FORUM – Acadiensis @ 50

Building Research and Community Networks:

Putting Acadiensis at the Centre of a Digital Community

1 WE LEARN FROM OUR STUDENTS. MUCH OF WHAT I WANT to say I have learned from mine. Their research takes us to new places, uncovers new knowledge, allows us to see old knowledge in new ways. I am blessed with a number right now who are doing lots of uncovering, and tons in the new ways of seeing. All are engaged at some level of digital history. Trudy Tattersall is a doctoral student in Brock’s Interdisciplinary Humanities program. Her work shows how gendered space was configured in settler colonial homes in Nova Scotia. Looking at a range of sources, one chapter is a website that connects digitized artifacts from Nova Scotia museums to homes, teachers, and women’s domestic training. Naythan Poulin’s project on Acadian historiography is not digital per se, but he manages a library database for me, built a search function in Omeka, and was a leading figure in our ArcGIS-based Isle Saint-Jean project.1 Jess Linzel just completed a magnificent MA thesis in our history program using ArcGIS that plots over 13,000 pieces of census and account book data on historic maps, allowing us to see the spatial unfolding of the economy of early British Niagara.2 But it is more than tech. A hiker and heritage advocate, she walks those fields and ravines, talks to farmers and the local heritage community, and knows and builds upon local knowledge in building her analysis of capital formation, slave-based agriculture, and the continued significance of the fur trade and Indigenous producers and consumers. This project would not be possible, at least not on this scale and in a MA timeframe, without GIS, not only for its technical capacity but also for the conceptual possibilities it enables. It also would not be as good without Linzel’s boots firmly on the Niagara ground and in the Niagara heritage community.

2 Josh Manitowabi, an Odawa member of the Wikwemikong nation on Manitoulin Island, is completing his PhD dissertation, but his methodology is keeping his boots in many places: digital archives (it is the year of pandemic research strategies!), building an ArcGIS “deep map” of Anishinaabe history on Manitoulin Island, and talking to the people of his community. Like Linzel in Niagara, Manitowabi knows Manitoulin well; but what he knows best is how much more his community can teach him. Working with digital manuscripts and maps from archives in Canada, France, and the United States and combining that with stories and expressions of how history and the land are embedded in Anishinaabemowin, the Anishnaabek language, and entering all this into an ArcGIS map, Manitowabi is rebuilding Manitoulin history as one that both reflects the record of western colonial archives and the truths that knowledge keepers hold. He is decolonizing Manitoulin history, bringing the community in, and utilising technologies that facilitate the bridging of western and Indigenous knowledges and methodologies.

3 In this essay, I want to suggest that we, the Acadiensis research community, should aim to embrace more of digital history’s possibilities. I do so for two reasons. First, because it offers tools that are valuable additions to historians’ practice. We will pursue this more below, but briefly we can list a whole range of digital tools, including text mining, virtual reality (VR), and spatial tools such as ArcGIS. I am not an expert in any of these – though many of my students are! – and I am not for a minute suggesting that any of us need to wholesale adopt any of these methods. But we should be aware of their potential uses. We should also be aware of how to read works that employ them, be able to guide our students in their use, and be able to recognize when they are, and when they are not, more valuable than our tried-and-true approaches. Second, despite many fears that the digital world is the harbinger of a post-human world, it is clear that digital methods can in fact expand human connectedness by building communities of mutual interest. In the academy, writes Josh MacFadyen, “digital humanities tools and communities are making research increasingly accessible, participatory, and decolonial.”3 I want to suggest that many of the methodologies of digital technologies, particularly of collaborative and crowd-sourced digital methods, encourage and moreover enable more people to participate in making history. I want us to strengthen our practices and build better research communities.

4 This combination of technology and community is at the heart of my essay. But at the outset, let me say – confess? acknowledge? – that I am not, properly speaking, a digital historian in the vein of someone like Josh MacFadyen, Ian Milligan, or my colleague Colin Rose.4 But I am someone who has spent the past decade lurking on the sidelines, developing online courses (before we had to!), digitizing sources, building public-history-style websites, teaching with digital tools like ArcGIS and Voyant, and building with Keith Grant an online digital library of books and print culture materials. Teaching in an online modality, encouraging digital-era students to think about where and how they are learning and what they are seeing, and the materiality of texts, of scales, and of patterns of language (Voyant) has pushed me to think about my own research differently – to think more about the context of the sources I read. In the digital era, in a world where students encounter early modern text either on screens or in textbooks – where text is text, it is all just text – it is helpful to allow students to see that what they are reading and how they are reading it, and how this can help alter how they understand it. For the most part, though, I have simply been on the sideline, admiring digital historians’ innovative outcomes: the databases, visualizations, re-conceptualizations, and analyses made possible by these many new methods. But, as my much smarter colleagues in Brock’s Centre for Pedagogical Innovations will tell you, I am not really good at tech, and I still need my hand held on a lot of this.

5 In Canada, we have one of the world’s best historical research clusters working largely online. NiCHE, the Network in Canadian History & Environment/Nouvelle initiative Canadienne en histoire de l’environnement, is a remarkable collection of environmental historians who are organizing conferences and workshops, and producing huge amounts of content via blogs and podcasts.5 That work in turn is generating public discussion on social media and academic books and articles. While most of the two or three substantial posts they produce each week centre on Canadian topics, environmental history is inherently transnational and there is a fantastic range of international authors bringing Canada and Canadian issues into a global view. There is also the Github-based collaborative publication, the Programming Historian, initiated by Alan MacEachern and Bill Turkel over ten years ago.6 It is probably fair to say that NiCHE has been as influential in shaping Canadian historiography as Harold Innis or Donald Creighton were in their days. Their spirit is collaborative; they creatively bring together people and ideas and provide a rich and accessible forum for discussion, writing, and debate. Because they exist in an activist field, and because of the inherent interdisciplinarity of environmental history, they must be collaborative. It is telling that the first director, Alan MacEachern, recalls that his “ideas for NiCHE were more about designing a network than designing Canadian environmental history per se [because] I wanted the community to define the field itself organically.”7 That collaborative spirit, that sense that the work of many would make the group stronger, still appears to govern the network and the people who participate in it. It is a great model for what energy and creativity, backed with money, can do.

6 NiCHE obtained a large SSHRC grant. Such endeavours are costly, both in terms of money and human energy, which is why the other major success in the blogosphere – Borealia: Early Canadian History – is so remarkable: it was far more modestly developed. Started on a shoestring budget by two recent PhDs then at UNB, Keith Grant and Denis McKim, the blog has placed itself as a peer of major US colonial-era history projects like the Junto and Commonplace at the deeper-pocketed institutions like Omohundro Institute, the College of William and Mary, and the University of Virginia. Their initiative, like that of the environmental historians in NiCHE, highlights the transnational movement evident across western historiography in the past two decades. Bringing together Canadian and international scholars to write about Canada, as well as its context before it was Canada, enlivens the field and brings early Canadianists into a firmer relationship with their American, British, and French colleagues. Conferences, of course, do that too, but these lively, short, frequently appearing pieces have created an energetic centre for this rapidly growing sub-field. Borealia’s creators embraced the digital turn and in produced a significant tool for the dissemination of new findings, debate, and discussion of the colonial era.

7 What of Acadiensis? The journal looks very different than it did in the late 20th century. Then, many Atlantic Canadian scholars were very concerned about the communities that had been too long excluded from the stories we were telling. We needed to look at more people, more communities, and bring them into the making of regional history. The regional literature has improved dramatically. To be sure, there is still a long way to go there in terms of basic research (we need to know more), smarter and more democratic politics (new people and new communities need to be setting agendas), and community outreach (that for all the progress, white cisgender males still dominate the field). And some holes are bigger than others: for example, while the content on gender and sexuality has improved, there is a significant hole still on queer histories.8 But it is worth saying, again,9 that the strides made in covering more communities really is a remarkable achievement; we are a relatively small community covering a lot of ground. Indigenous, Black, and Acadian histories, in particular, have advanced significantly, and we also continue to explore older and clearly still valuable themes related to the histories of region, politics, women, and capitalism. A great deal has been accomplished.

8 That is not true when it comes to digital history, at least not as seen in the journal itself. There is no doubt that basic modes of digital engagement are everywhere. Lots of this research is no doubt rooted in online databases. Who does not access their journals online (even if we have a paper subscription)? Who does not spend a lot of time in archive.org? Who does not read blogs and listen to podcasts? And so on. But as a direct basis for the research, it is simply not a significant part of the work we see in the pages of Acadiensis. There is a social media presence; Acadiensis now has a blog10 and is active on Twitter and Facebook. But it seems modest, certainly not close to the centre of the endeavour. A search of the journal’s content for the term “digital” in JSTOR and EBSCO back to 1971 yields 39 hits, half of which are front-matter references to digital editor Corey Slumkoski (plus two state-of-the-field pieces by Slumkoski). There may well be more digital applications not made explicit in discussions of method, but sifting out all the random notices of the word “digital” in citations and lists of recent publications we are arrive at three pieces, all authored or co-authored by Thomas Peace. His reconstructions of 18th-century Acadian and Mi’kmaw social networks has brought wholly new light on a critical issue in understanding the French period of regional history, and particularly the increasingly fraught issue of relations between Indigenous and settler populations11 - an issue given added relevance in the current politics of the so-called “eastern Métis.”12 It is superb work – particularly in its fine balance of use of digital and traditional historical methods. Ian Milligan rightly notes that digital methods, particularly a reliance on digital sources, sometimes narrow the channels of research, selecting for the historian where critical awareness should be a better guide.13 No one examining Peace’s references would ever imagine he had unduly narrowed his search.

9 Digitally, Atlantic Canada Studies was once ahead of the curve, or some Atlantic Canadian scholars were anyhow. Margaret Conrad’s accomplishment in building (overseeing the building of? what is the correct collaborative verb?) the Atlantic Canada portal was innovative in a way that only some of us realized at the time.14 It was a large-scale project that provided training for students, greatly improved access to important primary sources, increased visibility of the region and its history, and perhaps most importantly increased visibility of traditionally less-visible communities. And it was, I think, aimed very much where I want to urge us to go – at the intersection of research tools and methods of community engagement. Today it is a set of unmaintained, archived links. There are still tons of valuable things there (I used the New Brunswick Indigenous land petitions in a course just last year and I doubt I am alone). However, not only has it not been maintained, but it has also not been either updated for more interactive/social uses nor have parallel interactive/ social uses been encouraged. It rests very much in that older, heavily curated, library-like model of information storage and use. Many wonderful things exist there; as long as the sites work, it will remain useful. But its ability to grow, to be a tool for establishing research networks, to be used as an active tool for community engagement – be that research communities or local communities – is severely limited. It is the digital equivalent of that old book we always find useful, when we think of it.

10 Part of the loss associated with the Atlantic Canada portal is being taken up by digital repositories and digital scholarship “labs.” Both Dalhousie University and Memorial University, among others,15 have created centres that house digital projects and facilitate digital practices.16 That is good, and these play much wider roles than simply housing Atlantic Canadian history. The most important example here is the UNB Atlantic Digital Scholarship page,17 which is fulfilling several of the roles played by the old portal. Funded by Elizabeth Mancke’s Canada Research Chair through UNB’s Atlantic Canada Studies Centre, the site functions like a portal by housing a number of UNB-based databases: the British North America Legislative, the Anglican church records of the Marianne Grey Otty database, UNB newspapers, Vocabularies of Identity | Vocabulaires Identitaires, Early Modern Maritime Recipes, GeoNB Mapping (the Province of New Brunswick’s digital gateway to geographic information), and the New Brunswick Literary Encyclopedia. There is also a complete digital run of fisheries reports of the colonial New Brunswick and Nova Scotia governments, as well as a home for the New Brunswick Storytellers Project. The list of projects and their researchers is a useful networking tool, and the links to regional archives and libraries puts lots of good regional information in one place. As a showcase for regional work, the UNB Digital Scholarship page is most welcome.

11 Most importantly, I think, is that the UNB Digital Scholarship site seems to have been conceptualized as a centre – as a reference point. The centre also has an effective social media presence. Two doctoral students, Stephanie Pettigrew (who has managed several digital projects) and Richard Yeomans, act as digital managers, and they have developed an effective social media presence on both Twitter and Facebook.18 There is nothing else like it: the Digital Scholarship site is attractive, simple, and effective. It has few moving parts and that means it looks much more sustainable than the portal had been. While in some ways less ambitious than the Atlantic Canada Portal, it is perhaps a more pragmatic approach in that it looks scalable and more manageable; its developers appear to have learned the lessons of 20 years of digital obsolescence. It can be modified relatively easily, and there is little reason to imagine it will not still be functional in the 2030s. The rub, as always, will be funding, and the hope that this CRC-supported project is not allowed to die a slow death like the last one. The Atlantic Digital Scholarship page does a really good job of balancing the promotion and development of academic work, supporting students, skills development, and community outreach. It is not a perfect model of what might be, but it is an excellent model of what can be.

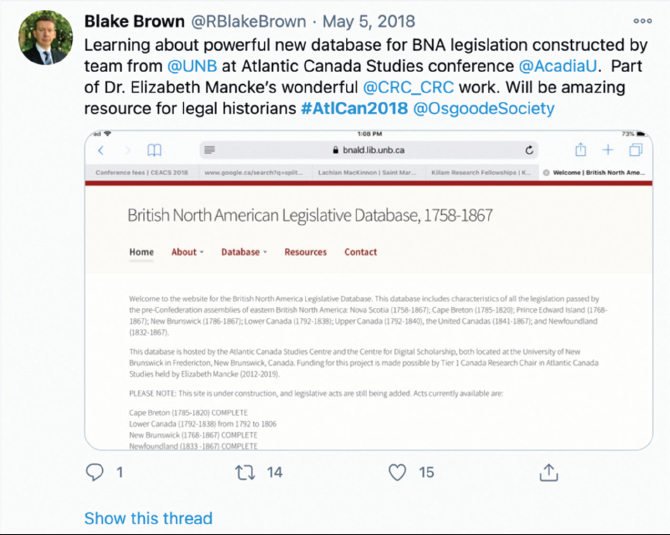

12 The use of social media matters. In 2012, Corey Slumkoski wagered that new digital tools and platforms now meant that “never has the history of [Atlantic Canada] been as well covered or as accessible as it is at present.”19 That is probably even more true today. Much of that, of course, owes to Acadiensis and its continued exploration of the region and its many peoples, identities, and histories. But part of it, as well, is due to a kind of explosion of history on the web in the region. This is evident on Twitter and Facebook, where academic and other historians, in universities, museums, archives, and many other locales are there – talking history. You could not attend the Atlantic Canada Studies Conference in Wolfville in 2018? See it on Twitter:

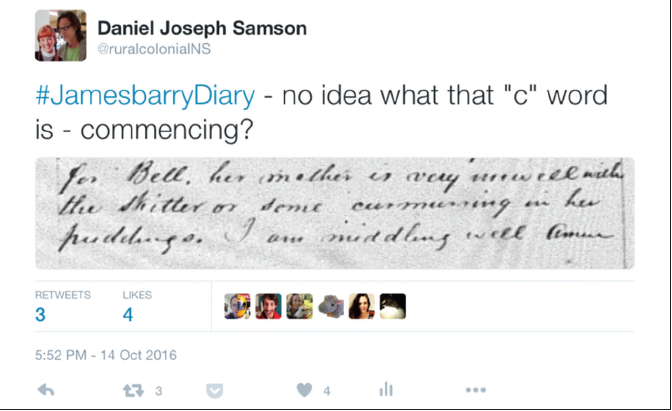

It is not the same as attending, but it does a fine job of reminding us who is active, what they are up to (as we await that Acadiensis piece down the road). I have made great connections on Twitter through tweeting this-day-in-historystyle posts from the diary of James Barry as I transcribe the diaries and write a book about his life. Twitter, and the hashtag #JamesBarryDiary has opened me to conversations with Scottish historians, where we discuss his occasional uses of Scots English and his regular commentary on Presbyterianism, with American historians of free thought, and with book historians fascinated by his collections and his publishing. And not a week goes by where I do not get a good question from curious observers with no specialized training – just curiosity, an interest, and a sharp mind.

13 Crowd-sourcing this kind of research offers the obvious advantages of numbers (more hands make less work), but also offers still more possibilities for collaboration. When I began reading the diary, I came across a word I did not recognize and posted it to Twitter.

The next morning, the tweet had had over 130 direct engagements, and I had suggestions from several historians, a professional paleographer, and an expert in Scots dialect, writing from Nova Scotia, Ontario, North Carolina, California, and Scotland.

14 This is a lovely example of “Twitterstorians” working together. Not only did I learn a new Scots word – “curmurring” as the rumbling in the stomach from flatulence – but I also realized significantly more about the context: that “skittering” is not just a silly word but Scots dialect for diarrhea and “pudding” was a slang for the stomach. What had been an opaque meaning was made clear, and helpfully so. My initial thought was that he was mocking his wife, though I was not quite sure how; in fact he was simply, perhaps playfully, describing her ailment. I could have looked that up in a dictionary of Scots-English, available online,20 but on Twitter I obtained a more nuanced answer and amplified my research network on Scots in the Atlantic World. Twitter advanced my research and helped build community.

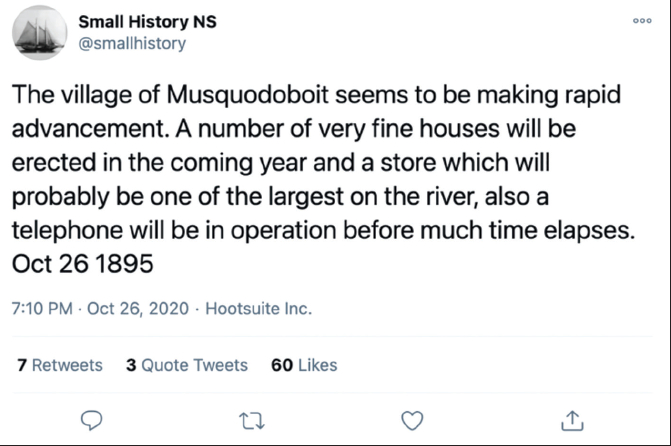

15 Twitter is great for this kind of engagement. It also offers a powerful reach into an audience hungry for accessible history. No one has done this better than Sara Spike with her Small History NS twitter project (@smallhistory). Every day, also in an on-this-day-in-history format, Spike tweets content from rural newspaper in Nova Scotia from the 1880s, 1890s, and early 1900s. These tiny slices of life – who was visiting, how the harvest was going, how the storm blocked the tracks, how grand was the show at the parish hall – whatever caught the attention of the rural editors.

16 Small History has more than 6,000 subscribers, an extraordinary number for a modest little microblog coming out of a village in the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia (albeit a house in the village that had a SSHRC post-doctoral fellow in history at UNB). Small History speaks to the power of simple stories accessibly told for audiences both academic and popular. Unfortunately, it also speaks to being a labour of love more than an economic viability – 6,000 followers is impressive, but it will not pay the rent – even in a little village on the Eastern Shore.

17 Money is a big part of this story, and much of the other good work underway exists because of good-sized grants. Building an effective digital project, whether one intended as a research tool (a database, a portal for data of some form – be that images, documents, or a database) or a public-history project intended for a non-specialist audience, requires typically a few small grants to get it moving, and a larger one to get the research and production fully in place. There are several really good research websites available. The most impressive from a research perspective is the British North American Legislative Database, 1758-1867 (BNAL). Organized by content, subject, titles, descriptions, and dates, the site is a searchable database for every piece of legislation passed in all the pre-1867 British colonies that would come to form Canada. An amazing resource for teaching and research, this took a team of researchers years to assemble and it is not yet fully complete. Like most of these projects, it works on a science lab model by turning the principal investigator into a project manager who employs a team of graduate student research assistants who do the groundwork. Funded by Elizabeth Mancke’s CRC money, and led by her doctoral student Stephanie Pettigrew, the project has created great experiences for students with training in digital tools, transcription, web-construction, and team-based work; and it now provides superb research support for anyone working in that time period. Less than two years old, and not quite complete, it is already producing significant research.21

18 Sites like the BNAL database also illustrate the manner in which most of us have become digital historians because such sites have become fabulous generators for new research. Nobody needs a course in Python to find amazing things there – to see patterns and connections one might never have noticed. But its longer-term use cannot be easily assumed. SSHRC is much better at providing funding for building exciting new things than it is for maintaining them. Most universities are building a digital scholarship lab of some sort, and have the skilled staff and capacity to host large projects. But short of some large infusions of cash, the challenge will be in maintaining them. Will we be using the BNAL next year in our courses and perhaps our research? Yes. But in ten years all bets are off. In her introduction to the database at the 2018 Atlantic Canada Studies Conference at Acadia University, Mancke stressed that one her aims was to minimize the complexity, the number of moving parts, and unmaintainable links in the hopes of making it as sustainable as possible. But reliant on money, resources, energy, and long-term commitments of support, all websites exist on the edge of obsolescence.

19 There are other excellent web projects out there. Most of these are databases: resources for the exploration and research of dimensions of the past. The best projects explore ideas rooted in connections that we do not always make. Voices of Identity | Vocabulaires Indentitaires is a SSHRC-funded bilingual database and research project led by Chantal Richard that combines Acadian and Loyalist texts from the period 1880 to 1940.22 They read across this large database utilizing the text analysis softwares Hyperbase and Sphinx to “compare the specific traits and discursive strategies” of New Brunswick’s most evident historically identifiable identities.23 Interdisciplinary, bilingual, and rigorous, Voices of Identity is an important resource on some very basic issues in politics, history, and identity in Canada’s only bilingual province. It is a resource that continues to produce valuable research.24

20 A literary scholar immersed in historical issues, Richard further extends her reach into New Brunswick Acadian history as a recent guest curator for an exhibition on at the Fredericton Region Museum beginning in 2019. The exhibit centres on Pointe Sainte-Anne, an 18th-century Acadian settlement on the site of what is today the city of Fredericton, and which was destroyed by British troops during the Seven Years War. The exhibit is housed in the museum, but has a large virtual component, including a GIS-based map of the Expulsion, and a virtual reality-based (VR) digital reconstruction that allows visitors to “enter” an 18th-century Acadian house. That alone is effective, and other projects are taking advantage of VR in similar visit-the-past initiatives. To visit a house that did not simply disappear in the sands of abstract time, but was razed by our country’s colonial state, is a powerful tool for understanding history as well as encouraging historical empathy and a sense of a relationship with the past. This kind of public-history project takes up much time and money, linking local museums, community groups, SSHRC, and the private sector.25 That this public-facing project, intended for on-site visitors, was mounted during the pandemic when access to the museum was restricted, must have been disheartening for all.

21 Much of the cost for these projects lies less in the hi-tech area and more in the labour involved in researching and building the spreadsheets that lie under the surface. This is evident in the Early Modern Maritime recipes project led by Edith Snook and Lyn Bennett.26 On the surface a fairly simple collection of historic recipes, it represents a SSHRC grant, plus additional support from UNB and Dalhousie, their respective universities, and years of research and data entry. Based in 47 manuscript and newspaper collections (some themselves existing as digital databases), the project unites a massive amount of material and makes it available for ongoing research. The result is a marvellous site for research and teaching in the burgeoning field of food history. This is very much a similar model for the database Keith Grant and I are building on print culture and books collections in colonial Nova Scotia.27 A scaled-up Maritime version of the site will require a larger SSHRC grant, but even our beta-version database required several small grants from the Nova Scotia Museum and Brock University. Almost all of that went into hiring student research assistants in Halifax and St. Catharines. That database has over 1,400 titles in 18 fields – over 25,000 pieces of data – all located and then entered by hand. Digital is not cheap, and it is not fast.

22 Social media and the general trend toward engagement and connectedness are offering new avenues for traditional forms of academic discussion. More importantly, they are also enabling broader and more inclusive forms of collaboration. Two digital projects underway in the region exemplify this new possibility. Under the leadership of Josh MacFadyen, the CRC in GeoSpatial Humanities at the University of Prince Edward Island (UPEI), the GeoREACH Lab is forging an incredible range of connections among everyone from students and faculty to government policy types and Islanders with stories to tell. Their projects range from building databases of commodities, to linking archived diaries and stories to landscapes, building social memory by eliciting the stories and facilitating their preservation. They are an archive and an expression of popular culture, a research group and a community builder.

23 Focusing on agriculture and land use in PEI, lab members employ a range of approaches that utilize varying combinations of basic data collection and analysis with social media, blogging, and community engagement. Some of the work, such as the recent release of “fir trade” data, can be approached as standard digital research projects. This GIS-based project examines “energy expansion” – that is the increased distribution and use of energy over time and space. Entering decades of data on the rail shipments of firewood in late 19th-century eastern Canada illuminates “both the geographic distribution of biomass energy production and consumption and the temporal trends during a period of intensive economic growth.”28 Other projects employ a range of approaches and technologies. The Back 50 project is a sophisticated collaborative ArcGIS data collection initiative disguised as a friendly chat with the neighbours over the back fence. There are different ways one could get at rural landscape change over times, but the Back 50 project goes directly to the public and asks them to tell the stories of the lands they know, of the lands that mean something to them. Landowners and resource producers are asked to participate – via blogs, Twitter, Facebook, online videos, the CBC morning show – and they bring their knowledge to the researchers. It is a marvellous project, from its sophisticated use of ArcGIS as a means to map land use across time and space to its playful public-engaging and thoroughly non-academic manner (with the title connoting both the past 50 years and a reference to the back 50 acres of a typical farm). It trains students, it develops useful data, it provides bridges to public policy developers, and it brings researchers and the broader community together in work of shared concerns. It democratizes research profoundly. It also pulls back the curtain on the ivory tower of research, allowing the community not only to see that research, and be able to use that research, but also to take part in it and to help shape its outcomes.

24 A similar spirit of collaboration underlies the Mi’kmaw Sovereignty project, which was initiated by Thomas Peace, of Western University, and Gillian Allen, of Kwilmu’kw Maw-klusuaqn Negotiation Office, which is part of the Mi’kmaq Rights Association. Mi’kmaw Sovereignty embraces the spirit of user-generated data and community collaboration. Working with the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq chiefs, they aim “to provide a springboard” for a “Mi’kmaw-owned and directed site” that makes the case for self-government – one that ensures “people never forgot they were and are a self-governing people.”29 The heart of the project is a user-generated database “whereby users upload and edit this content under editorial oversight from a Mi’kmaw governance structure.”30 Their aim is not academic, though it builds on the resources and skills of academic historians; their aim is academic-community collaboration – to build a digital platform that will become a site of Mi’kmaw empowerment. For Peace and Allen, their website will become another’s. It is a gesture that can advance the spirit of truth and reconciliation. Of course, Indigenous people are already crafting such digital outreach, such as the Wolastoqey-built Wabanaki Collection, or Ta’n Weji-sqalia’tiek, the digital atlas of Mi’kmaw place names.31 But Mikmaqsovereignty.ca speaks to the search for allyship, and working toward consensus and healing. The site itself remains a prototype, but we might also view it as a model for other projects that can advance shared research and community aims.

25 Other projects continue to do good work with simpler, older, face-to-face community building. Two SSHRC-supported projects spearheaded by Gregory Kennedy, the current Military Service, Citizenship, and Political Culture in Atlantic Canada, and its predecessor Minority Cultural Communities, Memory, and the First World War in the Maritime Provinces, have worked with provincial museums, and smaller local museums, to extend their research and community engagement as far afield as Chéticamp, Pubnico, and Bathurst. They are assembling student-led exhibitions, local pop-ups, and academic workshops.32 They are publishing blogs in Acadiensis and Borealia,33 but for the most part they are getting the word out using but not focusing on digital projects and social media. And the work is excellent. It is building truly regional projects, and yet ones that transcend older divisions – notably the compartmentalization of so much of Anglo-French work. It is also a useful reminder to someone like me arguing for the possibilities of extending reach via social media, that, at the end of the day, the aim remains to be somehow in those communities.

26 So where does Acadiensis fit in all of this? Can we begin imagining an augmented role for Acadiensis as not only the flagship journal for the field, where the best research is showcased for a professional audience, but as a point of coalescence for community-based, digital, and academic research? What this survey has made clear to me is two things: first, that while all of these digital projects are very good, each lives a precarious existence. None of us needs to go back and make sure the pages of our books still turn; none of us are worried that someone might not be able to read their book in ten years. The book is a remarkably stable platform. Long live the physical book, and the journal; but when there are ways to improve the book – to improve the scholar’s abilities to communicate and disseminate the ideas in the book, when there are ways to bring the very communities under examination in the book into its research and conception – we should be pursuing them. And it is here that I think that Acadiensis can improve all our research worlds by exploring ways to better make use of social media and social research. Can we create wholly digital essays, issues, volumes, or whatever that would bring digital practices more fully into view? This would entail not merely a weblink to be pursued if one desires – like a “further reading” page at the end of an essay – but something that presents digital research pieces in wholly digital form, more like webpages than articles. Can we build stronger connections to the region’s communities? Can we build research projects together? We can, and we are, but it is a piece-meal, project-by-precarious-project movement. Strengthening our ability to reach more non-academic people would help. One obvious way to achieve would be to give the digital editor the kind of support needed to actually generate digital work and build that digital presence. Perhaps the two-person co-editorship team could be split into print and web editors. Having the digital editor without the necessary resources will guarantee they have neither the time nor support to generate more than what is currently available.

27 The second thing that this survey has made clear to me is that all this work, both digital and analog, and whatever lies in between, resides in many locations, particularly in individual research “labs” and university libraries. The proliferation of digital labs is good, but it also spreads further afield what was already thin, making it less visible – in theory more accessible, but also simply harder to find. Coordinating this would require a lot of discussion amongst groups who spend half their time out of necessity fighting internally for budgets to keep them afloat; they may not welcome outsiders weighing in. But I think having a centralized body of some sort that would keep people abreast of initiatives and developments would be good. There is already a lot of coordination of specific activities; most of these people know each other: the archives groups, the museums, the university librarians, the labs, the academics, the consultants, the relevant provincial officials – be those the ministries of heritage or agriculture or languages. A realigned Acadiensis, both weightier in terms of its ability to facilitate work, but also nimbler and better able to work in multiple spaces, could be an effective linchpin in regional historical and interdisciplinary work. Of course, Acadiensis cannot do all this. But it can, as I suggested earlier, function as a kind of coalescent point for such initiatives, and it can work to open up and encourage conversations both institutionally and with other communities. There are already lots of conversations underway, lots of cross-fertilization and movement underway between research groups, portals, blogs, and project managers. But it is more catch-as-catch-can than coordinated endeavour. We can improve that.

28 I will confess here to being a bit of a utopian on the possibilities of the internet. Despite everything we have seen in the era of Brexit, Fake News, and Donald Trump, I still believe that people can learn and learn better by talking with one another. I still believe the internet can advance that cause, not alone, of course, but that it can help. I also think that as historians we are in a very good place to facilitate parts of that conversation – that as empiricists, as people grounded in evidence (in data!) and its careful weighing in forming arguments, we can foster work that is evidence-based, convincing, and rooted in our communities and their worlds.

29 There are of course risks in digital practices. A long-held basis of historical methodology involves an immersion in the sources. Milligan and Hitchcock remind us that there is a difference between using sources (for example, keyword searching digitized newspapers, as a substitute for reading analog versions cover-to-cover) and employing digital methodologies (for example, using text-mining software as a tool of distant-reading large sources).34 Not only do we risk losing context in our sources, but we also risk losing context of our sources. Lara Putnam reminds us that there are potential losses in how historical knowledge of place is lost as we have moved increasingly to internetbased research. On the internet, an amazing source can often be found with the click of a mouse. That frees us from potentially long and expensive travels to far-off archives, but it can also take us away from the actual locations of our research: places overflowing with helpful intermediaries (archives, archivists, and the locations they serve as well as the overheard archives conversation about that source you did not know about – the one that is not online yet). I can find amazing sources, sitting at my desk in St. Catharines, but I lose the knowledges that comes from being in Halifax or Pictou, talking to local museum people, talking to the guy that runs the BnB. In Putnam’s terms, the internet offers us “disintermediated discovery,” facts shorn of cultural context, “shortcuts that enable ignorance as well as knowledge.”35 The very nature of our communities, and our contexts, can change. Thinking about such changes, about such new modes of being researchers, is important.

30 There is a branch of education research called Networked Participatory Scholarship (NPS). An entire literature has developed around it, including its own journal. I am no education theorist, but in its basic form NPS gets at a lot of what I want to advance here. It is about using the capacities of social media and interactive digital platforms to build networks to advance research.36 These range from the very simple, quick communities of engagement, such as those formed on Twitter when debate and discussion can advance thinking, enable collaboration, and build research networks, to more elaborate structured networks. These may be designed specifically for particular purposes that can range from planned online gatherings (effectively online conferences) or broad-based digital community engagement and digital literacy campaigns such as the beautifully utopian (and decidedly Maritime!) Antigonish 2.0 movement that flourished briefly a few years back.37 In all these cases, the basic aim is a commitment to open sources, digital literacy, collaborative scholarship, and community engagement. There are models here worth examining.

31 The successful digital work we have seen here has been for the most part either supported by large grants from SSHRC and yet is often still reliant on unsustainable amounts of free labour by emerging and precarious scholars who will not be able to keep this up, and should not be expected to do so. Most of them are building CVs in the hope of getting a job, whether in the academy or elsewhere – showing their chops, be those in the skilled digital labour market or in universities desperate to improve community engagement and show off their digital presence. Borealia, Small History, and any number of smaller initiatives such as the Historic Nova Scotia app38 are all being run on a shoestring, and not a university-level shoestring but a month-to-month household shoestring. Not all of them will survive, and perhaps some of them do not need to; but under the current conditions, and moreover under consumers’ current expectations, none of them will. Many today expect such free access. Open access is a powerful social movement, but we in the academy have been tricked into believing our world is truly open access. It is free to us because our institutions pay huge sums to buy “open access” journals. And the blogs, and the apps, and student energy all blur into the same mass market of very expensive free knowledge. Even NiCHE folks who built a magnificent and so far sustainable structure did so with a lot of money; but today it still requires the free labour of dozens of scholars, some established and secure, some students, some precarious – but it is all free. That has to change. That again is something well beyond the capacity of the journal – but positioning itself better in the conversation is well within its scope.

32 These user-generated and community-based research strategies will not work for everyone, or every research question. We are humanists, digital and analog alike, and we are driven by working with people. And when we meet people great things can happen. Two summers ago, I spent a day at an archaeological dig in Stellarton, Nova Scotia. I did not know a soul. By the end of the day I had been put on the trail of a GMA miner from Litchfield, England, who had bought a farm and retired as a gentleman farmer in Colchester County, made contact with the Nova Scotia Industrial Heritage Society, and was taken up the East River to an 18th-century mill site near Springville by Pictou County historian John Ashton. I have also spent two Pictou County afternoons driving around Six Mile Brook and Rogers Hill with Tim MacKenzie, another Pictou historian who can find every 19th-century farm foundation in West Pictou, and knows who lived there. He read Barry’s diary years before me, so he already knew the people I sought. We have all had such research experiences; we all find people who know more than we do, or at least know things we had never have stumbled across in the archives. None of those experiences required social media (except that I learned of the dig on Twitter!), and I cannot spend every day in Pictou County. But the digital world allows me to spend time there, reconnect there, extend networks there, and work with the people I met there. The power is in building and maintaining the connections. What I am urging here is that we make better use of the digital world to bring that closer to hand: it would better serve our research as well as the communities we value.