Robert Bond and the Pink, White and Green:

Newfoundland Nationalism in Perspective

James K. HillerMemorial University

1 PROFESSOR W.S. MACNUTT WAS THE FIRST HISTORIAN to treat the four Atlantic provinces as a single unit.1 He did so (probably) at the decree of the editors of the Canadian Centenary Series, whose view of the Canadian past was generally traditional and centralist. The essential story was assumed to be the evolution of Ontario and Quebec, and later the opening of the West. Atlantic Canada therefore merited only a collective volume up to 1867 in the Centenary Series, and has thereafter occupied a secondary place in the national narrative.2 As for Newfoundland (let alone Labrador) after 1867, Canadian historians still remain uncertain about what to do with it. The fact that Newfoundland experimented with political independence for some 80 years seems to have cast it as a perpetual and irrelevant historical outsider, in spite of a family resemblance and many links with mainland Canada. An outsider Newfoundland still seems to be, almost 60 years after it became a province, and the assertive local nationalism of many Newfoundlanders and their provincial governments since the 1970s seems at times to surprise and offend other Canadians. From the mainland perspective, Newfoundlanders tend to bite the hand that has fed and sustained them: "Confederation: our blessing, their burden", as the Newfoundland poet Mary Dalton has put it.3 From the Newfoundland perspective, mainlanders fail to understand that the latest addition was once a country, that local nationalism has deep historical roots and that Newfoundlanders have an old and distinct identity. In this sense, Newfoundland is more like Quebec than any other Canadian province; yet while Quebec has a major role in defining the national agenda, Newfoundland (like the rest of Atlantic Canada) is marginalized, having a small population and therefore little political clout. Geographical extent, as in the North, is irrelevant.

2 The word "Newfoundland" rather than the current official provincial label of "Newfoundland and Labrador" is used here deliberately, since this paper discusses Newfoundland and not Labrador nationalism. For many years, Labrador was treated as a subordinate dependency of Newfoundland, and the territory did not develop its own effective and separate political and cultural consciousness until the late 1960s and after. Since that time, Labrador has been recognized as the distinct region that it always was, with independent characteristics and identities. Labrador deserves another paper.

3 With that qualification, how best to approach the question of a purely Newfoundland nationalism? This paper examines two rather different icons of the so-called neo-nationalist movement. The most obvious is the Pink, White and Green flag [PWG], a 19th-century creation that is enjoying a widespread efflorescence, and in the background lies the cult of Robert Bond (1857-1927), premier from 1900 to 1909, who is popularly thought to represent all that was best in pre-Confederation Newfoundland and to have been the country’s most outstanding political leader.

4 The PWG tricolour is widely flown these days, appears on the masthead of The Independent newspaper and is available on car plates, t-shirts, hats, swimsuits and so on – sometimes with the byline "Republic of Newfoundland". Even the province’s liquor commission has jumped onto the trend, with a new rum displaying the PWG on the label. The phenomenon has been called "Newf-chic".4

5 The origins of the PWG flag are uncertain, the only point of agreement being that it dates to the 1840s. There are two theories about its origins – one probable, the other "wrong but romantic".5 The more prosaic theory is that the PWG derives from the flag flown by the Newfoundland Natives’ Society. That flag displayed a green fir tree on a pink ground and, underneath in white, clasped hands and the words "Union and Philanthropy". Some accounts include a wreath incorporating the shamrock, the rose and the thistle.6 This complex flag later became simplified into a tricolour. Thus, in this story, the PWG is the native flag, derived from that of a society which was nondenominational and presented itself as politically neutral (though it was in fact conservative), and provided common ground for those who resented the power and patronage enjoyed by privileged immigrants, whether English or Irish, as well as their condescension. 7

6 The romantic story has its own variants. It is said that when men came into St. John’s to join vessels going to the seal hunt crews would, before sailing, join in competitive wood hauls for the various churches. Irish Catholic crews flew green flags and the Protestant crews flew pink flags. The situation became so turbulent that an appeal was made to the Roman Catholic bishop, Michael Anthony Fleming, to act as mediator. It is unclear whose idea this was, though some accounts improbably say it was the wholly Protestant government. Fleming took some white cloth and joined the pink and green together, encouraging the rowdies to calm down and fly the same flag. Another version has the tension existing between rival groups of Catholics – native ("Bush-born") and immigrants ("Old Country") – and Fleming intervening as in the first version of the tale. The colour white has a variety of symbolic meanings, and two seem to apply here. White is the colour of peace, symbolizing a truce, and that is the meaning ascribed to it in some versions of the story. But other accounts say that Fleming chose white as representing the cross of St. Andrew, and so created a flag that represented the three founding races of Newfoundland, the English, Irish and Scots. Thus, in these stories, the PWG can be seen either as the flag of all Newfoundlanders regardless of race or religion or as a Roman Catholic flag pure and simple.8

7 It is probable that the PWG derives from the Natives’ Society flag and that the Fleming stories are invented tradition. They did not appear in print until 1900,9 and the version that has white representing Scotland has all the elements of a foundation myth. Moreover, when the PWG appeared in local flag charts, it was called "the Native Flag".10 It is nevertheless true that the flag did come to be seen, by some Protestants anyway, as a Catholic emblem.

8 Today’s nationalists are not much concerned about where the flag came from; that it seems to represent both natives and all Newfoundlanders, and serves as a reminder of the pre-Confederation past, seems to them to be appropriate and useful. To the historian, it is interesting that the flag appeared in the 1840s. Phillip McCann has argued that this was a period of "state formation" in Newfoundland when the government, most notably while Sir John Harvey was governor, made a deliberate attempt to promote Britishness as part of the Newfoundland identity and in this way sought to cement together a society that was divided between Catholics and Protestants, Irish and English, native and newcomer.11 In addition, McCann points to the promotion of "national" institutions, such as the Newfoundland Agricultural Society, as opposed to sectional or ethnic organizations such as the Benevolent Irish Society or the British Society. The evolution of a "national" flag would fit in this context. Patrick O’Flaherty, however, will have none of this. To him, a significant theme of the 1840s is the failure of nativism and the Natives’ Society to make a significant impact on Newfoundland public life, which remained as factionalized as ever. Harvey he dismisses as an extravagant and ineffective manipulator, but he does allow that the seeds of Newfoundland nationalism were sown in this decade thanks largely to the Natives’ Society. If nativism failed, and the society faded away in the late 1840s, this was because immigration had declined to a trickle, the politically active natives were disunited and natives simply took control of the state since most of the population by the 1850s was native-born anyway. The society’s legacy was an unofficial flag and an inclusive rhetoric that encompassed the outports as well as St. John’s – a rhetoric that stressed unity, moderation and reform.12

9 Nevertheless, nativism remained a force in Newfoundland politics well into the late-19th century and "Newfoundland for Newfoundlanders" became a common enough cry. It is difficult to say how widely the PWG was flown. It is claimed that it was often flown by Newfoundland vessels and that it decorated triumphal arches on festive occasions. In addition, it is said that it was used by anticonfederates in the late 1860s and sometimes by candidates in election campaigns to signify patriotism. But in all of these instances it seems to have been paired with the Union Jack. Newfoundland nationalism from its inception, like colonial nationalisms elsewhere, always stressed loyalty to the Crown and the empire. The PWG could never replace – and never did – flags that were British-derived.13

10 But did Newfoundland nationalism grow out of local nativism? Another, earlier root can be found in the first organized political movement in Newfoundland – the campaign by St. John’s reformers after 1815 to persuade the British government that Newfoundland should be recognized as a colony and should be granted representative government.14 The leaders and many of the supporters of this campaign were immigrants, not native-born, and their rhetoric was focused on political reform, which was achieved in two stages – in 1824 and 1832. Their task was to convince the imperial government that a permanent and viable colonial society had emerged in Newfoundland that wanted, needed and deserved the same rights and political institutions as other British colonies of settlement. Thus their speeches and pamphlets included arguments and assertions designed not only to persuade British politicians and bureaucrats, but also to unify and invigorate their own supporters and followers. Some of these elements have had a long life.

11 Like the natives later on, the reformers insisted on their loyalty to Britain and the Crown. But two other strands deserve comment. First was a faith in the country’s natural resources and its economic potential. This confidence was not shared by all the reformers, but many of them, above all the indefatigable Scot Dr. William Carson, trumpeted the great and prosperous future that lay ahead. Newfoundland had more than fish and seals: it had minerals, forests and land that could be used for agriculture. Indeed, the land was the key to future prosperity.

12 Linked to this assumption of a rich resource base was a historical explanation for Newfoundland’s backwardness when compared to the other British North American colonies. If there was little beyond subsistence agriculture, and if the fisheries dominated the economy, this did not demonstrate that other valuable resources did not exist – far from it. Backwardness and retarded development was a legacy of the way Newfoundland had been treated by a British government intent on maintaining the migratory fishery. It was the West Country merchants and their so-called Star Chamber rules, the fishing admirals, the whole machinery of the migratory fishery that had condemned Newfoundland to social, economic and political retardation. British fishing interests and the British government had obstructed settlement, had driven planters from their homes, had forbidden economic diversification. Variations on this refrain were to become commonplace in nationalist discourse, and can still be heard today. Newfoundland and its residents in this version of events had been the victims of a hostile imperial policy that was antithetical to the establishment of a settled colonial society, which had emerged nevertheless thanks to the efforts of the hardy and resilient settlers. Newfoundland was born, therefore, from a struggle between the resident planters and the migratory fishing interests.15 Research over the past 35 years has shown that this version of events is an exaggerated caricature of the reality. However, it provided a unifying myth and a convenient explanation for the country’s predicament that shifted the blame to external forces. If Newfoundland was backward, it was not Newfoundland’s fault since the country had always been the victim of imperial policies. At the same time, however, it remained firmly loyal to Britain and the empire. Indeed, Newfoundlanders often claimed that they were the most loyal of any of Her Majesty’s subjects. Phrases used later in the century such as "the sport of historic misfortune" or "the Cinderella of Empire" are telling: exploited and neglected, Newfoundland would nevertheless find the magic slipper.

13 Two events in the mid-19th century helped to cement Newfoundlanders’ sense of identity. The first was a major crisis in 1857 over the French Shore. This now-long-forgotten dispute was of huge importance in 19th- and early-20th century Newfoundland and became a defining element in Newfoundland nationalism.16 It reinforced the idea of Newfoundland as the eternal victim, provided another historical explanation for backwardness – another scapegoat, if you will – and became a unifying force in that all Newfoundlanders wanted to see the French gone from their shores. This is not the place to discuss the French Shore question in any detail. Suffice it to say that Newfoundlanders intensely resented the fact that the French held fishing privileges along a lengthy coastline under ambiguously worded 18th-century treaties, which the French interpreted to mean that they alone could fish along that coast, that settlement was illegal and that the colonial government had no business there. In 1857 the imperial government signed a draft convention with France that redefined the French position on the French Shore. Seen as eminently reasonable in Europe, it was unanimously condemned in the colony as conceding far too much to France. That the British government withdrew the convention as a result was seen as a great national victory, especially since the colonial secretary promised that in the future no changes to the colony’s territorial or maritime rights would be made without its consent. The so-called "Labouchere despatch" was seen as a colonial magna carta. Thus, the crisis affirmed the colony’s status within the empire while at the same time establishing the French Shore issue as a patriotic touchstone. Any talk of concession or compromise sparked immediate suspicions of local perfidy or imperial machination. Loyal Newfoundland might be, but all too often – as the cliche went – history showed that Britain was ready to sacrifice the colony on the altar of imperial expediency; as the dispute dragged on, the French presence came to be seen more and more as a barrier to the colony’s economic progress and prosperity.

14 The French Shore issue reinforced ambiguities in the imperial relationship. These popular verses from 1857, called "Hurrah for Newfoundland", catch the spirit well:The world may show, than Newfoundland,

More fertile scenes and fair,

More brilliant skies and sunnier shores

A warmer, balmier air.

But happy in our snow-clad Isle

No Ministerial band,

No Foreigner, shall drive us forth

Our home in Newfoundland.

We’ve given the Frenchman bait to fish

To which he has no right,

And given him a friend’s right hand,

And help him day and night.

But he! - ungrateful, in the dark

Has sought our ruin now;

Would steal our bait, our land, our fish,

And starve our children too.

Yet worse than guileful Frenchmen, come

Our own to lay us low,

Bid us forsake our cherished home,

And force us thence to go.

Yes! Britain’s power destroys our Rights,

By fools or traitors led,

And yields to grasping foreigners

Her distant children’s bread.

But up Newfoundland’s hardy sons!

And shout to England’s Queen!

And to the British Parliament!

That ever stood between

Th’oppressor and th’oppressed of yore

Nor will desert us now;

For never to the Tri-colour

The British flag shall bow.17

Newfoundland is presented here as a cherished homeland, threatened by the French on the one hand and on the other by British politicians – the "Ministerial band" and "fools and traitors". The remedy lay in an appeal to the Queen and Parliament, who would surely prevent such an abject betrayal of the rights of British subjects. This tension between an imperial desire to negotiate a settlement to a minor yet dangerous dispute and loyal colonial nationalists determined to stand up for the colony’s rights as they saw them was to last until 1904 and cause serious tensions and difficulties.

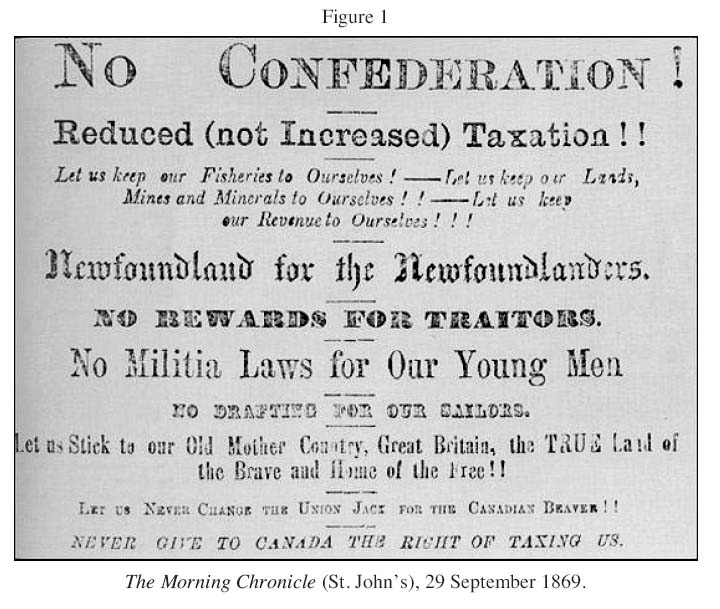

15 The second event that helped cement Newfoundlanders’ sense of identity was the loud and divisive debate over Confederation in the 1860s. Nativists and nationalists split, and it is important to note that Newfoundland nationalism has never been synonymous with hostility to Confederation. Frederic Carter, the native-born confederate leader in the 1860s, and Joseph Smallwood, his successor in the 1940s, both saw themselves as nationalists – Carter would have used the word "patriot" – and saw no contradiction in also promoting Confederation. The majority of natives and nationalists were anti-confederate, however, and they carried the day in the 1869 general election that was, in effect, a referendum on Confederation (see figure 1).18

Figure 1 : The Morning Chronicle (St. John’s), 29 September 1869.

Display large image of Figure 1

16 Another point is that the Confederation debate seems to have solidified a deep suspicion of Central Canada – not, it should be noted, of the Maritime Provinces, with which Newfoundland had many connections. There was a deep and understandable suspicion that Confederation was a central Canadian project that had little if anything to offer Newfoundland. After all, Newfoundland had not been invited to send representatives to the Charlottetown Conference and, in effect, invited itself to the Quebec Conference of 1864. The dominion envisaged by the "Fathers of Confederation" included Newfoundland only as an afterthought. Beyond this, there was a popular sense that Central Canada was a foreign and threatening place whose imperial agenda would drive up taxation, dislocate trade, cause friction with the United States and promote sectarian strife. If Newfoundland was emerging from the British imperial yoke, as the 1857 crisis seemed to show, then why substitute another one?

17 Third, the anti-confederates stressed and underscored the traditional nationalist line that Newfoundland possessed the human and natural resources to sustain a viable political independence within the British Empire. At the very least, the colony should make the attempt rather than give up, a mere 15 years after the grant of responsible government, to become, as one anti-confederate put it, "the outharbor of another province".19 The anti-confederates were the optimists, the confederates the pessimists; but both, in their own ways, were nationalists.

18 During the late-19th century Newfoundland nationalism became more firmly articulated. In the absence of any significant amount of immigration, nativism became muted while unifying themes emerged that helped to define what it was to be a Newfoundlander. In part this resulted from the country becoming more unified through the agency of improved communications with the building of the railway, more roads and the extension of the telegraph and coastal steamers. There was a lively press in some outports as well as in St. John’s and literacy levels improved, if unevenly. Loyalty to Britain and the empire became even more stridently expressed than earlier in the century, in spite of the French Shore dispute, particularly at the jubilee celebrations of 1887 and 1897 and during the Boer War. The interpretation of Newfoundland’s history first articulated by the reformers of the 1820s was codified and elaborated in D.W. Prowse’s monumental History of Newfoundland, first published in 1895, which became the country’s secular bible and later a leitmotif in Wayne Johnston’s novel The Colony of Unrequited Dreams. What was added to the mix at the end of the century, in the midst of the "new imperialism", was a repeated insistence that Newfoundland was Britain’s "oldest colony", "the cornerstone of Empire", the place where the British Empire began when Zuan Caboto (John Cabot) and his hearty West Country crew sighted Cape Bonavista and took possession of the island for Henry VII. Moreover, the migratory fishery that resulted had trained the mariners who crewed the ships that made the empire possible. In some formulations, there would have been no empire but for Newfoundland. In 1902 Robert Bond claimed that it was in Newfoundland that "was laid the foundation of the great empire of which we are so proud today. . . . It is Newfoundland that has made all the other colonies possible. If it was not for the training that was vouchsafed there, and the men of iron that we raised on that rugged shore, we would have had no other colonies today".20 Hence one of the features of the 1897 celebrations was laying the foundation stone of Cabot Tower on Signal Hill in St. John’s, which has since become an important if not iconic landmark.21

19 Robert Bond is, of course, the second neo-nationalist icon on which this paper depends. Born in St. John’s in 1857, he was an active politician for 32 years, from 1882 to 1914 and premier from 1900 to 1909. The Robert Bond cult, if it can be called that, is nothing new. He was seen by many as his country’s potential saviour in the dark years following the Great War, and no other pre-Confederation Newfoundland premier or prime minister has attracted so much retrospective interest.

20 Bond commanded respect in his lifetime because of his undoubted ability, probity and patriotism, and in retrospect he can certainly be presented as the embodiment of what was best in the Newfoundland nationalism of the early-20th century. He was an imperial loyalist (though less fervent on that score than some of his contemporaries), a hardliner on the French Shore issue, shared the prevailing Prowsian view of his country’s history and, like other nationalists before him, held it as an article of faith that Newfoundland was rich in resources waiting to be discovered and developed. He championed the building of the railway across the island between 1881 and 1897 so that the "vast hidden resources" of the interior could be made accessible. He was unenthusiastic about Confederation, though not unwilling to consider it. His preference was for an independent reciprocity treaty with the United States, which he attempted twice – in 1890 and 1902. This would, he hoped, provide new markets and new investment (see figure 2).22

21 He has also commanded respect because he "stood up for Newfoundland", a quality Newfoundlanders like in their premiers. He was not afraid to disagree with the Canadian and British governments, nor to take on powerful business interests such as the Reid Newfoundland Company or the fishing interests of Gloucester, Massachusetts. This is not to say that he was always right or that his judgement was always sound, but even his political enemies accepted that he acted in what he perceived to be his country’s best interests.

22 While these qualities make Bond attractive in retrospect, he is also associated with a period in Newfoundland history, the early years of the 20th century, when the country was relatively prosperous and self-confident. He became premier in 1900 as the long recession of the late-19th century was lifting. Prices rose, and there was a sense of economic confidence – a feeling that the country had turned the corner. The railway’s main line was complete, ferries plied the Cabot Strait, the forest industry was expanding and St. John’s merchants were showing an uncharacteristic willingness to invest and diversify. The colony’s finances were stable and the debt manageable. The future looked good, especially if a reciprocity treaty could be achieved, and, remarkably, the French Shore issue came to an end in 1904 with the entente cordiale, removing any uncertainty that remained about access to the resources of the west coast. In 1905, the Bond government signed an agreement that would lead to the building of a newsprint mill at Grand Falls, the first major industry in the island’s interior and a tangible justification for the building of the railway. Writing in the newly founded Newfoundland Quarterly in 1904, E.P. Morris (the minister of justice) stated that a returning exile would be struck by "the contrast between the country he left and the country he is now visiting. Not even Canada can boast of greater strides than Newfoundland since 1890. . . . The country has been opened up. Our vast wealth in minerals, timber and fisheries, has become known, and is being developed. . . . Our people are employed. . . . The earning powers of our people have increased twofold. No man need now be idle".23 An editorial in the same journal associated the prosperity directly with Bond himself.24

23 On the cultural side two anthems appeared.25 The Roman Catholic bishop, Michael F. Howley – a native, a nationalist and a confederate – wrote a hymn in praise of the Pink, White and Green, The Flag of Newfoundland:The pink the rose of England shows,

The green St. Patrick’s emblem bright,

While in between the spotless sheen

Of Andrew’s cross displays the white.

Hail the pink, the white, the green,

Our patriot flag long may it stand

Our Sirelands twine their emblems trine

To form the flag of Newfoundland.26

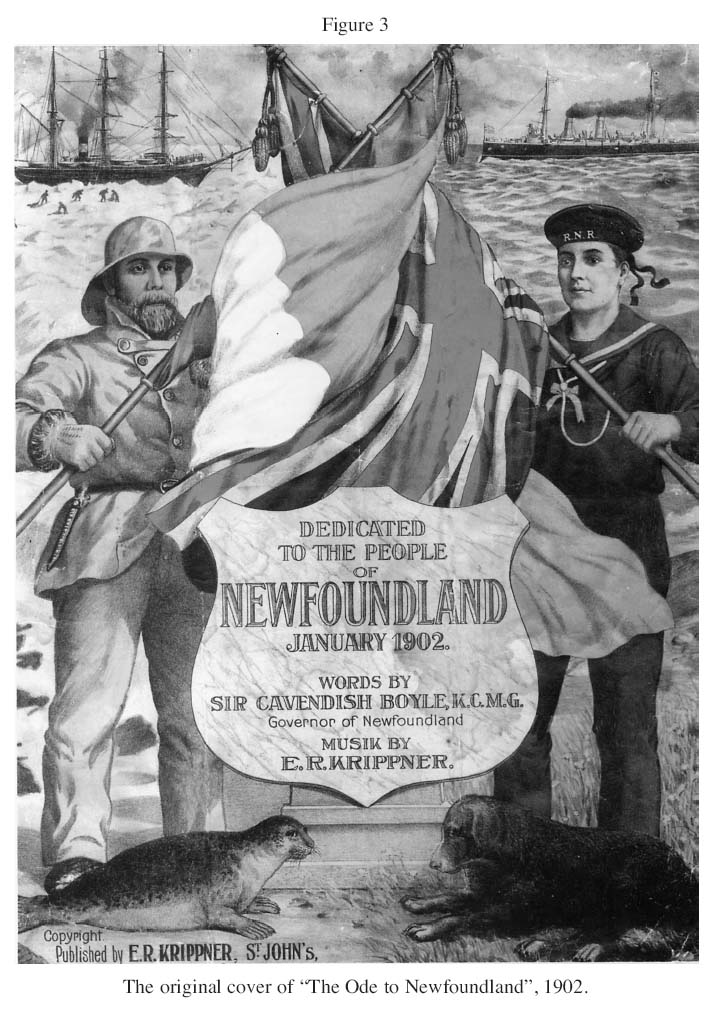

It was first performed on St. Patrick’s Day in 1902, which no doubt further reinforced the impression in some quarters that the PWG was a Catholic flag.27 That same year the governor, Sir Cavendish Boyle, wrote the less strident, indeed neutral Ode to Newfoundland, which celebrates the seasons and a generalized past (i.e., "As loved our fathers, so we love/Where once they stood we stand") (see figure 3).28 Both songs were received with great enthusiasm and with displays of the PWG and the Union Jack. Though Bond opted for the Ode as the country’s unofficial anthem, Howley’s Flag of Newfoundland was widely popular in its day and the PWG was commonly flown. It seems to be true as well that Captain Bob Bartlett, a good Methodist from Brigus, carried a PWG flag with him in 1909 when he accompanied Peary almost to the North Pole.29

Display large image of Figure 2

24 The museum building, which Bond’s government erected in St. John’s, incorporated into its facade a frieze depicting miners and loggers flanking a fisherman presenting a codfish to Britannia, with Mercury looking on.30 Contemporary Newfoundland postage stamps of the period depict similar themes of progress, diversification and prosperity. Indeed, the colonial nationalism of this period was mainly articulated in terms of progress towards a prosperous future. There existed, at the same time, an antimodern strain of nationalism that idealized the outport way of life. Early issues of the Newfoundland Quarterly contain frequent articles about "the good old days", reminiscences and verses of dubious quality with titles such as "Our Fisher Folk" or "The Sailor Race". Nostalgia was the obverse of progressive boosterism: the past was being left behind, but it should not be rejected out of hand if only because that past had produced the sturdy Newfoundlander – the backbone of the race. Quarterly articles feature such phrases as "perseverance and hardiness", "bold and fearless"and "hospitable, kind and ingenious". Sealing was particularly important as a totemic activity. The popular heroes of Newfoundland society were the successful sealing captains, their crews and renowned "fish killers". Participation in the seal hunt was a manhood ritual, evidence that a man was tough and could "take it". In 1889 the governor’s wife, Lady Blake, noted with astonishment that returned sealers were regarded with admiration and might "be seen walking with respectable-looking women evidently proud of the escort of their greasy cavaliers".31 A reply of sorts came in a song written circa 1918:Nice folks may perhaps laugh at us

But they don’t understand

That the boys in oily jumpers are

The pride of Newfoundland.

In these texts the "real" Newfoundland is outport, rural Newfoundland and its inhabitants are the real Newfoundlanders.

25 The Newfoundland nationalism that flowered in this period therefore stressed Britishness and imperial loyalty, proclaimed with pride that Newfoundland was Britain’s oldest colony and the cornerstone of empire, preferred political independence to Confederation, drew great pride from the sturdy and manly qualities of its fishermen and sealers, and emphasized that a Newfoundlander was quite distinct from any mainlander. It was also a nationalism infused by a consciousness of a long and difficult history whose legacy had, finally, been overcome; with some pride, Newfoundlanders could confidently face the future. In later years, Bond came to be closely associated with this pre-war age and to be seen as the embodiment of what was best in it.

26 It was a nationalism that drew no plaudits from Richard Jebb in his well-known 1905 book Studies in Colonial Nationalism. Jebb did not visit Newfoundland, but this did not prevent him from stating that an "attitude of doubtful insularity and unambitious colonialism has become inbred". He went on to pronounce that the colony’s "embittered memory of imperial neglect has sterilized the conception of imperial obligation", expressed through allegedly irresponsible actions that harmed the wider empire.32 It was as if Tasmania had refused to join the Australian Commonwealth. This very much reflected the contemporary view in Ottawa and London, where Bond was viewed as an insular nuisance. Jebb failed to see, however, that even if Newfoundland was a minor player in the imperial league, its nationalism in this period was typical of other colonies of settlement. Ronald Hyam has defined colonial nationalism as "a qualified and ambiguous force, a local patriotism seeking self-rule and self-respect, but unwilling to break links with the Mother Country".33 Thus, like other colonial leaders of his day, Bond was wary of "big empire" and did not support Joseph Chamberlain’s calls for a greater degree of imperial unity and cooperation. He was, for instance, not much interested in imperial preference. His concern was to guarantee Newfoundland’s status in the empire, telling the legislature in 1903 that he had worked "to secure for this colony that dignity, recognition and right that had been accorded to the other colonies of the Empire".34 In the end, though, when Bond confronted the imperial government over reciprocity and American fishing rights in Newfoundland waters, he found that imperial agendas always prevailed – certainly so far as Newfoundland was concerned.

Figure 3 : The original cover of "The Ode to Newfoundland", 1902.

Display large image of Figure 3

27 That confrontation was also politically damaging at home, and in 1909 he lost the government and became an unenthusiastic leader of the opposition until his resignation in 1914. The general mood of optimism survived his defeat and continued into the Great War, which proved to be a crucial watershed. The Newfoundland Regiment served with distinction and the colony’s war effort was noteworthy. Newfoundlanders took great pride in what had been accomplished, and the image of "The Fighting Newfoundlander" entered the nationalist pantheon. The regiment’s greatest tragedy – the slaughter at Beaumont Hamel on 1 July 1916 – became part of Newfoundland’s collective historical memory because the engagement seemed to exemplify key Newfoundland characteristics: bravery, determination, toughness and, above all, loyalty. Moreover, with this noble imperial sacrifice under the Union Jack 1 July became, as it still is, Memorial Day when, instead of poppies, Newfoundlanders used to wear forget-me-nots.35 As a result, the Pink, White and Green was eclipsed and flown much more rarely after the war than it had been before.

28 How far Beaumont Hamel was the Newfoundland equivalent of Vimy Ridge for English Canadians, or Gallipoli for Australians, is a matter for debate. There are certainly similarities, but it cannot be said that either Beaumont Hamel, or the Great War experience in general, created a Newfoundland identity. Nor did it become – in the long run – a defining element in the national mythology. The identity was already there along with a national mythology, which the war served to confirm and strengthen. Newfoundland was not a country with large numbers of new immigrants like other dominions nor was it a relatively new political entity like the Commonwealth of Australia, which had been formed in 1901. For New Zealand, the Boer War seems to have been a defining moment. Nevertheless, for the first time Newfoundland was seen to be playing an active role in imperial affairs and to thus have gained in status. Its prime minister was included in the Imperial War Cabinet, for instance, and attended the opening of the peace conference at Versailles. The country also adopted the title "dominion" and appointed a high commissioner in London.

29 But status was one thing, stature another. Newfoundland was sidelined at Versailles. It did not sign the treaty or join the League of Nations, and its government did not complain. Nor did Newfoundland make any effort to assert itself in imperial or external affairs during the 1920s. Instead, Newfoundland turned in on itself accepting that, if it was a dominion, it was a second-class dominion that hardly deserved a seat at imperial conferences. When the Statute of Westminster was debated locally in 1931, a major theme was Newfoundland’s need to draw even closer to the mother country – to increase rather than lessen its dependency; when, in the same year, the government of the day proposed that the country’s official flag should be the Union Jack, there was universal acquiescence.36 The PWG was not mentioned either in the legislature or the press.

30 The war might have been a source of great pride, but it had destroyed the confident, optimistic nationalism of the pre-1914 years. Not only had many lives been lost and damaged, but the country now carried an inflated national debt. The economic situation was gloomy and hostile, the politics unstable. Newfoundlanders faced the future with pessimism, and uncertainty took hold as to whether the country could survive as an independent political entity. Many thought that the only person who might be able to stop the country’s decline and fall was Sir Robert Bond, living the life of a recluse in his house at Whitbourne, some distance outside St. John’s. He considered returning to public life, but eventually refused to do so – much to the disappointment of supporters who viewed the present and future with increasing hopelessness and disgust.

31 Bond died, amidst these grey and difficult years, in 1927. Remarks in the press and legislature stressed his honesty, industry and disinterested patriotism – he had been a statesman rather than a mere politician. "No man in Newfoundland", said the Daily News, "is held in more general esteem, affection and admiration by the great majority of his contemporaries".37 Similar comments were voiced by a number of the witnesses who gave evidence to Lord Amulree’s Newfoundland Royal Commission in 1933, created by the British government to investigate the country’s financial crisis and its future. Bond’s defeat in 1909, the commissioners were told, was the beginning of the end. After he was gone, the standard of public life began to decline along with the quality of the political elite and the country descended into chaos.38 By the early 1930s, then, the PWG had disappeared and Bond had been established in the national consciousness as a patriotic statesman presiding over a golden age – a statesman who had been driven from public life by the machinations of venal enemies who had then proceeded to bankrupt the country and who had (some would add later) allowed the British bailiffs to take over, establish the Commission of Government and arrange Confederation with Canada.

32 That this idealized picture of Bond still lingers in the Newfoundland historical consciousness has something to do with Joseph Smallwood. During the late 1930s and early 1940s Smallwood, then a journalist and broadcaster, took it upon himself "to restore the faith of Newfoundlanders in their country" and to promote an inclusive nationalism. He did this through the volumes of his Book of Newfoundland and a newspaper column and radio programme known as "The Barrelman", both of which were enormously popular.39 He retailed a mix of history and folklore, designed to instill pride and self-confidence. Newfoundlanders were presented as tough, resilient, sturdy, ingenious, hard-working and the product of a common historical experience characterized by struggles "against the forces of nature, against oppression and injustice and intolerance and bigotry". Their country had "vast undeveloped resources" and a proud past. He spoke about his heroes as well: William Coaker, the founder of the Fishermen’s Protective Union, and Robert Bond, whom he called "the greatest patriot of all". These were all traditional themes. Interestingly enough, he made it clear that he did not favour the PWG on the grounds that it was not a truly national flag. Philip Hiscock thinks that this was because Smallwood was an Orangeman and therefore saw the PWG as a Catholic emblem. In any event, Smallwood was not much interested in symbols or institutions; at this stage, his was a nationalism founded on the qualities of the people.40

33 Smallwood’s cultural enterprises in this period were sponsored in part by St. John’s businessman F.M. O’Leary, who was closely associated with "The Barrelman". Another important influence was Gerald S. Doyle, who collected Newfoundland folk songs and published them in free, widely circulated songsters (songs interspersed with advertisements for the products he sold to retailers around the island). The first Doyle songster was published in 1927.41 This was also the period when professional folk song collectors first came to Newfoundland from England and the United States, and there is evidence of a growing interest in local song and folklore even as the Commission of Government unforgivably closed Bond’s Newfoundland Museum and dispersed its contents.

34 It was the Doyle songbooks that established the modern Newfoundland folk song canon, made these songs popular in middle-class urban drawing rooms and reinforced the idealization of the outports as the "real", "authentic" Newfoundland. The songsters were selective in that they popularized comic "ditties" rather than the lengthy ballads encapsulating local history and tradition that, arguably, are at the heart of the Newfoundland folk song tradition. Hence the easy popularity of such songs as "I’se the B’y", "Lukey’s Boat", "Feller from Fortune" and others, which were among the first to be commercially recorded. Neil Rosenberg argues that, as a result, mainland Canadians in the 1940s were presented with a stereotype.42 At the ceremonies in Ottawa marking Newfoundland’s entry into Confederation in 1949 the Peace Tower carillon did not play the "Ode to Newfoundland", which would have been appropriate, but "The Squid Jigging Ground" by Arthur Scammel – a comic song about outporters’ antics on the water. Canadians were therefore introduced to their new fellow-countrymen and women as simple, hardy, fun-loving fisherfolk. Many still hold this view, if the results of a survey carried out for the Royal Commission on Renewing and Strengthening Our Place in Canada (2003) are to be believed. The survey demonstrates the prevalence of inaccurate stereotypes and an enormous ignorance about the province, which increases from east to west.43

35 This is a roundabout way to come to the issue of Confederation and the bitterly fought Confederation wars that preoccupied Newfoundlanders between 1946 and 1949. Both confederates and anti-confederates, as in 1869, thought of themselves as nationalists. Smallwood and his allies saw no reason why joining Canada should pose any cultural threat. His opponents took the opposite view and argued for the importance of political autonomy. Smallwood won, became premier and presided over what he himself called "a democratic dictatorship" for 22 years.44 He never lost his interest and enthusiasm for Newfoundland history and culture, however, and actively promoted it through the foundation of Memorial University among other initiatives. But, at the same time, Smallwood was a modernizer; 1949 was year one in the new dispensation, and it was his job to bring about a "New Newfoundland", the title of a book he had published in 1931, with the help of the federal government and outside investors wherever he could find them.45

36 Newfoundland and Labrador changed a great deal after 1949, and there was initially little overt discontent with the performance of the Smallwood government. Indeed, in spite of various and expensive blunders and pitfalls, the 1950s and 1960s constituted a period of optimism, as in the Maritimes, and the Centennial Year (1967) showed that if Newfoundlanders were not yet emotionally tied to Canada, they were satisfied with the status quo and had great hopes for the future.46 The mood soon changed. Ottawa’s generosity faded and the financial situation became more difficult. Beyond this there was a growing realization that, although standards of living had risen dramatically, the provincial economy still remained vulnerable. Unemployment remained stubbornly high, the Churchill Falls project turned sour and there was increasing frustration with Ottawa’s handling of the fisheries and other issues. Smallwood’s expensive megaprojects caused concern, and the relocation of the rural population under the resettlement programmes seemed to constitute an attack on the "real" Newfoundland – the traditional society of the outports. Once revered (or feared), Smallwood was now becoming the subject of both criticism and ridicule. The charge was that he had failed to do what he had promised, which was, in essence, to modernize the province while at the same time strengthening its economy and preserving its culture and heritage.

37 It was in this context that the modern nationalist movement took root, for the most part within the educated middle class that emerged after 1949.47 Britishness and imperial loyalty were no longer factors, at least among the younger generation, so this was a neo-nationalism that defined itself within the context of Confederation. Yet according to a 1978 survey of members of the elite only 57 per cent saw themselves as Canadians first (compared to 80 per cent in Nova Scotia), and many of that small majority of respondents had qualifications. This neo-nationalism stressed the distinctiveness of Newfoundland and Labrador and celebrated traditional customs, songs, dialects and artefacts as well as the province’s history and landscape. There was an emphasis on "small is beautiful" while the "develop or perish" policy followed by politicians since 1949 came under fire. Artists, writers, actors and academics participated in what has been called, perhaps pretentiously, a Newfoundland renaissance. There was romanticization, certainly, especially an idealization of the rural, but there was also a new willingness to satirize, criticize and poke fun. And if there was an antimodern, nostalgic streak in all of this, there was still some optimism in the 1970s that a prosperous future might be based on the fisheries, Labrador power and offshore oil and gas. In some respects it was, ironically, Smallwoodian in the Barrelman sense. The members of CODCO, the Mummers Troupe and others like them were not separatists. Their role was to remind fellow Newfoundlanders and Labradorians, and all Canadians, that their province was a distinct and special place with a proud and unique history that deserved respect rather than condescension, Newfie jokes and vicious, racist attacks from animal rights activists opposed to the seal hunt.

38 Nevertheless, as Jerry Bannister has pointed out, the neo-nationalist take on Newfoundland’s history is at heart pessimistic and has tended to revert to 19th-century themes of oppression and victimization.48 The past had been a struggle and so was the present. From this grew a determination that there should be no more federally abetted giveaways such as the 1968 Churchill Falls hydroelectric deal, an episode that haunts the province still. Hence Brian Peckford’s fight with the federal government over control of offshore oil and gas and also Clyde Wells’s contrarian attempt to prevent further devolution of federal powers and responsibilities in the belief that this would do smaller provinces no good. Hence also Roger Grimes’s attempt to get a reasonable deal on the development of the Voisey’s Bay nickel deposit, Danny Williams’s standoffs with the federal government and the oil companies, and Williams’s insistence that the hydro power of the lower Churchill must be developed on Newfoundland and Labrador’s terms. This may not be to the taste of Margaret Wente and Michael Bliss,49 but the fact remains that the electorate expects its premiers, like Bond, to stand up for what are perceived to be the province’s best interests.50

39 It was Peckford who decided that the Union Jack was no longer a suitable provincial flag. The Newfoundland Historical Society, of which Bishop Howley and Judge Prowse had been founding members, joined with other heritage groups to recommend that the PWG should be revived and adopted as the official flag.51 The government instead commissioned a new flag in 1980 from the artist Christopher Pratt. But the PWG had been resuscitated; it began to appear on t-shirts and it has since become the most obvious neo-nationalist symbol, especially since the "flag flap" of 2004-05, when Premier Danny Williams ordered that Canadian flags be taken down outside government buildings. Whatever the precise nature of its origins, the PWG is seen as an authentic Newfoundland product associated with both nativism and independence. It has become a badge of pride, defiance and identity, and is probably more widely flown now than at any time in the past. A nationalist historian, writing in the local press, has stated that the flag reminds people of "the greatness of our past and the potential of our future. It reminds us of . . . the greatness of Bond and Bartlett".52 It is worth noting, though, that only 25 per cent of those polled favoured adopting the PWG as the provincial flag, with the heaviest support coming from St. John’s and the east coast. Danny Williams expressed surprise.

40 Nevertheless, the flag is back and also, to a lesser extent, is Bond. The revival of interest in his career is a minority taste but, like the revival of the PWG, it speaks to a degree of disillusionment with what Confederation has brought or has failed to bring to Newfoundland and Labrador. Pessimism is again abroad in the land, for even as oil revenues prop up a hugely indebted provincial government and provide a degree of prosperity in the southeast, rural Newfoundlanders are packing their bags and heading west. Their houses are either boarded up, homes for temporarily single mothers or vacation retreats for townies and non-residents. There is a pervasive sense of powerlessness and, not surprisingly, contemporary discussion often goes back to the 1940s and Joe Smallwood (who is now viewed with considerable ambivalence) and, beyond him, to that brief, allegedly halcyon period of Edwardian prosperity and confidence when Bond and the PWG held sway.

41 From the beginnings of Newfoundland nationalism to the present, certain themes persist. There is faith in the potential of rich natural resources, albeit a faith that is severely dented these days by the fisheries crisis, problems in the forest sector and the difficulty of regulating multinational corporations. There is also faith in the sterling virtues of Newfoundlanders and Labradorians, even as they leave for Alberta and points west via ferries and planes, as well as pride in the province’s history and culture. Finally, there is friction with an imperial centre (once London, now Ottawa) and a tendency to look for external scapegoats. It was always a defensive nationalism as well, quick to take offense, and resentful of actual and perceived slights. Jerry Bannister is right to point out a major difference between the nationalism of Bond’s day and that of the present.53 Bond’s was an optimistic vision while today’s Newfoundland nationalism is haunted by the past and by dreams about an imagined world that has been lost – a world encapsulated in widely popular images of idealized outports complete with mummers and of an old St. John’s where poles and wires have miraculously disappeared and every house is newly painted.54 It is a nationalism that debates endlessly whether the right decision was taken in 1948 and hopes that a better deal within Canada might just happen. This is a remote possibility, perhaps, in which case the role of culture, history and heritage, and the PWG, become all the more important in cementing a sense of purpose, place and identity.

JAMES K. HILLER

Figure 4 : The Pink, White and Green at half-mast on Signal Hill, St. John’s, April 2005. Photo courtesy of Paul Daly and The Independent.Notes