Erecting "an instructive object":

The Case of the Halifax Memorial Tower

Paul WilliamsQueen’s University

Abstract

In 1912 the Halifax Memorial Tower was unveiled to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the first "representative government" in the British Empire – in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1758. Unlike most monuments of its time, it did not celebrate great men, important battles, the monarchy or colonization. Instead, it was meant to mark a political moment in the nation’s past and to valorize the ongoing democratic process in the newly confederated Dominion of Canada. In this sense, it was as much a symbol of progress as it was a monument to past glories.Résumé

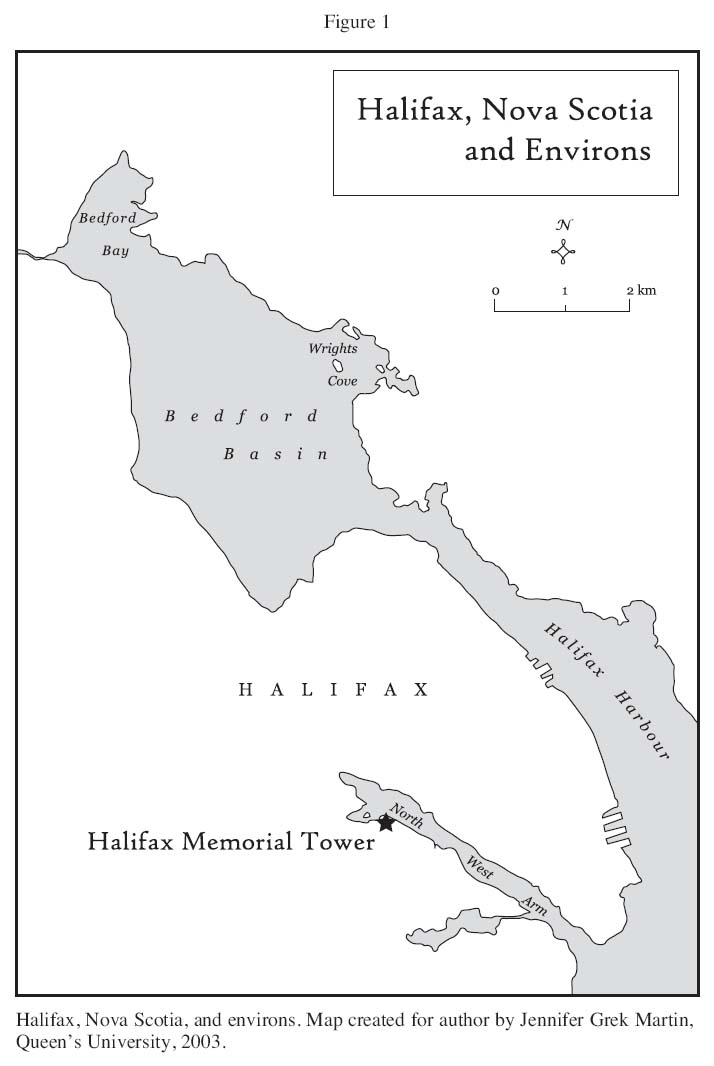

La tour Memorial, de Halifax, a été dévoilée en 1912 pour commémorer le 250e anniversaire de l’avènement du premier « gouvernement représentatif » au sein de l’Empire britannique, à Halifax, en Nouvelle-Écosse, en 1758. Contrairement à la plupart des monuments de cette époque, elle ne rendait pas hommage à de grands hommes, à des batailles importantes, à la monarchie ou à la colonisation. Elle visait plutôt à souligner un moment politique du passé de la nation et à valoriser le processus démocratique en cours dans le Dominion du Canada nouvellement confédéré. En ce sens, elle était un symbole de progrès tout autant qu’un monument à la gloire du passé.1 ON 14 AUGUST 1912, THE CITIZENS OF HALIFAX, Nova Scotia, gathered along the shores of the city’s Northwest Arm for the official unveiling of a commemorative monument, a memorial tower built to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the establishment of the first representative government in Halifax and in the British empire (see figure 1). It was to be a triumphant moment, guaranteed to display the city and its ocean playground to an international audience. Local newspapers remarked that the occasion had been "memorable . . . in [the] History of Halifax", and that the ceremonies had been "an event that will live long in the memory of Haligonians".1 Other reports waxed, with even greater eloquence: "The long awaited moment has come – and gone, as all moments, however full, however historic, must. The welcomes have been given – the Memorial Tower dedicated, and the ‘murmuring pines’ of the Arm left to their murmuring – but those wooded shores will in our memory always be peopled with royal presences and we shall see to it that our boys and girls learn well upon what strong foundation rests loyalty to the throne and of what a strength are the links in the chain of Empire".2

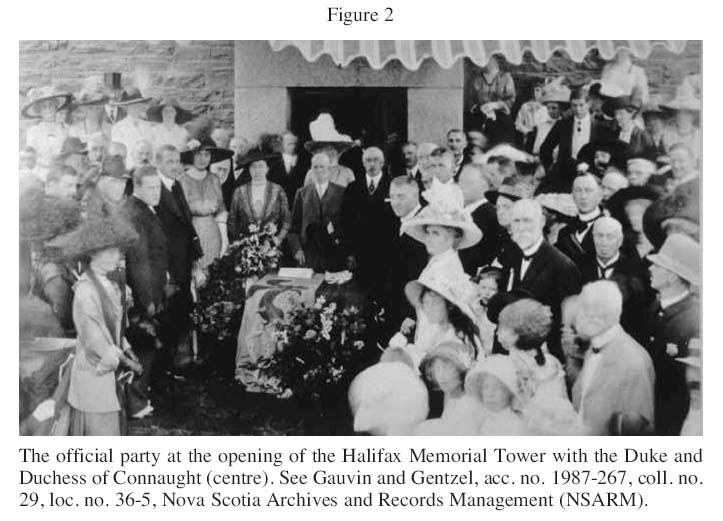

2 Despite such sentiments, the Halifax Memorial Tower and the spectacle of its opening by His Royal Highness the Duke of Connaught (see figure 2), have today slipped from the collective memory of Haligonians.3 The fascination with the monument and the festivities surrounding its opening lay in the commemorative fervour that marked the fin de siècle – a period of invented tradition, monumentalism, antimodernism, nationalism and imperialism.4 In many ways, the tower highlighted a nostalgia for times past: a recognition of the deeds of great men, a grounding of national history, a notion of continuity in that historical process and, some might argue, a reaction against modernity.5 The rhetoric that surrounded its construction, however, also reflected the fascination of its builders with progress and, in particular, with the advancement of the Canadian nation within the empire. Indeed, an emphasis on turn-of-the-century antimodernism risks blinding "us to the multi-faceted, simultaneously progressive and nostalgic appeal of monuments and structures".6 The dichotomy of this relationship is apparent in the Halifax Memorial Tower as it represented both a contemporary, fin-de-siècle commentary on progress and a particular vision of empire (espoused by the likes of Sir Sandford Fleming) as well as a commemoration of a mid-18th-century landmark event that set in motion Canada’s political developments.

Figure 1 : Halifax, Nova Scotia, and environs

Display large image of Figure 1

3 Such an analysis of a commemorative monument is by no means novel.7 However, unlike the majority of other monuments of the time, the Halifax Memorial Tower was not erected to celebrate great men, important battles, the monarchy or colonization. Although these were all ideas that were integrated into its design, it was primarily intended to mark a political moment in the nation’s past and to valorize the ongoing democratic process in the newly confederated Dominion of Canada. In this, it was unusual. Similarly, the representation of history and historical moments in the material form of a memorial tower, while not unique, was not common.8

4 A brief recounting of the historical circumstances that led to the first Nova Scotian House of Assembly in 1758 is useful for placing the events of August 1912 in their proper context. The establishment of a representative government in Halifax was not an easy task.9 From its beginning, the colony had been a political venture intended to establish a permanent British presence in Nova Scotia. In the early years, power to govern rested with a military governor despite the fact that the commission of King George II had pronounced that governance was to be undertaken by the governor "with the advice and consent of our said Council and Assembly or the Major part of them respectively".10 Nevertheless, while Edward Cornwallis, the first governor of the colony, had put in place a council of 12 men, he deemed the conditions to be not conducive to the establishment of an elected assembly.11 For the next nine years, conflict with France, the threat of Indian raids, a dispersed "British" population in Nova Scotia and the procrastination of successive governors all helped to mitigate against the election of an assembly.

Figure 2 : The official party at the opening of the Halifax Memorial Tower with the Duke and Duchess of Connaught (centre).

Display large image of Figure 2

5 Pending a challenge from civilian representatives, it was evident that power would remain in the hands of the governor and his appointed council. This challenge eventually came from an increasingly powerful and vocal New England merchant class in Halifax. In this, they found an ally in the board of trade, which had been dissatisfied with a government that lacked a public presence. Moreover, they questioned the passage of laws without the consent of a public assembly.12 Matters came to a head during the tenure of Governor Charles Lawrence and, in 1754, Chief Justice Jonathan Belcher was given the tasks of enquiring as to the delay in implementing an assembly and whether or not legislation being passed by the governor and council alone was legal.13

6 Belcher failed to deliver on the legal question claiming that, in his opinion, as a conquered colony it was the prerogative of the King’s representatives to govern on his behalf as they saw fit. In April 1755, however, the legal officers of the Crown sided with prevailing public opinion noting that, although Nova Scotia was a conquered colony, by virtue of the promise of a public assembly in the governor’s commission and instructions an assembly was required under law.14 Such a promise, they noted, could only be rescinded by Parliament. Belcher was therefore ordered to consult with Lawrence in drawing up a scheme for a workable assembly. Consequently, a plan calling for an assembly of 12 men drawn from the province at large was submitted by Lawrence to the board of trade. Appended to it were indications of his opposition to the scheme and, presumably, to the loss of his official power.15 Lawrence’s protestations notwithstanding, the board concluded that it would be a greater "inconvenience and evil" not to have laws enacted by a proper authority. After yet another lengthy delay, the New Englanders delivered a petition to the board which, upon its receipt, called for an assembly to be formed posthaste. On 20 May 1758 the council set a date, and on 2 October 1758 the first elected assembly of 19 men met in Halifax as representative government within the British overseas colonies was born.16

7 Although the Halifax Memorial Tower was built during the early years of the 20th century to commemorate this establishment of the first representative government in Halifax and the empire, much of the story of the building of the tower and the events of 1912 reflect the character of the time and of its author. While Dougald Macgillivray and the Canadian Club of Halifax were chiefly responsible for seeing the project through to its completion, the tower was the brainchild of Sir Sandford Fleming. As such, it reflects not only his patriotism but also his strong beliefs in the past virtues as well as the future prospects of the Dominion and the British Empire. An ardent imperialist, Fleming supported the notion of a federation of imperial countries in which, it was believed, Canada would come to play a leading part. In this respect, Fleming kept company with many of the foremost "imperial federalists" of the day, including George Parkin, Stephen Leacock and George Taylor Denison.17 As with those other supporters of imperial federation, he was also a nationalist.

8 Fleming rose from a modest background in Scotland, where he had first trained as a surveyor and draughtsman, to play a role in the establishment of much of the railway system in Canada.18 His years in the employ of the railway companies with his travels across the country had given him an unique perspective into its character and history, and he also came to realize the difficulties inherent in uniting such a broad dominion and the vital role that communications and transportation would come to play in nation-building.19 His influence in these matters was considerable and extended beyond the bounds of Canada: Fleming’s foresight and tenacity brought about the world-wide adoption of Standard Time and prompted the establishment of a maritime cable system that eventually came to connect all corners of the British Empire. This "all red line", he argued in 1906 before the Eighty Club in London, would allow for the establishment of an "Imperial Intelligence Service . . . for disseminating useful knowledge throughout the Empire for the mutual enlightenment and mutual advantage of all classes in each separate community".20

9 Although it never took shape, the latter plan spoke volumes for Fleming’s desires both to unite people in a common cause and to disseminate information. This same vision was to be prominent in his conception of the Halifax Memorial Tower as a marker of the significance of the establishment of the first-ever representative assembly in Halifax in 1758. While it had been superseded in the Canadian national pantheon by Confederation in 1867 and, to a lesser extent, by the advent of responsible government in 1841, it was still considered by some, such as Fleming, to mark the birth of the modern democratic system of governance in Canada.

10 That the system of representative government in the colonies had such humble beginnings appealed to all who sought to ground the national narrative in an idealized, romantic past. Such an interest in both the continuity of national history and "the foundations of national greatness" (for example, the pioneer spirit and the heroic deeds of ordinary men) was predominant in the discussions that surrounded the construction and the dedication of the tower and in the commemorative events which accompanied the sesqui-centennial of Nova Scotia’s legislative assembly.21

11 In a formal sense the events that would culminate with the opening of the Halifax Memorial Tower began on 19 August 1908 when a brass plaque, commemorating the inaugural meeting of the assembly, was unveiled in a ceremony on the grounds of Province House in Halifax. In the speeches that accompanied the proceedings much was made of the significance of the October 1758 events – not only for Nova Scotian legislative history, but also in terms of the perceived place of Halifax and Nova Scotia in the pan-Canadian narrative of nation-building and empire. Nova Scotians were quick to assert their claims to pre-eminence in the latter process and to put the Halifax commemorations in a contemporary context with the recent tercentenary celebrations in Quebec City. Nova Scotian Lieutenant-Governor Duncan C. Fraser observed:I have witnessed with wonder and delight the tercentenary memorials on the Plains of Abraham. It was empire-making in its conception, and unrivalled at least on this continent in its success. Here two great races celebrated the glory of their forefathers, the success of Great Britain and the freedom and peace that connection with our Kingdom has brought both. Historically the events commemorated were worthy of our national evolution. But I think today’s memorials are more worthy of our recognition and celebration. Here first in the great Kingdom now forming the homeland and beyond the seas men met to deliberate as a parliament on questions affecting the land in which they lived. . . . That they and all who came after them played their parts honourably, unselfishly and patriotically till the fullest responsible government became ours, none will now deny.He concluded:As a memorial of the past, an incentive to the present, and a guarantee for our future, we meet today to unveil a tablet to the first men who sat in the rude building then constituting our House of Parliament. We honour them in remembering them: we are honoured ourselves by being their imitators. I feel that no higher distinction could be mine than the honour the committee have given me of unveiling what will always hereafter in this chamber be associated with the illustrious dead, and a continued incentive to energetic living and patriotic action to us and all who come after us.22Similar allusions to the patriotism of the "illustrious dead" and to continuity with the present were made by William Alexander Weir, the representative of the government of Quebec, who paid homage to "the men of 1758, and those who followed them".23

12 Fleming was among those in attendance at the Halifax ceremony. That he had taken a personal interest in the commemoration was evident not only in his involvement with the memorial committee, but also in his interest in the legislative debate that had preceded the process. It is clear that he too had been inspired by the Quebec Tercentenary celebrations. However, he had a desire to see the events of 1758 commemorated on a much grander scale and on the actual anniversary of the assembly’s first sitting. Five days prior to the unveiling of the Province House plaque, he wrote to Fraser and stated that while such a gesture was commendable there was still ample time before the 2 October 1908 anniversary to make additional plans to "commemorate in an adequate and fitting manner, the vastly important epoch in the life of Nova Scotia and in the life of the Empire".24 He had also earlier stated to Mayor Adam Crosby that "the present year should not be allowed to pass without taking steps to erect an ornamental edifice, imperial in its character, which would embody all the great historical associations of Nova Scotia from the first assembly of representatives of the people at Halifax in 1758". "There can be no time so opportune", he continued, "as the present for moving in this matter. Last year would have been too soon, and next year will be twelve months too late".25

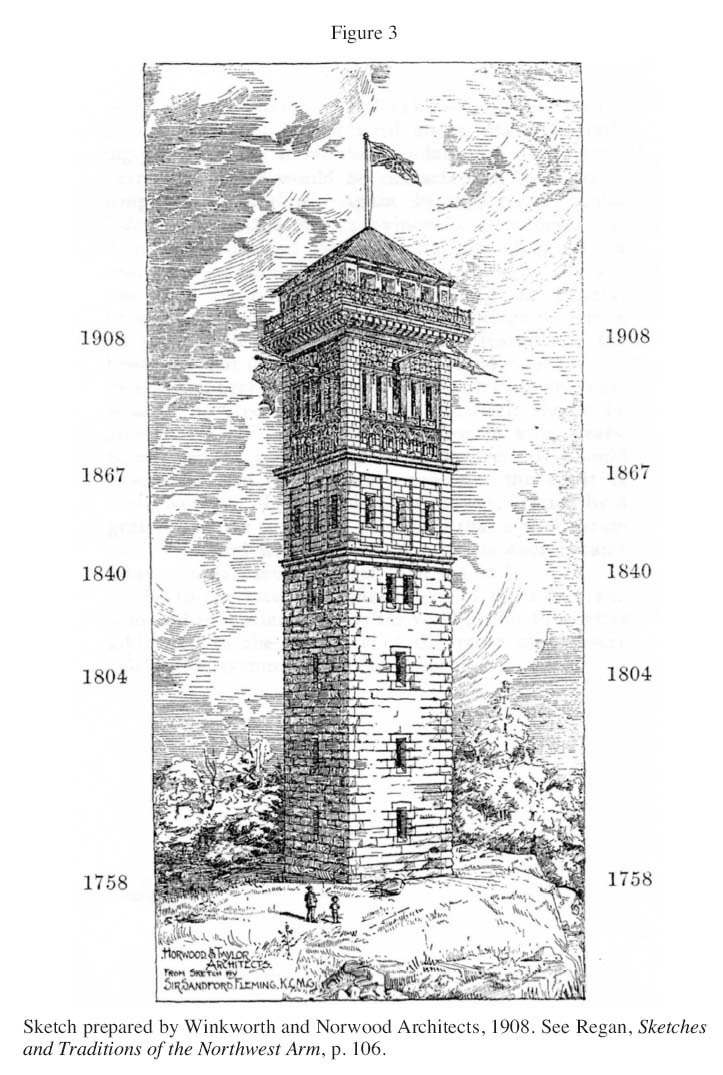

Figure 3 : Sketch prepared by Winkworth and Norwood Architects, 1908.

Display large image of Figure 3

13 In haste to get some form of commemorative process in place before the end of the sesqui-centennial year, Fleming made the donation of a portion of his land to the City of Halifax for use as a municipal park with the proviso that some form of monument be erected. He also set about designing an appropriate memorial. In his initial specifications, he suggested that "the whole structure might most fittingly, I think, take the general form of an Italian tower, probably 25 feet square and 100 or more feet in height".26 The planned "Italianate" tower was in keeping with contemporary trends in architectural design as well as those of monumental construction. In choosing his design Fleming was inspired, at least in part, by the writings of John Ruskin.27

14 The preliminary sketch plan, prepared for Fleming by the architectural firm Norwood and Taylor, shows a somewhat fanciful building (see figure 3).28 Apparent in the sketch and in Fleming’s correspondence, however, was his primary concern with the didactic value of the tower. It was to be a symbol in stone of the evolutionary development of the nation. Moreover, the stratified design was literally meant to be viewed as a text: "Each course of massive masonry upwards would have its meaning, and would be adorned by references to the deeds of distinguished men who have served their country". Consequently, the sketch included a number of key dates in Canadian and imperial history: 1758 – the date of the first representative assembly; 1804 – the birth of Joseph Howe; 1841 – the advent of responsible government; 1867 – Confederation; and 1908 – the 150th anniversary of representative government. Further, Fleming insisted that the sentiment and purpose that it was intended to convey should remain long after those involved in its construction had been forgotten:It should be the aim of the design to denote all such matters in the architectural features of the tower, so that it would strike the beholder as, even in external appearance, appropriately fulfilling the purpose of its erection. The structure itself should be able to tell its tale to the spectator in after years when present actors may be forgotten. It should practically and unmistakably proclaim the spirit of these words: "This is a birthday tower, erected by a grateful people to inform the world that a new nation was born, and with its birth the old mother became larger, nobler, more perfect than ever before".29

15 In setting out these ideas, Fleming wrote that from its massive base the structure "would gradually increase in architectural beauty until crowned by the finale".30 The foundation course was to be constructed of local granite. "A block of granite for a cornerstone", it was suggested, "typified the enduring principles of the British constitution transplanted on Canadian soil in 1758".31 A similar view concerning the centrality of the British constitution was conveyed in a letter to the lieutenant-governor: "It may indeed be regarded in its essential principle as the foundation stone upon which has been steadily developing and is today being firmly built up in both hemispheres – the British Empire of the centuries to come".32 Moreover, the proposed tower would be a clear testament to the earliest "representative" assembly.

16 Beyond the foundation course, the lower portion of the tower was meant to highlight the period of the development of the new colony, the establishment of the first assembly, the birth and death of a British hero, and the birth of a great Nova Scotian. In its massiveness and simplicity, it would represent the period between the establishment of representative government and the beginning of responsible government in 1841. In describing his plan, Fleming recorded that the meeting of the very first assembly was almost coincidental with another significant event – the birth of Horatio Nelson. In Fleming’s estimation, no man had done more for the long-term good of the empire. Furthermore, the Battle of Trafalgar, in which Nelson met his death, was seen to be a key moment in the development of Britain’s colonial power. Such developments were to be commemorated in the fabric of the Halifax tower: "Up to the date of that glorious victory, as indicated on the proposed tower, the structure might be characterized by the greatest simplicity and solidity".33

17 Historical links were not lost on Fleming, who noted that in the very year of Nelson’s death Joseph Howe, "a great man – one of the greatest which Canada ever produced", was born in a cottage near the shores of the Northwest Arm. "The upper half of the tower", he therefore proposed, would "be enriched by a reference to the grateful services to his country of Joseph Howe, a man who has done so much to render his name immortal in the hearts of his countrymen. That famous Nova Scotian has provided abundant opportunities for the architectural adornment of the tower".34

18 In his communiqué to Mayor Crosby, Fleming listed others who might be honoured within the structure: the Hon. J.W. Johnston, a major contributor to the development of responsible government; Samuel Cunard, who had established the first steam communications between Great Britain and North America; and Sir Charles Tupper, a Nova Scotian who had played a significant role in Confederation. The original design of the tower also called for the establishment of galleries "dedicated to the memory of men who have served their country": the ground chamber was to be named in honour of the British statesman William Pitt, a statue of Howe would grace a Nova Scotia Loyalist Gallery and a gallery of Canadian Confederation would contain a likeness of Sir John A. Macdonald.35

19 Fleming originally hoped that as well as galleries there would be places to record "the names and good deeds of all who had specially served their country".36 His intention was that the tower would remind future generations of Nova Scotia’s role in the transformation of the "greatest secular agency for good in the world today"– the British Empire – and of the benefits that had accrued under the latter. Moreover, the tower should remain as "an instructive object lesson . . . to foster in the minds of the youth and future generations a worthy pride in their past, and lead them to a correct knowledge of the basal elements of national greatness".37

20 In the Halifax Memorial Tower, Nova Scotia was to be portrayed as the cradle of "representative government" not only in the Canadian federation but in a worldwide context that transcended the confines of Nova Scotian and Canadian history. For its advocates, it was a symbol not only of imperialism but of "inter-imperialism" or imperial federation. In a circular from the Canadian Club of Halifax to various British imperial governments, a note was made that the import of the monument should not be limited to Nova Scotia and the Canadian dominion but that it should extend to all the "self-governing over-sea states of the Empire". "In this light", argued the authors, "the Memorial Tower will cease to be merely local or provincial, and become Inter-Imperial". They concluded that the commemoration of "one of the most significant events in history" would act to unite the citizens of the empire, if for a moment. Moreover, the tower itself would continue to act as a significant mnemonic centre. Thus its importance was perceived not just in a local or provincial milieu, nor simply within the broader Dominion of Canada. Rather, it was viewed as "an embodiment of the spirit which animates the people of the Empire in both hemispheres, an attestation of the partnership of the sisterhood of nations, all under one Crown".38

21 There is no doubt that the appeal for broad support had its desired effect. Links between the different elements of the empire were evident not only in the financial contributions of various imperial governments but also in the memorial plaques that came to adorn the inner walls of the tower. The large number of votive contributions later prompted the Duke of Connaught to refer to the tower as having been "carved from so many different portions of the empire" and Dougald Macgillivray, president of the Canadian Club of Halifax, to remark that it was hard to perceive of another monumental structure anywhere in the world that could claim to have had "the aid of so wide a constituency".39

22 Of special interest among the latter memorials are a bronze panel commemorating John Cabot’s voyages to the New World and a stone from Samuel Champlain’s birthplace – Brouage in France. The symbolic value of these pieces was seemingly not lost in the debate between Canada’s two "founding" nations as to who had first claimed sovereignty over Canadian soil; English Canada’s claims that the "Englishman" John Cabot had first landed on Canadian shores in 1497 and French Canadian beliefs that Jacques Cartier had claimed the land for France in 1534. French primacy in the national myth-history was further strengthened by the knowledge that the first permanent European settlements in Canada were established by French settlers at Annapolis Royal in 1604-5 and Quebec City in 1608.

23 Indeed, much had been made of the 1908 Quebec Tercentenary celebrations in the conceptualization of the Tower. The January 1909 "National Memorial Tower" appeal made particular reference to the latter in putting the proposed Halifax celebrations in context.40 Fleming observed that the Quebec celebrations had revived interest in the earliest "historical associations" of Champlain and the French settlements along the shores of the St. Lawrence. Further, in his opinion, the events had been "portrayed with such excellent unity of spirit, sympathetic good taste, and genuine patriotism, that all Canadians of whatever origin should now feel a new pride in the history of French Canada as a most important part of the early history of their own land".41

24 Although the validity of the position of Quebec as the birthplace of the nation was recognized by the Halifax organizers, it was always believed that the true constitutional birthplace of the nation was Nova Scotia and, specifically, Halifax.42 Fleming’s list of "Elective Legislatures and the Date of the First Assembly in Each Case" clearly sought to bolster such beliefs, placing Nova Scotia at the head of the list of self-governing countries of the British Empire that had gained constitutional freedom by authority of the British Parliament.43 "Nova Scotia", he wrote, " takes her place as the elder sister in the British Constitutional family, and the pioneer meeting of her Assembly was held at Halifax on October 2nd, 1758. At that date the Provinces of Quebec and Ontario, and much more territory stretching athwart the continent, were under the military rule of the King of France. British Columbia did not become a British colony for a hundred years later. Australia and New Zealand were unsettled and unclaimed. The Cape of Good Hope did not become British until half a century later; it was formally ceded to the British Crown in 1814".44

25 Compared to the elaborate events that marked the celebration of the Quebec Tercentenary, the ceremonial laying of the cornerstone for the Halifax Memorial Tower on 3 October 1908 was simple and austere. It was carried out "in the midst of a rain storm, in the presence of a handful of mackintoshed spectators, surrounded by dripping foliage and under the canopy of a gray sky". The heavy rain had dampened any hopes of a large gathering and, in the end, only a small number had braved the weather to cross the "Arm". Lieutenant-Governor Fraser represented the Crown and members of the press and the "public educational system" were also present han cell.45

26 Part of the ceremony consisted of the placing of a time capsule in a receptacle in the foundation stone. Within the copper box were a number of mementos, including the following: copies of the Halifax Herald, the Morning Chronicle and the Acadian Recorder for 2 October 1908; Nova Scotia Statutes for 1908; Debates of the Legislative Council and the House of Assembly of 1908; Halifax newspapers giving accounts of the unveiling of the commemorative plaque in Province House on 19 August 1908; a pamphlet by the Canadian Club referring to the proposed tower and dedication; Fleming’s first pamphlet on the proposed tower; the constitution of the Canadian Club; and a dime that was deposited by the builder Mr. Brookfield "for good luck".46

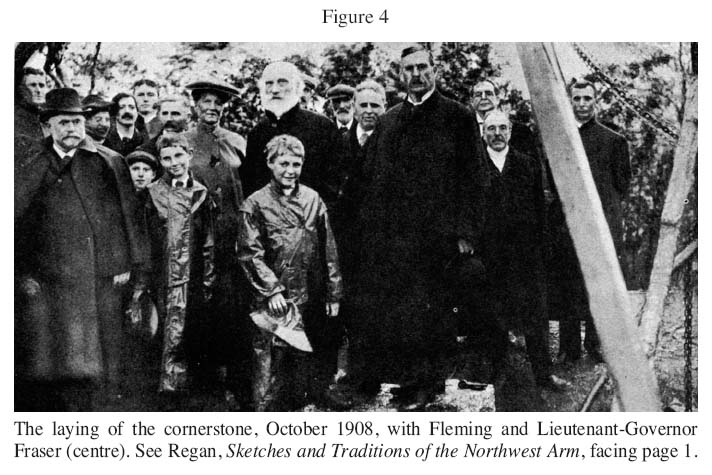

27 The events were conducted under a canvas tarpaulin that had been provided for the occasion. Letters from various officials were read, the deed was handed over by Fleming to Lieutenant-Governor Fraser at which time a 21-gun salute was fired from the Citadel ("as an acknowledgement of the supremacy of the civil power"). Then with silver trowel in hand, Lieutenant-Governor Fraser laid the corner-stone. This was followed by speeches from Fleming, Joseph A. Chisholm, president of the Canadian Club of Halifax, and Lieutenant-Governor Fraser (who also read telegrams from the Governor General, Lord Grey, and the Secretary for the Colonies, Lord Crewe) as well as the singing of the national anthem. "Three cheers" were reserved for Fleming at the end. All was captured for posterity in photographs by G.A. Gauvin (see figure 4).47

Figure 4 : The laying of the cornerstone, October 1908, with Fleming and Lieutenant-Governor Fraser (centre).

Display large image of Figure 4

28 In commenting on the suitability of the setting, Halifax journalist John Regan noted that the cornerstone had been laid "alongside the water of the same ocean across which the original settlers came to found homes in the untamed wilderness". He concluded that the clearing "made for the occasion, [was] just like what probably took place one hundred and fifty years previous, when the first hardy settlers started their community and organized their pioneer assembly beneath the shadow of the same varieties of trees – maple, beech, spruce, etc. – that furnished a natural setting for the recent spectacle at the Northwest Arm".48

29 Such sentiment was very much part of the conception of the tower. Moreover, it was meant to serve as a mnemonic device to educate future generations. But in many respects the true message was not so much to be found in the tower but in the institution being commemorated, as the editorial in the Halifax Daily Echo on 14 August 1912 quite rightly suggested:Why should be constructed a perishable pile to memorialize an imperishable deed in the development of our civilization? The hill upon which the Memorial Tower rests will endure long after the structure itself will have been forgotten; the waters will continue to wash the base of the hill, when the very stones which go to make the temple, have crumbled into dust; but the event for which the tower stands will abide the passage of all three.

Si monumentum requiris, circumspice . The true monument to those who were responsible for the granting of a free Parliament in Nova Scotia is to be found in the might and majesty and power of the British Empire.49

30 The tower was constructed in the heyday of what Eric Hobsbawm has termed "the Age of Empire".50 Although the might, majesty and power of the empire was to gradually lose much of its lustre in the dark days of the First World War, imperialism was still very much alive in 1908.51 The tower was conceived of as a nationalist monument; however, in keeping with imperialist visions, this was nationalism framed within the concept of an imperial union or federation.52 Further, commemoration took place not within a wholly political sphere but rather in a public arena accompanied by "public" statements of national identity.53

31 Despite this public commemoration, it is important to remember just who was involved in the process. In the aftermath of the Boer War, Canada saw the creation of institutions whose role was to promote a newly developed patriotism. Buoyed by a new sense of Canada’s international contribution, a number of different nationalist enterprises and organizations were initiated. Among these was the construction of the tower under the auspices of the Canadian Club of Halifax.54 In many respects, its erection was an enterprise supported by a predominantly Anglo-Celtic, male elite drawn from the professional and upper classes of society.55 Public involvement in the process was seemingly minimal.56 Consequently, there were remarkable silences in the commemoration and in the monument itself. Indeed, the recognition of electoral "representation" and the evolution of political process, the raison d’être of the tower, only helped to underscore the fact that many Canadians at the time still remained under-represented and even disenfranchised.57

32 In part, the tower may have been an Anglo-Celtic response to the commemorative process in Quebec.58 In this sense, both the monument and the events surrounding its conception and its unveiling may also be viewed as indicators of a "Britishness" that still remained firmly entrenched in the minds of the tower’s creators. But this Britishness was more than simply a veneration of all things British; rather, there was an utopian sense that within the British "colonies" there was a chance to create something that was a "better" Britain. Indeed, as Philip Buckner and Carl Bridge suggest, it was within those same colonies that "the very idea of a ‘British’ Empire" was formulated and from whence it "flowed back to the ‘mother country’".59 That a degree of parliamentary autonomy had been won, and indeed continued, within the fold of the empire was an important feature of the imperialist argument. At the same time, however, it was emblematic of the perceived progress that continued to be made within the political arenas of British North America.60

33 The tower’s proponents were also not slow to draw parallels with the United States: "We can recall the fact that this representative government came to Nova Scotia before the establishment of the American Congress".61 Unlike the latter, the accent, if somewhat naively, was on liberty gained through compromise and negotiation and not, as one commentator wrote, "wrung by force . . . or by rebellion stained".62 Liberty was seen to have been formed within the very core of empire. Furthermore, its sponsors remained steadfastly loyal to the Crown.

34 Comparisons with American institutions did not stop there. From its earliest days, the tower had been perceived of as a Canadian corollary to Federico Bellini’s Statue of Liberty, which had been erected in 1886 on Bedloe’s Island in the New York harbour. The London Times, on 19 August 1912, even made the bold statement that the tower would "meet the voyager from the Atlantic and tell him that he is entering a land of liberty not less real, though perhaps a little less declamatory, than that which is celebrated by the famous statue that meets him as he enters a harbour farther south".63

35 In reality, there was no real prospect that "Canada’s Statue of Liberty", or Halifax for that matter, would ever achieve as prominent a stature in the Canadian myth-symbol complex. From the pan-Canadian perspective, early-20th-century Halifax – "The Atlantic Gateway of the Dominion" – had become increasingly marginalized in official circles and had lost the status it once enjoyed as a fortress of the empire and "Warden of the Honour of the North".64 The downturn in her fortunes had come following the Boer War, with the removal of the last of the imperial garrison in February 1906 and with the handing over of all military properties to the Dominion government. The federal government became increasingly less interested in Maritime matters and, as a result, the defences and military facilities, manned by caretaker units, were allowed to run down. The loss of the British imperial regiments and the Royal Navy had a severe effect on Halifax society and economy.65

36 It was in this climate that the construction of the tower began. In some ways, these moments may be seen as attempts to re-establish Halifax in the Canadian imagination. In actuality, it could no longer occupy such a place. Nevertheless, hope remained for a brighter future. Fleming believed that there was no better place than Halifax, "where the first Assembly in the outer Empire, as it at present stands, was held", to raise a commemorative monument of this nature. Further, he suggested that "the structure itself should be of such a character as to increase the attractions of the extreme beauty of its situation, and add to the many interests of Halifax, with its ocean trade and its magnificent commercial greatness of the future".66

37 The tower was therefore intended to represent progress, both political and cultural, in the 150 years since the first assembly. On the occasion of the laying of the cornerstone in 1908, Fleming recalled the long process of nation building "since that memorable day". "We must remember", he claimed, "that strength results from slow and steady growth and we cannot forget that the founding and building-up of a new nation in a new world requires time and that more than the ordinary forces are needful to ensure stability".67 Arguably, the tower highlights, in a material form, the romantic fascination of turn-of-the-century imperialists, such as Fleming, with progress and, in particular, with the progress of Canadian history. "Canadian imperialism", Carl Berger suggests, "was dominated by appeals to the past primarily because its exponents regarded history as the repository of enduring and valuable principles and not because they sought to escape into some secure and idealized Heroic Age". He adds: "Imperialists contended that the history of the Dominion was essentially the story of material progress and the steady advancement of liberty and self-government". Most significantly for our understanding of the Halifax Memorial Tower, Berger also maintains that "the chief value of history was that it affirmed and detailed the relentless march of improvement by contrasting the state of things in some remote time with the high level of society in a later age". Furthermore, he notes the different contributions made throughout history were awarded different weights: "Indeed it was maintained that Canadian history began in a complete state of stagnation and only by slow evolution attained the speed and breadth of improvement characteristic of the middle 19th century".68 This understanding of historcial development was uppermost in Sanford Fleming’s mind when he suggested thatthere must at the beginning be men of strength, who can break away from the old conditions to face the new and unknown. They must be fitted by Divine Providence for the work given them. Men of will, men of wisdom, men of foresight are needed, men who can realize the possibilities of the future and who can equally arise to the opportunities of the present. Adventurous spirits too are needed to conquer unseen obstacles, and not seldom the strongest only are equal to the task.

These words apply to the first settlers of Nova Scotia and these pioneers include men accustomed to a sea-faring life, men who could battle with the storm and the perils of the deep. Out of such struggles came forth the finest spirits and the great actors in history whose names we find in the country’s annals.69

38 The commemorated past was, therefore, one of rugged individualism, heroism, godliness and vision. Many, like Fleming, became nostalgic for a time in which the building blocks of the nation were believed to have been laid – the spirit, principles and values that had been the original cornerstones of the Dominion. The glorious vision of those men who had established "representative government" against certain odds and bureaucratic resistance in the early days of the colony was the thread that now bound the past and the present together in a "Golden Age narrative".70

39 Early-20th-century commentators looked to the perceived industry and tenacity of many of the early settlers in forming a romantic (and often imagined) notion of an "heroic" or "Golden Age". The concept of the self made-man, an individualist hero whose qualities and deeds set him apart from others, also played heavily in such late-19th and early-20th-century histories.71 The retrospective appeal of a "Golden Age" also manifested itself in an interest in primary occurrences in history or "firsts". The commemoration of the 1758 assembly may perhaps be viewed in this light, and even more so when it is remembered that the 1758 assembly was promoted as the first representative assembly in the empire.

40 In Nova Scotia, a 20th-century bureaucracy and tourism industry began to incorporate the pioneering spirit of the "Golden Age" into a "progressive", coherent narrative that had "a clear sense of beginning and ending, central characters and peripheral figures, heroes and villains".72 In the latter vein, it should be noted that the institution of the 1758 assembly had, in fact, been driven as much by self-interest and commercial enterprise as it had by any sense of political will or mass involvement of the body politic. What was described as "one of the most important events that ever occurred in Canada in respect to its bearing on the whole future of the Empire" had been predicated on the right to determine one’s own affairs and to protect one’s own interests (the basis of the liberal ethos in Canadian society in the next century); the supposed heroes of the process included men like Joshua Mauger, whose fortune had been made in part in the West Indian slave trade and in the control of rum imports and distilleries in the new colony.73

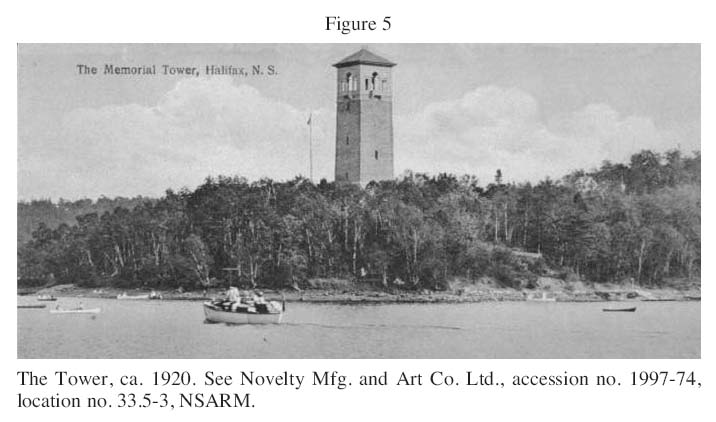

41 But, in reality, the tower was not simply a memorial to the men of the 1758 assembly. Rather, as we have seen, its purpose was to memorialize both a "spirit of colonial liberty" and, later, "imperial stability".74 As a monument to a political process it is a physical manifestation not only of historical progress but also of a certain ideology writ large on the landscape of the Northwest Arm (see figure 5). The tower could, therefore, be claimed by its supporters at the time to be "unique among the world’s memorials".75

Figure 5 : The Tower, ca. 1920.

Display large image of Figure 5

42 Whether the building of the tower helps give complete credence to Michael North’s comment that "monuments . . . are microcosmic summations of entire cultures" or whether there was a different kind of collective memory at work must be debated further. On the other hand, it is important to recognize that at the time of its dedication only a small constituency could lay claim to the tower. Among the voices most noticeably absent, both in the dedicatory ceremony and in the commemorative rhetoric, are those of women, Native people, Black Nova Scotians, immigrants and the poor. Hegemonic control over the commemorative process in this instance was very much imposed by an Anglo-Celtic elite with an agenda to promote a certain brand of imperialism and nationalism.

43 In the latter sense, the tower was clearly a monument to "Britishness". In its earliest conception, it was intended to be an exercise in constructed "archaeology": its strata traced backwards from the present to the founding of a dominion "under the watchful care of Great Britain"and through the history of European settlement in Nova Scotia to the glacial tills upon which it was built.76 However, the vision was not simply reflective of the past. As with most monumental enterprises of the time, the Halifax Memorial Tower spoke as much to a need to address the future and to commemorate the present as it did to events of the past. It may be seen, therefore, as an expression of turn-of-the-century hegemonic notions of progress, its glance skyward, towards the bright future of the "nation" and a continued equal membership in a "united" British Empire. In truth, its didactic nature was quickly forgotten. Visions of imperial progress and prosperity that had inspired the tower’s creators were soon lost in the realities of a modern world. In December 1912 Halifax was caught up in the drama surrounding the sinking of the Titanic, three years later the city was in the grip of the First World War and, in December 1917, a large portion of the city lay in ruins following the Halifax Explosion. Such grim realities replaced the commemorative fervour of the early-20th century. Moreover, in the wake of the war, the citizens of Halifax and Canada as a whole would eventually come to reassess both their place within the empire and Canada’s position as a nation in its own right.

Notes