An e-Business Logistic Model in Taiwan

Edward Y.H. LinNational Taipei University of Technology, Taiwan

Ming-Kuen Chen

National Taipei University of Technology, Taiwan

Wei-Chi Jiang

National Taipei University of Technology, Taiwan

The current article develops a framework for an e-business logistic model in Taiwan. The model includes e-marketplace, logistic, organization, and informational systems factors. Data used for this research come from a survey of business groups, including marine and air carriers, terminal warehousing, custom brokers, shipping centers, and marine information service providers. Our study reveals relationships between essential variables for e-business trading in the logistic industry. These include organizational advantage and information technology, strategy and vision, consumer-directed service and planning, lower cost and high quality customer service, quick merchandise delivery and low inventory, and long-term development plans. Specifically, we found that the logistic industry in Taiwan ignores the details of purchasing procedure in e-marketplace operation, focusing more on actual merchandise delivery, consumer satisfaction, and downstream consumer service. In addition, the logistical industry in Taiwan also involves employee adjustment to the new environment, support from upper management, training and, application of information technology.

Introduction

1 The widespread use of the World Wide Web (WWW) in recent years has greatly facilitated the development of e-commerce, which in turn has affected the traditional business model and caused profound change in the business world. The high growth potential of the WWW has meant that business is eager to use e-market trading. Much research has been conducted to this end. Kalakota and Robinson (2002) define e-market trading as a massive gathering of buyers and sellers under the automatic trading procedure that can reduce the trading cost for both sides. It expends buyers’ options for better products and services and opens new markets and customers for sellers. Bakos and Yannis (1991), McFarland (1994) and O’Brien (2002) describe e-market trading as a platform of buyers and sellers exchanging products and cash through inter-organizational information systems and trading mechanisms. Goldman (1999), Sharp (1997), and Wright and McMahan (1992) define e-market trading simply as a B2B online operation.

2 The key factor for the success of current e-marketplace trading is not based on real-time information delivery, multiple services or lower cost, but the fast and error-free delivery of merchandise. The logistic industry thus plays an important role by connecting producers, consumers, manufactures, and retailers together for common benefit. Regulated by government policies, logistic flow in business-trading is created by manufacturers and consumers to transport real products through a set of managed procedures such as warehousing, transportation, loading/unloading, packing, assembling, labeling, re/co-packing, and marketing. It ultimately creates the added-values to satisfy the needs of customers, industry and society at large. Ballou (1992), Johnson and Wood (1996), Kalakota and Whinston (1996), and Shapiro and Heskette (1985) define shipping flow as the management of transporting raw material, semi-product, and products from factories to consumers. Ratliff and Nulty (1996) define shipping flow to include all activities from ordering, packing, transporting, storing, servicing, and information processing of supply chain products. Coyle (1996), Cooke (1997), Prahalad and Hamel (1993), Stank and Daugherty (1997), Simchi et al. (2001), and Weber et al. (2000) further define shipping flow to include all operations such as R&D, manufacturing, transportation, storage, inventory management, post-sale service, documentation, and the price billing process in connection with delivery from raw material to end product at the consumer end. Copacino (2001) describes the third party shipping flow as an external company that provides the shipping function for work-in-process or finished goods.

3 The effective connection of virtual e-trading and real merchandise delivery is a key factor in the rapid success of e-commerce. E-marketplace trading has become an important territory for the logistic industry to explore. The logistic industry in Taiwan is still in the beginning stages with respect to e-market trading. How to effectively establish conditions, conduct analysis, and investigate other concerns related to logistic models of successful e-market trading has become an urgent issue for Taiwan’s future e-commerce. This study explores relationships between e-marketplace, logistic, organization, and information systems. Based on the results of a questionnaire survey from various logistic companies in Taiwan, including marine and air carriers, terminal warehousing, custom brokers, shipping centers, and marine information service providers, we propose an e-business logistic model to simulate the relationship between essential factors for the logistic industry in Taiwan.

Methods

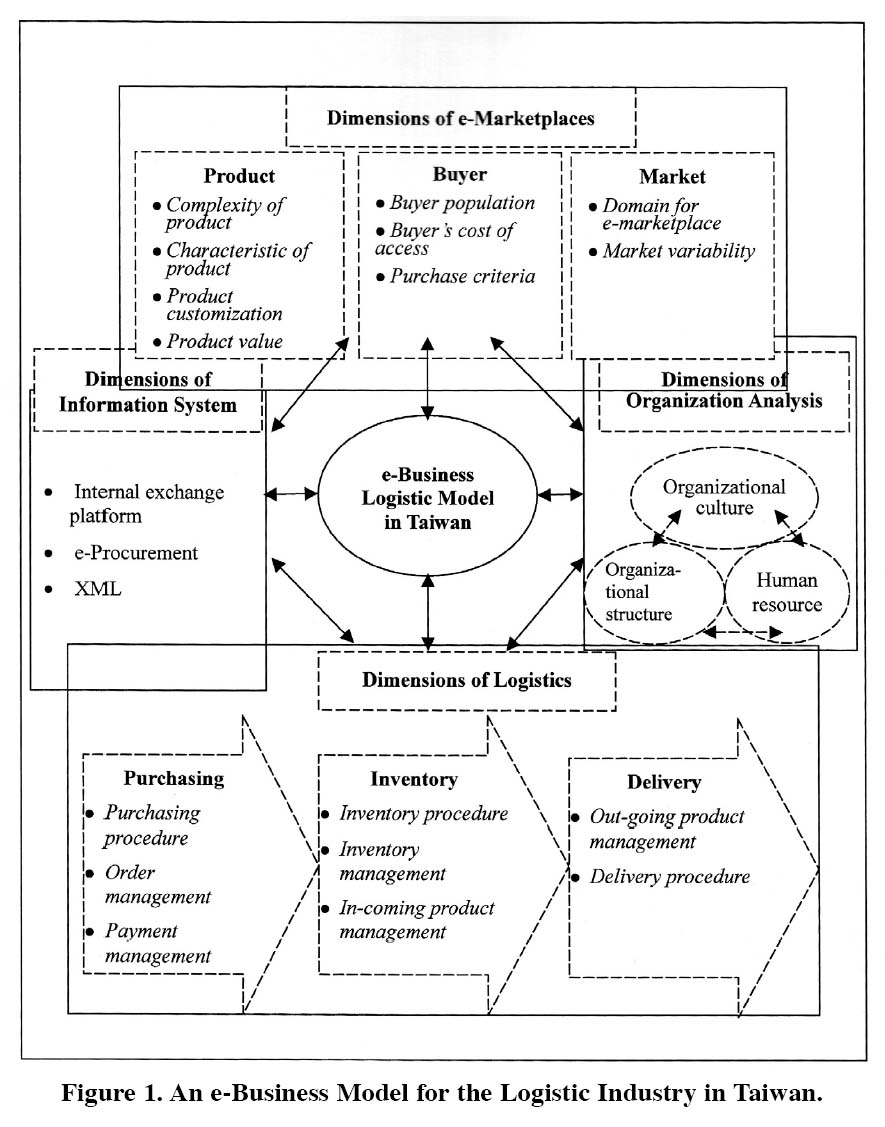

4 The preliminary e-business model we developed for the logistic industry in Taiwan is shown in Figure 1. The dimensions of this model as described in Table 1 include e-marketplace, logistic, organization analysis, and information systems. We have analyzed the effectiveness and magnitude of the influence from each of the above factors on the e-business logistic model.

Dimensions of e-Marketplace

5 This dimension provides supporting services for one to multiple, or multiple to multiple, trading activities in order to reduce cost and improve operational efficiency. The sub-dimensions in this area include:

-

Product (Benjamin and Wigand, 1995; Kalakola and Whinston, 1996; Malone et al., 1987; Williamson, 1991)

- Complexity of product is based on the pricing and capital specialty to determine the probability of logistics in e-marketplaces.

- Characteristic of product is a set of factors that are important for buyers to use the e-marketplace for a special product.

- Product customization adjusts the method of delivery service for different products to improve delivery efficiency.

- Product value depends on development, creativity, and post-sale service.

-

Buyer (Bakos and Yannis, 1991; Matthyssens and Van den Bulte, 1994)

- Buyer population is influenced by the fact that higher transaction and communication costs generate a higher demand for use of e-marketplaces.

- Buyer’s cost of access is defined by the cost of searching for information with regard to sellers and products.

- Purchase criteria includes all factors of selecting sellers that may affect a buyer’s profit.

-

Market

- Domain for e-marketplace is the domain for buyers and sellers to realize cooperation, transactions, and information exchange.

- Market variability reveals the difficulties of both buyer and seller in accessing information.

Figure 1. An e-Business Model for the Logistic Industry in Taiwan.

Dimensions of Logistics

-

Purchasing (Edward and Frazelle, 2002; Gopal and Cypress, 1993; Kalakola and Robinson, 2002; O’Brien, 2002; Poole and Durieux, 1999)

- Purchasing procedure covers all activities needed to maintain normal operations for a company in order to satisfy a customer’s desire for products in the procurement of raw material, parts, or finished products.

- Order management refers to the technique of using information technology to effectively communicate with customers regarding inquires and orders.

- Payment management manages the functions of payment for both buyer and sellers by using e-marketplaces to save time and cost.

-

Inventory (Edward and Frazelle, 2002)

- Inventory procedure manages the product through inventory checking and the use of storage space for inventory control.

- Inventory management uses information technology to provide up-to-date information to reduce inventory level.

- In-coming product management manages all activities using information technology to exam the in-coming products for necessary processing.

-

Delivery (Benjamin and Wigand, 1995; Edward and Frazelle, 2002: Kalakola and Robinson, 2002)

- Out-going product management manages all activities using information technology to exam products for out-going readiness, and to move products towards the out-going ready zone.

- Delivery procedure involves all activities related to processing orders through the e-marketplace and the delivery of products from manufacturers or producers to the customers.

Dimensions of Organization Analysis

- Organizational culture Organizational culture is a common belief in an organization that affects its employees’ behavior at work. (Hodgetts, Luthans and Slocum,1999) It is viewed as a group behavior with consensus and understanding that brings together group resources towards a constructive organization goal (Peters and Waterman, 1982).

- Organizational structure (Grover and Goslar, 1993; Gopal and Gypress, 1993: Hodgetts et al., 1999) Organizational structure is described as a combination of work division and cooperation within an organization in spiritual or physical deployment. It is defined as a special relationship among inter-related groups that share common goals.

- Human resources (Hartenstein, 1988; Wright and McMahan, 1992) Human resources emphasize arranging the activities of an organization in order to achieve its goal. It includes a series of management activities within an organization including recruitment, training, career development, and career planning.

Dimensions of Information System

6 Kalakota and Robinson (2002) define an information system as inter-organizational information sharing. Davenport et al. (1996) and O’Brien (2002) describe information systems as a system that uses information and communication technology to perform inter-organization operations. It combines necessary resources using employees and communication networks to collect, exchange, and distribute information. Advantages of information system operations that can improve the information exchange and the development of e-marketplace are reported in the literature. Sub-dimensions in this area include:

- Information exchange platform that provides the technology and equipment needed for smooth operation in the e-marketplace.

- e-Procurement provides a system needed for smooth operations in the e-marketplace through a highly efficient computerized processing system.

- XML which represents an information management procedure needed for information transfer and sharing in the e-marketplace.

Results and Discussion

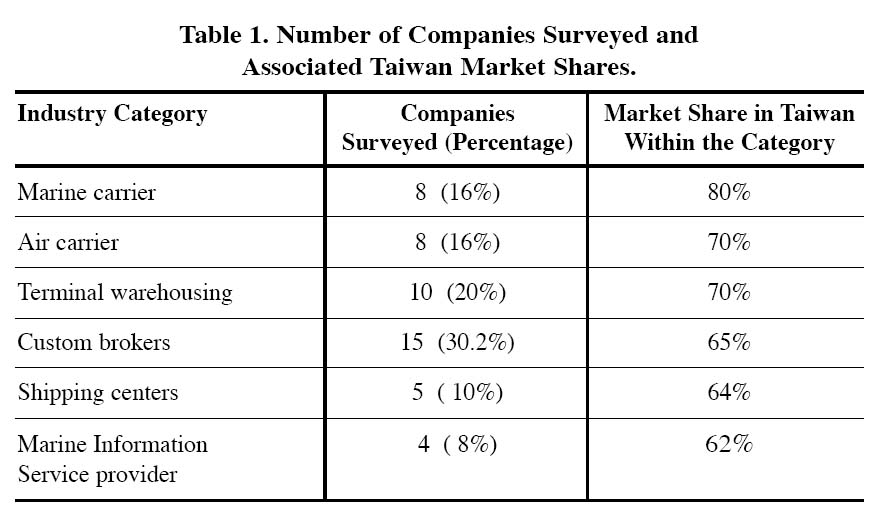

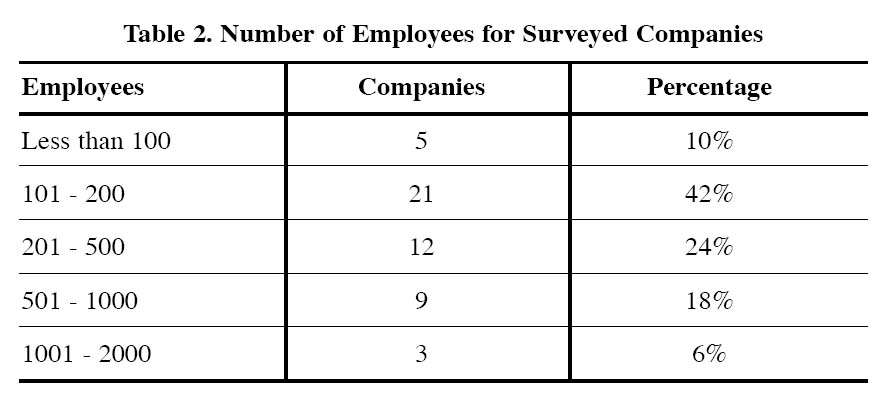

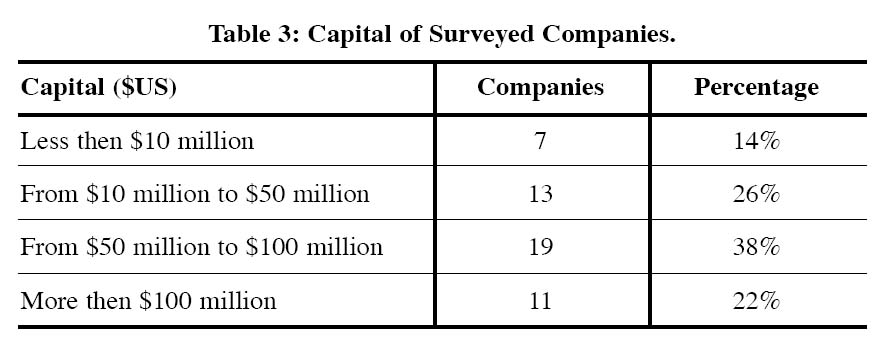

7 A questionnaire survey was conducted for logistic companies located in Taiwan with 75 respondents. Among these, 25 companies were not active in e-business trading and were thus excluded from the study. The breakdown of the remaining 50 companies in terms of their industry category and associated Taiwan market share is listed in Table 1. Table 2 and Table 3 reveal the frequency tables of the number of employees and capital amounts of these 50 surveyed companies, respectively.

Table 1. Number of Companies Surveyed and Associated Taiwan Market Shares.

Display large image of Table 1

Table 2. Number of Employees for Surveyed Companies

Display large image of Table 2

Table 3: Capital of Surveyed Companies.

Display large image of Table 3

8 SPSS was used for data analysis, including the analysis of reliability, multiple regression, Pearson product-moment correlation, one-way ANOVA, and factor analysis.

Reliability and Validity

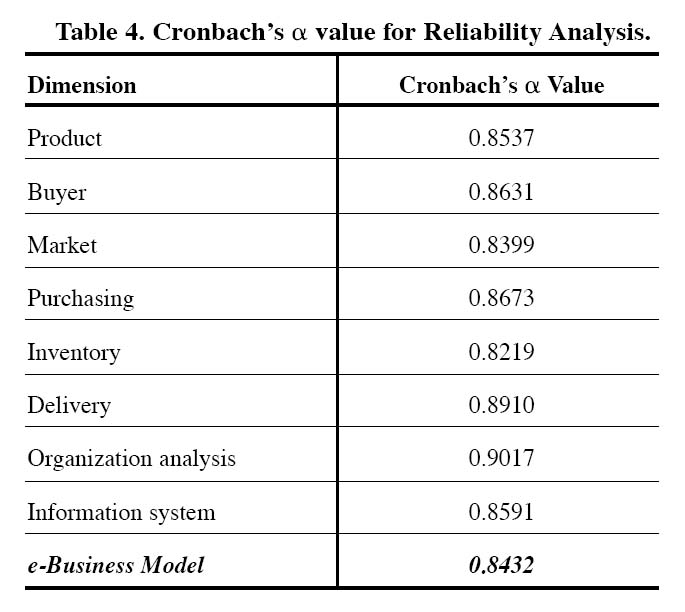

9 Reliability measures the exactness and accountability of the data collected. In order to reach a reasonable level of reliability, it is commonly believed that the standard reliability value of Cronbach’s should be at least greater then 0.5, or greater then 0.7, for high reliability standard (Nunnally, 1978). Cronbach’s value for reliability for each dimension in our logistic model is reported in Table 4. The overall reliability of the questionnaires collected in this research is 0.8432. Cronbach’s values for the rest of the measurements are at least greater then 0.8 which indicates the existence of internal consistency (Wright and McMahan, 1992). In addition to reliability, this research also follows the guidelines provided by O’Brien (2002) to maintain a reasonable level of validity.

Table 4. Cronbach’s α value for Reliability Analysis.

Multiple Regression

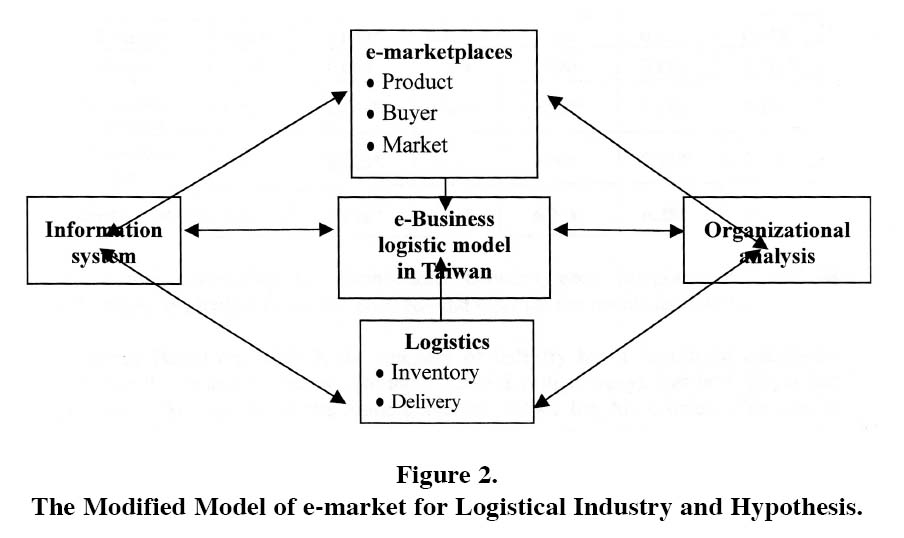

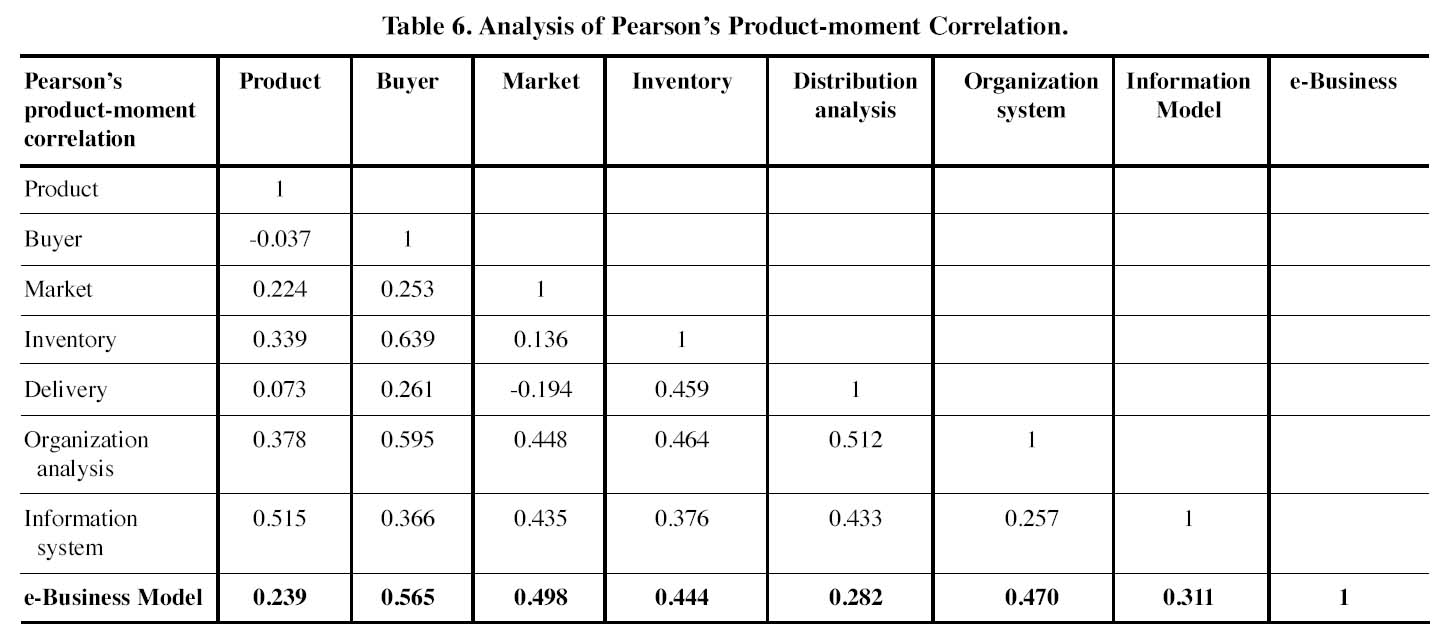

10 The e-business model that describes the operations as proposed by this research treats the logistic industry as a dependent variable. The eight independent variables and their significance tests are reported by SPSS in Table 5. At a significance level of 0.05 (5%), the results clearly show that Purchasing does not have enough evidence to warrant its significance on logistic industry. We would thus remove Purchase from the list of e-business operations in our model. After this modification, the resulting model is depicted in brief in Figure 2. Pearson’s product-moment correlation analysis is then conducted to examine the inter-relationships among the remaining seven independent variables and their respective impact on the model as a whole. The result of this analysis is reported in Table 6.

Table 5. Significance Test on Multiple Regression Analysis.

Display large image of Table 5

Table 6. Analysis of Pearson’s Product-moment Correlation.

Display large image of Table 6

11 From the last row in Table 6, the e-business logistic model in Taiwan appears to be affected more by (1) buyer’s behavior and environment (r = 0.565), (2) market domain and variability (r = 0.498), (3) organizational structure, culture, and quality of manpower (r = 0.47), and (4) inventory management procedures (r = 0.444). It is somewhat influenced by the information management system (r = 0.311), and is slightly influenced by both out-going product delivery system (r = 0.282) and product complexity, characteristic and value (r = 0.239). Table 6 also indicates that buyer’s behavior, market impact, inventory management, and delivery are closely related to the organizational structure and culture. It also reveals that the information system used is related to product, market, and delivery. Inventory, on the other hand, is closely related to both buyer’s behavior and product.

Figure 2. The Modified Model of e-market for Logistical Industry and Hypothesis.One-Way ANOVA Analysis

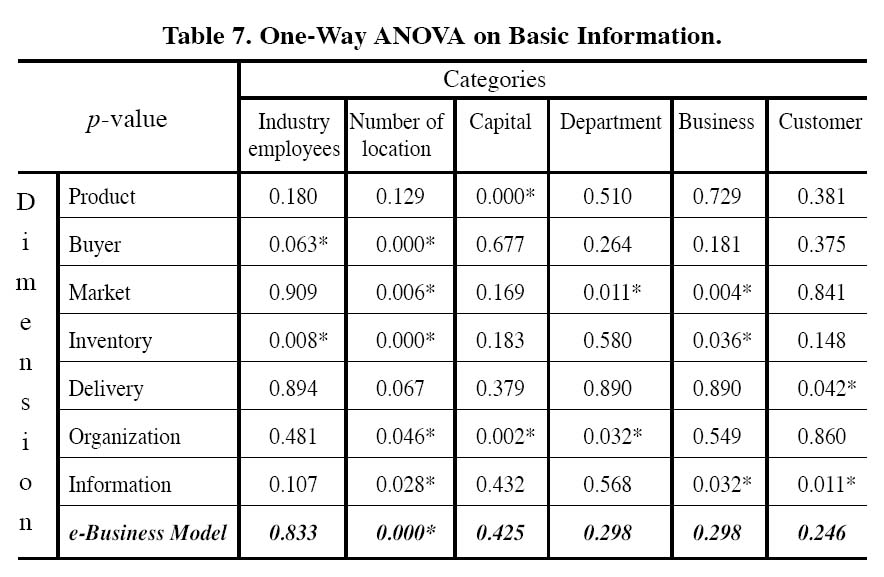

12 In order to determine whether the basic information in different groups may affect different attributes of the dimensions in our proposed e-business model, a one-way ANOVA was conducted with the results shown in Table 7. At a significance of 0.1 (10%), it is observed that for category is inter-related with at least a one dimension attribute (i.e., those with p-value < 0.1 as indicated by asterisk).

Table 7. One-Way ANOVA on Basic Information.

Display large image of Table 7

13 To further investigate the connections between each category item and its classifications, we looked into their averages and reported the results as follows:

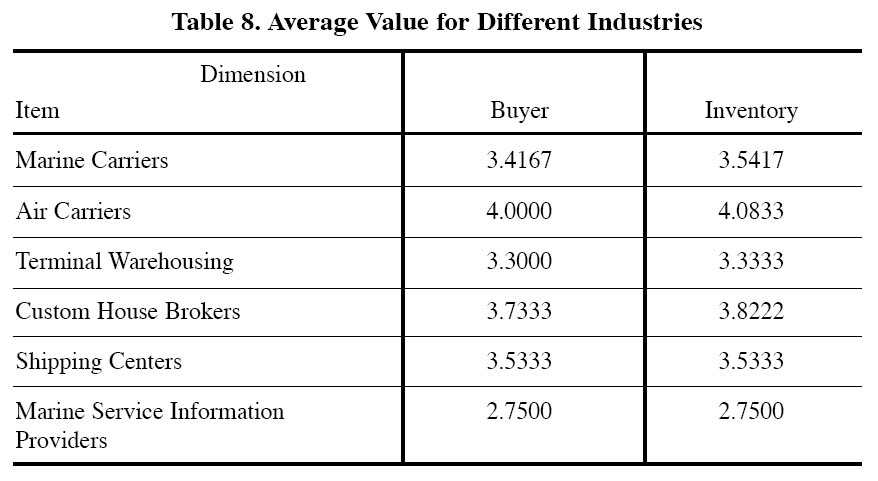

- Industry Based on Table 7, the category of Industry has a significant correlation between Buyer and Inventory (Storage). Table 8 further shows that both Buyer and Inventory (Storage) have the highest average values for Air Carrier. This can be explained because air carriers are the most sensitive in providing buyer service for information access in order to reduce cost and time in inventory (storage).

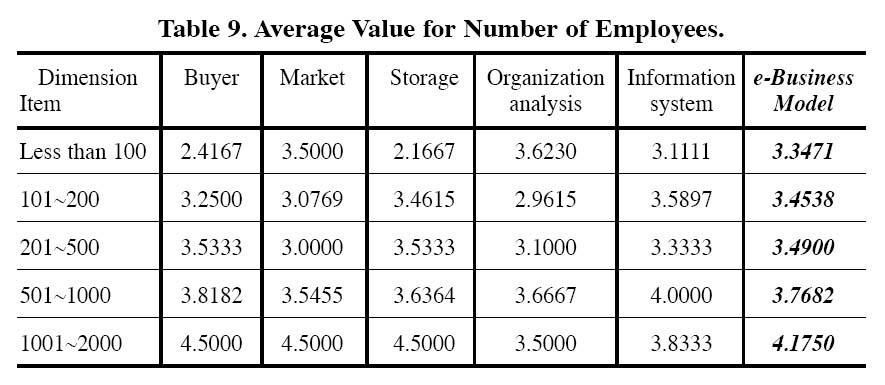

- Number of employees Table 7 indicates that Number of Employees has a significant correlation among Buyer, Market, Inventory (Storage), Organization Analysis, Information System, and e-Business Model. The average values in Table 9 indicate that Buyer, Market, Inventory (Storage), and e-Business Model have the highest values for companies with the number of employees between 1001-2000. On the other hand, Organization Analysis and Information System have the largest average values for companies with employees between 501-1000. This can be explained because it is easier for larger companies to lower costs by providing information to the buyers, thus, achieving customer satisfaction. They have better management in market change and inventory fluctuation. On the other hand, smaller and medium companies usually focus on the fineness of their information systems and in training their employees to achieve employee loyalty.

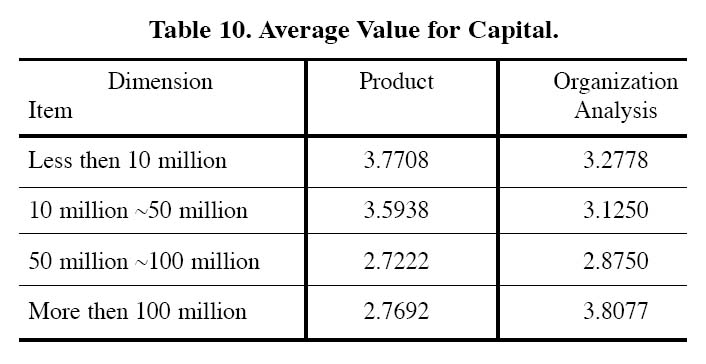

- Capital Table 7 indicates significant correlations between Product and Organization Analysis for the dimension of Capital. The average values in Table 10 reveal that Product has the largest values for companies with less then 10 million in capital. Conversely, Organization Analysis has the largest value for companies with capital of more then 100 million. This can be explained because smaller companies generally pay more attention to product specialty and uniqueness, which do not add much cost to their operations in the market of e-business. On the other hand, larger companies emphasize their employee’s adaptation to new environment.

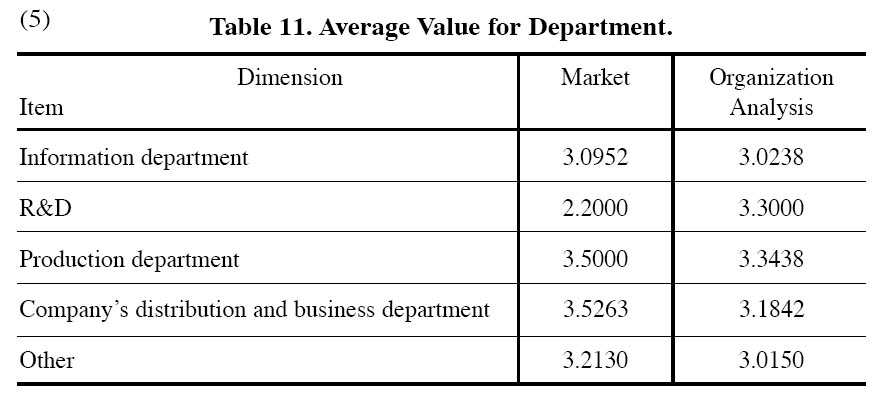

- Department Table 7 indicates a significant correlation between Market and Organization Analysis with respect to Department. Table 11 shows that the largest average values for Market and Organization Analysis can be found in the Company’s distribution and business department and Production department, respectively. This is because a company’s distribution and business departments are more concerned with market change due to its direct effect on the departments. On the other hand, the production department is more concerned with loyalty and whether involving e-business might disturb the production line.

- Table 11. Average Value for Department. (See Below for Image)

- Business Location In the dimension of Business Location, Table 7 indicates the significant correlations between Market, Inventory, and Information System. They all have the largest average values for Multinational Corporations. This can be explained because under e-business trading, multi-national corporations are keen to market expansion, product circulation, and inventory reduction in order to boast their competitiveness.

- Customer Table 7 indicates a significant correlation between Delivery and Information System for the dimension of Customer. Furthermore, Table 13 shows that Delivery has the largest average value for domestic companies, whereas the largest average value for Information System lies in Foreign company subsidiaries. This suggests that domestic companies focus more on improving their abilities in merchandise distribution, while foreign companies tend to emphasize the fineness of their information systems.

Table 8. Average Value for Different Industries

Display large image of Table 8

Table 9. Average Value for Number of Employees.

Display large image of Table 9

Table 10. Average Value for Capital.

Display large image of Table 10

Table 11. Average Value for Department.

Display large image of Table 11

Table 12. Average Value for Business Location.

Display large image of Table 12

Table 13. Average Value for Customer.

Conclusion

14 In conclusion, the e-business model in Taiwan is dominated by logistic, information system and organization behavior structure. Industries believe that logistics is the most important factor towards successful e-business trading. This is because no virtual business can sustain itself without support from an effective and efficient logistic system. Our studies indicate that companies in the logistic industry need to develop fine information systems and encourage employee involvement in the construction of e-business trading. Support from high-level management is also important for successful implementation of e-market trading.

15 We found that among the various logistic industries, air carrier companies are the most sensitive to providing buyer service for information access to reduce cost and time in inventory (storage). Larger companies are more willing to lower their costs to provide more information to the buyers. As a result, they can achieve higher customer satisfaction. They also have better management in market change and inventory fluctuation. Conversely, smaller and medium companies usually focus on the fineness of their information systems and the training of their employees to achieve employee loyalty. Companies with smaller capital generally pay more attention to product specialty and uniqueness, without adding too much cost to their e-business operations. On the other hand, companies with larger capital emphasize their employees’ adaptation to new environments.

16 From an internal point of view, departments dealing with distribution and business are more concerned with market change due to their direct effects on the departments. Departments dealing with production are more concerned with loyalty and whether involving e-business trading might disturb the production line. Under e-business trading, multi-national corporations are keener to market expansion, product circulation, and inventory reduction to boast their competitiveness. Domestic companies focus more on improving their abilities in merchandise distribution. Foreign companies tend to emphasize the fineness of their information systems.

References

Bakos, Y. and Yannis, A. (1991). Strategic Analysis of Electronic Marketplaces. MIS Quarterly. 15 (3): 295-310.

Ballou, R. H. (1992). Business Logistics Management. Prentice-Hall: New Jersey.

Benjamin, R. and Wigand, R. (1995). Electronic Markets and Virtual Chains on the Information Superhighway. Sloan Management Review. 36 (2): 62-72.

Cooke, J. A. (1997). Ground Zero. Logistics Management. 27 (4): 61-63.

Copacino, W. C. (2001). 3PLs Narrow the Gap. Logistics Management and Distribution Report. 4 (3): 1-36.

Coyle, J. J. (1996). The Management of Business Logistics, 6th Ed. West Publishing: Minnesota.

Davenport, T. H., Sirkka, L. J. and Beers, M. C. Improving Knowledge Work Processes. Sloan Management Review. 37: 53-65.

Frazelle, E. (2002). World-class Warehousing and Material Handling. McGraw-Hill: New York.

Goldman, S. (1999). B2B : 2B or Not 2B? Goldman Sachs Investment Research. 1-83.

Gopal, C. and Cypress, H. (1993). Integrated Distribution Management: Competing on Customer Service, Time, and Cost. Irwin: Illinois.

Grover, V. and Goslar, M. D. (1993). The Initiation, Adoption and Implementation of Telecommunications Technologies in U.S. Organizations. Journal of Management Information Systems, 10 (1): 141-163.

Hartenstein, A. (1988). Building Integrated HRM Systems. Training and Development Journal. 42 (5): 90.

Hodgetts R. M., Luthans, F. and Slocum, W. J. (1999). Refining Roles and Boundaries, Linking Competencies and Resources. Organizational Dynamics. 28 (2): 7-21.

Johnson, J. and Wood, D. (1996). Contemporary Logistics, 6th Ed. Prentice-Hall: New Jersey.

Kalakota, D. R. and Robinson, M. (2002). e-Business 2.0: Roadmap for Success. Pearson Education: New Jersey.

Kalakota, R. and Whinston, A. B. (1996). Frontiers of Electronic Commerce. Addison-Wesley: New York.

Kumar, K. and Van Diessel, H. G. (1996). Sustainable Collaboration: Managing Conflict and Cooperation in Inter-organizational Systems. MIS Quarterly. 22 (2): 279-300.

Matthyssens, P. and Van den Bulte C. (1994). Getting Closer and Nicer: Partnerships in the Supply Chain. Long Range Planning. 27 (1): 72-83.

McFarland, M. (1994). Governance of the National Information Infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 3rd National Conference of Computer Ethics. Washington, D. C.

Mintzberg, H. (1979). The Structuring of Organizations: A Synthesis of the Research. Prentice-Hall: New Jersey.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometrics Methods. McGraw-Hill: New York.

O’Brien, J. A. (2002). Management Information Systems: Managing information Technology in Thee-business Enterprise, 5th Ed. McGraw-Hill: New York.

Peters, T. and Waterman, R. (1982). In Search of Excellence. Harper and Row: New York.

Poole, K. J. and Durieux, P. (1999). Content Management: The Critical Success Factor for e-Procurement. Ernst & Young LLP: San Francisco.

Prahalad, C. K. and Hamel, G. (1993). The Core Competence of the Corporation. Research-Technology Management. 136 (6): 40-47.

Ratliff, H. D. and Nulty, W. G. (1996). Logistics Composite Modeling. The Logistics Institute at Georgia Institute of Technology.

Shapiro, R. D. and Heskette, J. L. (1985). Logistics Strategy Case and Concept. West Publishing: Minnesota.

Sharpe M. (1997). Outsourcing, Organizational Competitiveness and Work. Journal of Labor Research. 18 (4): 535-549.

Simchi-Levi, D., Kaminsky, P. and Simchi-Levi, E. (2001). Designing and Managing the Supply Chain: Concepts, Strategies and Case Studies. McGraw-Hill: New York.

Stank, T. P. and Daugherty, P. J. (1997). The Impact of Operating Environment on the Formation of Cooperative Logistics Relationships. Transportation Research Part E-Logistics and Transportation Review. 133 (1): 53-65.

Weber, A. C., Current, R. J. and Anand, D. (2000). A Structured Approach to Vendor Selection and Negotiation. Journal of Business Logistics. 21 (1): 135-167.

Williamson, O. E. (1991). Comparative Economic Organization: An Analysis of Discrete Structural Alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly. 36 (2): 269-296.

Wright, P. M. and McMahan, G. C. (1992). Alternative Theoretical Perspectives for Strategic Human Resource Management. Journal of Management. 18 (2): 295-320.