Volume 2 Number 1 June 1999

Six leading hotels were selected in the study of the hotel sector in an attempt to isolate the best management practices common to the sector. Two of the best practices are related to the customer in terms of creating value, while the other three are located within the people and processes of the hotel, which contribute towards operational efficiencies. Their attempt to provide engaging guest experiences as opposed to merely providing a host of amenities is particularly strategic in terms of the movement away from the limited sun and sand tourism to high-value niche marketing that has been prescribed.

Introduction

Statistics relating to global tourism indicate that over 600 million people travelled in 1997, creating over $2 trillion US of business and accounting for 11.3% of world consumption and 10.7% of world gross domestic product. The annual rate of growth of global travel has been around 4 per cent. This is predicted to remain at that level, at the least (World Tourism Statistics, 1997). Indeed, the Rs. 5.1 billion invested in small and large-scale projects in the tourism industry over the period 1995-1998 and the estimated Rs. 7 billion which will be spent on expanding occupancy of the existing hotels and setting up new hotels by year 2000 ought to be strategically directed towards gaining a competitive advantage for Sri Lankas tourism products.

J.E. Austin Associates in their study of Sri Lankas competitiveness, 1998 recognises four key factors of, what they term, sun and sand Tourism. They are US $ 58/day per tourist in Sri Lanka, dependence on charter operators, struggles to manage image, easily replaceable strategy, and OECD tastes evolving beyond sun and sand Tourism. The reports key recommendation for Sri Lanka is to move from undifferentiated Sun and Sand Tourism to tourism dedicated to identified and higher-value niches. Sri Lanka, in this context has to develop an understanding of customer requirements on a niche-specific basis, develop an image and implement improvements to ensure that customer expectations are met. The growing potential of tourism and the need to develop a strategic position for Sri Lankas tourism product is of direct relevance to an investigation of the best management practices in this sector. The objective of this paper is to report research findings of such practices in the hotel sector of Sri Lanka.

Sector overview

The number of hotel units in the graded accommodation sector increased from 144 to 158 in the year 1997, mainly in the South Coast and in the ancient cities. With the increased number of hotel units, room capacity now stands at 47,880 persons (Central Bank Annual Report, 1997).

Western Europe continues to be the leading source of tourist traffic to the country, accounting for 58 percent of total arrivals. The UK, has become the main single source of arrivals, outnumbering Germany in 1996. Arrivals from Asia, the second largest source, grew by 10 percent. Table I presents basic data pertaining to the tourism sector in Sri Lanka for the period 1995-1997.

Central Bank in its report of 1997 states that, as in the past, vacation was the main purpose of arrivals, accounting for about 95 per cent of total arrivals. The remainder was for purposes, such as business or visiting friends and relatives. Reflecting the potential for the promotion of noble aspects of pleasure tourism such as eco-tourism and culture tourism, the revenue from foreign visitors who visited wild life parks, botanical gardens, zoological gardens and the cultural triangle continued to increase in 1997. The need to recognise the noble aspects of pleasure tourism has to be seen in the context of the phenomenal size and growth of the tourism industry on a global scale and Sri Lankas strategic position in the overall market. It is against this backdrop that one has to view the best management practices of the hotel sector.

Table 1: Tourism Sector 1995 - 1997

Study Framework

The scope of the study of the tourism sector is limited to hotels. The following table indicates the sample composition and key performance data with respect to the hotels studied.

Table 2: Performance Indicators of Selected Hotels, 1997

(Rs.000s}

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aitken Spence Hotel Holding Ltd. | RS. 761,799 | RS. 634,501 | 103.03 | 1.57 | 66.07 |

| Palm Garden Hotels Ltd. | RS. 91,800 | RS. 85,220 | 3.00 | 5.20 | 7.29 |

| Hotel Eden | RS. 300,000 | RS. 196,745 | 64.39 | - | - |

| Taj Lanka | RS 170,975 | RS. 299,835 | 64.54 | - | - |

The CEO of each hotel was first interviewed which helped to identity key areas of best management practices. A study group thereafter probed focal areas of best practice and gathered in-depth, qualitative information about those areas. The five best management practices that have been recognised are those of the sector in general, rather than individual hotels, in particular. The best practices are stated and described, on a tentative basis and their validation would depend on further study of a larger sample.

Best Management Practices

The study of the sample of hotels pointed to five key management practices that appeared to have either created value to external customers or helped improve operational and process efficiencies within the organisations. They are listed below.

(a) Stage Guest Experiences

The hotel business is typically placed within the hospitality industry. According to Oxford Dictionary, hospitality stands for a friendly and liberal reception of guests or strangers. Indeed, the chief endeavour of the hotels was to be friendly and helpful in terms of service, offer desirable food and beverage as tangible products, and clean rooms and spacious corridors for comfort. The concept of a hotel was one of temporary abode; a place to rest after ones visits to the beach, places of scenic beauty or cultural significance. The hotel itself was not conceived to be a place for an engaging experience as opposed to the mere amenities provided by the hotel.

The CEOs of the hotels studied in the survey defined their business in seemingly unorthodox fashion. To the classical question, What business are you in?, the response was not, ..of course the hospitality industry. Interestingly, the business domain of the hotels appeared to be a fusion, an amalgam between the hospitality industry and show business. The following illustrates this.

“Hotel business is decidedly show business. Making the guest feel good and look good is very much a part of our endeavour”. (Gamini Fernando, Colombo Hilton)

“Kandalama is a place to experience nature; of that which is rustic, tranquil and mountainous”. (Prema Cooray, Aitken Spence Hotels)

“Animation is our main stay, it is our primary offer to our guests. Guests are engaged in a multitude of sports activities during the day, and in the evenings, the guests become actors and actresses in their show. They dance, sing, mimic and mime. The animators are trained to get the guests out of their shell and drop their inhibitions. The guests, typically stay in the hotel for around 10 days. (Palitha Wijemanna, Club Palm Garden Hotel)

“The Tea Factory is literally a hotel in a tea factory. It provides a unique experience. The bedrooms have been carved out of the four large lofts that were used for the withering process, which is the first stage of black tea manufacture after the green leaf from the field is delivered at the factory”. (Prema Cooray, Aitken Spence Hotels)

“We have many tourists getting married in traditional Sri Lankan style. Sometimes, for a month, we have about 20 - 25 weddings”. (Palitha Wijemanne, Club Palm Garden Hotel)

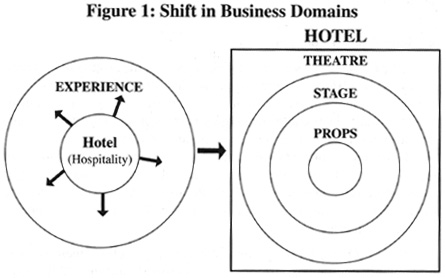

The shift in focus from hospitality per se to a hospitality-show business synthesis is conceptualised below.

The hotel stages a definable experience. The “theatre” is its settling, ambience and the larger structure. The “stage” is set by the provision of particular activities/services. The “props” are the tangible products that are offered to the guests and are placed around them. Hence staging guest experiences begins with a clear definition of the kind of experience offered (i.e., a “theme” in the hotels nomenclature). Then the setting, service and products are orchestrated to “create the illusion” to provide an engaging experience for the guests.

Hilton offers the experience of, “an oasis in the city”, with its plush environs, cosy ambience, efficient service and superlative food and beverage. Kandalama is located in the mountains with parts of the natural habitat in the corridors of the hotel. The swimming pools are rocky. They are filled up with water from the tube well with less chlorine and chemicals and more water, creating the illusion and experience of going for a swim in the natural wilderness. This theatre, indeed setting is accentuated by the activities/services extended by the hotel. Herbal therapy and treatment provided in-house to the guests strengthens the nexus of Kandalama-Lankan heritage. Props, indeed products add to the total experience. Traditional Lankan buffets (dinner and lunch) are served at the top of the rock by traditionally dressed men and women (hotel staff) in accordance with village customs. Food is served on banana leaf and no western cutlery and crockery is used. Special theme nights are organised and hosted in the surrounding jungle area, belonging to the hotel. Settings are created to approximate the ancient Sinhala Kingdom where hotel employees act as horseback soldiers and Royal servants; the hotel guests being ushered in as the royal guests. The whole area is fire lit with all the elements of an ancient Lankan royal feast in place. Indeed, all this sounds more like “show business” than typical hospitality.

Kandapola Tea Factory provides another vivid example of hotels staging engaging guest experiences as opposed to providing comfortable rooms and good food. There is a miniature tea factory within the hotel, where guests could pick up tea leaves from the surrounding estate and then give them for processing in the miniature factory, in the end enjoying a cup of tea made from those very leaves. Moreover, visits to the surrounding plantation enable the guests to interact with plantation workers, nature walk and take a bath in the natural springs of the cool hill country. Here again, we see how the larger setting, a host of activities (services) and props (products) help create an experience that has been clearly defined.

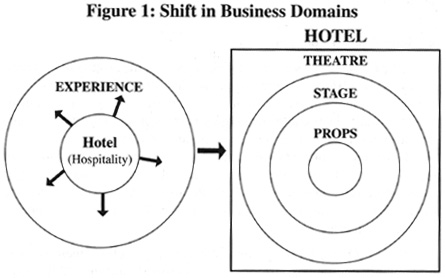

The “engaging experiences” provided by the hotels studied can be classified, using Pine and Gilmores conceptualisation of the realms of experience (1998), in the following way.

Quadrant 1 relates to “Entertainment”. Attending shows of traditional costumes (viz. sari/sarong shows) is a case in point, where guests participate more passively than actively and their connection with the event is more likely to be of distant absorption rather than immediate immersion. “Educational” events such as taking ski lessons and “rafting” offered by Taj Exotica, for instance, tend to involve more active participation, but guests are still more “outside the event” (i.e. absorption) rather than immersed in it (i.e. Quadrant 2). “Escapist” experiences amuse just as well as entertain, but they involve greater customer immersion. Club Palm Gardens animation programmes is a case in point (i.e. Quadrant 3). In quadrant 4, the “Esthetic”, guests are immersed in an activity or environment, but they themselves have little or no effect on it.

Pine and Gilmore (1998) posit that richest - experiences such as going to Disney World or gambling in a Las Vegas Casino - encompass aspects of all four realms, forming a “sweet spot”, around the area where the spectra meet.

Key Learning Outcomes

The first of the best management practices of the hotels studied is staging engaging guest experiences. It has important implications for the hotel sector, in particular and the service sector, in general. Indeed, there are lessons to be learnt for any service provider who finds himself interacting with customers in a particular setting, often that of the service provider himself. For example, it is necessary to clearly define the experiences to be created, and to orchestrate the (I) setting/structure (vis “theatre”) (ii) services/activities (viz “stage”) and (iii) props (viz, “products”/things) to create the defined experiences. The compatibility and congruity of the three elements will have a synergistic effect on the customers experience, while a miss-match among the three elements would weaken the experience. Importantly, the definition of the “experience” is a strategic issue that the top management has to address. The concepts of unique selling positioning (USP) and competitive advantage (CA) are germane in the selection of the genre of experiences that the organisation would choose to offer its target customers.

More importantly, the principal lesson to service marketers is the importance of symbolism. The symbolic significance of physical evidence provided by the service marketer is to be recognised here. As Levitt (1977) argued, “...a hotel wrapping its drinking glasses in fresh bags or films, placing on the toilet seat a sanitised paper band, and neatly shaping the end pieces of the toilet tissues into a fresh-looking arrow head, make the claim, the room has been specially cleaned for your use and comfort, evident and experiential to the guests”. The service marketer must use the setting, activities and physical evidence such as props or products to create an engaging experience for the customer.

Insofar as the hotel sector is concerned, the strategic shift from “sun and sand” tourism to higher-value niches, such as “echo-tourism” and “culture tourism” discussed earlier should be viewed in the context of the significance of engaging guests in memorable experiences. Indeed, it appears that some hotels are entering the experience economy, a veritable cross between “hospitality” and “show business” and targeting their offerings to high-value niches.

(b) High-touch Guest Relations

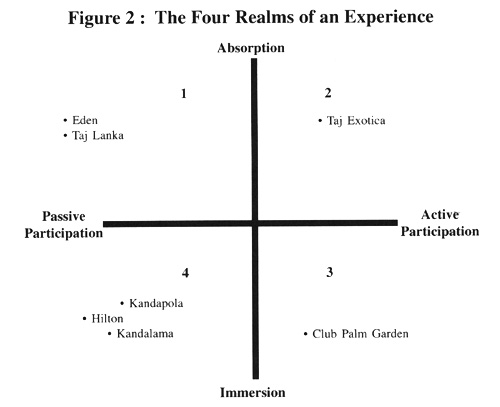

The hotel sector perhaps best demonstrates customer intimacy, given the nature and structure of the customer-organisation interface.

Typically, the manufacturer or the trader interfaces with the end user. In many service organisations, the company-customer contact is limited to a few minutes. However, in the hotel industry, the customer literally lives in the organisation. He eats, sleeps and, as we observed, “experiences” within the organisation. The moods, needs, and expectations of the customer may change, sometimes dramatically during the day. The hotels, therefore, have to be in close touch with the guest, on a continual basis in order that the customer remains content and satisfied.

The hotels studied in the survey identify critical points of contact between something or somebody of the organisation and the guest (i.e. “moments of truth”) and attempted to manage these contacts in an organised fashion. This is particularly true for special, VIP guests. Identified below are some MOTs and their management by the hotel with respect to an important guest.

One-time contact with the guest is another feature that was observed (e.g. Eden Hotel). Any employee, regardless of his/her position in the hierarchy, is accountable for the interface with a guest. A guests request, say for an extra towel, will be met by the person contacted by the guest. This again is suggestive of the “high-touch” approach to interfacing with guests.

Table 3: Managing Moments of Truth

| Moment of Truth | Hotel's Response |

| Arrival at the Airport | A hotel's car is sent to the Airport. The chauffeur finds out in advance through Airport personnel who the guest is and calls him/her by name when greeting. No name board is held up for identification. |

| Arrival at the Hotel | Front of the office staff are alerted by the security personnel upon arrival of the guests. They walk up, garland and greet the guest, addressing the person by his/her name. |

| Checks in | Basic information is filled in by the staff. The guest fills only that which is absolutely necessary. A welcome drink is offered, while the guest attends to registration. In some instances, registration is done not at the reception but at the executive floor for the convenience of the guest. |

| Moves to the room | A member of the staff accompanies the guest to the room. |

| Enters the room | A bouquet of flowers and a basket of fruits are placed for the guest with his/her name written on a personalised welcome card. |

| Guest telephones front office | The name of the guest is displayed on the telephone's display unit and the front of the office staff respond "yes Mr..............., what can I do for you?" (Colombo Hilton) |

| First day in the Hotel | A cocktail party is organised to formally welcome the guests who have checked in during the previous 48 hours. The guest Relations Officer (GRO) plays an active role in establishing contact and rapport. (Eden/Club Palm Garden Hotels) |

| Remainder of the stay | a) GRO and others key staff members meet with guests informally and

ascertain satisfaction levels. Particular preferences are noted (E.g. choice

of a Newspaper) and the guest is pleasantly surprised (delighted) when

he/she receives it.

b) If a birthday or anniversary falls during the stay of a guest, a cake and a card is sent to the room. c) Formal questionnaires are made available to the guests to express their satisfaction levels and a self addressed envelop is placed in the room of the guest in the event any complaint/suggestion is to be made directly to the General Manager. |

| Post-departure | For newly married couples, for instance on the day of their anniversary, a card is sent along with a discount coupon inducing the guest to return. The important dates are stored in an in-house guest database. |

Key Learning Outcomes

The service industry can identify critical points of contact between theircustomers and the organisation and learn to manage them in a deliberate fashion. Gestures to demonstrate customer intimacy are a point of learning for the service industry at large.

(c) Hands-on Staff Management

“In the hotel business, the top management cant stay in their rooms. They have to move and walk around”. (Gamini Fernando, Colombo Hilton)

Management by walking around (MBWA) is a key feature that was evident in all the hotels surveyed. The General Manager himself is very often seen in the restaurant and the lobby areas, talking to the staff. A system of interactive controls is very much in place.

“I will go to a restaurant and signal to the manager in charge or the staff member that a guests glass is empty and that the time is opportune to fill it up”. (Gamini Fernando, Colombo Hilton)

Managers in various departments undertake complete “house rounds” on a roster basis with heads of departments (e.g., Eden & Colombo Hilton). Formats are designed to carry out audits by managers. A cross-functional bias towards ensuring cleanliness, orderliness and conformance to standards was witnessed.

The Training Department, in particular, would, on a periodic basis, telephone various service units playing the role of an external caller and make enquiries about the hotels offerings. Staff responses are noted and information is fed back to the respective staff members(s). On some occasions, with the “connivance” of the front of the house management staff, the training departments members will check in to a room and ascertain response time, quality of food and service, and performance vis-a-vis other particular service attributes.

Key Learning Outcomes

What are the lessons for the hotel industry, in particular and other service organisations, in general? Tom Peters (1988) extolled the virtues of management by walking around (MBWA) which he called the “technology of the obvious”. Getting the boss back to work watching his customer, employee and product, Peters observed, is a key success factor. This was markedly evidenced in the study.

The involvement of the senior management of one department walking about in other departments to ensure that nothing is amiss is a striking feature of MBWA that was witnessed. Mystery Customer Research is another learning point. This is a method that can be employed in a variety of product/market settings and industries.

(d) A Passion for Exactitude

Levitt (1977) observed that “inseparability” and “variability” are intrinsic characteristics of services, which distinguish them from tangible products. The inseparability of the service provider from the service itself is to be noted. This points to the centrality of the human element in services, which is accompanied by variability or lack of uniformity and standardisation in the provision of services. Levitt remarked that “soft technologies” through the division of labour, accompanied by a clear delineation of task performance, would help to deal with variability. The practice of deliberately managing each task, including that, which is seemingly trivial, is evident. There is a manifest passion for exactitude, a need for definition and an attempt at standardisation.

Hotels “induct with impact”. Orientation programmes are well defined and designed. At Aitken Spence Hotels, for instance, a programme titled “roots of excellence” conducted by the Human Resource Department is thorough and comprehensive in as much as Colombo Hiltons induction programmes. At the Hilton, the two day orientation programme helps instil in the new recruits the “Hilton ethos”.

Table 4: Colombo Hilton Front Office - Task Analysis

Activity: Check in a customer with advanced registration

| WHAT (Steps) | HOW (Key Points) | WHY (Reasons) |

| After the customer has finished filling the registration, obtain the card back. | By saying to the customer politely: "Thank you, Mr. Singh". | |

| Verify the registration details. | By checking carefully the registration card of the customer from top

to bottom, to ensure the information is complete and legible.

Check if the following details have been filled in by the customer. - Name & Company Name - Address & Passport Details - Next Destination & Payment Details - Signature |

Because you need them to identify the guest and to know how he is going to settle his bill. |

| If any of the details are missing, ask the customer for the information. | By saying to the customer: "May I just have your next destination please Mr. Singh..." and complete the missing details yourself. | So we obtain all necessary information. |

| The only other detail the customer must fill in is his signature | It is a legal requirement to ensure we have a specimen signature to use as reference or proof of consumption in case of query or default. | |

| Verify the name of the customer. | Check the spelling of the customer's name immediately and correct any mistakes. | To ensure we use their name correctly and they receive their calls immediately. |

The message that each employee is a Mr/Ms. Hilton insofar as the guest is concerned is repeatedly conveyed and reinforced. A special attempt is made to make each employee “walk tall, talk tall and smile easily”. The mandatory requirement of English knowledge is linked to this confidence-building endeavour. At the end of the two-day orientation programme, “skills training” is provided in particular areas of the business. No employee is allowed to be exposed to a guest until the Training Department is convinced that the employee is competent.

Key Learning Outcomes

The service Industry could learn from the attempt to tighten a select number of activities that may benefit from standardisation. However, some activities may be best left for ad-libbing. In this context, the loose-tight properties of Peters and Waterman - one of the eight attributes of excellent companies - is of significance.

(e) Track at the Centres

The “profit centre” concept is well established in the hotels examined in the study. Performance at each profit centre is tracked regularly, in most instances, on a daily basis. Key managers have ready access to information.

“I place great emphasis on numbers. All vital information is eventually reducible to numbers”. (Prof. Furkhan, Confifi Group Hotels)At Eden Hotel, for example, there are a dozen profit centres - rooms, main restaurant - garden of Eden, coffee shop - top deck, main bar - captains deck, night club-Chameleon, pool bar-splash, mini bars, room service, shop rentals, commission on encashment, guest laundry, and guest telephone. Performance of most of these profit centres is measured daily, and of others weekly.“Company operates on the basis of profit centres. We carefully track performance in each of the revenue earning outlets of the hotel”. (Prema Cooray, Aitken Spence Hotels)

“First thing, each day, we figure out performance data against targets of each revenue generating outlet”. (Gamini Fernando, Colombo Hilton)

Occupancy figures are made available to top management on a daily basis and monthly performance data are relayed through flash reports by the second day of the following month (viz. Aitken Spence Hotels). Clearly, a bias for measurement of performance is evident.

Key Learning Outcomes

In some organisations, a preference for aggregate accounting prevents one from observing the performance of individual business units. The lesson to be learnt here is to disaggregate business units, on the basis of their profit generating capacity and then with predetermined regularity, measure performance of each business unit vis-a-vis standards.

Balanced Scorecard Analysis

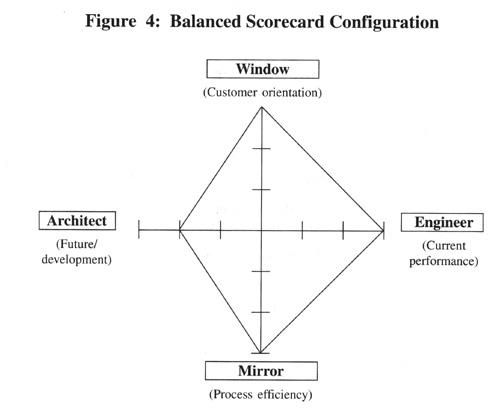

Each of the best management practices that has been identified is now analysed in terms of the balanced scorecard, whose factors are as follows:

Table 5: Balanced Scorecard of Best Management Practices

| Best Management Practice | Customer Value | Process Efficiency | Current Performance | Future Development |

| Stage guest Experiences | High | High | High | High |

| High-touch Relations | High | Medium | High | Medium |

| Hands-on staff Management | High | High | High | Medium |

| A passion for Exactitude | High | High | High | Medium |

| Track at the Centres | Medium | High | High | Medium |

Staging engaging experiences takes the hotels offering closer to customers. The “total experience” that is “sold” to the guests is priced competitively by international standards. Hence the practices adds high customer value. The practice also reflects high internal process efficiency. In the design of the setting/structures and conduct of a multitude of activities/services that, together produce the “guest experience”, one observes group work and strong inter-personal relations. The need to set up cross-functional teams is evident.

A number of organisational processes are designed efficiently to make the “experience” a reality. The management practice of staging engaging experiences contributes highly toward internal current performance in terms of productivity/benefits over costs/profitability. The animation programmes, the cultural shows, setting up appropriate props, are all illustrative of relatively low-cost activities, adding value to guests. Importantly, the practice of staging experiences has a developmental bias and strategic implications. As was discussed, it seems strategic to move away from “sun and sand” tourism to high-value niche marketing. The practice of staging experiences facilitates this vital shift.

As regards high-touch guest relations, the (customer) value addition is evident. The guest is able to communicate with the staff of the hotel, express his/her concerns and requirements directly. The practice, however, does not appear to contribute directly towards employee productivity, group work and interpersonal relations. The practice of high-touch guest relations enables staff members to interface cross-functionally to meet guest requirements. The contribution of the practice to current performance is clearly high. In terms of a strategic focus, other than the hotels attempt to continue to communicate with guests, in the medium term, the practice does not markedly contribute towards implementing a developmental strategy.

Hands-on staff management and the constant supervision of the staff in real-time were provided for better customer service and, therefore value to customers. The practice clearly contributes significantly towards work process efficiency and productivity. Importantly, the practice of MBWA does not appear to be likened to “policing” by the staff. It is considered to be an integral part of hotel management. The impact on current performance is high. Interactive controls are exercised as a consequence of being in continual touch with the staff. As regards development, the impact is not high. Hands-on staff management does not appear to be directly contributing towards staff development.

A passion for exactitude, it is argued, adds high value to guests. The practice appears to reduce the margin of error and default by the staff. It thus helps the process of standardisation

A sandwich of a particular type will taste the same, whenever it is ordered. This practice helps fashion customer expectations and manage product/service performance effectively. The practice clearly improves operational efficiency and provides standards for control purposes, thus impacting on internal performance improvements. The impact on future development does not seem significant.

The “Profit Centre” concept and its widespread adoption help analyse performances that fall short of the standards. Identification of causal factors for poor performance often leads to improvement of products and services, which in turn add customer value. This process, however, is not direct and immediate. Decision-making is facilitated and work processes within the profit centre are better organised and conducted as a result of “tracking at the centre”. The contribution of the practice to internal performance improvement is direct and high. It enhances performance measurability markedly. The impact of the practice on the future does not appear to be high. The measurements form the basis of controlling current performance rather than discern trends for the development of future strategies. This appears to be the scope of the practice.

All in all, considering the five best practices together and placing the hotels surveyed in the balanced score card, produces the following configuration.

The relatively low score for the practices relationship with the future and development in terms of capacity enhancement and development of a strategic focus is perhaps an outcome of the uncertainty that prevails in the macro-environment. The security situation and static tourist arrivals have, in fact, prompted many hoteliers to consider diversification away from their core business. However, given the phenomenal size of the tourism market and impressive growth patterns in the global scene, one may argue that a futuristic and strategic approach to the management of the industry is not only necessary but imperative.

Conclusion

The six hotels that were examined appear to be having a number of practices that generate customer value and improve operational efficiencies. The internal operations and external, hotel-customer interface appears to be well balanced. The significant size and clear growth patterns of the global tourist market suggest that if Sri Lankas tourist product is sufficiently differentiated from that of the region, then the sector would be poised to grow at a rate that will make a significant impact on the countrys economy. The best management practices that were recognised in the study will stand in good stead in propelling the sector in its forward movement.

References

Peters, T. and Austin, N. (1988). A passion for excellence, Random House, New York.

Levitt, T. (1977). Marketing tangible products and product intangibles, Harvard Business Review.

Pine, J. and Gilmore, J.H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy, Harvard Business Review. July August.

J.E. Austin Associates, INC. (1998). Sri Lanka's competitiveness study, Colombo.

Central Bank of Sri Lank (1997). Annual report, 1997, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Colombo.

Colombo Stock Exchange (1997). Handbook of listed companies, Colombo Stock Exchange, Colombo.