by Uri Bar-Joseph

PREFACE

Defending his demand to prevent any discussion regarding the suspicious role of British intelligence agencies and personnel in the leak of notorious "Zinoviev letter," Austen Chamberlain, the Conservative prime minister who won the elections at least in part because of this leak, told a stormy Parliament that it was "in the essence of a Secret Service that it must be secret."1 In 1924 an argument such as this sufficed to end the opposition's demand for a thorough investigation of the intelligence aspects of the scandal. The same could have been true even forty years later. Today it could not. Since the early 1970s the growing involvement of other actors especially the legislative and judicial branches, and the media in the management of the democratic state's relations with its intelligence community has expropriated the monopoly over this sensitive domain from the hands of the executive branch and has made previously secret intelligence issues a normal subject of a public debate. This has led in most cases to two results: first, intelligence action has become more law-abiding than in the past; second, intelligence action has become more immune than in the past to the influence of parochial political interests.

The object of this article is to describe and explain how this process evolved in Israel. As noted by some students of the subject, this country presents a unique case in the domain of civil-military relations2 and, for similar reasons, it is also sui generis in the field of intelligence-state relationship. The narrow margins of Israel's national security, coupled with the magnitude of the Arab threat, made an effective intelligence community a necessary condition to ensure the state's ability to survive. Under such conditions, the tendency to ease legal limits over intelligence action and to minimize external supervision of intelligence agencies, as a means to ensure its effectiveness, is usually high. And yet, as one expert correctly concluded, Israel "is the only state that has succeeded, during the twentieth century, to preserve democratic institutions and a reasonable level of human rights for its citizens, despite a constant external threat."3 For our discussion, the most relevant point is that despite heavy external pressures, Israel's intelligence community has become, during close to five decades of its existence, both more law-abiding and more open to control and supervision by organs other than the executive branch.

In order to frame the Israeli case into a broader theoretical context, the first part of this paper will present a number of models of state-intelligence relationship. Turning to the Israeli case, the second part will trace and analyze the main milestones in the route that led this relationship from the form I term "unilateral-constitutional" control to the one termed "multilateral-constitutional" control. In the summary the article will present a number of explanations for this development as well as a short forecast regarding the future of intelligence control in Israel.

THE THEORETICAL CONTEXT

State-intelligence relations are unique in two respects. The first involves the principle of the rule of law, i.e., the degree to which intelligence organs act, or are requested to act, according to the state law. Since their work, especially in the area of domestic intelligence, may demand illegal action, the desire of the state and its ability to compel its intelligence community to act in accordance with the law makes this relationship unique among the state's relations with its national bureaucracies.

The second dimension relates to the degree to which intelligence organs serve parochial or partisan interests besides their declared task, namely to serve the national interest. Three factors make them more prone than other national bureaucracies to political intervention: first, information is power or a means to obtain power. Given that the more secret (or rare) the information is, the higher is its value, the secretive nature of intelligence information makes it one of the most valuable commodities in the political market. Second, intelligence estimates may serve as an important, even critical factor in determining the fate of national security debates. This is so since unlike policy makers, who are known to be committed to the policies they formulate, intelligence officers, by the definition of their occupation,are considered unbiased professionals.4 Hence, politicians will have strong incentives to influence the shape of the intelligence product to suit their political agenda. And third, the secretive environment in which intelligence functions which is a necessary condition for its proper functioning hampers external inspection, thus making political and intelligence misconduct more feasible. Together these three features explain both the temptation of politicians to interfere with professional intelligence work and the feasibility of such conduct. The likelihood that the intelligence community will act according to state law and be immune to partisan politics largely depends on the methods the state uses to control and supervise this community.

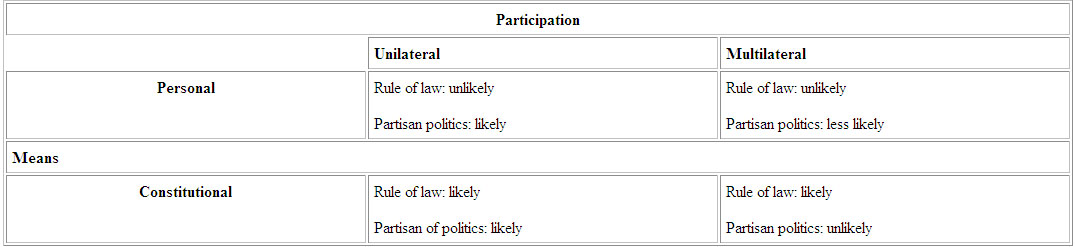

The form that this control can take is a function of two main variables: participation which of the state's institutions participates in controlling intelligence; and means how this control is maintained. Two methods of participation are possible: unilateral, when the executive branch has a monopoly on control and supervision of intelligence, and multilateral, by which control and supervision are maintained also by the legislative and the judicial branches, as well as by informal groups such as the media, pressure groups and public opinion. The means by which control is maintained may also be divided into two types: personal, in which individuals who are trusted to represent the interests of politicians are put in managerial positions in intelligence institutions in order to ensure that the agencies act in accordance with the policies outlined by these politicians; and constitutional, in which the regulation of control is maintained by state law.

The interaction between these variables yields four possible types of intelligence control. The first two unilateral-personal and multilateral-personal are usually found in non-democratic political systems. The unilateral-personal control system, in which intelligence chiefs are selected according to their level of loyalty to a single leader or a junta, is the most widely used method to supervise intelligence organs in countries with a low level of political culture. In the multilateral-personal method personal loyalty to the leader is of prime importance, yet it allows other groups which participate in the political process direct access to the intelligence community through representatives of their own. Intelligence action in accordance with state law is a principal aspect of state-intelligence relations in neither system.5

The other two methods are likely to be found only in democratic regimes. In the unilateral-constitutional system, the executive branch has de facto monopoly in intelligence control, but this is regulated by law or by institutionalized ethical norms rather than by personal means. Employment of this method demands that other participants in the political process who believe that secrecy is essential for effective intelligence conduct and that it cannot be maintained if other groups participate in intelligence control trust the executive branch not to abuse its excessive power. It remains effective as long as the executive branch is ready to restrain its power and the intelligence community acts solely on a professional basis. Its main test comes, however, at times of crisis, when sharp cleavages regarding the use of the intelligence services arise within the executive branch or between opposing political parties, or both. Under such circumstances, especially when the services are not professional enough, the boundaries between intelligence and partisan politics are very likely to collapse and state control over intelligence will become less effective.

The unilateral-constitutional control method is the system most likely to be employed in democracies following the establishment of a large intelligence bureaucracy. This was the case, for example, in the USA between 1947, when the CIA was established, and the mid-1970s, when the Watergate scandal and the Congressional investigations of the CIA and other intelligence agencies took place. Another example is Britain between the late nineteenth century, when the modern British intelligence system was born, and the early 1990s, when MI5, SIS and GCHQ "had been brought . . . in from the cold."67 As I will show below, state-intelligence relations in Israel between 1948 and the early 1990s also fell into this category.

Political-intelligence scandals, combined with declining threat perceptions are the main causes for the breakdown of this control system. In most instances it will be replaced by the fourth method of political control over intelligence: multilateral constitutional. Implementation of this system requires consensus within the political system about principles, such as the ethical rules which the services should follow, the need to avoid the politicization of the intelligence community, and the belief that the rule of law does not automatically contradict security requirements and the need for secrecy. Hence, it can be established only in countries in which political culture is highly developed and in which intelligence organizations are highly professional. Under such conditions the multilateral-constitutional system offers a method of checks and balances which prevents one branch from taking control over intelligence, and legal control which makes intelligence conduct according to law far more likely. Under such a system the intelligence community can reach professional autonomy, and at the same time, its ability and tendency to act illegally are reduced.

The multilateral-constitutional control system regulates intelligence-state relations in most West European countries as well as in Canada and Australia. The USA moved toward this system in the mid-1970s, when competition intensified between the executive and legislative branches over who would control the CIA. Consequently, Congress' share in the oversight of intelligence activities became far more decisive. This is also true with regard to the media, which had become an effective watchdog of the nexus between the administration and the CIA. Britain is among the last parliamentary democracies to give up the system of unilateral-constitutional control. But even here state-intelligence relations have been moving in recent years toward the multilateral-constitutional system.7

The following table summarizes the four types of control methods and the outcomes they are likely to yield.

TABLE 1

Israel has moved at the British rather than the American rate, but even here parliamentary, legislative, and media control of intelligence has increased significantly during the last decade. This process is the subject of the next section.

FROM UNILATERAL-CONSTITUTIONAL TO MULTILATERAL-CONSTITITUTIONAL: THE ISRAELI ROUTE

Israel's sovereign intelligence system was born on 30 June 1948, a month and a half after the establishment of the Jewish state. The new system included three main organs: first, the military intelligence service, known later by its Hebrew initials as Aman or DMI (Directorate of Military Intelligence), which was part of the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) and as such was subordinated to the Chief of Staff and, through him, to the Minister of Defense and the Israeli government. The second was the domestic intelligence service, later known as Shabak or GSS (General Security Service), which was subordinate directly to the Prime Minister. Finally, a foreign political intelligence service was established as part of the Foreign Ministry. In 1951, this agency ceased to exist. It was replaced by the Institute for Intelligence and Special Roles, known since as the Mossad, which became part of the Prime Minister's Office. Since 1951 no major changes in the structure of Israel's intelligence system have taken place. Thus, for more than 45 years now, the Prime Minister has been directly responsible for two intelligence organs the GSS and the Mossad. In the years when the Prime Minister also served as Minister of Defense (most of the period between 1948 and 1967 during David Ben-Gurion's and then Levi Eshkol's tenure, and between 1992 and 1996, during Yitzhak Rabin's and then Shimon Peres' tenure) he was in charge of all three services.

Until the mid-1980s, Israeli intelligence-state interaction was confined almost exclusively to the executive branch. Consequently, it suffered from some of the negative outcomes of the unilateral-constitutional control system, primarily the impact of partisan politics, on the conduct of professional intelligence work. One aspect of this defective relationship was the promotion policy of senior intelligence officers which, until the early 1980s, had always involved partisan considerations. For instance, all eight directors of military intelligence who were selected to this post when the Labor movement was in power (1948 to 1977) had a Labor inclination and some of them became party activists after leaving the army. The only director of Aman with a right-wing background was appointed to this post in 1978, shortly after the right-wing Likud party came to power. This pattern was changed only in 1983, when the Likud government confirmed the nomination of Major-General Ehud Barak for this post, despite his known socialist background.

Selection of heads of the GSS and Mossad involved partisan considerations as well. This was clearly the case with Isser Harel, the head of both organs in their first decade of existence. Unlike his military colleagues, Harel sometimes acted more like a politician of Mapai (the precursor of the Israeli Labor Party) than as a professional intelligence officer. For example, when in August 1954 the coalition headed by Mapai faced a crisis, Harel acted to preserve it. A few months later he warned Prime Minister Moshe Sharett against "negligence in preparations for the [coming] elections on behalf of the party. Preparations of the General [Zionist party] are in full swing while on our side they are moving very slowly."8 Harel's activities were not confined to advice alone. In 1953 two GSS agents were caught red-handed replacing batteries in a transmitter concealed under the desk of the leader of the leftist Mapam party. Two years later, Menachem Begin, the head of the right-wing opposition Herut Party, argued that GSS had attempted to bug his apartment. During the 1950s, moreover, Harel conducted an extensive struggle against the only untamed opposition magazine in Israel that sharply attacked Ben-Gurion and the rule of Mapai. Despite denials it seems that the GSS was behind the beating of the paper's editors, as well as an attempt to bomb the magazine's offices in 1955. Moreover, under Harel's instructions the GSS established in 1956 a popular weekly in an attempt to compete with and silence the opposition paper and to praise the rule of Mapai. Despite being subsidized by party funds, however, Harel's initiative in journalism was a fiasco and his magazine was closed down a few years later.9

This type of action could take place only within a framework in which state-intelligence interaction was confined, almost exclusively, to the executive branch. Victims of such activities complained publicly. But given that until 1957 the government officially denied the very existence of the GSS, and that neither the media nor the Knesset parliament had any access to the activities of this organ for many years to come, no serious investigation into such accusations and many others could be held.

In contrast, legal norms of intelligence conduct had been instituted within the community from the start. This was mainly the outcome of beliefs among senior members in Israel's legal system and political elite, primarily Ben-Gurion, that security needs were not necessarily superior to considerations of justice and the rule of law. As a result, the judicial branch (or at least some of its trusted members) was informed about sensitive intelligence activities and was allowed to investigate illegal intelligence action. Under certain circumstances, senior intelligence officers were brought to justice, an action that was instrumental in the process of establishing and reinforcing the norm that intelligence action should comply with state law.

The first and the most useful precedent for the institutionalization of such norms took place during Israel's War of Independence. Known as the Tobianski Affair, it involved legal investigations into a series of illegal acts taken by the chief of military intelligence, Colonel Isser Beeri. Most important of these were Beeri's responsibility for: the field court-martial and execution of Major Meir Tobianski of the IDF on the charge of treason; his orders to execute, without any legal process, an Arab informer who was suspected of betraying his Jewish handlers; and his attempts to fabricate evidence against Abba Hushi, the mayor of Haifa and a senior Mapai politician, whom he suspected of delivering information to British and Arab officers.

The principal decision to bring Beeri to justice for his order to execute the Arab informer was made by Prime Minister and Minister of Defense Ben-Gurion, who became convinced that "avoidance of assigning this case to court will mean a government cover-up, a bad example for the army, and, in addition, it will be argued that only low-ranking soldiers and officers are brought to justice."10 Beeri's defense line was that "intelligence action . . . [and] the law . . . cannot live together. Once a security service starts to act according to law, it will cease to be a security service."11 His three military judges rejected this argument, maintaining, instead, that no one

The court decided to remove Beeri from military intelligence without additional penalties. His military service ended shortly afterward.12 Massive political pressure, especially by the Mapam leftist party in which Beeri was a member, failed to prevent bringing Beeri to justice for his responsibility for the execution of Tobianski. In a two-week trial he was found guilty of conducting without authority a field court-martial. In a symbolic decision he was sentenced to spend one day, from sunrise to sunset, in prison. A few days later he received an amnesty from the president. The point, nevertheless, was well taken.13 The third case did not reach court for technical reasons. Ben-Gurion, nevertheless, regarded this act as Beeri's most severe crime.14

Three important precedents had been established here. First, by insisting that Beeri be brought to trial, Israel's young judicial system (the Attorney-General, and military and civilian courts) proved that no senior official was immune to the rule of law. Second, by finding Beeri guilty in two cases, Israel's jurists categorically rejected the notion that security needs contradicted the rule of law and that when such a conflict occurred, security considerations should prevail. Finally, Israel's political leadership, primarily Ben-Gurion the founder of the Jewish state and the strong man of Israeli politics, established a precedent according to which the autonomy of the juridical system should be preserved also in security matters.

These norms had to withstand various upheavals. What follow are the main events that put these norms to the test as well as the primary developments that shaped Israel's intelligence-state relations between the early 1950s and the mid-1990s.

The Lavon and the Ben-Barka Affairs

The Lavon and the Ben-Barka affairs constitute the two main cases in Israeli history in which party interests and the principle of the rule of law collided over intelligence action. The Lavon Affair is the name given to the political dimensions of Israel's most severe case of intelligence abuse of power the order given by the chief of military intelligence in 1954 to activate a network of Egyptian Jews to sabotage British and American installations in Egypt in order to prevent (or at least delay) the signing of the Anglo-Egyptian agreement on the evacuation of the British forces from the Canal Zone. In addition to being a total fiasco, the operation also triggered the most serious political scandal in Israeli history, one which lasted until the mid-1960s. Its focus was the question of who gave the order to launch the operation. The DMI chief admitted that he gave it, but argued it was under the instructions of Defense Minister Pinhas Lavon. The latter categorically denied that he had ever given such order.15

Who authorized the operation was also the core question in the 1965 Ben Barka affair. This time the quest involved the Mossad's assistance to French and Moroccan intelligence services in the kidnapping and murder of the Moroccan opposition leader Mehdi Ben Barka. The scandal was triggered by the former head of the Mossad, Isser Harel, who argued that in addition to being immoral and illegal, Israel's involvement in this case also jeopardized its strategic alliance with France. Meir Amit, who replaced Harel as Mossad director in 1963, asserted that Prime Minister Eshkol approved the operation. The latter claimed that he did not.16

In both cases Israel denied any responsibility for its intelligence action; in both it conducted a number of secret inquiries into the various aspects of these complex episodes; and neither of them yielded any definite answer to the question of who was responsible for the debacle. But the prime actor in the investigation of the Lavon Affair was Prime Minister and Minister of Defense Ben-Gurion, whose belief in the prevalence of the principle of the rule of law over parochial party interests led him to call for an investigation of the affair by a judicial commission of inquiry. His colleagues in Mapai, for whom prevention of political damage to the party was more important than any legal procedure, preferred an investigation by government members. Ben-Gurion's failure to establish the appropriate legal standards in the investigation of this affair was a major cause for his final retirement from the government in 1963.

With Ben-Gurion out of the executive arena, settling the Ben-Barka scandal within party corridors was easier. Initially, however, a "private" examination team nominated by Eshkol, and an internal unofficial investigation by junior Mapai members, accepted Amit's version that Eshkol approved the operation. But as could be expected, fear of another political scandal and the threat to party interests led to an additional political inquiry. This team, headed by Mapai's Secretary-General Golda Meir, concluded that Eshkol did not authorize the operation.17 Nevertheless, since all three investigations were conducted without any legal authority and in utmost secrecy, and since the last inquiry clearly aimed at sweeping the problem under the carpet, a settlement was reached and neither Amit nor Eshkol paid for this fiasco.

The dominance of partisan politics in the inquiries into the Lavon and Ben-Barka episodes constituted a great leap backward from the norms established by Ben-Gurion in the late 1940s, when intelligence mishaps and illegal action were investigated by legal means. But the scandals also created a consensus, even among Mapai politicians, regarding the need to establish a proper legal mechanism to investigate such incidents.

1967-1968: Political changes and the Law of Commissions of Inquiry

Two events which took place in the second half of the 1960s made the application of political solutions to legal intelligence problems far more difficult than before. The first was the establishment, at the height of the crisis that preceded the 1967 War, of Israel's first National Unity government. The new government included, for the first time in Israel's history, members from the right-wing Herut Party, as well as a non-Mapai defense minister. Although the new Defense Minister, Moshe Dayan, had a strong socialist background, his personal character and his problematic relationship with the elders of Mapai made him the least likely person to participate in conspiracies to conceal security and intelligence mishaps. And with Herut's leader Menahem Begin as a cabinet member, tacit cooperation among cabinet members to cover scandals that might damage the rule of the socialist camp in Israel became even less likely.

The second event was the passing in 1968 of the Law of Commissions of Inquiry. The new law, which was structured along the same lines as the 1921 British Law of Commissions of Inquiry, gave the state the legal mechanism to investigate such cases as the Lavon and the Ben Barka affairs. The main principle of the law is that the commission be "super neutral." Accordingly, the government or the Knesset Committee for Internal Supervision are authorized to establish such a commission, but once the decision is made their power ends and the legal system becomes the dominant actor. The President of the Supreme Court nominates the members of the commission; the chair of the commission must be a judge, preferably a Supreme Court justice; and the commission's powers are fairly extensive and include the right to summon witnesses and the right to use all necessary means to ensure that all relevant material be brought before its members. The sessions of the commission are open to the public unless required otherwise by security demands. Even under such circumstances the main conclusions of the commission's report are made public.18

The new shape of the cabinet combined with the Law of Commissions of Inquiry ended the era in which a small and cohesive group of politicians, mostly from the ruling Mapai party, had the monopoly in security affairs, and thus could conceal from the public delicate state scandals of professional and political misconduct. Indeed, from the late 1960s onwards, almost all investigations into national security fiascoes have been conducted by legal commissions. The most important of these were the Agranat Commission, which investigated the Yom Kippur War intelligence and military mishaps; the Kahan Commission, which inquired into Israel's responsibility for the massacre of Palestinians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila during the 1982 War in Lebanon; and the 1987 Landau commission which focused on the GSS interrogation methods. The only clear-cut case where the government evaded an official investigation was the Bus 300 Affair an act that provoked one of the most serious legal crises in Israeli history and is discussed later.

1971-1987: The General Security Service (GSS) systematic method of false evidence

Following the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967 and the dramatic upsurge in Palestinian terrorist acts, the GSS started to use methods of torture in interrogations of suspected terrorists. Until 1971, however, testimony regarding the procedures by which confessions from alleged terrorists had been obtained was given in court by police officers, whose task was to get the suspect to sign the confession obtained earlier by the GSS. Since the police officer was not present in the interrogation, he did not lie to the court when testifying that no violence was used to get the suspect to sign his confession. The ability of the GSS to keep up this legal facade was hampered in 1971, when lawyers representing Palestinian terrorists began to claim that their clients had confessed under physical pressure. Consequently, GSS interrogators were brought to the witness stand by the military prosecution to testify that no torture had been used during interrogations. The Service was now placed on the horns of the dilemma: on one hand was the principle of the rule of law and the need to give truthful evidence in Israeli courts; on the other were the need to conceal interrogation techniques and to prevent the invalidation of the defendant's confession. And since the main concern of the Service was to obtain information in order to prevent further terrorist acts rather than bring the terrorists to trial, it opted for the latter option. Consequently, between 1971 and 1987 GSS interrogators lied systematically in court and testified under oath, in thousands of cases, that no torture had been used in order to extract confessions.19

The practice of false evidence was adopted spontaneously by the GSS working echelons who felt themselves under extreme professional pressures in the face of escalating terrorist acts. The head of the GSS between 1964 and 1974, Yosef Harmelin, testified that he was not aware of this dilemma and that his main concern in 1971 was that the time taken from Service interrogators in court would hinder their operational effectiveness. His predecessor, Avraham Ahituv, testified that he was aware of the problem and tried to ignore and repress it. The third, Avraham Shalom, became head of the service when the system had already been in practice for nine years. For him it did not constitute a problem at all. It is unclear yet who else, outside the GSS, knew of this practice. The Landau Commission, which investigated the case in 1987, refrained from giving a definite answer to this question. Though it concluded that the civilian and military prosecutors were not aware of the practice of false testimony, it also quoted GSS officials who claimed that not only prosecutors but also military judges understood the system but preferred to turn a blind eye and avoid questioning the Service about it. According to some evidence by GSS officials, the political echelon, namely the prime ministers under whom the Service operated, were also aware of the system. The three prime ministers who testified before the commission Yitzhak Rabin, Shimon Peres, and Yitzhak Shamir denied it. The commission accepted these denials.20 It seems, though, that the commission was extremely cautious in this regard. Had it reached a different conclusion perhaps closer to reality this would imply that it was not only the GSS that had broken the law for so many years, but also Israel's top political echelon and, most important, significant elements of its legal system.

GSS systematic use of false evidence in court ceased in June 1987, as an indirect outcome of the Bus 300 scandal and as a direct result of the Nafsu case, in which Israel's Supreme Court ruled that the GSS broke the law by extracting a confession from IDF Lieutenant Izzat Nafsu, charged with treason and espionage against Israel, through "unacceptable means of pressure." This ruling triggered the investigation by the Landau Commission of the GSS interrogation techniques, and a clear order by the head of the GSS that ". . . the Service will not allow perjury in court."21 Though the Landau Commission concluded that this order had indeed put an end to the GSS practice of false evidence, it also admitted that the need to use physical pressure to extract information from suspected terrorists could not be denied. Consequently, it concluded that when non-violent psychological pressure and sophisticated interrogation techniques failed to obtain the necessary information "a moderate amount of physical pressure is unavoidable." Here, the commission chose the golden mean between security and legal demands. As will be shown later the same compromise was also adopted in the Law of the GSS.

The Bus 300 Affair

On 12 April 1984, four Palestinians from the Gaza Strip hijacked a bus (No. 300) en route from Tel Aviv to Ashkelon. A military assault team stormed the bus, killed two hijackers and captured the other two. Journalists who were present at the scene saw the two taken alive from the bus and pictures of them were taken. Shortly afterwards, however, the IDF spokesman announced that the two had died of their wounds on the way to hospital. Under the circumstances doubts regarding the truth of the official statement were raised, not only by the media but also by senior military officers, and Defense Minister Moshe Arens appointed the Defense Ministry Comptroller, Major-General (res.) Meir Zorea, to conduct an inquiry into the affair. Zorea concluded that the two terrorists had been taken alive from the bus but left open the question of who killed them. An additional investigation, by the state prosecutor Yonah Blattman, concluded in August 1985 that there was insufficient evidence to bring charges for the killing, but recommended indicting a senior IDF officer (Brigadier-General Yitzhak Mordechai, who in 1996 became Minister of Defense), five GSS men and three police officers for assault. A military court acquitted the officer and a special disciplinary court run jointly by the Mossad and the GSS cleared the five men of the security service. The charges against the police officers were dropped.22

At this stage, when the affair seemed to have been closed, events within the GSS led to its reopening. In October 1985 Reuven Hazak, the deputy of the head of the GSS called on his chief, Avraham Shalom, to resign on the grounds of his personal misconduct and cover-up in the affair. Hazak knew already that Shalom had given the order to kill the two hijackers and that the head of the GSS' operation division, Ehud Yatom, had carried it out. What triggered his, and two other senior GSS officials' demand, was that Shalom and his subordinates lied not only to outside investigations (the Zorea and Blattman commissions of inquiry), but also to the special disciplinary court run jointly by the Mossad and the GSS. Such behavior, they argued, broke the most sacred norm of the service, according to which lying outside was acceptable under extreme circumstances, but lies within the service were never accepted.23 When Shalom refused to resign Hazak went to Prime Minister Shimon Peres, who rejected the demand, and instead accused Hazak of attempting to carry out a putsch within the Service. Perceiving no other alternative, Hazak and his two senior colleagues met in February 1986 with the Attorney-General, Professor Yitzhak Zamir, and told him the main elements of the scandal and the cover-up story. Zamir demanded that Peres dismiss Shalom and the other key GSS participants in the plot. Peres refused. This was the spark that ignited the bitter confrontation between the Israeli legal system and the executive branch.24

In what was termed by one expert "a government rebellion against the rule of law,"25 Peres joined forces with right-wing Likud leader Yitzhak Shamir, who was prime minister at the time of the Bus 300 incident, and was now serving in the national unity government under Peres as Foreign Minister. According to a rotation agreement, Shamir was scheduled to replace Peres in October 1986. Peres was also backed by Yitzhak Rabin, a former Labor Prime Minister and Defense Minister at the time. Another key player in the government could have been the Minister of Justice, but the three politicians who held this post during 1986 proved that they were ready to sacrifice the principle of the rule of law for security needs and political interests. Almost all other cabinet members supported Peres as well. The Attorney-General and a few close assistants confronted them by demanding a police investigation into the accusations against Shalom.26

Details of the drama were leaked to the press. The editor of the daily Ma'ariv received telephone calls from a "deep throat" who briefed him on the main elements of the story. Considering himself as a patriot and a guardian of Israel's national security interests, however, the editor hesitated to publish the story.27 Other journalists were less reluctant, and in late May 1986 the accusations against the head of the GSS became public and the scandal broke.

At the focus of the public debate and the conflict between Zamir and the executive branch stood two specific questions: did the head of the GSS give the orders to kill the two terrorists, and did the GSS cover up its responsibility for this illegal action by falsifying evidence which diverted the fire to an innocent high-ranking military officer before external and internal commissions of inquiry and legal proceedings? Later, when Shalom publicly admitted his responsibility for the case, he would add that he did it with "permission and authority." This would raise a third question: Who authorized the killing and the cover up? Shalom claimed that five months before the incident he met Prime Minister Shamir with no other witnesses attending and the prime minister made it clear that no Palestinian survivors be left in the aftermath of terrorist acts. Denying this, Shamir accused Shalom of lying, and argued that he learned of the whole affair only when Hazak told him about it.28 In a like manner to the Lavon and the Ben Barka episodes, the question of who gave the order received no definite answer, although one inquiry concluded that "according to the available evidence the political echelon, i.e. Prime Minister Shamir, bears no responsibility for the death of the terrorists."29

But the principal question throughout the affair revolved around the conflict between security demands and the rule of law. Senior politicians argued that under the conditions in which Israel had found itself, certain legal limitations could be removed. Consequently, as President Chaim Herzog argued when explaining his decision to give amnesty to Shalom and the other GSS men before bringing their case to justice, ". . . a situation was created in which the GSS men had to face an investigation without being able to defend themselves unless the best kept secrets were revealed . . .. Under these circumstances I had to defend the public good and the nation's security. . ."30 On the other end were Professor Zamir and his assistants who demanded that a thorough police investigation into the case be conducted and that Shalom and other GSS men who were involved in the scandal be brought to justice. Responding to the argument that an investigation might reveal the nation's best kept secrets, Zamir's deputy said: "It is inconceivable that the state be afraid of its own agents . . . there was a threat [by Shalom and his men that secrets will be revealed] and, then, if the Prime Minister becomes weak in this matter, he is in the hands of the security men that he should govern and not the other way around."31 Supreme Court Justice Professor Aharon Barak expressed a similar outlook, maintaining that:

Israel's most influential dailies supported this stand from start. Ha'aretz warned that "security needs [do not] justify, even in one single case, that Israel cease to be a state of law." Yediot Aharonot said: "Nothing is more dangerous and unbearable than the use of security considerations in order to justify illegal action." And Ma'ariv's editorial argued that the new affair "constitutes an example of political intervention with the use of arguments such as 'security considerations', 'the national interest', and 'patriotism' in the authority of the Attorney-General to make decisions." All in all, the media position was Zamir's main source of power in his struggle against mounting political pressure to sweep the scandal under the carpet.33

In retrospect the affair had three different outcomes. In the immediate run, the politician's hand seems to have won. In June 1986, the government compelled Attorney-General Zamir to resign and replaced him by Justice Yosef Harish who proved far less decisive than his predecessor in pursuing the supremacy of law. Harish approved a complicated (and somewhat illegal) compromise, according to which Shalom and the other GSS participants in the plot, including Yatom, admitted their wrongdoing but immediately received amnesty from President Herzog. Thus, although Shalom had to leave the GSS he was never brought to trial and no extensive legal inquiry into the case had ever been conducted. Yatom, who personally murdered the terrorists, remained in the Service until his retirement in 1996.34

In the medium run outcomes were more positive. Despite strong objections, a police investigation into the case was conducted. Although it yielded no tangible assets in the form of legal procedures against the prime plotters, this was, nevertheless, the first time that the GSS was exposed to a police investigation. Another positive result involved improvements in communication methods between the head of the GSS and the political echelon as well as in the build-up of political means to improve control the service. These were mainly the outcomes of the conclusions of a special commission nominated by Peres to review certain aspects of the relationship between the GSS and the prime minister.35

But the affair's most important outcomes became clear only in the longer term. The crisis sparked by the murder of the two terrorists, the public debate it provoked, and the findings that showed misconduct, illegal action, and cover-up within the GSS, led to a normative change at three levels: within the GSS itself; in the relationship between the political echelon and the security apparatus; and, to some extent, in Israeli society as a whole.

The scandal shocked the GSS. Until the Bus 300 Affair, it was a tightly closed organization with very little external interference with its actions. Being an agency that had to act so long in the dim light between what is legally and morally acceptable and what is not, lack of proper guidance either external, by its direct supervisor, the Prime Minister, or internal, by its head led it to overconfidence and to the belief that no price had to be paid for moral and legal wrongdoing.36 After the scandal the Service became far more cautious and mindful of the need to act within the boundaries of the law. This does not mean that after 1986 the GSS did not cross the thin line between acceptable and unacceptable behavior. But given that the years that followed were the years of the Palestinian Intifada, the scandal no doubt reduced the amount of violence the service would have used under the new challenges.

The scandal also disturbed the intricate web of relations between the political echelon and the GSS. The GSS leadership learned that there was a limit to political support for illegal action, either because the political echelon did not want to pay the personal price involved especially when the media took a clear stand against such action or because it could not, owing to legal and public pressures. Despite receiving amnesty from the president, Shalom paid a high personal price for the action he took with, at least, some blessing by Prime Minister Shamir. The political echelon Peres, Shamir, and even President Herzog had to save Shalom from police investigations and legal procedures (an action for which they were criticized by the media), at least in part because of a tacit threat that the damage a thorough legal action might cause would spread beyond the boundaries of the GSS. Both sides must have learned, then, that political-intelligence cooperation in the conduct of illegal action was both limited and risky.

Finally, the Bus 300 fiasco had a more general impact as well. Though it is difficult to isolate the specific effect of this episode from the impact of other events which took place during the 1980s the most important of which were the war in Lebanon and the Intifada the affair must have shattered traditional beliefs regarding the supremacy of security requirements over other national interests. The Attorney-General and the professional staff of the Ministry of Justice proved that the GSS (as well as other intelligence agencies and security organs) could not and should not be immune from an external legal investigation. The media proved that in the 1980s the use of "security" as a means to allay public criticism was far less effective than in earlier years. The public learned that wrongdoing can take place even within Israel's most secret and sacred institutions. Even more important, the public may have learned that exposing such action does not necessarily entail a cost in the form of reduced operational effectiveness by these agencies. These normative changes found their expression in the form state-intelligence relations have taken a decade later, the best manifestation of which is the Law of the GSS.

The Law of the GSS and state-intelligence relations in the mid-1990s.

On 23 January 1996 a new bill called the Law of the GSS was presented to the public. The law was formulated by the Ministry of Justice in cooperation with the GSS, the Prime Minister's Office, the ministerial committee for the affairs of the GSS, and the Knesset Subcommittee for the Secret Services. The new law, which in the summer of 1997 was still scheduled to pass legislation, defines the authority of the service and the external means to control and supervise it. Its main points are:

Under special circumstances GSS interrogators are permitted to use physical pressure as a means to obtain information of critical importance in order to prevent terrorist acts. The new law does not specify these means but requires that it not be too inhumane and that its use should not cause any permanent damage and will be properly supervised and documented.37

Legal experts, intelligence officers, and politicians agree that a law to regulate the work of the GSS and its relations with the political echelon and other state agencies is essential. Nevertheless, the new law has been criticized, primarily by jurists and human rights activists in Israel and abroad, for permitting the use of torture. Important as this argument is, the principle point for our purpose is that the passing of the new law will, to a large extent, complete the transformation of intelligence-state relations in Israel from the model of unilateral-constitutional control to control and supervision by multilateral-constitutional methods.

By framing within a clear and specified law the chain of command and report between the political echelon and the GSS, its roles, and its methods of work, Israel comes closer than ever before to the model of the state which regulates its relations with its intelligence agencies by legal rather than by personal means. Moreover, in recent years another important change has taken place. This involves the second dimension of the control system the diversity of the actors which participate in the control and supervision of the system. In contrast to the situation in the early 1980s, where the executive branch held a rather closed monopoly in this domain, today the control and supervision of Israel's intelligence community is maintained by a wide number of organs. Most important of them are the following:

The executive branch: The GSS and the Mossad continue to be part of the Prime Minister's office. But in addition to the Premier's direct supervision of these agencies, for a few years now a special ministerial committee has supervised the work of the GSS, with emphasis on its interrogation methods. According to the Law of the GSS, a ministerial committee composed of the ministers of Defense, Justice, and Internal Security, and chaired by the Prime Minister, will serve as the communication link between the GSS and the government as a whole. It is not yet clear whether the government's communications with the Mossad will be channeled through a similar mechanism.

The legislative branch: Despite objections of the heads of the services, a four-member Subcommittee for Intelligence and the Secret Services started to function, in the ninth Knesset (1977-81). The experience gained since then is rather positive. In contrast to the practice of the Knesset Committee for Security and Foreign Affairs, to which this subcommittee belongs, there have been hardly any leaks from its sessions. It receives top secret reports on a regular basis and meets with heads of all the services.38 On the other hand the committee lacks effective means of supervision, as evidenced, for example, by its helplessness during the Bus 300 scandal. It seems that while its members are briefed on sensitive issues they have very little practical impact on them. This might change when the Law of the GSS is passed, though this law, in its present form does not entitle to the committee any new real power.

The State Comptroller: Both Mossad and GSS (as well as the IDF and DMI) are subject to external supervision by the office of the State Comptroller. This focuses mostly on finances and administration rather than operational questions or issues involved in the relationship between the intelligence organs and the political echelon. So far the findings had never been published. Instead, every annual report of the State Comptroller carries a note which states that both organizations have been examined and specifies the departments that have been checked (e.g., a Mossad operational department and the GSS interrogators' layout were examined in 1993).39 Nevertheless, an expert on the subject estimates that Israel is basically "in an ideal position insofar as access is concerned to even the most secret information . . ."40

The media: This is the domain where the most dramatic changes have taken place. As noted earlier, in 1986 the editor of Ma'ariv hesitated to publish the scoop about the Bus 300 scandal, at least in part because of patriotic considerations. Precisely ten years later the same paper came out with sensational headlines about a small financial scandal which involved a few junior workers in the GSS, not because the case itself (which faded away in a few days) was of any major importance, but because it took place within the GSS. Indeed, in recent years the Israeli media have become a rather effective and a very aggressive watchdog of the intelligence community. They publish regularly, in contrast to its past practice, all types of information about the services, including, for example, their estimated budgets (about NIS 1.5 billion for the Mossad in 1996), criticism of the Mossad's routine operations, and debates between the Mossad and Military Intelligence about distribution of powers in the domain of intelligence collection.41 Until early 1996, moreover, the identity of the heads of the GSS and the Mossad was considered an official state secret. Today these identities are released officially.

The growing share of the media in watching the intelligence community is a result of two developments. First, the media have become increasingly less restrained regarding sensitive security issues, and are today ready to publish intelligence secrets an act which was considered taboo only a decade ago. This process started in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War and gained additional momentum during the war in Lebanon, but until the mid-1980s it involved mainly the military aspects of Israel's national security. The Bus 300 incident seems to have spurred the media to more extensively cover the intelligence community too. The second development involves the military censor, which had to relax its policy and allow the publication of sensitive security information which it previously banned. This change of policy stems, at least in part, from a growing involvement of the Supreme Court in censorial decisions. In a landmark decision in 1988 the Supreme Court overruled the banning of an article which severely criticized the director of the Mossad and hinted that he would soon be replaced. This precedent had an immediate impact on the tendency of the military censor to use his authority to ban the publication of similar information.42 The new balance of forces between the censor and the media was officially recognized in May 1996 when the two signed a new and a far more liberal agreement, in which the censor gave up some of its draconian powers, including its right to close down a paper, and the media gained the right to appeal to the Supreme Court to overrule censorial decisions.43

Human rights organizations: A number of human rights organizations have been formed in Israel during the last two decades. Most of them groups such as B'tselem (The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories), Association for Civil Rights in Israel, Hamoked (Center for the Defense of the Individual), and Physicians for Human Rights focus their attention on human rights violations by Israeli security forces in the occupied territories. They usually do so by publishing evidence of such violations as a means of raising public opinion against them. Under certain conditions (e.g., the 1990 massacre at Temple Mount) they conduct an independent inquiry, either in order to encourage an official investigation or to prevent a cover-up by the authorities. Human rights groups also appeal to the Supreme Court in principal cases. All this action makes these organizations a rather effective watchdog of Israeli intelligence activity in the occupied territories.

SUMMARY

With a lively system of multiple bodies to control and supervise its intelligence community, and with the scheduled passing of the Law of the GSS in the Knesset, Israel has made considerable progress toward the multilateral-constitutional model of state-intelligence relations. This progress is especially impressive given that there "is no country in the world for whom the question of national security is as vital indeed even existential as it is for Israel."44

There are some general explanations for this progress. The professionalization that Israel's intelligence community has undergone during the last 45 years is certainly one of them. As Samuel Huntington argued so convincingly in his classical study on civil-military relations, professionalism is the key to isolating soldiers from politics in societies with a mature political culture;45 the same is also true for intelligence officers.46 In the Israeli case, the growing professionalization of intelligence officers especially in the managerial echelons, has led to a growing reluctance by intelligence chiefs to commit their agencies to parochial interests, to an increasing awareness of the need to act according to the law, and to a better cognizance of the limits of intelligence action. For example, in the early 1950s Isser Harel acted as head of the GSS and the Mossad and at the same time also as a Mapai apparatchick. None of his successors was ever ready to subject his professional duties to partisan politics in a similar manner. In addition, professionalization has made Israeli intelligence makers more prudent when engaged in politically sensitive operations. Thus, despite his excellent access to the most sensitive secrets of the American intelligence community, Jonathan Pollard's services were turned down by the Mossad precisely because of the fear that his exposure would cause immense damage to Israel's relations with the USA. For similar sober considerations the heads of the Mossad rejected Prime Minister Peres' demands to get involved in the Iran-contra project in its early stages. Consequently, Pollard was recruited by LAKAM, a small agency within the Ministry of Defense, and was handled by an enthusiastic but amateur case officer.47 A high level of amateurism also characterized Israel's involvement in the Iran-contra project. Both ventures ended up as embarrassing political and professional fiascoes.

Other factors that can explain changes in state-intelligence relations in Israel involve external and domestic developments. Important changes which took place during the last two decades in Israel's strategic environment is one of them. The signing of the peace treaty with Egypt in 1979 significantly reduced the external threat to the nation's security. The Oslo and Taba records with the Palestinians (1993, 1995) and the 1994 peace treaty with Jordan, lessened still furthermore the predominance of the security imperative in the Israeli thinking. Another explanation involves the changing of the guard in Israeli politics which took place during the early 1970s. Golda Meir's resignation from the government in 1974 signaled the end of the rule of the elders of Mapai the cohesive small group of politicians who had been so dominant in Israeli politics for more than two decades and who believed that "what is good for Mapai is good for Israel." They were replaced by a younger generation of politicians the most important of whom were Rabin and Peres who seem to display more loyalty to the rule of the law than to the rule of the party. The learning process is a third explanation. In the aftermath of strategic disasters such as the intelligence failure of 1973, the war in Lebanon, and, on a smaller scale, the Bus 300 incident, the Israeli public and the media learned that lack of an open discussion on matters of national security might hamper rather than strengthen the nation's security. At the same time Israeli politicians learned that attempts to cover intelligence fiascoes by the figleaf of "security needs" was risky and might have a boomerang effect in an open society which experienced the lessons of Yom Kippur and Lebanon.

Important as these explanations are, their main impact was not direct. Rather, it was channeled through a few individuals and small non-political elite groups that took a clear stand on the side of the law in the ongoing debate between security needs and the rule of the law. Most influential among them was David Ben-Gurion. His readiness to bring the director of Military Intelligence to military court in the middle of Israel's most difficult war established the norm that no one in the state was immune from legal justice. And although he failed to convince his government to investigate the "unfortunate business" by legal means, his efforts nevertheless ultimately yielded the Law of Commissions of Inquiry, which became the prime legal mechanism to investigate similar episodes in the future. During the 1980s, the principal actors were members of the legal system, primarily Professor Zamir (the Attorney-General at the initial stage of the Bus 300 scandal) and his close assistants, who withstood the massive political pressure with the help of the media. They lost the battle: the head of the GSS was not brought to justice. But they won the war, as reflected by the developments of the following decade the Landau Commission, the law of the GSS, and the greater openness of the services to external supervision. Other important actors have been the members of Israel's Supreme Court, first and foremost Justice Aharon Barak, who in a number of important decisions created legal precedents to regulate the relations between the state and its intelligence community. Finally, there are human rights organizations whose main contribution to a multiple supervision of the intelligence community is their alerting Israeli public opinion to atrocities committed in the occupied territories in the name of security needs.

Despite the considerable progress toward the multilateral-constitutional type of control, the continuation of this trend in the foreseeable future is far from certain. To start with, various studies show that neither the Israeli public as a whole nor the political elite in Israel holds beliefs that can improve supervision of the services. A recent study on Israeli public opinion in questions of national security has shown that in situations in which there was a conflict between security needs and the principle of the rule of law "the population always favored the security side of the equation, and over the years this trend seemed to strengthen."48 Another study, measuring political tolerance of the Israeli political elite (98 out of 120 members of the eleventh Knesset), found that: "In particular in situations of high threat and objection, the political elite does not seem to differ much from the general public."49

Against this background, recent political developments, primarily the establishment of Benyamin Netanyahu's right-wing government following the May 1996 elections, cast serious doubt on the continuation of the trend of recent years. The slowdown of the peace process increases the likelihood of Palestinian terrorism, military confrontations between Israel and the Palestinian authority, and even a general war with Syria. On the other hand, continuation of the peace process is likely to increase domestic violence, instigated especially by fanatic right-wing religious circles. Thus, whether the peace process stops or continues, security demands are likely to rise. Netanyahu and many of his cabinet members, moreover, have failed so far to show much respect for values such as human rights, freedom of the press, and rule of law. On some occasions they have even challenged the right of Israel's Supreme Court to hand down judgments in politically controversial issues. In addition, the legislation according to which the prime minister is elected directly (The Basic Law: The Government (1992)) tipped the balance between the executive and the legislative branches in favor of the former, leaving the Knesset with a smaller leverage vis-a-vis the prime minister.

As a result of these recent developments, security demands are likely to become predominant again and to mitigate the weight of human rights or rule of law values that gained power in recent years. Furthermore, the ability of institutions other than the executive branch, especially the Knesset and the juridical system, to participate in the control of the intelligence community is likely to decrease. Consequently, if this trend gains momentum, relations between the Israeli state and its intelligence community are likely to move away from the multilateral-constitutional model.

Such a development will certainly face opposition by the same actors who led the struggle for multilateral-constitutional control of the intelligence community in the past decade. The nomination in 1995 of Justice Aharon Barak (at the age of 59) as the president of the Supreme Court guarantees that this institution will continue to keep a close and active eye on the intelligence community for many years to come. Future legislation seems to be quite promising as well, as the fourteenth Knesset is expected to pass new basic laws in the field of civil and human rights. The media are unlikely to give up the role they have gained in recent years as the aggressive watchdog of the intelligence community and, if the need arises, human rights organizations will certainly escalate their struggle to limit the power of Israel's intelligence agencies, primarily the GSS. Finally, the impression is that within the Israeli secret services themselves there is today, more than ever in the past, a real awareness of the need to function in an effective manner professionally, but also in accordance with the law and under multiple supervision. Altogether then, this combination of forces suggests that a bitter struggle over the shape of supervision of Israel's intelligence system is likely to take place in coming years.

Endnotes

1. Bernard Porter, Plots and Paranoia: A History of Political Espionage in Britain, 1790-1988

(London: Unwin Hyman, 1988), p. 169.

Return to body of article

2. Yehuda Ben Meir, Civil-Military Relations in Israel (New York: Columbia University Press,

1995), pp. xi-xii. See also Amos Perlmutter, Military and Politics in Israel (London: Cass,

1969); Yoram Peri, Between Battles and Ballots: Israeli Military in Politics (Cambridge, MA:

Cambridge University Press, 1983); Moshe Lissak, ed., Israeli Society and its Defense

Establishment: The Social and Political Impact of a Protracted Violent Conflict (London: Cass,

1984).

Return to body of article

3. Menachem Hofnung, Israel - Security Needs vs. The Rule of Law (in Hebrew) (Jerusalem:

Nevo, 1991), p. 346.

Return to body of article

4. As Sherman Kent defined it, the intelligence product is "the kind of knowledge our state must

possess regarding other states in order to assure itself that its cause will not suffer nor its

undertakings fail because its statesmen and soldiers plan and act in ignorance." Sherman Kent,

Strategic Intelligence for American World Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton, 1966), p. 1. By the

definition of the product, its producers must be unbiased.

Return to body of article

5. For a discussion of these models, see Uri Bar-Joseph, Intelligence Intervention in the Politics

of Democratic States: The United States, Israel, and Britain (University Park, PA: Penn State

Press, 1995), pp. 61-64.

Return to body of article

6. Laurence Lustgarten and Ian Leigh, In From the Cold: National Security and Parliamentary

Democracy (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1994), p. 493.

Return to body of article

7. For a good discussion of the American case, see, for example, Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones, The CIA

and American Democracy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989); Loch K. Johnson,

America's Secret Power: The CIA in a Democratic Society (New York: Oxford University Press,

1989); and John Ranelagh, The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA (New York:

Touchstone, 1987). For a discussion of the British case, see Peter Gill, Policing Politics (London:

Cass, 1994); and Lustgarten and Leigh, In From the Cold.

Return to body of article

8. Moshe Sharett, Personal Diary (in Hebrew) (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 1978), pp. 568, 692.

Return to body of article

9. For a discussion of these episodes as well as some others, see Michael Bar-Zohar, Spies in the

Promised Land: Iser Harel and the Israeli Secret Service (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1972),

pp. 125-32; Yossi Melman and Dan Raviv, The Imperfect Spies: The History of Israeli

Intelligence (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1989), pp. 115-44; Ian Black and Benny Morris,

Israel's Secret Wars: A History of Israel's Intelligence Services (New York: Grove Weidenfeld,

1991), pp. 149-56. For Harel's version of these episodes, see Isser Harel, Security and

Democracy (in Hebrew) (Tel Aviv: Yediot Aharonot, 1989). For partisan politics considerations

in the nomination of directors of Mossad, see Peri, Between Battles and Ballots, pp. 243-44.

Return to body of article

10. Harel, Security and Democracy, p. 114.

Return to body of article

11. Ibid., p. 116; Shabtai Teveth, Firing Squad At Beth-Jiz (in Hebrew) (Tel Aviv: Ish-Dor,

1992), pp. 75-76.

Return to body of article

12. The verdict in Beeri's case, 9 February 1949, in Harel, Security and Democracy, p. 116;

Teveth, Firing Squad, pp. 75-76.

Return to body of article

13. Teveth, Firing Squad, p. 88-99; Yechiel Gutman, A Storm in the G.S.S., (in Hebrew) (Tel

Aviv: Yediot Aharonot, 1995), pp. 160-65.

Return to body of article

14. Harel, Security and Democracy, p. 123; Teveth, Firing Squad, p. 82.

Return to body of article

15. For an extensive discussion of the operational parameters of this case, see Bar-Joseph,

Intelligence Intervention, pp. 149-254; for an analysis of its political aspects, see Shabtai Teveth,

Ben-Gurion's Spy (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996).

Return to body of article

16. For a concise description of this case, see Melman and Raviv, Imperfect Spies, pp. 175-79;

Black and Morris, Israel's Secret Wars, pp. 202-5.

Return to body of article

17. Black and Morris, Israel's Secret Wars, pp. 204-5.

Return to body of article

18. Zeev Segal, Israeli Democracy: Governance in the State of Israel, (in Hebrew) (Tel Aviv:

State of Israel, Ministry of Defense, 1988), pp. 206-12.

Return to body of article

19. The Report of the Commission of Inquiry Concerning Methods of Investigation by the

General Security Service of Hostile Terrorist Activity, (in Hebrew) (Jerusalem: October 1987),

Part One, pp. 15, 18-20 (hereafter cited as The Landau Commission of Inquiry).

Return to body of article

20. Ibid., pp. 20, 30-32, 28-29.

Return to body of article

21. Ibid., pp. 5-9, 23.

Return to body of article

22. Black and Morris, Israel's Secret Wars, pp. 400-5; Ilan Rachum, The Israeli General Security

Service Affair (in Hebrew) (Jerusalem: Carmel, 1990), pp. 1-83.

Return to body of article

23. Black and Morris, Israel's Secret Wars, p. 405; Rachum, Israeli General Security Service

Affair, pp. 84-85; Gutman, Storm in the G.S.S., pp. 35-36.

Return to body of article

24. Rachum, Israeli General Security Service Affair, pp. 89-97; Gutman, Storm in the G.S.S.,

pp. 40-43.

Return to body of article

25. Moshe Negbi, Above the Law: The Constitutional Crisis in Israel (in Hebrew) (Tel Aviv: Am

Oved, 1987), p. 9.

Return to body of article

26. Gutman, Storm in the G.S.S., pp. 58-63.

Return to body of article

27. The Ma'ariv Report on the GSS Affair (in Hebrew), 18 July 1986, pp. 3-5; Gutman, Storm in

the G.S.S., p. 56.

Return to body of article

28. Melman and Raviv, Imperfect Spies, pp. 308-9; Gutman, Storm in the G.S.S., pp. 89-91;

Shamir's interview in Yediot Aharonot, 3 July 1986. Later Hazak denied that he met Shamir

with regard to this issue. For this denial, see Gutman, Storm in the G.S.S., p. 105.

Return to body of article

29. The Report of the Karp Commission of Inquiry, in Gutman, Storm in the G.S.S., p. 121.

Return to body of article

30. Gutman, Storm in the G.S.S., p. 91.

Return to body of article

31. Ibid., p. 95.

Return to body of article

32. BGZ 428/86, Barzilai V. The Government of Israel and the Attorney General, P.D. 40(3), p.

505.

Return to body of article

33. These citations are in Gutman, Storm in the G.S.S., pp. 60-61.

Return to body of article

34. Ibid., pp. 83-91; Yediot Aharonot, 26 July 1996.

Return to body of article

35. Ibid., pp. 108-9; 119-20.

Return to body of article

36. Much of the professional criticism of Shalom focused on the fact that he gave the orders to

kill the terrorists despite the presence of journalists at the scene of action. His decision, according

to critics, showed a low level of discretion and a belief that the GSS is protected against any

external check.

Return to body of article

37. In light of legal experts' opposition to this section, it is possible that the law will pass without

it (Ha'aretz, 10 February 1997).

Return to body of article

38. Ben Meir, Civil-Military Relations in Israel, p. 50.

Return to body of article

39. State Comptroller, Annual Report 44 (in Hebrew) (Jerusalem: Government Printing Office,

1994), p. 1168. This practice may be changed. In the summer of 1997, the State Comptroller,

Judge Miriam Ben-Porat, demanded to publish a critical report of the GSS' investigation

department that was conducted in the early 1990s. The GSS objected to this demand. A two men

team is expected to decide the fate of this report (Yediot Aharonot, 7 July 1997).

Return to body of article

40. Benjamin Geist, "State Audit and Secrecy," in A. Friedberg, B. Geist, N. Mizrahi, I.

Sharkansky, Studies in State Audit (in Hebrew) (Jerusalem: State of Israel, State Comptroller's

Office, 1995), pp. 104-17, 111.

Return to body of article

41. Ha'aretz, 7 January 1996; 24 January 1996; 27 February 1996.

Return to body of article

42. Moshe Negbi, Freedom of the Press in Israel - the Legal Aspect (in Hebrew) (The Jerusalem

Institute for Israel Studies: Jerusalem, 1995), pp. 45-6.

Return to body of article

43. Ha'aretz, 23 May 1996.

Return to body of article

44. Ben Meir, Civil-Military Relations in Israel, p. vi.

Return to body of article

45. Samuel P. Huntington, The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military

Relations (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1959).

Return to body of article

46. Bar-Joseph, Intelligence Intervention, pp. 47-58; 358-61.

Return to body of article

47. For details on LAKAM, see Melman and Raviv, Imperfect Spies, pp. 95-114; Black and

Morris, Israel's Secret Wars, pp. 416-26; and Wolf Blitzer, Territory of Lies: The Rise, Fall, and

Betrayal of Jonathan Jay Pollard (New York: Harper and Row, 1989), pp. 86-89, 97.

Return to body of article

48. Asher Arian, Security Threatened: Surveying Israeli Opinion on Peace and War (Cambridge,

MA: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 234, 278.

Return to body of article

49. Michal Shamir, "Political Intolerance among Masses and Elites in Israel: A Reevaluation of

the Elitist Theory of Democracy," The Journal of Politics, 53, no. 4 (November 1991), pp.

1019-43, 1036.

Return to body of article