by Steve A. Yetiv and Tom Lansford

INTRODUCTION

At a conceptual level, this article explores the relationship between developments and actions at the global and regional levels of analysis. To ask whether events at the global level affect the regional level more than vice versa is fruitless because they affect each other at different degrees. The more interesting question hinges on how and why they do so in any particular context.

Partly in order to explore that issue, this article addresses the following questions: how have US-Russian relations changed in Southwest Asia as a result of the fall of the USSR? what is the nature of US and Russian involvement in the region? what is the relationship between their interaction at the global level and their actions and standing in the Persian Gulf region?

These questions are of obvious importance. The end of the Cold War has not made US-Russian involvement and interaction in the Third World irrelevant. Rather, by transforming relations at the global level, it has altered realities at the regional level and vice versa. Understanding and explaining US-Russian relations is particularly important given the changing global and regional landscape in which they now take place. Russia remains an important, although disjointed, state in world politics with ongoing, evolving interests in various areas of the Third World. For its part, the Persian Gulf is likely to remain critical to the functioning of the entire global economy well into the twenty-first century.1

While the future of US-Russian relations in any Third World context will depend on many factors, including power struggles in Moscow and Washington, and the nature of the particular Third World context, several arguments about these relations seem sensible at present regarding Southwest Asia.

First, despite the fall of the USSR and Russias serious internal problems, Russia undoubtedly remains interested in enhancing its position in the Gulf region. While its foreign policy establishment appears divided on a range of issues, Russia nonetheless has sought seriously to develop political, military and economic ties to Iran and Arab Gulf states.2 Moreover, although US-Russian relations are on a more cooperative footing in some areas of interaction, important elements in the Russian government remain inclined to view US-Russian interaction as a power struggle in which Moscow at times needs to check the United States.

Second, while the decline of the Soviet Union hurt Moscows position in the broader Middle East, in some ways, it improved its economic and political position in the Persian Gulf. In the 1970s and 1980s, Moscows position was handicapped by its global ideology, menacing military reputation, atheistic propensities, and poor record in dealing with the Muslim world. This was demonstrated most clearly in its 1979 invasion of next-door Afghanistan.3 While the end of the Cold War did not altogether decrease the importance of these factors, it diminished them as impediments to Russian relations with regional states. As this article seeks to show, Russia has made strides in the areas of diplomatic contact and trade, although its arms sales efforts have suffered seriously since the end of the 1991 Gulf war.

Third, while the US and Russia remain competitive at the regional level in some areas of interaction, Russia is constrained by its preoccupation with internal instability and economic problems, and by its evolving, more cooperative relations with the United States at the global level. Moscows reluctance to disrupt this cooperation, and to lose the economic and political benefits that may arise from it, circumscribes just how far it will challenge Washington in a Third World arena like Southwest Asia.

Fourth, the changing context of global affairs and of US-Russian interaction, requires an adjustment in theory as it pertains to conceptualizing these relations. At the theoretical level, we advance the argument in the conclusion of this article that the realist model remains relevant in explaining the US and Russian role and interaction at both the regional and international level. However, partly as a result of the end of the Cold War, the liberal model and its various sub-schools of thought are assuming greater relevance as guides to their interaction at the global level.

Conceptualizing The Micro-Macro Link

The theoretical literature in international relations increasingly recognizes the importance of considering the relationship between areas of interaction that are often treated as separate but are in fact linked. Despite the fact that they represent different theoretical traditions, both neorealists, such as Joseph Grieco, and neoliberalists and their associated thinkers, such as Robert Keohane, urge greater efforts to forge theoretical links between domestic- and international-level variables.4

For his part, Robert Putnam develops a conceptual framework for understanding how diplomacy and domestic politics interact, thus accounting for how these two levels affect the decision-making of leaders.5 In this genre, Steven David argues that we cannot understand the balancing efforts of Third World nations without recognizing that their action is driven partly by concerns about maintaining their own power, position and prestige at home.6 Preceding these efforts are a series of works in the literatures of interdependence, regional integration, foreign policy analysis, and Third World politics that also explore the domestic-international link.7

The notion of how the micro- and macro- levels are related can assume many forms in various contexts and issue areas. In the works discussed above, it is manifested in terms of domestic-international links. In this article the relationship explored is between the global and regional levels. These levels are not viewed here as static but, rather, as dynamic, evolving structures, constantly revising themselves and their relation to each other in response to change and perceptions of change.

Analyzing "global" and "regional" as two levels of analysis raises the prior question of the extent to which we can we really distinguish them conceptually. Part of our argument is that, while these levels are different in some ways, distinguishing between them appears to be getting harder given the end of the Cold War and global change. Indeed, while some debate ensues on the issue, much evidence suggests that interconnectedness and interdependence has risen in the twentieth century and continues to rise, albeit faster in the developed world than in the Third World.8 As a result, understanding and explaining the behavior of nations at the global level increasingly requires study of events and factors at the regional level and vice versa.

At the same time, however, basic conceptual differences, while increasingly fuzzy, do exist between the two levels. As Barry Buzan has put it, regions are different from the "seamless web of relationships that connects all of the states in the international system."9 Four differences are worthwhile pointing out.

First, the term "global" often refers to the behavior, actions, and interaction of major powers, such as Russia, the US, China, France and Britain, particularly when it concerns international issues that cross-cut regions. We rarely refer to the actions of weaker states as part of the global level of analysis. "Global" and "regional" thus can be distinguished, to some extent, by the influence and position of the actors that comprise them.

Second, the global level may be distinguished by its processes. The changing distribution of power, the pace and impact of technological change, or the development of an open, international economy represent such processes. While technological change, for instance, occurs in the Third World as well, it often does so at a different pace and intensity than at the global level. Similarly, the distribution of power assumes different dimensions at both levels in terms of the actors that comprise it and their capabilities. It is hardly profound to note that the world can be multipolar at the global level, while any region might be unipolar or bipolar, or vice versa. While the distribution of capabilities at the regional and global levels are often linked, they are also different in their own right.

Third, at the global level, different issues are sometimes emphasized than at the regional level. Transnational issues, such as global warming, over-population, and international economic problems, are often treated as "global" rather than just as regional issues. Increasingly, they are cross-regional problems that require multilateral cooperation to ameliorate or solve.

Fourth, the parameters of the two levels of analysis are different. In addition to geography, some scholars believe that regions can be delimited partly by ideology, religion, ethnic, or common economic considerations. The evolving literature on regionalism or regional blocs argues this point.10 The global level, by contrast, is harder to delimit.

US and Russian Involvement In The Persian Gulf (1991-96)

In order to examine the central questions of this article and to establish its main arguments, we explore four areas of US-Russian interaction in the Persian Gulf from 1991 to 1996, which provide some insight into the changing position and rivalry of these two states: arms trade, military presence, economic ties to regional states, and diplomatic standing. After analyzing the empirical record in these areas, we then move ahead to discuss how Russias need for US cooperation at the global level is restricting its actions at the regional level. The article concludes with some general points of departure as well as a discussion of the relationship between the present empirical work and theory.

US-Russian Arms Trade in a Third World Context

Great powers have always sought position in the Third World, sometimes at the expense of local actors. The notion of the "New World Order" trumpeted by the Bush administration during and after the Persian Gulf crisis (1990-91) held out prospects for changing the nature of interaction between the global and regional level. Increased emphasis on cooperation, greater efforts at collective security, more reliance on the UN, and downplaying the use of force were aspects of this approach, as was a decreased emphasis on arms sales from such major exporters as the United States, France, Russia, China and Britain.

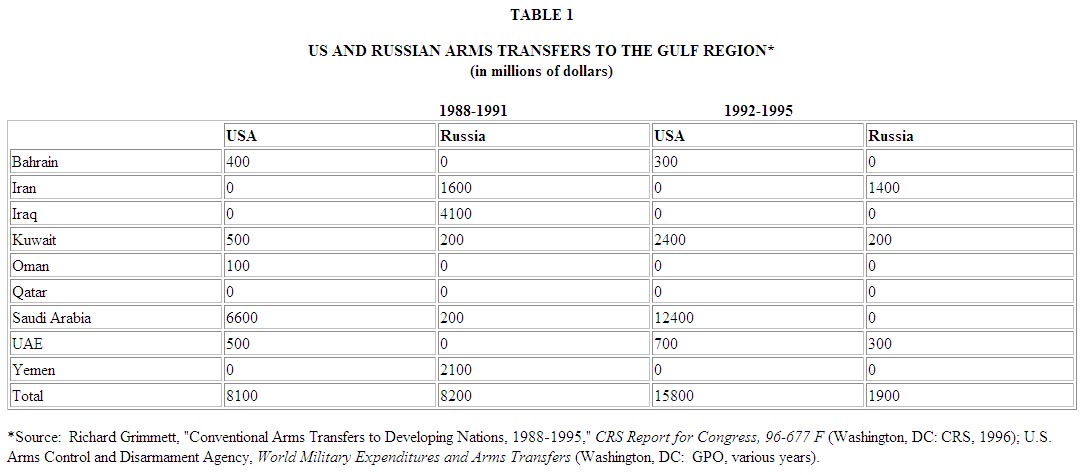

In the latter category at least, not much has changed. The United States and Russia have historically used arms sales and arms transfers to build influence in the Middle East and Third World, and this remains a serious issue to examine in the post-Soviet era. While the US has clearly and significantly superseded Moscow as the leading arms supplier to the region in the 1990s (see Table 1), Russia has made important strides with Iran and has the potential to re-establish its position, despite the fall of the USSR.

For Russia, arms sales have been and continue to be particularly important for three reasons. First, it lacks hard currency, and the relatively rich Gulf states are the worlds greatest arms market. Second, Moscow believes that it needs to preserve its massive defense industry,11 and that yielding the arms export market to the US and other states could put Russian national security in some jeopardy in the long-term. Third, Russia has been excluded from regional security frameworks. Indeed, Washington downplayed an arms-for-influence approach in the 1980s, noting that arms races lead to war, while recognizing that this was the USSRs "primary, if not only means of acquiring influence."12

In the 1980s, Moscow had difficulty translating arms sales into influence over regional developments. Gulf states were at least as angered by arms sales to their opponents as they were appreciative of receiving arms from Moscow.13 In the 1990s, Moscow faces some relatively new, although perhaps short-term problems. The United States is resurgent, bolstered by the Gulf war military victory, and Iraq, Moscows erstwhile ally, remains an international pariah. Moreover, Russias desire to maintain a good footing with the US, as elaborated upon later in this article, remains a constraint on how far it can push its arms sales strategy.

At the same time, the end of the Cold War, and US dual containment policy, which aims to contain Iran and Iraq simultaneously, has created some new opportunities for Moscow. It has made serious strides in arms sales to Iran, and generated some sales to the smaller Arab Gulf states. When economic sanctions are lifted on Iraq, that huge market will also open once again for Russian arms sales. Indeed, given Iraqs geographic position amid multiple adversaries, any Iraqi regime will likely use oil profits for rearmament.

While dual containment is in some ways benefitting Moscow in terms of arms sales, the US itself remains the main stumbling block to Moscows ability to dominate the regional arms market. It has long been a major, and often the dominant, supplier of weapons to the region. This trend has continued and even accelerated under the Clinton administration. Presidential Decision Directive 34 (PDD 34) makes it clear that the current administration "views conventional arms transfers to be a legitimate instrument of United States foreign policy.".14 Concrete steps have been taken to promote US arms sales, including the establishment of an "Advocacy Center" in the Commerce Department to champion US arms exporters and the waiving of fees in many government-to-government sales.

In the post-Soviet period, the United States has become the largest single exporter of arms to the region (see Table 1). While the Russians were the dominant arms supplier from 1988 to 1991 (providing some 23.8 percent of the Middle Easts weapons), since 1992, US arms sales have accounted for 48.5 percent of the total market.15 Several factors have contributedto this development. While the end of the Cold War has opened markets to Russia that before were closed for strategic and ideological reasons, the Gulf War and the ensuing embargo against Iraq has virtually shut down Moscows most lucrative regional market. On the US side, the Clinton administrations advocacy efforts, and the high performance of US versus Russian equipment during the 1991 Persian Gulf War, has boosted US export efforts.

Despite the overall US success in capturing markets, both Moscow and Washington, unlike Western European states, have concentrated on particular markets. In the Gulf region, the US has focused on Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, while Russia has dealt primarily with Iran, Iraq and Yemen. Recent large US military deals with Saudi Arabia include the sale of 315 M1A2 Abrams main battle tanks (MBTs) which are very slowly being integrated into the Saudi military structure, 400 M2A2 Bradley infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs), and 72 F-15 fighters. In overall terms, the United States has supplied some 60 percent of Saudi Arabias $30 billion worth of arms sales since 1991.

The United States struck lucrative deals in other states as well, including the sale of 218 M1A2s and 5 Patriot missile batteries to Kuwait, and the sale of retired M-60A3 MBTs to Bahrain and Oman. However, US restrictions on the transfer of high-technology systems has precluded some potential sales, most notably 16 UH-60L attack helicopters to Kuwait and M1A2 MBTs to the United Arab Emirates (UAE).16

Just as the US has reaped significant export profits from its Saudi connection, Russias arms sales and transfers to Iran have proved quite lucrative. It is now Irans biggest arms supplier. As a result of Irans military degradation during the Iran-Iraq war and its inability to purchase modern Western equipment, Tehran has turned to Russia for new weapons systems in a number of areas, including air defense, communications systems and surface-to-air missile systems.17

In a $10 billion arms-for-oil deal, Russia agreed to supply Iran with MiG-29 fighters, Su-24 fighter-bombers and SA-5 Surface-to-Air-Missiles (SAMs),18 and Russia has aided Iran in integrating into its air force the 122 Iraqi aircraft that Iran acquired during the Gulf War.19 In 1992, Russia began supplying Iran with T-72 MBTs and both IFVs and Armored Personal Carriers (APCs).20 In one of the latest collaboration efforts, Moscow has licensed Iran to begin indigenous production of variations of the T-72 MBT (to be known as the Zulfiqar) and an APC (to be known as the Boraq). Furthermore, Iran became the first Gulf state with submarine capability through its purchase of three Russian Kilo-class submarines whose crews are Russian trained. Moreover, Russian firms are supplying Iran with support for its long-range missile program. Although it is unclear to what extent this is officially sanctioned, such a green light would be hardly surprising.

Russias arms link with Iran has yielded it some influence with Arab Gulf states who would prefer that Russia delimit its efforts. For instance, after its submarine sale to Iran, Russia negotiated an agreement with the UAE in January 1993 that allowed its naval vessels maintenance rights in UAE ports in exchange for pledges to help protect Gulf shipping if necessary.21 Hence, its ships now have a new port in the Gulf, which Russia appears eager to exploit. Moscow also has concluded a bilateral security agreement with Kuwait that covers arms exports and equipment training.22

The Russian focus on arms sales to Iran, over serious US objections, results to some extent from an ongoing desire to jockey for regional influence and to check US power. Partly because it seeks independence from and bargaining leverage with the West,23 Russia strongly resisted repeated US efforts of prevent its sale of submarines and two light nuclear reactors to Iran. The effort worked. The sales did not go far enough to rupture US-Russian relations at the global level, and yet strengthened Russian links to Iran which Moscow sees as a pivotal regional actor. As President Boris Yeltsins chief advisor put it, "Iran can be a good and strategic ally of Russia at the global level to check the hegemony of third parties and keep the balance of power."24

Clearly, both Iran and Russia, and Iraq for that matter, would benefit from a weakened US role in the region. This creates both a tacit and explicit set of common interests that facilitate mutual relations. While at present this commonality of interests is not particularly threatening to Washington, it could assume such dimensions in the future as a result of unforeseen political or military events or gradual shifts in the balance of power.

Beyond its strategic machinations, Russia is also driven fundamentally by economics. Russian arms sales to Iraq dropped from some $4.1 billion from 1988-91 to near zero at the official level as a result of the Gulf War and the resulting economic embargo; in Yemen, the end of the Cold War caused a $2.1 billion drop from 1988-91 to zero, thereafter, partially as a result of the 1994 civil war. And, in Iran, Russia has faced increasing competition from China and former Eastern bloc states. In response, it has embarked on an aggressive campaign to gain access to markets traditionally closed to it by the Cold War, in order to compete more effectively with its transAtlantic rivals.

In 1993, Moscow combined the three bodies that had traditionally overseen its arms trade into a single entity Rosvooruzhenie. The new state-owned import-export company has offices in 38 countries and commercial contacts with 60.25 The Russians have had some success in diversifying their export market (their worldwide arms exports have rebounded since 1993) because their arms cost less than those of other states such as the US.26 In one prominent sale, the UAE chose to buy some 330 Russian BMP-3 IFVs over the US M2A1 Bradley because of the higher per unit cost of the US vehicle.27 In addition, Russia has sold artillery to Oman, the UAE and Yemen and has secured contracts to supply IFVs to the UAE, and to sell 30 SA-18 SAMs to Kuwait. Overall, however, Russian arms exports to the region remain concentrated on Iran.

Nonetheless, by once again becoming the principal supplier of arms to the developing world in 1995, Russia has demonstrated that it has overcome some of the problems in both production and quality that plagued the nations defense-industrial complex at the end of the Cold War. Regarding the Persian Gulf, Russia is likely to remain a major arms supplier for the immediate future,28 and to use arms sales as a potential influence-building instrument in the region.

Military Presence and Power in Transition

While Moscows ability to use arms sales for influence has improved in the 1990s, the opposite is true of its military. By contrast, the US-led defeat of Iraq in the Persian Gulf War has elevated significantly Washingtons status in this regard. While the US is constrained by competition from European and other states, by indigenous opposition to close ties to the US, and by the enduring difficulties of translating military capability into political influence, its demonstrable and unique ability to enforce the regional status quo against major aggressors allows it to exert influence in the region at particular junctures.

During the 1980s, Moscows regional presence was minimal compared to that of Washington. It stood to gain more from US policy failures in the region than from any unlikely efforts to insinuate itself militarily in the region. The United States built influence more than did Moscow by direct intervention. This allowed Moscow to paint Washington as an imperialistic state bent on hegemony at the expense of regional states.

In the post-Soviet era, Moscow has downplayed such rhetoric, although various officials still assail US foreign interference in regional affairs as unacceptable, pointing to such instances as the September 1996 missile attack on Iraq.29 Moreover, Russia has sought to expand its own position. In the post-Gulf War period, it signed an unprecedented defense accord with Kuwait, aimed at deterring further aggression through defense cooperation, training and exercises, and arms sales. While US influence in Kuwait dwarfs that of Moscow, and while Kuwait seeks to downplay this connection in American circles,30 the accord was not altogether insignificant. Russia does not pose a direct threat to US regional interests in the near term, but if the political-security environment changes significantly, contacts with regional states could rebound to Moscows favor, if only for purposes of political leverage.

The US, however, remains pre-eminent as an outside military power. Despite reductions in the total number of US forces since the Gulf War, Washington maintains considerable over the horizon and in theater capabilities. As a result of the 1991 Gulf War, the US naval presence has increased substantially and is now referred to as the US Fifth Fleet. It usually includes one aircraft carrier battle group nearby, and, depending on the potential for crisis, a variety of other naval combatants. On the ground, the US presence has also been enhanced since 1991. After the war, the US-Kuwait Defense Cooperation Agreement was signed in September 1991, and provided for US access to Kuwaiti military facilities, prepositioning of defense material for US forces, and joint exercises and training. While the agreement did not mandate automatic US protection of Kuwait, it raised strategic relations to a level unimaginable prior to Desert Storm. Washington also updated its access agreement with Oman and Bahrain, and signed a 20 year defense cooperation agreement with Qatar on 23 June 1992, which also allowed American access and prepositioning.31

The United States has prepositioned equipment in Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, and has stationed air units and a Patriot battalion in Saudi Arabia.32 In addition, it has some form of military access agreement or defense pact with most of the Gulf states (except Iran, Iraq, Oman and Yemen). US airpower has also been enhanced. Operation Southern Watch, which enforces the no-fly zone over southern Iraq, represents the largest combined operating force in the US Air Force. This force can be easily enhanced by US aircraft within 24 hours flying distance from the region. Moreover, Washington maintains air expeditionary forces for quick response in various states near potential loci of conflict.

While the US military presence has been enhanced by the Gulf War, Russias has decreased in the post-Soviet era. Moscow has removed thousands of military advisers from the Middle East, downgraded ties to Syria, Libya and Iraq, and virtually lost its position in Yemen and the Horn of Africa. To be sure, Russia does maintain a military presence on the regions periphery. Russian advisors still train Syrian troops and Moscow maintains a large troop deployment in and around the central Asian states, including sizeable deployments in Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Tajikistan.33

However, this capability cannot easily, if at all, be translated into direct influence within the Gulf region. Russias ability to influence Gulf states by threat or use of force was highly limited in the 1980s. It has decreased in the past six years, because of the impact of the fall of the Soviet Union and the rise of US military standing and credibility after the Gulf War. While Gulf state leaders did have to factor into their calculations the presence of Soviet forces on the periphery of the Gulf during the Cold War, they are far less concerned about it now, barring any major shifts in leadership in Moscow.

By contrast, regional states are acutely sensitive to and aware of US military capability. That Washington will be the principal enforcer of the regional status quo into the next century is well recognized in many Arab capitals,34 and this can yield Washington some influence over Moscow and European states across a range of non-military issues.

Economic Ties in the Middle East: Globalizing the Market

While Russia is unlikely to translate its military capabilities into influence in the region, it is positioning itself for economic gains with some modest success. Its economic ties with Gulf states are proliferating in potentially significant ways. Washington and European states, however, still remain far ahead in the economic arena, with the exception of Russian inroads with Iran.

The economic profiles of outside states in the region have changed in important ways in the past 25 years, pointing to a greater internationalization of the regional market. Until the 1970s, the US was the largest single exporter of goods to the Middle East. However, by 1980, Japan had eclipsed it, with Germany, France, the United Kingdom and Italy rounding out the top seven positions.35 During the 1980s, the US steadily lost its market share to the European Union (EU) nations which managed to increase their exports to the region by an average of 3.5 percent a year.36 As a result of its dual containment policy, the US has suspended all trade with Iran and Iraq. Indeed, Clinton dramatically expanded existing US sanctions against Iran by banning all US trade and investment with it and penalizing foreign companies that trade significantly with Iran.37 Whether or not recent efforts by both the US and Iran to seek a rapprochement succeed remains to be seen, and in any event will develop slowly, if at all.

The EU, for its part, has made significant economic progress in the Middle East in part because it has focused more on the concept of regional integration and a broad-based economic strategy. It seeks to penetrate the region as a whole, and has not let political or strategic imperatives derail its approach. By contrast, the United States has concentrated primarily on its links to Saudi Arabia, and has altogether excluded Iran and Iraq and focused less attention on the smaller Gulf states.

For its part, Russia seeks to emulate the EU approach in order to enhance its economic foothold. Russia signed limited contracts with firms in Bahrain and the UAE that cover a range of projects from sea transportation to the production of chemical fertilizers.38 In terms of oil development and policy, it aims to coordinate policies with the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in order to stabilize world oil prices.39 Moreover, it has looked to the Gulf states for both monetary and technical support in developing new oil fields within the Federation. Several Gulf states (Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia and the UAE) have underwritten over $2 billion of Moscows foreign debt,40 and Middle East states accounted for some five percent of the total foreign investment in Russia in 1993, a figure that has steadily grown.41

A UAE company, Gulf Russia, is developing oil fields in southern Russias Stavropol area,.42 and Russia, Oman and Kazakhstan have agreed to develop a pipeline from Kazakhstan.43 In addition, Russia and Iraq have agreed to allow Russian companies to rebuild and repair the heavily damaged Rumaila and Qurna oil fields as soon as UN sanctions are eased (the Russians assert that these fields can produce some 1.2 million barrels per day).44 As far back as 1994, Iraq signed a trade agreement with Russia worth some $10 billion to take effect when sanctions are dropped. The potential profitability of this agreement is one reason Russia is pushing the UN to lift economic sanctions on Iraq. Indeed, Iraq pledged not only to give Russian firms priority in the sale and delivery of goods and services worth some $10 billion, but also to make its repayment of $7 billion debt to Russia "a top-priority."45

For their part, Russia and Iran are developing joint oil exploration projects in the Caspian Sea region.46 Irans oil ministry and Russias energy monopoly, Gazprom, signed oil and natural gas agreements which would allow Gazprom to invest directly in Iranian oil/gas fields and provide transportation of Iranian oil/gas through the Persian Gulf.47 They have also worked to prevent the US and other states from penetrating the region. Both states, for instance, object to Western plans to build pipelines that would bypass them,48 and for strategic and economic reasons, seek some control over pipeline delivered oil. This commonality of interests was evidenced when Iran supported Moscows attempts to grant itself veto power over future oil projects in the Caspian region, and to extend Russias offshore economic zone some 45 miles into the Caspian Sea.49 Russia is also clearly eager to exploit problems in Irans relations with Washington and Europe, and must be unnerved by the potential improvement in US-Iranian relations. In April 1997, after a German court blamed Iran for ordering the assassination of exiled dissidents in Berlin, Russia vowed to strengthen ties to Iran. The European Union and the US backed Germanys move, while Boris Yeltsin and Gennadi Seleznyov, the Communist speaker of the Russian parliament, displayed unusual cooperation in hosting a high-profile visit by the head of Irans parliament, Ali Akbar Nateq-Noori.50 Since Germany is Irans largest trading partner, Russias support of Iran held out the prospect for economic gains.

On the whole, while Russia has made some economic gains in the post-Soviet era, several factors limit its success. First, it is seeking greater cooperation on oil issues from Gulf states as one plank of its attempt to develop economic influence. However, the stagnant world oil market has caused OPEC and Gulf states to view Russia more as a potential economic rival, in terms of oil exports, than as a partner. This is especially true regarding competition for foreign capital to develop new oil fields.51

Second, Moscows economic potential, like its arms sales, are also limited primarily to Iran, and even in Iran, its economic position is dwarfed by that of Germany, France and Great Britain. Germany, for instance, currently has a trade surplus of some $1 billion per year with Iran. In contrast, without military sales, the total volume of trade between Russia and Iran was $520 million in 1994. Moscow, however, predicts that within a decade, trade between the two states could grow dramatically once the issue of unpaid debts is settled.52

Third, during the Cold War, Russia used monetary inducements or military support to influence Arab states. But, in the post-Soviet era, it cannot as easily use material incentives for influence-building purposes. Rather, any financial resources must be husbanded for domestic purposes.

US dual containment policy, the 1989 Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, and the fall of the Soviet Union, however, have improved Russian prospects in Iran. In February 1995, Russia and Iran agreed to develop jointly a desalination plant for Iran. A January 1996 interbank agreement between the two states settled outstanding financial obligations; Moscow now predicts that by the next century annual exports to Iran may reach $4.5 billion.53

The desalination plant was part of a larger agreement that has significant implications for the region the sale of two light-water nuclear reactors to Iran. On 8 January 1995, Russia agreed to supply Iran with a 1,200 mega-watt and an 800 mega-watt power reactors and to provide research and scientific data for Irans universities. In exchange, Iran agreed to pay Russia some $800 million. Despite US intelligence data, which indicated that Iran was already engaged in a nuclear weapons program and that these reactors would quicken its pace, and despite intense pressure from President Clinton during the Moscow Summit of May 1995, Russian President Yeltsin adamantly refused to halt the sale. Russia has maintained that Iran complies with all of the provisions of International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and that all spent fuel would be open to IAEA inspection. Moreover, it has defended the agreement as purely commercial and charged the US with attempting to limit Russias ability to export technology. Moscow pointed to the US decision to sell the same type of reactors to North Korea as evidence of US obstructionism. While Russia is unwilling to undermine relations with the US over the issue of Iran, it appears willing to push its interests to the brink.

Diplomatic Presence: Russia Has Made Strides

The economic position and overall influence of both states is related to their diplomatic standing, status and access in the region. Improved political relations allow both states to jockey for influence on a range of other issues.

For its part, Russia has made significant strides in the 1990s in advancing it diplomatic position in the region, which not only serves its goals in the region, but also beyond it. Indeed, Moscow seems to be gambling that improved relations with Iran and the conservative Gulf states, as well as Turkey, may provide the leverage necessary to forestall future instability in the Federation. This may result from an outgrowth of Islamic fundamentalism among Russias 40 million Muslims or among the Muslim states of Central Asia, an especially important concern given Russias support of the Serbs in the Bosnian conflict. To this diplomatic end, Russia has embarked on a multifaceted effort to improve its relations with the Gulf states.

A better position in the Persian Gulf can facilitate Moscows economic and political efforts in the North Caucasus, Transcaucasia, and Central Asia, its competition with Iran and Turkey in these areas, and its effort to assert its historic interest on its own border areas. Moscow can more effectively compete economically in its own backyard if it has better relations with Gulf states, enmeshed in their own rivalries in the same area. Even before the end of the Cold War, the USSR was eager to improve relations with the Gulf monarchies, an effort which Russia has continued. By the late 1980s, it established diplomatic relations with Oman, Qatar and the UAE, and during the 1987 "tanker war" leased Kuwait three tankers. However, despite these gains, Moscow, as aptly described by the Gulf Cooperation Councils Secretary General Bisharah, was viewed as out of step with Gulf states in the 1980s.54 It was constrained by its global ideology, menacing military reputation, and dubious intervention in Afghanistan.

Indeed, Iran repeatedly condemned the Soviet attempt to "crush the brave resistance"55 of the Afghan rebels; Irans ambassador to the USSR made it clear that the Soviets actions in Afghanistan had "deadlocked their policies in Muslim countries" and had provided Washington with "an excuse to increase its influence in their region.".56 It was recognized in Pravda that Iran used the Afghan issue "more often than any other pretext to justify hostile attacks . . . on the USSRs interests."57 Despite improving relations, the Afghanistan issue came up at almost every Soviet-Iranian official meeting through 1989.58

After the Afghanistan withdrawal, a series of unprecedented high-level official visits took place, touching off a flurry of inter-state interaction. By 1991, Moscow became Irans leading arms supplier after having been virtually closed out of the market, at least since 1982.59 The emphasis placed on Russo-Iranian relations was part of a broad foreign policy goal under which Moscow attempted to use Iran as a "partner" to limit US influence and to prevent the emergence of other regional powers, especially in Central Asia.60

On the Saudi front, Russia also succeeded in re-establishing diplomatic relations after the Gulf War. Moscow had been eager to accomplish this difficult goal throughout the Cold War and seemed to be making progress in 1979 after the Iranian revolution and the signing of the Camp David accords between Egypt and Israel, which hurt US-Saudi relations. But it was not until after the fall of the USSR that serious steps were taken. In 1992, the Russian Foreign Ministry developed and formally implemented a new policy toward the Gulf states to develop economic and political partnerships.61 Russia also sought to broaden the range of states involved in Gulf security by including Egypt, India, Syria and Pakistan.62

The 1993 agreement between Russia and the UAE, negotiated by then-defense minister Pavel Grachev, dramatically expanded arms agreements. These have included the aforementioned BMP-3 deal and the purchase of four Ilyushin-76 transport aircraft, and high technology sharing. In November 1994, Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin even proposed that the two states collaborate in the development of a joint intelligence satellite,63 partly as a platform for expanding Moscows regional contacts.

While Russia is looking for economic openings with smaller Gulf states, it also remains heavily involved in attempting to re-integrate Iran and Iraq into the international community. In part, this can help Russia enhance its regional position and check Washington. But in the case of Iraq, economic reasons are also critical. In addition to recent agreements that would allow Russian companies access to Iraqi oil fields, Russia inherited some $8 billion worth of Iraqi credits from the former Soviet Union.64

Russia and France, which also has considerable economic interests at stake in Iraq, remain the most vocal proponents of lifting the sanctions against Iraq. Russia broke with the Anglo-American sanctions policy toward Iraq as early as 1993, when Moscow dispatched an emissary to Baghdad to work toward Iraqi compliance with international demands.65 In 1994, when Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein yet again moved troops toward the Kuwaiti border and provoked an international crisis, Moscow attempted to mediate between Iraq and the West. In fact, Saddams proposal to withdraw his troops in exchange for a lifting of the sanctions was issued in the form of a joint Russian-Iraqi communique.66 Russian Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev managed in 1994 to convince Saddam Hussein to agree to recognize Kuwaits sovereignty in the hopes that this would prompt the UN to alleviate some of the sanctions against Iraq.67

In the most recent crisis of November 1997, Foreign Minister Yevgeny Primakov played a central role in negotiating an end to a crisis triggered by Saddam Husseins refusal to allow US inspectors to conduct their work in Iraq as part of the UN inspection teams that are ridding Iraq of its weapons of mass destruction. While Primakov was widely viewed as once again attempting to benefit if not strengthen Saddams position, despite his blatant transgressions, in this case, he evidently had Washingtons reluctant imprimatur. Indeed, on the whole, Russia has not pushed its efforts to lift sanctions on Iraq to the point that they would rupture US-Russian relations. It has neither exercised its veto in the UN security council, nor formally argued that the US position on Iraq is untenable.

Iran, Iraq and Global Intervention

Historically, the degree of regional influence that Moscow and Washington enjoyed was in part a function of their ability to manage and sometimes exploit Irans rivalry with Iraq at the regional level, while simultaneously jockeying in their own rivalry at the global level. In the 1970s and 1980s, both the USSR and the United States tried to gain influence with Iran and Iraq, at the expense of the other superpower.

The US-Iranian axis was formalized under the Nixon administrations "twin pillar" policy which placed Iran at the heart of US regional interests. However, when the Shah abdicated his throne in January 1979, Moscow seriously tried to move Iran out of the US orbit, only to discover that Ayatollah Khomeinis disdain for the United States did not translate into an affinity for Moscow. Nonetheless, the USSR continued to woo Tehran to Washingtons chagrin. Thus, the US focused much attention, as was reflected by the Irangate fiasco in 1986-87, on severing Moscows relations with Iran, for fear that these two states could undermine US regional interests.68

Similarly, in the 1970s, Soviet-Iraqi relations were formalized by the 1972 Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation. While this relationship continued into the 1980s, it did not stop the United States from approaching Baghdad in the early 1980s and then tilting toward Iraq after Irans major military victory at the Faw peninsula in February 1986.

US-Russian competition over Iran and Iraq has eased with the fall of the USSR, but it remains at play at a more modest level. Perhaps for the first time in decades, Moscow is in a position to affect both Iran and Iraq. For four basic reasons, Washingtons dual containment policy, while sensible in some ways, has yielded Moscow influence with Iran and Iraq.

First, dual containment aims to punish Iran and Iraq as rogue states by severing their economic, and to some extent, diplomatic links to the international community. This has made Moscow more important to both states. They need Russia to help reintegrate them into the international community and to counter Washingtons significant political influence in various international organizations such as the UN.

Second, Iran and Iraq cannot use their US connections for bargaining leverage with Moscow, as was the case sporadically in the past. This is because all parties realize that such connections are non-existent or irrelevant. This increases Moscows influence with both states, by depriving Iran and Iraq of the ability to play Russia off the United States.

Third, in the past Moscow and the United States had difficulty increasing their influence with Iran and Iraq simultaneously because these states were at war. While this remains a predicament, dual containment policy is creating a potential convergence of interests between Iran and Iraq. Since these two very unlikely allies are both targeted by it, they have some vested interest in joining against it. This interesting dynamic, in turn, offers Moscow greater potential to increase influence with Iran without alienating Iraq, and vice versa. A US-Iranian rapprochement, however, would clearly alter this picture by decreasing the convergence of interests between Iran and Iraq.

Fourth, Iran and Iraq have a vested long-term interest in strengthening their Moscow links. This is in part because at present neither state is likely to envision very positive relations with the United States in the near future. Dual containment does not specify clearly the conditions under which the US would move to improve relations with both states, other than to require of Iran positive behavior in almost every foreign policy area. And, even if it did, these conditions would probably be difficult for Iran and Iraq to accept. Moreover, public sentiment in all three states would likely make any rapprochement in the near-term politically unsavory, although this could shift in the longer run.

The Global-Regional Link: Interconnectedness in Motion

In an interconnected world, the behavior and fortunes of states in one arena of interaction or issue area is likely to be directly or indirectly linked to phenomena in other arenas or issue areas. At the outset of this article, we argued that Moscow is constrained at the regional level, partly because of its interest in maintaining good relations with Washington at the global level. This section of the article develops this argument.

Elements in Russias foreign policy establishment remain quite interested in advancing its position in Southwest Asia and concerned about US influence there. Relative gains clearly matter in US-Russian interaction as suggested by Russian references to balance of power, by Russias view of Iran as an actor critical to checking US power, by the zeal with which Russia seeks to enhance its regional standing, and by the continuing import of the region in Russian global machinations.69 Asked by a Russian news correspondent why Russia needs the Middle East, Foreign Minister Primakov said that under peaceful conditions, the region would be "one of the strongest economic poles," and that Russias general power will increase if it obtains "a far-flung base of support."70 That is, global strategy can be aided by a strong regional presence.

A number of policy makers in Moscow pushed for a more aggressive Near East policy. Primakov, who is close to Iraqs elites, including Saddam Hussein, was quite reluctant to see Iraqs political and military position undermined by the 1991 Gulf War. As US Secretary of State James Baker recalls, Primakov kept on "coming at us with proposals" to give Saddam some face saving formula for withdrawing from Kuwait; his idea was that Moscow should "not help America in the Persian Gulf, that America is on track here to establish a permanent military presence, this is against our interests."71

Primakov wishes to restore Russian regional influence in a manner that could eventually increase areas of conflict and decrease the potential for cooperation. This would especially be true if Primakov and others conclude that they can obtain US support at the global level better through a more active regional policy than through a more accommodating one. As Primakov has stated, after being asked about the loss of Russian influence in regions such as Near East:

We explain our inadequate activity in the Near East by the fact that our efforts were aimed at evening our relations with the former cold war adversaries. But this was done without an understanding of the fact that, by not surrendering our positions in the regions and even strengthening them, we would have paved the way to the normalization of relations. A shorter and more direct way.72

US-Russian interaction in the Third World, however, is linked to interaction at the global level in three principal ways. First, at the global level, economic issues have increased in importance in the hierarchy of issues, while military factors have become less salient. As Russian Foreign Minister Kozyrev has noted perhaps too optimistically and diplomatically, cooperation exists on, "almost every big issue in the world."73

In fact, while some Russians resent the US and its position on such issues as NATO expansion, Russia needs US economic support to make the transition away from empire and toward a market economy. It is counting on the "partnership for economic progress" understanding between the two states to yield it trade, economic and investment opportunities. This is of particular importance, because Russias level of foreign investment and trade is paltry for a country of its size. Bilateral trade doubled between 1992 and 1994 to $5.8 billion74 and could also increase substantially through independent business interaction and government coordinated action. The downturn in Asian economies in 1997, moreover, has increased Russias need for US economic support, chiefly by threatening to divest Russian banks of both foreign and Russian investment. In response, Russia has quietly sought loans from Washington to back-up Russian Central Bank reserves.

The Russian-American intergovernmental commission on economic and technical cooperation is important to Russia in facilitating US loan guarantees and credits for a variety of Russian projects. And US support of Russia economic interests at the International Monetary Fund and with the G-7 major industrialized states is also critical. In brief, areas of interdependence are expanding between the two states and, arguably, are acting as a constraint in cases where the states might prefer conflict to cooperation.

Second, Russia and the United States also have a vested interest in a range of strategic issues. Russia wants to play a role in a new system for European security, and also needs US cooperation on the volatile issue of NATO expansion and Bosnia, even as it opposes elements of the US approach. The Bosnian imbroglio, moreover, could eventually pit the two states on opposite sides, thus making coordination on this issue important. Russia needs US cooperation to make sure that US and NATO action do not undermine the Serbs, and necessitate a Russian response.

While differences continue on NATO issues, NATOs cooperation with Russia is, in the view of General Shalikashvili, then Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, "developing, the exchange of delegations is being expanded."75 Numerous initiatives also have been undertaken on such issues as the Start II talks on nuclear weapons, sharing of spy satellite information,76 and the conversion of Russian defense nuclear companies and the safety of existing Russian nuclear facilities and materials.

Third, even at the political level, Russia needs US cooperation, investment and cultural exchange to develop democratic traditions. Indeed, in the June 1992 "Charter of American-Russian Partnership and Friendship," Presidents Bush and Yeltsin pledged cooperation in this area. Moscows interest in economic, security, and, to some extent, political cooperation and interdependence at the global level of interaction benefits Washington 77 and circumscribes just how far it can rival Washington at the regional level.

The argument that economic, political and strategic interdependence at the global level is constraining Moscows behavior at the regional level is evident in several cases. Moscow supports the post-Gulf War UN Resolution 687 against Iraq and US-led sanctions against Baghdad, despite its desire to penetrate Iraqs post-war reconstruction market, obtain payment for outstanding loans to Baghdad, and re-connect politically with a potentially rehabilitated former ally. Were it to undermine Washington formally on these issues, that would constitute a threat to movement on US-Russian relations at the global level.

Similarly, when the US fired 44 cruise missiles at Iraq in September 1996 to punish Saddam for attacking the Kurds in Northern Iraq, the Russian leadership did not support this action at the UN. This helped it avoid an internal conflict with pro-Iraqi military and political factions, and to save face with Iraq, which owes Russia more than $8 billion. At the same time, and more importantly, Russia also did not veto or condemn US action. Quite the contrary, while many analysts expected a tough Russian stance, Moscow did its utmost to assure Washington that its mediation efforts were not directed against US interests78 and that it would not undermine cooperation between the two countries as co-sponsors of the Middle East peace process.79 While this resulted in part from its concern about provoking Iran, which US actions against Iraq were benefitting indirectly, it was most related to concern about US-Russian relations at the global level.

On the Iran front, Russia is supplying Tehran with nuclear reactors and various arms. However, even on this issue where Russia has overriden economic and political interests, it has attempted to present such sales to Iran in positive terms and even to consider supplying Iran with equipment that will not "arouse" US objections.80 In some measure, Moscow as sought to assure Washington that it will limit its military cooperation with Iran, while pursuing aspects of it nonetheless.

Furthermore, Russia has grudgingly accepted NATO expansion, despite some legitimate concerns about its implications. Opposing the initiative altogether could have disrupted US-Russian relations. Instead, Russia took a strong stand in part so that it could relax its opposition in exchange for benefits from the West, including probable participation in the Paris Credit Club and an invitation to the World Trade Organization.81

At the regional level, we observe ongoing rivalry, mistrust, and potential conflict in US-Russian relations in the Gulf region. Meanwhile, at the global level, we see growing linkages between Russia and the United States at multiple levels and issue areas, the limits on risk-taking that both sides face, and the emergence of various areas of cooperation. Together, these observations suggest that US-Russian relations in the Persian Gulf region remain rivalrous, but that the imperatives of post-Cold War transition are likely to prevent this rivalry from re-assuming any serious Cold War dimensions. Inasmuch as Russian foreign policy is coherent and unified, Moscow has pushed its agenda in the region against US interests, but not so far as to cause a serious rupture in US-Russian relations. As one high-level Russian policy maker put it, "We will not let the West dictate to Russia how far it can go in its relations. Of course, we will try at the same time not to damage our relations with the West."82

Arguably, Russia is more aggressive in its relations with Washington at the regional level than it is at the global level, in part because its Middle East policy makers, who have longstanding contacts in the Arab world and not great trust for the US regional role, reflect this traditional stance.

The future of US-Russian relations in the Persian Gulf, to be sure, is contingent on numerous factors, many of which cannot be foreseen. However, at the same time, important changes are in motion that cannot be reversed easily. It appears that the areas where Russia is willing to take major risks in the region have decreased, largely because Moscow puts a high premium on strong relations with Washington at the global level.

It follows that deteriorating relations at the international level will likely have spillover effects, by leaving Russia with much less to lose in seriously challenging the US at the regional level. Indeed, if, as we argue here, Russias interest in US cooperation on non-Persian Gulf issues is indeed decreasing its propensity to rival Washington at the regional level, then serious conflict over these issues is likely to portend poorly for US-Russian interaction on Gulf regional issues.

In Conclusion: Conceptualization, Theory and Future Research

The questions addressed herein are of some broader relevance. While this study has focused empirically on the Persian Gulf, the issue of how US and Russian relations are expressing themselves in the post-Soviet era in other regions of the world deserves more attention as well. This is because the end of the Cold War has altered such dynamics across regions. Understanding the changing linkages between the micro- and macro-levels, however, requires an adjusted frame of reference.

First, at the broadest level, we need to be more attuned to how the global and regional levels of analysis are both distinct and related. This is not just a question of definition. Rather, it is one that can yield insights into a range of phenomena that are partly a function of these linkages but which are not explained in these terms, and overlooked or misunderstood as a result.

Second, more concretely, this article has emphasized the importance of assessing how events at the global level affect the position of a particular state at the regional level. Such analyses can yield a better understanding of how a region is changing, and of particular outcomes in that region. Thus, the notion advanced here that the fall of the Soviet Union in some ways improved Russias economic and political position in the Persian Gulf may also yield insight into why and how Moscow could play an important role in initially helping resolve the 1997 crisis between the US and Iraq, a crisis triggered by Iraqs refusal to allow American inspectors to join UN inspection teams entrusted with ridding Iraq of weapons of mass destruction.

Third, beyond exploring how the position of a particular state is changing, it is useful to examine how the interaction between Moscow and Washington is shifting as a result of micro-macro level factors. For instance, developments in one sphere alter outcomes in the other, by affecting how nations at both levels perceive, frame, and deal with events, opportunities, and challenges at both levels. This micro-macro linkage needs to be better understood.

Understanding this linkage, in turn, requires a better sense of change at both the global and regional levels. This is particularly true given that the end of the Cold War has significantly altered relations within and between these two levels of interaction. Failure to understand how and why this is occurring will likely yield inaccurate analyses of how the two levels are related.

In particular, greater effort is needed to understand how the changing context at both levels is altering how sovereign interests are prioritized in both Moscow and Washington. For instance, in the present case, we have argued that as compared to the past, Moscow now puts a higher premium on US relations at the global level than on its regional goals; on economic cooperation than on strategic rivalry in the Gulf. But further questions are: to what extent does it emphasize one goal as opposed to another? When will it do so? And in what measure and how might it pursue both goals simultaneously?

Future work might explore these questions in greater detail either through the case study approach, or through the logic of two-level game theory which can take into account and explore the connection between variables at both the global and regional level. In so doing, such work can also make more clear the changing areas of potential cooperation and conflict between Washington and Moscow, and, based on this analysis, offer some insights into how they can cooperate to deal with regional problems over which they both have some influence.

Fourth, theory-oriented scholars might also explore what global change means for an understanding of US-Russian interaction and of theory. Scholars from both the realist and liberal traditions have argued that their general theory, and its various intellectual progeny such as neoliberalism and neorealism,83 represent a better guide to world politics than the opposing school. This debate has been dominated by abstract discussion, which has focused on the assumptions, central concepts and arguments of each school. While some interesting efforts have been made to examine empirically the relative merits of both schools,84 future work would do well to explore these theories against reality.

Many strains of thought exist within these major schools. However, some basic features of both schools can be identified in brief, bearing in mind that for present purposes this is intended as a broad sketch rather than as a nuanced account.

By and large, thinkers in the liberal tradition tend to believe that realists exaggerate the importance of states as actors in world politics, dramatize the negative effects of anarchy, underestimate the potential for cooperation, and overestimate the potential for conflict and the use of force.85 Some of them see world affairs as evolutionary in that states can improve their interstate behavior, than as cyclical.86 While both schools recognize the importance of anarchy in affecting state behavior, realists and liberal thinkers differ in important ways on its nature, impact and severity. Realists stress the negative consequences of anarchy, while liberal thinkers feel that while these consequences are at play they are not so severe. Liberal thinkers are more sanguine about the possibility that such things as regimes, international organizations and sometimes interdependence can increase the potential for cooperation under anarchy.87

To be sure, great power relations even during the Cold War reflected elements of both theoretical models. However, the fall of the Soviet Union and developments in the Persian Gulf have altered the extent to which both models apply. This is not so much because the realist model is not as applicable at the regional level in the post-Soviet era, but rather because elements of the liberal model are now more salient at the global level.

While important changes have taken place at the regional level, both states continue to compete for strategic position and influence. They are using various forms of statecraft analyzed in this study, such as arms sales, trade and diplomatic access, not only to score economic gains but also to enhance their broader influence. Their relations remain marked by not insignificant distrust as evidenced by profound US doubts over the nature of Moscows nuclear connection to Iran, by US insistence that Russia not be included in regional security frameworks, and by doubts in certain circles in Washington about Russias negotiating role during the November 1997 Gulf crisis.

Both states also remain concerned about the gains of the other and interested in checking the others power and even undermining it on given issues. Furthermore, relative gains clearly matter in US-Russian interaction as suggested by Russian references to balance of power, by Russias view of Iran as an actor critical to checking US power, and by the zeal with which Russia seeks to enhance its regional standing.

However, US-Russian interaction at the regional level is linked to interaction at the global level. On the whole, elements of both the realist and liberal models apply in explaining US-Russian relations in the post-Soviet era. The realist model remains relevant at both the regional and international level, but the liberal model is assuming greater relevance at the global level. In this sense, the liberal and realist models, and their myriad progeny, need not be mutually exclusive. Rather, their use in tandem can be useful.88

The realist model points to ongoing rivalry, mistrust, and potential conflict in US-Russian relations in the Gulf region. Meanwhile, the liberal model illuminates the growing economic, political, and cultural linkages between Russia and the United States at multiple levels and issue areas, the resulting limits on risk-taking that both sides face, and the emergence of various areas of cooperation. Together, both models reflect the notion that US-Russian relations in the Persian Gulf region remain rivalrous, but that the imperatives of post-Cold War transition are likely to prevent this rivalry from re-assuming any serious Cold War dimensions. Inasmuch as Russian foreign policy is coherent and unified, Moscow has pushed its agenda in the region against US interests, but not so far as to cause a serious rupture in US-Russian relations. It is fair to say that the areas where Russia is willing to take major risks in the region have decreased, while the areas of potential cooperation between Moscow and Washington have increased. This is in part because Moscow, and to a lesser extent Washington, put a premium on maintaining strong relations at the global level. Thus, should these relations falter, corresponding negative consequences at the regional level are likely to follow.

TABLE 1: US AND RUSSIAN ARMS TRANSFERS TO THE GULF REGION

Endnotes

1. The Persian Gulf accounts for some 19 percent of American oil imports;

44 percent of European oil imports; and 70 percent of Japanese oil imports.

Persian Gulf Oil Export Fact Sheet (Washington, DC: United States Energy

Information Administration, 1997).

Return to Article

2. Personal interviews with former and current Department of Defense

and State officials (June- August, 1996, Washington, DC). Also, for background

on such efforts, see Konstantin E. Sorokin, "Redefining Moscows Security

Policy in the Mediterranean," Mediterranean Quarterly, 4 (Fall 1993),

pp. 26-45.

Return to Article

3. See Steve Yetiv, "How the Soviet Intervention in Afghanistan

Improved the U.S. Strategic Position in the Persian Gulf," Asian Affairs:

An American Review, 17, no. 2 (Summer 1990), pp. 62-81.

Return to Article

4. David A. Baldwin, "Neoliberalism, Neorealism, and World Politics,"

in David A. Baldwin, ed., Neorealism And Neoliberalism: The Contemporary

Debate (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), p. 23.

Return to Article

5. Robert D. Putnam, "Diplomacy and domestic politics: the logic

of two-level games," International Organization, 42 (Summer 1988),

pp. 430-60.

Return to Article

6. See Steven R. David, "Explaining Third World Alignment,"

World Politics, 43 (January 1991), p. 233-56.

Return to Article

7. For a succinct literature review, see Putnam, "Diplomacy,"

pp. 430-33.

Return to Article

8. Lester R. Brown, World Without Borders (New York: Random House, 1972),

p. 185. The notion that the world is increasingly interdependent is challenged

in some scholarly quarters. However, strong evidence supports this notion.

On the rise of interdependence, see Oran Young, "Interdependence

in World Politics," International Journal, 24 (1969), pp. 72650; Robert

O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye, Power and Interdependence (New York: HarperCollins,

1989); A. Scott, The Dynamics of Interdependence (Chapel Hill, NC: University

of North Carolina Press, 1982). Also, for a brief discussion of the interdependence

literature, see Lauri Karvonen and Bengt Sundelius, "Interdependence

and Foreign Policy Management in Sweden and Finland," International

Studies Quarterly, 34 (June 1990), esp. pp. 211-13. For indicators that

show a rise in interdependence, see Mark J. Gasiorowski, "The Structure

of Third World Economic Interdependence," International Organization,

39 (Spring 1985), p. 331-42. On rising interconnectedness in world politics,

see Robert B. Reich, The Work of Nations (New York: Knopf, 1991), esp.

p. 138. Also, see Barbara G. Haskel, "Access to Society: A Neglected

Dimension of Power," International Organization, 34, no. 1 (Winter

1980), p. 89-120. James N. Rosenau, The Study of Global Interdependence:

Essays on the Transnationalisation of World Affairs (London: Frances Pinter,

1980), p. 3.

Return to Article

9. Barry Buzan, "Regional Security as a Policy Objective: The

Case of South and Southwest Asia," in Alvin Z. Rubinstein, The Great

Game: Rivalry in the Persian Gulf and South Asia (New York: Praeger, 1983).

Return to Article

10. For instance, see Andrew Gamble and Anthony Payne, eds., Regionalism

& World Order (New York: St. Martins, 1996).

Return to Article

11. While attempts have been made to curb excess production, the widescale

privatization program announced in 1993 has largely been shelved, although

the Ministry of Defense has had some success in forcing the most unprofitable

firms and factories out of production. By concentrating on export production,

it has been able to gain capital to fund research and development on the

next generation of conventional weapons. IISS, The Military Balance, 1996/97

(London: Oxford, 1996), p. 110.

Return to Article

12. Statement by State Department official Nicholas Veliotes in Hearing

Before the Committee on Foreign Policy, US Senate, 97th Congress, April

1982, p. 147.

Return to Article

13. Steve Yetiv, "U.S.-Russian Rivalry and Cooperation in the

Persian Gulf: The Great Game of Modern Times," Journal of South Asian

and Middle Eastern Studies, 21, no. 3 (forthcoming).

Return to Article

14. Richard Grimmett, "Conventional Arms Transfers to Developing

Nations, 1988-1995," CRS Report for Congress, 96-677 F (Washington,

DC: CRS, 1996), p. 2.

Return to Article

15. Ibid., p. 38.

Return to Article

16. These American restrictions have, in fact, created opportunities

for other states. When the United States refused to sell the most updated

version of the M1A2 to the United Arab Emirates, the state turned to France

and purchased some 396 Leclerc MBTs.

Return to Article

17. "New Arms Sales Deal With Iran ÈQuite Likely,"

Foreign Broadcast Service (FBIS), Daily Report: Central Eurasia (CEURA),

12 May 1995, p. 19 from Nezavisimaya gazeta, 12 May 1995, p. 2.

Return to Article

18. "Land of Crisis and Upheaval," Janes Defence Weekly,

(30 July 1994), p. 29.

Return to Article

19. Anoushiravan Ehteshami, "Irans National Strategy: Striving

for Regional Parity or Supremacy?" International Defence Review, no.

4 (April 1994), p. 35.

Return to Article

20. Andrew Rathmell, "Irans Rearmament How Great A Threat,"

Janes Intelligence Review, (July 1994), p. 320.

Return to Article

21. Sorokin, "Redefining," p. 40.

Return to Article

22. James Bruce, "France Bolsters GCC With Abu Dhabi Accord,"

Janes Defence Weekly, (28 January 1995), p. 5.

Return to Article

23. On the arms sale and other contentious issues, see Leszek Buszynski,

"Russia and the West: Towards Renewed Geopolitical Rivalry,"

Survival, 37 (Autumn 1995), esp. p. 120. Also, on Russias renewed interest

in and policy toward the Gulf, see Stephen Foye, "A Hardened Stance

On Foreign Policy," Transition, 9 (9 June 1995), pp. 36-40.

Return to Article

24. See text of interview in Tehran IRNA, in FBIS: NES, (8 March 1995),

p. 51. Also, Tehran ABRAR, in FBIS: NES, (17 March 1995), p. 71.

Return to Article

25. Edwin Bacon, "Russian Arms Exports A Triumph for Marketing?,"

Janes Intelligence Review, 6, no. 6 (June 1994), p. 268.

Return to Article

26. Russian military transfers rose from a low of $1.7 billion in 1994,

to $3 billion in 1995. Ibid.

Return to Article

27. Rolf Hilmes, "Russias Latest Attack on the IFV Market,"

International Defence Review, 26, no. 5 (May 1993), pp. 398-99.

Return to Article

28. Sarah Walkling, "U.S. Arms Sales Continue Decline, Russia

Top Exporter in 1995," Arms Control Today, 26, no. 6 (August 1996),

p. 33.

Return to Article

29. See, for instance, Moscow KRASNAYA ZVEZDA in FBIS, CEURA, (13 September

1996), p. 6.

Return to Article

30. As evident in a speech by the Kuwaiti Ambassador to the United States,

Mohammad al- Sabah, (World Affairs Council, Norfolk, Virgnia, 11 April

1997).

Return to Article

31. US Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs,

Developments in the Middle East, 24 June and 30 June 1992 (Washington,

DC: GPO, 1992), p. 9.

Return to Article

32. IISS, The Military Balance, 1995-96 (London: Oxford University Press,

1995), pp. 139, 144- 46.

Return to Article

33. Russia has some 4,300 troops in Armenia (including a squadron of

Mig-23s); 8,500 troops in Georgia; 6,400 in Moldova; and 18,000 in Tajikistan

(including 6,000 "border guards"); IISS, Military Balance, p.

115.

Return to Article

34. Authors interviews with high-level Arab officials (Washington, DC,

July and October, 1996).

Return to Article

35. James J. Emery, Norman A. Graham and Michael F. Oppenheimer, Technology

Trade With the Middle East (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1986), pp. 4-11.

Return to Article

36. GATT, International Trade: 1990-91, 1, (Geneva: GATT, 1991), p.

10.

Return to Article

37. On the nature and basis of this move, see statement by Secretary

of State Warren Christopher in US Department of State Dispatch, 6 (8 May

1995), p. 387.

Return to Article

38. Yuri Sigov, "Russian Business Slowly Moves Toward the Persian

Gulf," Moscow News, 18 November 1994, p. 8.

Return to Article

39. Melvin Goodman, "Moscow and the Middle East in the 1990s,"

in Phebe Marr and William Lewis, eds., Riding the Tiger: The Middle East

Challenge After the Cold War (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1993), pp. 22-23.

Return to Article

40. Kuwait alone has lent Moscow some $1.064 billion, see "Strategy

for Debt Repayment Viewed," FBIS, CEURA Supplement, 14 June 1995,

p. 4, from Kommersant-Daily, 21 April 1995, p. 4.

Return to Article

41. Irina Skibinskaya, "Arab Petrodollars Flow into CIS,"

Moscow News, 20 August, 1993, p. 8.

Return to Article

42. Gulf Russia spent some $6 million to develop these fields in exchange

for the rights to some 300 million barrels. See "Gulf Russia,"

The Oil and Gas Journal, 91, no. 20 (May 1993), p. 27.

Return to Article

43. "Pipes and Drums," The Economist, 23 November 1996, p.

7.

Return to Article

44. "Russia Has Signed Agreement to Develop Iraqs North Rumaila

and West Qurna Fields Once the U.N. Embargo is Lifted," The Oil and

Gas Journal, 93, no. 18 (May 1995), p. 4.

Return to Article

45. "Iraq Trade Pact Could Effect Embargo Stance," FBIS,

CEURA, 16 September 1994, p. 14, from Izvestiya, 1 September 1994, p. 1;

"Oil Consortium Awaits Lifting UN Sanctions in Iraq," FBIS,

CEURA, 13 September 1994, pp. 13-14, from Interfax, 12 September 1994.

Return to Article

46. See, "Russia and Iran Continue to Press for Cooperative, Multinational

Development of Caspian Sea Oil and Gas," The Oil and Gas Journal,

94, no. 11 (March 1996), p. 3; Russia is also engaged in a $7.95 billion

development in the Caspian region with Azerbaijan and several multinational

corporations. Ibid.

Return to Article

47. "Gazprom in Deal with Iran," Financial Times, 21 April

1997, p. 2.

Return to Article

48. Konstantin Zatulin, "Russias Interests and the Caspian Oil

Consortium," Current Digest of the Post-Soviet Press (CDPP), 47, no.

44 (November 1995), p. 14.

Return to Article

49. Patrick Crow, "Competition for the Caspian," The Oil

and Gas Journal, 94, no. 49 (December 1996), p. 40; "Irans Support

on Caspian Oil Deal Seen as Ineffective," FBIS, CEURA, 25 May 1994,

p. 14, from Izvestiya, 23 May 1994, p. i.

Return to Article

50. For more details, see Michael R. Gordon, "As West Shuns Iran,

Russia Pulls Closer," New York Times, 12 April 1997.

Return to Article

51. "OPECs Tough Question," The Oil and Gas Journal, vol.

93, no. 47 (November 1995), p. 25.

Return to Article

52. In 1995, Irans debt to Russia totaled close to $582 million (including

$382 million owed to Rosvooruzheniye), while Russia owed Iran some $195

million. See Sergei Stroken, "Time to Repay Debts," CDPP, 31

January 1996, pp. 23-24, from Moskovskiye novosti, 14 January, p. 13.

Return to Article

53. Sergei Stroken, "Russia and Iran Want Partnership," Moscow

News, 12 January 1996, p. 6.

Return to Article

54. Lecture by the Secretary General, Ukaz, in FBIS, Middle East, 13

February 1986, C-1.

Return to Article

55. See the text of Foreign Minister Qatbzadehs message to Andrei Gromyko

in Tehran Domestic Service, in FBIS, South Asia, 15 August 1980, I, pp.

5-6.

Return to Article

56. Interview with Irans Ambassador to the USSR, Tehran Keyhan, in FBIS,

SA, 15 April 1987, p. 13.

Return to Article

57. Commentary in Pravda, in CDPP, 3 April 1985, p. 9.

Return to Article

58. For example, see FBIS, USSR, 2 March 1989, p. 27; also, FBIS, USSR,

3 August 1989, p. 11.

Return to Article

59. For an excellent overview on changing relations with Gulf states,

see Goodman, "Moscow."

Return to Article

60. "Iran Said Crucial Partner in Region," FBIS,

CEURA, 8 March 1995, p. 51, from IRNA, 8 March 1995.

Return to Article

61. Sorokin, "Redefining," p. 43.

Return to Article

62. "ABRAR on Russian Roundtable," FBIS, Near East, 17 March

1995, p. 72, from ABRAR, 7 March 1995, p. 2.

Return to Article

63. Jacques de Lestapis, "Gulf Powers Procure to Protect,"

Janes Defence Weekly, 18 March 1995, p. 45.

Return to Article

64. George JoffÄ, "Iraq The Sanctions Continue," Janes

Intelligence Review, (July 1994), p. 314.

Return to Article

65. Aleksandr Shumilin, "Russian Foreign Ministrys Baghdad Nights:

What Was I, Melikov Doing in Iraq Last Week?" CDPP, 45, no. 8 (March

1993), p. 14.

Return to Article

66. For details of Russias arbitration efforts, see Dmitry Gornostayev,

"Russias Difficult Partners," CDPP, 46, no. 41 (November 1994),

p. 12.

Return to Article

67. Stanislav Kondrashov, "Kozyrevs Gulf Diplomacy Gets Differing

Ratings: What Russia Wanted to Prove in the Iraq Affair," CDPP, 46,

no. 42 (November 1994), p. 12.

Return to Article

68. For instance, see de-classified memo "Towards a Policy on

Iran," from Graham Fuller to the director of the CIA, 17 May 1985.

Return to Article

69. For one view of Russias regional motives, see Stephen J. Blank,

"Russias Return to Mideast Diplomacy," Orbis, 40 (Fall 1996).

Return to Article

70. Interview with Primakov by Vladimir Abarinov, in Sevodnya, 5 November

1996 in CDPP, no. 44.

Return to Article

71. Secretary of State James A. Baker III, interviewed on Frontline,

Broadcast, 9 and 10 January 1996.