Display large image of Map 1

by Patrick O'Sullivan

INTRODUCTION

The domino theory of international political interaction, which seemed laid to rest over a decade ago,1 has arisen in a more generalized form as an explanation of the geographical incidence of turmoil. The geographical cliché of a falling row of dominoes was first voiced in the Pentagon in 1953. It provided an image of the force and process to be contained by the USA in the Southeast Asian shatterbelt. In 1991, when the Soviet Union suddenly collapsed, for a fleeting moment the image was reversed and cartoons appeared with dominoes falling in the opposite direction before the onslaught of Coca Cola, McDonalds and Levi Strauss. The disturbing resurrection of the domino theme, however, occurred in the corridors of the Kremlin. In the councils of the Russian military establishment the simile was applied to the spread of Islamic fundamentalism among the people of Central Asian republics and autonomous states.2

There is no well articulated theory of the geography of political violence. Pronouncements on the issue tend to take extreme positions. On the one hand there are those who emphasize what they deem to be a contagious spreading of eruptions from country to country in epidemic fashion. These are the domino theorists. In the diplomatic history literature D.J. Macdonald argues that the domino principle took shape in the Truman era, basing this on the metaphorical language employed by the administration.3 This has been countered by Frank Ninkovitch pushing its origins back to World War I.4 He treats domino theory as a symbol of the world vision which was first grasped by Woodrow Wilson. This conception of modernity contained, "[t]he knowledge that geopolitical space has been compressed to a globally explosive density."5 Awareness and anxiety built up over "the macro implications of micro conflicts."6 Ninkovitch traces the evolution of this construction and its implications for US interventionism through the Nixon administration. This concern with the role of domino theory in the relationship between perception and policy was also the subject of B. Glad and C.S. Taber's writing on the psychological dimensions of war.7 The focus of these works, however, is on the perceptions of American statesmen and their actions, not on the correspondence of their perceptions to reality. When we turn to practitioners there are clearly some who would agree with Henry Kissinger that, "the Domino Theory was not so much wrong as it was undifferentiated."8

Whilst not dismissing the impact of diffusing ideas and attitudes and the increased connectedness of the modern world, there are others who would give greater weight to local circumstances in the explanation of lethal competition for power, considering violence to be endemic. Robert McNamara wrote on US involvement in Vietnam that, "[o]ur misjudgment of friend and foe alike reflected our profound ignorance of the history, culture and politics of the people in the area."9 O'Sullivan has summarized the scholarly and practical opposition to domino theory.10

Domino theory, then, posits that the inspiration for violence spreads from one epicenter and proceeds from one neighboring country to another in contagious sequence. The counter position would be that political violence is a chance generated response to local circumstances. Obviously, the domino proposition is the strong case and the more attractive construction to the imagination. The purpose of this artcle is to evaluate the merits of the two positions. To this end a survey was made of the global incidence of violent political events month by month for 1993, recording the local and global circumstances of each conflict in a brief description.11 1993 was the year that the dust settled sufficiently after the collapse of the Soviet empire to begin to see the shape of things to come. These data, collected from news sources, described conflictual incidents in which there was a loss of more than one life. This record of hot spots for 1993 provided a factual basis for the exploration of the geographical dimension of political linkage. Mapping the data provides quantitative evidence of the possible transmission process operating between neighboring states. Before proceeding to this the context needs to be established with a history of domino theory in the Cold War era and beyond.

ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF DOMINO THEORY

The inspiration for the application of domino theory in the Cold War can be traced to William Bullitt, who had been US ambassador to Moscow in the 1930s.12 He feared that a monolithic communism spilling out from its Russian source, would sweep through China and Southeast Asia to engulf the world. H.J. Wiens presented a more scholarly version of this justification of American intervention.13 He asserted that the historical force of Han expansion was being harnessed by Soviet strategists for an assault on the colonial powers in order to build a new, communist empire. The first official expression of this view was in National Security Council document 64 in February 1950, where it was stated that, "Indochina is a key area of South East Asia and is under immediate threat."14 What came to be called domino theory was formalized in a 1952 National Security Council document, describing an attack on Indochina as "inherent in the existence of a hostile and aggressive communist China," holding that the loss of one Southeast Asian country would result in "relatively swift submission to or an alignment with communism of the rest of Southeast Asia and India, and in the longer term, of the Middle East (with the possible exception of at least Pakistan and Turkey) would in all probability progressively follow."15 Admiral Arthur Radford was responsible for the domino analogy. In 1953, at a meeting of the Joint Chiefs of Staff he advocated the use of nuclear bombing to relieve the French at Dien Bien Phu to prevent Indochina and Southeast Asia from falling "like a row of dominoes" to communism.16 By the 1960s in the Kennedy administration Walter Rostow and Maxwell Taylor had transformed the simile into a theory. Kennedy used it as a justification for intervention in Laos.17

C.P. Fitzgerald sought to dismiss "the fallacy of the dominoes," pointing to the fundamental significances of age-old rivalries between Annamese, Khmers, Thais, Burmese, Malays, Javanese and Filipinos, rather than communism, as a source of conflict.18 R. Murphy questioned the domino theory as a reliable representation of Chinese intentions and doubted that adjacency was an effective measure of influence.19 The savage suppression of the Chinese-led communists in Indonesia in 1965 pointed up the importance of local circumstances in determining outcomes. This event refuted domino theory for McNamara and he sought to counter its influence and wind down US militancy in Southeast Asia.20 McNamara's 1995 confessional mémoire makes it quite plain that in his mind the domino mentality was the first of the eleven causes of disaster in Vietnam, concluding: "1) We misjudged then as we have since the geopolitical intentions of our adversaries (in this case North Vietnam and the Vietcong, supported by China and the Soviet Union) and we exaggerated the danger to the United States in their actions."21

Domino theory, however, survived these attacks and lived on in the Nixon administration, surviving into the 1970s in the minds of John Connally, Gerald Ford and Henry Kissinger. They took out a full page advertisement in the 6 June 1976 issue of The New York Times, exhorting Italian leaders to keep communists out of government there to prevent Mediterranean dominoes from falling. Henry Kissinger remains attached to the notion still. In 1994 he wrote, "[e]ven in the absence of a central conspiracy, and for all the West knew at the time, the Domino Theory might nevertheless have been valid. Singapore's savvy and thoughtful Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, clearly thought so, and he has usually proven right."22

As late as 1985 Harm de Blij and Peter Muller, in one of the most widely used geography textbooks, identified domino theory as, "the idea that the fall of South Vietnam would inevitably lead to communist takeovers in Kampuchea, Laos, Thailand, Burma, Malaysia and, ultimately, Indonesia and the Philippines."23 They clearly deemed this to be a predictive model. After an hiatus of two editions when it disappeared, domino theory broke the surface again in 1994. In the 7th edition, de Blij and Muller restated domino theory as follows: "Properly defined, the domino theory holds that destabilization from any cause in one country can result in the collapse of order in a neighboring country, starting a chain of events that can affect a series of contiguous states in turn."24 This is a much more general proposition about the transmission of violent political impulses. With their new, wider definition, de Blij and Muller turn our attention to Southeast Europe where the domino effect has moved strife "from Slovenia to Croatia, onto Bosnia-Hercegovinia and SerbiaMontenegro, Albania and perhaps even Greece and Turkey." Neodominoism would seem to come down to the simple proposition that political violence and instability, whatever its complexion, is contagious and spreads to neighboring countries. This proposition creates some expectations about the geography of violent events. Observations of actual events, then, will enable us to make a judgement about the value of the theory.

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

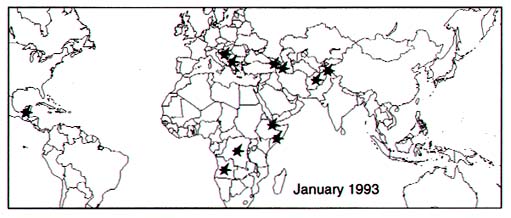

To match the domino theory proposition for consistency with the real world, a survey was made of collective violence indulged in the pursuit of political ends, whether it be warlike action or domestic rebellion or repression, generating conflict sufficiently deadly to result in the loss of more than one life. To test a geographic proposition a geographical presentation of these data is apposite. They are presented as a series of monthly maps showing the accumulation of violent events through the year. To show clearly whether new incidents are or are not close to prior scenes of violence, incidents are shown by flashes when they first occur in a place, but as dots thereafter, even though there may be a reoccurrence of violence in the same place.

A month by month summary of new additions to the map follows and will suffice to introduce all of the relevant venues for violence, with descriptions drawn from de Lorenzo.25

January In Africa there was a continuation of fighting between UNITA and government forces in Angola; while in Zaire President Mobutu's guards clashed with dissident troops in Kinshasa. Civil strife gripped Djibouti and, despite the presence of would-be peacekeepers, factional clashes persisted in Somalia. Central Eurasia saw civil war in Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Tajikstan. In Europe Croats mounted an attack against the Serbs in Krajina and Muslims, Croats and Serbs did battle in Bosnia. The Guatemalan civil war played on in the Americas.

Map 1: January

February In Africa Tutsi rebels launched an offensive against the government in Rwanda. Togo was ripped apart by fighting between political factions. Government and rebel forces clashed in Chad. In Niger Taureg rebels attacked a number of villages. In Asia Hezbollah attacked the Israelis in occupied southern Lebanon. In the Americas fighting broke out between recontras and the army in Nicaragua.

Map 2: February

March In Africa fighting occurred between rebel factions in the Sudan. In the Middle East clashes took place between Israeli security forces and Palestinians in the Gaza and the West Bank. In Asia Annamese communities were attacked in Cambodia. In the Pacific Bougainville secessionists clashed with Papuan government forces.

Map 3: March

April In the Philippines government forces clashed with communist rebels.

Map 4: April

May In Sri Lanka the president was assassinated with a bomb that killed 23 others.

Map 5: May

June Rebel forces attacked a refugee camp near Monrovia in Liberia.

Map 6: June

July In South Africa an attack on an Anglican church took place and fighting occurred between ANC and Inkatha supporters. In Congo deadly clashes broke out between government and opposition supporters in Brazzaville. In Turkey Kurdish guerrillas attacked a Turkish village.

Map 7: July

August In Algeria Islamic fundamentalists attacked and killed a former prime minister. In Peru Sendero Luminoso supporters massacred fellow tribesmen who rejected Sendero control.

Map 8: August

September In Kenya government forces quelled ethnic violence. Islamic fundamentalists attacked police in Egypt. In India Sikh extremists bombed the offices of the Congress Party in New Delhi. In Haiti violence against supporters of President Aristide escalated.

Map 9: September

October In Burundi a wave of Hutu violence followed an attempted coup by Tutsi paratroopers. In Northern Ireland an IRA bombing was followed by revenge killings by Ulster Freedom Fighters.

Map 10: October

November In Nigeria a military putsch took place. In Israel security forces killed a number of Palestinian militants in Gaza and the West Bank.

Map 11: November

December There were no outbreaks of violence in places where there had not been incidents earlier in the year.

Map 12: December

ANALYSIS

It is evident that there was not a great deal of cross border influence at work in the incidence of political violence in 1993. Of all incidents only about a quarter (30 out of 119) involved cross border activity, and this was often a matter of seeking refuge or attempted peacemaking by a neighbor. The 30 incidents arose from just 10 conflicts. There was a spilling of internal strife into adjacent nations from Angola, Sudan, Togo and Rwanda, with the flight of refugees, borders being closed and troops massed on them. Rwanda's troubles also brought in French troops to protect their nationals. There was a bigger and longer-lasting foreign intervention with US/UN peacekeeping efforts in Somalia, which registered with incidents most months of 1993. The southern part of the Lebanon had a continuing foreign presence in the form of Israeli occupation forces and their allies at war with the Hezbollah. Bosnia was subject not only to UN peacekeeping operations but also the intervention of the Croatian army. There was Russian involvement in Georgia and Tajikstan's civil wars, with the latter spilling over into Afghanistan. Azerbaijan's conflict involved Armenia and spilled over into Iran.

If we only consider the second six months worth of incidents, to allow for a reasonable build-up of prior events, only half (5 out of 10) of the new outbreaks occurred in places adjacent to countries which had seen violent incidents previously. There was an equal chance of a new outbreak occurring in isolation or next door to a prior event.

The greatest fear of contagion abroad is of the spread of Islamic fundamentalism with its purported center of emanation in Iran. There were, indeed, outbreaks that could be credited to Iranian Shiite inspiration. The Hezbollah movement in Lebanon is the most obvious example. The transmission process of militancy is in some instances a matter of personal experience, as a voluntary mujahidin in Afghanistan on the part of some Egyptians and Algerians for example. Apart from being carried by passenger plane, the new jihad is carried on tape and via fundamentalist radio and television broadcasts. Islam is no longer spread from country to country by horse and the sword. Fundamentalists inspired violence accounted for about 15 percent of events in 1993 (18 out of 119). These would include those in Afghanistan, Lebanon, Tajikstan, Algeria, Egypt, and Azerbaijan. There was some cross border influence in over half of these (10 out of 18), but this was in some instances benign, such as the effort of the Iranian president to bring about the October ceasefire in Azerbaijan. This set does contain the only conflicts that came close to full-blown war between nations in 1993. In both cases the aggressors were not the Islamic parties. In Azerbaijan the Armenian army intervened, and in Tajikstan the Russians were involved, with Islamic forces employing Afghanistan as a haven. There were also accusations that the Russians were interfering in Georgia. Although Iranian influence on the Hezbollah in Lebanon is well-established, there is no evidence of direct control of fundamentalist groups in Egypt and Algeria, and certainly no discernible cross border effect. The only reference to the rest of the world in Algeria was the campaign against foreigners started in September which set a 30 November deadline for all foreigners to leave Algeria or face attack.

The other significant area of cross border interaction involved Rwanda, Burundi and Zaire in the continuing conflict between Hutu and Tutsi, which has been in train for 400 years. Nowhere else was there a strong and persistent pattern of foreign interaction. The overwhelmingly predominant source of strife was conflict between ethnically or religiously identified groups. Three-quarters of the incidents could be put in this category (88 out of 119). Among the others, political parties are often aligned ethnic lines. In some instances, such as Somalia, the fighting is between clans and bears little or no relationship to broader geographic scopes and identities.

CONCLUSION

It seems that the foundations of many battles in 1993 were laid down long ago and violence reflects local circumstances of physical setting and history rather than recent political inspiration. The incidence and repetition of violence in the Balkans, the Caucasus, the Levant, East Africa and Central Asia does suggest an alternative hypothesis concerning the geography of violence. The clustering of violent events that does occur may reflect the lie of the land rather than any contagious spreading between neighboring countries of political inspirations. The areas of rugged terrain which house so many ethnic conflicts give the advantage to the defence. Historically numbers of distinctive groups have managed to survive in such settings, sheltered from the wholesale eradication or assimilation visited upon people on the plains. Rather than the great tracts of cultural homogeneity of the lowlands, the landscape has preserved ethnic variegation and, thus, the potential for violent competition in rough landscape. As Vincent Malmström, writing of Eastern Europe, put it, "[l]owlands and open plains tend to be culturally homogeneous . . . mountain regions demonstrate considerable heterogeneity, owing not only to the fact that rugged terrain is divisive but only because they serve as refuges from lowland invaders."26 The geographic disposition of violence in the world is possibly not a reflection of diffusion processes, but rather of their opposite, of resistance and fragmentation. These regions have seen rivalry and conflict for a long time. It has at times been subdued by imperial subjugation, but reemerges when empires shrivel.

The majority of violent events in 1993 were clearly local matters. The one political force that was expanding in significance was Islamic fundamentalism and it is evident that the process of its spread and potency was not conditioned by geographic contiguity. However, the perusal of a year's worth of news reports is hardly an adequate basis to entirely dismiss such an entrenched image of the geopolitical process as domino theory. Clearly, the original Cold War context would imply a more prolonged time frame for the operation of the domino effect, and so information collected over several years would be necessary to test the theory's validity. This note was a response to the novel application of the notion to political violence in the post-Cold War era. Over the longer haul 1993 may prove atypical. The twelve month time frame from January to December may fail to catch an important periodicity in violent events. As a longer series emerges so greater linkage may be revealed. From where we stand now there are insufficient observations to warrant a thoroughgoing probabilistic assessment of the relationships involved. But for the present, from the limited information available, it does seem that domino theory, the notion of a contagious epidemic process in the incidence of political violence, has little to recommend it as an explanation of the pattern of global violence which is emerging with the 1990s.

Patrick O'Sullivan is Professor of Geography at Florida State University.

Endnotes

1. Patrick O'Sullivan, "Antidomino," Political Geography Quarterly, 1, no. 1 (January 1982), pp. 57-64.

Return to body of article

2. "The domino game," The Economist, 19 December 1992.

Return to body of article

3. D.J. Macdonald, "The Truman Administration and Global Responsibilities: The Birth of the Falling Domino Principle," in R. Jervis

and J. Snyder eds., Dominoes and Bandwagons: Strategic Beliefs and Greater Power Competition in the Eurasian Rimland (New

York: Oxford University Press, 1991), pp. 112-44.

Return to body of article

4. Frank A. Ninkovitch, Modernity and Power: A History of the Domino Theory in the Twentieth Century (Chicago, IL: University of

Chicago Press, 1994).

Return to body of article

5. Ibid, p. 56.

Return to body of article

6. Ibid, p. 68.

Return to body of article

7. B. Glad and C.S. Taber," Images, Learning and the Decision to Use Force: The Domino Theory of the United States," in B. Glad ed.,

Psychological Dimensions of War (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1990), pp. 56-81.

Return to body of article

8. Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994), p. 641.

Return to body of article

9. Robert McNamara, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam (New York: Random House, 1995), p. 322.

Return to body of article

10. O'Sullivan, "Antidonimo."

Return to body of article

11. J. de Lorenzo, "Hot Spots 1993," Working Paper no. 1 (Tallahassee, FL: Department of Geography Florida State University, 1994).

This data on violent events and description of their circumstances was compiled using Keesing's Record of World Events, Facts on

File, Time, Newsweek, US News and World Report, and The Economist.

Return to body of article

12. W.C. Bullit, "A Report to the American People on China," Life, 13 October 1947.

Return to body of article

13. H.J. Wiens, China's March Towards the Tropics (Hamden, CT: The Shoe String Press, 1954).

Return to body of article

14. Quoted in Kissinger Diplomacy, pp. 623-24.

Return to body of article

15. N. Sheehan, H. Smith, E.W. Kenworthy and F. Butterfield, The Pentagon Papers (New York: Bantam, 1971), p. 29.

Return to body of article

16. Robert B. Asprey, War in the Shadows (New York: Doubleday, 1975), p. 708.

Return to body of article

17. Department of State, Bulletin XLIV, 17 April 1961, p. 543.

Return to body of article

18. C.P. Fitzgerald, "The Fallacy of the Dominoes," The Nation, 28 June 1965, pp. 700-12.

Return to body of article

19. R. Murphy, "China and the Dominoes" Asian Survey, 6 (1966), pp. 510-15.

Return to body of article

20. Sheehan et al., Pentagon Papers, pp. 271-74.

Return to body of article

21. McNamara, Retrospect, p. 321.

Return to body of article

22. Kissinger, Diplomacy, p. 628.

Return to body of article

23. Harm de Blij and Peter O. Muller, Geography: Regions and Concepts, 4th ed. (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1985), p. 525.

Return to body of article

24. Harm J. de Blij and P.O. Muller, Geography: Realms, Regions and Concepts, 7th ed. (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1994), p.

569.

Return to body of article

25. De Lorenzo, "Hot Spots."

Return to body of article

26. Vincent Malmström, Geography of Europe (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1971), p. 112.

Return to body of article