Retaining Core Staff:

The impact of human resource practices on organisational commitment

Janet Chew

Murdoch University, Western Australia

Antonia Girardi

Leland Entrekin

Murdoch University, Western Australia

Abstract

As organisations battle to get the most from their existing people in an environment characterised by skill shortages, the role of human resource practices in fostering employee engagement and commitment is paramount. This paper reports the findings of an Australian study, which examined the current relationship between human resource management practices and the retention of core (critical) employees working in nine organisations. This research specifically, reports on the conditional nature of the relationship between organisational and human resource practices, and commitment. The findings of the study have important implications for human resource academics and practioners.Introduction

1 Strategic human resource management (SHRM) is at a critical point, poised between becoming a strategic business partner or receding into oblivion, as there is much debate about its relevance and contribution to the bottom-line and organisational effectiveness (Lawler & Mohrman, 2003: Jamrog & Overholt, 2004: Ulrich, 1998). As organisations battle to get the most from their existing people in an environment characterised by skill shortages, the role of human resource management in fostering employee attachment and commitment is paramount. If strategic human resource management is to tip thebalance towards being perceived as a business partner, it appears that a consolidated approach toward identifying those human resource practices which foster and support attachment to the organisation is key.

Organisational Attachment

2 Traditionally, within the employment relationship, employees exchanged their loyalty and hard work for the promise of job security. In the contemporary environment, changes in organisational structure towards more flexible work practices and the decline in job security, have altered the psychological contract between employer and employee (Allan, 2002; Wiens-Tuers, 2001). The new form of psychological contract is visible in placement practices, which see organisations focus on non-core and part-time workers to gain flexibility at lower cost (Cappelli, 1999; Kalleberg, 2000). Because of these organisation-wide changes, the essence of attachment between employer and employee has changed.

3 The old contract of employee loyalty in exchange for job security and fair work has dissolved (Overman, 1998). Current employers emphasise "employ-ability” rather than long-term loyalty in a specific job (Cappelli, 1999; Ko, 2003). The trend these days, seems to be geared towards having a ‘ career port-folio' 1 (Handy, 1995; Hays & Kearney, 2001). Replacing the old employment deal, the new psychological contract suggests that the employer and the employee meet each other's needs for the moment but are not making long-term commitments.

4 It is suggested that commitment to one's professional growth has replaced organisational commitment (Bozeman & Perrewe, 2001; Powers, 2000). Instead of job security, employees now seek job resiliency; opportunities for skill development and flexibility in order to quickly respond to shifting employer requirements (Barner 1994). Employees seem to take greater responsibility for their own professional growth in order to increase their career marketability (Finegan, 2000).

5 Employee commitment, it seems, has become a casualty of the transition from an industrial age to an information society.

Commitment

6 Commitment is a belief which reflects "the strength of a person's attachment to an organization” (Grusky, 1966, p. 489). Researchers have suggested that reciprocity is a mechanism underlying commitment (Angle & Perry, 1983; Scholl, 1981) and that employees will offer their commitment to the organisation in reciprocation for the organisation having fulfilled its psychological contract (Angle & Perry 1983; Robinson, Kraatz & Rousseau, 1994). By fulfilling obligations relating to, for example, pay, job security, and career development,employers are creating a need for employees to reciprocate, and this can take the form of attitudinal reciprocity through enhanced commitment and consequently influence employees to stay with the organisation (Becker & Huselid, 1998; Capelli, 2000; Furnham, 2002; Oakland & Oakland, 2001; Wagar, 2003)

7 Previous studies of the concept of commitment (Mowday, Porter & Steers, 1982; Meyer & Allen 1991) have substantiated that employee commitment to the organisation has a positive influence on job performance and a negative influence on intention to leave or employee turnover. In addition, empirical evidence also strongly supports the position that intent to stay or leave is strongly and consistently related to voluntary turnover (Dalessio, Silverman & Schuck, 1986; Fishbein & Ajzen 1975; Griffeth, Hom & Gaertner, 2000; Lambert, Hogan & Barton, 2001; Mathieu & Zajac, 1990).

8 Of the three commonly cited components of commitment, (i.e. continuance, normative and affective) affective commitment is the most studied dimension (Aven, Parker & McEvoy, 1993; Dunham, Grube & Castaneda, 1994; Wahn, 1998). Affective commitment is considered to be an affect-focused attitude towards the organisation, which represents an emotional bond between an employee and his or her organisation (Allen, 1996). Individuals possessing high levels of affective commitment identify with, are involved in, and enjoy membership in the organisation and are therefore more likely to remain with the organisation.

9 Ulrich (1998) has suggested that engaging employees' emotional energy gains commitment toward the organisation. The most fundamental of those processes thought to influence affective commitment is an employee's personal fulfilment based on met needs and positive work experiences (Meyer & Allen, 1997). Although employees may develop affective commitment through relatively unconscious associations with positive work experiences (classical conditioning), research suggests that affective commitment can be consciously influenced by human resource practices such as collaboration and team work, high autonomy job design, training and development, rewards, and participation in decision making (Agarwala, 2003, Meyer & Allen, 1997, Ulrich, 1998). Despite substantial literature on HRM "best practices and high performance practices,” there is little consensus among researchers and practioners as to precisely which HRM practices effectively combat attrition of the core employee group (Becker & Gerhart, 1996; Gumbus & Johnson, 2003; Marchington & Grugulis, 2000; Parker & Wright, 2001; Pfeffer, 1998; Stein, 2000 ; Wagar, 2003).

The Return of Organisational Commitment through HR Bundling

10 Reviews of the diffusion and penetration of high performance work practices in organisations (Pils & Macduffie, 1996; Wood & de Menezes, 1998) indicate that a fragmented and ad hoc approach prevails. For example, the Wood and de Menezes (1998) study revealed different patterns in the use of high performance work practices in firms. Most firms invested only in skill formation and direct communication, which can affect job related commitment to a limited extent. There were great variations when it came to performance appraisal, reward systems and information disclosure that have immense potential to influence commitment to the organization.

11 Several studies of progressive HRM practices in training, compensation and reward have revealed that these can lead to reduced turnover, absenteeism, better quality work, and better financial performance (Arthur, 1994; Davies, 2001; Delaney & Huselid, 1996; Ichniowski, Shaw & Prennushi, 1997; Macduffie, 1995; Snell & Dean, 1992; Tower Perrin, 2003). Overall, studies at the organisation level suggest that such motivation-oriented human resource activities are more likely to be associated with perceived organisational support and commitment than skilled oriented activities (Delery, 1998; Huselid, 1995;Whitener, 2001).

12 Therefore, a challenge for human resource practitioners is clearly to design holistic systems that influence commitment and provide positive work experiences simultaneously. This is similar to the idea that it is necessary to implement "bundles” of human resource management practices (Macduffie, 1995; Youndt, Snell, Dean & Lepak, 1996) to positively influence organisational performance (Huselid, 1995).

13 A number of employee retention-commitment models particularly advocate the advantages of high involvement or high commitment human resource practices in enhancing employees. (Beck, 2001;Clarke, 2001; Gumbus & Johnson, 2003; Mercer, 2003; Parker & Wright, 2001). Previous work (Arthur, 1994; Becker & Gerhart, 1996; Huselid, 1995; Shaw, Delery, Jenkins & Gupta, 1998) indicated that high-involvement work practices will enhance employee retention. The identified HR practices included selective staffing, competitive and equitable compensation, recognition, comprehensive training and development activities (career development, challenging opportunities) (Ichniowski, Shaw & Prennushi, 1997; Macduffie, 1995; Snell & Dean, 1992; Youndt, Snell, Dean & Lepak, 1996).

14 Recent studies (Accenture, 2001; Baron & Kreps, 1999; Clarke, 2001; Mercer, 2003; Tower Perrin, 2003; Watson Wyatt, 1999) suggest that there is a set of best practices for managing employee retention.

15 Chew and Entrekin (2004) highlight eight key factors influencing retention. These factors were identified via an in-depth Delphi study involving a panel of thirteen experts comprising of academics, HRM practitioners and industrial psychologists followed by a series of in-depth interviews with HR managers of twelve Australian organisations. These HRM retention factors were categorised into two bundles: 1) HR factors (person organisation fit, remuneration, training and career development, challenging opportunities) and 2) organisational factors (leadership behaviour, teamwork relationship, company culture and policies and satisfactory work environment). Similarly to Fitz-enz (1990), this study concludes that retention management of employees is influenced by several key factors, which should be managed congruently and thereby implies that both organisational factors and human resource practices may influence retention of staff and thereby commitment.

16 However, which factors have more explanatory power in influencing organisational commitment? To date this question has not been explored.

17 This study therefore, aims to investigate the impact of these practices in influencing organisational commitment via a hierarchical regression analysis.

The Study

18 The sample population used in this study consisted of core employees of nine large Australian organisations. Core employees were defined as permanent or critical workers with the following key characteristics: 1) possess knowledge, skills and attributes (KSA) aligned with business operation and direction, 2) is central to productivity and wellbeing of the organisation, 3) provide a competitive edge to the organisation, 4) support the organisational culture and vision and 5) possess KSA that are relatively rare or irreplaceable to ensure the success of the organisation (Allan & Sienko, 1997; Chew, 2003; Gramm & Schnell, 2001). The participating organisations were from various industry sectors which included health-care, higher education, public sector and private sector (manufacturing, engineering, high technology etc). A total of 456 respondents completed surveys which tapped the areas of interest were received, resulting in a 57 per cent response rate. The average age was 40-49 years and participants had an average of 8-12 years of organizational tenure. Fifty-five per cent of the sample was male and 94% had tertiary qualifications.

Measures

19 The choice of variables reflects the view that both organisational factors (organisational bundle) and human resource practices (HR bundle) influences commitment perceptions of core employees. All items were scored along a seven-point scale, ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree.

20 The organisational factors bundle was measured by four variables: leadership behaviour, teamwork relationship, company culture and the work environment.

21 Leadership behaviour was measured via a four item scale. The scale consisted of items adapted from two validated scales: (1) the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire devised by Bass and Avolio (1990), which measured transformational leadership and (2) the eight-item scale by Hartog, Van Muiijen and Koopmen (1997) which measured inspirational leadership. The adapted scale used in this study measured leadership behaviour in terms of leadership effectiveness, extra effort and leadership satisfaction.

22 Teamwork relationship was measured via a four-item scale developed by Bass and Avolio (1990). Items tapping: team leadership and relationship of employees and peer leadership, were included in this study.

23 A five-item scale modified from The Organisation Profile Questionnaire (O'Reilly, Chatmen & Caldwell, 1991; Morita, Lee & Mowdey, 1989; Sheriden, 1992) and developed by Broadfoot and Ashkanasy (1994) was used to measure organisational culture. The scale measures the degree the organisational structure limits the action of employees, the focus on the influence of policies and procedures, and tests organisational goal clarity and planning.

24 Work environment was measured via a seven-item scale designed to measure humanistic and socialisation, physical work conditions and organisational climate (Broadfoot & Ashkanasy, 1994; Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins & Klesh, 1979; Smith, 1976).

25 The human resource bundle was measured by four practices relating to: selection; remuneration and recognition, opportunities for training and career development, and job design.

26 Selection was measured via a four item scale developed by Netemeyer, Boles,Mckee and McMurrian (1997). This construct reflects the person-job element of selection (Cable & Judge, 1997).

27 Remuneration and recognition was measured with a five- item scale which focused on intrinsic and extrinsic rewards (Broadfoot & Ashkanasy, 1994; Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins & Klesh, 1979;; Seashore, Lawler, Mirvis & Lawler, Cammann, 1982). Extrinsic reward measures were designed to measure the employee's view of the economic rewards from his/her job. It includes pay, benefits, and job security. The scale also measured the degree to which intrinsic rewards such as recognition are present in the organisation.

28 Training and career development was measured via a four-item scale developed by Broadfoot and Ashkanasy (1994) which focused on whether the organisation expends sufficient effort in providing opportunities for people to develop their skills, and the adequacy of the training.

29 The five-item job design scale explored the challenge of the job via the five core job characteristics as described within the Job Diagnostic Survey (Hackman & Oldham, 1975).

30 Organisational commitment was measured using the abridged nine-item Organisational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) scale developed by Mowday, Steers and Porter (1979) in order to take into account criticism of the original 15-item scale (see O'Reilly & Chatman, 1986 and Reichers, 1985). Compared to other measures of employee commitment, the OCQ has received the most thorough and generally positive evaluation (Meyer & Allen, 1997). The scale draws, upon Angle and Perry's (1981) classification of commitment into two components: 1) affective commitment and 2) calculative commitment.

Data Analysis Procedures

31 A two-step approach was undertaken for the data analysis. First, the measures used in the study were validated via a factor analytical process and the computation of Cronbach's (1951) alpha. Second, the relationships amongst the study variables were examined via the preparation of a correlation matrix and further tested via a hierarchical regression analysis.

32 The hierarchical regression analysis was run in order to identify that group of independent variables useful in predicting the dependent variable, and to eliminate those independent variables that do not provide any additional prediction to the independent variables already in the equation (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001).

33 Demographic factors were included as control variables in the regression equation, as the first step. The independent variables consisted of eight factors grouped into two sets or bundles (i.e. HR factors and organisational factors). Organisational factors were entered as the second step in the equation and the human resource bundle practices were entered as Step3.

34 Previous studies (Macduffie, 1995: Wright, Dunford & Snell, 2001) support the notion that practices within bundles are interrelated and the combined impact of practices in a bundle could be specified in two simple alternatives: an additive approach and a multiplicative approach. Statistically, the additive combination of practices has the desirable property that the sum of normally distributed variable scores is still normally distributed, which is not true for the multiplicative product. Conceptually, a multiplicative relationship implies that if any single organisational practice is not present, the "bundle” score (and effect) should be zero. However, Osterman (1994) argues that, "although practices in a bundle are expected to be interrelated, the absence of a particular practice will not eradicate the effect of all other practices, but will weaken the net effect of the bundle” (p. 176.). This study has adopted the additive approach in the interests of parsimony.

35 Statistically it also makes sense to separate out these bundles in this way to show the true effect. Regression is best when each IV is strongly related to the DV but uncorrelated to other variables (Tabachnik & Fidell, 2001). Thus the regression solution is extremely sensitive to the combination of variables that is included in it. Whether or not independent variables (IVs) appear particularly important in a solution depends upon the other IVs in the set. As such, this approach will allow some conclusions as to the efficacy of organisational versus HR practices in impacting the retention of core staff.

Results

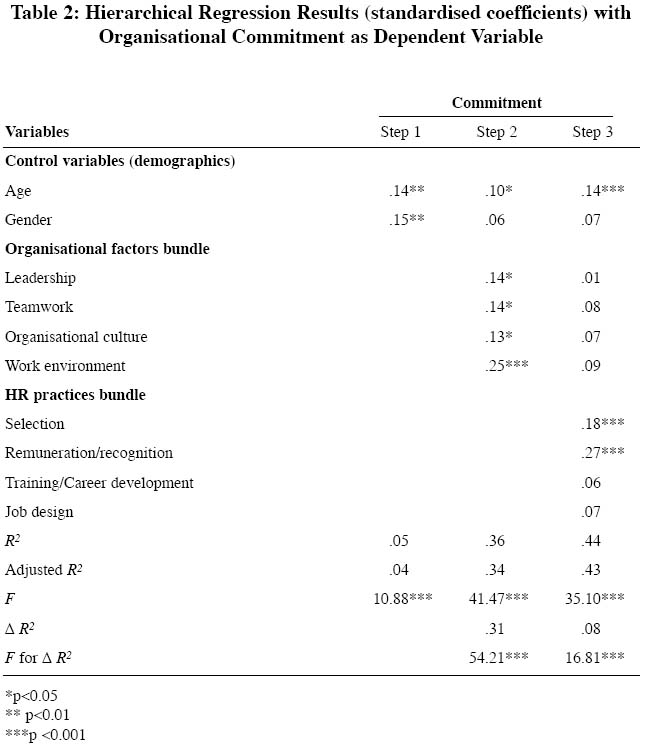

36 Descriptive statistics, reliabilities and correlations are presented in Table 1. The standard deviations of the main study variables ranged from 1.06 to 1.58, suggesting that none of the measures were marked by excessive restrictions in range.

37 The correlation matrix presented in Table 1 revealed that all eight independent variables have significant positive correlations with organisational commitment. The direction of the association ranged from r= 0.42 to r=0.66. These results indicate no multi-co linearity and singularity problems.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations for all variables (n=457)

Display large image of Table 1

38 The demographic variables showed only weak associations with the commitment dimension. However, both age (r= .17, p<0.001) and gender (r =.18, p<0.001) were positively and significantly correlated with organisational commitment. Occupation and industry had no significant relationship with commitment and were removed from further analysis. This result may be, in part, an outcome of the various industry groups that were represented amongst the data set (Green, 1991). However, as the size of the industry sub-sets were small, this was not analysed further, but does present an area for future investigation.

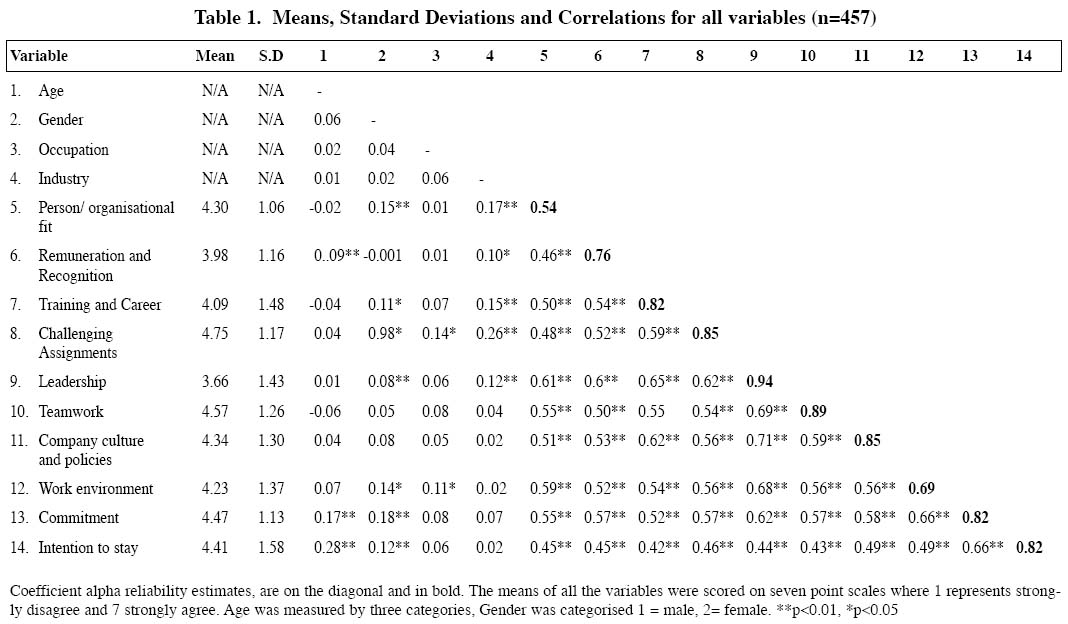

39 Age and gender were the control variables included in all the regression analyses. The results of the hierarchal regression analysis are presented in Table 2.

40 Table 2 shows that the demographic features of age and gender had a significant affect on commitment in Step 1. However, this effect was rendered insignificant for gender when the organisational bundle was included at Step 2 of the regression. Whereas the organisational factors all contributed to explaining over 30% of the variance in commitment at Step 2, no organisational factor variables showed a significant relationship with commitment at Step 3. At initial glance therefore, it appears that human resource practices fully mediate the influence of organisational factors on commitment. The addition of the HR bundle explained a further 8% of the variance in commitment. This is an important result in that it suggests that it is HR practices which will influence commitment of core employees rather than other organisational features. However, closer inspection of Table 2 reveals that only two HR practices, selection, and reward and recognition are statistically significant predictors of commitment.

Table 2: Hierarchical Regression Results (standardised coefficients) with Organisational Commitment as Dependent VariableDiscussion

41 Past studies revealed that employees interpret human resource practices as indicative of the personified organisation's commitment to them (Eisenberger, FasoloDavis-LaMastro, 1990; Settoon, Bennett & Liden, 1996). They reciprocate their perceptions accordingly in their own commitment to the organisation. Some researchers suggest that for positive work experiences to increase commitment significantly, employees must believe that such work experiences are a result of effective management policies (Parker & Wright, 2001). The findings of this study have therefore provided further empirical evidence to support these claims. However, this study has in particular revealed two HR practices - selection (person-job fit) and remuneration and recognition as instrumental in influencing commitment over and above other HR and organisational factors.

42 Essentially, the findings suggest that people who are well suited for the job and/or organisation, are more likely to feel attached and committed to the organisation. The concept of organisational fit (Brown, 1969; Kidron 1978; Steers 1977; Weiner, 1982) identifies convergent goals and values between the individual and the organisation as an important predictor of affective commitment.

43 Lauver and Kristof-Brown (2000) found that both person-job fit and person organisation fit predicted job satisfaction; however, person organisation fit was a better predictor of intention to quit. Thus, people who are not well suited for the job and /or organisation are more likely to leave than those who have a good person-job or person-organisation fit. Lee, Ashwood, Walsh and Mowday (1992) espoused that an employee's satisfaction with a job, as well as propensity to leave that job, depends on the degree to which the individual's personality matches his or her occupational environment. This implies that the organisation should not only match the job requirements with person's KSA but should also carefully match the person's personality and values with the organisation's values and culture (Kristof, 1996; Rhoades, Eisenberger & Armeli, 2001;Van Vianen, 2000).

44 This study also revealed that rewards and recognition play a key role in the commitment of core staff. A fair wage is the cornerstone of the contractual and psychological agreement between employees and employers (McCallum, 1998; Parker & Wright, 2001). A number of recent studies have highlighted the rewards-retention link (Mercer, 2003; Tower Perrin, 2003; Watson Wyatt, 1999). In particular, studies by Bassi and Van Buren (1999); Boyd and Salamin (2001); Stein (2000); Williams (1999) have revealed that companies which provide remuneration packages superior to the market for critical talent including special pay premiums, stock options, or bonuses can expect greater organisational commitment.

45 Although remuneration provides recognition, other forms of non-monetary recognition are also important for the core employee group. Employees tend to remain with the organisation when they feel their capabilities, efforts and performance contributions are recognised and appreciated (Davies, 2001). Recognition from managers, team members, peers and customers has been shown to enhance commitment (Walker, 2001). Particularly important to the employees are opportunities to participate and to influence actions and decisions (Davies, 2001; Gold, 2001). Overall this finding supports that employers need to increase their commitment to the use of rewards as essential elements of talent management programs. It appears therefore that it is important for companies to use their reward budget effectively to differentiate the rewards of the top performers, thus driving an increase in the return on investment (ROI) on human capital investments.

46 The study also showed a significant and positive relationship between age and organisational commitment, irrespective of other organisation and HR factors. This finding is consistent with previous research (Alutto, Hrebiniak & Alonso 1973; Cohen & Lowenberg, 1990). Mathieu and Zajac (1990) found that age was significantly more related to affective commitment than to continuance (calculative) commitment. Tenure was excluded from this study because studies by Meyer and Allen (1997) supported that employees' age may be the link between tenure and affective commitment. Werbel and Gould (1984) revealed an inverse relationship between organisational commitment and turnover for nurses employed more than one year, but Cohen (1991) indicated that this relationship was stronger for employees in their early career stages (i.e. up to thirty years old) than those in later career stages.

47 There are a number of limitations of the study however, which need to be acknowledged. It is important to recognize that other antecedents of commitment not measured in this study including the lack of available alternative employment opportunities (Meyer & Allen, 1991) and magnitude or number of investment lost in leaving the organisation (Rusbult & Farrell, 1983) may impact upon the results. Future research taking into account these variables would therefore be useful.

48 Clearly, there is a need for greater analysis of the organisational and human resources factors identified. For example, other aspects of the work environment other than those that were measured in this study, such as formal-isation, role ambiguity, and instrumental communication should be examined.

49 Furthermore, the study only examined the additive effects of the bundles, perhaps the interactive effects of the practices would provide a better and more fine-grained understanding of the interrelationships among these variables which would serve to illuminate and provide further insights for academics and practitioners.

50 Previous research has indicated that commitment is linked to lower turnover rates (Mowday, Porter & Steers, 1982; Steers, 1977), and increased intention to stay with the firm (Singh & Schwab, 2000). Therefore, further studies examining this notion would also be useful.

51 This study only examined the education, health care and public sector industries, future research will need to confirm to what degree the link between organisational practices, commitment and retention does also exist for other industries.

52 In conclusion, this study provides a useful platform from which to test the complex issues underlying the retention of core staff through HR practises. The study goes some way in promoting high performance strategic human resource management practices which focus on selection, remuneration and recognition strategies as means of improving commitment to the organisation. This may be an important finding in combating the effect of the current skills shortages as organisations battle to get the most from their existing people. Strategic human resource management may then be able to tip the balance towards being perceived as a business partner.

References

Accenture, (2001). The high performance workforce: separating the digital economy's winners from losers. The Battle for Retention, 1-5.

Agarwala, T. (2003). Innovative human resource practices and organizational commitment: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Human Resource Management 14(2), 175-197.

Allan, P. (2002). The contingent workforce: challenges and new directions. American Business Review, 20 (12), 103-11.

Allan, P. & Sienko, S. (1997). A comparison of contingent and core workers' perceptions of their jobs' characteristics and motivational properties. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 62(3), 4-11.

Allen, N. (1996). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organisation: an examination of construct validity. Journal of Vocational Behaviour 49(3), 252-76.

Alluto, J.A. Hrebiniak, L.C. and Alonso, R.C. (1973). On operationalising the concept of commitment. Social Forces, 51,. 448-54.

Angle, H.L. and Perry, J.L. (1983). Organisational commitment: individual and organisational influences. Work and Occupations, 10, 123-46.

Arthur, J. (1994). Effects of human resource systems on manufacturing performance and turnover.' Academy of Management Journal, 37, 670-87.

Aven, F.F., Parker, B., & McEvoy, G.M. (1993). Gender and attitudinal commitment to organizations: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business Research, 26,, 63-73.

Baron, J.N., & Kreps, D. (1999). Consistent human resource practices. California Management Review, 41(3), 29-31.

Barner, R (1994, September - October). The new career strategist: career management for the year 2000 and beyond. The Futurist, 28(5), 8-15.

Bass, B.M., & Avolio, B.J. (1995). The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Mind Garden, Palo Alto, CA.

Bassi, L.J., & Van Buren, M. E.(1999, January). Sharpening the leading edge. Training & Development, 53(1), 23-32.

Beck, S.(2001). Why Associates Leave, and Strategies To Keep Them. American Lawyer Media, 5(2), 23-27.

Becker, B., & Gerhart, B. (1996). The impact of human resource management on organisational performance: Progress and prospects. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 779-801.

Becker, B.E., & Huselid, M.A. (1998). High performance work systems and firm performance: A synthesis of research and managerial implications. Personnel and Human Resource Management, 16, 53-101.

Boyd, B.K., & Salamin, A. (2001). Strategic reward systems: a contingency model of pay system design. Strategic Management Journal, 22 (8), 777-793.

Bozeman, D.B., & Perrewe, P.L. (2001). The effect of item content overlap on Organisational Commitment Questionnaire - Turnover Cognitions Relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1),16-25.

Broadfoot, L.E., & Ashkanasy, N.M. (1994, April). A survey of organizational culture measurement instruments. Paper presented at the Annual General Meeting of Australian Social Psychologists, Cairns, Queensland, Australia.

Brown, M.E. (1969). Identification and some conditions of organizational involvement. Administrative Science Quarterly, 15, 346-355.

Cable, D.M., & Judge, T.A. (1997). Interviewers' perceptions of person organization fit and organisational selection decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 546-561.

Cammann,C.,Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1979). The Michigan Organisational Assessment Questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Cappelli, P. (1999). The New Deal at Work: Managing the Market-Driven Workforce. Boston: Harvard Bus. Sch. Press.

Cappelli, P. (2000). A market driven approach to retaining talent. Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 103-111.

Chew, J. (2003). Defining Core Employees: An Exploration of Human Resource Architecture. Paper presented at ANZAM conference, Fremantle, Western Australia.

Chew, J., & Entrekin, L. (2004). Retention Management of Critical (core) Employees: A challenging issue confronting organisations in the 21st century. International Business and Economic Research Journal.

Clarke, K.F. (2001). What businesses are doing to attract and retain employee -becoming an employer of choice. Employee Benefits Journal, 3, 34-37.

Cohen, A. (1991). Career stage as a moderator of the relationships between organizational commitment and its outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 64, 253-268.

Cohen, A., and Lowenberg, G. (1990). A re-examination of the side bet theory as applied to organisational commitment: a meta analysis. Human Relations, 43(10), 1015-1051.

Cronbach, L.H. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334.

Dalessio, A., Silverman, W.H., & Schuck, J.R. (1986). Paths to turnover: a re-analysis and review of existing data on the Mobley, Horner and Hollingworth Turnover Model. Human Relations, 39(3), 264-270.

Davies, R. (200, April 19). How to boost Staff Retention? People Management, 7(8), 54-56.

Delaney, J., & Huselid, M. (1996). The impact of HRM practices on perceptions of organizational performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 949-969.

Delery, J.E. (1998). Issues of fit in strategic human resource management: implications for research. Human Resource Management Review, 8, 289-309.

Dunham, R.B., Grube, J.A., & Castaneda, M.B.(1994). Organizational commitment: the utility of an integrative definition. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79,370-380.

Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P., & Davis-LaMastro, V. (1990). Perceived organisational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, (1), 51-59.

Finegan, J.E. (2000). The impact of person and organisational values on organisational commitment. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73 (2), 149-154.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief Attitude, Intention, Amid Behaviour, Reading, MA: Addison, Wesley.

Fitz-enz, J. (1990, August). Getting and keeping good employees. Personnel, 67(8), pp. 25-29.

Furnham, A. (2002). Work in 2020 Prognostications about the world of work 20 years into the millennium. Journal of Managerial Psychology,15 (3), 242-50.

Gold, M. (2001, Spring). Breaking all the rules for recruitment and retention. Journal of Career Planning & Employment, 61(3), 6-8.

Gramm, C.L., & Schnell, J.F (2001, January). The Use of Flexible staffing arrangements in core production jobs. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 54 (2), 245-251.

Griffeth, R.W., Hom, P.W., Gaertner, S. (2000, May-June). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: update, moderator tests and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26 (3), 463-472.

Green, S.B. (1991). How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis? Multivariate Behavioural Research, 26, 499-510.

Grusky, O. (1966). Career mobility and organizational commitment. Administrative Science Quarterly 10, 488-503.

Gumbus, F.L., & Johnson, C.R. (2003). Employee Friendly Initiatives at Futura. Leadership Survey, certification and a Training Matrix, and an Annual Performance and Personal Development Review.

Hackman, R.J., & Oldham, G.R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60 (2),159-170.

Handy, C. (1995). Trust and the virtual organisation. Harvard Business Review, 73 (3), 40-50.

Hartog, D.N., Van Muijen, J.J., & Koopman, P.L. (1997). Transactional versus transformational leadership: an analysis of the MLQ (Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire). Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(1),19-35.

Hays, S.W., & Kearney, R.C. (2001, September). Anticipated changes in human resource management: views from the field. Public Administration Review, 61(5), 585-592.

Huselid, M. A.(1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38,635-672.

Ichniowski, C., Shaw, K., & Prennushi, G. (1997). The effects of human resource management practices on productivity.' In American Economic Review, 87, 291-313.

Jamrog, J.J., & Overholt, M.H. (2004). Building a strategic HR function: Continuing the Evolution. Human Resource Planning, 27 (1). 51-62.

Kalleberg, A.L. (2000). Non-standard employment relations: part-time, temporary and contract work. Annual Review of Sociology, 341-45.

Kidron, A. (1978). Work values and organisational commitment. Academy of Management Journal, 21, 239-247.

Ko, J.J.R. (2003). Contingent and internal employment systems: substitutes or complements. Journal of Labor Research, 24(3), 473-491.

Kristof, A.L. (1996). Person-organisation fit: an integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49, 1-49.

Lambert, E.G., Hogan, N.L., & Barton, S.M. (2001. The impact of job satisfaction on turnover intent: a test of structural measurement model using a national sample of workers. The Social Science Journal, 38 (2), 233-243.

Lauver, K.I.J., & Kristof-Brown, A. (2001). Distinguishing between employees' perceptions of person-job and person-organisation fit. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 59, 454-470.

Lawler, E.E.III., & Mohrman, S.A., (2003). HR as a strategic partner: What does it take to make it happen? Human Resource Planning, 26 (5), 15-29.

Lee, T.W., Ashford, S.J., Walsh, J.P., & Mowday, R.T. (1992). Commitment propensity, organizational commitment, and voluntary turnover: a longitudinal study of organizational entry processes. Journal of Management, 18,15-26.

Macduffie, J. (1995). Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance: organisational logic and flexible production systems in the world auto industry. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 48,197-221.

Marchington, M., & Grugulis, I. (2000). Best Practice Human Resource Management. Opportunity or dangerous illusion? International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11 (6), 1104-1124.

Mathieu, J., & Zajac, D. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organisational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 171-194.

McCallum, J. S. (1998, Summer). Involving Business. Ivey Business Quarterly, 62(4), 65-68.

Mercer Human Resource Department Report. (2003, May). Mercer study rais es red flags for employer pay and benefit plans (findings of the 2002 People at work survey. (8-15).

Meyer, J.P., & Allen, N.J. (1991). A three component conceptualisation of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review,1, 89-93.

Meyer, J.P., & Allen, J.J. (1997). Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Morita, J.G., Lee, T.W., & Mowday, R.T. (1989, April). Introducing survival analysis to organisational researchers: a selected application to turnover research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(2), 280-293.

Mowday, R.T., Porter, L.W., & Steers, R.M. (1982). Employee-organisational Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover. New York: Academic Press.

Netemeyer, R.G., Boles, J.S., McKee, D.O., & McMurrian, R. (1997). An investigation into the antecedents of organisational citizenship behaviors in a personal selling context. Journal of Marketing, 61, 85-98.

Oakland, S., & Oakland, J.S. (2001, September). Current people management activities in world-class organisations. Total Quality Management, 12(6), 773-779.

O'Reilly, C.A., Chatman, J., & Caldwell, D.F. (1991). People and organizational culture: a profile comparison approach to assessing person organisation fit. Academy of Management Journal, (34), 487-516.

Osterman, P. (1994). How common is workplace transformation and who adopts it? Industrial and Labour Relations Review, 47(2), 173-188.

Parker, O., & Wright, L. (2001, January). Pay and employee commitment: the missing link. Ivey Business Journal, 65(3), 70-79.

Pfeffer, J. (1998). The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Pfeffer, J. (1998, Winter). Seven practices of successful organisations. California Review, 40(2), 36-155.

Pils, F.K., & Macduffie, J.P. (1996). The adoption of high involvement work practices. Industrial Relations, 35(3), 423-455.

Powers, E.L. (2000, Summer). Employee loyalty in the New Millennium. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 65(3), 4-8.

Reichers, A.E. (1985). A review and reconceptualisation of organisational commitment. Academy of Management Review, 10, 465-476.

Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., & Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: the contribution of perceived organisational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 825-836.

Robinson, S.L., Kraatz, M.S., & Rousseau, D.M. (1994). Changing the obligations and the psychological contract. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 437-452.

Rusbult, C.E., & Farrell, D. (1983, August). A Longitudinal test of the investment model: The impact on job satisfaction, job commitment and turnover of variations in rewards, costs, alternatives and investments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(3), 429-439.

Sheridan, J.E. (1992, December). Organizational culture and employee retention. Academy of Management Journal, 35(5),1036-1057.

Scholl, R.W. (1981, October). Differentiation organizational commitment from expectancy as a motivating force. The Academy of Management Review, 6(4) 589-600.

Seashore, S.E., Lawler, E.E., Mirvis, P., & Cammann, C. (1982). Observing and Measuring Organizational Change: A Guide to Field Practice. New York: Willey.

Setton, R.P., Bennett, N., & Liden, R. (1996). Social exchange in organizations: perceived organizational support, leader-member exchange, and employee reciprocity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 219-227.

Shaw, J.D., Delery, J.E., Jenkins, G.D., & Gupta, N. (1998). An organization-level analysis of voluntary and involuntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 511-525.

Singh, D.A., & Schwab, R.C. (2000, June). Predicting turnover and retention in nursing home administrators: management and policy implications. The Gerontologist, 40(3), 310-320.

Smith, F.J. (1976). Index of organisational reactions. JSAS Catalogue of Selected documents in Psychology, 6(1), 54, No 1265.

Snell, S., & Dean, J. (1992). Integrated manufacturing and human resource management: a human capital perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 467-504.

Steers, R.M. (1977, 22 March). Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 53, 36-39.

Stein, N. (2000, May). Winning the war to keep top talent: Yes you can make your workplace invincible! Fortune, 141(11), 132-138.

Tabachnick, B.G., & Fidell, L.S. (2001). Using Multivariate Statistics. (4th edition), New York: Harper Collins College Publishers.

Tower Perrin. (2003, January). Rewards: the not-so-secret ingredient for managing talent. (Retention). HR Focus, 80(1), 3-10.

Ulrich, D. (1998). Intellectual capital equals competence x commitment. Sloan Management Review, 39, 15-26.

Van Vianen, A.E.M. (2000, Spring). Person organisation fit: The match between newcomers and recruiters preferences for organizational cultures. Personnel Psychology, 53(1), 113-122.

Wagar, T.H. (2003, February). Looking to retain management staff? Here's how HR makes a difference. Canadian HR Reporter.

Wahn, J.C. (1998). Sex differences in the continuance component of organizational commitment. Group and Organization Management, 23(3), 256-266.

Walker, J.W. (2001, March). Perspectives. Human Resource Planning, 24(1), 6-10.

Watson, Wyatt. (1999). Work USA 2000: Employee Commitment and the Bottom Line. Bethesda, MD: Watson Wyatt.

Werbel, J.D., & Gould, S. (1984). A Comparison of the Commitment-Turnover Relationship in Recent Hires and Tenured Employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64, 687-693.

Whitener, E.M. (2001, September-October). Do "high commitment” human resource practices affect employee commitment? A cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear modelling. Journal of Management, 27(5), 515-564.

Wiener, Y. (1982). Commitment in organizations: a normative view. Academy of Management Review, 7, 418-428.

Wiens-Tuers, B.A. (2001, March). Employee attachment and temporary workers. Journal of Economic Issues, 35,(1), 45-48.

Williams, K. (1999). Rewards encourage loyalty and increase performance. Strategic Finance, 81(6), 75-82.

Wood, S., & De Menezes, L. (1998). High commitment management in the U.K.: evidence from the workplace industrial relations survey and employers' manpower and skills practices survey. Human Relations, 51, 485-415.

Wright, P., Dunford, B.B., & Snell, S.A. (2001). Human resources and the resource based view of the firm. Journal of Management, 27 (6), 701-721.

Youndt, M.A., Snell, S.A., Dean, J.W., and Lepak, D.P. (1996). Human resource management, manufacturing strategy, and firm performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 836-865.

Endnotes