by Richard J. Chasdi

INTRODUCTION

The study of political terrorism demands that research move beyond theoretically threadbare accounts of what happened and where, toward more rigorous scientific efforts. This analysis uses empirical data to determine whether or not variations in target selection and terrorist act characteristics exist according to terrorist group-type. This will provide fresh insights for scholars and policymakers into the nature of terrorism.

An underlying theme of some important works on terrorism is that the rationality assumption in decision-making is as valid for terrorist tacticians as it is for the political leadership of nation-states.1 What seems significant here is to understand that the terrorist who straps pipe bombs around his or her waist and boards a bus may in fact be acting rationally.2 Taken one step further, this way of thinking about terrorism means that terrorist group activity and, in the narrower sense, terrorist group targeting practices, are based on much more than chance and opportunity.

Eight Middle East terrorist group-types are crafted for this study. They are differentiated according to ideology, the presence or absence of a charismatic leader, and recruitment.3 This classification scheme draws from empirical studies of groups such as George Habash's Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, Sabri al Banna's Abu Nidal Organization, Wadi Haddad's Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-Special Operations Group, and Meir Kahane's Jewish Defense League (JDL), as well as from authoritative works on Middle East terrorism and "charismatic authority."4

The dependent variable is target, while the independent and intervening variables tested include: political ideology, location and political events. Several theoretical propositions about the major roles those variables play in determining terrorist group behavior are explored. Those hypotheses about Middle East terrorist group-types share a set of interconnections that are twofold in nature. At a basic level, they serve to flesh out the fundamental characteristics of Middle East terrorism by group-type, moving from suppositions to detect differences in targeting patterns, to suppositions that help to provide a more complete picture about the intensity of terrorist acts (i.e., number of deaths, wounded, and level of property damage). At a theoretical level, those hypotheses furnish analytical constructs that make it possible to breathe life into the underlying theme of this study, namely that meaningful distinctions can be made between varieties of "structuralist" and "non-structuralist" Middle East terrorist group-types in terms of target choice.

In the broadest sense, those group-types and hypotheses presuppose and derive from a Middle East terrorist group-type typology that is based on three defining characteristics: ideology, goals and recruitment patterns. That typology, which draws on Starr and Most's work on third world conflicts, can be represented as a three dimensional cube with the characteristics ideology, goals, and recruitment, each posited along one axis. Significantly, this terrorist group-type typology is functional in the sense that it can be used to isolate and identify patterns of terrorist group behavior that distinguishes one group-type from another. Another advantage of this typology is that it can accommodate the dissolution of terrorist group-types and the formation of new ones, in contrast to those typologies that classify terrorist groups according to location of incident, or the type of terrorist activity undertaken.5

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND DEFINITION OF TERRORISM

The theory that drives this study is conceived of as a continuum, with structuralist terrorist group-types at one axis and non-structuralist group-types at the other. In the case of Islamic and/or Arab terrorist group-types, it is proposed that the more "structuralist" a group-type is (i.e., the more the political struggle is viewed as one against a "world system" like capitalism and/or imperialism), the more emphasis it will place on government targets. Conversely, the more "non-structuralist" a group-type is (i.e., the more the political struggle is viewed as one waged against individuals), the more emphasis it places on civilian targets.6 It is also proposed that the influence of a charismatic leader ought to increase the intensity of terrorist attacks committed by groups that claim adherence to the prevailing social ideology of Islam or that embrace alternate systems like Marxism-Leninism.7 Jewish fundamentalist groups should present a radically different picture of terrorist group behavior. To be specific, Jewish fundamentalist groups should attack targets with less intensity than their Islamic counterparts. That is the case because Jewish fundamentalist terrorist groups operate predominately in so-called "friendly" areas such as Israel, the Occupied Territories and the United States.8

For the purposes of this study, any of the following is considered political terrorism: the threat, practice or promotion of force to influence the political attitudes or policy dispositions of a third party and used against: non-combatants; military personnel in non-combat or peacekeeping roles; combatants, if the aforementioned violates juridical principles of proportionality, military necessity and discrimination; regimes which have not committed egregious violations of the human rights regime that approach Nuremburg category crimes.9

DATA COLLECTION

The data base for this research was compiled from two sources: The Jerusalem Post and Edward Mickolus's chronology, Transnational Terrorism: A Chronology of Events 1968-1979. Reports of terrorism from 1 January 1978 to December 1993 were taken directly from that English language daily newspaper and comprise the largest portion of the data base. Entries from January 1968 to August 1978 for sixteen terrorist groups were taken from Mickolus's work.10 Known acts of "independent" state terrorism (i.e., non-reactive events unrelated to what some writers call "insurgent terrorism"), were excluded from the analysis. It follows that terrorist assaults that happened in the "security zone" in Southern Lebanon were excluded from the data base because, all too frequently, the fundamental question of whether or not a terrorist assault was really an act of state terrorism remained unclear.

To ensure data compatibility between entries extracted from Mickolus's work and articles drawn from the Jerusalem Post, I used Mickolus's entries on terrorist assaults as a guide to find matching reports whenever possible for the 1968-78 period. It follows that descriptions of terrorist incident attributes such as numbers of dead and wounded, and property damage, were taken from the Jerusalem Post when available. Otherwise, data provided in Mickolus's accounts were used. This data set, while comprehensive, does not represent every terrorist assault undertaken for the period of time under consideration. Undoubtedly, several terrorism incidents have been omitted because of the selective nature of accounts for the 1968-78 period, the extremely large number of unclaimed and uncompleted terrorist assaults, and human error (e.g., double counting, miscoding bits of terrorist event information, wrongful inclusion of "terrorism" events).11

The Jerusalem Post was chosen as the predominant centerpiece of this data base on Middle East terrorism for several compelling reasons. First, it provides in-depth accounts of terrorist assaults inextricably linked to Middle East politics that occur in the Middle East and throughout the world. Those reports provide descriptions, sometimes very rich, of the players involved, and the political context within which those terrorist assaults take place. Second, and equally important, Jerusalem Post accounts chronicle, in extensive and sustained ways, terrorist assaults that did not cause deaths, injuries or property damage or were otherwise thwarted. Regrettably, it is probably no exaggeration to say that the degree of coverage that major US and European papers devote to Middle East terrorism depends in large part on the physical or human devastation that occurs.

The use of Jerusalem Post accounts raises the issue of source bias. It must be acknowledged that some terrorist incidents might not be reported in the Jerusalem Post for national security reasons, or lack of access to or interest in attacks that happened in other parts of the Middle East. Likewise, some newspaper accounts published elsewhere in the Middle East also seem to suffer from source bias, a problem that might derive from protracted battles between pro-Western Sunni regimes and Islamic fundamentalist groups. One indication of this is that many English language newspaper accounts describe Islamic fundamentalist terrorist assaults in very mild terms.12 Some Arabic language newspapers are similarly equivocal in describing those attacks.13 Such newspaper accounts provide insufficient coverage to be useful for this study. Therefore, it is essential to note that each reported attack had to fit the foregoing definition of terrorism before it was included in the data base. Simply put, that definition served as a gatekeeper; some assaults chronicled in the Jerusalem Post as "terrorist acts" were excluded from the data base (e.g., assaults against military personnel on active duty), while other assaults, (e.g., specific incidents of vandalism) with generally recognizable political undercurrents were put in the data base.

CODING SCHEME AND FRAMEWORK OF ANALYSIS

The basic structure of the coding scheme consists of: "government urban or rural targets" (coded "government targets"); "non-government urban or rural infrastructure targets" (coded "infrastructure targets"); and "civilian targets." The first category includes government buildings such as courthouses, military administration and recruitment centers, non-combatant troops such as UN and US peacekeepers, and senior military personnel in non-combatant roles. Other "government targets" include major political actors, religious figures (e.g., the Pope), heads of state, parliament members and police officials. The category "infrastructure" includes, but is not limited to, energy facilities, oil pipelines, oil tankers, television and radio stations, bridges, and highways. "Civilian targets" include schools, civilian hospitals, commercial airliners, commuter buses, and marketplaces. This scheme makes it possible to code primary and secondary targets if necessary, by putting together the basic framework components listed above.14

With respect to perpetrators, an overwhelming number of terrorist events in this data base were carried out by groups or "proto-groups." Those attacks were either claimed by terrorist groups, or were attributed to them by the governments of Israel, the United States, other governments, or Jerusalem Post sources. In the case of "lone assassins," when attribution was not made by the aforementioned sources, I used "contextual analysis" (e.g., the presence or absence of a disclaimer of responsibility for the terrorist assault under consideration) to classify events as to such criteria as motivations of lone assailants and their links, if any, to terrorist organizations. In such cases, general corroboration was sought from more than one Jerusalem Post report. Other terrorism specialists have used "contextual analysis" to make coding decisions and probably have had to make similar "judgment call" decisions.15

It is probably no exaggeration to say that military and religious events that take place in the Middle East or are otherwise connected with it, have profound and lasting political implications for terrorist groups. Accordingly, political events cited in this study include military and religious events such as the Six Day War, the Yom Kippur War, the Lebanon War, Tish B'eav, Yom Kippur, Ramadan, Passover and Rosh Hashana. Several measures were used to establish causal relationships between "political events" and terrorist group attacks. These included Jerusalem Post attribution (e.g., Jerusalem Post sources and/or Israeli police/military sources, attribution made by other governments), terrorist group claims of responsibility as reported in the Jerusalem Post, Mickolus's attributions, occasional attributions made by other scholars, and "contextual analysis."

In the case of "contextual analysis" some relationships were relatively straightforward, such as the death of Emil Greenzweig at a "Peace Now" rally in 1983, and terrorist assaults happening on or a few days before Tish B'eav, Land Day, and the Balfour Declaration Anniversary. Others involved making connections between the terrorist event under consideration and widely known political events that preceded the attack. For example, several Americans and Germans were kidnapped in Beirut all within a few days in 1987, against the backdrop of articulated opposition by Arab extremists to US policy with respect to the prospect of West German extradition of Mohammad Hamadi to the United States and the emergent reality of American support for Iraq against Iran.16

The framework of analysis involves a discussion about broad trends in the behavior and the influence of each independent and intervening terrorism variable under consideration. Specifically, the analysis involves cross-tabulation analysis where relative percentages and frequencies for terrorist group-types are presented along with relevant significant test coefficients. The Pearson chi square statistic, degrees of freedom and p values are presented.17 With respect to this study of Middle East terrorism, the usefulness of cross-tabulation analysis is threefold. First, it makes it possible to determine whether or not a statistical association exists between terrorism variables under consideration. Second, because it is a presentation of observed rather than predicted values, cross-tabulation analysis is able to isolate and identify empirical trends in those data that will be used to test several hypotheses for validity. Third, cross-tabulation analysis serves as a springboard for more sophisticated analysis of terrorism.

At a functional level, in the bar charts and tables that follow, the number of missing cases may differ for four possible reasons. First, a piece of information missing from a terrorist attack entry (e.g., level of property damage) would result in exclusion of that entry from analysis of the variable under consideration. Second, in the case of "political events" analysis, the category "reaction to religious events," with two terrorist assaults, was deleted because of conceptual overlap with the category "commemoration of religious holidays." In the case of the distribution of terrorist assaults by group, the group "Palestine Liberation Army (PLA)," with two assaults attributable to it, was removed because of overlap between PLA and the Palestine Liberation Organization.18 Third, collaborator killings were excluded from the cross-tabulation analysis because such attacks would skew the results. Fourth, terrorism event entries from January 1968 to August 1978 were excluded from the test to determine frequency by year because of the non-randomness associated with the way those events were extracted from Mickolus's compilation.

For definition purposes, "percent" indicates the percentage of the frequency of a value, like "0 injury," for the total number of terrorist event entries (e.g., Figure 6., 776/1237 or .6273). In turn, a "valid percent" is the percentage of terrorism cases for a value, like "0 injury," with respect to the working data set for a particular test under consideration (e.g., Figure 6., 776/1180 or .6576). "Cumulative Percentage," by contrast, is an aggregate percentage of the valid percent of a value, like "1-50 injuries," coupled with the valid percents of values that came before. For example, the "cum percent" of the value "1-50 injuries" in Figure 6, is 98.2%, the sum of the valid percents 65.8% and 32.5%, taking "rounding off" into account. In turn, "cells with expected frequency less than 5" is a measure presented with some of the cross-tabulation analysis findings that describes the percent and number of cells with expected values of less than five observations.19 Finally, the minimum expected frequency figure presented with some cross-tabulation tests under consideration, really serves as a threshold marker for the minimum value of the chi square necessary to appraise, in a meaningful way, whether or not statistical associations exist between "terrorism variables."20

SOME GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ABOUT MIDDLE EAST TERRORISM

Relative Frequency of Incidents By Year

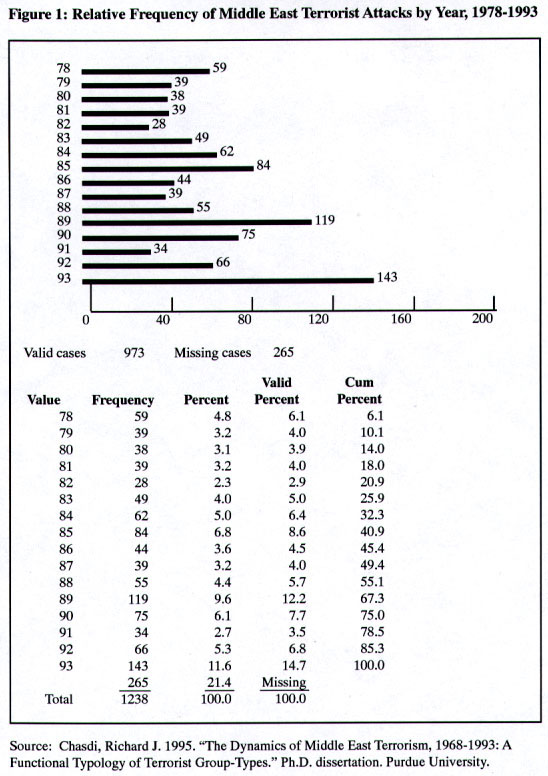

For the fifteen year period between 1978 and 1993, the data is comprised of 973 incidents of domestic, transnational, and international terrorism carried out by terrorist groups that either operate or originate in the Middle East and/or are bound up with Middle East politics. It is evident that Middle East terrorism of the sort described is characterized by distinct cycles of activity. That pattern is consistent with the findings of several studies.21

With respect to the range of incidents during this period, the smallest number occurred in 1982 when 28 attacks (2.9%) were carried out (see Figure 1). The "peak years" were 1978, 1985, 1989 and 1993. Fifty-nine incidents (6.1%) took place in 1978, as compared to 1985 when 84 terrorist incidents (8.6%) were carried out. In 1989, 119 terrorist acts (12.2%) occurred, while 143 incidents (14.7%) took place in 1993. Clearly, there has been a general increase in the frequency of Middle East terrorism from 1978 to 1993.

FIGURE 1: Relative Frequency of Middle East Terrorist Attacks by Year, 1978-1993

Terrorist Acts by Group-Type and Location

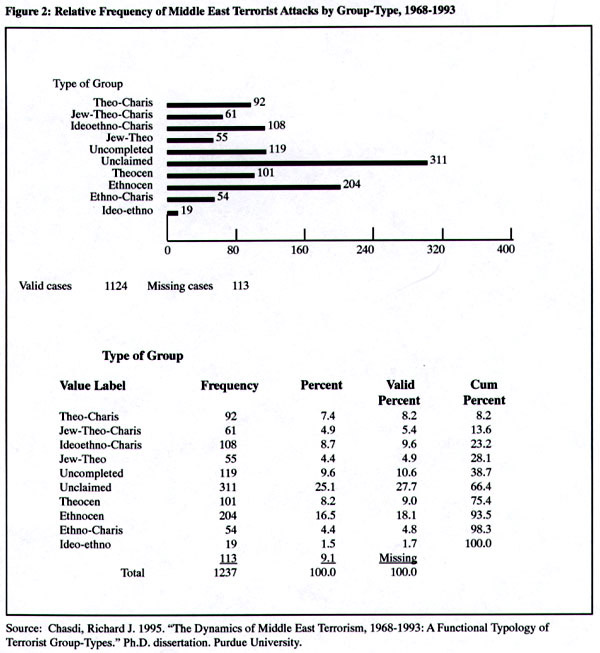

A breakdown of terrorist incidents by group-type reveals which types of terrorist groups have carried out the greatest number of incidents between 1968 and 1993 (see Figure 2). The data show that ethnocentric terrorist groups carried out the largest number of acts with 204 incidents (18.1%) while the second largest number of acts were carried out by ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups with 108 incidents (9.6%). Theocentric groups carried out the third largest number of acts with 101 incidents (9.0%). At the other extreme, the fewest number of incidents were committed by ideo-ethnocentric groups with 19 incidents (1.7%).

FIGURE 2: Relative Frequency of Middle East Terrorist Attacks by Group-Type, 1968-1993

Among Islamic fundamentalist terrorist groups, theocentric groups carried out 101 acts (9.0%) while 92 incidents (8.2%) were attributable to theocentric charismatic groups. Among Jewish fundamentalist terrorist groups, 61 terrorist acts (5.4%) were attributed to Jewish theocentric charismatic groups while 55 incidents (4.9%) were carried out by Jewish theocentric groups. Terrorist incidents that were thwarted by government agencies or aborted by the group itself amounted to 119 incidents (10.6%). What stands out here is that the single, largest number of terrorist incidents were unclaimed acts: 311 (27.7%).

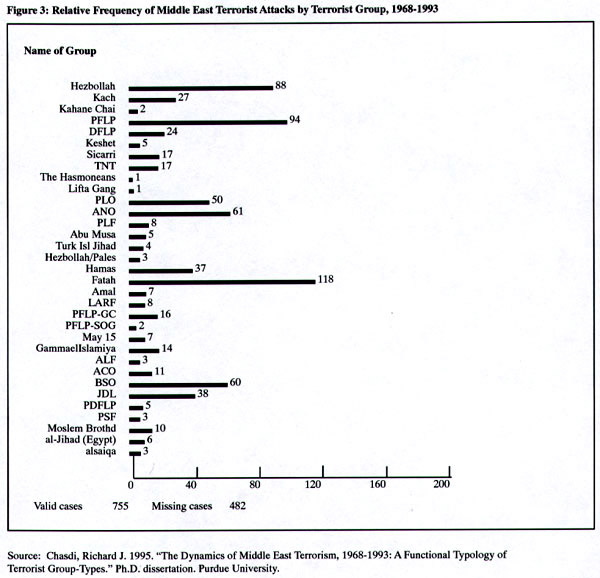

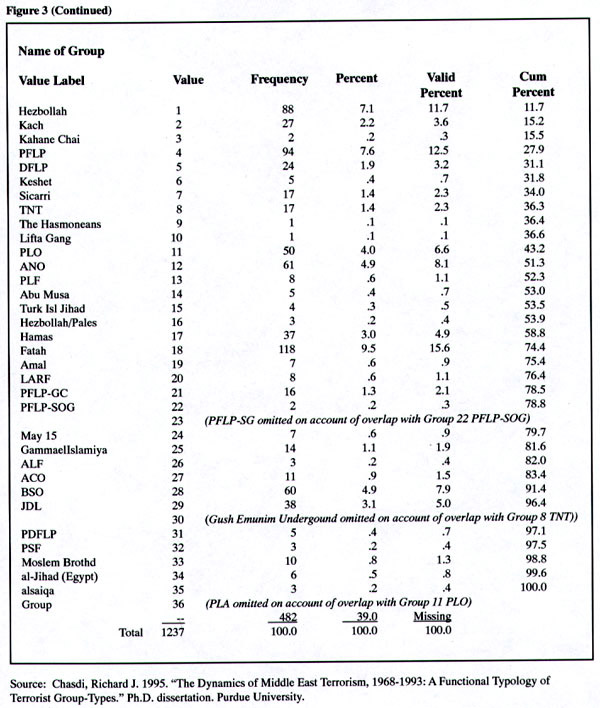

FIGURE 3: Relative Frequency of Middle East Terrorist Attacks by Terrorist Group, 1968-1993

FIGURE 3: Continued

If the analysis is directed toward particular terrorist groups it becomes clear which groups carried out the greatest and the fewest number of terrorist acts from 1968 to 1993 (see Figure 3). Among Arab and/or Islamic fundamentalist groups, the most prolific group was al-Fatah, which carried out 118 acts (15.6%). Following closely behind, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and Hezbollah committed 94 acts (12.5%) and 88 acts (11.7%) respectively. The least dynamic group among Arab and/or Islamic fundamentalist groups was the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - Special Operations Group (PFLP-SOG) which carried out two incidents (.3%). Other low activity terrorist groups include the Arab Organization of 15 May, which carried out seven acts (.9%), the Popular Struggle Front (PSF) which engaged in three incidents (.4%), and the Arab Liberation Front (ALF) which committed three incidents (.4%).

Among Jewish terrorist organizations, the Jewish Defense League (JDL) was most active, having carried out 38 incidents (5.0%). The second most active organization was the JDL offshoot Kach, which carried out 27 incidents (3.6%). The least dynamic Jewish terrorist organizations include the Hasmoneans with one incident, the Lifta Gang with one incident, and Kahane Chai with two incidents. Again, a large number of incidents (482 or 39%) were not claimed by or attributed to a specific group.

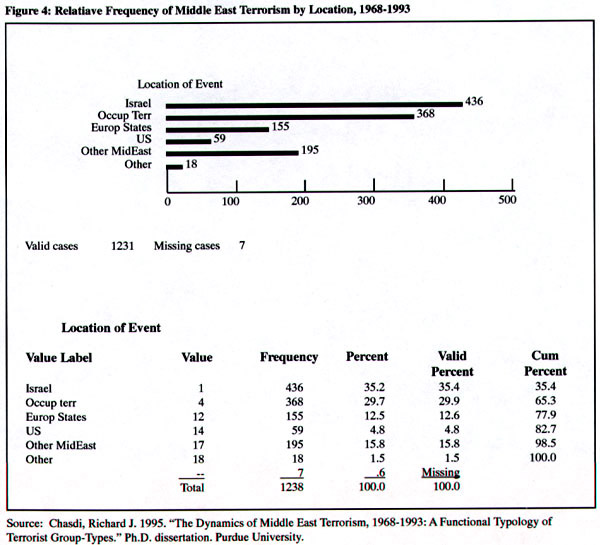

An analysis of terrorist incidents by location (see Figure 4) reveals that the largest number of terrorist attacks took place in Israel, where 436 incidents (35.4%) occurred. The second largest number of incidents occurred in the Occupied Territories with 368 incidents (29.9%). Somewhat ironically, the number of terrorist acts perpetrated by Middle East terrorist groups in Europe (155) (12.6%) was almost equal to the number that happened at other Middle East locations: 195 (15.8%). The smallest number of terrorist attacks took place in the United States with 59 incidents (4.8%).22

FIGURE 4: Relative Frequency of Middle East Terrorism by Location, 1968-1993

Terrorist Act Characteristics:

Fatalities, Injuries, Property Damage, Target Preference

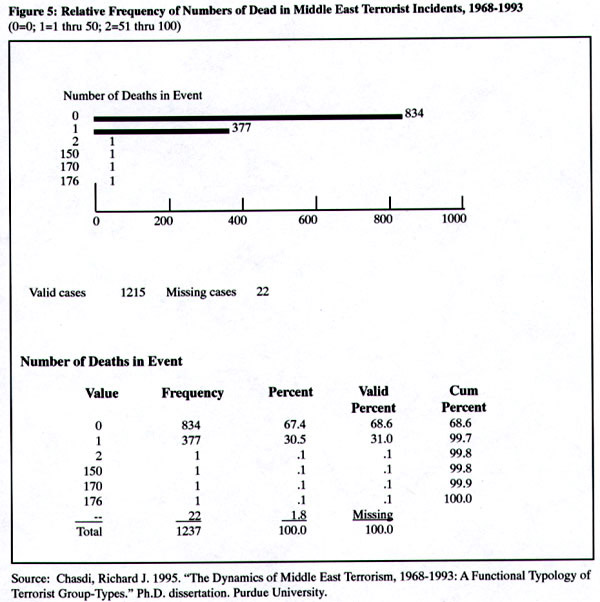

Scholars and policy makers shared a widely held belief that terrorism does not cause large numbers of fatalities and injuries or a substantial amount of property damage.23 That notion is supported by the analysis. For example, only 377 incidents (31.0%) out of 1,215 resulted in the deaths of between one and fifty persons. In fact, eight hundred and thirty four incidents (68.6%) that took place between 1968 to 1993 did not cause any deaths (see Figure 5). Further, the number of terrorist incidents that resulted in over fifty deaths was only four. Those incidents constitute outlier observations, which means that while the sample distribution of terrorist incidents is bell shaped, those observations lie several standard deviations away from the mean for numbers of dead.24 Nonetheless, a common thread powerfully ties together those "high intensity" terrorist acts. In all four of those extreme outlier observations, the location of the event was at a site outside of Israel and the Occupied Territories.25

FIGURE 5: Relative Frequency of Numbers of Dead in Middle East Terrorist Incidents, 1968-1993

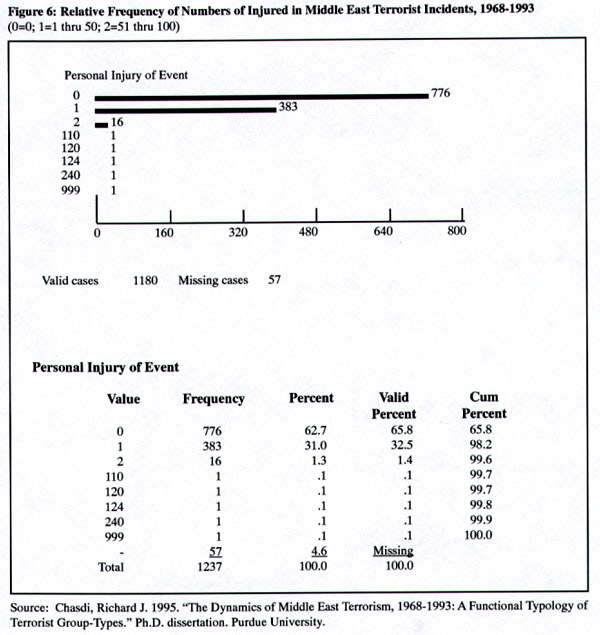

In a similar vein, terrorist attacks resulted in relatively low numbers of injured persons when compared to the number of people injured in incidents of other forms of political violence.26 For instance, only 383 incidents (32.5%) out of 1,180 resulted in injuries to between one and fifty persons. In fact, 776 (65.8%) incidents that happened between 1968 and 1993 did not cause any injuries (see Figure 6). Likewise, the number of terrorist incidents that caused injuries to between 51 and 100 persons was only 16 (1.4%). Further still, only five incidents caused injuries to over one hundred people. Clearly, those results mirror the findings of the distribution of death rates since these five incidents took place outside of Israel and the Occupied Territories.27

FIGURE 6: Relative Frequency of Injured in Middle East Terrorist Incidents, 1968-1993

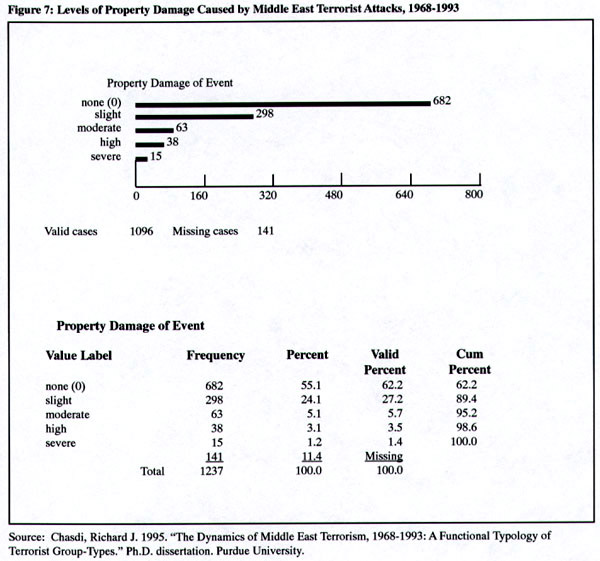

These attacks also caused relatively low levels of property damage. There were 682 incidents out of 1,096 (62.2%) where no property damage resulted. In 298 acts (27.2%), only slight damage, defined as less than or about $15,000, was caused. Moderate damage, defined as from about $30,000 to $100,000 was inflicted in 63 incidents (5.7%). High levels of damage, defined as from about $100,000 to $1 million, was inflicted in 38 incidents (3.5%). Severe damage in excess of $1 million was caused in 15 incidents (1.4%) (see Figure 7).

FIGURE 7: Levels of Property Damage Caused by Middle East Terrorist Attacks, 1968-1993

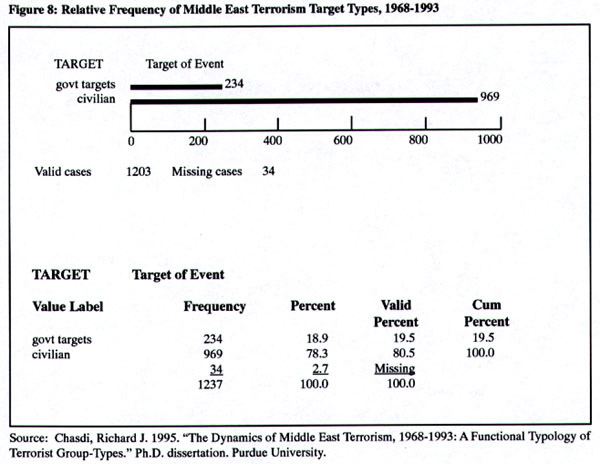

A breakdown of terrorist incidents by target type reveals that an overwhelming number were directed against civilian targets. Nine hundred and sixty-nine incidents (80.5%) out of 1,203 involved civilian targets as compared with 234 incidents (19.5%) that involved government targets. Thirty-four incidents (2.7%) involved infrastructure or multiple target combinations (see Figure 8).

FIGURE 8: Relative Frequency of Middle East Terrorism Target Types, 1968-1993

The foregoing analysis leads to several conclusions about the basic parameters of Middle East terrorism. First, like terrorism in other parts of the world, terrorism in the Middle East has a cyclical configuration. The frequency of terrorist attacks ebb and flow in regular patterns. Equally important, there has been a significant increase in Middle East terrorism between 1968 and 1993. Second, the data show that the ethnocentric group-type was the most dynamic in the region between 1968 and 1993. The ideo-ethnocentric charismatic group-type placed second, but that category was only about half as active as the former. An identical pattern is revealed at the group level, where the most active was the ethnocentric group al-Fatah, followed by an ideo-ethnocentric charismatic group, the PFLP.

Third, with respect to location, the largest number of Middle East terrorist attacks took place in Israel, followed by the Occupied Territories which has been under Israeli control since the 1967 Six Day War. Equally important is the finding that Europe has been plagued with almost as much Middle East terrorism as other parts of the Middle East between 1968-1993.

Fourth, the analysis shows that most Middle East terrorist events cause relatively few casualties and little property damage. While devastation rates remain low consistently, incidents of terrorism that are outlier observations happen outside of Israel and the Occupied Territories. That finding is consistent with the idea that the quality of counter-terrorism measures affects the overall impact of terrorism. Sadly, the bleakest conclusion is that the widely shared conception that Middle East terrorists are bent on attacking civilians is true. While the degree of physical devastation remains low, terrorists favor assaults on civilian targets by a margin of more than 4:1 (see Figure 8).

VARIABLE ANALYSIS

Political Ideology and Target Selection

This section will examine the validity of the following hypotheses that derive from the work of several well-known terrorism specialists:28

Hypothesis One: Ideo-ethnocentric terrorist groups will attack government targets more often than ethnocentric, theocentric and Jewish theocentric terrorist groups

Hypothesis Two: Theocentric terrorist groups will attack civilian targets more often than ethnocentric terrorist groups

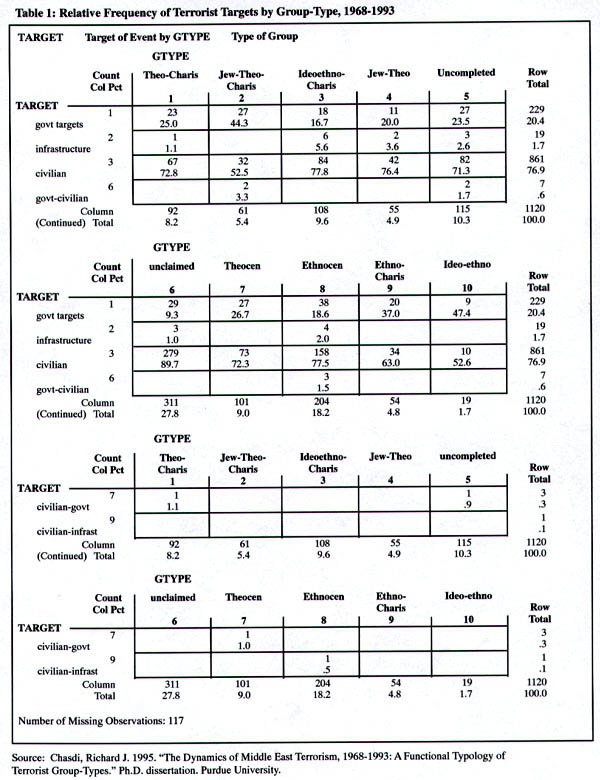

Analysis of the influence of group ideology on target selection indicates a statistical association between the political ideology of a terrorist group and the type of target chosen. That suggests a systematic and substantive relationship between those variables.29 A breakdown of the data shows that ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups had the highest rate of terrorist attacks directed at civilian targets: 84/108 acts (77.8%). Ethnocentric groups had the second highest percentage of attacks against civilian targets: 158/204 acts (77.5%) (see Table 1). In turn, Jewish theocentric groups had the third highest percentage of attacks of this sort: 42/55 acts (76.4%).

At the other extreme, Jewish theocentric charismatic groups and ideo-ethnocentric groups had the lowest rates of civilian target attacks. These were, 32/61 (52.5%) and 10/19 acts (52.6%) respectively. Ethnocentric charismatic groups had the second lowest percentage of attacks against civilian targets: 34/54 acts (63.0%).

In contrast, ideo-ethnocentric groups had the highest percentage of attacks aimed at government targets: 9/19 acts (47.4%). Jewish theocentric charismatic groups had the second highest rate of attacks against government targets: 27/61 acts (44.3%). Ethnocentric charismatic groups had the third highest percentage of attacks of this kind: 20/54 incidents (37.0%).

TABLE 1: Relative Frequency of Terrorist Targets by Group-type, 1968-1993

Attention to target types that do not fall into "civilian" or "government" categories brings the outlier cases into sharp focus. Ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups had the largest percentage of attacks against infrastructure: 6/108 incidents (5.6%). Ethnocentric groups attacked infrastructure only 2% of the time (4/204 acts), but that was the second highest percentage recorded. Middle East terrorist attacks that involved multiple targets were even more infrequent. Jewish theocentric charismatic groups had the highest rate of attacks where the primary target was a government facility and a civilian target was secondary. Attacks of that sort accounted for a mere 3.3% (2/61) of events attributable to that group-type. Ethnocentric groups had the second highest rate of attacks of this kind: 3/204 incidents (1.5%).

Conversely, theocentric charismatic and theocentric groups had the highest percentage of attacks where the primary target was civilian and a government target was secondary. In both cases, that kind of attack accounted for a mere 1% of the total number of events for each group-type. Finally, ethnocentric groups were the only type to engage in attacks where the primary target was civilian and the secondary target was infrastructure. Attacks of that sort accounted for only .5% (one incident) of all incidents carried out by ethnocentric groups.

There were a considerable number of uncompleted and unclaimed terrorist attacks against civilian targets. In the case of uncompleted acts, 82/115 incidents (71.3%) involved civilian targets, while 27/115 acts (23.5%) involved government targets. For unclaimed acts, the rate was even higher: 279/311 attacks (89.7%) aimed at civilian targets, while only 29/311 (9.3%) were aimed at government targets. Clearly, that pattern is consistent with the demonstrated preference for civilian targets by the other group-types under consideration.

The foregoing evidence and analysis supports the first hypothesis. I found that ideo-ethnocentric terrorist groups attacked government targets 47.4% of the time, and ethnocentric, theocentric and Jewish theocentric groups only attacked government targets in 18.6%, 26.7% and 20.0% of attacks, respectively. In contrast, the findings do not support hypothesis two. Theocentric terrorist groups carried out 72.3% of attacks against civilian targets, but ethnocentric terrorist groups carried out 77.5% of attacks against civilian targets.

One standout finding of the analysis is that nearly 90% (279/311) of unclaimed incidents were directed against civilian targets. Unclaimed acts accounted for 27.8% (311/1,120) of the total, making it the single, largest category of terrorist acts. It is possible to extrapolate from those findings and suggest that in the absence of accountability, the rate of terrorist group civilian target attacks will increase. Those data suggest that if the cause and underlying themes of a political struggle and the goals of both sides are sufficiently clear, it may be in the interest of a terrorist group to engage in some degree of anonymous activity, provided there are other terrorist groups active in the political fray.30

POLITICAL IDEOLOGY AND NUMBERS OF DEAD

Hypothesis Three: Theocentric terrorist groups will have a higher percentage of terrorist acts that cause deaths than acts committed by ethnocentric and ideo-ethnocentric terrorist groups.

The significance testing indicates a statistical association between the political ideology of a terrorist group and numbers of deaths sustained in a terrorist attack.32 Theocentric groups had the highest percentage of incidents in which one to fifty persons were killed: 55/96 acts (57.3%). Ethnocentric charismatic groups ranked second in that category: 30/54 incidents (55.6%). By comparison, Jewish theocentric charismatic groups had the lowest rate: 3/61 (4.9%).33 The latter also had the highest number of non-lethal incidents: 58/61 (95.1%). Jewish (non-charismatic) theocentric groups were responsible for the second highest total of non-lethal events: 47/53 (88.7%).

One notable statistic is that over 87.7% of unclaimed incidents (271/309) caused no loss of life. Some 12.0% of all unclaimed acts (37) caused the deaths of between one and fifty people. Those findings are consistent with the idea that many unclaimed acts are rather "unspectacular," involving smaller explosive devices and other weapons capable of only low-level damage.34

Hypothesis three is supported by the results, which found that 57.3% of theocentric group attacks caused the deaths of between one and fifty people. In contrast, 35.2% of attacks by ethnocentric terrorist groups and 47.1% of attacks by ideo-ethnocentric terrorist groups caused deaths in that same range. What also is significant is that Jewish groups acted differently than other terrorists. Since an overwhelming amount of Jewish terrorism happened in Israel, the Occupied Territories and the United States, and the relative frequency figures were so low, those findings probably reflect the fact that they operated predominantly in "friendly" areas.35

Interpreting those findings further may suggest that leaders of those organizations refrained from overly bloody assaults in part because they saw their groups, to use Bruce Hoffman's phrase, as "political pressure groups" that could have some effect on the political process and public policy outcomes.36 It is not unreasonable to extrapolate from this and surmise that Jewish theocentric terrorist groups in Israel also viewed low-level violence as necessary for effective participation in the political system.37

Rabbi Meir Kahane's comments about the role that violence plays within the context of the Jewish religious and historical experience and JDL activity in the US during the early 1970's provides insight into this way of thinking. Kahane said, "The Jewish concept of violence is that it's a bad thing - but sometimes necessary. I can bring in a hundred quotes. And not just quotes but events in Jewish history. Innocent people should never be harmed. The Jewish concept is that no one pays for the sins of anyone else."38 The emergent reality is that the exceptions to this are the Jewish extremists, such as those who live in Hebron, who often subject Palestinians to intimidation and the use of force. In fact, the threat, use, or promotion of force by Jewish extremists in the Occupied Territories is entirely consistent with the definition of terrorism used in thus study.

POLITICAL IDEOLOGY AND NUMBERS OF INJURIES

Hypothesis Four: Theocentric terrorist groups will have a higher percentage of terrorist acts that cause injuries than acts committed by ethnocentric and ideo-ethnocentric groups

There is a statistical association between the political ideology of a terrorist group and numbers of injuries that are caused in terrorist attacks. That finding indicates that those variables are statistically correlated.40 Ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups and ethnocentric groups were responsible for the highest percentages of events in which one to fifty persons were hurt: 51/102 incidents (50%), and 97/196 acts (49.5%) respectively. Alternately, Jewish theocentric charismatic groups carried out the fewest attacks in the 1-50 injury range: 4/59 (6.8%).41

Ideo-ethnocentric groups had the highest percentage of incidents in which between fifty-one and one hundred persons were injured: 2/17 (11.8%). Ethnocentric charismatic groups were second in that category: 3/52 events (5.8%). The extreme outlier cases for numbers of injured were discussed earlier in this article, but it is important to note here that only two theocentric incidents involved injuries to more than fifty people. Therefore, the breakdown by group-type presented here is consistent with the idea that terrorism in the Middle East produces relatively low numbers of dead and wounded.

At the other extreme, Jewish theocentric charismatic groups recorded the highest percentage of acts in which no injuries occurred: 55/59 (93.2%). Jewish theocentric groups were second: 41/52 incidents (78.8%). Likewise, nearly 67% of unclaimed acts (204/306) caused no injuries. Thus, only one-third of unclaimed acts (102/306) injured anyone at all.

It is clear that hypothesis four is not supported by the analysis. Ethnocentric terrorist groups caused injuries in 52.1% of attacks while theocentric and ideo-ethnocentric groups caused injuries in only 41.1% and 41.2% of attacks, respectively.42 At the same time, the findings about unclaimed terrorist acts are tantalizing. Clearly, injury and death rates are consistently low for acts perpetrated by anonymous groups, "lone operatives" and Jewish fundamentalist groups, suggesting that anonymous acts and acts carried out by Jewish terrorist groups perform a similar function. It seems plausible that unclaimed terrorist acts may introduce substantial pressure into the political system in much the same way it was suggested that many Jewish fundamentalist terrorist acts did. After all, the raison d'etre of unclaimed terrorist assaults is to remind the ruling elite of the need for substantive change.43

Political Ideology and Property Damage

Hypothesis Five: Ideo-ethnocentric terrorist groups will commit acts that result in greater amounts of property damage than acts committed by ethnocentric and theocentric terrorist groups

Based on the statistical association observed, the analysis indicates that there is a substantive relationship between those two variables.45 Jewish theocentric charismatic groups had the highest percentage of incidents in which slight damage resulted: 34/58 (58.6%). Ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups were second with 40/99 incidents (40.4%). Overall, terrorist attacks which caused only slight damage accounted for 30.1% (297/988) of the total number.

Terrorist incidents in which moderate damage was caused numbered 63/988 (6.4%). In this category, ideo-ethnocentric groups had the highest percentage: 2/15 (13.3%). Theocentric charismatic groups were next, with 10/83 incidents (12.%). By comparison, high and severe levels of property damage caused by Middle East terrorist assaults were very infrequent. Only 38/988 acts (3.8%) caused high levels of property damage. Ideo-ethnocentric groups had the greatest percentage of incidents that caused high levels of property damage: 4/15 (26.7%). Terrorist attacks that caused severe damage were extreme outlier cases that only made up 1.5% (15/988) of the total. Ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups had the highest rate of attacks of this kind: 6/99 (6.1%).46

At the other extreme, theocentric charismatic groups carried out the largest percentage of incidents in which no property damage occurred: 53/83 (63.9%). Jewish theocentric groups had an almost identical rate: 31/51 (60.8%). Anonymous terrorist assaults were almost as likely not to inflict property damage. No property damage occurred in 158/272 unclaimed acts (58.1%). In the case of anonymous terrorist assaults, when property damage did happen, the damage was slight nearly one-third of the time.47

Those findings about ideo-ethnocentric terrorist groups are the expected results. Nearly three-quarters of the acts they committed caused some type of property damage; somewhat more than one-quarter of those caused high levels of damage. Ethnocentric charismatic groups came in a very distant second with 4/44 acts (9.1%). Moreover, that pattern is very similar for other property damage categories. Clearly, those findings are consistent with the underlying theme that Marxist-Leninist terrorist groups in the Middle East devote special attention to property destruction.

Location and Target Selection

Hypothesis Six: Terrorist attacks in Israel will have the highest percentage of attacks aimed at civilian targets while terrorist attacks in the Occupied Territories will have the second highest percentage of attacks aimed at civilian targets

Location is the fourth independent variable that is statistically associated with target type. The analysis suggests a substantive and systematic relationship between those variables.49 The analysis reveals that the Occupied Territories ranked first in attacks against civilian targets: 336/367 (91.6%). Israel ranked a close second: 389/433 (89.8%). European states came in a distant third: 106/155 (68.4%). That ranking order is reversed for government targets of terrorist assaults. The smallest percentage of attacks against government targets was in the Occupied Territories: 29/367 (7.9%). Israel experienced a few more: 36/433 (8.3%). European states had the highest rate: 45/155 events (29.0%) (see Table 2).

With respect to other target types, infrastructure was attacked in 6/195 acts (3.1%) in the Middle East outside of Israel and the Occupied Territories. Israel ranked second: 7/433 (1.6%) and European states ranked third: 2/155 acts (1.3%). Terrorist attacks that involved multiple targets were extreme outlier observations. What stands out however is that the United States ranked first in attacks that involved multiple targets: 4/59 acts (6.8%).

Those findings are inconsistent with hypothesis six. In fact, they reversed the order suggested in the hypothesis. Nonetheless, the difference between those values is small. Presumably, this reflects some small difference in anti-terrorist security measures and/or effectiveness, or indicates that the attack rates are virtually the same in both locations.

POLITICAL EVENTS AND TARGET SELECTION

One fundamental question that has been relatively neglected by researchers is whether or not a connection exists between Middle East terrorism and political events that take place in the region or are otherwise connected to it. In other words, does terrorism in the Middle East happen largely in response to political activity or is terrorism comprised mostly of "independent" events?

The idea that terrorism may be largely a reactive rather than a proactive endeavor is based on Brecher and James' model of political violence in the Middle East.50 The following hypothesis captures the substance of that model:

TABLE 2: Relative Frequency of Target Type by Location, 1968-1993

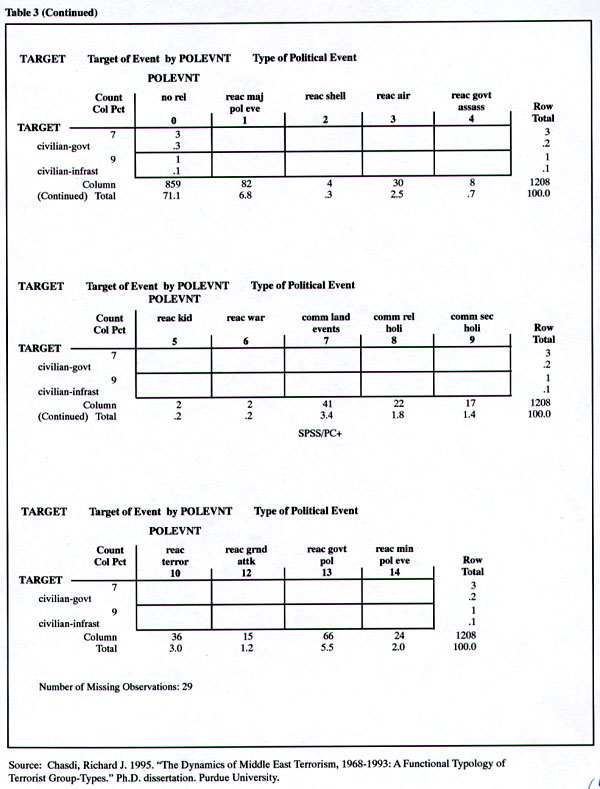

The analysis indicates there is a statistical association between the intervening variable (political events) and the type of target selected. Specifically, those findings mean that when terrorism is linked to political events, there is a statistical association between the type of political event that occurs and the target type that is chosen.51

TABLE 3: Relative Frequency of Target Type by Political Event, 1968-1993

TABLE 3: Continued

However, a complete breakdown of the data makes it clear that most terrorist incidents were unrelated to political events. Incidents that had no relationship to political events comprised the largest proportion of the total: 859/1208 (71.1%). Of those 859 incidents, 684 (79.6%) were directed at civilian targets (see Table 3).

The remaining categories of "political events" are comprised of outlier observations. The largest of those categories (82) (6.8% of the total) consists of terrorist events that occurred in response to major political events, such as diplomatic initiatives. While such attacks formed the bulk of the outlier cases, they were not characterized by an especially sharp focus against the general population. Only about three-quarters of those attacks (62/82) involved civilian targets. Those findings may reflect the largely "symbolic" nature of those attacks, which were launched in protest against particular political initiatives.

Terrorist activity undertaken in response to government policy at the national level, such as Israeli support for the Lebanese militia in southern Lebanon, formed the second largest group of outlier observations. While over half of those attacks (38/66) (57.6%) involved civilian targets, 39.4% involved government targets. That figure represents the highest number of "reactive" terrorist assaults against government targets. Attacks in commemoration of landmark events, such as the anniversary of the Sabra/Shatilla massacre, comprised the third largest outlier category, but that was only 3.4% of the total. However, these attacks yielded the second highest rate of attack against civilians: 38/41 incidents (92.7%).

By comparison, terrorist actions in reaction to war and government counter-terrorist assassinations, were very rare occurrences. Terrorist attacks undertaken in reaction to war only comprised .2% of 1,208 acts and always involved civilian targets (2/2 acts). Terrorist incidents committed in reaction to counter-terrorist assassinations amounted to only .7% of the total. Those attacks had the highest percentage of assaults against infrastructure: 1/8 (12.5%). In turn, terrorist incidents carried out in commemoration of religious holidays had the second highest percentage (4.5%) of attacks against infrastructure, but that was only one incident. Likewise, terrorist attacks undertaken to commemorate secular holidays had the highest percentage (5.9%) of attacks against multiple targets, but again this involved only a single event.

Clearly, the results of the analysis are inconsistent with hypothesis nine and as a result, that hypothesis is rejected. At the same time, the analysis suggests that proactive activities carried out by government agencies may elicit terrorist responses that resonate with similar thematic emphases. For example, "symbolic" political initiatives seemed to be matched by "symbolic" terrorist activity. Similarly, the analysis shows that government policy outputs evoked the highest number of "reactive" terrorist attacks aimed at government targets.

The analysis also suggests that events that exert a powerful pull on visceral emotions, such as the commemoration of landmark events, prompted terrorist attacks that focused greater attention on civilian targets. Likewise, violent government activity that affected large numbers of people directly, perhaps even profoundly, elicited terrorist attacks that matched the fundamentally invasive and thereby "intimate" nature of those government activities with equivalent intensity against civilians. For example, 86.7% of attacks in reaction to air-strikes involved civilian targets, while 93.3% and 100% of attacks in reaction to ground attacks and war respectively, involved civilian targets.

CONCLUSIONS

General Trends

Cross-tabulation analysis provides valuable insight into understanding Middle East terrorism by revealing its broader characteristics and variations according to group-type. At the most basic level, the analysis reveals that while there has been a general increase in Middle East terrorism in absolute terms since 1968, the frequency of Middle East terrorism ebbs and flows in a cyclical configuration.

Another rudimentary finding concerns where Middle East terrorism takes place. While an overwhelming number of terrorist incidents happened in Israel and the Occupied Territories, European nations were afflicted nearly as much as Middle East locations outside of Israel and the Occupied Territories.

The analysis shows that ethnocentric groups were the most dynamic type of group between 1968-1993. Ethnocentric groups carried out 204 acts of terrorism during that period. Ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups were the second most active type of group, carrying out 108 acts. However, the largest number of acts were committed by anonymous terrorist organizations or "lone operatives." Unknown groups or "lone operatives" launched over 300 acts between 1968 and 1993. When the analysis is focused at the group level, similar trends in the data are discernable. For example, al-Fatah carried out the highest number of terrorist acts (118) followed by 94 acts credited to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).

The widely shared belief that terrorists focus primary attention against civilians in pursuit of political goals is supported by the results. When all locations are included in the analysis, Middle East terrorists favored attacks against civilian targets by a margin of over 4:1. When the locations Israel and the Occupied Territories are examined separately, that ratio increased to approximately 10:1 (see Figure 8 and Table 2). Irrespective of location, however, the results indicate that in addition to a focus on civilian targets, terrorist assaults linked to the Middle East remained relatively straightforward operations that usually involved one target. Incidents involving multiple targets were extremely rare occurrences that comprised only some 1% of all terrorist incidents (see Table 1).

What degree of damage does Middle East terrorism cause? The analysis shows that the costs of Middle East terrorism, if measured in purely physical terms have been low. The sample mean for numbers of dead is 1.454 and the sample mean for numbers of injured is 4.639.52 Comparable low levels of property damage from Middle East terrorist assaults were recorded. More than half of all incidents caused no property damage, and less than 4% resulted in high levels of property damage.

The Role of Political Ideology

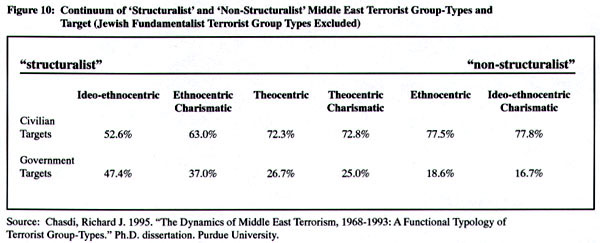

How do these data support the theoretical framework described at the start? The continuum for non-structuralist and structuralist terrorist group-types is presented and overlaid with data on non-charismatic group-types and target-type with good results (see Figure 9):

FIGURE 9: Continuum of 'Structuralist' and 'Non-Structuralist' Middle East Terrorist Group-Tpes for Non-charismatic Group-types and Target (Jewish Fundamentalist Terrorist Group-types Excluded)

Political ideology is found to be influential in terms of what type of target was chosen. The analysis determines that ideo-ethnocentric terrorist groups attacked government targets more often than ethnocentric and theocentric groups, as well as Jewish theocentric terrorist groups. This finding strongly supports the notion that "structuralist" Middle East terrorist groups carry out terrorist attacks that place more emphasis on government targets.

At the same time, the analysis reveals that ethnocentric terrorist groups attacked civilian targets more frequently than theocentric groups. At the start, I believed that Islamic fundamentalist terrorist groups and nationalist-irredentist groups were both "non-structuralist" in nature.53 These findings, however, seem to suggest that theocentric groups, while less "structuralist" than "Marxist-Leninist" groups, are more "structuralist" than ethnocentric groups. At a theoretical level, that approach seems justifiable since Islamic fundamentalism not only focuses heavily on an individual's declared loyalties and beliefs, but is "structuralist" in the sense that it perceives the world as essentially divided up between an Islamic East and hordes of "unbelievers" under the control of a Christian West.54

The analysis of terrorism "attribute" variables is less supportive of the theory that drives this work. Having said that, location as an explanatory variable may not only explain why Jewish terrorism remains consistently low in terms of intensity, but seems to explain, inter-alia, why death rates for ethnocentric groups, clearly a "deviant finding," seem to be muted.

In the case of ethnocentric groups, the death rate is comparatively low. One possible explanation for that finding is that a full 42.9% of ethnocentric attacks took place in Israel, while only 13.9% of theocentric attacks happened in Israel. Ethnocentric group-type death rates are likely influenced by that distribution. Ethnocentric group-type death rates may be low because of two factors that work alone or in tandem. At a functional level, Israeli counter-terrorism measures may make terrorist assaults with very high death rates difficult to carry out. At a political level, ethnocentric groups are the type of terrorist group most interested in a political settlement with Israel. If ethnocentric assaults crossed a threshold of "acceptable" numbers of deaths, they would have elicited the looming catastrophe of decisive Israeli retaliation that would have more than offset any political gains made.55

Location

Seen from another angle, the cross-tabulation results also indicate that location of the terrorist assault heavily influences the target selection process. Terrorist attacks in the Occupied Territories had the highest percentage of attacks against civilian targets, while attacks in Israel had the second highest rate. The European states placed a distant third. While those first and second place rankings are not the expected findings, the results are consistent with the idea that the frequency of attacks involving civilians in Israel and the Occupied Territories is greater than in other locations. Moreover, while those findings are inconsistent with hypothesis six, the difference in attack frequency rates between locations is very small. As mentioned previously, those findings either reflect some small difference in anti-terrorism measures or their implementation, or suggest that attack rates are basically the same in both locations.

Charismatic Leadership: Impact on Islamic Fundamentalist,

Marxist-Leninist and National-Irredentist Terrorist Groups

One of the underlying themes of this study is that charismatic leaders of Arab/Islamic fundamentalist terrorist groups influence terrorist group behavior. While the data support that idea in some cases, many of the results do not conform with predictions made earlier in this study. The following is a summary of the findings about charismatic leadership for Islamic fundamentalist, Marxist-Leninist and nationalist-irredentist terrorist groups.

FIGURE 10: Continuum of 'Structuralist' and 'Non-Structuralist' Middle East Terrorist Group-Types and Target (Jewish Fundamentalist Terrorist Group-types Excluded)

The data suggest the presence of a charismatic leader at the helm of Islamic fundamentalist terrorist groups makes little difference in terms of target selection and intensity of attack. For example, while theocentric charismatic groups attacked civilian targets in 72.8% of all attacks, theocentric groups did so in 72.3% of attacks. With respect to intensity of attacks, the observed data show that while a lower percentage of theocentric charismatic group attacks killed between one and fifty persons, a higher percentage of theocentric charismatic attacks injured between one and fifty persons. What seems significant here is the connection between numbers of deaths in terrorist assaults and location as an explanatory variable. A full 36% of theocentric charismatic attacks took place in Israel and the data show that only 29.2% of theocentric charismatic attacks killed between one and fifty persons. By contrast, only 13.9% of theocentric attacks took place in Israel and 57.3% of theocentric attacks killed between one and fifty persons.56

The analysis fails to reveal any pattern in terms of property damage levels caused by Islamic fundamentalist terrorist assaults. For example, while theocentric and theocentric charismatic groups had the same percentage of attacks that caused high amounts of property damage, theocentric groups had a much higher percentage of attacks that caused slight damage, whereas theocentric charismatic groups had a much higher percentage that caused moderate damage. Interestingly enough, the results suggest location is not an explanatory variable for lower amounts of property damage. For example, with over one-third of theocentric charismatic attacks in Israel, a full 12% of them caused moderate property damage. That figure is nearly three times greater than the amount for theocentric groups (4.7%), which attacked targets in Israel only 13.9% of the time.57

In the case of Marxist-Leninist terrorist groups, the data generally support the proposition that groups led by a charismatic leader commit terrorist acts that more closely resemble incidents carried out by other types of groups calling for a Pan-Arab or Pan-Islamic Middle East. The strongest evidence of a link between an increase in violence against the general population and the presence of a charismatic leader is found in the analysis of target choice. A breakdown of the data reveals that while ideo-ethnocentric group attacks involved civilian targets in nearly 53% of all incidents, close to 78% of ideo-ethnocentric charismatic group attacks were directed at civilian targets.

Analysis of the intensity of terrorist incidents carried out by ideo-ethnocentric and ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups seems to be, prime facie, less supportive of that relationship. For example, the data show that a greater percentage of ideo-ethnocentric group attacks killed between one and fifty persons than ideo-ethnocentric charismatic attacks. Meanwhile, ideo-ethnocentric charismatic groups had a much higher percentage of attacks that wounded between one and fifty persons than did ideo-ethnocentric groups. However, analysis of location and group type suggests location as an explanatory variable. While nearly two thirds of all ideo-ethnocentric charismatic group attacks took place in Israel and the Occupied Territories, there were no attacks by ideo-ethnocentric groups in those locales. In fact, analysis shows that nearly 58% of all ideo-ethnocentric attacks were carried out in other Middle East countries like Syria and Lebanon. The remaining 42% of ideo-ethnocentric assaults took place in Europe.58

In the case of nationalist-irredentist terrorist groups, the data suggest the presence of a charismatic leader has an influence on target type and intensity, although that influence is different for each. It is observed that ethnocentric terrorist groups carry out civilian target attacks (77.5%) more frequently than ethnocentric charismatic groups (63.0%). For ethnocentric charismatic groups, the roughly "60-40" split between civilian and government targets mirrors the Abu Nidal Organization's seemingly more balanced targeting of civilian and government targets.59

With respect to intensity, however, nearly 56% of ethnocentric charismatic group attacks killed between one and fifty persons as compared to 35.2% for ethnocentric groups. Likewise, nearly 54% of ethnocentric charismatic attacks caused injuries to between one and fifty persons as compared to slightly less than 50% for ethnocentric groups. Once again, location seems to be the explanatory variable for the different findings about target choice and terrorist assault intensity. Very few ethnocentric charismatic attacks took place in Israel (4/54) (7.4%), while 42.9% of ethnocentric attacks happened in Israel.60

The Behavioral Patterns of Jewish Fundamentalist Terrorist Groups

One of the cornerstones of the theory that drives this study is that Jewish fundamentalist terrorist groups ought to attack targets with less intensity than their Islamic counterparts. The results of the analysis about the characteristics of "Jewish terror" strongly support that idea.61 Specifically, the data show that Jewish theocentric charismatic groups had the highest percentage of non-lethal incidents, while Jewish theocentric groups had the second highest amount. The analysis also reveals that Jewish theocentric charismatic groups had the highest percentage of injury-free attacks while Jewish theocentric groups came in second place. Finally, it is observed that neither Jewish theocentric charismatic nor Jewish theocentric groups committed acts that caused high amounts of property damage. In fact, only around two percent of all acts for both group-types resulted in even moderate amounts of damage. To be sure, some 93% of Jewish theocentric charismatic attacks happened in the "friendly" areas of Israel, The Occupied Territories and the United States. Indeed, a full 100% of Jewish theocentric attacks happened in Israel and The Occupied Territories alone.62

The data suggest that the reason for this self-styled restraint by Jewish fundamentalist terrorist groups is twofold. At one level, it seems obvious that the restraint shown served to prevent a crackdown by Israel's General Security Service. At another level, those findings suggest that leaders of those organizations refrained from undertaking devastating assaults on a consistent basis because they viewed their groups, to use Hoffman's expression, as "political pressure groups" that could influence the Israeli and/or American political systems.63 Furthermore, those findings suggest that systemic or structural factors (i.e., whether or not a terrorist group is "indigenous" or "exogenous" to the political system under attack) have significant effects on terrorist event characteristics.64

The Influence of Political Events

Middle East terrorism is found to be a largely proactive rather than a reactive undertaking. The analysis reveals that some 70.0% of all terrorist activity between 1968-1993 was unrelated to political events. When terrorism was linked to political events, there was a statistical association between target type and political event type. Furthermore, the analysis suggests that terrorist actions taken in response to particular political events share similar underlying themes with them. That finding has powerful implications for counter-terrorism policy. If there is evidence that indicates particular types of political events elicit attacks that place predictable emphasis on certain kinds of targets, more effective counter-terrorism policy can be crafted and implemented.

Terrorism by Anonymous Groups or "Lone Operatives"

Terrorist attacks by anonymous groups or "lone operatives" are found to be the most common type of attack between 1968 and 1993. In addition, nearly 90% of all unclaimed attacks involved civilian targets. For terrorist assaults against civilian targets, that percentage figure is the highest measure recorded for any category.

While the vast majority of unclaimed terrorist acts were aimed at the general population, those acts caused little damage. The percentage of anonymous terrorist assaults that caused at least one death or injury was comparatively low. In addition, nearly one-third of all anonymous attacks resulted in only a slight amount of property damage.

What seems significant here is the findings suggest that effective counter-terrorism measures are largely dependent on whether or not a terrorist group is identifiable. It follows that a "mixed bundle" of anonymous and claimed acts of terrorism that are low intensity in nature may be an effective strategy for terrorist leaders if the underlying themes and goals of the political struggle are sufficiently clear and other terrorist groups are active in the political fray.65 At a more theoretical level, the findings suggest that an important function of anonymous terrorist activity is to remind the ruling elite of the need for structural political change or accommodation.

Reflections

The cross-tabulation analysis makes it clear that the targeting practices of Middle East terrorist groups are based on much more than chance and opportunity. In fact, that analysis reveals discernible and at times dramatic patterns of terrorist group targeting behavior when Middle East terrorist groups are broken down according to three defining characteristics: ideology, goals, and recruitment patterns.66 Inasmuch as those results begin to shed light on which types of terrorist groups commit particular types of attacks, the set of interconnections between political events and the actions of various types of terrorist groups, and what the risks of Middle East terrorism are, this research lends itself to predictions about the future.

Plainly, while it is beyond the scope of this article to provide a "laundry list" of policy prescriptions for counter-terrorism planners, some insights about "target hardening" can be extrapolated from the data. First, while making efforts to generate or sustain security around potential civilian targets of terrorism is an ineluctable conclusion, the findings also suggest close attention should be devoted to potential targets on anniversaries and celebrations, and potential government targets when national policy directives are carried out.

Second, the data indicate special attention ought to be devoted to potential government targets with respect to Jewish fundamentalist, and Arab nationalist-irredentist groups with charismatic leaders, and Marxist-Leninist nationalist-irredentist groups without them. All of the aforementioned suggests that counter-terrorism planners might identify and sort out qualitative differences in policy directives, thereby in effect helping to prepare counter-terrorism contingency plans for types of intensity levels in terrorist attacks that seem bound up with specific kinds of policy directives. Equally important, linkages should be made between delineated "policy types" and terrorist groups affected, to promote better risk assessment. Bearing in mind that some terrorist assaults occur on anniversaries or to commemorate events, it follows that such a classification scheme might isolate and identify particular time periods where implementation of specific "policy types" is fraught with peril because of possible "joint effects" that presuppose and derive from political events and policy directives.

Third, trends in the data indicate that counter-terrorism planners should anticipate an overwhelming number of Middle East terrorism attacks that involve one target. What seems significant here however, is that counter-terrorism planners should prepare for the possibility of a shift in strategy, namely to attacks that involve multiple targets and perhaps, multiple target-type combinations. In essence, counter-terrorism planners need to introduce even more flexibility into the counter-terrorism system by means of additional resource acquisition, and enhanced organizational capacity both within and between government agencies, that may presuppose and derive from even more coordinated terrorist event and response "simulations."67

Fourth, since Middle East terrorism comprised a very high number of anonymous terrorist assaults, policy-making officials might consider ways to reduce that proportion. Because those attacks may be associated with a political setting in which the political goals of the state and several terrorist groups, perceived to be "clear," are all too frequently couched in zero-sum terms, then at one level the question becomes how to "blur" the political goals of particular terrorist organization "constituency groups" under consideration that have articulated political demands and aspirations.68 One approach may be to use what David Baldwin calls "positive sanctions," aimed at terrorist group constituencies, to make it more difficult for them to agree on the range of tactical choices to endorse for terrorist groups.69 "Positive sanctions" that establish a set of interconnections between a state (e.g., Israel, the United States) and "constituency groups" might include resources for urban renewal, education, housing, and medical supplies for Gaza and to be sure, other locales now under the aegis of a continuously evolving Palestinian nation.70

At another level, it may be in the Israeli government's interest, and in the national security interest of Israel, to continue "the peace process" if only for the sake of keeping low the number and type of terrorist groups active in the political fray.71 Compounding the challenge even more, it may be advantageous, in particular situations or with specific terrorist groups, to engage in some type of dialogue (e.g., prisoner exchange, the scope of prisoner health or visitation rights under consideration) if only to help reduce the likelihood of a solid "hardline" consensus among terrorist tacticians about terrorist group tactics.

In conclusion, inasmuch as this study ties together work on terrorism and places its own findings within the context of a theoretical framework, this study serves as a first step within the realm of terrorism studies toward what Zinnes calls the "cumulative integration" of scholarly work.72 To be sure, those findings demonstrate it is possible to move beyond the "coffee table logic" of fragmented rhetorical arguments that shape much of what is discussed about terrorism in the Middle East. Hopefully, the basic structure of this research can assist others in their work, and thus contribute to efforts to learn more about a form of political violence that remains largely untouched by empirical investigation.

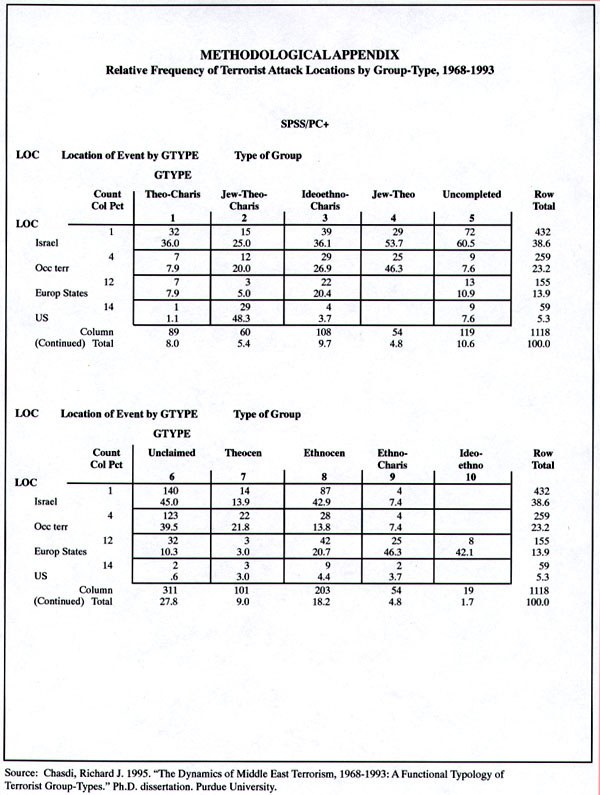

Methodological Appendix: Relative Frequency of Terrorist Attack Locations by Group-Type 1968-1993

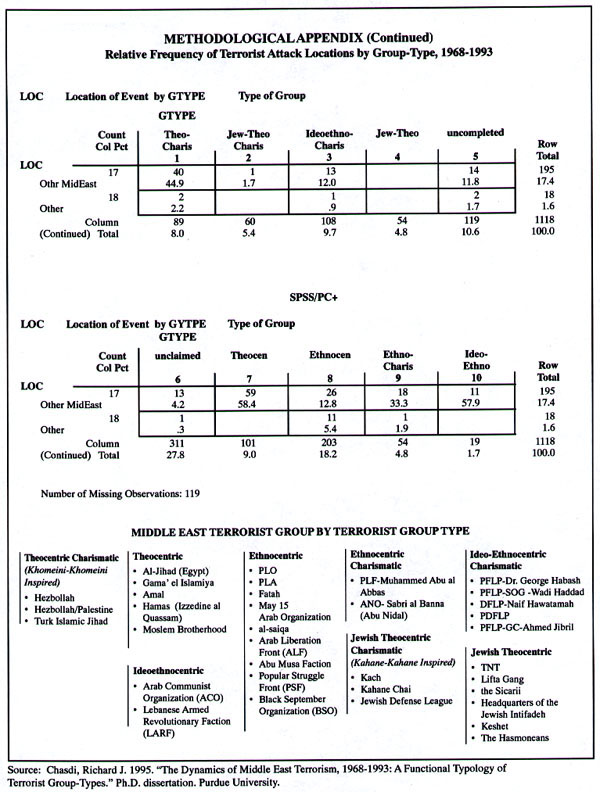

Methodological Appendix: Continued

Endnotes

First and foremost, I am indebted to my mentor and friend, Professor Michael S. Stohl, and to Professors Louis Rene Beres, Lyn Kathlene, James McCann, Robert Melson, Keith L. Shimko, and Michael A. Weinstein, all of Purdue University. I am grateful to Professor Frederic S. Pearson, Director of the Center for Peace and Conflict Studies, and Professor Ronald E. Brown, Chairperson, Department of Political Science, both of Wayne State University, for their steadfast support. Thanks are due to Penelope A. Morris, for manuscript preparation. On a personal level, many thanks to Sharon, Neal, Dick, Herb, Kenneth, and Tiffany Anne for their invaluable assistance.

1. Jorge Nef, "Some Thoughts on Contemporary Terrorism: Domestic and International

Perspectives," in John Carson, ed., Terrorism in Theory and Practice: Proceedings of a

Colloquium (Toronto: Atlantic Council of Canada, 1978), pp. 19-20, quoting Martha Crenshaw

Hutchinson.

Return to body of article

2. For example, a strong case can be made that Islamic fundamentalist terrorists attacked

commuter buses in Israel and killed over 60 Israelis during four successive attacks precisely

because terrorist group decision makers reasoned that such carnage would severely disrupt if not

destroy the "peace process." See Serge Schmemann, "Israeli Forces Seal Off Big Parts of West

Bank," The New York Times, 6 March 1996, pp. A-1, A-6; Youssef Ibrahim, "Hamas Chief Says

He Can't Curb Terrorists," The New York Times, 9 March 1996, p. A-5; and, Frederic S. Pearson

and J. Martin Rochester, International Relations: The Global Condition in the Twenty First

Century (Boston, MA: McGraw Hill, 1988), pp. 445-65; 659-62.

Return to body of article

3. Those group-types include: theocentric (Islamic fundamentalist), theocentric charismatic,

ethnocentric (secular nationalist-irredentist), ethnocentric charismatic, ideo-ethnocentric

(nationalist irredentist with Marxist-Leninist underpinnings), ideo-ethnocentric charismatic,

Jewish theocentric (Jewish fundamentalist) and Jewish theocentric charismatic.

Return to body of article

4. David E. Long, The Anatomy of Terrorism (New York: The Free Press, 1990), pp. 18-19, 211;

Amir Taheri, Holy Terror: Inside the World of Islamic Terrorism (Bethesda, MD: Adler & Adler,

1987), p. 89; and, Talcott Parsons, Max Weber: The Theory of Social and Economic

Organization (New York: The Free Press, 1964), p. 361.

Return to body of article

5. Harvey Starr and Benjamin A. Most, "Patterns of Conflict: Quantitative Analysis and the

Comparative Lessons of Third World Wars," in Robert E. Harkavy and Stephanie G. Neuman,

eds., Approaches and Case Studies, Vol. 1 of the Lessons of Recent Wars in the Third World

(Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath, 1985), pp. 33-52; Richard Chasdi, "The Dynamics of Middle East

Terrorism, 1968-1993: A Functional Typology of Terrorist Group-types," unpublished Ph.D.

dissertation, Purdue University, 1995, pp. 3-5, 100-5, 344-50. An underlying theme of that

typology is the considerable conceptual distance between ideology and goals, the latter really

amounting to tactical alternatives, such as, in the case of theocentric groups, the emergent reality

of a single Islamic state, a confederation of Islamic states, the destruction of Israel, or the

destruction of contemporary Sunni regimes.

Return to body of article

6. I use Wallerstein's phrase "world systems" to describe that conceptualization. This construct

was developed with the invaluable assistance of Michael S. Stohl and Patricia T. Morris.

Marxist-Leninist terrorist groups are considered structuralist, while Islamic fundamentalist

terrorist groups and nationalist-irredentist terrorist groups are considered to be more

"non-structuralist." Immanuel M. Wallerstein, The Modern World-System: Capitalist

Agriculture and the Origin of the European World Economy in the Sixteenth Century (New

York: Academic Press, 1974); Chasdi, "Dynamics of Middle East Terrorism," pp. 104, 314.

Return to body of article

7. Plainly, the Arab Middle East has a long-standing tradition of making distinctions between

groups based on religious affiliation. It is that practice which generates and sustains a prevailing

social ideology that highlights the importance of religion and group identification. It seems

plausible that charismatic leaders of terrorist groups with political ideologies that are antithetical

to the prevailing social ideology (Islam) might encourage their groups to act in ways more like

other Arab/Islamic terrorist groups in order to develop and nurture a set of political

interconnections. See Augustus R. Norton, "Terrorism in the Middle East," in Vittorfranco S.

Pisano, ed., Terrorist Dynamics (Arlington, VA: International Association of Chiefs of Police,

1988), pp. 13-14.

Return to body of article

8. Walter Goodman, "Rabbi Kahane says: 'I'd love to see the J.D.L. fold up. But-'," New York

Times Magazine, 21 November 1971, pp. 116, 118-19, 122; Bruce Hoffman, "The Jewish

Defense League," Terrorism, Violence, Insurgency Journal, 5, no. 1 (1984), pp. 10-15; Harold D.

Lasswell, "Terrorism and the Political Process," Terrorism: An International Journal, 1, nos. 3/4

(1978), p. 258; Ian S. Lustick, For the Land and the Lord: Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel

(New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 1988), pp. 67-71; Peter Merkl, "Approaches to the

Study of Political Violence," in Peter H. Merkl, ed., Political Violence and Terror: Motifs and

Motivations (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1986), p. 25; Robert L. Pfaltzgraff,

Jr., "Implications for American Policy," in Uri Ra'anan, Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr., Richard H.

Shultz, Ernst Halperin and Igor Lukes, eds., Hydra of Carnage: The International Linkages of

Terrorism and Other Low-Intensity Operations: The Witnesses Speak (Lexington, MA: D.C.

Heath, 1986), p. 292; Ehud Sprinzak, "From Messianic Pioneering to Vigilante Terrorism: The

Case of the Gush Emunim Underground," in David C. Rapoport, ed., Inside Terrorist

Organizations (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), pp. 194-216; Paul Wilkinson,

Terrorism and the Liberal State, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan, 1986), pp. 204-5.

Return to body of article

9. Louis Rene Beres, "Terrorism and International Law," Florida International Law Journal, 3,

no. 3 (1988), pp. 293, 299 n. 14; Louis Rene Beres, "Confronting Nuclear Terrorism," The

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review, 14, no. 1 (1990), pp. 130, 132, 133;

Noemi Gal-Or, International Cooperation to Suppress Terrorism (New York: St. Martins, 1985);

Gregory F. Intoccia "International Legal and Policy Implications of an American

Counter-Terrorist Strategy," Denver Journal of International Law and Policy, 14, no. 1 (1985),

pp. 136-39; Christopher C. Joyner, "In Search for an Anti-Terrorism Policy: Lessons from the

Reagan Era," Terrorism, 11, no. 1 (1988), p. 37; Alex P. Schmid, Political Terrorism: A

Research Guide to Concepts, Theories, Data Bases and Literature (Amsterdam: Transaction

Books, 1983), pp. 119-58; Chasdi, "Dynamics of Middle East Terrorism," p. 66; and Pearson and

Rochester, International Relations, p. 448.

Return to body of article

10. Edward F. Mickolus, Transnational Terrorism: A Chronology of Events, 1968-1979

(Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1980).

Return to body of article

11. Chasdi, "Dynamics of Middle East Terrorism," pp. 123-26.

Return to body of article

12. "8 Austrian tourists hurt in Cairo bus attack," Arab News: Saudi Arabia's First English

Language Daily, 28 December 1993, p. 4; "Egypt thwarts attack plans," Arab News: Saudi

Arabia's First English Language Daily, 1 January 1994, p. 4.

Return to body of article

13. Gabriel Weimann and Conrad Winn, The Theater of Terror: Mass Media and International

Terrorism (White Plains, NY: Longman Publishing Group, 1994), p. 71.

Return to body of article

14. Chasdi, "Dynamics of Middle East Terrorism," pp. 126-27.

Return to body of article

15. See, for example, Anthony Kellett, Bruce Beanlands, and James Deacon, Terrorism in

Canada 1960-1989 No. 1990-16 (Ottawa: Solicitor General Canada Ministry Secretariat, 1991),

p. 40.

Return to body of article

16. Wolf Blitzer, "U.S. weighing military strike to free hostages," and "Two more kidnapped in

Beirut," Jerusalem Post, 26, 27 January 1987; Dvorah Getzler, "Grenade kills protester,"

Jerusalem Post, 11 February 1983, pp. 1, 2; "Second German abducted in Beirut," Jerusalem

Post, 22 January 1987, p. 1; "Fears grow Waite now kidnap victim," Jerusalem Post, 1 February

1987, p. 1.

Return to body of article

17. Kirk W. Elifson, Richard P. Runyon, and Audrey Haber, Fundamentals of Social Statistics

(New York: Random House, 1982), pp. 161, 432-35; Marija J. Norusis, The SPSS Guide to Data

Analysis SPSS/PCt, 2nd Ed. (Chicago, IL: SPSS, 1991), pp. 229-30, 269-70, 275-76, 322, 325;

Louis G. White, Political Analysis: Technique and Practice Second Edition (Pacific Grove, CA:

Brooks/Cole Publishing, 1990), pp. 156, 350-54; Thomas H. Wonnacott and Ronald J.

Wonnacott, Introductory Statistics for Business and Economics Fourth Edition (New York: John

Wiley & Sons, 1990), pp. 43, 262, 293-95, 549-60.

Return to body of article

18. Neil C. Livingstone and David Halevy, Inside the PLO: Covert Units, Secret Funds and the

War Against Israel and the United States (New York: William Morrow, 1990), p. 18; Yonah

Alexander and Joshua Sinai, Terrorism: The PLO Connection (New York: Taylor & Francis,

1989), pp. 130-31.

Return to body of article

19. Norusis, SPSS Guide, p. 270.

Return to body of article