first or how needs are prioritized is one of the biggest weaknesses of peace-building across all categories, and may at least in part account for the trend toward broader missions. Short and long-term objectives are often mixed in the peace-building toolbox, impeding the attempt to outline clear strategies. Peace-building is intended to prevent a relapse into war and to create a self-sustaining peace, yet there are few clear guidelines for how to make that happen. The UN emphasizes the need to "strengthen governance institutions" as a primary objective, but the task is so broad as to be ineffective in helping to craft approaches and could cover both Limited and Extended operations.41 The only strong area of consensus is the need for security.42 Without efforts to reduce violence and impose costs on its use, few other reforms can proceed. From there the priorities of peace-building vacillate between addressing the most basic needs, like demobilization, to the far more complex processes of reintegration, democratization, electoral process, economic reconstruction, and regulatory issues. Since it was unclear which changes mattered most, international actors began to apply the blanket approach, hoping to thereby cover all the important issues. Comprehensive missions address the problem in theory if not necessarily in practice by focusing on the extent of the change rather than the quality of the implementation.

Display large image of Figure 1

25 As a result, peace-building in its most ambitious forms often sacrifices quality for quantity. The depth of reforms is most often shallow at best, a casualty of both divided international attention and limited time and money. The International Crisis Group (ICG) has bemoaned this fact in analyzing peace-building efforts from Africa to Europe and advocated greater commitment to reform programs, to little avail.43 International commitment is a crucial ingredient because it determines the extent of the resources applied and the will behind them. Far too often the participants in peace-building are committed to doing something, but balk at doing enough, largely because these conflicts tend to take place at a geographic distance and have little direct impact on them. Although in some sense peace-building may be a noble concept, as Michael Mandelbaum notes, it is also often half-hearted precisely because it is noble, with few connections to national interest.44 There are some exceptions, but even those places that have direct security connections, such as Afghanistan for the US, have not seen the depth of effort necessary for sustainable and comprehensive change.45 Thus far, therefore, the scope of reforms provides a better means of distinguishing between types of operations than the extent of their entrenchment.

26 It should be noted, however, that the impediments to reform are not always external. Local actors also play an important role in determining the extent and sustainability of reform. Peace-building operations do not take place in a vacuum, but are in part defined by and dependent on the context in which they operate. The commitment of local actors to implement and enforce reforms, as well as their willingness to give up positions of privilege and prosperity that may have been enabled by the old system, are central to the success of peace-building. The nation-building operation in Sierra Leone is a case in point. Unlike many other cases, there international actors have committed enormous amounts of effort and money to rebuilding the country and have worked hard to entrench reform. They have been stymied, however, by the intransigence of local officials who have vested interests in retaining wartime political and economic arrangements and have not demonstrated real commitment to reform.46 The success of peace-building cannot be judged solely on an international basis, therefore, but should also take into account the local perspectives and agendas that shape how rehabilitation proceeds. The following section looks at some of the challenges of implementation.

THE PRACTICE OF PEACE-BUILDING

Limited Mandates (top)

27 Limited Peace-building comprises the most hands-off category and focuses on efforts to maintain the technical aspects of peace agreements without getting directly involved in the process of state development. Two different groups of cases fall within this category. One group consists of cases where the intervention functioned on a limited mandate emphasizing humanitarian aid and ceasefire monitoring without actually changing or shaping the structure of the state. International actors may have engaged in non-coercive peace-making, such as good offices and mediation, but did little to change the incentives or disincentives for reconciliation. The other group consists of cases where the mandate was inappropriate for the challenge faced and therefore largely ineffective. These cases rarely progressed to the actual peace-building phase because of problems in establishing a secure environment for peace negotiations and reform programs. They are one reason why coercive peace-making and peace enforcement became more common partners of peace-building. The restricted nature of this category was shaped by an early reluctance to pursue aggressive resolution efforts coupled with concern for violating sovereignty. International actors viewed intervention in its traditional form as something of a taboo, and rather purposely sought to have limited impact on the state itself. Humanitarian and conflict resolution interests were only beginning to emerge as international norms in the early 1990s, and the demands on states were relatively few. That foundation for action would change significantly and provide the basis for more extensive reform.

28 The most ideal-type case in this group was also the catalyst for the practice of peace-building itself, the United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) in Namibia in 1989. UNTAG was primarily a political organization charged with developing an electoral process. It assumed traditional peacekeeping duties, such as monitoring the ceasefire and removal of South African forces, but also added a political objective by assuming responsibility for establishing free and fair elections. The mandate contained two elements, a military component and a civil component.47 Peace-building activities in this case consisted of providing oversight for the civilian police, and preparing and then holding the election. The primary goal was to create a mechanism for choosing national representatives who would then be responsible for further development of the state. UNTAG scaled down its operations after elections were held successfully, and closed all its offices on the day Namibia officially became independent.48

29 UNTAG's mandate, as specified in the authorizing resolution, was to ensure conditions that would allow people to "participate freely and without intimidation in the electoral process."49 That entailed both establishing and monitoring elections, but did not imply further reform or enforcement. The UN assumed that once elected the new government would be competent to chart Namibia's future, and in this case that assumption held. Though extremely limited, UNTAG provided a glimpse into the potential role of the UN in developing the conditions for peace. Most importantly, it provided the foundation for arguments that more was required to end conflict than simply keeping forces apart. The elections proved successful, and demonstrated that peace-building activities could alter the structure of conflicts by introducing neutral facilitators and providing oversight of the transition process.

30 UNTAG's success may have been a bit misleading, however, in that it was implemented in a cooperative environment where the relevant parties expressed a commitment to the peace settlement. Those circumstances were not present in many other places, where the persistence of violence, lack of local cooperation, and absence of viable state structures confronted limited operations with challenges they could not solve. In places like Angola (1989-94), Somalia (1992-94), and Bosnia (1992-95), the collapse of institutions and the presence of extreme divisions in society obstructed the creation of a viable peace process. Peacebuilders armed with too few weapons and backed by too much optimism impressed no one. These were active war zones, and the UN's attempt to insert good faith observers and facilitators backfired badly because they had no capacity to protect themselves much less decrease hostilities.50 As Stephen Cimbala notes, "the assumption that disputant parties are ready to stop fighting was insufficient as a mechanism for conflict termination in Bosnia. The UN forces were a lucrative target for angry sharpshooters not yet disarmed."51 Without a foundation of security, other programs could not proceed. Furthermore, the lack of an institutional capacity for implementing reform or developing agreement on the structures of the state meant that external actors could not bring opponents together for elections and expect government to result. Experience in such cases suggested that in some circumstances the effort to build peace would have to be driven from outside the state, at least for the short-term, and might need to involve state development.

31 The experience with limited peace-building, therefore, set a contradictory precedent. On the one hand, it demonstrated that in the right conditions, limited mandates were successful. UN observers successfully monitored a ceasefire in Tajikistan (1994-2000) while supporting mediation that eventually led to a peace agreement. Similarly, in the Central African Republic (1998-2000) the UN oversaw the disarmament process and provided advice and technical support for the legislative and presidential elections. On the other hand, it led to the na•ve assumption that the conditions would be right, that is, that the local actors would want peace and be capable of pursuing it. But developing experience and scholarship suggested that was not always the case. As scholars, such as David Keen and William Reno, have argued violence is not always a breakdown of society, but rather a form of economic entrepreneurship in circumstances of divided authority.>52 In many cases local actors may wish to prolong rather than end war because they benefit from the political economy that emerges. The complete collapse of state structures is often a result of widespread conflict, leaving no institutional capacity for reform and transferring legitimacy to societal groups. Vacuums of authority allow individuals to develop their own constituencies, separate from central rule, and make them resistant to change. The war in Bosnia is often credited for creating fiefdoms that proved very hard to dismantle, and that has held true in other cases as well.53

32 As these challenges became more widely recognized international actors became more open to developing broader programs of reform. Three factors fueled this expansion. NGOs had an important effect because they advocated greater effort on behalf of conflict resolution and served as an international conscience of sorts in both evaluating and promoting strategies of reform.54 The ICG was and is one of the leading voices in this regard, although such organizations as Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, and development NGOS also play a role. By articulating problems and potential solutions they helped shape a conflict resolution agenda that made more extensive intervention both legitimate and imperative. Practical experience, particularly notable failures, also had an effect. Demands for more and better responses only became louder when things went badly, as cases like Bosnia and Somalia demonstrated. International actors increasingly found that they could not avoid responsibility.

33 Although in past eras failure might have led to retrenchment, especially in cases that did not threaten national security, expectations began to change, dragging states reluctantly along.55 In this case too, NGOs and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) were influential in shaping agendas of expectation and insisting on intervention as an international interest.

34 Finally, the changing definitions of sovereignty, as discussed earlier, helped shape new perspectives. The convergence of state based and individual based security agendas led to the increasing articulation of the claim that sovereignty might be more porous than often thought. Although this remained an uncomfortable position for many states (and does still) the emerging norm of humanitarian intervention led to more discussion of what intervention might actually accomplish and eroded the obstacle that sovereignty posed.56 All three of these factors helped drive the development of extended peace-building mandates.

Extended Peace-building (top)

35 In spite of the lessons of experience, the expansion of mandates did not come after careful evaluation of approaches and challenges at the policy level. Security Council members did not discuss the lessons of previous operations before establishing new objectives. Instead, the development of peace-building approaches was compressed so that expansion began without any real assessment of past operations. UN members knew that many past operations had not worked, but they did not know how or why, and those questions received scant attention in the rush to develop new approaches. Indeed, in the early 1990s the sheer number of crises and the speed with which theoretical perspectives changed left little time for contemplation. Circumstances more than desire moved peace-building to more complex tasks, making extended operations an ad hoc response to the crises of the day. Although international actors began to target specific areas for reform, they still conceived of their task in a relatively limited way. They did not want to create wholesale change, but merely hoped to tinker with existing structures to make them more accountable and transparent.

36 Both Cambodia and Haiti presented cases where international actors saw an opportunity and need to institute significant reform. Haiti had undergone its first democratic election but had no tradition of democracy. Its institutions were weak and easily circumvented, as demonstrated by the coup that overthrew the elected president after seven months and installed a military junta. Cambodia likewise had a decidedly undemocratic tradition and a long legacy of civil war, but was in a transition to a new government as a result of international peace initiatives. The UN had been instrumental in the changes in both cases, helping to broker the peace accords ending the civil war in Cambodia, and overseeing and guaranteeing the election in Haiti. The United Nations Transition Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC, 1992-93) and United Nations Mission in Haiti (UNMIH, 1993-96) were authorized after peace agreements had been established in both cases and were geared toward consolidating positive developments by instituting programs of reform.57 Both sought to change the political processes that were perceived to contribute most to cultures of violence and repression. In each case the mandates identified specific areas that would be subject to international reform and gave the UN general responsibility for maintaining progress toward peace.58 Cambodia's case was more complex since it entailed taking over some aspects of civil administration while the new government was created and a constitution developed.59 By taking on that mandate the UN expanded the concept of peace-building quite significantly. Although international personnel viewed themselves more as facilitators than reformers, UNTAC's involvement with the national administration reflected an emerging willingness to engage political issues. Peace-building operations would increasingly include this approach to some degree, beginning a focus on trying to change the conditions that caused violence rather than simply trying to lessen its effects. Similar approaches were implemented in Mozambique and El Salvador around the same time, and moved peace-building into the process of shaping political development.

37 However, the UN also sought to lessen that involvement by providing a strict timeline for UNTAC and limiting its ability to enforce compliance with the terms of the peace agreement. Extended peace-building operations implement reform mandates but usually have limited authority to use force except in self-defense. Local parties knew they could defect without risk, and in Cambodia violence and a lack of cooperation effectively reduced UNTAC's multifunctional mandate to the single task of conducting the election. No costs were associated with obstructionism. UNTAC was not authorized to change its military or civil approach even after the Khmer Rouge defected from the peace process, nor could it strong arm the sitting government, the State of Cambodia (SOC), which was in a position to block the implementation of reform.60 Lacking coercive power, diplomatic or military, UNTAC could not achieve most of its objectives and, like other operations before it, became subject to the will of local actors. Although often considered a success for holding elections and repatriating refugees, UNTAC's progress in those areas was heavily qualified by the fact that violence continued for several years and few political reforms took hold.61

38 Similarly, Haiti ran into problems with both international and local commitment to reform. The UN identified the police and judicial system as the country's Achilles heels, and sought to decrease government discretion and increase its accountability by professionalizing the army and creating a separate police force.62 Both areas represented significant challenges. The police and military were closely intertwined, in spite of constitutional provisions to the contrary, and both had connections to the infamous tons tons macoutes paramilitary groups. The judicial system was also under the thumb of the security services, with little room for independent action and high levels of corruption. The problems were largely structural, however, and rooted in the Haitian political system rather than simply poor security forces. By the UN's own account, "the early deployment of a permanent and effective police force by the Haitian authorities was considered central to Haiti's long-term stability."63 UNMIH established an interim force as well as a training academy and the relevant programs for developing a permanent force. But those reforms did not lead to the consolidation of democracy and the strengthening of state institutions, nor in the long-run did they lead to a better police force.

39 Although some short-term gains in police quality were achieved, they were grafted onto an unsound political system rooted in corruption and personal dominance. "Democracy," to the extent it existed, was embodied by President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who had created a cult of personality or "one-manism" not so different from Haiti's past rulers.64 Furthermore, Haiti's long legacy of a politicized military made it essential to reshape the role of the armed services in society and integrate the police into a larger "framework for the protection of human rights."65 But attempts to retrain the judiciary proved difficult and were left largely to the local authorities. No attempts were made to address the more general weaknesses of the political system, leaving Haiti with illusory reforms that left little impact. Within a few years the political system degenerated into a standoff between the legislature and president, and increasing violence led to a second multinational force and follow-on UN operation in 2004.

40 A failure to understand the scope of the challenge affected international actors in all these cases. When the Security Council spoke about establishing democracy in Haiti it focused primarily on restoring the elected government of Aristide. That was certainly an important step, but hardly the measure of demo-cracy. Nor did emphasizing the value of the ballot, as in Cambodia, constitute significant reform. Haiti had no real separation between its institutions of state and no solid basis for a political culture on which democracy could be established. Cambodia likewise had no tradition of civil society, no culture of cooperation, and a still percolating civil war. The tasks were much harder, therefore, and the problems much deeper, than most members of the international community anticipated, something reflected in Security Council debates.66 As a result, reform programs were poorly tailored to the situation and the time frame for accomplishing the objectives was far too short. Both operations had mandates of two years or less, and in hindsight it is clear that reforms can rarely be consolidated in that time.67 Longer time frames do not guarantee success, but they do increase its potential, and will be discussed in the next section.

41 Although there were some relative successes, as in El Salvador and Mozambique, in most cases the international community was not willing to accept the extent of involvement necessary. Costs and resources played a role — with numerous crises requiring numerous commitments, member states were reluctant to commit much to any one place. But understanding of the problems and commitment to solving them were also at issue. In Cambodia the UN focused on elections as the key element; in Haiti it emphasized the police and judicial systems. In both cases the other institutions of government were too weak to allow those reforms to be effective and in Cambodia security was not fully established. UN member states did not extend reforms far enough and tried to ignore rather than confront obstacles to the peace process. In spite of the ambivalence, however, and again without clear success, peace-building became more entrenched as an international norm rather than less, driven by the same three factors noted above.

Nation-building (top)

42 1995 proved to be a watershed year for international conceptions of and approaches to peace-building. Earlier efforts demonstrated that, in many cases, grafting reforms onto existing structures was likely to have only temporary effects. Changes needed to be broader and more fundamental. In some ways more extensive involvement emerged as the best of the bad choices as international actors began to appreciate the extraordinary nature of the challenge. Bosnia first demonstrated this lesson, with states and organizations alike discovering that international expectations had changed; they could not extricate themselves from dealing with states afflicted by internal chaos even if they did not know what to do.68 As Steven Burg and Paul Shoup point out, "the international community faced difficult questions of both principle and policy in dealing with the Bosnian crisis . . . while international actors could not easily resolve the Bosnian conflict, they could not remain entirely aloof from it."69 The task of rebuilding Bosnia changed the face of intervention, expanding reform efforts into the realm of nation-building. Rather than trying to improve existing structures, international actors worked to establish new political and economic institutions based on consensus, inclusion, and accountability. Rather than trying to avoid or limit political involvement, the international community placed itself squarely in the middle of defining and developing Bosnia's future.

43 The final structure of the intervention, as it began in 1995 and has evolved since, was significantly more comprehensive than any that preceded it. The intervention embraced the full array of normative rehabilitation programs — political, economic, social — for the first time. Importantly, this change came about from necessity rather than desire. Other approaches had failed, and Bosnia was seen to represent a choice for the future of international relations as a whole. Security Council members ceased viewing internal conflict as a limited issue and instead linked its effects to overall security.70 Conflict resolution became cast as a responsibility. The collective sense that failure in this case would undercut global efforts to promote security and promote a world of "war and destruction" is quite significant.71 In essence, Bosnia became a turning point for the relevance of norms and conceptions of security. In previous cases international actors had stressed the unique characteristics and, in the case of Haiti, offered only a limited precedent in regards to defending democracy.72 Bosnia was different, and was explicitly viewed as a precedent in the sense that the Security Council defined a new and different task for itself and Member States, and one considered to have far-reaching relevance beyond Bosnia.

44 This growing sense of responsibility was bolstered by changing views of the conflict itself. Though initially outside actors considered Bosnia a case of interstate war, fomented by Serbia, over time they came to understand that conflict stemmed from a more fundamental disagreement over the nature of the Bosnian state itself. Negotiations held little interest for the internal parties, who believed they were fighting for their very survival and were reluctant to compromise.73 Bosnia therefore changed perceptions of civil conflict and reinforced the role of multilateral conflict resolution because no state or organization wanted to be "left holding the bag" alone, there or elsewhere.74

45 The General Framework Agreement for Peace, brokered at Dayton in 1995, contained 11 annexes. Annex 1A and B dealt with the military aspects of the peace agreement and regional stability, while Annex 2 addressed the separation of the belligerent groups and the ethnic entities. The remaining eight annexes addressed civilian reconstruction, ranging from the national constitution to refugees to the police.75 International actors had to help build a functioning government, restart the economy, provide services of every kind, and untangle the social problems created by displacement and emigration. Their tasks included everything from training police to developing political parties to passing national law to developing civil society, media freedoms, and economic regulations. But the high levels of distrust made reconstruction difficult. Annex 4, the nation's constitution, established entirely new institutions of government based on principles of cooperation and consensus that were extremely hard to create after four years of war. Officials who have served in Bosnia admit that they were completely unprepared for the task. When they arrived they had few clear plans and only limited appreciation of the problems. As a result, they say, the international community spent 1996 figuring out what to do, 1997 figuring out how to do it, and only began implementing programs in 1998.76

46 This heavy-duty approach was extended even further in Kosovo, where the UN effectively became the state. When the air war against Serbia ended on 10 June 1999, the UN found itself in a new position. Created as an organization dedicated to reducing international war, it was now assuming control of a state to prevent internal war. Security Council Resolution 1244, passed that same day, established a governing charter for the province with a civil administration run by the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) and an international security presence, the Kosovo Force (KFOR), fielded by NATO. Although intervention had grown progressively more comprehensive over the previous decade, UNMIK raised the bar higher still. It established a protectorate over Kosovo, with the UN taking on the authority and power of the state.77 Importantly, however, this operation began just over a year after the beginning of reform in Bosnia, which did not allow much time for evaluation or careful comparison of strategies. UNMIK did integrate its military and civilian operations more effectively, thus learning one early lesson from Bosnia, but stumbled in its actual implementation of reform. Its failure to lessen the ethnic divide, particularly its inability to bring the Serb population into the political process effectively, helped enable ongoing violence and impeded the progress of political development. That in turn feeds dissatisfaction over the balance between international control and local sovereignty, making UNMIK's ability to spearhead reform even more difficult.78

THE MEASURE OF SUCCESS

47 The preceding sections showed how peace-building first developed and then expanded, incorporating more principles of conflict resolution and taking on broader mandates along the way. Although experience may have suggested that was a necessary development, peace-building operations still struggle to achieve success. In some sense international approaches have improved over time. Short time frames are seen less frequently, as a result of learning the difficulties inherent in achieving rehabilitation goals. Time in itself is not a determinant of success, as five years of limited or stalled progress in Kosovo demonstrate. Nonetheless, longer operations do open the possibility that reforms can be entrenched and consolidated and some obstacles eliminated. One of the biggest problems inherent in strict and limited time frames is the incentive provided to spoilers. Groups or individuals who may want to obstruct reforms know they can wait out whatever programs are implemented and then resume their customary activities. Open-ended efforts have gone some way to address this problem by creating an extended international presence and involvement, although that also risks backlash as local sovereignty and international preferences conflict. Bosnia is far from a great success, at least so far, but it does demonstrate that protracted involvement provides the opportunity to address the spoiler problem and can lead to positive reforms.79

48 States and organizations have also become more aware of the complexity of nation-building, a fact explicitly noted when the protectorate operation was authorized for East Timor in 2000. Security Council discussions continually emphasized the need to address all sectors of politics and society, a marked change from the previous interest in avoiding involvement.80 Yet solid success, if measured in terms of state stability and international withdrawal, remains an elusive goal. East Timor may be the best example to date, but in most other cases reforms are fragile, obstructionism remains high, rule of law is spotty, and citizens feel little connection to the fledgling state.81 Strangely, however, that has not changed the overall commitment to peace-building, which has grown stronger rather than weaker in spite of outcomes. The lack of success will not lessen the demand for peace and nation-building as an international strategy because the humanitarian agenda has become too entrenched within the system. In fact, expectations increase with every new crisis, as Darfur demonstrates, bringing new actors into the peace-building effort and further entrenching it within the international agenda. Intervention has become something of a responsibility, in spite of its flaws, a trend supported by the position of NGOs, IGOs, and increasingly, citizens in collapsing states. As Francis Fukuyama writes of nation-building, "We have been in denial about it . . . but we'd better get used to it, and learn how to do it."82

49 It is important, therefore, to adopt a more realistic understanding of success and failure. Minxin Pei and Sara Kasper measure success on whether democracy exists 10 years after nation-building ends. Bosnia is the closest to that benchmark and is not likely to pass. Most of the other examples still have a few years but, similarly, would need to demonstrate a higher rate of change than they have thus far. Roland Paris likewise uses the establishment of liberal government as his measurement.83 Neither of these standards is a useful benchmark, however, because they prevent evaluation of peace and nation-building as a process. Both measurements assume absolute status as the only marker of success while disregarding progress along the path of transformation.

50 Stephen Stedman cautions that setting standards too high prevents differentiation between objectives, arguing, "it is not that attaining good things like economic growth, equitable development, and good governance should not be striven for; it is that they form a useless standard for evaluating implementation actions that take place in a short period of time."84 More importantly, perhaps, it is dangerous to assume that success and failure are contending poles, or as Marieke Kleiboer writes of mediation, that "a success is a nonfailure and vice versa."85 In peace-building, as with conflict resolution in general, success and failure are not clear opposites. A single case may include examples of both, as does Bosnia, where the success in ending war, returning refugees, and building state structures was tempered by the failure to remove ethnic identification from politics, lessen political control of the economy, and increase the power of the central state. Comparing contemporary efforts to those of the past lends some important perspective. Historically, the process of state-building took centuries, not decades, and in the past the main actors could use tactics of force and repression that are now prohibited by international norms.86 That is not to gloss over the very real problems confronting peace-building, but simply to demonstrate the extensive nature of the enterprise. Short-term judgments may not tell the whole story. Progress rather than success may be the best means of evaluation, since it emphasizes movement toward criteria of change rather than ultimate status as the relevant measure.

51 Repairing fractured societies is extremely difficult under the best of circumstances, and is likely to take decades rather than years.87 In many cases reforms are shallow and easily halted once international attention eases. Electoral victory does not equate with governing capacity, and some reforming states are entirely dependent on the international presence. Developing strategies to entrench commitment to norms emphasizing reform and reconciliation has proven to be difficult. Although international actors can create institutions, they have not yet developed ways to get local actors to commit to sustaining them. This is the challenge that peace and nation-building still struggle to overcome. Organizations and institutions have what Fukuyama describes as medium to high degrees of "transferability," meaning that new structures can be imported and developed relatively effectively.88 But ideas and cultural values have very little transferability, so those new structures will rest upon old ideas and habits, leaving them prone to compromise or collapse unless those underlying belief systems can be changed. An emerging lesson argues that pursuing bottom-up approaches to inculcate commitment to reform at the local level and give citizens a feeling of ownership is just as important as the top down strategies of institutional development usually employed by international actors. But commitment is also a problem, as noted, and like transferability, is not likely to change significantly. Arguing that international actors should care or do more is an irrelevant point; the challenge ahead requires learning how to do more with less than enough.

Andrea Kathryn Talentino is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Tulane University.APPENDIX: List of Operations

Limited Peace-building

- United Nations Angola Verification Mission (UNAVEM I), 1989

- United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG), 1989

- United Nations Angola Verification Mission (UNAVEM II), 1991

- United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO), 1991

- United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM I), 1992

- United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR), 1992

- United Nations Observer Mission in Liberia (UNOMIL), 1993

- United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia (UNOMIG), 1993

- United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR), 1993

- United Nations Mission of Observers in Tajikistan (UNMOT), 1994

- United Nations Mission in Croatia (UNCROA), 1995

- United Nations Support Mission in Haiti (UNSMIH), 1996

- United Nations Civilian Police Mission in Haiti (MIPONUH), 1997

- United Nations Observer Mission in Angola (MONUA), 1997

- United Nations Verification Mission in Guatemala (MINUGUA), 1997

- United Nations Civilian Police Support Group (UNPSG), 1998

- United Nations Observer Mission in Sierra Leone (UNOMSIL), 1998

- United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC), 1999

- United Nations Mission of Support in East Timor (UNMISET), 2002

- United Nations Mission in El Salvador (ONUSAL), 1991

- United Nations Mission in Mozambique (ONUMOZ), 1992

- United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), 1992

- United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM II), 1993

- United Nations Mission in Haiti (UNMIH), 1993

- United Nations Angola Verification Mission (UNAVEM III), 1995

- United Nations Transitional Authority in Eastern Slavonia (UNTAES), 1996

- United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic (MINURCA), 1998

- United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC), 2000

- United Nations Operation in Cote d'Ivoire (UNOCI), 2004

- United Nations Operation in Burundi (ONUB), 2004

- United Nations Mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina (UNMIBH), 1996

- United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), 1999

- United Nations Assistance Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL), 1999

- United Nations Transition Assistance in East Timor (UNTAET), 1999

- United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), 2002

- United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), 2004

Endnotes