Article

Scissors, Embellishment, and Womanhood

The Material Culture of Acadian Sewing to 1755

Des recherches archéologiques portant sur quatre établissements acadiens ont révélé la présence d’un nombre curieusement élevé de paires de ciseaux de couture et de broderie dans les fermes familiales. Le présent article examine ces artefacts et constate que la proportion élevée d’outils pour travaux délicats et le caractère décoratif d’un grand nombre de ces travaux révèlent un intérêt culturel pour la broderie et l’ornementation, et un lien avec l’évolution des conceptions européennes de ce qu’une femme distinguée doit accomplir. Ces signes de statut étaient interprétés de façon différente dans le contexte colonial acadien, ce qui a peut-être contribué à donner aux observateurs de l’extérieur l’impression que les Acadiens étaient indolents et ne respectaient pas la structure de l’autorité coloniale.

Archaeological investigations of four Acadian settlements have revealed a curiously high number of pairs of sewing and embroidery scissors present at the homesteads. This article examines those artifacts and finds that the high ratio of fine-work tools and the decorative nature of many of the examples reveal a cultural interest in embroidery and embellishment, and a connection to changing European conceptions of genteel feminine accomplishment. These status signals read differently in the Acadian settlement context, which may in turn have contributed to outside observers’ impressions of the Acadians as indolent and without respect for the structure of colonial authority.

fallen leaves and rubbish that the wind has blown into the gutter

or street corner, lies all the passion of some woman’s soul finding

voiceless expression.1

1 THE ACADIANS LIVING IN NOVA SCOTIA PRIOR TO THE DEPORTATION of 1755 developed a rich textile culture, one originally based on the aesthetics of France and New England, but which, by the early 1750s, was in the process of developing localized, regional variations. Very little documentation exists that describes the ways in which textile and embellishment work intersected with family and community life, but an examination of the tools used in the production of clothing can give insight into the ways in which the material culture of Acadia helped to define a community. In examining a tool like the simple scissor, we can see the emergence of new patterns of social hierarchies, gender relations, and division of labour. Cultural expectations from France associated leisure activities such as embroidery and decorative sewing tools with women of high status. The presence of decorative scissors and tools associated with embellishment and needlework suggest that some of the women living in Acadia were engaging in those activities along with garment production and basic maintenance. This subversion of expectation, for a group often described by contemporaries as low-status peasants, contributed to anxieties felt by colonial leadership over the ways in which Acadian culture was beginning to diverge from that of the metropole.

2 Acadian society functioned on a social hierarchy, even if there was less differentiation between status levels than those in larger population centres. Naomi Griffiths and Maurice Basque disagree on whether Acadian society was levelling over time or stratifying, based on occupational statuses and the frequency of marriages with French officials.2 Anne Marie Lane Jonah and Elizabeth Tait find evidence for both takes, suggesting that there was a consistent social elite, but one which was far more permeable than in other regions. The material culture Jonah and Tait examined suggests little difference in wealth and belongings between the elite and non-elite, finding some stratification but few extremes on either end.3

3 Status was often conveyed through possessions, and material culture studies provide a valuable window into that mechanism. James Farr describes status signalling through possessions as a “primary characteristic” of the early modern period. The clothes someone wore, the kinds of food they ate, and the types of vessels used for food and drink would have been expressions of standing as well as individual preference.4 Lewis Binford made one of the early arguments for using material culture as a lens for the examination of social systems, in that the primary function of objects’ stylistic properties was the creation of a consistent visual identity with which a group could identify.5 Types of decorations and embellishments on objects, in other words, were a means of projecting both status and community membership. Arjin Appadurai places similar intrinsic value on the entire object, calling culturally valued items “guardians for the status systems.”6 Belongings, in this sense, are gatekeepers that help distinguish between those who have access to social power and those who do not.

4 Decorative sewing equipment can often help provide status, and archaeologist Mary Beaudry has found several examples of sewing tools used for the projection of status and influence in colonial-era New England settlements.7 Like New Englanders, Acadians – even in distant agricultural settlements – had access to both necessary and luxury items thanks to a combination of trade and local manufacture. Decorative scissors and other small goods such as silk embroidery thread were available first through traders like Henri Brunet and later through the port at Louisbourg, as were dyes like indigo and vermillion.8 Fine sewing and its associated toolkit played a crucial role in the definition of early modern elite European womanhood, and the presence of embroidery scissors in pre-deportation Acadia sheds new light on some of the Acadian value systems and means of navigating complex social structures in the colonial environment.9

5 Sewing is commonly associated with women’s work in the modern eye, though it has never been an exclusively gendered activity. Sewing tools including scissors, pins, and thimbles were part of soldiers’, farmers’, and sailors’ regular kits from the medieval period to the modern day.10 Embroidery and fancy work specifically became more closely associated with performative femininity in the 17th and 18th centuries, and artifacts associated with women’s labour and, more particularly, labour and the body, gained a particular kind of importance during the same period.11 Personal artifacts like bodkins and embroidery scissors were worn visibly among the clothes, were focal points in portraits, and became objects of social display and status negotiation.12

6 Visual symbols of textile labour carried a great amount of social meaning in the early modern period. The accoutrements of sewing and fine work – scissors, needles, bobbins, and lacemaking pillows, for example – appear frequently in depictions of both elite and non-elite women.13 Images of women engaging in needlework abound in continental portraiture of the time, their tools focal points of the scene. The young embroiderer in Jean-Etienne Liotard’s painting Jeune fille brodant (c. 1740-1760), for instance, has been captured in a moment of preparation, her large tapestry needle threaded and poised, her scissors attached to her apron by a blue silk ribbon that matches the colour of the thread – likely also silk – in her lap. Stephen Daniels described the use of sewing tools like these in portraiture as “emblems of activity” – markers of the sitter’s industry and skill.14 She is engaged in decorative needlework rather than plain sewing, and the ribboned scissors with decorative handles become a symbol of her elevated status. The luxuries of silk ribbons and threads, fancy embroidery snips, and the tapestry in her lap show that she spends her time on refined labour instead of subsistence work – a pastime acceptable for women of higher socioeconomic status but perceived as misused time for those of lower status unless the items were being produced for wages or for sale.15

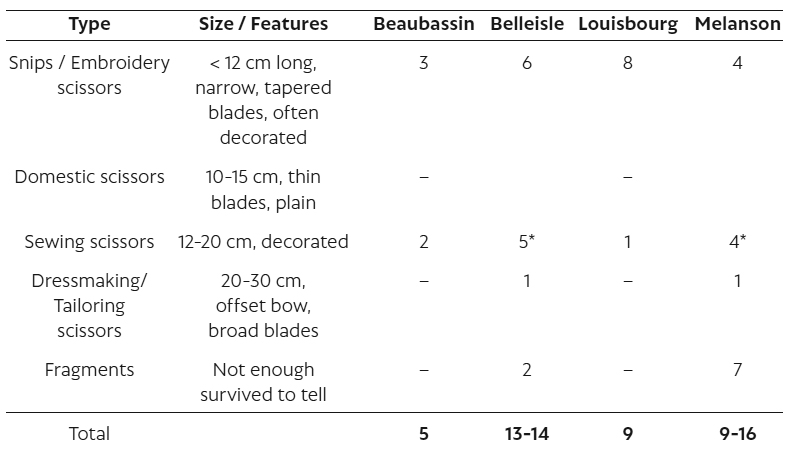

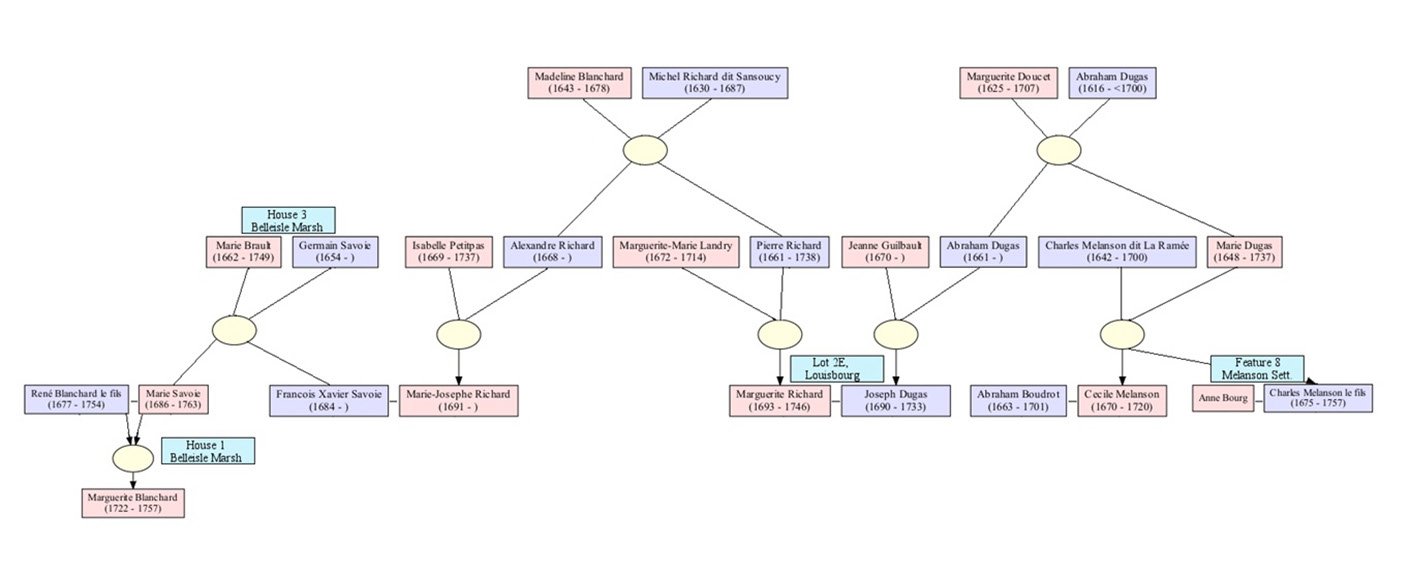

7 Tensions between conceptions of productive time versus misused time are apparent in the way in which the term “luxury” was transformed during the 18th century in France. John Shovlin has found that, prior to the 1750s, the word “luxury” referred almost entirely to the unearned use of elite goods by those of lower status. Concerns revolved around the blurring of social boundaries, much as earlier concerns about the poor usurping the clothing of the rich, led to sumptuary legislation in previous centuries. Rising access to consumer goods and non-subsistence items confounded pre-existing categories of those who could afford elite goods and those who could not, an entanglement that changed the meaning behind women’s use of luxury sewing tools.16 Embroidery and sewing scissors found at some Acadian settlements – Melanson, Beaubassin, Belleisle, and among the Acadian residents at French Fortress Louisbourg (see Figure 1) – indicates that Acadian women were also engaging in this kind of symbolic negotiation.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Scissors

8 Scissors are a commodity – an object with both use and exchange value – once they leave the manufacturer and as they pass through the hands of traders. They become a tool when they reach the first user, with decorative versions also becoming status symbols and reflections of idealized domesticity. All of these scissors have the potential to become symbols of generational bonding when given from mother to daughter, grandmother to grandchild.17 As such, they move smoothly between Kopytoff’s separate spheres of object life – a theoretical framework wherein a physical item acquires and develops specific meanings across its lifespan, accumulating different culturally constructed roles as it passes through multiple hands. In this case, scissors moved from subsistence items necessary for basic tasks, to prestige items, to markers of relationships and social exchange.18 Decorative tools associated with women’s labour added a layer of prestige to regular chores, items such as silvered scissors and decorative snips translating a subsistence activity into an elite one.19 In her book Findings: The Material Culture of Needlework and Sewing, Mary Beaudry sets out a framework with which to classify handwork and sewing tools. She separates practical work from the primarily decorative, and creates a separate category for work intended for sale which may be of either sort. In this schema, the types and quality of the tools used for production give clues as to which category of work was being produced, and the social standing and display practices of the needleworkers. The ways in which sewing tools are embedded in different forms of labour provide a launching place for discussion on gender roles, status, and community.20

9 There are no images of scissors that can be directly related to Acadia, and scissors only appear a handful of times in inventories of Acadian households from the Louisbourg archives. Records of imports appear slightly more frequently in merchants’ invoices and traders’ inventories.21 The rest of what we can learn must be derived from analysis of the physical artifacts. Scissors are an artifact type almost predestined to be some of the rare surviving evidence of sewing work in colonial Nova Scotia; while the wet and acidic soil of the Maritimes consumes textiles rapidly, the iron, copper, and brass used to make scissors survives much longer.22 The collection of pairs of scissors and scissor fragments recovered from Acadian sites make up one of the largest diagnostic populations of sewing tools in these assemblages, and every household engaged in any kind of domestic textile or garment production – that is, the vast majority of settler households – would have possessed at least one pair. Beaudry’s examination of colonial-era sites in New England found that the predominant ratio was a single pair of utility scissors per site.23 The numbers are intriguingly different, and much higher, in pre-deportation Acadia.

The collection

10 Scissors are standard domestic tools, but the variety and quantity of scissors owned by a given family was not solely based on practicality. Some of the pairs of scissors found during archaeological excavations at the Acadian settlements of Beaubassin, Belleisle, Melanson, as well as Acadian households at Fortress Louisbourg were decorated prestige items, and the assemblages contained many more pairs than would have been necessary for general survival activities.24 The number of scissors found at these Acadian sites to date is equal to or larger than the number of adolescent and adult women living at each, a ratio that remains consistent regardless of the reason the site was abandoned. Only the quality and embellishment levels of the scissors differ, which reveals something about how the women living in each space considered and performed femininity and leisure. The majority of the artifacts found were embroidery or fine-work scissors, and a high proportion of scissors associated with embroidery and other non-subsistence-related embellishment work is another marked difference from the assemblages Beaudry describes from colonial New England.

11 Excavations at Belleisle revealed seventeen partial scissors or scissor fragments, adding up to a potential thirteen or fourteen pairs. Fifteen fragments and pieces may add up to anywhere from nine to sixteen pairs of scissors at Melanson. Five have been found so far at Beaubassin, and Fortress Louisbourg’s collections contain ten artifacts which may add up to eight pairs of scissors associated with pre-expulsion Acadian occupation. One further fancy set was listed in a probate inventory for Jeanne Thibodeau, a resident of Louisbourg from 1713-1741. Some of these items were undoubtedly designed and used for sewing and tailoring, while others may have been general-use domestic scissors.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1

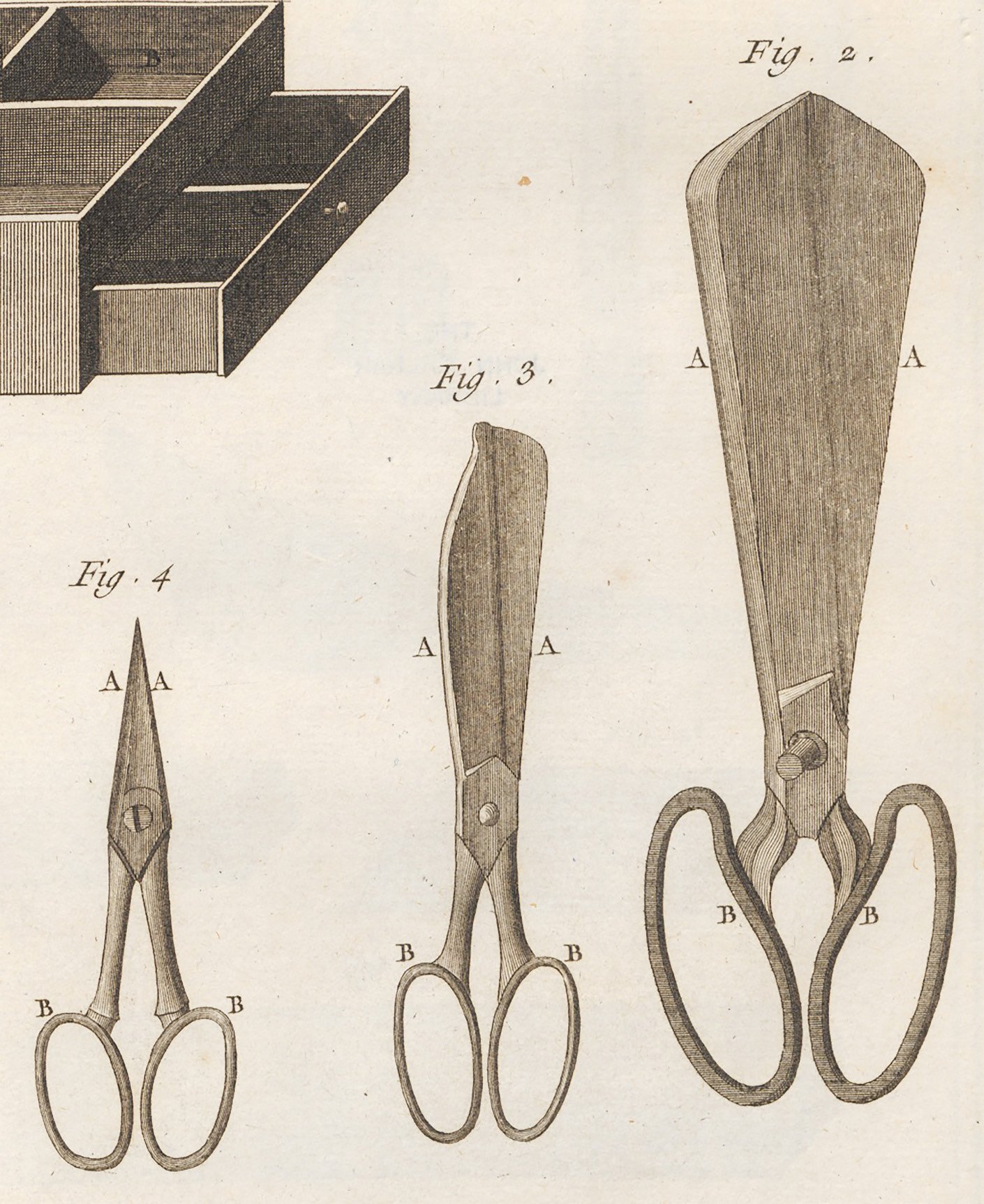

12 Studies of scissors recovered from various colonial and post-colonial sites have enabled the production of a typology and chronology of scissor styles, with size and blade-to-handle proportion the key factors in the identification process.25 Types of scissors can often be directly associated with specific activities, depending on size and certain diagnostic features of the blades and handles.26 The Ministère de la Culture in France categorizes cutting tools found in the early modern and modern period by length, a quality that we can extrapolate even from partially damaged artifacts.27 The differences between standard multi-purpose domestic scissors and tailor’s shears or lace-makers’ scissors are easy to list, but more difficult to discern in practice. And as anyone with a sewing-box is well aware, scissors originally intended for one task are often borrowed for others by incautious members of the household and general-use scissors can be repurposed for sewing tasks in turn.

13 Domestic scissors in the middle-size range are the most difficult to specifically associate with sewing, but their presence around other items used for garment and textile work is a strong indicator of their purpose. Decorative details, such as silvered plating or handles with carved or moulded embellishments as well as the width and style of the blades, become useful secondary indicators of function. Scissors of similar style and different size categories are found together more often than not, including a set of silver-plated scissors and snips from Beaubassin, and the pairing of sewing scissors and snips found together in the Blanchard house in Belleisle.28 The combinations, sometimes found in conjunction with pins and other sewing tools, likely indicate the presence of a sewing kit, or huswife, and potentially an area of a home or exterior space used for textile labour.29

14 Five pairs of scissors have been found during archaeological excavations at Beaubassin, three of which were silver- or tin-plated to give a silvered appearance.30 The Belleisle scissor assemblage contains a broad mix of plain and fancy scissors, about half of the items small enough to be embroidery snips. Two of the pairs of larger domestic scissors were found in association with snips, suggesting they were used for sewing rather than kitchen chores, and one larger pair has an extended rivet, of the type seen in contemporary illustrations of tailors’ shears (Figure 2, far right). Excavations of the Melanson settlement on the Annapolis River revealed many small, corroded pieces of larger scissors and snips, most of those apparently plain in design.31 Lot 2E at Fortress Louisbourg, the home of the Widow Dugas, provided one pair of mid-range scissors and four pairs of snips of varying sizes, one pair with fancy decoration similar in style to the snips recovered from Belleisle.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

15 It is difficult to judge the original size of the sewing tool collections during the pre-deportation period, as only a small portion of identified Acadian features have been tested or excavated, and the artifacts that have been recovered may only be a small percentage of the original. It is possible that many pairs of scissors were owned by members of the Savoie family in Belleisle, for example, but were removed over the years or packed and taken during the deportation. We also have few chronologies available for the finds at these sites, and only the Melanson settlement offers up one house with very clearly delineated occupational time periods; so any evidence for changes in ownership patterns over time has also been lost. These snapshots in time nevertheless give us a glimpse into status signalling and the use of domestic spaces during the build-up to 1755.

Beaubassin

16 Beaubassin, a large Acadian settlement founded on the Chignecto isthmus c. 1671-1673, was destroyed by fire in 1750. Sections of the site were disturbed thanks to construction activities associated with Fort Lawrence (c. 1750) as well as later use by farmers, which has made it difficult to associate artifacts with specific households.32 Beaubassin’s scissor collection comprises styles predominantly associated with fine work and precise dressmaking. Two pairs, one pair of sewing scissors and one pair of snips, were found together in the same lot, both plated – likely with tin – and were retrieved and conserved mostly intact (Figure 3). The scissors are mid-17th century in style, the combination of wrapped loops and rectangular cross-section of the hafts confirming an early manufacturing date. The fancy embroidery snips have shaped hafts with distinctive curves and separate, symmetrical loops, indicative of later 17th- into 18th-century manufacture.33 These plated snips show an attention to detail and a level of luxury expense that elevates them above basic workhorse domestic scissors.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

17 The two pairs were found together with other household artifacts beneath a burned layer of earth outside a domestic structure. The close spatial association and the location in which they were found can tell us much about the use of space. They were discovered along the south wall, the side of the house which would receive the greatest amount of sun.34 The house door was not found in the south wall during excavations, indicating that the sewing kit was not secreted beneath the front stoop as has been seen in other locations.35 It is likely that the scissors were discovered where they had been used, the owner sitting in the afternoon sun with her handwork and her mending. This use of public space for domestic work was common, turning an intimate activity into shared experience.36 The prime loci for sewing work prior to the advent of electric light were the hearth in the evenings and by windows in the daylight, spaces designed for the availability of light and heat. Moving to the outdoors, a practical solution in geographies and seasons where weather permitted, removed the action from the closed world of the family and into communal space.

18 The other pairs of scissors from Beaubassin are smaller, two with blade shapes associated with embroidery scissors. All three were found in proximity to beads, two in association with glass beads and a bead in the process of being made, and the last with both glass and stone beads and a small sewing awl.37 The groupings of sewing tools suggest they may have been remnants of abandoned sewing kits, the small snips likely used for fine handwork and embellishing clothes – possibly using the beads found nearby. Embroidery snips in general indicate the presence of feminized aesthetic work, while the extra expense of plated tools adds a layer of prestige and social display. These scissors were badly crushed and bent at some point before the process of being discarded and interred, perhaps by fire (Figure 4). The damage incurred makes it difficult to tell if there was once a maker’s mark or ornamentation on the handle, but the high placement of the rivet, approximately a third of the way down the blade, indicates an early manufacturing date.38

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

19 The surface is plated with a silvered coating, most likely tin, which makes these small scissors a luxury item. Silver plating was a common 18th-century method used to make brass items look like solid silver, and both brass and silver scissors had a distinct advantage over iron ones in that they were protected from rust.39 Those who could afford to do so would sometimes indulge in an upgrade from wrought iron to actual silver, as did one successful French seamstress in 1770 – purchasing silver scissors along with a matching silver thimble.40

20 The prioritization of expensive scissors – possibly a second fancy set, if this pair was part of one of the two sewing kits found nearby – indicates an emphasis on gendered tasks alongside socioeconomic status playing part of the owner’s sense of self. Wealth could be displayed through gems and buckles, through expensive fabrics and fancy stockings, but to go to the expense of purchasing silvered sewing tools incorporated embroidery and fine work as an expression of feminine identity. In The Subversive Stitch, Rozsika Parker separates the categories of plain sewing and embroidery on both practical and ideological levels. While plain sewing was a requirement to furnish a household, embroidery during the 18th century signified a higher socioeconomic status – a refined and aristocratic lifestyle where access to leisure time for art was proof of gentility and economic privilege. The art of fine work was intrinsically connected to the status of a household, and part of the way in which a genteel family maintained its social position.41 In the first half of the 18th century some activities considered appropriate and legitimate pastimes for the elite were in turn considered illegitimate for those of lower status, and became known – derogatorily – as luxury when indulged in by those of lesser socioeconomic status. The notion that those of lower status could usurp the privileges of the elite, and so confound the natural hierarchies, caused tension and anxiety among commentators. The problem lay not in the activity itself, but in the nature and entitlement of those who engaged in it.42

21 Silvered scissor sets and fancy snips found at Beaubassin reveal the presence of a system that may have considered non-subsistence sewing as one of these markers of elite womanhood. This is not the kind of activity commonly associated with the archetypical “outpost” or “border” labels often used to describe Beaubassin.43 Rather, it speaks to an investment in social norms that separated subsistence living from leisure crafts and used the latter as a venue for conspicuous consumption. The large settlement furthest away from the concentrations of European power at Fort Anne and Fortress Louisbourg, Beaubassin is also the location where the highest number of fancy scissors have been found to date. Those living there appear to have been in the process of developing their own social elite – beyond the malfunctioning seigneurial system or ranks of the deputies – one reflected in their dress accessories and the tools used to produce that dress.

Louisbourg

22 The Acadian-owned lot that revealed the bulk of the scissors in Louisbourg was lot 2E, one of four excavated houses known to have been inhabited by Acadians. The family in residence there immediately prior to the British occupation consisted of Marguerite Richard (the Widow Dugas), her second husband Charles St. Etienne de la Tour, and four daughters. Most of the pairs of scissors are of the size associated with snips designed for fine work and embroidery, and all but one can be dated prior to 1750, when the original house was destroyed and the assemblage caught in the surrounding debris.44 The other is of unknown date but in a style common to the early 1700s.45 It must be noted that there is a chance that some items found there could be from the brief period of the British occupation, from 1745-1749. Any remains from that brief occupation would have been mingled in the rubble from the house’s demolition in 1750, a common problem with multiple-use sites.46

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

23 Of the four pairs of mostly intact snips recovered from the site, three are on the larger end of the category, and one much smaller (see Table 1). They range from standard sewing scissors to delicate snips of a size appropriate for clipping threads and other extremely fine detail work. Two of the larger pairs of snips are plain-handled with no decoration, and the third has a haft decorated with geometric cast iron designs (Figure 6) – a type of decoration most frequently found on embroidery scissors.47 The fancy snips are not unique to the Acadians, as an identical scissor handle was found across the street in Lot 2I, residence of the de la Vallière family (Figure 7). These pieces are so similar that they could easily be two halves of the same pair, except that they are both designed for the same side. An increasing number of decorated scissors were being mass-produced by the mid-18th century, and these finds may represent two different pairs cast from the same mould.48 A similar pair of decorated snips has been found at Belleisle, suggesting that they may have purchased their scissors from the same source – or at least that someone in the Blanchard family had an eye for the current fashions of France. Louisbourg itself was part of Atlantic trade routes, and, while fashions were delayed getting to Île Royale from Paris, those living in the fortress were still aware of and interested in following the fashions of the empire. The variety in size indicates a variety in the tasks being performed, the presence of sewing scissors indicating engagement in either dressmaking, tailoring, or both. The emphasis was still on fine-work tools and the attendant Eurocentric marking of feminine-coded tasks.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

24 A 1741 probate inventory of the possessions of Jeanne Thibodeau, an Acadian woman living in Louisbourg, includes a description of scissors with a cover.49 The Musée le Secq des Tournelles in Rouen has a large display of sheaths of the sort most likely described in the inventory, and Wright’s Portrait of a Woman (c. 1770) shows a metal sheath for the gentlewoman’s scissors on the table (Figure 8).50 Thibodeau’s scissors and cover were likely similar – small tools meant for both use and display as status objects. The contents of her sewing basket listed in the same inventory provide more information about her habits, including 151 skeins of linen thread, six skeins of colourful silk thread, and ribbons, taffeta, and braid.51 By all indications she was engaging in handwork appropriate to a genteel woman rather than purely practical or subsistence sewing.52

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

Belleisle

25 Belleisle was an older community than Beaubassin and survived a few years longer; it was destroyed in 1755.53 As many as 13 or 14 pairs of scissors may be represented in the Belleisle assemblage, at least half directly connected to dressmaking and fine work rather than kitchen or general household use. Unlike Beaubassin, surviving property records mean that we can directly associate the homesteads with their residents, and many of the artifacts with their owners.54 Belleisle lies up the Annapolis River a few kilometers from Port Royal, the region that Clark described as “liv[ing] in the same bucolic fashion as their cousins in Grand Pré and Beaubassin,” without marks of European “elegance.”55 This has since been proven both true and untrue at the same time – those in Belleisle lived in similar fashion to their cousins at Beaubassin, but with access to and use of similar sorts of luxury goods and status markers as those in urban areas like Louisbourg. The inverse of Clark’s statement is also true as far as sewing tools and linens are concerned: the fanciest scissors and pins for the finer linens were found at Beaubassin, farthest from the fort, and the goods found at the Gaudet, Savoie, and Blanchard houses in Belleisle were plainer. The trend continued, as will be seen in the following section, with the plainest sewing tools of all found at Melanson, a site in the old banlieue of Fort Anne.56

26 The Blanchards, the family who owned the property where most of the sewing tools were found, were among the wealthier residents of Belleisle. Brothers René and Antoine held four separate plots of land, sharing maintenance with brother-in-law Pierre Gaudet.57 Pierre Blanchard was listed as a deputy for Belleisle in 1740, empowered in a letter from Mascarene to organize road building around part of the marsh and arbitrate fence disputes between neighbours.58 The Blanchards’ wealth in the earlier censuses and Pierre Blanchard’s later status as a deputy makes the Blanchards a nominal part of the so-called “elite” Acadian families – mostly defined as including the wealthiest and most politically connected families, often centered around the Melansons and de la Tours.59

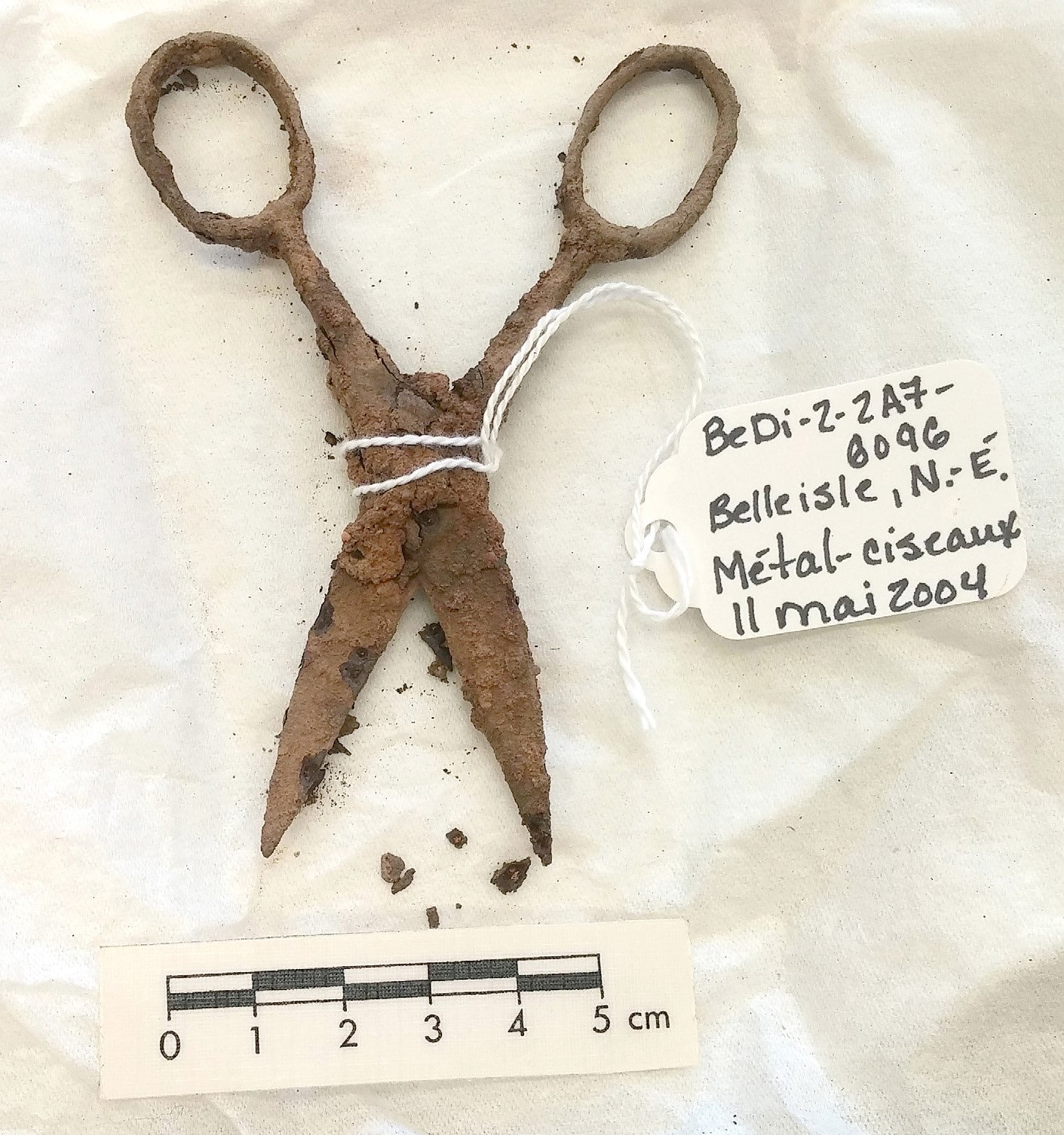

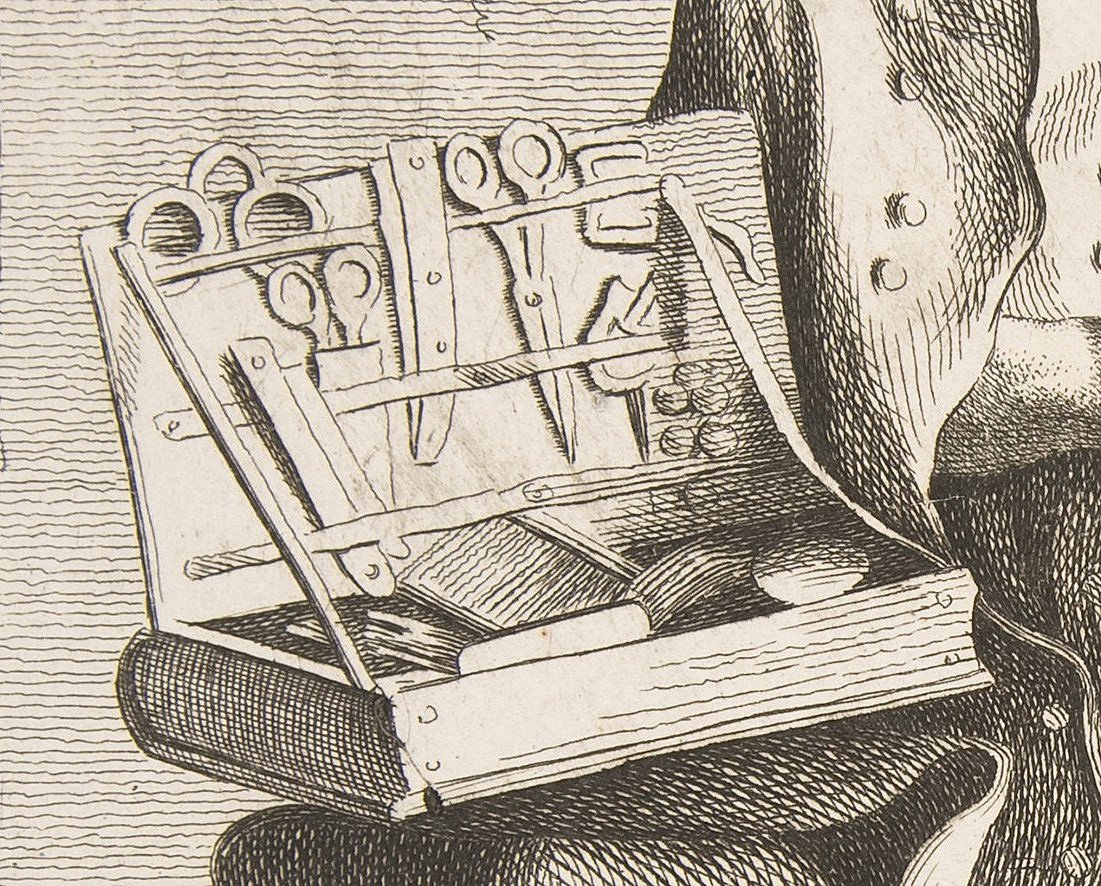

27 The most complete set of scissors to date was uncovered at Belleisle, at the house of Germain Savoie and his family (Figure 9). The intact scissors are heavily corroded but in otherwise good condition and bear a striking resemblance to snips on display in an image of a peddler’s sale case from 1742 (Figure 10). Physical details confirm a likely manufacturing date in the first or second quarter of the 18th century, and, as with all these examples, bear no visible maker’s mark. The second set from the Savoie house were found in conjunction with domestic waste, including pottery sherds and pipestems.60 The likelihood, given the size, shape, and context, is that these were domestic scissors used for kitchen and other household tasks. Germain’s wife Marie Breau dite Vincelotte died in 1749, so it is possible that one or both of the pairs of scissors began life in her sewing kit, moving to that of her daughter-in-law or into the kitchen following Mme Savoie’s death.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10

28 Across the path, about 400 metres away at the Blanchard residence, some more decorative items have been found. The overall collection here includes at least four pairs of snips, a possible pair of tailoring shears, and at least one set of small sewing scissors out of group of, at minimum, nine separate pairs. Most are relatively plain, though one pair of snips was found with ornate hafts and blades similar to those found in Louisbourg (Figure 11).61 These snips are ornate, cast in a decorative style suggesting a mid-18th-century date of manufacture.62

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11

29 The presence of three different kinds of sewing scissors at the Blanchard house suggests activities beyond basic garment production and repairs, carried out by more than one individual. Assuming one owner for a set consisting of a pair each of shears, scissors, and snips, and the fancy snips as a gift or a special pair, we are left with enough variety and quantity for up to three members of the household to be actively engaged in textile labour. Each woman living there would have had her own sewing basket with an assortment of tools, including needles, thimbles, scissors, and other assorted tools such as bodkins and awls.63 René Blanchard’s wife Marie Savoie – daughter of neighbour Germain Savoie, discussed above – and their unmarried daughter Marguerite Blanchard are the probable owners of the sewing equipment found in association with the Blanchard home.64

30 The assemblage is suggestive of a craft culture in Belleisle where ornate tools were less valued than in Beaubassin. They were by no means cut off from luxury goods, but they may have been less able to access the kinds of trade goods that flowed through more connected communities. The fancy plated scissors and snips found in Beaubassin have no equals in Belleisle, though the similarity of the fancier snips found at the Blanchard house to those at Louisbourg open the possibility that the Blanchard snips were purchased there. While Acadian women at Belleisle certainly valued fine work enough to own tools designed for its execution, the simpler designs and material composition of the scissors suggest either a lessened ability to access the fancier silvered and decorated pairs, or somewhat lower priority placed on this particular form of feminine-coded status display.

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12

Melanson

31 The Melanson settlement was established c. 1664, with the marriage of Charles Melanson dit La Ramée, son of Pierre Laverdure, and Marie Dugas, the daughter of Port Royal armourer Abraham Dugas. The pair settled on a large piece of land in the District of Kespukwitk, on what is now known as the Queen Anne Marsh on the Annapolis River, approximately six kilometers west of Annapolis Royal.65Melanson remained small, with only nine households at peak occupancy, but the relative affluence of the residents along with surviving maps that identify the ownership of specific residences contribute to making Melanson a useful window onto earlier Acadian settlements despite the low population. Most importantly, unlike Beaubassin and the Acadian houses in Louisbourg, the Melanson site remained undisturbed by later settlement activity following its destruction in 1755. The preserved site allows for a more accurate archaeological record of domestic life.

32 One of the features excavated at the Melanson settlement was the homestead of Anne Bourg and Charles Melanson, son of the founder Charles Melanson. Structures on the site were demolished on four different occasions between 1700 and 1755, each incident leaving its own evidence behind. A fire in 1707 and another in the late 1730s were the most destructive events, and the inhabitants of the 1730s structure – the third on the site – capped the ruins with clay and rebuilt, leaving some damaged artifacts of domestic life beneath the layers. A midden on the property has been associated with all four occupations of the site, and fragments of either one or two pairs of scissors discovered there appear to be associated with materials from the earlier occupations, c. 1690-1730.66 Unfortunately not enough remains of these artifacts to make specific identifications as to type, size, or purpose. Two pairs of scissors survive in better condition from the fire in the third structure, c. the late 1730s-1740, found beneath the clay used to reseal the building’s cellar following the fire. The remaining seven pairs of scissors and snips were found above the burned layer, indicating that they were either undamaged by the fire, or were acquired following the rebuilding of the house between 1741 and 1755.

33 A pair of broad-bladed tailoring shears speak to the wide range of dressmaking tasks taking place in the house. The blades are a similar width almost all the way along before narrowing to a point, a curve similar to the shape and proportions of tailors’ scissors portrayed in 15th and 16th century artwork.67 The other pairs associated with Bourg’s household are small, sharp-pointed, fine snips with a strong taper and general proportions that suggest that they were ciseaux à broder, used for fancy work.68 Features of these scissors correspond with various types that Noël Hume dates to the middle of the 17th century, earlier than the styles uncovered at Belleisle and Louisbourg but similar to the large snips found at Louisbourg and Belleisle.69 Despite the family’s association with a supposed elite social group, no ornamented snips were found at the Melanson site. The scissors all had plain hafts, and the surviving loops were equally undecorated. These may have been older pairs rescued from the house before or during the fire, perhaps along with a sewing basket, as no thimbles, pins, or needles were found in the charred layer – though a handful were found in various layers of the midden.70

34 Labour was distinctly gendered in Acadia, with men doing the bulk of the travel, field labour, and engagement in public life while leaving the women to run the dairies, gardens, and domestic sphere.71 A married couple created the minimum economic and labour unit required to run a farm settlement, and Charles’s sister Madeleine, the Widow Belliveau, would have been relying on her brother and sister-in-law for assistance on the homestead.72 In 1710, Anne Bourg had an eight-year-old son and a toddler girl underfoot and the widow Belliveau had four children ranging from four to thirteen years old. The relatively close proximity of the houses would have given the sisters-in-law the ability to task-share and divide the labour of running the homes and raising the children.

35 It is easy to picture Belliveau and her young daughter Marie walking across the grass to Anne Bourg’s house, their sewing tools and mending tucked into the baskets they carried beneath their arms. The women would have sat and sewed on the stoop in the summer sun, taking advantage of the light to complete their fine needlework and mending before having to move inside to sit by the fire. Trestle tables would have made space to lay out lengths of wool for cutting, the heavy shears slicing through homespun and imported strouds alike. The design of the shears made for easy balance and the ability to estimate seam allowances by eye, making sewing up of the pieces simple enough for even those daughters still learning the task.

36 By 1740, during the period of the house’s final rebuild, Melanson and Bourg would have needed space only for themselves and sons Pierre, Joseph, and Claude. The household, depending on the exact date of the fire, may still have included son Jean, who married in 1742.73 With fewer people for whom to sew, we might expect Bourg’s need for tools to drop and yet we find her in possession of a very well-appointed array of scissors, shears, and snips in the final 15 years of her residence in Acadia. The ratio of three pairs of snips to two pairs of scissors and one pair of specialty shears is similar to others seen across the Acadian settlements, suggesting general interest in fine work, embellishments, and embroidery. Overall, the predominance of small scissors may indicate smaller-scale production aimed at dressing an individual family rather than a production or putting-out system. Bourg had no daughters at home during these later years to teach or do her finishing work, but she did have her sister-in-law. The Widow Belliveau’s son Charles and his wife Marguerite Granger may have moved in with her after they married in 1717, or possibly taken up residence in a larger house located almost directly north of them at the settlement, as seen on Delabat’s 1708 map of the site.74

37 Three pairs of basic scissors served for lighter fabrics or smaller cuts, clipping curves for well-fit seams with much greater control than the heavy shears. There were enough there for each woman to have had her own, nestled in her sewing kits beside pairs of snips to cut the finely spun sewing threads. The fine-tipped snips would also have been useful to unpick tangles, and trim the threads and cords used to sew on the kinds of round glass beads found in a few places on the site. Buttons discovered in the yard might have been lost from clothing but could also be lost from mender’s fingers, or a sewing basket accidentally spilled into the longer grass.

38 The fancy scissors and snips found at Beaubassin and to a lesser degree at Belleisle are nowhere to be found at Melanson. The plain nature of the scissors suggests a more utilitarian intent rather than display, an intriguing distinction. It may have been a question of replacement cost, tied to the need to put assets into rebuilding the home that had been destroyed by fire. Association with aristocracy did not in and of itself guarantee wealth – Anne Melanson’s daughter Agathe, for instance, sold the seigneurial rights she had inherited to the British in 1734 for the grand sum of £2,000.75 The Melansons, on the other hand, were not poor and other status-carrying items including sleeve buttons and a spur buckle have been found around the family’s homesteads at the settlements, suggesting that cost was not necessarily the issue.76

Conclusions

39 What we see when comparing data from excavated properties in Acadia with existing occupation records and inventories is a fairly consistent ratio of one pair of utility scissors per adult woman per settlement, and at least one pair of snips for every female adolescent and adult. Where there are multiple adult women and a traumatic departure, as with Belleisle or Melanson prior to the fire, archaeologists have found at least one set of plain-work and fine-work scissors for each adult woman. Locations that may have allowed slightly more time for packing prior to departure, such as Louisbourg, have revealed primarily broken embroidery scissors, with little evidence of more utilitarian scissor sets left behind. Marie Savoie and Marguerite Blanchard at Belleisle had a minimum of five sets of scissors between them, three of a type dedicated to fine work and embroidery, including decorative snips of good quality. This suggests that embroidery was a passion and a pleasure for at least one of the residents. The fire at Melanson left one pair of large scissors and three or four fine-work pairs in the rubble, suggesting one main garment worker and a handful of others associated with finishing and embellishment. At Louisbourg we are left with one pair of larger working scissors for the adult woman in the house, and five pairs of snips, enough to make sets for the adult Marguerite Richard – the Widow Dugas – and her four young daughters, who were between the ages of eight and fourteen when they left the property in 1745.77

40 The distinctions between the styles of scissors found at the different sites may reflect a similar distinction in the presentation of women’s identity within the different Acadian communities. The main status-bearing objects found at Melanson were associated with male clothing, other than a series of fine straight pins and a heart-shaped badge from the midden at Anne Melanson’s homestead.78 With their proximity to Annapolis Royal, the Melansons were never far from the eyes of power; yet, at the same time, the women living at the Melanson settlement had little to gain by presenting themselves as elite. The Melanson family and their allies were described by the English as being “aw’d by the Garrison [and] are the most, if not the only tractable Inhabitants in the province.”79 This close relationship, their relative wealth and access to imports, and the Melanson site’s close proximity to the official presence at the fort shaped their material culture. Anne Melanson, first married to Jacques de Sainte Étienne de la Tour, a member of the local nobility, had returned to her birth family and taken a local man as her second husband.80 She brought her connections, status, and the rights to administer the La Tour estate with her as resources for Alexandre Robichaud at their marriage, at least until her children came of age.81 She had no need to display her status to those at Fort Anne, and indeed may have been better off keeping to the simpler lifestyle permitted to Madame Robichaud.

41 Beaubassin, at the other end of Acadia, was on a vitally important portage route and, as a trade centre, hosted varied groups of travellers. Traders from New France came down the Northumberland Strait and through Baie Verte, while New England merchants sailed in through the Bay of Fundy and Mi’kmaw travellers circulated along their millennia-old portages and trails. Geographically more distant from centres of imperial influence than Melanson and Belleisle, Beaubassin was outside of the radius of territorial control of both the French and the English, and, as such, had more social freedom to establish new practices.82 Some women in Beaubassin chose to make their pride in their sewing tools visible in silvered plating, and that performance of a high-status feminine identity would have been readily understood by many who came through the settlement – a dramatic contrast to the descriptions of women with clothing “pitched on with pitchforks & . . . yr stockings down about their heels” made by Robert Hale in 1731.83

42 That contrast presents something of a conundrum for the modern researcher. Many comments on Acadian productivity appear in letters both from French and English officials. Called lazy and indolent, the official ire was primarily directed at Acadian men with claims that they had left the uplands uncleared and unfarmed.84 Governor de Brouillan, replacing Villebon in 1701, wrote on arrival that he had discovered the Acadians of Minas to be living “en vrais républicains, ne reconnaissant ni autorité royale ni justice,” an expression of frustration at a people apparently chafing at his assertion of imperial control.85 Women’s work is mentioned in these reports only in positive praise for their industry, but there may be an issue of perception at play. Where Villebon and Dièreville saw the products of women’s work, they did not look too closely at the details. Acadians were described as being “in no way distinguished by new styles,” a statement which archaeological finds have proven incorrect.86

43 The work required to run an Acadian homestead in the period was significant, and followed a seasonal round.87 While the majority of the evidence and testimonials on the subject stem from studies from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, evidence suggests that the seasonal rhythms of life were similar in the earlier years of the settlements.88 Brook Watson describes Acadian women working collectively in textile manufacture, primarily in the summer months, a pattern corroborated by Perrot in 1686.89 Adrienne Hood’s work on Pennsylvania weavers indicates that carding and weaving were often done outdoors or in outbuildings, thanks to the quantity of dirt coming off of the wool as it was being cleaned as well as the noise levels created by a functioning loom.90 Outbuildings found at Acadian sites – as with one structure currently identified as a barn on the Blanchard property at Belleisle, for instance – were large enough to hold a loom or two, opening up the possibility that we could be looking at weaving studios in among the barns and storage structures as well as in residences.91 Contemporary accounts from writers like Villebon and Dièreville describe Acadian women as making much of their family’s clothing at home – processing and weaving flax and wool – but do not describe whether the women worked together or in solitude, more during one season than another, or even the general rhythms of their day.92 During the seasons when materials were readily available, daylight lingered longer and travel between homesteads and settlements was easiest. Maintenance and production of clothing items, however, including all stages of pattern making, cutting, and sewing, would by necessity happen throughout the year.

44 The material evidence suggests that some of that sewing time at Beaubassin and Belleisle took the form of genteel pursuits, women there splitting their time between subsistence sewing and weaving and embroidery and other decorative fine work. They sewed in public spaces with the potential for social engagement, using decorative tools as a means of displaying status and further pride in their work. This correlates with ways in which fine work was associated with higher status for European women. The presence of fancy tools at Belleisle, Louisbourg, and Beaubassin suggests the growth of a new, local elite engaging in the cross-class disruption of what was “luxury,” which triggered anxious commentary from officials concerned about a subtle usurpation of colonial authority by settlers engaging in activities inappropriate for their station.93

45 The fancy embroidery scissors and the silks and ribbons found in Jeanne Thibodeau’s sewing equipment, and in Marie Savoie and Marguerite Blanchard’s home at Belleisle, indicate ways in which women were able to define themselves through the use of high-status tools.94 Fancy work and the attendant idealized domestic femininity stands in contrast to the descriptions of simple Acadian farmers given by English travellers, who described only “clothes pitched on with pitchforks,” and the practical reuse of English “scarlet duffil” recycled into homespun skirts.95 Acadian women did whitework and embroidered with colourful silks, and both extant lace bobbins and contemporary testimony confirm that lace was in demand.96 The geometric stylings on the hafts of the decorated embroidery scissors at Belleisle and Louisbourg mirror the simple geometry of weaving and stitching, crosses, curves, and squares, thus turning both handles and fabric into works of art. Jules Prown describes artifacts as “artistic signs articulating a climate of belief” – the forms of objects reflecting and personifying cultural subtext – here, the specialized tools for fancy work are marked as fancy work themselves.97 The social importance of decorative work is doubly underlined in the scissor design, a privileging of artistic expression.

46 The question of the unusual quantities of scissors and snips at Acadian sites can be answered in correlation with household population information. The snips found at Acadian sites correspond with the number of young women living in their mother’s households. Girls would learn sewing at their mother’s knees, beginning with simpler tasks such as hemming and sewing long seams. A young woman’s textile skills were of paramount importance, the ability to “weave a web of cloth” considered as fundamental to the proper running of a household as a young man’s abilities in carpentry and farming.98 Sitting at the fire and on the front stoops of their houses with their mothers, aunts, and sisters, the girls of Acadia learned the skills they would need for their own households and gave their communal labour to textile production and fancy work.

47 The scissors and the needle cases they used were items meant to be seen both in context of sewing work and social life. Finely pointed and decorated on the handles, silver-plated or steel, scissors played an important role in Acadian women’s structuring and consideration of their roles as creators. Distinct – and yet not entirely divided – from the scissors used by the women round her, Jeanne Thibodeau’s covered scissors reveal something about her preferred leisure activity alongside her beliefs about her place in Louisbourg society. The plain scissors found at the Melanson settlement tell us, however, that status signalling is not the only force at play. Analysis of socioeconomic differences between the “elite” Acadian families and the poorer settlements also found limited differences in the kinds of goods owned regardless of family income.99 This difference is heightened when the Melanson settlement is compared to Belleisle, where the rural farms were supposedly less sophisticated, but the sewing equipment was fancier.

48 This dichotomy disturbed cultural expectations associated with European gentility, which paired high status and elite femininity with leisure sewing. The disparities between supposed status, social presentation, and coded activity of the women in the different Acadian settlements would have been a source of tension. It was the kind of mismatch that may have increased the general perception of Acadians as moving away from the manners and mannerisms which were so much a part of continental French social understanding. It is that growing distance from imperial expectation and changes in social cues that suggests a forming perception change, and more justification for those on the outside to begin to see Acadian culture as something distinct and other.