The Lair and Layers of al-Aqsa Uprising Terror:

Some Preliminary Empirical Findings*

Richard J. ChasdiWayne State University

INTRODUCTION

1 It is commonplace among analysts of the Israeli-Palestinian-Arab conflict to note that the al-Aqsa Intifada represents perhaps the most profound and lasting period of psychological threat and dismay for Israelis and Palestinians since the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. Seen from the vantage of counter-terrorism, the al-Aqsa Intifada puts singular focus on the strains and tensions associated with what some describe as the "delicate balance" between counter-terrorism policy and democracy.1 The purpose of this article is to compare and contrast forms of terrorism in the al-Aqsa Intifada with Middle East terrorism that has come before, by means of a framework of terrorism I developed in previous work. Why is empirical study of al-Aqsa Intifada terror considered important? At a substantive level, the al-Aqsa Intifada, with its array of non-state actors, such as the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), Hamas, and Islamic Jihad, that are in fierce competition with Israel and with each other, not only showcases the importance of non-state actors in the contemporary world, but illuminates what the rudiments of this conflict are all about.2 At a more functional level, the bloodletting in this second round of Palestinian efforts to "shake off" Israeli control has been more copious than that of the first Intifada (1987-93), and that makes empirical investigation imperative.3

2 In this study, "al-Aqsa Intifada terrorism" encompasses terrorist assaults conducted by both Palestinian terrorist groups and Israeli settlers, and "lone assailants" on each side that was kindled by the "activating event" of Minister of Knesset (MK) Ariel Sharon's visit to the Temple Mount or Haram al-Sharif, as it is also known, on 28 September 2000.4 At the same time, what Azim Bishara calls the "October events" by Israeli-Arabs, committed within the context of the fledgling Intifada, are also included in the data base.5 The time frame of this study spans the 17-month period from the beginning of the al-Aqsa Intifada on 28 September 2000 to the end of February 2002, which marks the tail end to an important phase of the conflict. OPERATION DEFENSIVE SHIELD, an enormous Israeli counter-terrorism offensive into areas under the aegis of the PNA, began a month later on 29 March 2002.6 Analysis of nearly the first year and a half of the uprising makes it possible to discern patterns among a host of terrorist assault "attributes," including target-type and location, and to determine the nature of terrorist groups active from the start, in contrast to the type of terrorist groups that have become more active with the passage of time. For the most part, those data findings will be presented within the context of theoretical conceptualizations and prior research findings on terrorist assaults conducted by Middle East terrorist groups and non-group actors.7

3 The implications of those findings are profound and lasting, and at times dramatic. One finding that is diametrically opposite to the common wisdom of this fierce struggle is that the single largest cluster of terrorist assaults that is attributable belongs to Israeli-Jewish settler terrorism and not to Palestinian terrorism. Hence, a fundamental matter from a public policy point of view really boils down to an appraisal of the relative anonymity of what is presumably a significant portion of Palestinian terrorism. It is equally important to acknowledge the scope and depth of Jewish settler-type violence in a political atmosphere in the Occupied Territories that is relatively permissive in terms of brandishing weapons, using other acts of intimidation, and the threat and use of force. The framework for discussion involves: the theoretical framework and operational definition of terrorism used; analysis of some general empirical contours of al-Aqsa Intifada terrorism according to target selection; types of terrorist groups predominant in early and latter time periods; and political/security ramifications.

Theoretical Framework and Definition of Terrorism

4 One of the underlying themes of this work is that terrorist group chieftains or tacticians are rational decision-makers. As Jorge Nef tells us, rationality can be demonstrated ". . . if by rational we assume an instrumental relationship between ends and means."8 In other words, it is assumed that rationality holds for terrorist group chieftains and tacticians as it does for their counterparts, governmental leaders.9 In my previous work, eight terrorist group-types are crafted to capture different dynamics of terrorist groups active over the political landscape. Those group-types are differentiated from one another according to three defining characteristics that include ideology, leadership, and recruitment patterns.10 In the broader sense, those group-types include "theocentric" groups that embrace Islamic revivalism; "ethnocentric" groups that are nationalist-irredentist in nature; "ideo-ethnocentric" groups that are nationalist-irredentist groups with Marxist-Leninist trappings; and Jewish theocentric groups that embrace Jewish revivalism.

5 Since empirical observation suggests that charismatic leaders recruit from reservoirs of persons who share an almost singular vision of that leader's perception of fierce struggle, the four terrorist group-types are further delineated into those that are led by charismatic leaders and those that are not. For example, the category "theocentric" is broken down into "theocentric" and "theocentric charismatic," the category "ideo-ethnocentric," is split into two categories "ideo-ethnocentric" and "ideo-ethnocentric charismatic" and so on. This classification scheme presupposes and derives from studies of several terrorist groups that include, but are not limited to, Dr. George Habash's Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), Naif Hawatamah's Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), Rabbi Meir Kahane's Kach, and Benyamin Kahane's "Kahane Chai" organizations, as well as from authoritative works on "charismatic authority" and Middle East terrorism.11

6 In the case of the al-Aqsa Intifada, terrorist groups that fall into six of those eight categories are active in the political fray. Those groups include theocentric terrorist, theocentric charismatic terrorist, ethnocentric, ideo-ethnocentric, Jewish theocentric terrorist, and Jewish theocentric charismatic terrorist, or "proto-groups."12 In addition, I have fashioned other classification categories, such as "anonymous" terrorist assaults, "uncompleted" terrorist assaults, and "multiple-claimant" terrorist assaults.

7 In my earlier work, I develop a continuum of Middle East terrorist group-types in which purely "structuralist" terrorist groups fall at the left axis, and purely "non- structuralist" terrorist groups fall at the right axis.13 In the case of "structuralist" terrorist groups, the underlying struggle is conceived of as a struggle against what Immanuel Wallerstein would call "world systems," such as capitalism and imperialism.14 Alternately, in the case of "non-structuralist" terrorist groups, the struggle is viewed as being waged against persons who inhabit land that is not their "legitimate possession." In between, in the center range of that continuum lie "hybrid" Middle East terrorist group-types that embrace aspects of a "world systems" struggle approach and simultaneously the view, within the context of fierce struggle, that the enemy consists of persons who do not rightfully own the land under consideration.15 In the case of the al-Aqsa Intifada, the theoretical conceptualization about "structuralist" and "non-structuralist" terrorist groups revolves around targeting "attributes" of terrorist assaults committed by terrorist groups that fall within the six group types under consideration.16

8 One cornerstone of that conceptualization, that draws from Harvey Starr and Benjamin Most's work, is that charismatic leaders of Arab groups with a political ideology like the Marxist-Leninism of the PFLP will orient the group under their control to conduct targeting in ways similar to that of their Islamic counterparts ". . . because of a cultural 'positive spatial diffusion' of social and religious ideology that would shape the modus operandi of non-majority (e.g., Christian) terrorist groups to resemble the modus operandi of majority Arab/Islamic terrorist groups."17 At the same time, terrorist groups with charismatic leaders that embrace the "prevailing social ideology" of Islam tend to amplify generally recognizable sentiments, such as, for example, identifying the Israelis as groups or persons who inhabit Palestine in an illegitimate fashion.18 Hence, the expected result for ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups like Habash's PFLP is a strong emphasis on civilian targets to protest unjust occupation as a function of the influence of Habash's charismatic leadership on a terrorist group with Marxist-Leninist trappings.

9 At the same time, theocentric groups conceived of as a "hybrid" of "structuralist" and "non-structuralist" elements should also have notable focus on civilian targets and emphasis on government targets. In turn, ethnocentric groups, that are "non-structuralist" in nature, should have very strong emphasis on civilian targets as a result of the ethos of national-irredentist groups (i.e., ethnocentric types) that view the struggle as fierce competition between persons or groups. Theocentric charismatic terrorist groups as a function of the foregoing "amplification" dynamics, ought to place a premium on terrorist assaults on civilian targets that is sharper than theocentric group emphasis. The case of Jewish theocentric terrorist assaults ought to illuminate a different set of dynamics insofar as Jewish terrorist groups that operate predominately in "friendly" areas, such as the Occupied Territories and Israel, should assault civilian and government targets representative of the opposition to their political agenda, but with less intensity than their Arab/Islamic counterparts because they function, as Hoffman puts it, as "pressure groups" in Israeli society.19

10 The operational definition of "political terrorism" that is used in this study presupposes and derives from the "laws of war" of international law and is the same definition used in my previous work.the threat, practice or promotion of force for political objectives by organizations or a person(s) whose actions are designed to influence the political attitudes or policy dispositions of a third party, provided that the threat, practice or promotion of force is directed against (1) non-combatants (2) military personnel in non-combatant, or peace-keeping roles; (3) combatants, if the aforementioned violates juridical principles of proportionality, military necessity, and discrimination; or (4) regimes which have not committed egregious violations of the human rights regime that approach Nuremberg category crimes. Moreover, the act itself elicits a set of images that serve to denigrate the target population while strengthening the individual or group simultaneously.20

Data Collection

11 The data base for this study was put together primarily from two sources: the Jerusalem Post and the "Settler Violence and Occupation Watch" accounts published by The Alternative Information Center (AIC).21 While both sources are robust, it is probably no exaggeration to say that certain terrorist assaults, such as so-called "mega-terror" events as described by Major General Aharon Ze'evi (Farkash), are not chronicled in the Jerusalem Post because of national security concerns, and that because of the sheer number of terrorist assaults, certain minor terrorist assaults may not be given sufficient treatment.22 Clearly, that is one of the shortcomings of a database crafted from publicly available sources. Notwithstanding that, the omission of certain terrorist assaults probably would not change unduly the results, especially with the high number of more pedestrian terrorist assaults for which there is no plausible reason to conceal information. In turn, while the data from the AIC is comprehensive, two terrorist assaults by non-settlers are included in that data base as anonymous acts.23 In the case of Jerusalem Post entries, newspaper accounts were extracted from daily issues from 28 September 2000 through February 2002. As previously mentioned, that 17-month period is chosen for empirical study because it covers a pivotal first phase of the al-Aqsa Intifada that was able to generate and sustain psychological trauma and abject fear among Israelis, and showcased the unprecedented PFLP terrorist assassination of Israeli M.K. Rehavam Ze'evi on 17 October 2001.24

12 Precisely because this is a study of insurgent or oppositional terrorism, it follows that counter-terrorism assaults are excluded from the analysis. This includes counter-terrorist assaults that might be construed as examples of either state terrorism carried out by Israeli government forces, or "proto-state terrorism" practiced by the fledgling Palestinian National Authority (PNA). I made efforts to follow up on "unclaimed" or unidentifiable terrorist assaults with the goal of tracing an arc from them to summary accounts of events that followed for attribution purposes whenever possible.25 In the case of a relatively small number of al-Aqsa Intifada terrorist attacks chronicled in The New York Times, I tried to find matching accounts in the Jerusalem Post, and in the case of Jewish revivalist extremist group actions, matching accounts in the "Settler Violence and Occupation Watch" entries produced by the AIC when possible.

13 That data set is comprehensive with 1,617 terrorist incidents listed for the first 17-months of the al-Aqsa Intifada. However, it ought to be clear from the start that it does not claim to represent every terrorist assault that happened during the time period under consideration. As previously mentioned, many terrorist events have been omitted because of the large number of unclaimed and uncompleted incidents, presumably some of which remain unreported in the Jerusalem Post, in part because of national security concerns or because of selective bias due to the comparatively high frequency rate of terrorism events during that time period. Terrorist assaults may also have been omitted because of human error (e.g., double counting, wrongful inclusion of "terrorism events," missing bits of information).26 At a functional level, the foregoing definition of terrorism has been used as a guidepost for each chronicled account of a violent event under consideration to determine if that event ought to be included or excluded from the database. In some instances, assaults described in scripted articles as generally recognizable common criminal activity met the criteria, while in some cases, so-called "terrorist events" were excluded from the database.27

Coding Scheme

14 As in my prior work, the basic structure of the coding scheme for terrorist target-type selection revolves around "civilian," "government," and "infrastructure" targets.28 In the case of "civilian" targets, some examples include, but are not limited to, schools, commuter bus stations, discothques, theaters, kibbutzim, moshavim, Israeli settlements, commuter buses, and marketplaces. In turn, "government" targets include, but are not limited to, Israeli Border Police facilities and/or personnel, political actors, such as Israeli Minister of Tourism Rehavam Ze'evi, heads of state, European Union (EU) officials, military personnel on inactive status, and police officials.29 The category "infrastructure" refers to such targets as bridges, oil refineries, oil tankers, radio stations, television stations, energy facilities, and highways.

15 Plainly, the basic target constructs of this scheme make it possible to put together combinations to reflect primary and secondary targets or "compound" targets with various aspects of target-types associated with them.30 In the case where roadside bombs were placed on roads used by civilians, contextual analysis was used to include acts in the database even though the intended target could not be determined in a conclusive manner. At a functional level, contextual analysis is also important in cases where certain assaults were thwarted at some level. Those terrorist assaults may still be coded as completed incidents in some cases, for example when perpetrators who were traveling were discovered, leading to premature detonation of their bombs.31 With respect to location, East Jerusalem is coded as a part of the Occupied Territories rather than Israel.

Analysis: Relative Frequencies by Group-Type, Group, and Location

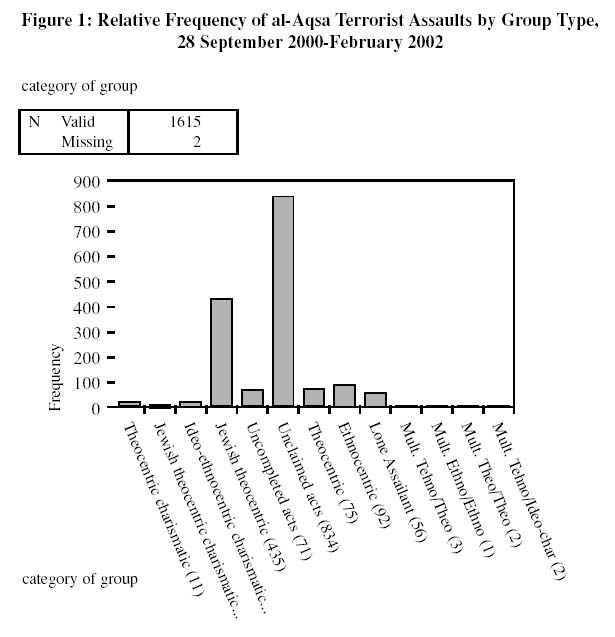

16 A breakdown of al-Aqsa Intifada terrorist events by group category reveals that the highest number of terrorist attacks recorded were anonymous; 843 out of 1,615 acts (52.2 percent of the total) were unclaimed by any individual or group. The second largest amount of terrorism and the largest amount that is attributable was carried out by Jewish theocentric "proto-groups," such as groups of Israeli settlers with 435 out of 1,615 acts or 26.9 percent. Terrorist assaults committed by ethnocentric groups rank third with 92 acts or 5.7 percent, while theocentric groups rank fourth with 75 acts or 4.6 percent.

17 While 4.4 percent of assaults were uncompleted, "lone assailant" comprised 3.5 percent (56 of 1,615). Terrorist attacks with "multiple claimants," by contrast, were very infrequent: only seven, or .4 percent of the total.32 Those trends with a high percentage of unclaimed terrorist assaults and a very low percentage of "multiple claimant" terrorist assaults are familiar from previous work.33 A further breakdown of "multiple claimant" acts informs us that three acts were claimed by an ethnocentric and a theocentric group, while two theocentric terrorist groups claimed two acts. Two multiple claimant terrorist assaults or .1 percent involved an ethnocentric and ideo-ethnocentric charismatic group (see Figure 1). The high rates of anonymous terrorist assaults and very low rates of "multiple claimant" acts are consistent with findings in my prior work.34

Relative Frequency of al-Aqsa Terrorist Assaults by Group Type, 28 September 2000-February 2002

Display large image of Figure 1

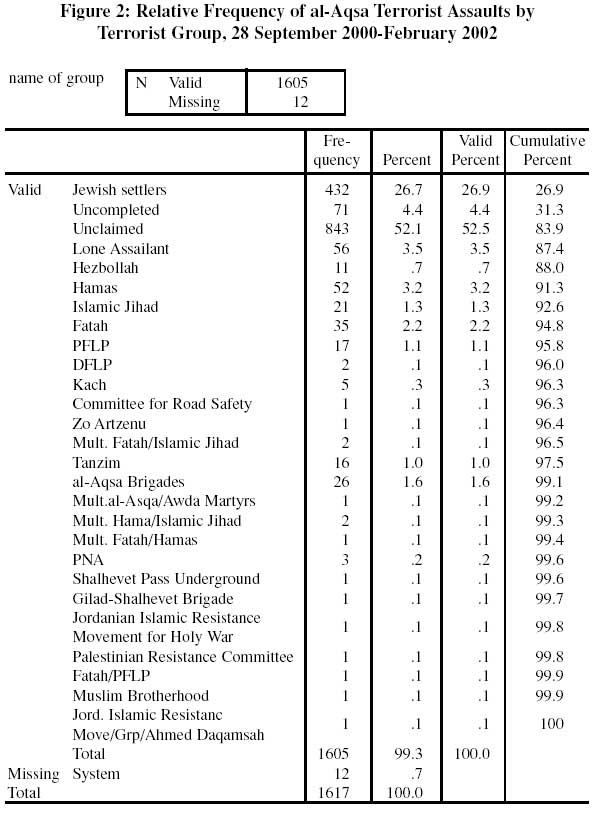

18 When the analysis is broken down according to identifiable terrorist groups, Hamas, otherwise known as the Islamic Resistance Movement, and al-Fatah, are found to be most prolific among Arab or Islamic groups. Hamas claimed 3.2 percent (52/1,615), while 2.2 percent (35/1,605 acts) were claimed by al-Fatah (see Figure 2). However, a newer terrorist "splinter" or "offshoot" group from al-Fatah ranks third overall. The al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, that Yael Shahar tells us first made its appearance in late September 2000, committed 1.6 percent of all terrorist attacks, while it and the Awda Martyrs Brigade, which is a Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) offshoot group, together committed 1.7 percent of the total.35 Attacks perpetrated by Islamic Jihad follow with 1.3 percent (21), while 1.1 percent (17/1,615) is attributable to the PFLP. What seems significant here is that the largest clusters of terrorist assaults revolve around anonymous actors, and more loosely organized "proto-groups" of Israeli settlers, which together, accounted for nearly 80 percent of all incidents. At the other extreme, there are more shadowy terrorist groups that carried out one terrorist assault (.1 percent) each. These include the Jordanian Islamic Resistance Movement for Holy War, the Palestinian Resistance Committee, which as Arieh O'Sullivan tells us "includes members of Fatah, Hamas, and Islamic Jihad," and the Islamic Action Party that is a military wing of the Muslim Brotherhood.36

Relative Frequency of al-Aqsa Terrorist Assaults by Terrorist Group, 28 September 2000-February 2002

Display large image of Figure 2

19 I performed an analysis that seeks to isolate and identify terrorist groups active from the start of the al-Aqsa Intifada in order to chronicle terrorist groups that became active only with the passage of time and to help illuminate terrorist offshoot and splintering dynamics. Accordingly, I tagged identifiable attacks between 28 September and through November 2000. This analysis, which excludes uncompleted assaults, suggests that Hamas (four acts), al-Fatah (three acts), Islamic Jihad (two acts), the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades (one act), the "Tanzim" (one act), and Hezbollah (one act) were predominant. Other incidents, assaults included one threat by the Muslim Scholars of the Islamic Action Front Party, and a "multiple claimant" attack in Amman, Jordan claimed by the Jordanian Islamic Resistance Movement and the Army of the Holy Warriors Ahmed Daqamsah.37 What seems significant here is that ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups, such as the PFLP and DFLP, and DFLP offshoots like the al-Awda Martyrs Brigades, were relative latecomers to the military fray.38 It was only in February 2002 that an identifiable assault was claimed by al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades and the al-Awda Martyr Brigade. Those findings are consistent with the central idea that terrorist groups on the margins of fierce struggle may produce offshoot groups that are a better fit with the immediate context of conflict, insofar as DFLP and PFLP are more closely associated with the Palestinian Diaspora in places like Syria rather than in the Occupied Territories.39 Those findings are also consistent with the central idea that terrorist groups on the margins may need to elicit cooperation from groups, such as al-Fatah, that are inextricably bound up with the struggle, and that desire to cooperate may presuppose and derive from a need to share the arena of politics and a need for increased visibility.40

20 In the case of Jewish revivalist terrorism conducted by more tightly interwoven terrorist groups, Kach, which is a time-honored terrorist group even though it was officially banned by the Israeli government in 1994, carried out only five acts, a mere .3 percent. Likewise, the Committee on Road Safety, that is a "Kach spin-off organization" carried out only one attack. Zo-Artzenu, which is a Kach-Kahane Chai-related political group established in 1993 and known to straddle the fence between legal and extralegal activity, also committed only one terrorist assault. The Gilad-Shalhevet (Pass) Brigade, that probably coalesced after the attacks that killed Shalhevet Tehiva Pass and Gilad Zar in March and May 2001 respectively, carried out only two acts.41 Those sparse findings for more established groups resonate with the central notion of "leaderless resistance" associated with both Carlos Marighella, the Brazilian Marxist-Leninist terrorist chieftain who was killed in 1969, and Louis Beam of the American Ku Klux Klan organization. Under this strategy, looser, more informal ties among persons permit terrorist attacks to unfold in effective and sustained ways, while helping to make counter-terrorist actions against perpetrators more difficult.42

21 For Jewish revivalist terrorism, analysis of the data reveal that Jewish settler "proto-group" terrorist assaults dominate the political landscape from 28 September through November 2000. It is only in January of 2001 that identifiable Jewish theocentric charismatic and Jewish theocentric terrorist groups, such as Kach and Kach affiliates like the Committee on Road Safety and in time the Shalhevet Pass Underground (Brigade), begin to make their formal appearance. While the splintering and offshoot dynamics of some of the foregoing groups are murky, it seems plausible to suggest that what at first was an environment comprised of more loosely organized Jewish settler "proto-groups" continuously evolved as the al-Aqsa Intifada and its pressures grew apace, thereby in effect helping to craft a landscape where Jewish settler "proto-groups" and more formally articulated terrorist groups work side by side.43

22 With respect to location, analysis of the data informs us that a full 88.8 percent (1,403/1,580) of the terrorist assaults happened in the Occupied Territories, while only 10.3 percent (162/1,580) took place in Israel.44 In the broader sense, the total amount of al-Aqsa Intifada terrorism that happened inside the Occupied Territories and Israel amount to 1,565/1,580 acts (99.1 percent). With respect to other locales, only seven acts occurred in Lebanon, while four events took place in Jordan. In the case of Jewish revivalist terror, a separate test reveals that 99.3 percent of Jewish theocentric group or "proto-group" terrorist attacks (431/434) happened in the Occupied Territories, while only .7 percent (three acts) happened in Israel. By contrast, 83.3 percent of Jewish theocentric charismatic terrorist assaults (five out of six acts) took place in the Occupied Territories, while one incident happened in the United States. No Jewish theocentric charismatic terrorist assaults happened in Israel.45

Analysis: Terrorist Act Attributes: Fatalities, Injuries, Property Damage, Target Preference

23 One of the single most predominant themes that flow through the extant literature is that terrorism does not rely on enormous amounts of physical devastation for its power but rather on its psychological import to thrive in effective and sustained ways. Analysis of al-Aqsa Intifada terrorism with respect to "event deaths" and "event injuries" is supportive of that underlying theme. While estimates of the number of dead in the al-Aqsa Intifada fluctuate to a considerable extent, in the case of event deaths, I found that only 120 out of 1,602 acts (7.5 percent) during the 17 months under consideration resulted in the deaths of between one and 50 persons. Conversely, a full 92.5 percent of terrorist assaults (1,482/1,602 acts) did not cause any deaths. A total of 238 deaths was reported for the 28 September 2000 through February 2002 time period.46 That figure is much lower than the reported 800 deaths claimed by the Palestinian Red Crescent Society and the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs or the reported 500 death figure issued by the Palestinian Rights Monitoring Group in September 2001.47 This figure may be low because it excludes deaths associated with counter-terror offensives.

24 In a similar vein, a breakdown of attacks by injury rates also provides strong support for the aforementioned theme.48 A total of 2,395 injuries was reported for the period. The mean for terrorist event injury is 1.57 with a standard deviation of 8.90. A full 68.6 percent of all incidents (1,046/1,524) were injury-free events. In turn, 30.8 percent (470 acts) caused injuries to between one and 50 persons, while five assaults (.3 percent) caused injuries to between 51 and 100 persons. In addition, there are three more extreme outlier cases that lie over 14 standard deviations from the mean.49 In one event, 130 persons were wounded, another resulted in 150 persons hurt, while in the third, 160 persons were injured. One notable finding is that all of the outlier cases happened in Israel, rather than in the Occupied Territories.50

25 Analysis of property damage arising from these attacks also reveals patterns consistent with the central idea that terrorism does not rely on an enormous capacity to cause physical devastation. I found that over one-third of all events (38.8 percent or 358/922) did not result in any discernable property damage. A full 55.7 percent (514/922) caused "slight" damage (defined as less than or about $US 15,000). Moderate damage (defined as from about $US 30,000 to $US 100,000) occurred 5.4 percent of the time (50/922 cases). None of the recorded attacks yielded "high" or "severe" property damage (in the $100,000 to $1 million + range).51 In turn, analysis of target type frequencies reveals that a full 92.0 percent of all attacks (1,454/1,581) were directed at civilian targets, while only 7.8 percent of all attacks (123 out of 1,581) were directed against government targets. Assaults against infrastructure were extremely rare; only four acts were recorded.

26 The most statistically significant findings in this category are those concerning civilian targets. The extremely heavy emphasis on civilian targets is a marked departure from the pattern of Israeli-Palestinian-Arab terrorism between 1994 through 1999.52 In that period, civilians accounted for 77.7 percent of targets. Writers such as Rashid Khalidi suggest that emphasis on civilian target assaults seems to be a proactive strategy by the Palestinian resistance leadership, which aims to pursue, by what amounts to "propaganda by deed," political goals that have been elusive under the Oslo frameworks.53 It may also reflect the emergence of a full-blown war between Israelis and Palestinians that is discussed below.

27 The foregoing results make it possible to articulate some of the parameters of al-Aqsa Intifada terrorism. First, when the data for this period are broken down according to group category, the largest number and percentage of al-Aqsa terrorist assaults were carried out by anonymous terrorist groups or non-group actors, followed by loosely organized Jewish theocentric terrorist "proto-groups," ethnocentric groups, theocentric groups, uncompleted acts, and "lone assailants."

28 With respect to identifiable al-Aqsa terrorist group or "proto-group" attacks, Jewish theocentric "proto-groups" rank first, followed by Hamas and al-Fatah, with a virtual tie between the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades and Islamic Jihad. The major roles played by al-Fatah affiliated groups, such as al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades and other "Tanzim," complicates the ranking process. Seen from a different angle, al-Fatah, coupled with al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades and so-called "Tanzim" comprise a full 4.8 percent that would promote an al-Fatah aggregate measure into second place. Furthermore, it is likely that the bulk of anonymous terrorist assaults were carried out by al-Fatah or al-Fatah affiliated groups, in addition to Hamas and Islamic Jihad. Indeed, Ruth Beitler tells us that cooperation and coordination between al-Fatah and Hamas is often managed in effective and sustained ways.54

29 With respect to location, what seems significant here is that the 8.6:1 ratio in favor of attacks in the Occupied Territories in this time period is far greater than the nearly 1:1 ratio for the 1994-99 period, when Israel experienced 33.7 percent of Israeli-Palestinian-Arab terrorist attacks and the Territories experienced 30.8 percent.55

30 In the broader sense, the data reveal that al-Aqsa terrorism caused relatively low amounts of physical devastation as measured by numbers of deaths, numbers of injuries, and property damage when compared to other forms of ethnic conflict or to full blown war.56 While devastation rates remain comparatively low, the outlier cases with respect to injuries all occurred within Israel rather than within the Occupied Territories. While those findings support the importance of location as an explanatory variable to help account for differences in terrorist attack "attributes," there is no definitive interpretation as to why location patterns have shifted during this period, as compared to Israeli-Palestinian-Arab terrorism for the 1994-99 time frame.57 Notwithstanding that, one interpretation consistent with this data is that the large proportion of attacks in the Occupied Territories mirrors the experiences that Beitler highlights, namely that the relatively non-violent actions of the First Intifada, largely relegated to the Occupied Territories, were simply not effective in terms of capacity to generate and sustain meaningful political concessions from the Israelis.58 Plainly, the emergent reality that the First Intifada began to pass into eclipse within the context of international events, namely the Persian Gulf War, might have compelled even those with almost singular focus on "liberation" of the Occupied Territories, as opposed to the full blown "territorial maximalism" of the extremists, to take the fight beyond the "Green Line" into Israel.59 This does not explain the shift back to the almost exclusive concentration of attacks in the Territories during the 2000-02 period under study.

Analysis: Political Ideology and Target Type

31 This portion of my analysis uses two hypotheses to examine the relationship between political ideology of terrorist groups, and their target choices. The first hypothesis captures the notion that nationalist-irredentist groups with Marxist-Leninist trappings led by a charismatic leader (i.e., ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups) should focus special attention on civilian targets because, as explained earlier, charismatic leaders of terrorist groups with a political ideology that is different from "the prevailing social ideology of Islam," will amplify generally recognizable propositions that focus on Israelis as persons who occupy Palestine.60 Hypothesis Two is based on the notion that theocentric terrorist groups as "hybrid" types will attack civilian targets with less intensity than ethnocentric terrorist groups.61 Hypothesis One: Ideo-ethnocentric charismatic terrorist groups will attack civilian targets more often than theocentric terrorist groups. Hypothesis Two: Ethnocentric terrorist groups will attack civilian targets more often than theocentric terrorist groups.

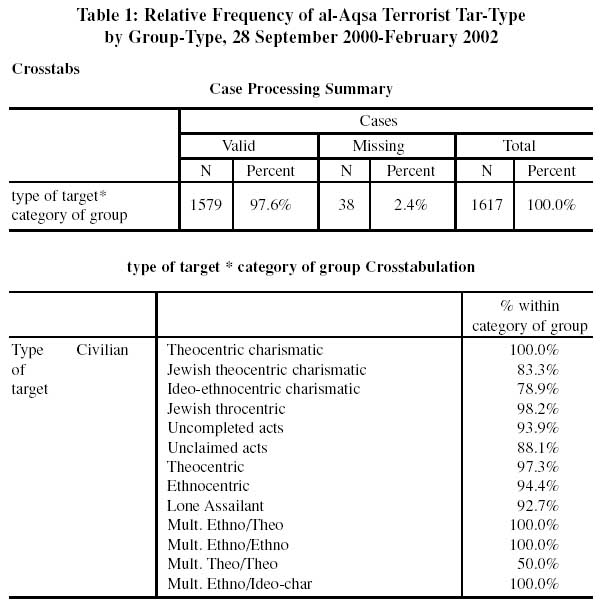

32 A cross-tabulations test suggests that a substantive and significant relationship exists between the variables "target type" and "category of group."62 The data distribution informs us that theocentric charismatic groups have the highest rate of terrorist attacks directed against civilian targets: a full 100.0 percent or 11/11acts. Jewish theocentric attacks rank second with 98.2 percent of attacks (425/433) while theocentric terrorist group attacks involved civilian targets 97.3 percent of the time (73/75). Ethnocentric civilian target attacks rank fourth with 94.4 percent (85/90), and uncompleted terrorist attacks rank fifth; they focused on civilian targets 93.9 percent of the time (46/49 instances). "Lone assailant" assaults place sixth (92.7 percent or 51/55 attacks). At the other extreme, ideo-ethnocentric charismatic attacks have the lowest rate of all: only 78.9 percent (15/19 acts). Plainly, this finding for ideo-ethnocentric charismatic terrorist assaults is unexpected. In turn, Jewish theocentric charismatic groups have the second lowest rate of civilian target attacks (83.3 percent or five out of six events). All but one "multiple claimant" incident were directed against civilian targets. At the same time, it should be noted that the civilian target range under consideration is very small, and most of the foregoing group-types show an overwhelming preference for civilian targets (See Table 1). Therefore, the findings disprove both hypotheses.Relative Frequency of al-Aqsa Terrorist Tar-Type by Group-Type, 28 September 2000-February 2002

Display large image of Table 1

33 Insofar as leading authorities, such as Khalidi, have pointed to the urban warfare context of the al-Aqsa Intifada that pushes beyond military targets to focus on civilian targets in the cities, those findings, while at odds with the expected results, are consistent with what urban warfare is all about.63 In his work, P.N. Grabosky tells us of the advantages of target availability in an urban context, where civilian targets as well as government targets abound and are found in close proximity to one another.64

Analysis: Political Ideology and Numbers of Dead

34 The following hypothesis derives from earlier work of mine, which suggests that more "non-structuralist" Middle East terrorist groups, such as ethnocentric groups that view their struggle as opposition to groups of persons, rather than against what Wallerstein would call a "world system" like capitalism, place a special emphasis on civilian targets in terrorist attacks.65 If this hypothesis is correct, then the percentage of ethnocentric terrorist attacks that killed between one and 50 persons ought to be relatively high when compared to other types of terrorist groups under consideration. Hypothesis Three: Ethnocentric terrorist groups will have a higher percentage of terrorist acts that cause deaths than terrorist acts committed by theocentric terrorist groups.

35 The statistical testing reveals that a systematic and substantive relationship exists between the variables "political ideology" and "numbers of deaths."66 The data distribution shows that ethnocentric groups have the highest percentage rate of terrorist assaults that killed between one and 50 persons (39.6 percent or 36 out of 91 acts) and that rate represents a little over one-third of all ethnocentric attacks. Theocentric terrorist groups rank second (21/74) (28.4 percent), while theocentric charismatic terrorist ones come third (2/11) (18.2 percent) of all theocentric charismatic attacks. Jewish theocentric charismatic groups follow closely with 16.7 percent (1/6), while 15.8 percent (3/19) ideo-ethnocentric charismatic assaults killed between one and 50 persons. At the other extreme, Jewish theocentric groups have the lowest rate of attacks (2.8 percent or 12/433 acts), while anonymous actors have the second lowest rate (3.7 percent or 31/843).

36 One set of findings concerns "multiple claimant" assaults, where 57.1 percent (4/7) killed between one and 50 persons. This was shown in two out of the three attacks (66.7 percent) claimed by both an ethnocentric and a theocentric group. One out of two assaults claimed by an ethnocentric and an ideo-ethnocentric charismatic group, and one out of two claimed by two theocentric groups also killed between one and 50 persons. Hence, three of those four "multiple claimant" assaults were claimed by terrorist groups across group-types, while one of them was claimed by terrorist groups within the same terrorist group-type.67 So, the data findings support Hypothesis Three and it is accepted as valid.

Analysis: Political Ideology and Sub-Locale

37 At a functional level, analysts of the al-Aqsa Intifada sometimes depict that fierce struggle as urban-based warfare, that has pushed over and beyond generally recognizable strikes and protests in the Palestinian urban centers that were a hallmark of the First Intifada.68 For example, Khalidi, who is critical of Palestinian attacks against civilian targets in the Israeli "metropole," tells us, "that their effort [should] be directed . . . from ever carrying out attacks against anywhere in the metropole . . . indeed many of the attacks since September 2000 have lost the Palestinian cause potential friends and swelled the ranks of its enemies."69 At the same time, Remma Hammami and Salim Tamari suggest that a central theme of the continuously evolving environment of the al-Aqsa Intifada revolves around attacks against Israeli settlements.70 The following hypothesis captures the notion that cities and towns, and Israeli settlements are the primary loci of terrorist assaults: Hypothesis Four: al-Aqsa Intifada terrorist assaults will happen in cities or towns most frequently and there will be very strong emphasis by terrorists against Israeli settlements.

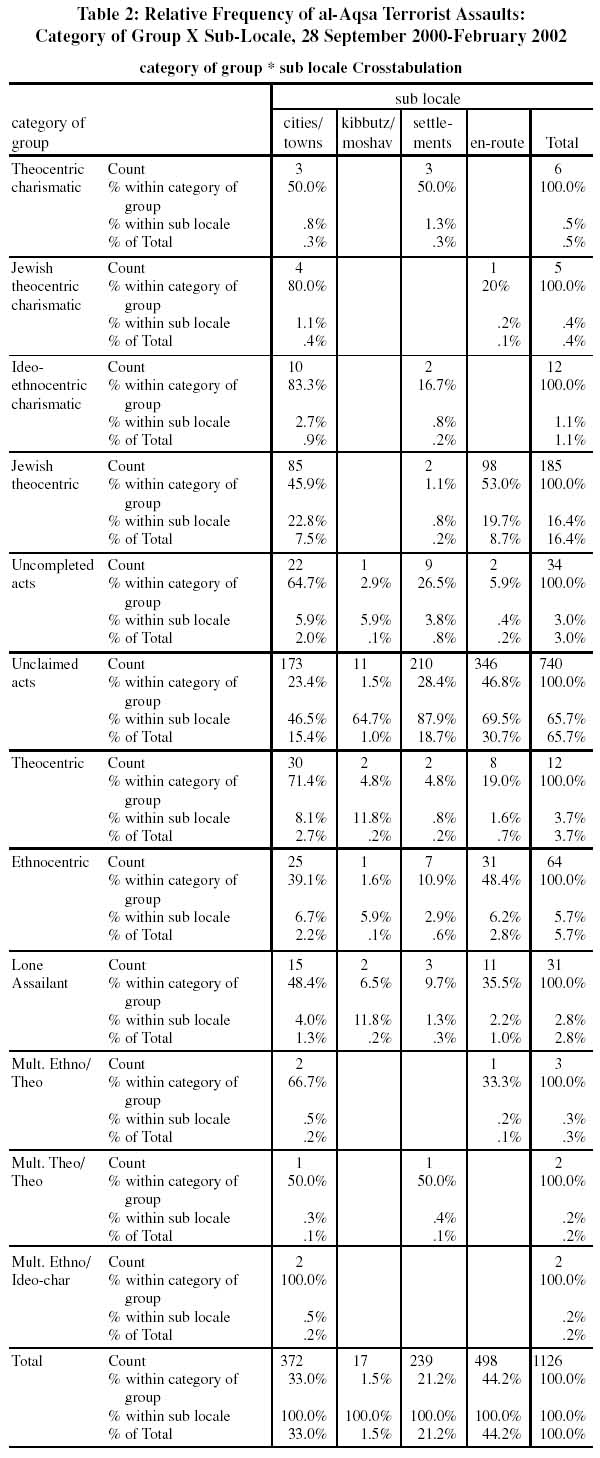

38 A cross-tabulations tables analysis suggests that a strong correlation exists between the variables "political ideology" and "sub-locale."71 The data distribution informs us that 44.2 percent of the incidents under study (498/1,126) are directed at targets en-route, such as automobile drivers. Terrorist assaults against cities or towns have the second highest rate of attack (33.0 percent or 372/1,126). Assaults against Israeli settlements rank third at 21.2 percent (239/1,126 acts), while attacks against kibbutzim or moshavim have the lowest rate of attacks: only 1.5 percent or a mere 17 out of 1,126. In the broader sense, Hypothesis Four must be rejected since the expected findings that cities or towns will be the most common venue for attacks and the that attacks against Israeli settlements will play a predominant role in terrorist assault strategy are not supported by the results.

39 The data distribution also reveals the predominant position of anonymous terrorist assaults in the political fray. In the case of all en-route attacks, unclaimed acts have the highest rate (69.5 percent or 346/498). Jewish theocentric attacks place a very distant second with 19.7 percent (98/498), followed by ethnocentric groups with 6.2 percent (31/498). For "lone assailants," the rate is 2.2 percent (11 attacks). In the narrower sense, which types of groups seem to favor most attacks against moving targets? The findings reveal that 53 percent of all Jewish theocentric acts, (98/185) were directed against such targets. Ethnocentric groups accounted for 48.4 percent (31/64) while unclaimed acts represent a nearly identical rate: 46.8 percent (346/740). (See Table 2). Relative Frequency of al-Aqsa Terrorist Assaults: Category of Group X Sub-Locale, 28 September 2000-February 2002

Display large image of Table 2

40 In the case of all city or town attacks, unclaimed acts account for the highest percentage (46.5 percent or 173/372), followed by Jewish theocentric attacks (22.8 percent or 85/372). Theocentric terrorist assaults rank third at 8.1 percent (30/372), while ethnocentric attacks came fourth at 6.7 percent (25/372). "Lone assailant" attacks were infrequent: only 15 attacks (four percent), but of the seven "multiple claimant" acts chronicled here, five happened in a city or town.72 Among all ideo-ethnocentric charismatic attacks, a full 83.3 percent (10/12) happened in cities or towns, followed by 80.0 percent (4/5 acts) for all Jewish theocentric charismatic attacks. In turn, 71.4 percent (30/42) of all theocentric incidents occurred at these locales, while 50 percent (3/6) of all theocentric charismatic attacks occurred in cities or towns, and for all "lone assailants" attacks, 48.4 percent (15/31 acts) were carried out in cities or towns.

41 In the case of all attacks against Israeli settlements, unclaimed incidents rank first at 87.9 percent (210/239). In other words, almost 90 percent of attacks against Israeli settlements remain unclaimed or unattributable. However, one out of seven "multiple claimant" terrorist assaults involved an Israeli settlement.73 The findings suggest that theocentric charismatic groups favor attacks against Israeli settlements the most out of all types of terrorist groups with 50.0 percent (3/6 acts). In turn, unclaimed acts rank second with 28.4 percent (210/740 acts), and uncompleted acts came third with 26.5 percent or nine out of 34. Ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups follow with 16.7 percent of all attacks (2/12), while ethnocentric groups with 10.9 percent (7/64) follow in turn. At the other extreme, for all theocentric group attacks settlements were the target of choice only 4.8 percent of the time (2/42 acts).

42 In the cases of all kibbutzim or moshavim attacks, unclaimed acts (64.7 percent or 11/17 acts) have the highest percentage, followed by theocentric groups and "lone assailants," each with rates of 11.8 percent (2/17 acts). Likewise, there is a tie for third place ranking between ethnocentric group attacks and uncompleted terrorist actions at 5.9 percent (1/17 acts) each. Among category types, "lone assailants" favor kibbutzim or moshavim attacks the most with 6.5 percent (2/31 acts), followed by theocentric groups with 4.8 percent (2/42 acts), and uncompleted acts with 2.9 percent (1/34 acts). There are no identified theocentric charismatic or ideo-ethnocentric charismatic group attacks against kibbutzim or moshavim for this time period, nor are there any "multiple claimant" terrorist assaults. What seems significant here is that the rate of unclaimed terrorist assaults diminishes with movement away from rural settings, such as kibbutzim or moshavim and settlements toward urban locales.

43 In conclusion, Jewish theocentric charismatic groups prefer cities or towns as venues for terrorist attacks, while Jewish theocentric groups seem more evenly split in terms of venue preference between targets on the road and targets in cities and towns. Among identifiable Arab nationalist or Islamic terrorist group-types or both, ideo-ethnocentric charismatic terrorist groups most prefer terrorist assaults in cities or towns, while ethnocentric terrorist groups favor terrorist attacks against moving targets on the road, but nonetheless conduct over one-third of actions against targets in cities or towns.74 In turn, when comparisons are made across terrorist group-types, theocentric charismatic terrorist groups are found to favor attacks against Israeli settlements the most. Theocentric terrorist groups are found to favor attacks against kibbutzim and moshavim the most when terrorist group-types are compared.

44 What seems significant here is that theocentric terrorist groups appear to find some utility with respect to targeting Israeli settlements, kibbutzim or moshavim, that are perhaps the most rural of all sub-locales. Conversely, there were no ideo-ethnocentric charismatic terrorist assaults against kibbutzim and moshavim between September 2000 through February 2002, and only two out of 12 acts were directed against Israeli settlements. For ethnocentric groups, over one-third of their attacks occurred in cities or towns and nearly half were directed against moving targets on roads. Those findings suggest that among some Islamic and/or Arab terrorist group-types, or even between some Arab nationalist-irredentist and Islamic terrorist group-types, there are apparent differences in conception about the utility of the urban setting as the primary venue of conflict. Hence, broad brush depictions of al-Aqsa Intifada fighting as urban in nature may mask more subtle differences in terrorist leader targeting behavior, perhaps based on terrorist group ideology-type, that are important for counter-terrorist assault analysts to consider.

Final Reflections

45 Plainly, one of the single most predominant set of findings for the Intifada in this period revolves around the central role that civilian targets play in an overwhelming majority of al-Aqsa terrorist assaults. As previously mentioned, 92.0 percent of the attacks involved civilian targets. Jewish theocentric terrorists focused on civilian targets 98.2 percent of the time, while Jewish theocentric charismatic groups, such as Kach directed attacks against civilian targets 83.3 percent of the time.

46 In essence, that extreme emphasis on civilian targets marks a departure from earlier target selection trends in Israeli-Palestinian-Arab terrorism that showcase preferences for civilian targets, but at a ratio of 3.5:1, by contrast to the over 12:1 ratio in favor of civilian targets found in this work. There is no definitive interpretation as to why that rate of civilian target assaults has grown apace, but findings for Palestinian terrorist groups and non-group actors are consistent with the central notion that attacks against civilian targets in urban areas and on roadways comprise a proactive strategy on the part of terrorist leaders.75 It is possible that this stratagem contributed to the resurrection of the idea of building a defensive wall through areas of the West Bank, a notion that can be traced back to the Rabin era through the concept of "separation."

47 One important set of findings reveals that different types of Arab or Muslim terrorist groups may favor one type of locale over another as settings for terrorist assaults. Claims of responsibility seem to matter most for assaults in urban settings. In the case of Jewish revivalist terrorism, which all too frequently revolves around destruction of Arab property, such as olive groves and homes, the evidence suggests that, contrary to the common wisdom prevalent in some circles that Jewish terrorism is in large part a reaction to terrorism, the bulk of Jewish terrorism is proactive, not reactive in nature.76 Two-thirds of all Jewish theocentric charismatic group terrorist attacks were independent acts, while only one-third occurred in reaction to terrorist assaults. For all Jewish theocentric groups or "proto-group" attacks, a full 86.4 percent (375/434 acts) were independent events, with only 9.9 percent done in reaction to terrorism.77

48 When analysis is performed to isolate and identify the types of terrorist groups found at earlier and later states of the period under consideration, what seems significant is that in the case of Palestinian terrorist groups, Hamas, Islamic Jihad, al- Fatah, al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, and the "Tanzim" dominated the landscape from the start, and that the PFLP, DFLP, and their affiliates entered the military fray only with the passage of time. In the case of Jewish revivalist terrorism, the data suggest that Jewish settler "proto-groups" predominated from the start, but that attributable terrorist assaults carried out by more formally articulated Jewish revivalist terrorist groups, such as Kach and the Shalhevet Pass underground, grew apace over time.

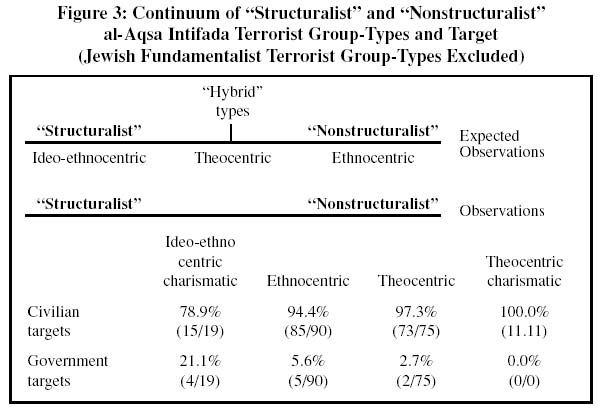

49 The data distribution reveals that observed results for terrorist group-type target selection rates are not consistent with expected observations associated with the Middle East terrorist group-type continuum. Theocentric charismatic terrorist groups rank highest for civilian target terrorist assaults with 100.0 percent (11/11 acts), and those results place that group-type at the "non-structuralist" axis rather than toward the middle of the continuum where "hybrid" types ought to be found. Theocentric groups are also found toward the "non-structuralist" axis of the continuum with a civilian target rate of 97.3 percent (73/75 acts). For ethnocentric groups, the expected result is a position close to or at the "non-structuralist" axis, but the observed findings place ethnocentric groups to the left of theocentric groups with a civilian target rate of 94.4 percent or 85/90 acts (see Figure 3).

Continuum of "Structuralist" and "Nonstructuralist" al-Aqsa Intifada Terrorist Group-Types and Target (Jewish Fundamentalist Terrorist Group-Types Excluded)

Display large image of Figure 3

50 It is probably no exaggeration to say that results for terrorist group-type and target selection would be more meaningful if there was significant variation in target type selection between civilian targets and government targets by group-type. Seen from a slightly different vantage, what is clear is that the range with respect to civilian target terrorist assaults across group-types is, for the most part, very small. In the broader sense, while efforts to position al-Aqsa Intifada terrorist group-types along the continuum remains problematic, some of the observed findings do conform to expected observations. For example, the expected finding that theocentric charismatic terrorist groups place a premium on civilian target terrorist assaults, because of their "hybrid" nature and charismatic leadership, is supported by the findings. Likewise, the expected finding that ethnocentric groups would place strong emphasis on civilian targets is also supported by the results. While theocentric groups seem to place more emphasis on civilian targets and less on government targets than anticipated, the general position of placement on the continuum near but not at the "non-structuralist" axis, is generally consistent with the notion of theocentric groups as "hybrid types," and the notion that the "militarized nature" of the al-Aqsa Intifada, as Hammami and Tamari put it, or the context of the al-Aqsa Intifada, may have altered or amplified aspects of target selection practices.78

51 It follows that if the context of full-blown resistance may alter or skew terrorist target preference, then one way of thinking about why civilian terrorist targets are in such sharp focus revolves around the relative decline in effectiveness of governmental control at specific geographical locales and in specific time frames, and the abject fear that is generated and sustained in a most effective fashion by means of civilian targetting. It may be significant that the preference for civilian targets by Palestinian terrorist groups and non-group actors mirrors findings for Algerian terrorism between 1994 through 1999 where 84.2 percent of terrorist attacks were directed at civilian targets and only 10.6 percent involved government targets.79 Even though the al-Aqsa Intifada is not "a civil war" as Michael Dunn has described the conflict in Algeria, the underlying dynamics of target selection that are inextricably bound up with what resembles a full blown war deserves the increased devotion of scholars.80 In essence, the study of terrorism within the al-Aqsa Intifada becomes increasingly important not only because of what is illuminated about terrorist targeting in this round of Israeli-Palestinian-Arab violence, but because such empirical work helps to shed light on the dynamics of contemporary wars of resistance in urban settings, a topic under consideration in a most carefully reasoned way in the wake of the occupation of Iraq by military forces from the United States and Great Britain.

Richard J. Chasdi is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at Wayne State University.Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Michael S. Stohl of the University of California, Santa Barbara, Professor Frederic S. Pearson at the Center for Peace and Conflict Studies at Wayne State University, Dr. Joshua Sinai, Professor Ilan Peleg of Lafayette College, and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. I would also like to thank my wife Sharon, Neal, Brendan, and Vel for their steadfast support.Endnotes