Articles

For Better or Worse?

Learning and American (-led) nation building in the Balkans1

Patrice C. McMahonUniversity of Nebraska

ABSTRACT

Ongoing American involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq raises fundamental questions about this great power's historical experiences with nation-building, specifically its ability to learn from the past. It is certainly true that the United States has been an active nation-builder, aiming not only to put states back together but ultimately to transform and recreate societies. In 1995, it took the lead in ending the violence that engulfed Bosnia-Herzegovina. American efforts in this Balkan country provide an excellent case study to evaluate its ability to learn and improve upon its policies. Looking briefly at the literature on learning and then at Bosnia's reconstruction, this paper argues that the Bush administration's ideological beliefs, specifically what some have called “doctrinal unilateralism,” have led this administration to ignore important lessons wrought from the Balkans.INTRODUCTION

1 In the latter part of 1995, the United States took the lead in ending the horrific violence that engulfed Bosnia-Herzegovina for more than three years. Again in 1999, it led members of the international community in calming ethnic tensions in Kosovo. Together, these two efforts meant that by the century's end, an American presence was clearly visible throughout the Balkans. Since taking office, President George W. Bush has not only maintained American commitment to this region, but he has made the oncederided concept of "nation-building" and the problem of failed states central concerns of US foreign policy.2 American-led efforts have indeed accomplished a great deal in the Balkans.3 However, this paper argues that the Bush administration's ideological beliefs, specifically what some have called "doctrinal unilateralism" have meant that the US has wholly ignored or failed to learn important lessons from the Balkans.4 As a former US Army retired General put it, "the U.S. mission in Iraq has been made more difficult by this administration's aversion to nation-building and its determination not to study the lessons" of the past.5

2 International relations scholars who focus on the concept of learning would not be surprised by this failure to learn or by the inability of the administration to improve its policies based on historical experiences. In fact, much of the scholarly research on the topic of learning concludes that policymakers often do not learn; instead, they use history selectively, drawing inappropriate parallels to the past and intentionally misreading the lessons of history to justify their positions.6 After reviewing in Part I some of the extensive literature on foreign policy learning, the article argues that the basic learning model – which posits a causal relationship between past events and current beliefs and policies – is not helpful in understanding current US policies toward failed states. What is more useful is an understanding of the ideology that has underpinned American foreign policy under President Bush. I, thus, contend that instead of learning from the Balkans and experiences on the ground – both good and bad – faith in American military strength, unilateralist policies, and universalism have prevailed.7

3 Part II turns to the Balkans, summarizing unique characteristics of the region and peace-building efforts there to account for the relative success of this nation-building exercise. Part III explains the impact of Bush's doctrinal unilateralist thinking on assumptions and policies toward failed states. In particular, I discuss four myths that were evident in the discourse and behavior of the US as it geared up for interventions in other countries. With evidence from American-led efforts in the Balkans, I explain why these myths are not only wrong but have proven dangerous guides for ongoing peace-building activities in places like Afghanistan and Iraq. The paper concludes with additional lessons based on the peaceful but still fragile environments in Bosnia and Kosovo today.

Foreign Policy Learning

4 Since the early works of Ernest May and Robert Jervis in the 1970s, the concept of 'learning' has waxed and waned in international relations research. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to distill some of the insights on how and when decision-makers are most likely to learn. This literature is vast, and my goal is neither to summarize this extensive and interdisciplinary pursuit, nor to explain the many conceptual and empirical problems associated with defining, isolating, and measuring foreign policy learning.8 Instead, my aim is to draw on some of these theoretical insights to make the case that although many parts of the US government had developed long lists of "the lessons" of Bosnia and Kosovo, President Bush and his senior advisors intentionally ignored these lessons or derived just the opposite points to support their ideological inclinations and policy goals.9 Consequently, ideology and a distinct disdain for nation-building fashioned and distorted the country's assumptions about failed states, producing worse, rather than better, policies in Afghanistan and Iraq.10

5 Scholars have developed a variety of different definitions of learning.11 I think of learning in terms of individuals, and a change in beliefs, or the development of new beliefs, skills, or procedures as a result of the observation and interpretation of experiences.12 Learning does not necessarily mean policy changes, nor does it mean that leaders must acknowledge the empirically correct or normatively desirable lessons of history. However, especially when one thinks of learning in security policy, it is most useful to consider when specific individuals within governments (like presidents in the US) are most likely to change their beliefs or develop new ones. There is, in fact, some consensus on this, and it points to failure, rather than success, in encouraging individuals to learn, as do first-hand experiences, or the occurrence of a major event in the formative period of a decision-maker's life.

6 Robert Jervis contends that even when these conditions are present, learning is often thwarted because people tend to pay more attention to what has happened rather than to why it has happened. This process yields broad generalizations about events that usually fail to strip away from the past events those facets that depend on the ephemeral context.13 Politicians, in fact, often seize upon historical analogies to bolster their preexisting beliefs and preferences rather than allowing the past to shape their beliefs and policies.14 In theorizing about foreign policy learning, Philip Tetlock hypothesizes that since governments are organized hierarchically, with fundamental assumptions and policy objectives at the highest level, policy beliefs and preferences at an intermediate level and tactical beliefs at the bottom, most learning happens at the tactical level. Policy decision-makers at the top can learn and will reconsider their basic strategic assumptions and objectives – but only after repeated strategic failures. Tetlock maintains that "fundamental learning is so psychologically difficult that it is likely to occur only in conjunction with massive personnel shift."15 Taken together, these few propositions suggest that foreign policy learning is neither guaranteed, nor based solely on historical events. What these propositions do not say explicitly but should is that learning is always mediated by ideology and politics.

7 Scholars have noted that, as a presidential candidate, George W. Bush took a clear stand on nation-building and what he saw as Clinton's humanitarian 'escapades' in the Balkans.16 During the second presidential debate with Vice-President Gore, Governor Bush even stated that there would be no kind of nation-building corps coming from America because the US military was meant to fight and win wars not build nations.17 By 2002, the administration started to adopt a different attitude, mentioning General George C. Marshall and U. policy toward Europe after the Second World War. In one speech, Bush reassured Afghans that the US was committed to their country's reconstruction; "We're tough, we're determined . . . we will stay until the mission is done."18 Later the President would adopt a similar take on Iraq, asserting that the rebuilding of this country would constitute a central part of American history and that it would remain in Iraq as long as necessary.

8 It would be easy to chalk up this policy reversal to learning or to the post-11 September world, "where poverty and hopelessness" spawned terror and terror threatened both US and world security, requiring the United States to engage in nation-building.19 with failed states as well as the other conditions deemed critical for learning, it is more plausible that his preexisting beliefs and enduring foreign policy objectives had far more sway over his behavior toward other failed states and military intervention. In fact, for the Bush administration, "the war (in Iraq) seemed like a win-win situation. The U.S. could oust a dictator, usher in a new era in Iraq, and shift the balance of power in the Middle East, all without committing itself to a lengthy, costly, and arduous peacekeeping or nation building mission."20

9 David Brian Robertson further hypothesizes that policy-makers are more likely to use history selectively to achieve their policy goals in areas where facts are contested, values are complex, and partisan differences are sharp.21 It is, thus, reasonable to conclude that current American policy toward Afghanistan but especially Iraq, at least at the highest levels, is more influenced by ideological proclivities than by historical events. In fact, unlike the Clinton administration's thinking as it contemplated war with Kosovo, the Bush administration actively discouraged any comparisons or references to Bosnia.22 At one point, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld even asserted that he wanted to be sure that Iraq did not become another Bosnia, that reconstruction and political issues were worked out in advance so that the US would be able to say that "the mission is over and the troops can leave."23 At the same time, in government documents and papers related to US policy toward failed states, Bosnia and Kosovo went from being a waste of American resources to examples of how the US had effectively responded and helped construct stable states.24 Once in Iraq, US leaders were groping for historical models but instead of reflecting on the merits of the Balkans, both the achievements and the pitfalls, it looked elsewhere. James Dobbins, an expert on military intervention and nation-building, concluded that the "administration was neglecting the lessons of Bosnia at its own peril," choosing to see Germany's reconstruction as an appropriate comparison and model for Iraq.25

10 The terrorist attacks on the US did not so much prompt a fundamental transformation in the President's view of nation-building than they provided additional evidence and legitimacy for his administration's foreign policy convictions and specifically the need for regime change in Afghanistan and Iraq. As Ivo H. Daalder and James M. Lindsay explain, the accusations that President Bush lacked knowledge about world affairs is not entirely correct; in fact, although foreign policy was clearly not his main concern, the President had a fairly coherent foreign policy philosophy that was evident long before the September 2001 attacks on the United States.26 Like his predecessors, President Bush emphasized security, prosperity, and freedom in his speeches on US foreign policy. What was distinctive and perhaps even revolutionary about his approach was how he thought that the US should achieve these foreign policy goals. Given the United States' unique position and power, the Bush administration contended that it did not need to abide by the stipulations of international organizations or multilateral agreements.27 In lockstep with his top advisors, Bush championed "assertive nationalism," emphasizing America's special mission in the world and his administration's willingness to use military force to defend the country from any threat.28

11 Articulated formally in September 2002, the Bush administration's grand strategy emphasized American unilateral power and the right to preemptive attack. At the same time, the President pledged to use the country's position of dominance to "bring the hope of democracy, development, free markets and free trade to every corner of the world."29 According to John Ruggie, the unique fold of the administration's approach was the "doctrinal belief that the use of American power abroad is entirely self-legitimating, requiring no recourse to the view or interest of others and permitting no external constraints on its self-ascribed aims."30 In Daalder and Lindsay's words, Bush believed that America was "unbound," unfettered by other countries or the so-called "international community." It was this ideological attitude, rather than any lessons derived from the Balkans, that ultimately informed, if not misinformed, the policy prescriptions for how the US should behave in places like Afghanistan and Iraq. In fact, when discussions turned to the "Bosnia precedent" or how experiences in the Balkans could inform Iraq policy, high-ranking members of the Bush government claimed that "Bosnia wasn't the proper precedent to study."31 Rather than taking stock of achievements and shortcomings and using Bosnia and Kosovo as examples of what to emulate and what to avoid, the administration's ideological credo triumphed, ultimately leading to worse, rather than better, responses toward subsequent failed states.

The Balkan Exception?

12 Interestingly, Bosnia and the Balkans have become the examples de jure of successful American-led intervention and state reconstruction. As The New York Times recently acknowledged, however attractive the Bosnia analogy is these days for helping American policy-makers sort out the mess it created in Iraq, it is quite an inappropriate model.32 The article explains why international involvement in Bosnia was so successful and lists three conditions that made the Balkans so unique, other than the most obvious: the unusual role of the US in this region and its status as a fairly neutral actor with little to gain from its involvement. However, there are at least three other qualities that make international involvement in this Balkan country exceptional and difficult to recreate.

13 First, the size of a country matters for many obvious reasons, and although Bosnia is large compared with Kosovo, it is still only a country of about 4.5 million people. Kosovo's population is estimated at around 2 million. Iraq's population (27.5 million) and Afghanistan's (31.9 million) stand in stark contrast to these mere city states. Numbers are important for many reasons but most immediately because the size of a targeted country's population has a direct bearing on the need for and the ability of occupying troops to gain superiority, if not a monopoly on violence. That is to say, troop-to-task ratio has a direct bearing on a foreign force's ability to gain and retain a monopoly on violence. Without this monopoly, so-called "state leaders" are only competitors for the reigns of power and authority. Iraq is a good example of this, but as others have noted, President Hamid Karzai's power in Afghanistan barely goes beyond the gates of Kabul.33

14 A second fundamental difference between the Balkans and ongoing cases of American-led peace-building is, as real estate professionals remind us, location, location, and location. Nestled in Europe, albeit on its periphery, Bosnia is about two hours by plane from stable Vienna or wealthy Rome and next to democracy's birthplace, Athens. This made it easier, as well as more logical, for the international community (read European Union states) to want to sink money, time, and thought into these war-torn states. Location directly affects national interest. Not surprisingly, Europe, by way of the EU or individual country donations, has played a more significant role in providing economic assistance for reconstruction and political direction.34 From 1999-2004, for example, the EU alone provided more than one-third of all aid to Kosovo. 35

15 Regardless of where the money originates, the investment in rebuilding these European statelets has been significant; compared with Afghanistan, for instance, the amount spent on Bosnia and Kosovo has been, to put it diplomatically, quite generous. While money continues to flood into Iraq from the US, the needs of Afghanistan's reconstruction have been ignored by the international community but particularly by the US government. Former US Ambassador to Afghanistan (2002-03), Robert P. Finn, laments US policy: "I said it from the get-go that we didn't have enough money and we didn't have enough people . . . I'm saying the same thing six years later."36 At the Tokyo Donors Conference for Afghanistan, for example, the international community pledged just $64 per person, while aid to Rwanda, East Timor, Kosovo, and Bosnia received, on average, about $250 per person and giving to some countries exceeded even this amount.37

16 Finally, location affects more than just travel time and the desire to provide funding. It also impacts the most important difference between the Balkans and failed states in the Middle East: the role of identity, both national and religious, and specifically how national groups see themselves vis-à-vis foreign occupying countries. As much as Westerners might want to distance themselves from the horrors of the ethnic nationalism in Eastern Europe, nationalism, and even the violent kind, has been a defining feature of European history. Bosnians, Croats, and Serbs have always seen themselves as Europeans and part of the Western enlightenment tradition. Perhaps even more so than Poles and Hungarians, who were in the firm grasp of the Soviet Union, the Balkan nations were not part of the Soviet controlled Eastern bloc; thanks to Josip Tito, Yugoslavia was a founding member and leader of the nonaligned movement starting in 1961.

17 During the Cold War, Balkan nations had more contact with the West than any of the other socialist countries. This European, rather than Balkan identity, was apparent in the more liberal voices that emerged in the late 1980s but were silenced by nationalist war-mongering.38 Some Afghan and Iraqi leaders have a pro-American or Western orientation, but they do not reflect or represent a sizeable part of the population, who feels that it has been isolated from its history, heritage, or culture. That is to say, there is no notion of a "return to Europe" because Europe and the West are not part of the national identity. In fact, identities in the Middle East have been shaped in opposition to the West or completely separate from it.39

The Balkans and Selective Learning

18 In many ways, stabilization and reconstruction in the Balkans were an easy test case, and the international community should have had little problem putting these countries back together. Yet, they did have many problems, and numerous analyses were produced, both critical and complementary, in an effort to improve future policies.40 It appears that the Bush administration gave little thought to the particularities of the Balkans or learned from the achievements or pitfalls of international involvement there, even as it embarked on what many argued would be similar military engagements in Afghanistan or Iraq. Instead, doctrinal unilateralism held sway, the administration maintained in its words or deeds that: first, stabilization and post-conflict reconstruction were not only possible but would be easy; second, military force was an effective tool of US foreign policy; third, American unilateral actions were sufficient and support from allies was nice but not necessary; and finally, American values were shared global values. As this section demonstrates, these assertions were total falsehoods, and America-led efforts in Bosnia and Kosovo soundly contradicted each of these myths.

The Mixed History of Nation-Building

19 There is a significant consensus on this one point: nation-building or external attempts to promote stable democracies are rarely successful. "Historically, nation building attempts by outside powers are notable mainly for their bitter disappointments, not their triumphs."41 Although scholars calculate that only 16 out of more than 200 (or roughly eight percent) of all American military interventions from 1900-2003, have been actual attempts at nation-building, the success rate is still mixed at best.42 In fact, of the cases Minxin Pei and Sara Kasper examine, only two are considered unambiguous success stories, Japan (1945-52) and West Germany (1945-49).43 The authors characterize the remaining 11 cases as failures because, 10 years after the departure of American forces, the country was not democratic.

20 Conrad C. Crane, director of the US Army Military History Institute at the US Army War College, conducted similar research and arrived at nearly the same conclusions. His unflinching evaluation of the military's record demonstrates that military academics have clearly and objectively acknowledged the failures of the past as well as the fundamental difference, as he puts it, between "draining swamps and transplanting values."44 Although the military can do the former, it rarely has accomplished the latter. When the military has been successful;, like in Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Germany;, it was due to a combination of good planning, luck, and patience. Even in these so-called successful cases, Crane is clear to limit himself to analyzing the military's role in stabilization, noting that history shows a consistent pattern of military effectiveness in these areas — when properly motivated and resourced. But stability or "draining swamps" is quite different from transplanting values and bringing the hope of democracy, development, and free trade. The bottom line is clear if unfortunate: the US military can provide security with restraint and perseverance, but it cannot instill values.

21 This conventional wisdom notwithstanding, it did not appear to influence the Bush administration's thinking or behavior as it planned the invasions of Afghanistan or Iraq. In fact, in both cases the administration tried as hard as it could to downplay any problems, resisting efforts to create ambitious, long-term projects in either Afghanistan or Iraq. The administration's optimism shortly after the US intervened in Iraq bordered on cheeky as Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld delivered his now infamous "dead ender" speech.45 As is now well-known, however, Rumsfeld could not have been more wrong. Perhaps his confidence was the result of ignorance or active disinterest in potential complications. A 2005 Rand Corporation study concluded that, among the top leaders of the administration, post-conflict stabilization and reconstruction were addressed only very generally, largely because the prevailing view was that the task would not be difficult.46

22 In the Pentagon, as the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance was being haphazardly set up by Jay Garner, few seemed alarmed by the administration's lack of preparation or planning because of the steadfast conviction that, when the war ended, the Iraqi civil servants would return to work and the ministries would run themselves; "the assumption was that the best-case scenario would prevail."47 With this said, this particular Pentagon office did not enjoy either the support or input of military officers, many with years of post-conflict and reconstruction experience. As a former member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff explained, under Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld and especially when it came to Iraq, military advice was compromised by political leadership.48 Experts working outside the Pentagon on these issues, such as Robert Perito (and James Dobbins), were initially asked to comment on the rebuilding of Iraq because of their knowledge and experiences in the Balkans and elsewhere. After commenting that the administration needed to plan for the possibility of high levels of violence in the first two years, Perito was thanked but was never contacted by the Pentagon again.49

23 At this point, it is worthwhile to add that American-led efforts in the Balkans were neither easy nor wholly successful. It is true that not a single foreign soldier has been killed in combat in Bosnia and calm has been evident for more than a decade, yet both reconstruction and genuine democracy have been, at best, slow and tenuous. Unemployment remains at about 45 percent and about a quarter of the country remains in poverty. Important achievements aside, Bosnia remains highly fragile. It is even more of a stretch to refer to Kosovo as a relative success story, given the words used to describe the difficult Kosovo stalemate and the possible collapse of international negotiations on its future status.50 The International Crisis Group (ICG) warns that inaction on the part of the international community risks "a new bloody and destablising conflict."51 Given the country's recent declaration of independence and the continuing activity of radical elements, it is still unclear whether Kosovo will be regarded as a successful case of reconstruction, a failure, or like Bosnia, something in between.

Force is Only Part of the Solution

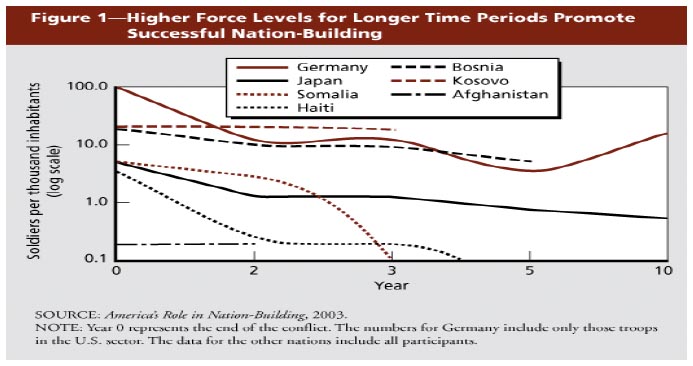

24 As the saying goes, if the only tool you have is a hammer, then every problem starts to look like a nail. Given US military supremacy, it is perhaps not surprising that military force has been given such priority in addressing failed states today. This opinion, however, has distorted three of the most important take-home points of the Balkan experience. First, although the US military is technologically the most advanced military it in the world, it was not technology that made the NATO-led international force so effective in Bosnia; it was instead "boots on the ground" or the large number of grounds troops that allowed NATO-led troops to accomplish the military mission in a matter of months. Rather than admitting this, the administration, pushed by the Secretary of Defense, emphasized America's technological edge and its ability to wage wars from the air. Finally, we should not forget how large the international force was in Bosnia. In the first year after the violence ended, there were some 60,000 foreign troops in Bosnia, though in subsequent years the number dropped to about 20,000. 52 In Kosovo, some 50,000 troops flooded a region that was less than half the size of Bosnia. When compared with other American-led nation-building exercises, Bosnia and Kosovo had more troops per 1,000 inhabitants than were in Germany, Japan, and certainly in Afghanistan. The following figure is taken from the Rand Corporation's research on American-led nation-building. It provides a visual depiction of the force levels in a comparative context. Note that the only country with higher force levels at the beginning phase of the intervention was Germany (though, by year three, Bosnia was on par with Germany, while high-force levels per capital were already evident in Kosovo).

Figure 1 - Higher Force Levels for Longer Time Periods Promote Successful Nation Building

Display large image of Figure 1

25 IFOR (Implementation Force) and then SFOR(Stabilization Force)'s ability to overwhelm and deter the three separate armies in Bosnia as well as the numerous militia groups was the first and most important step toward the re-creation of the Bosnian state. By stopping the violence and demilitarizing the population within a matter of months, Bosnian leaders in Sarajevo could claim to be, and were perceived as, the legitimate rulers of the country – and all else could follow. KFOR (Kosovo Force) was similarly successful at this early stage. As is discussed in numerous places, the discussion of, and eventual deployment of, troops in Afghanistan and Iraq has not been sufficient. In Iraq in particular, the necessary troop levels were hotly debated and where the lessons of Bosnia crept in, at least for the US Army chief of staff, General Eric Shinseki, and the retired US Army Major-General William Nash (among others in the military) who testified that, based on the Bosnia experience, somewhere between 250,000 and 400,000 troops would be necessary for the first stage of intervention.53 Disregarding military minds and Balkan lessons, some 100,000 troops launched the Iraqi invasion, with far fewer available for post-conflict stabilization and construction.

26 Even if one acknowledges the significant differences between the military forces demanded in Bosnia and the large number of troops that were deployed, this misses another crucial point; force was never the sole or even primary strategy in the Balkans. Other forms of influence were exercised simultaneously by the international community. Military force, indeed, played a crucial role in stopping and deterring violence, but the military solution was but a part of a more comprehensive, multi-level approach to reconstruction in the Balkans, which also entailed restructuring Bosnian institutions of governance and the promotion of grassroots democracy and civil society.

27 The civilian side of peace-building in Kosovo was, even more so, a multi-pronged endeavor that included an array of governments and intergovernmental organizations. In addition to top-down and official ways of stabilizing and reconstructing Kosovo, significant time and money went to bottom-up efforts to foster democracy and civil society.54 Although heavily debated, the net effect of these other strategies and the use of softer forms of power have been the empowerment of individuals, particularly those from traditionally marginalized groups like women and minorities, as well as the development of scores of local organizations committed to economic and social development, women's rights, and education.

28 It is worth noting that early on in the reconstruction of Bosnia it was recognized that not nearly enough attention was given to the civilian side of these operations, which were more complicated and ultimately less successful than the military operations. This recognition shaped international involvement in Kosovo, but this knowledge had little staying power, at least within in the US. 55 In 1996, President Bill Clinton called for what later became the Presidential Decision Directive 56 (signed in 1997) to improve the country's responses to complex contingency operations. It was designed to ensure that the lessons learned would be incorporated into the interagency process on a regular basis.56 Although the Clinton administration did little to implement this directive, the Bush administration ignored it completely, and there were few attempts to develop civilian capacity in this area.57 On the eve of the Iraqi intervention, the civilian side of post-conflict reconstruction was, unfortunately, quite deficient.58

29 Finally, blind faith in the efficacy of military force ignores the most fundamental reason why NATO-led troops were effective in the Balkans: they were seen as neutral parties and not an occupying force. This is not to suggest that the Serbs did not resent the presence of NATO-led troops – given Russia's involvement, it was tolerable – but merely thinking that boots on the ground are the solution disregards the importance of perception and public opinion. By the time the US military had some freedom of movement and tried to implement one of the Balkan lessons learned, it was already too late and the presence of more troops was counterproductive.59

The Illusion of Unilateralism

30 One of the most criticized aspects of the Bush administration has been its attitude toward other countries, particularly its European allies.60 Regardless of whether the current administration actually discounts the opinions of countries, the perception of many around the world is that the US does not take into consideration the opinions of other countries, even its allies.61 And although the US can easily go it alone when it comes to launching military strikes, it simply cannot — and does not — work alone when it comes time to cleaning up the mess and putting countries back together. This fact has been evidenced clearly in the reconstruction of Bosnia and Kosovo, as has the important role of the United Nations.

31 It may be fair to characterize the military effort in Bosnia and Kosovo as US-led, but it is plain wrong to suggest that reconstruction and development in either place have been dominated by the US. In reality, peace-building in the Balkans has been a multilateral and multi-leveled effort. United Nations mandates for the reconstruction of Bosnia and Kosovo have meant that these efforts have drawn on the extensive resources, field capabilities, and wealth of expertise of the UN offices, as well as numerous governments, regional organizations, and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs). 62

32 The presence and importance of numerous players was apparent in the international military forces that were assembled for both missions. IFOR in Bosnia was a 36-nation coalition of NATO and non-NATO countries, while KFOR consisted of 39 NATO and non-NATO countries.63 With every year, the number of US troops, compared with troops from Europe, declined; in 2003, some 12,000 foreign troops remained in Bosnia, while fewer than 2,000 were from the US.64 In late 2004, the US marked the end of its nine-year peacekeeping mission, turning over the command of foreign troops to the European Union Force (EUFOR). As of early 2008, some 7,000 troops from 33 countries, mostly from Europe, remain in Bosnia. As of the spring of 2007, there were 16,000 troops in Kosovo, with the US providing just 3,000.

33 Meanwhile, the need for long-term stability and reconstruction in Bosnia has pushed the European Union to adopt a more assertive foreign policy. By 1998, it was not only coordinating international assistance for the country's reconstruction but also had developed the Balkan Stability Pact, demonstrating the EU's move into security affairs and its reliance on multiple organizations to reconstruct the region. By 2004, both the EU and NATO were dangling membership before Bosnia to promote regional stability and development. If Bosnia marked the EU's debut in peace-building, its involvement in Kosovo made it a central player. The March 2007 Ahtisaari Report highlights the leading role the EU should play in Kosovo's future. 65 The ICG, similarly, emphasized that despite Washington's tough talk with the Serbs about Kosovo's independence, it has not adopted the same tone with Moscow because it essentially expects Europe to be the leader on this international problem.66

34 The Balkan experience is testament to the importance of multilateral cooperation, overlapping missions, and mutually reinforcing messages. Yet, as the Bush administration planned invasions and reconstruction elsewhere, it ignored these lessons. In Afghanistan, it cajoled its allies to get involved but, shortly after the war ended, disputes among the allies emerged because of US attention to fighting terrorism rather than focusing on reconstruction and development — to the dismay of its European friends.67 As is well-documented, the invasion of Iraq was far more acrimonious and the US not only did not have the support of the UN and most of its allies but the so-called "coalition of the willing," the 49 willing countries that initially became involved in the American-led effort in Iraq totalling fewer than 24,000 troops (less than 10 percent of the total).68 Even within the US government, cooperation and coordination among different agencies just did not happen; instead, the Pentagon, alone and isolated, adopted and implemented a strikingly unilateral plan that relied almost entirely on the Department of Defense for the invasion and reconstruction of Iraq.69

American Values

35 In discussing the US foreign policy, especially as it relates to failed states, the Bush administration has maintained, that "American values are universal."70 In some cases, this may be true, but in others, it is abundantly clear that American or Western values and institutions are neither feasible nor prudent for states emerging from conflict or collapse. As Francis Fukuyama observes, the United States is bad at nation-building not only because Americans have an anti-state culture and are opposed to large bureaucracies but because its leaders do not admit to the contradictions of their own policies. 71 Americans fail to acknowledge that state-building and democracy promotion, while two key foreign-policy concerns for the US, tend to work at cross purposes, and it is almost impossible to rebuild or strengthen a state while, at the same time, democracy is consolidated. In fact, the history of western political development suggests that the building of states and democracy taking hold are usually separated by hundreds of years. Overcoming or mitigating such contradictions requires, above all, some recognition of this fact.

36 One of the biggest obstacles to democracy and self-sustaining peace in Bosnia has been the institutional structure created by the Dayton Peace Accords. Designed at a difficult historical moment, the peace treaty essentially created a weak federal structure that divided the country while it kept it together. In practice, this left the country separated into two monoethnic units while numerous top-down and bottom-up mechanisms were adopted to reunify the country. The elections in September 1996 pushed by the US and heralded as a great success, merely reinforced, if not strengthened, the position of nationalists. For years after, the country was at a stalemate as politicians continued their struggle in others ways, albeit without violence. For more than a decade since, only international will, the presence of foreign troops, and lots of financial assistance have been able to mitigate these artificial institutional divisions and the federal state's weakness and maintain the country's fragile existence.72

37 This problematic institutional solution was the result of many factors but was influenced significantly by American attitudes and assumptions about world politics. Bosnia, in fact, represents "the dominant approach to nation-building," which consists of: international support for a settlement between warring parties; help in setting up a country's governing structures; and economic assistance to restructure the state, financial institutions, and civil society.73 However, underpinning each of these strategies is what Roland Paris refers to as "a liberal internationalist world view" or the assumption that future states will look like secular, democratic states in the West.74 Such assumptions remain as the United States and the international community responds to other failed states and continues to engage in peace-building. In practice, this means that failed states – regardless of their history, realities on the ground, and the resources available – must not only be rebuilt, but they must be democratic, multiethnic, and secular.

CONCLUSION: EVEN MORE LESSONS FROM THE BALKANS

38 International involvement in the Balkans, as useful and important as it has been to saving lives and restoring peace in this region, has not led American leaders to learn from these experiences or to improve their strategies toward other failed states. This is not because no one understood or analyzed the achievements and shortcomings of these efforts; on the contrary, many individuals learned and potentially useful institutions and mechanisms were created to document the lessons learned and to improve post-conflict reconstruction. However, as I demonstrated, the ideological beliefs of the President and his senior advisors were more important, ultimately distorting the 'take-home' points of the Balkan experience and subsequent policies toward other failed states. To summarize, the Balkans demonstrated that stabilization and reconstruction were difficult, time-consuming tasks; coercive military force alone was not sufficient for peace-building; multilateralism was crucial to the success of these missions; and finally, American or Western liberal values and institutions are sometimes self-defeating, especially when they are forced on a country. Unfortunately, these lessons did not conform to the president's view of the world or how the US should execute its foreign policies.

39 The current environment in the Balkans, moreover, provides additional insight that should be considered by the US and other members of the international community as the world continues to engage and assist failed states elsewhere. First, there is a fundamental difference between state-building and nation-building and decision-makers should try to identify (and remember) which goals they seek: reconciling and unifying a nation or strengthening and rebuilding a state? The international community can and has helped strengthen and rebuild states, but this is quite different from nation-building or fostering a community of people who feel like they belong together. As others have noted, nation-building is not just a physical, technical process but is also a psychological one and a process which external actors have little influence.75 Bosnia and Kosovo are no exception, and while both states now exist on the map, they do so only because of the support from the international community. The economic, military, and psychological support from the international community has, indeed, strengthened these political units, but it has done quite little to foment a Bosnian or Kosovar nation.

40 Second, the Balkans today remind us that although states matter a great deal so too do neighborhoods and the network of institutions and organizations that transcends borders. More porous borders in Europe have allowed supranational bodies, regional organizations, and NGO to supplement and support states and international efforts in the Balkans. Thus, the neighborhood effect has been largely a positive factor in these countries' development. Even the Serbs are showing signs that they are vulnerable to the lure of the EU and the carrots of Western governments and other regional organizations. In Afghanistan and Iraq, the neighborhood may, however, prove to be as challenging as the threats emanating from within these states.

41 Third, the evolving reconstruction of Bosnia and Kosovo demonstrate clearly Europe's more assertive role in the world, but they also hint at the significant changes in global governance that are underway. These changes are evidenced by the way governments behave toward each other, intergovernmental organizations, and nongovernmental organizations . For more than a decade, the Balkans have been host to hundreds of regional organizations and international NGOs that have been involved in almost every aspect of reconstruction and development. In this region, non-state actors have, for the most part, helped strengthen states and furthered the international mission. Elsewhere, we cannot assume that these agents will play the same role. In Afghanistan, for example, President Karzai has been openly critical of international NGOs, claiming that these actors are taking away money from the Afghan state by creating unnecessary parallel structures. Thus, peace-building efforts in the Balkans provide a window into what may be a transnational network of public and private actors that relies on similar strategies and assumptions to promote peace and stability.76 At the same time, there is no reason why transnational networks are inherently good, and public and private actors could emerge elsewhere that are bent on fomenting violence and instability.

42 The final take-home lesson of the Balkans is the need for more pragmatism when it comes to responding to failed states and reconstructing them. We should not forget that politics and ideology will always intervene between historical experiences and policies. In some cases, ideology will triumph and some, if not all, of the lessons that should have been learned from historical achievements or failures, will be lost.

43 Almost twelve years in the Balkans, six in Afghanistan, and four in Iraq should have resulted in some genuine foreign policy learning and yielded better policies; unfortunately, for the US, this has not been the case.

Patrice C. McMahon is an Associate Professor at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

Endnotes