Impact of Governance, Legal System and Economic Freedom on Foreign Investment in the MENA Region

Nada KobeissiLong Island University, U.S.A.

Abstract

While there is substantial literature examining the flow of foreign investments into various regions of the world, there is still lack of research focus on foreign investment activities in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). One objective of this paper is to remedy this neglect and extend previous empirical work by focusing on foreign investments in that region. The second objective is to focus on non-traditional determinants that have tended to be overlooked or underestimated in previous research. The paper will focus on factors such as governance, legal environment, and economic freedom and examine their impact on foreign investment activities in the MENA region.Introduction

1 The objective of this paper is to focus on two significant research questions that have not yet been thoroughly examined in the literature on foreign investment. Over the last 15 years, the flow of foreign investment around the world has been growing spectacularly. While international trade has doubled, the flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) has increased by a factor of 10 (Levy-Yeyati et.al, 2003). Within the various regional growth of foreign investment, FDI flowing to developing countries has accounted for about 40 per cent of global FDI (Erdal & Tatoglu, 2002). Although there is substantial literature examining the flow of foreign investments into various regions of the world, unfortunately the majority of this research has focused on U.S. foreign investment activities in Europe, NAFTA Signatory nations, Asia and Pacific Rim nations, and economies in transition (Kingsley & Crumbley, 1997). There is a paucity of information and studies relating to joint ventures and foreign investment activities in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The first objective of this paper is to remedy this neglect and extend previous empirical work by focusing on foreign investment in the MENA region.

2 When looking at foreign investment data within the MENA region, one can't help but notice the wide variability in the flow of foreign investment and joint venture activities, and wonder why some countries are more attractive to foreign investments than others. In trying to determine some of the factors that impact foreign investment flow, it is important to distinguish between three categories of foreign investment, these are: 1) market seeking; 2) resource seeking; and 3) efficiency seeking investments (Dunning, 1993). A 1998 UNCTAD report argued that globalization has led to a reconfiguration of the ways in which multinationals pursue these various types of foreign investments, and changed the motives for and the determinants of FDI (Dunning, 1999). For example, in recent years, foreign investment in developing countries has shifted from market and resource seeking investments, to more efficiency seeking investments (Dunning, 2002). This has prompted some to argue that the relative importance of some of the traditional market related factors (relative wage costs, infrastructure, macroeconomic policy) no longer hold (Loree and Guisinger 1995) and to suggest that less traditional determinants have become more important (Noorbakhsh, Paloni and Youssef 2001; Addison and Heshmati, 2003; Becchetti and Hasan, 2004). Furthermore, given that in recent years, the region is witnessing a new era in privatization, bank regulation and market-oriented financial institutions (Omran, 2004), the need to examine the role of alternative determinants is even more relevant.

3 The majority of the countries in that region are neither big enough to attract a significant number of market seeking foreign investment, nor resource rich enough to attract resource seeking foreign investment. Therefore, in analyzing foreign investment in the MENA region the second objective of this paper is to focus on some of the non-traditional factors that have tended to be overlooked or underestimated in previous research on foreign investment. In light of this focus, the paper will thus consider factors such as governance, legal environment, and economic freedom and examine their impact on foreign investment in the MENA region.

Hypotheses

Foreign Investment and the MENA Region (top)

4 Foreign investment has numerous effects on the economy of the recipient country. It influences the labor market, income, prices, export and import (Erdal and Tatoglu. 2002). It is an important vehicle for the transfer of technology and a positive contributor to economic growth (Lim, 2001). Unfortunately however, the recent unprecedented growth in foreign investment activities has largely bypasses the Arab world (UNCTAD, 1999). Compared with other developing countries, the capital inflow in the Arab world has remained constant at about $10 billion in the last 2 decades, whereas it has increased four times to reach $300 billion in other developing countries, mainly in East Asia, Latin America and increasingly in Central Europe. Recent analysis revealed that the Arab world received on average 1% of global FDI in the 1990s compared to 2% of their share in world GDP. Most of these FDIs were concentrated in six Arab countries, namely Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia and were mostly undertaken in the oil, petrochemical, and manufacturing industries, especially textiles, metals and minerals (Sadik and Bolbol, 2001).

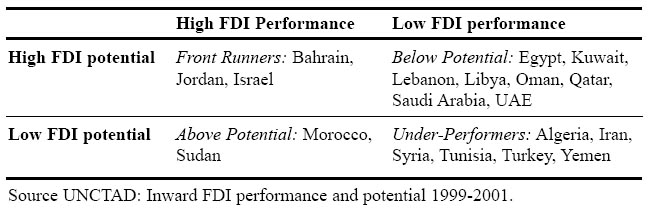

5 Comparing inward FDI performance with potential for the same region produces a matrix representing front runners, below potential, above potential and under performers respectively:

6 Further examination of some of the countries in this matrix reveals some interesting information. For example, although it is the largest economy in Eastern Europe, the European Union's sixth biggest trading partner, and the world's 7th largest emerging economy, Turkey is an under-performer. FDI flow into Turkey is only a fraction of the level of FDI attracted to countries of comparable size and development like Argentina and Mexico, and only one-quarter of the level of FDI attracted into Poland (Loewendahl, and Ertugal-Loewendahl, 2000). On the other hand, a significantly smaller country, Bahrain has managed to be a front runner. The country has been able to attract foreign investment through significant incentives such as labor subsidies, electricity and land rental rebates, 100% rebate on customs duties for major equipment/raw materials, export credit facilities and tariff protection. Many investors cited the country's tax structure as their key motivation to invest. Bahrain imposes virtually no personal tax, no restriction on capital or profit repatriation and most significantly no corporate taxation. (Gilmore, et al. 2003).

7 It is important to note that the recent shift from markets and resources seeking investments, toward more of an efficiency seeking investment could if properly exploited be advantageous to the MENA countries due to their relatively small market sizes and limited natural resources. The main objective of market-seeking investment is to meet demand in the domestic market. In resource-seeking investment, the objective is to make use of the host country resources to produce goods for sale outside the local market (Asiedu, 2002). Demands and resources however, are less relevant in efficiency seeking investment, where the emphasis is more on the efficiency with which foreign investors can operate, network, sell and export their products to other countries. Therefore, in striving to attract foreign investment, the most viable among the alternatives for the MENA region, would be a focus on efficiency seeking investors. Such notion reinforces the importance of examining efficiency enhancing elements such as governance, the legal system and economic freedom and their impact on foreign investment.

Governance (top)

8 Globerman and Shapiro (2002) suggested that governance represents the public institutions and policies created by governments as a framework for economic and social relations. Kaufmann et. al (2000) defined governance as the traditions and institutions that determine how authority is exercised in a particular country. Good governance infrastructure is a complex, multifaceted concept generally manifested in a country's accountability, government effectiveness, regulatory burden, political stability, rule of law and control of corruption (Kaufmann, et. al, 1999a, and 1999b). It contributes to the effective implementation of economic policies and helps to determine whether or not there is a sound, attractive business environment for investment. It provides the mechanism to minimize policy distortions, reduces information asymmetries and uncertainties, increases the flexibility of a country to respond to economic shocks and makes it easier to start, run and expand new businesses (World Bank, 2003)

9 Globerman and Shapiro (2003) found governance infrastructure to be an important direct determinant of location choice by U.S. investors. The presence or lack of the various elements of governance has the potential to effect a host country's attractiveness to foreign investment. One particular element that has been widely related to governance and associated with foreign investment is transparency. Lack of transparency or opacity - a term largely associated with bribery and corruption, is a particular and common sign of lack of good governance (World Bank, 2003). Davis and Ruhe (2003) found a highly significant relationship between corruption and foreign investment. Thesedays, prospective investors are paying attention to the realities of corruption in some foreign countries (Conklin, 2002). Corruption has been a significant obstacle for U.S. investors due to the United States' Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which has outlawed foreign bribery. In theory a firm will be less likely to enter a non-transparent country because of the increased risks, uncertainty and costs of doing business. On the other hand, a country that takes steps to increase the degree of transparency and reduce corruption could expect a significant increase in the level of foreign investment. On average, a country could expect a 40% increase in FDI from a one point increase in their transparency ranking (Drabek and Payne, 2001).

10 Beyond U.S. investors, Globerman and Shapiro (2002) also found governance infrastructure to be an important determinant of

both FDI inflows and outflows in most countries; however they found that FDI will be more strongly affected by improvements

in governance in developing countries than in developed countries. The returns to investments in good governance were greater

for developing and transition economies. Unfortunately, the quality of governance in the MENA region is very poor. When compared

with countries that have similar incomes and characteristics the main competitors in the global marketplace the MENA region

ranks at the bottom of the index of overall governance quality (World Bank, 2003). Consequently, in 1999-2001, 6 out of the

bottom 10 countries in inward FDI performance from various regions in the world were from the MENA region, namely Iran, Kuwait,

Libya, Saudi Arabia, UAE and Yemen. The remaining countries were Malawi, Indonesia, Gabon and Suriname (UNCTAD, 2002). Looking

back at the above matrix, these 6 MENA countries were categorized as either below potential or under performers in terms of

their performance in foreign investment.

Hypothesis 1: There is a positive relationship between the level of governance and the flow of foreign investment in MENA

countries.

Legal System (top)

11 Several papers have argued that the legal system can play a key role in attracting foreign investments or encouraging financial and economic development (LaPorta et. al., 1998a, 1998b; Globerman and Shapiro, 2003; Chan-Lee and Ahn, 2001). Generally, the legal system around the world can be classified according to whether its origins are primarily in pure common law based on the English system, or pure civil law based on the Roman system - with specific categories in French, Spanish, German, Scandinavian, or Socialist. Other classifications include countries with customary or religious laws (Muslim, Talmudic etc.), or a mixture of two or more systems (LaPorta et.al, 1998b; Globerman and Shapiro, 2003; Chan-Lee and Ahn, 2001).

12 A legal environment that protects investors can be significant in investors' decision making (LaPorta, et. al, 1999). For example, in Common Law countries managers have less flexibility in exercising discretion over reported earnings. Hence, the relation between reported earnings in financial statements and the "economic value" of the firm is expected to be stronger. Such factors might persuade joint venture investors to favour Common Law countries, as they can feel more secured about their investments. This is not true in Code Law (another classification based on an all-inclusive system of written rules) in countries where the law allows more latitude in accounting practices to smooth earning. More latitude implies that the financial figures in Code Law countries are to be perceived as less of a reflection of economic reality (Guenther & Young, 2000).

13 Countries whose commercial legal systems are rooted in English Common Law have less market regulations and are better at protecting shareholders and creditors, and at preserving property rights (LaPorta, et al., 1998a, 1999, 2001; Djankov et al., 2002). They also have low cost of contracting because the legal system interprets the spirit rather than the letter of the contract (Lang and So, 2002). Common Law facilitates the development of capital markets and investment opportunities and as a result attracts more foreign investment (Globerman and Shapiro, 2003, Reese and Weisbach, 2002). An anasysis of the relationship between U.S. foreign direct investment and legal systems has clearly indicated that countries whose legal systems are rooted in English Common Law are more likely to be recipients of U.S. FDI flows (Globerman and Shapiro, 2003). According to the authors, Civil law regimes are expected to attract less foreign investment because they are likely to be associated with higher durations of judicial proceedings, more corruption, less honesty and fairness and inferior access to justice.

14 Within the MENA region, the legal system is rooted in various origins. If we are to spread the countries across a spectrum,

at one end would be situated those countries that observe the sharia, and at the other end, would be those whose legal system

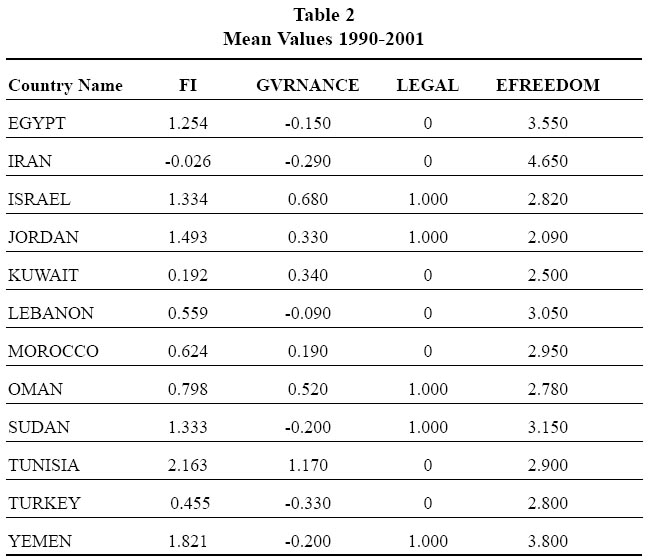

have developed far from it (Shaaban, 1999). When it comes to commercial transactions it is possible to group MENA countries

into 3 categories. First are those that followed the Western system such as Lebanon, Syria and Egypt. Second are those that

have codified their laws but drew mostly from sharia such as Saudi Arabia, Oman and Yemen. Third are countries that went both

ways. They westernised their commercial laws but still draw from Islamic law in such areas as contracts. These countries include

Iraq, Jordan and Libya (Shaaban, 1999). To date there has been no academic research examining the impact of the legal system

on foreign investment in the MENA region, however, Globerman and Shapiro (2003) suggested that countries that adopt a legal

system that mixes common law with customary or religious law are less likely to receive FDI.

Hypothesis 2: There is a positive relationship between countries whose legal systems are rooted in Common Law and the level

of foreign investment in MENA countries.

Economic Freedom (top)

15 Beyond governance and legal systems, another element that could have an impact on foreign investment is economic freedom, especially with regards to aspects of a country's trade policy, its banking and finance services and its property right protection (Drabek and Payne, 2001; Globerman and Shapiro, 2003). Gwartney, et.al.(2003) suggested that the key ingredients to economic freedom include freedom to compete, voluntary exchange, and protection of person and property. O'Doriscoll et.al. (2001: 43) defined economic freedom as "the absence of government coercion or constraint on the production, distribution or consumption of goods and services beyond the extent necessary for citizens to protect and maintain liberty itself."

16 Open trade and investment regimes are particularly powerful instruments to attract investments in general and foreign investments in particular (Drabek and Payne, 2001). There is strong empirical evidence for positive contribution of trade liberalization on FDI inflows (Selowsky and Martin, 1997). Countries open to international trade provide a good platform for global business operations and reflect their competitiveness (Habib and Zurawicki, 2002). Unfortunately however, responding to protectionist and special interest politics, virtually all countries adopt trade barriers of various types (Gwartney et.al., 2003). Trade barriers lower productive efficiency by reducing competition and raising transaction costs (Harms and Ursprung, 2002). The extent of the host country's tariff and non tariff barriers, import and export limitations, and licensing requirements can have a direct bearing on foreign actors' ability to pursue economic goals and present roadblocks that limit international trade and restrict the flow of foreign investment (Drabek and Payne, 2001).

17 In the area of banking and finance, heavy bank regulations and the absence of an independent oversight of financial services, lack of a safe and sound financial sector, and inadequate financial systems that meet basic fiduciary responsibilities can restrict economic freedom (O'Doriscoll et.al, 2001). This, in addition to weak enforcement of contract and protection against fraud can interfere with the market provision of financial services and create disincentive for foreign actors to invest in the host country (Beck, Levin and Loayza, 2000).

18 Finally, economic freedom would be meaningless if individuals do not have secure rights to property. Poor protection of property rights is sure to deter investment and undermine the operation of a market-exchange system (Gwartney, et.al., 2003). It determines the legal rights of foreign firms and limitation on foreign ownership (De Mello, 1997); Protecting privately held assets from arbitrary direct or indirect appropriation encourage sunk cost investments by multinational corporations (Globerman and Shapiro, 2003). The protection of property rights is vital for firms to pursue new investments and ensure that they will see profit from their endeavors. Without this profit incentive there is little motivation to take risks and invest (Drabek and Payne, 2001).

19 Within MENA countries, enhancing economic freedom in terms of trade, the financial sector and property rights is of absolute importance if the region is to attract more foreign investments. According to a World Bank report (World Bank, 2003), foreign investment could be five to six times what they are today, if exports other than oil were higher and were in better investment climates. Inefficient and costly services provided mostly by the public sector, raise the cost of MENA merchandise exports and limit attractiveness to investment (World Bank, 2003). The financial sector is controlled by state owned banks which dominate banking activities (up to 95% of assets in several countries in the MENA region) resulting in poor services, high costs, and weak financing of new investments and trade (World Bank, 2003). Due to a complete lack of faith in its domestic economic infrastructure, the Middle East holds the largest share of wealth abroad in the world, with $350 billion currently collecting interest abroad, rather than in local financial institutions1.

20 Finally, property rights, although protected by the constitution in many countries, face many delays and obstacles from the

legal system. Dispute resolution can be difficult and uncertain, enforcement of judgments is not always easy, and judicial

proceedings could go on for several years. In Egypt, it can take 6 years for a commercial case to be decided and with appeals

could be extended beyond 15. In Qatar, the legal system is biased in favor of citizens and the government. In Saudi Arabia,

The U.S. Department of State reported that in several cases disputes have caused serious problems for foreign investors by

preventing their departure from the country, blocking their access to exit visas, or imposing restraint of personal property

pending the adjudication of a commercial dispute. In the end, trade policies that impose inefficiencies and foreign investment

restrictions, heavy bank regulation, in addition to expropriation of property, are signs of weak economic freedom and can

be an obstacle to foreign investment as it can be indicative of the various ways in which a government may take away potential

profits (Conklin, 2002).

Hypothesis 3. There is a positive relationship between economic freedom and the level of foreign investment in the MENA countries.

Methods

Model Specification (top)

21 Foreign Investment = Constant + ß 1 Governance + ß 2 . Legal System + ß 3 . -1Economic Freedom + [ß -14-11 -1 Control Variables] + [ß 12-1 Time Trend or ß -112-23 -1 Year Dummies] + Error Term That is:

22 Foreign Investment [( Joint Venture, JV + Foreign Direct Investment, FDI,) /Gross Domestic Product, GDP] = Constant + ß 1 Governance + ß 2 Legal System + ß 3 Economic Freedom + [ß 4 Inflation Level + ß 5 Wage Rate + ß 6 Technological Infrastructure + ß 7 Economic Growth + ß 8 Education Level + ß 9 Composite Risk + ß 10 Market Size (Population)+ ß 11 Fuel Economy Dummy] + ß 12 Time Trend (OR ß 12-23 Year Dummies) + Error Term

Sample and Data (top)

23 The paper analyzed both joint venture and FDI activities in the MENA region using data from 1990-2001. The idea was to start with a sample representing of all the countries in the MENA region. However, I had to eliminate some of the countries due to lack of consistent data for all of the variables over the 12 year period. In the end, the sample size consisted of the following 12 countries: Egypt, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Sudan, Tunisia, Turkey, and Yemen.

Measures (top)

Dependent Variable

24 The dependent variable foreign investment is a combination of total foreign inflow of funds in a given country in a given year as a percentage of GDP of respective countries. The inflow of funds is composed of two components: total joint venture (JV) related inflow of funds and the foreign direct investment (FDI) associated with each of the sample countries. The traditional literature uses FDI using the UNCTAD (1998) or World Bank Development Indicators which do not explicitly include the joint venture activities undertaken by each of these countries. The JV data was collected from the "Joint Venture" component of the Security Data Corporations (SDC) database of the Thompson Financial Corporation. It is an aggregate dollar amount of the total joint venture deals signed by individuals and companies by each of the sample countries with other foreign companies and nationals. The other component of the dependent variable, the net flow of net Foreign Direct Investment, was collected from the World Bank's Development Indicators (data was also confirmed by checking the UNCTAD (1998) source on FDI).2 I have estimated alternative regressions using JV and FDI as dependent variables separately and given that the results of alternative definitions do not change the economic or statistical significance of our three focus variables, I only report the estimations based on the broader definition of Foreign Investment, i.e. the combination of JV+FDI.

Independent Variables

1Governance25 The governance variable is based on an index developed by Kaufmann, Kraay and Zoido-Lobaton (1999a, 1999b, 2003). The index is an aggregate of the following 6 constructs: rule of law, corruption, voice and accountability, government effectiveness, political instability and violence, and regulatory burden. The governance score lies between -2.5 and 2.5, with higher scores corresponding to better governance.

2Legal System26 The legal system data was collected from different published sources on the legal practices followed in each of the sample countries. For example, Egypt follows a common law structure relative to Lebanon, which follows French or civil codes of law. Two papers have used these scores extensively (LaPorta, et. al, 1998b, 1999). I used a dummy variable where common law countries are considered 1 and others considered 0.

3Economic Freedom27 The data for economic freedom was based on the economic freedom indicators developed by the Wall Street Journal and Heritage Foundation in the U.S. I used an index developed from an average aggregate combination of each country's trade policy (openness to export and import); banking and finance (relative openness and deregulatory environment in the banking and financial sectors, the extent of government intervention in monetary policy, and the economic and financial policy making issues of the country); and finally the relative score given to a country based on its ranking of property rights (degree to which private property rights are protected, and the degree to which the government enforces laws that protect private property). The scale on the index of economic freedom runs from 1 to 5. A score of 1 on the index signifies an institutional or consistent set of policies that are most conducive to economic freedom, while a score of 5 signifies a set of policies that are least conducive (for more details see O'Doriscoll et al., 2001 and different issues of Index of Economic Freedom).

Control Variables

28 Among the control variables, Inflation level Consumer Price Index, Wage Rate - the wages and salaries as a percent of total national expenditure, Economic Growth- Annual GDP growth are taken from the IMF's International Financial Statistics, Technological Infrastructure -telephone line per 10,000 population, Education Level percentage of children enrolled in secondary school, are taken from the World Bank's Development Indicators, Economic Growth- Annual GDP growth, Composite Risk, a variable with Combination of Economic, Financial and Political Risk are taken from the PRS Group reports on Composite Risk. The dummy variable Fuel, takes a value of l if the sample country is an oil producing country (Iran, Kuwait, Oman, and Yemen) and a value of zero for other sample countries. I also used a time trend variable to see whether there is a trend in FDI over the years in addition to a more direct measure of time fixed effect by using time dummies for sample years.

Analysis (top)

29 I used Ordinary least square (OLS) regressions to estimate the relative importance of the independent variables in the model. Data were pooled from 12 years of data to increase the degrees of freedom. All the regressions reported in the various tables were computed using White's (1980) heteroskedastici-ty-adjusted t-statistics which adjusts for any bias due to heteroskedasticity. In total I had a total of 144 observations.3

Results

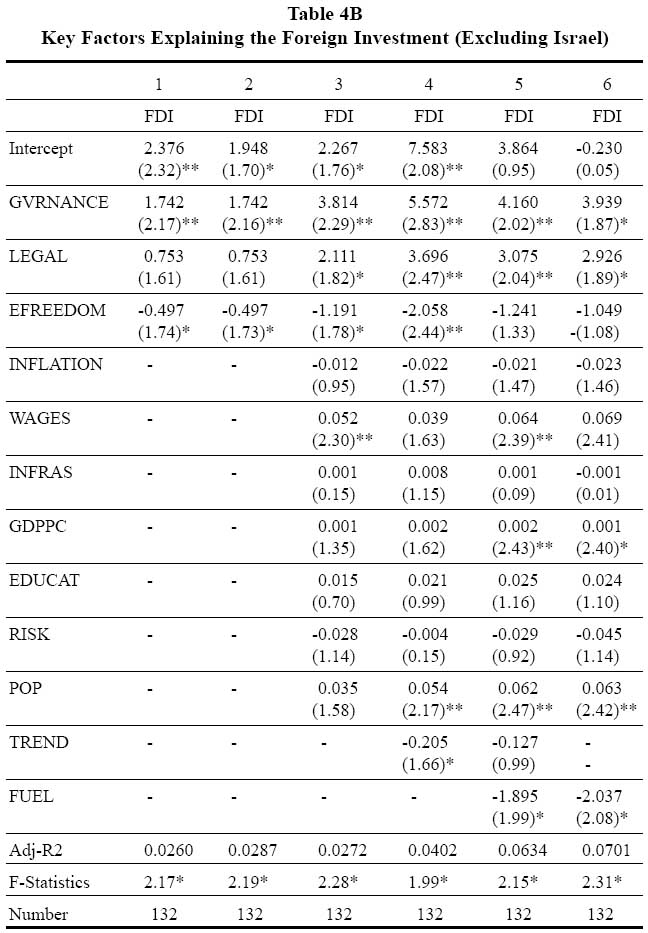

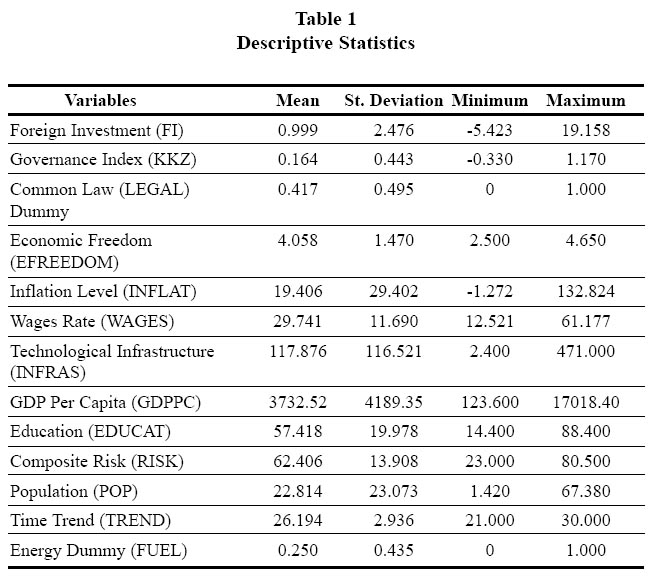

30 Table 1 represents overall descriptive statistics of the sample observations. In summary, the statistics shows that my sample consists of a wide range of experiences ideal for a robust empirical analysis. For example, the foreign investment to GDP ratio varied from a significant positive number of a net outflow to a negative number in a given sample year. Almost 40% of the countries are mostly rooted in a common law legal system. About 25% of the observations are from countries with energy-based economies. Table 2 provides further details of key variables by individual countries establishing additional support for the varied experiences and environments existing among the sample observations. Tunisia has the highest governance score of 1.17 while Turkey has the lowest score of -0.33. With regards to economic freedom, Iran is the country with the lowest economic freedom with a score of 4.65 (on a scale of 1 to 5. Note that the higher the score the less the economic freedom), while Jordan is the highest with a score of 2.09.

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 3

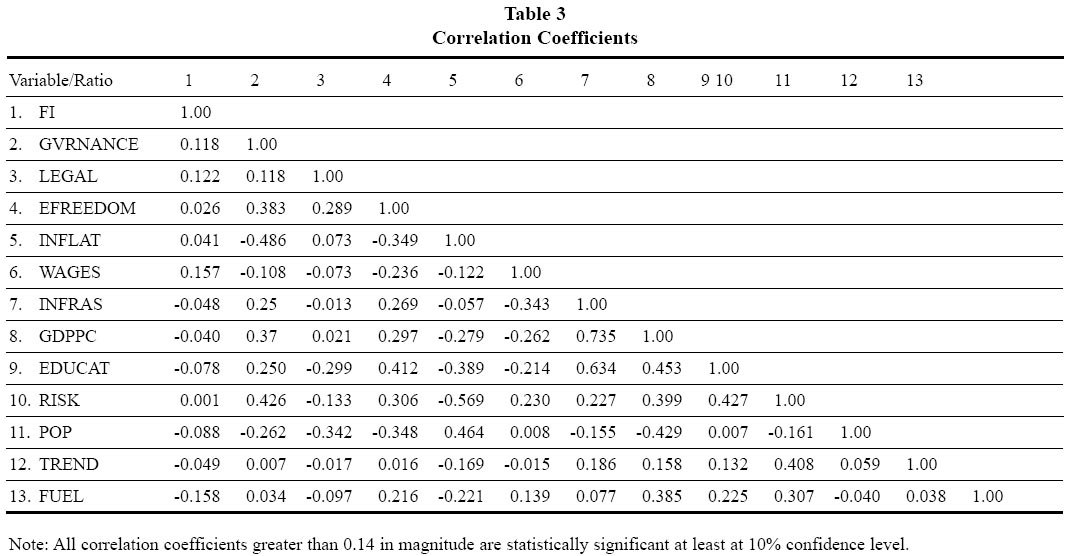

31 Table 3 provides a correlation coefficient of all variables used in the analysis. Except in few specific cases, e.g. per capita GDP (GDPPC) and Technological Infrastructure (INFRA) (0.735); education (EDUCAT) and Technological Infrastructure (0.634); and finally inflation (INFLAT) and composite risk (RISK) (0.569), the correlations coefficients do not show any systematic bias or problems. To check for the robustness of the result, I re-estimated the basic model by deleting variables that are highly correlated. In fact, these estimates provide more significant-statistics for my key independent variables.

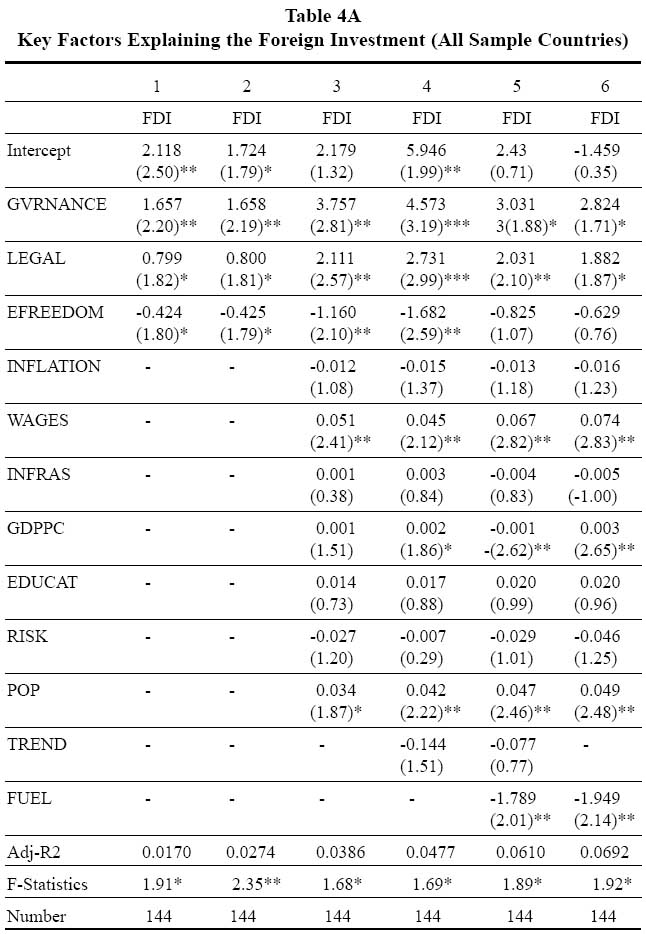

32 Table 4A provides the regression analysis by reporting 6 different esti-mates.4 The first estimate simply focuses on the key three independent variables followed by a similar regression that includes the time fixed affect by adding time dummy variables. Then I gradually added the other key relevant independent variables (regression 3). I added the time trend variable (regression 4). I added the fuel dummy variable (regression 5). Finally, I used a time fixed affect using year dummy variables instead of time trend in regression 6. The model statistics show a relatively low adjusted r-squared ranging from 2% to 6%. However, the goodness-of-fit statistics of these estimates is somewhat consistent with the various FDI literatures (De Mallo, 1997).5 Overall, the evidence indicates a strong positive and statistically significant impact of governance, legal systems, and economic freedom influencing the variability of the inflow of foreign investment. Better governance, legal systems with higher protection to stockholders and countries with higher economic freedom (score 1 represents highest therefore showing a negative coefficient) are significantly associated with higher foreign investment inflow in sample countries.

Table 3: Correlation Coefficents

Display large image of Table 4

Display large image of Table 5

33 The overall statistical significance in table 4A is best for the coefficients of governance variable supporting the hypotheses at 1% (regression 4), 5% (regressions 1, 2, & 3) and 10% (regressions 5 & 6) levels respectively. The coefficients are less significant however for the legal system with 1% (regression 4), 5% (regression 3) and 10% (regressions 1, 2, 5 & 6) levels. Finally, they are marginally significant for economic freedom, with 5% (regression 4) and 10% (regression 3) supports only. In general the key results remained relatively stable, except for a loss of statistical significance for economic freedom - even after the year fixed effect and control variables were added. A number of additional estimates were also performed, including regression with a country fixed effect variable and regression where highly correlated variables were deleted from the estimate. The tables for these regressions are not included given that the overall results did not change significantly.

34 Finally, considering that among the sample countries, Israel may be an outlier as it represents one of the most economically developed countries with stronger ability to attract foreign investment; I therefore performed additional estimations of the same model excluding Israel from the estimations. These results are presented in table 4B. In almost all cases, these results are consistent with the results listed in table 4A where Israel was included in the regression estimates. Therefore, the relative importance of governance, legal systems and economic freedom in affecting foreign investment suggests a consistent and robust finding in the MENA sample countries.

Table 4B: Key Factors Explaining the Foreign Investment (Excluding Israel)Discussion

35 The above results reveal a consistent support for the positive impact of governance, legal system and economic freedom on the flow of foreign investment in the MENA region. Among the three determinants, governance showed the most significant results followed by legal system and then economic freedom. The relatively lower importance of the last two determinants could be due to the fact that investors from different countries have varying degrees of tolerance for imperfections in the host country's investment environment. Hewko (2002) suggested that a foreign investor from a country with a tradition of corruption and weak enforcement of contract may not be as discouraged by the flawed legal system as an investor from a country with an ideal legal system. Similarly Perry (2001) noted that investors are generally insensitive to the nature of the host country's legal system and that their perceptions and expectations of the country's legal system may be significantly affected by such factors as their nationality, export orientation and size. The most important factor in attracting foreign investors is profitable business opportunities. This was obvious in post communist countries after perestroika where many foreign investors established presence despite the primitive and underdeveloped legal system. It is also currently much more apparent in Iraq. In the presence of good business opportunities investors are willing to factor into their risk analysis the lack of an efficient legal system (Hewko, 2002).

36 Similar reasoning could also apply to economic freedom. Furthermore, one could also argue that some of the variables found to have a significant effect on FDI flows in certain countries might not be transferable to the MENA region. A recent paper has shown that MENA countries are different from other developing countries with regards to FDI flows. Some of the determinants of FDI flows to developing countries are not significant for FDI flows to MENA countries (Onyeiwu, 2003). Although a review of the relevant literature would suggest that the degree of economic freedom in the host country could be a crucial determinant of FDI decisions, it is possible that the relative importance of trade openness - one of the 3 factors comprising the economic freedom index in this paper - could have biased the above results. While trade openness has been found to be consistently significant for FDI flows at the 1 percent level (Kravis and Lipsey, 1982; Culem, 1988; Edwards, 1990; Asiedu, 2002; Onyeiwu, 2003). However, its impact on the MENA region has been found to be very small. One standard deviation increase in trade openness resulted in just a 0.002 standard deviation increase in FDI flows to a MENA country (Onyeiwu, 2003). The author attributed such low marginal impact to the unusually high trade protection in the MENA region, which on average is not only the highest in the developing world but also the slowest to come down (Srinivasan, 2002, p.1). He suggested that a highly protective economy requires a substantial, not a token, increase in openness in order to attract a large flow of FDI.

Conclusion

37 While many regional, bilateral and unilateral efforts have led to a remarkably favorable government policy towards foreign investment activities around the world, differences still exist in the scope and depth of the free-flow of foreign investments and the operations of MNCs (Fatouros, 1990). Foreign investment activities can play a significant role in the development process of host economies. In addition to capital inflows, foreign investment activities can be a vehicle for obtaining foreign technology, knowledge, managerial skills, and improving the international competitiveness of firms and the economic performance of countries (UNCTAD, 1998). Foreign activities in terms of direct investment are probably one of the most significant factors leading to the globalization of the international economy (Erdal & Tatoglu, 2002).

38 As the MENA region competes for economic benefits for its citizens in the new global economy, it is important that the policy makers in these countries evaluate their comparative advantage and their relative strengths (weakness) in attracting foreign investment in their respective countries. Given the recent shift toward efficiency seeking investments in developing countries (Dunning, 2002), it is imperative for the market and resource limited MENA countries to improve their quality of governance and transparency; to promote a legal system that protects shareholders and creditors rights; and to enhance their economic freedom with more open trade and better protection of property rights.

39 Beside country based improvement a significant increase in FDI inflow could also be achieved if the entire MENA region is promoted as an integrated field of investment. Not only will foreign investors be able to see increased efficiency but also an integrated regional market would enlarge capacity and ensure scale effect in relatively small national markets. If these elements are ignored, not only will foreign investor not invest, it is likely that even local investors will take their investments abroad (Reese and Weisbach 2003).

References

Addison T. and Heshmati, A. (2003). Democratization and new communication technologies as determinants of foreign direct investment in developing countries, Research In Banking and Finance, 4: 102-128.

Asiedu, E. (2002). On the determinants of foreign direct investment to developing countries: Is Africa different? World Development, 30 (1):107-119

Becchetti, L. and Hasan, I. (2004) "The effects of (within and with EU) regional integration: Impact on real effective exchange rate volatility, institutional quality and growth for MENA countries," Working Paper, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy.

Beck, T., Levine, R. and Loayza, N. (2000). Financial intermediation and growth: Causality and causes, Journal of Monetary Economics, 46(1):31-77.

Chan-Lee, J. and Ahn, S. (2001). Informational quality of financial systems (IQFS) and economic development. An indicators approach for East Asia. Asian Development Bank Institute Working Paper 20.

Conklin, D. (2002). Analyzing and managing country risks. Ivey Business Journal, 66 (3): 36-41.

Culem C. G. (1988). The locational determinants of direct investments among industrialized countries. European Economic Review, 32: 885-904

Davis, J. and Ruhe, J. (2003). Perceptions of country corruption: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(4): 275.

De Mello, L. (1997). Foreign direct investment in developing countries and growth: A selective survey . The Journal of Development Studies; 34(1): 1-34.

Djankov, S., R. LaPorta, F. Lopez-de-Silanes and A. Shleifer. (2002). Courts: The lex mundi project. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank, mimeo.

Drabek, Z. and Payne, W. (2001). The impact of transparency on foreign direct investment. World Trade Organization, Economic Research and Analysis Division Working Paper #ERAD-99-02.

Dunning, J. (1993). Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Workingham: Addison-Wesley.

Dunning, J. (1999). Globalization and the theory of MNE activity. University of Reading Discussion Papers in International Investment and Management, 264 Reading.

Dunning, J. (2002). Determinants of foreign direct investment globalization induced changes and the roles of FDI policies. Paper presented at the Annual Bank Conference on Development Economists in Europe, Oslo, mimeo.

Edwards, S. (1990). Capital flows, foreign direct investment, and debt-equity swaps in developing countries. Working Paper Series. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Erdal, F. and Tatoglu E. (2002). Locational determinants of foreign direct investment in an emerging market economy: Evidence from Turkey. Multinational Business Review. 10(1)

Fatouros, A. (1990). The code and the Uruguay round negotiation on trade in services. Centre Reporter, 29: 7-15.

Gilmore, A.; O'Donnell, A.; Carson, D; and Cummins, D. (2003). Factors influencing foreign direct investment and international joint ventures: A comparative study of Northern Ireland and Bahrain. International Marketing Review, 20(2):195-215.

Globerman, S. and Shapiro, D. (2003). Governance infrastructure and U.S. foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 34:19-39.

Globerman, S. and Shapiro, D. (2002). Global foreign direct investment flows: The role of governance infrastructure. Memo.

Guenther, D. and Young, D. (2000). The association between financial accounting measures and real economic activity: A multinational study. Journal of Accounting & Economics, 29 (1): 53-72.

Gwartney, J.; Lawson, R. and Emerick, N. (2003). Economic Freedom of the World: 2003 Annual Report.

Habib, M. & Zurawicki, L. (2002). Corruption and foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(2):291-308.

Harms, P. and Ursprung, H. (2002). Do civil and political repression really boost foreign direct investments? Economic Inquiry, 40(4): 651-664.

Hewko, J. (2002). Foreign direct investment in transitional economies: Does the rule of law matter? East European Constitutional Review, Fall 2002/Winter 2003: 71-79.

Kaufmann, D. Kraay, A. and Zoido-Lobaton P. (1999a). Aggregating governance indicators. World Bank, Working Paper # 2195.

Kaufmann, D. Kraay, A. and Zoido-Lobaton P. (1999b). Governance matters. World Bank Working Paper # 2196.

Kaufmann, D. Kraay, A. and Zoido-Lobaton P. (2000). Governance matters: From measurement to action. Finance & Development, 37(2).

Kaufmann, D. Kraay, A. and Zoido-Lobaton P. (2003). Governance matters III, updated indicators 1996-2002. World Bank, Working Paper.

Kingsley, O; and Crumbley, L. (1997). Determinants of U.S. private foreign direct investments in OPEC nations: From public and non-public policy perspectives. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 9(2): 331-355.

Kravis, I.B. and Lipsey, R.E. (1982). The location of overseas production and production for export by U.S. multinational firms. Journal of International Economics,12: 201-223.

Lang, L. H.P. & So, R.W. (2002). Ownership structure and economic performance. Memeo.

LaPorta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer & R. Vishny. (1998a). Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106:1113-1155.

LaPorta, R., F. Lopez-de-Sialnes, A. Shleifer & R. Vishny. (1998b). The quality of government. NBER Working Paper 6727, Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, mimeo.

LaPorta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer & R. Vishny. (1999). Investor protection and corporate valuation. NBER Working Paper 7403, Cambridge, Mass.: NBER, mimeo.

LaPorta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer & R. Vishny. (2001). Investor protection and corporate governance. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University, mimeo.

Levy-Yeyati, E.; Panizza, U.; and Stein E. (2003). The cyclical nature of North-South FDI flows. World Bank.

Lim, E. (2001). Determinants of, and the relation between foreign direct investment and growth: A summary of the recent literature. Working paper WP/01/175.

Loewendahl, H.; and Loewendahl, E. (2000). Turkey's performance in attracting foreign direct investment: Implications of EU enlargement. CEPS Wo rking Document No. 157.

Loree, David W, Guisinger, Stephen E. (1995). Policy and non-policy determinants of U.S. equity foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 26 (2): 281-300.

Noorbakshsh F., A. Poloni and A. Youssef. (2001). Human capital and FDI inflows to developing countries: New empirical evidence, World Development, 29 (9): 1593-1610.

O'Doriscoll, P.; Holmes, K.; and Kirkpatrick, M. (2001). Index of Economic Freedom. Heritage Foundation and Wall Street Journal, New York.

Onyeiwu, S. (2003). Analysis of FDI flows to developing countries: Is the MENA Region different? Working paper presented at the Economic Research Forum 10th Annual Conference.

Perry, A. (2001). Legal systems as a determinant of FDI: Lessons from Sri Lanka. The Hague; Boston: Kluwer Law International.

Sadi, A. and Bolbol, A. (2001). Capital flow, FDI, and technology spillovers: Evidence from Arab countries. World Development, 29 (12): 2111-2125.

Selowsky, M. and Martin, R. (1997). Policy performance and output growth in the transition economies. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association.

Shaaban. H.S. (1999). Commercial transactions in the Middle East: What law governs. Law and Policy in International Business, 31 (1):157-173.

Srinivasan T.G. (2002). Globalization in MENA A long term perspective. Paper Presented at The Fourth Mediterranean Forum.

Reese, Jr. W. A.and Weisbach, M. S. (2002). Protection of minority shareholder interest, cross listings in the United States and subsequent equity offerings. Journal of Financial Economics, 66: 65-104.

UNCTAD (1998). World Investment Report, New York, United Nations.

UNCTAD. (1999). World Investment Report. New York, United Nations.

UNCTAD. (2002). The development dimension of foreign direct investment: Policies to enhance the role of FDI in the national and international context Policy issues to consider. Note by the UNCTAD Secretariat.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test of heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 48(4): 817-838.

World Bank. (2003). MENA development report. Trade, investment and development in the Middle East and North Africa: Engaging with the world. The World Bank, Washington D.C.

Endnotes