Volume 3, No. I June 2000

by

Salma Mohammed Al-Lamki

Sultan Qaboos University, Al Khod, Oman

This paper addresses the issue of Human Resource Management (HRM) and training with particular emphasis on Omanization (the replacement of expatriate with Omanies) in the Sultanate of Oman. First, the paper discussess an overview of the human resource management practices in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and the emerging economies of East Asia. This is followed by the specifics of the Sultanate of Oman's experience outlining the national policies on human resource management & training and government supported Omanization schemes and incentives. Finally, the author recommends an integrated and holistic three tier strategic framework for human resource management and training in the Sultanate of Oman.

Introduction

A sustainable economic advantage stems from a country's resources- human, financial and natural resources. The key strategic means of gaining competitive advantage include natural resources, financial-cutting overhead and costs, innovation and technological capabilities. Undoubtedly, these dynamic means have always been successful in developing a "niche or competitive-edge". Nonetheless, until recently, the nation's ability to manage human resources to gain a competitive advantage has been undermined (Barney, 1991; Porter, 1990). While human resource management and training has been instrumental in the economic competitiveness and success of developed countries, its role in developing countries has/is being overlooked. Many businesses have treated human resource as a commodity and individuals as dispensable. Shortsighted managers seeking quick profits fail to realize that the only enduring competitive advantage is a well trained, competent and highly motivated human resource willing to work as a team to accomplish organizational objectives efficiently. Hence, the era of merely neglecting workers is ending as more companies come to grips with the fact that productivity, innovation, technology and growth depends on a skilled, competent and motivated workforce (Aryee, 1994; Barney, 1991). These attributes which constitute human resource assets integral to competitive advantage are not inherited but are, instead, developed and nurtured within the nation.

The thesis of this paper promotes the conviction that economic success is achieved through an educated, trained and skilled human resource. Studies of excellent organizations in terms of performance suggest that one thing they have in common is high regard for and continuing attention to their human resource (DeCenzo & Robbins, 1994; O'Reilly, 1992; Dreyfus, 1990; Schneder, 1987).

This paper addresses the issue of Human Resource Management (HRM) and training with particular emphasis on Omanization (replacement of foreign 'expatriate' workers with Omani nationals) in the Sultanate of Oman. The current composition of the labour force in the Sultanate's private sector is predominantly (92%) foreign 'expatriate' workers. Researchers attribute this predicament to several factors including a lack of strategic human resource management planning and coordination between the government and the private sector (Al-Lamki, 1998; Al-Maskery, 1992; Eickleman, 1991; Birks and Sinclair, 1980). This paper aims to address this predicament by recommending an integrated and holistic three tier strategic framework for human resource management and training in the Sultanate of Oman.

An Overview

A fundamental pre-requisite to economic development and growth is the availability of skilled and competent labour. In a period of increasing economic integration and globalization labour mobility has been an integral phenomenon (Stalker, 1994). Whereas labour flows into most OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development) countries peaked earlier in the century, with migration to Europe and the U.S.A., the emerging economies of East Asia and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have been affected by increasing international labour mobility during the past thirty years (Ahuja, 1997; Ruppert, 1998; Stalker, 1994).

Among the emerging Southeast Asian economies, Singapore and Malaysia have experienced robust and sustained economic growth with considerable reliance on foreign labour (Ruppert, 1998; Wong, 1997; Aryee, 1994). Although Singapore and Malaysia have a relatively smaller ratio of foreign employment compared to the GCC countries, they nevertheless play host to large numbers of expatriates in their workforce. Foreign workers 'expatriates' make up approximately 20 to 25 percent of Singapore and Malaysia's labour force, respectively (Wong, 1997). Similar to the GCC countries, the growing presence of foreign workers in Singapore and Malaysia can be explained by excess demand for labour associated with rapid economic growth, as well as the relatively cheaper cost of foreign labour. This is attributable to the willingness of foreigners to accept lower wages and generally tolerate poorer working conditions and physically demanding jobs (Ruppert, 1998; Wong, 1997; Aryee, 1994).

Singapore and Malaysia manage their large expatriate population through a complex and tightly regulated immigration policy in the form of work permits and variable levy (fees). In order to curb the influx of foreign labour and encourage the employment of nationals, the system of variable permits and fees effectively raises the cost of foreign labour. This is particularly the case for the unskilled and less skilled labour. Higher levies apply to these categories as a measure towards discouraging over-dependency on cheap, unskilled foreign labour (Ruppert 1998, Ayree, 1994). On the other hand, these dynamic nations addressed the issue of indigenization of the workforce through robust and well planned human resource development programmes. This was carried in line with the economic requirements and needs for requisite skills and competency. Consequently both academics and policy makers envisaged a nexus between human resource development and educational planning, because for educational planning to be instrumental in the achievement of economic goals, it must be geared to the demand for skills required in specific industrialization programmes (Ruppert, 1998). As labour importers, these countries share similar experience with the GCC countries.

In the oil-producing Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, rapid development financed by oil revenues resulted in robust economic growth, infrastructure development and the expansion of public goods provisions. In order to support and sustain this growth in the wake of a shortage of supply of indigenous labour, foreign workers (primarily from the Indian sub-continent) were imported to fulfill this role. Over time many of the GCC countries become dependent on the cheaper and more qualified expatriate labour. In addition, expatriates generally work long hours, accept lower wages, tolerate poorer working conditions and physically demanding jobs which would not necessarily be accepted by the nationals (Al-Lamki, 1998; Eickelman, 1991; Shaeffer, 1989). The presence of foreign workers in this region has in fact outgrown the indigenous workforce, and typically represents a majority. In most of the GCC countries, over 60% of the labour force are foreign (Ruppert, 1998).

To address this disparate composition of the workforce, many of the GCC countries embarked on rigorous training and development programmes in order to promote the employment of nationals in the labour market. This was accompanied by government-mandated "gulfization" policies and mechanisms to stem the inflow of foreign workers and encourage the employment of nationals. Measures to curb the growth of foreign workers typically included mandated targets for "gulfization/nationalization" in different employment sectors (government & private), permit requirements and levy (fees) for foreign workers, and attractive incentives and preferential treatment for companies adhering to nationalization policies (Maloney, 1998; Ruppert, 1998).

The Omani Experience

The Omani experience with regards to national development and economic growth is similar to its neighboring GCC countries. The distinctiveness of the Omani experience, as presented here, lies in its history as a developing country. Oman shares with the rest of the GCC countries similar constraints with regards to the availability of an educated and experienced indigenous workforce. The sociopolitical and economic circumstances of Oman during most of the twentieth century, coupled by the lack of modern educational facilities prior to 1970, has resulted in its underdevelopment as well as an absolute shortage of indigenous educated populace (Townsend, 1977). This predicament permeates all segments of the development programmes in the country including the private sector (Peterson, 1978, 1987).

The Sultanate of Oman experienced major challenges during its process of nation building and economic development. A major stumbling block during the process was the training and development of national (Omani) human resources to enable them to take an active role in supporting and contributing towards the country's rapid development. This was a formidable task and indeed a mammoth challenge given that until 1970, there were only three elementary schools for boys, which was the only source and medium for modern education.

The misery of Oman's isolation from the rest of the world along with social suppression and economic stagnation came to an end in 1970 when His Majesty Sultan Qaboos Bin Said took the reign of power (Townsend, 1977; Peterson, 1978). On the dawn of the national renaissance in 1970, His Majesty's government embarked on a vigorous policy of social and economic development. Oil revenues, the backbone of Oman's economy, supported these policies. Hence, the Omani society witnessed a rebirth of their nation, from one that was lagging behind socially and economically to one with hope for great success and prosperity.

In the context of the initial renaissance in 1970, and under the prevailing conditions of a dearth of educated Omanies, the government policy of building a modern economy necessitated the importation of foreign manpower (primarily from the Indian sub-continent) to implement the country's ambitious development plans. Recourse to expatriate workforce was seen as an essential alternative (see Table 1) until such time when a sufficient number of Omanies is educated to assume responsibility in the development of their country, and eventually, replace the expatriates.

| Nationality | ||

| Omani | 118,720 | 18.2 |

| Expatriate (Non-Omani) | 535,134 | 81.8 |

| Total | 653,854 | 100.0 |

The Private Sector in the Sultinate of Oman

One of the fundamental objectives of the 2020 future vision of Oman's economy was to encourage, support and develop the role of the private sector as the major driving force of the national economy. To this effect, the government had taken the necessary steps to privatise a number of major economic activities in the country, whilst encouraging foreign investment, and offering investment facilities to both local and foreign investors. This privatisation policy was directed as a measure of reducing dependency (less reliance) on the oil revenue which constitute around 70% of the total national revenue (Al Markazi, 2000).

In its drive toward privatisation, the government has privided the infrastructure along with the legal and institutional framework. In this respect, the private sector is expected to assist the government in implementing the policies of economic diversification and increasing the shares of the manufacturing and service sectors in GDP (Al Markazi, 2000). This is to be accomplished by taking the initiative in setting up projects of high value added that help diversify the economy and create new job opportunities for the Omanies.

The private sector in Oman, considered a major employing sector (see Table 2), has traditionally been pursuing a pattern of human resource employment practices with a preference to utilize a cheaper and skilled expatriate (non- Omani) work force primarily from the Indian sub-continent. This is evidenced (see Table 3) by the presence of a large population of expatriate workforce comprising 91.6% of the total private sector workforce.

| Sector | ||

| Government (Public) | 106,140 | 16.2 |

| Private | 547,714 | 83.8 |

| Total | 653,854 | 100.0 |

In Oman's initial socio-economic development phase, the traditional pattern and practice of depending heavily upon foreign labour was acceptable and considered the only source of manpower due to the acute shortage of a qualified and experienced national workforce. Nonetheless, eventually, despite the availability of an educated national workforce graduated from secondary schools, technical colleges and universities, the trend in the private sector continues to favour a preference for expatriate labour.

| Nationality | ||

| Omani | 46,171 | 8.4 |

| Expatriate (Non-Omani) | 501,543 | 91.6 |

| Total | 547,714 | 100.0 |

Studies indicate that this predicament and disparity regarding the profile and composition of the private sector workforce is due to a number of reasons including a lack of coordination and planning between education (training & development) and labour market requirements (Al-Lamki, 1998; Al-Maskery, 1992; Rowe, 1992; Birks & Sinclair, 1980). The lack of skills and competency for private sector jobs has been reported as a major impediment to local "national" recruitment (Rowe, 1992). This is coupled with the propensity of Omanies to secure titular and sinecure jobs in the government sector (see Table 4) that offers the comforts of convenient working hours, generous holidays and annual leave, lifelong employment, favourable labour laws (such as generous maternity and bereavement leave; and pension fund scheme), and attractive retirement policies (Al-Lamki, 1998; Al-Maskery, 1992; Eickleman, 1991; Ernest and Young, 1990; Shaeffer, 1989).

| Sector | ||

| Private | 46,171 | 38.9 |

| Government | 72,549 | 61.1 |

| Total | 118,720 | 100.0 |

Another related factor is the varying wage scales and work conditions between the government sector and the private sector. The remuneration package in the government sector for unskilled and semi-skilled work is twice that of the private sector. Furthermore, conditions of work in the government sector such as working hours, office facilities and working environment are much more conducive than that of the private sector. Overall the absence of a comparable remuneration package and quality and conditions of work in the private sector has led to a work preference in the government sector (Al-Lamki, 1998; Al-Maskiry, 1992; Eickelman, 1991).

National Policies on Human Resource Development (Omanization)

One of the principal and most integral objectives of Oman's Vision 2020 is the development of Human Resources. The importance of Human Resource Development (HRD) has been given top priority throughout the Sultanate of Oman's successive Five-Year Development Plan. In Oman's vision 2020 economic conference held in Muscat in June, 1995, His Majesty's address to the nation clearly emphasized the need of the private sector to undertake an active role in the development of the economic process and in the achievement of the national goals. Nonetheless, this was not considered in isolation from the development of the national human resources, but rather in conjunction as proclaimed by His Majesty Sultan Qaboos Bin Said:

"Development is not a goal in itself. Rather, it exists for building man, who is its means and producer. Therefore, development must not stop at the achievement of a diversified economy. It must go beyond that and contribute to the formation of the citizen who is capable of taking part in the process of progress and comprehensive development." (Vision 2020 Conference, June, 1995)

In Oman, now as never before, the training and development of national (Omani) human resources to a high level of efficiency & competency is a must. This is due to a number of reasons including less dependence on oil resources, less dependence on foreign (expatriate) workers, Omanization, implementation of a successful privatisation programme, diversification, industrialisation, technological innovation and an increasingly competitive global market.

Government Supported Omanization Schemes and Incentives

It is clear that the strategic directives of development in the Sultanate of Oman continually stresses the significant importance of training and developing its national human resources. Since the dawn of the national renaissance in 1970, His Majesty Sultan Qaboos has repeatedly stated that Oman's most crucial resource is its national human resource. In recognition of this national objective, the government has established and empowered a number of public institutions such as the High Committee for Vocational Training, the Ministry of Social Affairs, Labour and vocational Training, the Chamber of Commerce & Industry and the recently established Omanization Follow-up Committee to oversee the Omanization process (the training and development of national cadre to gradually replace the expatriate workforce) in the country (Al-Ghorfa, 1998). This has been initiated and supported by a number of Omanization schemes and incentives as a measure towards replacing the large expatriate workforce in the country as well as to ensure a qualified and skilled cadre of Omani workforce to actively participate in the country's economic development and prosperity.

To this effect, the High Committee for Vocational Training had issued a decision in 1994 fixing Omanization percentages with time bounding (see Table 5) for different employment sectors in the country. The main objective of this committee which was established in 1991 is to promote the training and development of Omani nationals to enable them to replace the expatriates in the different private sector establishments. This initiative was supported by a number of Omanization schemes and incentives that took effect in 1991. These incentives included a compensation sheme for private sector firms in lieu of the salaries and allowances payable to Omanies during their period of training. Another related incentive measure is the labour levy rebate scheme. This scheme stipulates that private sector organisations having 20 or more employees are required to participate in the training and development of their Omani employees. The employers are compensated for the expenses incurred in training Omanies against the labour levy provided in the training scheme that meets the ministry's training requirements. The rebate scheme is a percentage of the aggregate compensation of foreign (expatriate) employees. The percenatage varies from 2% to 6% according to the total number of employees. In 1998, this scheme was replaced with a work permit that charged an annual flat fee of Rial Oman 120 (US $ 320) for each expatriate employed in the country.

| Sectoral establishment | Omanization ratio |

| Banks | 90% |

| Establishment engaged in transport, stores and communication | 60% |

| Finance, insurance and real estate | 45% |

| Industry | 35% |

| Hotels and restaurants | 30% |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 20% |

| Contracts | 15% |

Subsequently the Omanization Follow-up Committee was promulgated by a Royal Decree in 1997 and attached to the Diwan of the Royal Court. The committee is made up of 12 members, five of them from the private sector and the remaining seven members representing the government. The role of the committee is to monitor, follow-up and recommend Omanization plans and programmes. In this capacity, the committee oversees the Omanization targets set by the government for each establishment in the government and private sectors. To this effect an Omanization audit was carried to assess the Omanization targets set for the end of 1996 (see table 5). Results have indicated that the Banking Industry is the only sectorial establishment that has almost achieved the targeted Omanization ratio of 90%. Other establishments have been given a postponement to the end of the year 2000 (Omanization Follow-up Committee, 1999).

Another step in this regard is the decision taken to expand higher education institutions through privatisation programme and to increase student enrollment in the public post-secondary institutes. As a result, in addition to the six private two year colleges in the country, requests to build three private universities have been approved and will be opened in the near future. The aim is to facilitate the graduation of more Omani youth in various areas of specialisation as a measure towards the gradual replacement of the large population of expatriate workforce in the country (Oman Daily Observer, 1999).

The Ministry of Social Affairs, Labour and Vocational Training has implemented a number of Omanization related policies and programmes. For instance a policy on the issuance of a "Green Card" was promoted to acknowledge private sector companies which have achieved excellent levels of Omanization and training of national cadre. The Social Insurance Law covering all Omanies working in the private sector was another policy implemented towards providing job security for the nationals. Another important step taken in the Omanization process was the inclusion of Omanization factor among the criteria for selecting the best 5 factories in the country in the annual contest for the His Majesty's (HM) Cup.

A number of vocational training programmes for Omanies have been set up by the Ministry of Social Affairs, Labour and Vocational Training. These include training programmes in ladies and gents tailoring, light and heavy duty vehicle driving license (water and gas tankers), fuel filling attendants, retailing and real estate sales. In addition, a number of projects and programmes have been established to promote and encourage young Omani entreprenuers. These include the Intilaqa programme (training on starting a small business) sponsored by the Shell company and the Youth Project Development fund set up by the directives of His Majesty.

Another important entity that sa major role in the Omanization process is the Oman Chamber of Commerce and Industry established by the Royal Decree in 1973 (Al Ghorfa, 1998; Oman Daily Observer, 1999). The chamber has set up a Training and Omanization Committee which follows-up and lays down Omanization policies for various economic sectors of the country. It also conducts studies and discusses the obstacles to Omanization in these sectors. The establishment of a department exclusively for training and Omanization is an attestation of the chamber's commitment to this cause. In this light, the chamber is also a member in several government committees concerned with Omanization and training. The chamber is committed to the realisation of Omanization in the private sector and encourages private sector companies to replace their expatriate workers with Omanies as far as possible.

Implications For Human Resource Management & Training in the Sultanate of Oman

In an era of intense competition due to economic liberalisation and globalisation, nations that want to survive and succeed need to think more carefully and analytically about managing and training their human resource. In the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, it is a common practice to talk about "Gulfization". Everyone has become an expert on the subject including those with remote affiliation to the area of economics, business or demographics. The challenge boils down to this: what do we really mean by Gulfization/Omanization? Is it merely a process of replacing foreign workers with locals? Or is it simply an exercise in manipulating numbers and statistics?

Human resource managers and decision-makers are faced with a challenge to assess which strategy they will, or rather can, adopt to effectively manage and train human resource. In the Sultanate of Oman, in view of the current manpower predicament with almost ninety two percent (92%) of expatriate workforce in the private sector, the need for a well planned and coordinated human resource management and training programme for Omani nationals is crucial and in this case indispensable. The importance of human resource development & training has been accorded top priority throughout the Sultanate of Oman's successive Five-Year Development Plans. Notwithstanding the challenges and obstacles, the government has made a concerted effort through supported Omanization schemes and incentives to promote Omanization in both the public and private sectors. Major improvements in Omanization have been achieved in the public sector with almost 70% Omanization but the private sector still remains a challenge.

The obstacles to Omanization in the private sector are still formidable and some would argue, growing more intractable. Significantly outnumbered by foreign (expatriates) workforce, Omanies represent a small percentage (8%) of the private sector workforce. A number of studies (Al-Ghorfa, 1998, Al-Lamki, 1998, Al-Maskiry, 1992; Eickelman, 1991; Oman Vision 2020,1995) have indicated that some of the major impedimants to the realization of a high percentage of Omanization in the private sector is the lack of coordination between the government and private sector and a mismatch in the supply of Omani labour in terms of skills and competency required by the private sector.

Other reported obstacles to Omanization in the private sector include lack of public awareness about job opportunities in the private sector, reluctance of the private sector employers to recruit unqualified, less experienced and more expensive Omani labour, lower salaries, longer working hours, fewer holidays, and a foreign (non-Arabic/Omani) dominated organizational culture operating in a foreign (English) language. The government is trying its best to remove these hurdles especially in the area of non-compliance of the training with the private sector requirments. Needless to say, much remains to be done to encourage coordination and cooperation between and amongst government constituencies entrusted with Omanization and the private sector.

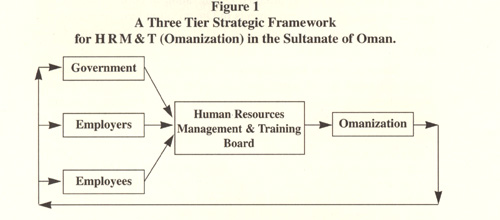

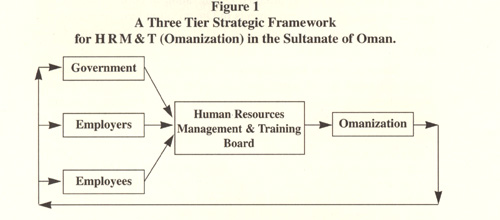

Nation building is the work of all significant actors in a country. The three solid partners-government, employers and employees-bear responsibility for this work. To this effect, the researcher proposes the following three tier (tripartite) strategic framework for human resource management and training.

A Three Tier Strategic Framework for Human Resource Management and Training in the Sultanate of Oman

The three tier (tripartite) framework is made up of the Government (Tier 1), the Employer (Tier 2), and the Employee (Tier 3). The fundamental premise of the tripartite framework (see figure 1) is the interdependencies of each tier. This would result in a defacto alliance that would formulate policies and guidelines that refelct the needs and objectives of Omanization. In this regard, the researcher has recommended Omanization policies and strategies for each tier and integrated all three into a holistic framework for potential consideration and application.

Figure 1: A Three Tier Strategic Framework for H R M & T (Omanization) in the Sultanate of Oman.

An integral component of the tripartite framework is the function membership and credibilty of a "facilitator". It is proposed that a high-powered professional board endowed with legislative and executive powers be established. This board is refered to as the Human Resource Management and Training (HRM&T) board. The board is to be chaired by a government Omani executive and membered by representatives from the government, the private sector and the employees. The primary function of this board is to be a facilitator in ensuring that the three tiers maintain an integrated aproach. It may also play an important role in resolving any conflicts which may (inevitably) arise between the respective tiers. It's executive powers are only to be exercised if there is an impasse in reaching a concensus on a policy or guidelines, as well as in finalizing common policies and procedures approved by the three parties. The aim is to work collectively and to avoid duplication of financial and administrative resources. The HRM & T board would actively foster partnership and alliances with a common vision and a directed mission towards the successful implementation of HRD policies and strategies that are conducive to the realization of Omanization in the Sultanate of Oman.

I. National Level (Tier 1)

Policies & Strategies

Omanization is a National Objective. Therefore it is the responsibility of all the constituents of Oman to exert a concerted effort in its implementation and success.

In accordance with Oman's vision 2020 principal objective of human resource development, the government needs to initiate a comprehensive national strategic human resource planning & development by taking into consideration the national economy and its corresponding manpower needs. The aim being to match the supply of labour in terms of skills and competency with market requirements.

Pursuant to the tripartite framework for human resource management and training, it is crucial to promote a holistic and integrated approach between the government, employers and employees to facilitate constructive dialogue and foster partnership in order to affect HRD policies and strategies that are conducive to economic development and growth. In this regard, it is important to develop and promote a culture of coordination and collabouration between all government entities entrusted with the responsibility of Omanization.

The government should continue to regulate and monitor the process of Omanization in the public sector and most importantly in the private sector given the presence of a predominantly expatriate work force. This is to be carried strategically by pursuing a comprehensive study on the profile of the private sector's job and manpower composition (analysis). Accordingly, the government should embark on a rigorous training and development programme in order to promote the employment of nationals in the private sector. This is to be accompanied by government mandated Omanization policies and mechanisms to stem the inflow of foreign workers. To this effect, measures such as government enforced Omanization targets for management and non-management positions in the private sector need to be clearly identified, sanctioned and regulated. Other measures include government imposed permit requirements and fees for foreign workers, and attractive incentives and preferential treatment for private sector companies adhering to Omanization policies. This however should be managed and executed professionaly without compromising quality of work or jeopardising the business interests of investors.

The government needs to establish a computerized central Census Bureau. The aim is to ensure an up-to-date and accurate population profile that reflects comprehensive demographics and a professional profile. It is recommended that this central database include a Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT) for all occupations available in the public and private sectors. This is to be accompanied by the establishment of private service professional manpower agencies preferably managed by Omanies. To facilitate the placement of Omanies in the private sector, such agencies should be linked electronically to the Central Census Bureau. This is to ensure a "good fit" (match) between the manpower needs of private sector with qualified Omanies.

Human Resource Development (HRD) Policies

Oman is a young nation. Almost fifty six percent (56%) of its population is under the age of sixteen. It is therefore recommended to prioritize investment in quality education for Omani nationals at all levels, specifically at post-secondary levels. In this regard, the government should evaluate and assess the general (pre-tertiary) and post-secondary (tertiary) educational system (including technical and vocational training) and determine its effectiveness in meeting and fulfilling the market needs for manpower.

The three major components of Human Resource Development (HRD), i.e., education, training and development are the principal catalyst and determinants of the quality of the national workforce. In this light, the government needs to establish partnership and promote coordination between all educational and training institutions, particularly general education and higher education to ensure quality programmes and curriculum for developing a highly skilled, well-qualified and flexible national workforce. The establishment of an accreditation agency is recommended to ensure quality control and adherence to the International Educational Standard by all educational and training institutions in the country.

Since education is one of the fundamental pre-requisites to economic development and growth, remedial measures need to be taken to improve the quality of education by improving the curriculum and quality of teachers. In this regard, it is recommended to develop and encourage teaching and learning methodology that promote student-centered learning, problem solving skills, analytical skills, thinking skills, and a curriculum that promotes science, mathematics and information technology. Furthermore, since English is the international language of communication, and is also the medium of international business transactions, and since English is the operational language in Oman's private sector, it is recommended that the level and standard of English taught in schools and institutes of higher learning be strengthened and improved.

The government need to ensure the development of a national cadre (Omanies) to face the challenges of a changing and competitive world (Globalisation). The aim should be to attain a level of education and competence that is recognized internationally.

II. Employer's Level (Tier 2)

Policies & Strategies

Omanization is a Corporate Responsibility. Therefore all private sector employers should include Omanization in their corporate mission and strategy. This however should be done professionally without compromising the standards and quality of work, performance and productivity. Subsequently the business interest of private sector employers should be safeguarded.

Human resource management (HRM) positions should be managed by educated and experienced professionals (preferably Omanies) who possess the competency and expertise in HRM functions of Staffing, Orientation, Training & Development, Motivation and Retention. To this effect organizations should have the following HRM policies & practices:

A clearly articulated corporate mission statement on Omanization. A strategic human resource & career planning and development programme for Omanies. A well devised Omani employees recruitment and selection process. A database of job description and specification. A well devised employee (specifically for Omanies) orientation programme. A well devised (TNA) employee training (Omanization) programme. An objective (task & target oriented) performance appraisal system. A transparent (performance oriented) promotion policy. A well devised motivation and retention policy for Omani employees.

Human Resource Management & Training (Omanization) Policies

Management of private sector employers should be held accountable for Omanization. The targeted percentages of Omanization mandated by government should be handled strategically with a professional response in the form of a realistic and viable Omanization plan. An integral componant in the Omanization plan is the orientation and induction of Omanies to the private sector, corporate culture and work environment. The private sector in Oman which is predominantly managed and manned by expatriates has developed an expatriate oriented culture and ethos. Therefore it is important to "acculturate" and prepare Omanies mentally, intellectually and socially for private sector employment.

Employment preference should be given to Omani nationals provided they qualify for the positions. This is to be executed by professional human resource management mechanisms of proper job analysis, recruitment and fair selection process. Pursuant to the selection process, orientation and training of Omani recruits need to be carried out professionally and in line with the job description. This is to be accommpanied by a clause in the employment contract of expatriates requiring them to train Omanies. This should be time bounded followed by the replacement of the expatriate with a competent Omani. To ensure this process, it is recommended to install an incentive system in the form of monetary rewards to encourage expatriate employees to train and develop Omani employees.

There exists a dire need to promote and develop a cadre of Omani managers and decision makers. This is to be executed through a professionally tailored human resource and career planning and development programme. In this light, private sector employers are recommended to initiate an "Omani Graduate Scheme" that encourages the recruitment and development of university graduates for management positions. The experience of successful Omanization programmes achieved by some of the private and semi-private companies should be studied for potential adaptation. Since in the majority of cases, graduates of Sultan Qaboos University and other institutes of higher learning lack work experience, private sector employers are urged to develop training and development programmes for Omanies and request the assistance of experienced expatriates to pass on their expertise to their Omani coworkers. This can be carried through well designed on-the job and off-the job training, apprenticeship, understudy and mentorship programmes.

III. Employees' Level (Tier 3)

Omanization is a Social Responsibility. Therefore each and every citizen of the country should commit themselves professionally to the realisation of this national goal. His Majesty Sultan Qaboos in his direct contact with the citizens during His annual meet-the-people tours, always urges the youth to utilise all available job opportunities, whether in the public or private sector, as a service to the country and to support their own lives.

Since the dawn of the national renaissance in 1970, Omanies have been encouraged and attracted to work for the government sector. This trend was conducive in the 70s and 80s due to the availability of plenty of job opportunities brought about by the acute shortage of skilled and educated Omani manpower. Futhermore, the conditions of work and the remuneration package was relatively attractive. This was supported by the nurturance of an Omani/Arabic culture and ethos considered an attractive feature for the Omani workers. In the meantime, the private sector developed into a primarily expatriate (non-Omani/Arabic) oriented culture with English as the medium of communication and operation. Consequentely, such differences have resulted in developing a distinctive cultural dichotomy between the government and private sector. This distinction include different management practices and supervisory style, organisational culture, work conditions, remuneration and other related work environment. This distinction can no longer be sustained and needs to be addressed very seriously by the government and the private sector employers in order to remove the gaps and associated hurdles as a measure towards encouraging Omani employees to work for the private sector.

The Omani employees should realize that economic and social conditions have changed in that the decades of the 70s and 80s with plenty of job opportunities in the government sector no longer exists. The government sector is saturated and can not continue to absorb anymore Omanies. Jobs are going to be generated in the private sector, and the onus is now on the private sector to employ Omanies and for Omanies to take their jobs seriously and to commit themselves professionally. This is especially the case with the privatization and diversification programmes in the country whereby the private sector is considered to be the primary driving engine of the national economy. Hence Omani employees should be made to understand the current economic conditions and appreciate the value of getting and keeping a job in a period of intensive regional and global competition.

The Omani society, through its various institutions, such as family, media, schools, colleges, universities, mosques and all other social communities should promote and nurture positive values and attitude towards work. There is a need to instill confidence in the citizens' ability to pursue work successfully and to inculcate a sense of duty and responsibility among the citizens to serve their country to the best of their knowledge and ability. This responsibility is clearly spelled out in the teaching of Islamic values towards positive work ethics. For instance, the Holy Quran and the sayings of Prophet Mohammed (PBUH) promote the following positive work ethics:

"To all are degrees (or ranks) according to their deeds."

"To men is allotted what they earn, and to women what they earn."

"That man can have nothing but what he strives for." (The Holy Quran)

"No man eats better food than the one who eats out of the work of his hands." Furthermore, Prophet Mohammed said, "No doubt, you had better gather a bundle of wood and carry it on your back and earn your living thereby, rather than ask somebody who may give you or not." (Sayings of Prophet Mohammed)

Conclusion

This paper addressed the issue of human resource management and training with particular emphasis on Omanization (the replacement of expatriates with Omanies) in the Sutlanate of Oman. The preceding discussion has attempted to describe the Sultanate of Oman's experience on Omanization with particular reference to the private sector. This has been demonstrated by the profile of the total workforce in the Sultanate of Oman along with government supported Omanization policies, schemes and incentives.

Analysis of the current manpower predicament suggests that a missing link in the successful realisation of Omanization in the private sector is a holistic and integrated coordination and cooperation between the government, the private sector employers and the employees. Underlying this mutuality is the notion that individuals depend on organisations to provide them with opportunities to utilise their skills and competencies and that organisations need to match skills and competencies to jobs. Despite the government's considerable effort and active role in encouraging and promoting Omanization (employment of nationals) in the private sector, slow progress has been achieved in this endeavor and the ratio of Omanies to expatriates in the private sector is very low. A significant majority (92%) of the overall private sector employment are non-Omanies (expatriates). The predicament presents a major challenge to realisation of the government's goal of Omanizing the private sector.

In view of the above orientation, the researcher recommended an integrated and holistic three tier strategic framework for human resource management and training (Omanization) in the Sultanate of Oman. The Omanization process, as mentioned earlier, being a national challenge, makes it imperative that all citizens of this great nation to exert maximum effort towards implementing the policies of this process ensure its success. Accordingly, each and every individual, whether he be a father, a businessman, a decision maker in a government or a private sector establishment, has an integral role in this regard and Omanization cannot be achieved without holistic and coordinated effforts of all players. It is therefore with this premise in mind that resulted in the design of an integrated and holistic framework that encompasses all stakeholders' roles towards successful realisation of Omanization.

References

Al-Ghorfa, (1998). Omanisation in the Private Sector. Al-Ghorfa, No. 113. Sultanate of Oman: Oman Chamber of Commerce & Industry.

Al-Ghorfa, (1999). Reducing Dependence on Expatriate Labour. Al-Ghorfa, No. 118. Sultanate of Oman: Oman Chamber of Commerce & Industry.

Ahuja, V. (1997). Everyones' Miracle? Revisiting Poverty and Inequality in East Asia, Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Al-Lamki, S. (1998). Barriers to Omanization in the private sector: the perception of Omani graduates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 9.

Al Markazi, (2000). Administrative ramifications of bank mergers & acquisitions an empirical evidence of Oman. Central Bank of Oman: Sultanate of Oman.

Al-Maskery, M.M. (1992). Human Capital Theory and the Motivation and Expectations of Univeristy Students in the Sultanate of Oman. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Missouri, St Louis, USA.

Aryee, S. (1994). The social organization of careers as a source of sustained competitive advantage: The Case of Singapore. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 5, 67-87.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17: 99-120.

Birks, J.S. and Sinclair, C. A. (1980). Arab manpower: the crisis of development, London: Croom-Helm.

Birks, J. S. and Sinclair, C. A. (1987). Successful Education and Human Resource Development. In Pridham, B. R. (ed.) Oman: economic, social and strategic development, pp. 1-16, London: Croom-Helm.

Campos, J. and Root, H. (1996). The key to the Asian miracle: making shared growth credible. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Chew, S. and Chew, R. (1995). Immigration and foreign labour in Singapor. ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 12, 191-200.

De Cenzo, D. A. & Robbins, S. P. fourth edition (1994). Human resource management: concetps & practices. USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Dreyfus, J. (1990). Get ready for the new work force. Fortune (April 23,1990), p.167.

Eickleman, Dale, F. (1991). Counting and surveying an inner Oman community: England: Menace Press.

Ernest & Young (1990). Private sector training needs assessment. Oman American Joint Commission. Sultanate of Oman.

Maloney, W. (1998). The structure of labour markets in developing countries: time series evidence on competing views. World Bank Report. World Bank: Washington D.C.

Ministry of Social Affairs, Labour and Vocational Training. Muscat: Sultanate of Oman. N.d.

O'Reilly, B. (1992). Your new global workforce. Fortune (December14, 1992), p.52.

Oman Daily Observer (1999). Omanisation Gains Momentum, p 12, Thursday, 18 November. Muscat: Sultanate of Oman.

Omanization Follow-up Committee (1999). Omanization Report. Sultanate of Oman.

Peterson, J. E. (1978). Oman in the twentieth century. London: Croom-Helm.

Peterson, J. E. (1987). Oman's Development Strategy. In Pridham, B. R. (ed.) Oman: economic, social, and strategic development, pp. 20-26. London: Croom-Helm.

Porter, M. E. (1990). Competitive advantage of nations. New York: Free Press.

Rowe, Peter C. (1992). A Framework for an Human Resource Development Strategy. Support Paper for Oman HRD Conference. Muscat: Sultanate of Oman.

Ruppert, E. (1998). Managing foreign labour in Singapore and Malaysia: are there lessons for GCC countries? World Bank Report. World Bank: Washington D.C.

Schneder, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Autum 1987), p. 437.

Shaeffer, W. G. (1989). Civil Service Development in Oman: A Report on the Problem of Omanization of the Private Sector. Muscat, Sultanate of Oman.

Stalker, P. (1994). The work of strangers: a survey of international labour migration. International Labour Office: Geneva.

Statistical Year Book (1999). Ministry of National Economy, Sultanate of Oman.

Townsend, J. (1977). Oman: The making of a modern state. London: Croom-Helm.

Wong, D. (1997). Transience and settlement: South-East Asia's foreign labour policy. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 6.

World Bank (1994). Sultanate of Oman: sustainable growth and economic diversification. Report No. 12199-OM.