by Benjamin Fordham

INTRODUCTION

Accounts of the American military buildup that began in 1950 nearly always focus on a policy statement entitled "United States Objectives and Programs for National Security," better known by its file number: NSC 68. The report, which a joint State and Defense Department working group submitted to the president on 7 April 1950, held that the Soviet Union was engaged in an all-out effort to extend its influence and control over all regions of the world. Furthermore, it asserted that the means available to the Kremlin were considerable and growing constantly. Arguing that "[t]hese risks crowd in on us, in a shrinking world of polarized power, so as to give us no choice, ultimately, between meeting them effectively and being overcome by them," NSC 68 concluded that "it is clear that a substantial and rapid military building up of strength in the free world is necessary to support a firm policy necessary to check and roll back the Kremlin's drive for world domination."2

The rearmament program NSC 68 initiated marked a turning point in US foreign policy, militarizing what had been primarily an economic and diplomatic effort to contain the Soviet Union.3 While the report's rhetoric about the Soviet threat was nothing new, and subsequent policy statements including later versions of NSC 68 itself were also associated with large increases in defense spending, NSC 68 is significant because it put an end to the Truman administration's efforts to restrain military spending. Indeed, in real terms, US military spending has never returned to the levels prevailing before 1950. The reasons for this shift in policy have been a source of continuing interest to historians of US foreign relations.

CONTENDING EXPLANATORY APPROACHES TO POLICY CHANGE

In addition to its importance in the history of US foreign policy, the development of NSC 68 presents an opportunity to compare two contrasting analytical approaches to the policy-making process. The first approach, associated with the realist school of international relations theory, and with historiography stressing the importance of consensual "core values" or a "national security imperative," interprets policy-making as the response of the state, understood as a unitary actor, to events and conditions in the international system.4 The second approach, associated with the emerging international relations literature on the importance of domestic politics and with some revisionist interpretations of US foreign policy, focuses on conflicting understandings of these international events and conditions, and treats policy outcomes as the result of political conflict among domestic advocates of these different interpretations. These two approaches imply very different accounts of the development of NSC 68.

The role of domestic politics in explaining foreign policy outcomes is usually discussed in terms of the relative importance of domestic and international factors, a formulation that obscures the real stakes in the debate. Everyone agrees that decision makers respond to international events. The fundamental question is whether the policy implications of these events can be understood without knowing who is interpreting them. Do "national security imperatives" have the same meaning to everyone, or would a different set of policy makers view them another way? Does everyone interpret international events in terms of the same set of "core values?"

If international events and conditions hold the same meaning for everyone, then policy-making can be treated as a learning process in which policy makers work to discern the imperatives of the international system. Apart from the fact that some individuals are wiser or learn more quickly than others, the identity of those making the decisions is not very important. This theoretical perspective implies a historical account that focuses on state responses to international events, rather than on conflict among decision makers over the policy implications of international conditions. Sophisticated versions of this theoretical framework, such as the one advanced by Melvyn Leffler, acknowledge that the "core values" decision makers use to interpret events are rooted in historical conflicts within the state and society.5However, these conflicts precede the decision-making process and play no direct role in it.

If one presumes that a different group of policy makers might interpret the same events and conditions differently, then the process is better understood as a political struggle between advocates of different interpretations seeking control of state policy. Rather than relegating conflicts about appropriate policy goals and priorities to a period before agreement on the present core values, historical accounts adopting this perspective place these conflicts at the center of the policy-making process. Policy change might result from a change in the group interpreting international conditions rather than from a change in the international conditions themselves. Indeed, without knowing the priorities of the group controlling the policy-making process, it is difficult to know what response any event will evoke.

Both these understandings of the policy-making process are alive and well in international relations theory and the historiography of the Cold War. Although it has many detractors, realist international relations theory treating the state as a unitary actor is still the dominant approach to understanding the development of policy on security issues.6 The unitary actor assumption has considerable analytical advantages, particularly in the examination of strategic interaction between states, and is implied by many common explanatory concepts, such as the notion of "national interest." Many historians of US foreign policy during the early Cold War era also make an implicit unitary actor assumption, stressing the importance of security concerns and arguing that international events and conditions demanded that policy makers respond in particular ways. These accounts generally stress the inability of those opposed to these policy responses to put forward a coherent alternative.7

A growing body of international relations theory disputes the realist argument that the nature of the domestic political regime does not change the influence of international events.8 Even an apparently homogenous group of decision makers of the same class, gender, and ethnicity often have different goals and priorities. They may view the same international events and conditions very differently. What appears as an overwhelming threat to one group may be less important than other considerations for another. Within a less uniform group, wider differences are likely. During the early Cold War era, Democrats and Republicans disagreed in important ways about the appropriate level of military spending and foreign aid. Even within the Truman administration, officials disagreed about the relative importance of balancing the budget and committing greater resources to achieve foreign policy goals. When there is disagreement about goals and priorities, it is inappropriate to treat policy as if it reflected a consensual set of core values. Recognizing the importance of conflict over policy, some historians have raised the possibility that different sets of decision makers might have perceived international events differently and chosen other policies.9

These two approaches to the policy-making process lead to different expectations about cases of major policy change such as the development of NSC 68. The range of processes compatible with a unitary actor assumption, or a presumed set of consensual core values, is rather narrow. Since it holds that alternative policies do not emerge from domestic politics, historical accounts rooted in this perspective associate external events with policy change, arguing that they drive policy makers toward recognition of the imperatives of the international system. Most historical accounts of NSC 68 use external events as explanatory devices.10 The alternative approach stressing domestic political conflict, on the other hand, links policy choice to the struggle for control of the policy-making apparatus among groups with contending interpretations of the international environment. The case of NSC 68 affords an opportunity to evaluate which of these two approaches explains the process of policy change best. Although policy-making during the early Cold War era is considered a strong case for those stressing realist geopolitical imperatives or core values, the evidence I will present here indicates that the domestic political conflict approach accounts for more of the evidence about the policy-making process.

THE IMPORTANCE OF "PROCESS"

Unitary actor models of state behavior are not usually intended to explain the policy-making process. Nevertheless, although some analysts appeal to the argument that a causal process may proceed "as if" a necessary assumption were true, most of those who acknowledge making a unitary actor assumption also argue that it is reasonably realistic. For example, Bruce Bueno de Mesquita contends that the most useful and realistic way to justify this assumption is to argue that the decision-making process is dominated by a single strong leader. George Downs and David Rocke offer a formal proof that, under some conditions, decisions subject to the influence of advisers may be consistent with the utility function of a unitary, rational actor.11 These arguments are important. Even when a theory makes correct predictions about outcomes, it must offer some account of the causal process involved. Without a sense of process, it is difficult to be sure empirical associations are not spurious, even if they are statistically significant.12 The lack of a compelling sense of process can prevent even an empirically supported theory from gaining acceptance. Difficulty in specifying the causal process involved is one of the reasons many scholars doubt the argument that democracies do not go to war against each other in spite of the evidence offered to support it.

Since process is theoretically important, it makes sense to examine it directly. Theories imply empirically testable propositions about how outcomes are generated, although more than one process may fit a theory. These empirical statements can be examined using what Alexander George and Timothy McKeown call "process tracing." This method uses evidence about various features of the decision-making environment, including both the actors' definitions of their situation and the institutional arrangements affecting their attention, information-processing and behavior. George and McKeown argue that a good account of the decision-making process must explain a "stream of behavior through time .... Any explanation of the processes at work thus not only must explain the final outcome, but must also account for this stream of behavior."13

George and McKeown note that process-tracing must not only recreate actors' "definitions of the situation," but also contain a "theory of action."14 Such a theory is necessary to fit isolated pieces of historical evidence into a coherent pattern, and to fill the gaps in this evidence in a logical way. Bounded rationality, misperception, lags, or other special assumptions may be part of this theory of action, but the conditions under which they apply must be clearly articulated and applied consistently throughout the analysis. One could easily account for everything in a stream of behavior using ad hoc assertions about misperception, mistakes or lags. While such accounts may be artful, they do not shed any light on the usefulness of the underlying theoretical propositions.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF NSC 68

At first glance, it is tempting to attribute the development of the rearmament program associated with NSC 68 to the broad pattern of tension between the United States and the Soviet Union after World War II. However, because this atmosphere of conflict was a fairly constant feature of the international environment between 1945 and 1950, it does not explain the timing of the rearmament program. While this pattern of conflict no doubt explains why some decision makers supported rearmament well before NSC 68 put their sentiments in writing, it cannot account for previous presidential decisions to cut the military budget. A satisfying explanation for NSC 68 must focus on considerations specifically linked to this particular policy initiative rather than on the general conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Shorn of the considerable historical detail they offer, the account of the development of NSC 68 offered by most historians who use a realist approach, such as Samuel Wells, or stress consensual core values, such as Melvyn Leffler, is simple. As Wells puts it, several events in the fall of 1949 "struck the United States like a series of hammer blows." Concern about these events, especially the Soviet acquisition of the atomic bomb and the collapse of the Nationalist regime in China, led directly to the writing of NSC 68.15 Nevertheless, President Truman's desire to avoid large budget deficits made him reluctant to approve such a costly new policy, and the report languished in bureaucratic obscurity until the Korean War.16

While plausible, this realist interpretation of the development of NSC 68 within the administration does not withstand close scrutiny. I will first review the evidence Wells and Leffler offer to support their argument about the impact of the "hammer blows" of 1949. In fact, these events were substantially discounted when they happened and were immediately followed by a reduction in the military budget. Next, I will examine the argument that the administration would not have proposed a rearmament program without the Korean War. Here, the bulk of the evidence indicates that President Truman decided to propose some rearmament program to Congress soon after he received NSC 68. Finally, I will review evidence supporting the argument that political changes within the administration, rather than a unifying effect produced by external shocks, led to presidential approval of NSC 68.

Why Was NSC 68 Written?

The most serious problem with the argument that the events of 1949 created a sense of crisis within the administration is that they were followed by a decision to cut the military budget. This reduction was originally proposed by Frank Pace, the Director of the Bureau of the Budget, and presented to the cabinet by the president on 1 July 1949.17 Afterwards, the NSC undertook a study of the effects of these cuts. This study and the responses to it, which became the NSC 52 series, were discussed by the Council and approved by the president on 30 September 1949, just one week after Truman publicly announced the detection of the Soviet atomic test.18 Although the State Department objected to cuts in the newly approved Military Defense Assistance Program, the budget the president sent to Congress in January 1950 contained nearly all the reductions Pace had originally recommended, including a smaller military budget. Truman's refusal to increase the military budget in 1949 suggests that he shared the concern of many of his advisers about the effects of a large budget deficit.

Evidence of policy makers' reactions to the 1949 events indicates that they caused no great alarm. The fall of the Nationalist regime in China had been anticipated long before the proclamation of the People's Republic in October 1949. Virtually every intelligence report and policy discussion concerning China after the Marshall mission in 1947 either predicted or assumed the collapse of the Nationalist regime. For example, a CIA Special Evaluation dated 21 July 1948, commented that "[t]he Chinese National Government is now so unstable that its collapse or overthrow could occur at any time."19 The Secretary of State acknowledged this consensus at a February 1949 NSC meeting. "[Acheson] said there was general agreement that, from a strategic point of view, China was an area of lower priority, especially since the house appeared to be falling down and there was not much to be done until it had come down."20 The State Department's China White Paper, released in July, publicly acknowledged that the civil war in China was effectively over, and the United States had to "face the situation as it exists in fact."21 If the fall of China helped motivate NSC 68, then the attitude of the State Department, the organization most active in developing the policy, is very difficult to explain.

Similarly, the Soviet acquisition of atomic weapons occurred before the September 30 NSC meeting and was substantially discounted at the time. The Soviet atomic test may have strengthened the convictions of Paul Nitze and others in favor of more spending, but they already held these opinions before this discovery was made. It did not change the outcome of the debate over the military budget reductions, and there is no evidence that it converted any of the advocates of these cuts. George Kennan argued in February 1950, when the writing of NSC 68 was already underway, that "[t]he demonstration of an 'atomic capability' on the part of the U.S.S.R. likewise adds no new fundamental element to the picture . . .. The fact that this situation became a reality a year or two before it was expected is of no fundamental significance."22 Leffler, whose account of NSC 68 does not rely on this event, notes that public reaction to the event also quickly subsided and was not a major consideration in subsequent decisions about American weapons development.23 An October 1949 edition of the State Department's secret "Weekly Review" of world events stated that there was no evidence the new weapon would change Soviet foreign policy and commented that the US still retained the upper hand. In Truman's copy of this document, the passage making this point is underlined in red.24

The major proponents of NSC 68 were already convinced of the need for greater military spending before the "hammer blows" of 1949. While these events may have strengthened their convictions about the need for a greater resource commitment to the national security program, their opinions on this issue developed from broader concerns about the economic situation in Europe and the viability of the NATO military force. Paul Nitze has noted that his concern about military spending began in the spring of 1949, when he participated in joint military planning efforts with European officials. They estimated the cost of a defense capable of stopping a Soviet attack at the Rhine to be $45 billion. Nitze worried that Congress would only appropriate $1 billion for military aid.25 Furthermore, Leon Keyserling, who would provide the fiscal policy rationale for the rearmament program, told the president in August 1949 that "our economy can sustain in fact, must be subjected to policies that make it able to sustain such military outlays as are vital to [our national] objectives."26 The advocates of greater military spending did not need the Soviet atomic bomb or the fall of China to convince them of its strategic importance or economic viability.

In spite of the concerns of Nitze and others at the State Department, those seeking to reduce military spending prevailed in the fall of 1949. Most did not deny the existence of serious international threats, but instead argued that other priorities were just as important. At the September 30 NSC meeting, the fiscally conservative Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), Edwin Nourse, summed up their reasoning, stating that large deficits at a time of high business activity were "no less a risk than our diplomatic or military risks."27 While strenuous protests from the State Department eventually restored some of the foreign aid cuts, Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson blocked any effort by the military services to avoid cuts in their budget. Even the Soviet acquisition of the atomic bomb and the communist victory in China did not prevent these cuts.

When Was NSC 68 Really Approved?

Like the assertion that events during the fall of 1949 drove the writing of NSC 68, the argument that the administration would not have proposed a rearmament program without the Korean War is difficult to sustain. Although the president did not formally approve the report until 30 September, there is substantial evidence that he had decided to propose a rearmament program to Congress in the spring of 1950, before the North Korean attack on South Korea. It is clear that his closest advisers believed Harry Truman supported a rearmament program soon after it arrived on his desk on 7 April and planned to present it to Congress as soon as a legislative proposal was ready.

The little direct evidence of Truman's position on NSC 68 implies that he had informally approved the report. On 23 May, Truman reportedly encouraged Bureau of the Budget officials to raise any questions they had about NSC 68 programs, remarking that "it was definitely not as large as some of the people seemed to think." As Steven Rearden notes, these comments indicate both presidential uncertainty about the size of the program and an informal decision to proceed with rearmament.28 Truman's uncertainty about the size of the new budget was understandable, both because program details and budget estimates from the Department of Defense were not yet complete, and because he had to consider what Congress could be induced to accept. His instructions that the Bureau of the Budget should remain skeptical of these programs are similarly unremarkable, since this was the Bureau's role in all cases. The central point of debate, however, was whether the spending reductions contained in the fiscal 1951 budget then before the Congress would continue. The president's assumption that the military budget would increase indicates that he no longer supported further budget cuts.

Most of the evidence about the president's attitude toward the rearmament program comes from the statements and actions of his advisers. Acheson comments in his memoirs that NSC 68 "became national policy" after it was discussed by the NSC in April.29 He was not alone in thinking Truman endorsed plans for rearmament. White House Special Counsel Charles Murphy was preparing a major presidential address based on NSC 68 as soon as the preliminary cost estimates were ready. Murphy could not have made such ambitious plans without the president's authorization. In April, Truman had requested that these estimates be prepared as quickly as possible. The timetable for their submission was subsequently accelerated so that they could be available for an anticipated presidential address in early June.30 Although the complicated task of planning a new military budget could not be completed until September, the White House's efforts to accelerate the process are a strong indication of presidential support for rearmament.

Truman's decision to appoint Averell Harriman as a Special Assistant to the President offers additional evidence of the president's plans. At the suggestion of the State Department, Sidney Souers, the former Executive Secretary of the NSC, suggested to the president on 8 June that he appoint Harriman to oversee matters relating to NATO and the dollar gap problem, "and to interest himself in coordinating the implementation of various phases of NSC 68." According to Souers, Truman "indicated great interest in the program and thought it would be a fine solution."31 With the president's approval, Harriman assumed his new post on 16 June. Truman's endorsement of plans for the "implementation" of NSC 68 is a clear indication that he supported the policy it represented.

Harriman and the others charged with securing Congressional approval for NSC 68 programs faced a difficult task. Prevailing Congressional sentiment favored additional cuts in the military budget, and Arthur Vandenberg, who had been the most important coordinator of Republican support for the administration's foreign policy in the Senate, was confined to his Michigan home by cancer. While the administration kept its plans for the defense budget secret at Truman's insistence, both the White House and the State Department sought to find some way to secure Congressional approval for rearmament. It is obviously impossible to know if the administration could have pushed the rearmament program through Congress without the political boost provided by intervention in Korea. It is clear, however, that they planned to try. While the obstacles to success were daunting, administration officials had overcome formidable opposition to previous foreign policy initiatives. Plans for another such effort provide additional evidence that Truman had accepted the program before 25 June and raise questions about the assertion that rearmament would never have happened without the war in Korea.32

The first moves toward building Congressional support for rearmament were suggested by the State Department, which had already shown NSC 68 to a few influential individuals outside the government.33 Under Secretary of State James Webb interrupted the president's vacation in Key West on 26 March to show him NSC 68 and ask him to bring John Foster Dulles into the administration in an effort to mend the tattered fabric of bipartisanship. Since his departure from the Senate, Dulles had written to Acheson expressing his support for administration policy even when it was opposed by other Republicans, hinting that he could be useful in the State Department. Although the president initially hesitated to make such an appointment, he finally agreed on 4 April and Dulles joined the administration as a consultant to the State Department on 26 April.34

In addition to using Dulles as a bridge between the administration and Congressional Republicans, the White House and State Department tried to restore bipartisanship on foreign policy in other ways. Soon after Truman returned from Key West, Acheson attempted to set up a formal consultation arrangement with the Senate Republican leadership. On 18 April, Truman and Acheson announced an agreement with Styles Bridges, the ranking Republican on the Armed Services and Appropriations Committees, to consult with a committee of five Republican Senators. This group was to include Bridges, Robert Taft (Chair of the Republican Policy Committee), Eugene Millikin (Chair of the Republican Party Conference), Kenneth Wherry (Senate minority leader) and Alexander Wiley (the ranking Republican on the Foreign Relations Committee).35 Although he could not participate, Vandenberg encouraged the arrangement, informing Acheson that Bridges was "coming around" to the internationalist position, despite his anti-administration rhetoric.36 The State Department also initiated a series of informal "smokers" with influential members of Congress, especially Republicans. Robert Taft, for one, received an invitation to a gathering scheduled for 10 May.37

Bipartisan cooperation could not be achieved through mere meeting and consultation, however. Many Republicans greeted news of the Dulles appointment with skepticism. Robert Taft prepared a statement for the smoker to which he had been invited noting that "[n]o policy can become bi-partisan by the appointment of Republicans to executive office, although we hope that recent appointments are intended as a move toward the establishment of closer relations with the elected Republicans in Congress."38 The consultation arrangement set up through Styles Bridges also collapsed when the Democratic chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Tom Connally, objected to any arrangement that bypassed the members of his committee. Unwilling to offend Connally, Truman and Acheson scuttled the plan.39 To make matters worse for the State Department, many conservative Republicans simply refused to attend the smokers. In the midst of their effort to depict the State Department as an organization riddled with communist sympathizers, they were apparently reluctant to socialize publicly with State Department officials.40

It would have been naive to expect Congressional support without any political cost, and the president was prepared to pay a price for rearmament. Probably recognizing that they were unlikely to obtain both rearmament and progress on their social welfare agenda, the Fair Deal, Truman and his staff removed some major Fair Deal programs from their legislative agenda at the end of May. A comparison of White House staff member Stephen Spingarn's list of "top musts" from the president's legislative program, made at a White House staff meeting in November 1949, with his list of "urgent legislation" made at a similar meeting in May 1950, reveals the deletion of several such proposals. In particular, the repeal of the Taft-Hartley Act, the National Health Insurance Program, and the administration's farm subsidy proposals had been removed from the list of legislative priorities, despite the lack of positive action on them.41 These popular programs had played an important part in Truman's 1948 re-election campaign. Their accidental omission is highly unlikely. Indeed, the November and the May meetings on the legislative program both worked from the same printed list of legislative proposals. Changed priorities in light of NSC 68 offer a better explanation. The report had concluded that rearmament would require "[r]eduction in Federal expenditures for purposes other than defense and foreign assistance, if necessary by the deferment of certain desirable programs."42

To summarize, Truman's closest foreign policy advisers believed that he had effectively approved NSC 68 soon after receiving it, and needed only the final program and budget information before formally signing the report. Dean Acheson maintained that it was "national policy" in April. Charles Murphy, one of the most important members of the president's staff, joined the Ad Hoc Committee on NSC 68 and made plans for a presidential address on the subject as soon as the details of the program were complete. Sidney Souers was sure enough of the president's position on the matter to approach him about a plan for "implementation" of the program. The president endorsed several plans to gain Congressional support for a new foreign policy initiative in the period immediately preceding the Korean War. If Truman did not support rearmament, it is difficult to understand his actions and those of many of his closest advisers.

Why Did Truman Accept NSC 68?

It is very difficult to understand the development of the rearmament program in the administration in terms of a unitary actor model. Broad consideration of conditions in the international environment do not account for the timing of the program. Why cut the military budget in 1949, then move to increase it less than a year later? Particular international events also provide a weak basis for explaining the policy-making process. The events most often cited as prompting the development of NSC 68 especially the collapse of the Nationalist regime in China, the Soviet acquisition of the atomic bomb, and the beginning of the Korean War do not correspond chronologically to the policy developments they are supposed to explain.

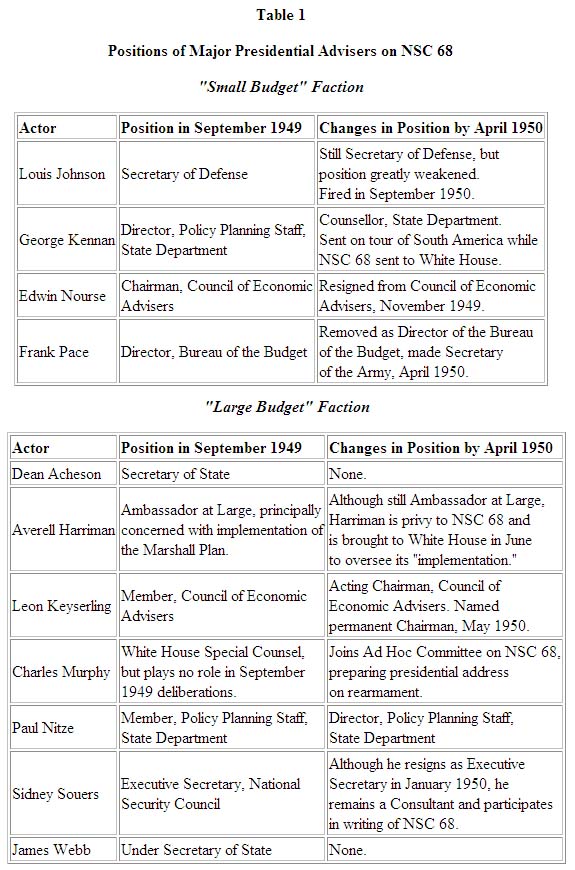

A consideration of the changing political circumstances within the administration between the fall of 1949 and the spring of 1950 suggests a better explanation. In the fall of 1949, the small budget faction held many key administration posts. Some, like Louis Johnson, had also played important roles in the president's 1948 re-election campaign. In the spring of 1950, the advocates of NSC 68 successfully changed the political composition of the administration, marginalizing those who had favored budget cuts in the fall and mobilizing politically important supporters of rearmament. The personnel shifts associated with this political change are summarized in Table 1. Although not all of these changes resulted directly from efforts by the advocates of NSC 68, they all contributed to a major shift in the internal composition of the Truman administration. Harry Truman heard very different voices in the spring of 1950 than he had in the fall of 1949.

The first important change came in November of 1949, when Edwin Nourse resigned as Chairman of the CEA, leaving Leon Keyserling as the acting chair. Keyserling had argued in favor of greater military spending during the debate over the fiscal 1951 defense budget in 1949. His conflict with Nourse over this issue led to Nourse's decision to resign.43 Keyserling's new status strengthened the coalition supporting NSC 68 within the executive branch. Truman's decision to make Keyserling's appointment permanent in May, after six months of hesitation, is yet another signal that the president had accepted NSC 68's call for greater spending.

Wells incorrectly treats the CEA as an opponent of NSC 68. In fact, Leon Keyserling helped promote the program, consistently maintaining that the US economy had the capacity to sustain larger expenditures on defense. Charles Murphy remarked that, in meetings of the Ad Hoc Committee on NSC 68,

[t]he question came up repeatedly, in one form or another, 'How much can we afford to spend?' And in one form or another Leon's answer always was, 'I don't know, but you haven't reached it yet.' He always said, 'You can afford to spend more on defense if you need to.'44

TABLE 1: Positions of Major Presidential Advisers on NSC 68

While the CEA's memo on NSC 68 expressed concern about the political viability of rearmament, it did not question the basic goals of NSC 68 or the principle of greater military spending. "Unless carefully and imaginatively prepared, their adoption could create concerns on the part of the Congress and the public which could ultimately threaten their success."45 The strongest advocates of NSC 68 were well aware of these problems and would certainly have agreed with this statement.

Acheson and others favoring greater spending took other steps to weaken their opponents in the executive branch. Acheson replaced George Kennan with Paul Nitze as head of the State Department's Policy Planning Staff in January 1950. During their 1949 discussions of the issue, Kennan and Nitze had disagreed over the amount of military spending required to contain the Soviet Union. Nitze had long favored a much larger program of aid and military spending. Kennan had argued that two or three Marine divisions would be enough to carry out the military aspects of containment, which he envisioned primarily as a political and diplomatic strategy rather than a military one.46 Acheson supported Nitze's position. Kennan may have been coming around to this point of view, but Acheson was not inclined to wait.47

Since none of its drafters had any reason to expect his support, Louis Johnson had not been kept fully informed on the developing new policy.48 The completed report was presented to him at a 22 March meeting with the working group that had written it. Predictably, Johnson was furious. He angrily accused the assembled group and Secretary of State Acheson of attempting to undermine his authority in a violent outburst that ended the meeting in less than fifteen minutes. When the incident was reported to Truman, he reportedly considered firing Johnson immediately.49 As Acheson had known before scheduling the ill-fated meeting, Johnson was about to leave for a NATO Defense Ministers' Conference in The Hague. In his absence, the report was distributed in the Department of Defense. Within a few days of Johnson's return, the report was on his desk with the approval of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and all three service Secretaries. Faced with a fait accompli, and having already embarrassed himself over the issue, Johnson signed the report and it was formally sent to the White House on 7 April 1950.

According to Paul Hammond's interview-based account, after Johnson met with the president when the National Security Council discussed NSC 68 in April, he told Defense Department officials privately "that his economy program was dead and that he had shaken hands with the President on it."50 Reflecting this change in the administration's plans, Johnson's 26 April testimony to Congress on the fiscal 1951 budget was extremely ambiguous on future plans for the defense budget, even implying that a buildup was possible.51

The State Department also successfully sought to have Frank Pace, the fiscally conservative Director of the Bureau of the Budget, replaced at the end of March, an event not mentioned in any of the accounts of NSC 68 cited here. Pace had been an outspoken advocate of reducing military spending, and had initiated the successful effort to reduce the fiscal 1951 defense budget from $15 billion to $13 billion in the summer of 1949. Circumstantial evidence suggests that Pace's removal was linked to NSC 68. According to interviews conducted by Hammond, Pace refused to change his opinion on military spending after reading NSC 68. "Reportedly, he quoted to Nitze Bureau of the Budget figures on how much the economy could stand in the way of Federal expenditures, and how necessary expenditures on other things besides foreign and military affairs were."52 Under Secretary of State James Webb asked the president to remove Pace from the Bureau of the Budget at the same 26 March meeting where he presented Truman with a copy of NSC 68, suggesting that he would be a good Secretary of the Army.53 The president agreed.

Pace's successor, Frederick Lawton, kept his distance from the debate over NSC 68, confining his attention to the administrative aspects of the policies set forth by the president and the rest of the administration. He did not attend the meetings of the Ad Hoc Committee on NSC 68. Instead, he assigned William Schaub, Deputy Chief of the Division of Estimates, to represent the Bureau of the Budget. Although Schaub objected vigorously to the enormous expenditures implied in the document, his comments appear to have had no effect on the committee, composed mostly of individuals with more standing in the policy-making arena.54 After Pace's removal, the Bureau of the Budget was a much less formidable barrier to rearmament.

While weakening the opponents of greater military spending, the supporters of NSC 68 sought to mobilize politically important individuals likely to support it. Harriman, who would later be brought to the White House to help implement the program, returned from Europe to express his support for the report at the 20 April NSC meeting.55 Other key internationalists were asked to review the report in March.56 Although all of them had suggestions and comments concerning the report, few changes were made in the final version sent to the president and the National Security Council. The purpose of the consultation process was the cultivation of sympathetic individuals who were in a position to influence public and elite opinion, not to rewrite the report. Several of the consultants recognized this purpose and called for further efforts to convince the public of the need for rearmament. Chester Barnard, President of the Rockefeller Foundation, suggested several people who could be included in a group to promote the program. Noting the need for "a much vaster propaganda machine to tell our story at home and abroad," Robert Lovett suggested a public relations campaign to enlist the aid of "schools, colleges, churches, and other groups." He also mentioned a list of "elder statesmen" similar to the one suggested by Barnard.57

While the president remained on vacation in Key West, Nitze and others sought to convince important but previously uninvolved White House staff members to support NSC 68. Charles Murphy, the President's Special Counsel, and George Elsey, who handled many foreign policy matters in the White House, were probably the first members of the staff to see the report. In his oral history interview, Murphy recalled being so impressed by it that he stayed home for a full day just to study it. The archival record supports Murphy's recollection of his conversion experience.58 On 5 April, Murphy and Elsey met with the State-Defense group that had written NSC 68. The meeting lasted nearly two hours and presumably allowed the group to go over the report in some detail. Murphy requested a meeting with the president immediately after Truman returned from Key West on 10 April. He recalled telling the president that the paper should be referred to the National Security Council and that Leon Keyserling should be brought in to participate in the discussion as acting Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers.59

Why should Truman have changed his views on policy simply because of the new balance of opinion in his administration? After all, the president's advisers serve at his pleasure and can be replaced if they refuse to accept his decisions.60 Furthermore, Harry Truman was perfectly capable of ridding himself of offending advisers, as cabinet officers from Henry Wallace to Louis Johnson discovered during his presidency. As former Truman White House staff member Richard Neustadt has recognized, however, the situation facing the president is more complicated than his legal authority implies.61 The president needs allies to be re-elected and to insure effective implementation of his policies. He cannot ignore the views of important members of his administration, particularly when they have the support of critical elements of his electoral coalition. In this case, despite his apparent preference for a balanced budget, Truman confronted political circumstances in the spring of 1950 in which the approval of NSC 68 had some clear advantages over his prior policy of fiscal restraint.

Rejecting NSC 68 would have created serious political problems. The advocates of rearmament had outmaneuvered their opponents in the executive branch. Potential opponents were either excluded from the process until it was too late for them to affect the outcome or brought into it under circumstances that tended to minimize their influence. By the time Louis Johnson signed the report and sent it to the White House, his position in the administration was extremely weak, and his allies in the Bureau of the Budget and the Council of Economic Advisers were gone. Furthermore, conservative White House staff members such as Matthew Connelly and Harry Vaughan, who might have sided with Louis Johnson, remained in Key West while the advocates of the new policy built support for it in the State and Defense Departments. Charles Murphy's backing was secured before the president returned from his vacation in Florida. Because of the political acumen of Acheson and Nitze, the president heard few dissenting voices on NSC 68. If Truman had rejected NSC 68, he would have been repudiating most of his economic and foreign policy advisers, as well as important members of his own staff. Truman might have done it anyway, of course, but the cost would have been high.

Even if those opposed to NSC 68 had been able to mobilize effectively, the president still had solid political reasons to prefer the more internationalist position. Truman had not yet decided whether he would seek another term as president in 1952. Even if he were not planning to run, though, the future of the Democratic party would probably still have been important to him. Major internationalists, including Averell Harriman, Robert Lovett, and others consulted during the development of NSC 68, already knew about the report and supported it. While most of these individuals and the international commercial and financial interests they represented had supported the president in 1948, Truman must have known that they could still switch their support to a Republican internationalist challenger in 1952. These internationally oriented interests were well represented in both parties, but were especially important to the Democrats.62 Indeed, Lovett himself was a Republican as was at least one other partner of Harriman's and Lovett's at Brown Brothers Harriman.63 A refusal to accept NSC 68 might have alienated this important element of the elite base of the Democratic party and threatened the coalition that had sustained it since the beginning of the New Deal.

While Truman might have reoriented the Democratic party toward the interests of the less internationalist segments of the political economy and rejected NSC 68, this option was fraught with political risks. If the president had been considering a third term in 1952, this policy choice would have strengthened Louis Johnson as a potential rival. Whatever Truman's plans and Johnson's role in them, these conservative interests were not a particularly reliable constituency for any Democratic presidential contender in 1952. If the Republicans were to nominate Robert Taft, as many expected in 1950, most conservatives would probably have supported him regardless of Truman's policy choices. Alternatively, as was noted above, if Truman rejected NSC 68 and the Republicans nominated an internationalist, an important Democratic constituency might defect. Even if Truman had been personally more comfortable with a different political arrangement, moving away from the highly successful New Deal formula linking liberal domestic policies with an internationalist foreign policy would have been very risky. In the end, probably hoping that Leon Keyserling's reassuring views on fiscal policy would prove correct, Truman sided with the authors of NSC 68.

The acceptance of NSC 68 within the administration, and the corresponding rejection of the prior plans to maintain a small military budget, were closely tied to changes in the composition of the group making policy. Policy changes as important as NSC 68 can occur without any clear change in the international environment. International events influence policy. However, the meaning of these events for policy depends on the identity and interests of the policy makers who interpret them.

CONCLUSION: THE IMPORTANCE OF DOMESTIC POLITICAL CONFLICT

This examination of the development of NSC 68 has sought to determine whether a state's decision-making apparatus can be treated as a unitary actor under circumstances generally considered very favorable to such an approach. Of course, it is obviously true that policy is not literally made by a unitary actor. The question here is whether analysts can reasonably abstract it as such in order to capture the considerable advantages of such a simplification, including concepts like the "national interest" and the treatment of external events as if they carried the same policy implications for all domestic actors. The case of NSC 68 suggests that the unitary actor assumption produces a very problematic account of the policy-making process, even on national security issues.

Although many accounts of the development of NSC 68 treat the US as a unitary actor responding to external events, these accounts face serious difficulties. The events Wells and others argue motivated the rearmament program were followed almost immediately by a decision to cut the size of the defense budget. By the time North Korean forces crossed the 38th parallel on 25 June, the decision to propose to Congress a rearmament program based on NSC 68 had already been made. Changes in the group making policy between the fall of 1949 and the spring of 1950 offer a better explanation for the decision to rearm. Advocates of fiscal restraint such as Frank Pace, Louis Johnson and Edwin Nourse, were no longer the dominant group within the administration. They were replaced by others more concerned with building a formidable military force in Europe and covering the dollar gap than with balancing the federal budget. This case suggests some tentative conclusion about the relationship between domestic political conflict, international conditions and policy change.

While events and conditions in the international system influence policy, there is no necessary connection between international conditions and foreign policy change. The linkage between the international system and policy is mediated by the divergent goals and priorities of different members of the group making policy. The international environment may influence policy by changing these actors' interests or beliefs or by altering their calculation of how best to achieve their goals. On the other hand, policy makers may simply understand events in a way that coincides with their prior interests and beliefs. Events do not interpret themselves, and it is unlikely that any particular one will have a single meaning for all concerned. In extreme circumstances, even something as catastrophic as a direct attack by a foreign army may be viewed as liberation by some and as an invasion by others. For those interested in the policy response to such an event, the question of who is in charge is at least as important as the question of what happened.

Even if there is consensus on goals, disagreement over relative policy priorities may be just as important. In 1949 and 1950, there was virtually no disagreement within the Truman administration about the goals of containing Soviet power and facilitating economic recovery in Western Europe. However, it was not possible to have rearmament on the scale imagined by the advocates of NSC 68 and fiscal restraint of the sort desired by its opponents. In this case, the trade-offs imposed by the cost of the new policy linked it to such substantively unrelated areas as fiscal policy. The dynamics of the process were shaped by actors' preferences on these other issues, as well as on national security policy itself.

Different perceptions of the meaning of events and the appropriate policy response are especially likely to be significant in cases of policy change. The decision to adopt a new policy will inevitably affect the priorities and interests of important political actors in different ways. Because it may disrupt the existing distribution of resources and political rewards both inside and outside the government, policy innovation may expose previously submerged conflicts among those affected by it. For a policy to be implemented, the conflicts among these actors must be resolved. In order for NSC 68 to become administration policy, those within the executive branch opposed to enlarging the military and foreign aid budgets first had to be either induced to reverse their position or removed from positions where they could interfere with the new policy. In this case, and probably in others as well, these changes in the policy-making group were not linked to international events.

An analysis of the foreign policy-making process should center on the beliefs and interests of the group controlling policy and its challengers, and the process by which conflict between them is resolved. An arrangement may evolve reconciling the contending interests, or one group may gain the upper hand and exclude the other from further influence over policy. International events may prompt policy change by changing the identity or interests of those who make policy. On the other hand, there need not be any change in the international system for policy change to occur. Even on national security issues, these dynamics may complicate the relationship between international conditions and policy outcomes in ways that make unitary actor models and associated concepts such as "the national interest" or "core values" inappropriate tools for understanding the policy-making process.

Benjamin Fordham is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University at Albany, State University of New York.

Endnotes

1. I would like to thank the following people for their comments and suggestions: Richard H.

Kohn, Timothy J. McKeown, Eric Mlyn, Gregory Nowell, Matthew Oyos, David Painter,

Mark Thompson, and two anonymous referees for The Journal of Conflict

Studies. The responsibility for any errors is mine.

Return to body of article

2. Foreign Relations of the United

States, 1950 (hereafter cited as FRUS) (Washington,

DC: Department of State, 1977), vol. I, pp. 262; 283-84. NSC 68 is on pages 235-92.

Return to body of article

3. See, for example, Fred Block, "Economic Instability and Military Strength: The Paradoxes

of the 1950 Rearmament Decision," Politics and

Society, 10, no. 1 (1980), pp. 35-58; John L. Gaddis,

Strategies of Containment (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), pp. 89-126;

and Robert A. Pollard, Economic Security and the Origins of the Cold

War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), pp. 222-42.

Return to body of article

4. The concept of "core values" is best explained in Melvyn Leffler, "National Security,"

in Michael J. Hogan and Thomas Patterson, Explaining the History of American Foreign

Relations (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991). The notion of the "national security

imperative" in historiography of the early Cold War era is from Howard Jones and Randall B.

Woods, "Origins of the Cold War in Europe and the Near East: Recent Historiography and the

National Security Imperative," Diplomatic

History, 17, no. 2 (Spring 1993), pp. 251-76.

Return to body of article

5. Leffler, "National Security." See also Leffler's "The American Conception of National

Security and the Beginnings of the Cold War, 1945-48,"

American Historical Review, 89, no. 2, pp.

346-81, for a discussion of the origins of the core values that drive Cold War foreign policy in

his account.

Return to body of article

6. The best known neorealist works are Robert Gilpin, War and Change in International Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981); and Kenneth Waltz, A Theory of International

Politics (Reading, PA: Addison-Wesley, 1979). Unitary actor models are also widely used

in game-theoretic accounts of international relations, such as Emerson M.S. Niou, Peter C.

Ordeshook and Gregory F. Rose, The Balance of

Power (New York: Cambridge University Press,

1989); George W. Downs and David M. Rocke, Tacit Bargaining, Arms Races, and Arms Control

(Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1990); and Bruce Bueno de Mesquita,

The War Trap (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981). The use of the unitary actor assumption is

not confined to the analysis of security issues, as Joanne Gowa,

Allies, Adversaries, and International

Trade (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994) indicates.

Return to body of article

7. The best-known historical works on the early Cold War stressing national security interests

is Gaddis, Strategies, and, most recently, Melvyn Leffler,

A Preponderance of Power (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992). Jones and Woods, "National Security

Imperative," reviews a wide range of other work that the authors contend represents a synthesis around

the primacy of national security interests. The responses to this essay, by Emily Rosenberg,

Anders Stephanson, and Barton Bernstein, dispute this argument. Leffler is the most outspoken

about the absence of a coherent policy alternative. See

Preponderance of Power, pp. 14-5, 138-40. In light of this interpretation, it is not surprising that Leffler's treatment of

Congressional opposition to the 1950 rearmament program is confined to a single sentence: "After

some wrangling, Congress gave the president the authority he requested." p. 371. See the

critique of Leffler offered by Lynn Eden, "The End of U.S. Cold War History?,"

International Security, 18, no. 1 (Summer 1993), pp. 174-207.

Return to body of article

8. This work includes the vast literature on the argument that democratic states do not fight

one another. See, for example, Bruce Russett, Controlling the

Sword (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), esp. pp. 119-45. It also includes theories using the distinction

between "status quo" and "revisionist" states as an explanatory variable. See Randall

Schweller, "Bandwagoning for Profit: Bringing the Revisionist State Back In,"

International Security, 19, no. 1 (Summer 1994), pp. 72-107. Jack Snyder,

Myths of Empire (Ithaca, NY: Cornell

University Press, 1991), which examines the impact of domestic coalition-building on international behavior.

Other notable works stressing conflict among different interests in the domestic political

economy include David Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World

Intervention (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1990); and Ronald Cox,

Power and Profits (Lexington, KY:

University of Kentucky Press, 1994).

Return to body of article

9. Outstanding examples among recent works examining the early Cold War era include

Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean

War, vol. 2 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press, 1990), esp. pp. 3-121; and Thomas J. McCormick,

America's Half-Century, 2nd ed. (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), esp. pp. 1-16.

Return to body of article

10. Samuel Wells, "Sounding the Tocsin: NSC 68 and the Soviet Threat,"

International Security, 4, no. 2 (Fall 1979), pp. 116-58; Leffler,

Preponderance of Power, pp. 312-60; Pollard,

Economic Security, pp. 222-42.

Return to body of article

11. Bueno de Mesquita, War

Trap, pp. 11-29; Downs and Rocke, Tacit

Bargaining, pp. 92-100. Bueno de Mesquita's subsequent work devotes much more attention to the implications

of domestic political divisions. See especially Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and David Lalman,

War and Reason (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992).

Return to body of article

12. Timothy J. McKeown, "The limitations of 'structural' theories of commercial policy,"

International Organization, 40, no. 1, pp. 43-64, points to several problems with theories using

"as if" assumptions instead of a defensible sense of process.

Return to body of article

13. Alexander George and Timothy J. McKeown, "Case Studies and Theories of

Organizational Decision Making," Advances in Information Processing in

Organizations, 2 (1985), p. 36. Gary King, Robert O. Keohane, and Sidney Verba,

Designing Social Inquiry (Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press, 1994), pp. 226-28, argue that process tracing actually redefines the

dependent variable in order to increase the number of observations. In either formulation, however,

the purpose of process tracing is to test the ability of a theory to account for a series of

actions by decision makers over time.

Return to body of article

14. George and McKeown, "Case Studies," p. 35.

Return to body of article

15. Wells, "Sounding the Tocsin," p. 117, also mentions the formation of the German

Democratic Republic. Leffler, Preponderance of

Power, pp. 312-44, includes the continuing

European balance of payments deficit with the United States. While he generally stresses economic

rather than national security interests, Pollard,

Economic Security, pp. 234-35, concurs in this

account of NSC 68, arguing that that these events caused a "subtle change in official thinking"

even though they did not influence military spending.

Return to body of article

16. Wells, "Sounding the Tocsin," p. 139, contends that "[h]ad war not intervened, there is

strong evidence that no major increase in defense spending would have won administration approval."

Pollard, Economic Security, p. 223, concurs that "[t]he Korean War was the true watershed

in Truman's defense policy." Leffler, Preponderance of

Power, pp. 358-59, down plays the importance of NSC 68 and argues that Truman would not allow an increase in military

spending before the Korean War.

Return to body of article

17. Paul Y. Hammond, "NSC 68: Prologue to Rearmament," in Warner R. Schilling, Paul Y.

Hammond, and Glenn Snyder, Strategy, Politics and Defense

Budgets (New York: Columbia University Press, 1962), pp. 280-82; and Steven L. Rearden,

History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Volume I: The Formative Years,

1947-1950 (Washington, DC: Historical Office,

Office of the Secretary of Defense, 1984), pp. 369-72.

Return to body of article

18. FRUS 1949, I, pp. 352-57; 385-98.

Return to body of article

19. CIA Special Evaluation Number 32, "Possible Collapse of Chinese National Government

Control," 21 July 1948, Declassified Documents Reference

System, 1990 Collection (Woodbridge, CT: Research Publications), Document 1259.

Return to body of article

20. Summary for the president of the discussion at the 33rd meeting of the National

Security Council, 4 February 49, President's Secretary's Files: NSC Meeting Summaries, Truman

Library.

Return to body of article

21. Quoted in Dean Acheson,

Present at the Creation (New York: W.W. Norton, 1969), p. 303.

Return to body of article

22. FRUS 1950, I, p. 161.

Return to body of article

23. Leffler, Preponderance of

Power, p. 326.

Return to body of article

24. The underlined quote reads "There has been as yet no indication that the general lines of

Soviet foreign policy have been altered by the possession of atomic secrets." State Department

Weekly Review, October 1949, White House Confidential File, Box 59, Truman Library.

Return to body of article

25. Paul H. Nitze, "The Development of NSC 68,"

International Security, 4, no. 4 (1980), p. 171.

Return to body of article

26. Keyserling and John D. Clark to Truman, 26 August 1949, Keyserling Papers, Box 3,

Truman Library. Underlining in original.

Return to body of article

27. FRUS 1949, I, pp. 394-96.

Return to body of article

28. Rearden, Formative

Years, p. 535, cites the diary of Frederick Lawton, the Director of the

Bureau of the Budget, for this remark.

Return to body of article

29. Acheson, Present at the

Creation, p. 378.

Return to body of article

30. Truman to James Lay, 12 April 1950, Minutes of the 55th Meeting of the National

Security Council, 20 April 1950, President's Secretary's Files, Box 207, Truman Library;

FRUS 1950, I, pp. 297-98.

Return to body of article

31. Souers memorandum for the file, 8 June 1950, Souers Papers, Box 1, Truman Library.

Return to body of article

32. The strongest statement of this claim is Robert Jervis, "The Impact of the Korean War on

the Cold War," Journal of Conflict

Resolution, 24, no. 4 (December 1980), pp. 563-92.

Return to body of article

33. These included Harvard President James Conant and former Under Secretary of State

and Harriman business partner Robert Lovett. FRUS

1950, I, pp. 196-200.

Return to body of article

34. Dulles to Acheson, 9 February 1950, Dulles Papers, Mudd Library, Princeton University, Box 47; Webb's account of his trip to Key West is found in the Joint Oral History Interview with Charles Murphy, Richard Neustadt, David Stowe, and James Webb, 20 February 1980, p. 65,

Truman Library. Concerning the Dulles appointment, see Acheson memorandum of

conversation with Truman, 4 April 1950; and Acheson memorandum of conversation with Dulles,

6 April 50, Acheson Papers, Box 65, Truman Library.

Return to body of article

35. David Kepley, The Collapse of the Middle

Way (New York: Greenwood, 1988), p. 82.

Bridges had suggested this arrangement to Jack McFall, Assistant Secretary of State for

Congressional Relations, arguing that Republicans on the Foreign Relations Committee did not really

represent their party. McFall memorandum of conversation with Styles Bridges, 21 February

1950, Record Group 59 (McFall), Box 1, National Archives.

Return to body of article

36. Acheson to Truman, 5 April 1950, Acheson Papers, Box 65, Truman Library.

Return to body of article

37. James Webb to Robert Taft, 27 April 1950, Taft Papers, Box 750, Library of Congress.

Return to body of article

38. Statement attached to invitation to 10 May 1950 smoker, Taft Papers, Box 750, Library

of Congress.

Return to body of article

39. Acheson memorandum of conversation with the president and Senator Tom Connally, 27

April 1950, Acheson Papers, Box 65, Truman Library.

Return to body of article

40. Styles Bridges was advised by his staff to stay away from these meetings since they

could damage his reputation. Dick Auerbach to Styles Bridges, 11 June 1950, Bridges Papers,

File 27, Folder 111, New Hampshire State Archives. Jack McFall was disappointed at the

Republican turnout for these events, although he attributed it to a scheduling conflict with a dinner

given by Styles Bridges. McFall to William Hall, 27 April 1950, Record Group 59 (McFall),

Box 1, National Archives.

Return to body of article

41. Handwritten list of "Top Musts" attached to the printed Summary of the Status of

Legislation Relating to the Recommendations of the President, 2 November 1949, Spingarn Papers,

Box 26; Urgent Legislation [a printed list], 31 May 1950, Spingarn Papers, Box 26, Truman Library.

Similar printed lists appear in the papers of other White House staff members, and

apparently served as the basis for discussion at meetings on legislative strategy. Leffler,

Preponderance of Power, p. 342, points out that these programs were of special concern to Robert Taft and

other conservative Congressional Republicans.

Return to body of article

42. FRUS 1950, I, p. 285.

Return to body of article

43. Edwin Nourse, Economics in the Public Service: Administrative Aspects of the Employment

Act (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1953), p. 283.

Return to body of article

44. Oral History Interview, Charles Murphy, 19 May 1970, p. 524, Truman Library. Paul

Nitze, "The Development of NSC 68," p. 173, also notes the support he received from Keyserling.

Return to body of article

45. Hamilton Q. Dearborn to James Lay, 5/8/50,

FRUS 1950, I, 306-11.

Return to body of article

46. Hammond, "Prologue to Rearmament," p. 310; Nitze, "Development of NSC 68," p. 171.

Return to body of article

47. Nitze, "Development of NSC 68," p. 172; Gaddis,

Strategies of Containment, p. 87; Cumings,

Origins of the Korean War, pp. 178, fn. 53.

Return to body of article

48. Hammond, "Prologue to Rearmament," p. 300; Paul Nitze,

From Hiroshima to Glasnost (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1989), p. 94, wrote that Johnson "knew virtually nothing of

our deliberations."

Return to body of article

49. Accounts of Johnson's outburst at the 22 March meeting vary in their details, but all agree

that his angry response to Nitze's reading of conclusions of NSC 68 brought the meeting to an

abrupt end. See Acheson, Present at the

Creation, p. 373; Nitze, From Hiroshima to

Glasnost, p. 95; Hammond, "Prologue to Rearmament," pp. 321-22. Contemporary accounts provide

substantially the same story. See FRUS

1950, I, pp. 203-06; Souers Memorandum for the Files,

Souers Papers, Box 1, Truman Library. Johnson's reaction to the report, while extreme, is

more understandable when one considers the implications of the report for his work on the

military budget, and the fact that he was not kept fully informed of progress on it.

Return to body of article

50. Hammond, "Prologue to Rearmament," p. 337.

Return to body of article

51. Ibid., pp. 338-40. In congressional testimony after the beginning of the Korean War, Johnson used his earlier statement to imply that he had never closed the door on a larger military budget.

Statement before the Senate Appropriations Committee, 25 July 1950, Johnson Papers, Box

145, Alderman Library, University of Virginia.

Return to body of article

52. Hammond, "Prologue to Rearmament," pp. 328-29.

Return to body of article

53. Joint Oral History Interview with Charles Murphy, Richard Neustadt, David Stowe, and

James Webb conducted by Anna Nelson and Hugh Heclo, 20 February 1980, p. 66, Truman Library.

Webb's account of this meeting was not contradicted by any of the others present at the

oral history interview, and is supported by the fact that he visited Key West and met with

Truman at precisely this time.

Return to body of article

54. FRUS 1950, I, pp. 298-306.

Return to body of article

55. Memorandum to the President summarizing the discussion at the 55th meeting of the NSC,

4/21/50, PSF, NSC Meeting Summaries, Truman Library.

Return to body of article

56. J. Robert Oppenheimer met with the group on 27 February 1950; James Conant, President

of Harvard University, on 2 March; Chester I. Barnard, President of the Rockefeller

Foundation, and Henry Smyth, a member of the Atomic Energy Commission, on 10 March; Robert

Lovett on 16 March; Ernest O. Lawrence, Director of the Radiation Laboratory at the University

of California, on 20 March. Nitze to Acheson, FRUS

1950, I, pp. 202-3.

Return to body of article

57. Record of the Meeting of the State-Defense Policy Review Group, 3/16/50,

FRUS 1950, I, pp. 196-200. Lovett, a partner in the investment banking firm of Brown Brothers Harriman,

brought up the need to increase American imports from Europe to reduce the balance of

payments surplus.

Return to body of article

58. His calendar for 31 March 1950, contains a handwritten note stating: "4:30 James Lay-has

paper he wants to bring over this afternoon-in at 6:00 p.m." As Murphy comments in his oral

history interview, he does not appear to have received or read the document immediately, but the

events which followed his reading of it fit the other elements of his story. On Monday, 3 April a

note reads: "James LayMr. Farley brot [sic] papers. CSM wants to read papers, GME

[George Elsey] to read also. Nitze Lay at meeting." A note written the next day corroborates

Murphy's claim that he stayed home to consider NSC 68. "9:15-CSM called-will stay home today."

Murphy Daily Record of Telephone Calls and Appointments, March and April 1950,

Murphy Papers, Box 16, Truman Library; Murphy Oral History Interview, 25 May 1970, pp.

521-22, Truman Library.

Return to body of article

59. Murphy Daily Record of Telephone Calls and Appointments, April 1950, Murphy Papers,

Box 16, Truman Library; Murphy Oral History Interview, 25 May 1970, pp. 523-24, Truman Library.

Return to body of article

60. The strong position of the president has been used to justify use of the unitary actor

model, as in Bueno de Mesquita War Trap, pp. 27-28; Stephen Krasner, "Are Bureaucracies

Important? (Or Allison Wonderland)," Foreign

Policy, 7 (1972), pp. 159-79; and Robert J. Art,

"Bureaucratic Politics and American Foreign Policy: A Critique,"

Policy Sciences, 4 (1973), pp. 467-90.

Return to body of article

61. Richard Neustadt, Presidential Power: The Politics of Leadership from FDR to

Carter (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1980), p. 25, comments that "Truman was quite right when

he declared that presidential power is the power to persuade."

Return to body of article

62. For examinations of the critical role of the international financial sector in the New

Deal coalition, see Thomas Ferguson, "From Normalcy to New Deal: industrial structure,

party competition, and American public policy in the Great Depression,"

International Organization, 38 (1984), pp. 59-85; and Jeffry A. Frieden, "Sectoral conflict and foreign economic

policy, 1914-1940," International

Organization, 42 (1988), pp. 59-90.

Return to body of article

63. The other partner was Prescott Bush, the father of former President George Bush, who ran for Senator from Connecticut as a Republican in 1950.