Articles

What Is Known and Not Known About Palestinian Intifada Terrorism:

The Criteria for Success

Richard J. ChasdiCenter for Peace and Conflict Studies at Wayne State University

Abstract

This article employs three "success criteria" – Dimensionality, Temporality, and Locus of Success – to assess the achievements of Palestinian terrorism during the al-Aqsa Intifada. Dimensionality refers to recognizable manifestations of recognition (political-social success), organization, and military achievement. Temporality gauges the achievements of terrorist campaigns or sets of events on a time continuum: the long haul, the medium term, and the short run. Locus of success addresses the basic question: success for whom? In the period prior to the First Intifada, Palestinian terrorism achieved recognition but little else apart from strengthening the Palestinian-Arab terrorist organizations politically and financially, in part at the expense of broader-based Palestinian-Arab „insider‟ interests. The First Intifada presents a somewhat different picture than the earlier period. In the case of dimensionality, recognition of the legitimacy of the Palestinian struggle was enhanced and there was rapid expansion of organizational structures but the military success criterion remained underdeveloped. The single, most significant achievement of the First Intifada at the organizational level may have been the development of internal infrastructure in the Occupied Territories with an enormous capacity to keep a general movement thriving in an effective and sustained way. The al-Aqsa Intifada presents a different picture. First, by showing that they were willing to kill and be killed for the sake of the movement, it illuminated the depth of the Palestinians‟ commitment. Second, the Palestinians‟ resort to terrorist attacks on Israeli settlements and into Israel proper during the second Intifada, and especially the increasing use of „suicide bombers,‟ represented a profound and lasting change in strategy from the „limited force‟ approach that characterized the first uprising. These attacks generated and sustained fear among Israelis which, in turn, increased pressure on the political elite for political change. Perhaps the single, most significant success in this respect was the removal of Israeli settlers from the Gaza Strip in 2005. However, the al-Aqsa Intifada does not seem to have achieved any other macro-political goals, such as serious reconsideration on the part of the Israeli elite of the status of the West Bank, including Jerusalem. Nor has it solved the familiar set of Palestinian-Arab internal problems that include corruption and the development of aspects of „civil society.‟ A key question is what to do with Hamas, the group which is now the de facto „government‟ of Gaza but is simply not committed to the notion of a „two state solution.‟ Finally, the al-Aaqsa Intifada highlights the transition of the national liberation struggle from a condition of successes and failures to the point where the emerging reality is a nation-state-in-the-making that comes complete with a system of „representative democracy,‟ including independent institutions that thrive in effective and sustained ways.INTRODUCTION

1 In the wake of the 11 September 2001 attacks and the London bombings of 2005, one underlying question about terrorism, posed by the public and policy makers alike, revolves around the central question of whether or not terrorism is successful, and if so, under what conditions. The purpose of this article is to address that question by exploring the case of contemporary Palestinian terrorism during three time frames of their nationalist struggle. The three periods are: the 1960s and 1970s; the First Intifada, that began on 8 December 1987 and which began to fade during the Gulf War (1990-91); and the ensuing fierce struggle during the al-Aqsa Intifada that began with then Knesset member of parliament Ariel Sharon‟s walk to the Temple Mount (or Haram al-Sharif, as it is also known) on 28 September 2000.1

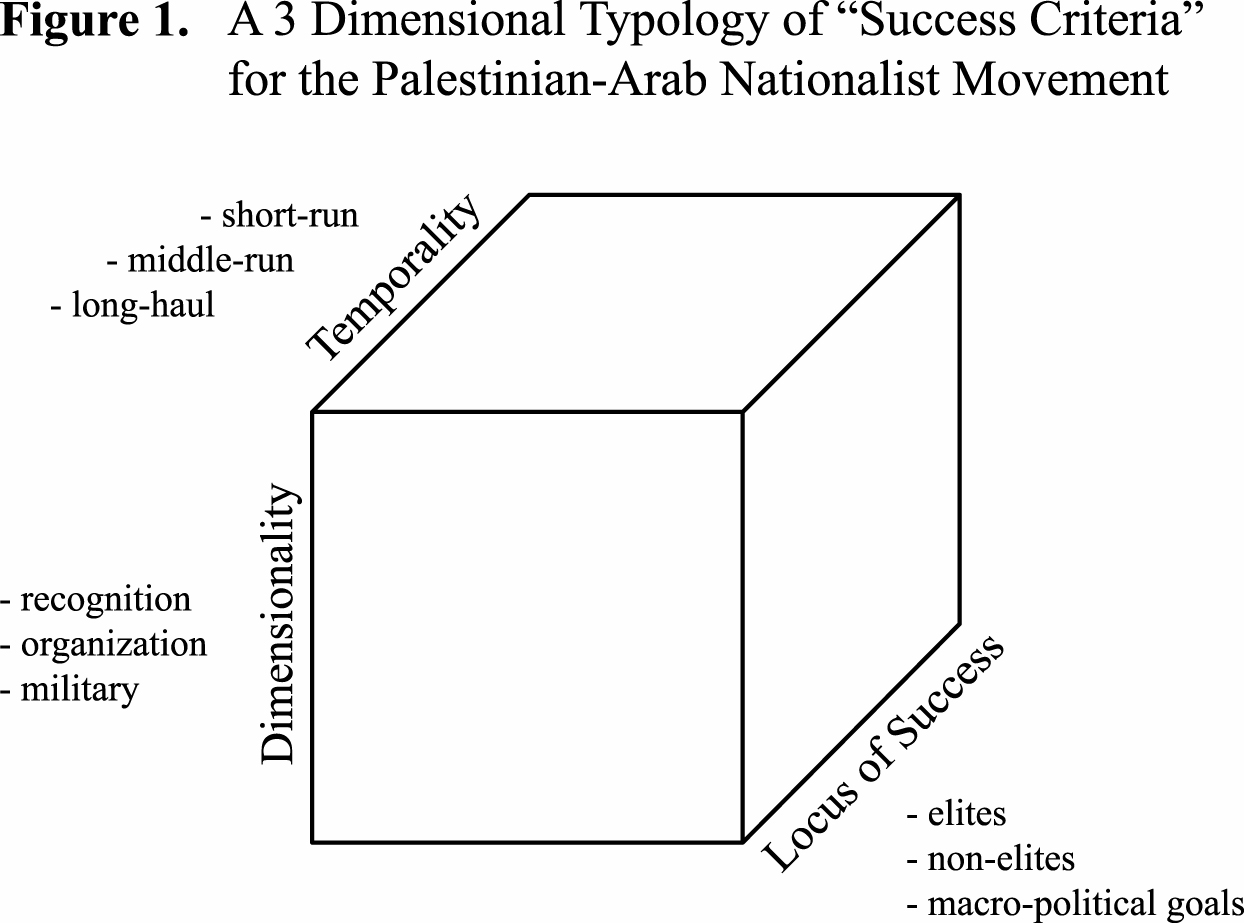

2 From the start, it is critical to clarify the concept of "success criteria" used for analysis here. This article employs three success criteria: "Dimensionality," "Temporality," and "Locus of Success."2 The notion of dimensionality refers to the empirical or „existential‟ quality or manifestations of generally recognizable thresholds: recognition (i.e., political-social success), organization, and military achievement. For example, it is possible to observe the growth of recognition of the Palestinian struggle between the time of former Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir‟s famous 1969 remark that "there is no such thing as a Palestinian people . . . ." to the point when Palestinian terrorist organizations become important non-state actors in the political process, and the present when the term "Palestine" is used in the common discourse even though no nation-state of Palestine presently exists.3

3 In turn, temporality gauges the accomplishment of terrorist campaigns or sets of events along a time continuum, namely the short-, medium- and long- terms. One very important question to consider, when thinking about or defining success in this context, is whether or not terrorism works or works in the same ways during different stages of the post-attack environment. For example, it seems clear that even when terrorism works in the short run, by yielding changes both in public perception and government response, which – along the lines of Robert Dahl‟s definition of power – represents the power of terrorism, these changes can be almost diametrically different in effect. The cases of the Madrid bombings prior to the electoral defeat of Prime Minister Jose Marie Aznar in 2004, and the bombings in London in 2005 illustrate this in stark relief.4 To compound the matter even more, isolating and identifying discernible effects of terrorist attacks, especially beyond the short-term, becomes even more complex.

4 Lastly, the criterion locus of success addresses the fundamental issue that really distills down to the basic question: success for whom? In other words, what is the success rate with respect to the capacity of terrorist leaders or activists to deliver? One way of thinking about the matter is to examine whether sets of successful terrorist attacks – defined in terms of achieving "macro-political goals" – are deemed to be successful outside of elite levels of terrorist leadership. In other words, do terrorist attacks provide a set of net benefits that exceed costs for non-elite players found among more „grass-roots‟ segments of society, or even in other elite groups, such as educators, leaders of business associations, and others that comprise the higher echelons of society (see Figure 1).5

Figure. 1 A Three Dimensional Typeology of "Success Criteria" for the Palestinian-Arab Nationalist MovementPRELUDE TO THE FIRST INTIFADA

5 At first blush, an examination of the pre-Intifada period of the Palestinian struggle, with special emphasis on dynamics and events from the 1960s into the 1970s, presents several departure points for discussion about the fundamental nature of the successfulness of terrorism. One underlying theme of their campaign at this juncture revolved around the pursuit of a more generally recognizable legitimacy in the eyes of the world community with respect to the stature of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and, in the broader sense, Palestinian nationalism itself as a cause celebre. Yezidh Sayigh seems to be on the mark when he tells us to place the First Intifada and, by extrapolation, events beforehand, within the context of the "Great Revolt" of 1936, and hence not to characterize the Intifada as a historical anomaly. But what seems significant here is the „existential‟ component or quality of dimensionality that, undoubtedly, grew apace with al-Nakbah ("the Catastrophe") of 1947-48 and the Six Day War of 1967.6

Success Criterion 1: Dimensionality: Recognition, Organization, and Military Achievement

6 The goal of working to acquire overall recognition for a fledgling national movement seems to be a good fit with the underlying objective of terrorist attacks under certain select circumstances. In essence, as Bruce Hoffman suggests, the underlying aim of terrorism is to generate and sustain abject fear among the target population, thereby in effect helping to put pressure on the ruling elite to make structural political and economic change.7 It is not too hard to picture a situation where a political cause is somehow denigrated or otherwise not taken seriously by political leaders and policy makers in ways that reflect time-honored and long-standing "North-South" relations and divisions. In national movements among „nations,‟ persons are inextricably bound together by what Milton Esman suggests are the characteristics of ethnicity, which include, but are not necessarily limited to, shared historical legacy, religion, language, ritual, and shared visions of the future.8 Compounding the matter even more, the concept of „self- determination‟ as a sacrosanct concept has become even more robust since the end of the Second World War. Acute belief in the capacity of groups of persons to determine their political future seems to resonate in powerful ways, especially if the concept of self-determination, as Detter De Lupis tells us, is gauged to be a fragile jus cogens right codified in the Charter of the United Nations and susceptible to damage caused by the geopolitical considerations of others.9

7 To be sure, terrorism is a method of conflict and in many cases, as an integral component of war, it has the capacity to generate and sustain enormous „ripple effects.‟10 In the case of the Palestinian struggle, many writers have pointed out how technological developments, such as television and other forms of communication, have become instruments or modalities of what Brian Jenkins calls a "force multiplier effect." Plainly, that effect has important ramifications for dimensionality.11 By means of television, as well as the print media, for example, „spectacular‟ terrorist attacks, such as the nearly simultaneous Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) assaults that resulted in the destruction of American, British, and Swiss jet airliners in Jordan in 1970, and the massacre of Israeli athletes by Black September terrorists at the 1972 Olympic Games, illuminated the dynamics of terrorism‟s „force multiplier effects.‟ As such, this first component of dimensionality, namely political-social achievement, was a success for the Palestinian-Arab terrorist campaign.

8 Conversely, while such terrorist attacks had success with respect to the political-social components of dimensionality, it is probably fair to say that the PLO and the broader phenomenon of Palestinian nationalism, did not succeed militarily, at least beyond the short run. Nor did the episodic and inconsistent bursts of terrorism succeed in organizational terms, if by organizational we mean to describe the rudimentary structures of socio-economic development or aspects of „civil society.‟ Seen from the vantage of the locus of success criterion, macro-political goals, such as the removal of Israeli military forces from the Occupied Territories, let alone substantive far-reaching progress toward an independent Palestinian state, were not achieved. Of course, Joshua Teitelbaum and Joseph Kostiner point out that those macro-political goals would not be achieved even during the First Intifada.12 What did happen was that terrorism conducted on a stage of world-wide proportions introduced to many the essence of Palestinian political demands and aspirations, thereby in effect helping to craft a recognition factor that was an essential first step in the contemporary Palestinian-Arab political struggle.

9 With that in mind, it is crucial to recognize that in many cases, more immediate „hands-on‟ actors „on the ground,‟ such as terrorist leaders, profit both in political and economic ways from the continuation of terrorist attacks. At a substantive level, they often do little to stop terrorist attacks precisely because they benefit from terrorism. Clearly, that set of dynamics, which reverberates with often calamitous results for ordinary people, are not limited to the Palestinian nationalist struggle. For example, attempts were made to assassinate Special Envoy Oleg Lobov and General Anatoly Romanov, who served as negotiators for Russian President Boris Yeltsin in his fierce struggle with the remnants of Dzokhar Dudayev‟s Chechen regime. Some interpretations of those events pointed blame at either the Russian military, which would suffer as a result of the end of hostilities, or supporters of former Chechen President Dudayev, such as Shamil Basayev.13 Plainly, in the broader sense, most Chechens, and by extension those who were victims of terrorist attacks or of Russian counter-terror offensives in other Russian republics, such as Dagestan or Ingushetia, did not benefit from the Chechen military struggle; rather they suffered calamitous loss.

10 In the Palestinian case, much of the „success‟ of their elites seemed to presuppose and derive from the absence or the poorly developed nature of other more legitimate opportunity structures for articulation of Palestinian demands and aspirations. To be sure, this can be the result of an interactive effect between those who oppose a regime, in this case the Israeli government, and the counter-insurgency strategy and tactics of that government. For example, Ann Mosely Lesch and Teitelbaum and Kostiner tell us that the Palestine National Front (PNF) "while being linked to the PLO," in Lesch‟s words, made forays into the diplomatic realm with its advocacy of a "two-state solution," but was decimated by Israeli arrests of PNF members.14 What seems significant here for the analysis of success criteria overall is that the PLO elite, as Teitelbaum and Kostiner inform us, seemingly understood the importance of this next phase of dimensionality that revolved around crafting at least the rudiments of organizational infrastructure for Palestinian-Arab „insiders.‟ Indeed, both Teitelbaum and Kostiner, and Robert Hunter suggest that such efforts were done with almost singular focus to ensure that the PLO would remain inextricably bound up within the peace settlement process.15

11 Another crucial point Teitelbaum and Kostiner allude to is the role of exogenous factors with respect to acceleration or restriction of success criteria in the broader sense. In their work, they suggest that the 1973 October War was a watershed event and, by extrapolation, an exogenous variable that helped to encourage PLO thinking about a "two-state solution," rather than continuing to pursue the maximalist position, which envisioned taking control of all Israeli territory beyond the "Green Line."16 For the authors, such an epiphany, that in part derived from the Israel Defense Force's (IDF) military victory, as well as the efforts of US President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to negotiate a solution after the war, in effect helped to lead to an increased emphasis on the development of PLO-associated infrastructure in the West Bank.17 At the heart of the matter, their observations have critical and fundamental implications for the construction of a three-dimensional success criteria typology that can be applied to different time frames of the Palestinian-Arab struggle.

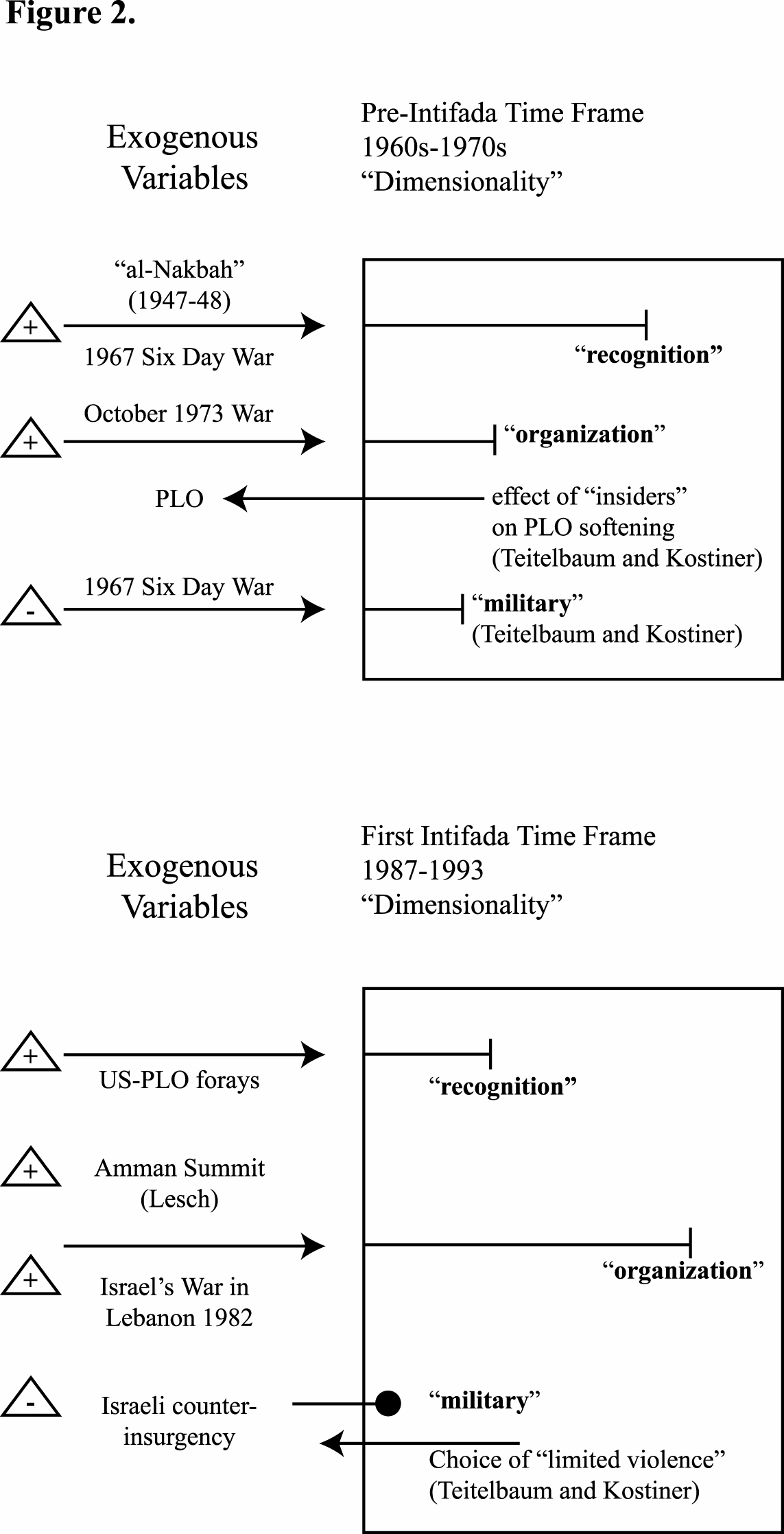

12 In the section that follows, the dynamics for dimensionality are charted for the three periods of the Palestinian-Arab nationalist struggle identified earlier. For the purposes of this article, each of the success variables will be charted for each of the three time frames, although the dimension of temporality will remain incomplete for some time frames because of absence of more definitive data. We first examine dimensionality in the pre-1987 time frame. In this period the 1973 war is posited as an exogenous variable that helped to accelerate the growth of the organizational element of dimensionality.

13 Clearly, wars prior to and at the start of al-Nakbah, and especially the Six Day War, were exogenous variables that contributed to a large increase in recognition. In particular, it was as a result of the Six Day War that the Occupied Territories became the new reality. It follows that the 1967 war can also be posited as an exogenous variable that contributed to the decrease of military accomplishment during the 1967-73 period. The catastrophe of that war destroyed Egyptian President Nasser„s carefully crafted mantle of authority in the Middle East and also contributed to in-fighting among terrorist groups.

14 What also seems significant here is the arrow in Figure 2, following Teitelbaum and Kostiner‟s reasoning, that points outward from within the parameters of that plane of dimensionality. It signals the endogenous „moderating effects‟ of Palestinian-Arab „insiders‟ on the existential or zero-sum quality of extremist PLO ideology. Those effects pitted the interests of PLO „insiders,‟ who had a more pragmatic view of the conflict, against PLO „outsiders‟, first living in Jordan, then in Lebanon, and then in Tunisia (see Figure 2).18 It is probably fair to say that those fiercely competing visions of a Palestinian future helped to slow the growth of the organizational component of dimensionality in this pre-Intifada time frame.

Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

15 With respect to the organizational element of dimensionality, Teitelbaum and Kostiner explain that the PLO helped to craft both the PNF (1973-77) and its successor, the National Guidance Committee (1978-82) during this period, after acknowledging at the 10th Palestinian National Council (PNC) summit in 1972 the importance of some type of Palestinian „insider‟ infrastructure.19 In essence, this micro case study seems to demonstrate that one element of dimensionality – in this case recognition – can grow quickly. However, it might not produce a widely shared consensus among the international community in favor of an independent Palestinian state before dynamics associated with other elements, such as organization, manifested themselves.20 What is noteworthy for this time period is the absence of any meaningful military achievement.21 As noted earlier, the Six Day War may be the single, most predominant exogenous explanatory variable that explains why this is the case.

Success Criterion 2: Temporality - Short Run, Middle Run, and Long Haul

16 This brings us to the challenge of trying to measure the success of Palestinian terrorism during the pre-Intifada era along the dimension of temporality (the continuum of short-, middle-, and long-term time frames) in order to gauge the effect of terrorist attacks on human behavior. If we apply Dahl‟s definition of power – that "A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do" – one critical matter to explore is whether or not terrorist spectaculars as well as more pedestrian terrorist attacks altered behavior past the short-run and into the long haul.22

17 The question plainly revolves around the types of political, social, and juridical change that followed terrorist attacks, and equally important around those types of changes that happened outside the elite levels of society. In the case of long-term effects, it was during this period that one can identify underlying changes in both domestic and international law, and in public policy administration (for example, at specific public facilities, such as airports) to offset any political or military gains made by terrorists. For example, in the realm of international law it is clear that enactment of the Hague and Montreal conventions on violence directed against civil aviation was related to the terrorism, much of it Palestinian-Arab, that took place around that time.23 In addition, the establishment of the German GSG-9 anti-terrorist team arose from the 1972 Olympic Games massacre. In fact, as previously mentioned, terrorist attacks like the Olympic massacre and the multiple hijackings of airliners to Dawson Field in Jordan in 1970 undoubtedly had short-term success. The effects that those assaults most likely had on political leadership, public policymakers, the airline and tourism industries with respect to certain countries, serve as good examples of the power that terrorism has – at least in the short-term – to influence certain parties to act in ways they would not ordinarily act.24

18 Notwithstanding the legal and national security changes noted above, the effect of such attacks, individually or collectively, is much more questionable, in my judgment, in middle- and long-term time frames. However, some effect is probably evident within those periods, given the context of these events as harbingers of things to come, which spills over into appraisals of the future. Clearly, one set of hypotheses to explore empirically revolves around whether or not the effect of a terrorist action or a specified series of actions, having been utilized regularly, declines over time. At first blush, it seems that full blown terrorist campaigns, such as that of the Palestinians during this time, have been effective in terms of middle to long-haul temporality, in contrast to the effects of episodic and inconsistent terrorist assaults.

19 Put another way, the fundamental question is whether or not such attacks altered human behavior in more profound and lasting ways at a „grass-roots‟ level, over and above modifying government apparatus and changing the behavior of the immediate victims and their families. In the broader sense, such effects may be context specific, namely the result of interactive dynamics between terrorist events and counter-terror operations or strategic points of view that in the narrower sense either fit well with respect to survivor demands and aspirations or do not. While description and discussion of this clearly falls beyond the scope of this short article, the matter is one that requires additional empirical research to inform us about such interconnections. Accordingly, attempts to chart trends of success criteria in the temporality realm during certain time frames remain unfinished at this point.

Success Criterion 3: Locus of Success – Success For Whom?

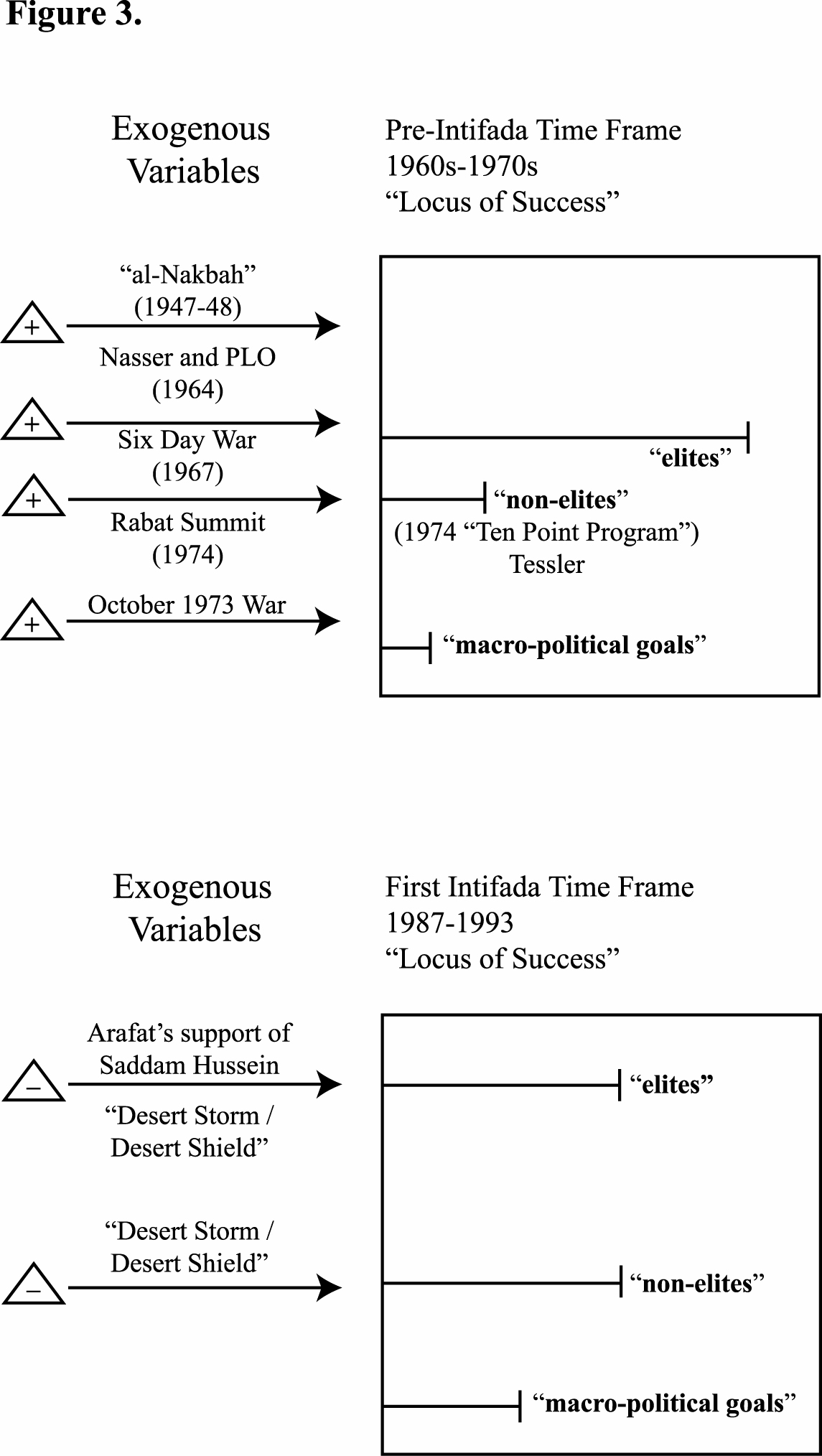

20 Both Lesch and Sayigh seem to suggest that other factors or facts on the ground made for either partial or complete success within the dimension of locus of success. But any measure of this success during the pre-Intifada time frame seems limited largely to the Arab political elite, including terrorist leaders. For example, the stalling of the "land for peace" concept that some believed lay at the heart of the "Allon Plan" after the Six Day War and the lack of consensus among Israelis about the final status of the Occupied Territories (for example, the conflict between the Jewish revivalists of Gush Emunim and other Israelis), ultimately led to the political and financial enfranchisement of Palestinian-Arab terrorist organizations, at least in part at the expense of broader based Palestinian-Arab „insider‟ interests.25

21 For the purposes of this article, those effects are viewed, in a preliminary manner, as residual effects of the Six-Day War. Accordingly, there is an enormous distance between conceptual patterns depicted in the chart for locus of success (see Figure 3). It plainly depicts the success accrued by the Palestinian political elites and the absence of more substantive benefits to most Palestinian-Arabs. Certainly among the political elite of nation states who supported terrorist leaders in political terms and among terrorist leaders and activists, success could be claimed based in part on personal aggrandizement and/or betterment of the group. For example, this was the case when President Gamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt helped to establish the PLO during the First Arab Summit in 1964. On the face of it, the PLO was created to deflect Syrian criticism away from Nasser who, as the self-anointed „leader of the Arab world,‟ was unwilling to confront the Israelis militarily over the „Water Carrier project,‟ in which water from Northern Israel was diverted to the Negev desert.26 In turn, Tessler suggests that certain political initiatives that followed in the wake of the 1973 October War, such as the „Ten Point Program‟ announced at the 12th PNC, worked to inject a high dose of commitment into the central notion of a "two-state solution," a notion that became increasingly popular after that war. In the model depicted, those gains are construed as political gains for Palestinian-Arabs in the broader sense. By contrast, the Rabat Summit of 1974, which underscored the emergent reality of the PLO as the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people," is recorded as a political gain that accrued primarily to the PLO at the elite level.27

Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

22 With respect to the macro-political goals, the Six Day War helped to generate and sustain, at least until 1973, an aura of Israeli military invulnerability that more than offset any prospect for meaningful reflection for many Israelis about how prudent it would be to retain the Occupied Territories indefinitely. To be sure, former Israeli Prime Minister David Ben Gurion was one of those Israelis who expressed great concern about Israeli control over the territories, even though his reasons were not close to the mark.28 Accordingly, macro-political goal accomplishment is viewed as practically nil during this time frame.

23 The importance of still more exogenous effects with respect to various success criteria will be described below. To sum up my locus of success findings, very little, if any, success as it is defined here resonated with average Palestinians – the „insiders‟ – who languished in towns, villages, and refugee camps, and who had to cope with seemingly unending Israeli control of the Occupied Territories.29 Hence, the locus of success criterion was not met here except for very few of Palestinian-Arab and Arab political-social elite, who also include traditional „notables‟ supported by the Israelis and the Jordanians.30 At a substantive level, there was precious little, if any, success in terms of accomplishing macro-political goals. Clearly, at this stage the nexus between activity at the elite level among Palestinian „outsiders‟ that largely revolved around terrorism and that of „insiders‟ that was based on the acute need for infrastructure development to confront the Israelis, still remained a work in progress.

THE FIRST INTIFADA,1987-93 31

Success Criterion 1: Dimensionality

24 An analysis of the First Intifada illuminates underlying trends that present a somewhat different picture than the earlier period. In the case of dimensionality, overall recognition of the legitimacy of the fierce Palestinian struggle was enhanced and there was rapid expansion of organizational structures but the military success criterion remained underdeveloped (See Figure 2). For the first criterion Teitelbaum and Kostiner tell us that legitimacy recognition increased several-fold. Many young people, who composed what Sayigh calls „strike forces,‟ were portrayed in „heroic‟ roles for their efforts to confront the Israeli military, and in the process demonstrated an enormous capacity, largely unseen among earlier generations, to endure Israeli hardships in effective and sustained ways. For those authors, "another achievement was the uprising‟s remarkable success with the Western media. The rioters were able to shake the traditional image of „terrorists‟ usually attributed to Palestinian PLO activists and began to be perceived as legitimate freedom fighters."32

25 Perhaps the single, most significant achievement of the First Intifada in terms of tangible results at the organizational sub-level was the development of internal infrastructure in the Territories with an enormous capacity to keep what Sayigh calls "a general movement" thriving in an effective and sustained way.33 The PLO, with its own geopolitical considerations in mind, needed to become inextricably bound up with the continuously evolving environment of West Bank politics. Compounding the matter even more, Teitelbaum and Kostiner, Sayigh, and Lesch all suggest that in the realms of security and civil administration (for example, including tax collection, constraints on exports from the territories, and forcibly keeping shops open for business) Israeli policy facilitated a set of relationships among residents of the territories, and between those residents and the PLO.34

26 Teitelbaum and Kostiner go on to describe various fledgling associations in place in the Territories that were associated with time-honored and long-standing Middle East terrorist groups.35 For example, the association Jabhat al-Amal (Action Front) emerged as an affiliate of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Al-Shabiba (Youth) was crafted as an affiliate to al-Fatah, al-Wada (Unity) evolved as an affiliate of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, while the Palestine Communist Party also had its own parallel institution in place on the ground. What seems significant here is that, as Teitlebaum and Kostiner report, it was out of this reservoir that particular persons, whose identities were shrouded in mystery, assumed positions at the epicenter of the Intifada, namely the United National Leadership of the Uprising (UNLU).36 Parenthetically, The Muslim Brotherhood, (Jamayyat al-Ikhwan al Muslimin), always a frequent visitor to West Bank politics, had a student contingent that participated in the political fray.37 In addition, Tessler tells us that while Islamic Jihad joined the UNLU in 1987, it encountered problems as a result of the enormous ideological distance between it and more secular Palestinians. In turn, Hamas, that was crafted in 1987-88, remained outside of the UNLU framework from the start.38

27 Equally important, at a more pedestrian level, there were many associations with what Sayigh calls a „looser‟ set of interconnections that served as support infrastructure, both for those who engaged in actual physical confrontation with the Israeli military and those, such as shopkeepers and professionals, who confronted Israeli occupation in a more nuanced manner.39 For Sayigh, one underlying theme that resonated between those organizations was the notion of takaful (mutual assistance), whereby subsistence donations to community, such as food staples, were facilitated by the UNLU.40 The cross-fertilization effects of the UNLU, insofar as its support of associations tailor-made to address the needs of Palestinians, and the capacity of a solid constituency group to contribute to a condition where Palestinian "strike force" activists, who at some level were under the aegis of the UNLU, could pick and choose the place and time of conflict, were mutually reinforcing at the organizational sub-level of dimensionality.41

28 In this honeycomb-like web of relationships, Sayigh identifies a host of associations that, in essence, practiced specialization. For example, he describes educational committees that crafted ad hoc curricula to educate young persons in the wake of Israeli school closures; the Union of Palestinian Medical Committees, first formed in 1979, that assisted in providing essential medical services; and cooperatives that were put together to supply basic commodities, thereby in effect helping to reduce Palestinian economic dependence on the Israeli economy.42 Many cooperatives tried to grow food, worked to clothe, and otherwise supply those persons involved in direct physical conflict with the Israeli military. What is significant for Sayigh is the obvious "mass mobilization" of socio-economic divisions in society, or what Tessler calls "a kind of radical populism" that was a hallmark of the First Intifada.43

29 Returning to the model, what exogenous factors could have led to an emphasis on organizational capacity within the Occupied Territories? One factor that several writers allude to was the fledgling efforts of the US and PLO to take diplomatic initiatives. Those were consistent with the overall approach articulated in the "Reagan Plan" and the follow-up "Fez Plan" articulated as a response during this time period.44 Indeed, it is probably fair to say that US-PLO diplomatic forays were even consistent with the Nixon-Kissinger settlement negotiation efforts that followed the 1973 war. In a similar vein, Lesch writes that the Amman Summit, during which King Hussein and other Arab leaders "snubbed" Arafat and the PLO by focusing almost exclusively on the Iran-Iraq War, had a pivotal effect on Palestinian mobilization.45 So, it is possible to identify the Amman Summit as another exogenous factor that affected the perception of the need to emphasize organizational strength at this juncture. It is also possible that the 1982 war in Lebanon, which led to the ouster of the PLO from Beirut and its relocation to Tunisia that helped to shift the focus of events to the Occupied Territories, also served as an important exogenous variable.46

30 Clearly, the rudiments of organizational capacity that were honed during the pre-Intifada time frame expanded during the uprising and that would constitute a success for the second element of dimensionality. Plainly, that success was sequential; organizational accomplishment followed in the wake of an enormous increase in recognition in the 1970s.47 What seems significant here is that this period signals a structural shift of sorts, insofar as the image of Palestinians as legitimate „underdogs‟ contributed to that emergent reality in the eyes of many in the world community.

31 Also, one question to address is whether or not, and to what degree, the Intifada had discernable effects on outside developments. Although a comprehensive answer to that is beyond the scope of this article, it is reasonable to assume that events in the Occupied Territories spurred on efforts to make contacts between non-PLO-affiliated Palestinians and Israelis in Madrid in 1991 the new reality.48 Indeed, the First Intifada probably had a profound and lasting effect on Israeli foreign policy. In particular, there was a hardening of political positions among many nation-states in the Middle East and other nation-states elsewhere with large Muslim populations, such as Indonesia.

32 During the First Intifada there was more political-organizational than military success. One reason for this is that Palestinians confined themselves to what Teitelbaum and Kostiner refer to as "limited violence." Stone throwing, tire burning, the use of Molotov cocktails, property destruction, along with the more episodic and inconsistent use of violence against people that could be construed to be terrorism, were hallmarks of the First Intifada.49 Some writers point to a conscious effort on the part of the UNLU to curtail the use of terrorism, although clearly terrorist attacks did happen.50

33 All of this raises the fundamental question – why? It seems plausible to suggest that the prospect of success in the diplomatic realm underpinned calls to limit the use of violence, in order to achieve political gains. Equally important, the enormous capacity of Israel for military response may have served as a deterrent. At the same time, it is critical to recognize that there was also a strain of the Palestinian elite who believed in a course of action that, in effect, resembled a form of „civil disobedience‟ consistent with the concept as articulated by Henry David Thoreau in his Essay on Civil Disobedience.51

34 Indeed, certain Palestinian luminaries, such as Mubarak Awad, Sari Nusayba, and Gabi Baramki, may well have served as a moderating influence.52

Success Criterion 2: Temporality

35 As the First Intifada put a premium on „limited violence‟ and achieved political-social and organizational successes, those gains seemed to be, at first glance, associated with some middle-term and longer range successes. In this regard, one underlying change that Tessler points to was that the Intifada helped to alter the time-honored, long-standing Israeli perception about what lay at the heart of the Arab-Israeli conflict. He argues that the Intifada led to an ineluctable structural shift in Israeli thinking, in which Palestinians in the Occupied Territories, by contrast with the PLO, were now conceived – in a more carefully reasoned way – to be at the heart of the conflict.53 As such, the most profound and lasting effect of the First Intifada was that it laid the foundation for Palestinian-Israeli interactions at the Madrid conference of 1991.

36 What seems significant here is that these accomplishments presupposed and derived from previous non-violent achievement (i.e., enhanced organization) in the dimensionality realm, but that those non-violent gains themselves can trace a link to the 1970s terrorist attacks that contributed in toto to enhanced recognition from the start. Conversely, seen from the vantage of our contemporary world, one can extend the parameters of dynamics and events to establish a connection between the organizational successes in the late 1980s and the negotiations that led to the 1993 peace process.

Success Criterion 3: Locus of Success

37 Plainly, the ratios for the elements of locus of success shifted substantially between the pre-Intifada period and the First Intifada. This occurred precisely because the basis for success, which revolved around political mobilization and participation resources, became more evenly distributed between PLO outsiders and Palestinian insiders (see Figure 3). The benefits that derived from those resources were not necessarily monetary in nature but also involved notions of empowerment and similar sentiments. This type of resource re-distribution can be seen as structural change in ways that reflect a shift in political momentum from PLO outsiders to Palestinian insiders, some of whom worked in conjunction with the PLO. This represented, as Teitlebaum and Kostiner and others suggest, a shift between „old‟ and „young‟ Palestinian generations or a shift between partial and full-blown political mobilization of their society. Indeed, a full portrait of those dynamics of Palestinian societal change would have to take into account many – if not all – of those dimensions.

38 Thus, it is probably safe to say that, by means of that sacrifice and struggle, some profound and lasting net political gains had been made in the realms of both elite and non-elite levels of Palestinian society. As former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright might put it, those dynamics affected political demands and aspirations associated with „human dignity‟ concerns. As a result, the First Intifada had, in some sense, a profound and lasting cathartic effect for the masses, even though more tangible long-haul macro-political gains proved to be elusive at this stage.54 Seen from a slightly different angle, Remma Hammami and Salim Tamari state that perhaps the single most predominant macro-political goal that the First Intifada achieved was its capacity to illustrate that Palestinian demands and aspirations demanded a political and not a military solution, in part because of the underlying inability of Israeli military approaches and actions to quell the Intifada.55

39 However, part of the tragedy associated with the First Intifada arose from the effects of an exogenous variable: the 1990-91 Gulf War. It diverted attention away from the events in the Occupied Territories to the crisis and war in the Persian Gulf. Compounding the problem even more, PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat made the unsound decision to support Saddam Hussein against United States and Israel. For those and other reasons, the First Intifada "lost direction," as Tessler puts it, by the early 1990s.56

THE AL-AQSA INTIFADA

Success Criterion 1: Dimensionality

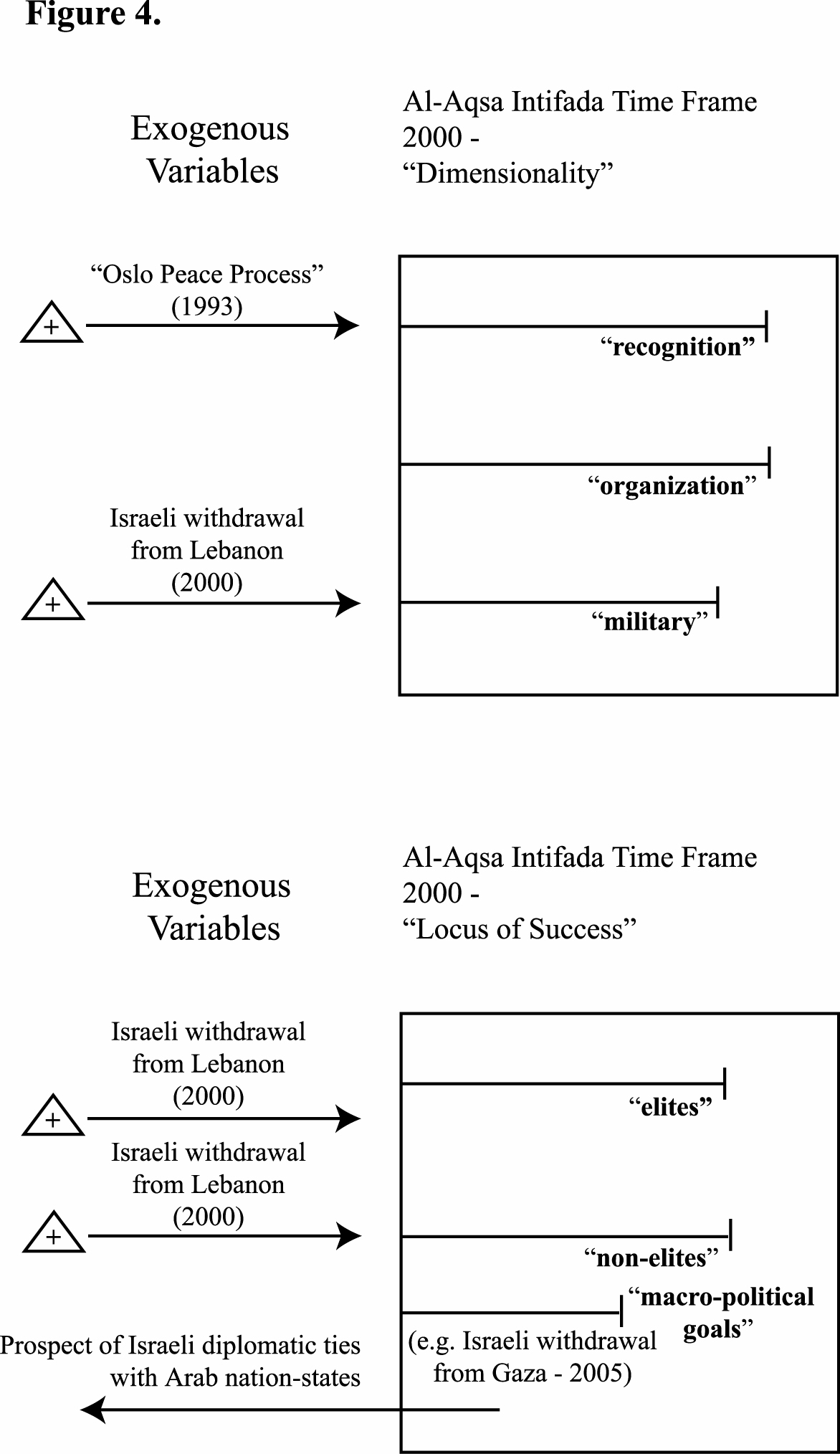

40 The al-Aqsa Intifada presents a different picture with respect to trends in the dimensionality variable. In the case of the recognition factor, the al-Aqsa Intifada did not so much increase recognition of the scope of the Palestinian‟s struggle as it illuminated the depth of their commitment. It showed that they were willing to kill and be killed for the sake of the movement. In essence, the dynamics of this second Intifada illustrate that recognition can now be perceived as multidimensional. In this case, empirical evidence illustrates a willingness of segments of the populace to kill and die, where before such dynamics were seemingly limited to trained terrorist activists (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

41 The 1993 Oslo peace process can be seen as a precursor to the al-Aqsa Intifada. It further increased the recognition factor in the traditional sense, evolving to a point of full-blown articulation. In essence, certain political/diplomatic aspects of it can also be viewed, in some sense, as an exogenous variable somehow removed from the bleak reality of events on the ground in the Territories. Consequently, external events and dynamics, such as the stalling of the Camp David negotiations in 2000, or the primary empowerment of the PLO elite as opposed to empowerment of Palestinian-Arab insiders, all had substantive disruptive effects. This set the stage for the amplification of anger and similar sentiments that began to compound as political events at the elite level began to outpace parallel implementation developments on the ground in the Territories, with direct and tangible links to the overall self-determination process.

42 For instance, numerous scholars identify several examples of such negotiation obstacles found at the elite level, including ambiguous Israeli interpretations about the implementation of the Oslo Accord and Palestinian dissatisfaction with the handling of core issues. The latter included the status of Jerusalem, and Haram al-Sharif (the Temple Mount) in particular, the "right of return," and subsequently, the need for what Kirsten Schulze calls "an exit strategy" for PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat.57 Compounding the matter even more was the more clearly endogenous variable of Israeli policy. That included construction of bypass roads and Prime Minister Ehud Barak‟s acute sensitivity to support from the Likud party, which in turn translated into tacit support for more land appropriation for settlements and the almost institutionalized nature of Jewish settler terrorism. All of that contributed to what Teitelbaum and Kostiner might refer to as growing "frustration aggression" among Palestinian-Arabs.58 Indeed, Hammami and Tamari make the tantalizing point that it was not only land appropriation per se that caused volcanic-like rage among Palestinian-Arabs but appropriations that increasingly encroached on "Palestinian urban centers."59 To be sure, the looming catastrophe of impediments to the Oslo peace process posed a set of challenges and opportunities as the process "muddled through," as Lindblom might put it, in incremental stages.60

43 In the case of the second element of dimensionality, namely organization, Schulze asserts that there were "both organized and unorganized elements" that played major roles in what she calls the "spontaneous" outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada.61 In ways that echo patterns of involvement seen during the First Intifada, she states that the PLO rode – in effective and sustained ways – a wave of popular discontent associated with the stagnant environment of the Oslo Peace Process.62 In the narrower sense, both Schulze, and Hammami and Tamari point to several levels of infrastructure that were pivotal in terms of al-Aqsa Intfada organization. In the broader sense, the Tanzim have been described by Hammami and Tamari as "a murky designation that includes Fatah‟s street cadre (often with privately licensed weaponry) and . . . elements of the Palestinian Authority Preventative Security Force."63 The collective authors from the Institute for Counter-Terrorism offer a different perspective. They argue that one way of thinking about Tanzim dynamics is to understand that the group was based on and derived from Palestinian insider support, in contrast to Palestinian outsider support, which was focused almost solely on the Palestinian National Authority (PNA).64 My work shows that an "al- Fatah aggregate," composed of acts attributed to al-Fatah, al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, and Tanzim groups, committed 4.8 percent of identifiable al-Aqsa Intifada terrorist attacks.65

44 At the more hierarchal level, the "Higher Committee for the Follow-up to the Intifada (NIHC)" was put in place and operational by November 2000. For Hammami and Tamari this was a broader framework that included Islamic revivalist organizations and secular Palestinian-Arab organizations such as al-Fatah.66 They suggest that the NIHC was not designed to be an overwhelming hierarchal force or gatekeeper for the uprising but one that provided guideposts to steer gently the course of a popular insurrection. What also seems significant here, as they also suggest, is that extant organizational infrastructure left over from the First Intifada remained in place, thereby in effect helping to facilitate operations.67

45 An exogenous variable that may have contributed to an increase in the military success component of dimensionality was the withdrawal of Israeli forces from Southern Lebanon on 24 May 2000.68 Shulze feels that the Israeli withdrawal from the so-called „buffer zone‟ after prolonged conflict with Lebanese forces inspired Palestinians in the Territories to believe that some tactical military success was achievable.69 This is not the same thing as saying that Israel‟s withdrawal from Lebanon derived from any political instability and social unrest in the immediate pre-Al-Aqsa Intifada period for plainly it did not. It is probably no exaggeration to say that the withdrawal was a function of the effectiveness of Islamic revivalist extremists, enhanced by outside funding and other means of support from Syrian and Iranian leaders. What is significant here is the "spillover effect" – the inspirational value of Israel‟s withdrawal for Palestinians in the Occupied Territories.

46 At the same time, military success may have been enhanced in part because of what Hammami and Tamari describe as a continuously evolving focus of Palestinian terrorist leaders and activists on terrorist attacks against Israeli settlements.70 Somewhat different patterns emerge in my own work but that may derive from the fact that my analysis examined only the first phase of the al-Aqsa Intifada, prior to the Israeli counter-terror offensive Operation Defensive Shield, which started on 29 March 2002.71 I found that during the first 17 months of the second Intifada, Israeli settlements were attacked 21.2 percent of the time (239/1,126 attacks), and „anonymous‟ acts comprised 87.9 percent of those. By contrast, cities and towns were attacked 372 times, comprising 33 percent of the attacks, and anonymous acts comprised 46.5 percent of those incidents. In turn, some 44.2 percent of terrorist assaults (498/1,126) were aimed at targets „en-route,‟ such as persons in transit. 69.5 percent of those attacks were unclaimed. Interestingly, kibbutzim and moshavim (Israeli agricultural settlements) experienced only 1.5 percent (17) of the terrorist attacks at that time, with an anonymity rate of 64.7 percent. Beyond the differences in target type, these findings suggest a profound and lasting change in strategy and a movement away from „limited force‟ approach that characterized the First Intifada.72

Success Criterion 2: Temporality

47 What seems significant about the al-Asqa Intifada in this context is that terrorist attacks beyond the Green Line into Israel proper, and especially the increasing use of „suicide bombers,‟ generated and sustained an abject fear among Israelis. That increased pressure on the political elite for political change, either toward more full-blown military action – as espoused by the Israeli right wing – or toward structural political change and accommodation – as demanded by the Israeli political left. It is here that the combined effect of multiple, frequent terrorist assaults, and equally important, the qualitative-psychological effects associated with suicide bombings, taking place in a seemingly haphazard manner, achieved rapid military success. The capacity of terrorists to enter Israel also continued to change the dynamics of the struggle. In effect, they helped to eliminate the notion, once popular among elites and non-elites in Israel alike, that the Occupied Territories were necessary as a „buffer zone‟ for Israeli national security.

Success Criterion 3: Locus of Success

48 In the broadest sense, perhaps the single, most predominant success within this criterion was the removal of Israeli settlers from the Gaza Strip in August and September 2005. Clearly that would constitute degrees of success at both "elite" and "non-elite" levels of Palestinian-Arab society. Interestingly, as Fatah points out, there have been indirect „ripple effects‟ for Israel from the withdrawal that include the prospect of improved relations with other Arab or Muslim nation-states, such as Kuwait, Tunisia, Bahrain, and Qatar and Pakistan.73 From the vantage point of long-term macro-political goals, such fledgling links may be seen as a potential success. Albeit in embryonic stages at this point, such relationships may – by means of economic interdependence – induce many Israelis to modify their hard-line approach about the emergent reality of the nation-state of Palestine.74

49 That said, thus far the al-Aqsa Intifada does not seem to have achieved any other macro-political goals, such as serious reconsideration on the part of the Israeli elite of the status of the West Bank, including Jerusalem. Nor has it solved the all too familiar set of Palestinian-Arab internal problems that include corruption and the development of aspects of „civil society.‟ Here the matter really boils down to the fundamental question of what to do with Hamas. That group did well enough in Palestinian elections and wields enough local power to become the de facto „government‟ of Gaza but is simply not committed to the notion of a „two state solution.‟75 What is significant here is the transition of the national liberation struggle from a condition of successes and failures to the point where the emergent reality is a nation-state. That state-in-the-making comes complete with a political system of „representative democracy,‟ including independent institutions that thrive in effective and sustained ways. Work by a number of scholars that illustrates political transition in terms of a set of sequential stages might serve as a template for the political reforms needed for the long-term success of a fledgling Palestinan nation-state recognized and supported by the community of nations.76

FINAL REFLECTIONS

50 In the broader sense, this typology of success criteria for the Palestinian-Arab nationalist movement has served to isolate and identify trends of Palestinian accomplishments for three generally recognizable time periods. In the pre-Intifada period of the 1960s and 1970s, they made progress in the recognition realm and to a much smaller degree in the organization realm of dimensionality.

51 In the temporality realm, it is fair to say that, in the short-run, terrorist attacks and even terrorist campaigns generated and sustained fear but also produced long-haul counterterrorism infrastructure modification, especially in the domains of international law and national security apparatus. In turn, this pre-Intifada phase of Palestinian-Arab national liberation struggle made precious few gains in the realm of locus of success. Indeed, qualitative descriptions in scripted accounts made it relatively easy to determine that meaningful gains were found almost exclusively among elites, with few if any substantive benefits accruing to non-elites in the broader sense. In a similar vein, Palestinian terrorist attacks yielded almost no macro-political goals.

52 During the First Intifada substantial progress was made in the dimensionality realm, primarily in organization, with secondary gains in terms of recognition. Indeed, that progress was also hastened by exogenous as well as endogenous factors. The endogenous factors comprised a network of organizational links between Palestinian-Arab associations that produced a set of robust safety nets for Palestinian activists and their supporters. The exogenous variables were diplomatic initiatives that included efforts by the United States. These underscored the perception among Palestinians on the ground that the time was right to develop further the infrastructure needed to sustain political as well as paramilitary resistance against the Israeli occupation.

53 Significantly, those organizational successes derived from previous successes in the realm of recognition that characterized the pre-Intifada era. Conversely, there were severe obstacles to the military success component of dimensionality that reflected not only enormous Israeli military superiority but also limits imposed by Palestinian-Arab leaders on the use of violence within what has been characterized – incorrectly in my judgment – as the context of „civil disobedience.‟ It appears that the recognition acquired in the pre-Intifada period, coupled with marginal gains in organizational components, contributed to successes in the temporality area. To be more specific, recognition success seemed to be linked to a structural shift in perception with middle- and long-term ramifications and to real political gains for Palestinian-Arabs, who were increasingly perceived to be at the heart of the conflict rather than on the periphery.

54 Furthermore, this finding underscores the importance of how previous successes found at different levels of analysis may well have positive inter-level influences, where successes in one realm contribute, at least in part, to unfolding successes at other levels. In a similar vein, there appeared to be significant gains in the locus of success domain that essentially reflected a broader and more evenly distributed set of benefits across elite and non-elite social strata, and at a functional level, primarily between Palestinian-Arab insiders and outsiders. Still, macro-political gains relating to substantive movement towards the crafting of a Palestinian state recognized by the Israeli government proved to be elusive.

55 In the case of the al-Aqsa Intifada, the recognition factor appeared to increase primarily in depth rather than in scope as it became increasingly clear that Palestinian-Arabs were prepared to kill or be killed in pursuit of Palestinian nationalist objectives. Both exogenous events and endogenous factors served to create volcanic-like political pressures prior to the outbreak of this second Intifada that was, in effect, triggered by Ariel Sharon‟s visit to Jerusalem‟s Temple Mount. In organizational domain certain new layers of Palestinian organizational and overall support infrastructure were crafted. But existing infrastructure that could be traced back to the First Intifada helped to facilitate the second one. There was also an enormous increase in military success rates as the constraints on violence imposed by Palestinian-Arab leaders during the First Intifada were removed.

56 Middle- and perhaps even long-term temporality goals were met in the al-Aqsa Intifada. Specifically, the capacity of Palestinian-Arabs, including suicide bombers, to engage in full-blown insurrection with operations conducted inside of Israel, elicited abject fear that spilled over into the middle-term and beyond. The locus of success for the benefits – psychological and otherwise – of the uprising included both Palestinian-Arab elites and non-elites, as Palestinians proved they were courageous and able to conduct full-scale insurrection that was sustainable. In the process, macro-political goals were achieved, as the mainstream in both camps found a new sense of urgency for political negotiations to address underlying issues of the Israeli-Palestinian-Arab conflict.

57 In closing, this first pass at a qualitative analysis of Palestinian success trends illuminates a series of patterns of success in different realms and at different time sequences that seemed to derive from earlier successes or gaps in progress. It also seems clear that both endogenous or domestic factors and exogenous or external factors exerted influence on rates of progress, even though determining how, in what mix, or to what degree remains beyond the scope of this article. In the meantime, I hope that this rudimentary conceptualization might provide some insight into ethnic conflict phase development and success benchmarks with potential for applications to other communal conflicts.

Richard J. Chasdi teaches at the Center for Peace and Conflict Studies at Wayne State University.

Endnotes