Articles

The Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflicts:

The Israeli-Palestinian Case

ABSTRACT

Asymmetry is considered one of the most relevant features in today’s conflicts. In this article we address one particular type of asymmetry — structural asymmetry. After introducing the main characteristics and different phases of these types of conflicts, i.e. conscientization, confrontation, negotiation, and sustainable peace, we address the specificity of the Israeli-Palestinian case presented here as a typical case of a structurally asymmetric conflict. The aim is to explain why, despite the many negotiation phases this conflict has been through, none has ever led to a sustainable peace. On the contrary, each negotiation has brought on yet another confrontation phase, in a never-ending series of loops. The strong imbalance between the two sides and the scarce reciprocal conflict awareness represent the two main reasons for explaining this pattern.

INTRODUCTION

1 With the end of the Cold War and the emergence of intra-state and inter-ethnic wars, the concept of "asymmetric" conflict has come to the fore in conflict theory. In fact, a significant number of today's conflicts are characterized by strong asymmetries.

2 The term "asymmetric conflict" is used in different ways to denote situations that, although sharing some commonalities, are often quite diverse. Although we know that any attempt to frame social phenomena in rigid taxonomies is disputable, for the sake of clarity and to provide an analytical framework for studying these conflicts, we propose to distinguish among three types of asymmetry: power asymmetry, strategic asymmetry, and structural asymmetry. The boundary between these different types of asymmetry is often quite blurred, and in most cases more than one type is present at the same time: yet, this distinction can be helpful in analyzing and understanding the development of a conflict. In many cases, the asymmetry of the parties in the conflict — or rather their perception of this asymmetry — is crucial in explaining their different behaviors and attitudes. Here we are categorizing types of asymmetry, not types of conflict: a conflict most often shares more than one type of asymmetry, possibly with different degrees of intensity.

3 Power asymmetry occurs whenever a strong imbalance in power exists; a kind of asymmetry quite common in conflicts. Often this type of asymmetry occurs at the same time as the other types of asymmetry. However, there are conflicts that are characterized almost uniquely by power asymmetry.1 This is the case, for instance, of the conflicts studied by Thazha V. Paul,2 who analyses the conditions under which weaker states initiate conflict. An extreme but clear example of power asymmetric conflict was the First Gulf War between a powerful coalition led by the US on the one side and Iraq alone on the other. The US and Iraq were both states with recognized governments, a regular army, and a political body capable of taking decisions and implementing them. From these points of view, the situation was rather balanced: the asymmetry was in the huge difference in military force, a matter of quantity rather than of quality.

4 Strategic asymmetry occurs when the two parties are asymmetric in their tactical and/or strategic approach to the conflict. This type of asymmetry usually also includes a strong imbalance in power. Typical examples are guerrilla wars and terrorism. These types of war are certainly not new:3 in modern times, guerrilla war dates back to the American Revolution. In spite of the many studies on asymmetric warfare, the strategic thinking of most militaries in Western countries is still based mainly on "technology" and "firepower," while insurgent or terrorist combatants are composed of decentralized cells capable of blending into the population at will.4 This fact is linked with the development of information technologies: "the information revolution is favoring and strengthening network forms of organization, often giving them an advantage over hierarchical forms."5 Typical is the case of the so-called "war on terror." Some terrorist organizations behave as a network in which each node corresponds to a small group of militants, with multiple horizontal inter-node connections.6 Strategic asymmetry is studied in detail by Ivan Arreguín-Toft.7

5 Structural asymmetry arises when there is a strong imbalance in status between the parties. At the root of these conflicts is the very structure of the relationship between the adversaries. It is this that makes this type of asymmetry quite peculiar and different from the others. In a conflict characterized by structural asymmetry the real object of the fight is to change the structure of relations between the opponents. Usually one of the parties seeks to alter it, while the other struggles to avoid any change. Sometimes one of the parties is a governmental institution and the other a non-state organization, but this is not always the case. As an example, structural asymmetry is what characterizes most of the "conflicts over access and control over land [which] have been endemic in the agrarian societies of the past and still loom large in a world in which 45% of the population make their living directly from the land."8 In these cases the two rivals are both non-state organizations, although often one enjoys the support of governmental institutions. Other typical cases are decolonization conflicts. Here the relationship between the colonizers and the colonized is at the center of the conflict. In this type of conflict one of the parties is a state and the other a non-state actor, such as a political organization or liberation movement.

6 A relevant feature that differentiates the three types of asymmetries concerns their behavior over time. Power asymmetry is quite static and unlikely to change swiftly: a weak country cannot become strong overnight. Strategic asymmetry is a matter of choice, depending on the actors' decisions; in principle, a switch in strategy can be made in a relatively short time. Still, as Arreguín-Toft observes, "the actors [ . . . ] are not entirely free to choose an ideal strategy."9 Finally, structural asymmetry presents the most dynamic behavior. The structure of relations between the parties and their characteristics can change dramatically during the development of the conflict. For example, in a conflict over landownership, at a certain point the landless peasant movements can obtain the approval of a land reform law which changes the legislative framework, but does not end the struggle. The issue at stake is now the concrete application of the reform. The asymmetry is still present although now with a diminished imbalance. This is what happened in Brazil with the 1985 National Agrarian Reform Plan.

7 According to Arreguin-Toft, "Although asymmetric conflicts are the most common type of conflict, they are among the least studied by international relations scholars."10 This is particularly true for conflicts whose most relevant asymmetry is structural. In fact, conflicts of this type have always been present and have been widely studied, but rarely has structural asymmetry been used as a theoretical framework to analyze their features and dynamics. A remarkable exception is an early article by Johan Galtung, whose insights on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are still of great value.11

8 In this article, we will first present the main features that characterize structurally asymmetric conflicts and the dynamics that are expected to unfold in these conflicts. Then, these concepts will be used to cast new light on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a typical example of a structurally asymmetric conflict. Finally, a section is dedicated to the looping negotiation-confrontation cycle that has characterized the conflict since the failure of the Oslo peace process.

Structurally Asymmetric Conflicts: A Definition

9 Although different types of asymmetry usually coexist within the same conflict, in most cases it is possible to single out one type of asymmetry as the one that best characterizes the conflict. For instance, all the conflicts studied by Paul12 can be best characterized as power asymmetric conflicts, while the ones analyzed by Arreguín-Toft13 can be denoted as strategically asymmetric conflicts, without downplaying the presence of relevant power asymmetries.

10 In this section we will analyze the main characteristics of structurally asymmetric conflicts in which "the root of the conflict lies not in particular issues or interests that may divide the parties, but in the very structure of whom they are and the relationship between them."14 This definition applies to a variety of conflicts, each different from the other and bearing its own peculiarities and characteristics.

11 Typical examples of structurally asymmetric conflicts are decolonization conflicts where the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized is at the root of the conflict. It is a relationship characterized by a large power imbalance, with the consequence that the dominated usually resort to guerrilla warfare or to terrorism.15

12 While in the decolonization conflicts the two actors are usually a state and a non-state organization, this is not always the case with other relevant structurally asymmetric conflicts, such as the rural conflicts for access to land present in many Third World countries16 or the intra-national conflicts involving ethno-nationalities.17 In the former case peasants who challenge landlords often are poorly organized with scant support from political or judiciary structures. The landowners are much better organized, with powerful economic means, and often count on the support of strong political forces, the judiciary, and the police. In the latter case, most often the confrontation is between a community controlling the political and administrative system on the one side, and one or more communities (often, but not always, minorities) with limited or no political or military power, seeking recognition, identity, and security on the other side.

13 Finally, a conflict where the structural asymmetry is self-evident is gender conflict rooted in the culture of a society, its economic structure, and its history. Diana Francis uses it as a paradigm of structurally asymmetric conflicts.18

14 The structural type of asymmetry has been studied in detail within the context of intra-state and ethnonationalistic struggles by Christopher Mitchell. He enumerates a number of key dimensions that characterize structural asymmetry:19

- Legal asymmetry focuses on the legal status of the parties. Typical is the case in which one of the parties is the government of a state and the other an ethnic minority whose rights are denied — or undermined — by the government (for example, Turkey and the Kurdish minority). This type of asymmetry affects the parties in their perception of the conflict and the strategies available to them.

- Access involves the ability of the parties to have their concerns and goals put onto the political agenda. Minority communities often have little capacity to voice their concerns and have them dealt with. An example is South Africa, where the black majority had no access to the political agenda, due to the apartheid enforced by the white minority.

- Salience of goals is an "important way in which parties in protracted conflicts are likely to be highly asymmetric, especially in the early stages of any cycle of conflict, in the importance that the adversaries attach to the issues in the conflict."20 For example, compared to the American colonizers, the native inhabitants of North America had a less clear perception of the main issues of the conflict, the exclusive possession of the land.

- Survivability. It is not rare that what is at stake is the very existence of one (or both) of the conflicting parties, or at least that this is the perception they have (and often perceptions are not less relevant than concrete facts). An example is the decade-long war waged in Nepal by the Maoist guerrillas against the government. Here the monarchy itself was at stake, and in May 2008, the peace resolution did eventually lead to the abolition of the monarchy.

- Intra-party cohesion. It may happen that one of the adversaries is more cohesive and better organized than the other. Under these circumstances the rival organization could contend for the allegiance of a constituency in one or both parties. As an example, inter-fighting in the rebel camp in Darfur weakened their resistance against the Sudanese government and derailed the Darfur Peace Agreement signed in May 2006 by only one faction of the Sudan Liberation Army/Movement.

- Leadership insecurity "concerns how secure the leaderships of the two sides are likely to be and what effect symmetric or asymmetric levels of insecurity might have on the conflict, particularly on any termination process."21 An example is Kosovo where the non-violent struggle led by the LDK (Democratic League of Kosovo) leader Ibrahim Rugova lost strength due to growing support for the armed resistance of the UÇK (Kosovo Liberation Army), leading to increasing levels of violence.

The Dynamics of Structurally Asymmetric Conflicts

15 Having reviewed the main characteristics of structurally asymmetric conflicts, we will now focus on the dynamics of such conflicts. The type of relationship that is at the root of the conflict can be defined as a domination relationship. Usually there is a dominator and a dominated. These terms are used in a neutral and value-free sense. In saying that someone is in the dominator position, we refer to the objective fact that he/she belongs to the stronger side in the relationship without necessarily attaching to this fact a value or an ethical judgment. An example is the relationship between a colonial power and the colonized people. The individual citizens of the colonial state might be in favor of the self-determination of the colonized population, but from an objective (structural) point of view, they are part of the dominator side and from this they benefit.

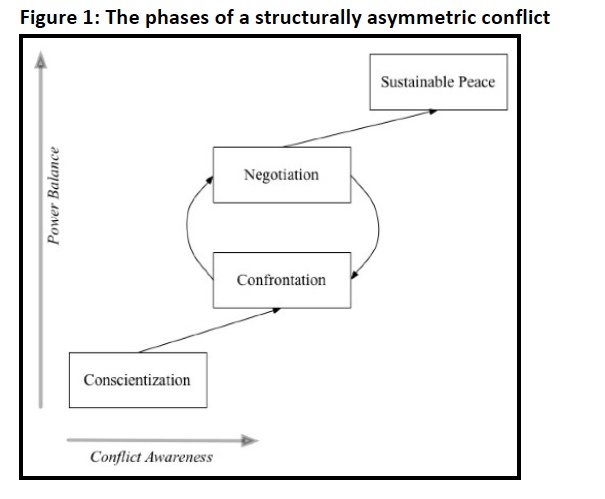

16 Since the domination relationship is a contradiction,22 it is this relationship that needs to be changed substantially. According to Adam Curle and John Lederach,23 a possible path that might lead to the suppression of the domination relationship and hence to the end of the conflict consists of the four phases shown in Figure 1:

- Conscientization: the dominated become aware of the unjust imbalance in their status and power.

- Confrontation: the dominated begin to demand change in their situation and the recognition of their rights. This phase may involve violence.

- Negotiation: a negotiation process starts with or without the involvement of third parties.

- Sustainable peace: the relationship between the parties is restructured, becoming more balanced and leading to collaborative and peaceful relationships.

17 Figure 1, a re-elaboration of the Curle-Lederach model,24 helps in understanding the possible development of this type of conflict. As indicated by the vertical arrow, at the beginning of the conflict, there is a maximum power imbalance,25 and as the process goes on, the imbalance decreases. The horizontal arrow refers to the awareness26 that the parties (mainly the weaker) have of their objectives and their legitimacy. When the weaker are not aware of the domination relationship, but, either through culture or ideological conviction, considers it as "natural," then there is no conflict. The confrontation phase cannot start unless conflict awareness reaches a certain level and the imbalance is not too high. This point is generally reached during the conscientization phase. Later, each side becomes aware of the opponent's objectives and their legitimacy, and that is when the negotiation phase can begin. Some empathic understanding of the opponent's objectives and basic needs is necessary for the parties to find a constructive way out of the conflict and to arrive at a sustainable peace.27

18 It must be made clear that in the process shown in Figure 1 nothing is deterministic. The process of reaching sustainable peace may be quite lengthy and costly, with some cycling between successive phases of confrontation and negotiation. It might be the case that negotiations lead to an unstable condition of appeasement, followed, after some time, by a new outbreak of violent confrontation. This occurred during the decolonization conflict in Zimbabwe, where the settlement of the conflict set the conditions for the recent outbreak of violence and political instability.

19 Let us examine the different stages of this process in more detail.

Conscientization

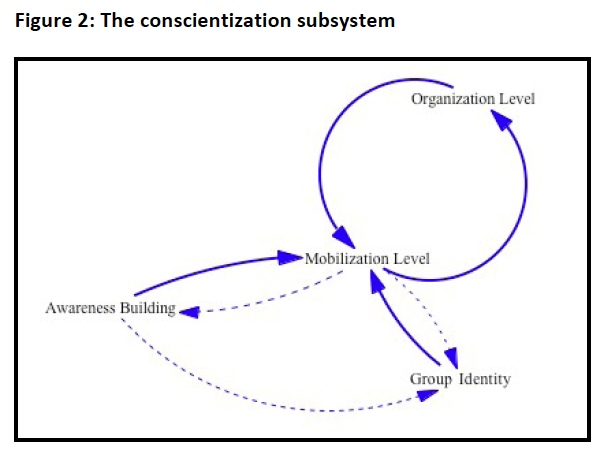

20 This term, borrowed from Paulo Freire,28 refers to the process through which dominated populations or individuals become aware of the structural injustice that characterizes the situation in which they live, and they come to realize the need to resist the domination. Conscientization has four main aspects: conflict awareness; group identity; mobilization; and organization. Growth of conflict awareness and building of group identity are basic components of the process. Without them, no mobilization can occur. They are distinct but intertwined. The growth of awareness often has the effect of strengthening the group identity: by gaining awareness of the domination relationship, the dominated see themselves as a group with common interests/needs and with a common adversary. This fosters mobilization and organization. These phases are usually non-linear: feedback often leads to reinforcing loops. Organization fosters mobilization and the growth of mobilization calls for more complex forms of organization, which in turn strengthens and enlarges the organization itself. Moreover, no mobilization can happen without some level of awareness of the domination structures and of the group identity. At the same time, mobilization attracts more participants to the struggle, widening and deepening the level of awareness and strengthening the group identity.

21 Figure 2 presents the main components of the conscientization phase and their interrelatedness. Solid lines represent stronger relationships. The arrows indicate the direction of the relationships. For instance, the solid arrow between group identity and mobilization level indicates that strengthening group identity makes the mobilization level grow, while the dotted arrow in the opposite direction shows that the construction of group identity is helped by an increased level of mobilization, although this relationship is often weaker than the former one.

22 The subsystem of Figure 2 is not a closed one: variables not included may have a relevant impact on the process. One example is international support, whose role may be crucial in organization building. Another example is the interplay between repression and group identity: while in the short term repressive actions might reduce the mobilization capacity of the dominated, it is often the case that in the long run group identity, and henceforth mobilization, is strengthened.29

Confrontation

23 Increasing awareness of latent conflicts, together with growing mobilization, usually leads the dominated party to confront the dominating one. Confrontation could take different forms: passive resistance, political mobilization, non-violent struggle, military actions, or terrorist attacks. Usually more than one of these types of actions coexist. This may be due to the existence of political and military wings within the same movement, the two being quite independent of each other, where one operates openly and the other covertly. An example was the IRA and Sinn Fein in Northern Ireland.

24 However, it also happens when the intra-party cohesion of the dominated party is loose, with different groups and organizations fighting for the leadership. This phase is often strictly intertwined with the previous one. Forms of confrontation may appear quite early, soon after the dominated party becomes aware of the unjust domination relationship. In fact, the confrontation itself accelerates the conscientization process, extending it to new sectors of the population, giving rise to a reinforcing loop. Repression, the most common response of the dominating party, in the short term might weaken the resistance movement, but in the long run it most likely strengthens the adversary’s resolve and fosters the conscientization process. This results most often in an increase in both power balance and conflict awareness. The weaker side (the dominated) becomes stronger and challenges the stronger side (the dominant). At the same time, both parties increase the awareness of their own objectives, and, possibly, also of their opponents.

Negotiation

25 The negotiation stage is reached when the two parties arrive at the conclusion that the cost of the struggle is becoming unbearable or when a third party is able to convince or to force them to negotiate. Usually the party who needs to be convinced the most is the dominating one, as the status quo is in its favor. A fairly necessary condition for arriving at the negotiation stage is the reduction of the parties’ imbalance. This is especially true for the "legal status" and "access" dimensions of structural asymmetry. Negotiation is a way to make each side confront their opponent's objectives and to recognize the legitimacy of at least part of them. In particular, it is the dominating side — which is no longer that dominant, since the power balance has increased — that has to adjust to the new reality and to renounce some of its own objectives. Thus, the conflict awareness reaches its highest point.30

Sustainable Peace

26 Once an agreement has been reached, a new process starts: building a sustainable peace. This implies restructuring the relationships between the parties; dismantling the stock of hatred, prejudices, frustration, and reciprocal mistrust that years of oppressive domination and violence have created; and deconstructing and reforming the domination structures. This cannot happen at once; it requires painstaking work, also involving cultural transformation. In South Africa, the end of apartheid did not bring peace once and for all. Although the more unjust and oppressive structures have been dismantled, most of the people in the black townships have as yet seen little improvement in their living conditions, and economic inequalities are still appalling. Frustration felt by the disadvantaged sectors of the population might lead to a renewal of the conflict, possibly with new and more radical claims. Of the four phases of the process represented in Figure 1, sustainable peace is the most problematic. The other three are in some sense the natural consequence of the asymmetric conflict. Almost all the conflicts of this type, at least once, pass through these phases. This is not the case for the sustainable peace phase, which may or may not happen, and often does not. It is not simply the end of the conflict, but it is itself a long and demanding process. Returning to the South African example, the "Truth and Reconciliation Commission" chaired by Bishop Desmond Tutu has been a paradigmatic example of action moving in the direction of sustainable peace.31 Other examples of structurally asymmetric conflicts that have led to a situation similar to sustainable peace, as far as the relation between the parties is concerned, are the Indian struggle for independence, the decolonization war in Algeria, and the anti-segregation fight in North America. In the first case, a non-state actor — the Indian National Congress — through a campaign of non-violent civil disobedience forced a state actor — the British government — to retreat in 1947. Since independence, India and the UK have been able to build and maintain rather friendly and cooperative relations at economic, cultural, and social levels. More problematic is the case of Algeria and France. After the violent war that once again saw a non-state actor — the National Liberation Front — opposing a state, Algeria got independence from France in 1962. The relationship between Algeria and France had its ups and downs. Still, the strong ties between them, at economic, social, and cultural levels, have persisted despite periods of "disenchantment" and strained relations, and they have even grown. As for the last example, notwithstanding all the problems that still afflict the black minority, the election of an Afro-American president clearly represents a turning point in racial relations in the United States. These three cases are quite different one from the other. Still they bear some commonalities: in all cases the starting point of the conflict was the structurally unequal relationship between the parties; through conscientization and mobilization, conflict awareness grew to a point where the stronger party was forced to insert the issue in its political agenda and, at a certain point, to accept the elimination of the structural unbalance via either international agreements or internal legal reforms.

27 In Figure 1, the four phases are depicted as sequential. In reality, this is rarely the case. Most often, some of the phases overlap. Moreover — as pointed out by Lederach — at any one point the conflict may revert to one of the previous phases, with loops that may last for a long time. In complex social, political, and economic systems, processes are hardly linear and most often involve reinforcing loops.

28 Loops involving the two central phases of confrontation and negotiation are particularly important. It may happen that a failure to reach an agreement leads to a new, and possibly more violent, confrontation. Decisions are rarely taken by a single decision maker; most often, both camps have multiple actors, sometimes with different agendas, and some may gain from negotiation failure. Failures may happen even if there is a true willingness on both sides to reach an agreement. As well, groups not directly involved in (or excluded from) the negotiations put into place actions that are meant to derail them.

29 Sometimes the party with more to lose from a change in the status quo uses the negotiation to slow down the transition toward sustainable peace. This can be done in many ways:

- Feet-dragging, i.e., making the negotiations last as long as possible, and, in the meantime, allowing the situation in the field to change in order to make a solution in the terms of the other party more difficult if not wholly impracticable.

- Trying to divide the other camp. For instance, the stronger party may provide privileges to some chosen persons or groups in the other camp in order to make them more willing to agree to its terms.

- Putting in place actions that will likely prompt violent reactions from the more radical groups of the other party, so as to justify freezing the negotiations or, in the case where a provisional agreement has already been reached, halting its implementation.

30 It is important to highlight that a new outburst of violent confrontations after a failed negotiation phase may have significant effects on the mobilization and organization levels of the weaker party, thus requiring a new phase of conscientization and organization building. Needless to say, negative effects could also occur in the stronger party, whose population may become more radicalized and less willing to accept any change in the status quo.

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict as a Structural Asymmetric Conflict

31 Clearly, symmetry is only one of the points of view from which a conflict can be analyzed, although in some cases it is crucial. In general, more than one perspective is needed to fully understand the characteristics and dynamics of a conflict. Nevertheless, the structurally asymmetric conflict paradigm presented here can be very helpful in analyzing conflicts. In some cases, it is particularly effective in providing new insights into the reasons why a specific conflict has followed a certain pattern over time and possibly also in providing novel ideas about how to act in order to end the conflict sooner.

32 For this reason, in the next section of the article, we will focus on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in order to shed light on the reasons why, despite so many negotiation phases having taken place so far, not one of them was able to achieve sustainable peace, and, after more than 15 years since the first negotiations started, the conflict is still trapped in a never-ending negotiation-confrontation cycle.

33 First, it is important to highlight what type of asymmetry exists between the two parties in order to demonstrate the reasons why we believe the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a "structural" asymmetric conflict.32 Therefore, let us analyze the elements that characterize a structural asymmetric conflict which are present in the Israeli-Palestinian case.

34 The first is legal asymmetry which probably most characterizes this conflict. From 1948 onwards, Israel has been a state with its own territory, internationally recognized borders, a clear political agenda, a defined foreign policy, and a powerful and well-organized army. In contrast, the Palestinians had to fight to move from the status of "non-existence"33 — if not as "refugees"34 — to recognition as a nation, with their own right to a national state.35 Also, during the years of the British Mandate (1922-1948), despite the fact that both Jews and Arabs were living in Palestine under British power, legal asymmetry was evident. Jews were recognized as a nation whose rights were guaranteed by the text of the Mandate,36 while the Palestinians were not. This asymmetry had not existed at the beginning of the conflict (1880-1920) when some Eastern European Jews started to immigrate to Palestinian territory, at the time under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire. During those first 40 years, real asymmetry did not exist, because the two sides had a similar legal status: the Arabs living in the territory that was starting to be perceived as Palestine were Ottoman citizens but were marginalized in terms of political power; while the Zionist immigrants were mainly Russian Jews who were escaping from anti-Semitic pogroms and who migrated and settled despite Ottoman suspicion.37 In any case, had there been any asymmetry between the two parties, it would have been to the advantage of the Arabs.

35 After the Basel Congress of 1897, the structural asymmetry between the two groups started to appear. In terms of what Christopher Mitchell defines as access, the Zionist movement’s political agenda, notwithstanding the existence of different parties,38 was not balanced by a similar attitude to their opponent, since the Arab Palestinians had not yet developed a specific political program. At the same time, the international powers were aware of the Zionist agenda, thanks to Theodor Herzl’s diplomatic efforts, and this even improved after his death. The Balfour Declaration was a turning point39 because Zionism received the support of Great Britain, thus demonstrating the access the Zionist movement had been able to gain. On the contrary, the Arab Palestinians could not claim anything similar. Even Faysal, later the emir of Iraq, despite being the "champion" of Arab nationalism, had not taken into consideration Palestinian national aspirations when he signed the famous agreement with Chaim Weizmann in January 1919.

36 The Zionist intra-party cohesion was far more advanced than any form of cohesion among the Arab Palestinians.40 For example, despite the differences existing between David Ben Gurion’s political ideas and those of Ze’ev Jabotinsky, there was a basic consensus in the way Zionists behaved in order to create a Jewish state in Palestine and in the attitude they had toward the Arab Palestinians.41

37 Moreover, in terms of salience of goals, despite the existence of an Arab Palestinian élite that was aware of the risks represented by the Zionists,42 Jews were perfectly conscious of what they were fighting for, unlike the fragmented Arab Palestinian society.

38 Finally, as to survivability, anti-Semitism, which had spread throughout Europe in the 1930s, played a fundamental role. The Jews living in Palestine and those survivors who decided to move there were extremely committed to the end result, because the birth of Israel was perceived as a life-or-death chance; whereas, the Arab Palestinian community did not perceive the conflict in such a way, at least not until the 1947-1948 events. But, in that period, the asymmetry between the two parties was so strong that there was no chance for the Palestinians to succeed.

A Different Evolution: From Negotiation Back to Confrontation

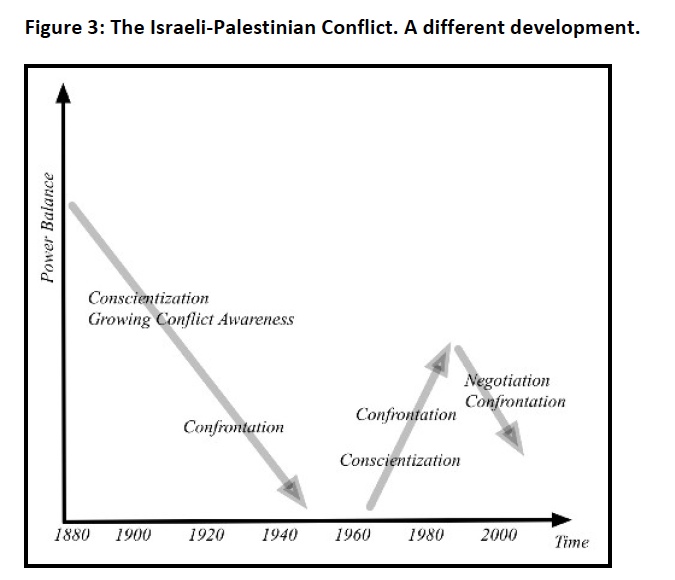

39 Given its generality and idealization, Figure 1 does not necessarily present the behavioral pattern of every single conflict. Each one has its own peculiarities and idiosyncrasies. And the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is no exception. For this reason, in this section we will analyze in detail the dynamics over time of this conflict, which are best represented by Figure 3.

40 At the beginning of the conflict in the 1880s an almost-perfect power balance existed. But between 1881 and 1948 it decreased (downward arrow) to a point where the Palestinians became completely powerless. In these 70 years, we can single out a conscientization phase, characterized by growing levels of conflict awareness (on both sides), intertwined with some episodes of violent confrontation, especially in the second half of the period after the advent of the British Mandate in Palestine in the early 1920s. While conflict awareness increased, the balance of power radically decreased, and the Jews (later the Israelis) became much stronger compared to the Arab Palestinians.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 341 The main reason why the Zionists were able to succeed and to create the state of Israel and the Palestinians were not lies in the weakness of the latter compared to the strength of the former in terms of conscientization.43 After the Balfour Declaration and during the 1920s and 1930s, the Zionist movement became much stronger than their Palestinian counterpart, both for internal and external reasons.44 In terms of economic parameters, human capital, urban-rural distribution, political awareness, and social structure, the Jews had a relevant advantage over the Arab Palestinians.

42 The power balance kept on decreasing during the 1930s and 1940s, when episodes of confrontation between the two sides took place, reaching its lowest level when the confrontation involved the newly born Israeli state against the Palestinians, who were completely disoriented and divided into different groups. Conflict awareness, on the contrary, kept increasing in both parties, especially among the new Jewish immigrants who were actively involved in the Israeli army (IDF) and among the 700,000 Palestinian refugees spread over the region.

43 During the 1950s and 1960s, the structural asymmetry between the two parties became an extremely relevant characteristic of this conflict. While the state of Israel was able to build the strongest and best-equipped army of the Middle East, the Palestinians could only create armed groups that carried out resistance actions, sometimes of a terrorist nature, both inside the territory of Israel and against Israeli (but also Jewish) targets abroad.

44 During these two decades, the Palestinians almost disappeared from the conflict, both from a military point of view and an ideological-political one. They re-emerged only after the 1967 Arab states’ defeat due to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and Fatah, the political faction that dominated it, led by Yasser Arafat. He managed to present the Palestinians as a nation that deserved a state. On the military side, after the Arab armies' defeat in the Six Day War, it was mainly up to the Palestinians to fight against Israel through guerrilla actions and terrorist attacks conducted either by the Fatah organization Al-’Asifah (the Storm) or by other more leftist groups, such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. In particular, since the Yom Kippur War, apart from incidents on the border with Syria, the clashes between the Syrian army and the IDF during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and the war against Hezbollah in the summer of 2006, Palestinians have been mounting the only confrontations with Israel. On the ideological-political side, the Palestinians became the main actor of the conflict and presented themselves to international public opinion as a self-confident and mature national movement that was aiming at creating their own state.

45 The First Intifada (1987-1993), in particular, caused extremely important developments.45 First, it was clear that Israel and the Palestinians were the only two relevant protagonists of the conflict. No solution would be reached unless the Israelis were willing to consider the Palestinians as a political community with national political rights and unless the Palestinians would accept the existence of the state of Israel. Second, partly in response to the First Intifada and partly because of frustration over the inefficacy of armed violence, an official Palestinian compromise position emerged with the statement made on November 15, 1988 by the PLO — then based in Tunis — proclaiming an independent Palestinian state and implicitly recognizing the existence of Israel.46

46 Therefore, as described in Figure 3, in the 1970s and 1980s the power balance increased significantly (upward arrow). Despite bloody events, such as Black September and the 1982 Lebanon invasion, the Palestinians were recognized by the entire international community as a national movement aiming at establishing their own state. At the same time, they created civil society organizations in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT) and a genre of political institutions. Finally, through the First Intifada, the Palestinians were able to challenge the incredible superiority of the Israeli military in view of the entire world, fostering increasing sympathy for Palestinian children throwing stones against Israeli tanks. The power balance reached its zenith at the beginning of the 1990s during the Madrid Conference (October 30-November 1, 1991), when for the first time Israel sat at the same table with the neighboring Arab countries, and Israelis and Palestinians were "forced" to negotiate.

47 Why did this negotiation not lead to a sustainable peace? According to the model we have analyzed in the first part of the article, confrontation should have allowed the weaker party in a conflict (i.e., the Palestinians) to strengthen itself so as to force the stronger party (i.e., the Israelis) to begin negotiating. However, the negotiation phase represented an interruption in this process of growing power balance. The Israelis succeeded in transforming the negotiations — later the Oslo Agreements — into a never-ending process of bargaining, while the Palestinians failed to create the embryo of a functioning and democratic state. The power balance started to drop off again (last downward arrow), and this led to a new confrontation in September 2000.

48 What had happened? After more than four years of Intifada, the left-wing Israeli government created in June 1992 decided to negotiate with the Palestinians because it was clear to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin that the only way to call a halt to the conflict was through negotiations. But two contemporaneous negotiations began to take place. On the one side, in 1992-1993, the Israeli government talked to the "winner" of the confrontation, that is to say the Palestinians from the OPT, through bilateral meetings held in the US. On the other side, in 1993, Israel decided to negotiate with the PLO, without the Palestinians from the OPT even being informed. The main reason for such behavior was that, at the time, the PLO leadership was much weaker than the Palestinian delegation from the OPT. The former had lost the political and economic backing of the USSR and the communist bloc at the end of the Cold War. Also, it had not condemned Saddam Hussein’s behavior in the 1990-1991 Gulf crisis and therefore had lost the financial support of the Gulf states, mainly Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Finally, it was far away from the OPT and was at risk of losing its control of the Palestinian population living under the Israeli occupation.47 Obviously, the PLO was a weaker and softer negotiator compared with the Palestinians from the OPT. With the Oslo Agreements, the PLO relinquished at least two fundamental demands: the Israeli recognition of the existence of a Palestinian state and the interruption of construction of new Israeli settlements in the OPT. In exchange for these renunciations the PLO leadership was allowed to go back to the OPT and establish the Palestinian Authority (PA), and it was given a relevant economic and political power that it would never have been able to achieve otherwise.

49 The entire negotiation was destined to fail — as the Palestinians from the OPT had understood from the very beginning — because what the PLO got in exchange for the recognition of the State of Israel was only temporary autonomy. It did not get what the Palestinians had been asking for: an independent state or a formal commitment to it.48 The many agreements signed during the 1993-2000 years did not challenge the basic assumption Oslo was built on. The fundamental issues — settlements, the borders of the Palestinian state, Jerusalem, refugees — were never part of the negotiation until the Camp David summit of July 2000.49 Therefore, in retrospect, it was clear from the beginning that negotiation could not lead to a sustainable peace. And so during the Oslo years, what took place was the "foot-dragging" Yitzhak Shamir had planned for at the October-November 1991 Madrid Conference.50 Between 1993 and 2000, never-ending negotiations produced many different and detailed agreements, but in the meanwhile, the situation on the ground was changing, thus making it more and more difficult to obtain a solution to the conflict. The Israeli government did not freeze the "settlements industry" in the OPT; on the contrary, the size of the Jewish population living in the illegal settlements behind the Green Line almost doubled between 1993 and 2000, and the "land grab" went on, making the birth of a Palestinian state with a territorial continuity and clear borders almost totally unfeasible.51

50 On the Palestinian side, those groups that had not accepted the Oslo Agreements — mainly Hamas and the Islamic Jihad — challenged the PLO leadership’s authority and carried out suicide attacks among the Israeli civilian population. As we stated earlier, it may happen that the intra-party cohesion of the dominated party is loose, with different groups and organizations fighting for the leadership of the resistance movement. The Palestinian case is a typical example of such a trend. Arafat was either unable or unwilling to claim what Weber defined as "monopoly of violence" by letting Hamas, the Islamic Jihad, and other military groups act independently from PA control. At the same time, the PLO leadership completely failed to behave in a different way compared to the traditional performance of the Arab states in the region. Not only did the PLO fail to build effective para-state institutions that would represent the embryo of a Palestinian state, ready to be functioning once (if ever) Israel had accepted its establishment, but the PA also became an authoritarian, corrupt structure, with no accountability and with a long roster of human rights violations. This ended by increasing the Palestinian population’s level of dissatisfaction towards the PA, which was often perceived as backing Israel in its occupation policy instead of fighting against it. Finally, Israel did not miss any opportunity to undermine the PA authority by not respecting the timetable and contents of the Oslo Agreements, thereby further dividing Palestinian political and civil society.52

51 Negotiation, therefore, was followed by a new confrontation, the so-called Second Intifada (2000-2004), which was characterized by a new cycle of violence. The PLO leadership thought it could transform Palestinian disappointment into a military confrontation against Israel in order to force the Israeli government to be more "generous" during the following negotiation round. However, Arafat made a terrible mistake. Israel did not miss the opportunity to inflict a hard blow to the PA, and Palestinian institutions almost completely collapsed. Given the serious situation Israel faced caused by the wave of suicide attacks carried out in February-March 2002, and thanks to a favorable international climate,53 Israel used an iron fist to crush the Palestinians: PA infrastructures were targeted with extreme violence, not only the Muqatas in Ramallah and other West Bank cities, but also ministries, governmental buildings, and even registry offices.54

52 How can such behavior be explained, given that — at least formally — the PA was still an Israeli ally? By examining the 1982 Lebanon invasion, it is possible to identify a kind of fil rouge connecting the behavior of Ariel Sharon when he was defense minister in 1982 with his conduct as prime minister in 2001-2004. The main aim of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon was to sweep the PLO out of Lebanon in order to diminish attacks against Israeli territory, despite the border having been safe for almost a year. In reality Israel was aiming to achieve two results simultaneously. First, by destroying the para-state institutions that the PLO had created in Lebanon, they would inflict a major blow to the Palestinian attempt to create an embryonic state structure. Second by severing contacts between the PLO and Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza, they would weaken the Palestinian leadership in the OPT.

53 During their 2002-2003 campaign against the West Bank and Gaza, the Israelis used similar tactics. By destroying the presidential compounds, ministry buildings, and the police facilities, they attacked the para-state institutions the Palestinians had created in the OPT, setting the PA back years in its attempt to create a Palestinian state.

54 At the same time, another pattern emerged. Since the mandate period, Israel tried — and actually succeeded — in strengthening divisions existing among the Palestinians. This was part of a clear strategy: split the Palestinians into different groups in order to diminish their strength and then negotiate with the weakest actor.

55 After 1948, the Palestinians were divided into four groups: those who remained in Israel and became Israeli citizens; those who either remained in (as residents) or moved to (as refugees) the West Bank and Gaza under the rule of Jordan and Egypt respectively; those who moved to the neighboring countries as refugees, such as Egypt (apart from Gaza), Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan (the territory east of the Jordan River); and finally those who moved to far-away countries in either Europe, the Americas, or the Gulf region and constituted the Palestinian Diaspora.

56 After 1967, this division was further strengthened by another split between the Palestinians living in East Jerusalem who became "permanent residents" and were given more civil and political rights and the Palestinians living in the rest of the OPT. In the 1990s, after the First Gulf War and even more so with the beginning of the Oslo Agreements, the temporary rule not to allow non-Jerusalemites to enter the Jerusalem municipality area was strictly implemented. In this way, East Jerusalem became a completely different world, and East Jerusalemites became totally separated from the "other Palestinians." Soon after, Gaza too was separated from the West Bank when it became a closed area to the West Bankers. After the so-called Oslo II Agreement,55 another split was introduced between Palestinians living in A/B areas (under Palestinian jurisdiction) and those resident in C areas (under Israeli jurisdiction). These areas were defined according to the powers and responsibilities Israel and the PA exercised: inside A areas, the PA was fully responsible; in B areas, Israel and the PA shared powers; and Israel was in total control in C areas. Finally, after June 2007, relations became even more complicated because of the split between Gazans ruled by the Hamas government, who won the Palestinian Legislative Council elections in January 2006, and West Bankers, who are ruled by the Fatah emergency government created by the PA president who was elected in January 2005.56

57 The division among so many different groups (the Palestinian citizens of Israel, the Eastern Jerusalemites, the Palestinians living in Gaza, those living in the West Bank, and the refugees living in other Arab countries) has serious consequences for the negotiation process because it is obviously difficult for a single body (the PLO) to negotiate for the entire Palestinian world. On the one hand, it means that the negotiating team has too many different interests to take into account while negotiating; on the other hand, there are too many groups on whom to impose any agreement once reached.

58 This occurred during the Oslo process and in the aftermath of the November 2007 Annapolis peace conference. In fact, Abu Mazen, despite being the PLO president, represented "de facto" only the Palestinians living in the West Bank. The Gazans had their own government that took a much more radical stance than the Fatah-led PA; the Eastern Jerusalemites were not represented because Israel considered East Jerusalem as part of Israel; the Palestinian citizens of Israel were external to the negotiations;57 and finally, there were serious doubts that the Palestinian refugees living abroad are really represented by the PLO any longer. This means that Israel has reached its objective of dividing the Palestinians into several weak groups in order to maintain its superiority.

59 Therefore during the last fifteen years, the power balance has been decreased once again starting with the first negotiation phase (Oslo, 1993-2000), passing through the new confrontation (the Second Intifada, 2000-2004) and the new negotiation phase (Annapolis and its aftermath, 2007-2008), and ending with the new confrontation (the "Gaza" war, in January 2009). The final consequence is that Israel is once again much stronger than the Palestinians.

Conclusion: What Next?

60 According to the structure of the asymmetric conflicts we have been analyzing, low power balance and scarce conflict awareness — i.e., reciprocal awareness of the goals and living conditions of the other side — mean a very slight chance of successful negotiation and henceforth of reaching a sustainable peace.

61 This indicates that unless the power balance between Israel and the Palestinians increases and unless each side considers the other partner at its own level in terms of status, rights, and needs, there is no realistic chance of reaching a phase of sustainable peace. The two mistakes involving the Oslo Agreement were that Israel chose to negotiate with the weaker partner — the PLO and not the Palestinians from the inside — and that the core issues of the conflict were not addressed, in particular the main objective of the Palestinian side, the creation of a sovereign state.

62 From this point of view, the situation on the ground at the moment is not very promising. In terms of power balance, Israel is still much stronger than the Palestinians. Despite diplomatic attempts to create a national unity government between Fatah and Hamas, the two parts are still very far from reaching an agreement, and the separation between Gaza and the West Bank is more evident than ever. Clearly, the lack of unity has negative repercussions on the Palestinian capacity to close the gap with the Israelis in terms of power balance. As to conflict awareness, the strong support that the government’s decision to attack Gaza in December 2008-January 2009 received from the Israeli population, on the one side, and the understandably increasing anti-Israeli feeling among the Palestinian population, on the other, have further deepened the distance between Israelis and Palestinians and have decreased the reciprocal understanding of the opponent’s requests.

63 Therefore, according to the model this article focuses on, the main question remains: how to increase the power balance and conflict awareness. It would be too naïve to present a "package of instructions" to reach such a result. Yet, there are two major events that would certainly make it closer: re-establishing the unity of Palestinian factions and addressing the core issues of the conflict, such as the borders and the capital of the Palestinian state (i.e., the future of settlements and the status of Jerusalem) and the refugee problem.

64 The first step in moving in this direction would be to involve Hamas in any negotiation regarding the situation of the Gaza Strip. In fact, without an agreement between Israel and Hamas, there is no way to address the two fundamental issues: ending the Israeli siege of the Strip and assuring the security of the Israeli population living in the south. The second step would be to create a national unity government between Fatah and Hamas. Only later, after having reestablished unity within the Palestinian political authority (at least of those living in the OPT), would Israel and the new unity government start negotiations dealing with the core issues of the conflict. No negotiation should take place without them at the table, as happened in Oslo, in the road map, and in the negotiations following the Annapolis conference. Both Israelis and Palestinians should be forced by the international community to start negotiations with the immediate recognition of the existence of two states, whose details should be discussed simultaneously.

65 There are too many variables involved to make it possible to foresee what might happen in the near future. They include the actual behavior of the Netanyahu-led government, after the decision — in November 2009 — to announce a 10-month freeze on the West Bank settlement construction; the quarrel among the different groups inside Hamas, between the political and military leaderships in Gaza, and between the "insiders" and the leaders based in Damascus or Beirut; the outcomes of the power struggle within the Fatah leadership and its effect on the PA; regional stability; and last and most importantly, the role that the new American administration is ready and willing to play in the area, particularly, whether President Obama will be able to exert pressure on Israel and strengthen the PA in order to increase the power balance between the two sides.

66 In the meantime, as Ziad Abu Zayyad states in an article published in the Israeli liberal newspaper Haaretz, there is something concrete the Palestinians — from their side — should do:

67 It is clearly out of the scope of this article to address such a fundamental issue as the Palestinian non-violent struggle against the Israeli occupation. Yet, this would certainly have a positive effect on the power balance between Israel and the Palestinians, a crucial issue for the solution of a typical asymmetric conflict.

Giorgio Gallo is Professor of Operations Research at the University of Pisa and the former Director of the Interdisciplinary Center Sciences for Peace.

Arturo Marzano is Research Fellow in the History of International Relations at the Faculty of Political Sciences, University of Pisa, where he also teaches Contemporary History of the Middle East.