A New Solution to the Nuclear Waste Problem in Canada:

Near-Reactor Storage in Large-Diameter Boreholes

R. Kretz197 Augusta St. Ottawa, ON, Canada K1N 8C2

Submitted January 2008. Accepted as revised, May 2008

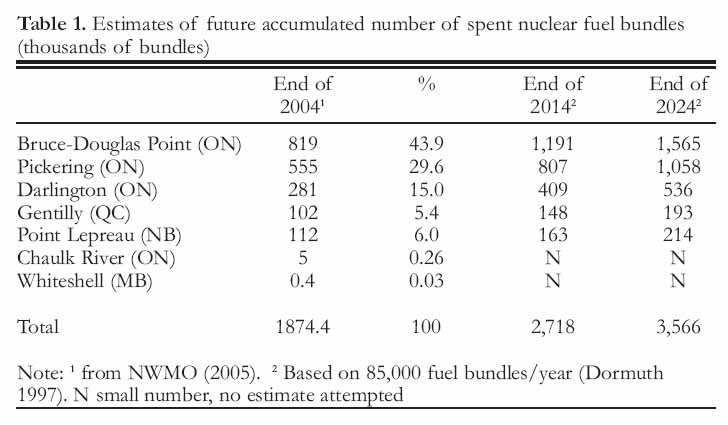

1 INTRODUCTION In the 1970s, the problem of the disposal of high-level nuclear waste, produced by Canadian nuclear reactors, was receiving increasing attention (Aikens et al. 1977). From the onset, and to the present, the preferred solution was placing the spent fuel bundles at a single (central) site somewhere in the Canadian Shield, at a depth of several hundred metres (Aiken et al. 1977; Tammemagi et al. 1977; AECL 1994; OHN 1994; NWMO 2005). Although different types of rock were considered, including limestone and shale, a large body of homogeneous granite was almost invariably viewed as being the most suitable as a repository. If adopted, the central-site concept would require major excavation of rock (site) and the transport of about 3.6 million spent fuel bundles from the reactors located in Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick, to the central repository (Table 1). In the "Adaptive Phased Management" proposal of NWMO (2005), the fuel bundles would initially be placed at a depth of 50 m and later moved to a depth of several hundred metres, or returned to the surface for reprocessing.

Table 1. Estimates of future accumulated number of spent nuclear fuel bundles (thousands of bundles)

Display large image of Table 1

2 During the past three and a half decades, several changes have occurred in Canada and abroad that call for a re-examination of the nuclear waste problem and a critical evaluation of the central-site concept. These changes are as follows:

- As a result of recent advances in the design of rock drills, it is now possible to drill vertical boreholes six or more metres in diameter to a depth of several hundred metres. (Franklin and Dusseault 1989; Tativa 2005), making it unnecessary to send workers underground. Drilling is relatively easy in limestone, the common rock type beneath the generating stations in southern Ontario, and the rate of drilling is about three metres an hour for large-diameter boreholes.

- Public opposition to nuclear energy has increased as a consequence of the Chernobyl incident in 1986; this attitude was expressed repeatedly during the Seaborn hearings (Seaborn 1998). Therefore, it seems unlikely that people, who live in the transport corridors, leading from nuclear generating stations to the central site, will accept the movement of trucks or trains laden with highly radioactive waste through their communities. With 192 fuel bundles in each transport cask, three 18-wheel tractor-trailer trucks would arrive at the central site each day for 20 years. Or, if transport is by rail (10 freight cars each with three casks), 30 trains would arrive at the central site each year for 20 years. Caccia (2007) has emphasized that major socio-political problems must be expected, especially within, and adjoining, the transport corridors.

- During the past 3 ½ decades, focus on the environment has increased enormously, culminating, recently, in a concern over global warming and the role of carbon dioxide emissions from vehicles in contributing to this warming. At a time when hydrocarbon resources should be conserved and CO2 emissions need to be reduced, the central-site plan will require 18 million kilometres of truck travel, assuming a central site in the vicinity of Sudbury. A total of 6 million litres of fuel would be consumed (CT 2006). For rail or combined truck rail transport, these numbers are somewhat lower, but if the central site is "remote" (Aiken et al. 1977) or in Saskatchewan (being considered by NWMO 2005), the numbers will be much larger. In addition, there would be emissions of nitrogen oxide and other pollutants from the burned hydrocarbons.

- Until recently, health effects of low-level ionizing radiation (above the background levels of 2-3 mSv/year) were largely unknown and controversial (Chapman and McCombie 2003). In 1992, a detailed study of 95,247 British workers in the nuclear industry (Kendall et al. 1992) produced "evidence for an association between radiation exposure and mortality from cancer, in particular, leukaemia (excluding chronic lymphatic leukaemia) and multiple myeloma". Based on their results, some environmentalists have argued that the maximum allowable dose of 20 mSv/year, the number adopted internationally and by AECL (1994), should be reduced to 10 mSv/year (Aldhous 1992). Although fuel bundles are moved robotically and workers are shielded, the number of times that the fuel bundles are moved from one place to another in the presence of workers should obviously be minimized. In the no-retrieval central-site concept envisaged by NWMO (2005), each fuel bundle would be moved at least eight times. The crucial question here is, which of two plans should be adopted, one that will expose n workers to x mSv/year of radiation (central-site), or the other that will call for less handling of the waste and will expose fewer workers to less radiation (multi-repository).

- Since the Oka confrontation in 1990 and the appearance of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples Report in 1996, the number of unresolved land claims in Canada has increased from 400 to 800 and is expected to grow. One-third of these are in Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Canada (INAC 2007). Although members of NWMO provide assurance that these claims will be respected when choosing a central repository site (NWMO 2005), some resistance from Native People, now and sometime in the future, must be expected with regard to the location of a central site and the transport corridors.

3 In addition, there is the troubling question of how many human injuries and deaths will occur during the transport and mining operations that form an integral part of the central-site solution. With regard to transport, deaths and injuries have decreased on Canadian roads since 1986 (by a factor of 0.75), but the numbers themselves remain high at 3,000 deaths and 211,000 injuries a year (TC 2005, 2006). Although the 18 million kilometres of truck travel calculated above are relatively small, accidents involving the transport trucks will certainly occur in the projected 20-year period. Accidents involving trains are not as common, but if rail transport is used, some injuries must be expected. With regard to rock excavation at the central site, adverse health effects (e.g. silicosis) and injuries or fatalities (from rock bursts and other accidents) are predictable. Members of AECL (1994) have estimated a maximum of 2590 injuries and 12 deaths during 64 years of construction, operation, and decommissioning. Thus some consideration should be given to possible solutions to the waste problem that require very little transport of the waste and no conventional mining operations.

THE MULTI-REPOSITORY, NEAR-REACTOR MODEL

4 In a multi-repository, near-reactor model, large-diameter boreholes are drilled from surface to a depth of 150 m, spent-fuel bundles are placed in metal containers (canisters), and the containers are lowered into the bore-holes that are then capped and sealed.

5 Consider, for example, the construction of a repository near the Pickering generating station, 32 km east of Toronto (Table 1). A drill hole at the town of Pickering (OGS-83-3, elevation 89.7m) encountered near-horizontal beds of Ordovician limestone and shale as follows (Johnson 1983):

- 0-25 m - unconsolidated sediment (overburden)

- 25-44 m - Blue Mountain Formation; shale

- 44-48 m - Lindsay Formation; shale and calcareous shale

- 48-81 m - Lindsay Formation; limestone

- 81-148 m - Verulam Formation; limestone, minor calcareous shale

- 148-198 m - Bobcaygeon Formation; limestone, minor shale

- 198-227 m - Gull River Formation; limestone

- 227-236 m - Shadow Lake Formation; impure limestone, siltstone, sandstone. At base, quartz conglomerate

- 236-251 m - Precambrian rocks; gneiss

6 Following the selection of a suitable site, preferably less than 1 km from the generating station, a borehole 1.5 m in diameter is drilled to a depth of 150 m. Prior to drilling, groundwater is withdrawn to depress the water table, if necessary. The borehole is lined with metal tubing, and the space between the lining and the wall is filled with fine aggregate (sand) concrete, which also acts as a grouting material. Note that, unlike conventional shaft-sinking procedures, the drilling operation produces few (unwanted) fractures. The repository will extend from 50 to 150 m, and will occur within limestone and minor shale (see above).

7 Different sizes of corrosion-resistant metal containers can be designed, but the one proposed here is a hexagonal prism, 1.2 m in diameter and 2.0 m high; this will take 360 fuel bundles (each 10 cm in diameter and 0.5 m long) in a honey-comb configuration. Fifty of these containers (a total of 18,000 bundles) are lowered into the borehole to form a cylindrical repository. Spaces between fuel bundles in the containers and between the containers and the steel liner are filled with finely ground cuttings (limestone and shale fragments brought to the surface during the drilling operation); lime (CaO) could be added, which reacts with water to form Ca(OH)2. In 2014, approximately 807,000 waste-fuel bundles will have been produced at Pickering (Table 1) and these will require about 45 repositories, constructed sequentially in groups of 12. The grid could be squared or hexagonal. The repositories, when separated at 100 m intervals to facilitate heat loss, will form an array beneath a surface area of 0.40 km². Sensors placed underground would monitor temperature, groundwater flow, and radioactivity. Retrieval of the waste containers, if necessary, would be a relatively simple matter. By increasing the diameter of the boreholes, fewer would be needed; indeed, many variations of the above scenario are possible.

8 Most of the other nuclear generating stations are underlain by rocks similar to those beneath Pickering. At the Darlington generating station 30 km to the east, the same rock formations are present and it may be possible to form a single repository array somewhere between the two stations. At the Bruce generating station (on the shore of Lake Huron), the underlying rock, consists of gently dipping Upper Silurian and Lower Devon-ian limestone (mainly dolomitic limestone) and minor sandstone to a depth of 300 m; Precambrian rocks lie at a depth of nearly 1100 m (Johnson et al. 1992). The Gentilly generating station, east of Trois-Rivières in Quebec, is situated on Upper Ordovician shale and limestone (Dresser and Denis 1944).

9 However, the Point Lepreau station, in New Brunswick, is situated on Triassic sandstone and conglomerate; limestone is rare within 30 km of the generating station but several varieties of granitic rock occur (McLeod et al. 1994). At Chalk River and Whiteshell, in Ontario and Manitoba respectively, granitoid rocks are also present (Douglas 1970) but the numbers of spent fuel bundles in temporary storage are low relative to the other generating stations (Table 1). Drilling large-diameter boreholes in granitoid rocks is not as easy as it is in limestone but it can be done.

10 The view that a nuclear waste repository must necessarily lie at a depth of several hundred metres, rather than at 3000 m (the deepest mines) or at 100 m (the present proposal), is questionable. It is generally agreed that storing the fuel bundles at the Earth’s surface or in unconsolidated sediment is not acceptable. However, it is not clear why a depth of some 800 m is required or why all of the waste must be stored at a single site.

11 One argument for deep burial is that after 100,000 years, the time needed for radioactivity to decrease from 1016 to 10 9 Bq/kg of uranium (Wiles 2002), comparable to that of uranium ore, erosion could expose the fuel bundles. However, the rate of erosion in regions of low to moderate elevation and low relief (e.g. the Mississippi basin) is only 1 m/100,000 years (Holmes 1965) and the repositories described here, extending from 50 to 150 m would certainly not be exposed until much later.

12 Another consideration is that fuel bundles will come in contact with groundwater, which in rock moves principally along fractures. Few studies of fracture density as a function of depth are available, but Stone et al. (1989) have shown that in one 1,200 m borehole in granite, the fracture density remains nearly constant to 1,000 m, and then increases. Although, in general, groundwater flux is expected to decrease with depth (Cherry and Gale 1979), data from deep mines indicate that much variation exists in the amount of water that must be pumped to the surface to keep the mines dry. Moreover, in view of changes in climate, groundwater systems can be expected to change with time, and a repository site that is relatively dry and favourable today, need not be so 1,000 years from now. In the repositories that are proposed here, the uranium oxide pellets are surrounded by seven barriers, and it seems highly unlikely that appreciable groundwater would penetrate all of these barriers in 100,000 years. But in view of the very small size of the water molecule, some penetration by diffusion should be entirely acceptable, regardless of burial depth, in conformity with the laws of thermodynamics.

13 There is also the question of heat flow from spent fuel into the barriers and into the wall rock. Franklin and Dusseault (1991) have noted that in a deep repository, fuel bundles, barriers, and wall rock could be heated to temperatures as high as 230° C. Given that the rates of chemical transformations, including diffusion, increase rapidly with an increase in temperature, considerable damage to the repository systems can be expected. At a depth of 100 m, release of heat would occur more readily, and could, to some extent, be controlled and utilized.

CONCLUSION

14 In conclusion, the multi-repository solution to the nuclear waste problem, proposed here, offers many advantages over the central-site solution that for many years has been advocated by members of AECL (1994) and recently by members of NWMO (2005). These advantages include the following:

- Fewer injuries to the public resulting from traffic accidents,

- Fewer adverse health effects among workers resulting from rock excavation,

- Fewer deaths and adverse health effects among workers exposed to radiation,

- Greater respect for native peoples and their land-resource claims,

- Greater respect for members of the public who oppose the transport of radioactive waste through their communities

- Less addition of CO2 to the atmosphere

- Less pollution to the atmosphere

- No transport casks needed

- Greater ease of heat escape

- Greater ease of retrieval of fuel bundles

- Anticipated lower costs

15 In view of the magnitude of the nuclear waste problem, i.e. to isolate certain toxic materials for 100,000 years, one must wonder why various solutions to the problem, including the one presented here, are not receiving more attention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many discussions with Charles Caccia (Institute of the Environment, University of Ottawa) have been very helpful and are gratefully acknowledged. The manuscript was prepared by Nina Kretz. Comments from S.R. McCutcheon are greatly appreciated.REFERENCES

AECL (Atomic Energy of Canada Limited), 1994, Summary of the Environmental Impact Statement on the Concept for Disposal of Canada’s Nuclear Fuel Waste: AECL-10721 COG-93-11.

Aiken, A.M., Harrison, J.M., and Hare, F.K., 1977, The Management of Canada’s Nuclear Waste: Energy, Mines, and Resources, Policy Sector Report EP 77-6.

Aldhous, P., 1992, Leukaemia linked to radiation: Nature v. 355, p.381

Caccia, C., 2007, Keep nuclear waste where it is: Ottawa Citizen, 27 June 2007, p A11.

Chapman, N. and McCombie, C., 2003, Principles and Standards for the Disposal of long-lived Radioactive Wastes: Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Cherry, J.A., and Gale, J.E., 1979, The Canadian program for a high-level radioactive waste repository: a hydro-geological perspective: in Barnes, C.R., ed., Disposal of High-Level Radioactive Waste: The Canadian Geoscience Program. Geological Survey of Canada, Paper 79-10.

Dormuth, K., 1997, Presentation to the Environmental Assessment Panel Reviewing the Nuclear Waste Management and Disposal Concept: AECL unpublished document.

Douglas, R.J., 1970, Geology and economic minerals of Canada. Geological Survey of Canada, Economic Geology Report No. 1

Dresser, J.A. and Denis, T.C., 1944, Geology of Quebec: Geological Report 20. Quebec Department of Mines.

Franklin, J.A., and Dusseault, M.B., 1989, Rock Engineering: McGraw Hill, New York.

Franklin, J.A., and Dusseault, M.B., 1991, Rock Engineering Applications: McGraw Hill, New York.

Holmes, A., 1965, Principles of Physical Geology: Thomas Nelson and Sons, London.

INAC (Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2007, Specific claims: Justice at last.

Johnson, M.D., 1983, Oil shale assessment project. Deep drilling results 1982-1983, Toronto Region: Ontario Geological Survey, Open File Report 5477

Johnson, M.D, Armstrong, D.K., Sanford, B.V., Telford, P.C. and Rutka, M.A., 1992. Paleozoic and Mesozoic Geology of Ontario, in Thurston P.C., Williams, H.R., Sutcliffe, R.H. and Scott, G.M., eds., Geology of Ontario, Ontario Geological Survey, Special volume 4.

Kendall, G.M., Muirhead, C.R., MacGibbon, B.H., O’Hagan, J.A., Conquest, A.J., Goodill, A.A., Butland, B.K., Fell, T.P., Jackson, D.A., Webb, M.A., Hay-lock, R.G.E., Thomas, J.M. and Silk, T.J., 1992. Mortality and occupational exposure to radiation: first analysis of the National Registry for radiation workers: British Medical Journal v. 304, p.220-225.

Mcleod, M.J., Johnson, S.C., and Ruitenberg, A.A. 1994, Geological map of southwestern New Brunswick, New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources and Energy, Map NR-5, 1:250,000 scale.

NWMO (Nuclear Waste Management Organization), 2005, Choosing a Way Forward. The Future management of Canada’s used Nuclear Fuel: Government of Canada.

OHN (Ontario Hydro Nuclear), 1994, The disposal of Canada’s nuclear fuel waste: procedure assessment of a conceptual system: Nuclear Waste and Environment Service Division, Toronto.

Seaborn, B., 1998, Report of the nuclear waste management and disposal concept environmental assessment panel: Canada’s Environmental Assessment Agency. Ministry of Public Works and Government Services Canada.

Stone, D. Kamineni, D.C., Brown, A. and Everitt, R., 1989, A comparison of fracture styles in two granite bodies of the Superior Province: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences v. 26, p. 387-403.

Tammemagi, H.Y., Gale, J.E., and Sanford, B.V., 1977, Underground disposal of Canada’s nuclear waste: Geoscience Canada v. 4, p.71-76.

Tativa, R.R., 2005, Surface and Underground Excavations-Methods Techniques and Equipment: A.A. Balkema, Leiden.

TC (Transport Canada) 2005, Canadian Motor Vehicle Traffic Collision Statistics.

TC (Transport Canada) 2006, Transportation in Canada 2006, Annual Report.

Wiles, D.R., 2002, The Chemistry of Nuclear Fuel Waste Disposal: Polytechnic International Press. Montreal.