Vol.9 No.1 January 1998

Sten Gellerstedt

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

Garpenberg, Sweden

The author is Research Manager, Department of Operational Efficiency.

ABSTRACT

A radical, new innovation with regards to forestry machines is the designof a cab suspended from an arched column connected to a swiveling socket. The purpose of the design is to reduce the amount of skewed and twisted work postures, which are often frequent among operators of logging machines.The ability to sit straight is what most operators point out to be the most desirable feature of the self-leveling and swiveling cab. The low noise level is also appreciated, as is the ability to swivel the cab aroundon its vertical axis. The swiveling ability of the cab gives better visibility and also helps reduce the amount of head rotations. Furthermore, jarring motions and extreme swing due to uneven terrain are much less bothersome than in a conventional cab design. Vibration levels at the operator's seatin the self-leveling cab are equal to those measured in conventional rigid cabs. This new cab design provides comfort to the operator and improves the operator's ability to work at a sustained high efficiency. A follow-upstudy conducted over several years shows that the productivity of a harvester increased by 5 to 10% after a change from a rigid to a self-leveling and swiveling cab.

Keywords: Cab-design, ergonomics, work posture, productivity,vibrations.

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

This article describes the design and ergonomic studies of a self-leveling and swiveling cab manufactured by the Swedish company Pendo AB. Details are provided of a time-study, a follow-up of machine productivity, and the options of the operators who have used the new design. Additional studies are presented that describe entering and exiting the cab, cab size, work posture, visibility, vibrations on the operator's seat, noise, and the extent of cab usage.

Operators of forestry machines are exposed to an array of fatigue-causing factors: cab vibrations, jarring motions due to uneven terrain, uncomfortable work positions, and the constant twisting and turning of the head, neck, and cervical regions. Results of a health investigation of 1174 forest machine operators in Sweden indicated a prevailing average overload syndrome of 50%, mainly characterized by neck/shoulder complaints [3]. The pursuit of suitable technical solutions to these problems has been in the works for a number of years. Some of these solutions are cabs with better visibility, chairs with cushioned vibration, self-leveling chairs, the mounting of a bogie on both front and rear axles, split rear axles, wider tires, pendulum arms for all tires, a swiveling cab, the passive cushion of shock waves in the hydraulic system, an actively cushioning and leveling cab, and a suspended, self-leveling and swiveling cab.

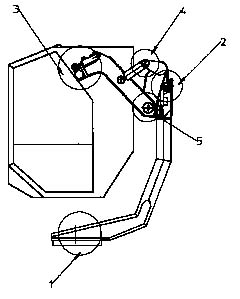

Within forestry, a self-leveling and swiveling cab is a radical new innovation for the alleviation of skewed and twisted work positions. In this design the cab is suspended from an arched column that is in turn connected to a swiveling socket (Figure 1). The cab can swivel around onits vertical axis from 0° to 270° and remains vertical in terrain with a 15° slope or less. The cab's swiveling ability is controlled by the operator and is separated from the movements of the crane. This gives the operator the means with which to adjust the cab for optimum visibility at all times. The arched column has a vibration-reducing and shock-absorbing joint positioned at the seat of the beam supporting the cab (at eye level behind the operator), the purpose of which is to keep the cab on a horizontal position sideways. Above this joint is a U-shaped cab carrier beam withone shock absorbing joint at each side of the cab working to keep the cabin a horizontal position lengthwise. The stiffness of these absorbing joints can be manually adjusted from within the cab.

To reduce the amount of vertical vibrations, attempts have been madeto use rubber bellows at the cab connection sites and hang the U-shaped cab carrier beam in an absorbing joint (Figure 2). The cab is intended to be mounted on new or used forestry machines. Approximately 90 cabs of this type have been produced up to mid 1997. Of these there are currently 80 mounted on harvesters and 10 on forwarders, mostly on older and renovated machines. The cost for a self-leveling cab ranges between US $15,000 and $23,000.

Figure 1. The self-leveling and swiveling cab suspended from an arched column attached to a swiveling socket.

Figure 2. Sideways view of self-leveling cab: 1) Swiveling socket; 2) Sideways cushioning (y-axis); 3) Lengthwise cushioning (x-axis); 4) Horizontal cushioning (z-axis); 5) Sidebeam.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Previous studies have been done of the self-leveling cab mounted ona number of single grip harvesters such as the FMG 250 super Eva [4] ,Timberjack 1270 [6], FMG 1870 [11]Hemek EGS [9], as well as the forwarder Kockums 85-35 [5,10].

In this study, the cab has, in most cases, been compared to conventional forestry machine cabs used in thinning and forwarding operations duringnormal work shifts. Thinning was carried out using the current Scandinavian short-wood system (cut-to-length system). Harvester-teams were comprised of a harverster with three alternating operators who operated machines in three-hour shifts for 12 hours a day. Forwarding was studied during normal work as well as when driving along a test track.

The program TWT [7] and a notebook computer was used in the time study. The following work elements were noted:"drive forward", "drive reverse", "crane out to the tree", "processingthe tree" and "others". Operators, management and the manufacturer's representatives were all asked to answer a set of prepared questions. The "Ergo-nomic Checklistfor Forestry Machinery" [2] was used while performing the ergonomic study. The production of an FMG 250 superE harvester was monitored before and after the change over to the self-leveling cab by the management from ASSIDomän Skog &Trä, Örebro forest management district.

Studies [4, 5,6] measured whole-body vibrations inthe x, y, z-directions simultaneously (WBWT according to ISO 2631/1, time-constant1 second) and used Brüel & Kjær 2231/s, vibration-unit 2522, program BZ 7105, and seat-recorder 4322. Studies [10,11] \used the Brüel & Kjær2512 and the seat-plate 4322. This particular equipment measures accelerationin one direction at a time only. The time-weighted noise levels, dB(A),were measured with the Brüel & Kjær 2221 noise meter withthe microphone placed just above the operator's breast pocket. The operator'shead movements (cervical spine rotations) were measured with a Nodmeter(jointed aluminium levers with goniometers worn by the operator).

RESULTS WITH COMMENTS

Time study and production. One hypothesis was that the work element "crane out" would be faster to perform from the new cab. The work element "crane out" took an average of 6.8 seconds to perform during thinning, using the self-leveling cab on the single grip harvester FMG 250 superE with the crane 170 E (Table 1). At a similar first thinning the work element "crane out" took 9.6 seconds [7]. In that study the operators used the conventional cab connected to the FMG 250 harvester and the crane 374E. Please note that the 170 E craneis more powerful than the 373 E, which makes it difficult in determining what part the self-leveling cab played in reducing the time for the work element "crane out".

During the first season (1992/1993), with the self-leveling cab mountedto a FMG 250 harvester, the productivity per hour rose by as much as 25%. This increase was due to, at least, three known factors:

Enter and exit the cab. In order for the operator to have a safeexit he/she has to turn the self-leveling cab in such a way that the dooris aligned with the ladder. If not, the exit will become an unforgettable "free fall" or at best an awkward climb over machine parts. A minor imposition occurs when an operator enters the cab. First, the step up into the cabis higher than usual and in a diagonal fashion. Second, the cab rocks back when the operator sets his/her foot in the cab. A later model of the cab, with vertical cushioning, can be lowered and positioned on the swiveling socket. This allows for a safer and more secure way to enter and exit thecab.

Working position. The operator's work environment and body posturein a self-leveling cab is horizontal even when the terrain is at an inclineup to 15°. The ability of the cab to swivel around its vertical axis allows the operator to position the cab so that the best possible view over the work area can be obtained. The operator is thus not exposed to the same amount of fatigue-inducing factors such as the skewed and twisted work postures that occur in a regular cab. After a few months operators using the self-leveling cab used its swiveling ability 0.8 times per tree.After two years the same figure had increased to an average of 2.3 times per tree. The swiveling ability was used while driving forward, gettingin position to cut, and during felling and processing.

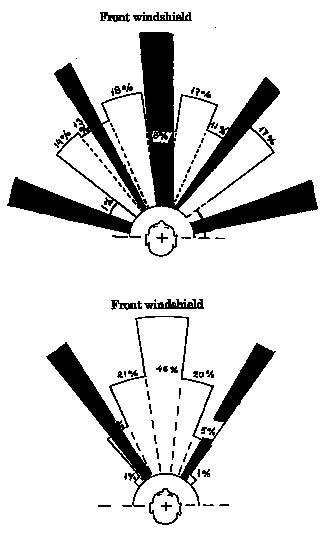

Operator head rotation (the cervical spine rotation) were measured and compared while using both the self-leveling cab and conventional rigid cabs (Figure 3). By mounting the self-leveling cab to the harvester Timberjack1270 the number of head rotations beyond 22.5° had been reduced by10 minutes per hour two weeks after delivery. As for the FMG 250 superE, the number of head rotations beyond 22.5° was reduced by as muchas 28 minutes per hour four months after the self-leveling cab was introduced.

Cab. The inside size of the self-leveling cab adheres to recommendationsset forth in the "Ergonomic Checklist" [2](Table 2). However, available leg and foot room is not sufficient for an operator of above medium height.

Figure 3. Distribution of operator head rotation (cervical spine rotation) within different sectors when measured with a "nodmeter" [7].The area in each sector represents the amount of time that the head spent there. The top picture shows measurements of an operator performing a thinning from a conventional rigid cab mounted to the FMG 250 E. The bottom picture shows measurements of an operator performing the same type of thinning while in a self-leveling cab mounted to a single grip harvester FMG 250 super E. The dark areas are restricted views.

Visibility from the cab. The self-leveling cab provides good visibility both upward and forward. Sun reflection in the windows is alleviated by turning the cab slightly to one side. The same turn applies for thewindshield-wiped part of the window during rain or snow. Limbs, which havethe potential to smear the windows, can be moved away by swiveling the cab. One problem, however, is that debris, snow, and ice tend to stickto the slanted window above the head of the operator. The operator's abilityto see below branches in a spruce forest is not as good as in a conventional rigid cab. This is because the self-leveling cab sits higher than usual(160 cm above ground in a Timberjack 1270). This is not a problem in apine forest where high operator level is advantageous.

Noise. Noise levels in the self-leveling cab are lower than in the two other types of cabs that were measured. The lowest measured noise level during a work shift in a self-leveling cab was 62 dB(A) and the highest 70 dB(A) (Table 3).

Vibrations. The vibration levels presented in Tables 4 and 5 show that there is no significant difference between the self-leveling cab and the conventional rigid cab regarding the vector sum of the three axes. Table 4 shows, however, that the vertical vibrations (z-axis) inthe self-leveling cab, without vertical cushioning, are higher compared to the rigid cab. Table 5 shows that the cushioning of the vertical vibrations reduced the vibration level.

Ideally, vibrations should be measured during a standardized run ona widely accepted work and test track. There is, however, no such accepted standard. Measurements of vibrations that are accounted for in this study have been made on a number of different machines, with different equipmentand in different terrain types, temperatures, speeds, etc.

Table 4. Vibration levels (m/s2) on the operator's seat, as measured in a harvester using a self-leveling cab without vertical vibration cushioning compared to a conventional rigid cab (a lower value is favourable).Harversters used were an FMG 250 super E(A), Timberjack 1270 (B), and FMG1870 (C).

| Self-lev. cab on A | Conventional rigid cab on A 2 2 3 3 |

Self-leveling cab on B 4 4 5 5 |

Conventional cab on B6 | Self-lev. cab on C | Self-lev. cab on B7 | |||||||||

| x-axis | 0.14 | 0.11 | - | - | - | - | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.23 |

| y-axis | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.39 |

| z-axis | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.50 |

| Vector sum. | 0.35 | 0.28 | - | - | - | - | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.80 |

1 Machine velocity in thinning and final cutting was 1.5to 5 meters/minute.

2 Frozen bare ground, +7°C, GSI=1,1,1 (G=Ground carryingcapacity, S=Surface structure, I=Inclination [1].

3 Snow 10cm,

+5°C, GSI=1,1,2.

4 Snow 10cm, -5°C, GSI=1,2,1,600 tress/ha.

5 Snow 75cm without frozen crust, -12°C, GSI=1,3,1,900 trees/ha.

6 Snow 25m, -2°C, GSI=1,3-4,2, 1600 trees/ha.

7 Velocity 56m/min, -5°C, GSI=1,2,1-2.

Table 5. Vibration levels during hauling along a 230-meter driveof frozen wetlands with the Kockums 85-35 forwarder at -24°C. The self-leveling cab with vertical cushioning is locked by the hanging the U-shaped cabcarrier beam in the absorbing joint.

| Empty | Loaded (13 m3f) | |||||||||||

| Self-leveling cab vertically cushioned | Self-leveling cab with locked vertical cushioning | Conventional rigid cab | Self-leveling cab vertically cushioned | Self-leveling cab with locked vertical cushioning | Conventional rigid cab | |||||||

| Velc. m/min | Vib. m/s2 | Velc. m/min | Vib. m/s2 | Velc. m/min | Vib. m/s2 | Velc. m/min | Vib. m/s2 | Velc. m/min | Vib. m/s2 | Velc. m/min | Vib. m/s2 | |

| x-axis | 49 | 0.50 | 52 | 0.47 | 52 | 0.45 | 49 | 0.40 | 49 | 0.38 | 51 | 0.42 |

| y-axis | 48 | 0.63 | 49 | 0.75 | 52 | 0.75 | 48 | 0.67 | 49 | 0.79 | 49 | 0.67 |

| z-axis | 49 | 0.42 | 50 | 0.50 | 52 | 0.447 | 48 | 0.40 | 48 | 0.50 | 48 | 0.45 |

| Vector sum | 49 | 1.22 | 50 | 1.35 | 52 | 1.31 | 48 | 1.17 | 48 | 1.34 | 49 | 1.20 |

1Temperature during time of measurements was -24°C, GSI=1,1-2,1(Table 2).

Table 6. Interviews with 13 experienced operators who had used the self-leveling cab mounted either on a harvester or on a forwarder. Two of the operators using the FMG 250 harvester had been interviewed inpart when the cab was new, and then again two years later. The operators of the Kochums 85-35 forwarder were interviewed in part when the vertical cushioning of the cab was carried out by using inflatable rubber bellows and in part when the cushioning was done using an accumulator connected to the cab carrier.

| Operators of harvester | Operators of forwarder, cab with vertical cushioning | ||||

| Questions | FMG 250 super E | Timberjack 1270 | Hemek EGS | Kockums 85-35, bellow | Kochums 85-35, abs joint1 |

| What is it like to work in the self-leveling cab? | Good, different, revolutionary, visibility, quiet, at level, stable. | Good. | Good, easy. | Good. | Better cushioning now. |

| What works better than in other cabs? | Visibility, ability to sit straight, fewer head rotations. | Softer, sitting horizontally, quiet, good visibility. | Visibility, sitting straight, better work posture. | Work posture, less noise, softer. | Softer vertical and less sideways bumping. |

| What works less well than in other cabs? | Not enough space for feet, feet jammed2, poor heating. | Space for feet | |||

DISCUSSION

What the operators appreciated most about the self-leveling and swiveling cab was the ability to sit horizontally and not have to tense up even in highly uneven terrain. The low noise level was also highly appreciated.The operators maintain the same opinions after several years of experience with the cab. Low noise levels and the ability to sit horizontally were considered beneficial for one's health. The operator's ability to swivel the cab was also noted as beneicial for production. The swiveling ability offers better visibility, which in turn speeds up the task of planning and working with the crane and the harvesting head. The amount of head rotation is greatly reduced as a result of the cabs swiveling ability, which consequently increases work pace.

Higher levels of vibrations and greater swing were concerns associated with the construction of a cab with a higher mount than the norm. However, measurements show that the self-leveling cab is under or on the same paras other conventional cabs with regards to vibrations. Bumps and jarring motions are considered to be less bothersome using the self-leveling cab. Furthermore, operators of the vertically-cushioned self-leveling cabs experienced added relief from jarring motions as well as from the swing that occurs when driving in terrain. Measurement also show that the vertical vibrations had been reduced.

The suspended cab may not be the best long-term solution. Ideally leveling should take place as low as possible, at the wheelbase/legs. However, that type of self-leveling is not fast enough by today's standards and is also more expensive.

The low noise levels occur because the cab is separated from the vehicle transmission and hydraulic components. Sound is carried through the airfrom the engine, mufflers, etc., and not through the frame of the machine.

The cab design still has shortcomings, such as problems when operators enter and exit and inadequate space for feet. The manufacturer is awareof the problems but has limited opportunities at present to increase footspace. One solution mentioned is removal of the air conditioning unit frombeneath the operator seat, allowing the chair to be moved back a little.

This study concludes that a suspended, self-leveling and operator-controlledswiveling cab allows for an improved comfort when compared to conventionalcabs. The operators are able to work longer with a sustained pace and work quality. "One tends to push the envelope just a little bit further", asone operator put it.

REFERENCES

[1] Anon. Terrängtyp schema för skogsarbete (Terrain classificationfor forestry work). SkogForsk, Uppsala, Sweden.

[Return to text]

[2] Anon. 1989. Ergonomisk checklista för skogsmaskiner (Ergonomicchecklist for forestry machinery). SkogForsk, Uppsala, Sweden.

[Return to text]

[2] Anon. 1989. Ergonomisk checklista för skogsmaskiner (Ergonomicchecklist for forestry machinery). SkogForsk, Uppsala, Sweden.

[Return to text]

[3] Axelsson, S.Å. and B. Pontén. 1990. New ergonomic problemsin mechanized logging operations. Int. J. of Ind. Ergonomics No. 5.

[Return to text]

[4] Carlsson, S. 1993a. Ergonomisk utvärdering av Skogsmekanhytten(Ergonomic evaluation of the Skogsmekan cab). Uppsatser &

Resultatnr 249. Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences, Department of Operational Efficiency.

[Return to text]

[4] Carlsson, S. 1993a. Ergonomisk utvärdering av Skogsmekanhytten(Ergonomic evaluation of the Skogsmekan cab). Uppsatser &

Resultatnr 249. Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences, Department of Operational Efficiency.

[Return to text]

[5] Carlsson, S. 1993b. Ergonomisk utvärdering av Kockum 85-35skotare med Skogsmekanhytt (Ergonomical evaluation of the Kokum 85-35

forwarderwith Skogsmekan cab). Arbetsdok-ument nr 37. Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences, Department of Operational Efficiency.

[Return to text]

[5] Carlsson, S. 1993b. Ergonomisk utvärdering av Kockum 85-35skotare med Skogsmekanhytt (Ergonomical evaluation of the Kokum 85-35

forwarderwith Skogsmekan cab). Arbetsdok-ument nr 37. Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences, Department of Operational Efficiency.

[Return to text]

[6] Carlsson, S. and S. Gellerstedt. 1993. Ergonomisk utvärderingav Skogsmekanhytten på Timberjack 1270 (Ergonomic assessment of

the Pendo cab mounted on Timberjack 1270). Arbetsdokument nr 38. Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences, Department of Operational Efficiency.

[Return to text]

[6] Carlsson, S. and S. Gellerstedt. 1993. Ergonomisk utvärderingav Skogsmekanhytten på Timberjack 1270 (Ergonomic assessment of

the Pendo cab mounted on Timberjack 1270). Arbetsdokument nr 38. Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences, Department of Operational Efficiency.

[Return to text]

[7] Gellerstedt, S. 1993 Att gallra med skogsmaskin- det mentala ochfysiska arbetet (Thinning with a forestry machine the mental andphysical

work). Uppsatser & Resultat nr 244. Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences, Department of Operational Efficiency.

[Return to text]

[8] Gellerstedt, S. 1994. Uppföljning av Skogsmekanhytten påTimberjack 250 super E (A follow-up of the Skogsmekan cab mounted on

Timberjack250 S E). Arbetsdokument nr 14. Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences,Department of Operational Efficiency.

[Return to text]

[9] Henningsson, L. and S. Gellerstedt. 1994. Ergonomisk granskningav Hemek engrepps-skördare med Pendohytt (Ergonomic assessment

ofthe Hemek harvester with a Pendo cab). STORA SKOG 1994-11-10. Falun, Sweden.

[Return to text]

[10] Lundström, K.Å., 1996. Utvärdering av vertikaldämpad Pendohytt (Evaluation of a vertically cushioned Pendo cab).

Länshälsan AB, Storuman, Sweden.

[Return to text]

[11] Persson, G. 1993. Besked om resultat av inspektion (Result froman inspection) Inspektionsmeddelande 1993-10-11, Yrkes-inspektionen,

Härnösand, Sweden.

[Return to text]

[11] Persson, G. 1993. Besked om resultat av inspektion (Result froman inspection) Inspektionsmeddelande 1993-10-11, Yrkes-inspektionen,

Härnösand, Sweden.

[Return to text]