by Mark W. Charlton

INTRODUCTION

In their pioneering study of global food relations published 19 years ago, Raymond Hopkins and Donald Puchala noted that the obligation to prevent starvation has been a guiding principle of international food policy of long-standing importance. In particular, they contend, "there has been and remains a prevailing consensus that famine situations are extraordinary and that they should be met by extraordinary means."1 In a more recent study entitled, The International Organization of Hunger, Peter Uvin reiterates this observation by suggesting that a strong anti-starvation regime exists which is "quite universally shared" and is a "rare example of a consensual norm."2 "This norm," Uvin suggests, "causes donors to give emergency food aid and at the same time constrains them from using it for their political self-interest."3 To back this claim, Uvin cites the large American response to the Ethiopian famine in 1984-85 as an example of a state deciding to override more immediate foreign policy interests in order to support a humanitarian response to the crisis.

Since the end of the Cold War, the world's attention has been drawn increasingly to a series of dramatic humanitarian crises, especially on the African continent. As a result, there has been a significant shift in resources toward relief aid, particularly in the form of food aid. In recent years, more international emergency food aid has been delivered than ever before in human history. According to estimates, today, over 40 million people depend on emergency food aid rations supplied by the World Food Program (WFP).4 In addition, donor nations seem increasingly willing to disregard traditional national sovereignty concerns in order to facilitate humanitarian relief operations. For the first time, we have seen the international community commit military forces to the task of ensuring that food supplies are delivered to populations facing starvation in civil war conditions. As UN High Commissioner For Refugees, Sadako Ogata, has stated: "[w]e cannot permit the principles of national sovereignty to shield governments from responsibilities towards their own citizens."5 Similarly, Thomas Weiss and Larry Minear have argued, "An important conceptual change is taking place. The continued evolution of the definition of sovereignty over the next decade could well result in a 'use-it responsibly' or 'lose-it approach'."6

At the same time as a call for a new ethic of humanitarian intervention is being issued, there appears to be a move toward a greater institutionalization of emergency food aid giving. Donor agencies have been grappling with how to secure more stable funding for humanitarian emergencies and develop greater professionalism in the relief process. New concepts, such as the need to link relief with development, have been injected into policy debates with the stated hope of improving the quality of emergency food relief programs. These trends suggest that, in this post-Cold War era, the anti-starvation regime which Uvin refers to is being strengthened significantly. The move to institutionalize and professionalize international emergency assistance seems to be a clear demonstration of the willingness of Western states to override political and economic interests in order to further the creation of a new international humanitarian order.

However, such an interpretation of recent developments may be misleading. Rather than being a harbinger of a new and more humane international order, this article will argue that the recent shifts in the global food aid regime represent a coping strategy of Western donors in response to the development failures of the 1980s and to the shift of international interest away from the poorest regions of the world such as Africa. According to this interpretation, the strengthening of the emergency food aid component of the global food regime represents an attempt to construct a "safety-net" in order to cope with the growing number of humanitarian crises occurring in the South. Instead of being used an instrument of development as portrayed in the 1980s, the global food regime could increasingly become the principal tool by which the North attempts to manage the mounting crisis facing marginalized regions of the Third World, while containing these crises within acceptable humanitarian boundaries.

THE EMERGENCE OF A DEVELOPMENT ORIENTED FOOD AID REGIME

In order to develop the thesis of this article, it is useful to first examine the evolution of international food aid policy in the 1970s and 1980s, and the emergence of a more development oriented food aid regime. In its early years food aid was seen largely as a surplus disposal mechanism that could serve a variety of economic and foreign policy purposes. Food aid transfers were treated with suspicion by many development officials and were poorly integrated into development assistance programs. Decision-making tended to be ad hoc, focusing on short-term goals with little regard to the wider developmental impact of the food aid allocations.

However, international food aid policy began to undergo a significant transformation beginning in the early 1970s. The key watershed in this development was the World Food Conference in Rome in 1974. Resolutions passed at this conference articulated a general set of policy principles that have since been elaborated upon by the Committee on Food Aid Policies and Programme (CFA) and institutionalized in donor aid policies. According to the consensus that emerged within the food aid policy community, food aid should no longer be seen as a surplus disposal mechanism used primarily for immediate consumption, but be programmed to achieve longer term results. Food aid was to be conceptualized as a development resource, which could be linked to such goals as improvement in agricultural production, enhancement of food security, and facilitation of broader development objectives. Among the principles promoted have been the multi-year programming of food aid, greater use of triangular food aid transactions, increased use of multilateral channels for food aid, more objective criteria for allocating bilateral food aid, and more emphasis on evaluations as a basis for programming additional quantities of food aid.7

The emergence of a development oriented food aid regime helped to move food aid into the "mainstream" of the development assistance and hence gain greater respectability as a resource transfer. Agencies like the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) established food aid units in order to promote more rigorous and professional attention to food aid policy issues.8 Policy discussions with the CFA, the main multilateral forum for food aid policy discussions, increasingly focused on identifying ways in which food aid could be integrated into a greater variety of development projects. By the end of the 1980s, the absorption of food aid into the development mainstream could be seen by the extent to which concern with the linkage of food aid with structural adjustment had entered policy debates. It is also reflected in the number of reforms carried out within the World Food Program, the United Nations pre-eminent food aid agency, designed to transform the agency into a full-fledged "development agency." As the focus on linking food aid development grew, the WFP sought new roles for itself, in some cases chairing donor aid consortium for some countries and seeking ways to identify new ways of linking food aid to policy dialogues on structural adjustment programs. At the same time, the WFP forged new relations with agencies like the World Bank who have traditionally been skeptical of the development benefits of food aid. In turn, donors increasingly turned to the WFP as a channel for their food aid allocations. By the 1980s, the WFP was handling 25 percent of all food aid shipments, making it the second largest source of development assistance within the UN, after the World Bank.9

Inherent in this shift in focus toward developmental food aid is a distinct bias against emergency food aid, particularly when it is used to feed people directly. Raymond Hopkins has summed up this line of thinking in the following words:

[G]iven that the resources for food aid projects are limited, then the aid must be efficiently used for development ends and not expended for consumption uses, since the latter may even reduce pressure on governments to address rural development and long-term security goals.10

Hopkins goes on to explain why the notion of "delivering food directly to the hungry" is a "suspect principle, except in the most serious emergency situations." Transportation costs are extraordinarily high, direct distribution "reinforce(s) excessively expensive subsidy programs,"11 and direct feeding can cause administrative nightmares leading to corruption and diversion of food supplies.

Not surprisingly, as the development orientation of the food aid regime was strengthened, an increasingly sharp distinction was drawn between emergency food aid and longer term development aid. The principle aim was to move the majority of food aid giving toward the achievement of long-term improvements in the economic development and food security of the recipient country with an emphasis on detailed and lengthy processes of appraisal and approval. Emergency food was increasingly seen as a residual component of the food aid regime which would be allocated only in the most pressing of cases.

THE CHANGING PATTERN OF FOOD AID FLOWS

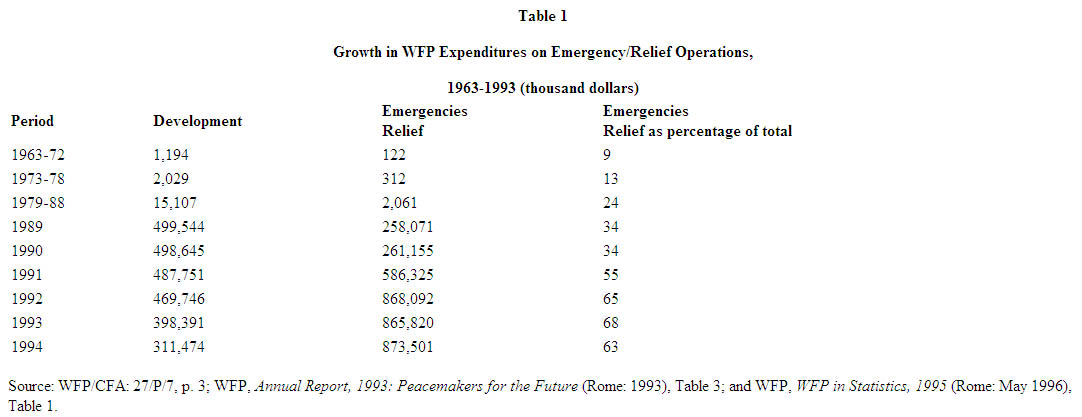

Despite the rise in emphasis on development food aid in the 1980s, food aid flows in the 1990s have shown a significant shift in the direction of greater quantities of emergency food aid. This can be seen clearly in the changing character of aid flows within the WFP itself. Since its creation, emergency food aid has accounted for only a small portion of the WFP's total programming. During the 1960s, emergency food aid accounted for less than 10 percent of total WFP expenditures. In the 1970s, the Sahelian drought bumped up the share of emergency food aid, but it still remained less than 15 percent of total WFP expenditures. In the 1980s, this gradually increased with the impact of serious food crises in several African countries, pushing the emergency food aid component to one-quarter of the WFP's work, and by 1990 to one-third. However, the most dramatic shift has taken place in the 1990s, when the emergency food aid component of WFP expenditures mushroomed from 34 percent in 1990 to a high of 68 percent in 1993. (See Table 1)

The changing character of aid flows within the WFP has shown a dramatic jump in the sheer magnitude of emergency food aid operations. The WFP has regularly approved over 50 emergency food aid operations a year beginning in 1978. Although there has actually been a slight decline in the total number of operations, the total value of these operations has risen dramatically to a high of $896.8 million in 1992, a figure nearly four times larger than that reached even during the African food crises of 1984-85.12 This figure reflects not only the growing size of emergency food needs, but also the greater reliance of donors on the WFP for channelling these funds.

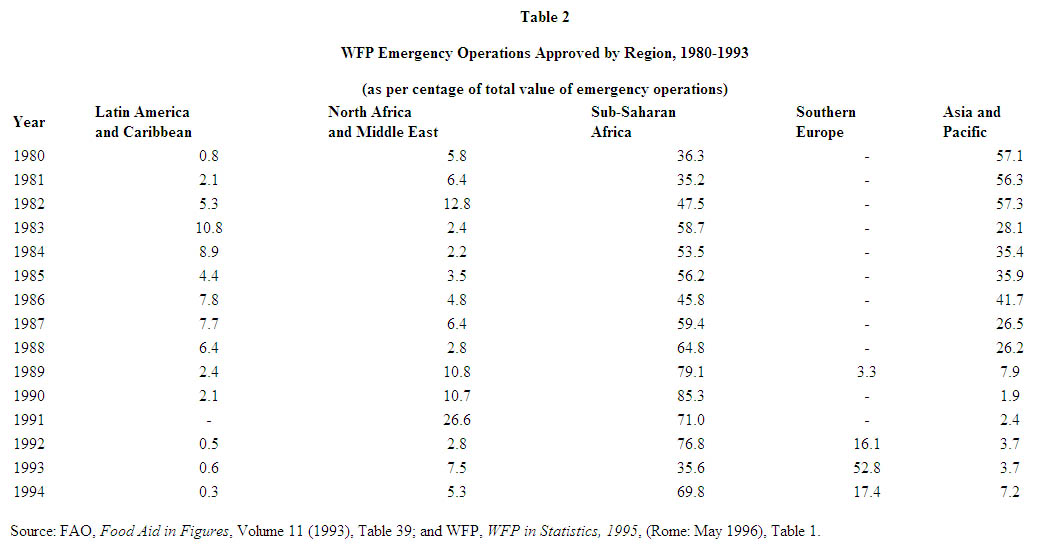

As Table 2 shows, another recent trend has been a shift in the regional focus of emergency food aid. In previous decades, emergency food aid was transferred in large volumes to both Asia and Africa, with the Asian region often taking the larger share. Since 1989, Africa has become the largest focus of emergency food aid allocations. This is in part due to the success of some Asian countries in developing better food security systems, but is also a reflection of the growing number of complex emergencies centred on the African continent. More recently, Southern Europe has emerged as a major recipient of WFP emergency food aid.

TABLE 1: Growth in WFP Expenditures on Emergency/Relief Operations, 1963-1993 (thousand dollars)

TABLE 2: WFP Emergency Operations Approved by Region, 1980-1993 (as per centage of total value of emergency operations)

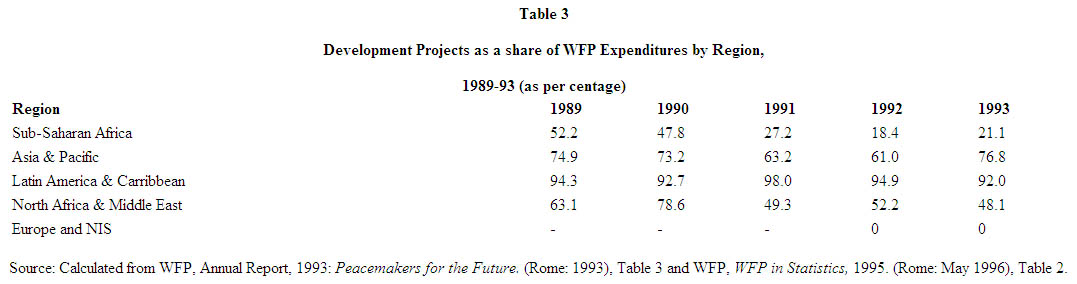

As the regional focus of emergency food aid has shifted in recent years, so too has the balance between emergency food aid and development food aid shifted within regions. As Table 3 shows, development food aid is the predominant form that allocations to Asia, Latin America, and North Africa now take. However, in Africa, development food aid makes up an increasingly small share of the total food aid allocations to the region.

TABLE 3: Development Projects as a share of WFP Expenditures by Region, 1989-93 (as per centage)

As significant as these changes in food aid flows are, they do not tell the whole story. What is equally important is the changing nature of the food emergencies themselves. Since the 1960s, the WFP has defined emergencies as "urgent situations in which there is a clear evidence that an event has occurred which causes human suffering or loss of livestock and which the government concerned has not the means to remedy; and it is demonstrably abnormal even which produces dislocation in the life of a community on an exceptional scale."13 This more traditional notion of food emergency placed the emphasis on food emergencies as abnormal, largely unforeseen events, usually caused by some act of nature.

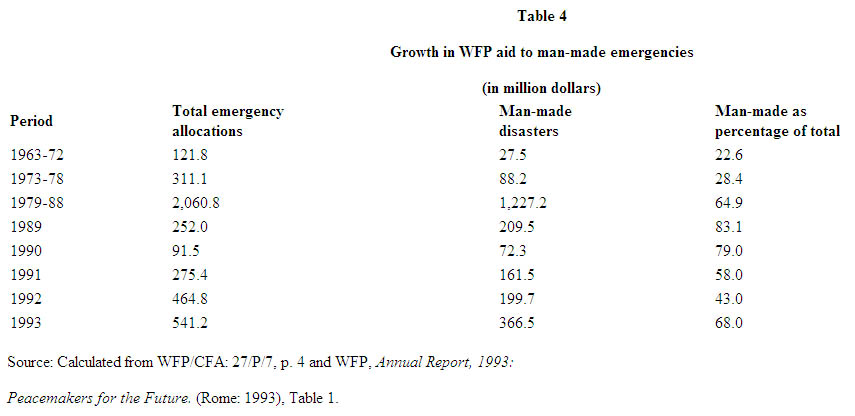

However, more recently, the WFP has adopted a more varied definition of emergencies, distinguishing between sudden natural calamities, man-made disasters and crises resulting from crop failure or drought conditions. This classification draws a distinction between those emergencies that arise from sudden natural calamities or drought conditions and those that are caused by political and social disruption.

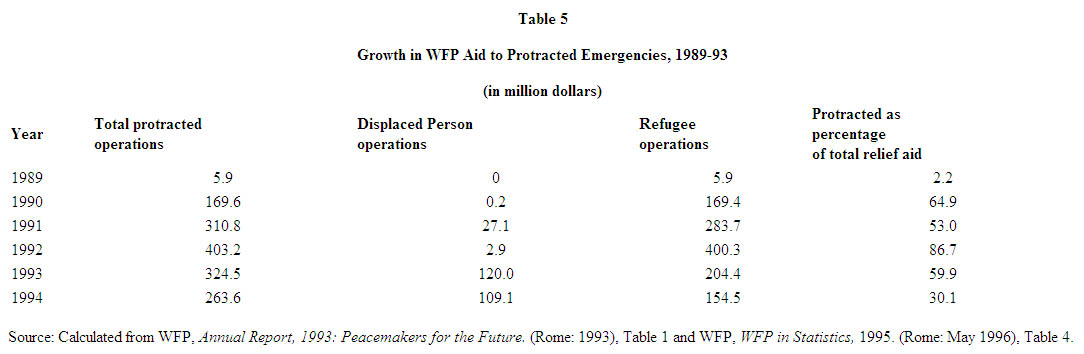

In the 1980s, the WFP became increasingly aware that what began as emergency operations in response to sudden refugee movements, were becoming in fact ongoing, long-term programs. Thus it began to draw a distinction between emergency relief operations that were intended to be of a more limited duration and protracted relief operations aimed at feeding refugees and displaced persons on an ongoing basis. As Tables 5 and 6 suggest, man-made emergencies and protracted relief operations have emerged as the two dominant types of situations in which WFP relief aid is allocated.

TABLE 4: Growth in WFP aid to man-made emergencies (in million dollars)

TABLE 5: Growth in WFP Aid to Protracted Emergencies, 1989-93 (in million dollars)

These recent dramatic shifts in the pattern of food aid flows pose a number of significant challenges to the development food aid regime. Aid agencies, both governmental and NGO, are keenly aware that it is much easier to raise money for relief operations than it is for development aid. At a time when governments of most donor countries are cutting back on the amount of development funding, emergency relief assistance remains a high profile and popular part of the aid budget. Thus as aid budgets are trimmed, it is often easier to protect the relief portion of the budget than the more mundane development portion. As a result, there has been both a quantitative shift as aid budgets are slashed, and also a qualitative shift as emergency relief assistance crowds out development spending. For example, Andrew Natsios notes that in 1992 the US government spent more on humanitarian relief ($824 m) than on development projects ($800m) for the whole African continent.14

Similarly, within the food aid system itself, we can see a shift away from development oriented spending. Already in the 1980s Edward Clay and Olav Stokke noted a growing tendency for substitution between emergency and program food aid. Donors tended to determine their total budget based on a number of institutional factors.15 As the need for emergency food aid rose, the donor would simply shift its spending from program to emergency food aid, without adjusting its total food aid figures to any great extent. In the 1990s, as the World Food Program has become involved in a growing number of complex emergencies and protracted relief operations, it has been forced to curtail some of its development projects. In 1991, 1992 and 1993, the total amount spent on development food aid projects declined each year from the previous year, representing a total decline in actual dollars of 20 percent.16 During the 1980s, when the concept of development food aid was gaining popularity, the tendency was to think of emergency food aid as essentially a residual category of spending. Now, as the demand for emergency food aid grows, an inversion appears to be taking place in which there is growing competition between emergency and program food aid, with the later now becoming the residual category.

Second, there is a concern that the shift toward emergency food aid will undermine some of the key norms of a development oriented food aid regime. As Clay and Stokke sum up their concerns:

If developmental programme food aid has, in effect, become a residual category, this would appear to restrict the potential for a positive development impact. It would limit the scope for multi-annual programming, linking monetised resources to particular development activities as envisaged in most proposals for food aid reform during the past decade. At worst, there is a danger that some bilateral food aid programmes have been recognized as all too useful as ministerial slush funds for responding publicly to disasters the world over.17

Third, there is a growing recognition that relief aid itself has ambiguous results that may in fact undermine a country's capacity to deal with future crises. Evidence gathered from the evaluations of past relief operations note that the large influx of emergency food aid can undermine the capacity of indigenous institutions to cope with future crises and increase the dependency of local populations.18

Fourth, it is becoming evident that the aid policies that donors have pursued during the past decade have themselves directly contributed to the vulnerability of many countries to food emergencies. The tendency of donors to increase the conditionality of its development assistance tying it to performance on a variety of issues such as structural adjustment, good governance, and human rights has made a number of countries either ineligible for development assistance or led to a significant curtailment of their funding levels.19 Yet, when these countries lapse into a humanitarian crisis, tremendous pressure to respond is placed on donor governments by the media, NGO lobbies and the public. Thus donors who, for the sake of budget austerity measures or conditionality restrictions, have halted a development program in a country, now find themselves involved in the same country in a large relief operation which may in fact consume much larger sums of resources than their former development assistance programs ever did. Relief operations are a grossly inefficient means of improving the welfare of populations. The cost of relief operations is extremely high, with most of the resources being spent on salaries, materials and transportation costs.

THE SEARCH FOR A NEW POLICY PARADIGM

It is clear from the above discussion that the context in which food aid is being allocated has undergone a significant change in recent years. In the face of these challenges, it is perhaps not surprising that the development community has begun searching for a new policy paradigm for allocating relief aid. As a result, there has been growing interest in understanding the relationship between relief and development assistance. As Boutros Boutros-Ghali has stated: "Food for humanitarian assistance must over time become food for development, and thus must be followed by self-sustaining food production in times of peace. Understanding the continuum between emergencies and development, and acting on that understanding is one of the most challenging intellectual and physical projects of our time."20

A number of labels have been attached to the new paradigm: relief-to-development continuum, relief-development strategies, or linking relief and development (often referred to in the literature simply as LRD). In a sense the argument is a starkly simple one. Historically, donors have drawn a clear distinction between relief and development aid. This has created distinctive bureaucratic structures, lines of communication, and organizational cultures, which at times work at cross purposes with one another and at other times cause unnecessary confusion and duplication in the aid process. The argument made by supporters of the concept of linking relief and development is "that the sharp division between development and relief is becoming unsustainable" and that new ways of linking relief and development must be found.21 Consequently, relief operations should take into account the development implications. In turn, development assistance should give greater attention to measures that enhance famine prevention.

In recent discussions of linking relief and development, a number of suggestions have been put forward for improving the development impact of emergency food aid, such as giving local governments and institutions greater responsibility for food distribution and monitoring; using relief food as wages to pay for development work rather than directly feeding people; employing food for work projects to build roads, plant trees, improve irrigation facilities, or carry out soil conservation projects; and selling relief food through the marketing system to stabilize prices and generate cash to pay for public works.22

Mark Duffield, in examining the concept and the vigor with which it has been promoted by such agencies as the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), suggests that the relief-development debate "is primarily an argument over resources, a defensive move by an institutional interest (the UNDP) which fears for the object of its existence: stable societies that can sustain socioeconomic improvement."23 Duffield's comments appear to be relevant, not just to the UNDP, but to the broader food aid system itself, where the concept of the relief-development continuum is an attractive one for a number of reasons. The concept of LRD helps define a role for development agencies in the growing number of emergency operations. It helps to maintain a "development" focus within the food aid regime, even as larger volumes are shifted to emergency purposes. And, it helps harried aid officials at home to convince cost conscious politicians that the high cost of current relief operations are a worthwhile "investment" which will pay dividends in the future.

Despite the growing appeal in donor circles, the concept of linking relief and development has a number of serious drawbacks, particularly when viewed in the context of an agency like the WFP. Although the WFP has adopted its own relief-development strategy, Wolfgang Herbinger, an official with the agency, notes that there are serious constraints on implementing the idea. Most donors still provide emergency resources to the WFP primarily on an ad hoc basis, usually tied to a specific operation. Thus, the WFP is limited in its ability to program on a longer term basis for activities that link relief and development. Furthermore, in many operations, particularly those involving protracted refugee/displaced persons, donors have made available barely enough resources to meet the basic food needs of the affected people.24

James Ingram, a former Executive Director of the WFP, is even more skeptical that the concept will work in practice. Humanitarian crises require quick, timely responses which are carried out with almost military precision. By incorporating the relief-development concept into UN resolutions that call for an early involvement of UN development agencies in emergency situations, Ingram fears that response to the crisis will be bogged down. As he notes: "While theoretically sound, this is a case of the best being the enemy of the good. When development agencies become involved in an emergency, development is not promoted, but emergency interventions are impeded. The more actors involved, the more difficult and drawn out the coordination task becomes."25

But, a broader question is whether the concept of a relief-development continuum is at all relevant to the type of emergencies that aid donors increasingly face today. In discussing this question, it is useful to examine the distinction that Margaret Buchanan-Smith and Simon Maxwell have drawn between four different types of emergencies:26

1. Rapid onset emergencies: These are triggered by natural disasters, such as floods or earthquakes. The crisis is usually temporary in nature. A typical situation would be the cyclone that caused extensive flooding in Bangladesh in 1991.2. Slow onset emergencies: These are triggered by natural disasters such as a drought or pest attack. While the emergency may be slower in developing, once recognized and addressed, the crisis may still have a limited life span. In recent years, Southern Africa, especially Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe have experienced such crises.

3. Permanent emergencies: These result from more deeply embedded structural problems within the economy which generate widespread poverty and malnutrition. The ability of the government to cope with such situations is frequently exacerbated by recurring droughts or natural disasters.

4. Complex political emergencies: These are associated with long-term political and economic dislocation in a country, often associated with internal warfare and a breakdown of the country's political, economic, and social infrastructure.

The first two types of emergencies are perhaps the most manageable within the present framework of food aid policy. They are closest to the traditional concept of food crises as being the result of unforeseen natural factors. Responses to these types of emergencies are more amenable to technical improvements in the food aid system, such as better early warning systems, improved logistics and transportation arrangements, and better coordination among the various actors in the relief system. It is in these types of emergencies that the concept of linking relief to development appears to be most relevant. The third type, permanent emergencies, is the kind of situation that donors have sought to avoid by linking development food aid with projects and policy discussions aimed at encouraging agricultural policy reform and enhancement of food security as a domestic policy priority. It is precisely this type of emergency that the principles of the development food aid regime were intended to address. However, the fourth type, complex emergencies, are the most difficult for the international community to cope with.

THE NATURE OF COMPLEX POLITICAL EMERGENCIES

However, complex political emergencies pose a set of distinctive problems which cannot easily be incorporated into the existing food aid regime. What makes complex emergencies unusual is their distinctively political nature. In past discussions of famines, the political dimension was seen as somewhat derivative in nature, the danger of a coup or civil unrest, for example, if a government failed to respond quickly enough to a famine situation produced by a drought. In contrast, complex emergencies themselves are inherently political in nature. As Mark Duffield notes, "they are protracted political crises resulting from sectarian or predatory indigenous responses to socioeconomic stress and marginalization."27 Although the concept has been applied to cases such a Bosnia-Herzegovina, Georgia and Tajikstan, it is perhaps not surprising that the term was first applied to Africa. As Tim Shaw and John Inegbedion note, "Africa is now without question the most marginal of the southern continents in terms of economic, military, technological, and skilled labour resources."28 This marginalization has been increasingly evident in the extent to which "weak states, alienated populations, informal exchanges, refugee exoduses, and domestic destabilization" have come to characterize the continent.29 Shaw and Inegbedion note that because it is "plagued by debt, devaluation, deregulation, desubsidization," it is not surprising that new forms of class, ethnic, religious, and national conflict have arisen in Africa and that increased numbers of people are turning to unconventional forms of combat such as guerrilla warfare.30

Complex emergencies then have a number of distinctive characteristics that set them apart from traditional notions of natural disasters. First, they are associated with broad systemic breakdown of the economic, social and political infrastructure of a country. Collapse of the macro-economic system is reflected in dramatic declines in family income and the gross national product, hyper-inflation, and depression levels of unemployment. The collapse of markets contributes to a sharp increase in food insecurity, which is reflected by higher levels of severe malnutrition and starvation.

Second, the society is torn increasingly by political strife which is rooted in identity conflicts. As Joanna Macrea and Anthony B. Zwi note, the aim is generally not just military defeat but to "disempower the opposition, to deny it an identity and to undermine its ability to maintain political and economic integrity."31 Such conflicts tend to be expressed in unconventional forms of combat. As the United Nations Secretary-General notes: "They are usually fought not only by regular armies but also by militias and armed civilians with little discipline and with ill-defined chains of command. They are often guerrilla wars without clear front lines. Civilians are the main victims and often the main targets."32 The resources and the physical means of production of society come under attack because of their vital importance to the survival of communities and their way of life.33 As a result, a deliberate strategy of the combatants often is to disrupt food production and distribution by destroying food crops, attacking farmers in their fields, targeting markets, and looting food reserves. Ellen Messer estimates that in 1993, 29 countries experienced acute food shortages "as a result of armed conflict which purposefully used hunger as a weapon in active hostilities."34 The majority of these cases occurred in Africa and Eurasia.

Third, in such conflicts relief operations take on increased political significance as both sides try to exploit relief supplies for political and strategic purposes. Food convoys may be attacked and destroyed to demonstrate control over a region and prevent valuable assets from falling into the hands of the perceived enemy. More important, however, the attacks on food supplies can become a significant part of the war economy, as the economic interests of powerful groups within a society, like merchants, allied with political and military elites, can reap substantial profits from scarcity. Or, food supplies may be looted and sold or traded in order to acquire money and arms to continue the campaign. In these crises traditional distinctions between combatants and non-combatants break down and international laws regarding distribution of relief supplies in conflict situations are wantonly disregarded.

Finally, unlike many civil wars in the past where a dissident region may be seeking to break away from a strong central government (e.g., Nigeria and the Biafran civil war), complex emergencies frequently involve the collapse of state institutions, which leads to a total paralysis of political and judicial institutions and contributes to an expansion of the general chaos and banditry within the country. As Boutros-Ghali notes, "Not only are the functions of government suspended, its assets are destroyed or looted and experienced officials are killed or flee the country."35 The resulting chaos and disorder provide a catalyst for massive population movements of internally displaced people and refugees. In some cases, such as Afghanistan, Liberia, and Somalia, any form of national government has virtually ceased to exist, while in others, such a Zaire, central authorities exercise little control or influence outside the capital city.

In countries experiencing complex emergencies, where a protracted civil conflict is continuing, it seems highly unrealistic to expect that relief operations will be successful in moving these countries back to a path of development when the political and social administration has collapsed and there is no longer a functioning transportation system or economy. In many of these cases donors have already withdrawn other forms of development assistance, making a gradual shift from relief to rehabilitation to development phases virtually impossible. In situations where domestic conflict is ongoing, famine mitigation measures, such as building local grain reserves, are likely to create only new targets for competing forces. In such a context, the notion of linking relief and development has an air of unreality to it. As Duffield notes, if a country was not able to achieve sustainable development prior to the present crisis, "it is questionable if it is possible now given the loss of these advantages."36

SECURING STABLE RESOURCES

As mentioned earlier, a major issue posed by the shift in emphasis toward larger amounts of emergency aid is the growing threat that this poses to development resources. This has led to a renewed search for a more stable basis for funding emergency food aid operations.

During the past decade and a half food aid reformists have been able to convince donors to plan their developmental food aid on a longer term basis. As a result, donors have been increasingly willing to enter into multi-year food aid agreements with bilateral recipients. Donors have also channelled an increasingly larger share of their food aid through the World Food Program, which operates on the basis of two year pledges from donors. Thus, in terms of development oriented food aid, there has been both a greater stability and certainty in funding levels and a greater commitment toward multilateralism. Analysts have lauded these trends as evidence that the global food aid regime has become less driven by short-term political and economic interests.37

However, the situation for emergency food aid remains quite different. The principal multilateral channel for emergency food aid is the International Emergency Food Reserve (IEFR), which was created in 1975 and is operated by the WFP. The concept of the IEFR is a simple one: "developed and developing countries in the position to do so should earmark stocks and/or funds to be placed at the disposal of the World Food Programme as an emergency reserve to strengthen the capacity of the Programme to deal with crisis situations in developing countries."38 The IEFR is not an actual physical reserve of food stocks held by the WFP. Instead, it is a stand-by facility, or contingency fund, whereby participating governments make available food grains from their national stocks, or provide funds that are then called upon for use as the need arose.

Since its inception, donors have regularly pledged more than the 500,000 tons target set by the CFA, the governing body of the WFP. Nevertheless, serious problems have impaired the functioning of the reserve. As the demand for emergency food aid has grown, the uncertainty surrounding the availability of sufficient food resources has become a critical problem, largely because of the reluctance of donors to make advanced commitments to the reserve. For donors, the setting aside of funds for international food emergencies is not a priority issue. Emergencies, it is argued, are by definition unpredictable. By setting aside funds too early, it may create an incentive to use these funds for essentially non-emergency situations. Besides, without a visible need for these funds, it is difficult to convince domestic funding agencies that these funds are really needed, or that other priorities should be set aside in order to meet an unforeseen need.

The hesitancy of donors to come forward with advance pledges to the IEFR has caused considerable uncertainty for the WFP from a planning point of view. As more of the emergencies being dealt with have been of a protracted nature, it is necessary to plan these operations on a longer term basis. In order to address this problem the Director General of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) proposed a legally binding convention, of possibly three years, which would commit donors to providing a certain minimum level of emergency food aid during the length of the convention. However, the major donor countries rejected this idea, preferring instead annual pledges to the IEFR, with donors having the option to make two year pledges if they so wish.

A related problem that has continued to plague the WFP over the years has been the lack of adequate cash resources to cover the costs of all of its emergency operations. When the IEFR was established, provision was made for donors to make both cash and commodity donations based on a ration of 30 percent in cash and 70 percent in commodities. It was assumed that the cash component of the pledges would be used to cover costs associated with transportation, storage and handling. From the beginning expectations regarding cash contributions have fallen short of realization. Food exporting countries, who are the major donors to the WFP, have interpreted the 30 percent ration of cash to commodities as a global figure, and have insisted that non-food exporting countries donate a greater share of the cash, while they contribute primarily food commodities. As a result, the WFP generally has received less than 25 percent of its resources in cash. At the same time, the WFP has had little latitude of its own to increase its cash resources, since WFP regulations limit its ability to sell the food commodities donated to it in order to raise cash to cover the cost of emergency operations. Thus, in cases where there has been insufficient cash available, the WFP has had to use some of its own resources to meet the needs or drawn on the next year's commitment made by donors.

To address this problem, the WFP Executive Director, in 1991, proposed a voluntary $50 million cash fund.39 However, donor countries balked at supporting such a plan. As an interim measure, the WFP established an Immediate Response Account (IRA), to which donors could make a voluntary donation of cash. This fund could be drawn on by the WFP to meet immediate cash needs posed by rapidly developing emergency situations. However, in the first year only 79 percent of the target was met.40 In 1993, donors pledged just over $12 million to the IRA, far below the Executive Director's original hopes for a $50 million fund. As a result, the WFP has had to rely on funds raised by consolidated appeals issued by the UN Secretary-General and the Director General of the FAO, particularly in cases of large-scale relief operations. Since donors respond to such appeals on an ad hoc, voluntary basis, they are able to maintain maximum bilateral control over their multilateral contributions.41

The issue of resource mobilization is complicated by the problem of "directed" pledges which threatens to undermine the multilateral character of the IEFR. Because the IEFR operates on a stand-by basis, the WFP must inform donors when it wishes to draw on its food pledges in response to a specific emergency operation. The WFP informs the donor of its commodity needs and calls upon the donor to confirm whether the specific commodities are available for shipment to the country requested. Some donors have used this procedure to insist that their food commodities be used for only specified emergencies. The United States has been the most persistent in this practice, insisting that it will commit resources to the WFP only for emergency operations that it has already approved. During the 1984-85 African food crisis, 60 percent of the shipments under WFP auspices were earmarked by donors for specific countries.42 In more recent years, as much as 80 percent of WFP's emergency resources have been earmarked by donors in this way.43 In some cases, the donor may have already made a bilateral promise to provide assistance to a particular government and wished to "direct" its pledge to meet this bilateral commitment. In other cases, the donor may wish to ensure that its food commodities are not being used in a country that it does not want to assist. In these cases, the donor may not so much refuse directly the request of the WFP, as to indicate that the requested commodities are not immediately available for shipment. In order to meet the need, WFP officials must then approach other donor agencies who are willing to forward food to the country in question.

In 1991, the Assistant Executive Director of the WFP complained to the CFA that the "multilateral character of the IEFR has been eroded over the years and that it was too slow a mechanism to respond efficiently to emergencies." He further noted: "Many contributions were late and often represented bilateral responses recorded post factum as IEFR pledges. Clearance for use of emergency resources pledged was sometimes badly delayed and so were actual procurement and shipment, forcing WFP to seek unsatisfactory ad hoc solutions."44 To the WFP and many members of the CFA, the practice of "directed pledges" appears to be a direct assault on the multilateral principle of the IEFR.

While WFP officials acknowledge that, for the most part, the directed pledges were targeted toward priority countries, the practice does potentially undermine the WFP's flexibility in switching the destination of commodities in rapidly changing emergency situations. Although the WFP Secretariat has raised the issue before the CFA on several occasions, there is little that it can do to curtail the practice, given the voluntary nature of the IEFR. In many cases there may be strong political reasons why a donor wants to be seen "directing" its assistance to a particular recipient. To insist too strongly that the practice of earmarking pledges be ended, could result in donors simply switching their assistance from "directed" multilateral to purely bilateral contributions. In many cases it is true that the WFP has been able to eventually find the commodities from other sources. Thus, despite the unwillingness of the USA to supply the food, food aid has been provided to such countries as Cuba. However, such procedures do complicate the administrative work of the WFP and does slow down the speed with which the WFP can respond to some situations. Moreover, it is clear that donors can override WFP programs by simply refusing to come forward. This was the case in May 1995 when the WFP announced that it was cutting its emergency food aid rations to Iraq in half because of the lack of a donor response to its appeal for additional funds for the Iraqi operation.45

Analysts who have written positive evaluations of the evolution of food aid policy in the 1980s have generally lauded the growing multilateralism of food aid giving and the seeming demise of foreign policy considerations and economic self-interest as primary motivating factors for a development oriented food aid regime. However, in the post-Cold War period, with its increasing preoccupation with complex political emergencies, donors appear to be more insistent on keeping tight bilateral control over their "multilateral" donations, leading to an increased politicization of emergency food aid giving. Thus, while the international community may be reluctant to provide humanitarian food aid to Iraq, in 1994 it provided the Russian Federation with more than 1.2 million tons of food aid making it the second largest recipient of food aid after Bangladesh and accounting for 8.8 percent of the total world food aid.46

NEW ACTORS, NEW ROLES

Although donors have been insistent on maintaining the essentially bilateral character of the emergency food aid system, they have nevertheless been more than willing the explore the use of alternative channels for the distribution of their emergency resources. This is in part reflected in the growing usage of the WFP as a channel for emergency food shipments. Accompanying this shift has been the assignment of new tasks to the WFP. For example, it has been called upon increasingly to monitor the impact of embargoes against countries like Iraq and respond when necessary with humanitarian aid to offset the damages.

Even more significant has been the changing role of NGOs in the emergency food aid system. Although NGOs have always played some role in emergency relief operations, historically they have played a relatively small role within the global food aid system. This role began to change dramatically in the 1980s, when a number of donor governments decided to channel a larger share of their emergency resources through NGOs. This became especially evident during the 1984-85 African food crisis. Canada, for example, channelled about two-thirds of its emergency food aid to Ethiopia through NGOs.47 By 1994, about 20 percent of global food aid transfers were made through NGO channels.

Donors turned increasingly to NGOs for a number of reasons. NGOs provide a greater degree of direct accountability to donor governments, particularly in cases where donor distrust of recipient governments is high. In addition, NGOs have been perceived as more neutral in conflict situations and provide a way of quietly circumventing traditional reluctance to violate the sovereignty of a nation. Thus in the 1980s, NGOs began taking on a special role in undertaking unorthodox tasks such as the cross border operations into the Tigre and Eritrea regions of Ethiopia. Also, because NGOs have local staff on the ground in areas where donors and multilateral agencies may not, they have provided an important complement to early warning systems, by providing independent, on-site assessments in rapidly changing situations. In cases where civil authority has disintegrated or completely collapsed and the international donor community has largely withdrawn, NGOs often are the only remaining viable organizations functioning on the ground in emergency situations.

As NGOs have come to play a larger role in emergency food aid operations, there appears to be a move afoot to formalize their role. This is reflected in the recent decision of the WFP to establish more formal contractual relations with NGOs. Other UN aid agencies like the UNHRC have had contractual relations with NGOs for some time, but the WFP has not. However, in January 1995, the WFP signed its first formal agreement with an NGO, the Catholic Relief Services (CRS). In effect, the agreement attempts to define a clear division of roles in the food aid distribution process. Under the agreement the WFP will take the lead responsibility for mobilizing all food commodities and the resources to deliver them, and arrange all of the logistics of transporting the food to agreed delivery points. For its part, the CRS will play the lead role in the final distribution and monitoring of food commodities beyond the agreed "hand over" points. Other NGOs, such as World Vision, CARE, and the Adventist Development and Relief Agency, are seeking similar agreements with the WFP.48

The growing role of NGOs has been greeted by some analysts as a positive development in the global food aid system. Ellen Messer of the World Hunger Program at Brown University notes: "NGOs have proved to be especially critical for reaching those who are outside the jurisdiction or interests of governments, or who actually are the targets of government attack."

NGOs also serve as the 'conscience' of the world community concerned with hunger, by publicizing the plight of the hungry, particularly deprived peoples who may be discriminated against because of their geographic location, religious, ethnic, tribal, or political identity, and by appealing for timely aid.49

Further, Messer notes "NGOs, in conjunction with IGOs, have also been active in rationalizing the ways humanitarian aid must be rendered, to keep it non-political, and to make aid-giving in conflict zones less ad hoc, and more predictable, effective, and efficient."50

However, not everyone shares this optimistic assessment of the growing role of NGOs in humanitarian crises. NGOs often have their own agendas and priorities which conflict with other actors in the relief system. Humanitarian crises can provide an important boon to fundraising activities. NGOs, in alliance with the international media, may provide a distorted picture of the need for outside assistance. At various times in the same country, NGOs have been criticized for exaggerating needs in order to increase contributions and downplaying needs in order to demonstrate that they are in control of the situation.51 Rather than being the "conscience of the world community," NGOs have at times been accused of muting their criticism of human rights abuses in order to avoid sanctions from the host government. This may be especially true of agencies who have longstanding development programs in the host country and fear that their projects may be shut down if they are seen to be too forthcoming with negative information.52

Some analysts have suggested that the mobilization of large-scale external relief efforts, with its onslaught of foreign donor agencies, may actually undermine local efforts at maintaining indigenous coping capacity. NGOs often set up parallel structures and attract away experienced indigenous personnel by providing better salaries. Maxwell and Lirenso suggest that it was because of such negative experiences with NGOs in past emergency situations that the Ethiopian government decided to greatly downplay the role of NGOs in its new food security strategy.53

But, perhaps the most serious concern raised about the changing role of NGOs in humanitarian crises, is the fact that they may actually contribute to the escalation of violence surrounding the crisis. James Ingram notes that, in their eagerness to respond, NGOs have at times brought in high value food supplies like dates, white flower, and sugar that can command high prices on the black market. As a result, the food shipments become even more a target of looters, eager to sell the food in order to procure more weapons.54

The reliance on NGOs for carrying out humanitarian food operations when government and multilateral donors have largely withdrawn from a complex emergency, may become an important contributing factor to outside military intervention. This appears to be one of the lessons to be drawn from the Somalia experience. As the food situation in Somalia worsened in the 1992, food prices soared making it a target of looters because of the exaggerated price. Food is often available in famine situations, but the price is so high that those in need of it often cannot afford it. This was the situation in Somalia in 1992, where in some regions food prices has soared by 1200 percent. As a result, food became a favorite target for looters wanting to cash in on its exaggerated value. As a counter strategy, the United States and other donors flooded the country with food, depressing food prices and making food more widely available. As food prices returned to more normal levels, clan militias and local thugs began stealing even more food in order to keep their incomes stable and to continue buying weapons. Since this food was being transported and distributed largely by international NGOs, they became targets of a growing number of attacks. As Andrew Natsios notes:

It is axiomatic that when the relief effort becomes the major employer and source of wealth in a country torn apart by violence, relief organizations are at risk of involuntarily surrendering their neutrality and becoming a tool of the combatants. This is the point at which military or police intervention becomes essential if relief efforts are to continue to serve the vulnerable and not contribute involuntarily to increasing violence.55

As attacks on relief convoys escalated, it is perhaps not surprising that the foreign NGOs working in Somalia played a key role in pressuring the US government and the UN to intervene to protect relief shipments. The Somalia intervention has thus become a symbol of another significant trend in the evolution of the global food aid system: rather than integrating relief and development, relief has become increasingly integrated with military power.56

SHIFTING NORMS, NEW TENSIONS

Hopkins and Puchala note that a key norm of the global food regime has been respect for national sovereignty and the illegitimacy of external penetration. In practice this has meant that, "production, distribution and consumption within the confines of national frontiers remained largely beyond the 'legitimate' reach of the international community, even under famine conditions, as long as national governments chose to exclude the outside world."57 As a result, within the global food regime, there has always been a tension between the desire to avoid starvation and respect for national sovereignty. When governments like that in Ethiopia in 1973, chose to ignore a famine and exclude outside assistance, there was little that national governments or international organizations could do. As Hopkins and Puchala note: "The world acquiesced because sovereignty was the norm, and hence the malnourishment of millions was not seen as a collective responsibility in any strong sense."58

However, beginning in the 1980s, the sovereignty norm has become increasingly challenged. The first moves in this direction were evident in the 1980s when donors began to support, if only quietly, cross-border operations by NGOs distributing food relief outside government controlled areas, such as Eritrea and Tigre in Ethiopia. This trend became even more pronounced in the post-Cold War period with UN sanctioned operations in Northern Iraq to provide relief supplies to the Kurds, and the subsequent military intervention in Somalia to protect food relief shipments.

This new approach of integrating relief with a military presence has been given the seemingly oxymoronic label, "military humanitarianism."59 For some, this development opens up new and innovative possibilities for using the logistical and organizational skills of military forces for humanitarian purposes rather than destructive uses, a task that is seen as more appropriate for a new world order.

However, the decline of the norm in favor of national sovereignty, has given rise to new tensions within the emergency food aid system. A fundamental principle established in international humanitarian law has been the need to respect the principles of neutrality and impartiality in all relief operations, particularly in conflict situations.60 Thus, the question being asked increasingly is if one can override the principles of national sovereignty in order to distribute food in a humanitarian crisis without also violating the principles of neutrality and impartiality. On this issue, there does not yet appear to be a clear consensus of opinion. Instead, three schools of thought seem to be emerging which I will call, the "food through force" school, the "negotiated access" school, and the "radical humanitarianism" school.

According to the "food through force" school, complex emergencies are fuelled by an "appetite for violence and retribution" which threaten to overwhelm relief operations and spill over into neighboring countries. As Andrew Natsios, Vice President for World Vision notes, "Intervention in complex humanitarian emergencies makes eminently good policy sense as a preventive measure to keep chaos from spreading beyond national boundaries, with the potential to endanger regional stability and international peace."61 Although Nastios feels that military intervention to distribute relief supplies should be a last resort, the earlier it is invoked in a humanitarian crisis the better. At the same time, he insists that such military operations should maintain strict political neutrality and not be seen to take sides in the conflict. The protection of the neutrality of relief efforts, Natsios suggests, "will sometimes require military assertiveness and a willingness to wage combat."62 The task confronting the international community then seems to be to identify the conditions under which intervention should take place and explore ways in which military forces can be effectively integrated into the relief efforts of NGOs.63

The "negotiated access" school challenges the assumption that military force can be used to assist the distribution of food supplies in conflict situations without undermining the vital principles of neutrality and impartiality. As James Ingram notes, "Minimizing national sovereignty as the governing principle of international organization is a poor foundation for building a durable world order."64 Thus, Ingram is skeptical either of efforts to use military force to forcibly distribute food supplies, or of engaging in "making judgments that one side or the other may see as politically motivated and hence acceptable."65 Instead, Ingram favors negotiating access to conflict ridden areas with the key parties involved. The main goal should be the immediate saving of lives of those most seriously affected by the conflict. The negotiation of access demands the strictest adherence to the principles of neutrality and impartiality in order to gain the trust of the opposing factions. This approach would seem to fit well with the emerging division of labor in the global food regime, noted earlier in this article. A UN agency, such as the WFP or the Department of Humanitarian Affairs, would negotiate access to the conflict area. The UN would mobilize the funds and coordinate the logistics of transporting food to the area, and NGOs would carry out the actual distribution of food supplies.

Interestingly, although Ingram is a former Executive Director of the WFP who himself has been involved in several such negotiations, he feels strongly that neither the WFP or any other UN agency should play the lead role in negotiating access to complex emergencies. This is because the political motives of the United Nations, as an intergovernmental organization, are inherently suspect, even in cases where its objectives are clearly humanitarian. Instead, he suggests that a new international NGO could be created, or the International Committee of the Red Cross remodelled, in order to have a truly politically neutral actor to negotiate access for relief supplies in conflict situations. The main thrust of Ingram's proposal is that in order relieve the suffering of a large number of people quickly, it is important "if the political functions of conflict resolution and forcible intervention are separated as much as possible from the function of increasing access to the victims of conflicts."66

Ingram recognizes that gaining access in many conflict situations is not an easy task. In cases where access has not been granted, he suggests it is sometimes the fault of donor agencies who have tried to pursue objectives that went beyond the simple humanitarian one of feeding the greatest possible number of people in need. In such cases, he suggests that donor governments can play a role in pressuring both sides of the conflict to come to an agreement regarding humanitarian access.67

In contrast to the two previous approaches, the "radical humanitarianism" school questions the very assumptions under which recent food relief efforts have been carried out. This perspective rejects, on the one hand, the notion that military intervention provides any real solution to the problem posed by complex political emergencies. On the other hand, this perspective questions the concepts of neutrality and impartiality upon which the negotiated access approach is based. Mark Duffield, for example, suggests that the policy of negotiated access represents an accommodation of the North with the growing number of permanent emergencies in the South. Donors in the North are increasingly accepting permanent emergencies and high levels of violence as normal. In doing so, humanitarian food aid efforts are becoming integrated into the cycle of violence.68

Perhaps one of the most scathing critiques of the principles of neutrality and impartiality has been written by Alex De Waal and Rakiya Omaar in their analysis of the international response to the Rwandan crisis. De Waal and Omaar suggest that many NGOs muted their criticism of the participants in the Rwanda genocide in order to keep their relief operations going. They suggest further that many NGOs became more preoccupied with calling in UN troops to protect their relief operations than in responding to the genocide itself. As a result, the NGOs fell into a clever trap, ending up providing food to the perpetrators of the genocide in refugee camps in Zaire and thereby prolonging the conflict. Like Duffield, they conclude that "relief aid delivered by international agencies has become integrated into the processes of violence and oppression."69

This situation has come about, de Waal suggests, because NGOs have confused the principles of "operational neutrality" and "neutrality of principle."70 A commitment to human rights necessitates a consistent application of the concept of "objectivity" or "neutrality of principle," which means in practice "assessing the parties to a conflict according to the same standards."71 Since some actors in a conflict may violate human rights more flagrantly than another, "neutrality of principle" often means that "one party is criticized far more than other."72 This implies a willingness on the part of NGOs to face expulsion if their criticisms offend the governing powers.

However, de Waal suggests that, as their role in humanitarian operations has increased, NGOs have become more preoccupied with appearing to be neutral in order to protect the continuation of their relief operations, thus placing greater emphasis on "operational neutrality." Even those agencies that take a fairly radical approach in the development projects suddenly have become conservative and muted in their criticisms when it comes to relief operations. When it appears that they can no longer adhere to their human rights mandate and, at the same time, keep their relief operations functioning the temptation is for NGOs "to panic and call for international military intervention."73 As a result, de Waal fears that NGOs, in their preoccupation with maintaining their relief operations, have closed off other, non-military options, which may do more to address the long-term human rights situation. In the case of Rwanda, de Waal feels that the international community should have done something much sooner to bring pressure on those responsible for the genocide, such as the expulsion of Rwanda from the Security Council, the expulsion of Rwanda's ambassadors, the imposition of economic sanctions, and a public call for prosecution for genocide of specific government officials. Earlier action directed at halting the human rights abuses, and not preoccupation with protecting NGO operations, according to de Waal, would have done much to halt the genocide.

CONCLUSIONS

Developments since the end of the Cold War have significantly transformed the environment in which the global food aid regime operates. As a result of the growing number of complex political emergencies, the demand for emergency food aid has mushroomed in recent years. This has generated growing competition within the food aid system itself, as donors are increasingly tempted to decrease long-term development food aid expenditures in order to expand their emergency responses. This not only places increased pressure on already dwindling development budgets, but also threatens to undermine some of the major principles of the development food aid regime.

As a result of these developments, an effort is underway to rethink some of the major tenets of the emergency food aid system. Donors have begun exploring new policy paradigms such as the concept of a relief-to-development continum. Agencies most directly affected by the growing shift to emergency food aid programming are looking for new ways to stabilize budgets and protect their longer term development projects. At the same time, new actors such as NGOs and the military have come to play an increasingly significant role in the food aid system in comparison with previous periods. This has led to a growing debate on the relationship between such principles as respect for national sovereignty and impartiality and neutrality in the distribution of food supplies.

On one level, it is tempting to interpret these developments in a positive light. Ellen Messer, for example, sees the emergence of a "New Humanitarianism" in which ". . . some members of the international community no longer wait for a sovereign state to declare a famine and ask for aid, but intervene, using increasingly well-constructed humanitarian principles."74 Thus, she sees a new alliance emerging between humanitarians, advocates of the basic right to food, NGOs, and the military, all of whom are "reinforcing efforts to articulate principles of humanitarian access, to accelerate mechanisms including the use of military force to deliver food to zones of armed conflict, and to involve all possible global to local forces or factions in the struggle to ensure that everyone has access to adequate food."75 It would appear that as traditional norms, such as respect for national sovereignty, are relaxed the "anti-starvation regime" referred to by Peter Uvin has been significantly strengthened.

However, evidence suggests that a more cautionary note needs to be sounded. Some of the developments of the past few years have been essentially coping strategies by various actors within the aid system to protect development budgets and principles that have evolved under the notion of the development food aid regime. As the sovereignty norm has been relaxed, new tensions between the need to feed people in conflict situations and the principles of neutrality and impartiality have emerged. Despite Messer's contention that "well-constructed humanitarian principles" are emerging, we have noted that, in fact, there are three distinct schools of thought on how food aid should be delivered in conflict situations. As their role in the food aid regime grows, the debate over the conduct of NGOs in dealing with complex political emergencies is only just beginning. Finally, as attempts to formalize and professionalize emergency food aid continue, the danger is that the North is simply finding new ways of accommodating the growing number of complex emergencies in the South. Instead of strengthening an "anti-starvation regime," we may be witnessing the transformation of the global food aid regime into one of the North's primary vehicles for containing and accomodating within acceptable humanitarian boundaries the growing level of violence and chaos in some regions of the South. This abdication of international collective responsibility may only contribute to higher levels of poverty, violence, and starvation in the South in the future.

Mark W. Charlton is Associate Professor of Political Science at Trinity Western University in Langley, BC.

Endnotes

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, Montreal, June 1995. The author wishes to acknowledge the helpful comments of Gerald Schmitz and the journal referees.

1. Raymond Hopkins and Donald Puchala,

The Global Political Economy of Food (Madison,

WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1978), p. 23.

Return to body of article

2. Peter Uvin, The International Organization of

Hunger (London: Kegan Paul International, 1994), p. 148.

Return to body of article

3. Ibid., p. 138.

Return to body of article

4. WFP/CFA: 35/17, para. 18.

Return to body of article

5. Quoted in David Gillies, "Human Rights or State Sovereignty? An Agenda for

Principled Intervention," in Mark Charlton and Elizabeth Riddell-Dixon, eds.,

Crosscurrents: International Relations in the Post-Cold War

Era (Scarborough, ON: Nelson Canada, 1993), p. 462.

Return to body of article

6. Thomas Weiss and Larry Minear, "Do International Ethics Matter? Humanitarian Politics in

the Sudan," Ethics and International

Affairs, 5 (1991), pp. 212-13.

Return to body of article

7. For an excellent overview of these developments, see Raymond F. Hopkins, "Reform in

the international food aid regime: the role of consensual knowledge,"

International Organization, 46, no. 1 (Winter 1992), pp. 225-64.

Return to body of article

8. For a discussion of this shift in focus in the Canadian food aid program, see Mark

Charlton, The Making of Canadian Food Aid

Policy (Montreal, PQ: McGill-Queen's University

Press, 1993).

Return to body of article

9. For background on the history and operation of the WFP, see Ross B. Talbot,

The Four World Food Agencies in Rome (Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1990). A discussion of

the growing interest of the WFP in structural adjustment and linkages with the World Bank can

be found in Mark Charlton, "Innovation and inter-organizational politics: the case of the

World Food Programme," International

Journal, XLVII (Summer 1992), pp. 630-65.

Return to body of article

10. Hopkins, "Reform in the international food aid regime," p. 244.

Return to body of article

11. Ibid.

Return to body of article

12. FAO, Food Aid in Figures, 1993 Volume

11 (Rome: 1993), Table 39.

Return to body of article

13. WFP/IGC: 17/5 Rev. 1, para. 78.

Return to body of article

14. Andrew Natsios, "Food Through Force: Humanitarian Intervention and U.S. Policy,"

The Washington Quarterly, 17, no. 1 (Winter 1994), p. 129.

Return to body of article

15. Edward Clay and Olav Stokke, "Assessing the Performance and Economic Impact of Food

Aid: The State of the Art," in Edward Clay and Olav Stokke, eds.,

Food Aid Reconsidered: Assessing the Impact on Third World

Countries (London: Frank Cass, 1991), p. 23.

Return to body of article

16. World Food Program,

Annual Report, 1993: Peacemakers for the

Future (Rome: WFP, 1993), pp. 115-16.

Return to body of article

17. Clay and Stokke, "Assessing the Performance and Economic Impact," p. 23.

Return to body of article

18. Cf. Margaret Buchanan-Smith and Simon Maxwell, "Linking Relief and Development:

An Introduction and Overview," IDS

Bulletin, 24, no. 4 (October 1994).

Return to body of article

19. Joanna Macrae and Anthony B. Zwi, "Food as an Instrument of War in Contemporary

African Famines: A Review of the Evidence,"

Disasters, 16, no. 4 (1991), p. 300.

Return to body of article

20. Ibid., p. 84.

Return to body of article

21. Buchanan-Smith and Maxwell, "Linking Relief and Development," p. 3. The entire

October 1994 issue of IDS Bulletin is devoted to the theme of linking relief and development.

Return to body of article

22.. Wolfgang Herbinger, "The World Food Programme's Response to the Challenge of Linking

Relief and Development," IDS

Bulletin, 25, no. 4 (October 1994), p. 96

Return to body of article

23. Mark Duffield, "Complex Emergencies and the Crisis of Developmentalism,"

IDS Bulletin, 24, no. 4 (October 1994), p. 40.

Return to body of article

24. Herbinger, "The World Food Programme's Response," pp. 96-100.

Return to body of article

25. James Ingram, "The Future Architecture of International Humanitarian Assistance," in

Thomas G. Weiss and Larry Minear, eds., Humanitarianism Across Borders: Sustaining Civilians

in Times of War (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1993), p. 175.

Return to body of article

26. Buchanan-Smith and Maxwell, "Linking Relief and Development," p. 9.

Return to body of article

27. Duffield, "Complex Emergencies and the Crisis of Developmentalism," p. 38.

Return to body of article

28. Tim Shaw and John Inegbedion, "The Marginalization of Africa in the New World

(Dis)Order," in Richard Stubbs and Geoffrey R.D. Underhill, eds.,

Political Economy and the Changing Global

Order (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1994), p. 391.

Return to body of article

29. Ibid., p. 393.

Return to body of article

30. Ibid.

Return to body of article

31. Macrae and Zwi, "Food as an Instrument of War," p. 300.

Return to body of article

32. Boutros Boutros-Ghali,

Building Peace and Development: 1994 (New York: United

Nations, 1994), pp. 8-9.

Return to body of article

33. Macrae and Zwi, "Food as an Instrument of War," p. 300.

Return to body of article

34. Ellen Messer, "Food Wars: Hunger as a Weapon of War in 1993," in Peter Uvin, ed.,

The Hunger Report: 1993 (Langhorne, PA: Gordon and Breach, 1994), p. 43

Return to body of article

35. Boutros-Ghali, Building Peace and

Development, p. 9.

Return to body of article

36. Duffield, "Complex Emergencies," p. 40. For another view of the relief-development

debate, see Barry Stein, "Rehabilitation and Complex Emergencies: In the Middle of the

Continuum from Relief to Development," Paper presented at the 36th Annual International Studies

Association Conference, Chicago, 21-25 February 1995. Stein argues that an attempt to inject

a development component into relief programs may make them too complicated to

adequately address the need for a quick response. He advocates greater focus on linking relief

programs to rehabilitation as a more achievable objective.

Return to body of article

37. Cf. Uvin, International Organization of

Hunger, chap. 5.

Return to body of article

38. Quoted in WFP: CFA: 6/21, p. 37.

Return to body of article

39. WFP/CFA: 31/17(1991), para. 61.

Return to body of article

40. WFP/CFA: 35/17 (1992), para. 24.

Return to body of article

41. James Ingram notes that such consolidated appeals have a deleterious effect on the aid

giving process. Once a consolidated appeal is made and donors commit resources, UN agencies

then frequently engage in lengthy negotiations to determine the inter-agency allocation of the

funds, thus delaying the response to the emergency. Ingram, "The Future Architecture," p. 177.

Return to body of article

42. WFP/CFA: 22/7, para. 28.

Return to body of article

43. Herbinger, "The World Food Programme's Response," p. 100.

Return to body of article

44. WFP/CFA: 31/17 (1991), para. 58.

Return to body of article

45. WFP Press Release/1014, 5 May 1995, "WFP Needs $24.5 million to address food

shortage in Iraq."

Return to body of article

46. WFP, Food Aid

Monitor, June 1995, Table 1. Available on the Internet at the UN's

Department of Humanitarian Affairs gopher site in Geneva.

Return to body of article

47. Charlton, The Making of Canadian Food Aid

Policy, p. 48.

Return to body of article

48. "WFP, CRS sign joint working agreement,"

Food Forum, (December 1994/January 1995),

pp. 1 and 3.

Return to body of article

49. Messer, "Food Wars," p. 49.

Return to body of article

50. Ibid.

Return to body of article

51. For some accounts of such cases, see J. Millard Burr and Robert O. Collins,

Requiem for the Sudan: War, Drought, and Disaster Relief on the

Nile (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1995).

Return to body of article

52. Cf. Macrae and Zwi, "Food as an Instrument of War." See some of the case studies in

Joanna Macrae and Anthony Zwi, eds., War and Hunger: Rethinking International Responses to

Complex Emergencies (London: Zed Books, 1994).

Return to body of article

53. Simon Maxwell and Alemayehu Lirenso, "Linking Relief and Development: An

Ethiopian Case," IDS Bulletin, 25, no. 4 (October 1994), p. 73.

Return to body of article

54. Ingram, "The Future Architecture," p. 178.

Return to body of article

55. Natsios, "Food Through Force," p. 136.

Return to body of article

56. A common assumption among many is that the international response to Somalia was

largely driven by media coverage, especially by CNN. For a critique of this assumption, see

Steven Livingstone and Todd Eachus, "Famine, Floodlights, and U.S. Foreign Policy:

Reconsidering the CNN Effect in the Case of Somalia," Paper presented at the 36th Annual International

Studies Association Conference, Chicago, 21-25 February 1995.

Return to body of article

57. Hopkins and Puchala, "Perspectives on the International Relations of Food," p. 25.

Return to body of article

58. Ibid.

Return to body of article

59. Thomas Weiss and Kurt Campbell, "Military Humanitarianism,"

Survival, 33, no. 5 (September/October 1991), pp. 451-65.

Return to body of article

60. For a review of international law in the area of humanitarian assistance, see Michel

Veuthey, "Assessing Humanitarian Law," in Thomas G. Weiss and Larry Minear, eds.,

Humanitarianism Across Borders: Sustaining Civilians in Times of

War (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1993).

Return to body of article

61. Natsios, "Food Through Force," p. 143. It is interesting to note that Natsios also served

as director of the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance in the US Agency for International

Development from 1989 to 1993.

Return to body of article

62. Ibid., p. 137.

Return to body of article

63. A discussion of these issues can be found in several chapters of Weiss and Minear,

Humanitarianism Across Borders, Part II.

Return to body of article

64. Ingram, "The Future of Assistance," p. 192.

Return to body of article

65. Ibid., p. 185. A Médecins Sans Frontière report suggests that military intervention in

Somalia actually ended up increasing the vulnerability of NGOs and led to more violent attacks

against them. In fact, more NGO relief workers were killed in Somalia following the intervention

than before. Cf. Francois Jean, ed., Life, Death and Aid: The Médecins Sans Frontière Report

on World Crisis Intervention. (London: Routledge, 1993), pp. 99-107.

Return to body of article

66. Ingram, "The Future of Assistance," p. 190.

Return to body of article

67. Ibid.

Return to body of article

68. Duffield, "Complex Emergencies," pp. 41-43.

Return to body of article