Reflections on My 18 Years with Acadiensis

1 IT WOULD BE DIFFICULT TO OVERSTATE THE CENTRAL ROLE OF Acadiensis within Atlantic Canada studies. But I discovered its importance relatively late in my academic career. Having done a masters in political science, it was not until I began my doctoral studies in history at the University of New Brunswick in 1993 under the supervision of E.R. “Ernie” Forbes that I came to realize just how much of the history of Atlantic Canada was contained within the pages of the journal – even in terms of my relatively narrow topic of co-operative wholesaling in the Maritimes. Ernie also made it clear to me that Acadiensis was the big stage where young scholars announced their entry into the field of Atlantic Canada studies – and it was an opportunity not to be squandered; as Ernie put it, one’s first big article in Acadiensis was how one made their first impression to others in the field, and it was, invariably, a lasting impression.

2 Seven years later, and nearing the completion of my doctoral studies, the significance of Acadiensis was re-emphasized to me in a new way at the 2000 Atlantic Canada Studies Conference at Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax. The highlight of that conference were the sessions examining “the origins and development of the new regional history in Atlantic Canada. As Brook Taylor explained at the conference, ‘our goal was to celebrate and discuss the work of that first generation of regional scholars and promote a process of critical evaluation of that period’.”1 Sitting in on those sessions, though, I and many other younger scholars were disappointed in the uncritical nature of the comments by several of the older scholars – a point elaborated upon by another scholar in attendance that day, P.D. Clark, in his “L’Acadie Perdue: Or, Maritime History’s Other”: “The engaging, autobiographical (with all that this implies), somewhat whimsical nature of their interventions confirmed in my mind the essentialist, pragmatic and now orthodox consensus that had marked the historiography of that generation.” Clarke went on to note the virtual “exclusion of Acadianité” from the presentations at the conference (only 2 of 45 presentations were on Acadia) – a point emphasized at the time by Naomi Griffiths and Jacques Paul Couturier, the latter of whom “was the only French-language speaker at the conference” and “who only half-jokingly referred to himself as the ‘token Acadian’.” And Clarke criticized the “principal orientation of Maritime historiography [which] is its preoccupation with the processes of modernity, as shown by its attentiveness to the post-Confederation period and the subsumption of most of its endeavours under the rubric of regional disparity” – an orientation that “favoured structure over culture” and created little interest in Acadie – “large sections of which remained anchored in rurality and ‘traditionality’ until the 1970s.”2

3 I had no idea at that time, of course, that within three short years – in 2003 – I would be hired to assume the position of assistant editor, which in 2006 became the position of managing editor of Acadiensis. Thrust into this central position with Atlantic Canada studies with a PhD (2001) but no formal training in editing, I joined Bill Parenteau, a new hire in the UNB history department who had been similarly thrust into the editorship of the journal with little time to prepare. Together, we sought our bearings while trying to maintain the traditionally high academic standards of the journal. We would sit and compare notes on possible edits on accepted submissions, many by some of the most prominent scholars in the field. It was an intimidating situation for both of us. One of most prominent memories from those early days was an e-mail from a very prominent scholar in the field who wrote to me complaining of our policy of using the British system of terminal punctuation – the period being placed after the closing quotation marks – as he felt it made it difficult to correct students since they would often refer to Acadiensis to justify placing the period after the quotation marks.

4 It did not take me too long to realize that we needed a more definitive guide than the ten-page Acadiensis style guide that Bill and I had inherited from previous editors. So I adopted the use of the 956-page Chicago Manual of Style as the way to settle such issues, and spent many hours during subsequent years poring through its pages in attempts to make all of the pieces published within the pages of the journal as consistent as possible in terms of a multitude of style issues.

5 Another important innovation followed shortly thereafter with the abandonment of Corel WordPerfect in favour of Microsoft Word – a change mandated by UNB itself years later as it withdrew technical and other support for WordPerfect. But for myself, adopting Word well before that time was simply an attempt to rationalize and make more efficient use of my time. When I first started at Acadiensis, edits had to be entered manually on paper, necessitating the Acadiensis office manager, Beckey Daniel, to create new versions of manuscripts that I would have to then go through and check. The “Track Changes” feature of Word eliminated those extra steps, and helped greatly in terms of more efficient production of the journal.

6 Bill’s serious health issues in 2009, and his having to step down as editor as a result, meant that I, for a brief time, worked by myself, a situation that was quickly (and thankfully) rectified through the efforts of Gail Campbell (as chair of the Acadiensis board) and others, who managed to create a system of co-editors for Acadiensis. Up until that time, the editorship has always been held by a UNB professor (Phil Buckner, David Frank, Gail Campbell, or Bill Parenteau). But John Reid from Saint Mary’s University and Janet Guildford of Mount Saint Vincent University agreed to step in as co-editors in 2010 – the first time that Acadiensis had an editor – or, in this case, two co-editors – from outside of UNB. When Guildford stepped down at the end of 2012, the coeditorship for the most part became a joint co-editorship between a faculty member at UNB and a faculty member from another university; the exception to this general rule/goal was much of 2018-2019, when Suzanne Morton of McGill and Andrew Nurse of Mount Allison shared the co-editorship. Nurse had followed John Reid in 2016, and was, in turn, joined by Suzanne Morton in 2018; the UNB co-editors were Sasha Mullally beginning in 2013 and later followed by Don Wright in 2019 and then Erin Morton in 2021. The tradition of the French language editor being from outside UNB was established before my time, and has continued to this day: Josette Brun (Université Laval) (2003), Nicole Lang (Université de Moncton) (2005), Julien Massicotte (Université de Moncton) (2011), and Patrick Nöel (Université de Saint-Boniface) (2019). The review essay editor began as external – the position was created in 2010 and Michael Boudreau (St. Thomas) served as the first such editor – and he was followed by Greg Marquis (UNB Saint John) in 2018. The position digital communications editor was created in 2015, and Corey Slumkoski (Mount Saint Vincent) remains in that position to this day.3

7 During these years there have also been trends that have been far beyond our control. There has been, for instance, what appears to be an inexorable shift to online readership/use of Acadiensis, the same as most other academic journals. Del Muise’s refusal to take his print copy of the new issue of Acadiensis at an Atlantic Canada Studies Conference many years ago in some way foreshadowed this massive shift; Del said that he read the journal online and did not want to carry a printed copy around at the conference.

8 An important part of that huge shift to online readership grew out of the push in 2009-2010 to mount the current and recent issues of Acadiensis online through UNB’s Centre for Digital Scholarship4; the digitization of all of the back issues stretching back to the founding of Acadiensis in 1971 followed within a year or so. Regrettably, only the new pieces that were composed, edited, and published electronically could be coded in html (with mark-up and instant search functions); the vast majority of our back issues were limited to digital life as only pdfs. Still, it was a notable achievement, at a small cost, to have all of the content of Acadiensis scholarship in digital format.

9 Of even more impact to the journal – especially its long-term financial health – was that the digitization of all of our content proved to be somewhat of a “double-edged sword.” The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) – the journal’s major funder – has helped propel the move to digital and away from print through the granting process, which has, for almost 10 years, emphasized free online access of all content in journals funded by public money from the Government of Canada. At the same time, though, SSHRC has not really addressed the issue of how subscription-based journals are supposed to be financially solvent if they provide free access to their content, which negates the need of particularly university-based individual subscribers – the majority of our subscriber base of individuals – to pay for subscriptions since they can access the journal for free through their university’s library system.

10 An additional significant change over the past 12 years has been rapidly increasing involvement of journal aggregators in the distribution of Acadiensis; these aggregators remit royalties to the journal based on the usage of Acadiensis by its institutional and/or individual members/customers – income that helps provide much-needed income for the journal. In 2009 Acadiensis was invited to be part of the not-for-profit JSTOR, in 2011 we signed a contract with the for-profit EBSCO, and in 2016 we were invited to be part of the not-for-profit Project MUSE. These three aggregators were (and are) international in scope, and partnerships with them no doubt helped to boost the profile of the journal in Canada and in other countries. Within Canada, in 2009, Acadiensis signed a contract with Érudit, the non-for-profit Montreal-based platform dedicated to the dissemination of Canadian humanities and social science research. This Canadian aggregator was part of the Synergies network, which also partnered with five Canadian universities (UNB, University of Toronto, University of Calgary, Simon Fraser University, and Université de Montréal – the lead institution) for the distribution of the electronic content.5

11 Canadian university libraries and other research institutions also organized themselves during this time period – as the Canadian Research and Knowledge Network (CRKN) – with the objective of negotiating with the large aggregators for better prices on the journal content that they needed. As deals were signed, and different packages of journals were created by aggregators to satisfy library customer needs, at least two significant trends emerged – trends that have continued to this day. Some less-prominent journals were excluded from some “packages” based on low institutional usage, and this, of course, has hurt these journals financially (and in terms of their reputation and distribution). Second, and more relevant for Acadiensis, the 65-member university libraries/research institutions that make up CRKN, having secured access to journals like Acadiensis through aggregator package deals, began to stop their institutional subscriptions to Acadiensis. This steep decline in institutional subscriptions, coupled with a parallel steep decline in individual subscriptions – since most individual subscribers could access the journal through their universities – has meant a precipitous decline in subscriptions: when I started at Acadiensis in 2003 we were mailing out almost 500 copies of each issue; in 2021 we are mailing out just over 200 copies.

12 Despite all of these significant changes over the past 18 years – and innovations such as creating two sets of files for each issue – one with black and white images for the print version to save money and one with colour images for the online version – much of the work as managing editor has remained essentially the same: the often-difficult task of finding enough assessors to help evaluate the submissions that come into Acadiensis, supporting the work of the co-editors, dealing with authors, and co-ordinating all of the aspects of the production process. And, of course, once an issue is complete, the work begins on the next issue.

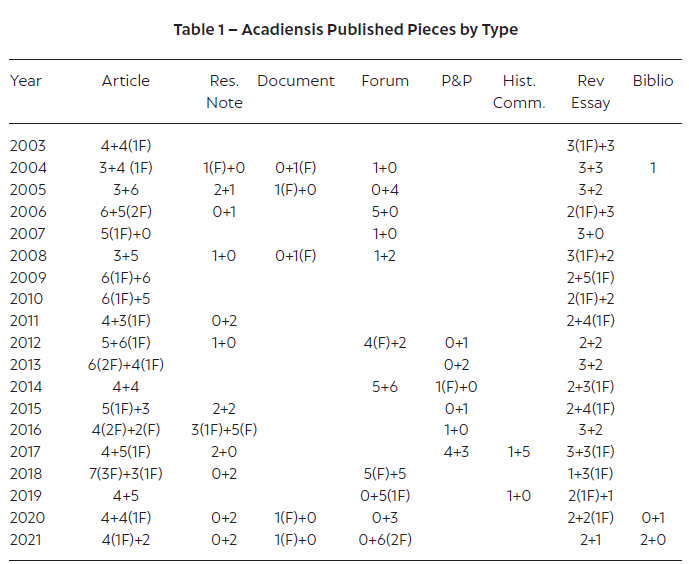

13 One of the main functions of my job as managing editor is the copyediting of all of the English pieces – we hire a French-language copyeditor for the French-language pieces – and all that this entails. For a long time the process has remained virtually unchanged: once the co-editors or review essays editor have made comments on a piece and the author has responded, I copyedit the piece using track changes in terms of grammar, diction, and content (to a degree) before sending it to the co-editors/review essay editor for their copyedit comments. Once I have it back, I accept the necessary changes (in terms of house style, etc.) and send it to the author for responses to the editorial queries. By my count, since I began at Acadiensis I have copyedited 308 pieces, including 138 articles, 24 research notes, 63 forum components, 76 review essays, and 5 bibliographies.6

14 The copyediting process is one of the most personal aspects of the managing editor’s job as one has to get “inside” a piece and try to read it from the perspective of an informed audience – e.g., not only not only in terms of grammar, word choice, and our house style, but ascertaining what is unclear and/or needs further substantiation. And, at times, one can get so involved in trying to get “inside” a piece that sometimes one can lose perspective. I think that it has only happened twice during my 18 years with the journal – becoming so intent on trying to improve a piece that I stepped “over the line” and asked for changes to which the author took personal exception. But these were learning experiences for myself, and helped reinforce in my mind that a copyeditor always has to take a “back seat” to the author for, after all, it is the author’s name of the piece and there is only so much that a copyeditor can (and should) do. I have also, though, encountered the other extreme: authors who knowingly send in substandard work as they are confident that we will fix it up (and one author told me this explicitly).

15 Other challenges, of course, persist as well. Despite the best efforts of the various French-language editors over the years, attracting French-language submissions continues to be a longstanding issue – perhaps due, at least in part, to the reasons articulated by P.D. Clarke discussed above. Table 1 breaks down the type of pieces published within the pages of the journal since 2003 – with the French-language pieces are indicated by “F” – and it indicates some success over the years in publishing French-language content within particularly the largest two categories (the articles and review essays).

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1

Note: The “+” sign separates the two issues within a calendar year and the “F” signifies Frenchlanguage pieces.

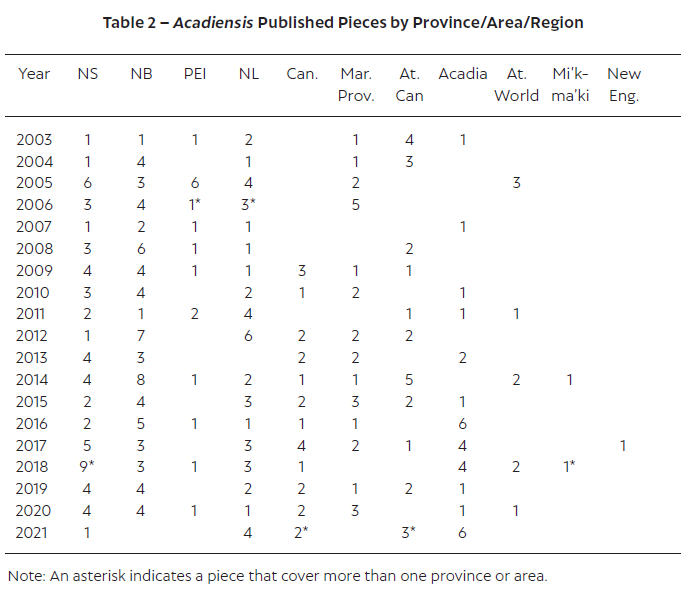

Attracting sufficient work of women scholars has also continued to be a concern – a point driven home in recent years by an issue that featured exclusively male authors. And, of course, there is the problem of trying to maintain somewhat of a regional balance in terms of topics; Table 2 breaks down all of the commonly used categories, using pieces in the journal that refer explicitly to a particular region, area, or province. While the strong presence of all four Atlantic provinces and “Atlantic Canada” and “Acadia” come as no surprise, the continued persistence of the “Maritime Provinces” is a bit unexpected, and the emergence of terms such as “Mi’kma’ki” and “Atlantic World” indicate change is happening in terms of how the region is being conceived – especially in more recent years.

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 2

As with other academic journals, Acadiensis is somewhat at the mercy of the submission process in terms of what it publishes. But steps have been taken through creating new types of pieces, such as the “Present & Past” and “Historiographic Commentary” pieces, to help give scholars new ways of addressing scholarly and/or public issues – albeit these remain somewhat underutilized. In addition, we have emphasized the use of forums and review essays to offer underrepresented scholars, particularly Black and Indigenous and emerging, a more varied way to publish in Acadiensis. But there is still much to be done in this regard and perhaps in terms of other approaches to regional history, such making a renewed effort to attract more interdisciplinary work.

It has been more than 20 years since that Atlantic Studies Conference at Mount Saint Vincent University and those panels about the past and future of Atlantic Canada as a field. As I near retirement, I cannot help but wonder, and even worry not only about the future of the journal but also about the future of the field. Not only have universities throughout the region continued to cut positions in Atlantic Canadian history and thus offer fewer courses in the field (with courses on “Atlantic Canada” often disappearing in universities elsewhere in Canada), but the field continues to face the fragmentation of historical inquiry as separate subfields of inquiry vie for scholarly attention and coverage, including women and gender studies, Acadian history, Black and Indigenous history, political/legal history, economic development and labour history, military history, tourism and commemoration, media studies, primary production (agriculture, fishing and farming), health and medical history, immigration, the arts, education, religion, and biographies. Even the notion of the existence of the Atlantic “region” has been interrogated.7 And what exactly does research in all of these distinct fields reveal about the nature of “Atlantic Canada”? Are they simply case studies of broader phenomenon? Or do they reveal things about what is happening in this part of the world that are significant in themselves – that reveal a distinctiveness that makes sense for/ helps justify a separate field of “Atlantic Canada studies”? As Acadiensis moves beyond its 50th year of publishing, these and other questions will no doubt continue to attract scholarly analysis and debate.