Volume 7, No. 1 June 2004

By

Jan P. Muczyk

Air Force Institute of Technology, Ohio, U.S.A.

As indicated by the literature, leader behaviors, salient management practices (management by objectives and compensation practices), organizational structure, and organizational culture were chosen as the dimensions with the greatest impact on business/competitive strategy implementation. So as not to over-generalize, business level strategies were collapsed into two - retrenchment and growth. For similar reasons, the competitive strategy schema was simplified in such a way that competition only on the basis of price and innovation was retained. Informed by relevant literature and case studies, implementation guidelines were crafted that appear to have considerable practical utility.

INTRODUCTION

Both academic and practitioner alike tell us that in the U.S. it is not inadequate strategizing and decision making that are the problem, but flawed implementation. For example, H. Igor Ansoff (1988), a well-known strategic scholar, states: "It is no trick to formulate strategy; the problem is to make it work." U.S. automobile executives conclude: "We strategize beautifully, we implement pathetically" ("Detroit Downer"...1991). Gen. Omar Bradley observed: "Drawing the plan is 10% of the job; seeing that plan through is the other 90%." Napoleon Bonaparte went so far as to say: "The art of war is simple; everything is a matter of execution" (Bevin, 1993). Floyd & Wooldridge (1992: 27) go on to say:

A frequent complaint of senior executives is that middle and operating managers fail to take the actions necessary to implement strategy. As one top manager told us: 'It's been rather easy for us to decide where we wanted to go. The hard part is to get the organization to act on the new priorities.'

Systems theory informs us that all the parts must fit properly for the system to work as intended. The concept of fit in an organizational context began receiving widespread attention with the publication of Strategy and Structure (1962) by Alfred Chandler, who argued largely on inductive and experiential grounds that a firm's strategy, its structure, and its managerial processes have to "fit" with one another. The work of Burns and Stalker (1961) and Woodward (1965) further legitimized the concept of fit by demonstrating the relationship between organizational performance and how well structure, technology, and human resources support each other. Perhaps, it is the lack of fit that in part accounts for such a poor record of strategy diversification via acquisition (Porter, 1987).

A FIT BETWEEN HUMAN RESOURCE PRACTICES AND ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE

More recently, a number of scholars advanced the proposition that human resources can provide a source of sustained competitive advantage through a linkage between certain organizational variables, such as human resource management practices, and organizational performance (Arthur, 1994; Cutcher-Gershenfeld, 1991; Huselid, 1995; Huselid & Becker, 1996; MacDuffie, 1995; Schuler & Jackson, 1987).

Recognizing the complexity of organizational linkages, some researchers have distinguished not only between two types of fit (Baird & Meshoulam, 1988), but also between two kinds of human resource practices (Huselid, Jackson & Schuler, 1997). Internal fit refers to the degree to which human resource practices complement and support each other, while external fit refers to the extent that human resource management components fit the developmental stage of the organization. Technical human resource policies and practices refer to traditional personnel functions, while strategic human resource activities refer to such concepts as team-based job designs, flexible workforces, quality improvement practices, employee empowerment, studies designed to diagnose a firm's strategic needs, and development of talent needed to execute the organization's competitive strategy and achieve operational goals. Venkatraman (1989) goes on to identify six perspectives of fit: Fit as moderation; fit as mediation; fit as matching; fit as gestalts; fit as profile deviation; and fit as co-variation. Furthermore, each type of fit requires its own methodology.

A MORE HOLISTIC APPROACH TO FIT

Justifying Choices of Variables

Informed by the literature, the author decided to align critical leader behaviors, salient management practices, organizational structure, and organizational culture with the business/competitive strategies that an organization wishes to pursue. Nohria, Joyce & Roberson, (2003) demonstrated empirically that companies that outperformed their industry peers excelled at what they call the four primary management practices: Strategy, execution, culture, and structure. And they supplemented their skill in those four areas with a mastery of any two out of four secondary management practices: Talent, innovation, leadership, and mergers and partnerships. Collins (2001), while identifying the primacy of having top-notch people, also stressed the importance of developing a viable business model (strategy). From then on, Collins (2001) pointed out that perseverance is crucial as well, and part and parcel of perseverance is the discipline to confront unpleasant tasks and difficult situations; all the while persisting in the development of solutions without losing faith.

Locke et al. (1980) state: "In the history of industrial-organizational psychology, only four methods of motivating employee performance have received systematic attention by researchers. These are [in order of importance]: Money, goal setting, job enrichment, and participation." Consequently, compensation schemes, management by objectives (MBO), and leader behaviors absolutely need to be considered. Moreover, as has already been mentioned, scholars have identified some time ago organizational structure as an important organizational variable to consider. More recently, organizational culture has been highlighted as a significant determinant of organizational performance (Schwartz & Davis, 1981).

The first set, including leader behaviors and critical management practices such as management by objectives (MBO) and compensation strategies, is relatively easy to change in the short-run. The variables in the second set are also important, but tend to be far more difficult (or less appropriate) to change in the short term, such as the nature of the organization's structure, culture, and quality of its people. While organizational structure can be changed in the short-term, the disruption that results from major reorganization makes frequent use of this device undesirable. A substantial amount of research suggests that major changes in culture and quality of human resources can take several years of constant effort (Schwartz & Davis, 1981). It appears that the alignment approach such as the one suggested here is being put to practice by Michael Beer and Russell A. Eisenstat in their capacity as consultants (Ross, 2002).

What Is Strategy?

While Strategy has been organized in many ways, at the strategic business unit level it has been defined here as a plan, written or otherwise, that contains an organizational mission or purpose and the means for attaining that purpose. So far as the business purpose or mission is concerned, a collapsed version of Glueck's (1976) model (see endnote 1), viz., growth and retrenchment, has been selected. To accommodate the competitive advantage aspects of strategy or the means of attaining the business purpose, a simplified variant of Porter's (1985) approach (see endnote 2) has been adopted, viz., cost leadership and one type of differentiation, and that is innovation. Breaking out quality as a separate component of Porter's (1985) differentiation competitive strategy has been omitted, for if we have learned anything from the Japanese over the past quarter of a century, it is the importance of quality regardless of the competitive strategy that a firm selects.

Even companies competing at the lower end of the product spectrum must appreciate the primacy of quality and provide it to customers. An excellent example is the Saturn line of automobiles. Even though Saturn is a low-cost alternative, on quality it frequently ranks alongside the top imports on owner surveys recognized by the industry. Furthermore, we must take care not to confuse luxury with quality. While a Rolls Royce has luxury, both have quality. Trying to align the critical variables that have been identified with the fully elaborated, original versions of Glueck's (1976) and Porter's (1985) paradigms would constitute an unsupportable stretch at this juncture of the state of the art.

Perhaps less harm is done by this simplification than appears at first blush, since managing stability and growth, while challenging enough, typically does not call for the kind of gut-wrenching decisions that are required when pursuing retrenchment/turnaround strategies - the kind of decisions that distinctly conflict with self-interest; thereby making them unlikely to be made by democratic processes. For example, when pursuing retrenchment/turnaround strategies, managers need to be replaced, employees must be terminated, and many disruptions to customary practices necessitated (Muczyk & Steel, 1998).

Nexus Between Leadership and Strategy

Although numerous studies link personal characteristics of managers, managerial skills, managerial experience, and managerial actions with strategy implementation, there is a relative paucity of research connecting leader behaviors and organizational systems to strategy implementation. The exception is the work of Wooldridge & Floyd (1990) that demonstrates that involving middle-level managers in strategy formation is associated with organizational performance. Just as importantly, they present a practical approach for closing the gap between strategy development and execution (Floyd & Wooldridge, 1992).

Both experience and research strongly suggest that a connection exists between strategy and leadership. Reginald H. Jones, former CEO of General Electric, noted some time ago: "When we classified...[our]...businesses, and when we realized that they were going to have quite different missions, we also realized we had to have quite different people running them" (Schuler & Jackson, 1987). Hofer & Schendel (1978) also observed that in moving from a growth to a turnaround strategy, or from a hold-and- defend to a divestment strategy, managerial behaviors should change appropriately. Herbert & Deresky (1987) found that even the implementation of different organizational strategies (i.e., develop, stabilize, and turnaround) calls for general managers with different sets of managerial actions, skills, experience, and behaviors. Gupta & Govindarajan (1984) also discovered a relationship between strategic intentions (i.e., build, hold, harvest) and managerial actions and skills. Others have discerned important interactions between compensation and competitive strategies (Muczyk, 1988) and between compensation and organizational culture (Kerr & Slocum, 1987). Schuler & Jackson (1987) highlight the relationship between compensation and competitive strategy with a quote from Peter Drucker:

I myself made this mistake [thinking that you can truly innovate within the existing operating unit] 30 years ago when I was a consultant on the first major organizational change in American history, the General Electric reorganization of the early 1950s. I advised top management, and they accepted it, that the general managers would be responsible for current operations as well as for managing tomorrow. At the same time, we worked out one of the first systematic compensation plans, and the whole idea of paying people on the basis of their performance in the preceding year came out of that. The result of it was that for ten years General Electric totally lost its capacity to innovate, simply because tomorrow produces costs for ten years and no return. So, the general manager - not only out of concern for himself but also out of concern for his group - postponed spending any money for innovation. It was only when the company dropped this compensation plan and at the same time organized the search for the truly new, not just for improvement outside the existing business, that GE recovered its innovative capacity, and brilliantly. Many companies go after this new and slight today and soon find they have neither.

Critical Leader Behaviors - Participation and Direction

For better or for worse, when it comes to leadership theories, there is an embarrassment of riches. The Muczyk/Reimann (1987) mid-range leadership framework was selected, since it is a serious attempt at reconciling many of the mid-range leadership theories. According to their model, the aspects of leader behavior most relevant to the implementation of different strategies appear to be those that concern themselves with 1) the decisions managers make and 2) the way these decisions are then executed. The set of leader behaviors known as participative management is primarily associated with decision-making. A less familiar dimension of leader behavior is principally concerned with executing decisions, once they have been made. This is the dimension of leader direction or follow-up (Muczyk/Reimann, 1987).

Participatory management or leadership is typically defined in terms of the degree to which employees are involved in significant day-to-day, work-related decisions. However, the participation of employees in making decisions is a separate issue from the amount of direction that a leader provides in executing those decisions. Thus, a leader can be participatory or democratic by consulting employees during the decision making phase, yet still be directive by following up closely on progress toward the ends that have been mutually decided.

By combining the extreme points on the two situational continua - participation and direction - the result is four "pure" patterns of leader behavior shown in Exhibit 1.

Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan could be included in the permissive autocrat category. Both men established a national agenda, surrounded themselves with people they trusted, and delegated the rest. However, for delegation to work well, the delegatee must keep the delegator completely informed. President Roosevelt kept himself informed, while President Reagan did not; and for this leadership flaw, President Reagan paid with the Iran-Contra Affair (Dunham & Pierce, 1989: 385). President Jimmy Carter, a directive democrat, spent much oh his time on policy details. That is to say, he got into the weeds on any issue that had technical content. This turned out to be an inappropriate leadership style for the CEO of such a large and complex enterprise as the United States of America.

| Exhibit 1 Types of Leader Behaviours |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of Participation in Decision Making | Low | High | |

| Directive | Directive | ||

| High | Autocrat | Democrat | Amount of Leader Direction |

| Permissive | Permissive | ||

| Low | Autocrat | Democrat | |

Source: Muczyk, J. P. & Reimann, B. C. 1987. "The Case for Directive Leadership," Executive, 1, 304.

While the permissive democrat leadership style, with its generous doses of subordinate participation accompanied by large measures of autonomy, is the distal state of the leadership evolutionary process, we should not be beguiled by the virtual stranglehold that participative leadership has maintained over popular belief systems since the end of WW II. Surely, the bulk of U.S. organizations are hardly representative of the handful of "excellent" companies known to us by name that prosper under participative and permissive management styles. Until these enterprises are transformed into "excellent" companies, they need a leadership style that is more suited to their difficult circumstances (Muczyk & Reimann, 1987). After all, the review of the participation research by Locke et al. (1980) indicates that participation in decision making is the least effective way of motivating employees of the four most popular managerial approaches studied.

We often lose sight of the fact that the directive autocrat is not some misanthrope or ogre, but merely a person who is paid to make the important decisions, set the salient goals, and direct subordinates along the way - especially in a crisis, when subordinates tend to rally around a decisive leader. While there is agreement that more power equalization exists in organizations now than ever before, and that in all likelihood the "zone of indifference" is shrinking, nevertheless, most employees still concede to their superior the right to make decisions and set goals, as well as the authority to direct the process leading to those results. So long as the decisions and goals are considered by subordinates as legitimate and reasonable, and the subordinates are treated with courtesy, dignity, and respect, the autocratic and directive supervisor, manager, or executive is received much better by subordinates than management literature - academic and practitioner alike - would have us believe. A caveat is in order, however, regarding this leadership style. For obvious reasons, "directive/autocrats" normally do not groom successors very well, and this legacy can lead to a succession crisis.

Leading Change

It is difficult to overestimate the prepotency of change as the principal driving force of contemporary and future organizations, and the necessity of leaders to respond appropriately to the radical changes that are buffeting organizations and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Consequently, leading change is becoming increasingly more important. Thus, Yukl, Gordon & Taber (2002) have included leading change with task and relations as vital leadership behavior dimensions. Therefore, such activities as monitoring the external environment, envisioning change, encouraging innovative thinking, and taking personal risks to implement change should occupy more of the leaders time, especially in companies facing a dynamic environment (Yukl, Gordon & Taber, 2002).

In Mintzberg's (1973) formulation, however, leading change appears to this author to be another managerial role heavily influenced by contextual forces; as opposed to being an essential aspect of the leadership role. In any case, the three most successful strategies for introducing change are: 1) Attempting the change on a trial basis as a pilot program; 2) involving the employees in the change from the beginning; 3) making certain that timely and accurate two-way communication takes place. In the final analysis, it is the trust level that determines the employees' attitude toward change.

Certainly, more and more successful organizations tend to anticipate and embrace change, foster a participative culture, and organize hordes of workers into more productive, smaller work teams. Nevertheless, in today's intensely competitive world, a number of floundering firms still need to be transformed quickly into lean, growth- driven, performance-based enterprises with global perspectives. And at times these transformations must be driven by autocratic and directive CEOs and their key subordinates because of the hard decisions that must be made.

Management by Objectives (MBO)

An important prerequisite to effective implementation is a mechanism by which employee behaviors are ultimately linked to strategic goals. Such a device is management by objectives, providing it is synchronized with prevailing leadership styles. MBO is also a key instrumentality for providing direction and impetus - key elements of leadership. Moreover, MBO is quite useful so far as performance appraisals and compensation practices are concerned, especially for managers and executives. MBO was selected not only because it fills the bill, but also because in its essentials it is enduring, even though under different names (Gibson & Tesone, 2001). Ideally, the MBO process involves five distinct phases: 1) Goal setting, 2) action planning, 3) periodic reviews, 4) performance appraisal on the basis of degree of goal attainment, and 5) rewarding organizational members in accordance with degree of goal difficulty and attainment whenever possible. The participation continuum is affiliated primarily with the goal-setting phase, while the direction dimension focuses on the goal attainment phases.

Thus, MBO can be an important management tool for eliciting the specific actions required for the execution of a particular business strategy. MBO is also an important complement to the leadership role that a manager is expected to exercise. Consequently, it is vital to harmonize MBO with crucial leadership dimensions such as subordinate participation and leader direction (Muczyk & Reimann, 1989). The circumstances that warrant directive autocrat leadership also dictate autocratic and directive MBO. In like manner, permissive democrats logically should employ democratic and permissive MBO, etc. See Exhibit 2.

| Exhibit 2 MBO Genotypes |

||

|---|---|---|

| Extensive subordinate participation in goal setting | No subordinate participation in goal setting goal setting | |

| High supervisor involvement in action planning, frequent review, and supervisor-dominated appraisal | Democratic and Directive MBO | Autocratic and Directive MBO |

| Little supervisor involvement in action planning, infrequent review, and self-appraisal | Democratic and Permissive MBO | Autocratic and Permissive MBO |

Source: Muczyk, J. P. & Reimann, B. C. 1989. "MBO as a Complement to Effective Leadership," Executive, 3, 135.

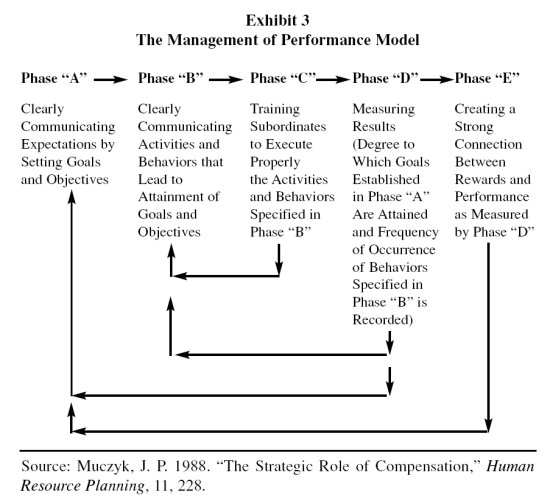

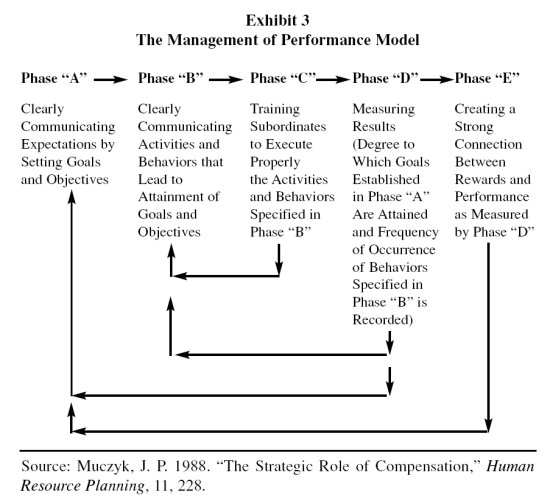

A properly implemented MBO program not only ties strategic goals to employees' objectives and behaviors, but also connects goal attainment to performance evaluation and the organization's reward structure: thereby creating the necessary motivational, planning, and control conditions for individual and organizational success. Moreover, managing employees with properly set goals, after monetary incentives, is the second most effective method of motivating employees; and in conjunction with monetary incentives, constitutes an even more powerful motivational approach (Locke et al., 1980). Exhibit 3 illustrates the management process by which all this is done. However, for MBO to realize its full potential, it needs top-management commitment, i.e., enthusiastic support and involvement of the entire chain of command, especially the top echelons. Although MBO implementation needs to start at the top, it should be a push and pull process the rest of the way, rather than exclusively top down or bottom up. Research indicates that when top-management commitment was high, the average gain in productivity was 56%. When commitment was low, the average gain in productivity was only 6% (Rodgers & Hunter, 1991).

It should be noted that for goals to regulate performance effectively, feedback or knowledge of results in relation to one's goal is necessary. Put simply, individual employees need some means of keeping track of their progress (Erez, 1977). Stated still another way, most employees will do what is measured and rewarded. The feedback loops in the "management of performance model" of Exhibit 3 satisfy this important condition.

Compensation Strategies

Kerr (1975) observed some years ago that: "Whether dealing with monkeys, rats or human beings, it is hardly controversial to state that most organisms seek information concerning what activities are rewarded, and then seek to do (or at least pretend to do) those things, often to the virtual exclusion of activities not rewarded. The extent to which this occurs of course will depend on the perceived attractiveness of the rewards offered, but neither operant nor expectancy theorists would quarrel with the essence of this notion."

Lawler (1984) identifies five factors related to efficiency and effectiveness of strategy implementation that are influenced by organizational reward systems: 1) Attraction and retention of personnel; 2) motivation; 3) organizational culture; 4) organizational structure; and 5) cost. Hence, it is necessary to demonstrate how congruence between rewards and the other organizational variables that are instrumental to strategy implementation can be attained.

Muczyk (1988) concluded that the U.S. has become an "instrumental" culture; and it is crucial in such a culture for employees to be convinced that their effort leads to performance and performance, in turn, leads to valued rewards. In a monetized, industrial society, money takes on the role of a generalized reinforcer. Because of its utilitarian as well as its symbolic value, money serves as a reward for most behaviors, for most people, most of the time. Therefore, instituting performance-based pay systems in U.S. organizations is imperative, since connecting monetary rewards to performance appears to be most effective way of motivating employees (Locke et al., 1980).

However, the relationship between performance and rewards is quite complex. Different business/competitive strategies supported by appropriate organizational cultures intervene between organizational goal attainment and the compensation mix that the organization selects. In other words, there needs to be congruence between strategies that are being pursued, organizational structure, organizational cultures that support these strategies, and reward systems that elicit and maintain behaviors that are consonant with the selected business/competitive strategies.

At the broadest level, we can classify compensation as either related to organizational membership or to performance. Indirect compensation (fringe benefits) is intended to motivate individuals to join and remain with the organization. Indirect compensation is not intended to motivate employees to perform at higher levels, and no one should be surprised that it doesn't. Indirect compensation can be fixed or presented in a cafeteria-style format.

Pay-for-performance is predicated either on the basis of output or the value to the organization of the job that an occupant holds. The differences between the two methods need not imply that the connection between performance and rewards is necessarily greater when pay is based on output as opposed to one's job. In those instances when the output standards are low and the pay rates per unit are excessive, the nexus between performance and rewards is weak. On the other hand, the nexus between performance and rewards is quite strong in those organizations that pay on the basis of the job one holds, but grant annual or semi-annual merit increases as the result of performance differentials captured by reliable and valid performance appraisals.

When the connection between performance and compensation is weak or absent, regardless of whether or not the ostensible pay scheme is for output employees produce or the worth of the jobs they occupy, then the organization is paying for attendance instead of performance. In fact, performance appraisals are the Achilles heel of compensation systems in many organizations, since too often they do not discriminate in a significant way between mediocre, average, and superior performance as the result of such ubiquitous performance appraisal errors as central tendency and excessive leniency (Muczyk & Gable, 1987). The result is that in too many cases the superior performers are not rewarded in a manner that is proportional to their contributions. And if they experience such an inequity for a protracted period, then they could very well become demotivated. These constitute additional reasons for a properly implemented MBO system.

Another compensation scheme has surfaced recently, which relates compensation to the number of skills an employee has acquired or the number of tasks he/she has mastered. These schemes are at times referred to as "learn and earn" plans. Such a compensation policy requires a leap of faith, since the number of skills one has acquired or the number of tasks one has mastered isn't necessarily related to either output or the worth to the employer of the job the employee is holding. On the other hand, it is argued by proponents of pay-for-knowledge that the added skills give the organization greater flexibility, permit it to operate leaner, and make the employee that much more valuable. An extension of this compensation strategy takes into consideration the employee's formal educational attainment levels, variety and richness of experience, patents held, reputation among peers and in professional organizations, and the role that was played by the employee in the development of successful products - all proxies for innovation.

Since creating the strongest nexus between performance and rewards is vital in an "instrumental" culture, firms should employ individual and group incentive plans to the extent practicable. Also, whenever applicable, organization-wide gainsharing plans such as the Scanlon Plan, the Rucker Share-of-Production Plan, and Improshare are recommended. Profit sharing plans should receive careful consideration as well.

Moderating the preoccupation with short-term performance metrics, a hallmark of an "instrumental" culture, is critical as well. Therefore, deferred compensation for managers and executives tied to intermediate and long-term measures of success should be encouraged, and the board of directors has a special obligation to devise meaningful intermediate and long-term performance indicators. Stock options have their place but also their limitations. In a period of "irrational exuberance," the stock price may very well be unrelated to the contribution of executives; thereby constituting a serendipitous windfall. Placing a dollar ceiling on the amount that an executive can keep would deal with that problem. Preventing the recipient from exercising the stock options for a significant period of time is another alternative.

One of the best ways to create a beneficial motivational climate is to create a sense of ownership best reflected by the motto, "everyone a capitalist." Toward that end, each employee should be given ample opportunity and encouragement to purchase the stock of the company, which would be bought back at employment termination time. Lincoln Electric provides an excellent example of a powerful motivational climate. Even though more than half of the workers at Lincoln Electric are paid on the basis of an incentive plan, the annual bonus (which is typically as large as regular annual earnings) is based on a performance appraisal that considers the following performance dimensions: 1) Ideas and cooperation, 2) output, 3) ability to work without supervision, and 4) work quality (Muczyk, 1988).

Organizational Structure of Core Technology

Burns & Stalker (1961) identified two distinct types of organizations - one they called "mechanistic" and the other "organic." The former is highly bureaucratic, quite rigid, and responds slowly to change, while the latter is very flexible, fluid and responsive. While in actuality very few organizations are pure organic or pure mechanistic, most organizations fall on a continuum between these extreme points. Clearly a structure that tends toward organic would be more suited to the implementation of an innovation strategy, while a structure tending toward mechanistic would better accommodate the mass production of items whose basic composition and methods of production change infrequently. See Exhibit 4. It does not appear that a more elaborate nexus between structure and strategy is warranted at this time.

| Exhibit 4 Characteristics of Mechanistic and Organic Structures |

||

|---|---|---|

| MECHANISTIC | CHARACTERISTICS | ORGANIC |

| Functional Specialization or Departmentalization by Function | Division of Labor | Job Enlargement and Job Enrichment |

| Clearly Defined and Centralized | Hierarchy of Authority | Decentralized and Participative |

| Formal and Standardized | Jobs and Procedures | Flexible |

| Primarily Economic | Motivation | Both Economic and Psychological |

| Authoritarian | Leadership Style | Democratic |

| Formal and Impersonal | Group Relations | Informal and Personal |

| Vertical and Directive | Communications | Vertical, lateral, diagonal and consultative |

Source: Adapted from Gannon, M. J. 1970. Organizational Behavior: A Managerial and Organizational Perspective, (Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Co.), 75.

Network organizations. In an intensely competitive global economy, in order to prosper firms are compelled at times to acquire strategic business units that are misaligned with the salient characteristics of the parent company. One way to deal with the alignment issue is to rely on the concept of a network organization. This organization structure differs from the more traditional types in the following ways:

By relying on a network structure, the alignment challenges disappear for everything but the core competency because they have been outsourced, thereby becoming someone else's problem. Historically, parent organizations have dealt with alignment issues by making subsidiaries or divisions independent so long as their performance is satisfactory. In other words, the holding company merely managed the financial flows of its conglomeration. When performance proved unacceptable, top leadership of the subsidiary or division was replaced. If that did not work, then the subsidiary or division was disposed of.

Organizational Culture

Organizational culture has been defined as shared beliefs, expectations, and values held by members of a given organization, and to which all newcomers must adjust through the socialization process, if they wish to prosper (Greenberg & Baron, 1993). Since corporate culture is often a key to the success or failure of business strategies, it should not be ignored. The significance of organizational culture is illustrated by the following example. Mr. Horst W. Schroeder, President of Kellogg, was terminated by Mr. William E. LaMothe, Kellogg Chairman and CEO. The reason given was a failure of management "chemistry." Mr. Schroeder started out with Kellogg in West Germany as a controller, and later managed Kellogg's European operations, where he accumulated impressive results. But in Battle Creek, Michigan, Mr. Schroeder's colleagues described him as a strong-willed, even imperious, autocratic European. This style conflicted drastically with Kellogg's small town family culture that stressed teamwork, subordinate involvement, and sharing credit with others. Clearly, the contrast between Kellogg's culture and Mr. Schroeder's leadership style was too great to overcome, especially when the performance of the firm began slipping (Gibson, 1989b).

Many observers believe that the cultural differences between Daimler's "exclusive" culture and Chrysler's "strategic" culture made the Daimler/Chrysler merger more difficult than it needed to be. Daimler's leadership must have hoped that the cultural differences between the two partners would somehow sort themselves out, but they did not. Both companies would have been better off had they planned for a cultural alignment up front (Schuler & Jackson, 2001). Further evidence supporting the power of organizational culture has been provided by Cameron & Quinn (1999), who developed an analytic process based on their competing values framework that predicts the success of mergers with considerable accuracy.

The value-based classification of culture adopted here is the one devised by Reimann & Wiener (1988). The two-by-two schema is based on the focus of values (elitist vs. functional) and the source of values (charismatic leader vs. organizational traditions). See Exhibit 5. Also, see endnote 3 for an alternative classification.

| Exhibit 5 Generic Corporate Culture Types |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of Values | |||||

| Charismatic Leadership | Organizational Traditions | ||||

| Focus of Values | Functional | Entrepreneurial | Strategic | ||

| (External, Short-Term) | (External, Long-Term) | ||||

| Elitist | Chauvinistic | Exclusive | |||

| (Internal, Short-Term) | (Internal, Long-Term) | ||||

Source: Reimann, B. C. & Wiener, Y. 1988. "Avoiding the Elitist Trap," Business Horizons, March-April, 39. See endnote 3 for an alternative schema.

"Entrepreneurial" culture is the result of the interaction of charismatic leadership and a functional focus. Such a culture encourages a market/customer orientation, but could evaporate quickly if something were to happen to the founding entrepreneur. A good example of "entrepreneurial" culture is the Japanese manufacturer of robots and computerized numerical controls, Fanuc. Fanuc is not only preeminent in its field, but is the Japanese company with the highest profits. Mr. Seiuemon Inaba, who leads the company, does not smoke; therefore no one smokes. He demands that his orders are followed to the letter, since he believes that "a wise dictator is better than an unwise democracy." Mr. Inaba does not wish his scientists and engineers to read the latest technical books and journal articles lest their creativity be encumbered by what is known. He is known as the "yellow Kaiser of Mt. Fuji" after the imperial yellow color that he imposed on everything in the firm, including uniforms (Bylinsky, 1987).

"Strategic" culture is the result of a functional focus and organizational traditions. Such a culture also conduces toward a market/customer orientation, but the values have been institutionalized. Thus, this culture should be relatively long-lived. "Chauvinistic" culture is produced by the synthesis of elitist focus and charismatic leadership. It is internally oriented and lacks duration. The "Exclusive" culture comes about through the fusion of an elitist focus and organizational traditions. Hence, while it is internally oriented, it enjoys longevity.

Just as organizations whose stock-in-trade is innovation need an enabling structure, so do they require a supportive culture. Ditto for organizations with competitive strategies, such as low cost. When one superimpose mission-level strategies, such as retrenchment or growth on top of competitive strategies, such as price and innovation, the synchronization process becomes even more challenging.

ALIGNMENT PRESCRIPTIONS FOR SOME COMMON STRATEGIES

Organizations in deep trouble may need a dose of transformational leadership, which includes four ingredients: 1) inspirational vision; 2) dynamic personality (charisma); 3) crisis situation; 4) and dramatic acts to bring about the transformation (Muczyk & Adler, 2002). Clearly, organizations in need of transformation require a vision, which can be defined as an inspired, long-run strategy that is not obvious to extant managers and executives until it is revealed by the transformational leader (Huffman, 2001). Had that not been the case, the organization would have resuscitated itself without the assistance of a transformational leader. Certainly, if an organization needs a transformational leader, it should get one. However, because of the daunting nature of organizational transformation, such leaders are uncommon.

When examined closely, however, the preponderance of successful leaders build incrementally over time rather than transforming organizations overnight. Lee Iacocca has at times been described as a transformational leader. But when one considers how long it took Lee Iacocca to resurrect Chrysler - with the appreciable assistance of the federal government at that - it would be more appropriate to describe him as an incremental leader. Moreover, organizations frequently find themselves in trouble because of poor execution, in which case the solution is improved execution and not a vision.

For the past quarter of a century or so, many outstanding leaders succeeded by focusing on the fundamentals of management. That is, they created lean and nimble organizations through redefining the role and size of staff departments, de-layering hierarchies, continually improving processes and practices through re-engineering, employing network organizations where appropriate, empowering employees, establishing a strong connection between performance and rewards, and placing customers first. It is likely that even better performance would result if executives and managers would properly align key organizational variables with their business/competitive strategies.

Retrenchment Situations

Facing reality. Most organizational members are unlikely to embrace decisions and goals if their naked self-interest is at odds with those decisions and goals. This reality was acknowledged most recently by Muczyk & Steel (1998), and in the past by Vroom-Jago (1988), Vroom-Yetton (1973), Fiedler (1967), and Tannenbaum & Schmidt, (1958). But transforming an organization is frequently accomplished through turnaround and retrenchment strategies, which, in turn, require doing things in different, unfamiliar, undesirable, and often painful ways. In other words, the decisions that need to be made and the goals that must be set, frequently run counter to employee self-interest - e.g., managers are replaced, employees are terminated, and many disruptions are created with respect to traditional policies and practices.

An extreme example is Phelps Dodge, best known as a copper producer. In order to survive, Phelps Dodge had to adopt draconian measures that can best be described as "slash-and-burn" tactics. The firm slashed its workforce 56%, closed inefficient smelters, obtained a 10% pay cut from its salaried workers, and broke all of its 12 unions by withstanding bitter, violent strikes that lasted in excess of two years and required intervention by the Arizona National Guard (Swasy, 1989). The "blitzkrieg" mentality necessary to drastically restructure a firm quickly simply cannot be produced by democratic and permissive practices.

Mintzberg (1984) recognized all along the need for autocratic leadership for retrenchment situations because this strategy usually necessitates forming new structures, dismissing some existing employees, hiring new people, and providing direction for a renewal process - all very difficult decisions indeed that can be made only by the top executive. Nevertheless, even though only the CEO can make timely decisions to downsize, it may still be advisable to seek inputs from subordinates at various stages about how best to downsize.

In addition, urgency precludes participative methods, which are inherently time- consuming. To make matters worse, managerial education, until recently, has neglected the whole topic of how to retreat effectively. Finally, the retrenchment strategy flies in the face of the "bigger is better" ethic that is firmly ingrained in the U.S. culture and, in turn, has convinced many managers that being rewarded on the basis of the size of their units and their budgets is the norm. Thus, only the leader can make these difficult and unpopular decisions under extreme time pressures.

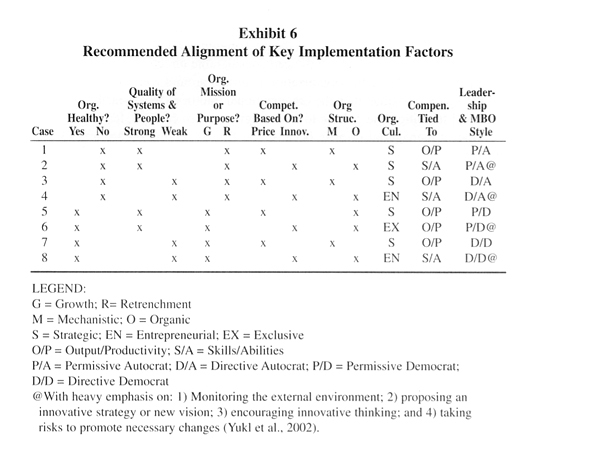

Case #1. In the unlikely situation where the organization is in trouble either financially or legally, while the quality of people and management systems is strong, and competition is on the basis of price; then the prevailing leadership style should be "permissive autocrat" coupled with "autocratic and permissive MBO." Such an organization is likely to retrench, at least for a while, until a better business model is adopted. Thus, autocratic leadership is recommended for the difficult decisions that need to be made, but the quality of the human capital and management systems merits permissive leadership. Furthermore, compensation should be tied either to output or productivity, while the culture, to the extent possible, should be "strategic." To the degree that a culture is dependent on organizational traditions rather than the current leader and is functionally oriented, the more reinforcing it is of long-run organizational success in most instances.

Case #2. In the other unusual scenario where the organization is in trouble, but the quality of people and management systems is strong, and the competitive strategy is one of relying on innovation, the leadership style should also be "permissive autocrat" in conjunction with "autocratic and permissive MBO." The difficult decisions still should be made by the leader. However, since the employees are capable and sound management systems are in place, the employees should be permitted considerable discretion in carrying out their assignments. The leadership style should also rely on leading change through: Monitoring the external environment; proposing an innovative strategy or new vision; encouraging innovative thinking; and taking risks to promote necessary changes. However, compensation should be tied to skills and abilities, with ample opportunity to establish an equity position, if possible. The culture should be strategic as well.

It is perfectly legitimate to ask: How can a firm be in trouble while the quality of its people is high and the management systems are up to the task? Never before has change marched more briskly than now, as the result of the globalization of the economy and unprecedented technological innovation. In such an environment, even talented persons can miss a sea change that could prove critical to the success of their organization. The classic case is NCR prior to the solid-state electronic revolution. NCR was basically an electromechanical firm with an enormous investment in highly skilled craftsmen and expensive machines. Obviously, this heavy investment, which the company was reluctant to abandon, created environmental blinders. The unwillingness to convert as quickly as possible to the emerging solid-state, point-of-sale terminals forced the company to write off $139 million of obsolete inventory and posed serious long-term problems for the company. Du Pont lost out to Celanese when bias-ply tire cords changed from Nylon to polyester. Michelin bested B.F. Goodrich in the marketplace when radial tires ousted bias-ply tires. A 'strategic" culture would have permitted these firms to make the necessary transition far better than the "exclusive" one that served to obscure the technological innovations that were obsolescing their products (Foster, 1985). Moreover, these companies would have been better served had their mangers devoted more time, energy, and money to leading change.

While it is important for the cost structure of a firm to shrink as the business level declines, it is even more so when competition is largely on price, since the profit margins in this situation are typically thin. For these companies, the long-run is the sum of all the short-runs because the company is producing the same or similar mix of products in a similar manner year after year. And this objective can be realized by creating a strong nexus between compensation and productivity or output. Moreover, support employees, such as equipment maintenance personnel, should have their compensation tied to the output of the work groups and/or individuals that they support. Part of the compensation of the supervisors should also be based on the output of their subordinates.

Furthermore, indirect compensation (fringe benefits) should contain only the basics, should be carefully monitored to make certain that it does not get out of line, and should be only as generous as is required to attract and retain the kinds of employees that are needed to accomplish the mission of the organization and to discourage unionization. After all, often it is the indirect compensation that is out of control, as opposed to direct compensation.

When the firm is pursuing an innovation strategy, basing remuneration on traditional, short-term performance indicators, would be counter-productive. Hence, making compensation a function of innovative behavior and proxies for innovation, such as skills, abilities, and appropriate experience, is likely to produce better results.

Case #3. If the organization is in trouble, the quality of people and management systems is weak, and the competitive strategy is based largely on price, then the leadership style is "directive autocrat" coupled with "autocratic and directive MBO;" until such time as the management systems are strengthened and the quality of personnel improved. Clearly, the leader should make the important decisions, set the salient goals, and follow up closely on both. Furthermore, compensation should be strongly connected to output and/or productivity. While perforce the culture may have to be "entrepreneurial" until the turnaround is accomplished, management should begin preparing the organization for a "strategic" culture in anticipation of a growth environment.

Case #4. If the organization is in trouble, the quality of people and management systems is weak, and the competitive strategy is predicated on innovation; then the "directive autocrat" leadership style should be reinforced with "autocratic and directive MBO." Under this scenario, the highest priority of top management is to improve the quality of the workforce, since it is difficult to pursue innovation unless appropriate personnel are in place. Consequently, a number of existing personnel will in all likelihood need replacing. There should be a strong nexus between compensation and skills and abilities, with ample opportunity for employees to acquire significant equity as an added inducement to align work behavior with competitive strategy. Finally, the culture may need to be "entrepreneurial," until such time as the organization is righted. Needless to say, leaders in such a situation have an obligation to lead change in a manner prescribed by Yukl, Gordon & Taber, 2002).

Autocratic leadership in combination with a compatible MBO program is recommended for Cases #3 & #4 for the same reasons it is recommended for Cases #1 & #2. However, the directive component is substituted for the permissive one in both leadership and MBO, since the quality of people and management systems is weak. Hence, the leader must follow up on the execution or implementation of decisions and the goal attainment process, since it is highly likely that the subordinates will need considerable direction and guidance on a frequent basis. Once the organization is turned around and remains successful for a period of time, then the organizational traditions that contribute to success will transition the culture to a "strategic" one. In case #4, leading change becomes a managerial priority because the firm is relying on an "innovation" strategy.

Growth Situations

Case #5. When the organization is doing well, the quality of people and management systems is strong, and the competitive strategy is based on price, then the appropriate leadership style is "permissive democrat" supported by a "democratic and permissive MBO." Rewards should be tied to output or productivity and an opportunity for acquiring some equity should be afforded. The most appropriate culture would be "strategic."

Case #6. In circumstances where the organization is doing well, the quality of people and management systems is strong, and innovation is the organization's selected strategy, then the recommended leadership style is "permissive democrat" buttressed by "democratic and permissive MBO." Compensation should be connected to skills, abilities, and specific innovative activities; and opportunities for accumulating significant equity positions should be provided. Such an organization would be well served by an "exclusive" culture.

Democratic and permissive leader behaviors and MBO practices are recommended for cases #5 and #6 because they embody the necessary conditions - quality people, sound management systems, and sustained success. For Case #6, this configuration needs to be pursued in concert with leading change.

Case #7. When the organization is doing well, the quality of people and management systems is weak, and the competitive strategy is largely a function of price, then the leadership style is "directive democrat" with augmented by "democratic and directive MBO." Remuneration should be joined to output or productivity, and the culture should be "strategic."

Case #8. If the organization is not in trouble, the quality of people and management systems leaves something to be desired, and innovation is the bread-and-butter of the organization, then the "directive democrat" leadership style complemented by "democratic and directive MBO" is appropriate. Rewards should be tied to skills and abilities, as well as to concrete innovative activity. Understandably, the culture should be "entrepreneurial," until the organizational members can either be developed or replaced. In addition, leading change is crucial. For a summary, see Exhibit 6.

Three Special Cases

Entrepreneur dominated. Small and, at times, medium-size companies often are dominated by the founder, who constitutes the glue that keeps the firm together and provides it direction. Such firms are seldom run by a "permissive democrat." In most instances, the best-case scenario is a "permissive autocrat." Moreover, these organizations are typically characterized by either "entrepreneurial" or "chauvinistic" cultures. Compensation strategies and core technology organizational structures, even in the founder-dominated companies, should be forged on the basis of the same criteria as in the first eight cases described above. In these organizations, and when appropriate, it is the founder who must lead change when appropriate.

However, not all start-up companies are led by "directive autocrats." Apple Computer Co., Tandem Computers, and People Express Airlines were founded by "permissive democrats." However, at a certain stage of their life cycle this leadership style became inappropriate, and each firm stumbled badly. Apple Computer brought in a new leader in time to regain its momentum. Jimmy Treybig became much more decisive and directive in time to save Tandem from disaster. But Don Burr refused to change his leadership style, and after accumulating heavy losses, the company was acquired by Texas Air.

Providers of critical services. Often, long-standing providers of critical services such as legal, medical, investment, accounting, and consulting are characterized by "exclusive" cultures, which ensue when the elitist value orientation of a chauvinistic culture survives its charismatic leader and becomes institutionalized. The name is derived from an elitist but traditional, club-like orientation. The leadership style and enabling practices, on the other hand, are a function of the same forces as in the aforementioned eight cases. Compensation practices in these organizations, on the other hand, are in part a function of the amount of business that the member (the senior ones are typically partners) brings into the organization. Furthermore, one of the important criteria for being accepted into partnership is evidence that one can bring new business into the firm. It appears that members of organizations characterized by exclusive cultures are more likely to believe in their own superiority, and that leads to a perception of immunity which, at times, encourages unnecessary risk taking.

Arthur Anderson was very successful for 81 years with an "exclusive" culture carried over from its founder. However, the desire for impressive growth in what had become a very competitive industry motivated many partners at Anderson to jettison its elitist values and cater to the wishes of a number of clients, who, in turn, were pressured to produce impressive earnings and growth, even if it meant employing questionable means. While the customer may always be right in many industries, such is not the case with respect to public accounting, law, and medicine. The rest is history.

Conglomerates. Conglomerates by definition are comprised of very different strategic business units. Consequently, it is necessary to align the salient organizational variables identified in this paper with the respective business/competitive strategies for each strategic business unit in order to realize the maximum capability of each competitive strategy.

SOME EXAMPLE OF HAZARDS ASSOCIATED WITH MISMATCHES

W. Michael Blumenthal, erstwhile CEO of Unisys, serves as an example of the hazards associated with a misalignment between critical leader behaviors and business strategy - turning around a troubled organization. While numerous Unisys executives conceded that a directive leadership style was called for because the organization was in need of a strong hand running day-to-day operations, Mr. Blumenthal frequently avoided day-to-day decisions, ignored the chain-of-command, and spent considerable time on outside interests. Timely decisions were crucial, yet the committee of ten rather autonomous executives ensured a slow decision-making process. The result of the inappropriate leadership style was: Loss of momentum, departure of key executives, delays in the introduction of new products, burdensome inventories, and losses rather than profits (Carroll, 1989). Northwest Airlines (NWA) serves as an example of alignment problems that ensue when two organizations with very different cultures merge. Historically, Northwest Airlines had a "hard-line" culture and a "directive autocrat" leadership style (Gibson, 1989a & Rose, 1989). Such a combination served Northwest well when it grew through a low cost competitive strategy, especially when acute competition resulting from deregulation was buffeting most major airlines. However, as Northwest matured and acquired Republic Airlines, a firm with a different culture and leadership style, that type culture and leadership style proved to be more of a liability than an asset. NWA employees were now ready for more participation and less direction. Furthermore, combining two different workforces at best is a difficult task, requiring the ideas, cooperation, and trust of everyone involved. A "directive autocrat" leadership style, however, tends to stile innovation and create resentment, if not accompanied by a heavy dose of consideration. In the case of NWA, the problems exacerbated by the mismatch made the firm a candidate for takeover.

CONCLUSION

Simon's (1957) concept of "bounded rationality," by focusing on imperfect information as the primary reason why managers "satisfice" rather than "optimize," sheds considerable light on why managerial decisions do not necessarily conform to the predictions of the rational economic model. In like manner, the implementation problems caused largely by the misalignment of critical management factors with chosen business/competitive strategies prevent the full realization of the fruits that selected business strategies have to offer. Toward that end an attempt was made to identify the important variables that need to be aligned with specific business/competitive strategies in order to fashion coherent implementation guidelines that would enhance the likelihood of success. Enlightened by the literature - academic and practitioner alike, including case studies - the author selected leader behaviors, salient management practices (management by objectives and compensation practices), organizational structure, and organizational culture. Others, have focused on such personality characteristics as risk- taking propensity and on specific functional skills. The aforementioned variables were then properly aligned with four retrenchment (two competing on price and two on innovation), situations and four growth (two competing on price and two on innovation) scenarios. Three special cases (entrepreneur dominated firms, providers of critical services, and conglomerates) were also discussed. It is unlikely that much harm results from the simplification of the business/competitive strategy schemes that have been chosen. In any case, more fine-tuning at this stage is unsupportable. While this is not the last word on alignment, it is an invitation to others to complete the process. In the meantime, it is anticipated that this effort makes it easier for executives and managers to forge effective implementation processes to accompany their strategic choices.

ENDNOTES

1. The fully elaborated form of Glueck's model includes: Growth/invest; turnaround/restructure; retrench/harvest; and stabilize/maintain. In the case of a diversified organization, the corporate resource allocation strategy is reflected in the business mission.

Return to Article

2. Porter's complete schema includes three generic competitive strategies, which are: Cost leadership, differentiation, and focus.

Return to Article

3. Hooijberg & Petrock (1993) devised a two-by-two matrix along the dimension of formal control orientation and forms of attention that corresponds to the Reimann & Wiener (1988) model, and could be used a well. Their four culture types are: Clan, Entrepreneurial, Bureaucratic, and Market.

Return to Article

REFERENCES

Ansoff, H. I. (1988). The New Corporate Strategy, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Arthur, J. B. (1994). Effects of human resource systems on manufacturing performance and turnover, Academy of Management Journal, 37, 670-687.

Baird, L. & Meshoulam, I. (1988). Managing two fits of strategic human resource management, Academy of Management Review, 13, 116-128.

Bevin, A. 1993. How Generals Win, New York: Norton.

Burns, T. & Stalker, G. M. (1961). The Management of Innovation, London, England: Associated Book Publishers.

Bylinsky, G. (1987). Japan's robot king wins again, Fortune, May 25, 53-58.

Cameron, K. S. & Quinn, R. E. (1999). Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture, Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Carroll, P. B. (1989). The data game: Blumenthal strives to make computer firm a leader, takes big gamble on Unix, The Wall Street Journal, March 31, A1.

Chandler, Jr., A. D. (1962). Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Collins, J. (2001). Good to Great, New York: Harper Business.

Cutcher-Gershenfeld, J. (1991). The impact on economic performance of a transformation in industrial relations, Industrial and labor Relations Review, 44, 241-260.

Detroit downer: U.S. auto makers predict more sales lost to Japan. (1991). The Wall Street Journal, April 4, 1.

Dunham, R. B. (1989). Management, Glenville, Illinois: Scott Foresman & Co., 385.

Erez, M. (1977). Feedback: A necessary condition for the goal setting-performance relationship, Journal of Applied Psychology, 62, 624-627.

Fiedler, F. E. (1967). A theory of Leadership Effectiveness, New York: Mc Graw-Hill.

Floyd, S. W. & Wooldridge, B. (1992). Managing strategic consensus: The foundation of effective implementation, Academy of Management Executive, 6, 27- 39.

Foster, R. N. (1985). To exploit technology know when to junk the old, in The Wall Street Journal on Management, edited by David Asman and Adam Meyerson, Homewood, ILL.: Dow Jones - Irwin, 64-67.

Gibson, R. B. (1989a). Flying solo: The autocratic style of northwest's CEO complicates defense, The Wall Street Journal, March 30, A1.

Gibson, R. B. (1989b). Personal chemistry abruptly ended rise of Kellogg president, The Wall Street Journal, November 28, 1.

Gibson, J. W. & Tesone, D. V. (2001). Management fads: Emergence, evolution, and implications for managers, Academy of Management Executive, 15, 122-133.

Glueck, W. E. (1976). Business Policy: Strategy Formulation and Management Action, 2nd ed., New York: McGraw-Hill, 120-147.

Greenberg, J. & Baron, R. A. (1993). Behavior in Organizations 4th ed., Needham, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Gupta, A. K. & Govindarajan, V. (1984). Business unit strategy, managerial characteristics, and business unit effectiveness at strategy implementation, Academy of Management Journal, 9, 25-41.

Herbert, T. T. & Deresky, H. (1987). Should general managers match their business strategies, Organizational Dynamics, Winter, 40-41.

Hofer, C. W. & Schendel, D. (1978). Strategy Formulation: Analytical Concepts, St. Paul MN: West Publishing Co..

Hooijberg, R. & Petrock, F. (1993). On cultural change: Using the competing values framework to help leaders execute a transformational strategy, Human Resource Management, 32, 29-50.

Huffman, B. (2001). What makes a strategy brilliant? Business Horizons, July, 1-15.

Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance," Academy of Management Journal, 38, 635-672.

Huselid, M. A. & Becker, B. E. (1996). Methodological issues in cross-sectional and panel estimates of the human resource-firm performance link, Industrial Relations, 35, 400-422.

Huselid, M. A., Jackson, S. E. & Schuler, R. S. (1997). Technical and strategic human resource management effectiveness as determinants of firm performance, Academy of Management Journal, 40, 171-188.

Kerr, S. (1975). On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B, Academy of Management Journal, 18, 769-783.

Kerr, J. & Slocum, J. W. (1987). Managing corporate culture through reward systems, The Academy of Management Executive, 1, 99-107.

Lawler, E. E. (1984). The strategic design of reward systems, in Readings in Personnel and Human Resource Management, 2nd ed., edited by Randall S. Schuler and Stuart A. Youngblood, St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co., 253-269.

Locke, E. A., Feren, D. B., McCaleb, V. M., Shaw, K. N., and Denny, A. T. (1980). The relative effectiveness of four methods of motivating employee performance, in Changes in Working Life, by Duncan, K. D., Grunberg, M. M., and Wallis, D., John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 363-388.

MacDuffie, J. P. (1995). Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance: Organizational logic and flexible production systems in the world auto industry, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 48, 197-221.

Miles, R. E. & Snow, C. C. (1978). Organizational Strategy, Structure, and Process, New York: Mc Graw-Hill.

Mintzberg, H. (1973). The Nature of Managerial Work, New York: Harper & Row.

Mintzberg, H. (1984). Power and organizational life cycles, Academy of Management Review, 9, 207-224.

Muczyk, J. P. & Adler, T. (2002). An attempt at a consentience regarding formal leadership, Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 9, 2-17.

Muczyk, J. P. & Gable, M. (1987). Managing sales performance through a comprehensive performance appraisal system, Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, May 1987, 41-52.

Muczyk, J. P. & Steel, R. P. (1998). Leadership style and the turnaround executive, Business Horizons, March-April, 39-46.

Muczyk, J. P. & Reimann, B. C. (1989). MBO as a complement to effective leadership, Academy of Management Executive, 3, 131-138.

Muczyk, J. P. (1988). The strategic role of compensation, Human Resource Planning, 11, 225-239.

Muczyk, J. P. & Reimann, B. C. (1987). The case for directive leadership, The Academy of Management Executive, 1, 301-311.

Nohria, N., Joyce, W. & Roberson, B. (2003). What really works? Harvard Business Review, July, 43-52.

Porter, M. (1985). Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, New York: The Free Press.

Porter, M. (1987). From competitive advantage to corporate strategy, Harvard Business Review, May-June, 43-59.

Reimann, B. C. & Wiener, Y. (1988). Corporate culture: Avoiding the elitist trap, Business Horizons, 31, 36-44.

Rodgers, R. & Hunter, J. E. (1991). Impact of management by objectives on organizational productivity, Journal of Applied Psychology Monograph, 76, 322-336.

Rose, R. L. (1989). NWA Could face at least 3 suitors, sources indicate, The Wall Street Journal, March 30, A9.

Ross, J. A. (2002). A perfect fit: Aligning organization and strategy, HBS Working Knowledge, April 26, 1-3.

Schuler, R. & Jackson, S. E. (2001). Seeking an edge in mergers and acquisitions, Financial Times, October 22.

Schuler, R. & Jackson, S. E. (1987). Linking competitive strategies with human resource management practices, Academy of Management Executive, 1, 207.

Schwartz, H. & Davis, S. M. (1981). Matching corporate culture and business strategy, Organizational Dynamics, Summer, 30-48.

Simon, H. (1957). Administrative behavior: A study of decision making processes, in Administrative Organization, 2nd ed., New York: Macmillan.

Swasy, A. (1989). Long road back: How Phelps Dodge struggled to survive and prospered again, The Wall Street Journal, November 24, 1.

Tannenbaum, R. & Schmidt, W. H. (1958). How to choose a leadership pattern, Harvard Business Review, March-April, 95-101.

Venkatraman, N. (1989). The concept of fit in strategy research: Toward verbal and statistical correspondence, Academy of Management Review, 14, 423-444.

Woodward, J. (1965). Industrial Organization: Theory and Practice, London: Oxford Press.

Wooldridge, B. & Floyd, S. W. (1990). The strategy process, middle management involvement, and organizational performance, Strategic Management Journal, 11, 231-241.

Vroom, V. H. & Jago, A. G. (1988). The New Leadership: Managing Participation in Organizations, Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall.

Vroom, V. H. & Yetton, P. W. (1973). Leadership and Decision Making, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Yukl, G., Gordon, A. & Taber, T. (2002). A hierarchical taxonomy of leadership behavior: Integrating a half century of behavior research, Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9, 15-32.