Articles

Contrasting Approaches to Terrorism:

A Multi-National Comparison

ABSTRACT

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on the United States on 11 September 2001, the prime ministers of Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom began the task of framing these events for their respective audiences through their many public addresses and speeches. Given their different geographic locations, political cultures, and experiences with terrorism, the ways in which these attacks were framed differed. Each of these prime ministers was concerned with managing local circumstances in the face of global challenges to security. As the most public representatives for their respective countries, the prime ministers’ efforts to present events in particular ways is critically important in terms of how the local and global public interprets events. We examine the period immediately following 9/11 and consider how communicating these acts may have been impacted by general and specific terrorist security threats against these countries; their respective political histories with the United States; and the resources available to each prime minister (and his country) to address these concerns. Finally, we consider the legislation that has since been put in place by these three countries to deal with terrorism.

INTRODUCTION

1 The terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 brought security issues into global focus in a striking and formidable way. As Sebastian Barnutz observes, that date marked a turning point in the ways in which security and threat were defined.1 Robert Ivie and Oscar Giner noted that there has been a "ritualized story of danger" that has defined the United States since 11 September.2 The interpretation of these attacks differs substantially depending upon the perspectives of observers relative to the incident. For example, individuals are more or less impacted given their particular social, personal, and geographic circumstances. Individuals perceive events differently in their lives depending upon life circumstances; risks are defined and addressed differently depending upon how factors impact their lives. For example, one might expect that those who are wealthy define risks differently from those who struggle economically. Similarly, states also inhabit particular circumstances and are more or less threatened by global events depending upon their respective situations both domestically and on the world stage.

2 This article considers how the prime ministers of Canada, Britain, and Australia responded to the threat posed by the terrorist attacks on the United States on 11 September 2001. The prime ministers were the literal faces of security in the aftermath, and each commented on the terrorist threat and the positions each country took. However, Canada, Britain, and Australia maintained appreciably different positions because of their geographic relationship to the United States. Beyond physical proximity, each country also occupies a different position based on its relationship with the United States; with each other and the world community; and with its own respective citizens. Canada’s interdependence with and proximity to the US is unique among the three countries considered here. The historical ease of passage between the United States and Canada and the magnitude of the trade relationship are significant factors impacting their relationship. Moreover, Canada is the foremost trading partner of the US. While both Britain and Australia have trade relations with the US, their connections are based less on economic factors than on ideological and political issues. Additionally, Canada, Britain, and Australia are members of the Commonwealth of Nations. "The purpose of the Commonwealth is consultation and cooperation"3 and member nations generally have economic, trade, and development ties. But membership in the Commonwealth does not imply any control over its members, each is independent.

3 The initial official reaction from all three countries to the terrorist attacks was unequivocally that the terrorist attacks were considered an unacceptable act of aggression against the entire civilized world, not just against the United States. What soon became evident were the different ways that each framed the on-going threat of terrorism, especially as the focus of attention turned from Afghanistan to Iraq, and what should be done about it. Furthermore, the communications from each prime minister used the attack as a vehicle through which other only tangentially-related messages could be transmitted. As Mitchell Dean notes: "risks have a certain polyvalence, i.e. they can be invested with different sets of purposes depending on the political programmes and rationalities they come to be latched onto."4 Canada’s official messaging focused heavily on the trade element, while Britain used the attack to frame its unique position in world affairs as a bridge between the US and Europe. Australia, on the other hand, tagged the issues of immigration and border security to its discourse.

4 Our discussion begins with a consideration of the notion of risk positions and how this applies to each of these states. Social, economic, and political factors provide the contexts from which countries identify and respond to terrorist threats. We briefly describe the foreign-policy agendas associated with each of the three countries, noting that foreign policies may be seen as a resource associated with more or less capital, and capital of varying kinds. We then consider the content of the communications emanating from each prime minister’s office, including speeches, statements, and press releases issued during the period September 2001 to December 2003. Legislation emerging from each country is then examined, along with local and global events during the period September 2001 to December 2009. Finally, we discuss the ways in which risk positions have or have not evolved since 9/11 and its implications for collaborative and singular efforts to secure against terrorist threats.

Risk Positions

5 Just prior to the turn of the twenty-first century, many social theorists suggested that we were entering a new era: the risk society. For Ulrich Beck, in particular, this meant that the former basis upon which social groupings were made — primarily access to resources — were replaced by the democratizing effect associated with the threats faced in today’s world.5 Rather than class position or access to goods determining one’s social position, Beck theorized that vulnerability to threat, or exposure to "bads," would become the basis upon which classifications would be made. Vulnerability would replace wealth as the glue holding particular groups together and others apart. It is clearly not the case that wealth has become irrelevant in today’s society, since those with greater wealth are able to buy protection in the face of adversity. At the same time, vulnerability to particular types of threats facilitates a form of cohesion or collective agreement among various parties that may have been unlikely in the absence of those threats.

6 With respect to risk positions among states, this means there are differences that will not be eliminated in the face of threats such as terrorism. It is problematic to suggest that less wealthy countries are able to protect themselves with the same effectiveness as more wealthy countries. For example, poor countries in Africa cannot protect themselves against terrorism in the same way that wealthy European states might. Moreover, the threat of terrorism is not equal among countries. For example, compared to more wealthy countries, poorer countries make less attractive targets and therefore might be less likely to be targeted by terrorist groups. Terrorist groups are more likely to be attracted to a country with economic prosperity. In the context of terrorism, that which is a strength is often perceived as a source of vulnerability. The idea that states are not equally vulnerable to terrorist threats is part of an ongoing discussion within the United States. In the US, less populated states have made the claim that they are entitled to as much federal protection from terrorism as the more populated states. This claim is made in the face of information that terrorist strikes are far more likely to occur in areas characterized by significant infrastructure capacity, something that is not characteristic of smaller and less populated states. This illustrates that countries, not unlike particular regions or states within countries such as the US, vary in terms of their risk positions. Each state has certain characteristics that combine in various ways with exposure to particular threats, resulting in specific and unequal vulnerabilities.

7 In addition to target attractiveness, risk positions are assessed in light of the stage at which a threat can occur. For some countries, threat of terrorism remains abstract, while for others, like Britain and the United States, the threat has been actualized. This will play into the ways in which threats are framed and addressed. These distinctions among states in terms of their risk positions pose challenges for collaborative efforts to deal with terrorist and other threats when the urgency of these threats varies substantially. As Erin Gibbs Van Brunschot and Leslie Kennedy note, risk position may be determined by assessing vulnerabilities in the face of various threats, balanced with an assessment of resources.6 While it is true that a levelling occurs when facing similar threats, the significance attributed to vulnerability and the consequences associated with it varies substantially.

8 In particular, vulnerability and the consequences of vulnerability to specific threats must be placed in the context of the resources available to address named threats. A more recent example highlighting the complications of risk positions is that of Somalia. In Somalia, where war has prevailed for many years and where al-Qaeda is presumed to be influential, the threat posed by terrorism is clearly less when considering the fact that Somalia is facing its worst drought in sixty years. With limited resources available to apply to terrorist threats, the risk associated with that particular type of vulnerability must be evaluated in light of resources available to address vulnerabilities. Resources may be social (including resources based on various group memberships or, in the case of states, particular political alliances), cultural (including characteristics that relate to determinations of status), and economic (money, trade, and physical reserves). When dealing with states, the realms of social and cultural capital include foreign policies. Foreign policy provides context to the risk positions that each of Britain, Canada, and Australia maintains and is briefly described next.

The Challenges Posed by Terrorism

9 Laura Sjoberg has addressed the place that the issue of risk position plays in the study of global politics through the lens of international relations.7 As she writes:

Sjoberg suggests that this confusion comes from an inability to take into account the different players in this new conflict using conventional approaches to international relations, particularly assuming that this is simply a "levels of analysis" problem rather than one that considers the interactions between agents and context, as we have alluded to in our discussion of risk positions.

10 Sjoberg further suggests, "in one iteration or another, the debate about "where" IRs [international relations] takes place and how to describe that place has received substantial scholarly attention consistently over the last four decades, a trend that is likely to continue in our globalizing world."9 The forces of globalization have upset the conventional views of the ways in which states operate to define and protect their interests, and this has been accelerated by the new challenges faced by terrorism, where the threats are not strictly national but may be religious or ideological and not confined to specific geographic locations. Sjoberg maintains, "in the wake of the war on terror, the global political world more generally has begun to explore the question of the importance of nontraditional actors, such as substate groups, transnational movements, and individual terrorists."10

11 Given this new order, there is a necessity:

So, it is with this mandate in mind that we address the ways in which the major actors in different countries assessed their risk positions relative to their own vulnerabilities and defined their own priorities in terms of security.

The Study Areas

Canadian Foreign Policy

12 In a report published in 1995, the Canadian government described its foreign policy as working toward three objectives: "The promotion of prosperity and employment; the protection of our security, within a stable global framework; and the projection of Canadian values and culture."12 The pursuit of these objectives would be facilitated by multilateralism, cooperation, and interdependencies. A second aspect that figures prominently in the report is the Canada-US relationship. In his 2004 report on national security and the government of Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, Joel Sokolsky describes the Canadian government’s approach as one of "realism" regarding Canada’s national interests.13 Sokolsky describes the Canadian government as operating on a "how much is just enough?" approach. Canada, according to Sokolsky, has attempted to carefully weigh the benefits that accrue given a particular contribution to world affairs. Aligning with and contributing to the United States’ effort has not necessarily been matched by a compatible degree of influence. It has not been the case that the more support one gives to the US, the more influence one has. Instead, Sokolsky notes, "it is clear that Washington intends to be the architect and leader of any coalition; and that, above all, allied contributions will not result in any influence."14 Canada’s position has tended to be that contributing more to US initiatives is no more likely to be effective than contributing less.

13 Like many other Canadian governments, rather than focus on military security, the Chrétien government focus on economic security was central to foreign policy. Trade missions, often referred to as "Team Canada," are the method of choice over troops and planes as the means of ensuring security. For the US, "(military) security ‘trumps’ economics," yet for Canada, Sokolsky explains that security is not distinguished from economics.15 The US expectation that Canada would put more dollars behind its military contradicts the realist orientation of the Canadian government and contrasts with the long-standing recognition by Canada that such spending has done little to influence American policy. The Canadian emphasis in the United Nations Security Council has ensured at least some recognition by the US of the concept of multilateralism – a concept that Canada has favoured as a means of ensuring "economic security."

14 Tom Keating explains that multilateralism invokes a set of normative and "positive values juxtaposing the more favourable image of multilateralism with what is widely portrayed as the less constructive option of unilateralism or, in Canada's specific circumstances, of a bilateral foreign policy attached to dominant and domineering powers."16 Political interests have at the same time been served by multilateralism, as it has "been used to deflect, corral or temper the imperial pressure of close allies — Great Britain in the past, the United States at present."17 Further, Keating notes that multilateralism has "implications for the authority and legitimacy of decisions taken, along with the efficacy of such decisions."18 While Canadian public support for multilateralism has been strong, support for multilateralism in the international arena has been more equivocal, with a willingness to be "at the table" tending to be based more on particular issues at hand than underlying support for a multilateral approach.

British Foreign Policy

15

. . . The countries and people of the world today are more interdependent than ever. That calls for an approach of integration. When I spoke about this issue in Chicago in 1999 and called it a doctrine of international community, people hesitated over what appeared to be Panglossian idealism.19

16 John Eatwell describes British foreign policy over the last fifty years as consisting of three central ingredients. First, Eatwell notes the efforts by the United States in the post-Second World War era, where the US effectively tried to undermine the British Empire. Prior to the war, Britain was the most formidable imperial power, but after the war Britain’s power declined substantially. The 1956 Suez crisis, when the US failed to support Britain’s position against Egypt, demonstrates the turning tides of power in global affairs. Despite this lack of support from the US, Eatwell notes a second ingredient to British foreign policy: the early recognition that to retain any degree of power and influence in world affairs was to remain close to the emerging power — the United States. Eatwell notes, "in Prime Minister Harold MacMillan's phrase, Britain was to play Greece to America's Rome, to be the wise diplomatic and philosophic advisor to the brash, new fledgling authority."20 The third ingredient was the cultivation of the "special relationship" that Britain had with the US, and the nurturing of the United States’ then-emphasis on multilateralism in the post-war period, and its relationship with Europe in particular.

17 This post-war tradition of ties between the US and Britain were further welded during the Thatcher era when Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher became very close to US President Ronald Reagan. During and after the events of 9/11, Britain’s prime minister, Tony Blair, attempted to sustain that legacy by maintaining the special relationship between Britain and the US, in the face of the US moving away from multilateralism in more recent times (two examples include the US rejection of the Kyoto Protocol and refusal to take part in the International Criminal Court). The special relationship is based, according to Samuel Azubuike, on the "policy of overt support for the US, moderated by private candour."21 Azubuike thus describes British foreign policy:

Below, we see evidence of this description in the speeches and statements emanating from the British prime minister’s office.

Australian Foreign Policy

18 Australian foreign policy has been described as fluctuating between two doctrines: "the great and powerful friends doctrine" and "Asian engagement." Prior to the Second World War, Australia’s major partner in trade and defense was Britain. Having been left on its own to defend itself against Japan during the war, post-1945, Australia’s close relationship with Britain was traded for a relationship with the United States. In 1952, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States signed the ANZUS Security Treaty, which marked the beginning of a new era in the relationship between the United States and Australia.23 For a period during the 1980s and 1990s, Australia’s foreign policy focused on the Asian connection, with both Australian Prime Ministers Bob Hawke and Paul Keating courting Australia’s Asian neighbors with respect to trade and security arrangements. The government of Prime Minister John Howard, in power during the events of 9/11, on the other hand, focused much more predominantly on Australia’s relationship with the United States.

19 One critic of Australian foreign policy suggests that "Australian history has largely been a valiant refusal to recognise Australian geography . . . Paul Keating and Gareth Evans both sought to re-align Australia as an Asian nation, rather than a European nation that was a victim of geographical circumstance."24 The rationale behind Asian engagement is that vulnerabilities specific to this geographic area were best reduced through the cooperation of neighbour states, rather than dependence on powers residing across oceans. Increasingly, Australia has come to view itself as a "‘middle power’: as one of a group of states with liberal-democratic traditions which could act in concert to influence the larger powers,"25 although the degree to which Australia influences the US versus the US influencing Australia is debatable. Despite the substantial weakening of the ANZUS treaty over the years prior to the turn of the century, in 2001, Howard invoked a little-used clause which essentially states that assistance will be forthcoming from member nations when one of the parties to the agreement comes under threat. Invoking this clause aligns with Daniel Lambach’s discussion of the discourse of securitization, whereby the issue being addressed "is no longer subject to the normal political process but instead becomes an urgent matter of survival."26

20 David McGraw elaborates on Australia’s foreign policy as being "realist" in terms of three specific characteristics. First, there has been an increasing willingness to expand and use military power to achieve foreign-policy goals. Second, Australia has emphasized the importance of maintaining relationships with specific allies — namely, the United States. Finally, during Howard’s reign as prime minister (1996-2007), there was growing scepticism regarding the efficacy of international institutions.27 In particular, the United Nations was increasingly viewed with disregard throughout Howard’s reign, so much so that in 2000 Australia initiated an inquiry into the UN demonstrating its rejection of a report criticizing the treatment of Australian aboriginals.

21 Having positioned the three countries in terms of their stated foreign policy, our task is now to examine how the events of 9/11 and the sudden emergence of the threat of global terror impacted the ways in which those most influential in articulating the risk positions of these respective countries defined their reaction to these threats and their views on security.

Method

22 The documents examined for this study include speeches, press releases, and statements. The specific material included from each prime minister depended upon the online availability of materials from each office. Speeches and press releases were used from the online material for Jean Chrétien; speeches, statements, and press releases for Tony Blair; and speeches, statements, and press releases from John Howard. Materials from both Prime Ministers Blair and Howard’s official websites were analyzed for a 28-month period from September 2001 to December 2003. Data for Prime Minister Chrétien was gathered for a 26-month period from September 2001 to October 2003.28

23 Our analysis began with an overview of each communication item. They were included in the analysis if any direct mention was made of the following key terms and phrases: "terrorism," "terrorist," "terror," and "September 11." Items were also included if they made reference (either directly or indirectly) to "(international) security." For the Canadian prime minister, there were 365 press releases and speeches issued during this period, 140 (38%) of which were included in this analysis. For the British prime minister, there were 87 statements and speeches during this period, 55 (63%) of which are included in this article. Finally, for the Australian prime minister, there were 270 communications, of which 194 (72%) were relevant for this analysis.

24 For our study, we undertake a variant of "ethnographic content analysis (ECA)" or, more simply, "qualitative document analysis," to reveal the themes that were prominent during this time frame.29 David Altheide explains that this method treats documents as symbolic representations, with the aim of analysis being to explain how it is that events are placed in context, with the goal of identifying "themes, frames and discourse." Here we "track discourse" and consider how various themes emerge over this initial time frame.

25 In their analysis of counter-terrorism campaigns, Arjun Chowdhury and Ronald Krebs note the importance of political discourse and the ways in which public speaking serves to frame topics in specific ways. They suggest that "political language constitutes the terrain of contestation, privileging particular courses of action and impeding others. The key concept is legitimation: the articulation before key audiences of publicly acceptable reasons justifying concrete actions and policy positions."30 As the leaders of their respective countries, prime ministers play a key role in framing threats, their significance, and what will be done to address them. Prime ministers must attempt to manoeuvre in ways that appreciate their relative risk positions, evaluating their unique context. As Chowdhury and Krebs observe, political leaders must also take into consideration dominant discourses (which they have contributed to), as well as understandings of the specific threat at hand.

26 We now turn to our analysis and the themes that emerge from our review of the prime ministers’ communications. Similar themes are discussed for each country. For Canada, our examination of the documents revealed four broad themes: threat; perpetrators; context; and Canada, the United States, and the Canada/US relationship. For Britain and Australia, we note three themes: threats, perpetrators, and context. Our consideration of these communications was not meant to generate mutually exclusive categories, and we did not attempt to classify speeches as primarily having to do with one or another theme. Rather, the goal was to uncover themes running throughout the materials. In our analyses, we discuss these emergent themes and how they relate to, and may be illustrative of, risk positions.

Canada: Prime Minister Jean Chrétien

Threat

27 Not unlike the other prime ministers, Jean Chrétien’s initial response to the events of 11 September was to describe the event as a global threat toward civilized society that must be addressed collectively. Although the danger posed to values of peace and security remains over the entire period examined, the risk that is described begins to change to a threat against the local and global economies and the trade relationship that Canada has with the United States.

28 Immediately following 11 September, Prime Minister Chrétien described it as "an offence against the freedom and rights of all civilized nations."31 The prime minister instantly asserted that, "this was not just an attack on the United States . . . The world has been attacked [and] [t]he world must respond."32 Repeated references to threats to "free and civilized nations" and "civilized values" suggest that uncivilized "evil" has arrived, compromising the civilized values of society and the values of peace, security, and freedom.

29 A year later, the prime minister refers not only to threats to values ("openness and freedom"), but also to the dangers posed to an "open world economy" (the importance of the trade relationship itself was noted early on). Specifically, 11 September posed "a threat to the largest trading relationship in the world" and threatened to "accelerate the global economic slowdown that had been apparent even before 9/11."33 In his response, the prime minister refers to the ability of the "Canadian economy to withstand the shock of 9/11 with extraordinary resilience" and with its "partnership with the United States . . . [to] ensure that [the] economy will not be held hostage to the threat of terror." The Smart Border Accord, implemented in December 2001, was created so that the Canada-US border would remain "open for business, but closed to security threats," again drawing attention to the importance of the economy. As time passed from the events of 11 September, the emphasis on economic issues grew increasingly prevalent.

30 There was much debate regarding the role that the United Nations would play in the "war on terrorism," with the focus shifting from terrorism itself to the underlying or root causes of terrorism. On the anniversary of 11 September in 2002, during a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) televised interview, the prime minister referred to the root causes of terrorism and was harshly criticized for his remarks. His commentary was interpreted to mean that the US must take responsibility for its role in causing the attacks. The prime minister subsequently issued a press release clarifying that his commentary had suggested a need for "all Western developed countries" to reflect on the growing divide between rich and poor states: "it is a gross misconstruction of his remarks to suggest that he was blaming the United States for the attacks."34 In another speech in February 2003, Chrétien again emphasized the importance of addressing underlying causes and challenges of our time such as poverty, trade, environmental degradation, infectious disease, and regional conflicts. "These issues of poverty, trade, and development are in the long run as important to a secure, stable world as addressing the immediate threats we face from terrorism."35 At a conference held in September 2003, two years post-9/11, it was suggested that dangers come from the "absence of inclusive and responsive political institutions, discontent, destabilization and violence" and the "growing disparity between the rich and poor."36

Perpetrators

31 The perpetrators of these terrorist acts were identified as clearly lacking in "civility," with the result that distinctions were drawn between "them" and "us." In the days immediately following 11 September, repeated and emotional references were made to the terrorists as depraved, cowardly, and evil. Not only were they evil, but they were named "cold-blooded killers" who lurk "in the shadows." The terrorists were repeatedly described as the uncivilized enemy (in contrast to the civilized "us") who are "willing, indeed anxious, to die in the commission of their crimes and to use innocent civilians as shields and as tools."37 In a press release, terrorist acts were labelled as the uncivilized behaviour of "blinkered extremists," intolerant to other points of view and are "enemies of a just and lasting peace."38

32 When the war in Iraq became increasingly likely, Chrétien referred to Saddam Hussein as "crazy," a "common danger" to the world community, and a "threat to peace in his region." Except in conjunction with terrorist attacks abroad, the number of references to terrorists decline, shifting the focus from the perpetration of terrorist acts to the role that Canada itself would play and the position that Canada would take with regard to troops representing Canada abroad; and Canada’s role in reconstruction efforts (considered further in the following section).

Context

33 In a speech on 15 October 2001, the prime minister states, "the scope of the threat that terror poses to our way of life has no parallel . . . on September 11, 2001, the world changed. A global struggle began. The first great struggle of the 21st century." Further, the point is made that it is the first great twenty-first-century struggle for justice: "a struggle for freedom and justice." The term "struggle" suggests that there is a possibility of "winning" or "losing" the "fight against terrorism." Yet as the term struggle diminishes, the phrase "new security environment" becomes increasingly prevalent. In the latter part of 2002, the prime minister notes that "a fundamental obligation of government is ensuring the security of our citizens." Then, in February 2003, the prime minister states, "We are faced with the harsh truth that our personal human security is intimately linked to the security of strangers living continents away. We have learned that great powers are not safe from danger. Wealth cannot buy safety. Military might is no guarantee of security." Late in 2002 and during the first months of 2003, the US was at the point of going to war against Iraq — without the support of Canada or the United Nations.

Canada, the United States, and the Canada/US Relationship

34 The idea that there is a "Canadian identity" was evident throughout the press releases and speeches, tending to centre on the view that there is a distinct set of Canadian values. The communications emphasize "values that are profoundly held by all Canadians: tolerance, democracy, internationalism, peace building, respect for human rights and the rule of the law."39 The prime minister also refers to being guided by key principles, including "mutual respect and accommodation; civility and peaceful resolution of conflict; and intercultural dialogue." Later in July 2002, the value of mutual responsibility among countries emerges: "We share a belief in freedom; in justice and fairness; and in solidarity and mutual responsibility."

35 Another theme highlighted makes comparisons between Canadians and Americans and the nature of the relationship between the two countries. Initially, Chrétien suggests that 11 September served to reaffirm the friendship between Canada and the US, a "friendship of unmatched respect, civility and openness. A global and hemispheric partnership based on shared values of freedom, justice and human dignity."40 The mutual understanding that is implied by this statement is reinforced in another statement on 8 April 2003, where Prime Minister Chrétien states, "The decision we made three weeks ago [not to go to war] was not an easy one at all. But we, as an independent country, make our own decisions based on our own principles." Moreover, the relationship between the US and Canada was "mature . . . strong and healthy," where nothing was broken and "nothing needs rebuilding." There are multiple references to "the largest trading relationship in the world" built "across the longest undefended border in the world" (undefended and thus apparently devoid of threat) and "unique in value and scope."41

36 Throughout the communications there are many references to Canada’s willingness and readiness to stand "shoulder-to-shoulder with all civilized states to defend freedom." "We have never been a bystander in the struggle for justice in the world. We will stand with Americans. As neighbours. As friends. As family. We will stand with our allies. We will do what we must to defeat terrorism."42 Part of the teamwork approach is the emphasis on multilateralism: "As you all know, Canada has always believed in multilateral approaches to global opportunities and problems. We believe in this multilateral cooperation, not as an ideology, but as a proven way to enhance security, and solve over-arching problems."43 Referring to the decision not to go to war against Iraq, the prime minister states: "We had a very difficult decision to make. We made it in accordance with our values. Our belief in the United States and multi-lateralism and we acted as an independent country."44

Britain: Prime Minister Tony Blair

37 A number of themes emerge in the speeches, statements, and press releases issued from the office of Prime Minister Tony Blair during the period September 2001 to December 2003. These include subjects such as: "our way of life;" "justice and humanitarianism;" "master statesman;" allies and friends; and global relations — Iraq, the Middle East, and Africa. Blair, not unlike Chrétien, emphasizes the "wickedness" of those responsible for the attacks in the temporally proximate stages following the attacks. Early on, Blair flags some of the issues that he will pursue as part of his agenda with regard to responding to terrorism, such as his emphasis on achieving peace in the Middle East, along with the early mention of drugs and the role that Afghanistan and the Taliban have played in the drug problem in Britain. Compared to Chrétien, Blair spent much time in his speeches emphasizing and justifying the role that he was playing with respect to the US. While we clearly see at least some degree of "standoffishness" regarding Chrétien’s position to the US, the vigour with which Blair is seen to partner with the US results in significant and numerous attempts at justifying that position — both internally and externally, especially with regard to Britain’s European neighbours. In the discussion that follows, the "evolution" of the framework that Blair employs over the course of the time period examined will be discussed.

Threats

39 Prime Minister Tony Blair, not unlike Prime Ministers Chrétien and Howard, describes the events of 11 September in particularly emotive and descriptive terms, clearly emphasizing that the attacks were not simply an attack on the US, but were an attack on all who hold democratic, liberal values: this was an attack on the Western world. In his statement of 14 September 2001, Blair describes the event as "hideous and foul," as "a tragedy of epoch making proportions," that "the heart of New York’s financial district was devastated, carnage, death and injury everywhere."46 He further describes the event as "the most appalling act of terrorism the world has ever seen" and as an "atrocity."47

40 In the immediate aftermath, before responsibility for the attacks had been identified, "we do not yet know the exact origin of this evil,"48 the perpetrators are described as a "machinery of terror"49 and as fanatics: "The people perpetrating [this event] wear the ultimate badge of the fanatic: they are prepared to commit suicide in pursuit of their beliefs." The identification of the Taliban as responsible, at least in part, for the 9/11 attacks becomes linked to Blair’s position that Afghanistan, under the direction of the Taliban, has been a central source of the drugs that cross Britain’s borders, describing the Taliban as "a regime founded on fear, and funded largely by drugs and crime." At this early stage, Blair signals that Bin Laden and the Taliban are not the only enemies, and that there are more out there.50 Blair’s initial position may be summed up as follows:

41 The above quote also hints at a significant theme that was common to all three prime ministers: the threat to the "way of life" of their "civilized" societies. Part of the focus on "way of life" appears premised on the "rightness" of that way of life: Blair, Chrétien, and Howard imply that what has been disturbed by these events are their countries’ right to a life of their choosing — a life that is "right" or acceptable according to their standards. Essentially, Blair’s position is that the terrorist attack on 11 September was an attack on all who hold democratic, liberal beliefs. As part of the civilized world against which this attack was perpetrated, a duty is owed by those who were attacked to defend these beliefs and this way of life.

Perpetrators

42 Beyond the values of freedom, democracy, tolerance, and respect, Blair placed emphasis on "justice" as part of the complement of values that Britain holds near and dear, both at home52 and on the world stage. Blair maintained from the start that those responsible for 11 September must be "brought to justice" and that justice requires that the perpetrators bear responsibility for and face the consequences of their actions. In the early months after September 11, Blair states: ". . . we must bring to justice those responsible. Rightly, President Bush and the US Government have proceeded with care. They did not lash out. They did not strike first and think afterwards. Their very deliberation is a measure of the seriousness of their intent."53

43 Throughout the period, the prime minister emphasized the importance of collaboration of effort to ensure that justice is done. At least part of the motivation behind addressing terrorism through collaboration is that working together serves everyone’s interests: "The terrible events of 11 September have made the case for engagement not isolationism as the only serious foreign policy on offer."54

44 Blair aligned with the US position that the options countries face are relatively few:

45 While collaboration is central to "serving justice" for Blair, there are other motivations behind collaboration that may be less directly connected to the issue of terrorism. Throughout the early portion of the period under examination, Blair emphasized that the collective response to Afghanistan must be both military and humanitarian. "It is justice, too, that makes our coalition as important on the humanitarian side as on the military."56 This theme continues during the invasion of Iraq and reflects the British position on accountability: wrongs must be made right and the "innocent," those who are caught in the crossfire, must be offered assistance. In his statement to the House of Commons on 13 November 2001, Blair states: "And finally I would simply say to the people of Afghanistan today, that this time we will not walk away from you. We have given commitments. We will honour those commitments, both on the humanitarian side and in terms of rebuilding Afghanistan. We are with you for the long term."

Context

46 In the discussion of British foreign policy above, we noted the historical "special relationship" that Britain has maintained with the United States over the past decades. While there is evidence of this relationship over the entire period, we see increasingly greater references to this relationship over time. In the first few months, not unlike Chrétien and Howard, Blair maintains, essentially, that standing together in the face of adversity is what friends do, and especially what the British do in times of strife:

The initial response to 11 September was indeed characterized by an apparent international and collective will to oust the Taliban from power in Afghanistan. However, as the situation in Iraq developed over the course of 2002, there was considerably less agreement, both within Britain and abroad, about "siding" with the United States and what many perceived as the unilateral approach being taken by the US.

47 Despite increasing opposition, Blair remained steadfast in his support of the United States. In a speech in April, 2002, to an American audience, Blair indicates:

48 In his first speech of 2003, Blair lists a number of strengths that he believes characterizes Britain:

49 In this same speech, Blair insists that Britain should remain the closest ally of the US and "influence them to continue broadening their agenda." This notion that Britain has some influence over the course of action that the US will take is emphasized in a speech delivered to the US Congress later that year (July 2003). Here, Blair indicates that the United States can "bequeath to this anxious world the light of liberty."60 The prime minister also describes Britain’s "understanding" of the position that "the average American" might consider himself to be in.

50 While Blair spends a significant amount of time describing and critiquing Britain’s relationship with Europe, at the same time he defends and justifies Britain’s relationship with the US to Europe. On the basis of Blair’s speeches and statements alone, one gleans a sense of the tension between Europe and Britain and the difficulties that Britain appears to have with its relationship to Europe (and vice versa). At a speech in November of 2001, Blair illustrates this tension:

51 Blair views the relationship that Britain has with both Europe and the US as one that might bridge one with the other: "Indeed the UK has a powerful role to play as a bridge between USA and Europe — we are economically strong and politically influential in both. Britain's friendship with the United States is an asset for our European partners. We want to be fully engaged in a united Europe, working with an internationalist USA."62 Clearly, Blair sees the advantage of solidarity with both Europe and the US as beneficial to Britain, reminiscent of Eatwell’s earlier observation about the utility of maintaining the "special relationship" that Britain has with the US.63

52 At the same time that Blair was elucidating the role that he hoped Britain would play in its triangulated relationship with Europe and the US, Blair indicated that he was not particularly happy with the role that Britain had played over the years with Europe. In a speech from November 2002, Blair details his position on why the relationship between Britain and Europe is as it is, focusing particularly on Britain’s historical inability to offer the leadership and diplomacy to Europe that it has with other countries and in other contexts:

While this particular example cites self-confidence as a potential problem, the statement ends on a note that clearly suggests Britain knows it brings to the table particular qualities that make it a leading power — particularly its relationship with the United States.

53 Blair faced a great deal of domestic opposition to the position taken regarding Iraq. It is in their approaches to Iraq that we see significant differences among the three prime ministers and their respective communications. Howard, for example, clearly supported the invasion of Iraq and faced substantial opposition at home. Blair, on the other hand, personally agreed with the invasion of Iraq and offered his country’s support, despite the clear divisions at home over this issue. On the other side of the table, Chrétien faced comparatively little criticism (except from the opposition party), when he decided against Canada’s support for the invasion of Iraq.

54 In support of his position, Blair draws on a "common stock" of knowledge that his audiences presumably shared with respect to Saddam Hussein’s governance of Iraq. As the quote above suggests, Blair suggests that reasonable people detest Hussein — his record in Iraq is evidence of his "evil ways": "with the Taliban gone, Saddam is unrivalled as the world's worst regime: brutal, dictatorial, with a wretched human rights record."65 Blair affirms that the connection between weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) and Saddam is not a new one and that Saddam has been in defiance of UN resolutions for eleven years: "occasionally debate on this issue seems to treat it almost as if it had suddenly arisen, coming out of nowhere on a whim, in the last few months of 2002. It is an 11 year history: a history of UN will flouted, lies told by Saddam about existence of his chemical, biological and nuclear weapons programmes, obstruction, defiance and denial."66 Blair suggests in unequivocal terms in this speech at the Lord Mayor’s banquet in November 2002 that terrorism and WMDs are "linked dangers." During his statement to parliament regarding a recently held NATO summit, Blair states:

55 Having made the decision to support the invasion of Iraq, Blair again makes reference to a lack of understanding among those in opposition that the central issue linking terrorism and weapons of mass destruction is the common threat both have to "our way of life."

56 From the very beginning, Blair emphasizes the importance he places on the Middle East peace talks and the importance of resuming those talks for the benefit of world peace:

Blair focuses on the Middle East because of his enduring belief that peace in the Middle East is vital to the stability of that region, and also vital to global stability. Blair links peace in the Middle East with terrorist threats, suggesting that if peace were established, it would "deprive the terrorists of an issue which they exploit for their own inhuman ends."69 To this point:

57 In addition to the concerns that Blair expresses regarding the Middle East, the subject of Africa is also a theme reiterated throughout the communications, particularly with respect to the threat that Africa may pose to the rest of the world if it continues to experience "grinding poverty, pandemic disease, a rash of failed states, where problems seldom leave their stain on one nation but spread to whole regions."71 While Blair connects the problems in Africa to terrorism, it is also clear that what has been occurring in Africa does not conform to Britain’s perception of itself as civilized:

58 Essentially, the idea is that by conforming to democratic values represented by the G8, Africa will be rewarded with greater resources. On the other hand, Blair suggests, "Africa, if left to decline, will become a breeding ground for extremism."73

59 As observed earlier, a major emphasis in Britain’s foreign policy has been a view of itself as statesman — as an able navigator of world politics. Collaborative efforts to address problems perceived as global readily fold into Britain’s historical perception of itself as world diplomat. References to Blair’s discussions with world leaders and commentary on other countries’ participation in collaborative efforts addressing terrorism are found throughout the material examined. Aside from the demonstration that leaders will hold court with Blair, we again note the (continuing) emphasis that Blair has placed on the Middle East peace process. On 4 October 2001, in his statement to parliament, Blair further details his work on the diplomatic front:

60 While the other prime ministers also refer to the need for collaboration, neither Chrétien nor Howard details the extent to which each has personally contacted other world leaders.

61 The above quote also signals the emphasis that Britain places on procedural diplomacy and their attempts to convince the United States to follow Britain’s lead with regard to its view of the role of the United Nations. In September 2002, Blair declares:

Australia: Prime Minister John Howard

62 In late 2001, Prime Minister John Howard of Australia was facing an election. The election campaign provided numerous occasions for the prime minister to reflect on the events of 11 September. The number of speaking engagements by Howard during the fall of 2001 substantially exceeds either Prime Ministers Blair’s or Chrétien’s.

63 As with his North American and European counterparts, many of Howard’s speeches reflected a similar emphasis on the terrorist attacks as being a threat to "our way of life" and a direct attack on democratic society the world over. Early in the period, Howard links the issues of immigration, asylum seeking, and border security — all perennial issues for Australia — with terrorism. Compared with both Canada and Britain during this initial time frame (2001-2003), Australia was unique in that it was the only one of the three countries to have been targeted by terrorist attacks. Although the attack in Bali in October 2002 was not on Australian soil, the terrorist attack specifically targeted the Australian embassy and a night club whose clientele was substantially young Australians.

Threats

64 Howard was on the campaign trail vying for re-election in November 2001. These campaign events provided ample opportunity to both instil and remind Australians of their patriotism. For example, Howard notes:

65 Not only does Howard depict Australians as being most effective in difficult circumstances, but he further suggests that the personality of Australia and of Australians would not tolerate letting down one’s friends in their time of need, or letting each other down. References to being ‘mates’ and mateship were prevalent throughout this period: "That we have to hang onto those values which the terrorists themselves would seek to tear down. That we must extend the hand of friendship and the hand of Australian mateship to people of all religions and of all ethnic backgrounds."76 Elsewhere he states: "It has reminded us of the great verity of Australian life that in crisis we are all mates together."77 Finally he declares:

The readiness to stand by one’s mates is also prevalent in how the Australian prime minister describes the motivation behind his support of US President Bush and the relationship between their respective countries.

Perpetrators

66 Not unlike his prime ministerial peers, Chrétien and Blair, on a number of occasions Howard remarked that those who would commit acts of terrorism are not "like us." At the same time, Howard makes reference to who Australians are — and it appears that they are not like anyone else, either. There are many references throughout the communications to a rather keen sense of the hardship that Australians have historically borne and the challenges that have faced them over the years — as well as references to overcoming adversity.

67 At the turn of the twenty-first century, Australia was again facing the perennial question of immigration and how decisions regarding who might be allowed into the country were being made — a frequent criticism of the Howard government. One particular location that was cause for much concern is Ashmore Reef, located off the northwest coast of Australia. Many would-be immigrants to Australia are left at Ashmore Reef to eventually find their way to the Australian coast. While needing rescue, often those who do land on Australian shores are considered as having entered Australia illegally and are considered criminal. Access and border security were seen as significant issues with respect to terrorism, as it was initially believed that the terrorists who participated in 9/11 had made their way to the United States through Canada (later proven to be mistaken). The issue of illegal immigration is raised repeatedly with regard to border security and the right of a country to determine who was allowed in and who was not.

68 National security is therefore about a proper response to terrorism. It’s also about having a far sighted, strong, well thought out defence policy. It is also about having an uncompromising view about the fundamental right of this country to protect its borders. It’s about this nation saying to the world we are a generous open hearted people taking more refugees on a per capita basis than any nation except Canada, we have a proud record of welcoming people from 140 different nations. But we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come . . . We will be compassionate, we will save lives, we will care for people but we will decide and nobody else who comes to this country.80

69 We note references to Australia’s history as symbolic of the understanding that Australians have of immigration and their embrace of immigrants. Howard further notes that the criticisms that Australia has faced are unfair, as Australia has acted as it has due to legal issues and not to discrimination.

This is not a conflict between Christianity and Judaism on the one hand and Islam on the other. It’s a conflict between good and evil and all who oppose evil and terrorism are entitled to our friendship and our embrace.83

70 The emphasis on the threat that immigrants pose is associated with what Howard and others have defined as a new form of threat often tied to border security — yet the challenges of immigration are longstanding. As is the challenge of good and evil, border security appears as a reasonable placeholder for issues that may be longer standing than the new threat of terrorism that has emerged.

This quote suggests that while the threat may be somewhat new, the response of Australia and other countries must be to address the threat directly — confront and defeat it.

71 The emphasis on camaraderie and facing together the challenges that threats pose remains an important theme (connected with "mateship" above):

72 At the same time that borders are seemingly defined as more worthy of careful watch in terms of who is let in to Australia, concern was also expressed about the whereabouts of Australian youth and their ability to freely travel. The mobility of Australian youth came to the forefront after the Bali bombings in October 2002 which had targeted a nightclub frequented by young Australian travellers (88 of the 204 who died were from Australia). The permeability of (other) borders is of central importance to Australians whose global location is somewhat remote.

Context

74 Geographically speaking, both Australia and Britain are far removed from the United States, yet each country has attempted to maintain close relationships with the US although for somewhat different reasons. Britain has tended to maintain its close relationship with the US because of the increasingly important role that the US has played on the world stage over the course of the last half century. On the other hand, as the quote above suggests, Howard believes that Australia feels a historical debt is owed to the US given the role that they played in protecting Australian interests against Japanese expansionism during the Second World War. Friendships are cemented, it appears, by debts owed: "Some have seen what we have done in recent times as, in part, a repayment of debt that we owe for the help and assistance that was given."88

75 While the relationship between Australia and the United States may be supported by the framing of debt owed by Australia due to the military support provided by the US, the relationship between Australia and Britain is central to how Australia defines itself. The hardship that early Australian settlers experienced was due, in part, to the forced immigration Britain practiced during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by deporting those convicted of crimes. For many others, however, the lure of gold had brought thousands from Britain to Australia. Howard notes the ties that endure between the two regions:

The Commonwealth binds all three countries, as noted earlier, and while each country may act as a separate entity, membership in the Commonwealth implies similarity of position on many issues, politics notwithstanding.

In November 2002, President Bush went to the United Nations General Assembly and asked the Security Council to endorse taking action against Iraq that would reveal WMDs. While unanimously passed by the Security Council, Howard buttressed his decision to support the Iraq invasion on a number of occasions since this decision was not consistently supported by the Australian public. Howard draws on the fact that the events of 11 September took all by surprise, and that Australians could understand the new urgency with which issues such as WMDs were being investigated. Further, Iraq had used their weapons before.

Summary: Three states’ views of the terrorism threat

76 The speeches, statements, and press releases reviewed above suggest that each prime minister dealt with the events of 11 September in diverse, as well as similar ways — the polyvalent threat of terrorism is framed according to the risk positions that each country inhabits. As suggested above, a number of factors contribute to how risk is assessed, and therefore the meanings attributed to that which is identified as threatening differ. Canada, for example, shares a major trade relationship with the US and is physically proximate to the US, which has resulted in an extensive history, making it seem reasonable that maintenance of Canada’s relationship with the US would be prioritized. In the international arena, as elsewhere, getting along well with one’s neighbours is a worthy goal. At the same time, we noted the early tension with respect to being perceived as too similar to the US, and the attempt to build a separate identity. Again, distinct identities may have been underscored when it came to the invasion of Iraq. Foreign policy has played a role in how it is that countries define their risks and, as we shall see, what they are willing to do about the risks faced and whether they are shared.

77 The position of Britain is again different from that of Canada or Australia. Throughout the communications we note the emphasis that the prime minister places on Britain’s view of itself as "international statesman." In this early period, the threat was defined as a threat to "our way of life," not unlike the other two countries, but the means of dealing with this threat seem to hinge on the perceived ability of Britain to capitalize on its view of itself as statesman. While this approach may seem a distant cousin to Britain’s former imperialist tendencies, it seems clear that Britain positioned itself as a key player in managing and helping to strategize against this global threat.94

78 Australia’s position is again unique and draws heavily on acknowledging that the US, one of its "mates," has been threatened and therefore a duty is owed to help one’s mate protect and defend itself. Australia’s obligation is historical and based on the US having come to Australia’s aid during the Second World War. The attitude of Australia’s prime minister seems less one of leading the charge against terrorism than standing "shoulder to shoulder" with those who are mates and against those who might threaten that relationship between the two countries. At the same time that mateship comes to the fore, we note that the issue of terrorism provides an opportunity for the prime minister to attach the issue of immigration, a longstanding concern in Australia, to the issue of border protection against the more recent threat of terrorism.

79 We suggested that risk positions are both a result of perceived (and real) vulnerabilities, often intimately tied to the various forms of social, economic, and political capital that states bring to bear. It is true that specific political leaders may place selected emphases on certain threats, as well as selected interpretations of these threats over others. At the same time, because it is the office of the prime minister that is the focus here, the communications emanating from each prime minister’s office ensures appropriate messaging.95 We now turn to an examination of whether the talk that prevailed appears to have set the course for specific types of legislation and/or approaches to terrorism and security in each country.

Legislation and Events

80 In the aftermath of 9/11 there was much talk in these countries of the need for global controls, primarily as these related to the issue of border security and the ways in which countries might be able to prevent infiltration by terrorist groups. The border lockdown seemed to contradict the well-known fact that terrorist groups do not come exclusively from outside a country’s borders; in fact, the largest proportion of terrorist events against each of these countries are "domestic," or those that come from right- and left-wing political, religious, and environmental groups found within these states’ borders. Still, the desire to fortify the borders and demonstrate collective will to fight terrorism was strong.

81 In the discussion that follows, we focus on the major pieces of legislation that passed in each of the three countries that were written to address terrorist threat.

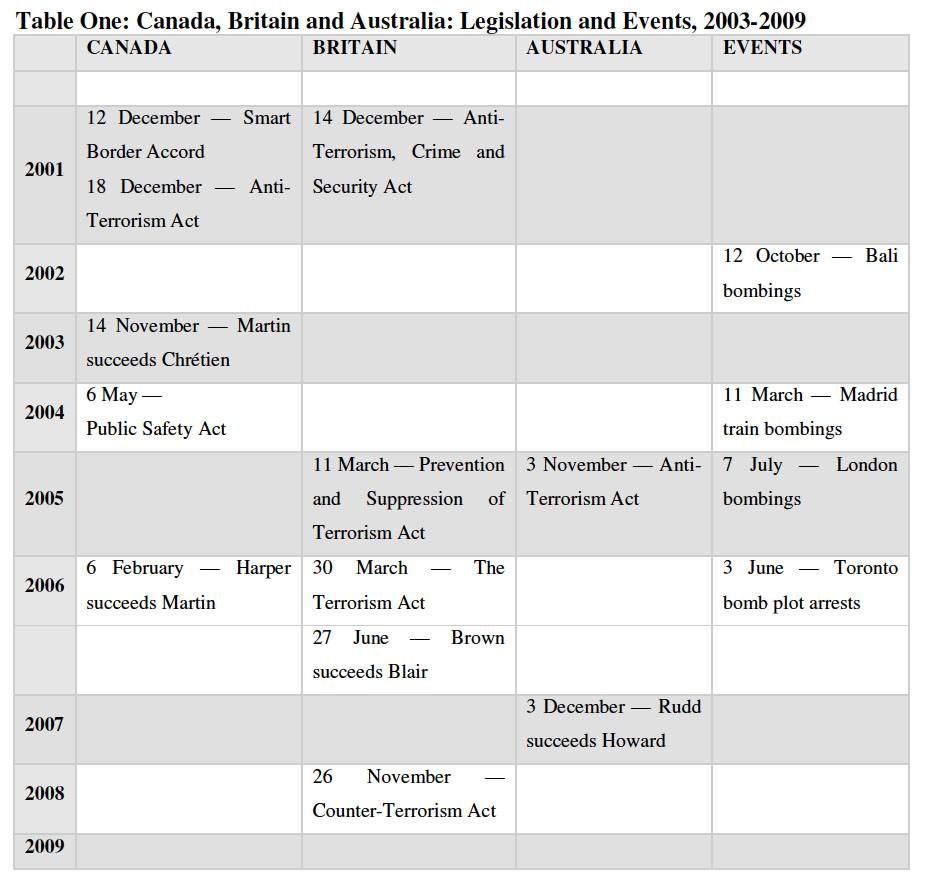

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1Canada

a. The Anti-Terrorism Act 2001

82 Prime Minister Jean Chrétien wasted little time bringing forward the Anti-Terrorism Act (Bills C-36 and C-42) passed by the House of Commons on 18 December 2001. The act was fast-tracked and received majority support after the Liberal Party headed by Chrétien used its majority to curtail debate and pass the act. Essentially, the act made it a crime to:

- "Knowingly collect or provide funds, either directly or indirectly, in order to carry out terrorist crimes.

- Knowingly participate in, contribute to or facilitate the activities of a terrorist group.

- Instruct anyone to carry out a terrorist act or an activity on behalf of a terrorist group (a "leadership" offence).

- Knowingly harbour or conceal a terrorist."96

The much-curtailed debate had focussed on the range of the measures contained within the act, such as providing the police with broad powers, including the arrest and detainment of individuals for up to 72 hours on suspicion of terrorist involvement without laying charges.97 Further, the act allowed for preventive arrest, at the same time it allowed for electronic surveillance, and for the designation of a group as a terrorist group. Finally, another controversial aspect of the act was the inclusion of the right of judges to compel witnesses to testify in secret about past associations or plans for pending acts, or risk going to jail for refusing to comply.

83 Given the debate surrounding the act, the government agreed at the time to call for a formal review in five years’ time. Bill S-3 reinstated particular clauses of the Anti-Terrorism Act that expired under the sunset clause in 2007. The revisions are similar to the original provisions, and specifically contain:

- "provisions to bring individuals who may have information about a terrorism offence before a judge for an investigative hearing,

- and provisions dealing with recognizance with conditions, including preventive arrest to avert a potential terrorist attack.

- The bill also:

- contains a 5-year sunset clause;

- requires that the Attorney General and the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness to report annually on their opinion together with reasons as to whether these provisions should be maintained;

- incorporates other technical amendments."98

b. The Smart Border Accord 2001

84 Much has been made of the fact that Canada and the United States share the world’s longest undefended border. In the very early stages post-9/11, both countries signed the Smart Border Accord designed to begin addressing the doubts that emerged over what had essentially been a free-flow across the border. Often referred to as the "30-point plan," this agreement was meant to facilitate the flow of low-risk travellers and secure the border through:

85 The outcome of this legislation has been a number of incremental changes to the ways in which the US and Canada approach border security, with a view to making legislation fit the border-crossing requirements in both directions. While the Smart Border Accord is simply an agreement to work together, in a report prepared by a provincial Canadian premier and a United States governor in 2002, Gary Doer and William Janklow, it is noted that agreeing on the specifics of harmonization efforts is impeded by: "regulatory differences, legislative restrictions, political complexities, and a plethora of often-uncoordinated agencies involved within the fabric of each government [which] can hinder progress in implementing the Accord."100

Britain

a. Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001

86 Before the end of 2001, Britain had passed its Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act. Not unlike Canada’s Anti-Terrorism Act, the British act involved an expansion of police powers, as well as sharing information among agencies and special security measures for airports and other facilities. The controversial component was Part Four of the Act that allowed for the indefinite detainment of those suspected of terrorist activity specifically associated with Al-Qaeda, contradicting the European Convention on Human Rights which essentially specifies that the legality of one’s arrest will be determined within a reasonable amount of time. Because of the difficulties associated with this part of the act, the fact that it was emergency legislation, as well as Part Three which allowed for the disclosure of information about specific individuals from public bodies regarding their own information functions, the act was scheduled for independent review two years after it was passed by parliament.101

87 The review, although recommending immediate changes to the act, was renewed without debate. Similarly, in 2004, the act was again renewed. In 2004, it was ruled that Part Four violated the Human Rights Act and that the state of emergency could be lifted. All of those held under the provisions of Part Four were released.

b. Prevention and Suppression of Terrorism Act 2005

88 The problems associated with the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act were addressed to some degree by the Prevention and Suppression of Terrorism Act in March 2005. In particular, Part Four was addressed by instituting control orders:

89 "Control orders" may be defined as tailored obligations that are placed on individuals identified as terrorist risks, including specifying where the individual can live, work, who he or she may speak with, travel to (or travel at all — passports may be confiscated), to name a few. The control orders have been highly criticized, primarily because they do not protect the individual against double jeopardy; even if the individual is able to appeal a decision, the Home Secretary may simply place another control order on the individual, starting the entire process over again. Over the past few years, there have been some adjustments to certain elements of the control order — for example, curfews for 12-14 hours are acceptable, but 18-hour curfews are considered a deprivation of liberty — and various judges have determined that the specifications of some control orders contravened the European Convention on Human Rights. The specifications of the control orders continue to be problematic. When the act was introduced in 2005, it contained a sunset clause suggesting review in one year’s time. The first review occurred in March 2006, approximately nine months after the London bombings, and has been renewed every year since.

c. Counter-Terrorism Act 2008

90 The Counter-Terrorism Act of 2008 was the first legislation addressing terrorism under the leadership of new Prime Minister Gordon Brown, who had pledged in his Queen’s speech that fighting terrorism would be central to his agenda. This legislation did not replace the previous act, but was meant to add further powers and provisions to the fight against terrorism. Although the bill was initially introduced in 2007, it failed to receive support without undergoing a number of amendments, especially those relating to intercept devices and the limits to be placed on intercepted communications. Eventually, a number of concessions were made due to the difficulties the bill was facing in the House of Commons (despite public support largely in favour of the bill).103 Central elements of the act that eventually passed in November 2008 include:

- "a provision to allow the pre-charge detention of terrorist suspects to be extended from 28 days to 42 days in certain circumstances

- changes to enable the post-charge questioning of terrorist suspects and the drawing of adverse inferences from silence

- imposing requirements on people convicted of terrorist offences to let authorities know where they are living and any changes to their circumstances

- enhanced sentencing of offenders who commit offences with a terrorist connection

- provision for inquests and inquiries to be heard without a jury."104

Australia

a. The Anti-Terrorism Acts 2004

The Australian government has remained vigilant in its efforts to address terrorism. Many acts were passed between 2001 and 2004, most of which were amendments to strengthen and solidify the means by which existing acts could better address terrorism. For example, in 2002 acts were passed amending the Criminal Code: one amendment modernized treason offences, as well as creating offences that link to membership in terrorist organizations. Another example was an amendment to the Criminal Code making it an "offence to place bombs or other lethal devices in prescribed places with the intention of causing death or serious harm or causing extensive destruction which would cause major economic loss."105 In 2002, the Crimes Act (1914) was amended to allow for the forensic identification of the victims of the Bali bombings.91 In 2004, three Anti-Terrorism Acts passed that were geared toward amending existing legislation. These amendments included:

- reinforcing the capability of law enforcement, as well as setting minimum non-parole periods and fortifying bail conditions [amending the Crimes Act 1914]

- making it a crime to intentionally associate with those known to be members of terrorist organizations [amending the Criminal Code Act 1995]

- strengthening the counter-terrorism legal framework [including amendments to the Passports Act 1938, the Australian Intelligence Security Act 1979, and the Crimes Act 1914].

b. The Australian Anti-Terrorism Act (No. 2) 2005

92 Further amendments were made to existing legislation under the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2005 that expanded the abilities of law enforcement to use preventative detention measures, control orders, and clarified sedition offences. Beyond this, the 2005 Act also included provisions for:

- listing organizations that advocate terrorist acts as terrorist organizations

- extending the power of police to "stop, question and search" on reasonable grounds those they believe are involved in terrorist activity

- facilitating justifiable access by law enforcement to obtain various records, such as financial, travel, work, and residential records

- enabling law enforcement to demand documents and ask questions of those aircraft or ship operators which may be relevant to terrorist activity

- strengthening offences regarding the financing of terrorism and providing misleading information.106

93 There has been criticism of the changes proposed to Australian law, primarily with respect to the lack of oversight and the difficulties associated with control orders. Unlike Britain and its Anti-Terrorism Act, there is no independent oversight body in Australia to conduct judicial reviews of their act. As Christopher Michealsen notes, "in general, Australia's antiterrorism legislation does not empower any parliamentary committee or independent body to oversee or review the operation, effectiveness and implications of the respective laws per se."107

94 Our review of the legislation created by Canada, Britain, and Australia provides us with further information regarding risk positions and how these may be reflected in the legislation that has followed the framing of terrorist threats by each of these countries. In the case of Canada, we note that the Anti-Terrorism Act supports prime ministerial talk which condemns activities associated with terrorism. The other major piece of legislation, the Smart Border Accord, was specifically created to protect and maintain the trade relationship between Canada and the US. The speed of the legislation put in place in Britain, not unlike Canada, along with immediate amendments to existing legislation by Australia, suggests swift condemnation of those involved in terrorist activities. Jason Glynos and David Howarth remind us, however, that it may be tempting to overplay the legislative actions of these countries as being somewhat unique, without taking into consideration a "wider net of social practices and logics." The wider net of social practices during the immediate post-9/11 era appeared to have been characterized by a "politics of fear." Public talk and legislative outcomes can both be seen as a means by which these countries demonstrated their positions as "team players" in the fight against terrorism, as well as helping to create and reinforce identities as being on the "right team" when it comes to terrorism.

CONCLUSION

95 The ways in which Canada, Britain, and Australia communicated the events of 11 September 2001 reveal a culmination of historic and current factors. While there were other significant terrorist events prior to that time, this event marks the largest foreign attack on US soil since Pearl Harbor. The risk positions of each of these countries were varied: Canada, situated next-door to the US, recognized the significant trade relationship with the US but also emphasized independence and free will. Britain and Australia, each literally oceans away from where the 9/11 attacks took place, took pains to ensure that they were seen by the US as "brothers in arms." Risk positions are complicated, involving history, proximity, perceptions of the future, and resources. Resources come in a variety of forms: from the foreign policies that countries maintain, to their physical and monetary amenities, to their histories with other international players.

96 Of particular note is the degree to which risk positions and actions undertaken in the name of fighting particular threats involve various forms of interaction. Canada’s approach to international relations, for example, is not created in a vacuum but rather is dependent not only on its own resources, but also on the weight of historical and present interactions with its neighbors and the world community. The close proximity to the US has resulted in a unique relationship both with the US and with other states globally. Nils Orvik suggests that Canada has practiced "defense against help" with the United States.108 This means that Canada has practiced some form of neutrality or non-alignment with others thereby defaulting to a position where the larger country sees the smaller country as no threat. We note the attention paid by Canada to appearing distinct from its immediate neighbor, but with the recognition that its relationship with the US is central to Canada’s economy — effectively limiting, to a great extent, how independent Canada can afford to be. As with the other countries, the history of relationships among foreign players has a large impact on their willingness to come together in the face of threat. At the same time, the issue of terrorism may also serve to unite seemingly unlikely partners against a common enemy.